Annual report on the operation of the UK internal market 2023 to 2024

Published 20 March 2024

OIM Panel Chair’s foreword

I am pleased to present the OIM’s second annual report, covering developments in the UK internal market from April 2023 to March 2024.

I am particularly delighted to welcome the appointment of the OIM Panel, to join our work in considering the effective operation of trade between the UK nations. The Panel members have a wealth of experience from across the UK and I very much look forward to working with them. Appointment of the Panel coincided with the development of this report, and we are grateful for their input and insight into our statutory reporting.

In my foreword to last year’s report, I noted the importance of gathering evidence from a wide range of stakeholders to inform our work. Over the past year, the OIM has implemented a regular programme of bilateral and multilateral meetings, to strengthen our relationships with officials in the four governments. I continue to be impressed with the constructive and collaborative approach of officials in the governments and their generosity in providing information and participating in discussions. We remain committed to supporting decision making in the governments with even-handed advice and insight. We look forward to completing further reports for the governments at their request in due course.

Also notable this year is the OIM’s engagement with the legislatures. In June 2023, I was pleased to be invited to give evidence on the OIM’s work to the Legislation, Justice and Constitution Committee of the Senedd Cymru. This was followed in September by an evidence session on the OIM’s first annual report with the Constitution, Europe, External Affairs and Culture Committee of the Scottish Parliament. Most recently, we provided written evidence on the OIM’s remit to the House of Lords Sub-Committee on the Windsor Framework. In June 2023, OIM officials provided an informal in-person briefing to Northern Ireland Assembly Members, and separately briefed Northern Ireland Assembly staff. The OIM is grateful for opportunities to engage with the four legislatures and stands ready to assist with their work.

This report reflects the continued evolution of our thinking in relation to the effective operation of the UK internal market. Alongside our engagement with the governments and legislatures, I have engaged extensively with business groups across the UK. In 2023, I held in-person meetings with business groups in Northern Ireland in January and September, in Wales in March, and Scotland in June. We are also grateful to the many businesses and trade bodies who contributed to the evidence presented in this report. This helpful and open approach by businesses is particularly reflected in the business strategy case studies included in the report. These examine responses to four areas of significant current and emerging regulatory difference between the nations.

Our focus on stakeholder engagement has assisted us to develop our statutory reporting. We noted in last year’s report the emphasis on regulatory developments in relation to goods and the relative lack of change in relation to services sectors or regulated professions. This report includes expanded analysis of both of these areas, to broaden the scope of our work to understand the impacts of the UK Internal Market Act 2020.

Alongside last year’s reports we published our Data Strategy Road Map, setting out initiatives to improve intra-UK trade data. Through the year we have continued to engage with the Office for National Statistics, experts in the devolved nations, the academic community and colleagues working with trade data in other countries, to explore new sources of data and techniques to improve our analysis. We will publish an update to our Data Strategy Road Map in Spring 2024.

We will continue to develop our view of the factors that underpin the effective operation of the UK internal market and welcome feedback on this report.

I would like to extend my thanks to the staff at the OIM and in the wider CMA for their expert and informed work to develop this report and their ongoing support to ensure that the OIM Panel members can contribute effectively to our understanding of the UK internal market.

Murdoch MacLennan, Chair of the Office for the Internal Market Panel

Executive summary

This report is the Office for the Internal Market’s second annual report on the operation of the internal market. It covers the period from April 2023 to March 2024 and builds on our previous work.

Key findings

Drawing on the available data we find little evidence that, over the last year, there has been a substantial change in the functioning of the internal market across the UK. Notwithstanding this, certain sectors, especially food and drink, have seen a more significant build-up of proposed and actual regulatory difference than other sectors.

Trade between Great Britain and Northern Ireland will continue to develop in light of the Windsor Framework, although the nature of these developments remains unclear as the Framework was only partially implemented over the last year, and none of the available trade data covers the period it has been in operation. Furthermore, on 31 January 2024, the UK Government published a Command Paper, “Safeguarding the Union”, that make certain adjustments to the Windsor Framework. We will work with the governments to understand the implications of the Command Paper (and related Statutory Instruments) for our work.

Trade data

Chapter 2 of this report presents our updated analysis on the intra-UK trade data. The trends set out in the 2022 to 2023 annual report remain relatively stable. The internal market continues to be important to the UK nations. Our analysis of trade data produced by the devolved nations shows that intra-UK trade, in 2021, represented roughly between two-fifths and two-thirds of the external sales and purchases of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. Intra-UK trade remains less important for England because of the size of its economy relative to the other nations.

In our 2022 to 2023 annual report, we found that the majority of businesses that trade within the UK do not experience challenges when selling to other UK nations. This is still the case, with the majority of firms responding to the ONS Business Insights and Conditions Survey (BICS) saying that they have not encountered challenges with intra-UK trade.

BICS evidence indicates that businesses in the manufacturing and wholesale and retail trade sectors as well as larger businesses are generally more likely to trade with other UK nations.

In this year’s report, we make use of additional data from BICS and from HMRC, to better understand trade flows between Great Britain and Northern Ireland. BICS data suggests an average of 4.5% of businesses stated they had sent goods from Great Britain to Northern Ireland in the last 12 months. Although this is only a small proportion of all businesses, the value of the trade involved was more significant; the 2021 value of customs declarations associated with these trade flows represented around 24% of Northern Ireland’s GDP. BICS data also shows that less than 2% of businesses sent goods from Northern Ireland to Great Britain in the last 12 months.

We are required to report on the effective operation of the internal market. We noted in the 2022 to 2023 annual report that we use intra-UK trade data as a key indicator, to help understand how the market is working. Data on intra-UK trade remains limited and our analysis provides a comparative overview, using available sources. We remain committed to supporting better trade data, including through the initiatives in our data strategy roadmap. We expect estimates of intra-UK trade covering all four UK nations to be available by autumn 2024. We continue to explore other indicators and will publish an update to our data strategy roadmap later in spring 2024.

Regulatory developments in goods, services and the regulated professions

Chapter 3 considers regulatory developments over the preceding 12 months in relation to goods, services and regulated professions. Over the last year we have seen an increase in the number of potentially differing regulations compared with the previous year in relation to each of goods, services and the regulated professions. Over the last year, the goods sector has seen the most significant developments in regulatory difference within the scope of the UK internal market regime. The goods sector is proportionately more likely to see regulatory difference than the services sector and the regulated professions. This is reflected in a greater number of differing regulations than in services or in relation to regulated professions. Notwithstanding this, the impacts on the internal market of these changes remain modest, in part because of the decisions businesses have made regarding how they respond to differing regulations, which we explore in more detail in the case studies in this report.

Regulatory difference in relation to services is starting to emerge, though not to the same extent as in goods. It is too early to identify any clear internal market effects in relation to services. In particular, the localised provision of many services complicates an assessment of how regulatory difference might affect trade; differences that affect locally provided services and that are rarely traded cross-border are unlikely to have a substantial impact on the internal market. Despite these points, the much greater scale of the services sector means that there is, at least in principle, scope for regulatory difference in relation to services to be as important in terms of the value of the affected activities as regulatory difference in relation to goods.

There have been only a small number of differing regulations proposed over the previous year in relation to regulated professions; all arising through the creation of new regulated professions (as opposed to changes to the regulations governing currently regulated professions). The current proposals for new regulated professions largely concern professions with limited scope for cross-border trade. We conclude that there has been little change to the functioning of the internal market for professionals since the UK Internal Market Act took effect, and this does not appear likely to change in the near future, given the historically slow pace of regulatory change in the regulated professions.

Case studies of businesses’ adaptations to differing regulations

Chapter 4 presents business strategy case studies. These look at four areas where regulatory difference has occurred or may occur in the near future. The case studies examine the approaches that businesses have adopted in response to the differences. The four case studies are: bans on single use plastic (SUP) items, deposit return schemes (DRS), restrictions on the retail promotion of products high in fat, salt, or sugar (HFSS), and regulations relating to the use of precision breeding (PB) techniques. We have chosen these areas because of the degree of regulatory difference they are anticipated to create and because they provide a broad spread of regulations that affect different stages of the supply chain.

A notable finding from our case studies of SUP, PB and DRS is a clear view, particularly among the larger businesses in those sectors with significant operations in the devolved nations, that the Market Access Principles are unlikely to be used as the preferred approach to address regulatory differences. Businesses preferred other approaches including: adopting a high standard that is compliant across all nations where possible; having 2 supply chains (and perhaps reducing the number of product lines to manage the costs of this); and withdrawing from a particular nation. If businesses in other sectors and in relation to other regulations take a similar view, this potentially has significant implications for the internal market regime. We note, however, that we would need to examine this across a broader range of businesses, including SMEs, and a broader range of sectors before we could establish if this was a widespread effect.

We also observed that differing regulations that have effects earlier in the supply chain (such as PB and DRS) appear to be more challenging for businesses to address than differing regulations that have their effects later in the process (such as SUP and HFSS). This may be a helpful finding for policy makers who have some flexibility in how they intend to achieve a particular policy goal; some regulatory differences may have a much lower impact on businesses than others, even if the policy goals are broadly similar.

Linked to this is the high degree to which businesses aim for simplicity in their supply chains. Businesses spoke of adopting a highest common denominator approach (for example, a high standard that is compliant in every nation), often moving ahead of anticipated regulatory change. While this was partly in response to consumer expectations, it was also to ensure that any changes to products or distribution could be made on a timescale and in a way that worked with supply chain requirements. In general, businesses preferred not to tailor products to regulations in one nation, but to offer a product that was compliant everywhere across the UK. In this way, businesses could be said to take an active role in establishing regulatory norms.

We note in the case studies that a significant number of businesses identified range reduction as a possible consequence of regulatory difference, with the important observation that in some cases the reduction in range might occur in a nation not directly affected by the regulations in question. We think this is a credible response to the increased costs and complexity of duplicating product lines. However, none of the businesses we spoke with had yet made firm decisions about which items to withdraw from which markets. Products likely to be withdrawn will be low volume and may not account for much cross-border trade. There may be also strategic and brand-related reasons for keeping certain products available even if they are marginally profitable. Given the high level of uncertainty in these considerations, we conclude it likely that businesses would delay making decisions about product withdrawal until strictly necessary.

The place of the UK internal market within global supply chains will have a powerful bearing on business decisions arising from regulatory difference. For example, developments in the use of precision bred grains are likely to be shaped by policy and consumer sentiment in the EU and more widely, as well as by domestic considerations. Outcomes within the UK might need to adapt to international changes and/or accept the cost implications of diverging from international norms.

In gathering evidence for these case studies, we identified the important role of consumer preferences. Arguably, policy developments in relation to SUP and DRS have been introduced at a time when a significant body of consumer opinion understood and supported the policy objectives behind these initiatives (we also identified a similar situation in our study of Defra’s regulations banning the sale of horticultural peat products). In some areas, policy development may lag consumer attitudes. Consumer preferences influence the confidence businesses have in designing a response to regulatory developments, perhaps especially in taking the highest common denominator approach mentioned by stakeholders in the food and drink industry. By contrast, precision bred crops is, arguably, an area where there is not yet widespread consumer understanding or demand. The uncertainty this creates for businesses accentuates the difficulties of addressing regulatory difference. We are of the view that where regulatory difference emerges ahead of consumer acceptance, this is less likely to lead to a UK-wide response by businesses.

In developing this report, we have identified common themes in relation to differential regulation between the nations, which we hope will assist policymakers when considering the potential impacts of future regulatory change on the UK internal market. The case studies, in particular, indicate a number of ways in which policy makers might be able to adjust policy design in order to minimise internal market impacts. These include: considering designing differential regulations so that they permit a highest-common-denominator response, which will require coordination and cooperation between governments; paying close attention to the point in the supply chain that a regulation has its effects, as the closer to the final consumer that a regulation has its effects the easier difference may be to manage; and recognising that the effects of a differential regulation may arise outside of the nation into which it has been introduced, which is more likely when supply chains cross national borders.

Conclusion

The emerging picture of the internal market is that regulatory difference is starting to build up, albeit slowly and with goods affected more than services, especially in food and drink. However, businesses are adapting creatively to the new regulatory realities in ways that often preserve existing trade flows and supply chains. The relative strength of these forces is yet to become clear and policy makers can make choices that, even if they pursue differential regulation, may assist businesses in keeping existing trade flows open. This is a dynamic environment, and we will undertake further work through 2024 to better understand the impacts of regulatory difference on the UK internal market.

The UK Internal Market

Purpose and approch

This is the second annual report to be published by the Office for the Internal Market (OIM), which is a part of the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA). It discharges the CMA’s statutory responsibility under the UK Internal Market Act (‘UKIMA’) that the CMA must, no later than 31 March 2023 and at least once in every relevant 12 month period, prepare a report on:

-

the operation of the internal market in the United Kingdom, and

-

developments as to the effectiveness of the operation of that market.[footnote 1]

This chapter explains the OIM’s role, describes the approach we have taken in preparing this report.

OIM’s role

Our role is to assist the four governments across the UK by applying economic and other technical expertise to support the effective operation of the UK internal market. We have an advisory, not a decision-making role. This report focuses on the effective operation of the UK internal market in relation to goods, services and the regulated professions.

Governments may make policy interventions for a number of reasons which may, in turn, lead to differences in regulation emerging between the UK nations. Given our focus on the economic impacts of different regulatory choices across the UK nations, we recognise that the findings and issues raised in our reports are likely to constitute one consideration, among others, when a government or legislature determines its preferred policy and regulatory approaches.

Differences in regulation can lead to valuable innovations in policy making, which give other governments in the UK an opportunity to see policies in action before making their own decisions.

Approach to assessing developments in the internal market

To make sense of the internal market we need to use a variety of sources of information, each with its own strengths and weaknesses. The internal market comprises the combined activities of a very large number of businesses engaged in a wide range of economic activities, which are influenced by policy developed by governments across the UK. Furthermore, federal states and states with powers devolved to territories within them must typically undertake the task of managing an internal market, which involves balancing frictionless trade against the right of the territorial jurisdictions to set their own rules. While management of the UK internal market gives rise to similar challenges, there are particularities in a UK context, including the population size of England relative to the other nations and Northern Ireland’s land border with the EU. This complexity means there is no single dataset or methodology that would provide a fully accurate picture of the operation and developments as to the effectiveness of the UK internal market. We can, however, start to build a picture by considering: (i) total business activity; (ii) the actions of individual businesses (or businesses in a particular sector); and (iii) changes to government regulations across the four nations of the UK.

This report uses macro-level data on cross-border sales and purchases, which are good for providing an overall picture on the importance of trade and identifying macro trends but are less revealing in terms of why certain changes are taking place. To fill that gap in our understanding we must look at other data and indicators. One of the additional indicators we examine is the sectors of the economy that are experiencing regulatory difference and to what degree. We set out this data in Chapter 2.

For that purpose, and for the first time, we have attempted to map the proportion of each of the national economies that is exposed to regulatory difference and/or the Market Access Principles (‘the MAPs’)[footnote 2] using data on employment. As we did for the 202 to 2023 annual report, we also examine individual regulatory developments, as this provides a sense of the diversity and the nature of regulatory differences across the economy. In doing so, we take into account that the recent developments in relation to Common Frameworks[footnote 3], the Windsor Framework[footnote 4] and the process for excluding regulations from the MAPs[footnote 5] will have a bearing on how the internal market develops. We present this analysis in Chapter 3.

In order to understand how individual businesses might respond to regulatory difference, in Chapter 4 we have also examined how businesses are likely to adjust how they trade in response to regulatory changes.

Data on intra-UK trade

Key findings

-

analysing current intra-UK trade flows remains challenging, with only 3 of the four UK nations publishing intra-UK trade statistics, and methodological differences between the existing trade statistics. However, methodological improvements are underway

-

the most recent figures value intra-UK trade at £190billion, or around 10% of total UK GDP

-

intra-UK trade represented between 43% to 65% of the external sales and purchases of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, with this accounting for between 25% and 54% of the GDP of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland

-

15% of businesses report selling to other UK nations. This is a higher proportion of businesses than for international trade – 10% of businesses report exporting internationally. 10% of businesses report purchasing from other UK nations

-

businesses in manufacturing, wholesale and retail sectors are most likely to trade intra-UK. In Wales and Northern Ireland, businesses in manufacturing account for the largest value of intra-UK sales, while in Scotland, businesses supplying business and other services account for the largest value

-

larger businesses are more likely to trade intra-UK

-

of businesses that trade intra-UK, less than 10% report difficulties doing so due to rules and regulations, with more than half reporting no difficulties

This Chapter provides an overview of the trade-based evidence on the operation of the internal market and draws upon a number of sources, as outlined in Chapter 1. The Chapter provides an update on the value of intra-UK trade, who undertakes that trade, and discusses businesses’ experiences of trading within the UK. The data in this chapter presents one part of the picture of the internal market, by providing a high-level view of aggregate trade flows between the UK’s nations. It should be read in conjunction with the information in Chapters 3 and 4, which discuss changes to specific regulations and examine of how business supply chains are changing in response to regulatory differences.

Update on intra-UK trade data

This section provides an update on the value of intra-UK trade, in terms of both sales and purchases.[footnote 6] Throughout this chapter, we refer to trade flows in terms of sales of goods and services (for example, exports to other UK nations) and purchases of goods and services (for example, imports from other UK nations).

As noted in the 2022 to 2023 annual report, data on intra-UK trade is limited, with only 3 of the four UK nations (Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland) publishing statistics on the value of sales and purchases to the other UK nations. Lags in the publication of the datasets differ, as do their respective methodologies for data collection and production plus wording of questions. This makes comparability and estimates of total intra-UK trade challenging. Analysing current intra-UK trade flows remains challenging, although improvements are underway. In this year’s report, we also make use of additional ONS data from BICS and from HMRC, to better understand trade flows between Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

In March 2023, the OIM published a Data Strategy Roadmap[footnote 7] outlining the projects being undertaken by the Office for National Statistics (ONS), the Devolved Governments, UK Government departments and academics from around the UK, as well as the OIM, that may improve the collective understanding of how the UK internal market is operating. If the projects detailed within the OIM Data Strategy Roadmap achieve their objectives, experimental estimates of intra-UK trade covering all four UK nations may be available by Autumn 2024.

In July 2023, the four nations along with the ONS published a user guide to regional trade, outlining the various measures of trade, including their strengths and limitations.[footnote 8] Additionally, in December 2023 the ONS and the Alan Turing Institute published a new dataset on industry-to-industry payment flows based on payment systems data.[footnote 9] Regional breakdowns of this dataset are planned for 2024.

Some methodological improvements to trade statistics have already been implemented and these are cited throughout the chapter.

Value of intra-UK trade

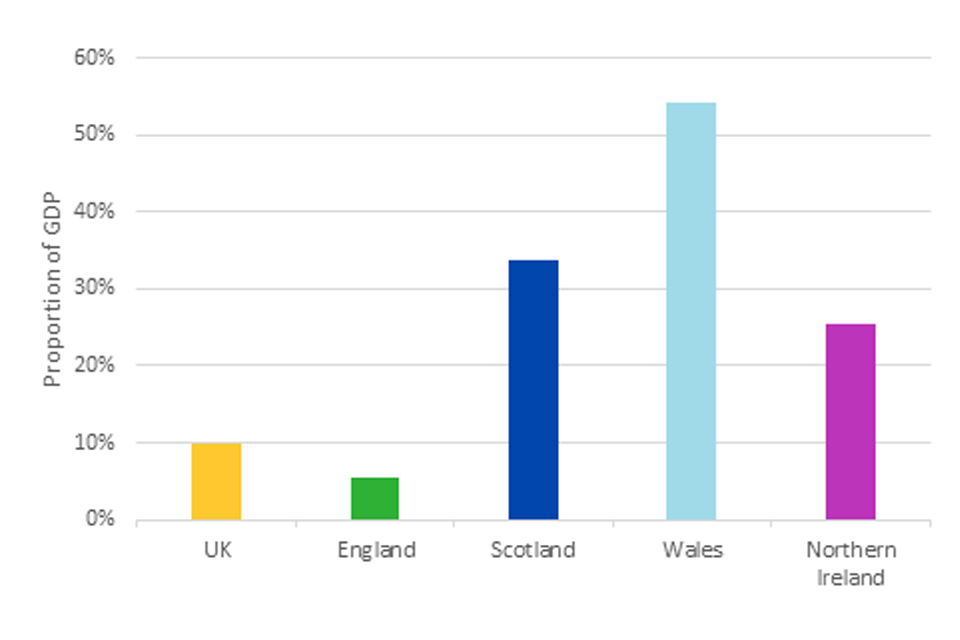

The Economic Statistics Centre of Excellence’s (ESCoE) dataset for 2015 (published in 2021) remains the most recent estimate of intra-UK trade that includes figures for England. ESCoE estimates that intra-UK sales in 2015 amounted to around £190 billion. In Figure 2.1, the variation in importance of economic trade is shown in the proportion of GDP that intra-UK trade represents. Using ESCoE 2015 data and 2015 GDP estimates,[footnote 10] intra-UK sales represented around 10% of total UK GDP.[footnote 11] Comparatively, England’s intra-UK sales represented only 6% of England’s GDP; Scotland’s intra-UK sales was 34% of Scottish GDP; for Wales, 54% of its GDP is made up of intra-UK sales; and Northern Ireland’s intra-UK sales represented 26% of Northern Ireland’s GDP.[footnote 12] As noted above, we expect the new intra-UK trade dataset (due in autumn 2024) will enable an update of the £190 billion estimate.

Figure 2.1: 2015 estimates of inter-regional trade as proportion of GDP

A bar graph of 2015 ESCoE inter-regional trade data of each UK nation as a proportion of each UK nations’ GDP.

For the UK, intra-UK sales represented 9.85% of total UK GDP.

England’s intra-UK sales represented 5.54% of England’s GDP; Scotland’s intra-UK sales was 33.70% of Scottish GDP; for Wales, 54.21% of its GDP is made up of intra-UK sales; and Northern Ireland’s intra-UK sales represented 25.52% of Northern Ireland’s GDP.

Source: Economic Statistics Centre of Excellence (2021); Regional economic activity by gross domestic product, UK - Office for National Statistics (ons.gov.uk)

Note: Excludes non-resident flows (goods or services which move between UK nations but may be produced or provided by a non-resident to the UK).

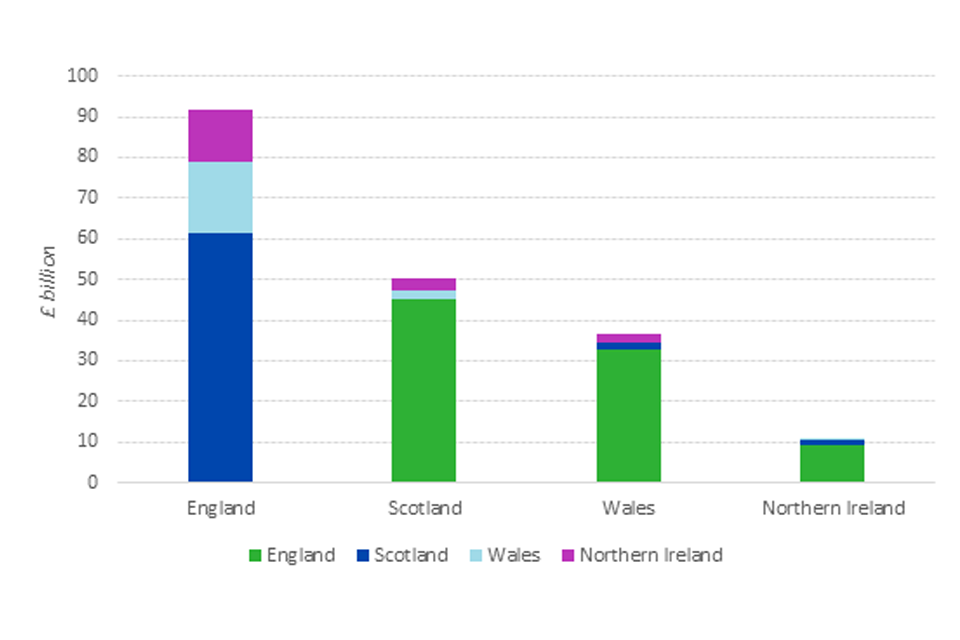

Figure 2.2 and Figure 2.3 show that intra-UK sales are broadly proportionate to the size on the national economies. In 2015 over 85% of intra-UK sales from Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland were made to England.[footnote 13] Comparatively, for England over three-fifths of intra-UK sales were to Scotland.

Figure 2:2: 2015 ESCoE estimates of intra-UK sales by UK nation (£billion)

A bar graph of 2015 ESCoE data showing the value of sales in £s that each UK nation sold to each of the other UK nations.

England sales to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland were around £61bn, £17.5bn and £13bn respectively.

Scotland sales to England, Wales and Northern Ireland were around £45bn, £2bn and £3bn.

Wales sales to England, Scotland and Northern Ireland were around £33bn, £2bn and £2bn respectively.

Northern Ireland sales to England, Scotland and Wales were around £9bn, £1bn and £0.4bn respectively.

Source: OIM Analysis of Economic Statistics Centre of Excellence (2021)

Note: Excludes non-resident flows (goods or services which move between UK nations but may be produced or provided by a non-resident to the UK).

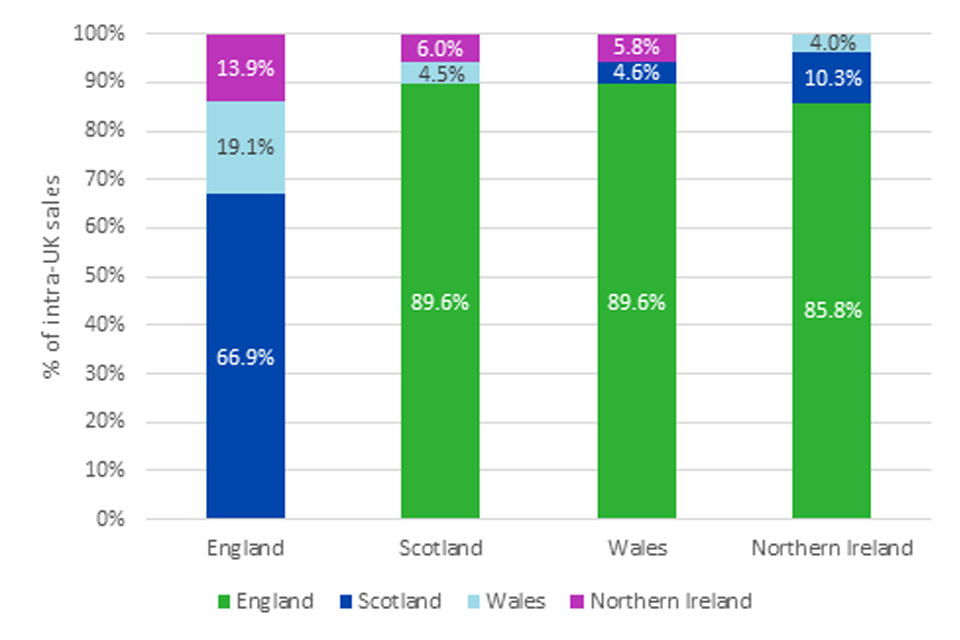

Figure 2.3: 2015 ESCoE estimates of intra-UK sales as a proportion of inter-regional trade by UK nation

A bar graph of 2015 ESCoE data showing intra-UK sales as a proportion of inter-regional trade by UK nation.

England’s proportion of sales to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland were 66.9%, 19.1% and 13.9% respectively.

Scotland’s proportion of sales to England, Wales and Northern Ireland were 89.6%, 4.5%, and 6.0% respectively.

Wales’s proportion of sales to England, Scotland and Northern Ireland were 89.6%, 4.6%, and 5.8% respectively.

Northern Ireland’s proportion of sales to England, Scotland and Wales were 85.8%, 10.3%, and 4.0% respectively.

Source: OIM Analysis of Economic Statistics Centre of Excellence (2021) Note: Excludes non-resident flows (goods or services which move between UK nations but may be produced or provided by a non-resident to the UK).

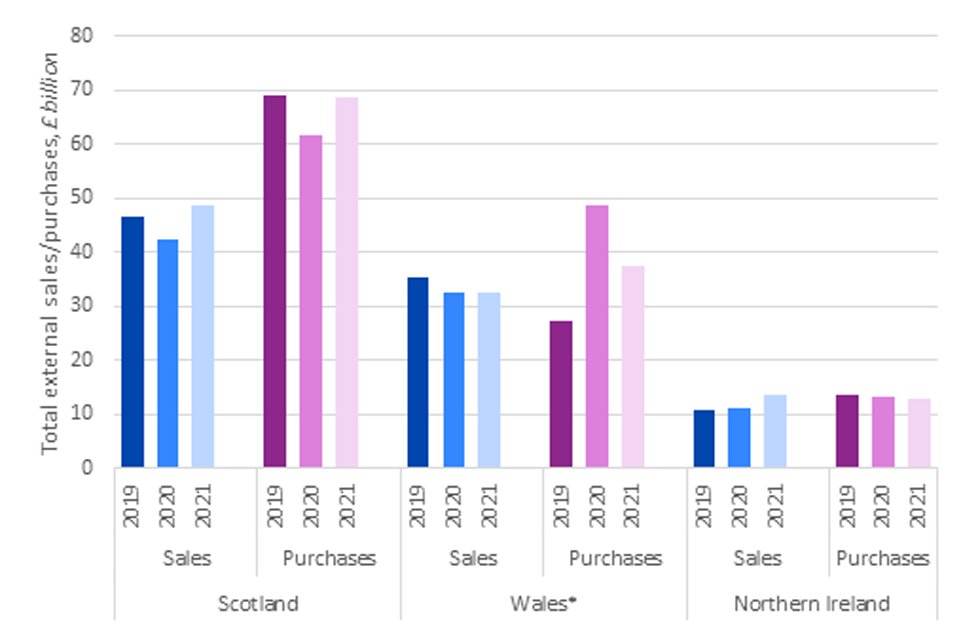

Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland publish their own data on intra-UK trade covering both sales and purchases. Whilst we include 2020 data this has been impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic,[footnote 14] therefore comparisons of 2021 data are made against pre-pandemic 2019 data. The overall trends are consistent with the findings in the 2022 to 2023 annual report. Figure 2.4 and Figure 2.5 show that:

-

total intra-UK sales for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland in 2021 amounted to £94.7 billion and total intra-UK purchases for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland were £119.1 billion in 2021

-

of these 3 nations, Scotland traded the most with the rest of the UK in absolute terms (see Figure 2.4) in 2021, followed by Wales and then Northern Ireland, with these absolute differences likely driven primarily by the relative sizes of their economies

-

the value of intra-UK trade as a proportion of each nation’s total external sales/purchases was broadly similar for Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland, ranging from 43 to 61% for sales and 59 to 65% for purchases in 2021 (see Figure 2.5). The proportion of external sales accounted for by intra-UK trade is significantly higher for each of these nations than the figure for the UK as a whole in 2015 (27%), suggesting that countries outside the UK account for a much bigger proportion of England’s sales than other UK nations do.

Figure 2.4: Total external sales and purchases from/to the rest of the UK for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland for 2019 to 2021 (£ billion)

A bar graph that gives purchases and sales from each of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland to the rest of the UK for 2019 to 2021.

Scotland sold £47bn to the rest of the UK in 2019, £42bn in 2020, and £49bn in 2021. Scotland purchased £69bn from the rest of the UK in 2019, £62bn in 2020, and £69bn in 2021.

Wales sold £35bn to the rest of the UK in 2019, £32bn in 2020, and £32bn in 2021. Wales purchased £27bn from the rest of the UK in 2019, £49bn in 2020, and £37bn in 2021.

Northern Ireland sold £11bn to the rest of the UK in 2019, £11bn in 2020, and £14bn in 2021. Northern Ireland purchased £14bn from the rest of the UK in 2019, £13bn in 2020, and £13bn in 2021.

Source: Northern Ireland Economic Trade Statistics, 2022; Trade Survey Wales, 2021 (*); GDP Quarterly National Accounts Scotland: 2023; Export Statistics Scotland, 2021.

Notes: Data has not been adjusted for inflation. External sales/purchases refer to trade outside of Wales either to/from the Rest of the UK, the EU, Non-EU, and Unallocated trade.

(*)OIM analysis includes unallocated sales/purchases from the Welsh data. ‘Unallocated sales/purchases’ are where respondents have been unable to allocate this trade to a specific destination/origin (Rest of UK, EU, Non-EU, and Wales) therefore these figures are likely to be a lower estimate of Welsh trade with the rest of the UK, and therefore should be treated with caution.[footnote 15]

TSW state 2020 and 2021 data are currently provisional, 2019 has been revised.

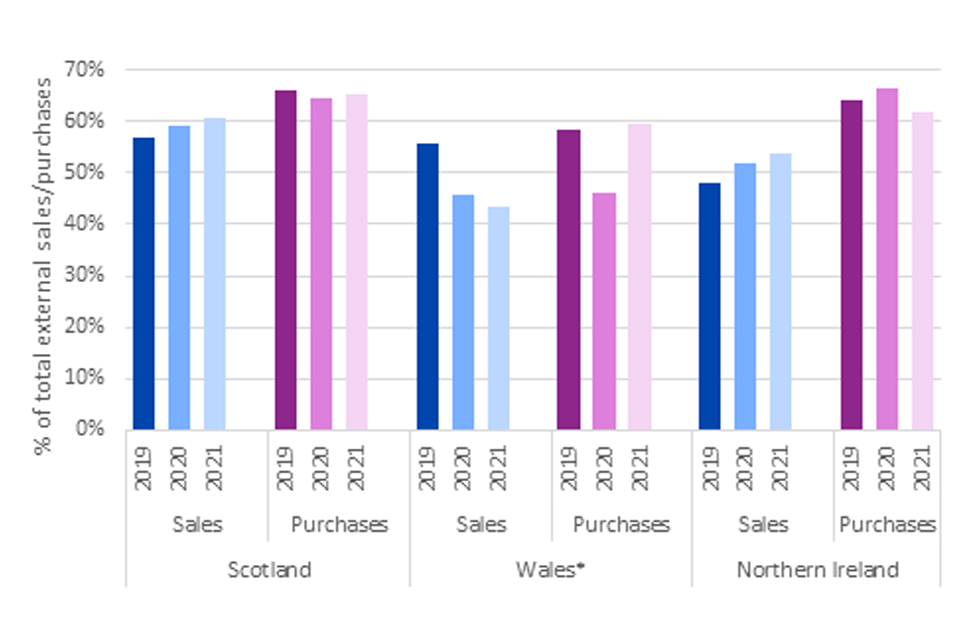

Figure 2.5: Intra-UK trade as a proportion of total external purchases/sales for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland for 2019 to 2021

A bar graph showing the proportion of the value of intra-UK trade as a proportion of total external purchases/sales for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland for 2019 to 2021.

For Scotland, 57% of external sales and 66% of purchases were to/from the rest of the UK in 2019; 59% of sales and 64% of purchases in 2020; 61% of sales and 65% purchases in 2021.

For Wales, 56% of external sales and 58% of purchases were to/from the rest of the UK in 2019; 46% of sales and 46% of purchases in 2020; 43% of sales and 59% purchases in 2021.

For Northern Ireland, 48% of external sales and 64% of purchases were to/from the rest of the UK in 2019; 52% of sales and 66% of purchases in 2020; 54% of sales and 62% purchases in 2021.

Source: Northern Ireland Economic Trade Statistics, 2022; Trade Survey Wales, 2021; GDP Quarterly National Accounts Scotland: 2023; Export Statistics Scotland, 2021.

Notes: Data has not been adjusted for inflation. External sales/purchases refer to trade outside of Wales either to/from the Rest of the UK, the EU, Non-EU, and Unallocated trade.

OIM analysis includes unallocated sales/purchases from the Welsh data. ‘Unallocated sales/purchases’ are where respondents have been unable to allocate this trade to a specific destination/origin (Rest of UK, EU, Non-EU, and Wales) therefore these figures are likely to be a lower estimate of Welsh trade with the rest of the UK.[footnote 16] TSW state 2020 and 2021 data are currently provisional, 2019 has been revised.

Below we consider the trade statistics produced by each nation in further detail.[footnote 17]

Scotland data

Scotland’s sales (export) data has been sourced from ‘Export Statistics Scotland’ which is principally based on a business survey.[footnote 18] This publication uses a different data source from those reported for 2019 which we included in our 2022 to 2023 annual report, improving the accuracy of the annual estimates for 2019 to 2021.[footnote 19] Purchases (import) statistics are sourced from Quarterly National Accounts.[footnote 20]

In 2021, Scotland’s sales to the rest of the UK were valued at an estimated £48.6 billion and accounted for over half (61%) of all Scotland’s external sales. This is in line with previous estimates.[footnote 21] Purchases from the rest of the UK have also remained consistent with previous estimates at around £69 billion, also accounting for over almost two-thirds (65%) of all Scotland’s external purchases.

Wales data

Welsh trade data comes from the Trade Survey for Wales (TSW), an online survey of businesses in Wales.[footnote 22] Improvements to the TSW methodology are underway and the results of the 2021 survey are described as ‘official statistics in development’ (the new terminology for ‘Experimental Statistics’). Methodological improvements, namely across-years imputation, have been applied to the sales (export) data between 2019-2021, but this new approach has not been applied to the purchases (import) data.[footnote 23] Therefore, caution is needed when analysing the purchases data. The TSW also acknowledges the presence of relatively high unallocated sales and unallocated purchases.[footnote 24]

In 2021, Welsh sales to the rest of the UK were valued at an estimated £32.5 billion and accounted for 43% of all Welsh external sales. Most of the sales in 2021 were to England with 84% (£27.2 billion), followed by Scotland with 5% (£1.6 billion) and Northern Ireland with 3% (£1.1 billion). A further 8% (£2.6 billion) were unallocated sales within the UK.[footnote 25] The data suggests sales to the rest of the UK have declined from 2019, which was estimated at £35.3 billion, (however the proportion of total external sales has increased to 56% see Figure 2.55).[^26] However there was a large increase in unallocated sales from 2019 to 2021.[footnote 27]

Purchases into Wales from the rest of the UK were £37.4 billion in 2021, equating to 59% of total Welsh external purchases. For 2021 most of the purchases from the rest of the UK were from England with 85% (£31.9 billion), followed by Scotland and Northern Ireland with 1% (£0.5 billion) and 0.4% (£0.2 billion) respectively. A further 13% (£4.8 billion) of UK purchases were unable to be allocated.[footnote 28]

Northern Ireland data

The Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency (NISRA) conducts an annual survey on trade, the Northern Ireland Economic Trade Statistics (NIETS).[footnote 29] Improvements in the survey are underway[footnote 30] with a new data portal and data visualisation hub being launched this year. As well as comparable annual estimates for 2019 to 2021, estimates are available for 2022.

In 2021, Northern Ireland’s sales to the rest of the UK were valued at an estimated £13.7 billion and accounted for 54% of all Northern Ireland’s external sales. Purchases from the rest of the UK are estimated at around £13.1 billion, accounting for 62% of all Northern Ireland’s external purchases. [footnote 31]

Recent NIETS estimates for 2022 show sales to the rest of the UK have increased to an estimated £15.7 billion however remains the same in proportion of value of trade at 54%. Purchases from the rest of the UK have stayed stable at an estimate £13.1 billion.[footnote 32]

The ONS and HMRC also provide data on trade movements between Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

The ONS Business Insights and Conditions Survey[footnote 33] (BICS), a fortnightly business survey, asks businesses whether they have sent goods from Great Britain to Northern Ireland and from Northern Ireland to Great Britain in the previous 12 months and how the volume of goods sent compared with the previous month.[footnote 34] This data source is a helpful cross-check for understanding any changes in behaviour over time. An average of 4.5% of businesses[footnote 35] stated they had sent goods from Great Britain to Northern Ireland in the last 12 months[footnote 36] (albeit representing a low proportion of businesses, as shown below in the HMRC Customs data, this represents a significant value of goods from Great Britain to Northern Ireland). BICS data also shows that less than 2% of businesses sent goods from Northern Ireland to Great Britain in the last 12 months.[footnote 37] In terms of volumes sent, the BICS data shows that approximately 48% of businesses reported that volumes had stayed the same for Great Britain to Northern Ireland sales, 24% of businesses stated volumes decreased, and 5% of businesses reported volumes increased.[footnote 38] For volumes sent from Northern Ireland to Great Britain, similar proportions were observed. 51% of businesses stated that volumes stayed the same for Northern Ireland to Great Britain sales, 28% reported volumes decreased, and volumes increased for 3% of businesses.[footnote 39] These responses have stayed relatively consistent over time.

HMRC report on the movements of goods into Northern Ireland from Great Britain based on customs data.[footnote 40] HMRC reports that the ‘Total value associated with full declarations cleared by HMRC for movements of goods into Northern Ireland from Great Britain in 2022 was £14.1 billion, up 13% from the 2021 total value of £12.4 billion.’[footnote 41] For context, the 2021 value of customs declarations represented around 24% of Northern Ireland’s GDP.[footnote 42] HMRC also reports that the ‘Total number of full declarations cleared by HMRC for movements of goods into Northern Ireland from Great Britain in 2022 was 1,470,000, up by 41% when compared with the 2021 declaration count of 1,040,000. Total number of unique businesses moving goods into Northern Ireland from Great Britain in 2022 was 12,800, up by 22% when compared with the 2021 business count of 10,500’.[footnote 43] Whilst the data indicates that the total number of full declarations cleared by HMRC and the total number of unique businesses moving goods into Northern Ireland from Great Britain, as seen in Figure 2.6, have increased from 2021 to 2022, HMRC notes that caution is advised when drawing conclusions about the year-on-year changes given the data reports the date the goods were cleared, and not when the goods were moved. Data was only collected from January 2021, therefore in the first year of collection it is likely that there would be less than a full year of transactions recorded because of the lag in reporting.[footnote 44]

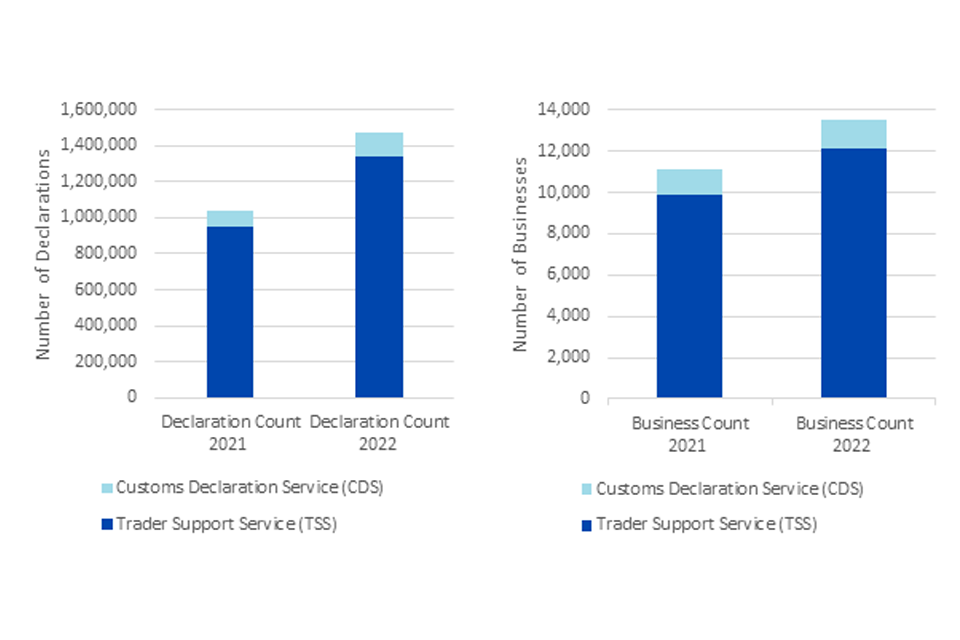

Figure 2.6 : Yearly count of full declarations and count of businesses associated with full declarations cleared by HMRC split by different declaration systems

Two bar charts showing the yearly count of full declarations (first bar chart) and count of businesses (second bar chart) associated with full declarations cleared by HMRC split by different declaration systems.

The first bar chart illustrating the number of declarations with full declarations cleared by HMRC, shows that in 2021, the total number of declarations was 1,040,000 with Trader Support Service (TSS) accounting for 950,000 declarations and Customs Declaration Service (CDS) accounting for 90,000 declarations. In 2022, the total number of declarations was 1,470,000 with Trader Support Service (TSS) accounting for 1,340,000 declarations and Customs Declaration Service (CDS) accounting for 130,000 declarations.

The second bar chart illustrating the count of businesses with full declarations cleared by HMRC, shows that in 2021, the total business count was 10,500, with Trader Support Service (TSS) accounting for 9,500 businesses and Customs Declaration Service (CDS) accounting for 1,200 businesses. In 2022, the total business count was 12,800, with Trader Support Service (TSS) accounting for 12,100 businesses and Customs Declaration Service (CDS) accounting for 1,400 businesses.

Source: Administrative data extracted from HMRC’s Customs Declaration Service (CDS)

Who trades within the UK?

In this section we review the best available evidence to provide insights into the extent to which different types of business trade with other parts of the UK and the potential barriers they face. We also note whether there has been a change since the 2022 to 2023 annual report. We rely on the ONS Business Insights and Conditions Survey[footnote 45] (BICS), which has questions on the proportion of UK businesses that trade with other UK nations and the challenges businesses face when doing so, and national trade data. It is noted that data is based on weighted estimates from the voluntary fortnightly business survey (BICS) about financial performance, workforce, prices, trade, and business resilience. The survey was sent to around 39,000 UK businesses, and results presented in this report are based on a response rate of around 20% to 30% (7,800 to 11,700 businesses) across Waves 63 to 95 of the survey.[footnote 46]

BICS asked businesses whether they had sold goods or services to/from other UK nations.[footnote 47] A new question on purchases was included in the October 2023 BICS. There is only one data point for purchases, therefore we do not make inferences from responses but purely report findings. Next year, more data points will enable us to make more informative comparisons.

The results are consistent with the findings in the 2022 to 2023 annual report, with around 15% of businesses reporting they had sold to other UK nations.[footnote 48] For comparison, around 10% of businesses had exported internationally in the last 12 months.[footnote 49] Approximately 10% of businesses reported they had purchased from other UK nations within the last 12 months.[footnote 50]

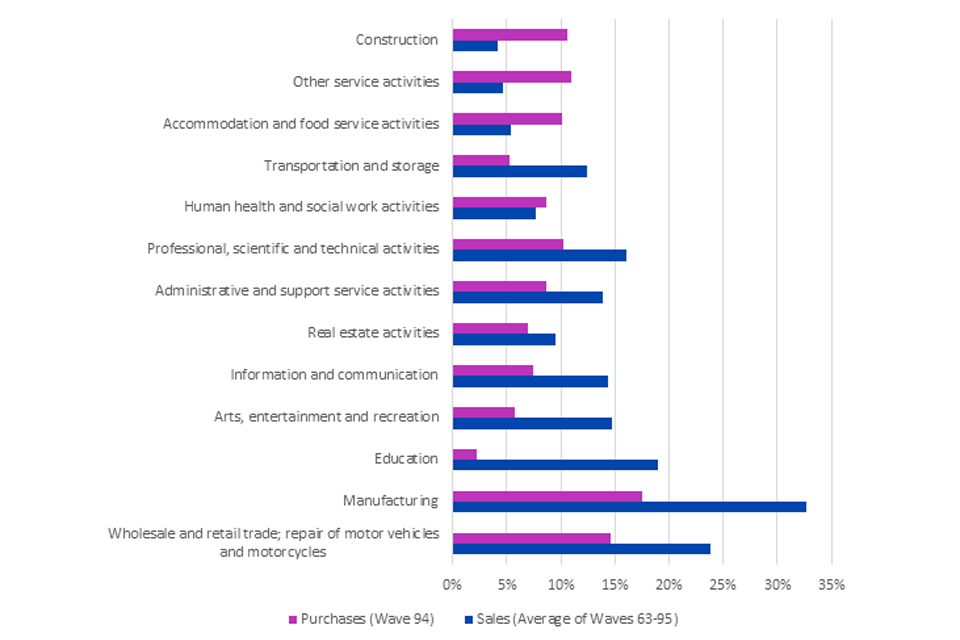

Trade by industry sector

BICS evidence suggests that businesses in the manufacturing and wholesale and retail trade sectors are generally more likely to trade with other UK nations (see Figure 2.7). On average, the survey results indicate over 30% of businesses within the manufacturing industry sell to other UK nations, whilst approximately 18% of businesses in this sector state they purchase from other UK nations (purchase data is one data point).[footnote 51] For businesses within the wholesale and retail trade industry, on average approximately 25% sell to other UK nations whilst approximately 15% state they purchase from other UK nations.[footnote 52]

Figure 2.7: Proportion of businesses making intra-UK sales/purchases by industry sector

A bar graph showing the proportion of businesses making intra-UK purchases and sales by industry sector.

For the Construction sector, the proportion of businesses with purchases from the Rest of the UK is 11% and the proportion of businesses that sold to the Rest of the UK is an average of 4%.

For the Other service activities sector, the proportion of businesses with purchases from the Rest of the UK is 11% and the proportion of businesses that sold to the Rest of the UK is an average of 5%.

For the Accommodation and food service activities sector, the proportion of businesses with purchases from the Rest of the UK is 10% and the proportion of businesses that sold to the Rest of the UK is an average of 5%.

For the Transportation and storage sector, the proportion of businesses with purchases from the Rest of the UK is 5% and the proportion of businesses that sold to the Rest of the UK is an average of 12%.

For the Human health and social work activities sector, the proportion of businesses with purchases from the Rest of the UK is 9% and the proportion of businesses that sold to the Rest of the UK is an average of 8%.

For the Professional, scientific and technical activities sector, the proportion of businesses with purchases from the Rest of the UK is 10% and the proportion of businesses that sold to the Rest of the UK is an average of 16%.

For the Administrative and support service activities sector, the proportion of businesses with purchases from the Rest of the UK is 9% and the proportion of businesses that sold to the Rest of the UK is an average of 14%.

For the Real estate activities sector, the proportion of businesses with purchases from the Rest of the UK is 7% and the proportion of businesses that sold to the Rest of the UK is an average of 9%.

For the Information and communication sector, the proportion of businesses with purchases from the Rest of the UK is 7% and the proportion of businesses that sold to the Rest of the UK is an average of 14%.

For the Arts, entertainment and recreation sector, the proportion of businesses with purchases from the Rest of the UK is 6% and the proportion of businesses that sold to the Rest of the UK is an average of 15%.

For the Education sector, the proportion of businesses with purchases from the Rest of the UK is 2% and the proportion of businesses that sold to the Rest of the UK is an average of 19%.

For the Manufacturing sector, the proportion of businesses with purchases from the Rest of the UK is 18% and the proportion of businesses that sold to the Rest of the UK is an average of 33%.

For the Wholesale and retail trade; repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles sector, the proportion of businesses with purchases from the Rest of the UK is 15% and the proportion of businesses that sold to the Rest of the UK is an average of 24%.

Source: Business Insights and Conditions Survey

BICS questions: ‘In the last 12 months, has your business sold goods or services to customers in other UK nations?’ ‘In the last 12 months, has your business purchased goods or services from suppliers in other UK nations’.

Notes: Sales data: Average of Wave 63 (8-21 August 2022), Wave 68 (17-30 October 2022), Wave 75 (23 January – 5 February 2023), Wave 81 (17 April 2023 to 30 April 2023), Wave 88 (24 July 2023 to 6 August 2023) and Wave 95 (30 October 2023 to 12 November 2023). Purchase data: Wave 94 (16 October 2023 to 29 October 2023).

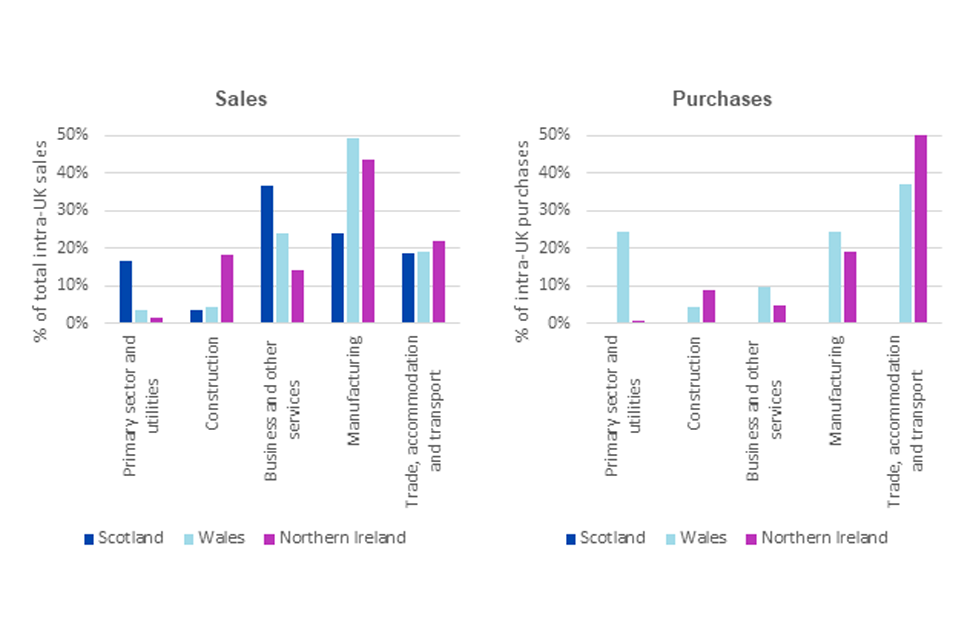

National trade data shows the proportion of intra-UK sales by industry sectors varies by UK nation (see Figure 2.8). For example, in Wales and Northern Ireland, the Manufacturing sector accounts for the largest value of sales to the rest of the UK whilst in Scotland, Business and other services was the largest sector. This is consistent with our findings within the 2022 to 2023 annual report.

-

in 2021, Scotland’s sales to the rest of the UK relied heavily on Business and other services[footnote 53], particularly financial and insurance activities valued at an estimated £9.2 billion (19% of Scotland’s sales). In comparison international sales relied more heavily on manufacturing.[footnote 54] This has been a consistent trend since 2019. Purchase data by sector for 2021 is not available for Scotland.[footnote 55]

-

for Wales, in 2021, the Manufacturing sector made up almost half (49.1%, £16.0 billion) of the value of sales to the rest of the UK.[footnote 56] This was followed by the Business and other services sector (23.9%, £7.8 billion). The Trade, accommodation and transport sector accounted for the highest proportion of Welsh purchases from the rest of the UK in 2021 at 37.2% (£13.9 billion).[footnote 57] This was followed by almost a quarter of purchases from the Manufacturing sector (24.5%, £9.1 billion), in 2021

-

for Northern Ireland, the Manufacturing sector also made up almost half (43%, £5.9 billion) of the value of sales to the rest of the UK. The Trade, accommodation and transport sector accounted for the highest proportion of Northern Ireland purchases from the rest of the UK in 2021 at 64.7% (£8.5 billion). This is consistent with purchase data in both 2019 and 2020, with Manufacturing being the second largest sector (19.1%, £2.5 billion in 2021)

Figure 2.8: Estimates of intra-UK sales/purchases by industry sector, 2021

Two bar graph showing estimates of sales and purchases in 2021 to other UK nations for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland for five broad industry sectors (Primary sector and utilities; Construction; Business and other services; Manufacturing; and Trade accommodation and transport).

The first bar chart illustrating the proportion of intra-UK sales by broad industry sector, shows for Scotland, 17% of sales to other UK nations were made by Primary sector and utilities; 4% by Construction; 37% by Business and other services; 24% by Manufacturing; and 19% by Trade accommodation and transport. For Wales, 4% of sales to other UK nations were made by Primary sector and utilities; 4% by Construction; 24% by Business and other services; 49% by Manufacturing; and 19% by Trade accommodation and transport. For Northern Ireland, 2% of sales to other UK nations were made by Primary sector and utilities; 18% by Construction; 14% by Business and other services; 43% by Manufacturing; and 22% by Trade accommodation and transport.

The second bar chart illustrating the proportion of intra-UK purchases by broad industry sector. For Scotland, there was no purchase data by sector in 2021. For Wales, 24% of purchases from other UK nations were made by Primary sector and utilities; 4% by Construction; 10% by Business and other services; 24% by Manufacturing; and 37% by Trade accommodation and transport. For Northern Ireland, 1% of purchases from other UK nations were made by Primary sector and utilities; 9% by Construction; 5% by Business and other services; 19% by Manufacturing; and 65% by Trade accommodation and transport.

Source: Northern Ireland Economic Trade Statistics, 2022; Trade Survey Wales, 2021; GDP Quarterly National Accounts Scotland: 2023; Export Statistics Scotland, 2021.

Note: Scotland does not release purchase data by sector.

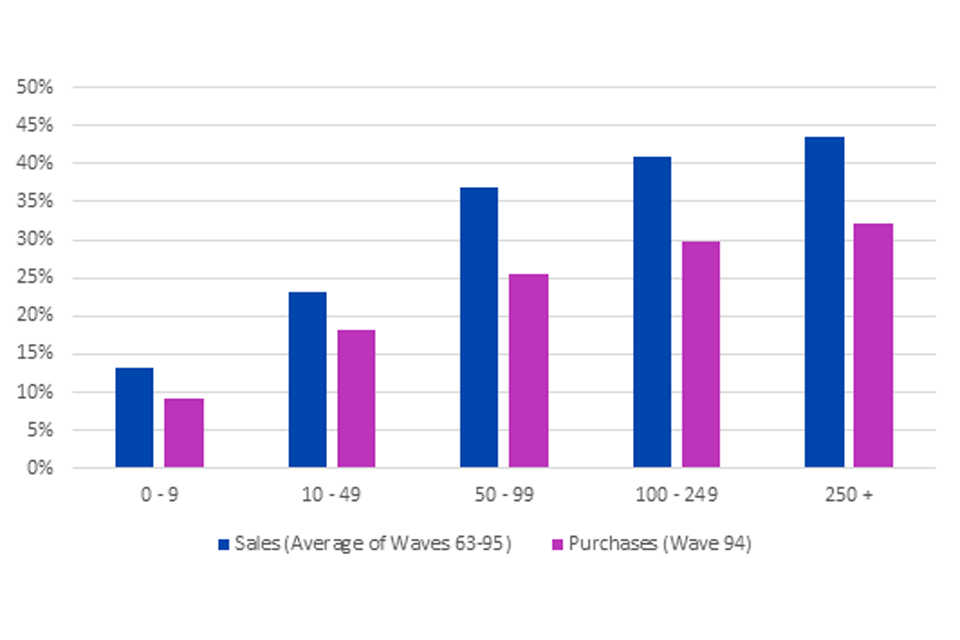

Trade by business size

Our analysis of the available evidence suggests business size continues to impact the likelihood of intra-UK trade. Evidence from the BICS suggests that larger businesses are more likely to trade across the UK than smaller ones, both in terms of sales and purchases.[footnote 58] As shown in Figure 2.9, less than 15% of micro businesses (0-9 employees) made sales to other UK nations, compared with over 40% of large businesses (250+ employees). This trend is also reflected in purchases.

Figure 2.9: Proportion of businesses with intra-UK sales/purchases by size band (employees)

A bar graph showing the proportion of businesses with sales to and purchases from the Rest of the UK by size band.

The graph shows that an average of 13% of businesses with 0-9 employees sold to other UK nations and 9% purchased from other UK nations.

For businesses with 10-49 employees, an average of 23% sold to other UK nations, and for purchases this figure was 18%.

An average of 37% of businesses with 50-99 employees made sales to other UK nations and 26% made purchases from other UK nations.

For businesses with 100-249 employees, an average of 41% made sales from other UK nations and 30% made purchases from other UK nations.

An average of 43% of businesses with 250 plus employees made sales to other UK nations and 32% made purchases from other UK nations.

Source: Business Insights and Conditions Survey

BICS questions: ‘In the last 12 months, has your business sold goods or services to customers in other UK nations?’ ‘In the last 12 months, has your business purchased goods or services from suppliers in other UK nations’.

Notes: A large proportion of the BICS sample is accounted for by small businesses

Sales data: Average of Wave 63 (8-21 August 2022), Wave 68 (17-30 October 2022), Wave 75 (23 January – 5 February 2023), Wave 81 (17 April 2023 to 30 April 2023), Wave 88 (24 July 2023 to 6 August 2023) and Wave 95 (30 October 2023 to 12 November 2023). Purchase data: Wave 94 (16 October 2023 to 29 October 2023).

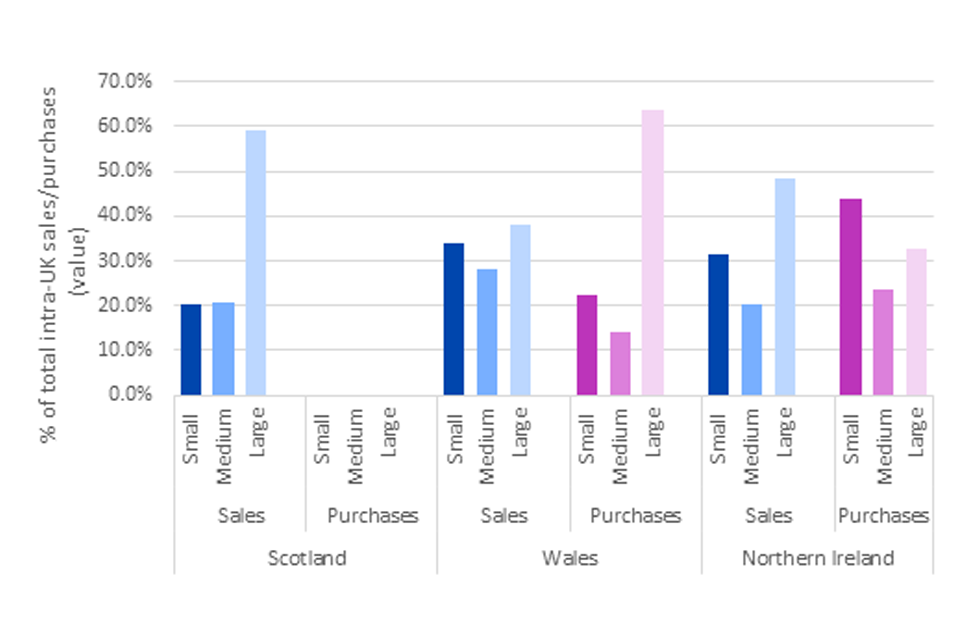

Evidence from the BICS is largely supported by other intra-UK trade data from Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, as seen in Figure 2.10.

-

for Scotland and Northern Ireland, from 2019-2021 there has been a consistent picture that larger businesses represented a higher proportion of sales to the rest of the UK (at approximately 60% for Scotland and approximately 45% for Northern Ireland)

-

for Wales, in 2021, large businesses accounted for a higher proportion of trade across the UK than smaller ones, both in terms of sales (38%, £12.4 billion) and purchases (64%, £23.8 billion).[footnote 59] For sales, this is a change from 2019, which saw medium sized businesses marginally having the largest share of total sales to the rest of the UK (39%, £13.6 billion), closely followed by large businesses (38%, £13.3 billion). For purchases the trend has remained the same, with large businesses representing the majority of trade to the rest of the UK (57%, £15.6 billion in 2019)

Figure 2.10: Estimates of intra-UK sales/purchases by business size, 2021

A bar graph showing estimates of sales to and purchase from other UK nations for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland by business size (Small = 0-49 employees, Medium = 50-249 employees, Large = 250+ employees).

For Scotland, 20% of sales to other UK nations were made by Small businesses, 21% by Medium businesses, and 59% by Large businesses. For Scotland, there was no purchase data by business size in 2021.

For Wales, 34% of sales to other UK nations were made by Small businesses, 28% by Medium businesses, and 38% by Large businesses. For Wales, 22% of purchases from other UK nations were made by Small businesses, 14% by Medium businesses, and 64% by Large businesses.

For Northern Ireland, 31% of sales to other UK nations were made by Small businesses, 20% by Medium businesses, and 48% by Large businesses. For Northern Ireland, 44% of purchases from other UK nations were made by Small businesses, 24% by Medium businesses, and 33% by Large businesses.

Source: Northern Ireland Economic Trade Statistics, 2022; Trade Survey Wales, 2021; GDP Quarterly National Accounts Scotland: 2023; Export Statistics Scotland, 2021.

Note: Scotland does not release purchase data;

Business Sizes are as follows: Small = 0-49 employees, Medium = 50-249 employees, Large = 250+ employees

Experiences of intra-UK trade

Based on BICS[footnote 60], it continues to be the case that more than half of businesses that sold goods and services to customers in other UK nations did not face any challenges when doing so.[footnote 61] Of those businesses who did engage in trade with other UK nations, the number experiencing challenges due to differences in rules or regulations is low at less than 10% and has remained low over time.[footnote 62] In the 2022 to 2023 annual report transport costs[footnote 63] were cited as the biggest problem, but now a lack of demand[footnote 64] is the highest reported concern with 17% of businesses citing this issue. Challenges related to the Northern Ireland Protocol was stated by an average of 8% of businesses as a challenge experienced when selling goods or services to customers in other UK.[footnote 65]

Conclusion

In 2021, intra-UK trade remained important to the UK nations, representing between 43% to 65% of the external sales and purchases of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. This represented £94.7 billion worth of intra-UK sales for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland and £119.1 billion for intra-UK purchases in 2021. To date, we do not see much change over time, either looking back to 2019 or, in the case of Northern Ireland where we have more up to date numbers, looking forward to 2022. It is too early to comment on overall trends given the disruption from Covid-19. Updated data for England is not available.[footnote 66] As stated in last year’s annual report, the Economic Statistics Centre of Excellence (ESCoE) estimates that intra-UK sales (including figures for England) amounted to around £190 billion in 2015.

In this year’s report, we make use of additional ONS data from BICS and from HMRC, to better understand trade flows between Great Britain and Northern Ireland. BICS data suggests an average of 4.5% of businesses stated they had sent goods from Great Britain to Northern Ireland in the last 12 months (albeit representing a low proportion of businesses, this represents a significant value of goods from Great Britain to Northern Ireland, with HMRC reporting that the ‘Total value associated with full declarations cleared by HMRC for movements of goods into Northern Ireland from Great Britain in 2022 was £14.1 billion, up 13% from the 2021 total value of £12.4 billion’. For context, the 2021 value of customs declarations represented around 24% of Northern Ireland’s GDP.[footnote 67] For goods sent from Northern Ireland to Great Britain this was less than 2%. Further, HMRC report that, based on customs data, ‘the total number of unique businesses moving goods into Northern Ireland from Great Britain in 2022 is 12,800, up by 22% when compared with the 2021 business count of 10,500’, although caution must be exercised when comparing year-on-year figures due to lags in the data as explained at paragraph 2.21.

BICS evidence indicates that businesses in the manufacturing and wholesale and retail trade sectors are generally more likely to trade with other UK nations. National trade data shows the proportion of intra-UK sales by industry sectors varies by UK nation. For example, in Wales and Northern Ireland, the Manufacturing sector accounted for the largest value of sales to the rest of the UK whilst in Scotland, Business and other services was the largest sector. For intra-UK purchases, we only have data for Wales and Northern Ireland, whereby we observed that purchases from Trade, Accommodation and Transport sector is the largest proportion of total external purchases, followed by the Manufacturing sector. This has been a consistent trend for both intra-UK sales and purchases by industry sector since 2019.

In 2021, we observed that in terms of intra-UK sales, larger firms contributed a higher proportion of total external sales to the rest of the UK for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. This is a consistent trend since 2019 for both Scotland and Northern Ireland. For Wales, in 2019 medium sized businesses marginally had the largest share of intra-UK sales at 39% compared to large businesses at 38%. Further, this intra-UK trade data is largely supported by evidence from the BICS, whereby we continue to find that trade is more common among larger businesses.

Finally, we continue to observe that businesses are generally finding it easy to trade with other UK nations, with the majority of firms responding to the BICS that they have not encountered challenges.

Overall, the available data on intra-UK trade remains limited but improvements are underway. As set out in the OIM Data Strategy Roadmap[footnote 68] projects being undertaken should improve the collective understanding of how the UK internal market is operating. We expect estimates of intra-UK trade covering all 4 UK nations to be available by Autumn 2024. Additionally, next year with more data points, we will be able to make better comparisons on both sales and purchases from the BICS data.

Regulatory landscape and developments

Key findings

-

over the last year, there has been a significant increase in the number of proposed differences in regulations within the scope of UKIMA

-

most of these proposed regulations are in relation to goods although there have also been developments in relation to services and regulated professions

-

the goods sector most affected is food and drink. For services, the proposed regulations apply to a more diverse range of economic activities. A small number of proposed regulations relate to defining new regulated professions

-

proportionally speaking, substantially more economic activity (as measured by employment) in services is outside the scope of UKIMA than is the case for goods but the size of the services sector relative to goods means that in absolute terms most economic activity that is subject to UKIMA is in services

-

to date, there have been only modest effects on internal market in relation to goods. It is too early to identify effects in relation to services. We have not identified effects in relation to the regulated professions

In this chapter we discuss the regulatory landscape and the regulatory developments within the scope of UKIMA in relation to each of goods, services and regulated professions. That discussion must be understood in the light of various developments to the internal market regime which have taken place over the last year. A summary of those changes is set out at Appendix A. It should also be read in conjunction with the data on aggregate trade flows discussed in Chapter 1, which helps position these developments discussed in this chapter in their broader context. In addition, 4 of the regulatory developments we discuss in this chapter form the basis for the case studies of businesses’ strategies in response to regulatory differences that are set out in Chapter 4.

Goods

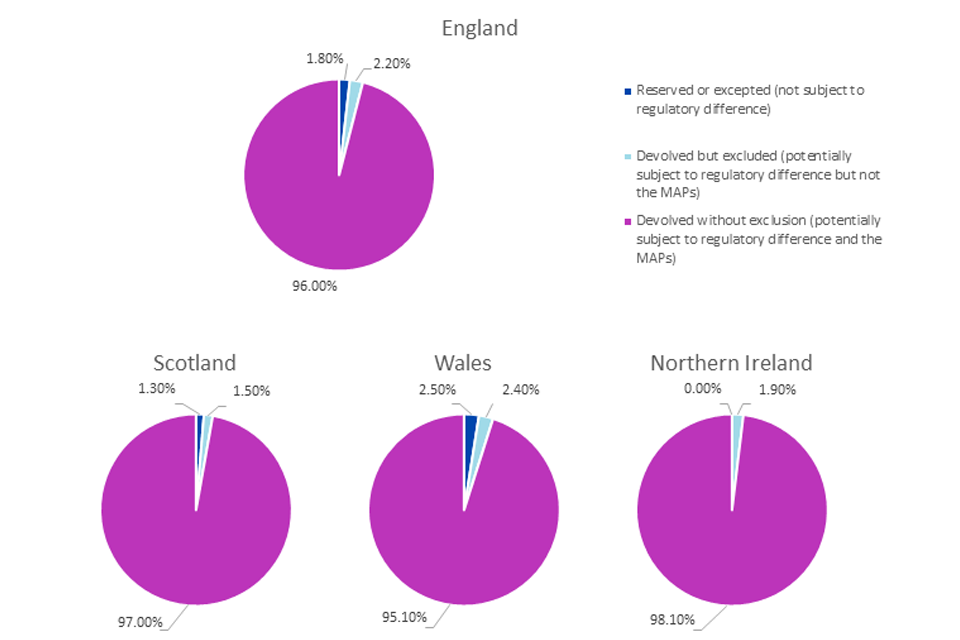

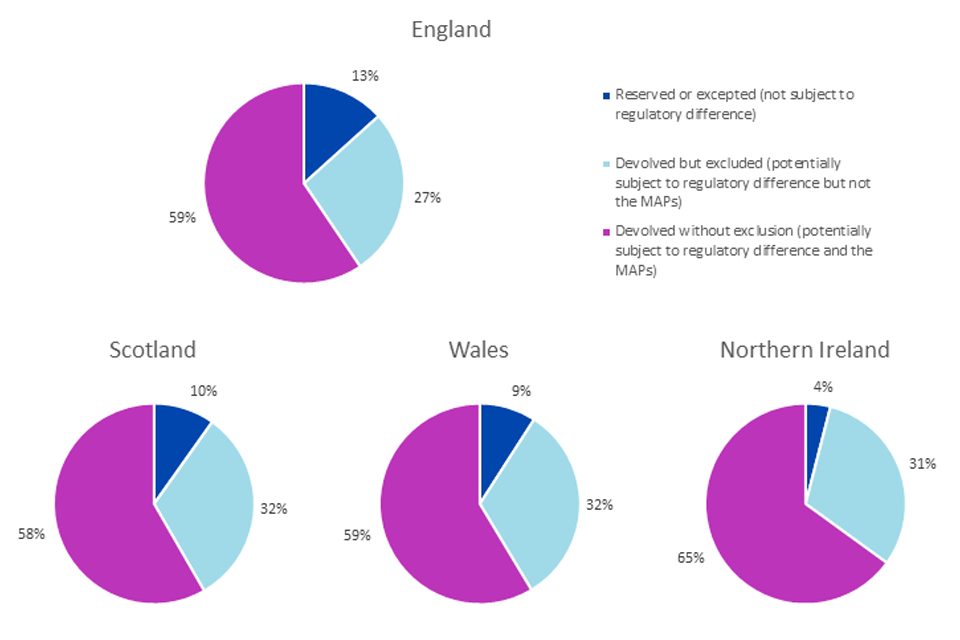

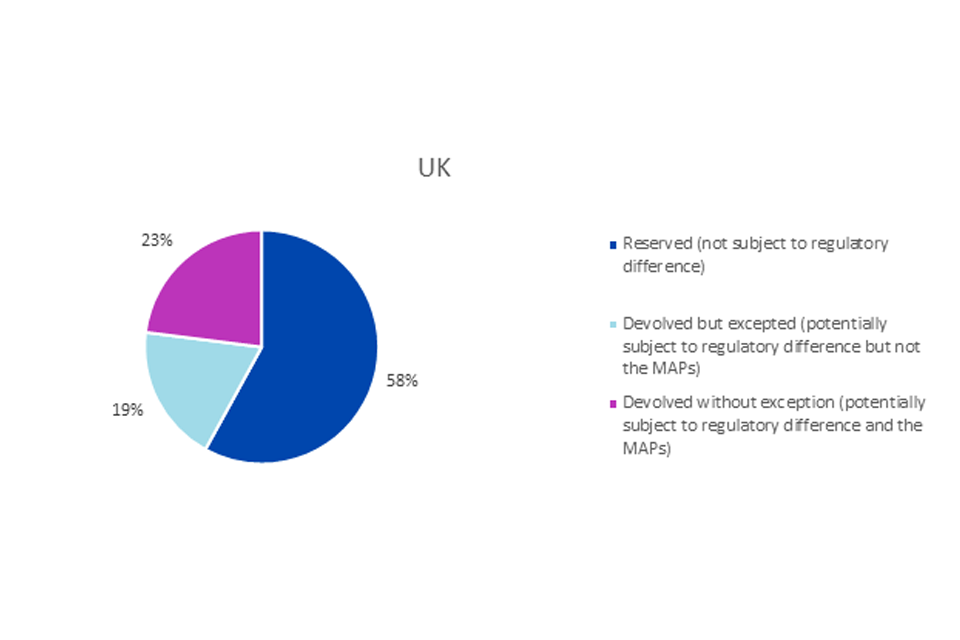

Regulatory landscape assessment in relation to goods

Figure 3.1 shows for each nation the proportion of employment[footnote 69] that is in sub-sectors where sector-specific policy making falls into one of 3 categories:

-

employment in sub-sectors where sector specific policy making is reserved (ie not subject to regulatory difference between the nations)[footnote 70]

-

employment in sub-sectors where sector specific policy making is devolved but excluded from UKIMA (ie potentially subject to regulatory difference but not the MAPs)

-

employment in sub-sectors where sector-specific policy making is devolved but is not excluded from UKIMA (ie potentially subject to regulatory difference and the MAPs)

The data shows that for each nation the proportion of employment in goods sub-sectors that are in the first category (where there cannot be regulatory difference within GB and only between GB and NI in the case of UK-EU divergence) are a small proportion of total employment in goods (for detail on the methodology used to calculate these figures see Appendix B – the figures should be treated as rough estimates). Of the goods sub-sectors where regulations could differ, in each nation, only a small percentage is in sub-sectors that are excluded from UKIMA.

Figure 3.1: Goods sector economic activity (percentage of total goods sector employment[footnote 71] by relationship with regulatory difference and the MAPs

A set of four pie charts showing the Goods sector economic activity for each UK nation as a percentage of total goods sector employment for each UK nation by categories of relationship with regulatory difference and the MAPs (Reserved or excepted; Devolved but excluded; and Devolved without exclusion).

The first pie chart shows the Goods sector economic activity for England. 96% of total Goods sector employment in England accounts for Devolved without exclusion; 2.2% for Devolved but excluded; and 1.8% for reserved or excepted.

The second pie chart shows the Goods sector economic activity for Scotland. 97% of total Goods sector employment in Scotland accounts for Devolved without exclusion; 1.5% for Devolved but excluded; and 1.3% for reserved or excepted.

The third pie chart shows the Goods sector economic activity for Wales. 95.1% of total Goods sector employment in Wales accounts for Devolved without exclusion; 2.4% for Devolved but excluded; and 2.5% for reserved or excepted.

The fourth pie chart shows the Goods sector economic activity for Northern Ireland. 98.1% of total Goods sector employment in Northern Ireland accounts for Devolved without exclusion; 1.9% for Devolved but excluded; and 0% for reserved or excepted.

Source:

GB: NOMIS database, 2021 data, count by Employment

NI: Business Register and Employment Survey, 2021 data, count by Employees

Note: Charts are based to be all the same size and are not to scale of the proportion of each nations’ employment figures in the Goods Sector.

Please see Appendix B: Assessment of the regulatory landscape for more information on the relationship with the regulatory difference and the MAPs. However, in interpreting these figures it must be noted that in every UK nation services account for a much greater proportion of employment (and economic output) than do goods. England’s Services sector accounts for 86% of employment compared to only 14% of English employment occurring in the Goods sector. Therefore, England’s services sector is roughly 6 times larger than England’s goods sector. For Scotland the equivalent figures are 83% and 17%; Wales 82% and 18%; and NI 85% and 15%.

Current and upcoming regulatory changes in relation to goods

In our statutory role to monitor the internal market, including regulatory difference that might have impacts on its operation, we have identified an increased level of relevant regulatory developments compared to the 2022 to 2023 annual report. We have also observed an increased number of cases where initial policy development might have indicated potential regulatory difference but ultimately Governments reached a level of alignment to allow UK-wide consultations.

The broad sectors where we consider regulatory difference to be most likely to occur have not changed since the 2022 to 2023 annual report. These include (but are not limited to) environment, food and drink, public health measures, and animal welfare.

Regulatory developments that we focus on in this section have been identified by gathering intelligence through publicly available sources (such as Governments’ publications, announcements), regular stakeholder engagement, submissions to the OIM webform and questionnaires sent to the 4 governments in the UK.[footnote 72] The list presented in this section is not exhaustive. It includes regulatory developments that have a good level of publicly available policy detail to inform our understanding of the potential regulatory difference and/or have a certain level of interest generated by stakeholders. No conclusions should be drawn from the ordering of the presentation of the regulations in this section.

In the 2022 to 2023 annual report, we identified a number of regulatory developments that were affecting, or had the potential to affect, the UK internal market. Of those, 4 (Single-use plastic, Deposit Return Schemes, High fat, salt or sugar food and drink restrictions, and Precision breeding) are covered as case studies in chapter 4. We provide details about those regulations below. All other regulatory developments that we have identified are set out in Appendix C.

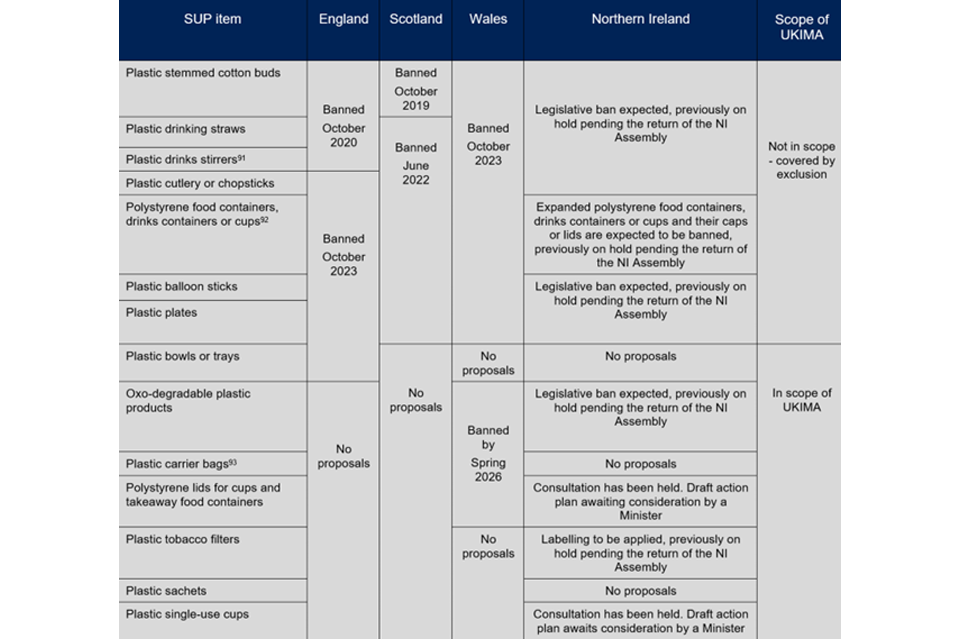

Single use plastic

Measures have been brought into force across all parts of the UK to tackle the issue of single-use plastic waste. At the time of our 2022 to 2023 annual report, the UK Government (in England) and the Scottish Government had implemented bans on the supply and, in the case of Scotland, the manufacture of certain single use plastic products.[footnote 73] Further, an exclusion disapplying the MAPs in relation to these products had been agreed under the Resources and Waste Common Framework.[footnote 74]

Since the 2022 to 2023 annual report, the UK and Welsh Governments have introduced further bans on the sale of single-use plastics.[footnote 75] In England, the UK Government’s new ban came into effect on 1 October 2023 and prohibits the supply of single-use plastic cutlery, balloon sticks, plates, trays or bowls and certain types of polystyrene food containers, drinks containers and cups.[footnote 76] The Welsh Government’s ban came into force on 30 October 2023 and prohibits the supply of single-use: plastic plates, cutlery, drinks stirrers, balloon sticks, drinking straws, plastic-stemmed cotton buds, and cups and food containers made of polystyrene. The Welsh Government’s legislation provides for a ‘second phase’ of its ban, which we discuss in Appendix C, paragraphs C.12 to C.14.

The scope of the bans vary in terms of the single-use plastics they cover. For example, the supply of plastic bowls or trays is only banned in England and is not covered by bans elsewhere in the UK. It will also not be covered by the existing exclusion for single-use plastics and so will be subject to the MAPs for goods.[footnote 77] The bans also vary in respect of the activities that are prohibited. While the bans in England and Wales prohibit the supply of certain products, the existing ban in Scotland also prohibits their manufacture in Scotland.

In Northern Ireland, there are currently no restrictions on single-use plastic items, but the Department for Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs (DAERA) has consulted on policy options for the reduction of single-use plastic beverage cups and food containers, including a ban on the use of these items as one option. DAERA explained to us that regulations restricting single use plastics have not been made in Northern Ireland because there has not been a functioning Assembly, but future restrictions will go beyond those implemented in Great Britain due to obligations under the Windsor Framework. Planned future restrictions are set out in Table 4.1.

Deposit Return Schemes (DRS)

DRS aim to increase recycling rates for drinks containers by incentivising consumers to return them. They work by applying a charge to in-scope containers that can be redeemed when the container is returned. As waste management policy is devolved in the UK, the development and introduction of DRS is the responsibility of the 4 governments across the UK. As noted in our 2022 to 2023 annual report, the 4 governments are working towards development of DRS.

Following publication of the 2022 to 2023 annual report, the UK Government agreed a time-limited exclusion for the Scottish Government’s scheme, which was to be launched ahead of the joint scheme in England, Wales and Northern Ireland.[footnote 78] In May 2023 the UK Government set out that any exclusion would only cover PET plastic, aluminium and steel cans – it would not include glass. The Scottish Government has since delayed the launch of its scheme to bring its commencement into line with the planned launch date (1 October 2025) of the joint scheme in England, Wales and Northern Ireland.[footnote 79] Regulations establishing the joint scheme are not currently available and the Deposit Management Organisation (the scheme administrator) is expected to be appointed by summer 2024.[footnote 80]

A significant difference between the schemes continues to be the materials in scope. In England and Northern Ireland, materials included are polyethylene terephthalate (PET) plastic, steel and aluminium containers.[footnote 81] In addition to those materials, Wales and Scotland also intend to include glass containers in their schemes, though their positions on this are not yet fully confirmed.[footnote 82]

The Welsh Government told us that it remains committed to including glass containers in the joint scheme as it applies in Wales. The Scottish Government has not confirmed whether glass containers will remain covered by its scheme. DBT noted its work with the Devolved Governments to develop interoperable schemes across the UK that do not create unnecessary trade barriers. DAERA highlighted that the implications of differences in scope (for example, glass) have been considered as part of the development of DRS across the UK.

High fat, salt or sugar (HFSS) food and drink

The UK Government has put in place regulations to restrict the promotion of targeted HFSS foods by location and volume price in England under the Food (Promotion and Placement) (England) Regulations 2021.[footnote 83] Restrictions on the location of HFSS products are in key selling locations such as checkouts, store entrances, aisle ends and their online equivalents came into force in October 2022.

Since the 2022 to 2023 annual report, the UK Government’s restrictions on the promotion of HFSS products in England by volume price, such as ‘buy 1 get 1 free’ or ‘3 for 2’, which were set to come into force on 1 October 2023 were further delayed to 1 October 2025.[footnote 84] The Welsh Government is planning to roll out its HFSS promotion restrictions in 2024. This will broadly align Wales with England with respect to location and volume promotion restrictions. Welsh Government also plans to align with England on the same product categories included in legislation. However, the options for including additional restrictions on meal deals, temporary price promotions, and free-standing display units in stores are also being considered.

The Scottish Government confirmed in a statement to the Scottish Parliament plans to consult on the detail of proposed regulation to restrict the promotion of less healthy food and drink where those are sold to the public. The consultation is expected to be published early in 2024.

In Northern Ireland, promotional restrictions on HFSS products are being considered as part of a new draft obesity strategic framework, which has been issued for public consultation.

There is likely to be broad alignment as to what is in scope of the HFSS promotion restrictions across the UK. Subject to the outcome of further consultation by the Scottish Government, potential regulatory difference may arise in relation to meal deals and temporary price reductions being in scope of the HFSS promotion restrictions in Wales and Scotland but not within England.

Precision breeding

In May 2022, the UK Government introduced the Genetic Technology (Precision Breeding) Bill, which alters the definition of Genetically Modified Organisms (GMOs) in England to exclude certain organisms created via precision breeding technologies. The change is intended to simplify the process of obtaining authorisation to market precision-bred plants and animals (PBOs), relative to the requirements for authorising GMOs.

Since the 2022 to 2023 annual report, the Genetic Technology (Precision Breeding) Act 2023 (the Precision Breeding Act) was passed in March 2023 and seeks to remove PBOs from the GMO legislation, introducing legislation to develop an alternative framework to regulate their use, including a register of PBOs. Secondary legislation that will set out how the Precision Breeding Act will work in practice is expected to be in place by the end of 2024.

The Precision Breeding Act applies only to England. Neither Scotland nor Wales are planning to introduce similar legislation and continue to watch the developments at EU level closely, with the Welsh Government indicating to us that it is considering its approach to gene editing. Northern Ireland is required by the Windsor Framework to follow EU regulations on GMOs. Notably, the EU has published its proposal for legislation on plants obtained by certain genomic techniques and their food and feed, which, if enacted, would result in similar legislation to the Precision Breeding Act.[footnote 85] However, this is not likely to occur until after the Precision Breeding Act’s provisions are implemented and operational.