Summary of responses

Updated 28 February 2023

Executive summary

Defra’s consultation on proposals to designate five candidate Highly Protected Marine Areas (HPMAs) ran from 6 July 2022 to 28 September 2022. This document describes the evidence and views we received via our Citizen Space survey, via emails, in person and via online meetings held during the consultation period.

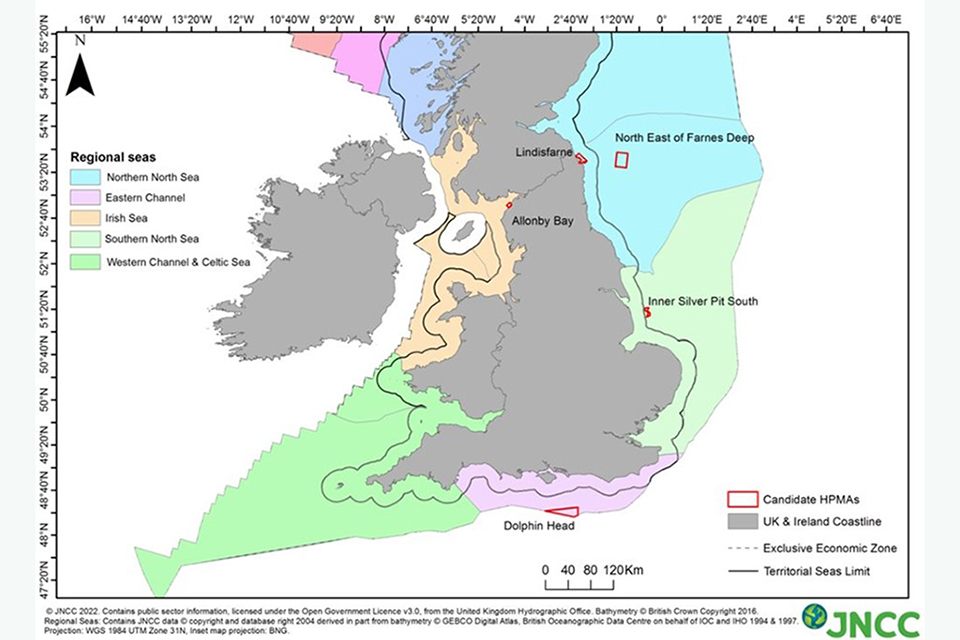

The candidates were two inshore sites, Allonby Bay (located in the Irish Sea) and Lindisfarne (located in the Northern North Sea), and three offshore sites, North East of Farnes Deep (also located in the Northern North Sea), Inner Silver Pit South (located in the Southern North Sea) and Dolphin Head (located in the Eastern Channel).

Defra received 915 responses to the consultation. We heard a wide variety of views. Overall, 56% supported the designation of pilot HPMAs in English waters and 36% were opposed. Fifty-three per cent of supportive responses agreed with the need for HPMAs to address the climate crisis, biodiversity decline and declining environmental status. The most common reason for opposing HPMAs was the direct (30%) and indirect (22%) impact on livelihoods.

Responses varied by site with Lindisfarne candidate HPMA receiving the highest number of responses with 372 survey responses and 29 emails. Only 15% of the survey respondents supported the proposal. Conversely for the Dolphin Head candidate HPMA, 97% of 177 survey respondents supported the site.

Following the consultation Defra analysed the quantitative and qualitative information we received, with the support of Cefas, the Marine Management Organisation, Natural England and JNCC. We presented this evidence to Ministers.

After reviewing the evidence, the Secretary of State intends to designate the candidate HPMAs of Allonby Bay, North East of Farnes Deep and Dolphin Head.

Designation orders must be laid before 6 July 2023 and Defra will now progress the designation process for the three pilot HPMAs.

In addition, Defra will explore further candidate sites.

Introduction

To achieve the government’s ambition in our 25 Year Environment Plan, further action is needed to improve the health of our seas, enable their recovery and protect them into the future. Highly Protected Marine Areas (HPMAs) are one action we can take to support biodiversity recovery. By setting aside areas of the sea with high levels of protection, HPMAs will allow nature to fully recover, helping the ecosystem to thrive and be more climate resilient.

We have defined HPMAs in the government response to the Benyon Review as “areas of the sea that allow the protection and recovery of marine ecosystems by prohibiting extractive, destructive and depositional uses, and allowing only non-damaging levels of other activities to the extent permitted by international law”.

Following the 2019 Independent Review and government response, Defra worked with its Arm’s-Length Bodies (ALBs) to identify candidate sites based on ecological, social and economic criteria. Defra consulted on a shortlist of five candidate sites (Figure 1), covering 0.53% of English waters.

These sites were two inshore sites and three offshore sites:

Inshore sites

- Allonby Bay (located in the Irish Sea)

- Lindisfarne (located in the Northern North Sea)

Offshore sites

- North East of Farnes Deep (located in the Northern North Sea)

- Inner Silver Pit South (located in the Southern North Sea)

- Dolphin Head (located in the Eastern Channel)

The 12-week consultation was launched on 6 July 2022 seeking views on the proposals to designate these as pilot HPMAs, and to gather additional evidence on their social and economic impacts. The consultation closed on 28 September 2022.

The consultation survey hosted on Citizen Space consisted of 24 questions covering background information from respondents and their general views on HPMAs and up to 36 questions concerning each HPMA site.

Stakeholder engagement during the consultation period

During the consultation period, Defra held a series of online (23) and in-person (11) meetings alongside the online consultation. Following the consultation launch, a series of sectoral meetings provided more information on the HPMA process, consultation and candidate sites and gathered initial views. Defra then held online workshops for each of the candidate sites. Defra ran site-specific in-person meetings and drop-ins at locations across England to better gather local evidence and data on the potential social and economic impacts of designation. Following the site visits, Defra held an additional series of online focus group sessions to ensure that people who couldn’t attend the in-person meetings had an opportunity to share their views. Additionally, reflecting Trade and Cooperation Agreement requirements, Defra ran two online meetings for EU officials and two for EU stakeholders. Non-UK stakeholders were also invited to the post-visit online meetings.

Map of the UK showing the locations of the 5 candidate HPMAs.

Overview

How we analysed responses

The consultation included both closed-ended and open-ended questions alongside additionally submitted evidence and views received via email. We read and analysed all individual responses except:

- we quantitatively analysed closed-ended responses received through Citizen Space, using automated methods. We describe a complete summary of these data in Annex 2

- we identified identical responses in many of the campaign responses received either through Citizen Space or email, based on consistency of their content – however we read all personal additions individually

- we summarised individual poll responses submitted as additional evidence - we summarised these responses and included the main findings in the appropriate section of the summary

Due to the quantity and specificity of close-ended questions in the Citizen Space survey, we treated open text email responses separately from Citizen Space responses throughout this summary.

We counted all responses received within the consultation deadline in the response rates and we included their views in the analysis. One percent of responses were received late and we did not analyse these. If a response was received late, the respondent was informed that it would not be included in the main analysis. We have retained these responses and will consider these in policy development. We have also included a brief summary of late responses.

Campaign responses, excluding polls, formed 5.36% of the total responses. We analysed these separately from other individual and organisational responses and summarised them according to the views expressed regarding HPMAs.

In the case of both email and Citizen Space, some respondents including those representing industry organisations had coordinated their responses: we treated these as individual or organisation responses rather than as campaigns.

We have detailed views and responses from in-person and online events, which Defra hosted in summer 2022, alongside written submissions to the consultation throughout this summary. We have included further detail from these meetings in Annex 3.

In this summary, we summarise information from analysed and read consultation responses and meetings, except for commercially sensitive information. We have also removed names of organisations from the content of responses in order not to identify respondents directly, however we have included a full list of all organisations responding to the consultation in Annex 1.

Number of responses

In total, we received 915 responses to the consultation. These comprised:

- 837 responses through Citizen Space

- 78 responses through email

- 0 responses though post

Of the 837 overall responses through Citizen Space, 50 were part of a known campaign and were removed from any further analysis. There were 787 remaining responses.

Both email and online Citizen Space respondents indicated the organisation they were responding on behalf of (Table 1).

Table 1. Number or respondents to consultation by mode of response and type of organisation

| Respondent category | Number of Citizen Space responses (of which campaign responses) | Number of email responses (of which late responses) |

|---|---|---|

| Individual | 775 (49) | 14 (2) |

| Fishing industry (UK) | 12 | 12 |

| Fishing industry (non-UK) | 3 | 6 |

| Other industry | 5 | 12 |

| Local government | 4 | 5 |

| Government (UK) | 0 | 0 |

| Government (non-UK) | 0 | 4 (3) |

| Government agency orALB | 0 | 4 |

| Recreation | 7 | 4 |

| Tourism | 1 | 3 |

| Community | 1 | 3 |

| Environmental | 16 (1) | 6 (3) |

| Academia or Research | 2 | 2 |

| Other | 5 | 3 (2) |

| TOTAL | 837 (50) | 78 (9) |

Summary of late responses

Nine responses were submitted late via email. These responses were from two individuals, an organisation representing marine users, three non-UK government bodies, one conservation and advisory group and two environmental organisations. Three emails supported and six opposed the proposals.

Three emails were interested in general HPMA issues across all candidate sites. Allonby Bay was the focus of two responses, as was Lindisfarne. Inner Silver Pit South was the subject of three emails, while two emails referred to North East of Farnes Deep and four emails referred to Dolphin Head.

Consultation responses: campaigns

The only clear campaign appears to have been on behalf of the environmental organisation Greenpeace and comprised 50 respondents. Respondents were a mix between self-professed representatives or supporters of Greenpeace (2%) and those who state they are responding as individuals (98%) and in some cases, identifying as members of an environmental organisation (74%), including Greenpeace specifically (70%).

The Greenpeace campaign rarely included responses to questions on any of the sites, with most respondents responding to the general questions, and particularly to their opinion on HPMAs in general. These comments expressed the following views:

- their campaign respondents all strongly support the implementation of pilot HPMAs at all five sites

- the campaign is concerned that five sites is not enough to achieve the government’s promise of protecting 30% of UK waters by 2030

- they believe that elements of industrial fishing should be banned in existing MPAs, which would provide for local fishers, and sustain marine populations

Consultation responses

Who responded?

Respondents who completed the online survey on Citizen Space provided demographic information (Questions 1-9 of the online survey) and this was analysed for all non-campaign respondents answering as individuals (726 respondents).

Male respondents made up 51%, females 44%, while 5% did not answer or preferred not to say. The majority of respondents (77%) were not members of an any environmental organisation (for example, charities, non-governmental organisations or community action groups), while 13% were members of an environmental organisation not specific to marine issues and 5% were members of marine focused organisations.

Of the 505 respondents consenting to provide income data, the most common annual household income was above £50,000 (35%) with most respondents earning above £30,000 (63%). Table 2 shows sectors and occupations where participants currently or previously earned income or were affiliated with respectively. Commercial fishing was the occupation from which the highest proportion of respondents currently earned income, followed by marine recreation and tourism and recreational sea fishing.

Respondents provided part of their postcode, which was used to match them to relevant census geographical information. Most respondents resided in England, specifically the Northeast, South East and North West regions (Figure 3).

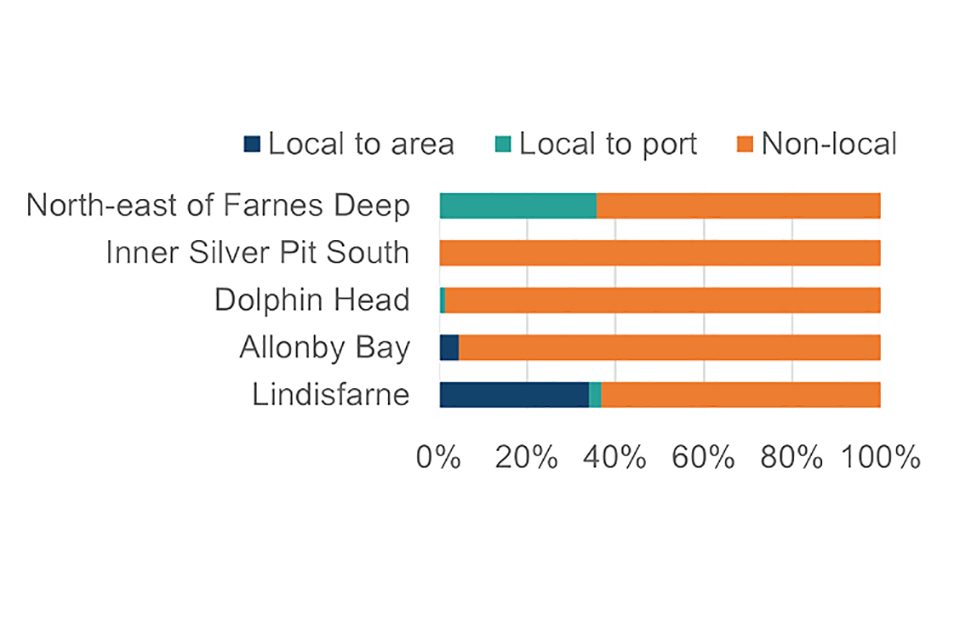

Based on supplied postcode data, 75% of respondents resided less than 10km from the coast, with the majority (58%) residing within 1km of the coast. Forty seven percent were classified as residing in a rural location, with the majority of 53% classified as residing in a rural location. Figure 2 shows the proportion of respondents who resided within the area of an inshore HPMA or a port associated with an inshore or offshore HPMA.

Table 2. Percentage of individual respondents by whether they currently or previously earn income or are otherwise affiliated with marine occupations (505 respondents)

| Occupation | Current income | Previous income | Other affiliation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commercial fishing | 7.9% | 4.9% | 6.6% | |

| Ports and shipping | 0.7% | 0.7% | 0.4% | |

| Defence | 0.8% | 2.1% | 0.3% | |

| Marine research (non-university or research institute) | 0.6% | 0.6% | 1.0% | |

| Marine policy making, planning or management | 0.0% | 0.1% | 0.6% | |

| Marine research (academic or university) | 1.1% | 0.8% | 1.3% | |

| Extraction of marine aggregates | 0.0% | 0.1% | 0.0% | |

| Marine conservation activities | 0.7% | 0.7% | 2.8% | |

| Marine conservation advocacy | 0.4% | 0.0% | 1.8% | |

| Sub-marine cabling and other infrastructure | 0.1% | 0.0% | 0.0% | |

| Seafood processing | 0.4% | 1.3% | 0.8% | |

| Offshore wind or renewable energy | 1.1% | 0.7% | 0.1% | |

| Offshore oil & gas | 0.4% | 2.3% | 0.3% | |

| Recreational sea fishing (incl. charter boat fishing) | 1.1% | 1.3% | 4.6% | |

| Fishing or recreational vessel maintenance | 0.7% | 0.6% | 1.3% | |

| Recreational boating | 1.1% | 0.8% | 4.2% | |

| Harbour operations | 0.6% | 1.0% | 1.5% | |

| Marine recreation and tourism | 2.1% | 1.5% | 5.4% | |

| Aquaculture | 0.0% | 0.3% | 0.0% | |

| Other | 2.3% | 1.3% | 2.3% | |

| Prefer not to say | 2.4% | 1.8% | 1.4% | |

| None | 75.4% | 76.8% | 63.2% |

Figure 2 Proportion of respondents local to area of inshore site or relevant port for inshore and offshore sites (722 respondents)

This stacked bar chart shows that within North Ease of Farnes Deep 36% were local to a port and 64% were non-local. At Inner Silver Pit South, less than 1% were local to a port and over 99% were non-local. At Dolphin Head 1% were local to a port and 99% were non-local. At Allonby Bay, 5% were local to the area and 95% were non-local. At Lindisfarne, 34% were local to the Lindisfarne area, 3% were local to a relevant port linked to that site and 63% were non-local.

Figure 3. Proportion of respondents by location of residence (689 respondents)

| Location | % |

|---|---|

| Northeast | 42 |

| South East | 25 |

| North West | 12 |

| South West | 6 |

| Scotland | 4 |

| Yorkshire and The Humber | 3 |

| London | 3 |

| East of England | 2 |

| Wales | 1 |

| West Midlands | 1 |

| East Midlands | 1 |

| EU | 1 |

This bar chart shows 42% of respondents were located in the North East, 25% in the South East, 12% in the North West, 6% in the South West, 4% in Scotland, 3% in London and Yorkshire and The Humber respectively, 2% in East of England, 1% in East Midlands, West Midlands and Wales and less than 1% in EU.

All candidate HPMA sites

This section summarises responses about HPMAs in general (including comments referring to all sites, or no site in particular). Responses from email responses and online events which were not specific to any site and general questions about HPMAs from the Citizen Space online survey are also included. This section also contains comments and views from respondents captured in online events designed to cover general issues across all HPMA sites. The responses described below do not specifically refer to particular candidate HPMAs, however comment and views described in Consultation responses: Candidate HPMAs may also relate to HPMAs proposals more broadly.

Survey respondents indicated the extent to which they supported or opposed the designation of pilot HPMAs in English waters. The majority of participants supported or strongly supported HPMA designation, although many also opposed and strongly opposed the proposals (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Responses to Q1, “To what extent do you support or oppose the designation of pilot HPMAs in English waters?” (775 responses)

| Response | % |

|---|---|

| Strongly support | 49 |

| Strongly oppose | 29 |

| Neither support nor oppose | 8 |

| Support | 7 |

| Oppose | 7 |

This bar chart shows that Strongly support was the most common response with 49% of respondents selecting this. Strongly opposed followed with 29% of responses. Supported was selected by 7% of respondents and opposed was also selected by 7%. Neither support nor opposed was selected by 8% of responses.

Across all email respondents, 26 organisations and individuals supported HPMAs, while 46 organisations and individuals opposed the proposals. Five respondents commented on the proposals without indicating support and two respondents could not be identified or the purpose of their email could not be identified.

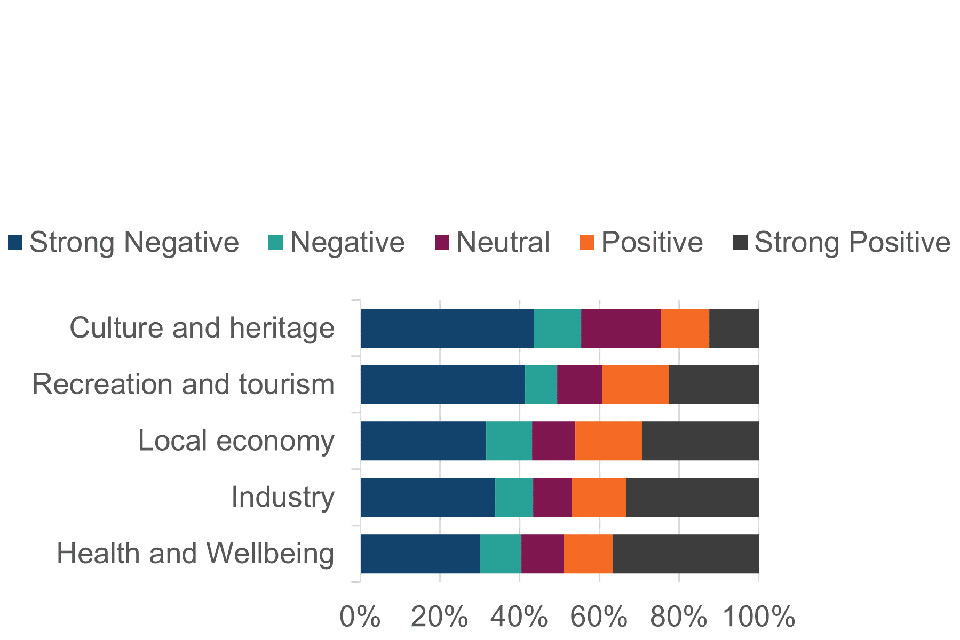

Citizen Space respondents indicated the effect they believed HPMAs would have on uses and values of the marine environment across five factors and these are reported excluding those who did not answer or selected don’t know (Figure 5). Negative effects were most frequently selected for culture and heritage, where a majority thought the effect would be negative for recreation and tourism. Positive effects were most frequently selected for Health and wellbeing and Industry.

Figure 5. Responses to Q2, “What effect do you believe HPMAs will have on the following uses and values of the marine environment?” (753 responses)

This stacked bar chart shows that for culture and heritage, the category respondents selected most frequently was strong negative (43%), followed by neutral (20%), negative (12%), positive (12% and strong positive (12%). For recreation and tourism, the category selected most frequently was strong negative (41%), followed by strong positive (23%), positive (17%), neutral (11%) and negative (11%). For local economy, the most frequently selected category was strong negative (32%), followed by strong positive (29%), positive (17%) neutral (11%) and negative (11%). For industry, most frequently selected was strong negative (34%), followed by strong positive (33%), positive (14%), neutral (10%) and negative (10%). Finally for Health and wellbeing, most frequently selected was strong positive (37%), strong negative (30%), positive (12%), neutral (11%) and negative (10%).

Reasons for support or opposition of HPMAs

703 survey respondents provided reasons for support or opposition to HPMAs. Out of these responses there were 653 that were not site specific which were divided of 376 that supported HPMAs (58%) and 277 who opposed HPMAs (42%). Of the 69 emails submitted before the consultation deadline, 23 email respondents were supportive of HPMAs (33%), with 39 in opposition to the proposals (57%). Five emails commented without a clear indication of support and two could not be coded.

Support for HPMAs

Of the 376 supportive responses the top reasons are:

- the need for HPMAs to address the climate crisis, biodiversity decline and declining environmental status (53%)

- more than half of respondents in support of HPMAs added a comment expressing their concern for the degraded nature of the marine environment, with multiple human-induced pressures; of these pressures, the most frequently referred to was large scale destructive, overly extractive or illegal fishing pressures - other pressures included climate change, plastic litter and pollution impacting the water column

- the benefits that HPMAs would provide the general public and future generations (13%)

- comments on benefits included the positive wellbeing people get from a healthy natural environment including the ability to safely partake in recreational activities such as diving or swimming

- the longer-term benefits of stock recovery from reduced fishing pressure (11%)

- the economic benefits of HPMAs for tourism (7%)

- the need for HPMAs to achieve international commitments (for example 30by30) (6%)

- MPAs provided an insufficient level of protection from human-induced pressures (4%)

- positive spill over effects of protected fish stocks, referring to successful case-studies (3%)

- protection from coastal erosion (1%)

- the protection of food supplies (1%)

- the research benefit of having a control or example area of full recovery (1%)

The 23 supportive e-mail responses cited the following reasons:

- environmental benefits such as enhanced marine biodiversity and socio-economic benefits such as medium to long-term opportunities for the fishing sector

- invaluable learning to gain scientific understanding on a range of issues of sustainable marine management such as improved protected area management, defining and measuring ecosystem recovery, climate adaptation and mitigation

- setting a precedent to measure the future success of protected areas.

- progress towards the UK government’s vision for clean, healthy, safe, productive and biologically diverse oceans and seas

- progress towards the IUCN World Conservation Congress (2016) recommendation for 30% of each marine habitat to be a HPMA

- HPMAs as an important link in establishing an ecologically coherent network of protected sites

- alignment of aims and objectives of the Water Environment Regulations and UK Marine Strategy to help create a better place for people and nature

- provision of geomorphological benefits for example , safeguarding core marine physical processes including erosion and movement of sediment

- provision of benefits from heritage assets to support habitats, ecosystem services, opportunities for stakeholder or public outreach on the value of HPMAs and improve understandings of the relationships between people and the sea

- increase in carbon sequestration and storage potential in UK seas and coastal habitats

- ‘fish recovery areas’ and an increase in the number, diversity and size of fish

Additional evidence submitted in support of HPMAs

The Wildlife Trusts ran a poll for their members to state support for HPMA designation and submitted the results of this as additional evidence via email. The campaign had 17,232 responses which showed support for HPMAs. In total, 38% of respondents wrote a comment and 69% of respondents provided a postcode. Postcode data were used to determine the closest candidate HPMA site to the respondent and their distance from the coast. Supportive comments came from across the UK, irrespective of how far people lived from their nearest proposed HPMA with support being representative to the distribution of the UK population with respect to the distance from the coast.

Opposition to HPMAs

Of the 277 survey respondents who oppose the designation of proposed pilot HPMAs top reasons are:

- direct impact on livelihoods of the community or those with commercial interests in the proposed pilot site (30%)

- indirect impact on dependent industries and people (22%)

- HPMAs are not necessary as existing activities were not damaging the natural environment or that existing conservation measures were adequate (18%)

- impact on the culture and heritage of the surrounding area (10%)

- HPMAs are the incorrect approach to conservation issues and damaging activities such as bottom trawling should be addressed as a priority (7%)

- impact on recreational activities (angling, diving, swimming) or wellbeing (7%)

- HPMAs causing displacement or conflict due to spatial squeeze (4%)

- HPMAs are difficult to enforce (1%)

- lack of prior engagement with affected stakeholders or a negative experience with the consultation for pilot HPMA sites (1%)

Additional qualitative data analysis revealed that of the 30% who noted a direct impact on livelihoods, most referred to the economic and social impact on local communities, including the small-scale fishing sector and to a lesser extent tourism. There was concern for unemployment in small-scale fisheries and this concern was seen to outweigh the justification offered for the designation of proposed pilot sites. Of the 18% who stated that HPMAs were not necessary as existing activities were not harming the environment, most referred to sustainable fishing practices such as potting and conservation bylaws leading to flourishing seas locally. A proportion of these respondents felt that catch and release angling was not damaging, particularly in comparison to large scale commercial fisheries. Several of the nine reasons for opposition were supported by comments on a lack of consideration for the management of the local environment, local knowledge and traditions.

Reasons provided in the 39 e-mail responses from those who opposed HPMAs were:

- economic and social costs of fisheries displacement:

- non-economic consequences of displacement, including safety, CO2 emissions, increased fishing effort and impact on blue carbon storage elsewhere, changes in seafarer behaviour and traffic patterns, leading to a higher risk of vessels working in closer proximity increasing the probability of conflict and collision - “Unlike farmers, fishers do not hold legal title to their production areas, and this makes fishing uniquely vulnerable to displacement”

- ecological costs of fisheries displacement:

- government needs to understand the ecological impacts of fisheries displacement caused by HPMAs and ensure that marine plans address competing demands without shifting ecological damage onto other sensitive sites.

Alternative Proposals

Email and survey respondents outlined alternative proposals for HPMAs as a whole:

- there should be more HPMAs:

- suggestions ranged from 10% to 30% of English seas, all MPAs should be HPMAs, or five HPMA sites should be the minimum, with fewer sites reducing the value of learning from piloting

- pilot HPMA sites should be smaller:

- smaller sites would likely have greater stakeholder acceptance and should be placed at locations meaningful for biodiversity conservation and nature recovery and suggested using offshore windfarms areas

- do not pilot HPMA sites but instead focus attention elsewhere:

- areas suggested were to look at overcapacity in the fishing fleet and to ensure effective conservation management across the Marine Protected Area network, where the same capacity is displaced to fewer areas

Views of the HPMA Selection Process

Many responses shared views on the design of the HPMA piloting process thus far.

- a lack of support for the selection process overall

- site selection:

- nature protection and driving the recovery of nature should be the primary consideration of decisions on HPMA site designation and protection

- areas of extensive fishing should not be considered for HPMAs due to the projected positive medium and long-term socioeconomic outcomes

- site selection had been skewed through the exclusion of activities of national strategic importance which can cause negative environmental impacts (for example, ports or harbours, aggregate dredging and offshore energy)

- whether the whole site approach is met if shipping would still be allowed in HPMAs

- overlap with fixed activities such as harbours and blue carbon storage licence areas to continue to be avoided and therefore the current approach was supported

- consequences of designation of HPMAs on sites of archaeological or historic interest are yet to be considered

- flood management activities need to be permitted in HPMAs to fully support designation

- stakeholder engagement:

- the consultation has been rushed without meaningful engagement with the fishing sector

- the choice of potential sites had not been considered in a stepwise approach, breaching trust gained through the Marine Conservation Zone designation process

- a lack of recognition of social and economic implications of HPMAs could affect future attempts for government and industry sustainable co-management of fisheries

- urgent necessity of meaningful stakeholder engagement on site boundaries and management measures

- the consultation events had not been well advertised, with suggestions to advertise through local angling clubs and notices at local marinas

- the rationale and evidence used for identifying candidate sites:

- a lack of clear, verified and local information on current fishing activity at the HPMA sites is harming stakeholder good-will and buy-in and there is not enough understanding on the impact of HPMAs on displacement and an approach to address these impacts

- using national level data was too broad

- the proposed conservation objectives are not compelling justifications for designation, against the backdrop of prospective socio-economic impacts to industry

- indefinite closures of areas of the sea without clear conservation objectives is not supported by the Marine and Coastal Access Act (2009), nor is the authority to experiment with spatial closures

- the economic impacts of HPMAs are inconsistent with the Fisheries Act 2020 where fisheries management should be based on best available scientific evidence and that fisheries management should be conducted through a Joint Fisheries Statement

Areas of further consideration

Addressing data gaps

Several UK and EU organisations detailed current data gaps that require addressing prior to the implementation of HPMAs:

- clear baselines of what the HPMA sites habitat and species status should look like to monitor progress against and timeframes for habitat recovery

- costs to businesses

- fishing effort data, including for <12m vessels, with a suggestion data should be sourced from landing declarations at the port

- fishing vessel displacement impacts on the wider ecology

- cumulative effects of spatial squeeze

- quantified gear conflict and localised effort increases due to displacement

- the quantified impact of bottom trawling on carbon storage areas

- further evidence on the damage caused by fishing types in general and in relation to blue carbon habitats and the trade-off between steaming further burning more CO2 and the protection of blue carbon

Managing HPMAs

- favourable condition thresholds for attributes in the supplementary advice to the conservation objectives should be strengthened by Natural England, aligning Water Environment Regulations, Water Framework Directive metrics for the HPMA attributes to high status thresholds

- government should set out the governance structure for monitoring and management of HPMAs, including enforcement

- consider how inshore HPMAs may interact with Flood and Coastal Erosion Risk Management (FCRM) activities such as beach management below Mean High Water Springs

- assessing existing permits for inshore HPMAs which will require remediation, for example the active sea trout fishery at one of the proposed sites

- monitoring should be agreed, sufficiently resourced and in place before designation to inform adaptive management

- Defra should set out a clearer timeline and objectives for monitoring, reviewing, and reporting on the implementation of the pilot HPMAs

Outreach

- government should establish ongoing outreach programmes, taking a values-based approach to promote and support the societal benefits of effectively managed Marine Protected Areas for ecosystem recovery, economic and environmental resilience, and climate change mitigation

Identifying protected features

Defra should compile a list of species and habitats that would benefit from protection and what habitats would best capture carbon.

Consultation responses: candidate HPMAs

Overview

This section summarises responses relevant to specific candidate HPMA sites. It includes site specific questions within the Citizen Space online survey, email responses which focused on a particular site, and views from attendees at site-specific online and in-person stakeholder events (See Annex 1).

The two inshore candidate sites of Allonby Bay and Lindisfarne received a total or 471 responses via Citizen Space, with 40 email responses referencing these sites. Offshore candidate sites (Inner Silver Pit South, North East of Farnes Deep and Dolphin Head) received 301 responses alongside 33 email responses. The site-specific survey questions with the highest number of responses was Lindisfarne, with 369 Citizen Space responses and the site received the highest number of emails referencing a specific candidate HPMA (29). This represented 50% of the overall consultation response on Citizen Space and 42% of email responses.

Allonby Bay

Short summary of consultation responses

There were 113 Citizen Space survey responses to the Allonby Bay candidate HPMA and 11 emails. The majority of survey respondents supported or strongly supported the proposal to designate a HPMA (76%).

Seventy nine percent of the site-specific survey responses agreed that designating a pilot site at Allonby Bay would further the protection of the marine ecosystem. Most respondents selected that designation would have a positive impact on ecosystem services, including sequestration and storage of atmospheric carbon (64%), coastal protection or minimising erosion (69%) and nursery or spawning areas for commercially important fish and shellfish species (77%).

One respondent who attended at the Maryport drop-in noted in relation to intertidal rocky scars sub-features “the scars…have deteriorated 90% of what they used to be, they do need to regenerate – they are nowhere near what they used to be”. Other respondents specifically citing possible positive of designation being coastal protection or minimising erosion, sequestration and storage of atmospheric carbon, and nursery or spawning areas for commercially important fish and shellfish species.

Commercial fishing views

Twenty-one individuals (some of these respondents (at least 4) indicated elsewhere that they may not fish the site commercially) responding to the survey reported commercial fishing activity with 11 supporting proposals to designate a HPMA. One response suggested catch would increase over time (as with other MPAs). Another emphasised the need for monitoring and periodic review of the success or otherwise of the measures.

However, others did not believe that designation would impact the ecology of the area because commercial fishing did not take place and other types of fishing had minimal impact. Others suggested that because the site is in favourable condition no additional protection is needed and the main pressures were coming from land-based sources. A lack of community support was also mentioned. A further response suggested that the existing management measures were enough but insufficiently enforced.

Fishers responding to free text questions and who opposed the proposals, emphasised the impacts of HPMA designation would include a decision to fish in a different area with mobile gear and the health and safety impacts of being moved further from the area in inclement weather. At the Maryport drop-in, one fisher said that it was too dangerous to fish elsewhere due to the size of his boat, and that it wasn’t possible to change gear. He noted that there were four other fishers in a similar situation. One also indicated that he would have to sell his vessel.

The most commonly cited fishing gear used was pots, with the most commonly targeted species being lobster and crab. Other gears were used and species targeted and there were seasonal fluctuations in effort. The primary use of static gear was consistent with views heard at the drop-in sessions that the Marine Management Organisation (MMO) was looking to encourage fishers away from mobile gear. Vessels which fished the area were registered in Maryport and Whitehaven. Income and effort data collected via the survey indicates that there is a little more effort in the site than identified from available desk-based data sources. Respondents suggested that the HPMA could lead to an increase in their travel time and have health and safety impacts as a result.

Recreational angling views

Angling, both shore and boat based, was an important use of the site and 20 respondents to the Citizen Space survey reported undertaking some angling. About half are involved in catch and release only, whilst others caught (at least in some part) for consumption. Five individuals fished using their personal boat, mostly moored in Maryport harbour. Disabled anglers were noted as using the site from the shoreline.

Forty five percent of angling respondents strongly opposed the plans for a HPMA with some suggesting they would sell their boat, modify their platform or relocate but at additional costs. Those responding also doubted the restrictions would have an ecological impact given the good condition of the site and cited their personal histories of angling in the area, including the significant contribution to mental health and family cohesion it has provided. Respondents also reported angling came from outside the area, providing a significant income for the local economy. These respondents suggested that both local and outside anglers would travel outside the local area if angling was significantly reduced and spend their money elsewhere.

Anchoring and other marine uses

Twelve survey respondents reported anchoring in the proposed HPMA with half strongly opposing the designation and only four indicating they used the area ‘often’. One respondent reported that automatic identification systems (AIS) and RYA’s SafeTrx app indicated low use of the area(although noting the limited coverage of this). The majority of users who anchored at the site used the area for tourism and leisure, with others reporting use of the area for professional water sports and education or research purposes. A national diving organisation contended that it was bad practice to anchor during diving excursions unless something was wrong with the engine. One respondent reported youth groups used the area for sailing, however this would not be restricted by HPMA management measures. Individual responses suggested that they could move their activity south of Maryport, but this would have health and safety implications because of the tidal and water movements pushing vessels operating south of Maryport towards Whitehaven and out to sea.

Other benefits and impacts

Respondents also reported a range of other potentially negative impacts of designation. There was a strong objection to the proposal on the basis of the need to maintain Allonby Beck, and other areas identified for Flood and Coastal Risk Management activities, including along the B300. Other concerns were raised regarding the viability of Maryport marina, which could lead to job losses and wider impacts on the local community and economy. Allonby Bay buffers World Heritage Site ‘Frontiers of the Roman Empire, an Outstanding Universal Value and Scheduled Monuments’ and one response to the consultation highlighted that the consequences of designation for any sites of archaeological or historic interest have not been considered.

Views on boundaries

Fifteen survey respondents suggested some changes to the boundaries of the HPMA. The majority suggested enlarging the site, with two suggesting including the Solway Firth and all other Marine Conservation Zones (MCZs) off the Cumbrian coast, indicating that larger sites lead to better ecological outcomes. It was suggested moving the northern border so that commercial vessels could transit in open waters, allow channel and buoy maintenance. A further suggestion was to pull the site boundary 200 to 300 yards away from the beach to limit the impact on anglers. We also heard recommendations to move the site to another area or extend it north. A proposed change to the north-western boundary of the site to mitigate against potential impacts to any channel and buoy maintenance activities related to the Port of Silloth.

Management, compliance, and enforcement

Respondents raised some process concerns, in particular around the advertising of the Maryport drop-in sessions, although attendance at this and the evening session totalled 16, in addition to a number of direct interviews conducted by the Defra team. Further concerns were raised about the evidence for the required management measures not being clear during the consultation.

Policy response

After reviewing the evidence the Secretary of State intends to designate Allonby Bay as an HPMA. The pilot site is estimated to provide high ecological benefits including the protection of ‘blue carbon’ habitats, which capture and store carbon, and provision of nursery and spawning habitats for a range of commercial species. The consultation also showed high levels of support for the site. The boundary proposed for designation has been modified to allow for an area of recreational angling, including access for disabled anglers, and for other activities to continue due to its importance to the community and takes account of the needs of Maryport Harbour and the Port of Silloth while still delivering important biodiversity benefits.

Lindisfarne

Short summary of consultation responses

There were 372 Citizen Space survey responses to the Lindisfarne candidate HPMA and 29 emails. Eighty four per cent of survey respondents opposed the proposal with the majority (83%) strongly opposing the plans.

The majority (65%) of respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed that designation would further the protection of the marine ecosystem. The majority believed that designation would have no impact or a negative impact on sequestration and storage of atmospheric carbon (63%), coastal protection and minimizing erosion (75%) and nursery and spawning areas for commercially or recreationally important fish species (65%).

Among those who opposed the HPMA at Lindisfarne, many respondents queried the ecological basis of site selection and the impacts of activities including potting and water quality. Respondents maintained that the existing MPA is a well-managed site and in increasingly good condition due to the range of existing designations, IFCA bylaws and conservation efforts by fishers and other users.

Commercial fishing views

Eighty two respondents engage in commercial fishing, with the largest proportion fishing multiple times a week. Fifty six per cent of these commercial fishers have more than three quarters of their fishing effort and average landed catch revenue within the boundaries of the candidate HPMA. Fishers primarily targeted edible crab and European lobster and occasionally caught included cod, haddock, mackerel, whelk, coley, squid, octopus and scallop. Most commercial fishing respondents used pots.

Ninety six per cent of Lindisfarne commercial fishing respondents opposed or strongly opposed the proposal to designate. Most commercial fishers responding via Citizen Space said their livelihoods were either highly dependent (53%) on commercial fishing and that their current activity would be significantly (57%) impacted. As a result of designating a HPMA, the majority of fishers identified significant increases in fuel costs, vessel maintenance costs, gear maintenance costs, time spent travelling to fishing grounds and labour costs and a significant decrease in crew share and catch. Fishers noted concerns over gear conflict between coastal towns, impacts of overcapacity on other grounds and the carbon footprint of additional steaming time would cancel out benefits of protecting blue carbon. They also noted knock on effects on supply-chain businesses, including seafood processors and traders that would lead to job losses and loss of port or harbour fees.

Most fishers stated they could not move their activity to an alternative location and they could not modify their gear if a pilot HPMA were designated. It was reported that fishing was the best paid source of employment on Holy Island with few alternative livelihoods available outside of seasonal tourism and was responsible for around a third of all employment opportunities on the island.

Recreational angling views

Sixty-nine survey respondents use the area for recreational sea fishing with 49% of these fishing less than once a month. There was a mixture of boat based and shore based fishing and a mixture of catch and release and catching for consumption. There were different views on the extent of recreational angling. Some reported low levels of activity, others noted its significance for summer tourism.

Anchoring and other marine uses

Fifty-six survey respondents reported anchoring at the site. Other marine uses included community and cultural events, education and research, tourism and leisure and professional water sports. Activities noted included motor boating, sailing, charter fishing, scuba diving, walking and dog walking.

Of those anchoring at the site, 91% were opposed or strongly opposed to the proposal to designate an HPMA. People raised concerns about the loss of income and work (with impacts for their family) and that people may not visit the area for particular activities such as wildlife watching, scuba diving and motorboating. Anchoring was flagged as a safety necessity due to high currents in the area. It was reported that one third of the local harbour dues come from people using the HPMA. The cultural importance of Lindisfarne beyond fisheries was also highlighted.

Other benefits and impacts

A range of responses highlighted further impacts for the Holy Island community:

- the area has higher than England average levels of unemployment and a higher proportion of people with no qualifications - fishing is a key area of employment

- impacts to marine infrastructure, including the harbour which the fishing community contribute to maintenance and upkeep

- significant impacts on culture, heritage and community; fishing vessels are run as small family businesses passed through generations - fishing has been linked to Holy Island for hundreds of years

- the Holy Island community is physically isolated and mainland emergency services cannot always reach the community due to tidal coverage of the causeway - emergency service provision on the island is threatened by lack of coastguard staffed by local fishers

- viability of the local school if fishing families leave

- physical and mental health impacts due to declining industry and livelihood uncertainty

- wider de-population of Holy Island with people leaving the island to seek alternative employment opportunities

- there are navigational aids in Lindisfarne that may need to be moved

Views on boundaries

Suggestions on boundary changes included moving the boundary offshore to omit potting areas and protect different species; considering a smaller site to the east of Holy Island including Budle Bay and immediately offshore; enlarging the site and include Fenham Flats, changes to allow shore angling at specified locations and to allow boat angling in the Farnes complex and consider a number of smaller protected areas that may have better buy in. Several responses noted that boundaries should be designed with local stakeholders.

Management, compliance and enforcement

Both those who supported and opposed the proposals expressed views on management, compliance and enforcement. It was suggested the fishery has grown over the past 15 years because of the collective policing by MMO, fishers, IFCA and traders. The need for additional costs and resources were noted and the current role of the IFCA highlighted. The need to invest in water quality monitoring was stated. There were suggestions that the coastguard, environmental NGOs, Lindisfarne wardens and Seasearch divers could help with monitoring and tools such as vessel monitoring systems (VMS) and remote electronic monitoring (REM) were noted alongside the lack of a baseline to measure against change.

Responses stated that the lack of support locally would make management extremely difficult and community buy-in is essential for its success. The area is self-managed by the fishers so the loss of the fishing community would mean loss of this management capacity. One suggestion was for a fisheries management plan be drawn up for the wider area to minimise impacts and support any affected.

Other emerging themes and issues

Many stakeholders who opposed the candidate HPMA emphasised that there was wide ranging community support for marine conservation.

The North East Marine Plan was referred to and the question raised of whether this had been considered in the process of developing proposals for a candidate HPMA.

Many stakeholders who responded with an interest in the Lindisfarne site criticised the process by which the site was selected, encompassing shortlisted site selection, engagement and the consultation process itself.

In relation to some or all of the above issues, several responses called for a rapid decision to be taken to exclude the Lindisfarne site from further consideration as a candidate HPMA site in order to alleviate deep concern within communities affected.

Policy response

After reviewing the evidence the Secretary of State has decided not to designate Lindisfarne as a HPMA. Although the designation of the site is estimated to provide high ecological benefit, we have listened to the concerns from the local community about its selection and the socio-economic impacts it would have. Lindisfarne has a tourism industry that is dependent on existing activities and therefore potential for increased tourism benefits through designation is reduced.

There is a high level of dependency in the local area on employment opportunities provided by the activities currently taking place in the site and this extends onto the connected industries. One third of Holy Island residents are employed in commercial fishing. The geographical isolation of a large number of this site’s stakeholders provides additional cost implications, including that it is difficult for them to switch jobs. Additionally, due to the community’s isolation and self-dependency, designation would raise a number of health and safety concerns. Significant numbers of stakeholders had concerns around the loss of fishing activity which was a valued aspect of wider community identity and local heritage. Our survey highlighted that secondary impacts included loss of school and coastguard provision due to fishers and families moving away from the island, mental health impacts and impacts on wider culture, heritage and community.

North East of Farnes Deep

Short summary of consultation responses

There were 93 responses to the North East of Farnes Deep candidate HPMA on Citizen Space and five emails. Sixty nine percent opposed or strongly opposed the proposal to designate a pilot HPMA.

Some stakeholders raised that the area is commonly known as Farne Deeps; however, the North East of Farnes Deep is consistent with the existing Marine Conservation Zone.

The majority of survey respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed that designation of a candidate HPMA at North East of Farnes Deep would further the protection of the marine ecosystem (60%). The majority also believed there would be negative impacts on carbon sequestration and storage (31%), and nursery or spawning areas for valuable species (28%).

Respondents were concerned that displacement could increase pressures from fishing in other areas. One respondent also queried whether the site could make a difference to ecological outcomes, because it was not large enough and may require additional footprint or a buffer zone compared to the existing MPA. Another respondent contended other sites nearby may have made more suitable choices according to the ecological criteria, providing coordinates for this. Five respondents suggested enlarging the site boundaries. Additional responses confirmed the view that restrictions may not have an impact, while increasing fishing pressure at other sites.

Commercial fishing views

Twenty-five survey respondents engaged in commercial fishing. However, one of these respondents referred to fishing the Farne Deeps and two referred to the Farne Islands, so it is likely that some respondents misunderstood the location of the candidate HPMA. There was a varying degree of regularity in terms of usage of the site for commercial fishing, with most commercial fishers (68%) using the site less than once a month. The most common species fished in the area is Norway lobster. Other species fished include Atlantic scallop, cod, haddock, langoustines, squid, sandeel, mackerel, whiting, herring and plaice. The gear used was otter trawls, pots, lines and pelagic trawls, and almost half of responding commercial fishers stated they would not change gear if a HPMA were to be designated. Three respondents stated that they would change gear. Of the fishing effort taking place in the site, six respondents said this was less than a quarter of their effort, with three saying this was between half and three quarters of their effort. Additionally, two commercial fishers stated that 100% of their fishing effort and landed value came from the site. Non UK fishers fish the site including French and Danish vessels. Exactly half of commercial fishers stated that their livelihoods were at least slightly dependent on the site.

Respondents raised concerns about the designation of the site as a HPMA and its potential impacts. These concerns included an increase in the cost of labour and fuel, the safety implications to and possible endangerment of crews and vessels due to moving further offshore, the time it would take to chart alternative sites and possible damage to equipment when doing so, displacement, spatial squeeze and the serious economic consequences to fishers. Respondents gave mixed opinions on what they would do if the HPMA were designated; some would continue fishing there, some would move elsewhere and some would stop fishing completely. One respondent suggested that the relaxation of rules on foreign crews or additional quota could help ease costs and support opening new fishing grounds.

Recreational angling views

Fifteen survey respondents used the site for recreational fishing, of which 12 also used the site for commercial fishing. Of the 15 recreational fishers, there were varying degrees of regularity of use of the site, with the majority (10) reporting that they fished less than once a month. It was evident that some angling respondents were not active in the offshore North East of Farnes Deep site but referred to opportunities around the Farne islands. However, others were clearly commercial fishers who undertook catch and release recreational fishing within the site. The majority of recreational anglers (93%) strongly opposed the designation of the North East of Farnes Deep as a pilot HPMA, with only one respondent strongly supporting the proposal. If this HPMA were designated, one recreational angler explicitly said that they would continue to fish in the site and would not modify their activity.

Other benefits and impacts

Nineteen percent of respondents used the site for education and research purposes whilst 19% used the site for professional water sports. Nine respondents used the site for recreational diving. Responses varied regarding the impact of potential HPMA designation on activities, with some believing the impacts to be somewhat significant whilst others believed there would be no impact. In several cases, free text comments suggested the site was not regularly used for recreational diving or as a destination for tourism, as a number of these referred to the Farne Islands, outside of the present site boundaries but within the Lindisfarne candidate site boundary.

Views on boundaries and potential boundary changes

Thirty nine percent of survey respondents commented on potential changes to boundaries. One respondent expressed the view that the site should be removed as a candidate HPMA altogether due to restrictions not meeting stated conservation objectives, others emphasised the need for better VMS data, evidence, mapping and descriptions for potential impacts. Several respondents requested that the Wildlife Trusts’ advice was followed regarding boundaries. Twenty respondents recommended expanding the site for a range of reasons including better meeting conservation objectives and national targets. One respondent provided specific coordinates to move the southern boundary north to reduce fisheries impacts and another suggesting the inclusion of a buffer zone. A few respondents supported the current boundaries.

Management, compliance, and enforcement

Respondents expressed mixed views that current or future designations, the current capacity for enforcement, and capacity for monitoring would be positive for ecological outcomes at the site. Respondents suggested that the presence of REM, iVMS and future monitoring of fishing vessels would be important in the effective implementation of monitoring and enforcement. Several respondents stated that, for HPMAs to be successful, the capacity for monitoring and enforcement and the degree of compliance were all important, adding that they may require greater resourcing or implementation. Some respondents rejected the proposals completely, believing enforceability to be unnecessary or too difficult, especially concerning foreign vessels.

Other emerging themes and issues

Fifty-two percent of respondents for Lindisfarne also answered site specific questions for the North East of Farnes Deep. One comment explicitly raised that the proposals for two candidate HPMAs were in the North East, with significant social and economic impacts conflicting with the levelling up agenda.

Policy response

After reviewing the evidence the Secretary of State intends to designate North East of Farnes Deep as an HPMA. Together with high levels of biodiversity and complex seabed habitats, the area has the potential to contribute to a range of benefits including carbon storage in the large muddy habitats and spawning and nursery habitat provision for commercial species. The pilot site is estimated to provide high ecological benefits and the costs at the site are low, indicating very good net social value (comparing benefits to costs) in designating the site.

Inner Silver Pit South

Short summary of consultation responses

There were 29 Citizen Space survey responses to the Inner Silver Pit South candidate HPMA on Citizen Space and 13 emails. Fifty nine per cent of survey respondents supported the proposal to designate a pilot HPMA at Inner Silver Pit South, with 45% of these strongly supporting the plans.

The majority of survey respondents agreed that designation would further the protection of the marine ecosystem (59%). Forty six per cent of respondents selected that designation would have a positive impact on sequestration and storage of atmospheric carbon and 50% selected that designation would have a positive impact on nursery or spawning areas for commercially or recreationally important fish species.

Comments noted that the Silver Pit is a unique feature in the southern North Sea and a known biodiversity hotspot for marine wildlife including fish, cetaceans and seabirds, designation may help recover commercial species. It was noted that spill over may not happen here as there were natural feature boundaries for crab and lobster and that there is scientific evidence that no-take-zones are not the most ecologically beneficial.

Commercial fishing views

Four of the 29 survey respondents, engaged in commercial fishing. In terms of fishing effort and landed value generated within the boundaries of the HPMA site, one fisher estimated that less than quarter of their fishing effort and landed value was generated within the boundaries of the HPMA site, two estimated between a quarter and a half, and one stated that all of their fishing effort and landed value is within the bounds of the site. Email responses noted the economic value of the fishery was £13.3 million in 2021 with lobster and crab noted as the main target species. It was noted that they may not fish every year here as they also fish for red mullet closer to the coast. At the Bridlington drop-in, fishers queried Defra’s data on fishing activity, suggesting that VMS pings are probably too high and instead represent vessels steaming more slowly across the site.

Fishers targeted edible crab, European lobster, whelk, sprat, whiting and mackerel. The primary gear used is pots, with some using pelagic or demersal trawls. Trawlers were noted to be mainly in deeper water around the edges of the pit.

Several impacts to commercial fishing were listed including displacement, spatial squeeze, higher fuel costs, limited ability to relocate due to congestion in the area and location of target species within candidate site, socioeconomic impacts to both the fishing industry and indirect impacts to others such as food prices rising following the designation of the candidate HPMA. It was noted that the site is a good lobster area, with consistently high catches reported and a seasonal rotation between lobster grounds where gear is left to protect the grounds in between from mobile gears. “30 years ago it would have been constantly beam trawled. The scallop dredgers and French trawlers have gone, so it’s just static gear now. It’s recovering on its own”. Health and safety issues were raised in the context of too much gear on the grounds and the risk of ropes taking people out.

Particular displacement concerns for this site were that a HPMA will concentrate impacts elsewhere with potentially greater socio-economic impacts nearshore or pushing smaller boats offshore; existing aggregate dreading, the construction of offshore wind farms, gas exploitation and exploration, and marine protected areas has already led to displacement and has increased the importance of the candidate site to fishers; gear conflict between static and mobile gear may be exacerbated.

Recreational angling views

A single respondent used the site for recreational fishing and also for commercial fishing. The respondent strongly opposed the proposal to designate this site as a HPMA, given their livelihood depends on fishing in the area.

Other benefits and impacts

Five respondents reported using the site for other activities such as water sports, education and research, surveying, dredging, crossings, oil and gas exploration, windfarm cabling maintenance for the Hornsea Two windfarm. Several respondents raised concerns about impacts on cabling, marine aggregate dredging or future anchorages. A respondent noted the importance of considering marine spatial planning during designation in relation to delivering the government’s targets of 50GW of offshore wind generation. Others noted the presence of seismic data for the area and a potential carbon storage area and the potential for sustainable ecotourism because marine mammals have been spotted in the area. A further stakeholder noted that the site is a glacial feature and that there is a lot of historic interest in the area.

Views on boundaries

Nine respondents were in favour of boundary changes, whilst five were against boundary changes. Several of these said that the site boundary should be expanded to cover a bigger area. Others suggested changes to avoid of buffer existing marine industry activities including a recently installed interconnector cable.

Management, compliance, and enforcement

Many respondents reported that more management or enforcement would be needed if the site were designated. The shape of the site was noted as potentially difficult to enforce. There was a request to work with non-UK fishers on regulatory measures after designation of HPMAs.

Suggestions were made via Citizen Space on how monitoring and enforcement could be effectively implemented at the candidate HPMA site. Suggestions included:

- allocating resources to the responsible agencies or authorities

- making use of various bodies including regional universities, eNGOs, consultancies and NE, JNCC, MMO, Cefas, Coastguard, local Wildlife Trusts

- use of technology such as flights, active tracking of vessels, use of vessel monitoring systems (VMS) and in-shore vessel monitoring systems (iVMS), remote electronic monitoring (REM) with cameras, Automatic Identification Systems (AIS) with financial support given by DEFRA to boat users to digitise where needed

- using remotely operated vehicle (ROV) surveys, towed sledge videos and drop-down videos with high-quality of imaging

- marking HPMAs on Admiralty Charts

- conducting stakeholder engagement to raise awareness of HPMAs and associated value

- various suggestions from the Benyon Review concerning monitoring

Policy response

After reviewing the evidence the Secretary of State has decided not to designate Inner Silver Pit South as an HPMA. This is because of the relatively high costs to fishermen incurred by designation. The commercial fishing in this site is comparatively productive compared to the surrounding areas. As well as incurring high costs from designation, the benefits would be comparatively low. As a result, the analysis shows the net social value (comparing benefits to costs) was the lowest across all sites. Therefore, we consider the benefits of designation would not sufficiently outweigh the impacts on fishers.

Dolphin Head

Short summary of consultation responses

There were 177 Citizen Space survey responses to the Dolphin Head candidate HPMA and 15 emails. Ninety seven percent of survey respondents supported the site.

Ninety-eight percent of survey respondents strongly agreed that pilot HPMA designation at Dolphin Head would further the protection of the marine ecosystem, with the majority believing there would be positive impacts on carbon sequestration and storage (78%), and nursery or spawning areas for valuable species (94%). Comments from respondents who opposed the HPMA queried the basis for site selection and the ecological criteria. They noted that fishing methods used were low impact, it was a summer fishery only and that additional measures would not further conservation objectives. Several respondents raised concerns about wider external pressures such as shipping, water quality and climate change. There were concerns around the evidence used with the data for thornback ray challenged in several meetings along with the lack of detail in definition of full recovery of habitats and species or criteria to define success.

Commercial fishing views

There were 19 commercial fishing respondents to the survey. The most common species fished in the area is Atlantic mackerel. Other fishers target squid, sole, seabass and whelks. Gear cited included pair trawls (midwater), bottom trawls (including otter and beam trawls), scallop dredges, whelk pots and flyseines. The majority of fishers who answered survey questions identified increases in time spent traveling to fishing grounds as an impact of designation. However, respondents stated that there would be no effect or did not know what the effect may be on labour costs, vessel and gear maintenance costs, soaking time effort, and time spent fishing. There were mixed views on whether there would be an effect on catches or availability of quota. Respondents reported that a small number of below 10m vessels fish the area on a regular basis. These boats were not identified by the sightings data used for the original assessment. In the workshops views were also expressed that we had underestimated the catch from the area.

The majority of fishers responding to the survey strongly supported the proposal to designate a pilot HPMA at Dolphin Head. However others responding by email and attending site meetings, opposed or strongly opposed it. Reasons given for opposing the site were livelihood impacts, concerns about the sustainability improvements and concerns about displacement effects. Displacement effects highlighted including exhausting nearby grounds, interaction with other gears and it being an area of high industrial activity and impacts on the wider environment. Some fishers noted that the partially overlapping Offshore Brighton MCZ was agreed with stakeholders only with the expectation there would not be further restrictions.

Additional concerns were raised about crew availability (with some now employed by windfarms) and local shellfish stock collapse.

Recreational angling views

The offshore site of Dolphin Head was used by 11 Citizen Space respondents for recreational sea fishing with varying degrees of regularity and both for catch and release and for catching for consumption. Ten of the 11 respondents support the HPMA proposal with comments stating that this proposal is overdue and that banning certain types of fishing will increase stocks for recreational fishing. Information gathered also revealed charter boats had used the area in the past but the fishery was now depleted leading to low catches and long travel distances not making fishing there viable anymore.

Other benefits and impacts

Respondents raised concerns around any impacts on normal rights of passage and navigation for boats due to considerable shipping traffic in this area and the presence of the International Maritime Organization Traffic Separation Scheme. Fishers in particular expressed concern about shipping still being allowed and impacts of this on the HPMA. The impacts of the HPMA alongside other restrictions for commercial fishing may have broader implications for food supply and security. The site may also be of heritage interest due to the nearby aggregate area.

Views on boundaries

Thirty-nine survey respondents commented on potential boundary changes. 20 suggested increasing the size of the area. Other comments suggested moving the site west or reduce the size to decrease its impact to fishers and moving the eastern boundary to better protect cable infrastructure.

Management, compliance, and enforcement

The majority of survey respondents thought current or future designations, the current capacity for enforcement, and capacity for monitoring would all be positive for ecological outcomes at the site. Fifty-eight survey respondents made suggestions around effective implementation of monitoring and enforcement including:

- using of patrol vessels, remote sensing (radar, drones, buoy-mounted cameras, vessel monitoring systems, remote electronic monitoring) and Remotely Operated Vehicles (ROV) survey or towed sledge video or drop-down video ensuring clean, sharp images

- following recommendations of The Wildlife Trusts

- increasing resourcing of the statutory authorities and involving other partners such as HM Coastguard, RNLI, Sussex Sea Fisheries Protection, other vessel operators, divers, marine life tours, environmental groups, local universities, and conservation researchers

- communicating with, and getting buy-in from, the fishing community

- demarcating the area with buoys

Policy response

After reviewing the evidence the Secretary of State intends to designate Dolphin Head as an HPMA. The pilot site is important for its regionally high biodiversity, range of important and threatened species and habitats, and relative importance for commercial species. Designating a pilot HPMA here presents an opportunity to fully recover habitats and species present across the area and within the partially overlapping MCZ. The consultation response shows designation would be welcomed by a high majority of stakeholders, with very high support from recreational fishers and generally high levels of support from commercial fishers.

Next steps

Designation of pilot HPMAs

Following the Secretary of State’s decision that she intends to designate three candidate HPMAs, Defra will update documents such as factsheets. Legal designation orders will be published at designation.

Under the Marine and Coastal Access Act 2009, Defra is required to designate any chosen areas within 12 months of the start of the consultation; before 6th July 2023. Designation occurs by making a designation order under section 116 of the Marine and Coastal Access Act 2009. Similar orders can be viewed here. The order will state the boundaries of the HPMA, what it is protecting and its conservation objectives.

We will notify the European Commission ahead of designation as per the terms of the UK-EU Trade and Cooperation Agreement.

Managing HPMAs

Should any HPMAs be designated then Defra, its regulators and advisers and any other relevant public bodies will manage and monitor the HPMAs.

HPMAs are a material consideration for the MMO for marine licences, or decisions from other public authorities, from the point of consultation. Relevant public authorities are required to consider the effect of a proposed activity on the HPMA before authorising them, to ensure there is no significant risk of hindering the conservation objective. The MMO, for example, may need to develop byelaws to further the conservation objectives by prohibiting fishing activity in offshore HPMAs. The intention is that any measures needed will be implemented as soon as possible after designation and relevant consultation processes. To support authorities in their duties under the Marine and Coastal Access Act with respect to MCZs, Natural England and JNCC have developed high level conservation advice which is generic across the candidate sites. Site specific conservation advice will be developed for any sites designated. In addition, Defra are also producing guidance for public authorities to support decision making around licensing and consenting activities that have the potential to impact HPMAs.

Evaluating HPMAs

Natural England are developing an evaluation framework for HPMAs based on the application of natural capital principles and assessments methods, working with Defra, JNCC and others. The evaluation questions will be structured around environmental, social and economic impact and therefore enable a holistic evaluation of any HPMA designation. Baseline ecological and social and economic surveys are due to be undertaken within the first year of designation.