Financial Policy Committee powers of direction in the buy-to-let market

Updated 16 November 2016

1. Introduction

The global financial crisis exposed deep flaws in the financial regulatory architecture. Since then, the government has implemented an ambitious programme of reform to deal with the legacy of the crisis.

In June 2010, at his annual Mansion House speech, the Chancellor explained that a key weakness of the system of financial regulation was the lack of focus on broader risks across the economy, in areas such as the housing market.

As a result, the government created the Financial Policy Committee (FPC) within the Bank of England. The FPC’s responsibility, in relation to the achievement by the Bank of England of its financial stability objective, relates primarily to identifying, monitoring and taking action to remove or reduce systemic risks with a view to protecting and enhancing the resilience of the UK financial system.

The FPC is empowered to make recommendations to HM Treasury that it exercise its statutory power to enable the FPC to direct the Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA) and/or Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) to ensure the implementation of specified macro-prudential measures.

In his Mansion House speech on 12 June 2014 the Chancellor committed to ensuring that the FPC has “all the weapons it needs to guard against risks in the housing market”. He announced his intention to give the FPC “new powers over mortgages, including over the size of mortgage loans as a share of family incomes or the value of the house”.

In response to the Chancellor’s announcement, on 2 October 2014, the FPC recommended that it be granted powers of direction relating to housing market tools in relation to owner-occupied mortgages and buy-to-let residential mortgages.

Specifically, the FPC recommended that it be granted the power to direct, if necessary to protect and enhance financial stability, the PRA and/or FCA to require regulated lenders to place limits on residential mortgage lending, both owner-occupied and buy-to-let, by reference to:

- loan-to-value (LTV) ratios

- debt-to-income (DTI) ratios, including interest coverage ratios (ICRs) in respect of buy-to-let lending

In response to this recommendation, the government consulted on and legislated for powers of direction relating to LTV limits and DTI limits in respect of owner-occupied mortgages. The FPC has subsequently published a policy statement setting out how it intends to use its tools in the owner-occupied mortgage market.

In respect of buy-to-let mortgages, the government stated its intention to consult separately on the recommendations by the end of 2015. This consultation document fulfils that commitment.

Aims of the consultation

This consultation aims to gather views on how the operation of the UK buy-to-let mortgage market may carry risks to financial stability. It also seeks respondents’ opinions on the specific tools in relation to which the FPC has recommended it be granted powers of direction, including in their impact on business activity and prosperity; on the draft legislation; and on the consultation stage impact assessment.

The consultation is primarily targeted at individuals, institutions and associated bodies that would be affected by the FPC’s powers of direction (ie PRA- and FCA-authorised firms). The government also welcomes the views of other parties interested in housing market policies.

Following the consultation, the government will examine the consultation responses and use them to help to define the instrument that will place the powers in legislation. The government will set out how it intends to proceed in a consultation response document in 2016.

Structure of the document

The introduction above sets out the background to the FPC’s recommendations relating to specified tools in the housing market. The remainder of the document is set out as follows:

- chapter 2 provides an overview of the FPC and its powers

- chapter 3 provides an overview of the buy-to-let market and its role in the economy

- chapter 4 sets out how the buy-to-let market may carry risks to financial stability and outlines the tools by reference to which the FPC has requested powers

- chapter 5 includes a copy of the draft legislation

- chapter 6 includes a copy of the consultation stage impact assessment

- chapter 7 lists the consultation questions

Implementation

Section 9L of the Bank of England Act 1998 (as amended by the Financial Services Act 2012) allows HM Treasury to make secondary legislation prescribing macroprudential measures for the purposes of section 9H.

2. The Financial Policy Committee

Macroprudential Policy and the Financial Policy Committee

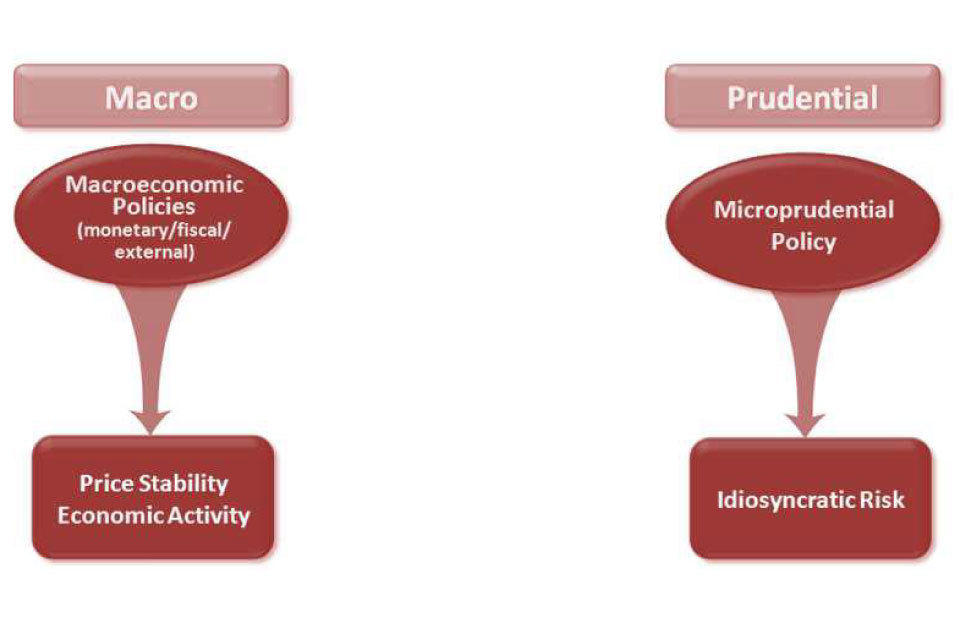

There has been increasing recognition that traditional microprudential policies allowed financial vulnerabilities to grow unchecked, contributing to the global financial crisis. An important lesson from the crisis has been that microprudential regulation – the safety and soundness of individual institutions, focused primarily on financial resources and idiosyncratic risks – is alone not enough to maintain financial stability.

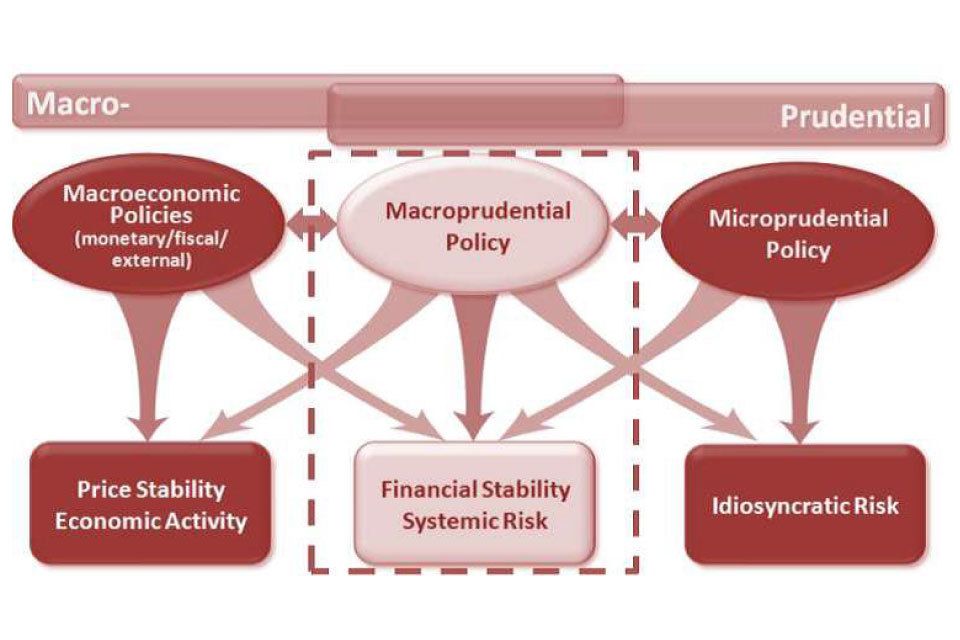

As a result, authorities across the world have sought a more systemic approach to financial stability. This holistic approach is called macroprudential policy.

However, macroprudential policy is not intended to displace microprudential policy but rather to complement both microprudential policy and macroeconomic policy (see Chart 2.A and Chart 2.B).

Macroprudential policy can deploy traditional regulatory tools, relying on the regulators for implementation and enforcement. However, it adapts the use of these tools to counteract growing vulnerabilities in the financial system by assessing two key dimensions of risk:

- Cross-sectional dimension of risk: the contributions of individual institutions to systemic risk at a given point in time. This is related to connections between institutions, the distribution of risk within the sector and structural factors, such as information asymmetries.

- Time dimension of risk: the evolution of systemic risk through time. This is related to over-exuberance in the upturn of the financial cycle – exacerbated by systematic under-pricing of risk – leading to asset bubbles, stretched balance sheets and other unsustainable expansionary trends. This can be monitored by tracking a wide set of macroeconomic and financial variables, such as the ratio of credit to GDP.

The UK has embraced macroprudential policy and is not alone in moving to incorporate macroprudential policy into its regulation of the financial system. The European Systemic Risk Board in the European Union and the Financial Stability Oversight Council in the United States are just two prominent examples of this international shift.

The UK government created the independent FPC within the Bank of England. The objective of the FPC is to contribute to protecting and enhancing the stability of the UK financial system[footnote 1]. However, given that there are interactions between macroprudential policy and economic activity (see Chart 2.B), the government provided the FPC with a secondary objective to support the economic policy of the government.

The FPC’s statutory responsibility in relation to the Bank’s financial stability objective is to identify, monitor, and take action to remove or reduce systemic risks with a view to protecting and enhancing the resilience of the UK financial system.

Chart 2.A: How we saw the world before the financial crisis

Chart 2A

Source: ‘The Interaction of monetary and macroprudential policies’, IMF, January 2013

Chart 2.B: How we see the world now

Chart 2B

Source: ‘The Interaction of monetary and macroprudential policies’, IMF, January 2013

The FPC has eleven members, of which ten are voting members. Its members are the Governor of the Bank of England, the Deputy Governors of the Bank, the Chief Executive of the FCA, the Bank’s Executive Director for Financial Stability Strategy and Risk, four external members appointed by the Chancellor, and a non-voting Treasury member[footnote 2].

The FPC meets on a quarterly basis, and it publishes a Financial Stability Report (FSR) every six months. The FSR sets out the FPC’s view of the stability of the UK financial system, together with an assessment of developments in, strengths and weaknesses of, and the risks to the stability of, the UK financial system. The FPC takes action based on this assessment.

Powers of the FPC

The FPC has two main sets of powers at its disposal. These are its powers of recommendation and powers of direction.

Reflecting its macroprudential role, the FPC is not responsible for making decisions in respect of individual firms; it can only make recommendations or issue directions that relate to all regulated institutions or to all institutions that meet a specified description. The role of the FPC is therefore a crucial complement to, but distinct from, those of the firm level regulators (the PRA and the FCA).

The Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR) and the Capital Requirements Directive IV (CRD IV) establish rules concerning the prudential supervision of banks and investment firms.

These rules contain a formalised framework for macroprudential measures, applying to all banks and certain investment firms, where they operate directly on risk weights, levels of own funds, large exposures, liquidity or microprudential buffers.

Powers of recommendation

The FPC has a power to make recommendations to the regulators – the PRA and the FCA – about the exercise of their functions, such as to adjust the rules facing banks and other regulated financial institutions. The FPC can issue these recommendations on a ‘comply or explain’ basis. Should the regulators decide not to implement these ‘comply or explain’ recommendations, they would be required to explain their reasons for not doing so[footnote 3].

The FPC is also able to make recommendations to HM Treasury, including on additional macroprudential tools that the Committee considers that it may need, and on the ‘regulatory perimeter’ – that is, both the boundary between regulated and non-regulated activities within the UK financial system, and the boundaries of different regulators within the regulated sector[footnote 4].

The FPC also has a broader power to make recommendations to any other persons. For example, this power allows the FPC to make recommendations directly to the industry or to independent bodies such as the Financial Reporting Council.

Powers of direction

The FPC also has a power to direct the regulators (i.e. the PRA and FCA) to exercise their functions so as to implement specific macroprudential tools. Currently, the FPC is the committee within the Bank of England that is responsible for two macroprudential tools that operate within the EU framework for macroprudential measures[footnote 5].

The FPC is responsible for policy decisions on the Countercyclical Capital Buffer (CCyB) rate for the UK[footnote 6].

- The FPC is required to assess and set the CCyB rate for the UK that applies to banks and the larger investment firms. Increasing the CCyB rate builds up capital when the FPC judges it to be the best approach to head off threats to financial stability. The CCyB rate would be decreased either when threats to stability are judged to have receded, or when the size of in-scope firms’ capital buffers is judged to be more than sufficient to absorb future unexpected losses and credit conditions and other relevant indicators are weak. The FPC’s decisions on the CCyB apply only to in-scope firms’ UK exposures.

The FPC has a power of direction relating to Sectoral Capital Requirements (SCRs).

- This allows the FPC temporarily to increase banks’ capital requirements on exposures to specific sectors. The FPC is able to adjust SCRs for exposures to three broad sectors: residential property, including mortgages; commercial property; and, other parts of the financial sector.

The CCYB and SCRs apply to all banks, building societies, and large investment firms incorporated in the UK[footnote 7].

Use of the CCYB and SCR tools can enhance the resilience of the financial system in two ways: first, by directly increasing the loss-absorbing capacity of firms, and thereby increasing the resilience of the system to periods of stress; and second, via indirect effects on the amount of financial services supplied by the financial system through the cycle (either through the distribution or overall level of these services), thus reducing the severity of periods of instability.

The FPC also has powers of direction relating to macroprudential tools that are outside the EU framework: the ability to direct the PRA and/or the FCA to set limits on LTV and DTI ratios for owner-occupied mortgages; and the ability to set a leverage ratio framework for UK banks, building societies and PRA-regulated investment firms[footnote 8].

Although the measures contained in this consultation paper may concern the prudential supervision of banks and investment firms, they will not operate within the current formalised EU framework for macroprudential measures.

Therefore it will be important for the FPC to be aware of developments in the EU relating to macroprudential policy, where these impact on the measures contained in this consultation paper.

Accountability

There are a number of ways in which the FPC is held accountable for the exercise of its powers.

FPC policy decisions, including any new directions and/or recommendations, are communicated to those to whom the action falls (e.g. the PRA or FCA). The policy decision is also communicated to the public, either via a short statement in the first and third quarters of the year or via the FSR in the second and fourth quarters.

For each of its powers of direction, the FPC must prepare, publish and maintain a written statement of the general policy that it proposes to follow in relation to the exercise of its power.

The policy statements typically also describe core indicators the FPC will routinely review to help inform its judgements. Furthermore, when making recommendations or directions the FPC must provide an estimate of the benefits and costs, unless it is not reasonably practicable to do so.

A formal record of the FPC’s policy meetings must be published within six weeks of the relevant meeting. It must specify any decisions taken at the meeting and must set out, in relation to each decision, a summary of the FPC’s deliberations.

FPC members also appear regularly before Members of Parliament at Treasury Select Committee (TSC) hearings, where they are required to explain their assessment of risks and policy actions. The TSC has also held confirmation hearings for members.

Furthermore, the Bank of England Act 1998 (as amended by the Financial Services Act 2012) requires that statutory instruments that set out the FPC’s tools in secondary legislation must go through an affirmative legislative procedure. Therefore, both Houses of Parliament must expressly approve any draft orders of macroprudential tools before they can become law.

FPC housing market communications

FPC communications relating to powers of direction in the housing market

In March 2012, the interim FPC made recommendations to the government on the powers of direction that it judged it needed[footnote 9]. The interim FPC recognised the potential benefits of having powers of direction in relation to loan-to-income (LTI) and LTV tools, but at the time did not recommend that the FPC (when permanently established) be granted powers of direction relating to these tools.

The Committee did not perceive the public debate about such tools to be sufficiently advanced at the time, but agreed that powers of direction relating to these tools may be appropriate in the future.

From 2012 to 2014, both in the UK and internationally, there was considerable further public debate of how developments in housing markets may pose risks to financial stability and how best to address such risks.

In his Mansion House speech on 12 June 2014, the Chancellor announced his intention to grant the FPC new powers of direction, including in relation to LTI and LTV ratios, and committed to ensuring that the “Bank of England has all the weapons it needs to guard against risks in the housing market”[footnote 10].

In response to the Chancellor’s announcement, on 2 October 2014, the FPC recommended that it be granted powers of direction in relation to housing market tools in relation to owner-occupied mortgages and buy-to-let residential mortgages[footnote 11].

In April 2015, the government legislated to give the FPC powers of direction over the PRA and the FCA in relation to LTV and DTI limits in respect of owner-occupied mortgage lending. In line with its statutory requirements, the FPC approved and published a policy statement on how it intends to use these powers[footnote 12].

In respect of buy-to-let mortgages, the government stated its intention to consult separately on the recommendations by the end of 2015. This consultation documents fulfils that commitment.

FPC recommendations in relation to owner-occupied mortgage lending

In June 2014, the FPC recommended that the PRA and FCA should ensure that mortgage lenders do not extend more than 15% of new owner-occupier mortgages at LTI multiples at or greater than 4.5[footnote 13].

The FPC also recommended that the FCA should ensure that, when assessing affordability, mortgage lenders have regard to any FPC recommendation on appropriate interest rate stress tests.

The current FPC recommendation is that lenders should apply an interest rate stress test that assesses whether borrowers could still afford their mortgages if, at any point over the first five years of the loan, Bank Rate were to be three percentage points higher than the prevailing rate at origination.

These FPC recommendations were primarily motivated by the Committee’s desire to provide insurance against indirect risks to financial stability arising from household indebtedness.

The FPC closely monitors conditions in UK property markets, and communicates developments in financial stability risks emanating from the housing market through quarterly statements and the bi-annual FSR.

At its policy meeting in September 2015, the FPC judged that the recommendations it made in June 2014 remain warranted[footnote 14].

3. The buy-to-let market

This chapter characterises the buy-to-let market, its relation to the private rented sector, summarises some recent and historical data, and sets out the regulation of the buy-to-let market to date.

The buy-to-let market and the private rented sector

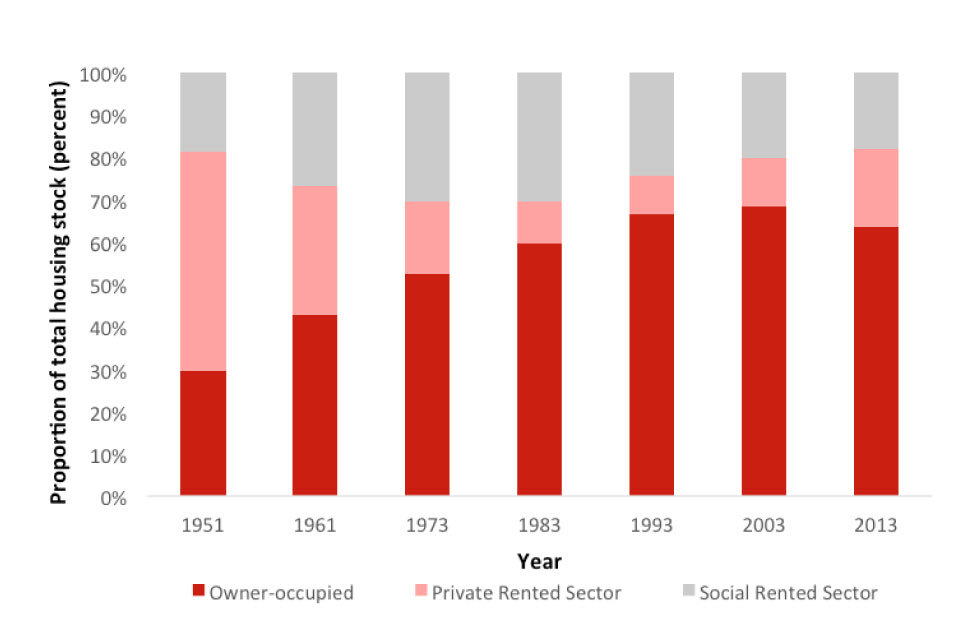

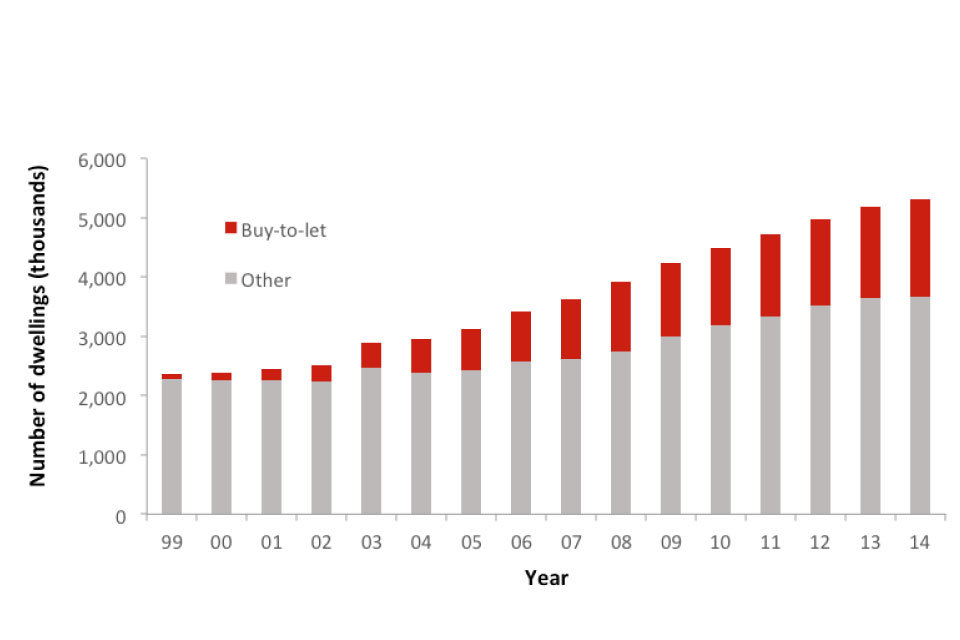

The private rented sector (PRS) has grown rapidly in recent years, from 2.5 million dwellings in 2002 (10% of all dwellings) to 5.2 million dwellings in 2013 (19% of all dwellings).

This growth has been driven in part by structural and demographic factors and in part by higher house prices relative to incomes. This growth is depicted in the light red columns in Chart 3.A.

Chart 3.A: The UK private rented sector has been expanding in the last thirty years

Chart 3A

Source: Department for Communities and Local Government (DCLG); Welsh Assembly government; Scottish government; Department for Social Development (Northern Ireland)

The expansion of groups of the population that tend to rent – such as single households, students, those with low job security and young professionals – combined with the rise in house prices relative to incomes has delayed the age at which potential first-time buyers leave the PRS.

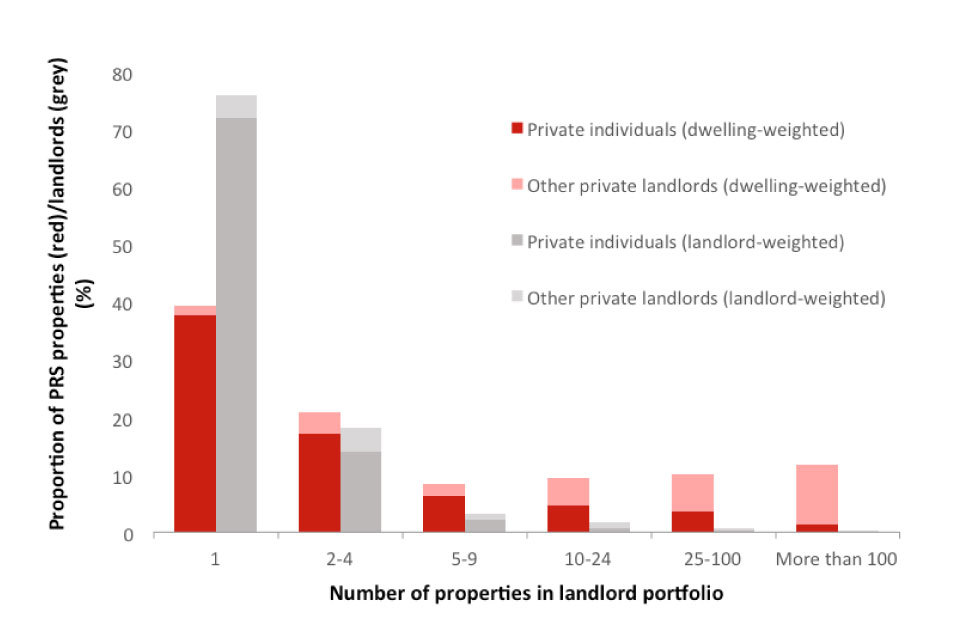

The PRS consists of residential properties which are privately rented but not owned by local authorities or registered social landlords, such as housing associations. Landlords within the PRS include individuals, commercial real estate companies and institutional investors.

Evidence from the Private Landlord Survey provides an indication of the ownership structure of the PRS[footnote 15]. Chart 3.B depicts, by number of properties in private landlords’ portfolios, the proportion of all PRS dwellings within that size of portfolio (the red bars) and the proportion of all private landlords with that size of portfolio (the grey bars). For example, the leftmost red column in Chart 3.B shows that around 40% of PRS dwellings are estimated to belong to private landlords with only one property in their portfolio. The leftmost grey column shows that around 75% of private landlords are estimated to have a portfolio of just one property.

89% of private landlords in the PRS are classified by the survey as ‘private individuals’[footnote 16]. Of these, 97% (or 86% of all private landlords) own fewer than five properties each, accounting for 55% of the PRS[footnote 17]. 81% (or 72% of all private landlords) own just one dwelling each, accounting for 38% of the PRS.

The remaining 11% of private landlords are classified by the survey as either ‘companies’ or as ‘other organisations’, shown in Chart 3.B as ‘other private landlords’. Of these, 16% (or 2% of all private landlords) own ten or more dwellings each, accounting for 22% of the PRS.

In total, 6% of all private landlords own five or more dwellings each, and they account for around 40% of the stock of PRS properties. This feature of the PRS is driven by a small number of private landlords whose portfolios contain a large number of properties: just 0.2% of all private landlords maintain a portfolio of more than 100 dwellings, but those properties account for 11% of the PRS.

Chart 3.B: 94% of private landlords own fewer than five properties, but the remaining 6 percent own 40 percent of the PRS.[footnote 18]

Chart 3B

Source: DCLG Private Landlord Survey 2010 and HM Treasury calculations

The Buy-to-Let Mortgage Market

The buy-to-let sector is a relatively new development within the PRS. A buy-to-let mortgage is a mortgage secured against a residential property that will not be occupied by the owner of that property or a relative, but will instead be occupied on the basis of a rental agreement.

The sector began in earnest in 1996 with the aim of providing loan finance for private landlords at rates much more closely aligned with owner-occupier mortgages. Since 1996, the sector has undergone an expansion, reflecting the structural and demographic trends towards a larger PRS that were noted above.

The expansion of buy-to-let lending is likely to have both supported and been supported by the growth of the PRS: the growth of the PRS provided opportunities for potential buy-to-let borrowers; and the availability of finance via buy-to-let mortgages has aided the expansion of the buy-to-let sector.

However, there are a number of different ways a landlord might finance the purchase of a property in the PRS. Recent estimates suggest that only 50% of purchases of investment properties use a buy-to-let mortgage, and only around 32% of all properties in the PRS are currently backed by a buy-to-let mortgage[footnote 19] [footnote 20].

Conversely, around 68% of properties in the PRS are not backed by a buy-to-let mortgage. These properties are either owned outright or make use of another form of finance, such as a commercial real estate mortgage, an SME loan, or institutional investment.

Chart 3.C: Dwellings associated with a buy-to-let mortgage have grown as a proportion of the PRS in recent years

Chart 3C

Source: HM Government, CML, and HM Treasury calculations

Chart 3.C depicts an estimate of the number of dwellings associated with a buy-to-let mortgage as a proportion of the total number of dwellings in the PRS[footnote 21]. The series ‘Other’ is the difference between the total number of properties in the PRS and the total number of outstanding buy-to-let loans.

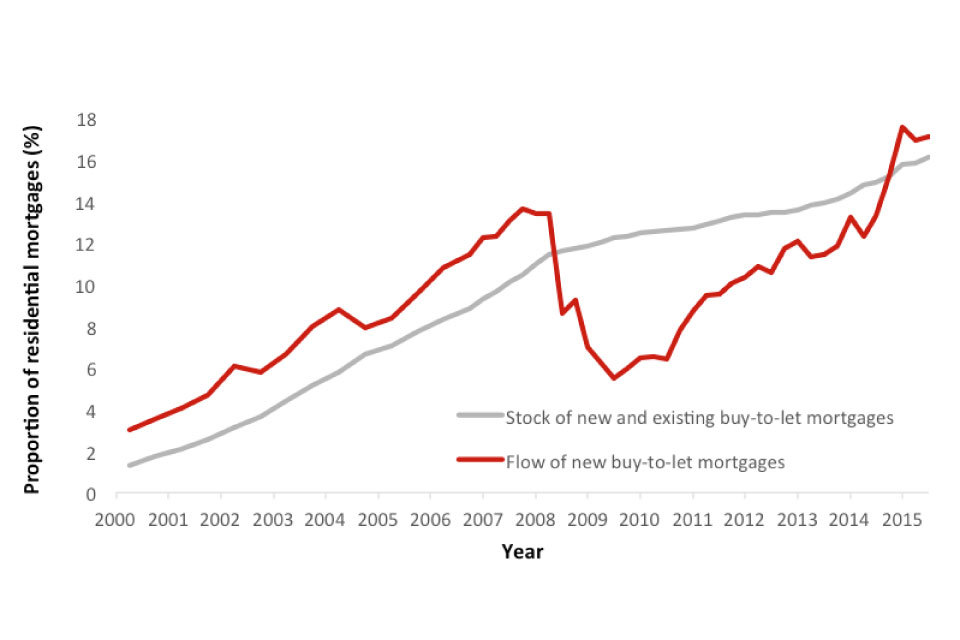

Chart 3.D shows the proportions of new loans (the flow) and of new and existing loans (the stock) that are buy-to-let from 2000 to 2015[footnote 22]. Buy-to-let mortgage lending is now a significant share of both the flow of residential mortgage lending and stock of mortgage lending on lenders’ balance sheets. In June 2015, there were 1.7 million outstanding buy-to-let mortgages. These loans were collectively worth £201 billion, and represented 16% of the total stock of residential mortgage by value. This is up from 12% of the stock in 2008 and 4% of the stock in 2002.

The proportion of the flow of new residential mortgages that are buy-to-let mortgages has also risen over this period: in Q2 2015, by value, 17% of new loans for house purchase were buy-to-let mortgages. This is well above the pre-crisis peak of 14% reached in Q4 2007.

Buy-to-let lending fell more sharply during the financial crisis than lending to owner-occupiers: the flow of new buy-to-let loans declined by over 80 percent from 2007 to 2010, while new owner-occupier loans fell by 60%.

Since 2010, the number of buy-to-let loans has increased, and at a slightly faster rate than owner-occupier loans. However, the number of new buy-to-let loans in 2014 was still 45% below the number of new buy-to-let loans in 2007[footnote 23].

Chart 3.D: The proportion of mortgages that are buy-to-let mortgages (by value in GBP)

Chart 3D

Source: CML

Underwriting standards are an important determinant of housing market cycles. LTV ratios and ICRs are two of the most common metrics used to measure underwriting standards in the buy-to-let market, and LTV and ICR limits are the two tools by reference to which the FPC has requested powers of direction.

An LTV ratio measures the size of the mortgage as a proportion of the value of the property; and ICRs measure the value of expected rental payments as a proportion of mortgage interest payments at a specified interest rate. More information on these metrics and the precise tools requested by the FPC are set out in Chapter 4.

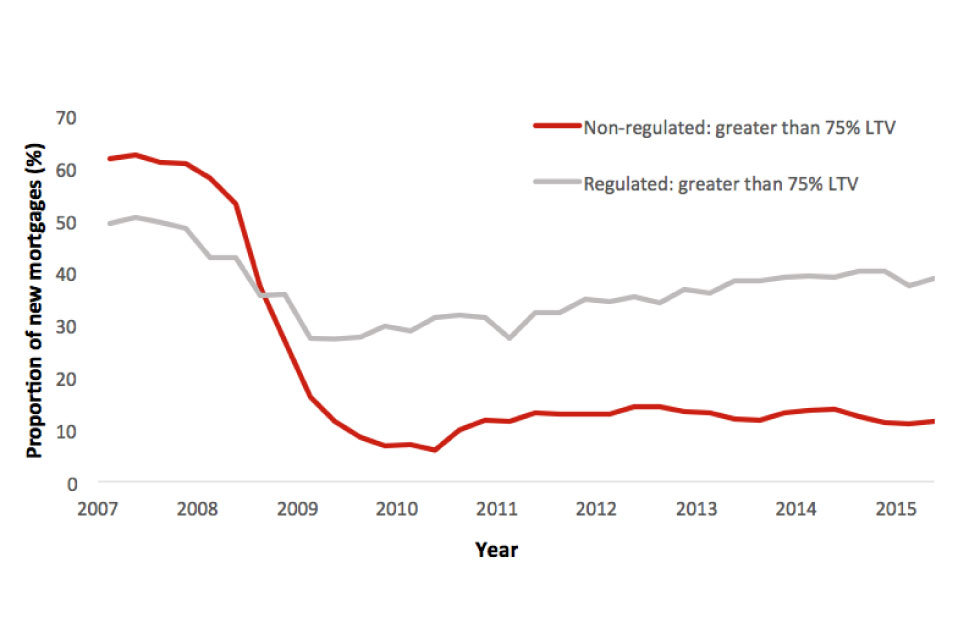

Mortgage Lenders and Administrators Return (MLAR) statistics, compiled and published by the Bank of England and the FCA, provide the share of new ‘non-regulated’ mortgages by LTV ratio. ‘Regulated’ mortgages broadly correspond to owner-occupier mortgages; and ‘non-regulated’ relates predominantly to buy-to-let mortgages[footnote 24]. These data are depicted in Chart 3.E.

In 2015 Q2, around 12% of new non-regulated mortgages had an LTV ratio greater than 75%, broadly in line with the average since late 2010. However, LTV ratios on new loans were higher in 2007 and early 2008, when around 60% of new mortgages were originated at an LTV ratio greater than 75%.

By way of comparison, the corresponding figure for owner-occupier mortgages was 39% in 2015 Q2, and this has been trending slowly upwards since 2009. In 2007 and early 2008, around 50% of new regulated mortgages were offered at LTV ratios above 75%[footnote 25].

Chart 3.E: The evolution of loan-to-value ratios on regulated and non-regulated mortgages since 2007

Chart 3E

Source: Mortgage Lender and Administrators Return statistics

There are no aggregated datasets depicting the evolution of ICRs over time. However, it is common practice for lenders to require that the monthly rental income on the property be at least 125% of monthly mortgage interest payments, based on the higher of a ‘stressed’ interest rate – usually around 5-6% – or the actual, or reversionary, interest rate on the mortgage product.

Remortgaging activity constitutes a significant portion of buy-to-let lending flows. In 2015 Q2, remortgaging accounted for 52% of gross buy-to-let lending flows by volume and 51% by value, up from around 38% by value and 36% by volume in 2009 Q4[footnote 26].

A wide range of lenders currently offer buy-to-let mortgages. This includes major UK banks and building societies, small and medium sized building societies, newly established banks, and specialist lenders. Regulatory data suggest that the five largest lenders accounted for over 85% of gross buy-to-let lending in 2010, but less than 65% of gross buy-to-let lending in the first two quarters of 2015[footnote 27]. Market intelligence from the Bank of England suggests that almost all buy-to-let lending takes place through intermediaries.

The vast majority of buy-to-let mortgages are interest-only, which means that they do not amortise. As a result, the share of lenders’ mortgage portfolios that they represent grows faster than their share in the flow might suggest. In 2015 Q2, 85% of new buy-to-let mortgages were interest-only, up from 77% in 2007 Q1[footnote 28]. This reflects the nature of the majority of buy-to-let mortgages as the carrying-on of a business activity.

Buy-to-let regulation to date

When mortgage regulation was introduced in 2004 under the Financial Services and Markets Act (FSMA), it drew a distinction between mortgage lending to owner-occupiers and mortgage lending to buy-to-let landlords.

It implemented this distinction by setting out in legislation that, for a mortgage to be conduct regulated, at least 40% of the property must be occupied, or intended to be occupied, by the mortgage borrower or their relative. This ensured that buy-to-let landlords, unless taking out a mortgage that met the definition of a regulated mortgage contract, were not brought within the scope of regulation[footnote 29].

This approach is driven by two considerations. The first is that an owner-occupier’s own home is at risk, so there are potentially significant social implications if such borrowers are not adequately protected. The second, in turn, is that buy-to-let borrowers tend to be acting as a business.

More generally, this approach is a manifestation of the government’s intention only to introduce FCA regulation where there is a clear case for doing so, in order to avoid putting additional costs on firms. Businesses are expected to be better placed than consumers to judge whether or not contracts they make with other businesses are in their interest.

This approach has meant that the vast majority of the buy-to-let market is not subject to conduct regulation. However, from March 2016, a limited framework of conduct regulation for consumer buy-to-let activity will be introduced as a consequence of implementing the EU Mortgage Credit Directive in the UK[footnote 30].

This regime will be targeted at the small proportion of buy-to-let transactions where borrowers do not seem to be acting as a business. For example, the property may have been inherited, or the borrower, having previously lived in the property but being unable to sell it, resorts to a buy-to-let arrangement.

Under this regime, firms will have to register with the FCA and comply with a number of conduct standards set out in the government’s legislation, including conducting a creditworthiness assessment for each buy-to-let mortgage.

The government’s best estimate is that this new regime will capture around 11% of current buy-to-let transactions[footnote 31]. This ensures that the majority of the buy-to-let market remains outside of the scope of conduct regulation[footnote 32].

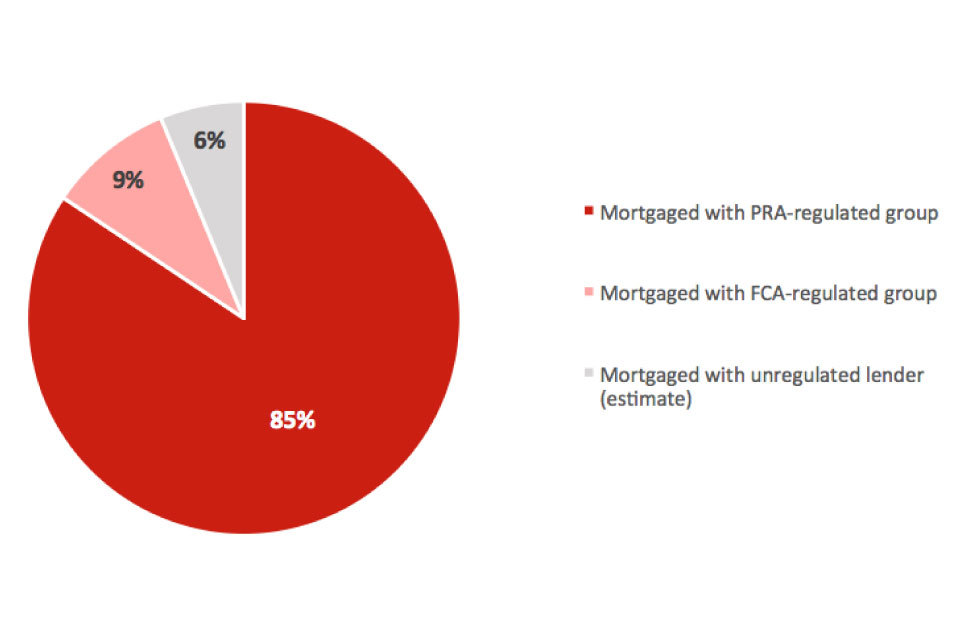

Chart 3.F: Regulatory coverage of buy-to-let mortgages

Chart 3F

Source: PRA, FCA and HM Treasury calculations

In terms of prudential regulation, most lenders that offer buy-to-let mortgages are subject to prudential oversight. Although a lender does not need to be authorised to offer buy-to-let mortgages, most lenders that offer buy-to-let mortgages are also engaged in a regulated activity, such as offering regulated mortgages.

Taken together, this means that the vast majority of buy-to-let mortgages are with groups regulated by either the PRA or the FCA. Chart 3.F depicts the regulatory coverage of buy-to-let mortgages by regulated group.

Outside of conduct and prudential regulation, there are also industy-led initiatives. Recently, the Council of Mortgage Lenders (CML) have issued a statement of practice to guide lenders, intermediaries and landlords. It outlines the overarching principles of CML members’ general approach to buy-to-let, including the sale and administration of buy-to-let mortgages excluded from the regulatory scope of the FCA.

It is intended to ensure that buy-to-let borrowers understand their lender’s responsibilities as well as their own, and sets out information customers can expect to be provided with by the lender, either directly or via an intermediary[footnote 33].

In the Summer Budget of 2015, the government acted to restrict, to the basic rate of income tax, the tax relief on finance costs received by landlords of residential property. The restriction will be phased in over four years, starting from April 2017. This will reduce the distorting effect the tax treatment of property has on investment and mean individual landlords are not treated differently based on the rate of income tax that they pay[footnote 34].

In the 2015 Autumn Statement, the Chancellor announced a 3 percentage point increase in the rates of Stamp Duty Land Tax applying to the purchase of additional residential properties, such as second homes and buy-to-let properties. This will take effect from 1 April 2016 and is part of the government’s commitment to supporting homeownership and first-time buyers[footnote 35].

In December 2015, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) released a consultative document on ‘Revisions to the Standardised Approach for credit risk’.

These proposals differ in several ways from an initial set of proposals published by the BCBS in December 2014. Of interest to the buy-to-let market, the updated proposals include the potential application of “higher risk weights to real estate exposures where repayment is materially dependent on the cash flows generated by the property securing the exposure”.

The government encourages interested parties to respond directly to that consultation should they have any comments or concerns about the proposals.

An updated impact assessment will be produced following this consultation and will take into account any changes in the buy-to-let regulatory framework.

4. Buy-to-let lending and financial stability

This chapter presents an assessment of how buy-to-let lending may carry risks to financial stability, the specific tools requested by the FPC, issues relating to regulatory coverage and the scope for regulatory leakage, and other definitional details relating to the draft Statutory Instrument.

The main channels through which the buy-to-let market may carry risks to financial stability are credit risk, the risk of amplification of the house price cycle, and the possible interaction of high indebtedness with these two channels[footnote 36].

Credit risk

The first channel through which buy-to-let lending could pose a risk to UK financial stability is through credit risk. This risk stems from the adverse impact that losses arising from buy-to-let lending can have on lender balance sheets and, in turn, on the resilience of the financial system.

Mortgages are the single largest asset class on UK banks’ balance sheets. Distress in this market could impact banks’ capital, impair their access to finance and reduce their ability to provide core services to the economy.

A reduction in house prices would reduce the value of the collateral available to banks and increase their risk of losses on mortgage assets.

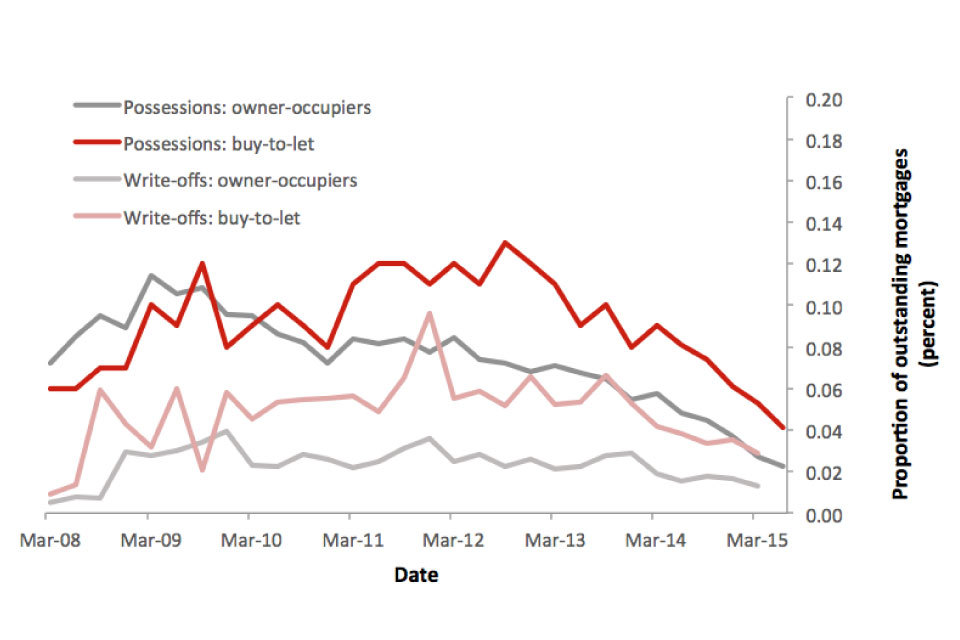

Chart 4.A: Write-off rates and possession rates on residential mortgage lending

Chart 4A

Source: MLAR, CML

Evidence suggests that credit risk on individual buy-to-let loans is higher than for owner-occupier mortgages. As depicted in Chart 4.A, data from the MLAR and the CML suggest that write-offs and possession rates on buy-to-let loans have been around double that of owner-occupier mortgages since 2011[footnote 37].

Loan-level analysis from the Central Bank of Ireland (CBI) on UK mortgages found that in the 2009-13 period the probability of default for buy-to-let mortgages was 36 percent higher than for owner-occupier mortgages[footnote 38].

The stock of buy-to-let lending may be particularly vulnerable to very large falls in house prices. This is because buy-to-let loans are typically extended on interest-only terms, and therefore do not amortise. As a result, loan-to-value ratios on buy-to-let loans are likely to fall slowly over time.

Furthermore, the prevalence of floating, or relatively short-term fixed, mortgage rates for these non-amortising loans heightens the sensitivity of buy-to-let lending to changes in interest rates. Increasing interest rates can simultaneously increase costs and reduce the value of the property.

This could be a particular concern in a rising interest rate environment: buy-to-let ventures may become unprofitable given higher debt-servicing costs; and affordability tends to be tested at lower stressed interest rates than owner-occupied lending.

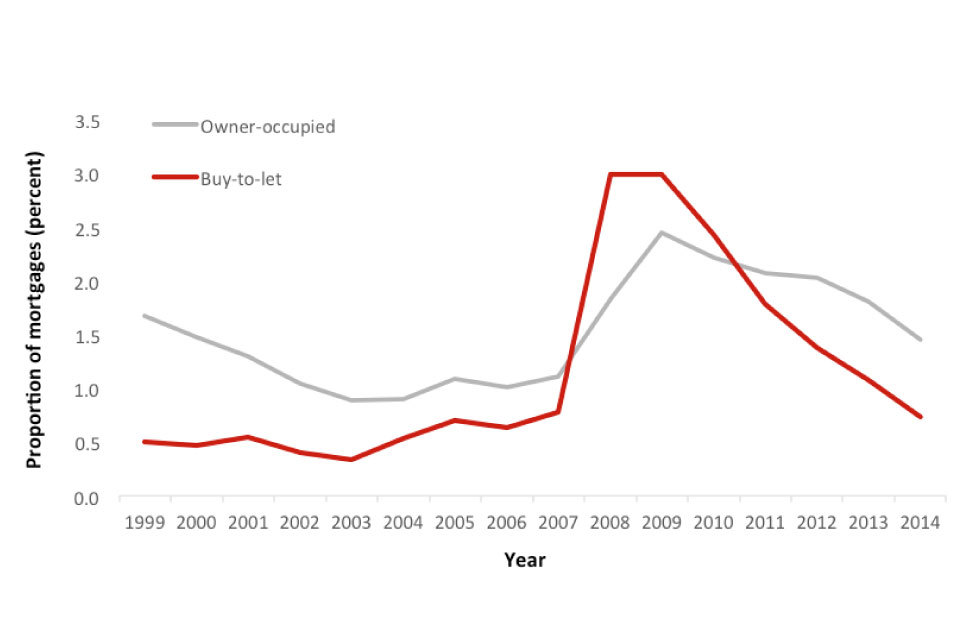

Mortgage arrears are sensitive to shocks in the economy, particularly from shocks to unemployment and interest rates. As shown in Chart 4.B, between 2000 and 2007 the number of buy-to-let mortgages in arrears for three months or more was low and broadly stable, at around 0.5 percent.

Over this period, the proportion of owner-occupied mortgages in arrears was higher, between 1% and 1.5%.

This picture reversed during the financial crisis, when the proportion of buy-to-let mortgages in arrears rose sharply and peaked at 3%. Contemporaneously, there was a similar though smaller increase in the proportion of owner-occupier mortgages in arrears, peaking at 2.5%.

Chart 4.B: Arrears on buy-to-let and owner-occupier residential mortgages since 1999

Chart 4B

Source: CML

Mortgage arrears have fallen steadily since 2009. The proportion of buy-to-let mortgages in arrears is now just above pre-recession levels. In 2014, the proportion is half that of the proportion of owner-occupied mortgages in arrears, at 0.7% compared to 1.5%.

The scale of the credit risk from the buy-to-let sector in aggregate, and the associated threat to financial stability, is partially mitigated by the size of the sector. However, this threat is likely to increase as the sector grows.

This is a particular concern for financial stability if that growth is accompanied by a deterioration in underwriting standards. As noted in Chapter 3, the outstanding stock of buy-to-let lending has increased by 40% since 2008, and has accounted for 80% of the increase in the stock of secured lending to individuals.

Amplification of housing market cycles

Buy-to-let lending may also have the potential to amplify housing market cycles, both in the upturn and in the downturn. Housing is the main source of collateral for the real economy, and so can give rise to a self-reinforcing loop of rising house prices and overextension of credit growth.

This amplification could generate indirect costs on the wider economy and increase financial stability risks.

In an environment of rising house prices, buy-to-let borrowers seeking capital gains may have incentives to enter the market. Since buy-to-let borrowers and owner-occupiers operate within a single housing market, any increase in demand associated with buy-to-let borrowers would put upward pressure on house prices for both owner-occupiers and buy-to-let borrowers.

Rising prices in an upswing could result in greater financial stability risks if it resulted in all mortgage borrowers taking on larger loans. The FPC’s recommendation on LTI flow limits provides some insurance against the increased indebtedness of owner-occupiers in this scenario, but it would result in more owner-occupiers being excluded from the market.

In an environment of falling house prices, buy-to-let borrowers could exacerbate the scale of house price falls if they choose to exit from the market and sell their investments. This risk may be particularly acute in an environment of rising interest rates, especially among highly-indebted buy-to-let borrowers who are vulnerable to interest rate rises.

Survey evidence suggests that around 40 percent of buy-to-let borrowers would respond to their rental income falling below their interest payments by seeking to sell their property[footnote 39].

House price falls may also result in a reduction in consumption. This is because a decrease in housing equity may limit the ability of households to borrow to finance spending.

This impact on consumption may pose indirect risks to financial stability through the impact on the wider economy and, in turn, the increase in credit risk from other assets on lenders’ balance sheets.

Larger house price falls may also amplify financial stability risks through the credit risk channel for both buy-to-let and owner-occupier borrowers. This is because a large house price fall would increase incentives for borrowers to default, increasing lenders’ potential losses.

Question 4.a:

Do respondents agree with the assessment that the buy-to-let market may carry risks to financial stability?

Question 4.b:

If yes, do respondents believe that these are the channels through which the buy-to-let market carries risk? If no, why?

Tools Requested by the FPC

As noted in Chapter 1, the FPC has recommended that it be granted the power, if necessary to protect and enhance financial stability, to direct the PRA and FCA to require regulated lenders to place limits on buy-to-let mortgage lending by reference to:

- Loan-to-Value (LTV) Ratios; and

- Interest Coverage Ratios (ICRs).

The FPC has previously noted that powers of direction have several benefits over powers of recommendation[footnote 40]:

Firstly, the implementation of directions may be more timely than for recommendations. This is important because delayed implementation may lead to the bringing forward of the activity to which the direction relates. Moreover, as the FPC notes, there may be circumstances where tensions arise between the preferred policy actions of microprudential and macroprudential regulators.

For example, in a downturn the macroprudential authority might judge that loosening regulatory requirements could help to protect and enhance the resilience of the financial system as a whole, whereas the microprudential regulator may place more weight on maintaining standards to protect individual firms.

Secondly, powers of direction allow for greater accountability and policy predictability than recommendations. In addition to the duty to explain how a policy action will help the FPC meet both its objectives, which applies to recommendations and directions, the FPC is required to produce and maintain a statement of policy for each of its direction powers.

These statements set out how the tools are defined, the likely impact the tools are expected to have on lenders’ resilience and the wider economy, and in what situations the FPC would expect to use the power.

The FPC is expected to provide, as part of the statement, a list of key indicators that it will consider when judging if policy action using the tool in question is appropriate. Ex-ante explanations of this depth are not possible or practical for the FPC’s recommendation power because of its breadth.

The information contained within the policy statement will help market participants discern the FPC’s policy reaction function and serve as useful context when the FPC is held to account for its actions after the fact.

The FPC are also required to produce an estimate of the costs and benefits that would arise from compliance with any given direction unless the FPC believe it is not reasonably practicable to do so.

However, there are potential benefits from prescribing a set of tools which is proportionate to the threat being posed. This means a set of tools whose role and effects can be more clearly defined which avoids undue complexity, and also helps to ensure public accountability and communication.

By maintaining simplicity and clarity of the macroprudential framework, the FPC would be more likely to convey a clear reaction function (i.e. improve predictability of its actions) which would help shape expectations of future FPC actions.

The FPC has stated that a power of direction to limit high LTV lending and low ICR lending must also be available to be applied to buy-to-let lending extended by regulated entities. This would prevent the FPC from having to apply a relatively tighter policy stance on owner-occupied lending alone in order to achieve the same impact.

Finally, it is important to note that the FPC has made clear that its aim in using these tools is not to control house prices. Rather, it is to mitigate the risks that a cycle of rising house prices and overextension of credit can pose to financial and macroeconomic stability.

LTV limit

An LTV ratio for a new mortgage is calculated as the ratio of mortgage value to property value at origination.

An LTV portfolio limit specifies that, over a given period of time, no more than a specified proportion of the flow of new mortgage originations by a given lender can have an LTV at origination above a certain level. The proportion of new mortgages is calculated on either a values or volumes basis.

The limit acts by setting the minimum size of deposit (or equity in an existing property) that a borrower must pledge in order to buy a property (or remortgage). For example, a 75% LTV limit would require the borrower to have a deposit of at least 25%.

If the specified proportion is set to zero then the tool operates as a hard cap – all mortgages with LTV ratios above a certain level at origination are prohibited. If the specified proportion is set at above zero this allows for some lending above the threshold to be extended.

ICR limit

Given the importance of rental income in determining the ability of buy-to-let landlords to service their debt, a widespread practice in the buy-to-let lending market is to use the mortgage’s interest coverage ratio (ICR) in assessing affordability.

A buy-to-let mortgage’s ICR is defined as the ratio of the expected rental income from the buy-to-let property to the expected mortgage interest payments (assuming an appropriate interest rate) over a given time period.

For example, a number of lenders currently require that rental income must be at least 125% of mortgage interest payments when using an interest rate of 5% – although this practice is not universal. The minimum ICR in this example is 1.25, or 125%.

As noted in the FPC’s policy statement of 2 October 2014, in order to take rental income into account and reflect prevailing market underwriting practices, the FPC agreed that for the buy-to-let sector it would be appropriate to include a power of direction relating to the extent of lending by ICR extended by regulated entities.

An ICR portfolio limit specifies that, over a given period of time, no more than a specified proportion of the flow of new mortgage originations by a given lender can have an ICR at origination below a certain level.

The proportion of new mortgages is calculated on either a values or volumes basis. The FPC would also be able to specify the appropriate interest rate to consider when calculating the ratio.

How LTV and ICR tools mitigate risks to financial stability

LTV and ICR limits could reduce potential financial stability risks through both the credit risk and amplification channels outlined above. If the FPC were to issue a direction that was binding in the market, it is likely that the tools would act to reduce the supply of credit.

The scenario analysis in the impact assessment examines the sensitivities around the impact of an effective supply reduction.

In relation to credit risk from buy-to-let mortgages, LTV and ICR limits could reduce both the probability of default and the loss given default on individual mortgages.

The CBI study found a relationship between LTV ratios and the probability of default[footnote 41]. For all UK mortgages, a one percentage point increase in the LTV ratio leads to a one percent increase in the probability of default. The study also found that this relationship is considerably stronger for buy-to-let loans than for loans to owner-occupiers.

Data collected for the Bank of England’s supervisory function also provides evidence of this link[footnote 42]. At end-2014, 4 percent of buy-to-let mortgages of the six largest mortgage lenders with a current LTV above 80% were in arrears of more than three months’ payments, compared to 0.6 percent of mortgages with LTV less than 80%.

An LTV limit acts by directly limiting the exposure of individual lenders and the system as a whole to credit risk from higher LTV lending, reducing the total number of defaults. The use of an LTV limit could also reduce total losses for a given number of defaults.

An ICR limit helps to reduce the likelihood of a borrower needing to draw on other income sources to meet mortgage repayments if interests rates rise, maintenance costs increase, or rental income falls.

This should reduce the likelihood that a buy-to-let borrower falls into arrears or defaults on their loan. Data collected for the Bank’s supervisory function suggests that arrears rates are higher for buy-to-let mortgages with lower ICRs[footnote 43].

LTV and ICR limits could also reduce the scale of the amplification channel. As noted above, during an upswing in the housing market, buy-to-let borrowers can take advantage of capital gains to extract equity and expand their portfolios, which has the potential to boost house prices.

Research from the United States and Ireland provides evidence for this dynamic. Haughwout et al found that US states that saw bigger booms and busts in house prices tended to have bigger, and faster growing, shares of borrowers in the housing market[footnote 44].

Research by the CBI finds that the share of buy-to-let borrowers in the market is positively correlated with a measure of house price overvaluation[footnote 45]. House price overvaluation may lead to an unsustainable increase in household indebtedness by all mortgagors.

This can compromise their ability to pay their mortgage and maintain their spending in the face of a shock, which is a risk to economic activity and, in turn, to financial stability.

By linking the maximum amount a potential buy-to-let landlord can borrow on a property to the rental income that property generates, a minimum ICR limit may help protect against amplification in an upswing, particularly if prices rise much faster than rents.

By protecting against the likelihood that the buy-to-let landlord experiences an operating loss, imposing ICR limits may reduce the likelihood of buy-to-let landlords exiting the market and thus exacerbating a housing market down turn.

An LTV limit would mitigate risks from the amplification of the housing cycle by reducing the amount of equity borrowers can withdraw when remortgaging and the size of the investment they can make with that equity.

The benefits of an LTV tool are further supported by international experience. LTV limits are the most common form of macroprudential tool used to mitigate risk in the housing market.

In the countries that currently employ LTV limits, buy-to-let mortgages tend to receive the same treatment as owner-occupier mortgages. Two exceptions to this rule are New Zealand and Ireland, which arguably have buy-to-let sectors very similar to the UK (that is, featuring a large number of landlords with few properties). In these two countries, LTV limits are tighter in the buy-to-let market.

In 2015, the CBI announced that only 10 percent of new buy-to-let mortgages should exceed an LTV ratio of 70%[footnote 46]. This compares to equivalent LTV limits of 90% for first-time buyer loans, and 80% for home-mover loans.

Similarly, also in 2015, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ) announced new regional LTV restrictions due to the accumulation of housing market risk in Auckland[footnote 47].

This stated that a maximum of 5 percent of new buy-to-let mortgages should exceed an LTV ratio of 70%, compared to a maximum of 10 percent of loans to owner-occupiers above an LTV ratio of 80%.

Question 4.c:

Do respondents think that the powers requested by the FPC relating to LTV ratio limits and ICR limits would be effective in addressing any risks posed to financial stability from the buy-to-let market? If not, why?

Question 4.d:

Do respondents agree that the FPC should be granted powers of direction over LTV ratio limits and ICR limits? If not, why?

Question 4.e:

Are there any alternative options for addressing risks posed to financial stability from the buy-to-let market that the government should consider?

Regulatory Leakage and Coverage

The FPC’s proposed powers of direction relating to tools in the buy-to-let market would apply to buy-to-let lending carried out by lenders regulated by the PRA and the FCA under the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000. Depending on the nature of the direction applied, regulatory leakage could occur in two ways:

Firstly, mortgage activity could move to lenders regulated by neither the PRA nor the FCA. The PRA estimate that lenders regulated by the PRA and/or the FCA account for approximately 94 percent of buy-to-let mortgage balances.

The remaining 6 percent of buy-to-let mortgage balances are provided by lenders that are neither regulated by the FCA or PRA. If the powers of direction were binding in the market, mortgage activity could move from PRA- or FCA-regulated lenders to lenders outside the scope of PRA or FCA regulation.

Secondly, PRA/FCA regulated lenders could reclassify borrowers to their corporate or corporate real estate portfolios, depending on the nature of the policy introduced. The capital treatment of corporate and commercial real estate lending may act as a disincentive for such a reclassification because risk weights applied to corporate and corporate real estate loans tend to be higher than for retail buy-to-let loans.

Finally, since the direct transmission of risks from the buy-to-let market to financial stability are similar to those for owner-occupier mortgages, leaving buy-to-let outside the scope of the FPC’s powers of direction could allow significant leakage when attempting to address household indebtedness issues in the owner-occupied mortgage market.

Other legal and definitional issues

There are a number of other legal and definitional issues relating to the granting of these powers to the FPC. The government is keen to ensure that respondents’ views on these issues are fully reflected in the detail of the statutory instrument.

Definition of buy-to-let mortgages to which the tools would apply

The government believes that regulation should only be brought to bear in areas where there is a clear case for doing so, and is aware that buy-to-let lending can be used to finance a number of different activities.

In defining the buy-to-let lending to which the FPC’s tools will apply, the draft legislation attempts to strike the right balance between capturing buy-to-let lending that may pose a risk to financial stability and not inadvertently capturing buy-to-let lending that may finance, or help to finance, other types of activity in the housing market. An example of that other activity might be the construction of new-build housing.

In order to avoid any unintended consequences of capturing those other activities, the draft legislation includes a provision for the exclusion of certain types of buy-to-let lending.

As currently drafted, the instrument excludes buy-to-let lending related to the construction of new buildings, to be used as dwellings, on land on which there were previously no dwellings. That is to say, new-build housing.

The government intends to ensure that the boundary between included and excluded buy-to-let lending is as accurate as it can be. The consultation responses will be used to build an evidence base and justification for the definitions of buy-to-let lending and the exclusions in the final legislation.

If the definition of a buy-to-let mortgage is not inclusive enough or, over time, other types of buy-to-let lending emerge that are not captured by the legislation, the FPC has the power to make a recommendation to HM Treasury that it widen the scope of either the tool or of the regulatory perimeter.

Question 4.f:

Do respondents agree with the definition and scope of buy-to-let lending for the purpose of the FPC’s powers of direction? If not, why?

Question 4.g:

Should any activities associated with buy-to-let lending be excluded from that definition (including the current exclusion of new-build housing)? If so, why?

Scope and application of the tools

The FPC will have the flexibility to give directions to either or both the PRA and FCA, and specify any thresholds above or below which the direction will apply. Therefore, the draft legislation does not set an ex-ante de minimis level, given that this will depend on the specific circumstances in which the FPC issues a direction.

It will be important that the FPC, in issuing a direction, considers which exemptions, if any, may be appropriate. This is to take account of any implications for the proportionality of its actions, in line with its statutory requirements.

The FPC will be able to apply either tool to a proportion of new mortgages calculated on either a values or volumes basis. Depending on the nature of the risk to financial stability that the FPC seeks to address, a values or volumes limit on new lending may be more appropriate.

For example, if there is a financial stability concern over the risk to lenders’ balance sheets, a values measure may be used. If the FPC is concerned about the number of borrowers with high LTV or low ICR mortgages, or the number that are highly indebted, they may exercise the tools on a volumes basis.

Re-mortgages would only be in scope of the FPC’s tools if there is an increase in principal. The LTV ratio and ICR limits would not apply in respect of new lending where there is no increase in principal and where reasonable fees or other costs are rolled into the re-mortgage.

However, the government believes that re-mortgages with an increase in principal should be in scope of LTV ratio and ICR limits given that this would constitute an increase in indebtedness. Further advances on existing mortgages would also be in scope.

The direction can only apply in respect of PRA- and FCA-authorised firms. PRA and FCA rules can also extend to unregulated activities of authorised firms.

Question 4.h:

Do respondents agree that the FPC should be able to apply LTV and ICR limits to a proportion of new mortgages calculated on either a value or volumes basis? If not, please explain on which basis the tools should apply and why.

Question 4.i:

Do respondents agree with the government’s proposed approach in relation to re-mortgages and further advances on existing mortgages? If not, please describe an approach that would be more suitable.

Procedural requirements when implementing directions

When the PRA or FCA take action to implement a direction from the FPC, any procedural requirements that are applicable under the Financial Services and Markets Act (FSMA) 2000 would normally apply.

For example, if the regulator makes rules to implement an FPC direction, it would be required to undertake consultation on those rules, including a cost-benefit analysis.

In some cases, the FPC’s actions will need to be implemented quickly in order to be fully effective. Any delay by the regulator, such as needing to undertake a consultation, could hamper the effectiveness of the tools and increase financial instability.

In urgent cases, both the PRA and FCA have the ability to waive consultation requirements in order to take action quickly.

In the case of the PRA, consultation requirements can be waived where a delay would be prejudicial to the safety and soundness of the firms it regulates. In the case of the FCA, the test is that a delay would be prejudicial to consumers.

It is clear that, where a delay in implementing an FPC direction could lead to severe financial instability, both firms and consumers would be worse off.

In addition, as the FPC noted in its October 2014 statement on housing tools, when creating macroprudential tools in secondary legislation, the government is able to modify or exclude any procedural requirements that would otherwise apply under FSMA 2000 on a tool-by-tool basis.

The FPC noted in this context the risk that lenders and borrowers might bring forward transactions to avoid incoming requirements.

The government acknowledges that the FPC and the regulators may need to act quickly to respond to risks to financial stability arising from the housing market. However, the use of such powers can have a significant impact on the availability of credit for borrowers and the distribution of credit across different sections of society.

There may also be other operational considerations for lenders and regulators. The government believes that the potential impact of the tools justifies retaining the requirements for the regulators to consider the effects of their actions and consult on them.

The government therefore proposes to take the following approach to procedural requirements in the legislation granting the FPC a power of direction over housing tools:

On the first application of any PRA/FCA rules following an FPC direction, the PRA/FCA must carry out all procedural requirements (e.g. a consultation and cost-benefit analysis).

Where the FPC subsequently revokes and replaces a direction by changing the calibration, the government proposes to waive the requirement on the PRA and FCA to consult, but to retain the requirement to carry out a cost-benefit analysis.

The government judges this to be necessary because changes to the calibration of housing tools could have a very broad impact and specific distributional consequences.

Question 4.j:

Do respondents agree with the government’s proposed approach in relation to procedural requirements? If not, please describe an alternative approach.

Buy-to-let income and debt in the FPC’s owner-occupied housing tools

In the consultation on the FPC’s owner-occupied housing tools in 2014, the government set out its preliminary view of the definition of debt and income for the purposes of calculating the owner-occupied DTI limit.

The government proposed to exclude all existing buy-to-let mortgage debt held by the borrower, and to include buy-to-let income only on an after-cost basis. That is to say, rental income over and above buy-to-let mortgage payments.

The government stated in that document that it would revisit in its consultation on the FPC’s buy-to-let recommendations how, if at all, a borrower’s existing buy-to-let mortgage debts, and their income from their buy-to-let mortgage portfolio, should be taken into account in applying a DTI limit on owner-occupied mortgages.

The government believes that its preliminary view remains appropriate, and does not propose any alterations to the existing calculation of DTI limits.

Question 4.k:

Do respondents agree that the government’s approach to buy-to-let debt and income in relation to the FPC’s owner-occupier housing tools remains appropriate?

5. Draft Statutory Instrument

This chapter contains a draft of the order that would be used to grant the FPC powers of direction relating to LTV limits and ICR limits in respect of buy-to-let mortgages, in the event that the powers are granted to the FPC.

Question 5.a:

Do respondents have any comments on the draft Statutory Instrument?

6. Consultation stage impact assessment

This chapter contains the consultation stage impact assessment of granting the FPC powers of direction relating to LTV limits and ICR limits in respect of buy-to-let mortgages.

Question 6.a:

Do respondents have comments on the analysis in this impact assessment?

Question 6.b:

Do respondents have views on the assumptions underpinning this impact assessment?

Question 6.c:

Do respondents have comments on the impact on small and micro businesses in this impact assessment?

Question 6.d:

Do respondents agree with the estimates of the costs of data collection?

7. Summary of Questions

Question 4.a:

Do respondents agree with the assessment that the buy-to-let market may carry risks to financial stability?

Question 4.b:

If yes, do respondents believe that these are the channels through which the buy-to-let market carries risk? If no, why?

Question 4.c:

Do respondents think that the powers requested by the FPC relating to LTV ratio limits and ICR limits would be effective in addressing any risks posed to financial stability from the buy-to-let market? If not, why?

Question 4.d:

Do respondents agree that the FPC should be granted powers of direction over LTV ratio limits and ICR limits? If not, why?

Question 4.e:

Are there any alternative options for addressing risks posed to financial stability from the buy-to-let market that the government should consider?

Question 4.f:

Do respondents agree with the definition and scope of buy-to-let lending for the purpose of the FPC’s powers of direction? If not, why?

Question 4.g:

Should any activities associated with buy-to-let lending be excluded from that definition (including the current exclusion of new-build housing)? If so, why?

Question 4.h:

Do respondents agree that the FPC should be able to apply LTV and ICR limits to a proportion of new mortgages calculated on either a value or volumes basis? If not, please explain on which basis the tools should apply and why.

Question 4.i:

Do respondents agree with the government’s proposed approach in relation to re-mortgages and further advances on existing mortgages? If not, please describe an approach that would be more suitable.

Question 4.j:

Do respondents agree with the government’s proposed approach in relation to procedural requirements? If not, please describe an appropriate approach.

Question 4.k:

Do respondents agree that the government’s approach to buy-to-let debt and income in relation to the FPC’s owner-occupier housing tools remains appropriate?

Question 5.a:

Do respondents have any comments on the draft statutory instrument?

Question 6.a:

Do respondents have comments on the analysis in this impact assessment?

Question 6.b:

Do respondents have views on the assumptions underpinning this impact assessment?

Question 6.c:

Do respondents have comments on the impact on small and micro businesses in this impact assessment?

Question 6.d:

Do respondents agree with the estimates of the costs of data collection?

-

The structure of the FPC and its objectives are set out in Part 1A of the Bank of England Act 1998 (as amended by the Financial Services Act 2012). ↩

-

Minouche Shafik is currently serving on the FPC in an unofficial capacity, but will become a voting member once her Deputy Governor post has been added to statute. ↩

-

As set out in section 9Q of the Bank of England Act 1998 (as amended by the Financial Services Act 2012). ↩

-

As set out in section 9P of the Bank of England Act 1998 (as amended by the Financial Services Act 2012). ↩

-

CRD IV required that EU member states specify an authority responsible for setting the CCyB rate for the UK. HM Treasury designated the Bank of England as that authority. Within the Bank of England, the FPC is the committee that is required, by HM Treasury’s Regulations, to assess and set the CCyB rate for the UK. ↩

-

Investment firms that are not authorised by the PRA have been carved out from the scope of the FPC’s SCR powers by the government; and smaller investment firms which are authorised by the FCA have been exempted from the CCB. ↩

-

Financial Policy Committee Statement from its policy meeting, 16 March 2012 ↩

-

Financial Policy Committee statement from its policy meeting, 26 September 2014](http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/Pages/news/2014/080.aspx) ↩

-

An LTI limit applies to the ratio of the mortgage loan to the applicant’s gross income at the point of origination. ↩

-

This is shown in the chart as the dark grey columns as a proportion of both dark and light grey columns. ↩

-

The 97 percent is shown in the chart as the sum of the dark grey columns in categories ‘1’ and ‘2-4’, as a proportion of all dark grey columns. The 55 percent corresponds to the dark red bars in those categories, as a proportion of all dark red and light red bars. ↩

-

The category ‘other private landlords’ corresponds to the Private Landlords Survey classifications of ‘companies’ and ‘other organisations’ ↩

-

Staff Working Paper No. 549 “How much do investors pay for houses?” Philippe Bracke September 2015. ↩

-

This estimate is derived from comparing the number of BtL mortgages outstanding with the number of PRS properties. ↩

-

It is possible that this estimate includes a small amount of double counting from second- and third-charge buy-to-let mortgages associated with one property, but this does not alter the qualitative picture. ↩

-

These data are available biannually from 2000 to 2006; and quarterly from 2007 onwards. The data in the chart runs from 2000 H1 to 2015 Q3. ↩

-

Source for paragraphs 3.14-3.17: Council for Mortgage Lenders (CML) ↩

-

Estimates suggest that around 87% of the MLAR non-regulated sample is buy-to-let lending. The other 13% includes some second-charge mortgage lending. ↩

-

Source: CML data ↩

-

Where size is designated according to the value of the institution’s gross lending. ↩

-

The definition of a regulated mortgage contract is due to change with effect from March 2016 ↩

-

The government’s best estimate is that around 86% of the market will remain unregulated from a conduct perspective following the implementation of the Mortgage Credit Directive in March 2016. ↩

-

Summer Budget 2015](https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/summer-budget-2015) ↩

-

Spending Review and Autumn Statement 2015](https://www.gov.uk/government/topical-events/autumn-statement-and-spending-review-2015) ↩

-

The consultation stage impact assessment, included in Chapter 6 of this document, also sets out the risks to financial stability from the buy-to-let market both qualitatively and via quantitative hypothetical scenario analysis. ↩

-

Write-off data is taken from MLAR; possession rates data is taken from the CML. ↩

-

McCann, F, (2014) ‘Modelling default transitions in the UK mortgage market’ Central Bank of Ireland Research Technical Paper 18/RT/14. ↩

-

McCann, F, (2014) ‘Modelling default transitions in the UK mortgage market’ Central Bank of Ireland Research Technical Paper 18/RT/14. ↩

-

The underlying regulatory data from which this fact is calculated is confidential. ↩

-

The underlying regulatory data from which this fact is calculated is confidential. ↩

-

Haughwout, A, Donghoon, L, Tracy, J, van der Klaauw, W, (2011) ‘Real Estate Investors, the Leverage Cycle, and the Housing Market Crisis’, Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports no. 514. ↩

-

Coates, D, Lyndon, R, McCarthy, Y, ‘House price volatility: the role of different buyer types’, Central Bank of Ireland Economic Letter Series, Vol 2015, No.2. ↩

-

Central Bank of Ireland (2015) ‘Information Note: Restrictions on residential mortgage lending’ ↩