Government response to consultation and summary of public responses (accessible)

Updated 2 October 2023

Published: 30 August 2023

Executive summary

1. On 18 April 2023, the Home Office launched a consultation on ‘new knife legislation proposals to tackle the use of machetes and other bladed articles in crime’. The consultation closed on 6 June 2023. This report summarises respondents’ views on the consultation proposals and the government’s response and next steps.

2. The consultation sought views on proposed changes to legislation concerning knives, including machetes, and other bladed articles in crime. The consultation asked for views on the following proposals:

i. Proposal 1: Introduction of a targeted ban of certain types of machetes and large knives that seem to be designed to look menacing with no practical purpose.

ii. Proposal 2: Whether additional powers should be given to the police to seize, retain and destroy lawfully held bladed articles of a certain length if these are found by the police when in private property lawfully and they have reasonable grounds to suspect that the article(s) are likely to be used in a criminal act.

iii. Proposal 3: Whether there is a need to increase the maximum penalty for the importation, manufacture, sale and supply of prohibited offensive weapons (s141 of the Criminal Justice Act 1988 and s1 Restriction of Offensive Weapons Act 1959) and the offence of selling bladed articles to persons under 18 (s141A of the Criminal Justice Act 1988) to 2 years, to reflect the severity of these offences.

iv. Proposal 4: Whether the Criminal Justice System should treat possession in public of prohibited knives and offensive weapons more seriously.

v. Proposal 5: Whether there is a need for a separate possession offence of bladed articles with the intention to injure or cause fear of violence with a maximum penalty higher than the current offence of possession of an offensive weapon under s1 of the PCA 1953.

3. We developed these legislative proposals to tackle the use of machetes in crime in response to concerns raised by the National Police Chiefs’ Council (NPCC) about their increasing prevalence on the streets. During our conversations with the police, swords were not raised as a specific concern and in discussion with the NPCC, we agreed to focus on zombie-style machetes and knives in this consultation. However, we will keep this under review, should any operational need arise to extend the ban to swords and other bladed articles or offensive weapons.

4. The consultation was open to the public. We wrote to over 150 stakeholders directly, inviting them to provide input, and raised awareness of the consultation through the media, Parliament and various stakeholder groups. Prior to and during the consultation, we engaged with key criminal justice system partners and directly affected businesses and organisations. We listened closely to the views of those directly affected by the devastating effects of knife crime. This was to ensure a wide range of views could be considered for policy development.

5. The proposals cover matters that are devolved, and which apply only to England and Wales. Any legislative proposals considered necessary would apply in relation to England and Wales only, but we will work closely with the devolved administrations on how specific proposals might apply to or affect Scotland and Northern Ireland.

6. The consultation received a total of 2,544 responses. Not all respondents answered every question; therefore, figures provided are based on the responses received for each question via both the online survey and email. All responses have been analysed and given full consideration in the preparation of this government response. We would like to thank everyone who took the time to respond.

7. People could respond to the consultation either via an online survey through gov.uk or by e-mail to the machetes-knives-consultation@homeoffice.gov.uk Consultation mailbox. The vast majority of the responses were received online, however, some members of the public, police forces and industry professionals responded by email.

8. The breakdown of the number of responses received by each medium is:

-

Online Survey: 2,393 (94%)

-

Email: 151 (6%)

9. Of the total 2,544 responses, approximately 42 were submitted on behalf of organisations, with the remainder submitted by members of the public, including practitioners responding in their individual capacity.

10. Respondents included businesses, charities, organisations working with children at risk, outdoor enthusiasts, collectors, gardening associations, museums and enforcement agencies.

11. The government has analysed all the responses, which are summarised in this document. Most responses were supportive of the proposals. However, a number of respondents raised concerns in relation to proposals 1 and 2, which are discussed in detail later in this document.

12. Several key themes were raised in the responses, including:

i. Concerns that banning certain types of knives and machetes would have a negative impact on people’s legitimate need for, and use, of knives. Respondents opposed to the ban were of the view that legislation and government action should focus on targeting criminals rather than introducing blanket approaches that have the potential to disrupt legitimate use.

ii. Some respondents offered the view that any restrictions on machetes should not infringe upon the legitimate activities of those who wish to use machetes as tools but supported a ban if the legislation clearly focused only on those machetes that ‘seem to be designed to look menacing and not as agricultural tools or tools to be used outdoors’.

iii. Some respondents, including collectors and re-enactment groups, raised concerns about items of historical interest being prohibited as an unintended consequence of a ban of certain machetes and large outdoor knives and suggested that the legislation should include a defence for items of historical importance or interest. Some respondents also suggested that items traditionally crafted by hand should be exempted, similar to the defences in existence for swords with curved blades.

iv. Concerns that the police power to seize bladed articles held legally in private premises may lead to the police arbitrarily taking private property from law-abiding citizens.

v. Some respondents, including practitioners working with young people, suggested that proposals 3-5 may impact negatively on young people who may carry knives in public for self-defence purposes or because they are coerced into carrying the article.

13. These themes are explored in further detail throughout the following sections that consider responses to each of the proposals in the government’s consultation.

14. The government is grateful for all the responses received and took careful consideration of the views and evidence provided. The responses have informed the proposed measures, and the government will seek to introduce legislation for the following proposals when parliamentary time allows.

i. Banning certain types of machetes and knives which seem to have been designed not as tools and seem to be designed to look menacing and suitable for combat.

ii. New police power to seize, retain and destroy lawfully held bladed articles in private premises if the police are in the property lawfully and have reasonable grounds to suspect that the article will be used in crime.

iii. Increase the maximum penalty for the offence of importation, manufacture, sale and general supply of prohibited and dangerous weapons and the sale of knives to persons under 18 years old to 2 years.

iv. New possession offence of bladed articles with the intention to endanger life or to cause fear of violence.

15. In addition, the government will ask the Sentencing Council to consider amending the Sentencing Guidelines relating to possession of bladed articles and offensive weapons so that possession of a prohibited weapon is treated more seriously than possession of a non-prohibited weapon.

16. We will continue to engage with key partners as we develop and implement any legislative changes.

Consultation responses

Question 1: Do you agree that the government should take further action to tackle knife crime, and in particular the use of machetes and other large knives in crime?

1. We asked respondents to tick one of the following responses and explain the reason for their answer. The provided responses were:

- Yes

- No

2. Of the 2,388 respondents who answered this question, 53% agreed that the government should take further action to tackle knife crime, in particular the use of machetes and other large knives. The remaining 47% disagreed that further action needs to be taken.

3. Of those who responded ‘No’ to this question, the main concerns raised were that amending legislation would have little effect on knife crime or that doing more to tackle knife crime would adversely affect those who have a legitimate need to use knives.

Proposal 1 - Banning certain types of knives and machetes which we suggest have no practical use and seem to be designed to look menacing and suitable for combat.

Question 2: Do you agree with the proposal?

4. We asked for views on adding certain types of knives and machetes to the list of prohibited weapons under S141 of the CJA 1988. We asked respondents to tick one of the following responses and explain the reasoning for their answer. The provided responses were:

- Yes

- No

5. There was a total of 2,443 responses to this question.

6. Of those who responded to this question, 893 respondents (37%) agreed with the proposal to ban certain knives and machetes which seem to be designed to look menacing and suitable for combat and 1,550 (63%) selected that they did not agree with the proposal.

7. The most common reason provided for not supporting the proposal was that it would affect people’s legitimate need to use knives and machetes for work purposes and for leisure. Some respondents were concerned that they would not be able to use machetes in rural environments, where it would not be feasible or desirable to use an alternative, powered tool. Some other respondents were concerned that the ban would impact on the ability of outdoor enthusiasts to pursue activities where a machete is needed to clear a patch to set camp, etc.

8. Respondents were also uncertain of how effective this change would be in tackling knife crime and expressed the view that the government should focus its efforts on those who use knives as weapons, rather than on measures that will impact on the wider population.

9. A significant number of respondents also argued that the addition of these style of knives to the list of offensive weapons would be open to interpretation; therefore, they emphasised the strong need to be clear on the definitions and descriptions of the knives and machetes the government intends to ban.

10. Comments from those who responded ‘yes’ to this question included the view that there is little to no need for people to own the knives described in the consultation. Others were of the opinion that alternatives could be found and used.

Question 3: Looking at the common features present in the knives and machetes we are proposing to ban, do you agree that any legal description should refer to:

a) The article containing both smooth and serrated cutting edges

b) The article containing more than one hole

c) The article being of a certain length

d) Any other features that should be included in the legal description

11. We sought views on the three features outlined above in parts a), b) and c) of this question. These features, which are prevalent in ‘zombie-style’ knives, seem to be attractive to those who wish to use a machete as a weapon rather than a tool – multiple cutting edges which combine plain and serrated edges, holes and shapes that are closer to the fantasy knife than the utility knife. Industry professionals highlighted that these features make them unsuitable for the various legitimate, practical purposes that machetes are designed for.

a) The article containing both smooth and serrated cutting edges

12. We asked respondents to tick one of the following responses and explain the reasoning for their answer. The provided responses were:

-

Yes

-

No

13. There was a total of 2,386 responses to this question.

14. Of those who responded to this question, the majority (68%) did not think that a legal description should refer to the article containing both smooth and serrated cutting edges. The remaining 32% were in agreement that a definition should include both serrated and smooth cutting edges.

15. Respondents opposed to including this feature in the description of the knives we want to ban flagged that smooth and serrated edges are needed in most outdoor knives and machetes and that the two types of edges are included for a good reason, such as cutting branches or wire. Conversely, those in favour argued that any legal definition needs to be as specific as possible.

16. There were a small number of online responses (125) that answered either ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to this question that appeared to have interpreted the question as asking whether a blade should have either a smooth or serrated edge.

b) The article containing more than one hole

17. We asked respondents to tick one of the following responses and explain the reasoning for their answer. The provided responses were:

-

Yes

-

No

18. There was a total of 2,330 responses to this question.

19. Of those who responded online to this question, 70% thought that any legal description should not refer to the article containing more than one hole. The remaining 30% did agree that a definition should include the number of holes.

20. Those respondents who did not think a description should include the feature of containing more than one hole argued that it would affect legitimate uses of knives. Examples of legitimate use included holes being made in the blade to reduce its weight, thereby, making it easier to carry. Also, many responses noted that they did not think focussing on the number of holes would be effective in tackling knife crime.

21. Industry professionals pointed out to us that the more holes in the blade, the less effective it is as a tool and less likely that a machete designed as tool would have multiple holes. Approximately 5% of those who answered ‘yes’ and 21% of those who responded ‘no’ to this question appeared to either share this view or they were unclear what difference a certain number of holes makes to a blade and therefore, unsure why it should be included as a feature.

22. Some responses commented that there is a need to be clear on where the holes in the knife would be, whether it would include holes in the handle and/or the blade.

c) The article being of a certain length

23. We asked respondents to tick one of the following responses and explain the reasoning for their answer. The provided responses were:

-

Yes

-

No

24. There was a total of 2,353 responses to this question.

25. Of those who responded to this question, 73% did not agree that any legal description should refer to the article being of a certain length.

26. A concern raised by 27% of those who responded ‘no’ to this question was that it would adversely affect those who have a legitimate reason to use these knives. Another reason shared by 26% of respondents who answered ‘no’ was that including length in the description would be ineffective in tackling knife crime.

27. Respondents who did not agree with length being one of the features in the description argued that the longer the knife, the more difficult it is to conceal; therefore, it is less likely the item would be used in crime. Other respondents were against a focus on length for the opposite reason: they thought that items of any length could be used in crime and therefore, the government should go further and look at restricting items of any length.

d) Are there any other features that should be included in the legal description?

28. We wanted to give respondents the opportunity to share any other features they thought should be included in the legal description. This was a free text question.

29. There was a total of 1,394 responses to this question.

30. Of those who provided a response, 127 suggested another feature with a further 127 responses providing suggestions on the policy. Other responses provided were not deemed to offer a different feature which the government could consider including in any description.

31. The other features suggested by respondents included but were not limited to: the colour of the blades, spikes on handles, the angle or shape of the blade, the weight of the blade, material of the blade and a blade being disguised as something else.

Question 4: Looking at the length of the types of knives and machetes we are proposing to ban, we invite views on whether the minimum length should be:

a) 8” (20.32cm)

b) 9” (22.86cm)

c) 10” (25.4 cm)

d) Any other length?

32. This was a multiple-choice question, with respondents able to select one option. There was a total of 1,847 responses to this question.

33. Of those who responded:

-

22% chose option a;

-

1% chose b;

-

5% chose c; and

-

72% chose d.

34. Of those who selected option ‘d’, 23% of respondents said that there should be no minimum length, meaning that the government should not stipulate length as an identifying feature.

35. A total of 129 suggestions for ‘other length’ were provided. These ranged from as little as 1cm up to 2,000 inches. There were a small number of suggestions between the ranges of 2 to 5 inches and similarly between the range of 12 and 24 inches.

Question 5: We would like to understand whether and to what extent machetes and large outdoor knives may be needed currently in the UK.

36. The government is not proposing to ban machetes that have legitimate uses for agricultural or other purposes. Therefore, we sought to better understand the full range of legitimate uses.

37. A total of 2,104 responses were received to this question.

38. In summary, the following legitimate uses were highlighted: agriculture, forestry, camping, bushcraft, gardening, fishing, diving, shooting and conservation, clearing waterways and collecting special interest knives or antiques.

Government response

39. The government’s position is that more needs to be done to tackle the use in crime of ‘zombie-style’ knives and machetes. Having considered the responses in detail, the government will seek to introduce a ban on certain types of large knives that seem to appeal to those who want to use these items as weapons– for instance, zombie style knives or certain types of machetes.

40. The government notes that some respondents argued that any definition should be broad and not too prescriptive. However, we need to provide clarity to enforcement agencies, sellers, importers, and owners in general so they can make an assessment of whether an item they already possess, they intend to possess, or manufacture and sell is legal or is prohibited. In addition, any legal definition cannot be so broad as to capture bladed articles which are out of the scope of this ban.

41. The government is currently considering a description of the items we wish to ban. Following feedback from respondents, we are looking at the following features:

-

Cutting edges – plain and serrated

-

Sharp pointed end

-

Length of the blade

-

Holes in the blade

-

Other features - spikes, protuberances, hooks

42. Serrated/Smooth cutting edge: Many respondents were concerned about the description of the machetes and knives we want to ban including a serrated edge. They were concerned that we may ban knives with one serrated edge, such as bread knives and some cheese knives. Our current thinking is that for a bladed article to be banned under our proposals, the item would need to have both a cutting and serrated edge, in addition to some other features included in the description.

43. More than one hole: The industry experts we engaged were of the view that one hole is often a feature of outdoor knives and some machetes, and the hole is there so the knife can be hung up. Hence, we have included in the description ‘more than one hole’, with the intention to avoid capturing knives and machetes commonly used, and designed, as tools.

44. Length: The majority of respondents who responded to this question argued that knives of any length could be dangerous if used as weapons and that length should not be relevant to the description of the machetes and knives we want to ban, since setting any length would limit the impact of the legislation and limit police powers to seize the items.

45. We consider that we need to set out a minimum length for an item to be captured by the ban in order to avoid unintended consequences, such as banning utility knives needed for day-to-day tasks. Our intention is to set the length at 8 inches, as this is the shortest length and the second most preferred option for respondents.

46. Other features: We have considered the suggestions for additional features provided by respondents such as colour, material and weight. Some respondents suggested including wording and images inciting violence. However, we believe that the features we propose to include in the description strike the right balance between capturing a wider range of designs without being too prescriptive, and at the same time provide the clarity that sellers, owners, purchasers, enforcement agencies and courts need in order to unequivocally identify whether an item is prohibited or not.

47. The government is also considering whether to include a defence for items of historical importance.

48. We have set out below some examples of the types of knives that we are looking to include in scope of the ban.

20” / 50cm ‘Zombie style’ machete.

17.3” / 44cm Desert style machete

15” / 38cm Fantasy Hunting Knife

10.5” / 26.5cm Fantasy knife

9.5” / 24.13 cm kukri- machete hybrid

9” / 22.86 cm Rambo style knife

18” / 45.72 cm Cutlass style machete

49. We have set out below some examples of blades which we are not looking to include in scope of the ban. These blades were mentioned by some respondents who were concerned that the ban might capture these legitimate tools.

Machetes with mainly blunt tips

Billhooks and scythes with one cutting edge

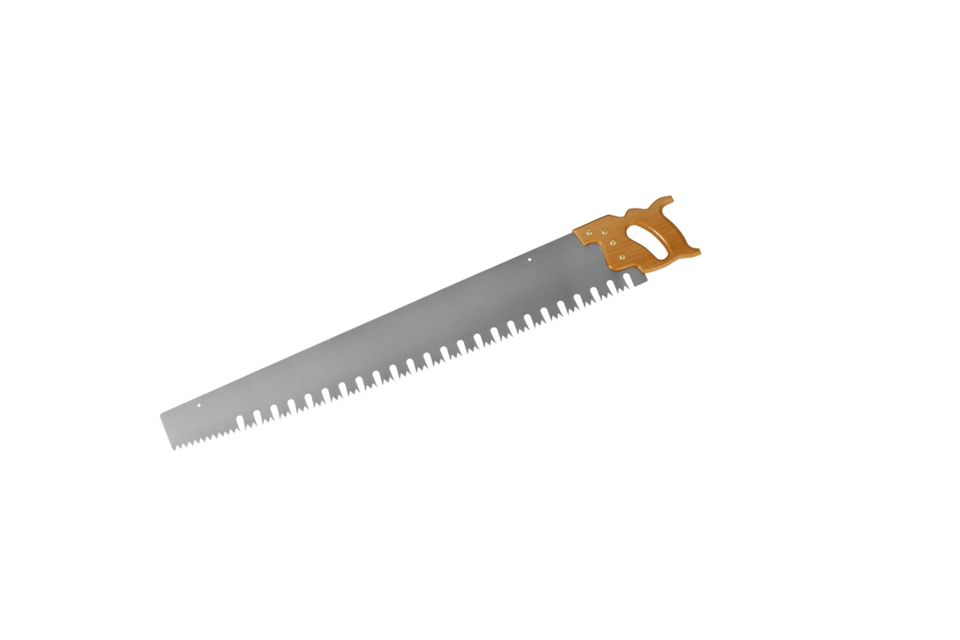

Hand saws and knives with one type of cutting edge -either smooth or serrated

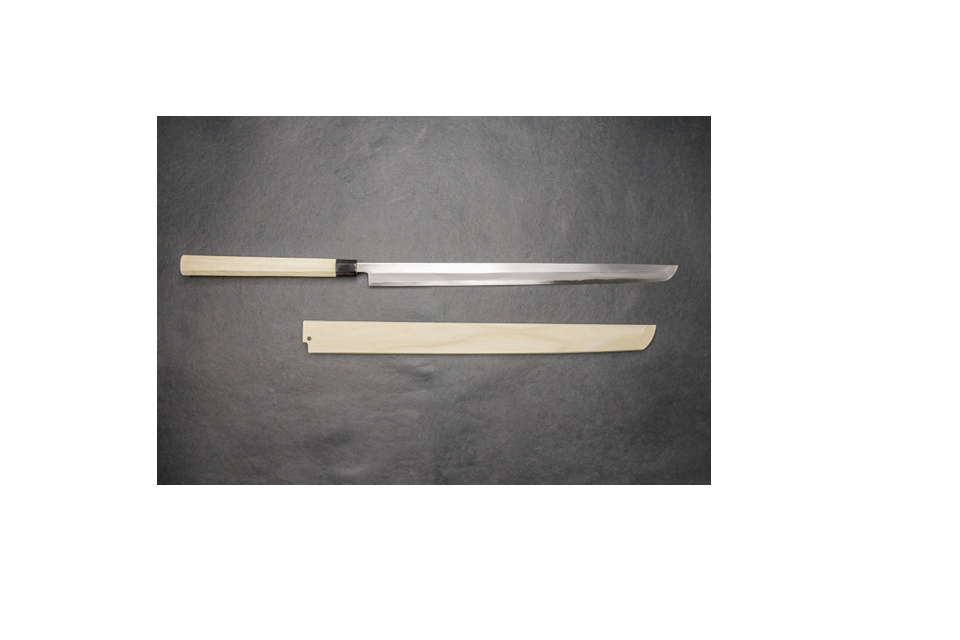

Maguro Bocho (Tuna Knife)

Two handle saws and knives, even if they have two types of cutting edge or holes in the blade

50. The government is confident that these specifications will allow the majority of people who use machetes as tools for legitimate reasons to be able to continue to do so, and those who use knives that are captured by the ban for legitimate reasons will be able to find an appropriate alternative.

51. We will keep the list of prohibited offensive weapons under review, including whether there is operational need to extend the ban to particular swords and other bladed articles or offensive weapons in the future.

Proposal 2 – Power to seize and retain/destroy certain bladed articles held in private if the police are in private property lawfully and they have a reasonable grounds to suspect that they could be used in serious crime.

Question 6: Do you agree that the proposed new power is necessary and proportionate?

52. We asked respondents to tick one of the following responses and explain the reasoning for their answer. The provided responses were:

-

Yes

-

No

53. There was a total of 2,379 responses to this question.

54. Of the responses we received to this question, 58% did not agree with the proposal, and 42% agreed that the proposed new power is necessary and proportionate.

55. The main concerns raised were around the power being open to interpretation and applied arbitrarily or incorrectly by the police and the possibility of it affecting people who have a legitimate use for knives.

56. Other responses were supportive of a power that would help prevent future offending and protect future victims of violence or crime. It was also noted that the power could be very useful in situations of domestic abuse where there are significant risks but currently no powers to seize weapons.

57. Responses also indicated the need for having an avenue of redress to contest the decision made by the police (further comments were made on this point in response to Q8).

Question 7: We invite views in relation to whether the powers should apply to any knife in private property or only to knives of a certain length.

a) Any knife held in private property

b) Knives of a certain length

58. This was a multiple-choice question, with respondents able to select one option. There was a total of 1,548 responses to this question with a total of 996 that chose to leave this question unanswered.

-

32% chose option a;

-

29% chose option b; and

-

39% did not select an option.

59. Some respondents, including those who chose either option ‘a’ or ‘b’, thought that there should have been a third option to cover the view that the respondent did not agree with either option and the proposal should not apply to any knife.

60. Some respondents who selected option ‘a’ provided comments that the power being applied to any knife would capture any knife that could be used in crime and avoid any loopholes around length arising.

61. Some respondents who selected option ‘b’ provided comments that if the power was applied to any knife, it would capture kitchen knives.

Question 8: We invite views from respondents as to whether there should be a right of appeal to the courts in order to recover an item seized or if the avenue of redress should be only through the police complaints process.

62. We sought views on whether there should be a right of appeal to the courts or an avenue of redress in order to recover an item seized by the police.

63. A total of 1,933 respondents answered this question. The most common response was agreement that there should be a right of appeal. The second most common response was from respondents agreeing that there should be a course for people to appeal, but respondents were not clear on what their preferred option would be. A total of 107 respondents explicitly stated that they thought the avenue of redress should be only through the police complaints process.

64. There were concerns raised about the courts’ capacity to be able to deal with such appeals.

Government response

65. The government want to ensure that the police have at their disposal the necessary tools to disrupt knife crime. However, as demonstrated in case studies 1-3 in the consultation document, at present if the police find a machete or any other legal article with a blade in someone’s home and they have reasonable grounds to suspect that the items will be used in serious violence or serious crime, they cannot act unless the item is considered to be evidence in a criminal investigation.

66. The government will, therefore, seek to introduce additional powers for the police to seize, retain and destroy lawfully held bladed articles if these are found by the police when in private property lawfully and they have reasonable grounds to suspect that the article(s) are likely to be used in serious violence or in serious crime.

67. The government is clear that this power could only be used if the police is lawfully in private premises and any bladed article could only be seized if the police have reasonable grounds to suspect that the item could be used in serious violence or serious crime. The onus would be firmly on the police to justify why they suspect the item is likely to be used in crime. Many of the concerns expressed by respondents were made on the assumption that the police would be granted powers to enter premises to look for bladed articles that could be used in crime. This is not what we are proposing. The police would be able to use this power only if they are already lawfully in the premises, for instance, if they already have a power of entry in relation to an offence.

68. The government is proposing that any objections to a seizure under this power are dealt with via the internal police complaints process directly by the relevant police force or via the Independent Office for Police Conduct (IOPC). If the complainant disagrees with the decision of the police or the IOPC, it would be possible to appeal to a court.

69. We will continue to develop this proposal, taking into account the concerns expressed and will legislate when parliamentary time allows.

Proposal 3 – Increase the maximum penalty for the offences of sale, etc of prohibited and dangerous weapons and sale of knives to persons under 18 to 2 years.

Question 9: Do you think that the offences of selling knives to persons under 18 and selling prohibited offensive weapons are of such severity that they should have a maximum penalty of 2 years?

70. We asked respondents for their views on increasing the maximum sentence for the offence of selling knives and the offence of selling prohibited offensive weapons to people under 18 to 2 years. We asked respondents to tick one of the following responses and explain the reasoning for their answer. The provided responses were:

-

Yes

-

No

71. There was a total of 2,348 responses to this question.

72. The majority of respondents (59%) agreed with this proposal.

73. There were a number of respondents who thought that the maximum sentence of 2 years was not going far enough, and that the maximum sentence should be longer.

74. Some responses noted that those who do sell knives and carry out the necessary checks should not be penalised if the person buying the knife uses someone else’s or a fake form of ID.

75. Some respondents, including practitioners working with young people, suggested that this proposal may impact negatively on young people who may carry knives in public for self-defence purposes or because they are coerced into carrying the article.

Government response

76. The purpose of this measure is to increase the maximum penalty for the most serious cases where knives are sold to persons under 18. This measure is not intended to be used to charge sellers who have carried out all the reasonable steps to verify age and had no reason to believe the individual was under 18. The current legislation already includes a ‘due diligence’ defence if the seller shows that they took all reasonable steps to verify age.

77. This measure will also bring the offence within the remit of PACE powers, which is key to the police’s ability to investigate some of the more serious offences, for example, those who sell knives privately to under 18s, or those who sell prohibited weapons through social media or personal messaging applications.

78. We have noted the concerns raised by some respondents that vulnerable young people may be coerced into carrying and supplying knives and may be negatively impacted by this proposal. However, courts will always consider each case individually and will take into account individual circumstances and mitigating factors, such as age, lack of maturity and vulnerability.

79. The government is clear that it is unlawful to carry knives for self-defence purposes. The Prevention of Crime Act 1953 makes it an offence to carry offensive weapons in a public place, without lawful authority or reasonable excuse. Carrying a knife is likely to entice knife crime in local communities rather than discourage it and will put young people at risk as a result.

80. The government will seek to increase the maximum penalty for the importation, manufacture, sale and supply of prohibited offensive weapons and the offence of selling bladed articles to persons under 18 to 2 years when parliamentary time allows.

Proposal 4 - The Criminal Justice System should treat possession in public of prohibited knives and offensive weapons more seriously.

Question 10: Should the Criminal Justice System treat those who carry prohibited knives and offensive weapons in public more seriously?

81. We asked respondents for their views on whether the possession of a prohibited knife in a public place should be treated more seriously. We asked respondents to tick one of the following responses and explain the reasoning for their answer. The provided responses were:

-

Yes

-

No

82. There was a total of 2,333 responses to this question.

83. The majority of responses (65%) agreed with this proposal with comments from some respondents talking about the devastating impact knife crime has on lives and communities and that this change will better reflect the severity of the crime.

84. Some respondents, including practitioners working with young people, suggested that this proposal may impact negatively on young people who may carry knives in public for self-defence purposes or because they are coerced into carrying the article.

Government response

85. We note concerns raised in relation to this proposal having the potential to impact on vulnerable people who may be coerced into carrying knives. Similar concerns were raised in relation to proposal 3. The courts will always consider each case individually and will take into account mitigating factors, such as age, lack of maturity and vulnerability.

86. The government is clear that it is unlawful to carry knives for self-defence purposes. The Prevention of Crime Act 1953 makes it an offence to carry offensive weapons in a public place, without lawful authority or reasonable excuse. Carrying a knife is likely to entice knife crime in local communities rather than discourage it and will put young people at risk as a result.

87. The government will ask the Sentencing Council to consider amending sentencing guidelines on possession of bladed articles/offensive weapons to treat possession of a prohibited weapon in public more seriously.

Proposal 5 - A new possession offence of bladed articles with the intention to endanger life or to cause fear of violence.

Question 11: Do you agree with the proposal?

88. We asked respondents whether they thought the government should introduce a new offence of possession of bladed articles with the intention to endanger life or to cause fear of violence. We asked respondents to tick one of the following responses and explain the reasoning for their answer. The provided responses were:

-

Yes

-

No

89. There was a total of 2,361 responses to this question.

90. The majority of respondents to this question (64%) agreed with this proposal. Respondents in favour of this proposal argued that current legislation does not recognise the severity of carrying a knife with the intention to cause fear and the increased likelihood of escalation resulting in harm or threat to life. Respondents stressed the need to act before the actual act of threatening another person occurs.

91. Some respondents agreed with the proposal, but they shared their views that they thought it would be difficult to prove that there is an intention for an individual carrying a bladed article to endanger life or cause fear of violence.

92. There were also respondents who were of the view that this is already covered under current legislation; the majority of respondents who provided these comments had selected ‘no’ as their answer to this question.

93. Some respondents, including practitioners working with young people, suggested that this proposal may impact negatively on young people who may carry knives in public for self-defence purposes or because they are coerced into carrying the article.

Government response

94. The government will seek to introduce a separate possession offence of bladed articles with the intention to injure or cause fear of violence with a maximum penalty higher than the current offence of possession of an offensive weapon when parliamentary time allows.

95. We believe that there is a gap in knife legislation between simple knife possession and possession and threatening another person. This proposal mirrors existing firearms legislation that has been effectively implemented by prosecutors. We expect that this proposal will support the police in tackling violence before the actual harm has been done and where there is evidence, for example on social media, of taunting or threatening behaviour.

96. We note concerns raised in relation to this proposal having the potential to impact on vulnerable people who may be coerced into carrying knives. The courts will always consider each case individually and will take into account mitigating factors, such as age, lack of maturity and vulnerability.

97. The government is clear that it is unlawful to carry knives for self-defence purposes. The Prevention of Crime Act 1953 makes it an offence to carry offensive weapons in a public place, without lawful authority or reasonable excuse. Carrying a knife is likely to entice knife crime in local communities rather than discourage it and will put young people at risk as a result.

Business and Trade

98. The remaining questions of the consultation captured information from the business and trade sector as well as opinions on protected characteristics. Responses to these questions will be used to update the relevant impact assessments.

99. The government has noted the concerns raised and will consider the full implications of these proposals in an Equalities Impact Assessment. Our analysis suggests people with some protected characteristics may be affected by these proposals more than others, however, we consider that any negative impacts can either be sufficiently mitigated or can be objectively justified as proportionate means of achieving the legitimate aim of tackling serious crime.

Consultation Analysis Methodology

-

The questions stated throughout this document were the questions as worded in the full consultation listed on gov.uk.

-

Consultation responses were analysed and a view also had to be taken on what correspondence constituted a formal response. It was decided not to include incomplete/ partial online survey responses on the grounds that the respondent had not formally submitted the data and may not have intended for their responses to be read.

-

Data from responses to the quantitative (closed) questions in the consultation (i.e. those that invited respondents to choose an answer) were extracted and analysed. All qualitative responses (i.e. those responses to open questions or where a respondent had submitted a letter or email rather than answering specific questions) were also logged and analysed. This was done by coding the responses to identify frequently occurring themes. Findings have been reported in this document.

-

There is an element of subjectivity when coding qualitative responses, this has been minimised by carrying out additional quality assurance.

-

A number of detailed consultation responses were received that did not adhere to the formal structure and questions posed. These were fed into the government’s response.

-

All percentages have been provided to the nearest whole number.

-

Different questions received different numbers of responses. Therefore, figures are based on the written responses received for each question.

-

The consultation included some multiple-choice and some free text questions. We have included the most common responses to the free text questions.

-

Many free text responses made more than one point. For example, many free text responses identified multiple benefits or multiple challenges. Therefore, the percentages for how many responses expressed each view may add up to more than 100%.

If you have any complaints or comments about the consultation process, you should contact the Home Office at the above address.