Process evaluation technical report

Updated 17 May 2022

Applies to England

DWP Research Report no. 989

A research report carried out by research consortium led by ICF on behalf of Department for Work and Pensions/Department of Health and Social Care (Employers, Health and Inclusive Employment directorate).

Crown copyright 2021.

You may re-use this information (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence

Or write to:

Information Policy Team

The National Archives

Kew

London

TW9 4DU

Email: psi@nationalarchives.gsi.gov.uk

This document/publication is also available on our GOV.UK website

If you would like to know more about DWP research, please email: Socialresearch@dwp.gov.uk

First published 2021.

ISBN: 978-1-78659-261-3

Views expressed in this report are not necessarily those of the Department for Work and Pensions or any other government department.

Acknowledgements

This study was commissioned by the joint Department for Work and Pensions and Department of Health and Social Care Work and Health Unit. We are particularly grateful to Pontus Ljungberg, Sian Moley, Lyndon Clews, Sarah Honeywell, Caroline Floyd, Rachel Shanahan, David Johnson, Mark Langdon, Anna Bee, Craig Lindsay and members of the DWP Policy Psychology Division for their guidance and support throughout the study.

Dr Adam P. Coutts would like to thank the Health Foundation for the three-year fellowship (Grant ID – 1273834) which enabled him to conduct the research. Many thanks to Liz Cairncross at the Health Foundation who provided support and advice throughout the fellowship. We would also like to thank the Jobcentre Plus staff, Group Leaders, provider representatives and individual benefit claimants who gave their time to participate in the fieldwork.

Views expressed in this report are not necessarily those of the Department for Work and Pensions, Department of Health and Social Care, or any other government department.

Author’s credits

This report was prepared by Tim Knight and Richard Lloyd of ICF Consulting Services Ltd, Christabel Downing and Siv Svanaes of IFF Research, and Dr Adam P Coutts of the University of Cambridge.

Glossary of terms

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Active elements | Components and features embedded within an intervention or course, such as the nature of the learning materials, the quality of the Group Leader and whether a course offers or facilitates social support and interaction with other participants. These combine with the background social, economic and psychosocial characteristics of participants which may result in changes in their health, wellbeing and job search behaviour. |

| Active Labour Market Policy | Active Labour Market Policies (ALMPs) aim to increase the employment opportunities for job seekers and improve matching between jobs (vacancies) and workers (i.e. the unemployed). In so doing ALMPs may contribute to reducing unemployment and benefit receipt via increased rates of employment and economic growth. |

| Active learning techniques | Active learning techniques are based on actively involving participants in a learning activity rather than just requiring them to passively listen. |

| Carer’s Allowance | Carer’s Allowance (CA) is the main welfare benefit for carers and was formerly known as the Invalid Care Allowance. |

| Caseness | A person is described as having suggested case level anxiety or depression if their scores on the Generalised Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) and Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) scales suggests they would exceed the ‘caseness thresholds’ used by Improved Access to Psychological Therapies. Diagnoses of anxiety or depression respectively would be based on a clinical interview and would take account of additional evidence, to which the GAD or PHQ scores may contribute. |

| Cost Benefit Analysis | A cost benefit analysis (CBA) examines all the costs and benefits of the intervention and quantifies them in monetary terms as far as possible, in order to examine the balance of costs and benefits. |

| Disability Employment Advisor | Disability Employment Advisors (DEAs) are people employed by Jobcentre Plus to support and upskill Work Coaches and other members of jobcentre staff to deliver tailored advisory services to disabled people. |

| Employment and Support Allowance | Employment and Support Allowance (ESA) is a benefit for people who have an illness, health condition or disability that affects how much they can work. ESA offers financial support if you are unable to work, and personalised help so that you can work if you’re able to. |

| Financial strain | Financial strain refers to when an individual’s financial outgoings start to exceed their income to a degree that psychologically threatens their sense of self, identity, relationships and/or self-esteem. |

| General self-efficacy | General self-efficacy is the strength of an individual’s belief that they are effective in handling life situations. |

| Group Leader | Group Leaders are the individuals who delivered the Group Work course, using active learning techniques, to participants. |

| Group Work | Group Work is a job search course designed to also enhance self-efficacy, self-esteem and social assertiveness among those looking for paid work. It aims to prevent the potential negative mental health effects of unemployment and help unemployed people back into work. The course, is the application of JOBS II model, originally developed by the University of Michigan, in the UK labour market. |

| Impact on Participants | Impact on Participants (IoP) refers to the analysis of the impact of an intervention based on comparing outcomes for individuals who participated in the intervention with a matched comparison group of individuals who did not. |

| Income Support | Income Support (IS) is an income-related benefit for people who have no income or are on a low income, and who cannot actively seek work. It is mainly for people who cannot seek work due to childcare responsibilities. |

| Initial Reception Meeting | All Group Work participants were invited to an Initial Reception Meeting (IRM) which preceded the course itself. The IRM was designed as an opportunity for participants to meet the Group Leaders who would deliver their course and learn more about what it would involve. |

| Intention to Treat | Intention to Treat (ITT) refers to the analysis of the impact of an intervention based on comparing outcomes for all individuals who were offered the opportunity to participate in the intervention with a control group of individuals who were not offered this opportunity. |

| Jobcentre Plus | Jobcentre Plus (JCP) is a brand under which the DWP offers working-age support services, such as employment advisory services. In the context of this report, ‘jobcentre’ refers to the physical premises in which Jobcentre Plus services are offered. |

| Job-search self-efficacy | Job-search self-efficacy is the strength of an individual’s belief that they have the skills to undertake a range of job-search tasks. |

| JOBS II | JOBS II is the course originally designed by the University of Michigan. Group Work course is the application of JOBS II in the UK. |

| Jobseeker’s Allowance | Jobseeker’s Allowance (JSA) is an unemployment benefit for people who are actively looking for work. |

| Latent and Manifest Benefits | Latent and Manifest Benefits (LAMB) are material and psychosocial benefits associated with being in work such as social interaction, social support, activity, identity, collective purpose, self-worth (Latent benefits) and income (Manifest). |

| Learning and Development Officers | Individuals responsible for delivering training was provided to Work Coaches at the participating Jobcentre Plus offices. |

| Mastery | The mastery outcome was a composite measure taking into account scores on job search self-efficacy, self-esteem and locus of control indexes. It was designed to be a measure of someone’s emotional and practical ability to cope and take on particular situations. |

| Mental Health Issue(s) | Mental Health Issue is a broad term that includes those who have: deteriorating mental health (for example, related to the experience of unemployment); elevated but not clinical levels of a symptom; mental health conditions; or are post-treatment; have symptoms but may not recognise they have a condition; or are aware of their condition/ situation but choose not to disclose. Many individuals with Mental Health Issues are found to struggle with their job search. |

| Psychosocial | Psychosocial indicators concern psychological and social factors that can influence health and wellbeing outcomes. Typical examples of such indicators include social support, employment status, job quality, poverty and marital status. |

| Self-efficacy | Self-efficacy is the strength of an individual’s belief that they have the skills to undertake a task and achieve an outcome. |

| Single Point of Contact | Single Points of Contact (SPoCs) were the designated point of contact in each of the Jobcentre Plus districts in which Group Work was trialed, involved in monitoring volumes, training and delivery. |

| Statistically significant | A statistic derived from a study, such as the difference between two groups, is said to be statistically significant if the size of that statistic has only a low probability of arising by chance alone. The probability of a statistic of that size occurring by chance alone is termed the ‘p-value’. By convention, if the p-value is less than 0.05 then it is stated that the statistic is ‘significant’. |

| Trial Integrity and Support Officers | Trial Integrity and Support Officers were designated DWP staff responsible for monitoring and supporting the fidelity of the DWP input to the Group Work trial. |

| Universal Credit | Universal Credit (UC) is an in and out of work benefit designed to support people with their living costs. Most new claims by people with a health condition or disability are now made to UC. |

| Well-being | Well-being is an individual’s self-report as to whether they feel they have meaning and purpose in their life, and includes their emotions (happiness and anxiety) during a particular period. |

| Work Coach | Work Coaches are frontline Jobcentre Plus staff based in jobcentres. Their role is to support benefit claimants into work through work-focused interviews. |

| Work and Health Unit | The Work and Health Unit (WHU) is a joint unit between the Department for Work and Pensions and Department of Health and Social Care. It leads on the Government’s strategy to support working-age disabled people or those with long-term health conditions, to access and retain good quality employment. |

| Zelen design | The Zelen design is randomised control trial methodology in which randomisation is applied before any potential beneficiaries are informed of the possibility of participating in the intervention being trialed. Only those randomised into the experiment group are informed of the opportunity of participating. |

Executive summary

Introduction

ICF, in partnership with IFF Research, Bryson Purdon Social Research, Professor Steve McKay of the University of Lincoln and Dr Clara Mukuria of the University of Sheffield, were commissioned by the Department for Work and Pensions to undertake a programme of research to evaluate the Group Work trial (Group Work being the UK version of the JOBS II course). This report provides findings from the process evaluation conducted as part of the research. Dr Adam Coutts of the University of Cambridge provided background theoretical and empirical evidence from the international literature regarding the links between Active Labour Market Policies (ALMPs)s, health and wellbeing and findings from observational research and participant observation of the Group Work intervention.

Overview of Group Work/JOBS II

Since 2013 the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) and the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) have been working together to explore joined-up policy approaches and interventions to address the links between unemployment and mental health issues. The Improving Lives: The Work, Health and Disability Green Paper included a commitment to a “Group Work” trial to test whether the JOBS II model improves employment prospects and wellbeing when delivered in the UK context. A Randomised Control Trial (RCT) was undertaken to test the potential effectiveness of the course in a UK labour market context.[footnote 1] The trial ran in five Jobcentre Plus districts between January 2017 and March 2018. It was targeted at benefit claimants who were struggling with their job search and/or were feeling low or anxious and lacking in confidence about aspects of their job search.

The Group Work course delivered in the trial was based on the JOBS II model, originally developed in the United States by the University of Michigan. It comprised five four-hour sessions, delivered over one working week, in a group environment by trained facilitators encouraging participation through active learning techniques. While the course focused on job search skills, the way in which it was delivered was intended to enhance individual self-efficacy, self-esteem and social assertiveness. Participation was voluntary.

Research methodology

This report is based on evidence collected through two main pieces of research:

- A qualitative process evaluation conducted by ICF - a total of 140 interviews were conducted with Group Work provider leads and Group Leaders (15), Jobcentre Plus staff (45), and benefit claimants (80). Of the benefit claimants interviewed, 40 had completed the Group Work course, 20 started but did not complete, and 20 who declined the opportunity to attend.

- Observational research conducted by Dr Adam Coutts - this included interviews with DWP and Jobcentre Plus staff, over 300 hours of participant observation of 17 Group Work sessions, one-day workshop with DWP policy psychologists (2) and Group Leaders (9), and semi-structured interviews with participants (100). Post Group Work health and labour market experiences were explored through semi-structured interviews with a cohort of 25 participants from across the trial sites. Interviews were conducted with this cohort (the same individuals) at five time points (one week, one, three, six and 12 months) post participation.

Quantitative management information and survey data collected through the trial has also been drawn on in some instances to provide further evidence.

Findings on the Jobcentre Plus elements of delivery

Jobcentre Plus Work Coaches were responsible for recognising benefit claimants who would potentially benefit from Group Work and for offering potential beneficiaries the opportunity to participate.

Training to support trial delivery

Training and development activities for Work Coaches, developed and delivered by the DWP’s Policy Psychology Division, took place in two main waves: prior to the trial start in October to December 2016 and after the trial had commenced from March 2017 onwards. Work Coaches were generally positive about the quality, coverage and appropriateness of the training, and reported particular benefits to additional activities such as briefings by Group Work Group Leaders and opportunities to observe delivery. However, it was felt that the timing of the pre-implementation training, and the level of detail provided about the course and what differentiates it from other provision, could have been improved – with less of a gap between the training and the start of the intervention, and with more information to help promote the course to potential participants.

Recognising potential beneficiaries of Group Work

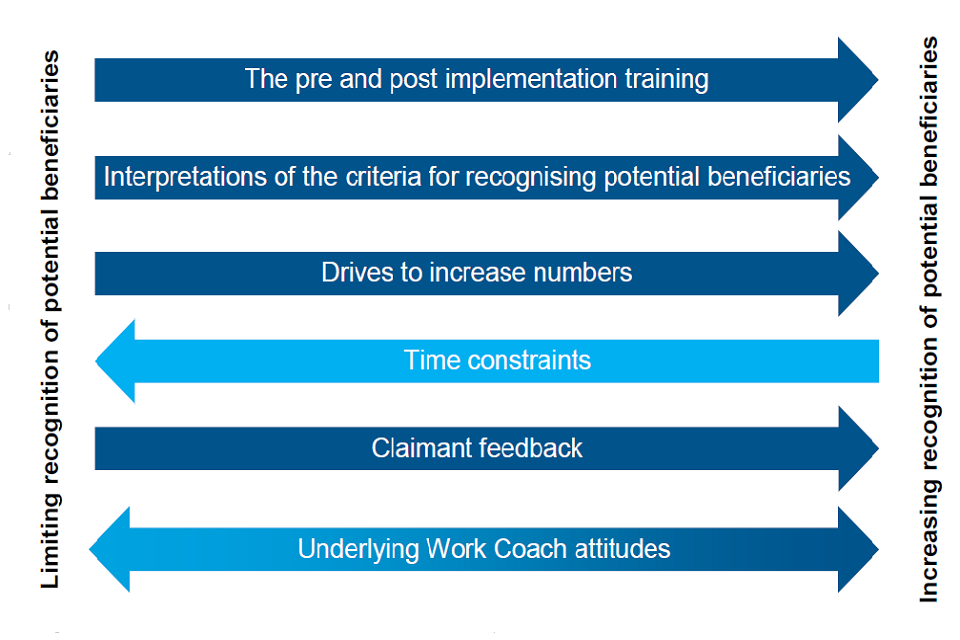

An initial expectation set at the start of the trial was for Work Coaches to recognise 26,000 benefit claimants as potential Group Work beneficiaries, whereas a total of 16,193 benefit claimants were actually recognised by the end of the trial. The main factors (in addition to the training) influencing this were:

- Time constraints - Work Coaches reported that the time required to complete the onscreen survey to collect baseline measures from benefit claimants was the main barrier to them recognising more potential beneficiaries (this survey was specific to the trial and would not feature in any wider roll-out of Group Work).

- Benefit claimant feedback - positive feedback from benefit claimants attending the course encouraged Work Coaches to recognise more potential beneficiaries.

- Interpretations of the criteria for recognising potential beneficiaries - Work Coaches had often understood from the initial training that the course was aimed at those with, or at risk of developing, mental health issues. They thought a broader interpretation of the criteria had been communicated subsequently, which led to them recognising more potential beneficiaries.

- Drives to increase numbers - Work Coaches across the trial districts also reported that they had increasingly been encouraged to consider more and/or more wide-ranging types of benefit claimants as potential beneficiaries.

- Underlying Work Coach attitudes - a minority were said by the jobcentre managers and Group Work leads interviewed to be unenthusiastic about any new initiatives introduced in their jobcentre, not specifically Group Work, and had identified few or no potential beneficiaries.

During the trial the profile of benefit claimants being recognised as potential beneficiaries also changed, with those who were more confident about their job prospects increasingly being identified. Some Group Work provider staff felt this potentially diluted the impact of the trial but equally there was a belief that a mix of participant characteristics was a positive for the group dynamic on the course.

Introducing and explaining Group Work

Evidence from the process evaluation suggests that not all Work Coaches had initially followed the intended process for when they introduced the course to benefit claimants. However, six to nine months into the trial, when the study was conducted, and after further post-implementation training, this process was consistently being followed in most cases.

Overall, 45 per cent of benefit claimants who were offered the opportunity to go on Group Work by their Work Coach accepted (although not all subsequently attended the course). What appeared to most effective in terms of encouraging take up was:

- Emphasising the difference of the course - particularly with benefit claimants who had been on previous Jobcentre Plus provision and potentially saw little value in going on something that superficially sounded very similar.

- Using benefit claimant feedback and international evidence - benefit claimants were receptive to being told about the impact of the course on others, either based on evidence from other countries or about other benefit claimants who had attended.

- Tailoring the explanation to the benefit claimant - for example by picking up on something they had said and using that as a way into introducing the course.

Reasons for accepting or declining the Group Work offer

Reasons for course take-up were most commonly to help find work (including improving job search skills or CV presentation); increase motivation and self-esteem; and, less often, to meet assumed Work Coach expectations or requirements.

Conversely, reasons for declining included the view that the course would not offer them anything new (mainly amongst older and long-term benefit claimants); discomfort with the group setting; health reasons (including medical appointments clashing with the timing of the course); concerns about the physical challenges of travelling to the course venue; and personal commitments such as childcare.

The Group Work course

Prior to starting, benefit claimants attended an Initial Reception Meeting (IRM) to find out more about the course, visit the venue and meet their Group Leaders. Benefit claimants interviewed felt the IRM was well delivered, useful, and commonly confirmed or re-enforced their motivation to attend the course.

Delivery of the Group Work course

Group Leaders, employed by the third party providers, expressed a strong belief in the course, and had attended seven weeks of training which they felt had prepared them sufficiently. They said the course was delivered in accordance with the UK JOBS II manual, although elements had been passed over quickly or occasionally omitted due to time pressures. It was felt there was ‘a lot to cram in’ to the time available, but that sessions could, and should, run over time to allow participants to ask questions.

Some issues were reported with course scheduling, with some benefit claimants having to wait until the minimum cohort size of ten was reached, and on occasion courses were cancelled due to last minute drop-outs. In most cases benefit claimants and Group Leaders reported group sizes of between 12 and 15, in line with the international evidence which suggests group sizes of between 10 and 15.

Benefit claimants’ experiences of the course

Benefit claimants’ experiences ranged from the overwhelmingly positive to the mildly appreciative and, exceptionally, the negative, and appeared to reflect:

- Benefit claimant needs - with the ‘overwhelmingly positive’ being typically those struggling with their job search and either anxious, worried or low in confidence, and who indicated that the course had a positive impact in both these domains.

- How benefit claimants responded to the course - while the vast majority described their experiences positively, the few negative reflections typically related to an aspect of course delivery rather than design.

Looking at experiences of specific elements of the course in more detail, key factors underpinning participant experiences included:

- The facilitation of the course - with the most positive participants highlighting the role of the Group Leaders and their style of delivery, which included: being treated as an equal; establishing an environment which encouraged active participation; the sharing of experiences; and role-modelling (through the Group Leaders’ referent power to motivate or inspire by example).

- Course content - which the majority of participants described as useful and relevant, and provided them with new job search tactics, tools or techniques.

- Course format - where the balance between facilitator-led and interactive elements; the course timing/duration (seen as manageable and an enabler for attendance), and the provision of routine and structure were important factors.

- Group dynamics - which most participants found positive and supportive, underpinned by the realisation that others were in similar circumstances, and allowing experiences of addressing common barriers to be shared.

Course retention and drop-out

Interviews with benefit claimants completing the course, found that the majority of completers had enjoyed attending, due to a combination of the facilitation, group dynamic and resulting mental stimulation; and the perceived relevance and value of the course. Some benefit claimants who left the course early reported in interviews doing so due to competing commitments, such as hospital appointments or emergencies, while others had concluded early in the course that it had little to offer them.

Reported short-term outcomes

Data was collected by the course providers to capture self-reported outcomes for participants at Days 1 and 5 of the course. This showed that a range of positive job search, wellbeing and mental health outcomes were realised over the five days of the course (including 80 per cent who reported an improvement in job search self-efficacy, 66 per cent who showed higher levels of wellbeing/reduced likelihood of depression under the WHO-5 scale, and 63 per cent who scored lower on the PHQ-9 scale for depressive symptoms).

In the follow-up surveys undertaken with a sample of Group Work participants for the quantitative impact evaluation (detailed in the Technical Report on the Impacts of the Trial), most (92 per cent) respondents to the six-month survey who had been on the course reported finding the course useful to them. Over two thirds reported positive effects in terms of their motivation and confidence (including 71 per cent whose motivation to find work had increased, and 62 per cent who felt they were more confident), and over half reported positive effects on different aspects of their job search (from 55 per cent considering the course had helped them move towards work, up to 72 per cent who reported a better understanding of what is needed to find work).

The process evaluation identified five groups of immediate outcomes resulting from the course, commonly reported in tandem, and applied to the majority of completers:

- Increased confidence/self-efficacy - the most widely reported outcome, resulting from the positive reinforcement from Group Leaders, the group dynamics, and the skills, knowledge and techniques acquired.

- Increased motivation - commonly reported, particularly amongst older benefit claimants out of work for some time and those most negative about their job prospects.

- Increased mental health and wellbeing - with the minority of interviewees who disclosed a mental health condition often reporting positive benefits.

- Changes in job search behaviour - including increased volume/intensity of job search; and more creative, reflective, informed and structured approaches.

- Progress into and towards work – a handful of interviewees found work after the course, while others reported taking steps to move them towards employment (e.g. undertaking training and work placements) which they attributed to the increased motivation, confidence and new ideas from the course.

The observational research also included consultations with a cohort of 25 participants at five time points (1 week, and 1,3, 6 and 12 months) post-participation. (totalling 125 interviews). Although the sample size was small), and the findings should be treated as illustrative, the follow-up found:

- Between one week and three months post-participation, most participants felt that their mental health and wellbeing had improved as a result of attending Group Work and these improvements were maintained up to three months post participation regardless of whether they were employed, unemployed or engaged in voluntary work. Overall participants felt that that the resilience and inoculation against set-backs developed on the course had given them ability to deal with the stressors of job search such as application rejections.

- Between three months to a year, those who struggled to find work or lost jobs reported declines in mental health, wellbeing, confidence and motivation. Those who did not enter employment explained how they had lost the sense of a daily routine that had been developed through participation in the course. In general, those who moved into or remained in work reported that that their mental health and wellbeing had remained positive, although this appeared to be partly dependent on the nature of this work. Some reported moving between short-term and/or zero hours jobs and did not appear to experience the same health and wellbeing gains as those in more stable and rewarding employment.

Post-course follow-up

Although the Work Coach training emphasised the importance of discussing benefit claimants’ experience of the course on their return, the absence of formal follow-up procedures in Jobcentre Plus meant that opportunities for reflection, and maintaining the positive momentum generated, were uncommon. Benefit claimants provided mixed experiences of Work Coach follow-up, with some discussing next steps and receiving support to take these forward, while others reported little consultation on their return. There was broad agreement across the Jobcentre Plus staff interviewed in the field that a more formalised approach to follow up was required to help maintain the momentum developed.

The active elements of Group Work

The process evaluation, observational fieldwork and participant observation in each district provided insights into the active elements which appear to lead to changes in participant health, wellbeing and job search behaviour. These are:

- Active element 1: active participation in a group context - the combination of active participation and the group dynamic established was key, with the balance between Group Leader led and the more interactive elements being considered to have worked well by the individuals interviewed. Active participation was facilitated by the Group Work learning materials and sessions such as role playing, mock interviews and group feedback sessions at the beginning and end of each day. Where positive, the group dynamic could lead to benefits including realising that others were in the same position as themselves, the fostering of self-reflection, learning from others on how to address shared barriers, and establishing new friendships and social networks. The access to social support was particularly pertinent and was reported to lead to reduced feelings of loneliness and social isolation with associated self-reported improvements in mental health and wellbeing.

- Active element 2: replicating the time structure and routine of employment - the development of a routine and structure to the day was also a key element, alongside providing participants with constructive activities and a change to what were often described as monotonous daily routines they experienced while being out-of-work. A structured daily format of four hours per day was reported by Group Leaders and participants to replicate or emulate the experience of being in work. This helped participants get back into a more positively focused routine.

- Active element 3: Group Leaders effectiveness and credibility - the role and quality of the Group Leaders was a key element, and they acted as a catalyst for the other active elements of the course. Group Leaders’ influence as role models, and their ability to display behaviours and traits admired by participants, was evident through their ability to motivate by example. Those able to recount recent experiences of unemployment and mental health issues were most able to empathise and appear credible to the course participants.

The findings from the observational research would suggest that in order for the active elements to generate changes in participants’ mental health and wellbeing, they should be supported by the existing Group Work learning materials and sessions, which encourage and facilitate the direct and active participation of job seekers in the course.

Lessons Learned

The evaluation concluded that the implementation of the course overall, and the fidelity of the trial, was methodologically sound. It also identified a number of learnings that could be applied to any future Group Work intervention. These include:

- Continuing to make course participation voluntary as wanting to be on the course and actively choosing to do so appeared to be important.

- Ensuring Work Coach training is aligned with the start of delivery, and with updates being provided on an ongoing basis.

- Emphasising when communicating with staff involved in the referral process, of the importance of recognising participants who are struggling with job search and could therefore benefit from participation.

- Ensuring messaging about the course to benefit claimants is tailored to them and provides detail on the content, coverage and benefits of attending the course, emphasising how it is different from other provision, is aimed at helping them find work and could help address person-specific challenges (using examples from the current trial).

- Exploring whether ongoing medical appointments can be negotiated to allow benefit claimants with long-term health conditions to participate.

- Where provider venues are some distance from or difficult to reach by public transport, exploring the feasibility of using venues closer to or within for example the specific jobcentre catchment areas.

- Exploring the possibility of allowing courses sizes to drop below the minimum, for example, in the case of last minute withdrawals.

- Consideration given to whether the composition of the participants would aid the dynamics of the group.

- Considering how a more reliable and efficient follow-up process could be put in place, which seeks to maintain and build upon the wellbeing gains and positive momentum developed in the course.

- In any wider application of Group Work, and in employability provision more widely, consideration to be given in the course or intervention design to the three active elements identified to be important in the Group Work Trial. This includes considering:

- How the provision can be structured to more closely emulate work?

- How more active participation in labour market interventions can be achieved?

- How the Facilitator role and the characteristics of those Facilitators found to be more effective in the trial can be applied to other provision?

However, for these elements to effectively work they should be accompanied by good quality learning materials.

1. Introduction

ICF, in partnership with IFF Research, Bryson Purdon Social Research, Professor Steve McKay of the University of Lincoln, Dr Clara Mukuria of the University of Sheffield were commissioned by the Department for Work and Pensions in January 2017 to undertake a programme of research to evaluate the trial of Group Work, which is the UK version of the JOBS II programme. Dr Adam Coutts of the University of Cambridge undertook a research placement between July 2016 and June 2020 within the Work and Health Unit in order to carry out his independent research. This report provides technical information and findings from one element of this research: the process evaluation.

The report is one of four reports that have been produced to present the evidence from each element of the research. The other reports are:

- An impact evaluation technical report;

- A cost benefit analysis technical report; and

- A synthesis report.

This chapter provides an initial overview of Group Work, the aims and objectives of the process evaluation, and details of the evaluation methodology.

1.1. Overview of Group Work/JOBS II

Group Work was a trial conducted to test and evaluate the JOBS II model, originally developed in the United States by the University of Michigan, in the UK labour market context. A Randomised Control Trial (RCT), employing a Zelen design, was undertaken to test the potential effectiveness of Group Work/JOBS II in the UK labour market context.[footnote 2] JOBS II is one of several interventions being trialled by the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) and Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) Joint Work and Health Unit to build a strong evidence base of what interventions work best to help those with health issues move into or retain work.

The Group Work trial was targeted at benefit claimants of Jobseeker’s Allowance, Employment Support Allowance, Universal Credit Full Service and Income Support (Lone Parents with child(ren) aged three and over) who were struggling with their job search and/or feeling low, anxious or lacking in confidence with regard to their job search. Participation in Group Work was voluntary, and no sanctions applied if a benefit claimant decided not to attend or if they withdrew part way through. The trial started in January 2017 and finished in March 2018, having achieved 2,596 starts.

The trial operated in five Jobcentre Plus districts – Durham and Tees, Merseyside, Midland Shires, Mercia, and Avon, Severn and Thames, with one or two centrally located provider hubs (where the Group Work course was delivered) and a number of participating jobcentres in each district. The participating jobcentres were responsible for recognising benefit claimants that may benefit from Group Work. Jobcentre Plus Work Coaches administered an onscreen survey with all benefit claimants they thought may benefit from Group Work. On completion of the survey, a randomisation filter was applied. Amongst those randomly assigned to the treatment group and offered the opportunity to go on the course, 45 per cent initially accepted the offer and 22 per cent progressed to start the course.

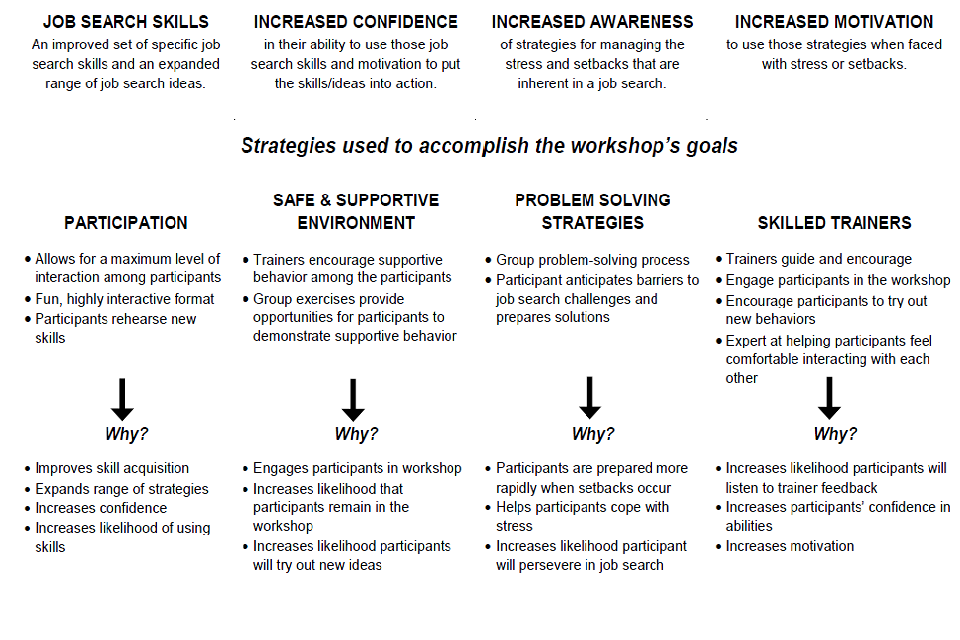

The Group Work course was the application of the JOBS II model developed by the University of Michigan, but adapted for the UK labour market by DWP policy psychologists. Participants were invited to take part in a group-based course delivered in five half-day sessions, averaging four hours a day, over the period of a working week. Although the content of the course was focused on job search skills, the underlying processes by which it was delivered were also designed to enhance the self-efficacy, self-esteem and social assertiveness of the participants. The course was led by trained facilitators using active learning techniques.

1.2. Process evaluation aims and objectives

The process evaluation was undertaken as part of a wider programme of research into Group Work, which also included an impact evaluation and a cost benefit analysis. The Statement of Requirements for the wider programme of research set out the following aims:

“The central research question of this research is to examine:

- “What works to improve employment and health outcomes for people who are out of work and struggling with their job search?”

The primary research questions to be addressed are:

- Did Group Work improve benefit claimants’ employment rates and wellbeing?

- For whom is this support most effective and why?

- Is the support cost effective?”

The specific objectives of the process evaluation, as defined in the Statement of Requirements, were to:

“Assess how the trial processes operate, what are the active elements of the intervention that cause behavioural and health changes and explore key issues which would otherwise not be possible through quantitative techniques.”

Specific areas for investigation for the process evaluation included exploring:

- The operational processes involved in delivering Group Work – referrals, the delivery of the course and relationships between Work Coaches and providers – to identify what has worked well and what less so, and the fidelity of delivery against the prescribed model;

- The experiences of provider staff delivering the course and Work Coaches making referrals to it; and

- The experiences of benefit claimants participating in the course and the benefits resulting for them, and for those declining to attend or not completing the course to explore the reasons for this.

1.3. Methodology

The findings presented in this report are based on two main methodological components:

- Qualitative interviews conducted for the process evaluation with provider staff, Jobcentre Plus staff and benefit claimants, conducted by ICF; and

- A programme of observational and follow-up research conducted by Dr Adam Coutts.

The report also draws upon the findings from the Day 1 to Day 5 survey completed with participants and delivered by Group Leaders. Figure 1.1 provides an overview of the key outcome measures that were used in the evaluation, with additional detail being available in the Impact Evaluation Technical Report.

Figure 1.1: Key measures used in the Group Work evaluation

Work-related measures

* Currently being in paid work.

* Currently being in paid work of 30 or more hours a week (i.e. in full-time work).

* Currently being in paid work that they are satisfied with.

* Currently earning above or below £10,000 per annum.

* Benefit receipt and value of benefit payments.

Job search-related measures

* FIOH (Finnish Institute of Occupational Health) Job Seeking Activity Scale Revised: A measure of how frequently individuals undertake job search activities, and, following revisions, includes two items that measure the number of vacancies applied for and the number of CVs submitted in past two weeks.

* Gaining relevant skills or experience: Measured by whether someone has (a) attended training or courses, (b) done voluntary work, or (c) attended work placements in the previous six months.

* JSSE (Job Search Self Efficacy) Index - Modified: A measure of an individual’s belief that they have the skills to undertake a range of job search tasks.

* GSE (General Self Efficacy) Scale: A broader measure of the strength of an individual’s belief that they are effective in handling life situations.

* Confidence in finding a job: A measure of how confident individuals are of finding a job within 13 weeks.

* Additional job search-related measures used in the evaluation included: their perceived ability to influence the likelihood of finding work, and the influence of personal qualities and experience.

Wellbeing and mental health measures

* WHO-5 (World Health Organisation) Wellbeing Index: A measure of an individual’s wellbeing based on particular feelings experienced in the last two weeks. The WHO-5 can also be used to indicate likely depression.

* ONS4 (Office for National Statistics) Subjective Wellbeing: Four related items measuring individual’s wellbeing based on their subjective happiness, life satisfaction, feeling that life is worthwhile, and anxiety.

* UCLA Loneliness Scale: A measure of an individual’s loneliness.

* LAMB (Latent and Manifest Benefits): A measure of benefits associated with work that can also be used to measure psychosocial deprivation and financial strain.

* PHQ-9 (Patient Health Questionnaire): A measure designed to facilitate the recognition of the most common mental disorders, notably depression.

* GAD-7 (General Anxiety Disorder) Assessment: A measure designed primarily to facilitate the recognition of generalised anxiety.

Wider health measures

* EQ5D-3L (EuroQol Group): A standardised measure of an individual’s overall health.

* EQVAS (EuroQol Group): A measure of an individual’s subjective overall health on that day.

* Visits to a GP in the last two weeks and use of Casualty and Outpatients services in the past three months were also used as measures of overall health.

Details of the two main components of the methodology are provided in the following two sections.

1.3.1. Qualitative interviews with provider and Jobcentre Plus staff and participants - ICF

The process evaluation was based on evidence collected through a programme of in-depth qualitative face-to-face and telephone interviews (undertaken by ICF between July 2017 and January 2018) with a sample of jobcentre and provider staff, and benefit claimants, provided by DWP. The interviewees comprised:

- 15 Provider staff (all the local provider leads and Group Leaders in the trial districts);

- 45 Jobcentre Plus staff (including office managers, office leads/champions, Work Coaches and Disability Employment Advisors in a sample of nine participating jobcentres, with one to two in each trial district); and

- 80 benefit claimants (40 who had completed Group Work, 20 who had started the course but had not completed it, and 20 who had been offered the opportunity to go on the course but declined). The sample included benefit claimants from each of the trial districts and the majority of participating jobcentres within these.

The characteristics of the interview samples are provided in Tables 1.1 to 1.3.

Table 1.1: Provider staff interviewed for the evaluation of the Group Work trial

| Districts | Local leads | Group Leaders |

|---|---|---|

| Durham and Tees | 1 | 3 |

| Merseyside | 1 | 4 |

| Midland Shires | 1 | 2 |

| Mercia | 1 | 2 |

| Avon, Severn and Thames | 1 | 2 |

| Total | 5 | 13 |

*The figures in this table total more than the number of interviews conducted because some respondents were working across more than one of the Group Work trial districts.

Table 1.2: Jobcentre Plus staff interviewed for the evaluation of the Group Work trial

| Districts | Office managers | Group Work leads/ champions | Work Coaches | DEAs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Durham and Tees | 2 | 2 | 8 | 0 |

| Merseyside | 0 | 1 | 4 | 0 |

| Midland Shires | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 |

| Mercia | 2 | 0 | 9 | 0 |

| Avon, Severn and Thames | 2 | 1 | 7 | 2 |

| Total | 6 | 5 | 31 | 2 |

Table 1.3: Benefit claimants interviewed for the evaluation of the Group Work trial

| Characteristic | Count |

|---|---|

| Respondent Type: Completer | 40 |

| Non-Completer | 20 |

| Decliner | 20 |

| District: Avon, Severn and Thames | 28 |

| Durham and Tees | 11 |

| Mercia | 15 |

| Merseyside | 13 |

| Midland Shires | 13 |

| Benefit: JSA | 61 |

| ESA | 12 |

| IS | 3 |

| N/A | 4 |

| Age: 18-30 | 15 |

| 31-49 | 27 |

| 50+ | 38 |

| Total | 80 |

The interviews were conducted with the aid of topic guides (provided in Appendix A) that were tailored to each group and respondent type. Each interview was digitally recorded, with the respondents’ informed consent, and subsequently transcribed. The interview transcripts were then analysed using NVivo to identify key themes, subthemes, groupings and associations in the evidence.

In addition to the interviews with benefit claimants, provider staff and jobcentre staff, eight less formalised discussions and interviews were also conducted with:

- Each DWP compliance manager (who have been involved in the delivery of Group Work training to jobcentre staff and with an ongoing remit to monitor and advise jobcentres on the delivery of the trial); and

- The Jobcentre Plus leads in each of the five districts.

These were conducted after the interviews with benefit claimants, provider staff and jobcentre staff, to feedback the findings from the interviews, collect any reflections on them, and thereby inform the subsequent analysis and reporting of the findings.[footnote 3]

1.3.2. Observational research and follow-up interviews – Dr Coutts

Dr Coutts began a placement as a research analyst in the DWP/DHSC Work and Health Unit in July 2016, and was directly involved in the design and commissioning of the evaluation, the training of Group Work leaders and Work Coaches, and DWP live-trial support forums and trial team teleconferences. Dr Coutts observed the whole participant journey through the field trial from initial attendance at work focused interviews within jobcentres (at the point of where the survey tool was administered and randomisation), reception interviews with Group Leaders, to participation in the course (Day 1 to 5) and after completion.

Dr Coutts also conducted site visits to all districts with trial compliance managers and staff, which comprised semi-structured interviews with: DWP officials, Work Coaches, Single Points of Contact (SPoCs) and Jobcentre Plus managers (total 40); and Group Work Group Leaders (n=14). These interviews helped capture issues with the delivery and implementation of the trial as well as local labour market and socio-economic conditions. A one-day feedback workshop was held with Group Leaders (n=9) and DWP policy psychologists (n=2) in June 2018. This provided an opportunity to test insights and validate observations of Group Work to those directly involved with its implementation.

Ethical approval for the research described in the observation and follow up chapter (Chapter 6) was obtained from the Department of Sociology, University of Cambridge. Given the sensitivity and ‘live’ setting of the trial, interviews were not recorded and field notes taken instead.

Course observations

The field observations began in April 2017, allowing the intervention to bed in (the trial started in January 2017) prior to any external research. A total of 17 week-long Group Work sessions across all five jobcentre districts were observed, representing over 300 hours of observations between April 2017 and April 2018.[footnote 4] On average between 12 and 15 people attended each weekly session, amounting to the observation of over 200 participants in total.

Table 1.4: General characteristics of Group Work participants interviewed within participant observations

| Characteristic | Count |

|---|---|

| Respondent Type: Course participants | 100 |

| District: Avon, Severn and Thames | 20 |

| Durham and Tees | 20 |

| Mercia | 16 |

| Merseyside | 22 |

| Midland Shires | 22 |

| Benefit: JSA | 55 |

| ESA | 22 |

| IS | 23 |

| Age: 18 to 30 | 21 |

| 31 to 49 | 46 |

| 50+ | 33 |

While conducting course observations, semi-structured interviews took place with a convenience sample of 100 participants. Table 1.4 sets out the key characteristics of the participants interviewed, which shows that the sample was broadly distributed by gender, age, duration of unemployment, and reporting or not reporting issues with mental health and wellbeing.

On arrival at each Group Work venue the purpose of the research was explained to the Group Leaders, and then to participants, before consent was sought for the observations on the understanding this was on an anonymous basis.

The qualitative topic guides for participants and Day 1 to 5 survey questionnaires which contain a range of health and wellbeing measures provided an overall framework for conversations with participants and stakeholders. These were used to elicit participants’ views on a range of topics from the links between work, unemployment, health and wellbeing, the latent and manifest benefit measures and how participants felt their health and wellbeing had changed as a result of attending the course. New themes and issues emerged out of these interviews and were further explored with participants across each area. While the topic guides and measures of health and wellbeing were used initially, after a few weeks these were reduced to a series of prompt questions and themes which had developed. The absence of lengthy topic guides also helped to reduce participants’ perceptions that the participant observation was ‘assessing them’ for DWP.

The observations were recorded in writing, with the semi-structured interviews with participants being conducted during break times and before and following the sessions. A typical interview lasted between 30 minutes and one hour, depending on whether it was conducted before or after the course. At the end of each day notes were prepared, including key observations, and with the consent of the Group Leaders and participants, photographs were taken during each session and session materials (such as flipcharts and notes taken by participants) were collected.

The qualitative information gathered from the participant observations and interviews was analysed using the theoretical framework developed and presented in Chapter 2. All materials were reviewed to develop an in-depth understanding of key themes and codes. Themes such as mental health, wellbeing, social isolation, loneliness and the psychosocial characteristics embodied in the Latent and Manifest Benefit (LAMB) scale[^5 ](routine, social support and time structure), were used to code and group quotations and insights from participants, Group Leaders and Jobcentre Plus staff.

Post Group Work interviews

In addition to the course observations,125 semi-structured longitudinal follow-up interviews also took place between April 2017 and April 2019. The cohort is described in Table 1.5 (with the employment status at different points shown as Table 1.6). This was a convenience sample of 72 participants who had completed the course and voluntarily provided their contact details at the end of the Day 5 observations. Due to sample attrition a cohort of the same 25 participants emerged by the end of the fieldwork. These 25 people were each interviewed at one week, one month, three months, six months and 12-months post-participation in order to provide insight into how participants experienced the transition from Group Work into the local labour market and how this affected their mental health and wellbeing. Themes and topics which had emerged during the course observations were explored as well as those covered in the six and 12 months survey questionnaires.[footnote 6]

Table 1.5: Follow up component: Cohort of 25 participants interviewed at one week and one, three, six and 12-months post Group Work participation

| Characteristic | Count |

|---|---|

| District: Avon, Severn and Thames | 7 |

| Durham and Tees | 4 |

| Mercia | 2 |

| Merseyside | 7 |

| Midland Shires | 5 |

| Benefit: JSA | 14 |

| ESA | 6 |

| IS | 5 |

| Age: 18 to 30 | 7 |

| 31 to 49 | 12 |

| 50+ | 6 |

| Total | 25 |

Table 1.6: Employment status of follow-up cohort following Group Work participation

| Employment status | One week to month 3 | Month 3 to month 12 |

|---|---|---|

| In full-time work | 12 | 8 |

| Temporary / voluntary positions | 5 | 7 |

| Unemployed | 8 | 10 |

1.4. The structure of this report

The remainder of this report is structured as follows:

- Chapter 2 sets out the policy and evidence context for the trial, and describes the Group Work course as applied in the UK;

- Chapter 3 provides findings on the Jobcentre Plus elements of the trial;

- Chapter 4 provides findings on the delivery of the Group Work course;

- Chapter 5 provides the findings from the quantitative survey on participants’ experiences of the course;

- Chapter 6 provides findings from the observational research and the active elements of the Group Work course;

- Chapter 7 presents our conclusions and lessons learnt from the trial.

The report also features one appendix which contains the topic guides used in the qualitative ICF fieldwork.

2. Policy and evidence context

This chapter sets out the policy and evidence context to the UK JOBS II trial. It summarises pre-existing evidence on the links between unemployment and mental health and on the effectiveness of active labour market policies (ALMPs) in terms of generating employment, health and wellbeing outcomes.[footnote 7] It then provides evidence from international studies of the JOBS II model, in terms of how and for whom it has been found to be effective.

2.1 The ‘genesis’ of Group Work: tackling the relationship between unemployment and mental health

Unemployment and mental health concerns are at the forefront of the current national policy agenda in the UK (Department for Work and Pensions, 2016 and 2017). Since 2013 the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) and the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) have been working in conjunction to explore more joined-up policy approaches and interventions to address the links between unemployment and mental health issues. A key aspect of this approach, has involved using the best available evidence on interventions and designing and testing field trials of interventions that can help people get back to work, promote wellbeing and help reduce mental health issues. These have bolstered policy and academic interest into how mental health and wellbeing are affected by non-health sector policy interventions such as employability provision, ALMPS and back-to-work programmes.

The Government’s disability, health and employment strategy highlighted the prevalence of mental health issues in the population (DWP, 2013). Research evidences shows that at any given time around one in six people has a common mental health condition, such as anxiety or depression (McManus et al., 2016). People with mental health issues are also shown to fare worse in terms of labour market participation:

- The Annual Population Survey (April 2018 to March 2019) showed the employment rate of disabled people aged 16 to 64 who had any mental health condition as their main health condition was 43.6 per cent, compared to 51.4 per cent of all disabled people and 81 per cent of non-disabled population;[footnote 8] and

- Quarterly data to February 2020 shows that 50 per cent of Employment and Support Allowance claimants have a mental and behavioural disorder as their primary registered condition.[footnote 9]

More widely a robust evidence base exists which shows that unemployed individuals are more likely to experience common mental health conditions such as anxiety and depression than those in employment (Kim and Von dem Knesebeck, 2015; Murphy and Athasanou, 1999; Paul and Moser, 2009). In addition, these conditions can themselves hinder attempts to re-enter the labour market after a period of unemployment. Research has found that mental health conditions and low self-esteem can adversely affect job search behaviour and motivation via reduced confidence, making it less likely people will enter employment (Waters and Moore, 2002; Zabkiewicz and Schmidt, 2007; Vinokur and Schul, 2002; Van Hooft et al., 2012). High quality and appropriate re-employment have been shown to counter some of the negative mental health and wellbeing effects of unemployment (Coutts et al., 2014; McKee-Ryan et al., 2005).

2.2. ALMPs, health and wellbeing: an evidence base

Empirical evidence on labour market status, mental health and wellbeing has largely focused on the effects of employment, redundancy, long-term unemployment, or ‘bad’ jobs[footnote 10] and working conditions. However, the evidence is unclear concerning the health and behavioural impacts of the transition between unemployment and employment resulting from participation in employability provision and ALMPs, why these impacts occur, what are the active elements[footnote 11] involved, and who is most responsive in terms of improved mental health, wellbeing and job outcomes (Coutts, 2009; Coutts et al., 2014; Sage, 2014).

A range of ALMPs exist. Their overall purpose is to increase employability and reduce the risk of further unemployment. This is achieved via interventions which offer job search assistance, basic skills and vocational training, as well as wage and employment subsidies. They aim to enhance human capital, labour supply and the general functioning of local labour markets (Coutts, 2009; Kluve et al., 2017). The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) define ALMPs as ‘..all social expenditure (other than education) which is aimed at the improvement of the beneficiaries’ prospect of finding gainful employment or to otherwise increase their earnings capacity. This category includes spending on public employment services and administration, labour market training, special programmes for youth when in transition from school to work, labour market programmes to provide or promote employment for unemployed and other persons (excluding young and disabled persons) and special programmes for the disabled.’[footnote 12]

Most studies which examine the impacts of ALMPs and the employability provision interventions used to deliver them focus on what are traditionally considered the more tangible economic impacts or outcomes such as job entry rates and time off benefits (Coutts, 2009). Major systematic reviews of hundreds of ALMPs conducted across social and economic contexts have found mixed and small effect sizes in terms of job outcomes (Card et al., 2018; Kluve et al., 2017). Specifically on average ALMPs have relatively small effects in the short-term (less than a year post-programme), but larger positive effects in the medium run (1-2 years post-programme) and longer run (2+ years).[footnote 13] In a meta-analysis of over 800 observational and experimental studies of ALMPs for the general unemployed populations, Card et al. (2018) found short-term (less than a year after the intervention) effects of skills training on an individual’s employment. As noted this effect has been found to multiply over time, leading to around six to seven percentage point increase in employment outcomes over two years.

A major gap identified by Coutts (2009) and Kluve et al. (2017) is the limited reporting of the health and wellbeing impacts of these interventions and what are commonly referred to as the theories of change or active elements embedded within a policy intervention, i.e., what is going on within an intervention that influences health, wellbeing and behaviour changes among those who participate. The small body of international evidence that exists suggests that participation in employability provision and ALMPs can have positive effects on mental health and subjective wellbeing (such as on individual confidence, motivation and self-efficacy).[footnote 14] A recent Cochrane systematic review of health-improving interventions for obtaining employment in unemployed job seekers (Hult et al., 2020) found that out of 15 trials reviewed, ALMPs or ‘therapeutic interventions’ as the authors define them ‘may increase employment, but the evidence is very uncertain’. Further they report ‘there may be no differences in the effects on mental health and on general health. Combined interventions that included therapeutic methods and job-search training probably slightly increase employment compared to no intervention’ (Hult et al., p 2). The review did not report or explore what active elements or intervention processes may be responsible for these effects.

There is also little evidence from the United Kingdom (See Coutts 2009; Andersen, 2008; Sage, 2015b, 2015a; Wang, et al., forthcoming for exceptions), and no major studies involving randomised control trial (RCT) designs. The evidence base in general provides little indication as to what are the active elements embedded within interventions which can generate a change in job search behaviours, health and wellbeing, and subsequently enhance an individual’s employability and therefore generate employment outcomes. Given that hundreds of thousands of people move through employability provision every year in the UK there is a need to understand when ALMPs work, why and for whom.

2.3. How ALMPs may affect health, wellbeing and job search behaviour

In order to understand how ALMPs may affect the health, wellbeing and behaviour of participants, Coutts (2009) proposed a framework combining theories and evidence from work psychology, self-efficacy and the importance of social support, networks and social isolation in maintaining health and wellbeing.[footnote 15] It follows that the experience of unemployment may reduce a person’s access or exposure to a set of psychosocial[footnote 16] characteristics of employment. These are referred to as the latent and manifest benefits of employment, which are important for maintaining and protecting mental health and wellbeing (Kovacs et al., 2019; Waters and Moore, 2002). According to Jahoda (1982) examples of latent benefits include time structure, routine, social activity, social contact and support, collective purpose, regular and purposeful activity and identity (Coutts, 2009). The manifest benefits refer to income and wages.

It is proposed that ALMPs may be able to replicate these psychosocial characteristics of the employment experience, which potentially influence changes in health and wellbeing. As Coutts (2009) notes ‘people are neither employed nor unemployed but occupy an intermediate stage in terms of their labour market status. Within ALMPs, participants are subject to both the negative psychosocial characteristics of being unemployed (such as low income) and positive psychosocial aspects such as a routine and activity, as well as the ALMP active elements such as the type of provision and course content that are used to ‘help them into the labour market’.

For instance, unemployed job seekers frequently report feeling socially isolated and lonely. As the existing evidence base demonstrates, limited social support and social isolation is linked to a range of negative health and wellbeing outcomes (Berkman et al., 2000). The employability provision or ALMP environment provides a context in which the unemployed job seeker is able to meet people and increase social contact, which can reduce feelings of social isolation and loneliness.

Further, Coutts (2009) and Price and Vinokur (2014) propose that interventions themselves are embedded with specific active elements which generate behavioural, health and wellbeing changes. Firstly, ‘process effects’ (Helliwell, 2011) such as the quality of the ALMP trainer or leader in terms of their skill levels and overall credibility has a significant impact on encouraging and supporting participants to develop their own skills and actively participate which can lead to increased confidence and motivation. Secondly, the type of intervention content and material such as whether it involves basic skills, vocational training, role play, job search and networking. Each of these approaches varies in the degree to which they are able to facilitate active participation or promote the more instructive or teacher-led approach which traditionally dominates employability provision. Thirdly, the characteristics of the participants themselves may function to encourage people to support each other and share challenges they face in job search or their daily lives, such as whether they share similar backgrounds and experiences, similar levels of mental health and wellbeing and duration of unemployment. This may have a group psychotherapeutic effect and encourage participants to form bonds and social support which can help them identify ways to overcome challenges, deal with personal issues, setbacks and rejections in job search and reduce feelings of social isolation and loneliness.

2.4. The policy response: test and learn

In order to look at how to improve employment and health prospects for people with common mental health issues the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) and the Department of Health (DH), now Department for Health and Social Care (DHSC), jointly commissioned Psychological Wellbeing and Work: Improving Service Provision and Outcomes (Van Stolk et al., 2014).

The report concluded that the interaction between mental health and employment is complex and no ‘one size fits all’ approach is appropriate. It argued for more integration between existing treatment and employment services, timely access to coordinated treatment and employment support and application of evidence-based models of support. Four models were proposed for further investigation:

1. Using group work in employment services to build self-efficacy and resilience to setbacks that benefit claimants face when job seeking, based on the JOBS II programme, and which had been advocated by the DWP Policy Psychology Division.

2. Embedding vocational support, based on the Individual Placement and Support model (IPS), in the Improving Access to Psychological Therapies programme (IAPT) or other suitable psychological therapy services.

3. Using Jobcentre Plus-commissioned, third-party provision of combined telephone-based psychological and employment related support for the JSA group or ESA group before they enter the Work Programme.

4. Providing access to online mental health and work assessments and support.

Based on the first three recommendations, a series of small-scale feasibility pilots were established to examine the most effective design of the pilot interventions, plus the most effective delivery mode. Group Work, which is based on the JOBS II model, was a week-long intervention aimed at JSA claimants who were struggling with their job search. It was piloted between August and December 2014 in the two Jobcentre Plus districts of Thames Valley and Gloucester and the West of England.

Findings from the evaluation of the pilot (Callanan et al., 2015) indicated that the intervention had some impacts on participants’ mental health, wellbeing and employment, and should be scaled up in order to robustly test the intervention across different labour market contexts. The pilot study recommended certain changes which were implemented in the final trial. This included training for Work Coaches to enhance their understanding of who was suitable for the intervention, changes to the documentation to reflect language and cultural differences in the UK, and avoiding the use of the term ‘psychological’ support.

2.5. JOBS II intervention model: Evidence from international studies

The JOBS II studies developed in the United States and replicated in a range of other nations are currently the best available evidence on the impact of employability provision on health and wellbeing, and provide the foundation for the establishment of the Group Work intervention.

Developed at the University of Michigan in the United States, the JOBS programme is a theory and research founded intervention originally designed to meet the employment needs of those who had recently experienced job loss and to prevent the onset of mental health issues, particularly depression for those at risk. Alongside specialised job search skills training, the JOBS programme included a range of elements designed to promote self-efficacy, coping strategies and provide ‘inoculation against setbacks’ in the job search process. The programme was tested in two large randomised trials (JOBS I and JOBS II) in the United States and has since been adapted and implemented in trials and pilots across five countries (United States, Ireland, China, the Netherlands and Finland) with positive results in terms of health, wellbeing and job outcomes for some participants across different economic and welfare settings.

JOBS I and JOBS II has created a series of academic publications over the past twenty plus years exploring the impacts and experiences of the intervention across a range of country contexts. These studies have examined the effects of the intervention on a range of mental health, wellbeing, behavioural and employment outcomes. In addition to the initial evaluation (Vinokur et al., 1995), two seminal papers are: Vinokur et al. (2000) in the United States and Vuori et al. (2005) in Finland.[footnote 17] The US study followed up data on 1,801 participants from the earlier 1995 randomised field experiment (JOBS) to assess long-term effects (after two years). The Finnish study assessed outcomes (at six months) of a similar randomised field study of 1,261 unemployed jobseekers. The main differences between the studies, as shown in Table 2.1, were recruitment and eligibility, in particular, the length of time the sample had been unemployed (United States: mean = 4.11 weeks since job loss and no longer than 13 weeks, Finland: 28 per cent of the sample had been unemployed for more than 12 months) and the targeting of specific groups (US: those recently becoming unemployed, and Finland: aimed at previously employed office workers).

Key findings from the US and Finland studies

The US JOBS II study by Vinokur et al. (2000) found that after two years post-programme the experimental group had significantly higher paying jobs and higher quality jobs. They were working more hours and earning greater levels of income, although there was no improvement in the “stability” of the jobs obtained.

In terms of mental health and wellbeing, participants who were assigned to the programme experienced a small but significant overall reduction in depressive symptoms. They also reported improvements in a sense of control and feelings of mastery, which are proposed to be protective for mental health[footnote 18] (Vinokur et al., 2000). Those who participated in the US JOBS II were significantly less likely to experience episodes of depression and mental health issues.

In the Finnish trial of JOBS II (Vuori et al., 2005), participants were more likely to be in stable employment[footnote 19] post-programme at six months and two years later. Participants experienced reduced psychological distress levels compared to the control group. Those who had been unemployed for a moderate length of time (three to 12 months) appeared to benefit the most; they were more likely to have entered a stable job compared to both long-term and recently unemployed groups.

In both studies those at greatest risk of depression and reporting mental health issues at baseline benefited the most (in terms of health and wellbeing) from participating.

Table 2.1: Details of previous JOBS II evidence, methodologies and sample sizes

| Methodology | United States (US) Vinokur et al. 1995 (JOBS) | United States (US) Vinokur et al. 2000, 2002 (JOBS II) | Finland Vuori et al. 2002; Vuori and Silvonen, 2005 | Group Work Trial UK |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample characteristics | Eligible participants were those who were unemployed on average for 13 weeks, from Michigan Employment Security Commission in the US and shown no preference to treatment or control programme. Mean age = 35.9 years Proportion of men = 46 per cent Data was collected in four waves: t1: A pretest questionnaire. t2: 1 month after the intervention. t3: 4 months after the intervention. t4: 32 months after the intervention. |

Eligible respondents were those unemployed for less than 13 weeks, still looking to find a job, and not expecting to retire within the next two years or to be recalled back to their former jobs in four offices in Michigan Employment Security Commission in the US. Mean age = 36.2 years Proportion of men = 45 per cent Data was collected in four waves t1: pre-test questionnaire. t2: 2 months after the intervention. t3: 6 months after the intervention. t4: 2 years after the intervention. |

Eligible participants were unemployed job seekers or had received a termination notice and were searching for a job between September 1996 and June 1997. Implemented during a financial crisis in Finland and high unemployment rates. Mean age = 37 years Proportion of men = 22.2 per cent Duration of unemployment: 28 per cent had been unemployed for over 12 months. Characteristics: sample is higher educated and contains more females than the average unemployed workers. Data was collected in four waves: t1: A pre-test questionnaire. t2: 2 weeks after entry, t3: 6 months after completion t4: 2 years after completion |

Eligible participants were those in receipt of unemployment benefits, struggling with their job search in five jobcentre districts in the UK. 51 per cent of the treatment group reported ‘never worked’, and 21 per cent were last in work over two years ago. Mean age = 40.9 years Proportion of men = 63 per cent Data was collected in four waves: t1: Day 1: start of intervention t2: Day 5: end of intervention t3: 6 months after the intervention t4: 12 months after the intervention |

| Sample size at baseline | Treatment group = 752 Control group = 379 |

Treatment group = 1249 Control group = 552 |

Treatment group = 629 Control group = 632 |

Treatment group = 11,900 Control group = 4,293 |

| Outcome measures | Past job and its quality, attitudes toward work and job seeking, job seeking intentions and behaviour, job-search self-efficacy, mental health and wellbeing, social support and personality dispositions (self-efficacy, locus of control and self-esteem), reemployment, wage rate and job quality. | Depressive symptoms, role and emotional functioning, financial strain, mastery (job-search efficacy, locus of control and self-esteem), sense of self-worth/social undermining, job-search motivation, reemployment. | Re-employment and labour market engagement, job satisfaction, depressive symptoms measured via a Finnish scale based on the Hopkins Checklist and self-esteem measured with a 10-item measure. | WHO-5 wellbeing index, psychological stress (PHQ-9 depression assessment, GAD-7 anxiety assessment), ONS 4, LAMB-12, UCLA loneliness index, general self-efficacy, EQ-5D-3L and EQ-VAS health index. Job search motivation, job search self-efficacy, employment status, full- or part-time, salary, satisfaction with paid work, benefit receipts. |

| Main findings | (1) One-month follow up of intervention, 33 per cent of participants were re-employed, compared with 26 per cent in control group. Four-month follow up of intervention, 59 per were re-employed, compared with 51 per cent in control group. (2) At one and four months follow up the experimental group reported significantly higher levels of self-efficacy in their job seeking. (3) At one and four months follow up reemployed scored significantly lower on anxiety, depression and anger. (4) At the 32-months follow up, the experimental group had higher earnings compared to the control. In addition, they worked more hours and had more stable work. (5) During the 32-months follow up, the intervention had a preventive impact on both incidence and prevalence of depressive symptoms especially among the high risk people (i.e. those suffering from severe depressive symptoms): 25 per cent for experimental groups compared with 39 per cent for control groups. |

(1) Two years after the JOBS workshop, the intervention participants had significantly higher levels of reemployment and monthly income, lower levels of depressive symptoms, lower likelihood of experiencing a major depressive episode, and better role and emotional functioning compared with the control group. (2) Baseline job-search motivation and sense of mastery had both direct and interactive effects on reemployment and mental health outcomes of participants. (3) It was found that those who had initial low levels of job-search motivation and mastery benefited the most. Additional follow-up work at the two-year point with participants from the treatment group recorded lower levels of depressive symptoms and better mental health, and higher levels of working hours, more months working 35 plus hours compared with control group. |