Legal Aid Means Test Review

Updated 25 May 2023

Applies to England and Wales

This consultation is being held on another website. Respond online

Ministerial foreword

Everyone deserves access to justice, whatever their financial circumstances. Legal aid is absolutely crucial to a fair justice system because it opens up legal representation to people who would otherwise be unable to pay for it.

In February 2019, the government announced a review of the means test for legal aid as part of the Legal Support Action Plan. We wanted to understand how effective current means testing arrangements are in protecting access to justice, and whether they are working for those who need legal aid most. The review looked at means testing in the round, including the thresholds for legal aid entitlement and the eligibility arrangements for people receiving certain benefits.

The proposals set out in this consultation draw on the review’s findings. They represent a significant investment in our justice system, creating fairer means testing that will protect access to justice in the short, medium and long term, and focus finite public funds on those who are least able to pay themselves.

We are proposing to increase significantly both the income and capital thresholds for legal aid eligibility, and remove the means test entirely for some civil cases. These include legal representation for children, and legal representation for parents whose children are facing proceedings in relation to the withholding or withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment. We also want to remove the upper disposable income threshold for legal aid in the Crown Court, so that anyone can get support if they need it.

We want to do even more to support victims of domestic abuse – for whom legal proceedings can be both traumatic and costly. Under our plans, domestic abuse victims applying for a protective order or other proceedings would benefit from the more generous means test for civil legal aid. And any disputed assets – including property – will not be included in a means assessment. This is much fairer for domestic abuse victims who are contesting a property and who cannot use their equity in that property to fund the legal proceedings.

Our proposals will make a real difference to the way people are able to access legal services – whether they are seeking to protect themselves from harm, to stop their home being repossessed, or to defend themselves at a criminal trial. Our aim for these reforms is to deliver a more dynamic and efficient justice system for the future.

I value greatly the contributions made by all of our stakeholders so far, and extend my sincere thanks to everyone who has shared their views and given evidence to our review. I look forward to their continued engagement in this consultation, as we strive to create a fairer legal aid system that allows every person in our country to access the legal representation they need.

Lord Wolfson of Tredegar

Parliamentary Under Secretary of State for Justice

Executive summary

1) In February 2019, the Ministry of Justice announced the Legal Aid Means Test Review, as part of the Legal Support Action Plan. This paper sets out for consultation our proposed changes to the means test for legal aid.

2) Legal aid pays for legal advice, assistance, and representation for individuals who require these services. Most criminal and civil legal aid is means tested, to ensure that public resources are directed to those most in need.

3) The process of means testing is a vital aspect of determining whether someone qualifies for legal aid. It aims to ensure both that those most in need receive help with paying their legal costs, and that those who can afford to contribute towards their legal costs do so. These principles were set out in the 2010 consultation Proposals for the Reform of Legal Aid in England and Wales, and they form the basis for the proposals set out in this consultation.

4) This has been an open and collaborative review. The Ministry of Justice has held a large number of consultative meetings with a range of interested parties, including legal practitioners from across the legal aid sector, third-sector organisations, the judiciary and academic specialists. This constructive collaboration has helped us form the policies found within this document.

5) We are proposing a wide range of changes to the legal aid means test, with the aim of ensuring access to justice. In some cases, we are proposing to align our approach to civil and criminal legal aid more closely. Specifically, we are proposing:

- to use a cost of living-based approach for the civil legal aid means test, as we already do for the Crown Court and magistrates’ court means test

- to use the OECD Modified approach to adjust gross and disposable income for different household compositions

- to disregard Council Tax from the civil legal aid means test (as for the Crown Court and magistrates’ court means test), and to remove the £545 per month cap on housing costs

- to uprate the existing work allowance for the civil legal aid means test, and to implement a similar allowance into the Crown Court and magistrates’ court means test

- to deduct priority debt and student loan repayments and pension contributions up to 5% of earnings from the disposable income assessment.

6) For civil legal aid, we are proposing:

- a significant increase to the income thresholds, using a cost of living-based approach

- increases to the disposable capital thresholds and the equity allowance

- to disregard compensation, ex-gratia and damages payments for personal harm, and backdated benefit and child maintenance payments, from the capital assessment

- to disregard property which is the subject matter of dispute in the case the individual is applying for legal aid for

- to disregard inaccessible capital, while putting a charge on the asset in question with the aim of recovering the legal aid costs

- to exempt recipients of certain welfare benefits who are not homeowners from the capital assessment

- to require recipients of Universal Credit with household earnings above £500 per month to go through an income assessment, rather than being passported as at present

- a time cap of 24 months on the maximum length of time for which income contributions are payable

- to remove the means test for legal help in relation to inquests which relate to a possible breach of ECHR rights (within the meaning of the Human Rights Act 1998) or there is likely to be a significant wider public interest in the individual being represented at the inquest.

7) For criminal legal aid, we are proposing:

- to increase the income thresholds for legal aid at the Crown Court and the magistrates’ court, to take into account increases in the cost of living and private legal fees

- to remove the upper disposable income threshold for legal aid in the Crown Court

- to increase the maximum contribution period for income contributions at the Crown Court to 18 months, and implement a tiered contribution rate (40%/60%/80%)

- to continue passporting all recipients of relevant means-tested benefits (including Universal Credit) through the income assessment

- to remove the current exemption from paying a capital contribution for homeowners convicted at the Crown Court who are in receipt of passporting benefits

- to align the criminal advice and assistance and advocacy assistance means tests with our proposed new civil legal aid means test.

8) After we have received and considered the responses, we will publish a consultation response outlining our final policies. We will then start the necessary work required to amend legislation and guidance, and make the required changes to Legal Aid Agency digital systems.

Introduction

9) Access to justice is a fundamental principle underpinning the rule of law; and for access to justice to be effective, we must have a legal aid system which is accessible to those who need it.

10) Means testing has played a role in the legal aid system for a very long time, for good reasons; it is important to focus taxpayer resources on those who need them most, rather than on those who can afford to pay for private legal advice and representation.

11) The Rushcliffe Report of May 1945, which established the foundations of the legal aid system in England and Wales as we know it, recommended: “Those who cannot afford to pay anything for legal aid should receive this free of cost. There should be a scale of contributions for those who can pay something towards costs.”

12) Similarly, the consultation Proposals for the Reform of Legal Aid in England and Wales (2010) stated (Chapter 5):

This chapter sets out the Government’s proposals for reform to the eligibility rules for legal aid. The Government’s rationale for reform is to ensure that those who can afford it should pay for, or contribute towards, the costs of their case.

13) However, as a number of respondents to the Post-Implementation Review of the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012 (“LASPO”) pointed out, the legal aid means tests and thresholds have remained static for some years, with only minor changes to eligibility brought in via LASPO and other legislation. We decided, therefore, to take a fresh look at this area.

14) In February 2019, alongside the publication of the Post-Implementation Review, the Ministry of Justice published the Legal Support Action Plan. Amongst other commitments, this announced the Legal Aid Means Test Review, as follows:

We will conduct a review into the thresholds for legal aid entitlement, and their interaction with the wider criteria. This review will assess the effectiveness with which the means testing arrangements appropriately protect access to justice, particularly with respect to those who are vulnerable. The review will include looking at the capital thresholds for victims of domestic violence and evidence gathered during the review of legal aid for inquests. Whilst the review is ongoing, we will continue to passport all recipients of Universal Credit through the means test. We are bringing together data, evidence and expertise from across government to ensure that the process is as consistent as possible. We are also keen to work with experts from across the field to explore this issue. (p. 11)

15) The proposals we have set out represent a significant investment in our justice system which will widen access to legal aid and help ensure individuals can access legal services when they need them.

Scope and structure of the Legal Aid Means Test Review

16) The Means Test Review has considered the legal aid means tests in the round, including not only the income and capital thresholds for legal aid eligibility, but also wider eligibility criteria in relation to means (including benefits passporting), and the income and capital contributions potentially payable towards the costs of representation in civil and family matters and at the Crown Court. We have also specifically considered the experiences of domestic abuse victims. As far as possible, we have revisited the existing rationales for our approach in these areas and further developed these where appropriate.

17) The Means Test Review has not considered the merits and interests of justice tests for legal aid eligibility, the legal aid fee schemes or which services are in scope of legal aid.

18) We appreciate that it is essential that any proposals we make are not only operationally deliverable but straightforward for the Legal Aid Agency to implement and for legal aid applicants and practitioners to understand. We have, therefore, worked closely with the Legal Aid Agency and legal aid providers who have played an essential role in testing and shaping our proposals.

19) This consultation is structured as follows:

20) First, we summarise the existing legal aid means tests and covers our overarching approach for the proposed new legal aid means tests.

- Chapter 1 summarises the existing legal aid means tests.

- Chapter 2 details the framework we are proposing for legal aid eligibility and our proposals for areas that are relevant for both civil and criminal legal aid. These include debt, disregarded types of income and capital, and benefits passporting.

21) Then, we detail our proposals in relation to civil representation and controlled work.

- Chapter 3 lays out our proposals in relation to the income thresholds for civil legal aid, including benefits passporting and income contributions.

- Chapter 4 lays out our proposals in relation to the capital assessment for civil legal aid, including the thresholds, equity disregard, pensioners’ capital disregard, disputed assets (which we consider will particularly benefit victims of domestic abuse), inaccessible capital and benefits passporting.

- Chapter 5 lays out our proposals in relation to legal aid for immigration and asylum and civil legal aid for under-18s. It also considers non-means tested areas of civil legal aid.

22) Finally, we detail our proposals in relation to criminal legal aid, and to implementation and review of the new means tests.

- Chapter 6 lays out our proposals in relation to the Crown Court means test, including income thresholds, benefits passporting and income and capital contributions.

- Chapter 7 lays out our proposals in relation to the magistrates’ court income thresholds and those for criminal advice and assistance and advocacy assistance, including benefits passporting.

- Chapter 8 addresses the implementation of the new means test, including transitional provisions, and considers our approach to future reviews and uprating of the legal aid means tests.

Strategic aims of the Legal Aid Means Test Review

23) The government response to the Reform of Legal Aid in England and Wales Consultation, published in June 2011, set out the four objectives that the package of reforms implemented by Part 1 of the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012 was intended to achieve. These were:

- To discourage unnecessary and adversarial litigation at public expense

- To target legal aid to those who need it most

- To make significant savings to the cost of the scheme

- To deliver better overall value for money for the taxpayer.

24) Objective (b), the targeting of legal aid to those who need it most, has been the governing principle behind the Means Test Review. We have laid out how we are interpreting this objective in more detail in Chapter 2 (paragraphs 87–90)

25) We have also developed three additional strategic aims for the legal aid means test:

Fairness – to ensure that the legal aid means test delivers fair outcomes, enabling people to access justice based on what they are able to contribute towards their legal costs.

Efficiency – to deliver public value, saving cost, time and resource where appropriate for all users.

Sustainability – to be future proofed and adaptive, securing access to justice in the short, medium and long term.

26) Throughout our policy development, we have aimed to balance these strategic aims appropriately, whilst ensuring that our proposals secure access to justice. We have worked closely with legal aid providers and the Legal Aid Agency to understand the administrative burden of the current means test for providers, applicants and the LAA, and to ensure that our proposals reduce administrative complexity whenever possible, and keep it to a minimum.

27) Inevitably there is sometimes a tension between these aims. For instance, we have proposed that priority debt repayments should be deducted as part of the assessment of an applicant’s disposable income. This proposal will require applicants for legal aid to provide evidence to providers and/or the LAA of any agreed debt repayments. However, we think that this additional administrative requirement is justified, because we think it is fair that applicants for legal aid do not have to choose between paying priority debt and paying legal aid contributions or private legal fees.

28) We have set out the rationale behind our proposals throughout this consultation and provided accompanying analysis of the impacts in the accompanying Impact Assessments and equalities assessment. The Impact Assessments indicate that some demographic groups are likely to be particularly affected, both positively and negatively. For civil legal aid, individuals from an ethnic minority, women, those aged 31-40 and those who are Muslim are more likely to be affected. For criminal legal aid, men are more likely to be positively and negatively affected, Muslims are more likely to be negatively affected, and younger adults are more likely to benefit. The proposals are likely to lead to some additional costs for businesses, charities or the voluntary sector. Comments on the Impact Assessments are very welcome.

29) We have addressed future uprating of the means test in more detail in Chapter 8.

Previous consultations

30) As part of our policy development work, we have considered a number of previous consultations covering legal aid eligibility, stretching back to those published by the Lord Chancellor’s Department in the 1990s.[footnote 1] This work has helped us better understand the current system, which has been crucial when considering whether, and to what extent, we should recommend changes.

31) The Means Test Review has also considered responses to two previous government consultation exercises. The first, Legal Aid Financial Eligibility and Universal Credit, published on 16 March 2017 set out proposals to limit the passporting of Universal Credit recipients to those with zero income from employment. No response to this consultation was published; instead, the Means Test Review has addressed this issue and this consultation includes policy proposals in this area. set out proposals to limit the passporting of Universal Credit recipients to those with zero income from employment. No response to this consultation was published; instead, the Means Test Review has addressed this issue and this consultation includes policy proposals on this area.

32) The second, the Review of Legal Aid for Inquests was published on 19 July 2018 as a call for evidence. A response to this call for evidence was published in February 2019; however, this stated that means-testing of legal aid at inquests would be considered separately as part of the Means Test Review.

33) In September 2021, we announced, in our response to the Justice Select Committee’s May 2021 report on the Coroner’s Service , and taking into account relevant responses to the Review of legal aid for inquests, that we would amend regulations to remove the means test for legal representation at inquests via the Exceptional Case Funding (ECF) Scheme. These amendments to regulations have now been made, and came into force on 12 January 2022. We have additionally considered legal help in relation to inquests; our policy proposals are covered in paragraphs 334–342 below.

Accelerated items

34) In December 2020, we laid a statutory instrument (SI) to disregard compensation and ex-gratia payments from specific schemes (such as relevant infected blood support schemes and the Criminal Injuries Compensation Authority) from the capital assessment for civil legal aid. This SI also removed the cap on the amount of mortgage debt that can be deducted from a property’s value, so that all mortgage debt is now deducted. These changes were made to ensure that victims applying for civil legal aid are not disadvantaged by payments they have received from the specified scheme and also ensure that the means assessment reflects more accurately the capital a person has, thus better determining who is most in need of legal aid.

35) As mentioned in paragraph 33 above, as of 12 January 2022 the means test for legal representation at inquests via the ECF scheme has been removed, and non-means tested legal help is available in relation to an inquest for which ECF has been granted for legal representation.

Our approach

36) The Means Test Review has been an open and collaborative process throughout, and we are enormously grateful for the detailed feedback provided by legal aid providers and representative bodies on both the current means tests and on early iterations of our policy proposals.

37) In developing the proposals set out in this consultation, we drew on a range of available evidence, including:

- a wide range of LAA qualitative and quantitative data, including detailed feedback on our proposals from LAA operational colleagues

- feedback on the existing legal aid means test, and suggestions for improvement, from legal aid providers at a series of regional focus groups we ran in February and March 2020, and from a series of interviews we ran with judges across all the relevant jurisdictions at the same time

- detailed feedback on our initial proposals provided by our Stakeholder Advisory Group (which has met regularly since October 2019, except during the period April to August 2020), and from specialists in particular areas of law

- the analytical microsimulation model we have built to estimate the potential costs and equalities impacts of our proposed policies, which draws on data from the Family Resources Survey[footnote 2], the Department for Work and Pensions’ Policy Simulation Model[footnote 3], and the Legal Aid Agency.

38) This consultation is aimed at anyone with an interest in the legal aid means test in England and Wales. This will include, but is not limited to, legal aid providers and their representative bodies, third-sector organisations providing support to those in need of legal advice or representation, members of the judiciary, defendants in criminal proceedings, those who have been, are currently or may in future be involved in civil legal proceedings (whether represented or as litigants in person), academics and others involved in the justice system. A Welsh language summary is available.

Chapter 1: The current legal aid means tests

39) To be eligible for legal aid, an applicant’s legal matter must be in scope for legal aid and they must pass both a merits and a means test. The merits test (for civil legal aid) and the interests of justice test (for criminal legal aid) assess the merits of the case, including the likelihood of success and the benefit to the client. The means test assesses an applicant’s financial eligibility. The exception to this is cases which are exempt from the means test (“non-means tested”).

40) This chapter summarises the existing legal aid means tests, including the current system for when contributions are payable towards the cost of an individual’s legal aid.

41) There are some similarities between the means tests for legal aid for civil and family proceedings, for criminal representation at the Crown Court and at the magistrates’ court, and for criminal advice and assistance and advocacy assistance. However, there are also some significant differences between these tests.

42) Therefore, this chapter first outlines elements that are common to all of these means tests, and then describes each specific means test in detail.[footnote 4]

Structure of means test

43) At present, applicants for most types of means-tested legal aid must go through first a gross and then, in some cases, a disposable income assessment.[footnote 5]

44) The gross income assessment includes not only the means of the individual applying for legal aid, but also those of their partner, if they have one, unless the partner has a contrary interest (e.g. in a matrimonial dispute). It may include anyone else who is substantially maintaining the applicant (for instance, the parent(s) or guardian(s) of a child under 18). The gross income assessment includes all types of income, before any tax and National Insurance is deducted, unless it is specifically disregarded. Disregarded types of income include benefits intended for a specific type of purpose, such as Personal Independence Payments.[footnote 6]

45) The disposable income assessment assesses an applicant’s household income following deductions, which include tax and National Insurance, housing and childcare costs and allowances for dependents. The details of how disposable income is calculated vary between the different means tests, and are therefore summarised in the sections about each means test below. Subject to the result of the disposable income assessment, applicants for legal representation in civil and family matters, and at the Crown Court, may be required to make monthly income contributions towards the cost of their legal aid.

46) Applicants for civil legal aid and for criminal advice and assistance and advocacy assistance must additionally go through a capital assessment (outlined in paragraphs 56–61 and 80 below).

47) In the event of a change of financial circumstances, the LAA may reassess the means of legal aid recipients, potentially resulting in higher or lower (or no) contributions being payable, or the individual being found ineligible for legal aid.

Civil legal aid means test

48) The current civil legal aid means test was established in 2001, with some subsequent changes. The income thresholds were increased annually until 2009. To be eligible for legal aid in civil and family matters, an applicant must pass both the income and capital assessments.

49) Civil legal aid encompasses legal representation, which is primarily certificated work (that is, provided via a legal aid certificate issued by the LAA to the provider), and controlled work, for which means and merits decisions are delegated to providers. Controlled work includes legal help (for example, early advice and assistance before court proceedings), family mediation, and controlled legal representation (for certain immigration and mental health matters).

Income assessment

50) The gross income threshold for civil legal aid is £2,657 per month (£31,884 per year). If an applicant has more than four dependent children, this threshold is increased by £222 per month for each additional dependent child. Applicants with gross income above this threshold are not eligible for civil legal aid.

51) Applicants with gross income below this threshold then progress to a disposable income assessment. An applicant’s disposable income, for the purposes of civil legal aid eligibility, consists of their gross income with deductions for:

- tax and National Insurance

- child maintenance contributions

- criminal legal aid contributions

- rent/mortgage (where the applicant’s actual rent/mortgage payments are deducted, except for applicants with no partner or children for whom there is a £545 cap in place)

- childcare (actual costs arising from work or study outside the home).

52) Additional deductions are made for any other adult or child dependent living in the same household. These allowances, which are taken from those set by the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) for Income Support purposes, are currently set at £185.54 per month for a partner and £298.08 for any other dependent, including a child of any age. An additional work allowance of £45 per month, to recognise the additional costs of being in work, is applied for each adult in the household who is in work.

53) Applicants with disposable income not exceeding £733 per month following these deductions and allowances are eligible for civil legal aid (subject to the separate capital test, below). Those with disposable income of between £315 and £733 may be required to pay a monthly income contribution towards the costs of their legal representation; however, no income contributions are payable towards legal help or advice, or controlled legal representation.

54) A sliding scale, with three progressive bands, is used to calculate the amount of the monthly income contribution which must be paid for the lifetime of the case: applicants pay 35% of their disposable income between £311 and £465; 45% between £466 and £616; and 70% between £617 and £733. Non-payment of the monthly income contribution may result in withdrawal of the legal aid certificate. If the contributions paid exceed the cost of the case, any excess is refunded at the end of the case.

Civil legal aid income test: worked examples

Example 1

Applicant A has a partner and 3 children aged 3, 5 and 8, and gross household income of £3,500 per month.

Gross income assessment:

A has gross income above the threshold of £2,657 per month, and is therefore ineligible for legal aid, irrespective of their disposable income.

Example 2

Applicant B is a single parent with a child aged 15, and gross household income of £2,368 per month.

Gross income assessment:

B has gross income below the threshold, so progresses to the disposable income assessment.

Disposable income assessment:

after deduction of tax (£224), NI (£164), rent (£1,000) and dependent’s allowance (£298) per month, B has disposable income of £682 per month, and is therefore eligible for legal aid with a monthly income contribution of £166.90 for the lifetime of her case.

55) There are also certain payments that are disregarded from the income assessments. Disregarded types of income include payments for a specific purpose, e.g. Disability Living Allowance, and payments for compensation for harm, e.g. payments from the Criminal Injuries Compensation Authority. A table setting out the current income disregards for civil and criminal legal aid can be found in Annex A.

Capital assessment

56) The capital test assesses all of a person’s capital, including savings and non-monetary capital such as property, unless it is specifically disregarded. Disregarded types of capital include compensation payments from schemes including the Criminal Injuries Compensation Authority. A table setting out the capital disregards for civil and criminal legal aid can be found in Annex A.

57) As with income, the resources of the applicant’s partner and any other maintaining adult are usually taken into account unless there is a contrary interest.

58) Applicants with disposable capital below £3,000 are eligible for legal aid (assuming they have passed the income assessment) without any capital contribution. Applicants with disposable capital above £8,000 are ineligible for legal aid. Those with capital between £3,000 and £8,000 are required to pay a capital contribution of all their capital above £3,000, up to the estimated cost of their case. As individuals with over £8,000 capital are ineligible, this results in a maximum capital contribution payable of £5,000. For legal help, no contributions are required so only the upper threshold applies. For certain immigration matters, the capital limit is lower than for other civil cases, and is set at £3,000.[footnote 7]

59) The value of any property owned by an individual is included as their capital in the means test, but there are various disregards in place which apply to property. The amount of any mortgage or other debt secured on the property is deducted from the property’s value, and where a property is an individual’s main residence up to £100,000 of equity is also disregarded.

60) Where an applicant’s asset is the subject matter of the dispute – i.e. the subject of the case for which they want legal aid there is an additional disregard of up to £100,000.

61) The means test contains a capital disregard for pensioners, whereby those aged 60 or over on low incomes can have up to £100,000 of additional capital disregarded, and can therefore be eligible for legal aid whilst having more capital than those aged under 60. The amount of capital disregarded depends on the applicant’s disposable income:

| Monthly disposable income (excluding net income derived from capital) | Amount of additional capital disregarded |

|---|---|

| Recipient of a passporting benefit [^8] | £100,000 |

| £0-25 | £100,000 |

| £26-50 | £90,000 |

| £51-75 | £80,000 |

| £76-100 | £70,000 |

| £101-125 | £60,000 |

| £126-150 | £50,000 |

| £151-175 | £40,000 |

| £176-200 | £30,000 |

| £201-225 | £20,000 |

| £226-315 | £10,000 |

| Above £315 | £0 |

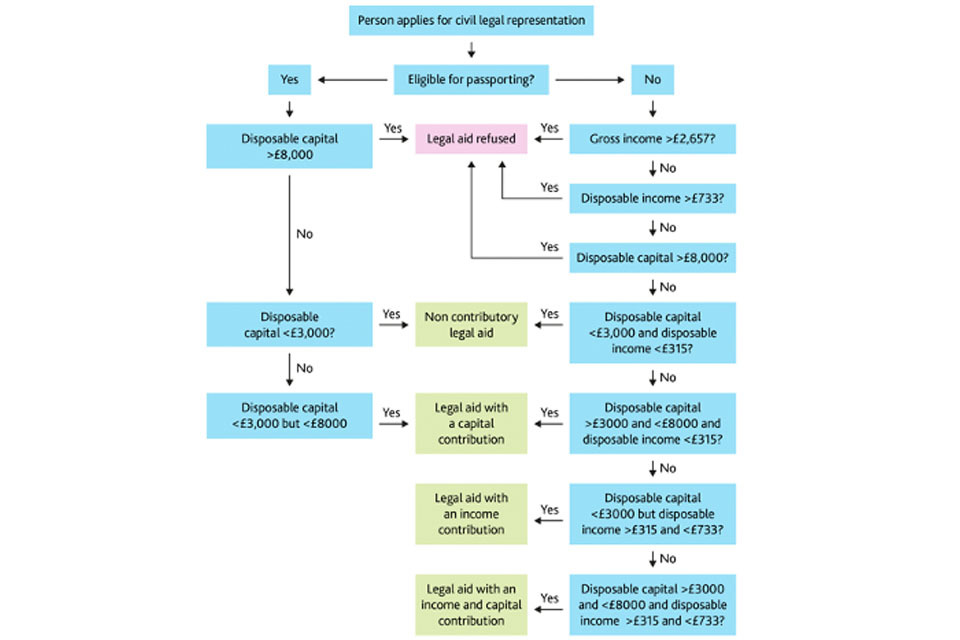

The current legal aid means test for civil representation

The current legal aid means test for civil representation

Legal aid at the Crown Court

62) The current means test was introduced at the Crown Court in 2010; it was modelled on the means test for the magistrates’ court, which was introduced in 2006 (see below), but with an additional contributory element and with no upper threshold (however, an upper disposable income threshold was introduced in 2014). The Crown Court means test has not been uprated since its introduction in 2010.

63) All applicants for criminal legally aided representation undergo an initial means test, which assesses their gross income. The Crown Court income test does not have an upper gross threshold but does have an upper disposable income threshold.

64) The Crown Court test also has a lower gross income threshold, currently £12,475 per year. Those with gross income below this level (adjusted for household composition) are entitled to non-contributory legal representation without going through a disposable income assessment.

65) Disposable income is measured by deducting the following from gross income:

- tax, National Insurance, housing, Council Tax, childcare and child maintenance (actual costs)

- a fixed cost of living allowance, currently £5,676 per year for a single person

- further deductions for partner/children (when relevant)

66) It is worth noting that this approach is distinct from that used for the civil legal aid means test, which does not deduct a cost of living allowance when assessing disposable income.

67) Unlike for the civil legal aid means test, the Crown Court means test does not use set allowances for partners and children, but instead uses the McClements equivalisation approach, for both the gross and disposable income assessment, to allow for the additional costs incurred by households of different sizes.[^9]

68) Applicants whose annual disposable income is £3,398 or less are entitled to non-contributory legal aid; those with annual disposable income between £3,399 and £37,500 are entitled to legal aid with a monthly income contribution. Legal aid recipients who consider that their assessed monthly income contribution is unaffordable may apply to the LAA for a hardship review; this review may result in a reduced income contribution.

69) Applicants with disposable incomes above £37,500 per year are ineligible for Crown Court legal aid, unless they successfully apply to the LAA for an eligibility review, which takes into account additional outgoings and the potential costs of private representation.[footnote 10] In the event that they have applied for legal aid, been refused on grounds of disposable income and are subsequently acquitted, they may claim back the private cost of their defence, capped at legal aid rates, via a Defendant’s Costs Order.

70) Those applicants who are liable to pay an income contribution make up to 6 payments at monthly intervals (these are refunded with 2% interest if the applicant is later acquitted). Each monthly income contribution is calculated at 1/12th of 90% of their annual disposable income. In practice, this means the minimum monthly income contribution is £255 (£3,399/12 x 90%). To incentivise payment, the applicant is exempt from the 6th monthly (or final) income payment if the first five payments are made on time.

71) At the end of the trial, if the applicant is acquitted, any income contributions they have paid are refunded. If they are convicted, they may be liable to pay any outstanding legal aid costs from any capital assets in excess of £30,000.A range of collection and enforcement tools may be used to secure the debt, including placing a charging order against a convicted individual’s property. If they have paid income contributions in excess of the cost of their defence, any excess is refunded.

Crown Court income test: worked examples

Example 1

Defendant C has a partner and two children aged 16 and 18. The household gross income is £33,000 per year.

Gross income assessment: C’s gross income is divided by 2.82 to take his family members into account. His adjusted gross income is £11,702. This is below the gross income threshold of £12,475, and C is therefore entitled to non-contributory legal aid without undergoing a further disposable income assessment.

Example 2

Defendant D has a partner and one child aged 2. The household gross income is £50,000 per year.

Gross income assessment:

D’s gross income is divided by 1.94 to take his family members into account. His adjusted gross income is £25,773. This is above the gross income threshold of £12,475, so D must undergo a disposable income assessment.

Disposable income assessment:

After deduction of tax (£5,484), National Insurance (£3,652), mortgage (£9,800), council tax (£1,818), childcare (£3,600) and Cost of Living Allowance (£5,676 x 1.94), D has a disposable income of £14,635 per year. This is above the lower disposable income threshold of £3,398 per year but below the higher disposable income threshold of £37,500 per year, so D is entitled to legal aid but must pay an income contribution.

Income contribution:

D must pay a monthly income contribution of £1,098 (90% of his disposable income) for up to 6 months.

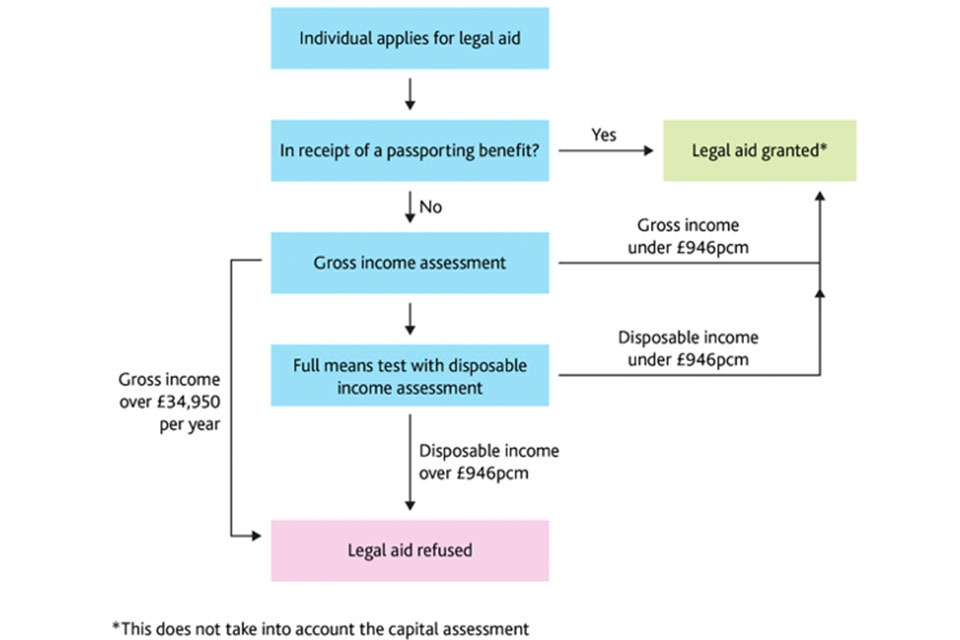

Legal aid at the magistrates’ court

72) Unlike the Crown Court means test, the magistrates’ court means test does not have a contributory element, and there is no capital assessment. It was last uprated in 2008.

73) As for the Crown Court means test, any applicant with gross income of £12,475 per year or below (when adjusted for household composition) is entitled to legal aid at the magistrates’ court without undergoing an additional disposable income assessment. The magistrates’ test also has an upper gross income threshold: applicants with gross incomes above £22,325 are not eligible for legal aid. For applicants with gross income of more than £12,475 but less than £22,325, eligibility is dependent on a further assessment of an applicant’s disposable income.

74) The disposable income assessment uses the same approach as that for legal representation at the Crown Court (see paragraphs 65–68 above). The disposable income allowance of £3,398 is derived from the estimated typical cost of a private defence when the magistrates’ court means test was introduced in 2006, and is meant to ensure that defendants who fail the means test are able to pay privately for their representation.

75) However, if an applicant has failed the means test but believes they cannot pay privately for their defence (due to extra unavoidable expenditure and/or legal costs they consider unaffordable), they can apply to the LAA for a hardship review, which may result in them being found eligible for legal aid.

Criminal advice and assistance/advocacy assistance

76) Legal aid in relation to criminal advice and assistance (A&A) and advocacy assistance (AA) is available for a range of criminal matters, spanning pre-charge to post-conviction proceedings. Many of these matters are non-means tested (for example, advice at a police station upon arrest; see Annex B for a full list), however some areas (such as Prison Law, and advice on appealing a sentence or conviction) are means tested (see Chapter 7, paragraph 459).

77) Where the means test applies, there are different thresholds depending on whether the matter falls under A&A or AA. Neither test assesses gross income. A&A sets a threshold of £99 disposable income per week and £1,000 of disposable capital. AA has a disposable income threshold of £209 per week and disposable capital threshold of £3,000.

78) Disposable income is defined in this context as gross income with deductions for tax, National Insurance, child maintenance payments, and other certain disregarded benefits and payments. There are also further deductions for applicants with partners/children (which, as for civil legal aid, are taken from those set by DWP for Income Support purposes, and are currently set at £42.70 per week for a partner and £68.60 per week for a dependent child). Therefore, unlike other areas of the means assessment, there are no deductions for criminal legal aid contributions, rent/mortgage, or childcare costs.

79) Disposable capital includes all of a person’s capital with deductions for the individual’s household furniture and effects, clothes, tools and implements of the individual’s trade, and any ‘back to work bonus’ payment. An individual’s property is included in this assessment, although the first £100,000 of equity and the first £100,000 of any mortgage on the property is disregarded. As with income, there are some additional capital allowances for applicants with dependants (£335 for a first dependent, £200 for a second dependent and £100 for each additional dependent).

Benefits passporting arrangements

80) Those in receipt of specific means-tested benefits are passported through the income assessment of the various legal aid means tests – i.e. they are deemed eligible for non-contributory legal aid without going through a full means assessment, though they may still have to undergo a capital assessment.[footnote 11] Since 2013, Universal Credit has been considered a passporting benefit on an interim basis. Applicants in receipt of passporting benefits are passported through the income means assessment for all types of civil and criminal legal aid and the capital means assessment for criminal legal aid at the Crown Court and for criminal advocacy assistance.[footnote 12]

Non-means tested legal aid

81) Non-means tested legal aid is available for some specific situations and legal proceedings. Current proceedings exempt from means testing include but are not restricted to: proceedings in relation to the use of accommodation to restrict liberty for a child; care and supervision order proceedings; legal help in relation to Terrorism Prevention and Investigation Measures; proceedings challenging a deprivation of liberty order made by a hospital or care facility; and cases heard by the Mental Health Tribunal.[footnote 13]

82) Non-means tested legal aid is also available for advice and assistance at a police station following arrest, duty solicitor support at the police station and magistrates’ court, advocacy assistance before magistrates’ court or the Crown Court, and for an individual appealing a conviction or sentence to the Court of Appeal or Supreme Court, as well as other types of proceedings.[footnote 14]

Chapter 2: Overarching proposals

83) As part of the Means Test Review, we have considered when alignment between the civil and criminal legal aid means tests is justified, and when we should take a different approach. In several areas, we are proposing to increase alignment, as we think there is a strong argument for developing a common approach across some or all of the different means tests.

84) This chapter therefore lays out policy proposals that we are proposing would apply across the various means tests. We are not proposing total alignment in all of these areas, as we consider that in some cases there is a strong argument for different approaches. We have provided more detail about the rationale for our approach under the areas in question.

85) These proposals fall under the following areas:

- Eligibility for legal aid

- Equivalisation

- Assessment of disposable income

- Income disregards

- Benefits passporting

- Income contributions

Eligibility for legal aid

86) As laid out in the Introduction (paragraph 23), one of the objectives of the Legal Aid Reform programme launched in 2011 was that legal aid should be targeted at those who need it most. In line with our historic approach to eligibility for legal aid, we have interpreted this objective as follows.

87) First, the scope of the legal aid scheme should be targeted at those who need it most, for the most serious cases in which legal advice and representation is justified. As well as a defined list of services within the scope of the civil and criminal legal aid schemes, there is also the ability for an individual to apply for ECF, which ensures that legal aid is available where failure to provide legal services would be a breach, or risk of a breach, of an individual’s human rights or retained enforceable EU law rights, or where there is a wider public interest. The Means Test Review and this consultation do not consider the scope of legal aid, or the merits test (for civil legal aid) and interests of justice test (for criminal legal aid), which are laid out in Chapter 1 (paragraph 39).

88) Secondly, for most types of legal aid, legal aid should be targeted at those with fewer financial resources available to them, and who are therefore unlikely to be able to pay privately for legal advice or representation.

89) However, there are some types of legal aid where we do not consider that applicants should be excluded solely on grounds of their means. These include some areas of civil and criminal legal aid (such as legal representation in ‘Special Children Act’ proceedings[footnote 15] or in front of the Mental Health Tribunal, and advice at a police station following arrest) for which there is no means test at all. There are also some areas, such as applications for protective injunctions, where legal aid is available to all applicants (assuming they pass any necessary merits or interests of justice test, and the waiver of eligibility limits is applied), but, depending on an applicant’s income and/or capital, a contribution may be payable.

90) We consider that applicants with median or above median incomes should not be eligible for most means-tested areas of legal aid, as we do not consider them most in need. However, this approach does not extend to defendants at the Crown Court. Our detailed proposals for legal aid eligibility can be found in Chapters 3 (civil income thresholds), 4 (civil capital thresholds), 6 (Crown Court) and 7 (magistrates’ court and criminal advice and assistance/advocacy assistance).

Equivalisation

91) Equivalisation is the process by which income is adjusted to take account of the needs of households of different sizes. This helps ensure fairness in the way legal aid resources are allocated, as household composition can have a direct bearing on living costs, and hence whether the individual can afford to pay for or contribute towards their legal costs.

92) At present, the means tests take differing approaches to equivalisation. The civil means test sets a single gross income threshold (with additional allowances for families with 5 or more dependent children), but deducts fixed allowances to cover a partner and any other adult or child dependent living in the same household. These allowances are derived from those set by DWP for Income Support purposes. In contrast, the means tests for criminal legal representation at the Crown Court and magistrates’ court use the McClements approach to equivalisation for both gross and disposable income assessment purposes. The McClements approach, originally developed in 1977, uses different weighting factors depending on the specific age of individual children in a household.

93) We propose to standardise our approach to equivalisation across the civil and criminal legal aid schemes, as we consider it is reasonable to use one single approach to take account of the needs of different household compositions. We propose to use the OECD Modified scale, which over recent years has become the most widely adopted equivalisation scale internationally, and is used by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) as well as DWP. It provides both a Before Housing Costs (BHC) and After Housing Costs (AHC) measure – this is important, as housing costs are a significant driver of the difference in financial needs for larger families. We propose to use the BHC metric when assessing gross income and the AHC metric when assessing disposable income, in line with the means test approach, by which housing costs are deducted from gross income and therefore not taken into account in the disposable income assessment (see paragraphs 99–104 below).

94) For gross income assessment purposes, we therefore propose to adjust the gross income threshold upwards depending on the size of the household. Using the BHC equivalisation metric, for each additional adult or child aged 14 or over, the threshold would increase by 50% of the gross threshold for a single adult; for each child under the age of 14, the corresponding figure is 30%.

95) For disposable income assessment purposes, we propose to set fixed allowances for additional adults and children, based on an AHC equivalisation of the relevant Cost of Living Allowance. The AHC equivalisation metric is 72% of the Cost of Living Allowance for each additional adult or child aged 14+; and 34% of the Cost of Living Allowance for each child under 14.

96) We will lay out the value of these specific allowances, with worked examples, in Chapters 3, 6 and 7, which outline our proposed income thresholds (including the Cost of Living Allowance) for each means test.

Question 1

Do you agree with our proposal to take household composition into account in the means test by using the OECD Modified approach to equivalisation? Please state yes/no/maybe and provide reasons.

Answer this question online

Assessment of disposable income

97) We consider that our approach towards assessing disposable income should be the same across civil and criminal legal aid, unless there is a specific reason to differentiate. We are proposing some changes to the assessment of disposable income, which we have outlined below.

Housing, council tax and childcare costs

98) At present, both the civil and criminal means tests deduct the amount applicants pay towards their rent or mortgage costs as part of the disposable income assessment. An exception is applicants for civil legal aid who have no partner or children, for whom there is a £545 monthly cap in place.

99) The Crown Court and magistrates’ court means tests also deduct actual Council Tax as part of the disposable income assessment; however, the civil legal aid means test does not. Instead, applicants for civil legal aid are expected to pay Council Tax from their disposable income.

100) We consider that it is fair to deduct actual housing costs. This is because the significant variation in housing costs (including Council Tax), depending on household composition and between different regions of England and Wales, and the fact that housing costs change frequently, mean that to set any type of fixed allowance or cap on housing costs would be complex and difficult. Deducting actual housing costs enables a more accurate assessment of an applicant’s disposable income.

101) We therefore propose to continue to deduct actual rent and mortgage payments for the civil and criminal means assessments, and to continue to deduct actual Council Tax as part of the Crown Court and magistrates’ means tests.

102) We propose to continue to deduct applicants’ actual childcare costs, as at present, there is a wide variation between childcare costs depending on type of provision and location.

103) For the civil legal aid means assessment we propose to remove the £545 cap on housing costs for applicants with no partner or children, and to deduct actual council tax paid as part of the disposable income assessment (as for the Crown Court and magistrates’ court means tests). This will align our approach for civil means assessment with that for means assessment at the Crown Court and magistrates’ court. We have asked a consultation question on this proposal in Chapter 3, paragraph 169.

Question 2

Do you agree that we should continue to deduct actual rent and mortgage payments and childcare costs for the civil and criminal means assessments? Please state yes/no/maybe and provide reasons.

Answer this question online

Pension contributions

104) We also propose to deduct pension contributions as part of the disposable income assessment for all means-tested legal aid. Since 2001, when the current civil legal aid means test was developed, the government has instituted automatic enrolment, by which employers must automatically enrol qualifying jobholders (unless they specifically opt out) into a pension scheme. We therefore propose that, to ensure alignment with wider government policy, jobholder pension contributions up to 5% of earnings are deducted as part of the disposable income assessment. We have chosen 5% as this is what a jobholder would have to contribute if their employer makes the lowest contribution as required by law, which is 3%.

Question 3

Do you agree with our proposal to deduct jobholder pension contributions as part of the disposable income assessments for civil and criminal legal aid? Please state yes/no/maybe and provide reasons.

Question 4

Do you agree with our proposal to limit the amount of jobholder pension contributions we deduct as part of the civil and criminal means assessments to 5% of earnings? Please state yes/no and provide reasons.

Answer these questions online

Prisoner Earnings Act levy

105) We propose to deduct any Prisoners’ Earnings Act levy as part of the disposable income assessment, for all types of legal aid. Prisoners who work (either inside or outside of prison) have a maximum 40% levy deducted from net income earned over £20 per week. The money is never received by the prisoner and therefore is not available to be used to pay for legal services; however, it is currently considered as disposable income within the means assessment. This proposal will enable a more accurate assessment of disposable income.

Question 5

Do you agree with our proposal to deduct any Prisoners’ Earnings Act levy as part of the disposable income assessment for legal aid? Please state yes/no/maybe and provide reasons.

Answer this question online

Work allowance

106) The civil legal aid means test includes an additional allowance of £45 per month for any members of the household who are in work, to take account of work travel costs and any other work-related costs. We propose to keep this allowance, as it is aligned with wider government policy to encourage work and ensure that working-age adults are better off in work than out of it.

107) As the current allowance has not been uprated since 2001, we propose to raise it to £66 per month, in line with a 2019 Lloyds/YouGov report on average monthly work travel costs[footnote 16] (as ONS do not capture this element of spending, and we are not aware of any other recent quantitative research on this topic).

108) At present, the means tests for legal representation at the Crown Court and magistrates’ court do not include a work allowance. However, we think that there is a strong rationale for such an allowance, to take account of work-related costs incurred by defendants who are in employment or self-employment. We therefore propose to introduce a work allowance of £66 per month into the Crown Court and magistrates’ court means tests.

109) We have included consultation questions on this issue in Chapters 3 (paragraph 171), 6 (paragraph 357) and 7 (paragraph 436).

Treatment of debt

110) At present, the initial means assessments for civil and criminal legal aid do not take into account any debt repayments or liabilities (except mortgage or rent arrears). However, defendants found ineligible for legal aid at the Crown Court or magistrates’ court, or required to pay income contributions in Crown Court proceedings which they consider unaffordable, can apply for a review, which considers financial commitments not taken into account by the disposable income test, including debt payments.

111) In recent years, the government’s approach to debt has developed, following engagement with a wide range of stakeholders. In October 2018, HM Treasury published a consultation on a “Breathing Space scheme”, intended to give people in problem debt the opportunity to take control of their finances and place them on a sustainable footing.

112) On 4 May 2021, the Debt Respite Scheme (Breathing Space Moratorium and Mental Health Crisis Moratorium) (England and Wales) Regulations 2020 came into effect. These provisions give those in problem debt or facing a mental health crisis the right to legal protections from their creditors, who must pause enforcement activity of a “qualifying debt” for a standard period.

113) HMT is also developing a Statutory Debt Repayment Plan (SRDP), which plan would enable someone in problem debt to enter a statutory agreement to repay their debts to a manageable timetable. The government plans to consult on draft SDRP regulations and intends, following consultation, to lay those regulations by the end of 2022. When these regulations have been finalised, we will consider our approach to SDRP payments in the context of the legal aid means test.

Our proposals

114) We consider that the legal aid means test should broadly align with the cross-government approach to people facing problem debt. We are therefore proposing that the means assessment for civil and criminal legal aid deducts agreed repayments of priority debt as part of the disposable income assessment. By agreed, we mean that the applicant should be able to evidence regular repayments, and/or demonstrate a repayment agreement with the creditor.

115) Priority debts are defined by the government-funded Money Advice Service as “debts that carry the most serious consequences if you don’t pay them”. Non-payment of these debts may result in a criminal conviction (potentially resulting in a prison sentence), a fine, disconnection of utilities, repossession or eviction.

116) These include:

- court fines and orders

- Council Tax arrears

- TV Licence arrears

- child maintenance arrears

- gas and electricity arrears

- Income Tax, National Insurance and VAT arrears

- mortgage, rent and any loans secured against your home

- hire purchase agreements, if what is bought is essential – such as a vehicle that is required for work purposes

- missed payments owed to DWP or HMRC

- payments in relation to Individual Voluntary Arrangements.[footnote 17]

117) We consider that MoJ should not be asking applicants for legal aid to choose between paying legal aid contributions and paying off priority debt; and that applicants for legal aid should not be found ineligible solely due to being pushed over the upper disposable income threshold by income that is being used for repayment of priority debt.

118) We additionally propose that student loan repayments taken directly from salary (or, for self-employed people, deducted as part of their tax return) should be deducted as part of the disposable income assessment, as it is government policy that students should contribute to the cost of their studies, and we consider that these repayments should not be considered as disposable income.[footnote 18]

Question 6

Do you agree with the proposal to deduct agreed repayments of priority debt and student loan repayments taken directly from salary or deducted as part of the applicant’s tax return as part of the disposable income assessment for civil and criminal legal aid? Please state yes/no/maybe and provide reasons.

Answer this question online

Cost of Living Allowance

119) At present, the means test for criminal representation draws on a Cost of Living Allowance, which was originally established for the magistrates’ court means test in 2005 and then extended to the Crown Court in 2010.

120) This allowance uses median household expenditure (as captured by the annual ONS living costs survey) on a range of items, including all spending considered essential but excluding alcohol and tobacco, restaurants and hotels, and culture and recreation. This enables us to assess how much income individuals need to cover their essential living costs before we consider they are able to contribute anything towards their legal costs.

121) We propose to uprate the Cost of Living Allowance for legal aid at the Crown Court and magistrates’ court in line with this existing approach, so that it betters reflect ONS data on living costs. Our detailed proposals for this uprating are covered in Chapter 6, paragraphs 358–360.

122) We also propose to introduce a Cost of Living Allowance for the civil legal aid means test. This will be slightly different from the Cost of Living Allowance for the Crown Court and magistrates’ court. Our rationale and detailed proposals for this Cost of Living Allowance are covered in Chapter 3, paragraphs 172–178.

Income disregards

123) As outlined in Chapter 1 (paragraph 45), the means test disregards some types of income when assessing an applicant’s gross or disposable income, as we consider that these payments should not be counted as money that could be used to pay for legal services. Some income disregards are the same across civil and criminal legal aid, for instance, benefits (like Disability Living Allowance) which are designed to support the additional cost of disability. However, there are some differences; for instance, reasonable living expenses provided for as an exception to a restraint order are only disregarded from the criminal legal aid assessment.[footnote 19]

124) In evaluating which income payment should be disregarded, we consider that payments made to cover a specific need, for example, to cover disability costs or compensation for harm, should not be taken into account for the income assessment. This is because these payments are intended for a specific purpose, so we would not expect the individual to use this money to pay for legal services.

125) We also consider that we should not disregard payments intended as income replacements. We consider an income replacement to be a payment or (more often) a series of payments made to support general living costs. It will often be made to reflect the fact that an individual is unable or unlikely to be able to work, either full-time or at all. We consider the following are examples of income replacements: state pension, Jobseeker’s Allowance, and Employment and Support Allowance.

126) We consider that income replacement payments are analogous to earnings, and therefore can potentially be used to pay for legal services, as earnings would normally be taken into account as part of the income assessment. The exception would be where the payment is a passporting benefit, where no income assessment is required.

127) Furthermore, as part of the current income assessment, payments are disregarded on either a discretionary or mandatory basis. Where the disregard is mandatory, the Director of Legal Aid Casework (DLAC) must disregard the payment. On the other hand, where the disregard is discretionary, the DLAC has the discretion to disregard the payment, taking into account any relevant guidance, for example the Lord Chancellor’s guidance, but is not obliged to do so. The majority of payments currently disregarded from the income assessment are disregarded on a mandatory basis (see table in Annex A). However, there are some payments where the DLAC has an option to exercise their discretion, for example Criminal Injuries Compensation Authority payments.

128) We propose that the following additional payments should be disregarded from the means assessment for all types of legal aid:

Modern Slavery Victim Care Contract (MSVCC) financial support payments

129) The National Referral Mechanism (NRM) is the process by which the UK identifies and supports potential victims of modern slavery by connecting them with appropriate support, which may be delivered through the specialist Modern Slavery Victim Care Contract (MSVCC), local authorities and asylum services.

130) Potential victims and victims of modern slavery who have entered the NRM, received a positive Reasonable Grounds decision and consented to support from the MSVCC, will be paid financial support on a weekly basis. This payment will continue while they remain in MSVCC support – until they have received a Conclusive Grounds decision. Where an individual has received a positive Conclusive Grounds decision, they will continue to receive financial support for as long as they are assessed to have a recovery need for this assistance through a Recovery Needs Assessment. Financial support is intended to meet the potential victim’s essential living needs during this period and assist with their social, psychological and physical recovery.

131) Therefore, we propose disregarding these payments on a mandatory basis when assessing an applicant’s income for both the civil and criminal means tests, as these payments are intended for a specific purpose and we would not expect applicants for legal aid to use them to pay for legal services.

Question

Question 7: do you agree with our proposals to disregard Modern Slavery Victim Care Contract (MSVCC) financial support payments from the income assessment? Please state yes/no/maybe and provide reasons.

Answer this question online

Victims of Overseas Terrorism Compensation Scheme (VOTCS)

132) This government-funded scheme, which has existed since 2012, is designed to compensate victims who sustain injuries from terrorist incidents overseas. The payments under this scheme can either be paid as a lump sum payment or multiple payments. This means that it can be considered as part of the capital assessment and also the income assessment. Proposals to disregard these payments from the capital assessment can be found in Chapter 4, paragraphs 266–268.

133) We propose to disregard these payments on a discretionary basis when assessing an applicant’s income for both the civil and criminal means tests. This is because the scheme provides a mixture of payments for compensation for harm as well as payments for loss of earnings.

Question 8

Do you agree with our proposals to disregard Victims of Overseas Terrorism Compensation Scheme (VOTCS) payments from the income assessment? Please state yes/no/maybe and provide reasons.

Answer this question online

134) We also propose that the following payments that are currently disregarded should no longer be disregarded:

Back to Work Bonus

135) Any Back to Work Bonus made under section 26 of the Jobseekers Act 1995 is currently disregarded from the income and capital assessment for civil and criminal legal aid. This scheme was created to encourage unemployed people or those who had been unable to work due to illness or disability to take part-time work and then move into full-time work, with a maximum amount of £1,000 being paid. However, this scheme was abolished on 25 October 2004 and no new payments have been made since. It is highly unlikely that an individual would still have this payment and we do not consider that these payments fit within our rationale as this is not a payment to compensate for harm or for a specific purpose. We therefore propose that these payments are no longer disregarded from the income and capital assessments.

Question 9

Do you agree with our proposal to remove Back to Work Bonus payments from the civil and criminal income disregards regulations? Please state yes/no/maybe and provide reasons.

Answer this question online

Housing benefit

136) Court and magistrates’ court means tests. Actual housing costs (netted off against housing benefit received) are then deducted as part of the disposable income assessment. This disregard was introduced into the civil legal aid means test in 2001, alongside the creation of a threshold limiting eligibility for civil legal aid to applicants with a gross household income below £24,000, whatever the size of household. Previously, the means test had only assessed disposable income.

137) We consider there is no need for housing benefit to be disregarded from gross income in the new means test, as our proposed approach to gross income assessment (see above, paragraphs 92–96), has been designed to take into account the different needs of households of different sizes and compositions, including housing costs.

138) We therefore consider it is fairer to consider housing benefit as income, and to deduct the applicant’s actual housing costs as part of the disposable income assessment. This means that we will be treating recipients of housing benefit in the same way as we treat applicants who do not receive housing benefit.

Question 10

Do you agree with our proposal to remove housing benefit payments from the civil and criminal income disregards regulations? Please state yes/no/maybe and provide reasons.

Answer this question online

Benefits passporting

139) Passporting is the process via which applicants who are in receipt of certain means-tested benefits are deemed eligible for non-contributory legal aid without going through a full means assessment. The following benefits are used as passporting benefits: Income Support (IS); income-based Jobseeker’s Allowance (JSA); Universal Credit (UC); Guarantee Credit element of Pension Credit (GC); income-related Employment and Support Allowance (ESA). Currently, applicants in receipt of these benefits are passported through the income means assessment for civil and criminal legal aid, and the capital means assessment for legal aid at the Crown Court which determines whether individuals in receipt of legal aid are required to pay a capital contribution following conviction.

140) Passporting aims to streamline the means assessment process for applicants who have had their means assessed by the Department for Work and Pensions and who are therefore very likely to be eligible for non-contributory legal aid if they underwent a full means assessment. In the interests of having a fair, sustainable and efficient means test, we have considered whether the current policy ensures that passported individuals are likely to have income and capital below the proposed thresholds for non-contributory legal aid. When developing our proposals, we have sought to ensure that applicants will only be passported where it is very likely they would be eligible for non-contributory legal aid.

141) DWP are currently projecting that all recipients of income-based Jobseeker’s Allowance, income-related Employment Support Allowance and Income Support will be transferred to Universal Credit by 2024. We propose to continue passporting any remaining recipients of these benefits through the income element of the civil and criminal means tests. Changing our policy on passporting recipients of these benefits for potentially a very short period until these benefits are replaced by UC would create an unnecessary administrative burden. In any case, there is a long history of passporting these benefits, and individuals in receipt of them have to be on a low income and are unable to work over 16 hours per week, so would be unlikely to fail our proposed new means tests.

Question 11

Do you agree that we should continue to passport any remaining recipients of income-based Jobseeker’s Allowance, income-related Employment Support Allowance and Income Support through the income element of the civil and criminal means tests? Please state yes/no/maybe and provide reasons.

Answer this question online

142) Individuals in receipt of the Guarantee Credit element of Pension Credit are currently passported through the income assessment for civil and criminal legal aid. Our analysis suggests that most individuals in receipt of legacy passporting benefits, including Guarantee Credit, would qualify for non-contributory legal aid under the proposed means test (97% for legal help cases and 80% for civil representation). In addition, continuing to passport these individuals will make the means test more efficient, reducing administrative costs for the LAA and providers. We therefore propose to continue passporting recipients of Guarantee Credit.

Question 12

Do you agree that we should continue to passport recipients of the Guarantee element of Pension Credit through the income element of the civil and criminal means tests? Please state yes/no/maybe and provide reasons.

Answer this question online

143) Our proposals for passporting Universal Credit recipients do not apply to the different means tests in the same way. They are therefore included in chapters 3 (civil legal aid income passporting), 4 (civil legal aid capital passporting), 6 (Crown Court legal aid) and 7 (magistrates’ court and criminal advice and assistance/advocacy assistance).

Income contributions

144) Our proposals in relation to income contributions have been driven by our desire to ensure fairness for the individual. As currently configured, the calculation of the income contribution for Crown Court legal aid is structured such that a defendant whose annual disposable income is £3,398 (equivalent to £283 per month) pays no income contribution, but at £3,399 pays a monthly contribution based on 90% of their total annual disposable income, rather than based on that amount above a specific threshold.

145) This contrasts with the approach taken for civil legal aid where the application of a tiered approach to disposable income above £315 per month (set at 35%/45%/70% of their total annual disposable income – see Chapter 1, paragraph 54) allows for a more progressive calculation of the income contribution.

146) At the same time, a single contribution band set at 90% provides very little financial cushion for the individual. Whilst the new proposed Cost of Living Allowance (COLA) means that we would not be asking individuals to forsake essential expenditure in order to pay their income contribution, we recognise that some additional flexibility may be helpful (for example, to cover emergency household repairs).

147) Therefore, we propose to align our approach for both the Crown Court and civil legal aid by adopting a progressive and unified tiered approach to calculate the monthly income contribution.

148) We are proposing to draw on the existing tiered system for civil income contributions, but updating the bands to 40%, 60% and 80%. We think that this slightly increased level of contributions will be affordable for legal aid applicants in the light of our proposals in relation to disposable income assessment and the Cost of Living Allowance, aligning with our position that legal aid recipients who can afford to contribute towards the cost of their legal aid should do so.

149) This calculation will apply only to disposable income above the proposed new thresholds, so eliminating any risk of a “cliff edge”. We have set the minimum contribution at 40% as this creates a financial buffer zone for those on lower disposable incomes. As the bands apply progressively, this approach allows us to collect proportionately more from those with higher disposable incomes.

150) In reviewing the existing arrangements, we have also focused on the payment period for income contributions. At the Crown Court, since 2010, the payment period has been pegged at a maximum 6 months to reflect what was previously the average length of time that a trial took to complete from the date of charge. However, as a significant proportion of cases may take much longer to conclude, we have explored options to extend the maximum payment period.

151) For civil legal aid, our analysis of the payment period starts from a different angle as monthly income contributions currently continue for the lifetime of the case. However, we are conscious that some applicants, including those with a meritorious case, may decline an offer of contributory legal aid because of uncertainty about the total amount they may have to pay in income contributions.

152) We believe there is scope to achieve a greater degree of alignment to our approach to the payment period: for civil legal aid, we propose setting a maximum payment period of 24 months, whilst at the Crown Court extending the payment period to a maximum 18 months. We set out our thinking in more detail, with consultation questions, in Chapters 3 and 6.

Chapter 3: Civil income thresholds, passporting and contributions

153) The current civil means test came into force in December 2001. Its aim (as set out in a consultation document of July 2000[footnote 20] was “to ensure that the available resources are spent on people who most need help, and that people who can afford to contribute towards the cost do so”.

154) The July 2000 consultation document stated, “In most respects, the financial conditions that have been set initially for the new scheme are the same as those that previously applied to legal aid.” The changes proposed were summarised as follows:

- to set the same financial eligibility limits for all levels of [civil and family] service

- to simplify the rules for means testing and ensure that, so far as possible, the same rules apply to all levels of service

- to make a number of other changes to make the financial conditions more consistent and fairer.

155) Between 2002 and 2009, the gross and disposable income thresholds for civil legal aid were updated most years in line with inflation. However, the thresholds have not been uprated since 2009, and a number of legal aid practitioners have raised concerns that the level at which the thresholds are now set means that some applicants for civil legal aid are finding themselves ineligible on means grounds without being able to afford any private legal fees.

156) As outlined in Chapter 2, we have developed a proposed new approach to civil income thresholds. We consider that it is important that, when setting the new income thresholds, our approach allows for spending on essential living costs. At the same time, we have aimed to balance the needs of those seeking to access legal aid with affordability for the taxpayer, while securing access to justice. Alongside this, we have developed an updated approach to income passporting and contributions for civil legal aid.