Barriers to Accessing Health Support for PIP, NS ESA, and UC Claimants

Published 7 October 2024

A report of research carried out by Basis Social on behalf of the Department for Work and Pensions.

DWP research report no. 1058

Crown copyright 2024.

You may re-use this information (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence.

To view this licence, visit the National Archives website.

Or write to:

Information Policy Team

The National Archives

Kew

London

TW9 4DU

Email: psi@nationalarchives.gov.uk

This publication is also available on our website at: Research at DWP.

If you would like to know more about DWP research, email socialresearch@dwp.gov.uk

First published October 2024.

Views expressed in this report are not necessarily those of the Department for Work and Pensions or any other government department.

Executive summary

This report presents findings from an in-depth qualitative research study exploring the experiences of Personal Independence Payment (PIP), New Style Employment and Support Allowance (NS ESA), and Universal Credit (UC) Health Journey claimants in accessing health support. It provides evidence to inform the design of future health signposting and support to claimants, as well as wider health and disability policy reform. The research was conducted as part of DWP’s Health Transformation Programme.

The research looked to understand the existing health support claimants access and the barriers they face in accessing health support, the relationship between accessing and using health support and a claimant’s benefit journey, what health support claimants feel would improve their prospects of becoming (or increasing) their economic engagement, and claimants’ openness to DWP in providing this (including levels of trust).

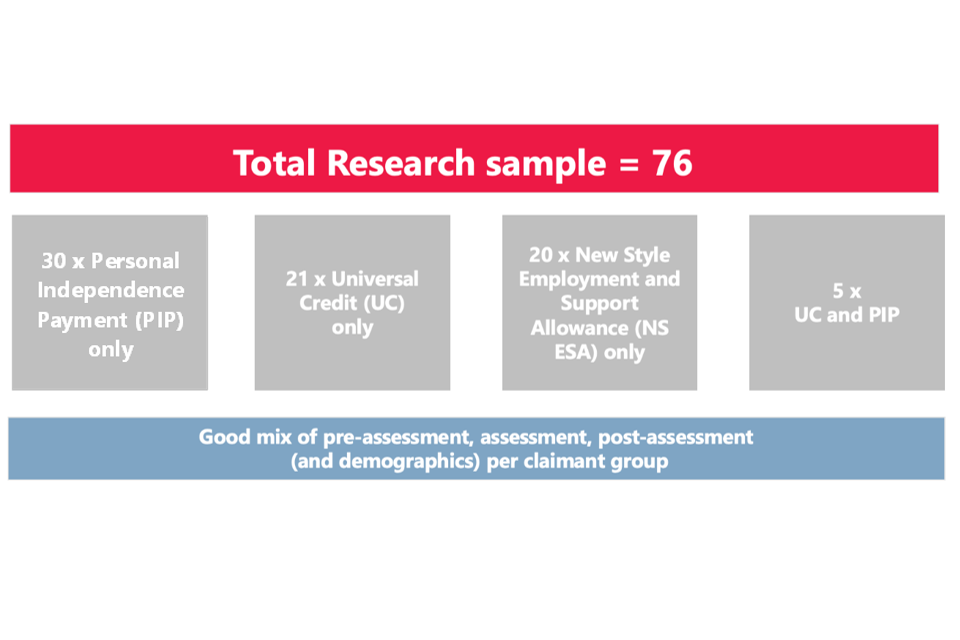

It involved 76 in-depth interviews with a range of claimants (according to type of claim and stage in the claims journey), including a small number of appointees, between December 2022 and March 2023.

Key findings and recommendations are as follows:

- participants were receptive to receiving health support signposting from DWP – none who participated in the research felt they had all the help they might need. There was no indication of mistrust regarding DWP’s motivations here. However, DWP is not seen as a health ‘expert’, and health support and signposting should be understood in this context

- four key principles have emerged that should be considered when implementing a broader health support programme: support must feel personal and tailored to the individual health and personal circumstances of claimants – this includes accounting for lifestyle needs and preferences, such as caring responsibilities or practicalities of needing to travel; support must have no strings attached – it should be entered into voluntarily and should not impact a claimants’ claims status; support must account for the skills levels and cognitive abilities of claimants, which can vary; and, support information may need to be shared with others in claimants’ support network

- it is important to consider individual and contextual needs for effective health support, as participants’ disabilities and health conditions are diverse and influenced by multiple factors

- there is a clear unmet health support need around mental health beyond any support managing claimants’ ‘primary’ disability and/or or health conditions

- health support would be strengthened by including broader support. For example, support in managing wider life challenges (e.g. housing or relationship breakdown) and practical administrative assistance for navigating the claims journey (particularly the application process, which can be challenging and exacerbate feelings of stress and anxiety for claimants)

- local charities and support organisations can be an important source of support for those aware of them. The presence of a strong interpersonal support network is associated with more successful health management and uptake of existing health support among claimants. Whilst those with a weaker interpersonal support network often have less successful health management

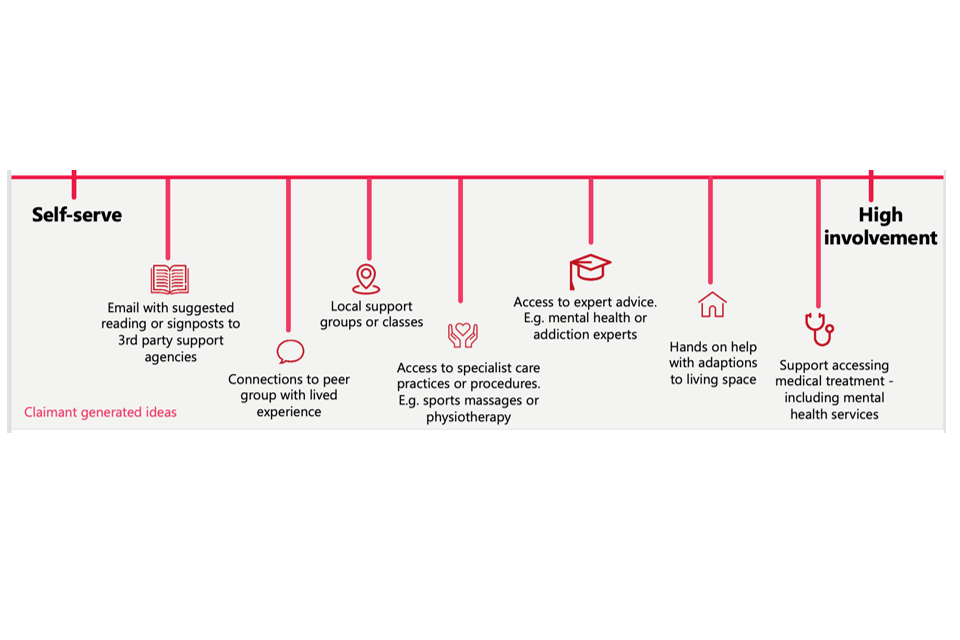

- participants described a diverse range of health support styles which could best meet their needs: from lower intensity ‘self-serve’ style signposting to more ‘high-involvement’, more personalised and intensive support for those with more acute needs. Accessibility and inclusion needs should also be actively considered (e.g., whether online or face-to-face contexts are more suitable)

- frontline staff and informal conversational settings are likely to offer the most suitable routes through which to offer health support, since they are experienced positively in the main for those in the claims journey

- this research was conducted against the backdrop of the new White Paper, Transforming Support: The Health and Disability White Paper[footnote 1]. It is encouraging to note that several research findings reinforce some of the new policies being proposed, including the offer of more personalised support to claimants

Acknowledgements

This research was commissioned by the Department for Work and Pensions in October 2022.

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the Department for Work and Pension’s Social Research team for their management of the project and their valuable input and support. We extend our thanks to Ailsa Redhouse, Dr Ashley Overton-Bullard, and Salma Afzal for their project leadership and contributions throughout the process.

This project was conducted by independent researchers, Basis Social, in partnership with disability research specialists, Open Inclusion, who helped to ensure the research was sensitive to the subject matter and the nature of the participants engaged.

Finally, we would like to thank all the claimants and appointees who gave up their time to participate in this research and share their experiences with us.

Author details

Rebecca Faulkner is an Associate Director at Basis Social.

Victoria Harkness is a Senior Director at Basis Social.

Cathy Rundle is a Research Manager at Open Inclusion.

Glossary

| Term | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Appointee | Someone formally appointed to act on behalf of a claimant who may face difficulties managing their own affairs. An appointee is responsible for handling the individual’s benefit claims, receiving payments, and ensuring that the benefits are used for the individual’s best interests. |

| Assessment stage interview | In this context, a research interview with a participant who had recently attended a DWP health assessment interview, but the result of this had not been communicated to them. |

| Condition management | Strategies used by an individual to actively address or minimise the impact of their disability and/or health conditions on everyday life and to improve wellbeing. This may involve the use of medical treatments, lifestyle modifications, and self-care practices. Used interchangeably with ‘health management’ (below). |

| Conversational settings | An informal or casual environment where people engage in dialogue or discussion. In the context of this research, conversational settings often refer to discussions with DWP work coaches or Jobcentre Plus staff, where claimants can share their views, ask questions, and receive support or guidance. |

| Disability and/or health conditions | A term used in the report to collectively describe the underlying reasons for a claimant receiving a disability benefit. It encompasses a range of physical, mental, sensory, or cognitive differences or challenges that may impact an individual’s day-to-day behaviour. This term has been chosen to acknowledge that the distinction between a disability and a health condition can be subjective and personal to each participant. |

| Fit note | Healthcare professionals issue fit notes to people to provide evidence of the advice they have given about their fitness for work. They record details of the functional effects of their patient’s condition so the patient and their employer can consider ways to help them return to work. |

| Healthcare professional | A healthcare professional is an individual who is trained and licensed to provide medical care, diagnosis, treatment, and support to patients. This term includes doctors, nurses, dentists, pharmacists, physiotherapists, psychologists. |

| Health assessment | This is a process conducted by DWP to assess an individual’s disability and/or health conditions in relation to their eligibility for certain benefits or support. The purpose of the assessment is to understand how an individual’s illness or disability affects their daily life. After the assessment, DWP has the information needed to decide on an individual’s benefits claim. |

| Health management | Strategies used by an individual to actively address or minimise the impact of their disability and/or health conditions on everyday life and to improve wellbeing. This may involve the use of medical treatments, lifestyle modifications, and self-care practices. Used interchangeably with ‘condition management’ (above). |

| Life-limiting conditions | Illnesses that have no known cure and are expected to significantly reduce a person’s lifespan. These conditions may progressively worsen over time and ultimately limit a person’s ability to carry out everyday activities. The focus of care for individuals with life-limiting conditions is often on improving their quality of life and managing symptoms rather than seeking a cure. |

| Medically complex | Refers to individuals who have multiple and/or severe medical conditions that require specialised care and coordination. These conditions may involve intricate diagnostic evaluations, extensive treatment plans, or the need for multiple healthcare providers from different specialties to manage the individual’s health effectively. |

| New Style Employment and Support Allowance (ESA) | A social security benefit for individuals unable to work due to a health condition or disability. Unlike the older form of ESA, it is based on National Insurance contributions rather than income. It provides financial assistance and additional support to help individuals meet their basic needs and access necessary services while they are unable to work. |

| NHS Talking Therapies | A form of NHS psychological treatment that involves engaging in conversations with a trained mental health professional to address emotional and psychological difficulties. These therapies aim to help individuals understand and manage their thoughts, feelings, and behaviours and are effective in treating conditions such as anxiety, depression, and stress. |

| Personal Independence Payment (PIP) | Is a social security benefit that provides a financial contribution to help individuals with long-term disabilities and/or health conditions to meet the additional costs related to their condition. PIP is based on the needs arising from a long-term health condition or disability rather than the condition or disability itself. PIP is not means-tested, is tax free and can be paid in addition to most other benefits received. Assessments for PIP involve a thorough evaluation of the individual’s ability to perform various tasks and activities. |

| Post-assessment stage interview | A research interview with a participant who attended a health assessment interview and who is aware of the result. This includes individuals in receipt of benefits or undergoing an appeal process. |

| Pre-assessment interview | A research interview conducted with a participant who had applied for a disability benefit but had not yet attended an assessment interview. |

| Trauma-informed approach | This is an approach to research which recognises and considers the potential impact of psychological trauma on participants and seeks to create a safe and supportive environment for them. It involves designing and conducting research with sensitivity to the potential triggers of retraumatisation that participants may experience. |

| Universal Credit | A welfare benefit that supports individuals and families with their living costs, including those who have health conditions or disabilities. It is designed to replace several existing benefits, making the application and payment process more streamlined. For individuals with health conditions, Universal Credit considers their specific needs, and they may receive additional support or allowances based on their circumstances. |

| White Paper | In this context, a White Paper is a concise, authoritative report issued by a government department. It outlines policies, proposals, or legislative plans on a specific topic and serves as a formal document to communicate government intentions and provide a basis for future legislation or policy changes. |

| Work coach | A DWP professional who supports individuals in their employment journey. They provide guidance, assistance, and personalised advice to jobseekers, helping them develop job search skills, explore opportunities, and create tailored action plans for finding suitable employment. Work coaches may also facilitate access to training, education, and support programmes to enhance employability. |

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | In full |

|---|---|

| ADHD | Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder |

| CBT | Cognitive behavioural therapy |

| COPD | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| DWP | Department of Work and Pensions |

| GP | General practitioner |

| HIV | Human immunodeficiency viruses |

| HTP | Health Transformation Programme |

| IT | Information technology |

| ME/CFS | Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome |

| NHS | National Health Service |

| NS ESA | New Style Employment and Support Allowance |

| PIP | Personal Independence Payment |

| UC | Universal Credit |

Summary

Overview

This report provides findings from an in-depth qualitative research study with claimants applying for or receiving a range of health and disability benefits, exploring their experiences in accessing health support. Specifically, it has looked to understand the views of claimants of Personal Independence Payment (PIP), New Style Employment and Support Allowance (NS ESA), and Universal Credit Health Journey (UC). It provides evidence to inform the design of health signposting and support to claimants in the future, as well as wider health and disability policy reform. The research was conducted as part of the Health Transformation Programme (HTP), which aims to enhance customer experience and trust in DWP services and improve overall efficiency of the claimant process. The HTP includes the development of a new Health Assessment Service and the long-term transformation of the PIP service.

Research aims

This research was commissioned to address evidence gaps regarding where DWP could further strengthen claimant engagement and offer timely and targeted health related support as part of the Health Transformation Programme (HTP)[footnote 2]. To understand this, the research aimed to explore the following key areas:

- what health support (clinical and non-clinical) do claimants have access to and use?

- what is the relationship between accessing and using health support and a claimants’ benefit journey?

- what health support do claimants on disability-related benefits feel would help improve their prospects of increasing their economic engagement?

- do claimants on disability-related benefits feel, and want, DWP to have a role in signposting to health support?

- would claimants trust DWP to support them with accessing health support (and would this lead to them trusting DWP in work orientated conversations)?

In practice, pursuing these objectives has required an adaptable and flexible approach. The participants in this study, some of whom were highly vulnerable, have meant it was important to adopt a practical, sensitive, and open line of questioning when delving into personal and potentially challenging subject matter.

Methodology

In-depth interviews were chosen as the best method for investigating claimants’ access to and engagement with health support, as they allowed for a detailed exploration of experiences, perceptions and attitudes, and a better understanding of contextual constraints.

Between December 2022 and March 2023, a total of 76 approximately 60-minute interviews were conducted by members of the Basis Social team with claimants, including 4 with appointees. Participants were carefully chosen to ensure a diverse representation of individuals claiming Personal Independence Payment (PIP), New Style Employment and Support Allowance (NS ESA), and Universal Credit (UC) Health Journey to understand how experiences and views differed between the different benefit types, if at all. A range of demographic characteristics was also captured to ensure diversity in the sample. The research team also spoke to claimants at different stages of their claims journey. All research was conducted in a sensitive and trauma-informed way in close collaboration with disability research experts.

key findings

The research has revealed a range of significant insights important to consider as part of any future approach to delivering health support for individuals claiming disability-related benefits.

To begin with, it has highlighted a clear and genuine desire among claimants to receive health support signposting from DWP. There was no indication of mistrust or doubt regarding the Department’s motivations in providing this assistance. No claimant felt they had all the help they could need, and thus welcomed additional information. Participants without strong support networks described finding the idea of proactive support particularly appealing. However, it is important to note that the participants in this research did not necessarily see DWP as a health expert. Therefore, it is essential to understand signposting and support within this context. This might include considering the involvement of specialists (who may or may not be medical practitioners) that those with more complex disabilities and/or health conditions might require.

Four key principles have emerged through the research that should be considered when implementing a broader health support programme. First, support must feel personal and tailored to the individual health and personal circumstances of claimants. This in turn will help them feel more confident in accessing it. This includes accounting for lifestyle needs and preferences, such as caring responsibilities they may have, or the practicalities of needing to travel to receive health support. Second, support must have no strings attached – it should be entered into voluntarily. Claimants want to know their claims status will not be impacted. Third, support must account for the skills levels and cognitive abilities of claimants, which can vary. Fourth, support information may need to be shared with others in claimants’ support network.

When asked about the actual types of health support that could enhance their wellbeing, claimants described a diverse range of support styles, spanning from lower intensity, light-touch ‘self-serve’ style signposting to more ‘high-involvement’, personalised and intensive support among individuals with more acute needs. Accessibility and inclusion needs should be actively considered in providing support, for example, the extent to which claimants can and would prefer to access health support online or in a face-to-face context.

The research also highlights how participants often apply for benefits during disruptive periods in their lives. Connecting them to support for managing broader life challenges like housing or relationship breakdown, as well as providing practical administrative assistance for navigating the claims journey, would aid in better condition management by reducing stress.

Poor mental health emerged in this research as the issue that claimants have most in common, and is the biggest apparent unmet health support need for this group. For some this has the potential to become the condition with the greatest impact on an individual’s life if left unaddressed. Since claimants described mixed levels of understanding about, and paid mixed attention towards, their mental health, the true extent of claimants’ struggles here is likely to be being under-reported to the Department during the benefits assessment process.

The research has also highlighted those aspects of the claims journey that might adversely impact claimants’ health. It is important that approaches designed to improve the health of claimants are not solely limited to the policy of health support signposting. Support should consider the elements of the claims journey which are inadvertently impacting claimants’ health in a negative way too. For example, difficulties participants described around the complexity of the application form.

Linked to this, claimants stressed that they would not want any support offer to increase the complexity of the application process or add additional stages to the journey, which was already felt to be cumbersome. Frontline staff and informal conversational settings for those that experienced them could potentially play an important role in health support delivery.

The quality of a claimant’s support network has also been shown to significantly influence an individual’s ability to manage their health needs and access available support. Claimants who had a strong support network of family, friends, and supporters not only had access to greater levels of ad hoc assistance when needed, but they also reported better mental health and increased motivation to engage with health services and overcome barriers to accessing care. Charities and third sector organisations are an important part of this support network for those claimants who are aware of them. They not only introduce health management ideas, but also help with administrative tasks required to access support. In contrast, claimants without reliable support networks reported challenges in managing their health effectively and had reduced capacity or motivation to contact known services, or to conduct independent research on health support. These difficulties were associated with lower overall levels of mental health among this group.

Participants’ experiences of NHS services varied significantly. Some instances of satisfactory care were described, with other claimants found to have experienced significant challenges in accessing timely and effective NHS healthcare. Indeed, many participants hoped that a key benefit of any future DWP health support might be its ability to connect them more effectively with the NHS services they were currently struggling to access.

Finally, we note how this research was conducted against the backdrop of the new White Paper, Transforming Support: The Health and Disability White Paper[footnote 3] It is encouraging to note that several research findings reinforce some of the new policies being proposed, including the offer of more personalised support to claimants. For example, recent proposals to improve direct Work Coach support for ESA and UC Health Journey claimants outlined in the White Paper are to be welcomed in the context of offering health support, as are proposals to increase Work Coach understanding of mental health conditions and building connections between employment advice and NHS Talking Therapy services.

Recommendations

The research highlights a number of considerations that the Department may wish to reflect on when developing any future health support and signposting initiatives.

- the health support offered needs to account for the needs, capabilities, and preferences of claimants. The wide range of disabilities and health conditions among claimants, along with the impact of contextual factors on health management, suggests the need for a highly personalised and individualised approach to designing and delivering health support. In defining high-quality health support, claimants themselves stressed the importance of ideas and information being directly relevant to their lives

- extra consideration should be taken when thinking about how best to offer support to claimants with complex needs. The design and delivery of support for this group may require input from specialists to ensure its suitability

- mental health support should be a priority, even where no mental health issues are known. The impact of condition management can be detrimental to mental health, whilst declining mental health can make it difficult to maintain condition management

- health support should include offering signposting to a wider range of support services, including housing, counselling, and application assistance. This approach could serve to help claimants free up more mental ‘headspace’ to focus on their own healthcare needs

- some of the challenges and stress participants reported about the claims journey itself might be relieved through better communication and education from DWP about what they can expect from the process upfront. Further, providing practical administrative assistance for navigating the claims journey (particularly the application process, which can be challenging for some) for those who need it might also be considered (whether directly or by signposting to relevant third party organisations)

- extra support to those claimants with poorer support networks or who may be experiencing isolation should be considered. Support organisations can play an important role for more isolated claimants and should be part of future signposting activity. That said, it should not be assumed that claimants who report stronger support networks do not need health support, as this may inadvertently place unfair pressures on those providing that support (family, friends, etc.)

- future health support should consider the appropriateness of directing claimants to support beyond NHS services. There may be a potential benefit of providing claimants with signposting information about general health resources and support organisations beyond the NHS. For example, locally available free talking therapies

- further research would be beneficial for understanding how best to use conversational settings as a route through which to deliver future health support. The positive impact of face-to-face contact with frontline staff during the claims process has emerged as a notable finding in this research, and warrants further exploration as a way in which to offer health support

- to enhance trust in future health support promoted by the Department, the offer of support needs to be framed appropriately. To foster trust and confidence in the health support offering, communications should make clear that engagement with DWP health support is voluntary, and that failure to take support up will not impact claimants’ benefit claims. The emphasis participants place on attaining financial stability as a motivator for applying for benefits (over and above getting back into the job market) should also be borne in mind when thinking about how to frame and present health support signposting to claimants

1. Introduction

1.1 Overview

This report presents findings from an in-depth qualitative research study with claimants applying for or receiving a range of health and disability benefits about their experiences of accessing health support. Specifically, it has looked to understand the views of claimants of Personal Independence Payment (PIP), New Style Employment and Support Allowance (NS ESA), and Universal Credit Health Journey (UC). It provides the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) with insights to inform the design of health signposting and support to claimants in the future, as well as wider health and disability policy reform.

1.2 The context for this research

This research has been conducted as part of the research and evaluation activities being undertaken to inform the Health Transformation Programme (HTP). The HTP is modernising benefit services to vastly improve customer experience, build trust in the services and the decisions the Department takes, and create a more efficient service for taxpayers. The Programme is developing a new Health Assessment Service and transforming the Personal Independence Payment (PIP) service over the longer term[footnote 4].

The Programme’s key strategic outcomes are as follows:

- increased trust in services and decisions

- a more efficient service with reduced demand for health assessments

- increased take up of wider support and employment

- improved customer experience with shorter journey times

- transformed in-house data and IT infrastructure that is secure

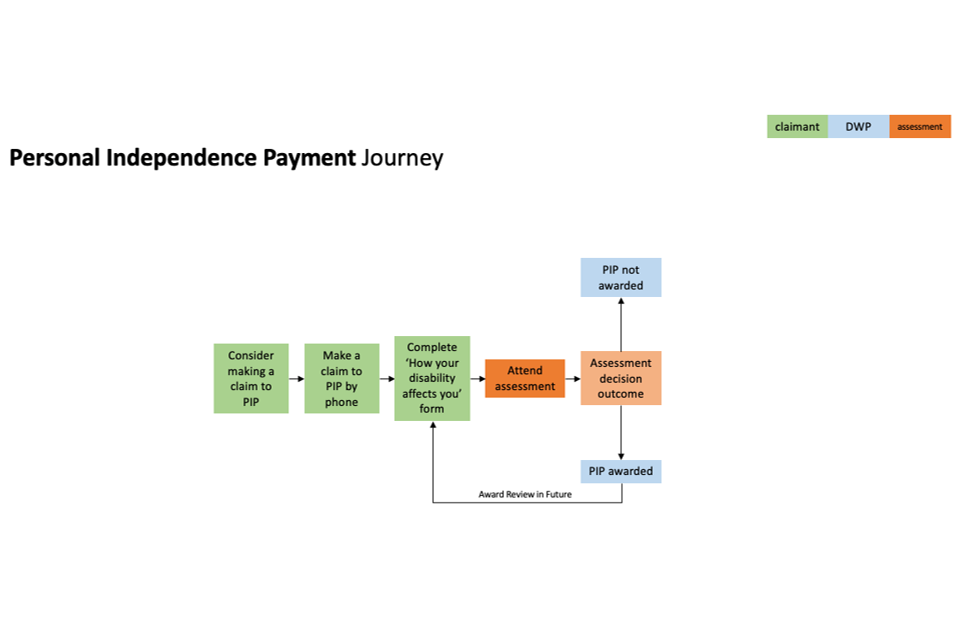

Of particular relevance to this research, the Programme is transforming the entire PIP service, from finding out about benefits and eligibility through to decisions and payments. The transformed PIP service will deliver a simpler application process for customers with more information and support available to those who need it, including helping them decide whether applying for PIP is right for them. Improved evidence gathering will also enable the Programme to better tailor the service to the customer’s circumstances. For example, they will only have a face-to-face assessment if this is the most appropriate method, and it may be unnecessary for the customer to have an assessment at all.

The programme is also creating a single new Health Assessment Service for all benefits that uses a functional health assessment. This will eventually replace the different services DWP and its assessment providers use to undertake health assessments across all benefits, including new IT and processes.

The Health Assessment Service will be fully integrated with other systems, including the transformed PIP service, to create a seamless customer experience. By improving how DWP gathers evidence and by enabling the reuse of information, the new integrated service will provide DWP agents and healthcare professionals with easier access to relevant information. This will reduce the burden on customers to provide complex information and reduce the need for them to provide it more than once.

In March 2023 DWP also published its Transforming Support: The Health and Disability White Paper[footnote 5]. This sets out in further detail proposals to improve the benefits process for people with disabilities and/or health conditions. Key proposals here include removing the Work Capability Assessment and offering more personalised support to claimants, testing an Enhanced Support Service for the most vulnerable claimants, and testing an Employment and Health Discussion.. Its content and recommendations touch on several findings uncovered through this research, which are reflected upon in the substantive chapters of this report.

1.3 Research objectives

Independent researchers, Basis Social, were commissioned to run an in-depth qualitative research study which aimed to understand more about the barriers that claimants with a disability and/or health conditions face in accessing health support. The participants in this research included a cross-section of PIP, NS ESA, and UC Health Journey claimants at different points in their journey. It also included four claimant appointees (those formally appointed to support claimants, such as family members) to understand potential needs from their point of view.

The aim of the research was to understand what role DWP could play in helping disability-related benefit claimants access health support. By improving health support to claimants, the hope is that DWP can help improve claimant Health Journeys, their quality of life and, where appropriate, move them closer to the labour market, specifically supporting the third of the HTP’s five strategic outcomes: that of “increased take-up of wider support and employment.”

The research aimed to explore the following key areas:

- what health support (clinical and non-clinical) do claimants have access to and use?

- what is the relationship between accessing and using health support and a claimant’s benefit journey?

- what health support do claimants on disability-related benefits feel would help improve their prospects of increasing their economic engagement?

- do claimants on disability-related benefits feel, and want, DWP to have a role in signposting to health support?

- would claimants trust DWP to support them with accessing health support (and would this lead to them trusting DWP in work-orientated conversations)?

In practice, pursuing these objectives has required an adaptable and flexible approach. The participants in this study, some of whom were highly vulnerable, have meant it has been important to adopt a practical, sensitive, and open line of questioning when delving into personal and potentially challenging subject matter. This approach is reflected in the main findings of the report. For instance, some participants found it challenging to describe what health support they needed from DWP. This could be because their medical needs were very specific, and they required targeted medical support. Additionally, some participants found it difficult to explain how DWP could best support them, especially given the relative complexity of the claims journey being discussed.

The report is organised to focus on the most important findings that help answer the main objective: understanding how DWP can assist people receiving disability-related benefits in accessing health support in the future.

1.4 Methodology

In-depth interviews were chosen as the best method for investigating claimants’ access to and engagement with health support, as they allowed for a detailed exploration of experiences, perceptions and attitudes, and a better understanding of contextual constraints. One-on-one interviews have also enabled sensitive handling of the subject, ensuring claimants’ voices have been heard and their perspectives fully understood.

Between December 2022 and March 2023, a total of 76 interviews were conducted. The participants were carefully chosen to ensure a diverse representation of individuals claiming PIP, NS ESA, and UC Health Journey. Additionally, the selection aimed to include participants at various stages of their engagement with DWP support, reflecting different points in their support ‘journey’. This involved conducting interviews with individuals at different stages of the process, including those who had not yet undergone assessment, those currently undergoing assessment, and participants who had already completed their assessments (see Appendix 1 for further details). The aim was to examine claimants’ experiences at various stages of their claims journey to gain a detailed understanding of potential support opportunities associated with each stage. As the researchers went on to discover, participants often struggled to identify their precise stage in this claimant journey, which has meant this aspect has been more challenging to investigate and call out during the research.

Qualitative sample design: an overview of the interviews achieved and with whom

The sample was a good mix of pre-assessment, assessment, post-assessment (and demographics) per claimant group

| Number of interviews | |

|---|---|

| Personal Independence Payment only | 30 |

| Universal Credit only | 21 |

| New Style Employment and Support Allowance only | 20 |

| Universal Credit and Personal Independence Payment | 5 |

| Total research sample | 76 |

Figure 1: Qualitative sample design

Whilst no ‘hard quotas’ were set for ethnicity, gender, and location, these factors were closely monitored during the recruitment process to ensure that a diverse range of profiles was included in the study. A breakdown of the final achieved quotas, including monitored quotas, can be found in Appendix 2.

To obtain a comprehensive understanding of the support requirements of all claimant groups, the final achieved interviews included four appointees (three for UC and one for PIP). As people formally appointed to support claimants, such as family members, this was an important viewpoint to capture.

The research team would suggest that this approach has allowed them to reach saturation point[footnote 6] This is the point in qualitative data collection when no additional issues or insights are identifiable. Repetition of themes in qualitative data signifies that an adequate sample size is reached and that further interviews across the various claimant groups is unlikely to have elicited any further insights.

Basis Social was provided with a claimant sample by DWP. To ensure the secure handling and management of data, best practice guidelines in accordance with GSR were followed. Within each quota cell, participants were randomly selected to approach for interviews from eligible batches of the sample, using the profile data available in DWP records. Most participants were contacted via post; however, email was used where an email address was on DWP records.

Telephone calls were then conducted to verbally screen participants and arrange an interview, ensuring overall quotas were achieved as far as possible. The approach taken to screening was based on disability research best practices, ensuring participation from claimants with diverse experiences. This approach enabled the researchers to accurately identify and include a wide range of claimants (based on demographic profiles and health conditions), ensuring their perspectives were fully represented. It also enabled them to check against the information provided about individual claimants in the DWP supplied sample, so the team could feel confident in who they were speaking to.

Participants were also screened to assess how their health condition impacted their daily lives. Their responses were then coded into three disability categories: ‘sense differently’ (e.g. visual impairments or hearing loss), ‘move differently’ (e.g. mobility or dexterity conditions), and ‘think differently’ (e.g. neurodivergent or mental health conditions). The disabilities and/or health conditions of the participants spoken to were complex and multifaceted, often involving comorbidity. These factors influenced their attitudes and behaviours regarding accessing health support and navigating the DWP claims journey. As a result, the reporting has focused less on describing these subjective sense categories in detail (focusing instead on the conditions in question).

The 76 participants encountered in this research experienced over 100 different conditions, with support needs as diverse as mobility differences, speech limitations, addiction, paranoia, and agoraphobia. Many participants had multiple conditions, which made their health needs more complicated. Additionally, the sample included individuals with medically complex conditions, as identified by the NHS or their healthcare providers. These conditions had a significant and long-term impact on their wellbeing, requiring substantial support. A more detailed breakdown of the range of disabilities and health conditions experienced by participants in this research can be found in Appendix 3.

In designing the research, careful consideration was given to the standard ethical guidelines for social research in government. It was acknowledged that some participants may find the topic of health in relation to their benefit status difficult to discuss. To mitigate stress, anxiety, and harm Basis Social adopted a communication and screening approach that made it clear to participants that the research was not connected to their DWP claim. All participants received materials in advance that provided detailed information about the nature of the research and that it was voluntary. The team ensured that participants felt comfortable discussing their experiences while understanding their rights and the guarantee of anonymity. Participants were also offered further signposting to health support after the interview. This approach aimed to create a safe and supportive environment, fostering trust and respect throughout the research process.

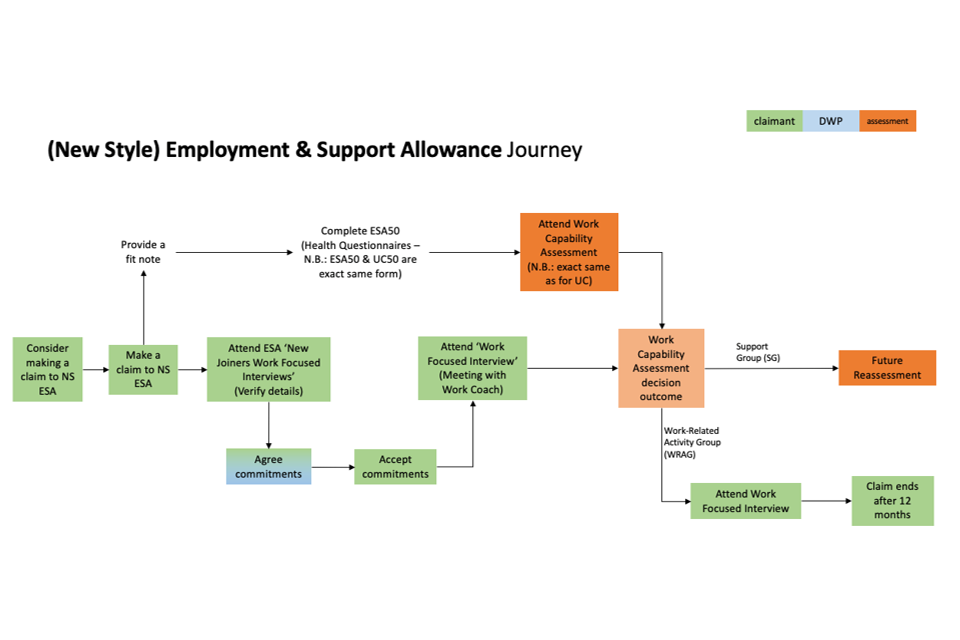

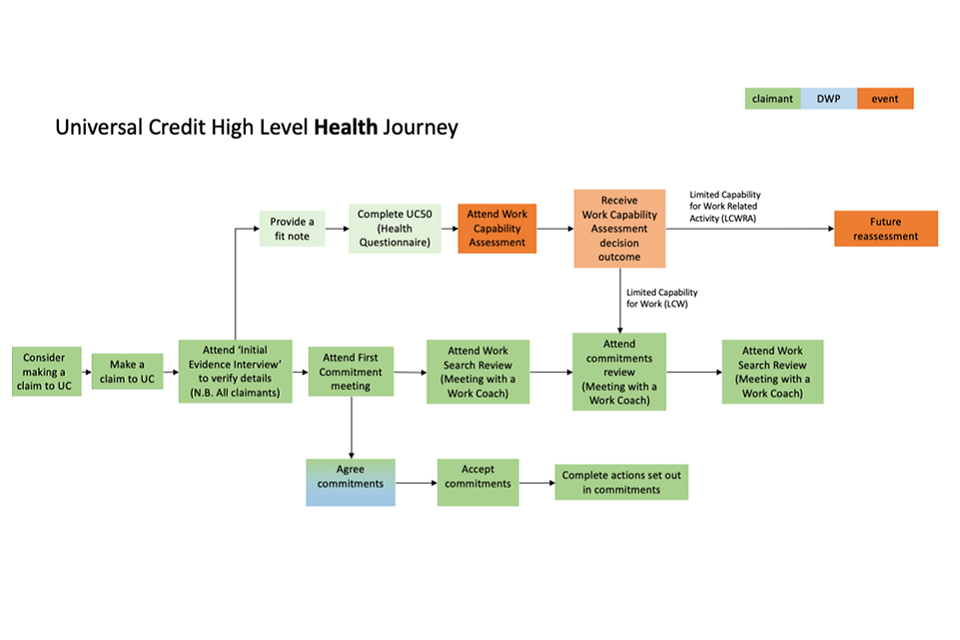

A standardised topic guide was created for use with participants from all benefit groups (see Appendix 4). To help them articulate their own benefit journey, participants were shown a range of exemplar benefit journeys that matched different pathways for PIP, NS ESA, and UC Health Journey claims, though it is worth stressing this was only limited to those conducting the interviews online (see Appendix 1). As noted previously, this made conversations related to the claims journey, including what this might mean for health support and signposting, more challenging since the researchers were unable to use these visual prompts.

Basis Social partnered with inclusive research experts, Open Inclusion, to develop the research and consent materials to ensure the lines of questioning were trauma informed[footnote 7].

Interviews lasted up to 60 minutes, building in flexibility for longer or shorter interviews depending on individual ability. Interviews were carried out online via Microsoft Teams or over the telephone, depending on participant preference (many participants did not have a working email address and/or were less comfortable using digital technology). Out of the total 76 interviews, 23 were conducted via Microsoft Teams, while 53 were conducted via telephone. All participants were given the option of having an advocate or appointee present for their interview, which a number took up[footnote 8]. To encourage participation, interviewees were provided with a £40 Love to Shop voucher as a thank you for giving their time to take part in the research.

The research team employed framework analysis, a common method in qualitative research, to structure and analyse the resulting data. This involved developing a thematic framework or coding scheme based on the research objectives and evolved lines of questioning, and the data itself. Relevant data segments were systematically coded and organised in matrices to facilitate comparison and synthesis. Through analysis and interpretation, patterns and relationships were identified, leading to well-supported conclusions. Framework analysis provides a structured and transparent approach to qualitative data analysis, enabling a systematic exploration of the research topic across diverse data sources and participant profiles. This was supplemented by regular brainstorms with members of the field team to identify and sense check the core themes emerging.

1.5 A note on interpretation

It is important to note that qualitative research is designed to be illustrative, detailed, and exploratory. It offers insights into the perceptions, feelings, and behaviours of people rather than quantifiable conclusions from a statistically representative sample. This has been reflected in the evidence presented in this report.

Verbatim quotes have been used throughout this report to help to illustrate points made in the main narrative. These have been labelled according to the disability and/or health conditions included in the supplied claimant sample and supplemented with any additional conditions that it emerged participants had during interviews (and which may or may not have been formally captured as part of their claim). This has been important to demonstrating the range and complexity of participants’ conditions. Also included are several short ‘pen portraits’, drawing anonymously on the individual participants spoken to, which have been designed to help bring the findings to life.

The research approach was designed to see if and how views and experiences differed according to the type of benefit individuals were claiming. Through this research it has been challenging to consistently draw out distinctions between benefit types – there has been significant consistency in terms of experiences, though the researchers have aimed to draw out difference where they can be confident doing so. There are a variety of reasons for this. First, it became apparent during interviews that the severity of a participant’s disability and/or health conditions did not always align with the specific type of benefit they were claiming, likely due to other influences at play such as financial status. Second, participants clearly varied in their understanding of the benefits system, which is likely to have been influencing their choice of benefit.

A note on language: Throughout the writing of this report, the research team has been acutely aware of the sensitivity surrounding discussions on health and disability. Linguistically, this is an area where best practices are constantly evolving. Open Inclusion has reviewed the language used in this report to ensure that it is suitably sensitive and free of stigma. The report also aims to reflect as best as possible the sorts of language and tone employed by participants themselves in discussing their specific disabilities and/or health conditions. All quotations used are verbatim, taken from interview transcripts and detailed moderator notes.

1.6 Report structure

This report is divided into four main chapters that address the project’s core research objectives, followed by a set of conclusions.

- Chapter 2 focuses on understanding how participants manage their health and the support they currently use. It looks at various factors that influence their approach to health and identifies any gaps in support based on their views

- Chapter 3 provides more detailed information on the health support available to participants and what drives them to use or not use it. It also explores the barriers they face in accessing this support currently

- Chapter 4 examines the connection between using health support and a participant’s journey through the benefits system. It explores if there are specific moments or ways support could be provided to them effectively

- Chapter 5 captures the opinions of participants about receiving health support as part of their benefits journey. It looks at the role DWP might play and about levels of trust in DWP offering this kind of support

- Chapter 6 summarises the main learnings from the research and the key factors to consider in providing health support going forward

2. How claimants experience and manage their health

This chapter explores the contextual factors influencing participants’ perceptions and management of their health, as well as the challenges posed by specific disabilities and health conditions. It provides insights into participants’ access to and need for health support, including their awareness, interest, and preferred types of support. The findings underscore the complex and personal nature of claimants’ health needs. Additionally, it highlights that when referring claimants with complex needs to health support, consideration should be given to involving specialists in the design and delivery. Furthermore, there is an apparent unmet need for mental health support among claimants and their appointees.

2.1 Multiple factors affect claimant health management

Participants, regardless of their specific disability and/or health conditions, or the type of benefit they had applied for, consistently highlighted to the researchers the highly personal and individualistic nature of their disability and/or health conditions. The unique aspects of their situation strongly influenced how they coped with their condition, their ability to identify relevant health support, and their willingness to access it. Participants commonly emphasised to the research team the importance of considering a variety of personal and contextual factors related to their experience and situation which they felt were key to understanding how they managed their disability and/or health conditions.

For some participants, the very nature of their condition was described as making health management challenging. For instance, they described their medical conditions’ symptoms as highly unpredictable and difficult to anticipate, with varying levels of intensity over time. To provide an illustration, the researchers received accounts from individuals with conditions such as myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) who emphasised that while they could manage certain basic tasks independently through energy planning and conservation, flare-ups in their condition or unexpected disruptions to their routine occasionally necessitated significant additional support, which was challenging to predict. Meanwhile, participants with degenerative conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease and osteoarthritis described experiencing highly personal changes to their physical and cognitive abilities.

Other participants in this research described being given specific medications as part of their treatment which exacerbated their existing symptoms in a way they felt was not commonly associated with the primary condition they were receiving treatment for. For example, one participant described how statins for a heart condition had on occasion impacted their memory. Another claimant with alcohol dependency described how this made them more prone to infection which impacted their management of bladder disease.

Participants who encountered personal challenges unrelated to their disability and/or health conditions often expressed difficulties in managing their health. To illustrate, claimants who faced literacy issues, language barriers, or difficulties in using and accessing digital technology described how these challenges affected their ability to identify and access relevant support. For example, by impacting their ability to proactively access information or communicate with medical experts online. Other participants highlighted broader environmental challenges, such as living in unmodifiable properties or areas with limited or inaccessible health services.

A number of participants in this project were also at pains to emphasise the role their own personality and life philosophy played in managing their disability and/or health conditions. This included life experiences which had required them to develop highly personal strategies to cope with the world. For example, highly negative experiences might have encouraged them to avoid strangers of a particular gender, or to conceal vulnerability from others. For others, this meant having a strong set of personal ‘rules’ surrounding their health management, such as a desire for autonomy or independence (“I can’t rely on others, so I need to rely on myself” – UC claimant, heart and kidney condition). These ‘rules’ influenced the types of support individuals went on to describe as feeling appropriate for their disability and/or health conditions, and when they felt this support would be best needed.

Case study 1: Meet Roy. Roy has had a difficult past, serving in the army and after this experiencing periods of homelessness. As a result, he highly values his independence and believes that seeking care is a sign of weakness. Prior to his heart attack, he served as a caregiver for a neighbour. However, he rejects the idea of being a care recipient himself and sees himself as someone who helps others, not someone who needs help. This mindset caused him to initially resist having home visits from a heart failure nurse after his release from hospital, until one day he fainted in the street, and it was clear he could no longer cope on his own. Due to his aversion to seeking help, he keeps his struggles hidden from his friends and family.

Whilst it is important to note that a small number of participants did not necessarily overtly call out the uniqueness of their disability and/or health conditions, this was typically because of their uncertainty about how their condition or situation compared to others. However, when describing how their condition affected their lives, it was apparent to the researchers that these participants still shared highly personal challenges that they believed were crucial to consider for effective condition management.

It is clear from speaking to participants that the factors that shape an individual’s relationship with their health and health management, as well as the symptoms they need to manage, are highly personal, varied, and will depend on their specific circumstances. This strongly points to the need for a more personalised approach to health support and signposting. And to ensure successful uptake of such support, it is necessary to fully understand and consider the broad range of factors at play.

2.2 Disabilities and health conditions can be complex and severe

Understanding claimant health needs and their barriers to accessing support is made more complex by the sheer variety of conditions which can lead people to claim disability benefits, as was very evident from the participants spoken to. Across this project’s 76 participants, participants described experiencing over 100 distinct conditions (see Appendix 3 for a list of the conditions encountered), with support needs as diverse as mobility differences, speech limitations, addiction, paranoia, and agoraphobia). It was common for participants to also experience more than one condition, which increased the complexity of their health needs.

Additionally, the sample included participants who described having conditions which are formally classed by the NHS or their healthcare provider as ‘medically complex’[footnote 9], meaning they have a substantial impact on their wellbeing that require significant and often long-term support. Examples here included individuals with schizophrenia (who may sometimes struggle to distinguish their thoughts and ideas from reality), participants with severe learning difficulties (introducing at times some challenges understanding complex information), and individuals with life-limiting conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and cystic fibrosis (limiting their movement and breathing).

Claimants with severe conditions expressed that the scale of their health challenges would mean they would need a more sensitive approach when it came to identifying and accessing health support. They emphasised that even basic changes to how they managed their health should be made in consultation with a medical expert who would be best placed to understand the degree or risk involved. Following ‘generic’ or ‘off-the-shelf’ advice and guidance which might be offered through the claimant journey had the potential to risk causing harm for these participants since it was not rooted in a nuanced understanding of their condition. This concern was particularly pertinent for participants with multiple health conditions. They expressed concern about whether an intervention targeting one aspect of their health could end up adversely impacting or complicating another comorbid condition they had. Participants with a disability and/or health conditions which they themselves considered complex or sensitive were clear that they would not want to make substantial changes to their health management without medical advice.

Whilst support is always nice, there’s also the concern in the back of your mind that it might not be right for you or [DWP may not] have fully understood your condition. Well-meaning suggestions could in fact make matters worse which would be the worst outcome of all.

(PIP claimant, bladder cancer and lupus)

The big question I have with health advice is always whether this will be right for me. You’d want to check with a doctor to be safe.

(UC claimant, anxiety and depression)

The wide range of disabilities and health conditions experienced by claimants, and the complex ways in which these can intersect, suggests that extra care will need to be taken when considering the health support needs of those with more complex need. This might include the need to engage specialists in the design and delivery of health support for claimants with these more complex conditions and/or needs.

2.3 Life challenges can worsen conditions

For some participants, the need for benefits was described as accompanying significant periods of disruption in their lives. Participants explained that when navigating these periods of volatility, it often shifted their focus away from health management, resulting in less optimal care practices and challenges in establishing healthy routines. Among our sample, these challenges were more commonly reported by participants in the UC Health Journey group compared to other benefit groups.

Case study 2: Meet Linda. Linda, a claimant on Universal Credit, used to work as a cleaner at her local hospital, but had to give up her job due to the impact of Long Covid and a heart condition. The loss of her income has made it difficult for her to afford the rent, so Linda has spent the past month searching for new housing. She describes the entire process as stressful and overwhelming. The fear of eviction, combined with the physical energy required to view properties, has worsened her symptoms. Linda does not feel like she can focus on her health and rest until this issue is resolved. Since she does not live in council housing, she does not think there is anyone she can speak to about her situation and describes feeling alone.

Researchers also heard from several claimants with substantial caring responsibilities – on top of managing their own health conditions they were caring for others, some of whom also had a disability and/or health conditions. The pressure and exhaustion involved in managing this alongside their own health made it hard to plan effectively or put their own needs first.

Case study 3: Meet Adam. Adam is a PIP claimant who has recently suffered a spinal injury that has forced him to reduce his work hours. This has left him feeling financially stressed, especially with two autistic children who require a lot of support. He is worried about his ability to physically care for them and feels guilty for putting his own needs first. The lack of support for childcare and the need to advocate for his children’s needs is taking a toll on his mental and physical health. Adam currently relies on his mum to help with childcare when she can but knows this is not sustainable. Currently he feels too overwhelmed with his day-to-day responsibilities to find the time to contact health services. Getting more help with childcare would allow him to focus more on his own health management.

Claimants who faced such disruptive life events typically thought that targeted support aimed at reducing stress, such as housing assistance, counselling, and aid with administrative tasks, would be beneficial. This support was expected to help provide the necessary ‘headspace’ to focus on their own health and wellbeing.

However, unless they were already connected to third sector support organisations, many of these claimants faced challenges in identifying the appropriate channels to access such support. Those participants who actively engaged with support often mentioned relying on assistance from friends, family, or pre-existing relationships with support organisations established during previous stages of their lives. They also described receiving signposting from other services they were in contact with, for example, social services.

Another source of disruption and instability participants described, was deteriorating health conditions. In these cases, it was apparent that participants found it challenging to develop effective coping strategies, namely because they did not have enough time or opportunity to experiment with different lifestyle adaptations before their condition changed. Participants here described how the changing nature of progressive illnesses could make it hard to predict how a condition might be experienced in the future, making long-term accommodations more difficult to plan for. Whilst some described managing their condition well – typically those with robust support networks and good access to local health services – others reported difficulty in getting access to regular support conversations, including from the NHS, as their condition changed. As such, this group was open to the kind of health support and signposting which might help them better understand how their condition is likely to progress, and what this means for how they can plan for future health management.

The influence of broader life challenges on health management, and the extent to which claimants currently utilise services to address these challenges, indicates a potential benefit to claimants in signposting to wider support services where relevant.

2.4 Poor mental health is common, but not always formally recognised

Poor mental health can complicate the management of an individual’s disability and/or health conditions. In discussions with participants, the topic of poor mental health frequently came up without any prompting, although this was by no means the case for all participants. Spontaneous discussion of mental health was less common among those who had strong support networks and established care routines. However, some participants who described experiencing social isolation felt this exacerbated their symptoms. Other participants who had limited connections to family and friends felt this made it harder to manage their mental health and establish consistent care practices.

Some participants who were facing mental health issues had received formal diagnoses and treatment for conditions such as depression and anxiety. However, others had not received a formal diagnosis or treatment. Within this group, some shared their experiences of reaching out to their GP for support but had faced challenges with long waiting lists. Others admitted that they had not sought medical assistance due to the overwhelming demands of managing their primary health conditions, which left them with little energy or motivation to address their mental wellbeing.

The researchers also heard from participants who found it difficult to express their mental health challenges using medical terms, but who nonetheless were clearly struggling (describing periods of feeling low and hopeless, for example).

Some participants described how the deterioration of their physical health linked to their disability/health condition had led to anxiety. For example, one PIP claimant with Parkinson’s disease explained how they felt they were losing control and expressed concerns about how their condition was affecting those around them. Specifically, they worried about the increased burden placed on their loved ones, who had to take care of them.

I think about the future, and it all seems to be bleak. I just sit on my bed and cry.

(PIP claimant, Parkinson’s disease)

For others, deteriorating health was described as leading to a loss of identity. One NS ESA claimant who had left employment due to back pain and mobility issues, reported that they felt they had lost their ‘purpose in life’. Others who had left employment due to their deteriorating health described how a lack of day-to-day structure was now causing them low mood.

My whole life has been dedicated to my job. Now I have nothing.

(NS ESA claimant, chronic back pain)

Shame was a sentiment expressed by those who were used to “paying into the system” (NS ESA claimant, depression). For them, claiming benefits was interpreted as a loss of pride and status.

It makes me feel down that I’m reduced to this. It makes me feel small.

(UC claimant, rheumatoid arthritis)

Another way poor mental health manifested was because of participants feeling less able to participate in social activities, in turn leading to isolation. One PIP claimant explained that they avoided going out for fear of having a manic episode in public. We also heard examples of how medications claimants took could cause embarrassing side effects, such as sweating, flatulence, involuntary urination, brain fog, and fatigue.

I take a pain medication for my back which is a relaxant. This means I can sometimes soil myself. I’ve lost all my confidence and don’t want to go outside.

(PIP claimant, chronic pain and depression)

During interviews, it was not unusual for claimants to discuss their mental health in a way that indicated it was being ‘normalised’, and just part of their daily life. When asked if they had informed DWP about their mental health conditions, or had discussed it at their Health Assessment, several participants explained they were more focused on telling DWP about their physical conditions, since they understood this to be the Department’s primary concern. Others could not remember if they had brought up mental health at all.

Several claimants within our sample mentioned that the deterioration of their mental health occurred to such an extent it became the main challenge for them ahead of the original health condition which motivated them to apply for benefits in the first place. To cope with their circumstances, the researchers heard a small number of instances where participants were adopting behaviours they felt shameful of, including substance abuse. This in turn made it hard to convey the full extent of their health concerns to DWP.

At the start the main issue was my eyesight but now I would say it’s the drinking and the loneliness. That’s the first thing I need help with.

(PIP claimant, macular degeneration and alcohol dependency)

The idea of receiving support with their mental health was received positively by participants in the main. For those with less interest, this was more down to a desire to manage their own health independently without the involvement of a non-NHS organisation. But, again, participants here wanted to know that any support would account for their unique circumstances, including the disability and/or physical health conditions they are living with. In short, it was important mental health support aligned with their wider health management needs.

A lot of mental health support out there wants you to increase your exercise or talks about getting out in the world, which for me isn’t going to work. I barely have enough energy to get out of bed.

(PIP claimant, Scheuermann’s disease)

The repeated mention of mental health challenges among participants, and the observed lack of understanding in managing them, indicate a potential role for future health support to provide mental health signposting. Increasing awareness and take-up of mental health support is likely to make a substantial difference in motivating claimants to seek wider health support. Furthermore, these findings suggest the important role wider health support could play in preventing the deterioration of health conditions and thus the onset of poor mental health in the first place. Support needs to be cognisant, however, that mental health challenges can result in behaviours that are embarrassing for the claimant and which they may not wish to disclose. For example, the use of alcohol or illegal substances to manage low mood. When developing future support, the Department may wish to involve medical experts who can adapt solutions based on the needs of claimants with more complex conditions and communicate this clearly to claimants by way of reassurance.

2.5 Appointees’ mental health can suffer too

In seeking to understand health support needs, the research has also shown that mental health issues can occur among appointees too. Whilst the researchers only spoke to four appointees through this research, amongst this group all described challenges to their own mental health and wellbeing in supporting the person they acted on behalf of. This is relevant because it appears to be having an impact on the functioning of the claims process itself. The researchers heard examples of appointees struggling with poor memory or lack of concentration causing errors in paperwork. Lack of energy had caused challenges in securing key documentation in a timely manner, slowing down the claims process. One appointee described how depression had reduced their ability to perform care behaviours or advocate for health support on behalf of the claimant they represented.

These appointees would welcome support from DWP that helped them with their own wellbeing and health management, which in turn could benefit those they are caring for.

Case study 4: Meet Claire. She is a busy mother of three children and acts as an appointee for her 16-year-old son, Josh, who requires round-the-clock care due to a rare genetic disorder. She describes her life as grueling and exhausting. Due to Josh’s night seizures, Claire rarely gets any sleep and spends most of her waking hours managing his care or advocating for support from medical professionals. She describes experiencing periods of very low mood, which can be debilitating and, at their worst, impair her ability to care for her son including dealing with his paperwork. She identifies isolation as the biggest challenge she faces, as she is effectively confined to her home. She strongly believes that DWP should provide more support for appointees and would welcome assistance that helps her connect with other adults or provides signposting to organisations that could offer help. The pressure of her caring responsibilities means she has no time for health research herself.

To ensure effective advocacy for claimants, it may be beneficial for DWP to also offer support and signposting to appointees, particularly in relation to mental health and wellbeing.

2.6 Summing up

In this chapter, the report has explored the factors that influence how claimants perceive and manage their health and what this means for potential health support and signposting. It has found the following:

- the factors that shape an individual’s relationship with their health and health management, as well as the symptoms they need to manage, are highly personal and varied. This points to the need for a more personalised approach to health support and signposting

- given the potential risks identified by participants in signposting claimants with more complex needs to health support, any support offer should consider the extent to which specialists should be engaged in the delivery and/or design of support

- given what we have heard about broader life challenges in health management, there appears to be a role for offering signposting to wider support services where relevant (housing support, counselling, and help with administrative tasks, etc.)

- the repeated mention of mental health challenges among participants (and appointees), and the observed struggles in managing them, suggests mental health support and signposting will be important to consider as part of any future support offer

3. Access and engagement with health support

This chapter explores the factors influencing the availability and accessibility of health support for claimants, as well as the factors shaping these interactions. We have found that the strength of a claimant’s social network significantly impacts their ability to manage their disability and/or health conditions. Claimants who were more isolated with weaker social ties struggled more with their health condition. Some participants felt current pressures on the NHS were impacting their ability to access timely and high-quality treatment, while organising care beyond the NHS could be seen as challenging. Charities and support organisations play a crucial role in providing health management support for those participants who were aware of them. This again underlines the potential benefits of a strong social network to good health management.

3.1 Social connections impact how claimants access health support

When comparing participants who appear to be effectively managing their health to those who are not, the presence of strong social and support networks was identified by the research team during the analysis as a critical differentiating factor. Participants who had a reliable support system consisting of friends and family described more successful management of their disability and/or health conditions compared to those who lacked close relationships. Some participants explicitly mentioned the importance of their support networks, while in other cases, the research team inferred its significance from their descriptions of care practices and health management behaviours.

There were several key factors which participants attributed here.

First, participants reported that family and friends were often in the best position to recognise any changes in their health status. The individuals surrounding the claimant can detect and proactively suggest extra support needs early, before an individual’s condition deteriorates (and where the individual may not recognise they need support themselves).

After I first got diagnosed, I was working too many hours and really struggling. My husband took me aside and said you can’t go on like this, you look terrible, we need to make some big changes at home.

(NS ESA claimant, back pain and leg ulcer)

Secondly, many friends and family members were described as actively meeting claimants’ support needs themselves, often with significant self-sacrifice and expense (a fact mentioned by both claimants and appointees). Support can vary from personal care, such as washing and dressing, to managing household affairs, and from providing transportation to offering financial assistance to access privately funded care.

Case study 5: Meet Ken. Ken is a recipient of Universal Credit (UC) and Personal Independence Payment (PIP) due to his heart and kidney condition. Following a recent health scare that required hospitalisation, his youngest son, Patrick, decided to move back in to provide monitoring and support for his father’s condition. The specific tasks Patrick assists with vary from day to day, depending on Ken’s wellbeing. They include shopping, gardening, running errands, picking up medication, and taking Ken to a local social club. Although Ken feels guilty that Patrick invests so much time in his care, he finds it difficult to envision how he would manage such flexible support without his son’s help.

It is noted earlier in section 2.5 the pressure and stress that providing this support to claimants can have on those providing care, specifically for those appointees spoken to through the research. Whilst not the target audience for health support, this is relevant for DWP to consider given the potential impacts here.

Family and friends were reported to help broaden participants’ horizons by sharing new information, including treatment options and health management tips. Their role here was described as particularly important by participants who face mobility or mental health challenges which can limit their interaction with the outside world.

When my sister visits, she also shares ideas I can try. For example, sitting on a stool when I cook.

(UC and PIP claimant, arthritis)

Other interviewees described how receiving support from family and friends also eased the burden of engaging with health services and advocating on behalf of the claimant – for example, questioning treatment plans and pressing for additional support.

It’s been a struggle to get the NHS to take this serious[ly] and get my therapy, but mum has been with me all the way, on the phone, really pushing.

(UC claimant, depression and ADHD)

Importantly, participants with solid support networks often described how the love and care of friends and family had helped to boost their mental health during difficult periods. This increased their motivation to problem solve, ask for help, or experiment with new care practices.

My family are keeping me sane and encourage me to keep going and look for new solutions.

(UC claimant, anxiety and diabetes)

In stark contrast, participants with weaker social connections described less successful health management. While some explicitly mentioned the detrimental effect of social isolation on their health, the impact of poor social networks could also be inferred when considering the challenges this group was facing in accessing care they might need.

For example, the researchers heard from participants who described how they struggled with performing self-care behaviours at home, such as washing, dressing, or eating. This then impacted their energy levels and their ability to dedicate time to positive health management behaviours.

It takes me hours to get ready in the morning. Even putting on a shirt in the morning takes my breath away. All I can do is sit on the bed and wait until I have more energy. My son used to help with this when he lived here.

(UC claimant, angina and chronic pain)

Other participants described difficulties in leaving the house on their own, which would impact their ability to access healthcare resources and care options. This was attributed to factors such as mobility issues or limited transportation options (e.g. inability to drive or limited access to public transport) but was also an issue for those with social anxiety or mental health conditions.

For this group, social isolation was described as having a negative impact on their mental health. They reported symptoms such as low mood, decreased energy levels, and an increased sense of helplessness. These factors were explained as combining to decrease their ability to connect with healthcare services or support organisations which may help manage their condition. Low mood was also described as decreasing their motivation to find ways around these barriers.

I am very ready and desperate for any kind of support. If I had someone to speak to, even a cat, I think I would be coping with it all so much better. I might feel more positive.

(PIP and UC claimant, eye melanoma)