Commonwealth nCSIRT Capacity Building Programme: self-help guide

Published 8 March 2021

Section 1: Introduction

At the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting in London in 2018, the UK and Singapore signed a Memorandum of Cooperation committing to collaborate to help support implementation of the Commonwealth Cyber Declaration across the Commonwealth. This Guide is the result of that agreement and the subsequent project. aimed at helping Commonwealth countries understand what Computer Security Incident Response Team (CSIRT) development frameworks already exist and identifying whether there is a suitable one that Commonwealth countries could use as its primary source of good practice guidance.

The project workshops introduced Commonwealth Member States to nCSIRT Maturity Frameworks as a way to develop and gauge their national cyber incident response capabilities and to identify and prioritise areas as next steps to maturity. They also provided important opportunities for network building and cooperation on cyber security across the Commonwealth.

1.1 Purpose of the guide

The Guide acts as a reference document for the participating Commonwealth countries to use as a record of the nCSIRT workshops key learning points, materials used and as a library for further resources that can assist them in further developing their national CSIRT. The content is comprised of a combination of workshop content, presentations, panel discussion insights and key outcomes from national discussions.

1.2 What is a nCSIRT and what is its role?

Computer Security Incident Response Teams (CSIRTs) are a formal team or entity which is designed to provide information security incident response services to a particular sector or organisation. CSIRTs can be found across the globe and are used by both governments and private organisations to act as a central point of expertise to manage and mitigate cyber security incidents and to provide practical response and recovery guidance.

For this project and set of workshops, our focus was specifically on National Computer Security Incident Response Teams (nCSIRTs), whose primary objective is to protect and defend nation states from cyber-attacks that can could impact on national or economic security and public safety. With such a broad range of countries from all over the world participating in these workshops, the current capability of nCSIRTs varied greatly, but all participants shared the common objective of wanting to establish or develop a national capability for the prevention, detection and coordination of cybersecurity incidents.

As we discovered during the focussed workshop discussions, some countries have well-established nCSIRT capabilities that have been developed over many years, whilst others are still early on in their journey and have yet to establish a formal team. Not all nCSIRTs necessarily have to be comprised of large teams of analysts, incident responders and forensic experts who have a 24/7 capability to detect, prioritise and respond to cyber incidents. For some countries who may not have the resource and capability to immediately establish a full incident response capability, other services such as national awareness campaigns, skills development programmes and threat intelligence sharing mechanisms are important achievements too.

1.3 Key international organisations

In addition to the UK and the other participating countries sharing their national knowledge and expertise, there were a number of established international organisations present who also provided advice and guidance to the delegates.

These were:

FIRST (Forum of Incident Response and Security Teams)

FIRST was first formed in 1990 and is a recognised global leader in incident response. It was set up to try and resolve an evolving issue whereby the global growth in incident response teams was resulting in a range of organisations with differing purposes, funding mechanisms, reporting regimes, language and international standards. FIRST was initiated to enable incident response teams to more effectively respond to security incidents by providing access to best practices, tools and trusted communication with member teams.

FIRST is comprised of a wide variety of organisations from across the world including educational, commercial, government and military entities. These members develop and share technical information, tools, methodologies, processes and best practices. FIRST members use their combined knowledge, skills and experience to promote a safer and more secure global electronic environment, as well as promoting the development of quality security products, policies and services.

During the regional workshops, we were joined by FIRST Chairman Chris Gibson (at the Asia-Pacific and London events), and FIRST Board Members Maarten Van Horenbeeck (at the African event) and Gaus Rajnovic (at the Caribbean and London events).

Website: https://www.first.org/

The Global Forum for Cyber Expertise (GFCE)

The Global Forum on Cyber Expertise (GFCE) is an international platform for countries, organisations and private companies to exchange best practices and expertise on cyber capacity building. GFCE members are drawn from academia, the technology sector and NGOs with the aim of identifying successful policies, practices and ideas to help build cyber capacity.

Following its initial launch five years ago, in 2017 the GFCE’s focus shifted from building and expanding the network to positioning the GFCE as a coordinating platform for Cyber Capacity Building. That year the GFCE community endorsed the Delhi Communiqué on a GFCE Global Agenda for Cyber Capacity Building, which prioritises five themes and calls for action to jointly strengthen global cyber capacities. One of those five key areas is Cyber Incident Management and Critical Information Protection and the GFCE runs a formal Working Group which aims to strengthen international cooperation in this area and avoiding duplication of efforts.

This year the GFCE has also launched an exciting knowledge sharing portal for the international cyber community. Known as Cybil, it is a publicly available portal where members of the international cyber capacity building community can find and share information to support the design and delivery of programs and projects. The portal currently lists over 550 international cyber capacity projects, 70 capacity building tools, 69 best practice guides and over 400 actors and stakeholders to collaborate with.

Website: https://www.thegfce.com/

International Telecommunications Union (ITU)

The ITU is a vast international organisation which brokers agreements on technologies, services and the allocation of global communication system resources. Its current global membership includes 193 Member States as well as some 900 companies, universities and international and regional organisations which forms a community of more than 20,000 professionals.

During the regional workshops, we were joined by members of the ITU Telecommunication Development Sector (ITU-D) who explained the ITU’s work with Member States to build capacity at national and regional levels, deploy capabilities, and assist in establishing and enhancing nCSIRTs. Their primary involvement is to conduct a CIRT Readiness Assessment which aims to define the country’s readiness to implement a national CIRT. To date the ITU has completed such assessments for 76 countries.

Following a CIRT readiness assessment, the ITU-D can assist with the planning, implementation, and operation of the CIRT, and the ITU has helped establish or enhance CIRTs in 14 countries.

Website: https://www.itu.int/en/Pages/default.aspx

Section 2: Countries with an existing nCSIRT capability

2.1 How do I assess the maturity of my nCSIRT?

A key part of the workshops was to introduce the participating Commonwealth countries to nCSIRT Maturity Frameworks to develop and gauge their national cyber incident response capabilities.

The principle model used globally is the Security Incident Management Maturity Model (SIM3). This is a community driven effort under the stewardship of the Open CSIRT Foundation (OCF) (https://opencsirt.org/). The model can be applied to measure the maturity of a CSIRT and was acknowledged by the GFCE and National Cyber Security Centre Netherlands (NCSC-NL) as the mainstay for the GFCE-supported “GFCE CSIRT Maturity Kit” (CMK) in 2015. SIM3 is also in use with the Task Force on Computer Security Incident Response Teams (TF-CSIRT) for the optional certification of their members, with the European Union Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA) for maturity development of the EU “CSIRTs Network”, and with the Nippon CSIRT Association (NCA). Continued global collaboration with the GFCE, FIRST, ITU and other international stakeholders, has led to a shared understanding in which SIM3 is a benchmark for assessing CSIRT maturity.

The SIM3 model itself identifies 44 parameters that measure four categories of maturity:

- Organisation

- Human

- Tools

- Processes

These categories have been chosen in such a way that the parameters are as mutually independent as possible. SIM3 measures the levels for each parameter. Simplicity has been reached by specifying a unique set of levels, valid for all parameters in all of the categories:

- 0 = Not available / undefined / unaware

- 1 = Implicit (known/considered but not written down, “between the ears”)

- 2 = Explicit, internal (written down but not formalised in any way)

- 3 = Explicit, formalised on authority of CSIRT head (“rubberstamped” or published)

- 4 = Explicit, actively assessed on authority of governance levels above the CSIRT management on a regular basis (subject to control process/review)

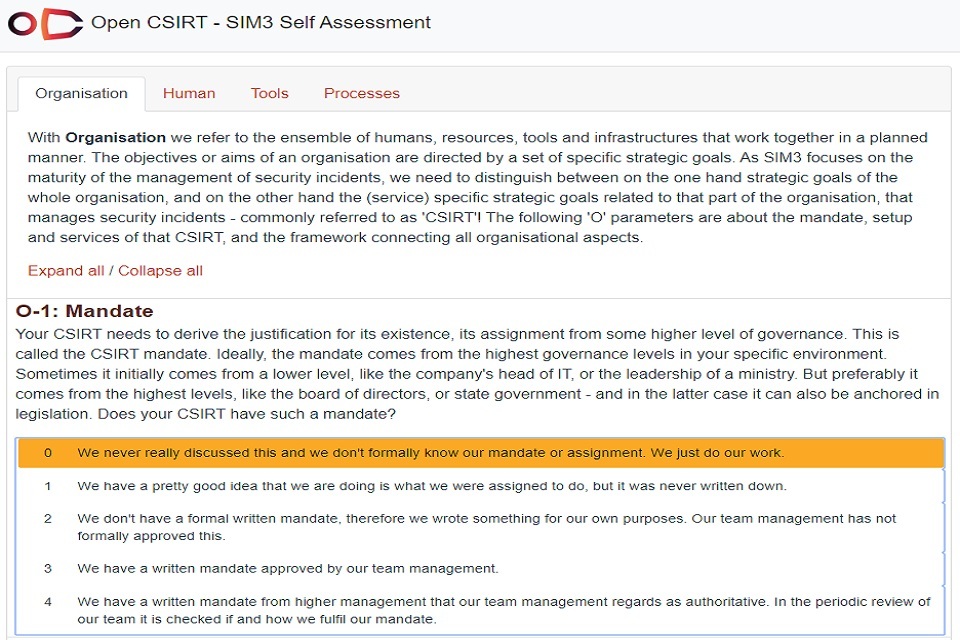

As an example, the screenshot below shows the first question under the Organisation category:

Shows the Open CSIRT Foundation (OCF) online self-assessment tool for SIM3 which all types of CSIRTs can use. The tool uses 44 parameters in 4 categories to measure maturity of the organisation’s function: organisation, human, tools and processes.

A judgement is made as to which of the parameters, 0 to 4 above, is most suitable. See full version of the 44 parameters.

2.2 What do these results show and how should I interpret my results?

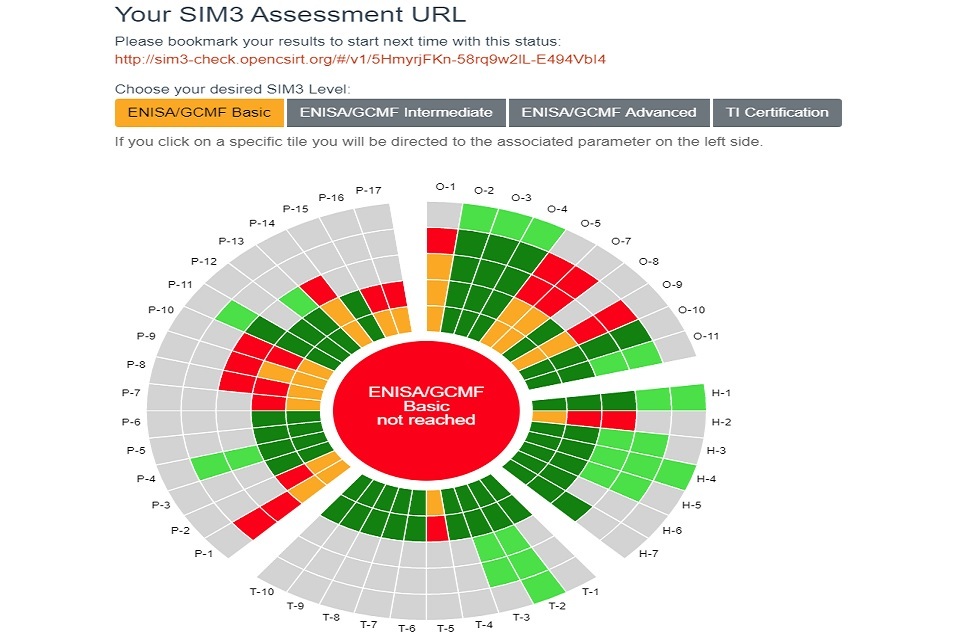

Once all 44 parameters have been assessed, the results of the self-assessment are presented in a diagram which is colour coded to indicate where a given response sits on the maturity framework. Figure 2 is a screenshot of an example assessment which gives an indication of the current level of maturity against the 44 parameters.

An example of the result of a SIM3 assessment completed by an organisation. The visual result shows where there are areas of strength and weaknesses so the nCSIRT maturity can be improved. Answers are scored 0-4 and assessed against 4 SIM3 levels.

Looking at the example in Figure 2, just above the results ‘circle’ there are four selectable tabs which show the desired SIM3 levels of ‘ENISA/GCMF Basic’ through to ‘TI Certification’. In the image above this is currently selected to ‘ENISA/GCMF Basic’, so the results are indicating the current levels of maturity against meeting the ENISA/GCMF Basic level. The results show that the CSIRT has selected a score of two for Parameter O-1: Mandate, but the colours indicate that the required score to meet ENISA/GCMF Basic is actually three. Similarly, the results show that the team has scored four on the parameters of O-2: Constituency, O-3: Authority and O-4: Responsibility, and this exceeds the ENISA/GCMF Basic requirement of three.

This self-assessment can be used to help a nCSIRT identify where it currently is in a strong position, but more importantly, it can be used to identify weaknesses and areas for development to help improve nCSIRT maturity.

2.3 Where can I go for more assistance?

Community driven efforts to help assess and develop nCSIRT maturity are conducted under the stewardship of the OCF. During the regional workshops, the subject matter experts from FIRST also demonstrated the important role that ENISA plays in this space. Whilst their initiative and nCSIRT maturity evaluation process is primarily aimed at EU CSIRTs as part of the EU Network and Information Security Directive (NIS Directive), their work on maturity self-assessment is of use to all types of CSIRTs.

https://www.enisa.europa.eu/topics/csirts-in-europe/csirt-capabilities/csirt-maturity

ENISA CSIRT maturity assessment model is an updated version of the “Challenges for National CSIRTs in Europe in 2016: Study on CSIRT Maturity” which they originally published in 2017. The study takes all relevant information sources into account, with a special emphasis on the NIS Directive, the various ENISA reports on CSIRT capabilities, maturity and metrics, and on the SIM3 maturity model for CSIRTs which is a widely used best practice document.

2.4 Typical development challenges and how to overcome them

Analysis of the SIM3 results which were formally submitted back to the project team revealed that the most common development challenges were focussed around the training and retention of staff and a lack of formal nCSIRT processes.

In response to this, the participants were given a dedicated session on nCSIRT career pathways and how to create a development environment where staff can be trained effectively and encouraged to grow their cyber career in government and without moving across to potentially more lucrative private sector jobs (further details are provided in Section 4 below).

Generally, the majority of the SIM3 results were limited due to low scores where processes are not documented, measurable and repeatable. Incident Prevention, Detection and Resolution Toolsets were also highlighted as an issue, which is why a large part of the second day of the London workshop focussed on these areas to help the participants develop a better understanding of where they could access further help and advice (see Section 4).

Documenting, measuring and repeating processes can be resolved relatively easily, provided the time and resources are dedicated to capturing and updating processes. The results themselves showed that the countries of Uganda, Vanuatu and Brunei scored particularly highly in these areas, so the group now has identified pockets of expertise who they can potentially consult with and benefit from lessons learnt in the future.

2.5 Next steps

The ENISA methodology, which was promoted at the regional workshops, is to take a step-by-step approach leading beyond CSIRT “Certification” level. A growth path is suggested that aims to reach the Basic level within one year, Intermediate two years later and Certifiable a further two years later. Achieving even a Basic level would enable a nCSIRT to interact and cooperate with other nCSIRTs on incident handling and the higher levels could allow the nCSIRTs to interact on all steps, including working pro-actively together.

In addition to utilising the multitude of resources and advice available online, the regional workshops discussed several practical steps that countries can initiate towards increasing maturity as per the SIM3 model.

The first proactive step is to ensure that any nCSIRT team has completed a RFC2350 document. The purpose of the RFC2350 is to provide a framework for considering the most important subjects relating to incident response and was created to help CSIRTS identify what are the main expectations of a formal CSIRT team.

See the full RFC2350 specification.

Each workshop received a masterclass delivered by the respective subject matter expert from FIRST, and as an example of what a ‘good’ RFC2350 looks like, the following document from the Austrian CERT (CERT.AT) was highlighted and discussed with the attendees: https://www.cert.at/about/rfc2350/rfc2350_en.html.

Section 3: Countries without an existing nCSIRT capability

3.1 How do I assess my current capability?

For those countries who do not currently have a formal nCSIRT capability, it is very difficult to assess their level of existing capability. Although the SIM3 model is primarily designed for existing CSIRT teams, during this project the countries without a nCSIRT were also encouraged to use the template to assess what capability they have. This was with the caveat that not all the questions would be answerable, but by following the process, participants would understand the many processes and organisational requirements of setting up a CSIRT.

3.2 How do I identify the steps needed to create a nCSIRT capability?

As described above, the 44 parameters of the SIM3 model provides a structured outline of what is required of an CSIRT, and what other considerations need to be addressed in order to improve maturity. As part of the workshops, participants who have not yet created a formal nCSIRT were also encouraged by FIRST to complete an RFC2350, again to help establish what steps were required to establish one.

For some of the countries in attendance who have very limited budgets and resources, setting up a national capability with dedicated staff is not a realistic prospect in the short term, so the discussions focussed on what countries could do to address the increasing cyber security problem. The use of existing online resources and engaging with international organisations such as Get Safe Online was encouraged as they could advise on how to formulate a national cyber awareness campaign which is an important core element of any national cyber security response.

The key advice is to develop a strategy for what kind of nCSIRT you want to create. Some countries have responsibility for dealing with and coordinating all types of cyber security incidents in a country, but some have very clear remits to only deal with incidents that affect government or military domains. Determining exactly what a nCSIRT does do, and more importantly what they do not do, is a critical part of any strategy and needs to be set out from the start.

3.3 Typical challenges and how to overcome them

The common challenges that arose during the discussions were not having enough skilled staff with suitable cyber security experience, competing priorities at a national level, and not having a political champion who supported the cyber security agenda. Participants were also frustrated by a lot of wasted effort and resources when political mandates and government roles constantly changed.

One of the key means of overcoming a number of these issues is to set a clear cyber security strategy and vision so even if there were changes, the strategy and longer-term vision are still there to be followed. Where some countries have been particularly successful in their cyber security development, their participants emphasised how critical it had been to create a strategy to focus efforts on and also stressed the importance of having a senior political champion who could support the cyber security agenda and ensure the necessary resources were available. As an example, here is the UK National Cyber Security Strategy 2016-2021.

During the group discussions, it also became apparent that there were a number of examples where countries who had previously struggled to get traction in national debates on the importance of investment in cyber security, found that it took an actual cyber incident that affected a senior official or department before the issue was considered and resources were found. That is not an excuse to wait until a serious incident occurs before developing a national capability, but for some countries the issue of cyber security is competing against other potentially greater existential threats such as climate change.

3.4 Next steps

Towards the end of the formal discussions at the London workshop, each of the countries who currently do not have an nCSIRT capability considered and agreed to three practicable steps which would form part of their immediate action plan. Rather than be too optimistic and choose complex actions such as ‘Setting up a formal nCSIRT capability by the end of 2020’, the participants were encouraged to start small and consider realistic and achievable activities which would at least enable them to build a capability gradually. Whilst a small number of this group do have formal plans to officially roll out their new nCSIRTs in 2020, the most popular actions set by the remainder of the group are listed below:

- conduct national awareness campaigns for vulnerable groups

- utilise free open source monitoring tools to help inform current threat reporting

- develop a Cyber security policy and strategy alongside the ITU

- set minimum operating standards for data centres and government suppliers

Further information and advice on how to help progress these proposed actions was delivered at the London workshop from subject matters experts at the UK National Cyber Security Centre, Get Safe Online, FIRST, and through ongoing consultation with the ITU (further details are provided in Section 4 below).

Although this project formally draws to a close at the end of February 2020, the facilitation team will remain available to answer any future questions or requests for further information from any of the teams who wish to continue developing their action plans throughout 2020.

Section 4: Key workshop themes

During the discussions at the regional workshops and from the follow up correspondence ahead of the final London workshop, a number of key themes and requirements emerged. These subjects focused on several dedicated streams which were run as part of the London event:

- open source monitoring tools

- international standards

- technical writing

- nCSIRT/cyber career pathways

- national cyber awareness campaigns

4.1 Open source monitoring tools

An area which was unanimously requested by the participating countries in the lead up to the event, was information regarding Open Source Monitoring Tools. Not all of the countries in attendance had the resources or capability to run fully functioning Service Operation Centres (SOCs) at a national level, so one of the most cost-effective options in their early development is to use open source monitoring tools to identify common threats.

The Chairmen of FIRST, Chris Gibson, delivered a detailed presentation which provided an overview of the most useful and widely available open source tools including an information sharing platform called The Hive, an event aggregator called Splunk, and a tool known as “Elk” which is the acronym for three open source projects called Elasticsearch, Logstash and Kibana. Chris also highlighted that Shadowserver and Team Cymru are both reputable private companies who work with national CERTs, and many of the participating countries had already raised that they are indeed using data feeds from those companies already.

See Chris’ full presentation on Open source monitoring tools.

4.2 Technical writing and incident management

Feedback from the regional workshops and the questionnaires that were completed by the participants highlighted a requirement for more information about Incident Response management and how to communicate technical messages in an understandable way. In the first session to address this, the participants heard from Paula Walsh, Head of Cyber Policy at the UK FCDO. She set out the importance of formal strategies as key communication documents which portray what you want to achieve in language that Ministers, and the public will understand. The UK National Cyber Security Strategy was used as an example and how the vision and messaging can be explained by three simple aims to Defend (against cyber threats), Deter (our adversaries) and Develop (our skills and capabilities).

One of the key findings from the SIM3 self-assessments that were shared with the project team showed that the main reason that many countries’ maturity results were not as high as they might have expected, was because their formal incident response processes were not properly documented and updated. In response to this, Gaus Rajnovic from FIRST delivered a session on Incident Management and based on the ISO/IEC 27035 Security Incident Management standard. He stressed the importance of creating and updating policies, having defined incident management plans and the ability to test and evaluate performance. Whilst learning from each other is very beneficial and encouraged, it is important to understand that teams should not always blindly copy what others are doing but recognise reasons why others are doing things in that way and adapt accordingly. With regards to communicating messages, one size does not fit all, and the content, frequency and language must be considered to satisfy the needs of the recipients.

See Gaus’ full presentation on technical writing and incident management

4.3 International standards

One of the objectives of this project was to help the participants to understand international cyber security standards and the importance of promoting a set of basic technical controls to help organisations protect themselves against common online threats. At each of the regional workshops they were given a presentation by Brian Lord, Managing Director of PGI and former Deputy Director of Intelligence and Cyber Operations at GCHQ, who described the most relevant international standards to nCSIRTs and some of the current challenges with implementing them.

Brian described the challenge both in terms of organisational standards (such as Cyber Essentials and ISO27001) and individual skills standards (such as penetration tester accreditation and incident responders). Some countries present have already implemented ISO27001, but many organisations can find that this standard is too expensive and resource heavy to implement effectively. Brian gave a background to the UK’s experience of their 10 Steps to Cyber Security in 2012, and the how the Cyber Essentials (CE) standard was subsequently developed to provide an evidence-based solution aimed to defend against the most common types of attacks. CE was not intended to be a silver-bullet for all forms of cyber attack but offers organisations a first step in their journey to protecting themselves in cyber space.

Brian also touched on more detailed standards such as Cyber Essentials +, ISO27001 and the EU’s Network and Information Systems Directive (NISD) Cyber Capability Framework which is mandated for Operators of Essential Services. It was reassuring to learn from the discussions and the final workshop in London, that a number of participating countries have defined, and in some cases adopted, ISO27001, as a way of demonstrating their commitment to international security standards.

4.4 nCSIRT/cyber career pathways

The widespread shortage of suitably skilled staff who could help improve the capacity and capability of national CSIRTs remains one of the greatest challenges across this sector globally but is often felt more keenly in smaller nations that have traditionally lacked the access to education, jobs and experience within cyber security. It was emphasised that this is not a unique problem, and the UK itself faces the same issues with a lack of cyber security professionals. It is estimated that there is a shortfall of nearly three million cyber security professionals worldwide, with over two million of those being in the Asia-Pacific region alone. It also remains a largely male dominated industry with only approximately 20% of the global workforce being female.

In response to this, Sebastian Madden from PGI discussed how to develop a cyber security career path and training plan. He highlighted how it requires a comprehensive approach to training to help build cyber security competence in IT teams and how reskilling staff as cyber professionals in house may be a much more affordable solution when compared to hiring externally. In what he referred to as a range of ‘interventions’, he promoted the use of on-the-job training, mentoring, practical lab work, cyber technical challenges, and certified training. The use of the Institute of Information Security Professionals (IISP) skills framework was also explained to demonstrate the various career path options that could be pursued.

Running cyber security Bootcamps was also suggested as an excellent way of rapidly developing basic skills, but also to identify additional talent, and how tailored training plans can be delivered using a mix of practical training, theory, demonstration and practice.

See Sebastian’s full presentation on nCSIRT/cyber career pathways

4.5 Critical National Information Infrastructure Protection

Another stream which was specifically requested to be addressed at the London workshop was on the role of nCSIRTs in Critical Information Infrastructure Protection (CIIP). Dr Martin Koyabe, Head of Technical Support and Consultancy at the Commonwealth Telecommunications Organisation (CTO), described the importance of establishing CIIP and the steps that can be taken towards establishing and defining a nation’s critical information infrastructure. Once established, these critical assets must be prioritised and continually assessed and managed on an ongoing basis as the nature of the cyber threat is always evolving.

Martin also discussed the importance of establishing Public Private Partnerships (PPP) as trusted relationships between governments and private technology firms is crucial for information sharing and collaboration.

See Martin’s full presentation on Critical National Information Infrastructure Protection.

4.6 National cyber awareness campaigns

During the group discussions at each of the regional events, it became obvious that conducting national cyber awareness campaigns was a crucial priority for most (if not all) countries. Subsequently, we organised for Peter Davies, Global Ambassador for Get Safe Online, to run a masterclass on “The use of national cyber awareness campaigns to help mitigate against cyber threats”.

Peter highlighted that cyber security is first and foremost about human beings not technology, and that countries and organisations cannot hope to achieve cyber security without a cyber security culture. They key to this is public awareness and education.

Get Safe Online has already been involved with a number of countries who were in attendance at the workshop, so it was very useful to have their input and feedback on the experiences with national cyber security awareness campaigns. Peter also highlighted some of the practical challenges of such campaigns and ended with several recommended steps on how countries could proceed if wishing to run an awareness programme, which are included in his presentation.

See Peter’s full presentation on national cyber awareness campaigns.

Section 5: Key lessons learnt and conclusions

Each of the regional workshops were characterised by a large amount of open and honest discussions and, as a result of this excellent collaboration, several key outcomes and information sharing opportunities were achieved.

At the first regional event in Africa, as would become a common commitment at all the regional events, the participants all agreed they would attempt to complete either a full SMI3 self-assessment or an RFC 2350 before the London event. This would enable each country to gain an indication of what level of maturity they were currently at, and help identity any particular areas of weakness. Whilst no formal commitment was made for each country to share their full self-assessment results with each other, if they were willing to directly share their results graphs with other regional partners, it could be used to identify areas of strength or weakness where countries could help each other.

During the Africa regional event, the Ghana nCSIRT agreed to the first of a number of planned exchange visits between African national CIRTs to share experience and best practice. The first of these visits occurred immediately after the workshop, with the Ghanaians hosting visits by Uganda and Tanzania.

Several the African Commonwealth countries already have an established nCSIRT capability and they were willingly sharing a lot of their knowledge and experience with some of their less mature neighbours. Important formal relationships were forged and strengthened at the event, and in order to improve information exchange throughout the wider group, a What’s App group was also created for everyone to contribute to.

The collaborative opportunities were also replicated at the Caribbean workshop where the group also set up their own What’s App group. With the geographical dispersed nature of the Caribbean and the limited resources available to some of the smaller islands, the pooling of knowledge and resources could be an excellent mechanism to help address the various threats they face. Following similar conversations at the African event, this workshop further highlighted the demand for a more formal (and secure) information sharing solution which reflects best practice information sharing procedures such as the traffic light protocol. The facilitation team and subject matter experts from FIRST undertook to find a suitable solution and this work is currently ongoing at the time of publication.

The Caribbean workshop also highlighted a very useful example of where a country may be performing all of the expected roles of a nCSIRT, without actually having designated it as an official nCSIRT. During the group discussions, the delegates from St Lucia described their roles and responsibilities and, although they do not formally identify themselves as a nCSIRT, they do indeed perform the role of one. Due to the open nature of this meeting, St Lucia used one of the breakout sessions to present their current draft business plan to the other delegates. This enabled those without such a plan to see what was involved in creating one, but also enabled St Lucia to gain vital feedback and suggested changes from the other countries during the peer review.

The final regional workshop in Singapore followed a similar path and all countries represented at the workshop agreed that the group should continue to develop an informal network of Asia-Pacific nCSIRTs to engage with each other and share information, experience and best practice on nCSIRT development. Like the Caribbean islands, a number of the Pacific Islands were particularly keen to find an information sharing platform in order to share knowledge and help pool resources and expertise.

A number of clear requirements came out of all three regional events in that each participating country clearly understood the benefits of increased collaboration and sharing best practice. Many participants face the same common barriers to progression including the issue of sustainable funding, a shortage of skilled staff, gaining political support and a lack of public awareness. However, through the panel discussions under the guidance of the facilitation team, it was possible to identify areas of expertise within each region who could lead and advise others on possible solutions. A number of these topics were also selected to be discussed at the final London event where some of the main challenges and solutions could be discussed in more detail.

Whether the participating country had an existing nCSIRT capability, or if it simply remained an aspiration at this stage, at the conclusion of the event each country chose three basic steps which they would pursue to enable them to start or develop their in-country capability. Whether these steps included developing a national cyber awareness campaign, training staff in the use of OSINT tools or the implementation of international standards, the participants left London with a network of likeminded experts who they could collaborate with, or the knowledge and contacts to help them find the information they needed. As mentioned, the facilitation team and FIRST also remain in dialogue about a possible solution for an information sharing platform which could not only be used by each regional grouping to communicate and share, but also across the whole Commonwealth network to benefit from some of the clear synergies that exist between the Caribbean and Pacific Islands.

Section 6: Feedback

We welcome your interest in this Guide. The UK Government is keen to better understand the impact of the projects that it funds and whether they have achieved the desired outcomes. Your feedback on how you have used this guide and whether it helped improved cyber security incident response would be valuable information we can use to help design future projects. Please contact the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office at CyberCapacity.Building@fcdo.gov.uk to share your feedback.

Annex A: Further sources of information

Measuring nCSIRT Maturity

- SIM3 Model from The Open CSIRT Foundation (OCF)

- ENISA CSIRT Maturity Guidance

- GFCE CSIRT Maturity Initiative

- The RFC2350 specification

- RFC2350 from CERT.AT

Key International Organisations

- FIRST (Forum of Incident Response and Security Teams)

- The Global Forum for Cyber Expertise (GFCE)

- UK National Cyber Security Centre

- International Telecommunications Union (ITU)

- Commonwealth Telecommunications Organisation

- Organization of American States

Cyber Security Strategy and Policy Assistance

Open Source Monitoring Tools

- The Hive

- Splunk

- Elk - Elasticsearch, Logstash and Kibana

- Shadowserver

- Team Cymru

- AlienVault® OSSIM™, Open Source Security Information and Event Management (SIEM)

Conducting cyber exercises

- National Cyber Security Exercise – Exercise In A Box

- Centre for Internet Security – Tabletop Exercises

- Mitre Cyber Exercise Playbook

Other international publications of interest

- The CSIRT Handbook

- GFCE Global Good Practices on National Computer Security Incident Response Teams

- Cyber Security Capacity Portal (Oxford University)

- ITU Cyber Strategy Guide

- How to Measure Anything: Finding the Value of Intangibles in Business, Douglas W. Hubbard

- How to Measure Anything in Cybersecurity Risk, Douglas W. Hubbard and Richard Seiersen