Addressing trust in public sector data use

Published 20 July 2020

Maximising the beneficial use of personal information held in the public sector

1. Key findings

- Data is needed not just to develop new technology but also to enable the evaluation of it. The UK will be unable to embrace the opportunities presented by AI unless data held by the government and wider public sector is shared.

- The sharing of personal data must be conducted in a way that is trustworthy, aligned with society’s values and people’s expectations. Public consent is crucial to the long term sustainability of data sharing activity.

- Addressing legal and technical barriers to data sharing has been the focus of much recent work. Data protection law provides a framework for data sharing. If consistently interpreted and applied, this may help to build and sustain trust. However, there has been relatively limited effort by the government and wider public sector to address public trust explicitly.

- A lot of personal data is shared across and outside the public sector. While this may be for beneficial purposes, public awareness of it is generally low. This gives rise to an environment of ‘tenuous trust’.

- Trust can be undermined by the inconsistent interpretation and application of legal mechanisms for data sharing, as well as the adoption of different security and technical standards. This creates a complex and confusing environment which also hinders transparency.

- There is also a communication challenge: framing the broader data sharing narrative to articulate how the public sector uses personal data is important. But this must also reflect what is publicly acceptable.

- CDEI will explore the subject of trust in further work with a particular focus on public awareness and acceptability. This can potentially be partially addressed by enabling citizens to have more control over certain data about them. However, trust may also be strengthened by identifying the clear conditions under which it is appropriate to share data in the public interest, without explicit user control or consent.

- Where data is shared in the public interest, there needs to be greater clarity about how the public interest is defined and judged. An individual’s right to privacy must be weighed against the rights of other citizens and of communities and society more widely.

- CDEI will work with partners to articulate the conditions for public interest data sharing. This will include a consideration of the appropriate system level governance structures and the potential role of an independent body to create an anonymised environment or integrated data infrastructure for access to public sector data. The data held could potentially be used to support areas of innovation that may bring significant public benefits.

- In its next phase of work, CDEI will collaborate with partners on use cases where there could be particular value to sharing more data in a way that is trustworthy.

2. Areas to explore for further work

CDEI is looking into how to begin to address the issues raised in this report. We plan to explore how we can:

-

Identify opportunities to give citizens greater access to the data the public sector holds about them, and to support the creation of digital products that operate on shared data. Examples could include: a. Creating personal digital records of qualifications for citizens that they can share with prospective employers or educational providers b. Sharing medical test result data with patients who would like immediate access and the ability to share with other providers c. Supporting the use of mechanisms that allow digital sharing of death records by next of kin to speed up the probate process

-

Convene relevant stakeholders including the Office for National Statistics (ONS), and the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO), as well as civil society organisations and the wider public, to establish clear principles for determining what constitutes public interest in the sharing and use of data by looking at specific areas including: a. Improving healthcare (e.g. allow research access to prescribing data to assess risks of opioid overprescribing) b. Improving public service delivery c. Preventing harm or discrimination in public service delivery (e.g. enable access to court records to enable an assessment of the consistency of court judgements)

This work should help to clarify the different public interest considerations when using data to develop and test AI applications, versus the deployment of AI systems in real world situations.

-

Work with the ONS, the ICO and others to establish clear guidelines on privacy protection standards to be applied when sharing data for public interest uses; this will include consideration of technical approaches such as differential privacy and homomorphic encryption, along with legal approaches such as audited standards applied to organisations with access to data.

-

Consider approaches to strengthen democratic accountability, including Parliament’s role in scrutinising the sharing and use of data in the public sector.

3. Executive summary

3.1 Rationale

Data sharing is fundamental to effective government and the running of public services. But it is not an end in itself. Data needs to be shared to drive improvements in service delivery and benefit citizens. For this to happen sustainably and effectively, public trust in the way data is shared and used is vital. Without such trust, the government and wider public sector risks losing society’s consent, setting back innovation as well as the smooth running of public services. Maximising the benefits of data driven technology therefore requires a solid foundation of societal approval.

AI and data driven technology offer extraordinary potential to improve decision making and service delivery in the public sector - from improved diagnostics to more efficient infrastructure and personalised public services. This makes effective use of data more important than it has ever been, and requires a step-change in the way data is shared and used. Yet sharing more data also poses risks and challenges to current governance arrangements.

The only way to build trust sustainably is to operate in a trustworthy way. Without adequate safeguards the collection and use of personal data risks changing power relationships between the citizen and the state. Insights derived by big data and the matching of different data sets can also undermine individual privacy or personal autonomy. Trade-offs are required which reflect democratic values, wider public acceptability and a shared vision of a data driven society. CDEI has a key role to play in exploring this challenge and setting out how it can be addressed. This report identifies barriers to data sharing, but focuses on building and sustaining the public trust which is vital if society is to maximise the benefits of data driven technology.

There are many areas where the sharing of anonymised and identifiable personal data by the public sector already improves services, prevents harm, and benefits the public. Over the last 20 years, different governments have adopted various measures to increase data sharing, including creating new legal sharing gateways. However, despite efforts to increase the amount of data sharing across the government, and significant successes in areas like open data, data sharing continues to be challenging and resource-intensive. This report identifies a range of technical, legal and cultural barriers that can inhibit data sharing.

3.2 Barriers to data sharing in the public sector

Technical barriers include limited adoption of common data standards and inconsistent security requirements across the public sector. Such inconsistency can prevent data sharing, or increase the cost and time for organisations to finalise data sharing agreements.

While there are often pre-existing legal gateways for data sharing, underpinned by data protection legislation, there is still a large amount of legal confusion on the part of public sector bodies wishing to share data which can cause them to start from scratch when determining legality and commit significant resources to legal advice. It is not unusual for the development of data sharing agreements to delay the projects for which the data is intended. While the legal scrutiny of data sharing arrangements is an important part of governance, improving the efficiency of these processes - without sacrificing their rigour - would allow data to be shared more quickly and at less expense.

Even when legal, the permissive nature of many legal gateways means significant cultural and organisational barriers to data sharing remain. Individual departments and agencies decide whether or not to share the data they hold and may be overly risk averse. Data sharing may not be prioritised by a department if it would require them to bear costs to deliver benefits that accrue elsewhere (i.e. to those gaining access to the data). Departments sharing data may need to invest significant resources to do so, as well as considering potential reputational or legal risks. This may hold up progress towards finding common agreement on data sharing. When there is an absence of incentives, even relatively small obstacles may mean data sharing is not deemed worthwhile by those who hold the data - despite the fact that other parts of the public sector might benefit significantly.

3.3 Public trust

It is also the case that the benefits of data sharing are not always felt equally among citizens. Indeed some people believe that the government prioritises using data to increase efficiency and fulfil its own objectives, rather than for the explicit and direct benefit to individual citizens. Barriers to data sharing are reinforced by a lack of public trust and an absence of a developed understanding of public acceptability. While the technical, legal, and cultural aspects need consideration, there is arguably a wider issue at stake. Whereas we have a well-developed understanding of the social contract between the citizen and the state in relation to taxation and public spending, the same is not true of data. Given that data is perhaps as important to the functioning of the state as money, and its significance is increasing, we argue it is time to consider a clear social contract between the citizen and state over how data is shared and used.

Establishing legality and adhering to security standards is fundamental to trustworthy data sharing - and are components of the existing data protection framework. But many of those involved in data sharing projects are conscious that the ethics are not straightforward and that public consent is far from certain. Survey evidence suggests a significant proportion of the population (between 40-60% of people) believes that the government’s use of data is not serving their interests.[footnote 1], [footnote 2]

Such uncertainty may mean that potentially valuable projects do not proceed, as the ‘rules of the game’ are unclear. In other cases, data is shared, but with little public awareness. This risks damaging trust further if such uses of data become widely publicised, particularly given evidence that there is deep-seated public distrust of governmental data-use.[footnote 3]

This report identifies an environment of tenuous trust in which data may be shared for valuable purposes, but the manner in which this is communicated to the public is primarily to limit a potential negative reaction, rather than active positive engagement. A lack of understanding and debate around what is publicly acceptable when it comes to data sharing and use may also create perverse incentives for departments to be less transparent about their work.

Such a challenge is not unique to the UK Government, and private organisations are having to consider how to maximise the value of data in a way that is trustworthy and practical. The UK has already demonstrated leadership in the area of data sharing, particularly with regard to open data and the publication of public data sets to support innovation.[footnote 4]

Nevertheless, the government and wider public sector will be unable to deliver the standard of services that citizens are entitled to expect if they lack societal consent to share data as effectively as is now required. The development and use of data driven technology to serve the public good is dependent on access to high quality data. CDEI supports a number of government initiatives already underway, including the Office for National Statistics (ONS) Secure Research Service and its accreditation regime, and the ICO’s Data Sharing Code. However, we believe that substantial additional investment is required. This could include a cost recovery model to address the financial disincentives of data sharing. Such a model would compensate those departments committing resources to sharing data for projects led elsewhere in the government.

While progress has been made on technical, legal, and cultural barriers, few of these measures (particularly outside of the health sector) are focused explicitly on addressing public trust. Inconsistent approaches to addressing barriers may also undermine trust by creating a complex environment with limited transparency, reflecting a lack of consensus around what constitutes safe public interest data sharing. There is a risk that this will stand in the way of future innovation.

3.4 Next steps

Efforts to address the issue of public trust directly will have only limited success if they rely on the well trodden path of developing high-level governance principles and extolling the benefits of successful initiatives. While principles and promotion of the societal benefits are necessary, a trusted and trustworthy approach needs to be built on stronger foundations. Indeed, even in terms of communication there is a wider challenge around reflecting public acceptability and highlighting the potential value of data sharing in specific contexts.

CDEI intends to focus on two areas outlined below.

Promoting citizen-driven data uses

Scepticism about whether data is used for citizens’ own benefit undermines public trust in data use and contributes to a feeling of powerlessness.[footnote 5]

Government data sharing is often used to inform decisions about citizens without their involvement.

To address this, we will explore areas where citizens can feasibly have more control over how their data is shared and used. Initiatives like Open Banking have attempted to enable citizens to take more control over their data, while also encouraging innovation within the sector. CDEI will endeavour to learn from this and consider contexts where data portability and data mobility in the public sector should be given higher priority.

An important consideration would be the likelihood that citizens make use of having greater control over data about them. As such, compelling use cases would need to be developed. There may also be scope for individuals to enrol with third party intermediaries who would be given permission to take particular decisions on their behalf about how data about them is shared and used.

Setting out the conditions for public interest data sharing

While explicit individual consent is often assumed to be the ideal basis for data sharing, there are a number of contexts in the public sector where this is not practical or desirable. This includes, for instance, when collecting administrative data from public services, or when actively identifying individuals eligible for particular support. Even when it is possible, individual consent in this context can often not be considered to be freely given because citizens may not have a meaningful choice if, for example, they need to access essential public services.

By working with public sector partners seeking to share data, and with civil society organisations and the public, CDEI will endeavour to articulate conditions under which data can, or should, be shared in the public interest while maintaining trust. In many cases it is not clear who assesses the balance of benefits and harms in respect of sharing particular data sets. This includes weighing an individual’s right to privacy against the rights of other people or communities, or society at large. In addition there are also cases when the boundary between using data to research policy issues and to intervene actively is unclear. For instance, a research project might identify characteristics that are likely to be shared by vulnerable people in a specific context, which may be uncontroversial. However, using this research to identify people as likely to be vulnerable and then intervene on their behalf raises different ethical issues.

CDEI will consider whether existing safeguards adequately ensure such data sharing can be considered trustworthy, and aim to develop a more consistent framework to address the current complex and uncertain environment. Such conditions would need to consider the protection of individual citizens from privacy invasion, protection of vulnerable groups, and measures of transparency and public engagement. A clear framework consistently applied would help to protect the dignity and privacy of individuals and build public trust, while also supporting the wider public interest.

We recognise that existing data protection legislation and the ICO’s forthcoming Data Sharing Code include processes such as Data Protection Impact Assessments, designed to support the identification of potential risks and harms. Indeed, it is unlikely that CDEI will recommend replacing existing mechanisms for data sharing. However, we are interested in exploring whether it is possible to define a public interest approach to data sharing with clear criteria regarding public benefit and protection of individual rights.

4. Glossary

Aggregation: Combining data about individuals to analyse trends while protecting individual privacy by using groups of individuals or whole populations rather than isolating one individual at a time.

Anonymisation: Aggregating or transforming personal data so it can no longer be related back to a given individual. Often this is incorrectly used for data which has only been de-identified.

Data-driven technology: Technologies which are dependent and based on the availability of data. It includes techniques such as machine learning, as well as other data analytics methods.

Data linking: Joining two datasets together through shared or inferred characteristics. Data linking can sometimes be used to re-identify a de-identified dataset.

Data minimisation: The idea that one should only collect and retain the personal data which is necessary.

Data mobility: How easily data can move from one service to another.

De-identification: Removing the identifying characteristics from a dataset (Name, Date of Birth, etc.). It may still be possible for the data to be re-identified and related back to an individual by linking it with other datasets.

Interoperability: The technical ability of services to work together as a single system, with data moving seamlessly between them. This goes beyond portability to look at access to key shared infrastructure, standardised data formats, and secure transfer mechanisms. Interoperability maximises data mobility, however it is often technically complex to achieve.

Personal data: Information that relates to an identified or identifiable living individual.[footnote 6]

Portability: The data mobility right, laid out in the GDPR, to access data about yourself in a way that could be used by another organisation. The transfer is usually done manually by downloading the data, but where technically feasible you have the right to ask the organisation to transfer it for you.

Pseudonymisation: Data which is pseudonymised has been de-identified while maintaining a unique ID to enable linking across data-sets and re-identification when necessary. (Note that the GDPR defines pseudonymisation to refer to all de-identified data, regardless of whether a unique ID is added).[footnote 7]

5. Introduction & Context

5.1 CDEI and Data Sharing

The purpose of CDEI, as set out in its Terms of Reference, is to identify how society can maximise the benefits from the safe and ethical use of data-driven technologies. Part of this task includes identifying and assessing effective and ethical frameworks for data sharing. This first paper on data sharing focuses on the flow of personal data held in the public sector.

Personal data held by the public sector presents significant potential value to individuals and society. The sharing of it is essential for the delivery of services and policy development across the public sector. Citizens rightly expect to be able to benefit from the availability of their information within public services to improve efficiency and coordination - for example when moving between NHS providers. Yet survey evidence also suggests that the public has low levels of trust in the government’s ability to use data in ways that will help them.

Data sharing is central both to innovation and to the ethics of data driven technology. Access to data is necessary for the development of new data driven technology as well as assessing the impact of these systems and holding those who are responsible for them to account. Part of CDEI’s role includes identifying how data can be shared in ways that allow innovation while increasing accountability and ensuring there are adequate safeguards.

Public sector organisations hold many of the most sensitive types of data, which have usually been collected for a particular purpose. While sharing it and combining it with other data sets may be of value, it is important to understand the potential trade-offs with individual privacy and autonomy as well as what the public might consider acceptable. The sharing of such data therefore presents particular challenges. By exploring these challenges, CDEI will develop advice designed to help those working with data to address them. Our aim is to promote more trustworthy sharing that supports innovation while also ensuring that data held in the public sector can benefit individuals.

This report explores recent efforts to increase data sharing across the government and wider public sector, maps the current technical and legal environment for data sharing, and focuses on a series of case studies to understand how common barriers to data sharing can be overcome. It then focuses on the reasons for notably low public trust in public sector use of data and sets out how a more trustworthy data sharing environment may be established. The paper concludes by setting out two areas for further work to address the issue of trust.

5.2 Personal Data in the Public Sector

The public sector is a federated group of government departments and organisations that struggle to work together as efficiently as expected by citizens. Personal data is split between a large number of databases, controlled by different authorities, with different access and sharing policies. Departments tend to only hold the limited data they need to deliver particular services and rarely build systems that can be accessed by other departments.

This data is valuable, not just in an economic sense, but also because it can unlock novel capabilities for public services. There are good reasons to avoid a single vault holding the data on all citizens. The friction this produces legitimately limits the power of the state over its citizens, helps account for the very different contexts in which data is collected, and minimises the impact of data breaches. However there are areas across the public sector where sharing useful data could enable bodies to deliver better services or design new policies.

A complex and inconsistent system for sharing can adversely affect the quality of service received by citizens. Individuals must often navigate various bureaucracies to access their information from one public sector body and provide it to another. This process may be frustrating to citizens, creates additional opportunity for error, and also means they are expected to share sensitive information in relatively insecure formats (e.g. by post).[footnote 8]

Case Study - Blue Badge Parking Permit

Blue Badges are distributed by local councils and allow people with mobility issues access to disabled parking spaces closer to their destination. The clearest way to get a badge is to provide the local council with evidence of disability benefits based on impaired mobility from the DWP. If this is not possible, the applicant must provide written evidence explaining their requirements, including any health treatments they are on, medications they take, or doctors that have assessed their condition. This application is a lengthy process and councils can take 12 weeks or longer to come to a decision. It also makes the disabled individual responsible for coordinating between their local council, the DWP and their doctor, to get the accommodations they need, and may be too burdensome for many people who could benefit from this scheme. The development of an attribute exchange which would enable the verification of eligibility without sharing personal data could make the application process more efficient. This has been piloted by some local authorities.[footnote 9]

An inconsistent and complex data infrastructure also makes it difficult to hold the government to account, both for policy programmes, and for the use of data. The keeping of data in silos may, for example, mean that opportunities to understand how particular policies affect people and groups are missed.[footnote 10]

Data is shared for a number of reasons, and each project has its own benefits and risks. It is also likely that the public view of what is acceptable and trustworthy may differ depending on the use case. The reasons for data sharing are fluid and linked. Academic research using data may, for example, point to new innovations, but then also be used to support service delivery.

The most common reasons for data sharing in the public sector include:

Provision of public services to individuals

To improve the effectiveness and efficiency of delivering services to the public, it is often necessary for different parts of the public sector to share information about an individual’s circumstances. This includes information that is essential to provide a service (e.g. sharing medical records between different NHS providers), and determining the eligibility for particular benefits (such as the Warm Home Discount).[footnote 11]

Law enforcement and community protection

In some cases, personal data about an individual is shared between public sector organisations to police the behaviour of that individual. For example, it may be possible to find information that indicates tax evasion or benefit fraud, or identify people who are using government services but do not have the right to remain in the country. Data is also shared when it is relevant to a criminal prosecution. Social services are expected to share information that relates to risks to children, and health services are required to share information in relation to communicable diseases.

Planning, managing and regulating public services and national infrastructure

Public services are delivered by a mixed economy of different public and private sector organisations. For such organisations, like Clinical Commissioning Groups in the NHS, or local authorities, which have responsibility for budgeting, commissioning or overseeing the delivery of services, access to information about the population served is an important resource.

The same is true of regulated national infrastructure such as the energy grid and the transport network, where effective regulation, oversight and planning require flows of data between different entities, including companies providing services, and public sector organisations with responsibility for the safe and effective provision of such services.

Use case (managing public services): The sharing of prescription data across the NHS

Data contained in patients’ prescriptions is shared across the NHS and also used in aggregated form to produce statistical reports. Organisations receiving prescription data include GP practices, pharmacies and NHS prescription payment and fraud agencies. Pharmacists review prescriptions issued by GPs to dispense the correct medication. Pharmacies share the prescriptions with NHS Prescription Services[footnote 12], part of the NHS Business Services Authority (BSA) via the prescribing and dispensing information systems. NHS Prescription Services uses the data in individual prescriptions to calculate the remuneration and reimbursement due to dispensing contractors across England. BSA also aggregates the data to help different parts of the NHS track trends and take informed decisions. This includes providing data for:

- performance management

- financial planning

- following clinical best practice

- complying with regulations

- identifying outlier behaviour

- publishing national statistics

Developing new policies

Sharing personal data can enable more innovation to help drive simpler and more efficient public services by finding new ways to address different policy goals, for instance exploring the relationship between school records and later criminal convictions in order to work out where early intervention could have the most impact. While such analysis would typically be conducted on anonymised data sets, identifiable data often needs to be shared so that the data can be accurately matched.

Monitoring

Traditional research tends to be dependent on reviewed data sets which are shared with researchers through a defined request and approvals process. However, access to real time data, or regular data feeds, can be more challenging with routes to accessing such data being less defined. In part, this may be because of technological barriers, but governance mechanisms are also challenging as data cannot be reviewed and approved before being released. This is important as it affects the ability of third parties to evaluate the effectiveness of particular initiatives without relying on historic data.

Evaluating existing policies

Analysis of data about populations is essential to understand whether or not government policy is working. In many cases the relevant information will not be held by the organisation responsible for a policy. For example, to analyse whether training or rehabilitation policies are resulting in people gaining employment, data will need to be collected from different agencies as well as potentially from private sector providers contracted to deliver a service.

Sharing data enables departments to understand the long-term effects of their policies across a number of factors in an individual’s life and build a full picture of the benefits and costs. Even when the final analysis can be done using de-identified data, linking data across departments often requires the sharing of original identifiable data. It also allows other bodies to assess the effectiveness and fairness of existing initiatives, and hold departments to account for their work.

Research

Independent researchers (e.g. academics and policy institutes) may submit research proposals to access data to inform their work, either on public policy or other social science research. Research projects may rely upon single datasets but in many instances different datasets are linked and de-identified.

Research and the Digital Economy Act

Part 5 of the Digital Economy Act included new legal powers to provide the UK Statistics Authority (and ONS as its executive office) with better access to data to support the production of official and national statistics, and statistical research; and to provide accredited researchers with better access to de-identified public sector data to support research projects for the public good.

The Act facilitates the linking and sharing of de-identified data by public authorities for accredited research purposes (except for health and social care bodies). The UK Statistics Authority is the statutory accrediting body responsible for the accreditation of processors (those who de-identify the data and provide secure access to the de-identified data), researchers and their projects.

Before data can be shared for research purposes, it must be processed by an accredited processor so that the data is ‘de-identified’. When the data has been de-identified it can be made available to an accredited researcher in a secure environment for research in the public good, and the processor will ensure that any data (or any analysis based on the data) retained by the researcher, or that are published, are ‘disclosure controlled’ to minimise the risk of data subjects being re-identified or other misuses of the data.

As the statutory accrediting body, the UK Statistics Authority has established a Research Accreditation Panel to oversee the independent accreditation of processors, researchers and research projects.

To date, there are approximately 3000 accredited researchers, with accredited processing environments across the country, including the ONS SRS in London, Newport and Titchfield and the NISRA Research Support Unit in Belfast.

5.3 Common barriers to data sharing

Over the past 20 years, governments have set out a series of policy initiatives to increase data sharing. In the context of an increasingly data driven world, the impact of these policies is insufficient.

The focus of recent reports on this issue has often been on the barriers government faces when it tries to share data, leading to missed opportunities. The think tank Reform, the National Audit Office, and the Public Accounts Committee have all identified similar categories of barriers which continue to stifle effective use of data.[footnote 13]

The clearest obstacle to data sharing is the set of complex technical constraints limiting the ability of departments to coordinate. Many elements of the public sector rely on their own legacy IT systems and poor quality data which also make it difficult to conform to common standards. In addition, public sector organisations set their own security requirements for data sharing and use different approaches to enabling access to third parties.

Perceived legal challenges are often highlighted as barriers to data sharing. There have been many initiatives to create specific legal gateways for sharing data which sit on top of data protection legislation (see below). The result is a complex and confusing environment. Uncertainty about the legal bases for data sharing and the absence of common terms and conditions mean that bodies attempting to share data tend to start from scratch when determining legality. Different data sets are also governed by different legislation and such an absence of consistency can create further confusion.

The need to identify the appropriate legal gateway and follow particular processes and approaches may introduce legitimate friction in the system which acts as a safeguard against misuse of data. However, in many cases delays may also occur as a result of a lack of clear business processes or the need to secure the resources needed to procure legal expertise.

Existing data protection law may provide a framework to enable trustworthy data sharing. However, there are concerns that misunderstandings relating to GDPR and what it permits may have created further aversion to data sharing. The Information Commissioner’s Office’s updated Data Sharing Code of Practice (the draft Code was published in 2019) will seek to address this.[footnote 14]

Related to this are issues of terminology. GDPR and the Data Protection Act 2018 use clearly defined terms, particularly with regard to anonymous information and pseudonymisation. However such terms are not well understood by citizens, and other public bodies continue to use different terms which lead to further inconsistencies.[footnote 15]

While the ICO’s Data Sharing Code will help, there likely remains a considerable communications challenge.

The identified barriers to data sharing can be exacerbated by the prevalence of a siloed and risk averse culture in the public sector. In some cases data sharing may raise potential reputational risks or other threats causing a conflict of interest. In other instances, a lack of certainty about the legality, security and ethics of data sharing may result in the outright rejection of data sharing requests or significant delay in establishing the terms of data sharing. Departments are generally focused on the services they provide directly and there is little incentive to share data in support of a wider government agenda or benefit citizens in other areas. Such a culture may have emerged to protect citizens’ privacy and reduce the risks of data misuse. However, this may cause potential benefits and opportunities to be missed, or not adequately evaluated.

Some departments expressed concern about the safety of their data if they share it with others, especially if they cannot confirm the security arrangements in other organisations. While understandable and right, this can discourage opportunities to use data to its full potential.

Source: Challenges in using data across government, National Audit Office (2019)[footnote 16]

In addition to the barriers detailed above there is a lack of incentives to encourage public sector organisations to share data for ethical and valuable purposes. While sharing data may bring benefits to citizens and different parts of government, it does not follow that it is viewed by those holding the data as worthwhile. Even relatively small obstacles may stop data sharing from happening with the costs viewed as outweighing any potential benefits. Relevant legislation e.g. Digital Economy Act, is largely permissive, meaning organisations can refuse to share data without a risk of penalties.

These barriers require time and money to overcome, and the lack of central leadership exacerbates this problem - in 2019 the National Audit Office concluded that data is generally not treated as a strategic asset by government departments, and data projects are rarely prioritised in funding decisions.[footnote 17]

This is in part because the existing costs of poor data are hidden and the benefits only appear in the long-term. Furthermore, departments will often collect data with a particular purpose in mind with little consideration given to the value of potential secondary uses. This can increase costs as additional work needs to be undertaken to make the data suitable for sharing.

Although these barriers are important, our analysis of data sharing projects highlights the more fundamental issue of the public’s lack of trust in government use of data. It is likely that public trust varies depending on the type and context of the data use - and may be higher, for example, in relation to aggregated data used for statistical purposes, than identifiable data being shared. However understanding what is deemed trustworthy and what is publicly acceptable is not straightforward.

Surveys suggest that the public assume much more data is shared than takes place in reality. Yet a lot of data-sharing that is happening takes place without the knowledge of the citizens whose information is being used. There is a long history of data sharing projects becoming public and triggering a backlash. Organisations agreeing to share data risk coming under pressure from the media and civil society organisations. This may cause government departments to limit their external communication to prevent further weakening trust. We explore public trust in chapter 5.

6. A brief history of government data sharing initiatives

To understand how these barriers have developed and the steps taken to try to overcome them, it is useful to look at the history of this policy debate. The drive for more data sharing, alongside concerns about privacy, has a long history. The timeline below sets out some of the key milestones and highlights an absence of an explicit focus on public trust.

Timeline Diagram

Modernising Government White Paper (1999)

- This paper on public sector reform saw effective data sharing as part of creating a digital government

- It pointed out some technical, legal and cultural barriers to overcome, while highlighted the need for privacy and transparency

Privacy and Data Sharing (2002)

- This was a full report on data sharing as part of the Modernising Government agenda

- It proposed new data sharing legislation to simplify the legal environment

- It also proposed a new Public Services Trust Charter for trustworthy public bodies, with accompanying kitemark

Department for Constitutional Affairs (2003-4)

- The DCA explored the need for the proposed legislation, but found it unnecessary

- Instead, they developed a code of practice and provided legal guidance

Transformational Government (2005)

- An agenda owned by HM Treasury to pursue shared IT services across government

- It set up a Data Sharing Ministerial Committee which controversially claimed “information will normally be shared…provided it is in the public interest”

Data Sharing Review (2008)

- An independent review called in the light of controversial centralised IT projects such as the National Identity Register

- Similar to the DCA analysis, it found no legal barriers but much legal confusion, cultural barriers, and a lack of trust

- It called for a statutory Data Sharing Code of Practice from the ICO, and more Privacy Impact assessments

- It also called for a fast-track data sharing power, allowing Secretaries of State to amend any legislation or add a power using secondary legislation to enable data sharing

- It pointed to the need for ‘safe havens’ for academic research, although the government highlighted that systems such as the ONS Secure Data Service were already in place

Coroner’s and Justice Act (2009)

- The recommendations from the Data Sharing Review were originally included in this act, however the broad fast-track power received a lot of opposition due to lack of safeguards

- The only measure which was enacted was the requirement for a Data Sharing Code of Practice from the ICO, introduced in 2011

Government Digital Service (2010)

- The new centralised IT service sought to overcome technical barriers to data sharing by setting data standards for procurement

- Rather than centralised databases on citizens, there is a move towards alternative distributed solutions for linking data such as the Verify initiative

Data Sharing Code of Practice (2011)

- Published by the ICO

Open Data White Paper (2012)

- This paper moved the focus of data policy from creating joined-up government to enabling innovation from publicly held datasets

- The goal was to increase citizen choice, drive innovation, and enable external research

Improving Access for Research and Policy (2012)

- A report by the Administrative Data Taskforce looking at opening government administrative data for external researchers

- Proposed more use of safe havens and a new gateway allowing data to be linked for research

Law Commission report (2014)

- An investigation into whether the legal framework was inhibiting data sharing by public bodies

- Found no major legislative obstacles, but a lot of confusion based on the complex statutory gateways that impeded transparency and led to differing interpretations.

- Called for reform with fewer gateways based on principles, rather than projects.

Data Sharing discussion (2014)

- An “open policy making” process where potential new data sharing legislation was published and discussed with civil society groups

- The new legislation focused on research, tailored public services, and managing fraud, error and debt

- The engagement had led to a number of new safeguards on making sure the sharing would be beneficial and not punitive to the individual

Better Use of Data (2016)

- A public consultation on the final proposal from this policy-making process

- The consultation pointed to the need for more transparency, accountability, and accessibility to individuals

Digital Economy Act (2017)

- The powers within Part 5 of the Digital Economy Act are designed to help overcome legislative barriers to data sharing.

Data Protection Act (2018)

- The Data Protection Act 2018 (DPA 2018) sits alongside the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and sets out the framework for data protection in the UK.

- The ICO is obliged by the Data Protection Act 2018 to produce the data sharing code.

- The ICO is expected to publish a new Data Sharing Code of Practice in 2020.

National Data Strategy (2020)

- Development of the Strategy is underway and led by DCMS to improve access, efficiency and trust in private and public data use.

7. The data sharing environment

This chapter sets out the current context for the sharing of data held in the public sector and considers the existing legal, technical and cultural factors. These are also linked to developing a trustworthy environment for data sharing.

7.1 Promoting safe and ethical data sharing

There have been efforts to promote consistent approaches to data sharing that also aim to support data controllers to work in ways that are safe and ethical.

Five Safes

A number of past reports into data sharing have called for ‘data safe havens’ to be set up to provide security when analysing data.[footnote 18]

Administrative Data Taskforce, Improving Access for Research and Policy (2012)

The gold standard in this regard is the Office for National Statistics (ONS) and their Secure Research Service. The ONS has promoted and led the way by implementing the Five Safes principles:

- Safe people: researchers must be experienced, accredited and they must sign a confidentiality contract

- Safe projects: every project must be in the public benefit, must be approved, and the results publicly available

- Safe settings: data is only accessible in secure environments

- Safe data: the data is de-identified as much as possible

- Safe outputs: the outputs of analysis must not identify any individuals

The principle of ‘safe settings’ is one of the most important principles due to the ease of copying and transferring sensitive data for another purpose, but it is also the hardest to enforce. Many data controllers therefore establish their own facilities for researchers to use, where they are required to access the data through managed equipment and their activity is closely monitored. There are also secure environments at HMRC, and in Scotland which includes data from NHS Scotland.

Over time, the Five Safes is set to provide increased consistency for researchers accessing sensitive government data.

Protecting Individuals’ Identities

Anonymisation is an important principle often invoked in justifying data sharing, particularly when looking to share data for research or evaluation purposes with academic or private sector organisations. However anonymisation cannot be achieved simply by removing identifiers (de-identified data) since any data that includes information about individuals raises a possibility of ‘jigsaw’ re-identification, in which different sets of information are cross-checked allowing information about an individual to be discovered (often termed the ‘mosaic effect’).

Relying solely on de-identifying data may provide individuals with a false sense of security when reality falls short of their expectations of privacy. Techniques to protect people’s identity rely on a combination of information reduction (de-identification and obfuscation), secure controls over access to data, and legal and contractual obligations on organisations accessing data.

Attribute exchange

There are a number of data sharing use-cases where it would be simpler and more secure to share a response to a query rather than the full individual data. GOV.UK Verify is an example of this mechanism, as identity verification is done by a third party with access to multiple sources of identity data, and only the result is passed on to the organisation which requires the verification - minimising the exchange of sensitive data.

Privacy Enhancing Technologies (PETs)

There are also a number of more sophisticated emerging technologies which can better protect the privacy and security of different data sharing approaches. These limit access to individual data, either by transforming it, encrypting it, or storing it on a different system, while still enabling analysis.

Differentially private algorithms are one example, designed so that calculated statistics do not give more information about a particular individual than if that individual had not been included in the dataset. Federated learning is another mechanism, which allows a central authority to create machine learning models without collecting individual’s data in a central location. A third technology is homomorphic encryption, which allows computations to be performed on encrypted data. Finally, trusted execution environments allow code and data to be isolated from the rest of the software that is running on a system, in order to ensure their confidentiality.

Such technologies to protect individual data have many potential benefits, although the large number of alternatives could easily cause confusion about the right approach and make collaboration more difficult. The Royal Society has called for the Government to both fund the development of PETs, and become an early adopter in order to provide support and expertise to wider society.[footnote 19]

However, all these techniques for maximising individual privacy and data security only go so far. There are further questions about privacy in general that need to be asked, especially about what uses of data are acceptable and how decisions to share data are made.

Development of Ethical Frameworks

In June 2018 the UK Government published a Data Ethics framework setting out the principles for ethical use of data by public services. Principle number 6 is to “Make your work transparent and accountable”. This principle stresses the value of sharing algorithms and data in order to allow work to be understood, reviewed and challenged. There is little evidence that the framework is yet having a significant practical impact although it is set to be refreshed and promoted by DCMS.

UK Statistics Authority: Data Ethics Committee

The National Statistician’s Data Ethics Advisory Committee (NSDEC) was established to advise the National Statistician whether the access, use and sharing of public data, for research and statistical purposes, is ethical and for the public good. It provides a good example of the way in which ethical principles can be practically applied to decisions regarding the sharing and use of data.

NSDEC considers projects and policy proposals, which make use of innovative and novel data, from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) and the Government Statistical Service (GSS) and advise the National Statistician on the ethical appropriateness of these. The Committee must include at least five independent external members. To make decisions the committee assess proposals against the NSDEC’s ethical principles:[footnote 20]

- The use of data has clear benefits for users and serves the public good.

- The data subject’s identity (whether person or organisation) is protected, information is kept confidential and secure, and the issue of consent is considered appropriately.

- The risks and limits of new technologies are considered and there is sufficient human oversight so that methods employed are consistent with recognised standards of integrity and quality.

- Data used and methods employed are consistent with legal requirements such as Data Protection Legislation, the Human Rights Act 1998, the Statistics and Registration Service Act 2007 and the common law duty of confidence.

- The views of the public are considered in light of the data used and the perceived benefits of the research.

- The access, use and sharing of data is transparent, and is communicated clearly and accessible to the public.

National Data Guardian for Health and Social Care

The NHS is home to one of the richest data sources in the UK. The insights derived from it have the potential to drive innovation and improve health care, for instance through precision medicine, genomics, or medical imaging.[footnote 21]

However health data is highly identifiable and generally viewed as being intensely personal, creating unique ethical concerns. For this reason, the NHS has been at the centre of the public sector data use debate for decades; the first review of Patient-Identifiable Information was led by Dame Fiona Caldicott in 1997.

Trust in the NHS using data appears to be high relative to other parts of the public sector.[footnote 22]

Nevertheless, there have been a number of high profile cases which have highlighted the different tensions at play. This includes projects such as our case study of the Royal Free and DeepMind, as well as wider sector initiatives such as care.data, which became a focus of media attention and triggered a public backlash. These issues are perhaps exacerbated by the organisational complexity of the NHS.

There are ongoing efforts by the NHS and the Department of Health and Social Care to address trust while also seeking to support socially valuable innovation. Most noticeably, in 2014 Dame Fiona was appointed in an official advisory role as the National Data Guardian for Health and Social Care (NDG) and the role was placed on a statutory footing on 1 April 2019. A core component of the role is trust, “with a focus on what can be done to help people be aware of, and more actively engaged in, decisions about how patient data is used and protected.”[footnote 23]

Based on a recent public consultation on her work, the following priorities were chosen:

- Supporting public understanding and knowledge, by championing meaningful transparency and public engagement

- Encouraging information sharing for individual care

- Safeguarding a confidential health and care system, by clarifying reasonable expectations and what use-cases should not go ahead

The NDG led an independent review of data security, consent and opt-outs from 2015 to 2016 which led to the implementation of greater transparency in NHS data sharing and more role for patient consent and opt-outs for secondary uses of data.[footnote 24]

Inconsistent Approaches

Different approaches to governance may undermine public trust. A fragmented landscape is not only frustrating for researchers who must navigate different governance regimes, but may also lead to inconsistent governance decisions being taken. Greater use of the Research strand of the Digital Economy Act by departments, which has been approved by Parliament and was developed through an open policy making process, may help to address this.

As outlined above, ONS has introduced strong governance processes, including accreditation frameworks which address ethical considerations, as well as security. However, when it comes to the sharing of real time data, regular data feeds (for monitoring purposes) or even data that might have a greater direct impact on citizens, there is an absence of common approaches.

7.2 Legal measures

Confusion about what is legally permissible has hampered data sharing proposals, and there have been a number of attempts, most recently the Digital Economy Act, to address this. An added complication is that legal permissions governing particular data sets (in addition to data protection legislation) tend to relate to specific departments rather than the public sector as a whole. The holding of different data by different departments and agencies can seem rather arbitrary and adds further complexity. Establishing the legality of data sharing is a key element of trustworthy data sharing, but an inconsistent and confusing environment may also undermine trust.

Data Protection Act 2018 (DPA)

Data protection has been the applicable law governing data sharing since the Data Protection Act 1998. The introduction of the EU’s GDPR together with the DPA 2018 strengthened many of these protections.

One of the GDPR requirements is that public authorities must have a valid lawful basis for processing or sharing personal data. Public authorities are generally able to use the ‘public task’ basis instead of requiring explicit consent, which allows for either carrying out a specific task in the public interest laid down by law or exercising official authority which is also laid down by law.[footnote 25]

Departments headed by a Minister of the Crown have common law powers to share information which covers this requirement. Other public bodies can also share information to fulfil a power given to them by legislation. Data sharing may also be necessary in order to comply with a legal obligation.

Although individual consent is not legally required, data sharing is expected to be transparent to data subjects so they know what is happening to their data, and that the data shared is proportionate to a limited purpose. While re-use for research and statistical purposes may be compatible with this purpose, other public interest uses may not be. If there is a high risk to the individual, a Data Protection Impact Assessment is required. Despite this, there is still a misconception that consent is legally necessary for sharing data which leads to risk aversion.[footnote 26]

Consent and public sector data use

GDPR: Consent

Consent means offering individuals real choice and control. Genuine consent should put individuals in charge, build trust and engagement, and enhance your reputation.

Source: ICO’s Guide to Data Protection[footnote 27]

Public sector organisations rarely use consent as the basis for processing data. In most cases this would be inappropriate since the processing of data is a precondition of the provision of a service and there is therefore an imbalance in power between government and the citizen. In these circumstances consent would not be regarded as freely given. Instead, the performance of a public task is the lawful basis for processing data. This may also allow for processing by a third party data processor, often a private sector organisation, acting on behalf of the public sector organisation.

GDPR: Public Task[footnote 28]

- You can rely on this lawful basis if you need to process personal data: ‘in the exercise of official authority’. This covers public functions and powers that are set out in law; or to perform a specific task in the public interest that is set out in law.

- It is most relevant to public authorities, but it can apply to any organisation that exercises official authority or carries out tasks in the public interest.

- You do not need a specific statutory power to process personal data, but your underlying task, function or power must have a clear basis in law.

- The processing must be necessary. If you could reasonably perform your tasks or exercise your powers in a less intrusive way, this lawful basis does not apply.

- Section 8 of the Data Protection Act 2018 (DPA 2018) says that the public task basis will cover processing necessary for: the administration of justice; parliamentary functions; statutory functions; governmental functions; or activities that support or promote democratic engagement

Commissioners for Revenue and Customs Act 2005

HMRC has specific legislative restrictions on data sharing to protect confidentiality which often prevents them from sharing data. The founding legislation of HMRC, the Commissioners for Revenue and Customs Act 2005, restricts data sharing to its specific functions, when a new legal gateway exists, or when it is in the public interest (as defined in section 20 of the act). Because of the itemisation of these specific cases, HMRC has more limited disclosure powers than most other public bodies, especially compared to minister-led government departments.

Statutory gateways

While common law powers are often sufficient, many other data sharing legal gateways have been created in order to provide legal certainty where bodies have been concerned about ambiguity. This has led to a very complex data-sharing legal environment. The Law Commission report in 2014 found “the law has developed without consistent oversight and scrutiny, resulting in a complex web of statutory provisions.”[footnote 29]

While most of these gateways are permissive, some require data sharing in specific circumstances. For example, the Children Act 1989 requires Local Authorities to provide the Education Secretary with any requested information on students or children in care, and any other information necessary to monitor the performance of schools or care homes.

Digital Economy Act 2017

The Digital Economy Act 2017 (DEA) sought to provide clarity and limit the need for any new legal gateways to share data, as well as taking into account the HMRC confidentiality rules.

A data sharing project relying on the DEA must be pursuing one of four possible purposes:

- The improvement, targeting, or monitoring of a public service by specific public bodies, as long as it has an approved objective aimed at improving the wellbeing of an individual or household

- The sharing of civil registration data (births, marriages and deaths) to enable other public services

- For trial projects to identify or act on fraud, error or debt in public finances

- Projects and researchers approved by the Statistics Board for research that is in the public interest

Each of the DEA powers requires a code of practice to be issued that is consistent with the Information Commissioner’s data sharing code of practice. The specific objectives must be agreed through secondary legislation, and any project relying on these must have a publicly accessible data sharing agreement which is included in a public register.

For the public service task, the initially agreed objectives were to identify households struggling with multiple disadvantages, and to address fuel and water poverty.

Use Case: The Troubled Families Programme and the Digital Economy Act

A local authority could look to access data held by a range of partners (including the local police force, schools, and others) to identify whether there are individuals or households who meet the criteria for support under the Troubled Families Programme. The proposed information share would need to be consistent with the multiple disadvantages objective of the public service delivery power created by the Digital Economy Act 2017, and the bodies that the local authority wishes to share data with would need to be present on Schedule 4 in the Act as specified persons able to disclose data under this gateway. This means that the local authority has a lawful power to share data. As the power is permissive, the local authority will still need to agree with the other bodies to share information for this purpose and draw up an appropriate data sharing agreement and ensure that it is compliant with the Data Protection Legislation. The consent of citizens is not required.

8. Our Case Studies

Reports into data sharing commonly focus on identifying barriers standing in the way of data sharing. However, a significant amount of data is successfully shared across the public sector, as well as with outside organisations. The following case studies explore such examples. These enable an understanding of how barriers to sharing are overcome and whether there are lessons for future data sharing projects.

8.1 Overview

The case studies explore different ways personal data has been shared. They deliberately concentrate on the sharing of some of the most sensitive and largest datasets held by the public sector. In each case, data has been successfully shared and the objectives of the project have been achieved. The case studies were selected to enable an examination of a wide range of data sharing scenarios, including sharing with private organisations, individual citizens, and central government.

Summary of CDEI Case Studies

| Case Study | Controller | Content | Receiver |

| Education data shared with Approved Suppliers | Department for Education | Education attainment and pupil characteristics | Accredited suppliers developing analytical tools to be purchased by schools and local authorities |

|---|---|---|---|

| VAT Register Shared with Credit Reference Agencies | HM Revenue & Customs | Business VAT data | Credit reference agencies |

| Troubled Families Evaluation | Local Authorities, Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government, Department for Work and Pensions, Department for Education | Various | Final data set analysed by MHCLG - ONS contracted as a trusted third party to collate the data |

| Sharing Patients’ GP Records | GP practices | Medical record | Enabling individual patients to access their medical record and share it with other bodies e.g. local authority social care providers |

| DeepMind / Google Health Medical Diagnosis | Royal Free NHS Hospital Trust | Patient test results | Google/DeepMind |

Education Data Shared with Approved Suppliers (Analyse School Performance)

The Department for Education holds a wide range of information about students who have attended schools and colleges in England since 2002 (about 21m individuals).

The National Pupil Database has grown to be the Department for Education’s primary data resource about pupils. It is shared with external education researchers, other departments, as well as private organisations. Our case study explores the provision of data (concerning pupils currently in the system, under the Analyse School Performance initiative)[footnote 30] to companies developing and offering data analytics products to schools. Decisions to share data are considered by the Department for Education’s Data Sharing Approval Panel, which can require appropriate safeguards to be in place prior to sharing information.[footnote 31]

VAT Register Shared with Credit Reference Agencies

Credit reference agencies are an essential part of economic infrastructure, ensuring businesses that need trade credit to purchase supplies are reliable borrowers. While large companies can be assessed on publicly available data, small businesses have few ways to reliably signal their financial status and can struggle to get access to the credit needed to grow. To address this, HMRC shares non-financial VAT registration data with credit reference agencies so these agencies can assess the credit worthiness of smaller businesses. Given the data includes information about small businesses (including registration number and name of business), some of the information could be viewed as being particularly sensitive.

Troubled Families Evaluation

The Troubled Families Programme is an initiative led by the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG) to intervene and provide better joined-up support for families experiencing multiple intersecting problems, for instance mental health problems, domestic abuse, and unemployment.

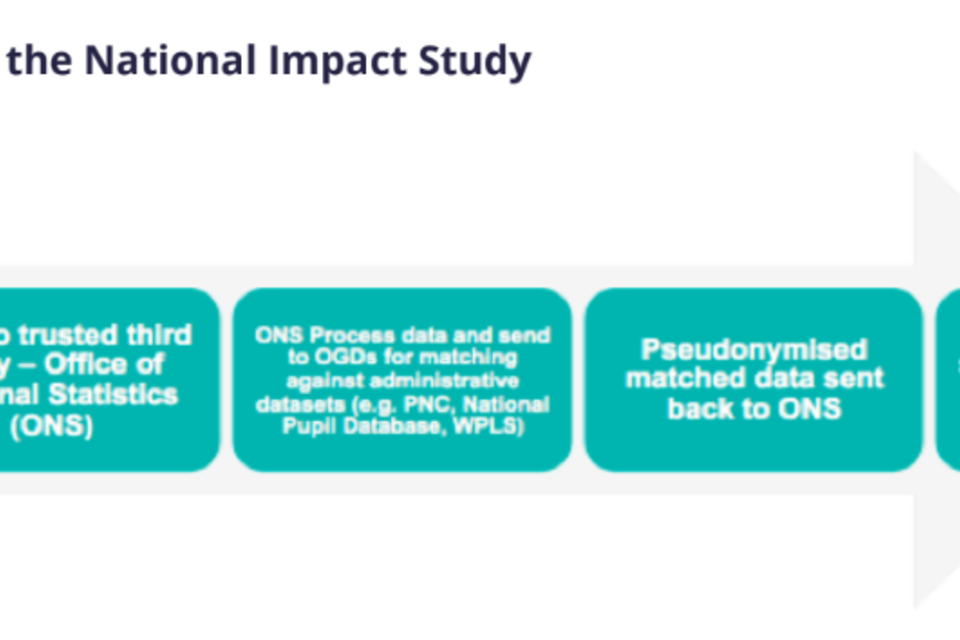

To evaluate the impact of the programme, MHCLG gathered data from upper tier local authorities as well as across a range of central government departments and passed it into the care of the Office for National Statistics for analysis. The information used includes offending data from the MoJ, employment and benefit data from DWP/HMRC, and attendance data from DfE. Data was collected for all families that are eligible for the programme, not just those enrolled, to provide a control group for the evaluation.

Sharing Patient GP Records

Since 2015, all NHS patients have been able to sign-up to GP online services and use a website or app to view parts of their GP record, including information about medications, allergies, vaccinations, previous illnesses and test results. GPs can share this data with patients through a number of accredited third party services. In some cases, patients are able to share their medical record securely with other providers e.g. non-NHS physiotherapists.

DeepMind Medical Diagnosis

The Royal Free started a project with DeepMind in 2016 where they have used the personal information of 1.6m patients to test the clinical safety of a new app (Streams), prior to it being deployed for direct care. Streams uses a range of patient data to determine whether a patient is at risk of developing Acute Kidney Infection and sends an instant alert to clinicians who are able to take appropriate action promptly. In 2017 the ICO ruled that the Royal Free failed to comply with the Data Protection Act when it provided patient details to Google DeepMind for the purposes of testing the app.[footnote 32] By 2019, Royal Free had completed all actions required by the ICO and they had no outstanding concerns about the app being used for the direct care of patients.

Summary of the value of data sharing realised in the case studies

- Enable evaluation of government programmes to inform future decisions and policy development.

- Support the development of new data driven tools to aid service delivery and diagnostics.

- Ensure new analytical tools are built using the best data available.

- Share data with third parties able to deliver important services not provided by the public sector.

8.2 Barriers Encountered and Solutions Applied

The case studies highlight that data sharing takes place for a range of purposes with varying value to citizens and the public sector as a whole. It is also clear that many of the identified barriers are surmountable and even help to ensure decisions to share are scrutinised. However, in many cases, public awareness is low and the approaches taken to sharing are inconsistent.

A common barrier faced by those wishing to share data relates to the inconsistent application of rules and standards for sharing. Individual departments set different requirements in relation to identifying legal gateways, security standards and making decisions around whether or not data can be shared. In some cases, this is because certain data is governed by specific legislation e.g. HMRC data or health data, making it challenging to adopt consistent approaches.

Navigating these hurdles takes time and resources, often including legal and technical expertise. If parliamentary approval is required, it may take years before data can be shared. Agreements to share may require new legal contracts and memoranda of understanding which also take time and expertise to draft. Even in cases where sharing is legally permissible, cultural barriers and risk aversion need to be overcome - which is why senior level buy-in is so important.

In addition, once an agreement to share data is in place, the limited adoption of common standards may mean significant work is needed before data can be shared.

| Barrier | Barriers identified in case studies | Solutions applied by the projects in the different case studies |

| Technical | * Different data standards in use (often because of legacy systems) across the public sector making the adoption of common standards difficult * Data quality is widely variable and limits the ability to connect records Hard to transfer large data sets securely * Insecure legacy systems |

* Commit resources and expertise to tidy-up data * Use third-party intermediaries (e.g. ONS) * Work with digital identity providers (which bring additional costs to sharing) |

|---|---|---|

| Legal | * Establishing the lawful basis for sharing takes time and isn’t always straightforward (DEA) * May need new agreements for each partner * Data controller’s requirements may not align with the expectations of individual clients |

* Create new legal gateways. Note, however, these can take time (possibly parliamentary approval) and resource to be approved * Share Privacy Notices which detail the purpose of the data sharing |

| Cultural | * Risk aversion is sometimes the result of the impact of historic data breaches * Different departments have different needs requiring separate data sharing agreements |

* Requires patience and senior level buy-in (and political support) * Establish clear legal routes as well as separate Memorandums of Understanding |

| Public Trust | * Limited individual control of what data is collected and what it is used for * Data is often retained for a long-time for research purposes, beyond the initial purpose * Gaining individual consent for such large datasets is very burdensome * Lack of transparency triggers public backlash when sharing becomes public, especially if shared outside government |

* Establish approvals committees to consider not just whether the data sharing is legal, but also whether it is ethical to share * Rollout client engagement strategies and proactively inform the public of new data sharing arrangements |

| Time & Money | While the barriers identified above may be surmountable they often require time and money to overcome. Thus the need to invest additional resources into data sharing can become a further barrier. This includes procuring legal advice as well as other expertise and investing in the technology required to share the data securely. |

8.3 The Barriers in Detail

Overcoming Legal Confusion

Before sharing data, legal gateways need to be identified. These provide an element of democratic legitimacy and therefore trust to the exchange but also sit alongside the Data Protection Act and the combination of these can create a confusing and inconsistent environment. Different datasets may be subject to different laws. Identifying the appropriate legal gateways is time consuming and leads to uncertainty. There are also occasions when organisations in the public sector have got this wrong. This was the case in the Royal Free case study, where the Trust was found by the ICO to have incorrectly interpreted the legal framework around data sharing for direct care.

In the case of HMRC sharing data with credit reference agencies, primary legislation was required which took several years to draft and be approved by Parliament. For the Evaluation of the Troubled Families Programme, separate data sharing agreements (Memoranda of Understanding) were needed between MHCLG and all other government departments, as well as 149 local authorities. Legal expertise was also required to identify legal powers to share data and to ensure the requirements of Data Protection legislation and the GDPR were met. Common law powers were eventually relied upon for MHCLG to share the data with other government departments.

In the case of the National Pupil Database (NPD) and other datasets held by the DfE, the Education Act 1996 and other pieces of legislation, including the Children Act 1989[footnote 33], provide the Department for Education (Secretary of State) with more discretion over decisions to share data. However, even in the case of education data being shared with accredited suppliers, new legal agreements were needed which ran to 50 pages. The Department needed to procure external legal support to draft the contracts for the different suppliers. Similarly, in the case of Ofsted sharing data on fostering agencies with the Alan Turing Institute, it took several months to finalise legal arrangements before the data was shared - despite it only being a 6 month project.

Identifying legal gateways is an important element of trustworthy data sharing. However, the current environment is confusing and can seem inconsistent. The need to engage legal specialists also introduced additional costs to data sharing which created further barriers to be overcome.

Role of Data Controllers

Despite legislation providing legal mechanisms for data sharing, the decision to share often rests with the data controller. This may mean that even in cases where an individual may want his/her data shared, the data controller may hinder this from happening. In the example of GP record sharing, there is variation across different practices. GPs decide which fields of their records patients can easily access and may also place controls around what may be shared with other bodies.[footnote 34]

In other instances, the decision to share rests with individual departments. For the Troubled Families Evaluation, MHCLG needed to work to secure senior-level buy-in across different departments to ensure the data sharing was authorised. This took considerable time and resource. Even under the Digital Economy Act, departments may refuse to share data (or delay the sharing of it) despite requests falling within the remit of the legislation.

A related challenge occurs when the benefits of data sharing are accrued elsewhere. In the case of GP records, GP practices may perceive that there is little value to them in enabling patients to share data, while significant costs may be required to put in place new systems. Similarly with the Troubled Families Programme, effort still had to be put into secure senior level buy-in as individual departments needed to commit resources to linking the data. The fact that the Troubled Families Programme is a high-profile initiative and tackled a range of issues of interest across government is likely to have made it less difficult to persuade departments to share their data. Projects which are less of a government priority may struggle to obtain the data they need, particularly if the value is accrued away from those providing the data.

Overcoming Technical Constraints

Data standards and quality

Sharing sensitive data requires high levels of security, which are hard to meet when data is often managed in legacy systems. It is particularly challenging when sharing across organisational boundaries, where each side may have different requirements for the security of their data and no shared infrastructure.