Crafting an intended purpose in the context of software as a medical device (SaMD)

Published 22 March 2023

1.0 Introduction

Failure to adequately define the intended purpose of a medical device will impair any subsequent efforts to comply with medical device regulation. For instance, designing a robust quality management system becomes much more difficult, ambiguity will impede the generation of sufficient clinical evidence, and the implementation of an adequate post market surveillance system will be hampered.

MHRA consider an inadequately defined intended purpose as a potential serious failure to meet key medical device requirements. For instance, where this amounts to a failure to provide adequate information needed to use the SaMD safely and properly.

Proper definition of intended purpose is not only key to minimising the risks that SaMD might pose, meeting the legal requirements of medical device regulation, but properly evidencing the benefits a device presents. Additionally, there are benefits to having a clear intended purpose when engaging with the wider health and social care sector. These can include proper articulation of the value proposition of the SaMD when a robust cost effectiveness analysis is undertaken for evaluation and procurement purposes.

This document provides guidance on defining intended purpose for Software as a Medical Device (SaMD). It is intended to assist SaMD manufacturers in meeting their statutory obligations.

2.0 Document Scope/Application of this Guidance

This document is aimed at manufacturers of SaMD, including standalone software and apps. The purpose of the document is to explain the benefits of having a clear and accurate intended purpose. It has not been specifically drafted for products with hardware components with a medical purpose but also contain software e.g., Software in a Medical Device (SiMD). Nevertheless, the core principles of this document may be of assistance to all medical device manufacturers.

Extending and expanding the intended purpose and alterations in relation to change management activities are outside the scope of this guidance document.

3.0 Definitions

SaMD/Software as a Medical Device: software intended to be used for one or more medical purposes that perform these purposes without being part of a hardware medical device.

Taken from IMDRF/SaMD WG/N10FINAL2013

Intended Purpose: the use for which the device is intended according to the data supplied by the manufacturer on the labelling, in the instructions and/or in promotional materials.

Taken from UK Medical Device Regulations 2002 (as amended)

Intended purpose must be construed objectively from the standpoint of an objective observer[footnote 1]. This is considering the information supplied by the manufacturer on the labelling, the instructions for use and/or promotional materials and technical documentation including the clinical evaluation report.

‘Intended use’ may be substituted for ‘intended purpose’ in all instances.

Indications for use: the clinical condition that is to be diagnosed, prevented, monitored, treated, alleviated, compensated for, replaced, modified or controlled by the medical device. It should be distinguished from ‘intended purpose/intended use’, which describes the effect of a device.

4.0 Linked obligations to specifying an intended purpose

The importance of a sufficiently clear intended purpose is key to meeting various aspects of the medical device regulations effectively. For example, the intended purpose acts as a boundary condition on applying the essential requirements. As is outlined in section 5.4, a broader intended purpose must meet the essential requirements under these broader circumstances. Related to the essential requirements, the intended purpose refines the safety and efficacy questions that require evidencing through the production of technical documentation, risk management and clinical evidence. In particular, an appropriately specific intended purpose assists in identifying relevant user/clinical expectations, abilities and validation requirements that must have sufficient evidence documented against them. Furthermore, labelling requirements must be appropriate to specific users, and quality management system processes must be fit for purpose, e.g., assessing incidents against vigilance requirements and accurate nomenclature. Finally, an appropriately specific intended purpose will aid in managing product updates/defining significant change and mitigate against misuse and off-label use.

5.0 Crafting an Intended Purpose

There are two core aspects to crafting an intended purpose at any given point in the product lifecycle:

1) The key elements of an intended purpose statement

2) The level of specificity of these elements

In order to achieve and maintain regulatory compliance, the product’s technical and clinical evidence base must underpin the intended purpose statement. This must be maintained throughout the product lifecycle and balanced with changes such as product updates, intended purpose expansion and changes in the state of the art. Section 5.3 outlines a general method that can be used to both build an intended purpose early in the product lifecycle, and, to refine the intended purpose over time based on information feedback from evidence gathered to support claims (e.g. Clinical Investigations) and evidence gathered once placed on the market (e.g. Post Market Surveillance Activities and/or Post Market Clinical Follow-up Studies).

The objective of creating an intended purpose is to state the facts about what the medical device is to be used for, with as much clarity as possible. This must be underpinned by detailed evidence and rationales, which must be documented elsewhere (such as the clinical evaluation report) so that the statement can remain clear and concise. For clarity, the intended purpose statement should contain within or be accompanied by, the devices’ indications for use. i.e., specifying the use parameters of the device in addition to the effect the device has. The intended purpose statement must be unambiguous and include only those indications for which a positive benefit-risk conclusion can be demonstrated. Furthermore, when creating the intended purpose statement and supporting documentation, scenarios of reasonably foreseeable misuse must be documented. These scenarios are used to influence the elements below and feed into risk management and design activities.

5.1 Key Elements of an Intended Purpose

Due to the complexity and variety of products and the health and social care scenarios being addressed, an intended purpose can be broken down into four key elements which intersect with each other:

A. Structure and Function of the device

This is a description of what the device’s functionality is intended to achieve. Typically, for software products this should be described as a process with the product inputs and outputs specified, including the purpose and actions to be taken by the user. Additionally, the specific medical condition/situation and position in the wider medical workflow is described. For a well-constructed statement, it should be clear to readers exactly where, how and for what purpose the product fits into a clinical pathway. Furthermore, it should also describe how to validate product performance within this scenario. Detailed information on the product design will be located within the technical documentation, however, when describing the function of the product within the intended purpose, key design information and operating principles are essential to providing sufficient detail.

B. Intended population

It must be possible to understand what population is within scope of the intended purpose. Where there is a failure to stipulate the intended population fully, it shall be assumed in the absence of contrary evidence that the intended population is the largest it could be. Similarly, contraindicated populations should be provided, otherwise the widest application will be assumed. Also, to meet the essential requirements, evidence must be provided to demonstrate that the product is safe and effective across the entire intended population specified. A benefit/risk analysis should be documented on whether to divide the intended population further into sub-populations based on relevant characteristics and the impact of such characteristics on safety and performance. Where the decision to divide into sub-populations is made, a description and rationale provided for the categorisation system must be added to the technical file. Furthermore, if specific sub-population categories are to be excluded from the intended population, this must be explicitly stated.

C. Intended user

The people by whom the device is designed to be used must be specified. This should include roles and responsibilities, and as required, qualifications, training and experience of the user in order to operate the device safely. These should be appropriately specific as should any training required to use the software effectively within any workflow specified in section A. Often the intended use population is a patient population, however, this may differ from the intended user population in the case of tools meant for use by specific users within the health and care system. For SaMDs that have a range of potential users in the health and care system, the primary, secondary and tertiary users should be clearly outlined.

D. Intended use environment

In the case of SaMD, the environmental considerations include not only the physical space but also the virtual environment. Manufacturer’s must define in adequate detail the operating environment, considering interoperability, resource requirements and key functionality that are a requirement of the device. For many SaMD products this wider environment or relationship with physical hardware is key to specify and keep up to date. Additionally, it is important in the context of SaMD, to note that the use of retrospective data to evidence these aspects of the intended purpose must take into account the relevance of such information to the current state of the art. This is to ensure that information specified is still relevant to the data used for evidence.

5.2 Level of detail

Manufacturers must decide what level of detail is appropriate for their overall intended purpose, as an amalgamation of the elements outlined in section 5.1. The choice and use of language can also matter greatly to the clarity and required detail of the statement. Clear, clinically focussed, language and terminology that is common to the indicated workflow and environment should be used. These decisions and the level of detail must be informed by the state of the art, the literature review and wider research. This is used to gain sufficient understanding of the expectations for the healthcare area being addressed and the accepted technical limitations of the product. Here context is key, in some disciplines it may be appropriate to specify certain elements in lower detail than in others, based on risks and best practice within a given medical scenario. Whereas, in others, insufficient detail or nonspecific language will be interpreted as requiring a larger evidence base. Conversely, the expected level of evidence, in a specialised community, for a given use case may also influence the specificity of the intended purpose. If there is still uncertainty as to whether sufficient detail has been reached, greater specificity is generally a simpler and safer approach to take.

5.3 A methodology for crafting intended purposes for SaMD

Many of the common issues outlined in section 5.4 may be avoided if manufacturers follow a logical approach to crafting an intended purpose for SaMD. This section is an effort to outline a process to generate an intended purpose. We encourage manufacturers to follow through this process in the early design phase of product development in order to produce an initial intended purpose. It is also crucial to revisit the process and the intended purpose at key phases of the product development lifecycle including the post-market phase. New evidence and a greater understanding of product performance in a real-world setting, act as a feedback loop to further inform the intended purpose. Also, identified gaps in evidence that restrict the expansion of intended purpose elements should be address through planned activities such as Post Market Clinical Follow-up (PMCF) studies.

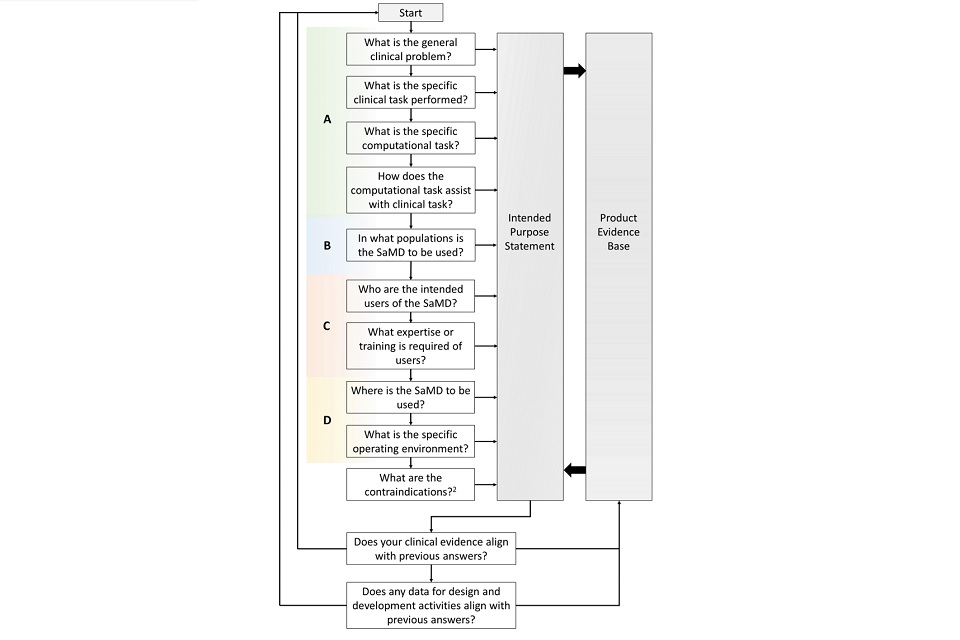

The following flow chart outlines a general method that may be used to craft an intended purpose statement for SaMD. The diagram uses the 4 elements presented in section 5.1 to feed into the intended purpose statement and the interdependency with the product’s evidence base. This approach is cyclical in nature to encourage manufacturers to review both the components of the intended purpose statement and the relationship with evidence throughout the product lifecycle.

5.4 Common issues with SaMD intended purposes

As a general rule for considering whether your intended purpose is suitable, ask whether the intended purpose claims performance characteristics that are testable. If you cannot assemble clinical evidence or run a clinical trial to demonstrate that the device meets a level of performance suitable to the intended purpose, then that intended purpose is likely to be inappropriate. Your evidence base must cover all aspects of your intended purpose and reasonably generalise to cover the specified locations and uses.

The MHRA have identified the four most common issues encountered when crafting an intended purpose for SaMD in particular:

1. Vague intended purposes

The issue of a vague intended purpose arises if a manufacturer fails to provide appropriate levels of specificity when defining their intended purpose. Failure to properly define the intended purpose to an appropriate level of detail will make it difficult to generate robust evidence and run relevant evidence trials with clearly defined outcomes, demonstrating the SaMD meets its purpose.

The MHRA note that breadth of intended purpose can reflect the uncertainty of clinical or commercial development of that device. Nevertheless, MHRA would expect that specificity of intended purpose is still preferred. Additional indications or an expansion to the purpose may be added as evidence at a later date. The MHRA would consider an intended purpose to be vague in a number of ways relating to the elements in 5.1.

a. The manufacturer fails to specify reasonable indications or contraindications for use.

b. The manufacturer fails to stipulate how the output of the SaMD is intended to influence clinical decision-making within a pathway.

c. The manufacturers indicates a number of intended users of the SaMD without specifying how usage might differ between user groups or differentiating between primary and secondary users.

Example

The manufacturer of an AIaMD product for detecting diabetic retinopathy is generating their intended purpose statement. They state that their product is for “monitoring disease progression in patients with diabetes to alert users when to be referred for treatment”. This statement should be augmented by additional detailed information:

- “patients with diabetes” is a broad cohort for an intended use population. The data used to train the AI algorithm was exclusively from patients with Type 2 diabetes between the ages of 40 and 70 years old and was not demonstrated to generalise beyond this range. Therefore, it should be specified as such within the intended purpose statement. People with type 1 diabetes should also be contraindicated in this case. Additionally, the product may only be suitable for early stages of disease progression, and this should also be specified.

- Both the users and the environment should be specified with further detail in the intended purpose statement. The manufacturer should include information on these factors. For example, software is for use in the community by appropriately trained optometrists for referral to specialist care, is a different situation than use within a specialist hospital department by a consultant optometrist for determining treatment decisions. The equipment used, training, and experience expectations on the users will require different evidence based on the use case and without explicit evidence it cannot be assumed that such evidence will generalise even to other parts of the same patient pathway.

An example expanded statement could be:

Optometrists who are trained in the use of the SuperEyeScan9000 software can use the system to assist in the identification of stage 1 diabetic retinopathy in adults between 40 and 70 years old with confirmed type 2 diabetes. The SuperEyeScan9000 software package is suitable for use with Scantastic scanners utilising running operating systems 2.0 or 3.0 and achieves a minimum performance of 97% sensitivity and 88% specificity

2. Multi-purpose devices

The issue of multi-purpose devices, arise in SaMD products when the design of the product has resulted in several functional modules that each serve a different and unrelated medical purpose. Each module has a sufficiently specific intended purposes but, when these plural purposes are collated, there is no sensible overarching intended purpose that could be assessed via a trial. Whilst there may be logical technical or commercial reasons for building products in this manner, not separating out into manageable intended purposes creates, at best, a significantly more difficult clinical evaluation process.

Example

A software product draws inputs from an electronic health record and feeds this information into several modules to produce risk predictions. Each of these risk prediction modules has a defined purpose such as a sepsis deterioration index or risk of cardiac arrest. The manufacturer has grouped these modules together as a single product for patient triaging based on electronic health record analysis. The expected clinical evidence and the risk/benefit calculation for the product must therefore cover all modules. Evidence that only supports the utility of a subset of modules is insufficient.

3. Function Creep

In SaMD the relative ease to iteratively update the product can cause issues with the appropriateness of the intended purpose. All updates should ensure that the product remains compatible and consistent with the original intended purpose. The utility of additional functionally must be supported by further evidence and risk assessments. A SaMD may start out with a clear intended purpose. However, over time, additional functionality is added to the product and the intended purpose becomes vague with a mismatched evidence base. This issue doesn’t relate to the initial creation of the intended purpose but to expanding the intended purpose, it is useful to consider these risks. This is especially for software products which do not qualify as SaMD but where additional functionality leads to product claims that fall within the scope of medical device regulations.

4. Intended purpose is not fully justified by the SaMD evidence.

This occurs when a manufacturer has a sufficiently specific intended purpose and this purpose may be singular, but the purpose is not fully matched by the clinical evidence assembled for the SaMD. An example of this would be an intended purpose with clarity on the intended population, yet the only evidence provided relates to selection of this population. This mismatch of intended purpose to clinical evidence is inappropriate for devices already placed on the market and can be critical to safety that specific populations are either excluded as a contraindication until such a time as further clinical evidence is gathered. It is also important to note that retrospective data only is often inappropriate to evidence an intended purpose in full. As the original data was not gathered to evidence the intended purpose of the device in question.

Example Case Study

A manufacturer creates a SaMD product for detecting suspected gall bladder carcinoma by trained general practitioners (GPs) creates a suitable intended use statement. The product records ultrasound images gathered in real-time as inputs to the software. The SaMD requires the user to contour the gall bladder, the region is then analysed, and the user is provided with a visual readout of the organ dimensions, morphology and density. This aids the user in making a decision on whether carcinoma is present and a classification if so. The product is for use in adults aged 18-70 and is contraindicated for individuals who have undergone a bowel resection or are pregnant. The manufacturer and their Approved Body agree on the product risk categorisation, technical and clinical documentation are submitted for assessment.

However, review of the clinical evidence identifies a few shortfalls. Ultrasound data used during development and testing was gathered at a single UK centre of excellence using one type of ultrasound system, operated by specialist radiographers. Furthermore, this retrospective data had been gathered from predominately female patients (>80%) between an age range of 43-79 years old. The manufacturer had also not assessed the useability of the software with trained GPs or with ultrasound scanners more commonly seen in community settings.

In order to rectify these issues, the manufacturer is required to delay their regulatory assessment to undertake a clinical investigation assessing the useability with GPs and limits the intended use statement to patients between 45 and 75 years old. After a 2-year delay, the product obtains regulatory authorisation, and a Post-Market Clinical Follow-up (PMCF) study is planned to extend the indications of the product to patients between 18-45 years old.

5.5 Added Value

Creating a clear intended purpose is essential for successfully navigating the regulatory requirements for medical devices. In addition, the MHRA encourage manufacturers to maximise the benefits of a clear intended purpose by making this information publicly available. This clarity and transparency can have additional advantages for SaMD when looking to engage with other regulators, distributors, customers and more widely with the UK health and care system.

Some examples of added value may include:

- Streamlining agreements with marketplaces and 3rd party distributers regarding lawful advertising claims.

- Creating or contributing to clinical safety case documentation for health IT system compliance in the NHS.

- Engagement with the National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidance such as the Evidence Standards Framework (ESF) for digital health products or generating a value proposition.

- Improved partnering with health and social care providers looking to maintain or modify their services and staff expectations through incorporating digital products.

Some software products that are not SaMD may in the future become medical devices when they are changed to meet customer needs. If manufacturers intend for products to become SaMD in the future, it can be beneficial to consider creating an intended purpose at this early stage.

-

MHRA decision document on baby/movement breathing monitors provides further information. ↩

-

Contraindications in this context includes patient populations, intended users, operating environment and other restrictions ↩