Global Britain, local jobs (HTML version)

Published 10 March 2021

Foreword

Free trade helped build Britain. It created jobs, businesses and entire industries, bringing wealth and prosperity to the UK and transforming the country into an economic powerhouse.

Today free and fair trade and the global trading system which supports it are under attack both at home and abroad. Yet there can be few things more important than championing free and fair trade, rooted in our values of sovereignty, democracy, the rule of law and a fierce commitment to high standards. It is free and fair trade that has helped reduce poverty on a scale unprecedented in human history. It is free and fair trade that will help our country bounce back from the damage caused by the coronavirus pandemic. It is free and fair trade that will help us to realise the ambitions of Global Britain. And it is free and fair trade that will bring huge economic benefits to this country, helping to create good quality and highly paid jobs in every part of the UK.

This is why I am proud to present the first report by the Board of Trade. For the first time in almost 50 years, the UK is in control of its own trade policy and we have renewed this centuries-old institution to bring together leaders in business, academia and government. The Board’s Advisers will support the government on its trade strategy, provide intellectual leadership on trade policy, and help make the case for free and fair trade across the world. The quarterly reports published by the Board of Trade will highlight key trade issues, promote the concept of exporting and demonstrate new global opportunities for UK businesses. As a nation we have not been in a position to steer our own trade debate for generations. Now we can and I believe the Board will play a crucial role in this vital discussion.

We have a great story to tell as a trading nation, and now as we set out into our future as an independent country with the whole world as its marketplace, we will champion values-driven free trade as a force for good in the world and a driver of prosperity for every part of the United Kingdom.

The Rt Hon Elizabeth Truss MP

President of the Board of Trade

Secretary of State for International Trade

Executive summary[footnote 1]

This first report by the Board of Trade sets out the unabashed case for free and fair trade and the opportunity for Global Britain to herald a new era rich in jobs, higher wages and opportunity.

There are 8 eight key points to draw from this Board of Trade paper:

1. Free and fair trade helps raise global prosperity

-

Through increased specialisation and the spread of technological advances around the world, trade has helped raise living standards and lift 1.2 billion people out of extreme poverty since 1990.

-

Countries that have opened up their economies – such as Australia, New Zealand, and Singapore – have benefitted from faster economic growth, higher incomes, and more jobs.

2. Trade-led jobs are vital to the UK economy

-

In 2019, the UK was more open to trade than at any point in its history. The UK was the fifth largest exporter in the world and the value of exports equated to almost a third of GDP.

-

Exports supported 6.5 million jobs across the UK’s regions in 2016, of which 74% are outside London and the majority (57%) were supported by exports to non-EU countries.

3. Trade-led jobs are better paid and more productive

-

It is estimated that median wages in jobs directly and indirectly supported by exports were on average 7% higher than the national median wage in 2016.

-

Goods exporting businesses are also a fifth (21%) more productive on average than those who do not export.

4. Trade benefits consumers, especially those on low incomes

-

Free trade lowers prices, increases consumer choice, and raises the quality of products available to UK consumers.

-

Without trade, the average UK consumer would be a third worse off. Those on low incomes – who benefit disproportionately from access to tradable goods – would be worse off in the absence of trade.

5. The UK has an opportunity to tap into the fastest-growing markets and sectors of the future

-

Almost 90% of world growth is expected to be outside the EU over the next 5 years. The future of the global economy lies to the East in the Indo-Pacific – 65% of the world’s 5.4 billion middle class consumers are expected to be in Asia by 2030.

-

Growth in digital trade, services trade, and green trade are all expected to accelerate this decade. The export market opportunity for the UK’s green sector is estimated to be worth up to £170 billion a year by 2030.

This economic and geopolitical context leads to 3 recommended priorities for the UK:

6. The UK should promote an export-led recovery

The government should:

- seek to internationalise the economy

- consider setting an ambitious target to boost exports by 2030

7. The UK should continue to strike new trade deals to benefit its citizens

The government should:

- build on the success of the UK Global Tariff and continue to liberalise trade and open up markets around the world for UK businesses

- seek to consistently reduce trade barriers through bilateral negotiations and enhance the freedom and fairness of trade through plurilateral initiatives

- deliver on the manifesto commitment to cover 80% of UK trade with free trade agreements by the end of 2022 by concluding existing FTA negotiations with the US, Australia and New Zealand

8. The UK should lead the charge for a more modern, fair and green World Trade Organization

The government should:

- play a leadership role in retooling the global trading system to unlock the growth potential of services, digital and green trade

- unblock the World Trade Organization (WTO) by resolving the WTO Appellate Body stalemate, challenge anti-competitive practices that distort trade flows, and hardwire fairness into the global trading system

Key figures (1)

Key figures:

-

1.2 billion lifted out of extreme poverty since 1990, helped by trade

-

6.5 million UK jobs supported by exports (23% of all jobs)

-

74% of export-related jobs are outside London

-

57% of export-related jobs are linked to non-EU trade

-

31% value of exports relative to UK GDP

-

7% average wage premium paid by exporting sectors

-

21% productivity premium for exporting businesses

-

1/3 worse off - UK consumers without trade

The Board of Trade

The Board’s role

The Board of Trade is a government body which has existed in various forms for almost 400 years – even before the days of Adam Smith and David Ricardo. Its purpose is to raise awareness of the benefits of international trade, campaign globally for free and fair trade and work with international counterparts to build a consensus for open markets and fight protectionism. It works alongside, but is separate from, the Department for International Trade.

The President of the Board of Trade is the Secretary of State for International Trade, the Rt Hon Liz Truss MP. The Board is supported by Advisers to the Board of Trade, who are drawn from academia, business, and government. They are independent and are appointed on one-year, non-remunerated terms.

The Board meets quarterly at locations across the UK’s nations and regions. It produces reports on key trade issues, published to coincide with Board meetings. This is the first quarterly report under the new Board of Trade.

Scope of this report

The Board’s reports are intended to bring new thinking to UK trade policy. They include reflections and recommendations from the Board of Trade’s Advisers which may differ from existing HMG policy. The Government is under no obligation to pursue these.

Board members and Advisers

The President of the Board of Trade is the Secretary of State for International Trade.

The 16 Advisers are:

- Secretary of State for Scotland

- Secretary of State for Northern Ireland

- Secretary of State for Wales

- Minister for Trade Policy

- Minister for Investment

- Minister for Exports

- Minister for International Trade

- The Hon Tony Abbott

- Karen Betts

- Anne Boden MBE

- Lord Hannan of Kingsclere

- Rt Hon Patricia Hewitt

- Emma Howard Boyd

- Michael Liebreich

- Rt Hon the Lord Mayor of the City of London, William Russell

- Dr Linda Yueh

Part 1: The case for free trade

Seizing the moment

We in the global community are in danger of forgetting the key insight of those great Scottish thinkers, the invisible hand of Adam Smith, and of course David Ricardo’s more subtle but indispensable principle of comparative advantage, which teaches that if countries learn to specialise and exchange then overall wealth will increase and productivity will increase, leading Cobden to conclude that free trade is God’s diplomacy – the only certain way of uniting people in the bonds of peace since the more freely goods cross borders the less likely it is that troops will ever cross borders.

Prime Minister Boris Johnson, February 2020

For the first time since 1972, the UK is in charge of its trading future. Such moments are rare and offer a once in a generation chance to rethink and reset. The decisions made over the next 2 or 3 years will set the course of UK trade policy, and thus affect the British people’s standard of living, for decades.

As a newly independent trading nation, the UK can fully harness the power of trade, but to fully thrive we will need to beat back protectionism. Free and fair trade is a force for global good which has boosted productivity and life chances for developed and developing nations alike. But despite the clear benefits of trade – in terms of raising productivity, lowering prices, increasing consumer choice and raising living standards – support for free trade has ebbed and flowed over the past 200 years. As the world reels from the second global recession in as many decades, free trade and the global trading system on which it depends are under attack again and the spectre of protectionism is on the rise.

To achieve the government’s ‘Global Britain’ vision and help level up the UK economy we will need to champion the case for free trade at home and abroad. The aim of this chapter is to serve as a reminder of the core arguments for free and fair trade and the benefits that it has brought to the UK and the world.

The UK’s pioneering role in free trade in theory and practice

The UK has a proud history as an independent free trading nation, inspired by influential British thinkers – such as Adam Smith and David Ricardo.

Adam Smith was instrumental in highlighting the role that trade plays in enabling specialisation of production – one of the core benefits of trade. Specialisation increases productive efficiency (through economies of scale), leads to lower prices and higher living standards.

Writing in 1776, Smith highlighted the pitfalls of pursuing self-sufficiency rather than specialisation, and ignoring the benefits of trade:

By means of glasses, hotbeds, and hot walls, very good grapes can be raised in Scotland, and very good wine too can be made of them at about thirty times the expense for which at least equally good can be brought from foreign countries. Would it be a reasonable law to prohibit the importation of all foreign wines merely to encourage the making of claret and burgundy in Scotland?[footnote 2]

David Ricardo took the concept of specialisation a step further with his theory of comparative advantage, which showed that even if a country is more efficient at producing every type of good and service than another, it is still beneficial to specialise and import some products from overseas. Writing in 1817, the English political economist’s counter-intuitive theory showed that what matters for trade is not just absolute advantage – whether a domestic sector is more productive than its peers in other countries – but also its productivity relative to other sectors at home and abroad (‘comparative advantage’). In principle, a country could have higher productivity in the production of every good but still benefit from trade. Trade enables countries, businesses and individuals to specialise in the sectors they are relatively more efficient at producing, and by doing so unlocks significant gains in living standards. By connecting comparative advantage to the gains from trade, Ricardo’s insight remains one of the most powerful arguments for free trade as a win-win for all countries involved. [footnote 3]

Britain put these insights into practice with the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846, which exposed businesses to competition from abroad and spurred them to specialise in higher value-adding industrial activity. The Corn Laws – a system of heavy duties on agricultural imports and subsidised exports – were a form of protectionism that redistributed wealth from the poor to the rich, and from the general population to wealthy landowners. The repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846 through a unilateral reduction in tariffs marked the dawn of a new era for Britain. Trade liberalisation and the competitive spur it provided to British businesses helped accelerate the uptake of ground-breaking innovations such as the advent of steam locomotion and telegraph communication. From 1846 to 1900, UK average tariffs fell from 25% to below 10%, GDP tripled, and GDP per capita increased by 60%.[footnote 4]

100 years later in 1945, the UK was instrumental in laying the foundations of the global trading system, which has underpinned rising living standards for the past 75 years. In the aftermath of the Second World War, the UK and 22 other countries established the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), the precursor to the World Trade Organization (WTO), which now has 164 members. The GATT cemented the Most Favoured Nation (MFN) principle in international commerce, which reduced discrimination between trading partners, and ushered in a wave of industrial tariff reduction and trade liberalisation. Through successive negotiations MFN tariffs have fallen from 17% in 1988 to 8% in 2016,[footnote 5] while global trade as a percentage of GDP has more than doubled from 27% to 60% from 1970 to 2019.[footnote 6]

At the beginning of 2021, the world finds itself at another crossroads, with populations and economies in lockdown, the global trading system fragile and protectionism ascendant. We cannot give into protectionism – history is littered with examples of the folly of that approach. The disastrous impact that the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act (and related retaliatory measures) had on both the US and world economy in the 1930s – deepening the Great Depression – is all the reminder we need. Free and fair trade is as vital today as it was then, and we must espouse the benefits of free trade both at home and abroad. So how has free trade benefitted the world?

International insights: the benefits of free trade around the world

Free trade is a source of shared global prosperity. Free trade has helped contribute to global growth through two main routes.

First, trade has helped countries make the most of what they have got, by enabling them to specialise and increase the size of markets they can access. It should come as no surprise that those countries that have integrated the most into global supply chains – such as Vietnam - have seen particularly rapid falls in poverty.

Second, trade has helped expand what countries have by incentivising innovation, higher productivity and, in turn higher income. For example, Morocco has benefitted from transformative foreign investment from the likes of Renault/Nissan, which positioned it as a leading centre for African automotive production with a € 1 billion investment in a plant in Tangier.[footnote 7]

Economies that are more open to trade, tend to grow more quickly. Liberalising reforms can have rapid and sizeable effects on countries’ growth prospects - one World Bank estimate suggests that, in countries that undertook substantial trade reforms, annual per capita GDP growth was on average 1.5 percentage points higher in the years following the reforms.[footnote 8]

There are myriad case studies that illustrate the potential gains from trade liberalisation. Box A summarises the experience of three countries – Australia, New Zealand and Singapore - that used trade liberalisation as a spur to growth.

The transformational potential of trade has been particularly stark in the developing world. Over the past 3 decades, export-led growth in tradeable products has been a key route for low-income countries to achieve sustained economic growth.[footnote 9] Trade has helped lift 1.2 billion people out of extreme poverty between 1990 and 2017. This reduction in poverty is all the more remarkable given the world’s population has increased by around 2.2 billion over the same period. Put another way, 9% of the world’s population lived on less than $1.90 per day in 2017 – down from 36% in 1990.[footnote 10]

Two modern developments have added to the potency of trade as a route to development: the rise of Global Value Chains (GVCs); and the rules-based trading system. GVCs have existed for centuries, but they grew particularly rapidly from 1990 to 2007 as technological advances and lower trade barriers – due to the role of the WTO – induced manufacturers to spread production processes beyond national borders. In 2007, half of all global trade flowed through GVCs. By facilitating the subdivision of production processes into more efficient parts, global supply chains have helped all economies to intensify their specialisation, raising the value each adds to traded products and supporting higher wages and profits; and provided an easier route for developing countries to graduate from being primary producers to manufacturers and hence become integrated with the global economy. The World Bank estimates that shifting from producing basic commodities to integrating into manufacturing GVCs leads to around a 6% rise in per capita income in developing countries on average after one year.[footnote 11] In addition, as technology has enabled their integration into the global economy, the WTO has safeguarded the common interests of smaller economies against disputes that might otherwise have been settled by the hard facts of market size. The rules-based trading system is the foundation on which the modern gains from trade are built.

Box A: International case studies of the impacts of trade liberalisation

Trade and openness can help economies prosper even in the face of external shocks. This section sets out three examples where countries have used trade liberalisation to reinvigorate their economies and chart a course to rapid economic growth: Australia, New Zealand, and Singapore.

Australia

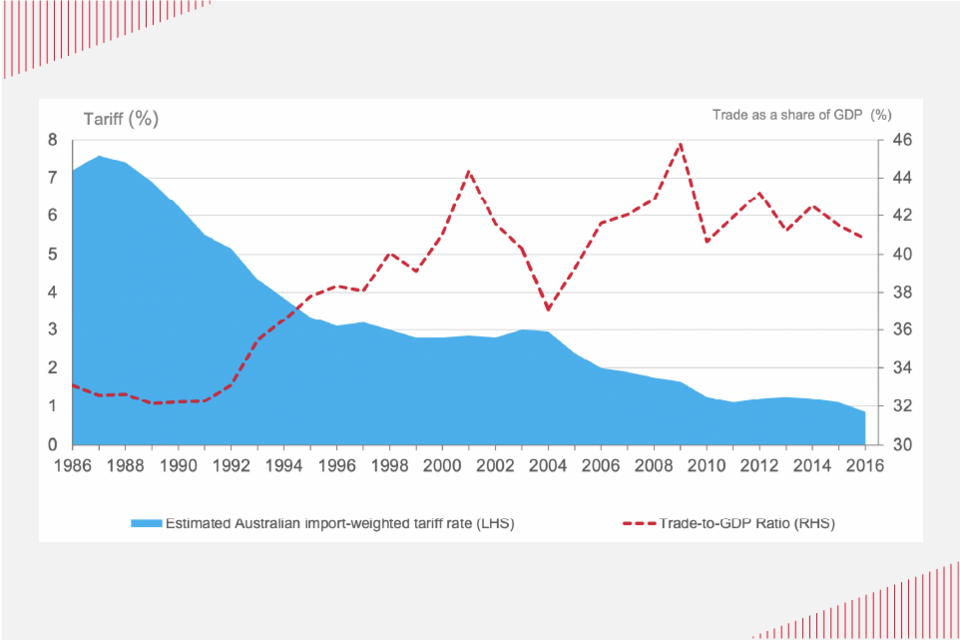

Since the 1970s, and in response to the breakdown of the Bretton Woods system, Australia has progressively liberalised its trade and increased its integration into the global economy. That liberalisation has taken the form of unilateral, bilateral and multilateral steps. As a result, since the mid-1980s the average tariff rate in Australia has fallen from over 7% to less than 1%, with 79% of all imports now tariff-free.

This period of liberalisation has coincided with higher economic growth and increased trade. The Australian Government estimates that in the three decades to 2016, real GDP was 5% higher due to goods trade liberalisation. Trade has expanded even faster as a share of GDP rising by around 10 percentage points over the same period.

By encouraging innovation and increasing the size of its potential market, liberalisation has driven Australia’s key industries to prosper. For example, research and development into more efficient techniques has enabled Australia’s agricultural sector to lower its costs and improve productivity. As a result, Australia has developed into a major agricultural exporter with a world-class wine industry.

Tariff liberalisation helped drive a rise in the trade intensity of Australia’s economy

Box A figure (1)

Sources: ‘Australian Trade Liberalisation, Analysis of Economic Impacts’. The Centre for International Economics for the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, October 2017, and World Bank Development Indicators for trade to GDP ratio.

New Zealand

Like Australia, New Zealand’s reforms from the mid-1980s were a response to an external shock. The decision by the UK – previously the destination for almost all of New Zealand’s agricultural exports – to enter the European Economic Community (EEC) in 1973 prompted a large-scale restructuring of New Zealand’s economy and a rethink of its approach to trade policy.

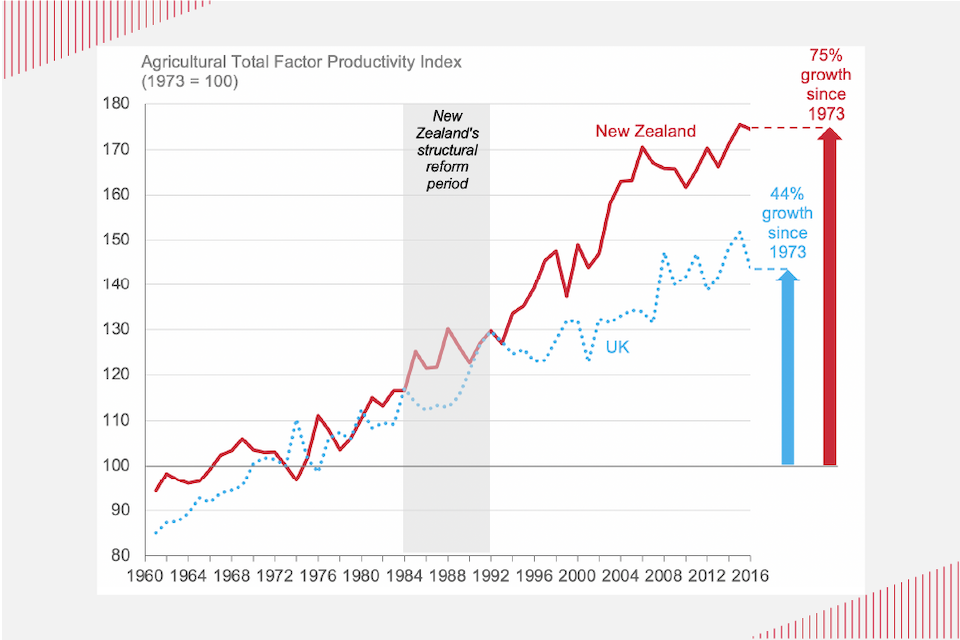

Despite having a population of just over 4 million, New Zealand now produces enough food for 40 million. Trade liberalisation, alongside other reforms, was crucial in both creating that surplus and finding a market for it. For example, exposure to competition and removal of subsidies have increased the productivity of New Zealand’s sheep farming industry by 160%, reduced land use by 20% and reduced emissions per kg of output by 30% relative to 1990. Market access has also enabled New Zealand to export its productivity. Since 1990, the nominal value of wine exports rose more almost a hundred-fold from NZ$18 million to NZ$1.5 billion in 2015. New Zealand has a range of FTAs with countries bordering the Pacific that have supported that process. This includes FTAs with fast-growing emerging markets like Thailand. New Zealand-Thai trade more than doubled in the decade after they signed their FTA in 2005. Whilst not the perfect comparator for a range of reasons, there are lessons the UK can draw from the New Zealand experience.

New Zealand’s structural reforms including tariff liberalisation increased agricultural productivity growth relative to the UK

Box A figure (2)

Sources: ‘The Case for Global Trade in an Era of Populist Protectionism: Lessons from New Zealand’, The Policy Exchange, Dec 2016, and ‘Global Britain should learn from New Zealand’s mistakes’, The Spectator, June 2020. US Department for Agriculture International Agricultural Productivity.

Singapore

Singapore’s turn to free trade followed its tumultuous separation from Malaysia in 1965. Its exit from that union forced it to shift its growth strategy from one focused on exporting within a common market protected by high tariff barriers, to one increasingly based on free trade and export promotion. That pivot has paid dividends over the past 50 years as Singapore has risen to become one of the richest countries on earth, on a per capita basis.

Singapore’s success has been based on openness. 96% of all imports enter free of duty - tariffs are levied on just 6 tariff lines. A capital account virtually free of restrictions has also fostered investment flows. And Singapore has become a major exporter in its own right. Having started life in the 1960s largely as an entrepôt trader with re-exports accounting for 90% of all exports, that share has fallen to around 35%.

Singapore’s openness is supported by a web of plurilateral, multilateral, and bilateral agreements. It was one of the founding members of ASEAN in 1967, joined GATT in 1973 and then the WTO in 1995. And it has eliminated tariffs for imports from FTA partners, including the US, EU and UK.

Source: IMF (1995) ‘Singapore - a case study in rapid development.

Part 2: The benefits of free trade for the UK

Openness to trade bestows numerous benefits on the UK: supporting the labour market, raising productivity, lowering prices and increasing consumer choice. As the UK has become more open, the potential gains from trade have increased. In 2019, the combined value of exports and imports reached almost two-thirds of UK GDP – a historic high and the most open to trade the UK has ever been.[footnote 12] In the same year, the UK overtook France to become the world’s fifth largest exporter and was the only top-10 global exporter to see an increase in its exports.[footnote 13] Since the end of 2019, the global pandemic has resulted in a sharp fall in global trade, which only recently began to rebound. Regaining lost ground is a priority for the UK as openness to trade is a building block of our prosperity. Figure 1 describes the key mechanisms through which trade benefits the UK: trade increases the market opportunities available to exporters and increases competition from exports. This supports the labour market, boosts productivity, lowers prices and increases consumer choice.

Figure 1: The main channels through which trade benefits the UK

Figure 1

Exports support the UK labour market

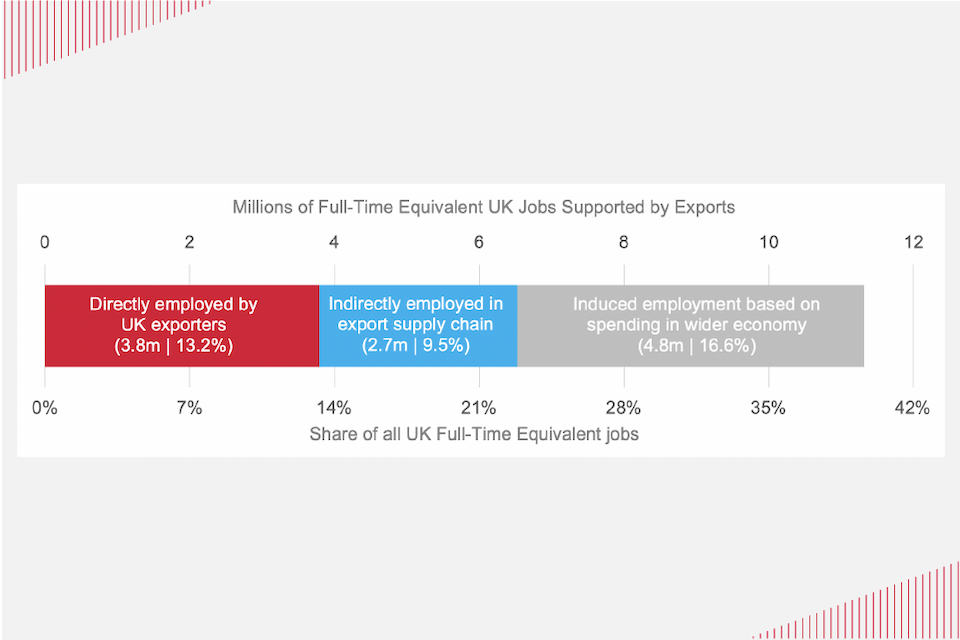

New research, published alongside this report, shows that UK exports are a major driver of UK labour market outcomes – supporting 6.5 million UK jobs in 2016.

Research conducted by the Fraser of Allander Institute at the University of Strathclyde (FAI) on behalf of the Department for International Trade shows an estimated 6.5 million full-time equivalent (FTE) jobs were supported by exports in 2016, equivalent to approximately 23% of all UK FTE jobs.[footnote 14] Around 58% (3.8 million) of these jobs were in exporting industries (jobs supported ‘directly’ by exports) and 42% (2.7 million) were in the UK supply chain of exporting industries (jobs supported ‘indirectly’ by exports). In addition, export activity helped support a further 4.8 million FTE jobs through the consumption spending of export workers in the wider economy. So, in total, approximately 11.3 million FTE jobs are linked to exports in some way – or 39% of all UK FTE jobs (Figure 2).

Figure 2: UK FTE jobs directly and indirectly supported by exports in 2016

Figure 2

Source: FAI research on behalf of DIT ‘Estimating the relationship between exports and the labour market in the UK’ (2021).

Note: Estimates should be viewed as central estimates with moderately broad confidence intervals.

Most of the UK’s 6.5 million export-related jobs in 2016 were driven by exports to non-EU countries and by businesses in the UK’s sectors of comparative advantage. The FAI research shows that significantly more FTE jobs (3.7 million) were supported by exports to non-EU countries than those that export to the EU (2.8 million) – with exports to the US accounting for the single largest source of jobs (Figure 3). Exports help support jobs in all sectors of the economy, but the sectors that drive most export-related employment are those where the UK has comparative advantage, including high-value manufacturing, financial services, and professional services (Figure 4).

Figure 3: UK FTE jobs directly and indirectly supported by exports, split by export destination, 2016

Figure 3

Figure 4: UK jobs directly and indirectly supported by exports, split by sector, 2016

Figure 4

Source: FAI research on behalf of DIT ‘Estimating the relationship between exports and the labour market in the UK’ (2021).

Note: Figures show UK FTE jobs directly and indirectly supported by exports in 2016. Estimates should be viewed as central estimates with moderately broad confidence intervals. Sector estimates are based on the ‘job supported by exports of each sector’ approach outlined in section 5.2 of the FAI report.

Export-related jobs also tend to pay higher wages than the national median, with the ‘exporter premium’ estimated to be around 7% in 2016. The FAI research estimated that jobs directly and indirectly supported by exports were on average 7% better paid than the national median in 2016. Even when the characteristics of employees in different firms are controlled for, the export premium still persists across sectors.[footnote 15] For example, analysis of UK chemicals firms found that exporting firms tend to pay wages 7.6% higher than similar firms that only sell domestically, while one US study found the export earnings premium to be 16% on average.[footnote 16] [footnote 17] Overall, the evidence is clear that exports help generate better paid jobs.

Trade boosts UK productivity

UK goods exporting businesses are on average 21% more productive than those that do not export, showing the benefits of internationalisation.[footnote 18] There are a range of reasons why exporting firms are more productive. First, there are substantial productivity gains from learning through exporting – being exposed to global competition increases the incentives for UK businesses to adopt best practice from market leaders – one influential study using data from Slovenia estimated these knowledge-gains boosted exporter productivity by more than 7%.[footnote 19] Second, exporting firms face greater competition so are more likely to invest in research and development to maintain a competitive edge – UK exporters invest 3 to 15 times as much of their revenue in R&D as domestically-focused firms.[footnote 20] Third, exporting firms tend to make more use of imports in their supply chains, enabling them to specialise in higher value-adding activity. Trading businesses do this through their participation in GVCs. Over recent decades GVCs, have supported businesses across different countries to focus more intensively on the parts of the production chain in which they excel, which allows businesses to increase profitability and to pay their workers more.[footnote 21]

Trade benefits UK consumers

Consumers benefit from the increased variety, greater choice, higher quality and lower prices that come with imports. One study found that FTAs signed between 1993 and 2013 increased the quality of UK imports by 26% and reduced the quality-adjusted price of imports by 19%.[footnote 22] That equates to a 0.5% fall in UK consumer prices, saving UK consumers around £5 billion each year. Consumers also benefit from the increased variety that come with increased access to imports – one study estimated that each consumer benefits by over £500 per year from the greater variety of goods due to trade.

Trade disproportionately benefits consumers on the lowest incomes, as things that are more tradable are also consumed disproportionately by the less well-off. One study estimated the impact of the UK closing itself off to trade. The average consumer would lose a third of their real income if there were no trade – illustrating the scale of the welfare benefit of trade for UK consumers.[footnote 23] But a consumer in the poorest 10% of the population would lose over a half of their real income.

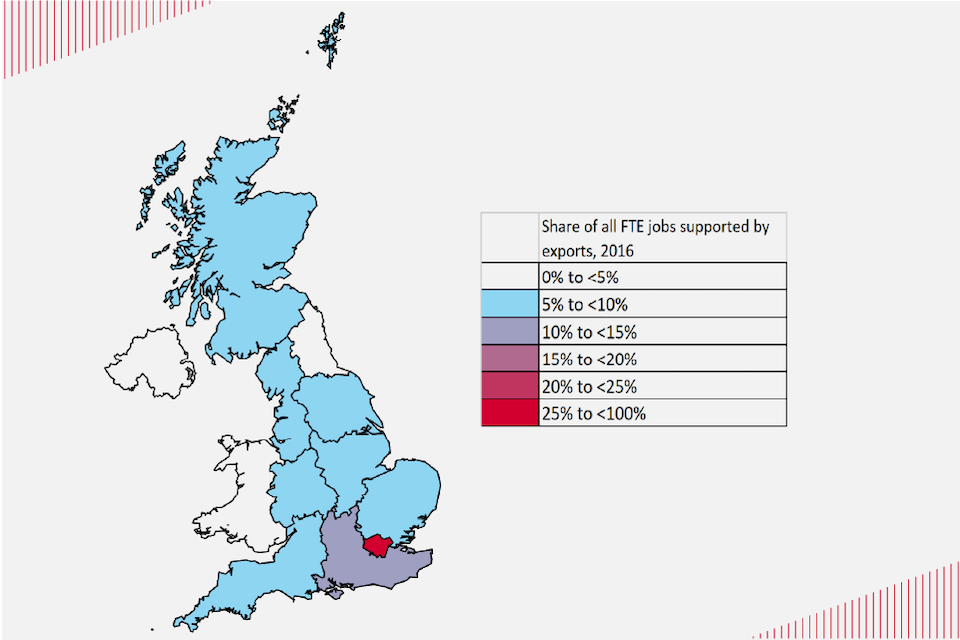

Trade can help level up the UK

Exports already supports hundreds of thousands of jobs in each region of the UK. The new FAI research shows that nearly three-quarters – around 74% - of all export-linked jobs were outside London in 2016. That breaks down to hundreds of thousands of jobs in each region, from 129,000 in Northern Ireland to 630,000 in the North West of England.

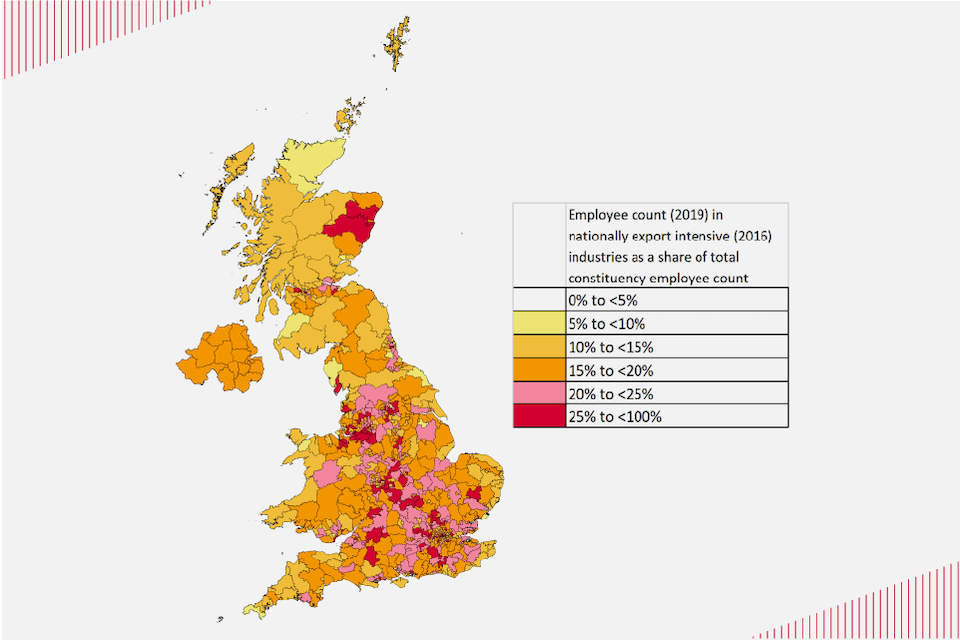

Exports will be central to the government’s mission to ‘level up’ the UK’s regions but employment in some regions is much more dependent on exports than others. Specialisation and geographical agglomeration effects mean that export-related employment is unevenly distributed across the UK. At the regional level, London’s labour market is by far the most reliant on exports, with over a quarter of all export-supported jobs in the UK estimated to be in London, according to the FAI. By contrast, outside London and the South East, the other UK regions each accounted for less than a tenth of all UK jobs supported by exports (Figure 5. Separate calculations from the Department for International Trade have looked at employment in nationally export-intensive sectors within each region at the constituency level (Figure 6). These local jobs estimates, which are not directly comparable with the FAI estimates, suggest that even in regions that are less open to trade in aggregate, there are local areas with high concentrations of industries that are export intensive at the national level. By seizing its destiny as an independent trading nation, the UK can broaden out these areas of high export activity and ‘level up’ the UK with higher productivity and higher-paying local jobs.

Figure 5: Share of UK jobs supported by exports in 2016, by UK NUTS1 region[footnote 24]

Figure 5

Figure 6: Share of UK employees (2019) in nationally export-intensive sectors (2016), by UK constituency[footnote 25]

Figure 6

Figure 7: Lowering trade barriers creates opportunities for businesses across the UK

Figure 7

We are excited by the prospect of new free trade deals between the UK and some of the fastest growing economies globally. By unlocking market access challenges for export powerhouses like the Scotch industry, eliminating high tariffs like India’s 150% Basic Customs Duty, will boost exports, generate investment and support jobs across the UK.

Dan Mobley, Global Corporate - Relations Director, Diageo

Our brand is recognised globally for beautiful designs and unmatched traditional craftsmanship which hold strong appeal for Japanese consumers. There is a rich tradition of tea drinking shared by the UK and Japan. In both our cultures, taking tea is a ceremonial act grounded in the everyday and the occasion. Our hand-made pieces have always been popular in Japan and we welcome any trade agreements which will benefit businesses like ours.

Jim Norman, Commercial - Director, Burleigh

1. British beef is back on the menu in the US

The USA’s longstanding ban on European beef – introduced in the wake of the BSE outbreak in 1996 – ended last year when market access for UK beef was granted. Beef producers across the UK are benefitting. The UK government in recent years has also opened the Japanese market to British beef and lamb, convinced China to lift its ban on UK beef, and opened up the Taiwanese market to British pork.

Foyle Food Group is one of the UK’s largest beef processors with 5 sites spread across the UK and Ireland and employs 1,300 people. Turnover for the group is £400 million with 25% of sales exported. Since the ban was lifted, Foyle has sold £3 million in products to the US market.

Kepak is Wales’s largest meat processor. The company is excited to be reviewing its supply chain availability to exploit the huge opportunities that exist in the US for its world-class products, in light of the successful re-opening of access for UK beef to the US market.

Scotch Whisky – untapped potential in growing markets

Scotch Whisky is the world’s top spirits export, worth £4.9 billion in 2019 to 180 markets. More than 10,000 people are directly employed in the industry and over 40,000 jobs across the UK are supported by it. Demand is growing around the world, especially in Asia (Source: Scotch Whisky Association).

Nevertheless, Scotch Whisky faces high tariff and non-tariff barriers in many markets around the world which restrict demand. The UK pushes these issues in all trade negotiations with a view to improving market access and making it easier to export. The UK has already secured the gradual elimination of the 45% import tariff in Vietnam through the UK-Vietnam FTA. Through the UK-Canada FTA it has also secured commitments to address practices by provincial Liquor Boards which limit market access.

Burleigh Pottery – benefitting from the UK-Japan Free Trade Agreement

Burleigh’s appeal in Japan stems from its heritage, provenance and unique decoration style. Its home at Middleport Pottery in Stoke-on-Trent attracts international visitors who like to see the 130-year-old pottery made using traditional techniques. The protections and provisions in the FTA increase companies’ confidence to export to Japan. Exports to Japan have grown 60% to £250,000 in the last year.

Tech firms will benefit from new free trade agreements

The cutting-edge digital and data provisions in the UK-Japan FTA go far beyond the EU-Japan deal. They include the free flow of data, a commitment to uphold the principles of net neutrality and a ban on data localisation that will save British businesses the extra cost of setting up servers in Japan. This will support UK fintech firms in Japan – such as Revolut and Wise – to innovate, grow and attract investment into the UK from Japan’s leading digital industry. It will also make it easier for UK tech and digitally-savvy firms to export to Japan.

5. Japan free trade agreement creating opportunities for Cambridge Satchel Company

The Cambridge Satchel Company is a heritage brand known for its iconic bags. With a turnover of £10 million and 125 employees, 47% of the company’s turnover comes from exporting. They have always exported and Julie Deane OBE, founder and CEO of the company, believes that has enabled rapid growth and increased brand awareness. Julie is optimistic that the Japan FTA will have significant benefits, especially in reducing tariffs on leather goods to 0% by 2028 and making market access easier. This is reflected in their forecasts for Japan: sales are projected to grow from £19,500 in 2019 to £150,000-200,000 in 2021 with continued growth in future years, meaning it could eventually become their biggest export market.

Part 3: Unleashing Britain’s potential

This is a pivotal moment for the UK – a once in a generation opportunity to reset our trading relationship with the world. Global Britain can harness the power of trade to tap into the bevvy of opportunities across the world – from rapid economic growth in the Indo Pacific to surging demand for digital, services and green trade. But to capitalise on these opportunities, the UK will need to overcome a number of challenges plaguing global trade, including the COVID-19 pandemic, rising protectionism, and a multilateral trading system that is in urgent need of modernisation. The UK has made a strong start in making use of its new trade policy levers, but it will need to go further and faster to bring the benefits of free and fair trade from every corner of the world to every region of the UK.

Global opportunities

Tapping into growth in emerging markets

Now is an opportune moment for Global Britain to foster trade with high-growth emerging markets. Emerging markets are forecast to dominate the world’s top 10 economies in 2050, with India in second place, Indonesia in fourth, Brazil in fifth and Mexico in seventh place.[footnote 26] These are the great economies of tomorrow that will be key trading partners for the UK to embrace. The UK will also need to continue to grow its trade with established markets, including the EU. But with almost 90% of world growth expected to be outside the EU over the next 5 years, the EU will account for a steadily shrinking share of the global economy and UK trade over time.[footnote 27] This is a continuation of a decades-long trend – in 2000, 54% of UK exports went to the EU, while in 2019 that share had fallen to 42%.[footnote 28]

Rising global living standards will create new centres of demand for the UK – two thirds of the world’s 5.4 billion middle-class consumers will be in Asia by 2030.[footnote 29] The global middle class is expected to expand by around 1.6 billion people over the course of this decade, with almost 1.5 billion of those new consumers living in Asia. As living standards rise, consumers tend to demand more of the goods and services that the UK is specialised in, creating a growing market for the UK’s world-leading businesses.

Harnessing digital growth

The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the uptake of digital technologies – amplifying the opportunities for non-physical trade. Digital technologies have been on a rising trend for decades. For example, between 2005 and 2014, cross-border data flows grew 45-fold – generating $2.3 trillion of revenue in 2014.[footnote 30] The role of e-commerce has also exploded – with 338 million new shoppers coming online between 2016 and 2018, almost 40% of whom were buying directly from overseas suppliers.[footnote 31] But the global pandemic has put these trends into overdrive – sky-rocketing the value of digital and tech-based businesses.[footnote 32]

The UK is well-positioned to ride this technological wave as it is already a world-leader in digital trade. The UK is the fifth largest global exporter of digital tech services[footnote 33] and ranked third (only behind the US and China) for venture capital investment in tech companies in 2019.[footnote 34] Domestically it is a key growth sector – growing over 4 times faster than the overall economy between 2018 and 2019, contributing £150 billion to the UK economy in 2019 and supporting 1.6 million jobs.[footnote 35] The UK is also home to the third largest number of ‘tech unicorns’ in the world (privately-held start-ups worth over $1 billion).[footnote 36] The UK’s digital prominence spans a wide range of industries. One in 10 songs streamed globally are by a British artist, with the UK’s share of global music streaming 4 times greater than its share of global GDP.[footnote 37] Digital innovation thus offers the promise of building on the UK’s spirit as a nation of ‘creators and makers’, but with a 21st century edge.

Accelerating demand for services trade

An increasingly digital and wealthier world will create disproportionately more opportunities in service sectors. Digital technologies helped to almost double cross-border trade in services between 2005 and 2017.[footnote 38] Rising demand from increasingly wealthy consumers in emerging markets also represents a key growth opportunity.

The UK’s world-leading and highly sophisticated service sectors are well placed to tap into these trends. The UK has a strong comparative advantage in service exports - it is the world’s second largest service exporter. [footnote 39] In 2007, the UK was the world’s highest-ranked large economy in terms of the ‘sophistication’ of services exports,[footnote 40] a measure of how much technology and innovation is embedded in those exports.[footnote 41] In addition, services have only become more important to UK trade over time – rising from 33% of exports in 2000 to 46% in 2020 – as the UK has become more innovative.[footnote 42] In 2020, the UK was ranked the fourth most innovative economy in the world.[footnote 43] The UK is also one of the top 10 ICT economies in the world, with its remotely delivered services trade with the world worth £326 billion in 2019, around 60% of UK services trade.[footnote 44]

Riding the green transition

Climate change is the greatest challenge of our time and will require a seismic shift in the structure of the global economy, but the green transition also creates significant opportunities for UK trade. There is great potential for the UK to export clean-growth products to help accelerate the transition to a sustainable world. The projected export opportunity for the UK’s low-carbon sector is estimated to be £60 billion to £170 billion a year by 2030.[footnote 45] The Prime Minister’s 10-point plan for a green industrial revolution is designed to capitalise on this opportunity, by mobilising £12 billion of government investment and spurring 3 times as much private sector investment by 2030.[footnote 46] This package is designed to support up to 250,000 British jobs and position the UK as a world leader in key green technologies. For example, the government’s Offshore Wind Sector Deal has set a £2.6 billion export target by 2030 – equivalent to a 7% share of the global market or roughly double the UK’s economic weight in the world.

Challenges to trade and future growth

To tap into the high growth opportunities available to the UK, the government will need to help address a series of challenges that risk holding back trade. This includes the global pandemic, current and future barriers to trade, rising protectionism, and deadlock in the multilateral trading system.

The global pandemic

COVID-19 is nothing short of a generation-defining shock that has amplified pre-existing trends and exposed fragilities that threaten the global trading system. It has caused the sharpest single-quarter fall in global goods trade ever recorded and the largest fall in UK GDP in over 300 years.[footnote 47] The global fallout from the pandemic will last years.

The IMF has spoken of a ‘long, uneven and uncertain’ recovery and estimates global government debt will have reached 98% of GDP in 2020.[footnote 48] [footnote 49] Meanwhile, it has been estimated that the equivalent of 255 million full-time jobs have been lost in working hours in the final quarter of 2020 alone.[footnote 50] Up to 115 million additional people could fall into extreme poverty by 2021 as a result of the pandemic.[footnote 51] In addition, with $14 trillion of fiscal support already dispensed,[footnote 52] and limited monetary policy room for manoeuvre, authorities will have less scope to protect the global economy against future shocks. Slower and more volatile economic growth risks slower growth in trade.

The UK is leading the world in the development, rollout and global distribution of vaccines to help the world bounce back from the COVID crisis. As well as being the first Western nation to start vaccinating its citizens, the UK has played a leading role in international schemes like COVAX, pledging £548 million of UK aid to help distribute one billion doses of coronavirus vaccines to 92 developing countries.[footnote 53] 600,000 doses of the Oxford AstraZeneca vaccine were delivered to Ghana on 25 February in the first consignment of COVAX.[footnote 54]

Current and future barriers to trade

Tariffs still represent a significant barrier to capitalising on future export growth. British businesses still face significant tariffs when selling their goods overseas, from Scotch whisky to cars and seafood. Pottery firms in Stoke-on-Trent currently face tariffs of up to 28% when they export to the United States, and Scotch Whisky is subject to a tariff of 150% when entering India and 60% when selling to Thailand. Tariffs like these amount to a tax on free trade with some of the UK’s partners. That is why UK negotiators have sought to maintain, and where possible expand, tariff reductions for key industries in the FTAs agreed so far covering 66 countries plus the EU.

At present, most trade barriers are non-tariff barriers created through regulations. The majority of regulations provide consumer safety, animal welfare, environmental or other important protections. The UK has long championed high standards through the EU and is committed to doing so in the future through the OECD and WTO. However, in addition to maintaining those high standards, we must ensure that regulations are proportionate, and minimise the impact on the ease of doing business to the greatest extent possible.[footnote 55]

Given the rapid pace of global change and the need for governments to respond to major global challenges like climate change and technological disruption, there is a risk that regulatory divergence could create new barriers to trade. Rapid innovation, the global reach of tech giants, and the ‘winner-takes-all’ nature of digital markets, all risk exacerbating inequalities and pushing governments into conflict with one another over how to regulate and tax big tech. The UK is endeavouring to reduce the risk of digital fragmentation through its FTA programme. For example, in its agreement with Japan, the UK agreed a ban on data localisation, which is saving British businesses from the extra cost of setting up servers in Japan. However, the risk of regulatory divergence remains a live one that is being fuelled by a number of underlying trends. For example, as countries adopt different national responses to the climate crisis, there is a risk that a patchwork of regulatory approaches drives a wedge between countries and holds back trade.

Rising protectionism

Protectionist sentiment has been on the rise for over a decade, but has intensified in recent years – fuelled by the COVID crisis. Since the G20 Summit in 2018, G20 governments have imposed subsidies four times as often than between 2014 and 2017.[footnote 56] The pandemic has also prompted a surge in import and export restrictions, which have had major negative consequences for the world’s developing countries. Export restrictions hit developing countries hardest due to their dependence on imports, and cause surges in global prices.[footnote 57] Such restrictions risk a downward spiral of protectionist tit-for-tat as other parties contemplate appropriate methods of retaliation, from banning goods to hiking tariffs or raising other barriers to trade.

There are a number of long-term structural drivers of rising protectionism, including geopolitical rivalry between the US and China. China is expected to overtake the US to become the world’s largest economy before the end of this decade. As the world shifts to a new multi-polar reality, we have seen a return to great power politics, waning belief in multilateralism and most starkly of all – a trade war between the US and China. These developments risk undermining the spirit of multilateralism that has underpinned global trade and prosperity for the past 75 years.

Trade is also often blamed for the rise in income inequality within countries, though the evidence suggests that technological disruption rather than trade is the main driver. Although trade plays a part, estimates from the International Monetary Fund suggest that the main driver of the upward pressure to inequality stemmed from technological progress as technology increased demand for, and therefore the premium paid to, higher skilled jobs.[footnote 58] The extent of this varies by region, with inequality in the developing world particularly affected by technological change. The greater returns accruing to higher skills point to the ultimate importance of education in resolving this policy challenge. Rather than trying to suppress technology, increasing access to education for less skilled and lower-income workers is more important in helping reduce income inequality.

Deadlock in the multilateral system

British exporters are being let down by a global trading system which has failed to keep pace with the advances of technology. Some of the rules developed through the World Trade Organization – such as those governing services and digital trade – have not been updated since 1995. Back then there were just 44 million internet users worldwide, now there are 4.7 billion. Modernisation is long overdue.[footnote 59]

Another tension is the perception that the rules of the game are unfair. In some ways, they are – trade liberalisation has disproportionately benefited manufacturing countries rather than service-focused economies like the UK. According to the WTO, barriers to services trade – on average - remain around double those to goods trade.[footnote 60]

Different interpretations of the rules - for example around the role of state aid and intellectual property – have also stoked trade tensions. These disagreements have exposed the limits of existing dispute arbitration mechanisms.

A strong start for the UK’s independent trade policy

The UK has agreed deals covering 63% of its bilateral trade and is using its independent trade policy to go further.[footnote 61] The UK’s new FTA with Japan goes further than the EU deal that preceded it – benefitting UK businesses across the country (see Box C). The UK is also pursuing new FTAs with the United States, Australia and New Zealand and should consider striking ground-breaking deals with India, countries across the Gulf and the Mercosur bloc in Latin America.

The UK is also seeking membership of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for the Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), which would anchor it in one of the world’s most vibrant trading areas. Together with partners such as Japan, Canada and Chile, the UK will help set the standard for modern trade through provisions serving its digital and data trade, among others.

The UK has also acted unilaterally to reduce barriers to trade by introducing its lower, simpler and greener UK Global Tariff regime (UKGT). The UKGT almost doubles the number of products that are tariff-free, relative to what was formerly applied under the EU’s Common External Tariff. A little under 50% of products now have zero tariffs, compared with 27% before the UK left the EU.[footnote 62] Over 100 environmental goods – known as the ‘Green 100’ - have been liberalised, to promote the deployment of low-carbon technologies.

The UK is rooting its approach for global free trade in its values of sovereignty, democracy, the rule of law and a fierce commitment to high standards. The UK is working with like-minded democracies to support freedom, human rights and the environment while boosting enterprise by lowering barriers to trade. This means that the NHS remains off the negotiating table, UK food standards must not be undermined and British farming must benefit from our trade policy, and any trade deal must help level up our country.

Box B: How the UK-Japan Free Trade Agreement benefits UK businesses

The UK-Japan Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA) was signed by International Trade Secretary Liz Truss and Japan’s Foreign Minister Motegi Toshimitsu in Tokyo on 23 October 2020. It was the first major trade deal that the UK struck as an independent trading nation and has gone further than the EU deal that preceded it.

The deal secured major wins for UK businesses that would have been impossible as part of the EU, including:

- protecting the free flow of data by agreeing a ban on data localisation requirements, which benefits industries like fintech and computer gaming from having to operate data servers in both countries

- improved mobility provisions that allow spouses to travel with businesspeople and a regulatory dialogue on financial services

- additional protections for the UK’s creative industries from music to TV

- recognition for Geographical Indications from across the UK, from Welsh Lamb, Scotch Beef, Armagh Bramley apples to English Sparkling Wine, subject to Japanese domestic processes

- lower tariffs for automotive manufacturers on key car parts, such as electrical control units, which will lower the costs of production in the UK

Every region of the UK is expected to benefit from the deal.

- The South West will be able to build on its specialist dairy exports, benefiting from reduced tariffs, as well as protection of important Geographical Indications such as West Country Farmhouse Cheddar. In 2019, almost a quarter (£0.7 million) of the UK’s dairy and eggs exported to Japan came from the South West

- Scotland will be able to benefit from both tariff liberalisation and protection of Geographical Indications for flagship products such as Scottish Farmed Salmon. Scotch Whisky will also enjoy protection as a Geographical Indication – in 2019, Scotland’s exports of beverages to Japan were worth £124.8 million

- Agricultural, food and drink businesses in Wales, Northern Ireland, the East and North of England stand to benefit from the reduction of tariffs on agricultural products (including pork and beef) and processed foods

- Exporters of clothing based in the Midlands, Yorkshire and the Humber stand to benefit from the removal of Japan’s apparel tariffs

- The UK’s dynamic and world-leading services industries in London and the South East stand to benefit from trade liberalisation, including cutting edge provisions on digital services. In 2019, UK-Japan digitally delivered services trade was worth £10.1 billion

Overall, the deal is estimated to increase UK GDP by 0.07% in the long-run – compared to a situation where the UK does not have an agreement with Japan. This is equivalent to £1.5 billion, an increase of £15.7 billion in UK-Japan trade, and an increase in UK workers’ wages by £800 million (compared to 2019 levels).

Source: Department for International Trade (2021) ‘Final impact assessment of the agreement between the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and Japan for a comprehensive economic partnership’.

Part 4: Recommended priorities

Now the United Kingdom is in control of its future as an independent trading nation once again, there are 3 priorities the Board of Trade believes the UK should focus on to maximise success.

1. The UK should promote an export-led recovery

The UK needs to learn from the successes of great trading nations such as Australia and New Zealand, who embraced the opportunities of free trade, creating jobs, increasing GDP, and raising wages.

The Board of Trade view is that Global Britain should:

a) Champion export – and investment – led growth as the drivers of economic recovery from the effects of COVID-19 and future prosperity by:

- considering setting an ambitious target to boost UK exports by 2030

- pursuing vigorous measures - ranging from ensuring UK exporters can compete effectively globally to eye-catching campaigns for targeted sectors/countries - to encourage firms to export and boost UK enterprise in global markets

- continuing to liberalise its trading relationships in a fair way

- campaigning across the country so that companies know about the opportunities that exist to sell their goods and services overseas and exploit the market openings the government is creating

Such efforts should herald a change of culture, where it becomes the expectation that every business operating in a tradable sector has an exporting wing. Exporting as an opportunity should be available to all firms, and trade has been important in bringing high-quality jobs and lasting prosperity to every corner of the United Kingdom.

b) Help communities adapt to the pace of technological change that is spread through trade by:

- supporting local communities with complementary domestic measures. It is better to manage change by investing in people’s human capital and firms’ ability to adapt than to try and stand in the way of progress

c) Support businesses the length and breadth of the UK to take advantage of export opportunities by:

- contributing to levelling up the UK by expanding on government support to all tradeable sectors that have growth opportunity

- increasing HM Government’s face-to-face support to businesses across all the UK’s nations

- supporting traders in familiarising themselves with the new trading arrangements following our exit from the EU

Such an approach will ensure the UK succeeds as an exporting nation, heralding a triumphant return to the world as an independent trading nation once again.

2. The UK should continue to strike new trade deals to benefit its citizens

A post-EU trade policy should deploy all available trade policy levers at the UK’s disposal to reduce the costs of trade and safeguard the UK’s values to ensure that trade is both free and fair.

The Board of Trade view is that Global Britain should:

a) Build on the success of the UK Global Tariff and continue to liberalise trade barriers and open up markets around the world for UK businesses by:

- reviewing the UK’s Generalised Scheme of Preferences – which provides duty-free, quota-free access to the UK market and tariff reductions for eligible countries – to offer the lowest income countries even better terms of trade

b) Consistently reduce trade barriers through bilateral negotiations by:

- delivering on the manifesto commitment to cover 80% of UK trade with free trade agreements by the end of 2022 by concluding existing FTA negotiations with the US, Australia and New Zealand

- renegotiating and deepening existing continuity deals with partners like Canada

- removing market access barriers for the industries of the future by pursuing ambitious data provisions in FTAs and other bilateral agreements, such as a Digital Economy Agreement with Singapore

- considering future FTA deals, over time, with the largest emerging markets of the future, such as India, the Gulf Cooperation Council and Mercosur

- making the most of increasing trade opportunities with countries around the world, in particular across the Commonwealth, and building on existing UK FTAs

c) Enhance the freedom and fairness of trade through plurilateral initiatives by:

- joining the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP)

- considering joining the Agreement on Climate Change, Trade and Sustainability, which aims to fast-track trade liberalisation in environmental goods and services

- using the UK’s Presidency of the G7 to pursue the Trade and Health Initiative (TAHI) to agree a global approach to health security that prevents tariffs and export restrictions being imposed on critical health products

Such an approach will help turbocharge the British economy, supporting high-quality jobs, better wages and increased productivity across the country, while helping restore public trust by showing the good that free trade can do.

3. The UK should lead the charge for a more modern, fair and green WTO

The UK should lead the charge with like-minded members to push the WTO into the 21st century by grasping the opportunities and tackling the challenges at the heart of modern trade.

The Board of Trade view is that Global Britain should:

a) Play a leadership role in retooling the global trading system to unlock the growth potential of services, digital and green trade by:

- building on the existing General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) to level up services trade, including by championing the WTO Joint Initiative on Domestic Regulation to ensure that qualification requirements, technical standards, and licensing requirements do not create unnecessary barriers to services trade

Dr Linda Yueh, Economist at Oxford University, London Businesses School and LSE IDEAS; UK Board of Trade

Upgrading GATS would be of great strategic and economic value, as services represent around two-thirds of global GDP. For the UK, services account for around 80% of national output.

There is more that can be done to support services trade. The UK should encourage a new WTO round centred on services and digital trade so that trade can be liberalised on a multilateral basis. A round can upgrade services for all but in the meantime, the UK should pursue liberalisation in a plurilateral or mini-lateral manner as outline

- building on the Joint Initiative on e-commerce announced at the 11th WTO Ministerial Conference in 2017 to promote cross-border digital trade and the free flow of data

- using the UK’s residencies of COP26 and the G7 in 2021 to work with our partners to push a green recovery to the front and centre of the multilateral calendar, including removing barriers to trade in environmental goods and services

Emma Howard Boyd, Chair of the Environment Agency, UK Board of Trade:

Trade, climate change and nature loss are interrelated and we have much to gain from realising the strengths of these connections. Trade and investment can drive more efficient production techniques as well as green goods, services and technologies. This should be a wellspring of job creation. I look forward to the upcoming Board of Trade paper that will focus on Green Trade.

This year, with the US returning to the Paris Accord, the UK’s Presidencies of COP26 and the G7 are golden opportunities to work with partners in the race towards the trillions in trade and investment needed to address climate change and nature’s recovery at home and abroad.

b) Unblock the WTO, challenge anti-competitive practices that distort trade flows, and hardwire fairness into the trading system by:

- resolving the WTO Appellate Body stalemate in a way that satisfies all members’ concerns, to ensure that trade rules are impartially enforced and the biggest countries cannot dominate smaller members

- challenging unfair subsidisation practices, that prevent open and fair competition for businesses in their home markets and abroad. This includes clamping down on unregulated fishing, which imperils the world’s fish stocks by completing the fisheries subsidies negotiations at the 12th Ministerial Conference of the WTO (MC12)

All this would require the UK to lead a global coalition of like-minded nations in pushing the global rules-based system into the modern era. Making it fit for purpose. would allow the UK to unleash its full potential as a confident and outward-facing world leader.

We are embarked now on a great voyage, a project that no one thought in the international community that this country would have the guts to undertake, but if we are brave and if we truly commit to the logic of our mission - open, outward-looking - generous, welcoming, engaged with the world championing global free trade now when global free trade needs a global champion.

I believe we can make a huge success of this venture, for Britain, for our European friends, and for the world.

Prime Minister Boris Johnson, February 2020

-

Data sources for all estimates provided in the Executive Summary are included in the main body of the report. The Fraser of Allander Institute at the University of Strathclyde (FAI) data on the links between trade and the UK labour market presented are estimates, based on modelling, and should be interpreted with a degree of caution. They should be seen as central estimates with moderately broad confidence intervals, and not as highly accurate point estimates – see FAI report for more detail. The estimates cover 2016 only so pre-date and do not cover the impact of COVID-19 and EU Exit. ↩

-

Adam Smith, Wealth of Nations (1776) ↩

-

Simon Evenett, Cloth for Wine? The relevance of Ricardo’s comparative advantage in the 21st century (2017), pp. vii, 1-3. David Ricardo, On the Principles of Political Economy, And Taxation (1817, 1821), Chapter VII ‘On Foreign Trade’. ↩

-

Irwin, A, Chepeliev, M. (2020) ‘The economic consequences of Sir Robert Peel: a quantitative assessment of the repeal of the Corn Laws’, NBER; GDP per capita in England 1800-1901 (Our World in Data). ↩

-

Felbermayr, G., Larch, M., Yotov, Y. and Yalcin, E. (2019) ‘The WTO at 25; Assessing the economic value of the rules based global trading system’, Bertelsmann Stiftung ↩

-

World Bank (n.d) World Bank Data, Trade (% of GDP) [link] ↩

-

His Majesty King Mohammed VI inaugurates new Renault-Nissan Alliance plant in Tangier, Morocco. ↩

-

Wacziarg, R. and Welch, K. H (2008) ‘Trade Liberalization and Growth: New Evidence’, The World Bank Economic Review, Volume 22(2) pp.187-231. ↩

-

Nick Lea, The Case for Tradable Growth. ↩

-

Source World Bank Development Indicators [link] [link] ↩

-

World Development Report (2020): Trading for development in the age of global value chains. ↩

-

The UK trade-to-GDP ratio peaked at 63.4% in 2019, with historic peaks in both the export-to-GDP ratio (of 31.1%) and import to GDP ratio (32.3%) according to the ONS UK Trade, December 2020 and GDP first quarterly estimate, Q4 (Oct to Dec) 2020 [link] ↩

-

UNCTAD (2019) ‘Goods and Services (BPM6): Export and imports of goods and service, annual, UNCTAD. ↩

-

FAI research on behalf of DIT ‘Estimating the relationship between exports and the labour market in the UK’ (2021). Estimates presented should be viewed as having moderately broad confidence intervals, rather than being point estimates. ↩

-

OECD (2017) ‘Export and productivity in global value chains: Comparative evidence from Latvia and Estonia’, OECD Economics Department Working Papers. ↩

-

Greenaway, David, and Zhihong Yu. ‘Firm-level interactions between exporting and productivity: Industry-specific evidence’. Review of World Economics 140.3 (2004): 376. ↩

-

Riker, D. (2015) ‘Export-Intensive Industries Pay More on Average: An Update’ (PDF, 317KB), Office of Economics Research Note, U.S. International Trade Commission. ↩

-

ONS, UK trade in goods and productivity: new findings, July 2018. ↩

-

De Loecker, Jan. ‘Detecting learning by exporting’. American Economic Journal (2013). ↩

-

Girma, Sourafel, Holger Görg, and Aoife Hanley. ‘R&D and exporting: A comparison of British and Irish firms’. Review of World Economics 144.4 (2008): 750-773. ↩

-

OECD (2018) Trade in Value Added. ↩

-

European Commission (2010) ‘Trade Growth and World Affairs’, European Commission [link]. Converted using Bank of England annual average spot exchange rate, Euro Sterling 31 Dec 2010 (time of publication). ↩

-

Fajgelbaum, Pablo D., and Amit K. Khandelwal. ‘Measuring the unequal gains from trade’. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 131.3 (2016): 1113-1180. ↩

-

Source: FAI (2021) Estimating the relationship between exports and the labour market in the UK. Note: UK jobs’ refers to FTE jobs. Estimates cover directly and indirectly supported jobs for 2016 – they do not capture the impact of COVID-19 or EU Exit. Estimates show jobs supported in a given region (for example London) by overall UK exports and are not comparable to data shown in Figure 6. Regional results do not consider residents from other regions commuting to the area. Data limitations mean that estimates may not capture the unique export patterns of the UK regions. See FAI (2021) for full list of caveats. ↩

-

Sources: ONS BRES (2019), NISRA BRES (2019), ONS UK Input-Output Analytical Tables (2016), DIT Calculations. Notes: The proportion of employees (2019 BRES ONS and NISRA) in each constituency that work in ‘export intensive sectors’ – defined as the top quartile of UK sectors that have the highest share of exports as a share of total domestic output at the national level (according to 2016 ONS input-output data). This calculation does not account for within sector and across constituency differences in export intensity and so does not tell us how export intensive or how many jobs are supported by exports at the constituency level. See DIT (2021) ‘Local jobs, trade and investment’, for caveats and data coverage. Estimates for Northern Ireland are for Northern Ireland as a whole and agriculture is excluded. ↩

-

PwC, The World in 2050, February 2015 (GDP at Purchasing Power Parity, 2014 US$). ↩

-

IMF WEO Database, October 2020. ↩

-

ONS Balance of Payments, July to September 2020. ↩

-

Kharas, H. (2017) ‘The Unprecedented Expansion of the Global Middle Class’, Global Economy and Development, Brookings, Brookings Institution. (The global middle class is defined as households with per capita income between $10 and $100 a day in 2005 PPP terms.) ↩

-

Bughin, J. and Lund, S. ‘The ascendancy of international data flows. VoxEU, 9 January 2017 ↩

-

Global e-commerce hits $25.6 trillion - latest UNCTAD estimates. ↩

-

Statista, Tech Giants shrug off Covid-19 crisis Oct 2020 and FT, How big tech got even bigger in the Covid-19 era, May 2020. ↩

-

TechNation (2020), ‘Unlocking Global Tech Report. ↩

-

TechNation (2020) ‘UK Tech for a Changing World’. ↩

-

DCMS Sectors Economic Estimates 2019 ↩

-

TechNation (2020) ‘UK Tech for a Changing World’. ↩

-

British Phonographic Industry, All Around the World, February 2021 report ↩

-

UNCTAD (2019) ‘Goods and Services (BPM6): Export and imports of goods and service, annual, UNCTAD Stat ↩

-

Mishra, Gable and Anand (2012) ‘Service export sophistication and economic growth’ ↩

-

Luxembourg, Switzerland and Ireland rank higher than the UK in terms of services exports sophistication, Mishra, Saurabh, Susanna Lundstrom, and Rahul Anand (2011), “Service Export Sophistication and Economic Growth”, Policy Research Working Paper 5606, World Bank. ↩

-

Source: ONS UK Trade, December 2020 ↩

-

KPMG 2020 Technology Innovation Hubs report ↩

-

ONS Trade in Services by modes of supply, UK: 2019 ↩

-

HM Government Clean Growth Strategy 2017 ↩

-

The ten point plan for a green industrial revolution, GOV.UK, November 2020 ↩

-

See WTO https://www.wto.org/english/news_e/news20_e/stat_18dec20_e.htm and ONBR ↩

-

Gopinath, G., 2021. A Long, Uneven and Uncertain Ascent. [Blog] IMF [Accessed 2 March 2021] ↩

-

IMF, 2021. Fiscal Monitor Update. ↩

-

ILO, 2021. ILO Monitor: Covid-19 and the world of work. Seventh edition: Updated estimates and analysis. [Accessed 2 March 2021]. Please note these estimates assume a 48 hour working week. Please see the technical annex in the full report for further information on the use of FTE jobs in these estimates. ↩

-

The World Bank, 2021. COVID-19 to Add as Many as 150 Million Extreme Poor by 2021. [online] ↩

-

IMF, 2021. Fiscal Monitor Update. ↩

-

UK meets £250 million match aid target into COVAX, the global vaccines facility, FCDO, GOV.UK, January 2021 ↩

-

Baldwin, R. and Evenett, S. (2009) ‘The collapse of global trade, murky protectionism, and the crisis: Recommendations for the G20’, CEPR ↩

-

Global Trade Alert, ‘Jaw Jaw, Not War War, 24th Global Trade Alert report’, June 2019 ↩

-

Espitia, A. Rocha, N. and Ruta, M. (2020) ‘Covid-19 and Food Protectionism’ World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 9253 ↩

-

IMF Survey: Technology Widening Rich-Poor Gap, IMF Research Department October 10, 2007 ↩

-

ONS UK total trade, all countries, July to September 2020 ↩