Criminal Legal Aid Advisory Board (CLAAB) annual report 2024

Published 14 November 2024

Applies to England and Wales

Chair’s introduction

To The Right Honourable Shabana Mahmood MP, Lord Chancellor and Secretary of State for Justice.

I am pleased to introduce the first Annual Report of the Criminal Legal Aid Advisory Board (CLAAB). Although CLAAB was set up in October 2022, I was appointed as Chair in July 2023, and therefore this report covers more than a calendar year.

I would like to take the opportunity to thank all who have participated in CLAAB for their contributions to the work we have done over the year, and the cooperation which they have shown. Whilst the perspectives and interests of members and organisations involved in tackling the complexities of criminal legal aid differ, there has been a recognition of the importance of the work of CLAAB, and a common commitment to improvement.

Our work has been underpinned by the solid foundation of the Criminal Legal Aid Independent Review (CLAIR). The principles and aims established in the report have not been affected by the passage of time and intervening events, but inevitably the data gathered between 2018 and 2021 has become less current and relevant. In this report we identify what progress has been made since CLAIR and based upon our work to date, make recommendations towards achieving a fair and sustainable criminal legal aid system.

Her Honour Deborah Taylor

Chair

Part 1: introduction

1. This is the first annual report of the Criminal Legal Aid Advisory Board (CLAAB). CLAAB was set up as a result of the report of the Independent Review of Criminal Legal Aid (CLAIR), published on 15 December 2021. CLAAB met first in October 2022 and an independent Chair was appointed in July 2023.

2. CLAIR recommended an independent Advisory Board reporting at regular intervals to the Lord Chancellor, able to take a wider view, consult other stakeholders in the Criminal Justice System (CJS), support policy development, and think ahead about improvements to the system and the additional data needed. In addition, the Advisory Board would promote more joined-up thinking across the CJS on matters affecting criminal legal aid and foster a more coherent approach to criminal legal aid. Whilst the Board was not to be a pay review body, it would be a forum in which the overall functioning of the system would be kept under review, reinforced in due course by additional data on how the system is meeting the public need. In that context, CLAIR anticipated issues of provider remuneration may well arise.

Part 2: the structure and working of CLAAB

3. The membership of CLAAB includes representatives from the Law Society for England and Wales (TLSEW), the Bar Council for England and Wales (BC), the Criminal Bar Association for England and Wales (CBA), Criminal Law Solicitors Association (CLSA), London Criminal Courts Solicitors Association (LCCSA), Chartered Institute of Legal Executives (CILEX), the Legal Aid Agency (LAA), Young Barrister Committee (YBC), Young Legal Aid Lawyers (YLAL), the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) and the Ministry of Justice (MoJ).

4. At the outset CLAAB sub-groups were set up, bringing additional expertise from participating stakeholders to bear on particular schemes: the Police Station, Advocates’ Graduated Fee Scheme (AGFS) and Litigators’ Graduated Fee Scheme (LGFS). Their work has fed into papers and discussions at CLAAB meetings. Members of CLAAB or the organisations represented are also involved in other working groups tasked with improving the CJS as a whole, such as the Crown Court Improvement Group (CCIG), and therefore bring that additional experience and knowledge of developments and initiatives elsewhere in the CJS.

5. CLAAB is therefore an independent advisory board with an experienced membership representing different, and sometimes competing, interests. CLAAB meets quarterly, with sub-groups meeting in the interim period. Given the extent of problems facing criminal legal aid, the agenda at the meetings is extensive. It is important that there is open and full discussion of the issues, but that this is not an end in itself. We are committed to reaching agreement and making recommendations for the reform of legal aid in the immediate and longer term.

6. We adopt the approach taken by CLAIR[footnote 1] that policy making should be for the Lord Chancellor and MoJ. It follows that the constitutional role played by the MoJ in formulating and implementing government policy, and in preparing consultations and papers concerning aspects of legal aid in accordance with those policies sets it apart from other CLAAB participants. The same applies to an extent to the LAA. This is important for two reasons. Firstly, the MoJ approach in CLAAB to criminal legal aid has been for the most part set out in consultation documents, and papers brought to CLAAB for discussion and consideration. To that extent the proposed direction of travel has been set before CLAAB involvement, although subject to discussion and advice. Secondly, the pace of any criminal legal aid reform or pilot advised or recommended by CLAAB is determined by the pace of the MoJ, which is in turn governed by political interest and the availability of funding. As we turn into our second year, we hope that in view of the extent of the problems we identify, both are in greater supply.

7. This Report sets out the increasing challenges facing all areas of criminal legal aid. Our overarching recommendation is that substantial immediate additional funding is required in all areas we have highlighted, to have any chance of meeting CLAIR objectives. Delay is likely to increase and exacerbate the problems.

Part 3: implementation of CLAIR

8. It is now over two and a half years since the publication of the CLAIR report in December 2021, a period which may be characterised as one of delay, dispute and disruption: delay in implementing the recommendations; dispute about the funding and extent of implementation; consequent disruption by industrial action by the Criminal Bar, and a Judicial Review brought by TLSEW.

9. There was delay between November 2021 and October 2022 in setting up CLAAB, and further delay from October 2022 to July 2023 in appointing an independent Chair. Between November 2021 and the recent General Election there were also three changes in Lord Chancellor. We set out these points not to make political comment but as necessary background to understanding the progress made by CLAAB over the last year.

10. In a similar vein, it is also important to highlight the different and differential approaches which have been taken to the implementation of the central CLAIR recommendations on fees in respect of the work of the Criminal Bar on the one hand, and solicitors (including for these purposes, Legal Executives) on the other.

The Criminal Bar

11. Following CLAIR, in March 2022 the MoJ announced a consultation on a 15% increase in criminal barristers’ fees for new cases only, not covering the then backlog of 60,000 cases. As a result, the CBA began industrial action in April 2022, escalating to an indefinite strike in September 2022. In October 2022, the Criminal Bar agreed a ‘deal’ which comprised a 15% increase for most fees in the Crown Court, £3 million of funding for Wasted and Special Preparation, and £4 million for Section 28 pre-recording of evidence.[footnote 2] Part of the deal was that CLAAB be set up with an independent Chair.

12. The 15% increase in fees has been implemented. A further increase to fees in areas set out below equates to roughly a further 2%.

13. For Wasted and Special Preparation, on the basis of projected case volumes and the total allocated amount, an additional bolt on fee of £62 plus VAT per case was calculated by the MoJ and provided for cases with a Legal Aid Order granted after 17 April 2023. The MoJ estimated that the spend would be £3.2 million by March 2025.

14. According to MoJ figures provided on 6 July 2024 the actual amount spent to the end of May 2024 was £594,826. Projections on the basis of multiplying the highest monthly figure of £140,000 (May 2024) by the 10 months to March 2025 would give a sum over the remaining period to March 2025 of approximately £1.4 million, giving a total spend to March 2025 of £2 million, as against the deal figure.[footnote 3] The CBA and Bar Council suggest that the fee for wasted special preparation in every case should therefore be raised from £62 plus VAT to £100 plus VAT with immediate effect to meet the figure agreed in the deal.

15. For s.28 fees a similar calculation was made by MoJ based on the projected case volumes and allocated amount, which resulted initially in a flat fee of £670 plus VAT being paid for each section 28 hearing. In October 2023 the s.28 fee was increased to £1,000[footnote 4] excluding VAT.

16. As at the end of May 2024, the amount spent on s.28 was £239,836. Projections on the largest monthly figure of around £71,000 (for May 2024) multiplied by the 10 months remaining until March 2025, provides a total spend figure of £1 million[footnote 5] against the deal figure of £4 million. The CBA have requested that the underspend be used to pay for increased Rape and Serious Sexual Offences (RASSO) fees in order to recruit and retain more RASSO advocates to meet the increasing insufficiency of advocates in the Courts.

Solicitors and members of CILEX

17. In contrast to the Criminal Bar, the 15% fee increase for criminal solicitors recommended by CLAIR was not implemented in full. Following the interim response to CLAIR a decision was made to increase solicitors’ fees by 9%. The background to that decision is set out in detail in the judgment of the Divisional Court in R (on the application of TLSEW) v The Lord Chancellor [2024] EWHC 155 (Admin), following TLSEW’s application for judicial review.

18. In addition to the 9% uplift in fees, £21.1 million had been identified by the MoJ for longer term reform. In November 2022 it was decided that this sum would be allocated with £16 million to reforms to the Police Station Scheme and £5.1 million to reform of fees in the Youth Court. Once achieved in steady state this would broadly represent a further 2% overall increase to solicitors’ fees.

19. Between January and 28 March 2024, the MoJ carried out a Crime Lower consultation, outlining options for use of £16 million to affect the harmonisation and reform of the Police Station fee scheme and £5.1 million for reform to the Youth Court. The General Election intervened, and to date any proposals following the consultation are unknown. Implementation of the further uplift of 2% to solicitors’ fees has therefore not begun and is behind the original timetable.

20. In 2023, TLSEW was granted permission to bring an application for judicial review of the Lord Chancellor’s decision to implement a lesser fee increase than the 15% recommended by CLAIR. That application was heard on 12–14 December 2023 and the judgment was handed down on 31 January 2024. A declaration was granted that the Lord Chancellor’s failure, during the decision-making process, to ask whether fee increases at lower levels than the 15% recommended in the CLAIR report would, or might, still deliver the aims and objectives of the CLAIR report, was irrational and breached his Wednesbury duty; and that the Lord Chancellor’s failure to undertake any modelling to ascertain whether the aims and objectives of the CLAIR report, in particular ensuring the sustainability of criminal legal aid, would be furthered if fee uplifts lower than the 15% recommended by the CLAIR report were implemented, was irrational and breached his Tameside duty of sufficient enquiry.

21. To date there has been no action taken by the Lord Chancellor in response to the judgment.

22. In short, the historical pattern of industrial action and Judicial Review taken respectively by the professions to achieve increases in funding[footnote 6] has continued through the period following CLAIR, to greater or lesser effect. We cannot pass over the fact that irrespective of the recommendations of CLAIR as to where additional funding should best be directed[footnote 7] and the strength of the case for increased funding, criminal legal aid firms have to date received significantly less by way of percentage increase in funding than the Criminal Bar. We hope that greater co-operation in CLAAB will mark a change of direction away from the recent trend whereby the obtaining and level of increases in funding depend on the disruptive effectiveness of the action taken by the respective professions. Financially realistic, merit-based increases would render such action unnecessary.

23. The effect of delay in implementation of the CLAIR increase in funding, (described in CLAIR as “the minimum necessary as the first step in nursing the system of criminal legal aid back to health”, for which there was “no scope for further delay”) has been further exacerbated by inflation and rises in the cost of living to the extent that both professions contend that significant further funding is now required to achieve the aims of CLAIR. This is a position supported by CLAAB and reflects the position of others who have had recent in-depth access to the data.[footnote 8]

Part 4: overview of CLAIR principles

24. We acknowledge that CLAAB is not a pay review body in the generally accepted sense, and consequently we will not be making recommendations as to the detailed level or amount of fees. Nonetheless, reform or improvement of criminal legal aid fee structures cannot be made in a vacuum, and consideration of the overall funding of the criminal legal aid system is fundamental to our role in making recommendations.

25. Our remit requires review of how criminal legal aid reform can best achieve the key principles identified by CLAIR: measures of resilience/sustainability, transparency, efficiency and diversity in the provision of legal aid to support the Criminal Justice System. At each of our meetings over the last year the Board has benchmarked progress against key CLAIR recommendations and principles, which we now set out.

Sustainability/resilience

26. The broad definition of sustainability and resilience adopted by CLAIR[footnote 9] encompasses a system of public funding, which is able over the years to attract and retain providers of sufficient number, quality and experience to provide effective legal advice, assistance and representation to all those eligible and in need of those services. In particular it envisages a system that is financially viable, has a career path that bears comparison, promotes diversity, and encourages investment, particularly in new technology and ways of working.

27. The increases made following CLAIR have failed to have a positive lasting impact on the key components of sustainability. Both the Criminal Bar and criminal legal aid firms continue to suffer difficulties in attraction and retention. Numbers of practitioners are falling, and there is an overall lack of a clear and viable career path for many. Without intervention this decline will diminish the future pool of high-quality candidates for the judiciary with criminal law experience. In many respects the difficulties identified by CLAIR have increased, primarily due to low fees, the financial climate of inflation, rises in the cost of living and utilities, and the increase in backlog in the Courts.

The Criminal Bar

28. Between 2018/19 and 2023/24 of those declaring their work as crime-only, the number of self-employed barristers fell by 184 from 2568 to 2384, and of employed barristers by 58 from 902 to 844.[footnote 10] These statistics in themselves give an uninformative basis for measuring the widely perceived loss of capacity at the Criminal Bar, experienced every day in courts throughout the country.

Bar data

29. The Bar Council has been active in identifying measures of sustainability and data which should be collected and monitored. In July 2022 the Bar Council sent the MoJ a paper entitled “Measuring Sustainability and Effectiveness at the Criminal Bar”. The paper was sent again to the MoJ in April and May 2024, requesting to work with the MoJ statisticians to develop data measures for use by CLAAB in regularly monitoring the sustainability of the profession, using data available through the existing data-sharing agreement between the Bar Council, MoJ, LAA and CPS, or from Bar Council monitoring data.[footnote 11] The data requested is set out in ANNEX A.

30. We recommend the setting up of regular gathering and monitoring of this data as essential to provide a more granular dataset to assess the areas of the work at the Criminal Bar requiring most attention.

31. The reduction in counsel is affecting the proper functioning of the Criminal Justice System at a time when Crown Courts are sitting at full capacity in order to reduce the backlog. The Bar statistics above, and other figures (such as those who declare 80% or more of their income from criminal work), suggest an overall decline in barristers practising in crime of 7% over five years.

32. There is some suggestion in the detailed figures that the decline is slowing as the 15% increase in fees takes effect, but the numbers of available counsel are not adequate to meet present or anticipated demand. In 2023 over 1400 Crown Court trials were ineffective because no barrister was available. The provision of increased sitting days after a period of reduced sitting has exposed the lack of sufficient criminal barristers to service courts running at full capacity.[footnote 12] Any increase in adjournments affects defendants, witnesses and victims and the efficiency of the Courts, increases costs and undermines public confidence.

Particular problems – RASSO

33. Particular problems have arisen in relation to counsel conducting RASSO cases.[footnote 13] On 4 February 2024 the CBA published a survey of its members. At the time only 668 practitioners appeared on the CPS panel for specialist RASSO advocates at grade 3 and 4, with many having removed themselves from the prosecution list and junior barristers deciding not to train to join the prosecution list. There had not been a CPS re-qualification exercise for existing RASSO certified prosecutors since the Covid-19 pandemic.

34. Approximately 780 criminal barristers completed the RASSO survey with 49% stating that they conducted both prosecution and defence RASSO work. Of 346 RASSO Prosecutors, 246 confirmed they would conduct RASSO cases in the future, and 30% of Defence RASSO Counsel said they no longer want to conduct these cases. Among advocates who conduct Section 28 cross-examination of those surveyed, 31% of defence advocates and 41% of prosecution advocates did not want to carry on, with over 50% saying this was because of lack of remuneration and adverse financial impact on their court diaries, 60% citing poor fees and 50% pointing to the adverse effects on their well-being as the cause for refusing RASSO work.

35. Membership of the RASSO panels have always been fluid. Since the publication of the CBA survey, there has been a 16.6% net increase in RASSO Panel membership, with 135 new joiners and 22 leavers. As of 14 August 2024 the CPS record 791 members of the RASSO Panel at level 3 and 4. The CPS hopes that changes being made in August and September 2024 to the eligibility criteria for Level 2 and application process for Levels 3 and 4 will increase the numbers further and strengthen the career pathway for advocates wishing to undertake RASSO work. From 1 September 2024, the CPS will permit Level 2 advocates to apply to join the RASSO Panel to undertake level-appropriate RASSO casework. The CPS aims not only to increase numbers but to also strengthen the career pathway for advocates wishing to progress into RASSO work.

36. Whilst the increase in RASSO list Prosecution counsel is encouraging, it is far from clear that this development will mark an improvement in the situation in the Courts overall. Advocates can only appear on one side in any case, and 49% of those responding to the CBA survey reported both prosecuting and defending cases. Unless the additional 16.6% on the CPS panels are new to RASSO work, it may simply be that the increase in those on the CPS Lists will mean that fewer Counsel are available to defend cases. An increase in the overall number of Counsel undertaking RASSO work is needed.

37. 1 in 7 cases in the Crown Court are RASSO cases. The Lord Chancellor has recently expressed an ambition for fast-track RASSO courts to ensure that cases come on for trial sooner than is currently the case. It is therefore essential to recognise that there are inadequate numbers willing to carry out RASSO prosecution and defence, and that action is necessary to address this problem.

38. Irrespective of additional payments for s.28 hearings, the fees for RASSO work compare unfavourably with other categories of work, which are now in greater supply due to the backlog. Those formerly doing RASSO work are therefore switching to less sensitive, but better remunerated work, such as fraud.

39. As discussed further below, constructive work is being done by the MoJ in consultation with the AGFS working group on the categorisation of different types of criminal defence work to provide a more rational and sustainable basis for reform of the AGFS scheme. RASSO offences fall within that workstream but it is important that there is no delay in addressing fundamental problems associated with this area of work whilst an overall scheme is worked up. A failure to do so may lead to an irreversible acceleration in the exit of experienced counsel dealing with this specialised and gruelling work.

40. We have set out at paragraphs 14 and 16 above the CBA proposal that the saving against projected cost of s.28 hearings be used to increase RASSO fees as an interim measure.

Matched funding for criminal pupillages

41. The Bar Council has put forward a proposal for matched funding for pupillages in criminal sets to ensure a healthy and sustainable Bar. Whilst not strictly within the Legal Aid remit, we recognise and support the need for funding in this area to support practitioners in legally aided work.

Solicitors

42. We discuss the issue of sustainability in more detail below in relation to the individual schemes governing the remuneration of solicitors’ work.

Decision on action following the Judicial Review

43. As a starting point, we recommend as a matter of urgency a decision be taken by the Lord Chancellor following the outcome of the Judicial Review, which takes account not only of the terms of the Declaration, but the broader current picture of the continuing and increasing adverse impact on the sustainability of the work of criminal legal aid solicitors of the reduced 9% percentage uplift, manifested in the body of evidence provided to and considered by the Court and made available by TLSEW and CLSA.[footnote 14] The lack of a decision on this fundamental issue impacts on the morale and trust of criminal legal aid solicitors,[footnote 15] and is a significant impediment to progress by CLAAB. We advise that retrospective re-running of modelling on the efficacy of lower percentages than 15% when time and inflation have eaten away the value of the full CLAIR uplift is now inappropriate and insufficient, and a realistic prospective approach is needed.

Data collection and monitoring

44. TLSEW has also provided MoJ with proposals for measures of sustainability and data which should be collected. These are set out in ANNEX B. This additional data is required in order to be able to formulate any measures to address levels and quality of provision in all regions. To some extent this data can be obtained from the LAA Legal Aid Bulletin statistics,[footnote 16] but as with the Bar data, we strongly recommend analysis and regular monitoring.

Particular problems – attracting new practitioners

45. A sustainable system is one which can attract and retain new practitioners. Information provided by the Young Legal Aid Lawyers highlights barriers to entry into criminal legal aid work. As CLAIR identified, young lawyers are routinely actively deterred from criminal law by academics and by experienced practitioners providing work experience and shadowing opportunities. This advice is well meant, and prompted by concern that the recipients will not make a living, due to widespread underfunding. YLAL attempts to counter this advice to encourage uptake, but without increased funding, it is unlikely that the initial enthusiasm and appetite of young lawyers for this socially important work will survive the reality of hardship.

46. YLAL reports that due to the chronic underfunding of criminal legal aid, firms are financially unable to take on trainees. A large proportion of criminal law firms will only offer training contracts to existing employees who have already worked for a significant period as a paralegal. There is no guarantee that an offer of a training contract will be made and many young people find themselves trapped in roles which offer no realistic career progression or require them to work for years at low pay before they can actually use the knowledge obtained from undertaking the Legal Practice Course (LPC) or the Solicitors Qualifying Examination (SQE).

Grants

47. In November 2022 £2.5 million of the £21.1 million set aside for longer term reforms which was originally allocated to provide training grants to support trainees in criminal legal aid firms, was reallocated to fund Police Station and Youth Court work.

48. We strongly support the CLAIR recommendation for funding of more training grants to support trainees in criminal legal aid firms, which should be in addition to the other funding increases. Without intervention there is no incentive for new practitioners to take up criminal work, and the lack of a pipeline of solicitors undertaking this work would have devastating effects on the fairness and efficient running of the Criminal Justice System.

Diversity

Solicitors

49. CLAIR identified diversity in social background, gender, ethnicity and age as of particular importance for the provision of criminal legal aid, in order to reflect modern society. The hope was expressed in the CLAIR report[footnote 17] that the general increase in fees recommended would make it easier for criminal legal aid firms to invest in and offer a career path to enable young entrants to the profession from diverse backgrounds to flourish.

50. That has not happened, and criminal legal aid solicitors report a general reluctance, irrespective of background, among the young to engage in this work when the rewards are so much greater, and the conditions more conducive to a balanced life in other areas of law. Those firms who do take on trainees find them leaving after training for the combination of higher salaries and greater benefits offered by the CPS, local authorities or to practice other areas of work. The time and money invested in the training is therefore wasted.

51. Criminal legal aid firms are unable to compete financially. We will therefore be considering a scheme which encourages trainees to stay and discourages CPS and local authority recruitment from the trained pool which leaves criminal legal aid firms out of pocket as well as lacking junior solicitors. Such a scheme must be designed so as not to contravene employment law. It may, for example, require a new employer (such as CPS and local authority) to reimburse the cost of the training contract for any trainee joining within a set number of years of completion of training.

Legal Executives

52. CLAIR highlighted the more diverse backgrounds of many CILEX members as a way of increasing diversity, and worthy of note in the examination of the structures preventing the development of sustainable careers for ethnic minority criminal lawyers. CLAAB has not yet focused on this area of work, and this is for consideration both in connection with recommendations for reform of any schemes, as well as a free-standing issue.

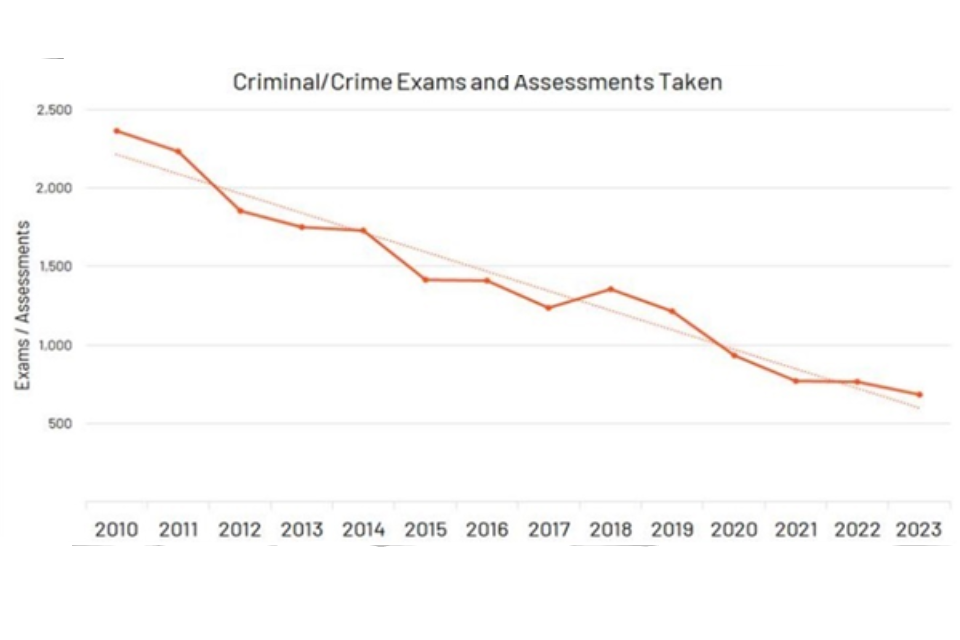

53. We note evidence shown in the CILEX table below of a steady decline in the number of members wishing to practice criminal law. Fewer individuals are taking the necessary assessments to qualify, giving rise to concern for the numbers willing to practice in the future.

Efficiency

54. As CLAIR emphasised, no part of the Criminal Justice System stands alone. Inefficiency, or funding decisions taken in one component part invariably affect others. This is nowhere more evident than in relation to legal aid.

The LAA

55. CLAIR considered the remit of the LAA as the MoJ agency responsible for the delivery of legal aid and recommended that the MoJ should reconsider and re-frame the objectives of the LAA to reposition the LAA’s primary objectives to support the resilience of the criminal legal aid system and reduce unnecessary bureaucracy, while maintaining proportionate control over costs. Recommendations included that the MoJ, LAA and relevant stakeholders should work through the LAA’s contractual and related procedures with a view to simplifying and reducing administrative burdens where proportionate to do so. The LAA should review its staff training programmes to implement a more flexible approach to claims for reimbursement, and should consider the various specific issues outlined in CLAIR concerning the Defence Solicitor Call Centre (DSCC), earlier payment of advocates’ fees and reimbursement of experts fees in the Magistrates’ Court via interim payments, with a view to resolving with the MoJ what action may be appropriate.

56. The LAA uses over 100 digital systems to process criminal applications and pay bills and is hampered in responding to change by the number, age and lack of capability of those systems. Much input is manual and depends on the quality of the form filling and handwritten content of submissions from providers. With a long history of underinvestment in maintenance and modernisation, the LAA is now understandably cautious in relation to change, as implementation of new systems takes substantial time and resources, and adds to the instability and risk of failure of existing technology. Important initiatives such as interim payment of fees therefore face practical difficulties which are unacceptable in modern systems. No effective modern system would be faced with a “one in one out” choice when dealing with new capacity or change.

57. The LAA’s lack of flexibility in existing systems is viewed by all members of CLAAB, including the LAA, as an impediment to change. We recommend a review of LAA digital systems and capacity to assess how and where change and rationalisation would be most effective. We are aware of the enormity of the task, and of the potential for cost escalation and disruption caused by large scale computer change,[footnote 18] but if the systems are not improved there is not only a limited capacity for increased efficiency, but also an increasing risk of widespread disruption and hardship caused by delay in payment, should the aged systems fail.

58. In response to CLAIR, the LAA reports that it has prioritised reviewing legal aid contracts to reduce unnecessary administration and increase flexibility for legal aid providers. With that aim, the LAA has engaged constructively with defence representative bodies and with groups of legal aid providers to discuss potential options for change including specific priorities that they may have, in the design work on the next criminal legal aid contract for introduction in October 2025.

59. On 17th June 2024 the LAA launched a 6-week engagement exercise with a small group of Consultative Bodies (TLSEW, Bar Council, the Legal Aid Practitioners Association, and the Advice Services Alliance) as a proxy for potential contracting parties. The LAA aim to use the 2025 Crime Contract to support market sustainability through reducing administration and barriers to entry for potential contracting organisations.

60. In this context the CLSA highlights the need to reduce the administrative and data collection burdens on legal aid firms as a result of current LAA requirements considered necessary to maintain duty solicitor status and to be a supervisor, the number of audits and KPIs imposed, and the complexity of the process of CRM7 billing. The LAA continues to review its training programmes to provide a more proportionate approach to the reimbursement of claims. To some extent the rigidity of the current allowable KPI margins for error militate against the LAAs ability to take a more proportionate discretionary approach to claims where appropriate to support the resilience of the criminal legal aid practitioners.

61. CLAAB will invite further input from the MoJ, LAA, those involved in the June 2024 consultation exercise and other affected members prior to making any recommendations on further reform in this area, including consideration of payment of interim disbursements in Magistrates’ Court cases in line with the system in Crown Court cases. Options and implications (including any necessary regulatory changes and operational challenges) associated with earlier payment of advocacy fees and potential changes to payment mechanisms for expert witnesses.

Transparency and data

62. We have touched on proposals for data gathering and monitoring under Sustainability above.

63. CLAIR identified the problem of the general lack of data on how far the criminal legal aid system is adequately meeting the public need, for example in relation to particular geographical areas, particular users, particular offences or particular areas of work. There was no data to evaluate the cost implications of decisions in one part of the CJS on criminal legal aid. We would add that there was no or insufficient data to evaluate the full implications on the sustainability of criminal legal aid firms or the Criminal Bar of funding decisions which took no account of the adverse consequences of variable factors such as inflation, market conditions or decreased profitability. We have set out above the proposals by the Bar Council and Law Society for a strategy to increase the depth and reliability of data regarding sustainability.

64. The lack of reliable robust data continues to hamper progress on reform. Examples of this are discussed in relation to individual schemes below.

65. One legacy of the history of criminal legal aid set out in detail in Chapter 4 of CLAIR is mistrust which manifests in a reluctance to provide data. On the MoJ side this is apparent, for example in the approach taken to disclosure of CLAIR modelling prior to the Court requiring disclosure in the course of Judicial review proceedings. On the other hand, Criminal Legal Aid providers are reluctant to engage in another data gathering exercise which requires the spending of precious time and resources away from fee earning, when there has been no proven benefit in doing so.

66. It is important that CLAAB moves forward. We recognise the need to support reform and the need for funding by the provision and analysis of sufficient data, and that all parties must be committed to doing so. But the requirement for data must be proportionate and even handed. The data required should only be sufficient, and not an end in itself. Importantly, we advise that there should be no greater requirement imposed on the professions for data to support increases in funding for criminal legal aid than for data used by MoJ to support no increases or cuts. Whilst providers such as criminal legal aid firms can supply some types of data, the MoJ and LAA are in possession of, or have the means of obtaining necessary data and should bear the primary burden of doing so.

67. With the above principles in mind, we report below on CLAAB work on the fee schemes.

Part 5: Police station scheme

68. The CLAAB recommendation to the Lord Chancellor on the proposed reform of the Police Station Scheme was made during the Crime Lower Consultation in January 2024.[footnote 19] No decision has yet been announced following the Consultation. We do not propose to repeat the contents of the recommendation, which is appended at ANNEX C, but make the following additional observations.

69. Legal Aid statistics including a criminal legal aid data paper from May 2024, provided the following solicitor firm and office numbers from the 2017 Standard Crime Contract (April 2017 to September 2022), and the 2022 Standard Crime Contract (October 2022 to April 2024). The number of solicitors’ firms is the number of active contract holders on the LAA systems at the time that the data cut was taken. Solicitor firm numbers included in the LAA Statistics are based on firms billing throughout the year and will include firms without a contract claim for ongoing cases at the time that their contract ended.

| 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | 2021-22 | 2022-23 | 2023-24 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solicitors’ firms | 1,207 | 1,150 | 1,099 | 1,056 | 1,117 | 1,066 |

| % change | - | -5% | -4% | -4% | -6% | -5% |

| Offices | 1,818 | 1,707 | 1,602 | 1,526 | 1,682 | 1,596 |

| % change | - | -6% | -6% | -5% | 10% | -5% |

70. The longer the period before the introduction of a new scheme, the more the sustainability of firms undertaking this work is at risk. The latest data on duty solicitors shows there are currently (as of July 2024) 3,911 duty solicitors compared to 5,240 in October 2017, representing a fall of 25%. There has been a downward trend for provider offices for criminal work with a 3% decrease over the last 5 years and a 1% decrease over the last year. In the last financial year, the number of providers starting criminal work decreased by 7%.[footnote 20]

71. Good experienced advice at the Police station is of fundamental importance to address the increase in volume of cases in the Magistrates Court and the rising backlog in the Crown Court, but is in diminishing supply. The number of duty solicitors in England and Wales performing this vital service continues to decline, primarily due to reduced financial viability at current rates, workload and the aging profile of those prepared to work in this demanding field.

72. At the same time, as foreshadowed by the July 2021 Justice Select Committee report into the Future of Legal Aid,[footnote 21] case volumes have increased, whether as a result of increased numbers of police or for other reasons. Police Station work between January and March 2024 increased by 19% compared with the same period in 2023. This work made up 69% of the Crime Lower workload between January and March 2024 with the majority of the police station advice (90% in January and March 2024) consisting of suspects receiving legal help with a solicitor in attendance at the police station, with the rest mainly consisting of legal advice over the telephone.

73. It is important for sustainability and reform for the future to take note that these figures reflect a reverse in the general downward trend in police station advice workload in the years after 2013-14 to date. The combined effect of the downward trend in duty solicitors and the upward trend in police station work puts even more pressure on overburdened duty solicitors doing this work.[footnote 22]

74. Whilst the Options proposed by the MoJ represent a necessary initial step towards efficiency in the harmonisation of a significant majority of the existing Police station schemes by lifting the lowest fees up towards the level of the highest fees, it is important to bear in mind that all current fees were fixed in 2008, were subject to the general reduction of 8.75% in 2014 and had received no increase prior to the overall increase of 15% in September 2022. A comparison of 2008 rates[footnote 23] with current rates shows that in all areas where there is currently one provider and one duty solicitor[footnote 24], the effect of both Options is to raise the fixed fee, but in all cases to a level below the 2008 rate. The proposed rates take no account of inflation.

75. Police station work has become more complex and demanding since 2008 for a number of reasons : as a result of changes in the types of crime, the increase in those attending police stations with mental health problems, expansion of the use of mobile phones, the internet and social media, the closure and relocation of police stations. Increase in complexity, increases in the (currently unpaid time and costs of) distance to travel, the unpaid hours of work between the fixed fee and escape fee, increases in the cost of living and practice costs make 2008 level fees incapable of fairly reflecting and paying for the work done, and providing a sustainable future for this aspect of criminal solicitors remuneration.

76. We consider that a scheme without any weighting for experience commensurate with the seriousness of the charge does not support the important focus on appropriate resolution in the early stages of any case journey through the Criminal Justice System. It perpetuates the potential for a misaligned incentive that the more experienced solicitor can earn more as a duty solicitor by taking on several minor cases which take little time, than one serious one, deserving of more expertise, which might or might not trigger the escape mechanism.

77. In March 2024, we recommended that the lack of data cited as a reason for not modelling a scheme be addressed by the obtaining and provision of that data by the MoJ, LAA and where appropriate, providers. Although the MoJ has since published updated LAA data in June 2024, that data cannot be used for scheme modelling. We advise that the MoJ itself should be astute to identify necessary data and, having in-house capability, willing to carry out such modelling to assist CLAAB.[footnote 25] We also advise that whilst not a form of data which is capable of being used for modelling purposes, the volume of “cogent evidence” which was produced and considered by the Divisional Court in [2024] EWHC 155 (Admin) should not be dismissed as merely circumstantial, but as supporting the need to press on at pace with a revised approach to the funding of this work.

78. We therefore reinforce our January 2024 Recommendation made in relation to the Police Station scheme that the second stage of reform be advanced at pace.

Part 6: Youth Court Scheme

79. As with the Police Court Scheme, the CLAAB Recommendation to the Lord Chancellor on the proposed reform of the Youth Court Scheme was made during the Crime Lower consultation in January 2024, and included recommendations for monitoring the workings of the scheme.

80. The new Government has expressed an ambition to halve violence against women and girls and knife crime over time. Knife crime is increasingly prevalent among those appearing in the Youth Courts. Greater investment in this part of the criminal justice system and ensuring that there is adequate pay for the advocates would be likely to pay dividends. A system focussed on minimising reoffending should provide young offenders with experienced advice and representation at a time of greatest influence on their future. The present remuneration pays fees at rates which attract only the most junior barristers. Youth Court work should be given higher status and commensurate fees to reflect the importance of the work.

81. The CBA and Bar Council advocate a separate system of payment, and use of the certificate for Counsel as in the Crown Court rather than through solicitors. We recommend separate payment for the work done by solicitors and the Bar undertaking this important and often complex work. This would support the availability to many young and vulnerable defendants of access to the highest quality advocacy in the Youth Court.

Part 7: Magistrates Court

82. The Magistrates Court Scheme has not been a CLAAB priority over the past year, as it is perceived as having the fewest problems. Nonetheless some important issues have arisen.

Rates and structure – no payments on account and interim payments of disbursements and expenses

83. Fees are paid at the conclusion of the case; there is no ability to claim a payment on account.[footnote 26] Similarly, there is no scope to claim disbursements and expenses on account and so they have to be funded by firms from their own resources until a case finishes and is billed. These can amount to large sums, especially for experts’ reports.

84. The fees are paid on a graduated fixed fee system where time is recorded and there are 3 thresholds: (1) lower standard fee (this covers 80% of cases); (2) higher standard fee (covers trials and more complex matters with multiple hearings); and (3) non-standard fee (paid when a threshold is reached, on an hourly rate basis). The underlying hourly rate is £52.15 for preparation, and £65.42 for advocacy.

85. These fees vary according to whether the case is an either way or summary offence and according to plea, but broadly range from £182.01 lower standard fee to £737.08 Higher Standard fee (payable only after at least £538.02 of work is recorded). After £896 a non- standard fee is payable. (In contrast it should be noted the average payment for a private prosecution in the Magistrates is £4,280,[footnote 27] also paid out of the LAA/MoJ budget).

Means testing

86. Legal aid in the Magistrates Court is means tested using a different scheme to the Crown Court, with fewer people being eligible. The MoJ’s Means Test Review 2022 proposed restructuring and substantially raising the highest income levels at which people are eligible for legal aid, meaning that 3.5 million more people would have incomes that qualified them for such help should they need it. The implementation of these reforms has been delayed, with the earliest date of their introduction suggested being summer 2026, with a phased implementation thereafter.

87. This reform has been anticipated over a period in which prices have risen rapidly but uses 2019/20 ONS data[footnote 28] for benchmarking the new means test. The current system increasingly fails to help those unable to meet legal costs, and inflation adds further uncertainty as to the ability of the proposed reform to do so.[footnote 29]

88. An accelerated inflation-adjusted launch of the reforms in 2025 would dramatically reduce the shortfalls in the incomes of people being denied legal aid based on the means test.

Committal to the Crown Court for sentence

89. There is currently an anomaly in the system, giving rise to misaligned incentives.

90. In ‘either way’ cases, which can be heard in either the Magistrates’ or Crown Court, where the plea is heard in the Magistrates’ Court but the case is so serious that the magistrates do not have sufficient sentencing powers it is then sent to the Crown Court for either sentence or trial, depending on the plea.

91. For cases where there is a guilty plea in the Magistrates Court, for the purposes of legal aid, the means test from the Magistrates Court is applied for the committal for sentence, despite the sentencing proceedings being in the Crown Court. If the defendant has failed the less favourable Magistrates’ Court means test, this refusal will be carried over into the Crown Court, with the result that they will not be entitled to representation at the Crown Court sentencing hearing, even in a serious case that could result in a significant custodial sentence.

92. In contrast, for cases where there is a not guilty plea in the Magistrates Court the case is then sent for trial in the Crown Court, and in this case the Crown Court means test is applied.

93. If a defendant initially pleads not guilty, is committed to the Crown Court , but changes their plea well before the trial, they will still have the benefit of legal advice and representation at the sentencing hearing. However, the later the plea, the less credit and consequent reduction in sentence will be given in accordance with Sentencing Guidelines.

94. The result is that the fundamental aim of achieving appropriate early guilty pleas in the Magistrates Courts is frustrated, and an invidious choice faces a defendant between legal representation or full credit for a guilty plea. In effect this system penalises people for pleading guilty early on in the case, increases the number of unrepresented defendants, and runs counter to the current emphasis on early preparation and disposal.

95. We recognise that implementation would require operational, policy, and legislative changes and consideration of its relative priority. We note that to date, the policy approach has been to retain the Magistrates’ Court means test for Committal for Sentence cases. Any change highlights the problems we have already identified with outdated LAA digital capacity. We recognise that the digital systems the LAA uses to process applications, payments and potential contributions have distinct sets of workflows, rules and operational processes. In order to implement the Crown Court Means Test for Committals for Sentence the LAA’s digital systems would first need to be updated, which risks disrupting business as usual.

96. The current hardship review process acts to some extent as a safeguard for individuals in relation to Committal for Sentence cases, permitting an individual who fails the Magistrates Court means test to submit a CRM16 application to the LAA on the grounds they are unable to afford private representation. A representation order for non-contributory legal aid may then be granted to the individual, but the numbers granted are low.

97. Whilst accepting the difficulties with implementation, we consider digital capability cannot be sufficient reason not to introduce change which supports a fair and efficient Criminal Justice System. We therefore recommend that committals for sentence should be treated for the purposes of legal aid as Crown Court proceedings and the Crown Court means test should apply. Implementation of this recommendation would increase the likelihood of guilty pleas and assist in the reduction of the backlog.

Part 8: Prison Law

98. CLAIR recommended the introduction of a standard fee model for prison law advice and assistance and CCRC fees. Cases would be paid either a lower or higher standard fee – and some would escape to non-standard fees (paid at hourly rates). In preparation for the Crime Lower Consultation, the MoJ modelled potential standard fee schemes for both prison law and CCRC fees but it was not proposed that revised fee schemes be introduced. The rationale provided was that it would be best to focus investment on reforming and improving engagement in the initial stages of criminal cases, helping divert people out of the criminal justice system, support early case resolution and reduce backlogs.

99. Additionally, in order to stay within the then current budget, any changes to the fee schemes would have had to be made on a cost-neutral basis. The proposal in the consultation was therefore for no change to Prison Law fees.

100. Prison Law was excluded from the 15% uplift. This is an area where the work has become increasingly complex, and specialist practitioners are leaving in large numbers. The Association of Prison Lawyers report published in August 2023 stated that the number of prison law legal aid providers had fallen by 85% since 2008. Three-quarters of prison lawyers surveyed did not think they would be doing prison law legal aid work in three years’ time.

101. We recognise the need to concentrate resources on supporting the early stages of criminal cases, but unless a substantial increase is made to prison law fees, there is likely to be a complete collapse in provision. The failure to adequately remunerate prison lawyers may prove to be a false economy, since without access to legal advice prisoners eligible for parole are more likely to end up spending longer in prison. At a time when the prison population is at crisis levels, it is counterproductive to make it more difficult to hold effective and efficient parole hearings.

102. We recommend that prison law fees be increased to take account of the increasing complexity and importance of this work.

Part 9: LGFS

103. A substantial part of the rationale underlying the decision to uplift solicitors’ fees by 9% rather than 15% was that reform was necessary to the LGFS because of the reliance on Pages of Prosecution Evidence (PPE) as a proxy. Basing payment on pages served rather than on work done incentivised firms to try to obtain cases with a large amount of served material. Due to the disparity between basic fees for cases in which there is a guilty plea and those that go to trial, CLAIR decided that the system created an incentive for the litigator to refrain from advising in favour of an early guilty plea. We prefer (as CLAIR did fleetingly at paragraph 12.22 of the report) to call these “misaligned incentives”,[footnote 30] a fairer description than the pervasive and more pejorative “perverse incentives”, which concentrates only on the potential motivation of solicitors, rather than the manifest distorting effects of disparities inherent in the system in means of funding, and funding of different case outcomes and types.

104. Over the past year work towards reform of the LGFS has been conducted in the LGFS Sub-group and a proposal for consultation was considered by CLAAB in May 2024. As LGFS reform was included within the existing current spending round with no additional funding available, the MoJ work and proposals have all been predicated on a cost neutral basis.[footnote 31] After initial difficulties with modelling,[footnote 32] rather than pursuing work to enable reform of the scheme based on the Magistrates Court banded scheme with standard, higher standard and exceptional non-standard fees as recommended in CLAIR, and removing the reliance on PPE as a proxy altogether, that approach was discarded in favour of a change in flat rate per page lower than the current rate for PPE, replacing the current graduated system. The MoJ proposed that money saved would be redistributed into basic fees, with the intention of narrowing the gap between trials, cracked trials and guilty pleas by apportioning more of the money taken out of PPE to the basic fees for the latter two case groups. It was argued that the proposals would create more certainty for firms in relation to their cash-flow.

105. The effect of the proposals was to reduce the fees in higher paying serious crime, in particular murder and fraud, by 30%, and redistribute that money to other lesser offences. The differential effects of this approach on the profitability and viability (rather than merely cash flow) of criminal legal aid firms across the country with a range of work profiles, have not been investigated. The proposal was not supported by the LGFS subgroup, nor by CLAAB.

106. We note that the MoJ proposals to date have failed to take account of the fundamental principle of fair payment for work done, are substantially influenced by the potential for ‘perverse incentives’ (yet remain based upon PPE), and limited by the lack of available funding. CLAAB cannot recommend any reform to LGFS which is based on this approach, likely as it is to cause significant damage to the sustainability of criminal legal aid firms already in a fragile state. Whilst we understand the reason for the cost neutral approach, the fact that reform of LGFS was scheduled to fall within the time period of a spending period with no available funding should not be a bar to reconsidering the needs of funding where reform has proved impossible to achieve in line with CLAIR principles on a cost neutral basis.

107. Once again, the lack of data to provide effective modelling has been given as one reason for the lack of progress on a Magistrates Court style model. We advise that options for LGFS should be revisited on the basis above, and any gaps in the data rectified to support better modelling by the MoJ.

Part 10: AGFS

108. We have set out above the increases in fees which have been implemented since CLAIR and particular issues with RASSO cases.

109. Substantial increases are necessary to RASSO brief fees. The CBA has set out proposals for the ten most serious RASSO offences.[footnote 33] The lack of available junior counsel has also led to Kings Counsel being engaged by the CPS to prosecute, which creates inequality of arms and disparity in remuneration.

110. Work is progressing on reform of the AGFS scheme to better reflect work done and relative complexity of cases. Complexity markers which indicate increased hours worked are proving difficult to isolate with sufficient data, although in some instances they appear obvious. This work is ongoing with good cooperation.

111. In the interim, the current fee levels are considered inadequate to attract and retain a sufficient body of advocates to attend court in all cases when courts are sitting to capacity. The Bar Council and CBA seek a 10% increase across all fees to address this issue.

Part 11: POCA and alternative sources of funding for legal aid

112. Over the past year CLAAB has considered the possibility of rethinking use of some of the proceeds of crime recovered under the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 (POCA) in the funding of criminal legal aid.

113. Since its introduction in 2002, and the establishment of the Asset Recovery Incentivisation Scheme (ARIS) in 2006, proceeds of crime have been allocated to fund and incentivise the pursuit and recovery of assets and cut crime. ARIS allows a proportion of the proceeds of crime to be redistributed to prosecution agencies involved in the asset recovery process. The Home Office encourages these agencies to invest ARIS funds to drive up performance on asset recovery or, where appropriate, to fund local crime fighting priorities for the benefit of the community.

114. As part of the ARIS allocation, the MoJ currently receives 12.5%, (after a Top Slice deduction), of total confiscation receipts each quarter. This amounted to £7.9m allocated in the year 2022/23.

115. The LAA is not a recipient of ARIS funding, and on one view the ARIS scheme drains the legal aid budget and redistributes funding to prosecution agencies. As a result of the operation of the POCA legislation, the effects of s23 Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012 (‘LASPO’) and s5 Criminal Legal Aid (Recovery of Defence Costs Orders) Regulations 2013 whereby a convicted defendant is required to make a contribution towards the costs of their representation if their means have been assessed as being capable of meeting such payments have been negated. Use of restrained assets for legal expenses related to the offence to which a restraint order is connected cannot currently be used to fund legal representation in order that assets should not be dissipated. Representation is therefore fully funded by criminal legal aid without requirement to make a contribution from income or capital from restrained assets.

116. Post- conviction, income from confiscation orders is distributed to the police, Crown Prosecution Service and HMCTS under ARIS. In 2011/12 the Home Office rejected any ARIS money going to Legal Aid. Subsequently sections 46 and 47 of the Crime and Courts Act 2013, which amended POCA to enable repayment of legal aid from formerly restrained assets in some circumstances were introduced. In 2015 amendments were made to the Criminal Legal Aid (Contribution Orders) Regulations 2013 to allow the Director to take account of restrained assets when deciding on the amount of a person’s capital assets, but no change was made to consideration of contributions from income. Capital Contribution Orders can only be made after victims have been compensated and after a confiscation order has been satisfied or discharged. Between 1 January 2019 and 31 March 2022 there were 75 cases where there was no remaining capital. However, over the same period there were 68 cases where CCOs were made to the value of £2.2m. According to available data there are approximately 464 ongoing restrained assets cases.

117. In addition to funds secured from HM Treasury the LAA recovers around £21,990,000, comprising £21,678,000 recovered in the Crown Court and £312,000 Public Defender Income. With Crown Court representation on Legal Aid presently costing around £555m (LGFS, AGFS and VHCC combined), it is clear that despite s5 Criminal Legal Aid (Recovery of Defence Costs Orders) Regulations 2013 and the system of repayment for convicted defendants, less than 4% of the costs of the Crown Court Legal Aid are recovered from convicted defendants, undoubtedly due to the impecuniosity of defendants in general.

118. In contrast, in the same period where the LAA expenditure on Crown Court cases exceeded £555m, and with a modest £21.9m recovered (a net deficit of £533.1m), convicted defendants paid some £180 million in orders made under the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002. A further sum of some £97m was recovered in forfeiture orders. Recoveries of proceeds of crime have risen by 75% compared to £193.8 million in 2017 to 2018 and are 49% higher than the 6- year median of £227.8 million. Total Asset Recovery income is in the region of £339 million.

119. Of the £180m confiscated from defendants a contribution could be paid to the LAA for criminal legal aid provided for the defence, were payment of a Confiscation Order not, as at present, to take priority over the repayment of defence costs.

120. The Criminal Justice Bill 2024 contained provisions which would have allowed restrained funds to be released for the payment of private legal expenses incurred as part of the confiscation process, with the effect that the LAA would no longer be involved in some POCA cases, since they would be privately funded. This change was recommended in a November 2022 Law Commission[footnote 34] report which made the case for confiscation legislation to permit legal expenses connected with criminal and confiscation proceedings to be paid from restrained funds, subject to judicial approval of a cost budget, in accordance with a table of remuneration set out in a statutory instrument. The Bill was not passed into legislation prior to the recent General Election.

121. The current position is therefore that restrained funds cannot be used to support legal representation, and the LAA is not within the ARIS scheme.

122. The rationale and purpose of distribution under ARIS was clearly justified and a priority when POCA was introduced, and the effect has been to achieve considerable success in setting up and maintaining the POCA regime to encourage law enforcement and prosecutors to invest in and engage with the scheme. The scheme and relevant agencies are well embedded and recoveries have increased substantially in recent years. We raise for consideration whether, with receipts up some 75% since 2017/8 there is scope to widen the use of some of these funds and repurpose them to other priority areas including criminal legal aid.

123. The aim that the LAA could recoup some or all of what has been paid out in legal aid for the benefit of convicted defendants who have sufficient resources to repay can be achieved in a number of ways. Changes in the Insolvency Rules would be required to make the LAA a priority creditor which would allow repayment of legal aid costs prior to a confiscation order. Alternatively, it may be possible to adopt a similar approach to Civil Legal Aid, where a statutory charge is put in place over the assets of those in receipt of public funds. That charge could take priority over the payment of a Confiscation Order. In either case the Legal Aid Agency would recover directly fees paid for convicted defendants where there are sufficient resources. Not all of the ARIS funds would be exhausted, as such change would only relate to those who have been assessed as financially capable of making a contribution to their costs. Much of the ARIS budget, or indeed the total asset recovery of £339m would still be available to meet other priorities including law enforcement.

124. A second approach which would have a similar outcome would be to include the payment of LAA contributions under s5 Criminal Legal Aid (Recovery of Defence Costs Orders) Regulations 2013 within the POCA process itself, were the Act to be amended to enable the Court to make an order as to the amount to be paid to the Legal Aid Agency, in a similar manner to existing provisions pursuant to which Compensation Orders are ordered to take priority over any Confiscation Orders. This would allow Court involvement in oversight and the enforcement of the repayment of the debt.

125. A further alternative would be to include the Legal Aid Agency as a beneficiary of ARIS. MoJ have raised whether this can be best achieved by including the LAA in distribution within the departmental budget of the current allocation to MoJ of 12.5% (after any reduction for project funding), rather than as a free standing recipient after a wider review of the underlying principles of use of proceeds of crime. Another approach would be for LAA to apply for part of the ARIS Top Slice budget, albeit that that is aimed at increasing asset recovery.

126. Overall, we invite the Lord Chancellor to consider that repayment to the LAA of defence Legal Aid from proceeds of crime is justified and consistent with deprivation of assets and the principle that those who can pay should pay for their defence.

Summary of key recommendations

Increases in funding

A. Substantial immediate additional funding above the 15 % recommended by CLAIR is required to meet CLAIR aims.

B. That the second stage of reform to the Police Station Scheme be funded and advanced at pace.

C. We recommend that the Lord Chancellor take a decision as a matter of urgency following the outcome of the Judicial Review, which takes account not only of the terms of the Declaration, but the broader current picture of the continuing and increasing adverse impact on the sustainability of the work of criminal legal aid solicitors of the reduced 9% percentage uplift, manifested in the body of evidence provided to and considered by the Court and made available by the LS and CLSA. The lack of a decision on this fundamental issue impacts on the morale and trust of criminal legal aid solicitors, and is a significant impediment to progress by CLAAB. We advise that retrospective re-running of modelling on the efficacy of lower percentages than 15% when time and inflation have eaten away the value of the full CLAIR uplift is now inappropriate and insufficient, and a prospective approach is needed.

D. Immediate uplift of RASSO fees is required to address the shortages of advocates doing this work.

E. Options for LGFS reform should be revisited on a basis which does not require cost neutrality and any gaps in the data rectified to support better modelling by the MoJ.

F. Separate payment for Youth Court work (whether by increased use of Certificates for Counsel or otherwise) for the work done by solicitors and the Bar undertaking this important and often complex work. This would support the availability to many young and vulnerable defendants of access to the highest quality advocacy in the Youth Court.

G. Increase in Prison Law fees.

Data

H. We recommend the funding and setting up of regular gathering and monitoring of the data set out in ANNEX A and ANNEX B as essential to provide a more granular dataset to assess the areas of the work at the Criminal Bar requiring most attention and the sustainability of criminal legal aid solicitor practices.

I. The requirement for provision of data must be proportionate and even handed. What is required should only be sufficient, and its requirement not an end in itself. There should be no greater requirement imposed on the professions for data to support increases in funding for criminal legal aid than for data used by MoJ to support no increases or cuts.

Impediments to change

J. We recommend a review of LAA digital systems and capacity to assess how and where change and rationalisation would be most effective, in particular in relation to payment of interim fees and the use of the Crown Court means test for committals for sentence. If the systems are not improved there is not only a limited capacity for increased efficiency, but also an increasing risk of widespread disruption should the aged systems fail. Whilst accepting the difficulties with implementation, digital capability cannot be sufficient reason not to introduce change which supports a fair and efficient Criminal Justice System. We therefore recommend that committals for sentence should be treated for the purposes of legal aid as Crown Court proceedings and the Crown Court means test should apply. Implementation of this recommendation would increase the likelihood of guilty pleas and assist in the reduction of the backlog.

Grants

K. We strongly support the CLAIR recommendation for funding of more training grants to support trainees in criminal legal aid firms, which should be in addition to the other funding increases. Without intervention there is no incentive for new practitioners to take up criminal work, and the lack of a pipeline of solicitors undertaking this work would have devastating effects on the fairness of the Criminal Justice System.

L. The Bar Council has put forward a proposal for matched funding for pupillages in criminal sets to ensure a healthy and sustainable Bar. Whilst not strictly within the Legal Aid remit, we recognise and support the need for funding in this area to support practitioners in legally aided work.

Proceeds of crime

M. We raise for consideration whether, with receipts up some 75% since 2017/8 there is scope to widen the use of some of these funds and repurpose them to other priority areas including criminal legal aid.

Annex A: required bar sustainability data

| Intended aim | Data to monitor | Indication of failure to meet aim |

|---|---|---|

| A sufficient number of barristers to meet legal need and ensure good working lives for members of the profession. Sustainable level to be based on analysis of previous data and required throughput of cases. | Number of pupillages in criminal sets Numbers/Retention rate overall Numbers/Retention rate of those fully engaged/mixed practice Average age of practitioners Average age of those leaving practice Numbers of new practitioners (broken down by fully engaged/mixed practice) Case volume/mix modelling per barrister |

Insufficient number of fully engaged criminal barristers to support case volume/mix. |

| A diverse Bar, with entry and ability to progress a career available to all suitable candidates. | Numbers/Retention rate by protected characteristic Profit between groups according to protected characteristic and intersection of sex and ethnicity. |

Lack of diversity and progress evidenced by median profit of any one group with protected characteristic falling below the median overall profit, other variables (such as seniority, experience, region, case mix, work volume) having been accounted for. |

| Types and volumes of work should provide sufficient income to sustain a career at the Bar | Case mix and volume of the AGFS workload against barrister numbers Median profit of the fully engaged at the criminal Bar against whole Bar average Profit between groups at the criminal Bar according to case mix Proportion of criminal barristers with diversified practices |

Unsustainable disparity between the earnings at the criminal Bar and the Bar as a whole, evidenced by the median profit of the fully engaged at the criminal Bar falling below an agreed point of the median profit for the whole Bar. And/or discrepancies between profits achievable for work on different case types of similar weight within the criminal Bar (e.g. RASSO vs murder). |

| Fee schemes and rates for publicly funded work should be index linked or reviewed to provide an income sufficient to sustain all stages of a career at the Bar | Median profit overall (year on year comparison, index linked) Median profit for fully engaged Median profit for those at each level of call (0-2; 3-5; 5-7; 8-15; 16-20; 20-25; 25+) Median profit for KC vs junior |

Median profit falling below that of the previous year when index linked. |

| Regional supply of sufficient members of the Bar to provide representation in all cases | Number of criminal sets in each region Number of criminal barristers in each region (Any Crime and Fully engaged) |

The number of criminal sets or barristers in each region drops below the benchmark. |

| Sufficient numbers of criminal Chambers to ensure representation in all cases. | Number of criminal sets overall Size of criminal sets (average numbers of barristers in each criminal set) Number of pupillages in criminal sets |

The number of criminal sets falls below an agreed benchmark Since September 2022 when the CLAIR increases were implemented, inflation and the cost of living and resources have increased. |

Annex B: Law Society sustainability measures and data collection

| Measure to achieve sustainability | Evidence of failure to meet sustainability measure |

|---|---|

| A minimum number of firms on each duty scheme - minimum of 4 firms on each scheme to prevent conflicts |

RAG rating: - Falling number of schemes with 4 or fewer firms = Green - Static = Amber - Increasing numbers of schemes with 4 or fewer firms = Red |

| Retaining sufficient numbers of duty solicitors. | RAG rating: - Falling by up to 2% annual equivalent = Amber - Falling by more than 2% = Red - Increasing or static = Green |

| A minimum number of duty solicitors per scheme - Minimum of 7 duty solicitors required to ensure that each duty solicitor is not on duty more than once a week. |

RAG rating: - Falling number of schemes with 7 or fewer duty solicitors = Green - Static = Amber Increasing numbers of schemes with 7 or fewer duty solicitors = Red |

| A Minimum % of duty solicitors under age 35 This should be monitored both nationally and per scheme |

RAG rating – national: - Fewer than 20% of all duty solicitors are under 35 = Red - 20-26% under 35 = Amber - 27%+ under 35 = Green RAG rating – duty scheme level: When compared year on year: - Number of schemes with fewer than 20% of duty solicitors under 35 has increased = Red - Static = Amber - Number of schemes with fewer than 20% duty solicitors under 35 has decreased = Green |

| Number of schemes with no new first time duty solicitors in the past 12 months This should be mapped to identify local market failures. |

- |

| Volume of work & travel times per duty solicitor To identify whether individual duty solicitors are getting too many or too few cases. This could be achieved at a high level by looking at the number of cases allocated by the DSCC, divided by the number of duty solicitors, and breaking this down by county/region. |

- |

| Diversity Monitoring to ensure that both the solicitors’ and barristers’ professions are representative of the wider population. |

- |

Annex C : Recommendation on crime lower reform

(Provided in January 2024)

Claab recommendations

Police station and Youth Court reform

Part 1: Police station

A. Introduction

1. The Criminal Legal Aid Advisory Board (CLAAB) was set up as a result of the Independent Review of Criminal Legal Aid (CLAIR), Report by Sir Christopher Bellamy published 29 November 2021. CLAAB met first in October 2022 and an Independent Chair was appointed in July 2023.

2. The membership of the Board includes representatives from the Law Society for England and Wales ( LS), the Bar Council for England and Wales (BC), the Criminal Bar Association for England and Wales (CBA), Criminal Law Solicitors Association (CLSA), London Criminal Courts Solicitors Association (LCCSA), CILEX, the Legal Aid Authority(LAA) and the Ministry of Justice MOJ.

3. The Board acknowledges the constitutional role played by the MOJ representatives in assisting the Lord Chancellor and ministers in formulating policy, carrying out research and preparing consultations and papers concerning aspects of Legal Aid. It is agreed that the position of the MOJ on the Board is therefore different to other participants, and that its approach to all aspects of Criminal Legal Aid will for the most part be set out in consultation documents, and papers which are brought to the Board for discussion and consideration and publicly available.

4. Whilst this Recommendation relates to the subject matter of the Crime Lower Consultation (the current Consultation) and within the time frame of that Consultation, CLAAB Recommendations are made to the Lord Chancellor, rather than in direct response to Ministry of Justice Consultations. The Board considers it helpful to provide a Recommendation to the Lord Chancellor at this stage when the focus is on the subject matter of the current Consultation, but further CLAAB Recommendations on Legal Aid in Police Stations and Youth Court work will follow. Individual participants on CLAAB may provide their own responses to the current Consultation.

5. The CLAAB Terms of Reference require a monitoring of the implementation of the recommendations made by CLAIR , as well as an overview of the Legal Aid provision required to meet the needs of a sustainable and diverse Criminal Justice system.

6. CLAIR recommended a major shift of focus to the early stages of the Criminal Justice system, starting with the Police Station. There is now general consensus that the advice given in the Police Station is an important landmark and provides the first opportunity to impact on the direction of any individual case. As the CLAIR Report recognised, if suspects have good and responsible advice early on, there should be important benefits, and costs savings further down the line. In 2021 CLAIR was unable to be satisfied on the evidence that the Police Station scheme as it existed was working well enough and made Recommendations including that this Board should play a role in monitoring the implementation of the proposed reforms.

B. Background

(a) Current funding for Police Station work