Police powers: pre-charge bail government consultation (accessible version)

Updated 6 September 2021

This consultation begins on Wednesday 5 February 2020.

This consultation ends on Friday 29 May 2020.

About this consultation

To: Groups and/or individuals impacted or representing the interests of those impacted by pre-charge bail, including but not limited to: the public, victims, organisations that support victims and survivors, the police and associated bodies, those who may have been under investigation, local government, legal representatives, the courts and the stakeholders with an interest in the wider criminal justice system. England and Wales only.

Duration: From 05/02/20 to 29/05/20

Enquiries to: Email: pacereview@homeoffice.gov.uk; or

Pre-charge Bail Consultation

Police Powers Unit

6 Floor Fry

2 Marsham Street

SW1P 4DF

How to respond: Respond to the questions in this consultation online.

Alternatively, you can send in electronic copies to: pacereview@homeoffice.gov.uk; or

Alternatively, you may send paper copies to:

Pre-charge Bail Consultation

Police Powers Unit

6 Floor Fry

2 Marsham Street

SW1P 4DF

Additional ways to respond: If you wish to submit other evidence, or a long-form response, please do so by sending it to the email address or postal address above. Response paper: We aim to publish a government response to this consultation within three months of it closing. The response will be made available online.

Home Secretary Foreword

This government is committed to ensuring the police have the powers they need to protect the public and that our criminal justice system has at its heart the welfare and best interests of victims.

The power to release an individual under investigation on pre-charge bail, potentially with conditions, while investigations continue is an important tool. Pre-charge bail allows the police to maintain contact with individuals under investigation, it can support the timely progression of investigations and conditions may be applied to manage the risk of harm to victims and witnesses.

Since rule changes in 2017 there have been concerns that pre-charge bail is not always being used where appropriate to protect victims, investigations are taking longer to conclude and that this has had adverse impacts on the courts.

This is a government that both listens and acts. On 5 November 2019 the government announced a review of pre-charge bail to address the concerns raised around the impact of current rules on the police, victims, those under investigation and the broader criminal justice system.

There are no quick fixes here. The concerns raised in relation to the 2017 reforms are also due to several other complex factors. Improving the effectiveness of the bail system is only the first step on that journey and is not the limit of our ambition.

Our aim is to have a system which protects victims, enables the police to investigate crimes effectively and respects the rights of individuals under investigation.

This consultation sets out a series of proposals to address these concerns and support the police in the work that they do to keep us safe and I encourage you to respond.

Rt Hon Priti Patel MP

Home Secretary

Introduction

An individual who has been arrested by the police but who has not yet been charged can be released on pre-charge bail or released without bail while the investigation continues. Pre-charge bail means the individual under investigation is released from police custody, with or without conditions, while officers continue their investigation.

Individuals on pre-charge bail are required to return to the police station at a specified date and time, known as ‘answering bail’, to either be informed of a final decision on their case or to be given an update on the progress of the investigation.

Conditions may be imposed upon the individual if they are deemed necessary to: prevent someone from failing to surrender to custody, prevent further offending, prevent someone from interfering with witnesses, or otherwise obstructing the course of justice. Conditions may also be imposed for the individuals’ own protection or, if aged under 18, for their own welfare and interests.

The government legislated through the Policing and Crime Act 2017 to address concerns that individuals were being kept on pre-charge bail for long periods, sometimes with strict conditions. The reforms introduced:

- a presumption against pre-charge bail unless necessary and proportionate; and

- clear statutory timescales and processes for the initial imposition and extension of bail, including the introduction of judicial oversight for the extension of pre-charge bail beyond three months.

Since the reforms came into force, we have been working closely with partners across the criminal justice system to track implementation and monitor impacts. The use of pre-charge bail has fallen significantly, mirrored by an increasing number of individuals released without bail, commonly known as ‘released under investigation’ or RUI. This change has raised concerns that bail is not always being used when appropriate, including to prevent individuals from committing an offence whilst on bail or interfering with witnesses. Other concerns focus on the potential for longer investigations in cases where bail is not used and the adverse impacts on the courts.

On 5 November 2019 the government announced a review of the pre-charge bail legislative framework. The objective of the review is to make sure we have a system that:

- prioritises the safety of victims and witnesses;

- supports the effective management of investigations;

- respects the rights of individuals under investigation, victims and witnesses to timely decisions and updates; and

- supports the timely progression of cases to courts.

This public consultation exercise is a central part of the review. This paper sets out issues raised by a wide range of stakeholders across policing and law enforcement, relevant government agencies and external organisations, alongside a corresponding set of initial proposals.

During the consultation period we intend to engage with a wide range of external stakeholders including the police, victims, groups who advocate for and provide services to support victims of crime, the judiciary, academics, legal representatives and individuals who have been under investigation.

We are especially keen to hear from you if you have been a victim of crime, a witness or under investigation. An opportunity to share your experience and views can be found on page 22, questions 12 & 13.

As part of the wider review we will also consider:

- A rapid review of existing evidence on pre-charge bail, the initial findings of which can be found in Annex A;

- HM Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire & Rescue Service’s (HMICFRS) thematic inspection into pre-charge bail and released under investigation; and

- HMICFRS’ inspection into the super-complaint by the Centre for Women’s Justice into ‘Police failure to use protective measures in cases involving violence against women and girls’.

When responding to the consultation questions, please remove any personally identifiable information such as names, locations or dates.

Issues, Proposals and Questions

Criteria for pre-charge bail

Issues

To address concerns about individuals being placed on pre-charge bail for long periods, the Policing and Crime Act 2017 introduced a presumption against pre-charge bail unless its application is considered both necessary and proportionate in all the circumstances.

The government has been clear that it fully supports the use of pre-charge bail. This point is also reinforced by guidance released by the National Police Chiefs’ Council (NPCC), which stresses the need to consider bail in high harm[footnote 1] cases.

However, following discussions with the police and other stakeholders we are concerned that pre-charge bail is not being used in cases where it may be necessary to prevent an individual from failing to surrender to custody, to prevent the individual from committing an offence whilst on bail or to prevent the individual from interfering with witnesses or otherwise obstructing the course of justice.

The Government therefore considers it necessary to review the presumption against pre-charge bail and the criteria for its application.

Through discussions with stakeholders four main approaches for achieving this have been identified:

-

a return to the use of bail for all cases following arrest;

-

removing the general presumption against bail and introducing offence-based criteria for when bail should be used;

-

removing the general presumption against bail and introducing specific risk-based criteria indicating when bail should be used;

-

removing the general presumption against bail but maintaining the requirement for bail to be necessary and proportionate.

We believe the bail rules should assist the police to make risk-based decisions, and to use their experience to consider the application of pre-charge bail on a case by case basis, rather than being required to apply bail for specific offences or in all cases. An offence specific approach would also ignore the vulnerability and needs of victims and witnesses for lower level offences. As such, the government believes a risk-based approach warrants further consideration.

Proposal

Proposal 1: The Government proposes legislating: (i) to end the presumption against pre-charge bail, instead requiring pre-charge bail to be used where it is necessary and proportionate and (ii) to add a requirement that a constable must have regard to the following factors when considering whether application of pre-charge bail is necessary and proportionate:

-

The severity of the actual, potential or intended impact of the offence;

-

The need to safeguard victims of crime and witnesses, taking into account their vulnerability;

-

The need to prevent further offending;

-

The need to manage risks of a suspect absconding; and

-

The need to manage risks to the public.

Questions

Q1. To what extent do you agree/disagree that the general presumption against pre-charge bail should be removed?

| Strongly agree | Agree | Neither agree nor disagree | Disagree | Strongly disagree |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Q2. To what extent do you agree/disagree that the application of pre-charge bail should have due regard to specific risk-factors?

| Strongly agree | Agree | Neither agree nor disagree | Disagree | Strongly disagree |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Q3. To what extent do you agree/disagree that the application of pre-charge bail should consider the following risk factors:

a. The severity of the actual, potential or intended impact of the offence;

| Strongly agree | Agree | Neither agree nor disagree | Disagree | Strongly disagree |

|---|---|---|---|---|

b. The need to safeguard victims and witnesses, taking into account their vulnerability;

| Strongly agree | Agree | Neither agree nor disagree | Disagree | Strongly disagree |

|---|---|---|---|---|

c. The need to prevent further offending;

| Strongly agree | Agree | Neither agree nor disagree | Disagree | Strongly disagree |

|---|---|---|---|---|

d. The need to manage risks of a suspect absconding; or

| Strongly agree | Agree | Neither agree nor disagree | Disagree | Strongly disagree |

|---|---|---|---|---|

e. The need to manage risks to the public.

| Strongly agree | Agree | Neither agree nor disagree | Disagree | Strongly disagree |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Q4. Do you have any other comments? For example, are there any other risk-factors

we should consider? Or any comments on the discounted approaches identified on

page 7? (250 words)

Timescales for pre-charge bail

Issues

To address the issue of individuals being under investigation for long periods, sometimes with excessive bail conditions, the Policing and Crime Act 2017 introduced:

- An initial 28-day limit to the use of pre-charge bail authorised by an inspector; with subsequent extensions up to 3 months and beyond to be authorised by senior officers (superintendents or above) and magistrates, respectively; and

- A requirement for senior officers and magistrates to authorise extensions to bail only if there are reasonable grounds for suspecting the individual under investigation to be guilty. The senior officer must also have reasonable grounds for believing that: further time is needed to make a charging decision or further investigation is needed; the decision to charge is being made, or the investigation is being conducted, diligently and expeditiously; and the use of pre-charge bail is still necessary and proportionate in all the circumstances.

Policing stakeholders have told us that these changes have disincentivised the use of bail, especially in complex cases which require further investigation and can be difficult to progress and/or conclude in 28 days. Following discussions with stakeholders we consider it necessary to review the existing statutory framework to more accurately reflect investigatory timescales.

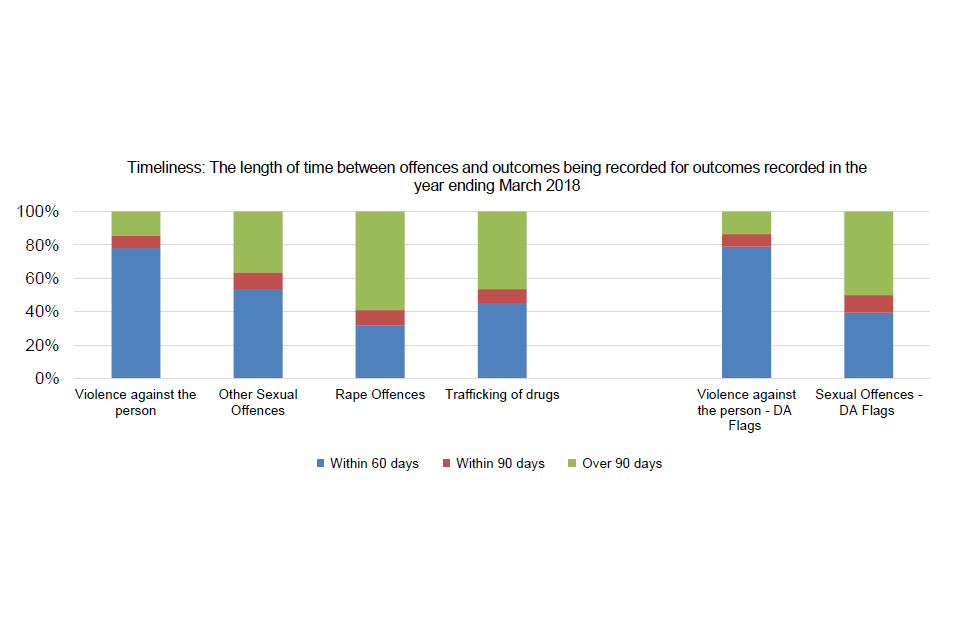

Home Office data[footnote 2] [footnote 3] from published statistical bulletins on crime outcomes for those offences where pre-charge bail might be more commonly applied, suggest cases do take longer than the 28-day limit, which corroborates the concerns raised by stakeholders. In both 2017/18 and 2018/19, 29% of all offence types took longer than 30 days to reach an outcome. For violence against the person offences, the proportion was higher at 36% in 2017/18 and 37% in 2018/19[footnote 4].

Bespoke analysis of the 2017/18 dataset (see graph) shows that 78% of violence against the person offences were dealt with within 60 days and a further 7% had an outcome recorded within 90 days. Violence offences flagged as domestic abuse showed similar proportions.

Sexual offences had longer investigation times. For example, only 32% of rape offences concluded within 60 days, with a further 9% dealt with within 90 days. Around 59% of rape offences required more than 90 days for the investigation to be closed.

A stacked bar chart showing the length of time between offences and outcomes being recorded in the year ending March 2018.

Proposal

Proposal 2: The Government proposes legislating to amend the statutory framework governing pre-charge bail timescales and authorisations and seeks views on three potential models.

We have developed three models that are intended to remove disincentives against use of pre-charge bail whilst supporting the timely progression of investigations.

All three models propose:

- restoring the initial bail authorisation to custody officers given both their independence from investigations and their experience in making risk-based decisions;

- introducing additional points at which the investigation including the use of pre-charge bail will be reviewed;

- maintaining an initial bail period - but increasing its length; and

- maintaining judicial oversight but changing the point at which judicial oversight of authorisations is introduced.

Statutory timescales and judicial oversight could be removed altogether but we believe both safeguards are important for ensuring that pre-charge bail is used appropriately, proportionately and also to support the management and progression of investigations.

The table below compares each model to each other and against the current regime.

| Current | Model A | Model B | Model C | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Bail period | To 28 days, Inspector | To two months, Custody Officer | To three months, Custody Officer | To three months, Custody Officer |

| First extension | To three months, Superintendent | To four months, Inspector | To six months, Inspector | To six months, Inspector |

| Second extension | Beyond three months, Magistrate (at three-month extension intervals) | To six months, Superintendent | To nine months, Superintendent | To nine months, Superintendent |

| Third extension | As above. | Beyond six months, Magistrate (at three-month extension intervals) | Beyond nine months, Magistrate (at three-month extension intervals) | To 12 months, Superintendent |

| Fourth extension | As above. | As above. | As above. | Beyond 12 months, Magistrate (at three-month extension intervals) |

The table below visualises the differences between these models, to aid comparison.

| Months | Current | Model A | Model B | Model C |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Initial bail period Inspector | Initial bail period Custody Officer | Initial bail period Custody Officer | Initial bail period Custody Officer |

| 2 | First extension Superintendent | Initial bail period Custody Officer | Initial bail period Custody Officer | Initial bail period Custody Officer |

| 3 | First extension Superintendent | First extension Inspector | Initial bail period Custody Officer | Initial bail period Custody Officer |

| 4 | Second extension Magistrate | First extension Inspector | First extension Inspector | First extension Inspector |

| 5 | Second extension Magistrate | Second extension Superintendent | First extension Inspector | First extension Inspector |

| 6 | Second extension Magistrate | Second extension Superintendent | First extension Inspector | First extension Inspector |

| 7 | Third extension Magistrate | Third extension Magistrate | Second extension Superintendent | Second extension Superintendent |

| 8 | Third extension Magistrate | Third extension Magistrate | Second extension Superintendent | Second extension Superintendent |

| 9 | Third extension Magistrate | Third extension Magistrate | Second extension Superintendent | Second extension Superintendent |

| 10 | Fourth extension Magistrate | Fourth extension Magistrate | Third extension Magistrate | Third extension Superintendent |

| 11 | Fourth extension Magistrate | Fourth extension Magistrate | Third extension Magistrate | Third extension Superintendent |

| 12 | Fourth extension Magistrate | Fourth extension Magistrate | Third extension Magistrate | Third extension Superintendent |

| 13 | Fourth extension Magistrate | Fourth extension Magistrate | Fourth extension Magistrate | Fourth extension Magistrate |

| 14 | Fourth extension Magistrate | Fourth extension Magistrate | Fourth extension Magistrate | Fourth extension Magistrate |

| 15 | Fourth extension Magistrate | Fourth extension Magistrate | Fourth extension Magistrate | Fourth extension Magistrate |

To understand the potential impact of the proposed models, we have compared each against the data set out above on the length of investigations for different offence types.

Model A would require frequent authorisations by magistrates for complex cases such as sexual offences, as more than 6 months will often be required for investigation to conclude. Model A would however capture most of the violence and drug offences and low-level offences within the initial or first bail extension period.

Model B would require fewer authorisations by magistrates in comparison to model A as the 9-month Superintendent limit could expect to capture at least 70% of sexual offences with magistrate approval only required in 30% of cases.

Model C would require the fewest magistrate authorisations of the three models. However, magistrate authorisations would still be required in 36% of all rape offences resulting in a charge, compared to the 47% in model B. This suggests the addition of a Superintendent bail extension up to 12-months would not significantly reduce the number of complex cases that require magistrate oversight.

Models B and C would both capture most crimes without requiring judicial oversight. However, some serious and complex offences such as rape would still require magistrate authorisations of extensions to pre-charge bail in a large proportion of investigations in both models.

Questions

Q5: Please rank the options below in order of preference (1st, 2nd , 3 rd and 4 th).

| Current model | Model A | Model B | Model C |

|---|---|---|---|

Q6. Do you have any other comments? For example, do you have a different

proposal or are there circumstances in which the proposed timescales would not be

appropriate? (250 words)

Non-bail investigations

Issues

Prior to 2017, all individuals released after arrest while investigations continued were released on pre-charge bail. Reforms enabled individuals under investigation to be released without bail instead, known as “released under investigation” or RUI.

Not all individuals on RUI have been arrested, it has become increasingly common for individuals to be interviewed voluntarily. This is known as Voluntary Attendance (VA). We therefore use the terminology “non-bail” to refer to investigations when pre-charge bail is not used, including cases where the individual may not have been arrested but is still under investigation.

As stated previously, we believe the 2017 reforms disincentivised the use of pre-charge bail which has led to the fall in the use of bail and the subsequent rise in the use of RUI and other non-bail investigations. RUI and other non-bail investigations are not subject to the same statutory framework as pre-charge bail. This means there are no timescales or oversight set out in legislation.

Stakeholders have raised concerns that the increased use of RUI has had two major impacts:

a. Longer investigations

The police do not have fixed dates to update individuals, victims and witnesses on the progression of their investigations and there are no legal requirements governing timescales. Stakeholders are concerned that this may be disincentivising the timely progression of investigations. However, there are other complex drivers that are also contributing to longer investigations such as the capacity of non-police agencies and increasing amounts of digital evidence. The impact of RUI on investigatory timescales is being explored by HMICFRS as part of their thematic inspection on the issue and their findings will inform our final proposals.

Longer investigations may increase the risk of individuals offending/re-offending while under investigation and may increase the likelihood of victims and witnesses disengaging or withdrawing as more time passes from the date of the original offence. In addition, individuals under investigation may be left without a decision on their case for a long time which can cause uncertainty and stress, especially in cases when the person under investigation is innocent and there is ultimately no further action.

b. Delays to courts

As individuals on RUI are not required to return to a police station for a charging decision, they are instead charged via post known as a “postal charge and requisition” (PCR). As stated above, we are aware of concerns that pre-charge bail is not always applied to individuals where it would be necessary and proportionate to effectively manage risk of them absconding. As such there may be individuals on RUI who are at risk of absconding and who are, therefore, less likely to respond to their PCR.

Individuals who fail to respond to their PCR are therefore failing to turn up to court for their hearing, known as ‘failure to attend’ (FTA). FTA is an offence for which a magistrate can issue a warrant so the police may arrest the individual and bring them to court. An increase in the rate of FTA creates delays in the progression of cases to court, increased costs to court, increased costs to the police and decreased likelihood of prosecution.

The National Police Chiefs’ Council (NPCC) have sought to address the lack of statutory oversight of RUI by issuing guidance that recommends supervisory reviews of RUI cases every 30 days, regular updates to victims and individuals, and the setting of target investigation end dates. It is too soon to determine whether the guidance has had an impact.

The statutory framework governing the use of pre-charge bail puts in place clear timescales and requirements for supervision. However, there is no equivalent framework for RUI and VA cases.

Proposal

Proposal 3: The government proposes a new framework for the supervision of RUI and VA cases.

We propose that the framework for RUI and VA cases would mirror the timescales already in place for pre-charge bail and any changes that may be made to those timescales as a result of this review. The proposed framework would not put a limit on the length of police investigations, and reviews would be carried out by the police and not be subject to judicial oversight. Individuals on RUI and VA would not be subject to conditions.

This framework would be set out in codes of practice. This approach ensures compliance whilst allowing the regime to be amended should the length or nature of investigations change in the future.

Questions

Q7. To what extent do you agree/ disagree that there should be timescales in codes of practice around the supervision of ‘released under investigation’ and voluntary attendance cases?

| Strongly agree | Agree | Neither agree nor disagree | Disagree | Strongly disagree |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Q8. Do you have any other comments? For example, if you disagree, do you have

alternative proposals for the supervision of ‘released under investigation’ and

voluntary attendance cases? (250 words)

Effectiveness of bail conditions

Issue

Individuals released from police custody on pre-charge bail may be subject to conditions, for example, prohibiting them from contacting the victim. We are aware of concerns around the efficacy of these conditions.

There are two ways pre-charge bail can be infringed:

- Failing to answer pre-charge bail; and

- Breaching pre-charge bail conditions.

Failure to answer pre-charge police bail (i.e. to return to the police station) is a criminal offence, whereas breaching pre-charge bail conditions is not.

When an individual on pre-charge bail fails to answer, they can be arrested on suspicion of committing a criminal offence under section 6 of the Bail Act 1976, which carries a maximum three-month sentence of imprisonment or a fine on conviction.

If an individual breaches their conditions of pre-charge bail, they can be arrested and taken to the police station. A breach of pre-charge bail conditions is not a criminal offence, although the breach action may be a separate offence. For example, contacting a witness may also be an offence under the Protection from Harassment Act 1997 where someone pursues a course of action that amounts to harassment of another. If there is sufficient evidence at the time of the breach, officers may charge the individual for the original offence for which they are under investigation, or any subsequent offence, and keep them in custody on remand, or re-release them on bail. Someone’s behaviour while on bail may be relevant evidence of the original offence, or relevant for the purposes of sentencing on conviction. However, more commonly the individual is brought into custody only to be re-released on pre-charge bail with the same conditions as previously.

Stakeholders have raised concerns with the Home Office that the lack of criminal penalty associated with breaching bail conditions may have negative consequences. For example, as breach of conditions carries no penalty individuals may be more likely to breach their conditions and the police may be less likely to act upon them. Breaches of pre-charge bail conditions may negatively impact on the public’s trust in the criminal justice system especially when the breaches do not result in police action. In addition, breaches of conditions can also often mean further offences have been committed.

To understand these issues in more detail we are seeking views on the effectiveness of bail conditions.

Questions

Q9. To what extent do you agree/disagree that pre-charge bail conditions could be made more effective:

a. to prevent someone interfering with victims and witnesses?

| Strongly agree | Agree | Neither agree nor disagree | Disagree | Strongly disagree |

|---|---|---|---|---|

b. to prevent someone committing an offence while on bail?

| Strongly agree | Agree | Neither agree nor disagree | Disagree | Strongly disagree |

|---|---|---|---|---|

c. to prevent someone failing to surrender to custody?

| Strongly agree | Agree | Neither agree nor disagree | Disagree | Strongly disagree |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Q10. What could be done to make bail conditions more effective? (250 words)

Other issues

Q11. Are there any other issues or proposals you would like to raise with us in

relation to the use of pre-charge bail or released under investigation? (250 words)

Your experience

We would like to hear from you if have been a victim of crime, witness or under investigation. Please remove any personally identifiable information from your answers such as names, locations and dates.

Q12. How have you been personally affected by ‘pre-charge bail’ or ‘released under

investigation’?

Q13. If you have been affected, how do you think the system could be improved?

Thank you for participating in this consultation.

Impact of Proposals

Equalities Statement

Section 149 of the Equality Act 2010 places a duty on Ministers and Departments, when exercising their functions, to have ‘due regard’ to the need to eliminate conduct which is unlawful under the 2010 Act, advance equality of opportunity between different groups and foster good relationships between different groups. We will undertake a full assessment of the impact of our final proposals following this consultation.

Eliminating unlawful discrimination

In general, young people (16-25 years old), people from black and minority ethnic (BME) backgrounds and those with mental health problems and learning disabilities are more likely to be involved with the criminal justice system and are therefore more likely to be placed on pre-charge bail. We do not consider that any other groups with protected characteristics are over-represented among those who are placed on pre-charge bail or RUI by the police.

Initial analysis suggests racial disparities in those groups arrested, with black individuals 3.5 times more likely to be arrested than those from the white group. As bail can only be applied post-arrest, our changes may also result in similar disparities in the use of pre-charge bail. Similarly, we would expect men and individuals over 21 to be over-represented, with 86% of those arrested male, and 82% of all arrestees over 21. Further analysis is necessary.

However, there may also be benefits to BME communities, men and young people if changes lead to better or quicker investigations as data suggests they are more likely to be subject to or experience crime. The public generally could benefit from these reforms if they improve the efficiency of investigations and therefore the public’s confidence in the police.

Advancing equality of opportunity between different groups

We do not consider that these proposals would have any particular impact on the achievement of this objective.

Fostering good relationships between different groups

We do not consider that these proposals would have any particular impact on the achievement of this objective.

About you

Please use this section to tell us about yourself. Please note you are completing this section voluntarily; your details will be held securely according to the data protection legislation. More information on what data we are collecting, why and how it will be look after can be found at: Police powers: pre-charge bail.

We have not asked you for any personal data, however your opinions may constitute personal data and by responding electronically we will have your IP address and/or your email address. These personal data will be deleted after the response to the consultation have been published.

What region are you in?

- North East

- North West

- Yorkshire/Humberside

- East Midlands

- West Midlands

- Wales

- South East

- South West

- Greater London 10.Scotland 11.Northern Ireland 12.Other (please specify)

If relevant, which if any, best describes you/your organisation?

- Victim of crime/survivor

- Witness

- Individual currently or previously under investigation

- Member of the public

- Police/law enforcement

- Local authority

- Charity / voluntary sector

- Civil society group

- Legal practitioner 10.Academic / thinktank 11.Other (please state)

Name of company/organisation (if applicable)

Contact details and how to respond

You may respond to the questions in this consultation online.

Alternatively, you can send in electronic copies to: pacereview@homeoffice.gov.uk; or Alternatively, you can respond by post:

Pre-charge Bail Consultation

A2 6 Floor Fry

2 Marsham Street

SW1P 4DF

Complaints or comments

If you have any complaints or comments about the consultation process you should contact us at the address above.

Extra copies

An electronic copy of this consultation can be found Police powers: pre-charge bail.

Alternative format versions of this publication can be requested from the Home Office at the above addresses.

Publication of response

We aim to publish a Government response to this consultation within three months of it closing. The response will be made available online at the above address.

Representative groups

Representative groups are asked to give a summary of the people and organisations they represent when they respond.

Confidentiality

Information provided in response to this consultation, including personal information, may be published or disclosed in accordance with the access to information regimes (these are primarily the Freedom of Information Act 2000 (FOIA), the Data Protection Act 1998 (DPA) and the Environmental Information Regulations 2004).

If you want the information you provide to be treated as confidential, please be aware that, under the FOIA, there is a statutory Code of Practice with which public authorities must comply and which deals, amongst other things, with obligations of confidence. In view of this it would be helpful if you could explain to us why you regard the information you have provided as confidential. If we receive a request for disclosure of the information, we will take full account of your explanation, but we cannot give an assurance that confidentiality can be maintained in all circumstances. An automatic confidentiality disclaimer generated by your IT system will not, of itself, be regarded as binding on the Home Office.

The Home Office will process your personal data in accordance with the DPA and in most circumstances, this will mean that your personal data will not be disclosed to third parties.

Annex A: An initial look at data and published literature on Pre-charge Bail

As part of the Government’s review into pre-charge bail (PCB), we are reviewing the data and evidence on PCB to help develop the evidence base. This will focus on how the use of PCB and released under investigation (RUI) has changed since the reforms, the potential impact of these changes, and the wider effectiveness of PCB.

Data on pre-charge bail and released under investigation

Before the reforms to PCB were introduced on the 3rd April 2017, data on PCB were not collected systematically or consistently. This makes it difficult to provide a national picture of how PCB was used before the reforms. Since the reforms, data on PCB has become a part of the annual data requirement (ADR). These experimental statistics have been included in the Home Office’s Police Powers and Procedures publications since 2018 (Home Office, 2018; 2019). These provide data on how many individuals were released on PCB each year and average durations. However, police forces and HMICFRS have raised concerns with the quality of the data, highlighting that there were often partial returns, and that there is a lack of consistency between police forces in recording PCB data. Hence, these statistics only give an indicative picture of current usage and should be treated with caution. There are currently no data given as part of the ADR on the number of individuals released under investigation.

Some insight can be gained from FOIs to forces on their use of PCB[footnote 5]. The Law Society (2019) published a report that looked into the use of released under the investigation by the police in the UK. The report includes data from an FOI request submitted by law firm Hickman & Rose Solicitors. 31 forces returned FOI data including 29 police forces in England and Wales, the British Transport Police (BTP) and Police Service Northern Ireland (PSNI). The following analysis looks at data from 29 territorial police forces in England and Wales (excluding BTP). Data from PSNI have also been excluded from the analysis as Northern Ireland was not affected by the 2017 reforms. This analysis showed that, for forces which had provided data, there had been an 84% decrease in the number of individuals on PCB between 2016/17 and 2017/18, from approximately 203,000 to 32,000. Moreover, in 2017/18, a year following the reforms, approximately 177,000 individuals were RUI. Data on the average length of pre-charge bail and RUI provided by 9 police forces showed that, in most of these forces, individuals were on were RUI for longer periods in 2017/18 than they were when under PCB in the same year. The only exception to this was data provided by the Metropolitan Police, where the average length of bail in 2017/18 was 165 days compared to the average length of RUI in 2017/18 which was 79 days. Overall these findings were similar to those from other sources (BBC, 2019; College of Policing, 2017). Likewise, the average (median) time taken to charge suspects has gradually increased from 14 days in 2015/16 to 23 days in 2018/19 (Home Office, 2019). However, we cannot infer that the increase in durations is simply the result of the greater use of RUI and the reduction in the use of PCB. Generally average investigation durations, where suspects have been identified, have been increasing in recent years. This is thought to be partly in response to increased levels of demand on the police, including more reporting of complex crimes and the increased need to examine digital evidence.

Further evidence/literature on pre-charge bail and RUI

An initial review of the research evidence on PCB and RUI has revealed there is some evidence that police behaviour has changed in response to the reduced use of PCB and greater use of RUI. Some commentators have suggested that the police are using RUIs as an administrative tool to help manage their workload. It has been claimed that RUIs are believed to require lower managerial oversight compared to when individuals are given pre-charge bail (Cape, 2019). RUI in this sense may be particularly appealing against the background of growing demands and pressured resources.

The evidence base around the effectiveness of the use of PCB, and its conditions, appears limited. Few studies have so far been identified on the extent to which PCB conditions may change suspects behaviour, increase victims’ sense of security or keep victims supporting investigations. Some commentators, particularly victims’ and women’s charities, have raised concerns around the decreased use of PCB and the increased use of RUI (Learmouth, 2018; The Centre for Women’s Justice, 2019). Some studies of the victims of sexual offences have found that they feel protected by bail conditions, as it is perceived that they may prevent further victimisation, and so relieve feelings of anxiety (Ibid.). Additionally, it is suggested that victims are less likely to be kept informed of the progress of the investigation when someone is RUI compared to being released on pre-charge bail. Equally however, some researchers have suggested that the pre-reform arrangements could sometimes leave victims feeling unsupported in cases where breaches were reported but then not acted upon (Learmouth, 2018).

References

BBC. (2019). ‘Scandal brewing’ as thousands of suspects released. [Accessed 5th December 2019].

Cape, E. (2019). Police bail without charge – leaving suspects in limbo. [Accessed 6th December 2019].

The Centre for Women’s Justice. (2019). Super-complaint: police failure to use protective measures in cases involving violence against women and girls. [Accessed 5th December 2019].

College of Policing. (2017). Pre-charge bail data. [Accessed 9th December 2019].

Home Office. (2019). Police powers and procedures, England and Wales year ending 31 March 2019. [Accessed 5th December 2019].

Home Office. (2018). Police powers and procedures, England and Wales year ending 31 March 2018. [Accessed 5th December 2019].

The Law Society. (2019). Release under investigation. [Accessed 4th December 2019].

Learmouth, S. (2018). A system to keep me safe: An exploratory study of bail use in rape cases. Dissertation: London Metropolitan University [Accessed 6th December 2019].

-

Cases where the offences incur significant adverse impacts, whether physical, emotional or financial, upon individuals or the wider community. ↩

-

Police data available from the Home Office Data Hub cover date of crime recording and date an outcome is recorded for that crime. The time between these two dates can be considered investigation time, though the data is not able to identify specifically those cases where pre-charge bail was applied. ↩

-

Crime outcomes in England and Wales 2017 to 2018; Crime outcomes in England and Wales 2018 to 2019 ↩

-

These figures relate to the time between an offence being recorded and an outcome being assigned. There are no national data on the time between arrest and outcome. However, in most cases where an arrest takes place it will tend to occur relatively soon after an offence is recorded. ↩

-

Data on pre-charge bail has been published in the Home Office’s Police Powers and Procedures statistical bulletins since 2018. However, these data do not cover the use of pre-charge bail prior to the reforms nor the use of RUI. We have drawn on data published by the Law Society (2019) because this allows us to compare the use of pre-charge bail before and after the reforms. These data also give some insight into the use of released under investigation (RUI). Comparing force level pre-charge bail data from the Home Office ADR and Law Society FOI reveals discrepancies between the two sets of figures. It has not yet been possible to establish why these differences exist. ↩