2. PLACES: empowerment and investment for local communities

Published 9 August 2018

Applies to England

Introduction

‘Global Britain’ is rooted in ‘local Britain’. Our success in international trade, diplomacy, and culture depends on the strength of our communities at home. Businesses which deal nationally and internationally still operate in local places. As individuals we benefit from the cultural and economic opportunities that globalisation brings. We also benefit from a sense of belonging geographically, from feeling connected to our neighbours, and from taking some responsibility for the places which are ours.

The Industrial Strategy is the government’s long-term plan to boost productivity and the earning power of people in all parts of the country. As explained elsewhere in this Strategy (see Chapter 5 ‘The public sector’, a new model of public services, rooted in communities, is emerging. And through its devolution programme the government is actively transferring power from Westminster to local authorities, including the new city regions and combined authorities.

The government’s vision is that in the future, the public sector will take a more collaborative place-based approach. By working with service providers and the private sector as well as individuals and communities in a place, we will make more sensitive and appropriate policy, achieve better social and economic outcomes and make brilliant places for people to live and work in.

A place-based approach calls on people to work differently. Rather than public servants working in silos accountable to Whitehall, they need to work together and with local communities to co-design services and pool budgets. While most public servants welcome this ambition, the reality of the structures they work in often makes it difficult. As a review of evidence on place-based work concluded, the approach “takes time”, “It is tricky and uncomfortable by nature and requires open, trusting relationships”, and “Change needs to be embedded in the whole local system”.[footnote 35]

Key to successful place-based work is involving the voice of local people in the decisions that affect them. People, communities, and services operate in complex systems. Bringing services closer to those they are intended to benefit and putting communities at the heart of their design and delivery can improve how services work and their impact for citizens. Throughout the engagement exercise the government heard that communities and local people often know best what their own local challenges are and what assets they have, but that they cannot achieve change alone. They need to be informed, equipped, and trusted to make decisions on matters that affect them.

Local partnerships involving the local community are key to tackling local crime, including serious violence which is disproportionately concentrated in certain places. There is strong evidence that place-based interventions with proactive prevention activity is successful in reducing crime in these ‘hotspot’ areas. It is crucial that communities including young people living there see this as a shared problem which they are committed to addressing, and that they are given the support and connections with programmes to do this, and this in turn, builds confidence and isolates offenders.

The government recognises that places are not all starting from the same point. The factors that distinguish communities from one another, such as levels of deprivation and segregation, will affect a community’s ability to take greater control. The government will take steps to ensure that efforts to empower communities described in this Strategy have the potential to benefit all communities, regardless of circumstance.

Mission 4: Empowerment

Onward devolution

The first requirement for a flourishing community is empowerment. Previous attempts to ‘regenerate’ local places have under-achieved because well-meaning schemes were imposed from outside, and therefore lacked both local knowledge and legitimacy.[footnote 36] The government is determined to ensure that place-based solutions are designed and delivered with and by the people they are intended to help. This includes a central place for civil society organisations.

There is evidence that people want a greater say over the decisions that affect their neighbourhoods.[footnote 37] The Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport’s Community Life Survey indicates that only 26% of people feel able to influence decisions affecting their local area.[footnote 38] This also came through strongly in the responses to the engagement exercise. For example, an organisation said “localism must be about giving voice, choice, and control to communities that are seldom heard by our political and economic institutions.”

The government has an ambitious programme of devolution. It has sought to decentralise power through structural and legislative changes. The introduction of directly elected mayors with specific powers and responsibilities has enhanced local control and accountability. In addition, the Community Rights introduced through the Localism Act 2011 created new rights for communities, giving them an opportunity to take into local ownership community assets, shape planning and development in their area and gave options for voluntary and community organisations to deliver local services. Just as the UK is bringing back power over its laws, money, borders, and trade from the European Union, so local places are taking economic, social, and cultural policy away from Westminster and Whitehall.

The government wishes to go further and devolve more power to community groups and parishes. As proposed by the National Association of Local Councils and the Local Government Association there are opportunities for ‘onward’ devolution of service delivery and decision-making beyond the large regions to smaller geographies.[footnote 39] The government will explore with the National Association of Local Councils and others the option for local ‘charters’ between a principal council, local councils, and community groups setting out respective responsibilities. This could include joint service delivery or the transfer of service delivery responsibilities to local councils, parishes or community groups, the transfer of borough council assets to local councils, or from councils to parishes, and the opportunity for councils or parishes to ‘cluster’, that is to form a consortium with sufficient scale to commission or deliver larger service functions. There are also useful models in other parts of the public sector - notably health and social care systems - which are building formal alliances with the local social sector to co-deliver services.

Participatory democracy

A vital part of building a strong civil society is creating opportunities for people to participate in the public decisions that affect their lives. Many people feel disenfranchised and disempowered, and the government is keen to find new ways to give people back a sense of control over their communities’ future.[footnote 40]

Civil society organisations play an invaluable part in helping councils to address the challenges they face, working as partners to help overcome the barriers to engagement experienced by particular groups. This allows government to speak with those audiences through trusted local messengers, and enable everyone to have their say in our democratic processes.

Participatory democracy methods, such as Citizens’ Juries, can make a profound difference to people’s lives: evidence shows that enabling people to participate in the decisions that affect them improves people’s confidence in dealing with local issues, builds bridges between citizens and the government, fosters more engagement, and increases social capital. It also increases people’s understanding of how decisions are taken, and leads to authorities making better decisions and developing more effective solutions to issues as a broader range of expertise can be tapped into to solve public issues.[footnote 41]

The government will launch the Innovation in Democracy programme to pilot participatory democracy approaches, whereby people are empowered to deliberate and participate in the public decisions that affect their communities.[footnote 42] The government will work with local authorities to trial face-to-face deliberation (such as Citizens’ Juries) complemented by online civic tech tools to increase broad engagement and transparency.

Community assets

Since the 2011 Localism Act, communities have had a preferential right to bid for public buildings and other assets which have a clear community value when they come up for sale.

The government wishes to build on the Community Rights programme to enhance the capacity for community action and community building. This is an important agenda which is intended to endow neighbourhoods with the ownership and responsibility for managing the buildings and spaces that they use. It has the potential, in the words of an organisation participating in the engagement exercise, to “capitalise the community […] reshape public services and create the conditions for sustainable growth.”

The government will continue to encourage communities to use the community rights available to them. We will issue revised guidance to help communities take ownership of local assets. We will signpost support and advice available to communities to improve and shape where they live through the new Community Guide to Action and the MyCommunity website, the licence for which we have recently renewed.

As set out elsewhere (see ‘Mission 5: Investment’), the government is exploring means of ensuring community-led enterprises which take over public assets or services are able to secure the funding they need. It is recognised that these initiatives must acquire a genuine asset, not simply a liability, and that they often need non-repayable finance in the form of equity or grants to get going.

Many public libraries have an established track record in providing opportunities to facilitate this. Many are actively developing their role as community hubs bringing together local people, services, and organisations under one roof. There is a growing number of public libraries which are directly run or managed by the communities themselves or as mutuals by the people who work in them (or as a combination of the two), with varying levels of support from local councils at all levels.

The government will encourage further peer learning and support between mutual and community-managed libraries, and ongoing positive relationships and support between them and their local library authorities. Library services wishing to become mutuals can apply for support funding under the government’s Mutuals Support programme.

There are many communities without high-quality facilities and the capacity to manage them. The Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport, in conjunction with the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government, will design a programme to look at the barriers to and opportunities for more sustainable community hubs and spaces where they are most needed. The government will consult with key partners with a view to launching some pilot projects later in the year.

The Community Asset Fund is a Sport England investment programme dedicated to creating more opportunities for more people to be active, by enhancing places and spaces in local communities. The aim of the fund is to help community organisations to create good customer experiences and financially sustainable facilities that benefit the wider community in the long-term. To date the programme has invested £13 million in local communities across 429 projects with a further 200 projects in development.

The government aims to deliver an ambitious response to the Select Committee Inquiry into the future of public parks. The creation of the Parks Action Group which comprises experts from across the parks, leisure, and heritage sector and cross-Whitehall departments has fostered joint working between parks groups and volunteers and key government departments. The Parks Action Group is working collaboratively to identify how valuable shared community spaces can be protected and improved to provide important areas of social mixing, positive health outcomes, educational and training opportunities and encourage business investment.

The Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government is exploring the potential of transfers of public land to community-led housing initiatives, such as Community Land Trusts, by which residents become members of a trust which holds land and housing on behalf of the community.

Case study: a collaborative approach to commissioning and community participation

By the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government

Cornwall council undertook the process of passing powers down (double devolution) to communities and Town and Parish Councils, with the aim of sustaining locally-led services during a period of spending restraint. Cornwall developed a devolution framework which uses the Community Right to Bid and community ownership and management of assets. The framework sets out how Town and Parish Councils and Community Groups in Cornwall can work with Cornwall council at a level that suits them, from service monitoring and influencing contracts through to taking on and delivering local services and assets.

Partnership working is central to successful engagement and delivery and it was important that the council developed a culture of collaboration and partnering by:

- close working relationship with Cornwall Association of Local Councils representing over 80% of the 213 Parish and Town Councils in Cornwall and Cornwall Society of Local Council Clerks

- establishing a Service Level Agreement with Cornwall Association of Local Councils

- establishing a joint training partnership (including voluntary, community and social enterprise organisations, and Cornwall Association of Local Councils and Cornwall Society of Local Council Clerks)

- partner representation and presence in the Devolution Programme Management process and submitting evidence to Localism Policy Advisory Committee (latterly Neighbourhoods Overview & Scrutiny Committee)

- partner attendance at PROJECT meetings

- establishing thematic forums to help review and co-design processes – for example planning policies and agency agreements

- establishing 19 community network areas across Cornwall, local partnership forums comprising Cornwall Councillors, Town and Parish councils and local partners

As a result, many local councils and communities have secured the future of assets and services important to them by taking over their ownership or management as part of Cornwall council’s devolution programme. To date, in partnership with local councils and community organisations, Cornwall council has devolved or transferred local management of 75 public assets (pool, green spaces, play areas and historic buildings, libraries, and car parks), 223 public toilets, one placed based town package with 36 individual elements, each a project in its own right including play areas, green spaces, buildings, sports clubs, verges, town spaces, toilets and a car park, and three public libraries.

Cornwall Council has achieved success in the following:

- a £196 million budget savings

- reduced pressure on discretionary and mandatory community based services

- closer working with Town and Parish Councils/voluntary, community, and social enterprise organisations

- 160+ Agency Agreements with TPCs, 50+ Neighbourhood Plans being developed, 90+ Community assets listed, 30+ Community Emergency Plans in place / being developed

- devolving decisions on funding to support devolution, local partnership working and local highways schemes to Community Network Panels

Case study: Suffolk Libraries

The government recognises the role libraries play in supporting the transformation of individuals, communities, and society as a whole. They not only provide access to books and other literature, but also help people to help themselves and improve their own opportunities. They bring people together and provide practical support and guidance.

Suffolk Libraries is a public service mutual, an organisation which has left the public sector (also known as ‘spinning out’). It has a significant degree of staff influence or control in the way it is run, and continues to deliver public services. Suffolk Libraries was set up in August 2012 and is contracted by Suffolk County Council to run the library service for the benefit of the people of Suffolk. Since becoming a mutual it has maintained its statutory library service of 44 libraries, with the same or increased opening hours, as well as a mobile and home library service. Suffolk Libraries is community owned with a membership of 44 - a community group for each library which support their libraries and have a say in how they are run.

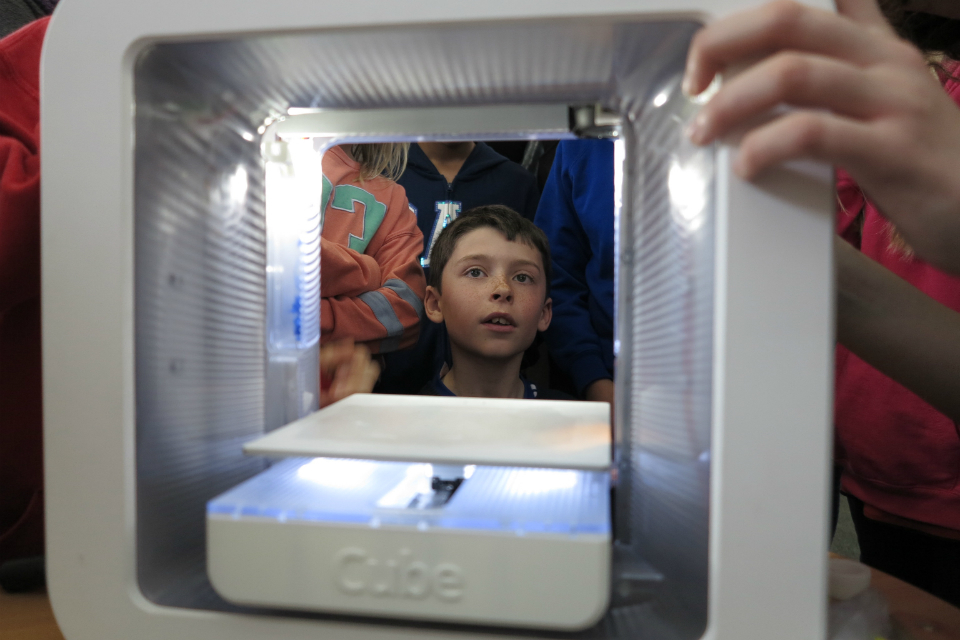

Six library services became Arts Council England National Portfolio Organisations in April 2018, including Suffolk Libraries which is receiving £704,000 in total from 2018 to 2022 to provide an innovative arts and culture programme to engage young people. This will fund a programme of activities across the library service to improve the service to 11 to 24 year olds and help build their skills and confidence in using digital technology and equipment. In the first year Suffolk Libraries is working closely with the arts organisation METAL, based in Southend-on-Sea, Liverpool and Peterborough, who have a strong track record for excellence with young people in the arts.

Photo credit: Suffolk Libraries

Mission 5: Investment

Strategic spending

The government has committed to creating a UK Shared Prosperity Fund once we have left the European Union and European Structural and Investment Funds. The UK Shared Prosperity Fund will tackle inequalities between communities by raising productivity, especially in those parts of our country whose economies are furthest behind.

The government intends to consult widely on the design of the UK Shared Prosperity Fund this year, as we committed to in the Industrial Strategy. There will be opportunities for civil society and communities to consider their role in supporting inclusive growth and driving productivity. Anecdotal evidence has emphasised that EU Structural and Investment Funds have been difficult to access. The design of the UK Shared Prosperity Fund provides us with an opportunity to simplify the administration and ensure that investments are targeted effectively to align with the challenges faced by places across the country.

Alongside the development of the UK Shared Prosperity Fund, the government is working with places to develop Local Industrial Strategies that will provide distinctive and long-term visions for how a place can maximise its contribution to UK productivity. Government has made strong progress with Greater Manchester, the West Midlands, and partners across the Cambridge-Milton Keynes-Oxford corridor on developing Local Industrial Strategies, and recently confirmed that all mayoral combined authorities and Local Enterprise Partnerships will have Local Industrial Strategies. These strategies, led by Local Enterprise Partnerships and Mayoral Combined Authorities where they exist, will align to the national Industrial Strategy and reflect local priorities.

As set out in the Industrial Strategy, Local Enterprise Partnerships will play an increasingly active role in delivering an economy that makes the most of the opportunities available across the country as we leave the European Union. As part of this, the government has committed to work with Local Enterprise Partnerships to bring forward reforms to leadership, governance, accountability, financial reporting, and geographical boundaries. In July 2018 government published a clear policy statement on Local Enterprise Partnerships’ roles and responsibilities.[footnote 43] This made clear that in line with the Industrial Strategy, all Local Enterprise Partnerships will have a single mission to deliver Local Industrial Strategies to promote productivity. Included in this statement is government’s recognition that successful Local Enterprise Partnerships work closely with the social sector and other key economic and community stakeholders. It is government’s expectation that Local Enterprise Partnerships continue this collaboration in order to draw on the best local knowledge and insight.

Local Enterprise Partnerships prioritise policies and actions on the basis of clear economic evidence and intelligence from businesses and local communities. Local Enterprise Partnerships are required to have the organisational capacity to fulfil their roles and responsibilities. They must have the means to prioritise policies and actions, and to commission providers in the public sector and private sector and voluntary and community sector to deliver programmes. Their interventions are designed to improve productivity across the local economy to benefit people and communities, with the aim of creating more inclusive economies. Successful Local Enterprise Partnerships work closely with universities, business representative organisations, further education colleges, the social sector, and other key economic and community stakeholders.

In line with the Industrial Strategy, all Local Enterprise Partnerships should continue to address the foundations of productivity and identify priorities across ideas, people, infrastructure, business environment, and places. We also recognise that in many areas their role goes beyond this to ensure the benefits of growth are realised by all, and that there are the right conditions for prosperous communities in an area. Dependent on local priorities, this could range from promoting inclusive growth by using existing national and local funding, such as in isolated rural or urban communities or working with relevant local authorities in the delivery of housing where it is a barrier to growth.

Government expects all Local Enterprise Partnerships will produce an annual business plan and end of year report which would also include details on how the Local Enterprise Partnership plans for consultation and engagement with public, private, and voluntary and community based bodies.

Government acknowledges that we need to do more to improve the diversity of Local Enterprise Partnership Chairs and board members, both in terms of protected characteristics and also in drawing from a more diverse representation of sectors, with representation from more entrepreneurial and growing start-ups and from the voluntary and community sector bodies who will often work with and deliver services on behalf of the most vulnerable in society.

New models of finance

The government believes there is a need for long-term, sustained relationships between communities and investors, with local funding that meets the specific investment requirements of the community, develops local resilience, and has the ability to attract private capital at scale.

This requires new models of investment and funding in communities, which bring together finance from a range of sources and have a clear mandate to raise social and economic outcomes.

There is particular need for new approaches in communities that have not benefited from the growth seen in some of our major cities and where there is often a lack of capacity and capability within these communities to access investment. This is exacerbated by siloed sources of finance from separate institutions with limited coordination, no specific mandate to focus on place, and limited ability to customise the finance to meet local needs.

Short-term funding is already available through the pilot fund and research grant Financing For Society: Crowdfunding Public Infrastructure. The project is supporting local councils to use crowdfunding for new, socially-beneficial public infrastructure projects (including an elderly care facility, community regeneration programme and green energy projects), and helping people to invest directly in their communities.

In addition, the government will continue work to consider additional measures it could take to unlock and boost social impact investment. For instance, the Secretary of State for Housing, Communities and Local Government is considering how we can increase the use of social impact investment to tackle homelessness, housing for vulnerable groups, and the regeneration of places at risk of falling behind.

The government will work with Big Society Capital and others to develop new models of community funding, which bring together social impact investment with philanthropic funding, crowdfunding, community shares and corporate investment to create substantial place-based investment programmes. This will be funded by money unlocked from dormant accounts, contributed by banks and administered by Reclaim Fund Ltd.

Big Society Capital and Access (The Foundation for Social Investment) will devote around £35 million of dormant accounts funding to initiating this effort. The funds will deliberately design in a high level of flexibility and the ability to respond to local needs, and will be co-designed with communities. Big Society Capital will work closely with other national and local funders and civil society organisations to ensure the work is fully joined up with other activities and to promote the principle of collaboration.

Supporting local sports, arts and culture

The government recognises the social and cultural roots of economic growth. Places need to be ‘liveable’ as well as ‘productive’. The government’s Industrial Strategy included among the ‘foundations of productivity’, (as well as ideas, infrastructure, and business environment) people and places. Research shows the value of attachment to place for boosting investment in a local economy, motivating people to find work in a particular place, and encouraging young people to remain in those places where they have strong social capital.

The argument which runs through this Strategy is that government action should focus on boosting, and bringing together, the resources of a community, so that life becomes better for everyone and social problems are prevented or reduced. This is an argument for public spending on civil society, and it applies as much to local government and to other independent commissioners of local services, such as Clinical Commissioning Groups or Police and Crime Commissioners, as it does to central government.

The government recognises that finance is critically pressing for civil society in many places. Sustained, long-term investment in the social fabric of places is vitally necessary.

Through the Cultural Development Fund, a commitment in the government’s Industrial Strategy, funding is provided to towns and cities across England to support them to develop and implement transformative culture-led economic growth and productivity strategies by investing in place-based cultural initiatives. The fund will support place-shaping by investing in culture, heritage, and the creative industries to make places attractive to live in, work, and visit.

12 Local Delivery Pilots which, between them, will receive up to £100 million of Sport England investment over the next four years, are a brand new approach to addressing the inactivity challenge. The Local Delivery Pilots will trial innovative ways of building healthier and more active communities across England. They will adopt a ‘whole systems’ approach, bringing together a broad range of organisations from different sectors including health, travel, and education to tackle inactivity and reach underrepresented groups.

Ministerial statement: communities and civil society

James Brokenshire MP

The Rt Hon James Brokenshire MP, Secretary of State for Housing, Communities and Local Government says:

Communities are socially and economically stronger, more confident and integrated where people have a real say over the decisions that matter most to them in their local area, including how local services are provided, facilities are used and how their neighbourhood is developing. Government will work with civil society to ensure that community voices are heard, valued and produce change so that no community is left behind.

Case study: Greater Grimsby Town Deal proposal

Located at the heart of the Humber ‘Energy Estuary’, Grimsby and North East Lincolnshire are building a new economic future. Over the next decade and beyond, there are strong prospects for growth in offshore wind and the continuing transition to a low carbon economy, and for export-led growth in port-related logistics and manufacturing, chemicals, petrochemicals and food processing.

Greater Grimsby’s fishing and maritime heritage remain central to the town as it diversifies and grows. The area has already come a long way in recent years, yet there is much more to do for Greater Grimsby to deliver its opportunities for growth and to ensure that it achieves truly inclusive and sustainable growth.

Despite this jobs growth, productivity in North East Lincolnshire is just over 72% of the England average (measured by gross value added per head) and there is an over-representation of low skilled/low value process operator jobs (particularly in the food sector). There are also low levels of business investment in innovation - though efforts to drive down offshore wind operations and maintenance costs, decarbonisation in our energy intensive industries and changes in business models post-Brexit, particularly in the food industry, present future opportunities. Too many young people leave school without having achieved their full potential. Low aspiration and academic underachievement are common.

In the Industrial Strategy white paper, the government announced its intention to a pilot Town Deal for Greater Grimsby. The Town Deal seeks to test a new, place-based approach to towns that have not fully benefited from economic growth, which will explore how the government, local councils, Local Enterprise Partnerships, businesses, and local people can work together to deliver social and economic growth in the area. It is an agreement with Greater Grimsby for a package of government support which garners departmental expertise and capacity. This mixed model of government and other investment support drives economic development and housing delivery in places. It has the potential for accelerated growth and enhanced contribution to the UK economy. The Town Deal affords a unique opportunity to demonstrate how places like Greater Grimsby can realise their potential.

Underpinning this is a strong commitment from the Greater Grimsby Partnership Board to work together to deliver inclusive growth and a place-based approach to the regeneration of the area.

The Town Deal will help shape and support housing and town centre regeneration, drive economic growth by helping to deliver 195 hectares of employment land across six Enterprise Zones, and raise aspirations and drive up educational and skills attainment. In doing so it will accelerate the delivery of jobs and new homes set out in the Council’s adopted Local Plan, which sets out ambitious targets for 8,800 jobs and over 9,700 new homes by 2032.

The Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport has been a key part of this process, helping shape the Town Deal, which has a strong ‘quality of place’ agenda. The Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport’s role in both driving economic growth and making the places people want to live and work in by bringing the civil society, arts, culture, and heritage sectors together - all the things that make life worth living - is crucial to the overall ambition for the town.

Phase 1 of the Town Deal, announced on 5 July includes plans for a £3.7 million Heritage Action Zone, partly funded by Historic England, which will see premises, docks and the town centre given a new lease of life for business and community use. Phase 2 presents a range of further opportunities for enhanced joint working - including developing new models of community action to support the Town Deal, identifying ways in which social impact investment can help fund projects, as well as plans to create community hubs, improving the offer for young people in the town and making the most of existing community assets such as libraries.

Case study: Greater Manchester Combined Authority - the role of place, community engagement and public sector reform

The devolution of previously Whitehall-based budgets and responsibilities to Greater Manchester have led the combined authority to think about place, people, and services in a new way.

Greater Manchester Combined Authority believe that local decision-making allows for better alignment across local organisations and budgets, the creation of integrated teams working across organisational boundaries and local engagement and decision-making that best reflects the specific circumstances of a particular area. More flexible, place-based, funding can deliver better value for money and improved outcomes for local people. Greater Manchester Combined Authority seeks to involve communities in all stages of strategy development. Key forums for this include an innovative Youth Combined Authority, a voluntary, community and social enterprise reference group, an older people’s network and a business advisory panel. Greater Manchester Combined Authority is clear that no organisation, sector or individual place within the city-region can work in isolation. Collaboration is fundamental to their approach and is helping them achieve their strategic ambitions. To achieve this vision, they try to ensure the voices of their communities are heard in all strategic planning.

Public service reform sits at the heart of the Greater Manchester Combined Authority’s approach, enabling the development of whole system approaches which are based on the following principles:

- integrated service delivery across the whole system in a place

- a focus on early intervention and prevention

- taking a holistic approach to the needs of the person in their context (including physical, mental, social, and environmental needs)

- taking an asset-based approach to people and place

- developing a new relationship with people and communities, helping people to help themselves

- developing new behaviours, skills, and roles in the public service workforce

Place-based integration has led the way and moved beyond strategic development and into implementation. At neighbourhood level, the focus is on integrated place-based services that are able to be responsive to local need and build on the assets of the community. This means one front-line team, knowing their area and each other. It must remain person-centred, starting with one person at a time, understanding their needs in the context of their family and their community, and building up a true picture of demand locally. Through this approach people are co-designing new solutions and services.

Voluntary, community and social enterprise organisations have been closely involved in the development and implementation of this new way of working. The sector’s local body, Greater Manchester Centre for Voluntary Organisations, signed a final document as co-owner of the shared strategy alongside Greater Manchester Combined Authority and the Local Enterprise Partnership. The Greater Manchester Strategy sets out the ambition to extend this into a new relationship with the voluntary, community, and social enterprise sector across a broad range of activities. This is supplemented by a new Accord with the sector setting out the principles of a new relationship and a specific investment fund based on long-term funding arrangements, which extend beyond annual contracting and cover core costs not just project finance.

Case study: West Midlands Combined Authority - towards an inclusive growth model

The West Midlands is undergoing a social and economic renaissance – powered by a vibrant jobs market, real energy in growth sectors such as advanced manufacturing and life sciences, and a model of collaboration that is encouraging investment in the region’s infrastructure, connectivity, and human capital. The region is large, complex, and diverse – with a population that is young (30% under 25), diverse (30% non-white), and which will challenge traditional ways of delivering services and enabling opportunities across the public, private, and social sectors.

Its ambition as a region is to support inclusive growth that all residents can appreciate – connecting ‘cranes to communities’ and using devolution as a lever for meaningful policy change. The West Midlands Combined Authority is at the centre of this ambition. It is itself a collaboration – between local authorities, public service, business, and social partners and a directly elected Mayor – helping the region to work and achieve more together.

This has translated into some good early progress in skills, housing, transport, and inward investment – with ambitions to embed a bold social and human capital strategy into its Local Industrial Strategy. A recently launched Inclusive Growth Unit will help make sure the agenda is as inclusive and citizen-focused as possible. The West Midlands Combined Authority is building on the energy already evident in the region – such as Coventry’s role as a ‘social enterprise city’, the Black Country’s maker movement, and Birmingham’s thriving social innovation sector.

Enabling civil society to thrive is at the heart of these ambitions. The local authority is working with partners to add value in the following areas:

- Industrial Strategy – with inclusive growth at its heart - which will focus on the West Midlands strategic advantages and high-growth sectors, but also on the cross-cutting enablers – digital, skills, and public services – that will be needed to sustain ambitious plans for industrial growth

- inclusive digital – the West Midlands digital economy is growing fast – with a 20% growth in digital Small and Medium Enterprises predicted by 2020 and a region-wide commitment to 5G that could radically lower the barriers to social and economic participation for marginalised citizens

- Social Economy Taskforce – convened by the West Midlands Combined Authority, the taskforce is exploring the ways in which the region could boost the role of social economy organisations within its growth strategy, and the specific ways in which devolution can unlock new models of financing and growth for what is already a thriving social economy sector in the region

- Inclusive Growth Unit – the West Midlands Combined Authority has established an embedded unit (a partnership with Barrow Cadbury Trust, Public Health England, Joseph Rowntree Foundation and others) whose job is to maximise the inclusivity of policy agendas, and ensure they are measuring and holding themselves to account against the right things

- social value – the West Midlands Combined Authority’s social value policy has been collaboratively developed and will be at the heart of major transport, skills, and housing procurement planned by the West Midlands Combined Authority and partners. West Midlands Combined Authority is working with colleagues from the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport to explore the application of social value principles into areas like loneliness, social isolation, and new models of health and care

- citizen and civil society engagement – as part of its work on inclusive growth the local authority is rebooting deliberative engagement with citizens and civil society organisations. Working with Localise West Midlands, the Royal Society of Arts and the Barrow Cadbury Trust, it is committed to making sure that citizen voice is at the centre of strategic plans and public service reform agenda

- region of sport and culture – the region is playing host to UK City of Culture, City of Sport and the Commonwealth Games over the next five years, creating a unique opportunity to build a legacy and bridge over its commitments to inclusivity with the aspiration and opportunity represented by these events

- faith engagement - building on the Mayor and Faith Conference in November 2017, the West Midlands Combined Authority has brought together a unique coalition of different faiths who are committed to exploring using their resources in different ways to combat some of the most pressing social issues in the region

- inclusive leadership - the West Midlands Combined Authority has worked for the past ten months on collating evidence on the leadership diversity deficit and will begin a period of internal review and engagement with external partners on effective recruitment, retention, and progression, making the business case for diverse leadership and creating better pathways for diverse talent

-

‘Historical review of place-based approaches’, Lankelly Chase, 2017 ↩

-

See ‘Historical review of place-based approaches’, Lankelly Chase, 2017 ↩

-

F. Polletta, ‘Participatory Democracy’s Moment’, Journal of International Affairs, 2014 ↩

-

‘Community Life Survey 2017-18’, Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport, 2018 ↩

-

‘One community: A guide to effective partnership working between principal and local councils’, Local Government Association and National Association of Local Councils, 2018 ↩

-

‘Community Life Survey’, Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport, 2018; ‘British Social Attitudes Survey 34’, NatCen Social Research, 2017; Suella Fernandes MP, Chuka Umunna MP, and Jon Yates in ‘A Sense of Belonging: building a more socially integrated society’, Fabian Society/BrightBlue, 2017; ‘Taking Back Control in the North’, IPPR North, 2017 ↩

-

Dr. W. Russell, ‘The macro-impacts of citizen deliberation processes’, newDemocracy Foundation, 2017; H. Pallett and J. Chilvers, ‘A decade of learning about public participation and climate change: institutionalising reflexivity’, in Environment and Planning A45 (5) 1162-1183, 2013; ‘Communities in the driving seat: a study of participatory budgeting in England’, Department for Communities and Local Government, 2011 ↩

-

‘Every Voice Matters: building a democracy that works for everyone’, Cabinet Office, 2017 ↩

-

‘Strengthened Local Enterprise Partnerships’, Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government, 2018 ↩