Call for evidence to consider the case for a Housing Court: government response

Updated 16 June 2022

Introduction

1. Housing is at the heart of our society[footnote 1]. Everyone needs a safe and secure place to live, whether they own or rent their property. The majority of private rented sector landlords take their responsibilities seriously, provide housing that meets or exceeds required standards and treat their tenants fairly. The vast majority of people who rent will not need to pursue a housing or property dispute in a court of law, but when court action is needed, the courts and tribunals should provide fair and efficient access to justice.

2. This government response summarises the issues and concerns about current court and tribunal processes raised by landlords, tenants and other court users in housing cases. It also sets out an ambitious package of reforms to improve the efficiency of housing cases in the County Courts and the Property Tribunal which provides fairer access to justice and an improved service for all.

3. Currently tenants, landlords and property agents can bring a range of housing issues to the courts or the Property Tribunal to enforce their rights. Users have raised concerns that processes do not always work as effectively and as efficiently as they could. Tenants and landlords experience difficulties in navigating the process of bringing a case to a court of law, and have found that the length of time the process takes can be costly and demanding.

4. In October 2017, the government committed to consult with the judiciary on whether a new, specialist housing court could help to address these concerns. We also wanted to better understand and improve the experience of people using courts and tribunal services in property cases. The government published a call for evidence in November 2018 which received 702 responses, and 3 face-to-face events were held in 2019 to gather further views[footnote 2].

5. The responses to the call for evidence were consistent with the findings of independent research published in 2018, which provided views from courts and tribunal service users on the factors influencing the timescales, ease of use and access for different types of housing cases. The research found that:

-

Although the possession action process worked well in most cases, delays sometimes occurred, primarily due to landlord action (such as mistakes made during the application process) and/or bailiff capacity to enforce possession orders.

-

There are barriers to tenants taking action against landlords, including:

- a lack of knowledge and understanding about the legal options available

- concerns about having to attend court

- limited access to legal advice and support

- worries about the costs of taking legal action

- the limited availability of Legal Aid or pro bono providers, and

- the reluctance of Legal Aid firms to take on cases if they were not confident of recovering costs

6. Action to prepare a government response to this call for evidence was paused in 2020 as resources were diverted to introduce emergency measures to protect renters from the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic[footnote 3]. The work to prepare this government response resumed in summer 2021 and effect of these emergency measures on the court system have been incorporated into this response.

A fairer and more effective rental market for landlords and tenants

7. The package of court reforms we are introducing should be considered alongside the government’s wider ambitions to strengthen pre-court mediation services and redress for landlords and tenants, and the commitments to deliver a fairer and more effective rental market set out in the government’s A fairer private rented sector white paper.

8. We will enhance renters’ security and improve protections for tenants by abolishing Section 21 of the Housing Act 1988, so landlords will always have to provide a reason for ending a tenancy. This is the largest reform of tenancy structures in a generation and will significantly change the way landlords can seek possession through the courts. The ‘accelerated’ process will be removed, but we will consider how to expedite cases where there is a serious risk of harm, for example where the anti-social behaviour ground has been used. We will reform possession grounds so landlords have confidence that they will be able to gain possession of their property promptly if their circumstances change or if their tenants breach the terms of the tenancy. Further detail on the reforms to the tenancy regime is set out in our response to the A new deal for renting consultation.

9. Litigation should always be the last resort, but there are currently insufficient incentives or support for landlords and tenants to resolve housing disputes before action in the courts or tribunals is taken. The white paper also confirms the government’s commitment to mainstream early, effective and efficient dispute resolution in private renting, including through the establishment of an Ombudsman for private landlords.

Conclusions

10. The ability of tenants, landlords and property agents to effectively resolve their disputes in a court of law is a cornerstone of a healthy, well-functioning housing market. And when court action is needed, the courts and tribunals should provide fair and efficient access to justice. Fostering and supporting early engagement and open communication between landlords and tenants is key to our vision of creating a less adversarial and polarised sector. Early dispute resolution will also help to free up time for the courts to deal with only the most serious cases. We expect those cases to progress through the courts more efficiently as a result.

11. Having considered the responses to our 2018 call for evidence, and associated stakeholder engagement, we have concluded that the costs of introducing a new housing court would outweigh the benefits, and that there are more effective and efficient ways to address the issues experienced by court and tribunal users in housing cases. Therefore, the government is implementing a package of wide-ranging reforms including:

- The introduction of an online process for possession claims through the Courts and Tribunal Service Possession Reform Programme. The programme commenced in April 2022 and is expected to be completed in 2023. A new online system will be introduced to simplify the court process for landlords, reducing scope for mistakes which cause delays.

- Reviewing bailiff capacity to free up more time for bailiffs to focus on the enforcement of possession orders. Improvements to bailiff recruitment and retention practices are also being explored.

- Reforming grounds for possession so that they are comprehensive, fair, and efficient for both landlords and tenants.

- Reducing the time taken for first hearings to be listed by the courts in cases of serious anti-social behaviour and in temporary and supported accommodation, subject to Judicial agreement.

- Providing earlier access to legal advice for tenants through the results of the Ministry of Justice’s recent consultation on changes to the Court Desk Duty advice scheme.

- Leasehold reform proposals to close the legal loopholes that force leaseholders to pay unjustified legal costs when bringing cases to the Tribunal.

- Trialling a new system in the First-tier Tribunal (Property Chamber) to streamline how specialist property cases are dealt with.

- The Property Tribunal will have an increasingly vital role to play in the private rented sector. The government will reform the process of proposing and challenging rent increases to make the system more transparent and accessible.

- Strengthening mediation services so that fewer cases result in court action, therefore freeing up time for the courts to deal with the most serious cases.

12. We will continue to work closely with our partners in the Ministry of Justice and in HM Courts and Tribunal Service to deliver these reforms. We will also continue engagement with stakeholders across the private rented sector to refine and implement these reforms to make sure the court system works as efficiently as possible for everyday landlords and renters.

1. Summary of findings and the government response

Summary of call for evidence findings

13. Of the 702 responses to the call for evidence, 29% were from landlords, 24% were responding on behalf of an organisation, 22% categorised themselves as ‘other’, 14% were tenants and 9% were homeowners. Ten members of the judiciary (1% of the total number of respondents) responded to the consultation[footnote 4].

14. Three stakeholder events were held 2019 to gather further views on the call for evidence. Forty-four attendees were invited across the 3 events, comprised of employees of landlord and tenant representative groups, solicitors, letting agents, duty advisers, members of the judiciary and other interested stakeholders.

The private landlord possession action process in the County Court

15. The 2 main areas of dissatisfaction private landlords raised were timeliness and the complexity of the system. 85% of landlords said that they were not satisfied with the time taken to complete possession cases. While almost 80% of landlords who responded to the call for evidence indicated that they knew how the possession action process worked as a whole, the complexity of the process was their second biggest concern at each stage, and more than 40% stated that they found the stage of the process between application and hearing to be too complex.

16. Respondents reported experience of delays at each stage of the possession action process. A slightly smaller proportion of landlords suggested that delays had occurred at the ‘warrant of possession’ stage, when compared with the ‘order for possession’ stage and ‘enforcement by the County Court bailiff’ stage.

17. The main reasons cited for the delays in the process were linked to a lack of staff resources in the courts, principally at the possession by County Court bailiff stage, but also during the court process as a whole. These issues were also raised by representative groups including the National Landlords Association[footnote 5], the Residential Landlords Association and the Housing Law Practitioners Association.

18. Tenants indicated that possession cases were complex to understand, and they had less experience of the process compared to landlords. Only 20% of tenants had experience of possession cases in the County Court, compared to 68% of landlords. 33% of tenants indicated that they understood how each stage of the possession action process works, compared to almost 80% of landlords.

19. Responses to the call for evidence from both the judiciary and private landlords indicated that possession claim forms are often filed incorrectly which can lead to delays. The Association of District Judges commented that, in their view, “by far the biggest delays are caused by Landlords failing to comply with procedural issues or to provide the necessary evidence for the court to make a possession order and in the delay in being able to obtain an eviction date”. Meanwhile the National Residential Landlords Association suggested that many of their members find the process confusing and turn to their services for advice.

20. Members of the judiciary who responded to our call for evidence and who attended our stakeholder events underlined the importance of the statutory timeframes included in current court possession processes. These protections are in place to allow tenants time to seek legal advice on their case, and to secure alternative accommodation where necessary. These important safeguards will remain in place.

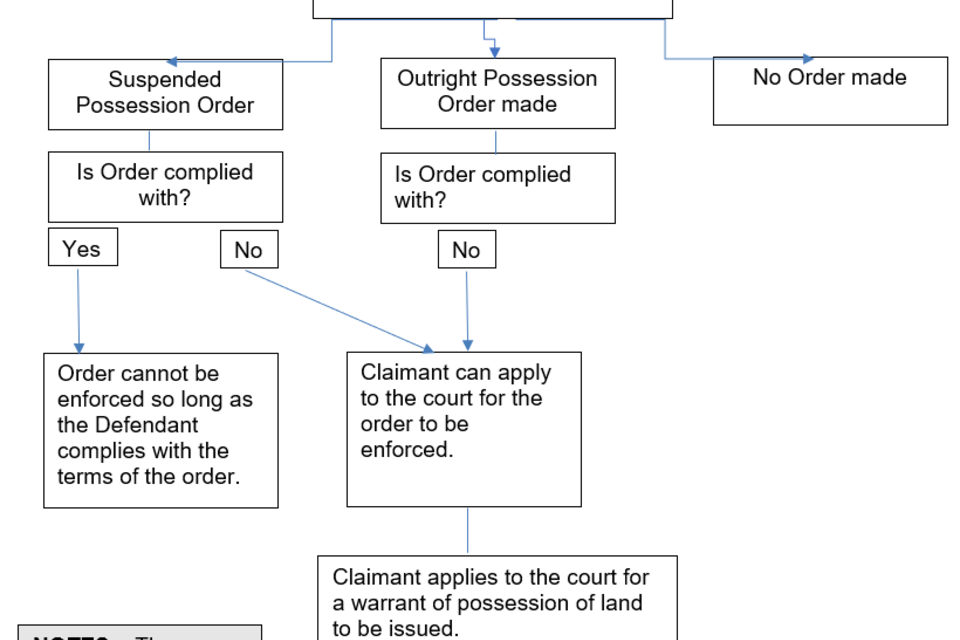

Enforcing a possession order

21. Just over half of all respondents to our call for evidence were satisfied with the process of enforcing a possession order in the County Court. This included 37% of landlords. However, 39% of landlords called for swifter County Court processes, while 16% suggested that increased recruitment of bailiffs was needed.

22. Landlords expressed concern over delays at the enforcement stage, with nearly 40% indicating that they thought that the process for enforcing possession orders should be quicker. Delays at the enforcement stage were attributed to a lack of resources (including a shortage of County Court bailiffs) and the need to apply to the court for a warrant once the Possession Order had expired. However, 90% of landlords were aware that they needed to apply for a warrant to instruct a bailiff to take possession.

Access to justice and the experience of court and tribunal users (all housing cases)

23. Just under 66% of respondents said they were not satisfied with the overall time taken to resolve the housing cases which they had experienced in the County Court, while 40% said the same for the property tribunal cases which they had experienced.

24. Respondents felt that court processes should be speeded up and streamlined and called for improved guidance for users and additional court locations. Simpler processes and improved advice were advocated in the property tribunals. The Association of District Judges called for the provision of early advice to make sure that litigants in person are fully prepared for their case.

25. Respondents, including the Law Society, suggested that more resources were needed to improve administrative processes and that digitisation of court and tribunal processes was needed. Greater access to legal aid and advice was called for to make the court processes more effective for users.

26. There was no clear consensus as to whether the County Courts or the First-tier Tribunal provided fair access to justice in property cases. Some respondents felt that the County Courts were slow and costly, while some felt that decisions displayed bias in favour of tenants. 14% of respondents suggested that judges should have better expertise, or that there should be a system of ‘ticketing’ whereby housing cases would be heard by Judges with specific expertise of housing law.

27. However, a significant proportion of respondents commented that decisions were usually made fairly and knowledgeably. More than 50% of respondents neither agreed nor disagreed that the First-tier Tribunal provided fair access to justice, with many indicating that they had no experience of Tribunal cases.

The case for structural changes to the courts and the property tribunal

28. 75% of respondents called for the introduction of a new specialist housing court, but little evidence was presented to demonstrate its necessity. There was high support for a housing court amongst individual tenants (more than 90%) and landlords (85% support). Respondents indicated that they thought a new housing court would:

- improve access to justice

- reduce the cost of bringing cases for hearing

- make access for users easier

- iImprove the timeliness of property cases

- provide more specialist knowledge and consistent judgements; and

- create a fairer, more balanced judicial environment

29. Legal and judicial stakeholders were not convinced that a new housing court would improve timeliness and effectiveness and thought that the costs of establishing a new court would outweigh any perceived benefits. The Civil Sub-Committee of the Council of Circuit Judges argued that this would create structural difficulties and complications such as deciding who would preside on cases, how they would be remunerated, and devising new procedural rules and routes of appeal.

30. The Association of District Judges suggested that a new specialist court was “unnecessary” and “would not bring any tangible improvements”; while the Law Society recommended that improvements should be made to the resourcing of existing courts and suggested that more effective processes to refer parties to advice would be a better way to make sure that cases are dealt with in a timely and efficient manner.

31. Tenant representative groups were also not convinced that a new housing court was needed. Citizens Advice were not clear how this would resolve issues such as timeliness and tenant’s lack of access to legal aid. Both Shelter and Citizens Advice were concerned that a new judicial body would prevent access to legal aid for users.

32. There was some support from respondents for changes to be made to the types of cases currently considered by the courts and property tribunals, and for transferring some cases from one jurisdiction to the other. However, there was no clear consensus on the types of cases which should be transferred. More than 75% of respondents suggested that further guidance was needed to help users to navigate the court and tribunal process.

33. Following discussion and consideration of the issues facing users of the courts and tribunal, attendees at all three of our stakeholder events concluded that improvements to County Courts and the First-tier Tribunal (Property Chamber) could be achieved in other ways, without the need to establish a specialist housing court.

Government response

34. The government wants an improved court system for all housing cases which leads to swifter justice and offers a better service, while safeguarding due process, including making sure that defendants have an effective means to respond to a case or appeal. Having considered the responses to the call for evidence, and associated stakeholder engagement, we have concluded that the costs of introducing a new housing court would outweigh the benefits, and that there are more effective and efficient ways to address the issues experienced by court and tribunal users in housing cases.

35. The government is of the view that is there is already an ample pool of knowledge about the housing possession process within the judiciary, and a new housing court is not necessary to improve the existing level of expertise.

36. The evidence we have reviewed indicates that introducing a housing court would not address the underlying issues raised such as timeliness, resourcing, access to legal aid (particularly for those in receipt of benefit) and the provision of information and advice. The government believes there are better, more effective ways to tackle these issues and is implementing a package of wide-ranging reforms to do so including:

The HM Courts and Tribunal Service (HMCTS) Possession Reform Programme

37. This will fully digitalise the end-to-end process for most claims in the County Court, allowing for the greater and more targeted provision of advice and guidance through digital means. This will reduce common user errors and improve the user experience. This work commenced in April 2022 and is expected to conclude in 2023. We are working closely with HMCTS and housing stakeholders to make sure that this Programme meets the needs of all court users.

Reviewing bailiff capacity

38. The Ministry of Justice and HM Courts and Tribunal Service have already taken steps to review bailiff capacity and have introduced efficiencies by reducing their administrative tasks. This has, and will, free up more bailiff resources to focus on the enforcement of possession orders. New payment options have been introduced to increase the ways a Defendant can make payments to bailiffs, reducing the need for doorstep visits to enforce payment. Improvements to bailiff recruitment and retention practices are also being explored.

Reforming grounds for possession

39. We will reform possession grounds so they are comprehensive, fair, and efficient for both landlords and tenants as set out in the government’s response to the consultation on a new deal for renting.

Reviewing the time taken for first possession hearings to be listed by the courts

40. The Ministry of Justice will undertake a review of the time taken for first possession hearings to be listed by the courts where the ground for possession indicates that there is a risk of serious harm to the tenant, housemates, landlord or community, including anti-social behaviour cases. Change would be subject to approval by the Civil Procedure Rules Committee and possible consultation.

Streamlining the possession claim process

41. In possession cases, user errors can often result in hearings being adjourned and rescheduled adding to case timelines. For example, the use of Section 21 is currently restricted if landlords do not comply with certain safety requirements[footnote 6]. We will make it easier for landlords to make a possession claim and reduce some of the most serious delays they experience. In the government’s response to the new deal for renting consultation we have committed to streamlining the process so that only deposit protection will have to be demonstrated when making a claim. We will consider when legislating which Section 8 grounds would be appropriate to restrict for failing to protect a deposit.

Providing earlier access to legal advice for tenants

42. On 7 February 2019, the Ministry of Justice published a Post-Implementation Review of changes to legal aid[footnote 7]. This concluded that for too long legal support has been focused solely on funding court disputes, with less emphasis on how problems can be resolved earlier to avoid them escalating into more problematic issues that require a court hearing.

43. Alongside this review, the Ministry of Justice also published a Legal Support Action Plan, which announced a series of pilots to test different routes of supporting people with social welfare problems such as housing. The plan includes the targeted expansion of legal aid, and efforts to understand the most effective interventions in the future.

44. The Plan also announced that the government would enhance the support for litigants in person, by providing an additional £3 million of funding for a period of 2 years. This funding was delivered through a new grant that commenced in 2020. The Ministry of Justice is currently working with over 50 not-for-profit organisations across England and Wales to provide support to litigants in person in civil, family and tribunal cases.

45. The Ministry of Justice is also making improvements to the Housing Possession Court Duty Scheme following the results of their recent consultation. These changes will mean that anyone facing eviction or repossession will be able to receive free early legal advice on housing, debt and welfare benefit matters before appearing in court as well as continuing to get and representation on the day of their hearing.

46. The Ministry of Justice will also be launching a trial to deliver more effective early legal advice for debt, housing, and welfare benefit matters as announced in the Legal Support Action Plan. The findings of the pilot will be used to inform future policy decisions regarding early legal advice beyond the Housing Possession Court Duty Scheme.

Improving advice and guidance

47. The Courts and Tribunal Service Possession Reform Project will digitalise processes in the County Courts, allowing greater provision of advice and guidance through digital means.

48. New government guidance for landlords and tenants in both the private and social rented sectors on how to navigate the possession process has been published and has been accessed over 73,000 times in the last year. Our A fairer private rented sector white paper commitments will create the need and opportunity for the government to introduce new consumer guidance for landlords and tenants on the possession process in the County Courts. We will simplify this guidance to improve access and ease of understanding for users.

Streamlining how specialist property cases are dealt with

49. There is currently a split jurisdiction in certain types of property cases between the civil courts and the Property Chamber of the First-tier Tribunal. To improve consistency and timeliness, the Ministry of Justice is looking at ways to streamline how such cases are processed. This could potentially provide a single judicial forum for such cases and removes the need for litigants to deal with 2 judicial forums (the County Court and Tribunal) to determine a single case, reducing costs and simplifying the process. The Ministry of Justice are currently undertaking a pilot scheme and will set out next steps in due course.

Leasehold reform

50. At present, leaseholders can be required under their lease to pay the legal costs of their landlord, regardless of the outcome of the case. The government previously announced its intention to close the legal loopholes that can require leaseholders to pay these costs. This will help to address the concerns raised by some respondents about the costliness of the Tribunal and support greater and fairer access to justice.

Reforming the process for increasing rents in the private rented sector

51. The Tribunal will have an increasingly vital role to play in the private rented sector. Tenants will continue to be able to challenge excessive rent increases through the Property Tribunal under our new tenancy system and we expect volumes of cases to increase. This is because tenants will be more empowered to challenge rent increases following the removal of Section 21 ‘no fault’ evictions. The government will reform the process of proposing and challenging rent increases in the private rented sector to make the system more transparent and accessible.

Mainstreaming dispute resolution

52. We will also strengthen the offer of mediation to landlord and tenants to facilitate the early and consensual resolution of disputes so that that only housing cases that need a judgement come to court.

Wales

53. Whilst housing policy is devolved, the jurisdiction of the County Court covers England and Wales. We will continue to work closely with the Welsh Government to ensure that our package of reforms take account of devolved policy in Wales.

Mainstreaming dispute resolution in the private rented sector

54. The vast majority of tenancy disputes do not end up in court, but currently there are insufficient incentives or support for landlords and tenants to resolve disputes earlier and find amicable solutions which work for both parties. As highlighted by the findings of our call for evidence, private sector tenants and landlords have limited options for resolving disputes without going to court, particularly compared to other tenures or consumer markets.

55. We want to create a private rented sector in which, wherever possible, disputes are resolved in the first instance by an open and honest discussion between landlord and tenant. Whilst there are examples of good practice, currently a lack of communication between tenant and landlord can lead to disputes worsening and court action becoming unavoidable. Fostering and supporting early engagement and open communication between landlords and tenants is key to our vision of creating a less adversarial and polarised rented sector. The unprecedented financial support package introduced by the government during the COVID-19 pandemic helped to keep tenants in their homes. This encouraged and promoted early and open discussion between landlords and tenants without the need for litigation and offered a more empathetic and practical solution which we want to build on in the future.

56. We expect the removal of Section 21 ‘no fault’ evictions to make dispute resolution more attractive in the private rented sector, because a landlord will need to fully justify and evidence the reasons why they require possession. This will incentivise the resolution of disputes before court action is taken and create greater equality between the parties.

57. To support this shift to earlier, less adversarial dispute resolution, we will introduce a single government-approved Ombudsman covering all private landlords who rent out property in England. The new Ombudsman will enable tenants to seek free arbitration where they have complaints about the behaviour of their landlord, the standards of their property or where repairs have not been completed within a reasonable timeframe. Further details are provided in our A fairer private rented sector white paper. This will bring private renting in line with other housing sectors where redress schemes already exist for leasehold managing agents, lettings and estate agents, and for social housing.

58. Establishing the private landlord Ombudsman will deliver one of the commitments set out in the government response to the 2018 consultation on Strengthening Consumer Redress in the Housing Market, in which the government explored ways to address gaps in redress and streamline redress provision across housing, so that everyone has improved access to justice when things go wrong in their homes. We are also delivering on the other commitments made in that government response:

-

Improving redress for new build homebuyers. The Building Safety Act 2022 includes provision for the New Homes Ombudsman scheme to provide dispute resolution to, and determine complaints by, buyers of new build homes against developers. Developers of new build homes will be required to become and remain members of the scheme once the scheme is in place.

-

Improving complaints handling and resolution in the social sector. In November 2020 government published the Social housing white paper, setting out wide-ranging changes social housing residents told us they want to see. The measures in the Social housing white paper will improve the lives of social housing residents across the country, ensuring social housing landlords treat residents well and deliver good-quality housing and services. The Regulator of Social Housing will deliver a new proactive consumer regulation regime and we will strengthen and expand the Housing Ombudsman Service. We are also delivering a national complaints awareness campaign, informing residents of their rights and how to access the Housing Ombudsman Service. We are also speeding up access to the Housing Ombudsman by removing the Democratic Filter in the Building Safety Act.

59. In addition to strengthening redress for tenants, we also want to support landlords to resolve disputes and sustain tenancies. We will shortly publish a Post Implementation Review of the recent Rental Mediation Pilot developed in response to the COVID-19 pandemic which offered independent mediation to landlords and tenants as part of the court possession process. We will use the findings and the lessons learned to help us to decide how mediation, as one method of dispute resolution, can further help to sustain tenancies in the future.

60. In 2021, the Ministry of Justice published a call for evidence on dispute resolution in England and Wales. This set out the government’s ambition to transform the culture of dispute resolution by significantly increasing the use of alternatives to litigation, such as mediation, to resolve disputes across the civil and family courts and tribunals. A summary of responses to the call for evidence has been published. We will continue to work closely with the Ministry of Justice to make sure our work is aligned and the government’s approach to dispute resolution is rounded.

61. We will also continue to work with the Ministry of Justice to explore options for pre-court action resolution for private landlords as highlighted in the Civil Justice Council’s Report on Pre-Action Protocols which closed in December 2021.

Impact of COVID-19 on the courts and court users

62. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, public health measures were introduced by the government in 2020 and 2021 to help control the spread of infection, prevent any additional burden falling on the NHS, and avoid overburdening local authorities in their work to provide housing support and protecting public health. The measures included a 6 month stay on possession proceedings and a ban on bailiff-enforced evictions in all but the most egregious cases, alongside temporary extensions to notice periods before court action could be taken. The stay on possession proceedings ended in September 2020 and the ban on bailiff enforced evictions ended in May 2021. Notice periods have returned pre pandemic levels on 1 October 2021.

63. The government introduced an unprecedented package of financial support to help renters to pay their rent during this period through the welfare system and the Job Retention scheme. The government also provided a one-off additional £65 million top-up to the Homelessness Prevention Grant to enable local authorities to help vulnerable households with rent arrears and reduce the risk of them being evicted and becoming homeless.

64. To manage the flow of cases after the stay on possession cases ended, a Working Group led by the judiciary introduced temporary court arrangements. This included prioritising and triaging cases before the substantive hearing to make sure that claimants were able to swiftly access justice in the most egregious cases. An opportunity for cases to be resolved before progressing to a full hearing was introduced to the court possession process, which encouraged landlord and tenants to communicate with each other to agree rent repayment plans and resolve disputes.

65. However, at the time of publication of this government response, the median time taken from claim to possession has risen to 27 weeks on average in January to March 2022, compared to 21 weeks in 2019, before the COVID-19 pandemic. These cases are likely to have been affected by the government measures to protect renters including the stay on possession and ban on eviction and are not representative of pre-Covid trends. Although HMCTS report that the majority of courts are now listing a hearing within 8 weeks of a claim being received, the Covid experience has heightened calls for a more efficient court process for possession from landlords and agents.

66. The increase in the time taken for cases to progress through the courts should be viewed in the context of lower possession claim volumes, which have dropped substantially, and although they are rising gradually, landlord claim volumes remain below pre-Covid levels. There were 19,033 claims[footnote 8] for possession by all landlords between January to March 2022, a decrease of 37% compared to the same quarter in 2019. This indicates that many claimants continue to show forbearance and are using alternatives to court action to resolve issues and disputes.

67. Historically, possession claims for social housing made up the greatest proportion of all possession claims. As claim volumes have started to increase as the emergency pandemic public health measures were relaxed, claims brought by private landlords currently form the greatest proportion of landlord claims overall and have broadly returned to pre-pandemic levels.

2. Detailed findings from the call for evidence

Methodology and datasets

68. The primary dataset used is the response received to the government’s online consultation survey, and this data is presented in the tables below. We received written responses from sector representative bodies and charities representing the views of landlords, tenants, property agents and members of the judiciary. These have been included where possible and are reflected in the narrative.

69. Feedback from the three stakeholder events held in 2019 has also been reflected where this is relevant and adds insight to a particular question or section.

About the respondents

Qa) In which capacity are you completing these questions? (please tick all that apply)[footnote 9]

| Categories | Numbers | Percentages |

|---|---|---|

| Landlords | 207 | 29% |

| On behalf of an organisation | 167 | 24% |

| Other | 152 | 22% |

| Tenant | 100 | 14% |

| Homeowner | 66 | 9% |

| Member of the judiciary | 10 | 1% |

| Total* | 702 | 99% |

*Percentages do not sum to 100 due to rounding.

70. The majority of responses were received by landlords, followed by responses on behalf of an organisation. These included submissions from landlord, tenant and judicial representative organisations (see Qc) below). Those who selected ‘Other’ included those who were responding as a solicitor (accounting for 30% of those in the Other category) or as Leaseholder (accounting for 22%).

71. Of the 10 members of the judiciary who responded to the call for evidence, 9 provided a comment in the free text box, to indicate the position which they held. Of these, 4 were judges in the First-tier Tribunal (one of whom was also a Barrister specialising in housing law) and 2 were Barristers, while the remaining 3 were a housing law caseworker in a solicitors’ practice, a Deputy Regional Valuer of the First-tier Tribunal and a District Judge.

Qb): If you are replying as a landlord, how many rental properties do you own?

| Number of properties | Number of landlords who responded | Percentages |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 26 | 13% |

| 2 | 29 | 14% |

| 3 | 22 | 11% |

| 4 | 13 | 6% |

| 5-9 | 44 | 21% |

| 10-24 | 25 | 12% |

| 25-100 | 17 | 8% |

| More than 100 | 29 | 14% |

| Total* | 205 | 99% |

*Percentages do not sum to 100% due to rounding.

Qc): If you are replying on behalf of an organisation, which of the following best describes you? Please leave blank if you are answering as an individual.

| Type of organisation | Number of respondents | Percentages |

|---|---|---|

| Other (please specify) | 53 | 33% |

| Landlord organisation | 37 | 23% |

| Property or letting agent | 30 | 18% |

| Advice provider | 26 | 16% |

| Charity that deals with housing issues | 7 | 4% |

| Judiciary membership body or organisation | 5 | 3% |

| Tenant representative body | 5 | 3% |

| Total | 163 | 100% |

72. The most common types of organisations who selected ‘Other’ were solicitors or law firms (24% of those who selected Other), local government bodies (24%) and organisations who identified as professional or representative bodies (17%).

The private landlord possession process in the County Court

Q1: Have you had experience of possession cases in the County Court?

| Landlord | Member of the judiciary | Tenant | Homeowner | On behalf of an organisation | Other | Totals | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | 139 (68%) | 5 (56%) | 19 (20%) | 8 (12%) | 115 (75%) | 95 (64%) | 381 (56%) |

| No | 66 (32%) | 4 (44%) | 77 (80%) | 58 (88%) | 38 (25%) | 53 (36%) | 296 (44%) |

| Total | 205 (100%) | 9 (100%) | 96 (100%) | 66 (100%) | 153 (100%) | 148 (100%) | 677 (100%) |

73. Just over half of respondents indicated that they had experience of possession cases in the County Court. The majority of landlords (68%), and those answering on behalf of an organisation (75%) indicated that they had had experience of possession cases. Most tenants (80%) and homeowners (88%) did not have experience of these cases.

Q2: If you answered yes to Q1, was possession sought under section 8 or section 21 of the Housing Act 1988?

| Landlord | Member of the judiciary | Tenant | Homeowner | On behalf of an organisation | Other | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Section 8 | 25 (19%) | 0 | 1 (6%) | 0 | 7 (7%) | 4 (5%) | 37 (11%) |

| Section 21 | 46 (35%) | 0 | 9 (53%) | 1 (14%) | 12 (11%) | 3 (3%) | 71 (20%) |

| Both | 57 (44%) | 5 (100%) | 3 (18%) | 3 (43%) | 83 (78%) | 75 (86%) | 226 (64%) |

| Don’t know | 2 (2%) | 0 | 4 (24%) | 3 (43%) | 4 (4%) | 5 (6%) | 18 (5%) |

| Total | 130 (100%) | 5 (100%) | 17 (101%)* | 7 (100%) | 106 (100%) | 87 (100%) | 352 (100%) |

*Column does not total 100% due to rounding.

74. Of the 381 respondents who answered yes to Q1, 352 answered Q2. Of these, 64% indicated that they had experience of both section 21 and section 8 cases. Experience of section 21 possession cases was slightly higher amongst those who responded to this question, as compared to experience of possession cases brought under section 8.

75. Tenants tended to have more experience of section 21 cases, compared to section 8 cases. For landlords, there was a more even spread of those who had experienced section 8 and section 21 cases, although with a slightly higher proportion of respondents indicating that they had experience of section 21.

Q3. What were your experiences of these cases?

76. Question 3 was a free text box allowing respondents to provide more details on their experiences of possession cases in the County Court. 318 respondents left a comment. These free text comments were categorised and coded based on the content of the statements. Each comment could be coded into multiple categories dependent on its content.

77. The most common comments centred on a perception that possession case processes in the County Court were slow or drawn out, with adjournments common (53% of respondents), and that it was expensive (24%). Landlords accounted for most of these respondents (55% of those who said that it was slow or drawn out, and 69% of those of who said that it was expensive, were landlords).

78. 14% of respondents to this question commented that the process was complex and difficult to understand, and 10% suggested that court users were unaware of their rights and responsibilities or made errors. Meanwhile, 14% (of which 70% were responses from landlords) argued that the process was biased towards tenants and that there was a lack of advice for landlords on the process. A smaller percentage of respondents argued that the process was satisfactory (7% of respondents) or straightforward (5%).

79. Twelve per cent of respondents noted that they had experienced inconsistent or variable outcomes, whilst 11% felt that judges lacked knowledge of housing law. Meanwhile, 12% of respondents, predominantly landlords, commented that they had experienced delays during the enforcement process.

80. In the Residential Landlords’ Association’s response, it was felt that possession cases were “frequently too slow with delays throughout the process”. They also suggested that the design of the section 8 process causes frustration and delay, particularly when a tenant pays off just enough rent to avoid a mandatory possession order and forcing a landlord to make a new application to the courts. Similarly, the National Landlords Association noted that their members felt that the section 8 process was more costly, time-consuming and uncertain than using the section 21 process.

81. In Shelter’s response, they noted that there may be delays during the possession process which could be addressed through “adequate resourcing and specific service standards”. However, they stressed the importance of allowing adequate time for a tenant to defend a case and follow the correct procedures, suggesting that “there should be no weakening of existing safeguards for tenants”. They also raised concerns over the complexity of the possession process. However, they noted that due to the complexity of the underlying housing law, such cases will “inevitably require a certain amount of formality and complexity in the court processes”.

82. The Law Society reported that its members had both positive and negative experiences of County Court cases. On the one hand, section 21 claims and section 8 claims (which must be demonstrated by using a ground for possession) were quick and efficient. Section 21 cases only result in a hearing due to mistakes in the paperwork or the failure of the landlord to follow correct procedures (such as correctly protecting the tenants’ deposit), while section 8 cases are only adjourned if it would be unreasonable for the landlord to obtain possession or if a substantive defence or counterclaim is raised. Listed ‘possession days’ allow several cases to be dealt with at once and court ushers are generally helpful, whilst Possession Claims Online facilitates the efficient issuing of claims.

83. However, the Law Society’s members also raised concerns about a lack of staff resources across all stages of the court process. There was also felt to be a lack of knowledge of the court processes amongst both landlords and tenants. Meanwhile tenants are only able to access the duty solicitor for advice at a late stage of the process, whilst legal aid changes have resulted in a lack of affordable advice, leading many tenants to represent themselves without expert legal advice.

84. At the stakeholder events, it was felt that the possession action process generally worked well, and that some of the perceived delays in the system were in fact prescriptive timelines designed to safeguard the rights of the parties involved. Attendees commented that litigants sometimes made errors when completing the required paperwork which can contribute to delays. This underlines the complexities of the system; however, the Possession Claims Online system is seen to work well and helps to reduce errors.

85. Concerns were raised at the stakeholder events about the differences in the time taken to process cases at different courts, and about procedural errors on the administrative side which can lead to recurring suspensions of court hearings. It was felt that a lack of resources, exacerbated by court closures, may have contributed to these delays.

Q4: Are there any particular stages within the possession process where you have experienced delays?

| Landlord | Member of the judiciary | Tenant | Homeowner | On behalf of an organisation | Other | Totals | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | 118 (91%) | 3 (60%) | 11 (65%) | 6 (86%) | 90 (87%) | 58 (67%) | 286 (82%) |

| No | 12 (9%) | 2 (40%) | 6 (35%) | 1 (14%) | 14 (13%) | 29 (33%) | 64 (18%) |

| Total | 130 (100%) | 5 (100%) | 17 (100%) | 7 (100%) | 104 (100%) | 87 (100%) | 350 (100%) |

| Don’t know | 2 (2%) | 0 | 4 (24%) | 3 (43%) | 4 (4%) | 5 (6%) | 18 (5%) |

86. Just over 80% of those who responded to this question indicated that they had experienced delays during the possession process. A higher proportion of landlords (91%) than tenants (65%) indicated that they had experienced delays. In their response, the Residential Landlords Association cited delays in the processing of paperwork (including letters), shortages of judges and the under-resourcing of the bailiff service as issues of concern. The National Landlords Association were concerned about waiting times for bailiff appointments which, they suggested, resulted in many landlords seeking possession by a High Court Enforcement Officer.

87. The Housing Law Practitioners Association suggested that perceptions of delay by private landlords are generally attributable to landlords’ lack of experience, their own postponement of legal action (by trying to address matters informally prior to taking legal action), errors in filling out paperwork and to legitimate defences to a claim being viewed as delaying tactics. However, they agreed that a shortage of bailiffs is a matter of concern, and that underfunding of the courts has led to delays in processing cases and understaffing.

Government response

88. The government is committed to making the County Court and Tribunal processes work as effectively as possible for all users. For landlords, this means offering a more efficient court process to provide confidence that they can take possession of their property when needed. Guidance is also needed to improve landlords’ understating of how the possession action process works and to underline the importance of the statutory safeguards built into the process which allow tenants can seek legal advice on their case, and time to secure alternative accommodation to avoid homelessness.

89. To address the delays in the possession action process which respondents identified in Questions 3 and 4, the HMCTS Possession Reform Programme will provide the opportunity to consider options that may reduce the potential for errors which can lead to delays. This will also allow for the greater and more targeted provision of advice and guidance through digital means to improve the user experience. This work is underway and expected to conclude in 2023. We are working closely with HMCTS and housing stakeholders to make sure that this Programme meets the needs of all court users.

90. There is potential to make further improvements by reviewing the amount of time for courts to list a hearing date. The government intends to consult the Civil Procedure Rules Committee to make this change to Civil procedure Rules in cases where there is a risk of serious harm such as anti-social behaviour cases.

Q5. At which stage of the possession action process through the court did you experience delays? Please tick one or more of the options below, and in the textbox explain what, from your understanding, were the reasons why these delays occurred.

| Landlord | Member of the judiciary | Tenant | Homeowner | On behalf of an organisation | Other | Totals | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Landlord claim process | 68 (60%) | 2 (67%) | 5 (63%) | 3 (60%) | 45 (56%) | 30 (59%) | 153 (59%) |

| Court order issued | 69 (61%) | 1 (33%) | 2 (25%) | 4 (80%) | 53 (65%) | 36 (71%) | 165 (63%) |

| Warrant for Possession | 58 (51%) | 1 (33%) | 3 (38%) | 2 (40%) | 54 (67%) | 40 (78%) | 158 (61%) |

| Possession by County Court bailiff | 68 (60%) | 2 (67%) | 3 (38%) | 2 (40%) | 51 (63%) | 36 (71%) | 162 (62%) |

| Total no. of respondents* | 113 | 3 | 8 | 5 | 81 | 51 | 261 |

*Percentages for this question do not total 100%, and totals do not sum, because individual respondents could select more than one answer.

91. Respondents to this question reported delays across all stages of the possession action process, with response rates to each stage grouped between 59% and 63%. Fewer landlords indicated that they had experienced delays at the Warrant for Possession stage when compared to the other stages, whereas the highest proportion of those answering on behalf of an organisation (67%) and those responding as ‘Other’ (78%) identified the Warrant for Eviction stage as where they had experienced delays. Members of the judiciary were more likely to indicate that they had experienced delays during the landlord claim process and the Warrant for Possession stage.

92. Using the free text box, 235 respondents left a comment explaining the reasons why delays had occurred. The most common response (34% of the respondents who left a comment) was that a shortage of, or variable access to, bailiffs caused delays at the enforcement stage.

93. Just over 3 out of 10 respondents attributed delays to under-resourcing more generally, and 23% to a backlog or large volume of cases being handled by the courts. Meanwhile, 29% attributed delays at the landlord claim stage to the length of time taken for a case to be listed, and therefore for a court date to be secured.

94. The Association of District Judges suggested that the biggest causes of delays were landlords failing to comply with procedural issues or to provide the necessary evidence for the court to make a possession order, whilst the delay in obtaining an eviction date was due to a shortage of bailiffs. They commented that a reduction in staff numbers in recent years has led to delays in the issuing of court orders after they have been made by the judge. The Law Society commented that its’ members had experienced delays with listings and adjournments, court orders being issued, warrants being sent and with enforcement. They attribute these delays to a lack of court staff, court closures and insufficient court time.

95. The Housing Law Practitioners Association commented that delays tended to occur in the listing of hearings and in the courts’ handling of paperwork. They attribute this to the courts being underfunded and understaffed.

Government response

96. The government recognises that there is no clear consensus as to the stage at which delays occur, which is why we are acting to simultaneously improve several aspects of the possession action process.

97. We intend to analyse the possession process and the time taken to obtain an Order for Possession to review the time taken for courts to list a hearing date in cases where there is a risk of serious harm such as anti-social behaviour cases. This is subject to approval by the Civil Procedure Rules Committee and possible consultation. The HMCTS Possession Reform Programme will make it easier to identify issues which may be relevant to the case, such as ongoing benefits claims. This will reduce the number of adjournments while such matters are explored therefore speeding up the average time taken to receive a Court Order.

98. HM Courts and Tribunal Service and the Ministry of Justice is seeking to reduce the delays experienced during the enforcement stage by removing some administrative tasks from bailiffs to allow them to focus more resource on enforcing possession orders.

Q6. Do you understand how each stage of the possession action process works?

| Landlord | Member of the judiciary | Tenant | Homeowner | On behalf of an organisation | Other | Totals | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | 148 (79%) | 8 (89%) | 32 (36%) | 15 (25%) | 126 (91%) | 96 (70%) | 425 (69%) |

| No | 39 (21%) | 1 (11%) | 56 (64%) | 44 (75%) | 13 (9%) | 42 (30%) | 195 (31%) |

| Total | 187 (100%) | 9 (100%) | 88 (100%) | 59 (100%) | 139 (100%) | 138 (100%) | 620 (100%) |

99. There was a clear split in understanding of the possession action process between landlords on the one hand, and tenants and homeowners on the other. 36% of tenants and 25% of homeowners indicated that they understood how each stage of the possession action process works, compared to 79% of landlords.

Q7. If you answered no to Question 6, please provide more information on the stage or stages of the possession action processes which you don’t understand, and why, in the textbox below.

100. This was a free text box, enabling respondents who had answered ‘No’ to Question 6 to explain what stage or stages of the possession action process they didn’t understand and why. Of the 195 respondents who answered No to Question 6, 83 provided a comment in Question 7.

101. Just over 33% attributed their lack of understanding to having had no first-hand experience of the processes. 28% said that they did not understand any part of the process, and 13% said that the possession action process was complicated or confusing. In their response, the Residential Landlords Association suggested that many of their members find the process confusing and turn to their advice services for assistance.

Government response

102. The HMCTS Reform Programme will provide the opportunity to digitise a range of court and tribunal processes, resulting in improved advice and guidance, reduced common user errors and an improved user experience. This programme is underway and is expected to conclude in 2023.

Q8. Are improvements to the County Court action processes needed?

| Landlord | Member of the judiciary | Tenant | Homeowner | On behalf of an organisation | Other | Totals | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | 174 (98%) | 5 (71%) | 61 (84%) | 30 (86%) | 114 (84%) | 103 (82%) | 487 (88%) |

| No | 4 (2%) | 2 (29%) | 12 (16%) | 5 (14%) | 21 (16%) | 23 (18%) | 67 (12%) |

| Total | 178 (100%) | 7 (100%) | 73 (100%) | 35 (100%) | 135 (100%) | 126 (100%) | 554 (100%) |

103. 88% of respondents told us that improvements were needed to the County Court possession action process. On the whole, all groups of respondents, including members of the judiciary, agreed that improvements were needed.

Q9. What are the main issues at each stage of the current process? Please provide details below.

a) From application to Court Hearing

| Issues (Respondents could select multiple options from the below list) | Landlord | Member of the judiciary | Tenant | Homeowner | On behalf of an organisation | Other | Responses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Too complex | 65 (43%) | 1 (33%) | 25 (63%) | 20 (83%) | 37 (35%) | 20 (24%) | 168 (41%) |

| Too confusing | 40 (26%) | 1 (33%) | 21 (53%) | 16 (67%) | 28 (27%) | 15 (18%) | 121 (30%) |

| Takes too long | 136 (90%) | 1 (33%) | 21 (53%) | 12 (50%) | 74 (70%) | 38 (46%) | 282 (69%) |

| Other | 20 (13%) | 2 (67%) | 7 (18%) | 4 (17%) | 37 (35%) | 39 (47%) | 109 (27%) |

| Total no. of respondents* | 151 | 3 | 40 | 24 | 105 | 83 | 406 |

*Percentages for this question do not total 100%, and respondent type totals do not sum, because individual respondents could select more than one answer.

104. The majority of respondents to this question (69%) indicated that it took too long to progress a case from the possession claim stage to the hearing stage. However, different groups of respondents were divided on whether this was the main issue with this part of the process. Whereas 90% of landlords and 70% of organisations said that the application to Court Hearing stage took too long, 63% of tenants and 83% of homeowners who responded to this question indicated that this part of the process was too complex.

105. Of 406 respondents, 235 chose to leave a comment in the available free text box. Of those that left a comment, 32% said they felt the waiting time for the first hearing was too long; this was predominantly raised by landlords. 20% concluded that the length of the process was due to a shortage of court staff.

106. In their response, the Association of District Judges suggested that both landlords and tenants would benefit from inexpensive “expert and professional advice as to their rights, formalities and procedures before applications to court are made”. The Law Society also advocated the provision of advice at an earlier stage in the process. They also raised concerns about a lack of legal aid for housing benefit advice, the lack of any housing advice in parts of the country and the prevalence of litigants in person, who may lack understanding about the court process.

Government response

107. In February 2019, the Ministry of Justice published the Legal Support Action Plan which announced a series of pilots to test different routes of supporting people with social welfare problems such as housing. The plan includes a targeted expansion of legal aid and a plan for the most effective interventions going forward. In addition, the Plan announced that the government would enhance the support for litigants in person, by providing an additional £3 million of funding for a period of 2 years. This funding was delivered via a new grant that commenced in 2020 and is currently working with over 50 not-for-profit organisations across England and Wales to provide support to litigants in person in civil, family and tribunal cases.

108. The Legal Aid Agency reviews the access to services across the country on a regular basis and takes any necessary action to maintain access to those services. Wherever an individual is in England and Wales, legal advice for housing is available through the Civil Legal Advice telephone service which offers legal aid services in a range of issues to those who need them. The Ministry of Justice is also investing £5 million in innovative new technologies to help people access legal support wherever they are in England and Wales.

109. The Ministry of Justice intend to improve the application to court hearing stage by reviewing the amount of time by which courts must list a hearing date under the Civil Procedure Rules in cases where there is a risk of serious harm such as anti-social behaviour cases. This will potentially reduce the time taken for first possession hearings to be listed by the courts. This is subject to approval by the Civil Procedure Rules Committee and possible consultation. We believe that this will not significantly impair the timeframe for tenants to seek legal advice or make alternative housing arrangements.

b) From Court Hearing to obtaining a Possession Order

| Issues (Respondents could select multiple options from the below list) | Landlord | Member of the judiciary | Tenant | Homeowner | On behalf of an organisation | Other | Responses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Too complex | 39 (29%) | 1 (50%) | 20 (51%) | 14 (61%) | 27 (34%) | 19 (24%) | 120 (32%) |

| Too confusing | 25 (19%) | 1 (50%) | 19 (49%) | 11 (48%) | 27 (34%) | 15 (19%) | 98 (26%) |

| Takes too long | 115 (85%) | 1 (50%) | 23 (59%) | 13 (57%) | 67 (69%) | 38 (48%) | 257 (69%) |

| Other | 23 (17%) | 1 (50%) | 4 (10%) | 4 (17%) | 33 (34%) | 35 (44%) | 100 (27%) |

| Total no. of respondents* | 135 | 2 | 39 | 23 | 97 | 79 | 375 |

*Percentages for this question do not total 100%, and respondent type totals do not sum, because individual respondents could select more than one answer.

110. Almost 66% of respondents indicated that the process from court hearing to obtaining a Possession Order took too long.

111. Of the 207 respondents who chose to leave a comment in the free text box, 21% told us of long waiting times to be given court hearing dates or excessive time between adjourned hearings. Respondents again highlighted the lack of court resources as a contributing factor to the time taken at this stage of the process, including staff shortages and judge availability. However, in their response the Association of District Judges commented that so long as the necessary rules and regulations have been complied with “hearings proceed promptly, and delays are rare”.

Government response

112. The government acknowledges the concerns raised of adjournments of court hearings during possession cases. Improving information and guidance to improve understanding of the process and responsibilities of all parties will reduce the level of adjournments.

c) From obtaining an Order to Enforcement (getting possession of the property)

| Issues (Respondents could select multiple options from the below list) | Landlord | Member of the judiciary | Tenant | Homeowner | On behalf of an organisation | Other | Responses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Too complex | 28 (21%) | 1 (33%) | 23 (62%) | 11 (50%) | 19 (20%) | 17 (22%) | 99 (27%) |

| Too confusing | 21 (16%) | 0 | 19 (51%) | 7 (32%) | 18 (19%) | 12 (15%) | 77 (21%) |

| Takes too long | 127 (95%) | 1 (33%) | 21 (57%) | 13 (59%) | 78 (82%) | 47 (60%) | 287 (78%) |

| Other | 11 (8%) | 2 (67%) | 5 (14%) | 4 (18%) | 22 (23%) | 20 (26%) | 64 (17%) |

| Total no. of respondents* | 134 | 3 | 37 | 22 | 95 | 78 | 369 |

*Percentages for this question do not total 100%, and respondent type totals do not sum, because individual respondents could select more than one answer.

113. Most respondents (78%) indicated that the main issue in obtaining an Order to Enforcement was that it took too long. This percentage was the highest of the three stages of the possession action process, which corresponds with the findings from a recent independent research report which investigated the factors influencing the progress, timescales and outcomes of housing cases in County Courts. The research found that “the main delays in the [possession] process relate to enforcement”[footnote 10].

114. 95% of landlords and 82% of organisations selected that the main issue at the Order to enforcement stage was that it took too long. However, a slightly higher proportion of tenants said that this stage was too complex rather than it took too long.

115. Of the 200 respondents who left a comment using the free text box, 29% attributed delays in the enforcement stage to a shortage of bailiffs.

Q10. As a private landlord, how satisfied are you with the time taken to complete possession cases?

| Responses | Percentages | |

|---|---|---|

| Not Satisfied | 122 | 85% |

| Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied | 9 | 6% |

| Fairly satisfied | 3 | 2% |

| Satisfied | 3 | 2% |

| Very satisfied | 6 | 4% |

| Total* | 143 | 99% |

*Percentages do not sum to 100% due to rounding.

116. 85% of landlords who answered this question indicated that they were not satisfied with the time taken to complete possession cases.

117. Of the 143 landlords who answered this question, 86 left a comment. 67% said that they found the possession process to be slow. 47% felt that delays in resolving possession cases can lead to further loss of rent payments or a continuation of anti-social behaviour.

Government response

118. The government acknowledges that there can be delays in enforcement once a court has granted a warrant for possession. The Ministry of Justice and HM Courts and Tribunal Service have already taken steps to review bailiff capacity and introduced efficiencies by reducing their administrative tasks. This has and will free up more bailiff resources to focus on the enforcement of possession orders. Improvements to bailiff recruitment and retention practices are also being explored.

Enforcing a Possession Order

Q11: Do you have experience of the enforcement stage of a possession order in the County Court?

| Landlord | Member of the judiciary | Tenant | Homeowner | On behalf of an organisation | Other | Totals | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | 92 (57%) | 4 (67%) | 11 (20%) | 5 (17%) | 96 (73%) | 75 (67%) | 283 (57%) |

| No | 69 (43%) | 2 (33%) | 43 (80%) | 24 (83%) | 35 (27%) | 37 (33%) | 210 (43%) |

| Total | 161 (100%) | 6 (100%) | 54 (100%) | 29 (100%) | 131 (100%) | 112 (100%) | 493 (100%) |

119. There was a clear divide in experience of the enforcement stage. 57% of landlords had experience, but only 20% of tenants and 17% of homeowners had experience.

Q12: How satisfied were you with the enforcement process in:

a) the County Court (using a warrant of possession)[footnote 11]

| Landlord | Member of the judiciary | Tenant | Homeowner | On behalf of an organisation | Other | Totals | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not Satisfied | 52 (62%) | 1 (33%) | 7 (70%) | 1 (20%) | 36 (40%) | 25 (36%) | 122 (47%) |

| Fairly satisfied | 21 (25%) | 0 | 2 (20%) | 1 (20%) | 36 (40%) | 17 (24%) | 77 (29%) |

| Satisfied | 9 (11%) | 1 (33%) | 1 (10%) | 1 (20%) | 14 (16%) | 20 (29%) | 46 (18%) |

| Very satisfied | 2 (2%) | 1 (33%) | 0 | 1 (20%) | 4 (4%) | 2 (3%) | 10 (4%) |

| I have not used the County Court enforcement process before | 0 | 0 | 1 (20%) | 0 | 6 (9%) | 7 (3%) | |

| Total* | 84 (100%) | 3 (99%) | 10 (100%) | 5 (100%) | 90 (100%) | 70 (101%) | 262 (101%) |

*Percentages for this question do not total 100%, because individual respondents could select more than one answer.

120. Overall, satisfaction with the County Court enforcement process was evenly divided, with 47% of respondents indicating that they were not satisfied with this process and 51% indicating that they were either Fairly Satisfied, Satisfied or Very Satisfied.

121. The Association of District Judges observed that many landlords seek a transfer to the High Court for enforcement owing to the shortage of County Court bailiffs and the consequent delay in obtaining an appointment. They noted that “a fully resourced County Court bailiff service would avoid the additional expense of applications to transfer to the High Court”. The Law Society noted that “it takes 6-8 weeks to get a bailiff appointment at some courts, which is unacceptably slow when the court orders possession in 14 days or forthwith”.

122. Concerns were also raised at the stakeholder events over the timeliness of enforcement by County Court bailiffs. This was attributed to a shortage of bailiffs, particularly as they are required for other types of cases in addition to housing possessions.

Government response

123. The government acknowledges that there can be delays in enforcement once a court has granted a warrant for possession. The Ministry of Justice and HM Courts and Tribunal Service have already taken steps to review bailiff capacity and introduced efficiencies by reducing their administrative tasks. This has and will free up more bailiff resources to focus on the enforcement of possession orders. Improvements to bailiff recruitment and retention practices are also being explored.

b) the High Court (using a Writ of Possession)

| Landlord | Member of the judiciary | Tenant | Homeowner | On behalf of an organisation | Other | Totals | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not Satisfied | 9 (12%) | 1 (33%) | 2 (22%) | 1 (20%) | 21 (25%) | 18 (26%) | 52 (21%) |

| Fairly satisfied | 9 (12%) | 1 (33%) | 0 | 0 | 10 (12%) | 10 (14%) | 30 (12%) |

| Satisfied | 5 (6%) | 0 | 2 (22%) | 1 (20%) | 12 (14%) | 10 (14%) | 30 (12%) |

| Very satisfied | 4 (5%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (20%) | 4 (5%) | 3 (4%) | 12 (5%) |

| I have not used the High Court enforcement process before | 51 (65%) | 1 (33%) | 5 (56%) | 2 (40%) | 38 (45%) | 28 (41%) | 125 (50%) |

| Total | 78 (100%) | 3 (99%) | 9 (100%) | 5 (100%) | 85 (101%) | 69 (99%) | 249 (100%) |

124. Of those who responded to Question 12b, half had not used the High Court enforcement process before. Of the 124 respondents who had used the High Court enforcement process, 42% indicated that they were Not Satisfied, 24% were Fairly Satisfied, 24% were Satisfied and 10% were Very Satisfied.

125. In their response, the Association of District Judges raised concerns over cases being transferred to the High Court for enforcement without a judicial order for transfer. The Housing Law Practitioners Association considered the High Court enforcement process to be “fundamentally flawed, as there is (currently) no requirement that notice be given of the eviction.” They strongly recommended that this was changed.

126. In their response, the Law Society commented that “enforcement in the high court was far faster (than the County court) but the paperwork can be confusing”. They believed that High Court enforcement should be available “as a right to those who wish to spend the extra money” and that it is particularly beneficial as a means of rapid eviction in cases of serious antisocial behaviour.

Government response

127. Due to delays experienced by landlords at the at the enforcement by County Court bailiff stage, increasing use has been made of transfers to the High Court for enforcement. Prior to 1 October 2020, under the High Court enforcement process, there was no requirement to give notice of the eviction, and concerns had been expressed about transferring to the High Court for enforcement without a judicial order for transfer.

128. The Civil Procedure Rule Committee conducted a consultation about the enforcement of Possession Orders in the High Court and County Court. This set out proposals to align some processes for enforcement of possession orders in the High Court and County Court, and questioned whether the need to obtain permission from a judge to enforce most possession orders in the High Court should be removed. This was based on whether judges were satisfied that the occupiers have relevant notice of the proceedings. This consultation closed in May 2019 and a new rule came into force on 1 October 2020 that aligns procedures for enforcement of possession of the High Court and the County Court. The new rule provides for a notice period to be given by the enforcement officer to a tenant before eviction in private and social housing as well as commercial property/land cases. As a formal notice period is now provided, the need to obtain permission from a judge to enforce most possession orders in the High Court- to be satisfied that adequate notice had been provided- has been removed.

Q13. As a private landlord, were you aware of the need to apply for a warrant or writ from the court before a bailiff/High Court Enforcement Officer would be instructed to take possession?

| Yes | No | Total |

|---|---|---|

| 62 (89%) | 8 (11%) | 70 (100%) |

129. The overwhelming majority of landlords indicated that they were aware of the need to apply for a warrant of possession from the court before a bailiff or High Court Enforcement Officer would be instructed to take possession.

Q14. Was there an application to suspend the warrant or writ in your case?

| Yes | No | Total |

|---|---|---|

| 16 (23%) | 55 (77%) | 71 (100%) |

Q15. What were your experiences of the timeliness and processing of the application to suspend the warrant or writ?

130. Landlords answered that the process was slow, and frustrating to navigate. The Residential Landlords Association commented that “applications which are with the power of the court to grant should be rejected at a much earlier stage rather than proceeding to a hearing giving false hope to tenants and increasing costs for all parties”.

131. The Association of District Judges commented that suspensions often arise due to “queries over the entitlement to Housing Benefit”. They note that “these adjournments cause delay and often the eviction date is missed and has to be reset”.

Government response

132. The government announced the Early Legal Advice Pilot Scheme in Middlesbrough and Manchester, through their Legal Support Action Plan. This scheme will test the impact of how early legal advice for housing, debt, and welfare benefit matters can promote earlier resolution of issues. The aim is to prevent the escalation of problems which could otherwise lead, in due course, to applications to suspend the warrant or writ in the courts.

Q16. What, if anything, do you think could be improved about the process for enforcing possession orders

a) In the County Court?

133. 70 landlords provided a comment to this question. 39% called for swifter County Court processes and 16% suggested that increased recruitment of bailiffs was needed. 10% of those who provided a response said that they thought the enforcement stage should immediately follow the issue of a possession order, removing the need for landlords to apply to the court again for a warrant of possession.

b) In the High Court?

134. 28 landlords provided a comment. 32% said that improvements could be made by speeding up the process, with 18% saying that a more simplified process was needed. 21% of respondents said that there should be lower costs for High Court users. The Association of District Judges suggested that if the County Court bailiff service was properly resourced, there would not be a need to transfer enforcement cases to the High Court “save in cases of exceptional urgency”. In their submission, the Residential Landlords Association argued that the process for obtaining approval for High Court enforcement, through the County Court, should be streamlined and clarified.

Government response

135. HMCTS is addressing concerns over the timeliness of County Court enforcement by taking steps to remove some of their administrative tasks, enabling them to concentrate on their primary enforcement responsibilities.

136. The government has no plans to remove the need for landlords to apply to the court for a warrant of possession, as called for by some landlord respondents. The Ministry of Justice have considered making the enforcement part of the possession process automatic, following the expiry of a possession order made by the County Court. However, given that only 25% of applications progress to bailiff enforcement, this would result in a waste of bailiff time and resource on cases where the tenant will have already vacated the premises.

Access to justice and the experience of courts and tribunal services

Q17. Have you had recent experience of property cases in the County Court or First-tier Tribunal?

| Landlord | Member of the judiciary | Tenant | Homeowner | On behalf of an organisation | Other | Totals | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes, I have had experience of County Court cases | 94 (61%) | 5 (71%) | 11 (22%) | 6 (21%) | 84 (65%) | 71 (64%) | 270 (56%) |

| Yes, I have had experience of First-Tier Tribunal cases | 15 (10%) | 4 (57%) | 7 (14%) | 8 (29%) | 33 (26%) | 38 (34%) | 105 (22%) |

| No, I have had no experience of County Court or property tribunal cases | 54 (35%) | 1 (14%) | 35 (69%) | 17 (61%) | 36 (28%) | 26 (23%) | 169 (35%) |

| Total* | 154 | 7 | 51 | 28 | 129 | 111 | 478 |

*Percentages do not sum to 100%, and respondent totals do not sum, as respondents could select more than one response.

137. The free text box gave respondents the opportunity to provide more details about the types of cases which they had experienced. Of the 270 respondents who indicated that they had had experience of County Court cases, 204 left a comment. Of these, 28% said that they had experience of possession cases and 24% that they had experience of cases connected to the non-payment of rent or rent arrears.

138. Other types of cases which respondents had experienced included disrepair cases (16% of respondents) and anti-social behaviour injunctions (8%).

139. Of the 105 respondents who indicated that they had had experience of tribunal cases, 85 left a comment. 38% of these indicated that they had had experience of service charge or Section 20 cases, while 11% had experienced cases relating to the appointment of a Block Manager.

Q18. From your experience what could be made better or easier in the court processes to provide users with better access to justice in housing cases?

140. Question 18 was a free text box allowing respondents who had experience of property cases in the County Court to provide views on what could be made better or easier to improve access to justice. Of the 270 respondents who indicated that they had experience of County Court cases, 258 responded to Question 18.

141. Of those respondents who left a comment, 21% felt that the court processes should be made quicker or more efficient. More than half of these respondents were landlords. 13% of respondents thought that court processes should be streamlined or made simpler. 18% called for better communications with the courts or for improvements to administrative processes, while 14% called for the digitisation or modernisation of forms and court procedures.

142. 15% of respondents felt that improved access to legal aid and representation should be provided and 13% called for improved guidance and support to help court users to navigate the legal process.