Part 1 – Introduction

Updated 23 September 2022

Ministerial Foreword

I want pensions to be safer, better and greener. Therefore, tackling the threats posed by climate change remains a key priority for myself and the wider government. For me in my role as Minister for Pensions and Financial Inclusion, this means ensuring that trustees identify, assess and manage the climate risk they are exposed to in order to safeguard their members’ savings. That is why I secured amendments to the Pensions Schemes Bill to allow the government to require pension scheme trustees to fully consider and disclose their climate-related financial risks and opportunities in line with recommendations by the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD).

We are moving quickly, and the government has already consulted on its policy to ensure occupational pension schemes have in place – and report on – effective governance, strategy, risk management and accompanying metrics and targets for the identification, assessment and management of climate risks and opportunities. We are now consulting on draft regulations. Subject to Parliamentary approval, requirements will apply to trustees of the largest schemes from 1 October this year.

That is why I am delighted that this guidance is being published ahead of government’s measures coming into force. I recognise that these measures will present a number of challenges which are relatively new and complex to trustees. In addition to our Statutory Guidance, which will set out a range of activities trustees can undertake to robustly meet such challenges, I believe the guidance will be an incredibly helpful resource for trustees working towards meeting their new duties.

It is still my expectation however that trustees should not need statutory requirements to begin meaningful action. This guidance will be of use to all trustees whether they are soon to be in scope of the new requirements or are just starting out on this journey. Government will be reviewing the impact of our climate change governance and reporting measures in 2023 with a view to extending them out further to smaller schemes. With that in mind trustees of those schemes should start looking at this guidance now and begin building their knowledge and understanding.

I have consistently espoused the need to pull together to address the scale of the challenge that climate change presents, and for industry to play their part. I would therefore like to conclude by praising industry for their work on this guidance. Thank-you to Stuart O’Brien from Sackers for leading this work and many others in the pensions industry and civil society who have given up their time in order to contribute to producing such comprehensive guidance for trustees. I would also like to offer special thanks to The Prince’s Accounting for Sustainability Project (A4S) and their interviewees for providing some real-life case studies of this work being conducted. Peer-to-peer learning undoubtedly has a significant role to play in advancing this work.

I call on trustees to use this resource as government seeks to revolutionise pension investment, making saving better, safer and greener.

Guy Opperman MP

Minister for Pensions and Financial Inclusion

Foreword by the Chair

Climate change poses an existential threat to our planet and society. We all try to do our bit to reduce our impact on the environment, but the task required to avoid dangerous levels of temperature increases is a collective challenge.

Against this backdrop it might be difficult to see the role trustees of UK pension schemes have to play. Most trustees will have acknowledged the financial risk of climate-related risk on their pension schemes but this is just one of a myriad of issues that trustees need to spend time considering. With a range of potential climate scenarios and highly complex impacts reaching far into the future, few trustees will have developed concrete plans to quantify and address the risks of climate change or capitalise on the opportunities of the transition to a net zero carbon economy.

However, trustees must act. Subject to consultation and approval by Parliament, regulations pursuant to changes made by the Pension Schemes Bill will come into force in October 2021, requiring trustees of larger schemes to take specific actions to integrate the consideration of climate-related issues into their governance processes and to make annual public disclosures. Trustees not in scope for the changes in October 2021 are still required to disclose their climate policies in their statements of investment principles. In any event, trustees should not approach the regulatory requirements as a tick-box exercise. Policies and risk management processes need to be meaningful for trustees to meet their overarching fiduciary and trusts law duties, taking account of climate change as a material financial issue.

The Pensions Climate Risk Industry Group (PCRIG) was formed in 2019 to provide cross-industry guidance to help pension trustees meet their legal responsibilities. And, following consultation on draft guidance in March 2020, it is with great pleasure that we launch this final version of our guide.

This guide is designed to help trustees of all schemes by providing practical steps to help them comply with their duties to manage climate-related risks. Many schemes will be subject to specific regulatory requirements pursuant to changes made by the Pension Schemes Bill. For these schemes the guide is designed to complement those regulatory requirements and accompanying statutory guidance. For schemes not yet subject to these specific statutory requirements the guide should still provide a starting point for the integration of climate issues into existing trustee governance processes. Based upon the TCFD recommendations, the guide aims to provide a useful approach for all trustees assessing climate-related risks, enabling trustees to set a more resilient investment strategy for the benefit of their members.

Finally, over the page is a list of acknowledgments of all those members of PCRIG who have so generously given of their time to produce this guide. Without the contributions of each and every member of the group, production of the guide would not have been possible. In addition to this many more have provided their input along the way and provided their responses to the consultation in 2020 and I am grateful to all the trustees and professional advisers who have contributed and shared their wisdom and experience.

Stuart O’Brien, Partner

Sacker & Partners LLP

Acknowledgements

For the review of the consultation feedback, and the editing of the final draft, the members of the Pensions Climate Risk Industry Group have been:

| Stuart O’Brien (Chair) | Sacker & Partners LLP |

| Alexander Burr | Legal and General Investment Management |

| Kate Brett | Mercer |

| Millie Brown | Department for Work and Pensions (until December 2020) |

| Caroline Escott | RailPen |

| David Farrar | Department for Work and Pensions |

| Andrew Harper | Sacker & Partners LLP |

| Paul Hewitt | Vigeo Eiris (until December 2020) |

| Claire Jones | LCP |

| Amanda Latham | Barnett Waddingham |

| David Page | BMO Global Asset Management |

| Kerry Perkins | Accounting For Sustainability |

| Tom Rhodes | Department for Work and Pensions |

| Phoebe Wright | Department for Work and Pensions (until November 2020) |

1. How to use this guide

Key considerations

- this guide aims to help trustees evaluate the way in which climate-related risks and opportunities may affect their strategies by making use of the recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD)

- subject to consultation and approval by Parliament, regulations pursuant to changes made by the Pension Schemes Bill 2019-21 will come into force in October 2021, requiring trustees of larger schemes and authorised master trusts – and, when established, authorised Collective defined contribution (DC) schemes – to take specific actions to integrate the consideration of climate-related issues into their governance processes and to make annual public disclosures. The guide is designed to complement those statutory requirements for schemes in scope as well as providing a starting point for the integration of climate issues into existing trustee governance processes for schemes of all sizes

- trustees should familiarise themselves with the framework of this guide and the separate “Quick Start Guides”

- Part II of the guide sets out a suggested approach for the integration and disclosure of climate risk within the typical governance and decision-making processes of pension trustee boards. This focuses on how trustees might usefully consider climate-related risks and opportunities

- whilst the guide covers disclosure (as recommended by the TCFD), it is recognised that for many pension schemes this will be a new exercise, which may require new processes and information. Trustees may wish to use this guide to prioritise the adoption of robust governance procedures as a first step, with public disclosure as a second step. Where trustees do disclose, this guide seeks to align trustee governance and decision-making processes with the TCFD recommended disclosures, and references anticipated regulations pursuant to changes made by the Pension Schemes Bill 2019 to 2021

- Part III of the guide contains technical details on recommended scenario analysis and metrics that trustees may wish to consider using to record and report their findings, including if required to by regulations made pursuant to new powers in the Pension Schemes Bill 2019 to 2021. Whilst many trustees will ask their professional advisers to work through the detail and advise on implementation, the section contains freely available tools that trustees may use themselves

1.1. Introduction

1. The Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) is an independent body which has developed recommendations on how organisations can identify and disclose information about climate-related financial risks and opportunities. More detail on the TCFD’s recommendations is set out in Chapter 4.

2. This guide provides a useful framework, based on the TCFD’s recommendations, to help trustees of occupational pension schemes evaluate the way in which climate-related risks may affect the strategies and plans of the pension schemes they are responsible for, and then report on this activity to their stakeholders in a consistent and transparent manner.

3. The guidance is aimed at trustees of private sector schemes, but sections of the guidance may be of interest to others, including managers of funded public sector schemes.

1.2. Intended audience

4. Government has set the expectation that all listed companies and large asset owners, including occupational pension schemes, will disclose in line with TCFD recommendations by 2022.

5. The government is expected to use new regulation making powers in the Pension Schemes Act 1995 (inserted by provisions in the Pension Schemes Bill 2019 to 2021) to introduce new climate change governance and reporting requirements for trustees of schemes with over £1 billion in net assets (as well as authorised master trusts and authorised collective DC schemes (once established). It is expected the requirements will implement the TCFD recommendations on disclosure of governance, strategy, risk management and accompanying metrics and targets as well as requiring trustees to carry out underlying activities for the identification, assessment and management of climate risks and opportunities, which will enable them to make those disclosures.

6. Whilst smaller schemes may not yet be caught by these requirements most trustees are subject to statutory requirements to specify and disclose their policies on climate change and to carry out risk assessments (see Chapter 3) for further detail). This guide provides a suggested framework that all trust-based occupational pension schemes may find useful in order to develop such policies and integrate them into trustee decision-making. The framework may further assist trustees in demonstrating compliance with their fiduciary and trusts law duties to take account of financially material factors and to act prudently.

7. Part III of this guide contains technical detail on the climate change scenario analysis that trustees may wish to consider and the decision-useful metrics that trustees can measure, as well as referencing anticipated requirements pursuant to the government’s proposed regulations on climate change governance and reporting. Whilst some of this may be of greatest use to professional advisers and pension scheme providers, it is recognised that the resources available to each pension scheme will vary by scheme size, budget, type of benefits provided and the maturity of the scheme. Part III in particular, suggests some freely available tools that trustees can use for basic scenario analysis.

1.3. Structure of this guide

8. This guide is structured sequentially based on the way a pension trustee board might typically approach decision-making. Part I sets out the legal requirements for pension scheme trustees to consider climate-related risk in their decision-making and more detail on the recommendations made by the TCFD.

9. Part II sets out a suggested approach for the integration and disclosure of climate risk assessment in the typical governance and decision-making framework of pension trustee boards, indicating (where applicable) how these align with the TCFD recommended disclosures. Guidance is also provided on how trustees should approach stewardship on climate-related issues, including exercising voting rights, reviewing progress and communicating with members about the actions taken. It also provides some additional points for defined benefit schemes to consider, including the incorporation of climate-related risks into the employer covenant assessment.

10. In Part III, the guide sets out how trustees can analyse the resilience of their scheme to different climate-related scenarios, including the transition to a lower-carbon economy. Models are provided for trustees to assess resilience both qualitatively and quantitatively.

11. In Part IV, recommendations are made as to the metrics and target which trustees can use to help to measure and manage climate-related risk exposure.

12. Trustees can choose which set of recommendations best suits your scheme’s circumstances and take account of this guide accordingly.

2. Introduction – Understanding climate change as a financial risk to pension schemes

Key considerations

- all pension schemes, regardless of size, investments or their time horizons, are exposed to climate-related risks. When considering the financial implications of climate change, trustees should understand the different implications of transition risks and physical risks on their investments

- as investors, most schemes have capital at risk as a result of the low carbon transition. In addition, many defined benefit schemes are supported by employers or sponsors whose financial positions and prospects are dependent on current and future developments in relation to climate change

- the Paris Agreement aims to ensure that the increase in average temperatures above pre-industrial levels is kept to ‘well below’ 2°C by 2100 and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C. The longer the delay in climate policy action, the more forceful and urgent any regulatory policy intervention will inevitably be and the more severe the likely impact will be on companies and investors

2.1. The financial risk of climate change

13. The world’s climate is already 1°C warmer today[footnote 1], on average, than relative to pre-industrial times and the rate of increase is roughly ten times faster than the average rate of ice-age-recovery warming. The dominant cause for this is extremely likely to be the rapid increase in anthropogenic emissions of greenhouse gases which are now at concentration levels unprecedented in at least 800,000 years.[footnote 2]

14. The average temperature rise conceals more dramatic changes at the extremes and is already having disruptive effects. It is a risk multiplier, exacerbating existing issues with energy, resource and food security and increasing the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events. This is made worse by the size of, and inertia in, the climate system which creates a multi-decadal lag between carbon dioxide emitted today and its full impact, meaning that further warming is already “locked-in” and climate-related risk will grow over time.

Climate change poses unprecedented challenges… The increase in the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events could trigger non-linear and irreversible financial losses. In turn, the immediate and system-wide transition required to fight climate change could have far reaching effects potentially affecting every single agent in the economy and every single asset price.

François Villeroy de Galhau Governor of the Banque de France

Bank for International Settlements report: Central banking and financial stability in the age of climate change (2020)[footnote 3]

15. All pension schemes are exposed to climate-related risks, whether investment strategies and mandates are active or passive, pooled or segregated, growth or matching, or have long or short time horizons. Many schemes are also supported by employers or sponsors whose financial positions and prospects are dependent on current and future developments in relation to climate change.

Figure 2: Distinct characteristics of climate change that require a different approach[footnote 4]

Far-reaching impact in breadth and magnitude: climate change will affect all actors in the economy, across all sectors and geographies. The risks will likely be correlated with and potentially aggravated by tipping points, in a non-linear fashion. This means the impacts could be much larger, and more widespread and diverse than those of other structural changes.

Foreseeable nature: while the exact outcomes, time horizon and future pathway are uncertain, there is a high degree of certainty that some combination of physical and transition risk will materialise in the future.

Irreversibility: the impact of climate change is determined by the concentration of greenhouse gas emissions in the atmosphere and there is currently no mature technology to reverse this process. Above a certain threshold, scientists have shown with a high degree of confidence that climate change will have irreversible consequences on our planet, though uncertainty remains about the exact severity and horizon.

Dependency on short-term activities: the magnitude and nature of the future impacts will be determined by the actions taken today, which thus need to follow a credible and forward-looking policy path.

16. The potential severity of the physical impacts of climate change and its direct correlation with the concentration of greenhouse gases motivated the international community to commit to reducing emissions in Paris in December 2015. The Paris Agreement[footnote 5], an international treaty negotiated by 197 parties, aims to ensure that the increase in average temperatures above pre-industrial levels is kept to ‘well below’ 2°C by 2100 and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C (Article 2.1(a) UNFCCC, 2015). Restricting global average temperature increases to these levels will require a significant change in the fundamental structure of the economy at national and international levels.

This Agreement […] aims to strengthen the global response to the threat of climate change, in the context of sustainable development and efforts to eradicate poverty, including by […] making finance flows consistent with a pathway towards low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development.

Paris Agreement, Article 2.1(c) UNFCCC, 2015

17. This is likely to affect all parts of the economy, especially energy, manufacturing, construction, transport and agriculture. These transformations and the transition to the low-carbon economy create risks for companies that do not plan and adapt adequately and to the pension funds that hold their equity and debt. It may result in ‘stranded assets’, where the value of certain assets is significantly reduced because they are rendered obsolete or non-performing from a financial perspective.

18. This will be particularly relevant to energy intensive sectors, the fossil fuel-based industries and the wide range of companies and sectors whose current business models are predicated on significant energy use and/or greenhouse gas emissions, most commonly through burning fossil fuels. These companies will be subject to hardening regulatory limits or financial penalties imposed on their activities, replacement by climate-friendly competitors, decarbonisation of the power supply, legal challenges and other non-conventional challenges such as reputational issues resulting from their impact on the climate. Investors will have capital at risk as a result of the low carbon transition.

19. The impact on pension schemes as investors may not be immediately obvious or uniform. For example, whilst the utility sector is one of the most strongly exposed to climate policy risk, it may contribute a relatively small proportion of a typical pension scheme’s investment portfolio. On the other hand, manufacturing may have a lower sectoral risk but may constitute a larger part of a pension scheme’s portfolio and may therefore have a greater overall effect. Trustees need to consider the impacts across their portfolios as a whole.

2.2. Types of climate-related risks

20. When considering the financial implications of climate change, a distinction can be drawn between transition risks and physical risks. The former relates to the risks (and opportunities) from the realignment of our economic system towards low-carbon, climate-resilient and carbon-positive solutions (for example, via regulations or market forces). The latter relates to the physical impacts of climate change (for example, rising temperatures, changing precipitation patterns, increased risk to coastal systems and low-lying areas from rising sea levels and increased frequency and severity of extreme weather events).

21. Perhaps of greatest concern is the significant risk that policy achievement falls short of the Paris Agreement goal, leading to global average temperature increases well in excess of 2°C. Current policies fail to get even close to 2˚C let alone the Paris Agreement ambition of well-below 2°C.

22. Temperature rises based on current policies (with estimates varying from 2.8 to 3.2°C relative to pre-industrial levels based on the current trajectory) would have large and detrimental impacts on global economies, society and investment portfolios.

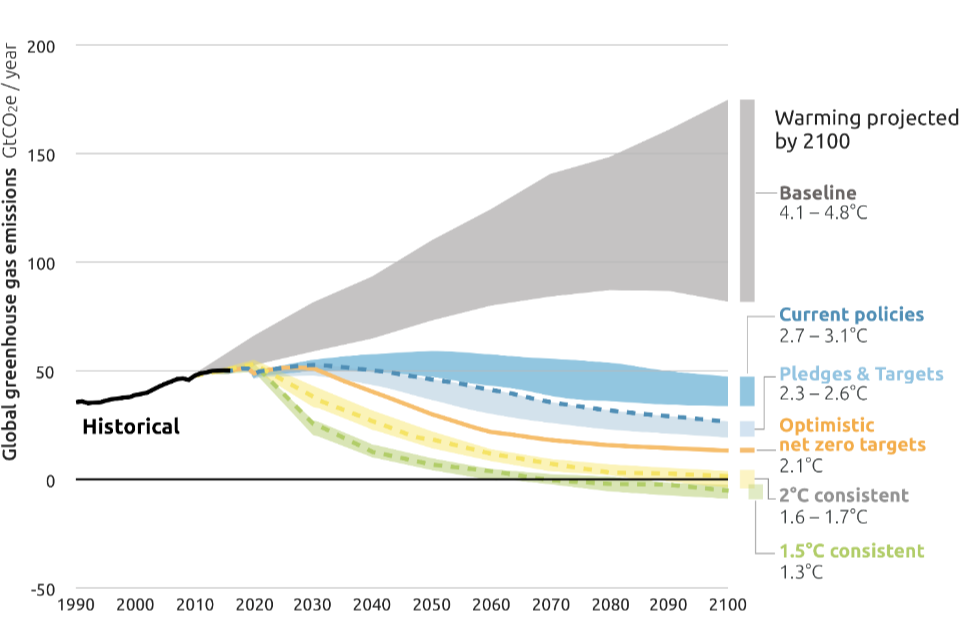

Figure 3: 2100 Warming projections – emissions and expected warming based on pledges and current policies

Baseline: 4.1°C to 4.8°C; Current policies: 2.7°C to 3.1°C; Pledges and targets: 2.3°C to 2.6°C; Optimistic net zero targets: 2.1°C; 2°C consistent: 1.6°C to 1.7°C; 1.5°C consistent: 1.3°C

Source: Climate Action Tracker, Dec 2020 update[footnote 6]

Stranded asset risk

Various research reports have studied the risk of fossil fuel assets becoming ‘stranded’ assets[footnote 7] which ‘at some point prior to the end of their economic life (…) are no longer able to earn an economic return’. This can occur due to a change in policy/legislation, a change in relative costs/prices, or circumstances in the physical environment (for example, impact of floods or droughts).

Fossil fuels are the most obvious example of assets at risk of stranding and there are already examples of coal mines, coal and gas power plants, and hydrocarbon reserves which have become stranded by the low carbon transition. However, other assets may be affected such as gas pipelines and agricultural assets.

Reports have produced varying estimates of the financial impact based on different future scenarios, some of which could have materially detrimental impacts on investment portfolios. It is therefore in the interest of trustees and boards to explore stranded asset risks in the context of their own portfolios, defining their beliefs and assessing current portfolio exposure.

2.3. The impact of the inevitable policy response

23. With current policies anticipated to lead to temperature increases of around 3°C, the longer the delay in climate policy action, the more forceful and urgent any regulatory policy intervention will inevitably be in order to limit global average temperature increases to a level that’s more likely to allow for economic and social stability. This would have a more severe impact on companies and pension schemes as investors.

24. We know now that annual global emissions must start to reduce with a significant annual rate of reduction thereafter[footnote 8]. Without this, companies face increased cost and uncertainty from a disorderly low-carbon transition and increased physical risks, and investors face increased risk compared to a scenario where climate policy is enacted smoothly and steadily.[footnote 9]

2.4. Why trustees cannot assume climate-related risks are already “priced-in”

25. An investor might expect financial market prices – at least in an efficient market – to already reflect the risks presented by a transition to a lower carbon economy and there is some evidence that markets are now partly pricing in climate change risks. However, asset prices may not fully reflect the financial impact of future physical risks or the transition costs associated with policy action required to limit global warming to 2˚C or less.[footnote 10] This is particularly so where “business as usual” models are based on current policies, which are anticipated to lead to temperature increases of around 3°C.

Climate change is striking harder and more rapidly than many expected.

World Economic Forum, Global Risks Report 2020[footnote 11]

26. There are a number of reasons for this. The future of climate policy is highly uncertain given the extended time horizons and political economy considerations, while forecasting requires very long-term projections. There are also challenges in differentiating between long-term economic effects, what the markets are currently pricing, and the potential market shocks if and when the market re-prices climate risks.

27. Finally, the market pricing of assets will say little about a given investor’s own attitude or tolerance to risk, or the implications of different climate scenarios. Trustees should therefore be wary about relying on marked to market pricing of assets as a measure of climate-related financial risks.

3. The legal requirements on trustees to consider climate-related risks and opportunities

Key considerations

- trustees have a legal duty to consider matters which are financially material to their investment decision-making. The climate crisis poses a financial risk to all asset owners, but also presents opportunities for investors. Trustees should consider how, and to what extent, it could impact their investments and the necessary actions that arise from that assessment. This will depend on the investments held and the duration of the scheme. In the case of defined benefit schemes, trustees should also consider potential impacts on their sponsor covenant

- all trustees have additional statutory obligations to document their policies on material financial factors within their statements of investment principles and to consider and document their approach to risk. These statutory obligations specifically require consideration of climate change

- specific requirements to integrate the consideration of climate-related risks and opportunities into trustee governance processes and to make annual public disclosures will, subject to consultation and approval by Parliament, apply to trustees of the largest schemes, authorised master trusts and authorised Collective DC schemes from October 2021 under the government’s proposed climate change governance and reporting regulations

- The Pensions Regulator considers climate change to be systemically significant to its regulatory regime, including protecting member benefits and reducing calls on the PPF

3.1. Fiduciary and trusts law duties

28. Trustees should take advice on their legal duties in the context of specific exercises of investment powers, but may wish to think in terms of three core duties when making investment decisions, as outlined below.

29. In practice day-to-day investment decisions will almost always be delegated to a third party (and in most cases trustees will act on professional advice from investment consultants). However, trustees should be mindful that they retain overall responsibility for securing members’ benefits and are required to provide proper oversight of their delegates (including fiduciary managers[footnote 12]).

(A) Exercise investment powers for their proper purpose

30. Pension scheme trustees must exercise their investment powers for the purposes for which they were given.[footnote 13] The consideration of climate-related risks and opportunities should take place in this context. Trustees should consider how properly taking into account climate-related risks and opportunities will assist in delivering on the purpose of the trust (namely for the provision of pension benefits).

31. In a defined contribution scheme trustees must not relegate the consideration of climate change to members via self-select funds. Rather, trustees must consider its relevance as part of their duty to provide both a default fund and self-select funds appropriate to the needs of the membership.

(B)Take account of material financial factors

32. Trustees should always take into account any relevant matters which are financially material to their investment decision-making. These are frequently referred to as “financial factors”.[footnote 14] This may well be about whether a particular factor is likely to contribute positively or negatively to anticipated returns. But it may equally be about whether a factor will increase or reduce risk.

33. A wide range of factors may impact the long-term sustainability of an investment, including poor governance or environmental degradation. These can all properly be considered by pension trustees to the extent that they are financially material.

34. Chapter 2 explains in further detail the financial risks of climate change and the low carbon transition. Whenever trustees consider that such factors are financially material to their scheme, they should take them into account in their investment decision-making.[footnote 15]

35. When considering the financial implications of climate change, trustees should consider the financial implications of both transition risks and physical risks and determine the extent to which they are financially material to:

- in a defined benefit scheme: the scheme’s assets, liabilities and the covenant of the sponsoring employer(s); and

- in a defined contribution scheme: the investment risk and returns of the default fund and any applicable member self-select funds (see below)

36. Where appropriate, trustees should take advice and implement processes to build climate resilience across pension scheme assets and to take advantage of growing industries or other climate-related investment opportunities available to them.

37. Trustees of schemes providing defined contribution benefits must consider the implications of climate-related risks on any default fund and may also need to consider the extent to which they are taken into account in any member self-select funds (including AVCs). The nature of the funds may dictate which factors are taken into account in the investment processes of those funds. However, trustees should ensure that the funds remain suitable for their members and the materials in relation to them are sufficiently clear, including as to climate-related risks.

(C) Act in accordance with the “prudent person” principle

38. Trustee investment powers must be exercised with the “care, skill and diligence” that “a prudent person would exercise when dealing with investments for someone else for whom they feel morally bound to provide”.[footnote 16]

39. Prudence will always be context specific and will evolve over time. In a defined benefit scheme prudence should be assessed by reference to funding levels and employer covenant and the likely time horizon over which members’ benefits will be paid. In a defined contribution scheme trustees should consider what is appropriate to the membership demographic and the investment objectives of the investment options, including the scheme’s default fund. Trustees should also bear in mind that many members’ pension savings will be invested for a long time (including in drawdown/annuity policies) and will be exposed to longer-term risks and be capable of taking advantage of long-term shifts in sentiment and markets.

40. The financial risks from climate change have a number of distinctive elements which present unique challenges and require a strategic approach to financial risk management[footnote 17]. In line with the prudent person principle, trustees must consider likely future scenarios, how these may impact their investments and what a prudent course of action might be as part of their scheme’s risk management framework. Past data may not be a good indicator of future risks.

41. Trustees should also recognise that market standards are evolving in this area and that what may be considered “prudent” in relation to climate-related risks today might no longer meet that standard in the future, given developing understanding of these risks. Trustees should keep matters under review.

3.2. Pensions Legislation

42. Statutory requirements apply to pension trustees in addition to their fiduciary and trusts law duties. Again, trustees should take advice on their legal obligations but should take note of the following regulatory requirements in particular[footnote 18]:

(A) Effective system of governance including internal controls

43. Section 249A of the Pensions Act 2004 requires that the trustees or managers of pension schemes in scope should have “an effective system of governance including internal controls”, on which The Pensions Regulator must issue a Code of Practice covering matters such as how that effective system of governance:

- provides for sound and prudent management of their activities

- includes consideration of environmental, social and governance factors related to investment assets in investment decisions; and

- is subject to regular internal review

44. The Code of Practice must also cover key functions including an effective risk-management function, and the need for trustees to carry out and document their own-risk assessment. Where environmental, social and governance factors are considered in investment decisions, the Code of Practice will also cover how such risk assessment must include an assessment of new or emerging risks, including risks related to climate change, use of resources and the environment (physical risks), social risks and risks related to the depreciation of assets due to regulatory change (transition risks).

Note: At the time of writing the Code of Practice[footnote 19], has not yet been published.

(B) Disclosure of policies in Statement of Investment Principles

45. For pension schemes to which section 35 of the Pensions Act 1995 applies (broadly, trust-based schemes with at least 100 members), the trustees must prepare a Statement of Investment Principles (SIP). The purpose of a SIP is to set out the trustees’ investment strategy, including their investment objectives and the investment policies they adopt.

46. Trustees must include in their SIPs their policies in relation to risks, including the ways in which risks are measured and managed[footnote 20].

47. Further requirements in relation to the required content of the SIP are included in the Occupational Pension Schemes (Investment) Regulations 2005.[footnote 21] Specific requirements pertinent to climate change include:

- trustees must include their policies in relation to:

- “financially material considerations” over the appropriate time horizon of the investments, including how those considerations are taken into account in the selection, retention and realisation of investments[footnote 22]. Financially material considerations are defined to include “environmental, social and governance considerations (including but not limited to climate change), which the trustees consider financially material”;

- the exercise of the rights, including voting rights attaching to the investments, and on engagement activities in respect of the investments, including when and how the trustees would engage with issuers, asset managers, stakeholders and co-investors on matters including the issuer’s strategy, risks, social and environmental impact and corporate governance

- trustees were required, by 1 October 2020, to include their policies in relation to the trustees’ arrangements with their asset manager(s), setting out how they incentivise each manager to align its investment strategy and decisions with the trustees’ policies mentioned above and to make decisions based on assessments about medium to long-term performance

(C) Annual Report and Accounts

48. Trustees are required to prepare an annual report and accounts within seven months of the end of each scheme year. Further requirements in relation to the required content of the annual report and accounts are included in the Occupational and Personal Pension Schemes (Disclosure of Information) Regulations 2013.[footnote 23]

49. Trustees should take advice on the timing and content required in relation to their particular scheme, although, broadly in each annual report prepared after 1 October 2020:

- trustees of defined benefit schemes must include a statement on how their voting and engagement policies have been implemented

- trustees of schemes providing defined contribution benefits are required to include a statement setting out how, and the extent to which, all policies have been implemented during the year

(D) Pension Schemes Bill 2021

50. Subject to Royal Assent the [Pension Schemes Bill 2019-21] will introduce new powers under sections 41A to 41C of the Pensions Act 1995 for the Secretary of State to make regulations:

- imposing requirements on scheme trustees with a view to securing that there is effective governance of the scheme with respect to the effects of climate change

- requiring information relating to the effects of climate change on the scheme to be published

- with a view to ensuring compliance with the requirements above

51. A consultation was held by the government from 26 August to 7 October 2020 on the government’s proposals.[footnote 24]

52. Further to that consultation, draft regulations and statutory guidance have been published for further consultation on [27 January 2021].[footnote 25]

53. The circumstances and timing by which it is proposed that schemes would fall in and out of scope of the requirements under the regulations is detailed in the draft regulations. Broadly speaking:

- trustees of schemes whose relevant assets are £5 billion or more at the end of their first scheme year to end on or after 1 March 2020, authorised master trusts and authorised schemes (once established) providing collective money purchase benefits would be subject to the climate change governance requirements from 1 October 2021[footnote 26] – including for the remainder of the scheme year which is underway on this date – and all must produce a TCFD report in line with the reporting requirements within 7 months of their scheme year end date

- trustees of schemes whose relevant assets are £1bn or more on the next scheme year end date on or after 1 March 2021 would be subject to the governance requirements from 1 October 2022 and all must produce a TCFD report in line with the governance requirements within 7 months of their scheme year end date

54. The draft regulations would require the trustees of schemes in scope to, among other things:

- implement climate change governance measures and produce a TCFD report containing associated disclosures; and

- publish their TCFD report on a publicly available website, accessible free of charge

55. The draft regulations also contain amendments to the Occupational and Personal Pension Schemes (Disclosure of Information) Regulations 2013, which would require the trustees of schemes in scope to, among other things:

- tell members that the TCFD report has been published and where they can locate it, via the annual benefit statement and, for DB schemes, the annual funding statement

Voluntary obligations

Trustees who have agreed to become signatories to voluntary initiatives may have already accepted additional climate reporting obligations.

PRI signatories: the PRI is making some climate indicators mandatory to report to PRI itself but voluntary to disclose publicly. The remaining PRI climate-related risks indicators will stay voluntary with a view to becoming mandatory as good practice develops.

Stewardship Code signatories[footnote 27]: signatories must (principle 4) report on how they have identified and responded to market-wide and systemic risks including climate change, and how they have (principle 7) ensured tenders have included a requirement to integrate climate change to align with the time horizons of clients and beneficiaries.

4. The TCFD recommendations

Key considerations

- the TCFD has established a set of eleven clear, comparable and consistent recommended disclosures about the risks and opportunities presented by climate change. The increased transparency encouraged through the TCFD recommendations is intended to lead to decision-useful information and therefore better informed decision-making on climate-related financial risks

- by applying the TCFD recommendations and making the recommended disclosures, pension trustees will be better placed to properly assess and understand what climate change actually means for their particular scheme – and will be better equipped to make decisions that ensure the best outcomes for pension scheme members

4.1. A lens for understanding climate-related financial risks

56. The Financial Stability Board’s Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) was established as an industry-led initiative in December 2015 to develop recommendations for clear, comparable and consistent disclosures of climate-related risks and opportunities in mainstream financial reports. The TCFD aimed to improve the quality of climate-related financial disclosures thereby “support[ing] more appropriate pricing of risks and allocation of capital in the global economy”.[footnote 28]

57. The TCFD recommendations (issued in June 2017) establish a set of recommended disclosures through which organisations can identify and disclose decision-useful information about material climate-related financial risks and opportunities.[footnote 29] The recommendations are also applicable to asset owners and asset managers. As of February 2020, 1027 organisations globally had declared their support for the TCFD, representing a market capitalisation of over $12 trillion[footnote 30] and extensive work is ongoing across a number of industry and regulatory groups to support widespread implementation of the TCFD’s recommendations.[footnote 31]

58. The TCFD recommendations are structured around 4 thematic areas that represent core elements of how organisations operate: governance, strategy, risk management, and metrics and targets. These might be considered to apply to pension trustees (as asset owners) as follows:

Figure 4: The TCFD recommendations

""

Governance – Disclose the trustees’ governance around climate-related risks and opportunities

Strategy – Disclose the actual and potential impacts of climate-related risks and opportunities on the pension scheme where such information is material

Risk Management – Disclose how the trustees identify, assess, and manage climate-related risks

Metrics and Targets – Disclose the metrics and targets used to assess and manage relevant climate-related risks and opportunities where such information is material

59. The 4 core elements of the TCFD recommendations are supported by eleven recommended disclosures set out in the table below.

TCFD Recommended Disclosures

| Governance | Strategy | Risk Management | Metrics and Targets | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| a) Describe the board’s oversight of climate-related risks and opportunities | a) Describe the climate-related risks and opportunities the organisation has identified over the short, medium, and long-term. | a) Describe the organisation’s processes for identifying and assessing climate-related risks. | a) Disclose the metrics used by the organisation to assess climate-related risks and opportunities in line with its strategy and risk management process. | |

| b) Describe management’s role in assessing and managing climate-related risks and opportunities. | b) Describe the impact of climate-related risks and opportunities on the organisation’s businesses, strategy, and financial planning. | b) Describe the organisation’s processes for managing climate-related risks. | b) Disclose Scope 1, Scope 2, and, if appropriate, Scope 3 greenhouse gas emissions, and the related risks.[footnote 32] | |

| c) Describe the resilience of the organisation’s strategy, taking into consideration different climate-related scenarios, including a 2°C or lower scenario. | c) Describe how processes for identifying, assessing, and managing climate-related risks are integrated into the organisation’s overall risk management. | c) Describe the targets used by the organisation to manage climate-related risks and opportunities and performance against targets. |

4.2. Why the TCFD recommendations may be helpful for pension scheme trustees

60. As set out in Chapter 3, pension scheme trustees are already subject to a number of statutory requirements to specify and disclose their policies on climate change, alongside other policies relating to environmental, social and governance (ESG) considerations. Several of the TCFD disclosures align to these existing statutory requirements, including disclosure of trustees’ strategy via their policies on climate change, and their governance, via the requirement for an effective system of governance that includes “consideration of environmental, social and governance factors related to investment assets in investment decisions”.

61. All the TCFD disclosures are likely to assist trustees demonstrate compliance with their fiduciary duties to take account of relevant factors which are financially material to their investment decision-making and to act prudently.

62. Although the TCFD recommendations focus on “disclosures” by organisations, the framework is fundamentally a useful tool for pension trustees in assessing the relevance of climate change and managing any consequences. This may assist trustees in meeting the legal requirements on considering climate-related risks. It will also be a useful lens for trustees of DC and hybrid schemes as they compile the relevant statement on how they have implemented policies in the SIP, as required from 1 October 2020. In particular, the TCFD’s Strategy (c) recommendation to assess the resilience of their strategies (and by extension portfolio) using scenario-based analysis (see Part III) encourages forward-looking, long-term assessment of the financial implications of climate change.

4.3. Disclosure

63. The increased transparency encouraged under the TCFD recommendations and 11 recommended disclosures is intended to lead to better informed decision-making. More broadly, better quality information contributes towards more efficient and sustainable markets.

64. The government has stated (in its 2019 Green Finance Strategy) that all listed companies and large asset owners, including occupational pension schemes, are expected to disclose in line with the TCFD recommendations by 2022.[footnote 33] However, not all pension scheme trustees will be subject to statutory requirements under the government’s proposed climate change governance and reporting regulations.

65. Regardless of whether a scheme is required by regulations to make public TCFD disclosures, chooses to do so on a voluntary basis or has chosen to prioritise the adoption of robust governance procedures as a first step (with public disclosure as a second step), this guide is intended to help all trustees to lay the groundwork and develop good practice.

66. To promote disclosure of “decision-useful” information, the TCFD has outlined seven Principles for Effective Disclosures, which should: 1) represent relevant information; 2) be specific and complete; 3) be clear, balanced, and understandable; 4) be consistent over time; 5) be comparable among companies within a sector, industry, or portfolio; 6) be reliable, verifiable, and objective; 7) be provided on a timely basis. Further information on these principles and guidance on disclosure can be found in Part II, Chapter 5.

67. The UK Government has also now announced its intention to make TCFD-aligned disclosures mandatory across the economy by 2025, with a significant portion of mandatory requirements in place by 2023. The UK Taskforce’s Interim Report, and accompanying Roadmap[footnote 34], sets out a pathway to achieving that ambition.

Appendix – Further reading/links

Financial Stability Board’s Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD):

Final Report: Recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (June 2017)

Annex: Implementing the Recommendations of the TCFD (June 2017)

Technical Supplement: The Use of Scenario Analysis in Disclosure of Climate-related Risks and Opportunities (June 2017)

TCFD: 2019 Status Report (June 2019)

Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI):

TCFD-based reporting to become mandatory for PRI signatories in 2020 (February 2019)

Implementing the TCFD recommendations: a guide for asset owners (May 2018)

Preparing investors for the Inevitable Policy Response to climate change (September 2019)

PRI Reporting Framework 2019: Strategy and Governance (Climate-related indicators only) (July 2019)

See also: Climate-related disclosure

Climate Disclosure Standards Board (CDSB):

TCFD Implementation Guide (May 2019)

TCFD Good Practice Handbook (September 2019)

Institutional Investors Group on Climate Change (IIGCC):

Navigating climate scenario analysis – a guide for institutional investors (February 2019)

See also various sector level reports (utilities, oil and gas, property and construction, industrials manufacturing and materials) that examine the climate-related risks and opportunities from an investor perspective in the transition to a 2ºC or less outcome

Institute and Faculty of Actuaries (IFoA):

Climate Change for Actuaries: An Introduction (March 2019)

R&E Issues: A Practical Guide for Defined Benefit Pensions Actuaries (April 2017)

Climate Risk: A Practical Guide for Actuaries working in Defined Contribution Pensions (March 2018)

All available at Sustainability practice area: practical guides

Miscellaneous:

HM Government: Green Finance Strategy – Transforming Finance for a Greener Future (July 2019)

The 2° Investing Initiative: Assessing the Alignment of Portfolios with Climate Goals (October 2015)

Accounting for Sustainability Project (A4S): Supporting the TCFD Recommendations

Aon, Climate change challenges: Some case studies (2018)

CICERO, Climate Scenarios demystified: A climate scenario guide for investors

Local Authority Pension Fund Form: Climate Change Investment Policy Framework (2017)

Mercer, Investing in a Time of Climate Change, the Sequel (2019)

Pensions and Lifetime Savings Association (PLSA) – “More Light Less Heat” report (December 2017)

Pensions and Lifetime Savings Association (PLSA) – Stewardship Guidance and Voting Guidelines 2020 (February 2020) – includes a section specifically on climate stewardship and good corporate behaviour

The Pensions Policy Institute - ESG: past, present and future (October 2018)

Schroders, Climate Progress Dashboard – navigating risks and opportunities

The Transition Pathway Initiative (TPI): How can investors use the TPI? (January 2017)

The Transition Pathway Initiative (TPI): TPI State of Transition Report (2019)

UK Sustainable Investment and Finance Association (UKSIF): A Checklist for Pension Trustees

-

IPCC, Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2014. See also NASA Global Climate Change. ↩

-

Bank for International Settlements report: Central banking and financial stability in the age of climate change 2020. ↩

-

HM Government: Green Finance Strategy – Transforming Finance for a Greener Future (July 2019). ↩

-

Nature (2017) “Three years to safeguard our climate” 28th June 2017. ↩

-

See United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative - Investor Pilot (May 2019), capturing the analysis, evaluation and testing of 1.5°C, 2°C, and 3°C scenario-based analysis on the investment portfolios of institutional investors. ↩

-

BNY Mellon report, Future 2024: Future proofing your asset allocation in the age of mega trends (September 2019). ↩

-

See The Pensions Regulator: Choose an investment governance model. ↩

-

Trustees should be mindful of the different duties applying to defined benefit pension schemes (where the trustee duty is to invest the scheme’s assets appropriately to pay the scheme’s promised benefits) and to defined contribution schemes (where the purpose of the investment power is to provide a “pot” of money to be used by each member to provide for his or her retirement). ↩

-

For further detail see the Law Commission’s report on the Fiduciary Duties of Investment Intermediaries (July 2014). ↩

-

Keith Bryant QC and James Rickards, The legal duties of pension fund trustees in relation to climate change (November 2016). ↩

-

Re Whiteley (1896) 33 Ch D 347 at 355 ↩

-

Bank of England Prudential Regulation Authority, Supervisory Statement 3/19: ‘Enhancing banks’ and insurers’ approaches to managing the financial risks from climate change’ (April 2019). ↩

-

This guidance is aimed at occupational pension schemes in both Great Britain and Northern Ireland. For schemes in Northern Ireland, corresponding Northern Ireland legislation applies. ↩

-

Occupational Pension Schemes (Investment) Regulations 2005, regulation 2(3)(b)(iii) ↩

-

as amended by the Pension Protection Fund (Pensionable Service) and Occupational Pension Schemes (Investment and Disclosure) (Amendment and Modification) Regulations 2018 and by the Occupational Pension Schemes (Investment and Disclosure) (Amendment) Regulations 2019 ↩

-

Occupational Pension Schemes (Investment) Regulations 2005, Regulation 2(3)(b)(vi) ↩

-

as amended by the Pension Protection Fund (Pensionable Service) and Occupational Pension Schemes (Investment and Disclosure) (Amendment and Modification) Regulations 2018 and by the Occupational Pension Schemes (Investment and Disclosure) (Amendment) Regulations 2019 ↩

-

See Government consultation: “Taking action on climate risk: improving governance and reporting by occupational pension schemes” (August 2020). ↩

-

The draft Occupational Pension Schemes (Climate Change Governance and Reporting) Regulations 2021 and the draft Occupational Pension Schemes (Climate Change Governance and Reporting) (Miscellaneous Provisions and Amendments) Regulations 2021. ↩

-

Or the date they obtain their audited accounts, if later. ↩

-

Final Report. Recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures. June 2017, p.v.. ↩

-

See Appendix [6] (further reading/links) for details of TCFD Report and materials, including the TCFD Knowledge Hub. ↩

-

See, for example, FCA consultation CP20/3: Proposals to enhance climate-related disclosures by listed issuers and clarification of existing disclosure obligations. ↩

-

Scope 1 greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions are direct emissions from sources that are owned or controlled by an entity. Scope 2 GHG emissions are indirect emissions from sources that are owned or controlled by an entity (for example, electricity, heat, or steam purchased from a utility provider). Scope 3 GHG emissions are from sources not owned or directly controlled by an entity but related to the entity’s activities (for example, employee commutes). ↩

-

See Government Green Finance Strategy – Transforming Finance for a Greener Future (July 2019), although note that “large asset owner” has yet to be defined. ↩

-

UK joint regulator and government TCFD Taskforce: Interim Report and Roadmap - Published 9 Nov 2020. ↩