Summary of responses and government response

Updated 23 July 2019

Executive summary

Conservation covenants are private, voluntary agreements between a landowner and a responsible body, such as a conservation charity or public body, allowing for positive or restrictive obligations to fulfil a conservation objective. They are capable of being binding not only the landowner, but also subsequent landowners, so have the potential to deliver lasting conservation benefits for the public good. Covenants offer flexibility as the parties negotiate the terms to suit their particular circumstances, including the covenant duration.

Our consultation sought views on whether we should introduce legislation for conservation covenants in England. We proposed using the Law Commission’s draft Bill as a basis for legislating, with some changes. These changes were: (1) allowing for-profit bodies to become responsible bodies, (2) requiring responsible bodies to include the location and headline objectives of conservation covenants in annual reports, and (3) requiring tenants entering covenants to have at least 15 years remaining on their lease and the landlord’s consent. We also asked whether landlords should secure agreement of relevant tenants when entering into a covenant.

We received 112 responses from a range of sectors, including farmers, landowners, conservation organisations, local authorities and groups promoting access to the countryside. Responses showed significant support for covenants – the majority saw them as a useful tool for delivering lasting conservation outcomes. A number of landowners said they would consider putting conservation covenants on their land, and many mentioned the role covenants could play in delivering 25 Year Environment Plan commitments on biodiversity net gain and nature recovery. We intend to introduce legislation for covenants in England in the Environment Bill. We will develop guidance to assist parties to conservation covenants. In terms of our proposed changes to the Law Commission proposals:

-

Allowing for-profit bodies to apply to be responsible bodies received broad support. We intend to take this proposal forward. Responsible bodies can be designated by the Secretary of State if they meet relevant guidelines.

-

We do not now intend to require responsible bodies to include the location and headline objectives of conservation covenants in annual reports. We do, however, intend to include a new provision in the Bill allowing the Secretary of State to set additional requirements for annual reports in secondary legislation.

-

After consideration of consultation responses on tenants and landlords, we do not intend to set a threshold of 15 years remaining on a lease – but rather that we revert to the Law Commission proposals for tenants to have a lease of more than seven years with some time remaining on the lease. We also do not now think it is necessary to require either tenants or landlords to secure approval from each other to enter a covenant because tenants cannot act beyond the limits of their powers and legal obligations set out in the tenancy agreement.

Beyond our proposed changes to the Law Commission proposals, respondents made comments on a range of key areas:

-

Some were concerned that covenants would not be flexible enough to allow for changes in circumstances over time. Our approach will allow parties to agree to modify or discharge obligations when circumstances change and, when they cannot agree, to refer disputes to the Lands Tribunal. Parties can design their covenant to suit their particular circumstances, covering issues such as the duration of the covenant and whether it can be transferred to another responsible body.

-

Some respondents thought the introduction of legislation would make conservation covenants compulsory. This is not our proposal. Covenants are entirely voluntary, entered into only where a landowner and responsible body chooses to.

-

Some considered that the public or third parties, such as public bodies, should have a role in monitoring and enforcement of covenants. Covenants are private agreements and we share the Law Commission’s view that to give the public or a third party a role would move them out of the private, voluntary sphere and into the public sphere. Responsible bodies will have been designated by the Secretary of State and can be delisted if they do not perform their functions.

-

Some respondents raised points about the public good element of covenants, and whether delivering a conservation purpose fulfilled the public good requirement. We share the Law Commission’s view that ‘public good’ should be used in a broad sense, and our guidance will help illustrate its meaning.

-

There was some concern prior to the consultation that covenants may be a barrier to development. After consultation, we remain of the view that covenants will not block development. Responses confirmed their likely value in net gain scenarios where they could facilitate development by securing compensatory habitat at another site.

-

Some respondents expressed concern that the value of land with covenants could fall. We remain of the view that land values could rise, fall, or stay the same. We will not be providing direct public funds to support covenants, as they are private agreements. It is a matter for the parties to be satisfied that they can fund the operation of their covenant.

Introduction and context

The government recently undertook a public consultation to seek views on our intention to introduce the Law Commission proposals for conservation covenants, with some amendments. We see conservation covenants as a valuable tool that can help deliver positive outcomes for conservation and in turn help deliver this government’s ambition to leave the environment in a better condition than we found it.

A conservation covenant is a private, voluntary agreement between a landowner and a “responsible body”, such as a conservation charity, government body or a local authority. It delivers lasting conservation benefit for the public good. A conservation covenant sets out obligations in respect of the land which can be legally binding not only on the landowner but on subsequent owners of the land.

The key features of the Law Commission proposals are:

- a conservation covenant is a voluntary and private legally-binding agreement that a landowner can to enter into with a responsible body. A responsible body is one of a limited class of organisations specified by the Secretary of State, such as a local authority, government body or a conservation charity

- a conservation covenant would deliver a conservation purpose which is for the public good, such as to conserve the natural and/or historic environment of the land

- a conservation covenant would contain obligations which could be either positive or restrictive in nature. A positive obligation would require the landowner to do something, such as manage the land to secure a conservation outcome. A restrictive obligation would secure a conservation outcome by requiring the landowner not to do something

- a conservation covenant could be binding on all future owners of the land after the current owner has disposed of it. The Law Commission proposals provide that a conservation covenant relating to a freehold will be indefinite unless the parties agree a shorter period. Conservation covenants relating to a leasehold property will not be able to last longer than the duration of the lease

- conservation covenant could be modified or ended by agreement of the parties - or if there is a dispute between them ultimately it would be possible to refer the matter to the Upper Tribunal of the Lands Chamber for decision

- conservation covenants can be enforced through the courts by the parties. Possible remedies for breaches include an injunction to prevent damaging activity; an order requiring specific performance to deliver the conservation outcomes; and the payment of damages, including exemplary damages

Our consultation lasted four weeks and closed on 22 March 2019. It supplemented the consultation undertaken by the Law Commission in 2013. We wanted to secure additional information on:

- the demand and potential for conservation covenants to secure long-term benefits from investment in nature conservation and other environmental outcomes

- the safeguards that might need to be included

- any possible unintended consequences and whether the potential costs and benefits appear a reasonable estimate of the impacts of introducing conservation covenants

- whether the Law Commission proposals, together with our proposed amendments, provide for a suitable statutory framework for conservation covenants in England

Respondents

Breakdown of respondents and stakeholder events

We received 112 responses. Farmers, landowners and their representative bodies, conservation organisations, local authorities, academics, groups promoting access to the countryside and others accounted for 80% of the responses. The rest were from members of the public.

We also held informal stakeholder meetings in October 2018 with representatives from the conservation sector, landowners and land users, and the legal profession.

| Respondent category | Number of respondents | % of total respondents |

|---|---|---|

| Farmer/Landowner/Representative Body | 23 | 20 |

| Conservation Organisation/Representative Body | 26 | 23 |

| Local Authority/National Park/Representative Body | 8 | 7 |

| Legal Body | 4 | 4 |

| Academia | 3 | 3 |

| Access Group | 6 | 5 |

| Business/Representative Body | 12 | 11 |

| Private Individual | 22 | 20 |

| Other | 8 | 7 |

Demand and potential

Q1: Should conservation covenants be introduced into the law of England?

Q2: What demand do you foresee for conservation covenants? What is the basis for your view?

Q3: What potential do you foresee for conservation covenants to deliver lasting conservation outcomes? What is the basis for your view?

Q4: What use would you make of conservation covenants?

Summary of responses

The responses demonstrated very significant support for our proposals for legislation on conservation covenants. Only seven respondents opposed them. Most concerns were based on a misunderstanding of our proposals. The main concerns were that their use could be compelled and/or that they lack sufficient flexibility to allow for changes in circumstances. Conservation covenants will be entirely voluntary and the proposed legislation will provide for parties to modify them and, ultimately, for the Lands Chamber of the Upper Tribunal to adjudicate if the parties cannot agree. We would expect referral to the Lands Chamber to be rare and will encourage parties through guidance to pursue alternative dispute resolution mechanisms.

Pie chart showing answers to question 1. 86% said yes, 8% didn't respond and 6% said no to introducing conservation covenants in England.

Responses about the likely demand for covenants ranged from significant to modest. Some felt the demand would grow over time as people became more familiar with them, while others thought there would need to be incentives to secure higher levels of uptake. A number of landowners said that they would consider putting covenants on their land to conserve, restore or create habitat for nature conservation purposes. Other uses identified included those which supplemented other mechanisms for conservation, such as in net gain scenarios, with local authorities indicating that they would consider using them to secure long-term nature conservation in infrastructure and other development cases.

In terms of potential the majority saw covenants as a useful tool that could help deliver lasting conservation outcomes. Some pointed out that they have been used successfully in other countries. There was also mention of the contribution that National Trust covenants have made to conservation and the economy. The potential role covenants could make in the delivery of the 25 Year Environment Plan commitments on net gain and nature recovery was identified by many. The need for covenants to be properly monitored and enforced to fulfil their potential was raised in several responses.

Government response

We conclude from the responses that there is both the demand and potential for conservation covenants to make a key contribution to lasting conservation. We intend to introduce legislation for conservation covenants for England as part of the Environment Bill; based on the Law Commission Bill, but with amendments to allow organisations in addition to conservation charities and public bodies to apply to become responsible bodies and to allow the Secretary of State to set additional requirements for annual reports in secondary legislation. See the responses to questions 9 and 10 below.

Unintended consequences

Question 5: What, if any, unintended consequences might there be? What is the basis for your view?

We wanted to know if there are any consequences of introducing legislation for the Law Commission proposals with our suggested amendments which had not been anticipated and could prove problematic.

This generated responses across a range of issues. Very few issues had not been previously anticipated and considered. The responses generally fall into the following categories:

- costs of managing and delivering conservation covenants

- impacts on the effectiveness of conservation generally

- impacts on development

- impacts on the value of property

- impacts on other government policies or statutory mechanisms

- impacts on future land use

- other impacts

Summary of responses

Costs of managing and delivering conservation covenants

Some thought that these costs would be greater than might be anticipated and could increase when land is transferred to a new owner. Some felt that consequences might be to discourage participation; impact on the effectiveness of the monitoring and enforcement by responsible bodies (particularly local authorities); or affect the ability of the landowner to comply with the obligations. It was felt that new owners in particular either may not fully understand their obligations, choosing to face penalties rather than comply, or removing conservation features to reduce costs.

Impacts on the effectiveness of conservation generally

There were a number of points raised. Some thought that as land can be used for a range of conservation purposes or public benefits, targeting just one could be at the detriment of others. Others thought that conservation could be undermined if covenants were used to avoid statutory designations, or to downgrade existing statutory designations. There was a concern that if they were used to conserve characteristics on land which do not warrant conservation (such as extractive uses or the setting of a site) that could dilute the meaning of conservation; and, in a net gain scenario, if the compensatory site were poorly located, the connectivity value of land could be downgraded.

Impacts on development

A few thought conservation covenants could be used to hinder or block development, whereas a number of others raised particular concerns that they could be used to circumvent planning policies and override full ecological considerations, thereby allowing harmful development on land of conservation value. There were also views that developers could seek to overturn the covenant, so the conservation interests on the compensatory land would not be delivered or there would be a “develop now conserve later” approach.

Impacts on the value of property

Some took the view that there would be a fall in the value of property or land made subject to conservation covenants.

Interaction with other government policies or statutory mechanisms

A number of points were raised. Some thought there could be uncertainty over which legislation had precedence, such as on designated heritage sites where there are management agreements with Historic England or in national parks where legislation allows for long-term management agreements. Linked to this was a concern that a covenant might contain obligations which run counter to national park purposes. Some thought there could be consequences linked to a future Environmental Land Management scheme, such as landowners getting double-funded; landowners becoming ineligible for funding (as a covenant was already delivering a conservation outcome); low uptake of covenants; or that conservation outcomes would be double counted.

Others raised concerns relating to access. These included the prospect of greater access leading to damaging activity or trespass; restricting existing rights of way; covenants being used to demonstrate that public access was never intended; or limiting landowners’ options on access if biodiversity is given priority over health and wellbeing.

Other concerns were that lawful shooting might be excluded by covenants with consequences for habitat and pest management; that statutory undertakers would not be able to perform their functions or that their “delivery costs” could increase; that public money for covenants would be at the expense of other environmental projects; landowners would deliberately create threats to land to secure compensation when they entered into a covenant; and covenants could lead to the land becoming subject of a statutory designation that the landowner would not want.

Impacts on future land use

Some thought that conservation covenants could create restrictions which are unsuitable for future circumstances, particularly as the ecology can be dynamic and practices, policies and knowledge evolve.

Other impacts

There were a number of unrelated points raised. Some identified concerns about impacts on tax relief, particularly if agricultural land is reclassified; whereas others thought land could be “tied up un-strategically”, which would create barriers for investment and could impact food production or farm diversification. Others suggested the nature of covenants and their duration may act to discourage landowner engagement. Some identified a possible impact on the landlord/tenant relationship, with the risk that provisions will be incorporated into the tenancy agreement to restrict conservation activity or that as tenants seek longer tenancies to deliver the conservation outcomes, landlords respond with higher rents.

Others thought landowners could include obligations which were not in the public good, such as fencing off access to common land. Some thought they would be used by single-issue groups to further their agendas, whereas others thought the private sector would use them to green-wash their activities or, alternatively, provide a vehicle for them to invest in green development. Some thought that they could lead to the privatisation and closure of natural space and that there would be an over-reliance on the third sector to deliver conservation improvements.

Government response

We do not think the points raised warrant further changes to the government’s proposals set out in this response. On costs, there will be some for the landowner and the responsible body from their roles in delivering a covenant. The level of costs will vary depending on the extent of their respective commitments, which will be for the parties to agree. The parties will, however, enter into a covenant voluntarily and therefore will need to conclude that the costs are ones which they are prepared to incur. We cannot anticipate the precise level of costs as this will be dependent on factors such as the type of project, but the Law Commission’s estimates for creating a covenant, monitoring it and enforcing it were set out in our consultation paper. Though these figures were drawn up in 2014 and come a degree of uncertainty, it is our view that they provide a reasonable sense of the order of magnitude.

We intend to provide guidance to encourage parties to consider how their conservation covenants can complement the conservation activities of others in the local area and to consider whether conservation covenant objectives could be designed to deliver multiple conservation and public good outcomes. However, covenants are private agreements and it is for the parties to be content with the intended outcomes. The responsible body is more likely to be able to provide strategic overview and can shape any such thinking. If the responsible body is not satisfied with the proposed outcomes, it can, ultimately, choose not to become a party to the covenant.

We do not see conservation covenants as a substitute for statutory designations. Covenants are to complement existing conservation activity. We address comments made in relation to the definition of conservation purposes in the response to question 6 below. The use of covenants in the net gain scenario, or more broadly in the development sector, would be subject to the relevant planning rules and policies that apply. Covenants are simply a tool that can be used to deliver lasting conservation outcomes.

The impact of covenants on land prices will vary. As set out in the consultation paper, the impact will depend on circumstances but primarily on the use that the land could be put to before a covenant is agreed. We are of the view that the value could fall or rise - for the reasons set out in the consultation paper. Ultimately, it will be the landowner’s choice whether to enter into a covenant after weighing up the advantages and drawbacks from their perspective.

We address many of the points about interaction with other government policies and statutory mechanisms elsewhere in the response, particularly under question 6. We do not propose to constrain how covenants might be used by the parties to deliver conservation outcomes. It will be for them to decide whether, for example, to provide for public access or allow other uses but conservation covenants do not override the pre-existing rights. Pre-existing rights binding the land (whether statutory rights or private property rights) will still be enforceable by the appropriate bodies or landowners, regardless of the later creation of a conservation covenant. We share the Law Commission views in paragraph 6.53 and 6.54 of their 2014 report; covenants should not be able to stipulate that the land cannot become the subject of a statutory designation. We are of the view that whether a covenant could be used as evidence of a landowners’ intention to dedicate their land as a public right of way will depend on the individual circumstances of each case. How covenants might be used in line with a future Environmental Land Management scheme will be shaped by the policy or legislative framework which will apply there. As we have said elsewhere, we have no plans to provide dedicated public money for conservation covenants, as they are private agreements.

We recognise that the duration of conservation covenants could mean that the obligations need to be adapted. Our proposals provide for the parties to agree to modify or discharge any or all of a covenant’s obligations and where they cannot agree they can ultimately refer the matter to the Lands Tribunal. We would expect the parties to use the Lands Tribunal only as a last resort and will encourage them through guidance to consider alternative dispute resolution mechanisms.

We point out in the response to question 6 that we cannot say conservation covenants will be tax neutral but our guidance will encourage parties to seek advice on this matter. The impact, if any, on the land, or landlord/tenant relationships, or the motivation for a covenant will vary from case to case. It is for the parties to decide if they wish to enter into a conservation covenant and the terms of any covenant but we do not think that covenants will automatically inhibit agricultural use or farm diversification. Despite concerns about the contrary one of the two tests for a conservation covenants is that it cannot be used for purposes inconsistent with the public good. We think that covenants could open up rather than close off private space, as covenants could provide for access. We recognise the very important role that the third sector plays in conservation and consultation responses lead us to expect that the sector would want to play an active part in making covenants a useful tool to deliver conservation outcomes.

Law Commission proposals

Q6 – What changes to the Law Commission proposals?

We wanted to know if, in addition to our proposed changes, there should be any other changes to the Law Commission proposals to make conservation covenants more effective. This generated responses across a number of issues. They generally fall into the following categories:

- the core elements of conservation covenants

- the content of covenants

- the interaction of covenants with other conservation or planning policies, or other statutory mechanisms

- monitoring and enforcement arrangements

- modification and discharge arrangements

- funding and incentives

The responses to this question overlapped in some cases with those given to question five on unintended consequences; question 11 on safeguards; question 12 on effectiveness of the Law Commission recommendations supplemented by our proposed amendments; and question 14 on enforcement processes. Responses were also received in this section on the arrangements for landlords and tenants and the categories of bodies which could be responsible bodies. These are dealt with under questions seven, eight and 10.

Summary of responses

The core elements of conservation covenants

The points here focused on the public-good aspect of the criteria for conservation covenants; proposed revisions to the definition of conservation purpose and of land; what qualifies as a conservation covenant; and the balance between public and private interests in conservation covenants.

Some thought ‘public good’ needed clear criteria or a legal definition and in one case that the legal definition should extend to access to land, information and justice. Others doubted if there is an adequately justiciable meaning for the general idea of “public good”. They thought it better to focus on conservation or environmental purposes to avoid interpretative issues where there could be both public and private benefit. Another view was that covenants should also be available for private benefit. Others proposed that the public-good element of the criteria for a conservation covenant should be removed, as any covenant delivering a conservation purpose would be achieving public good and to include such a requirement could increase the possibility of conservation covenants being challenged. One respondent noted that the concept of public good should be a matter for the Lands Tribunal to consider.

On definitions, some respondents proposed changes to the requirements for the “conservation purpose” of covenants. Some suggested extending conservation purpose to public access, (on the basis it would demonstrate a “public” element of “public good”) and/or that access should be restricted only where reasonable to do so. Others thought access should only occur where a landowner had expressly included it. Some suggested adding explicit references to aspects of the natural environment – e.g. the proper functioning of the land’s natural processes, conservation and enhancement of public beauty, or the creation, restoration or enhancement of appropriate habitat for species. Another suggestion was to replace “natural resources” with “natural capital” and to remove or refine “setting”, on the basis that these could extend covenants to the conservation of extractive resources or the conservation of land with no conservation value, thereby diluting the meaning of conservation purpose. Another suggestion was to add “maintain” to the definition for “conserve”, so that maintaining a certain standard of the land would qualify.

Changes were also proposed for the definition of “land”, in order to ensure it clearly caught buildings and monuments and things done in relation “to” the land rather than just “on” the land.

Most of the points on what qualifies as a conservation covenant are covered above but some raised the point about the potential conflict between different conservation objectives or different public good outcomes or conservation purposes and public good outcomes, such as covenants which are used to conserve ecosystem services outcomes rather than ecological features. Linked to this, some thought there could be times when a covenant’s objectives did not sit well with the conservation activities of others. One view was that that public engagement at the creation of the covenant would ensure that it complemented other local conservation initiatives.

The points raised about the balance between public and private interests tended to focus on changes to the monitoring and enforcement and/or modification and discharge arrangements.

Content of covenants

Some sought clarification on whether several covenants could cover the same plot of land and whether there was scope for neighbouring landowners to have equivalent covenants. There were proposals for the minimum content requirements of a covenant and views about covenants’ duration; public registration; and their transfer between responsible bodies.

Proposals for the minimum statutory contents of a covenant included: funding mechanisms; default restrictions on landowners – although these were not specified; their objectives; methods for reviewing the management plans under covenants; provisions for the responsible body to have access to the land and information; broad access to justice provisions with respect to enforcement; and acceptable processes for their discharge.

There were mixed views on the duration of covenants. Some thought there should be greater scope for flexibility so as not to tie future land users, including scope for break clauses or termination when the land is sold. Others thought covenants should be in perpetuity, in some cases with flexibility to cater for changes, such as changes required due to climate change or from developments in management practices. In the net gain scenario, some thought that a covenant should always be in perpetuity as the land that is developed will permanently lose its conservation features.

On registration, some thought details of covenants should be held on a public list, central government register and/or the Land Register. Some opposed the Law Commission proposal to register covenants on the Local Land Charges Register because the way charges are registered is felt to be very variable making it difficult to identify land, particularly in the countryside.

As for transferring covenants between responsible bodies, there was a suggestion that there should be an override to any restriction agreed by the parties on transferring the covenant. This would allow it to be transferred to another responsible body with similar objects when the current holder is wound up. Another view was that covenants should not be transferred from public bodies to private bodies or between private bodies.

The interaction of covenants with other government policies, or other statutory mechanisms

The comments in this category focused on net gain; environmental policies; existing rights or statutory provisions; and tax issues.

On net gain, some thought that covenants must deliver genuine net gain for biodiversity and they should be used only in accordance with the “planning hierarchy”. On other policies, some proposed close alignment with a future Environmental Land Management (ELM) system; and that the success of covenants should be captured in the government’s 25 Year Environment Plan monitoring and indicators as well as future Environmental Improvement Plans, proposed in a separate part of the Environment Bill. Others sought assurances that covenants could not be used as evidence to demonstrate that no public access had ever been intended - undermining subsequent claims. On tax, some sought confirmation that covenants would be tax neutral whereas others suggested that tax incentives should be used to encourage uptake or fund the delivery of covenants. Others were concerned that covenants were not used to replicate inheritance tax arrangement given in lieu of public access. Another concern queried the relationship between covenants and farm business tenancies under the Agricultural Holdings Act 1986 and the Agricultural Tenancies Act 1995.

Monitoring and enforcement arrangements

The issues raised focused largely on extending the powers of responsible bodies and of introducing greater public oversight of the monitoring and enforcement process. The proposals we received overlapped to some extent with the proposals submitted in response to question 14 on whether enforcement procedures could or should be simplified.

Some thought the procedures for dealing with breaches needed to be faster and simpler, including a “statutory duty to enforce”. Several proposed that we should extend the remit of a responsible body to allow it to have a power of entry to monitor and inspect land-management activities or a power to issue enforcement notices (or equivalents). These points are covered later under question 14.

Further proposals were offered to increase public oversight, such as transferring responsibility to a public body, with a possible role for the Office for Environmental Protection, or allowing for a public body to oversee or have a role in monitoring and enforcement activity. This is again largely covered under question 14. Linked to this, some thought that the public should have a role in monitoring and enforcement with access to the land, information and justice, which dovetailed with the view that there should be provision to allow for third party enforcement, particularly where a responsible body had not taken action.

Other proposals included requiring landowners to enforce their private law rights, for example by taking nuisance action against a neighbour when their conduct is impacting the conservation purpose of the covenant; extending the statute of limitations which applies to action taken against breaches; using injunctive relief and special performance as the primary remedies for breaches; and not allowing the Secretary of State to be both the holder of last resort and the keeper of the list of responsible bodies.

Modification and discharge arrangements

Some sought clear criteria on when covenants could be modified or discharged, including who is to be consulted before this happens. Some proposed greater public participation in the process with access to the land, information and to justice; or public notification of proposed modifications; or requiring responsible bodies to consult government agencies, or government if the responsible body was a government body. Others thought public oversight was needed for when multifunctional bodies, such as ministers or local authorities, held the covenants because of their competing interests. Some thought there should be no possibility of unilateral discharge; and another view was that impacts on landowners’ enjoyment of the land should not be a consideration for modification by the Lands Tribunal.

Funding and incentives

Several sought greater clarity on funding mechanisms for conservation covenants with suggestions including: funding from responsible bodies, developer contributions/net-gain tariff, endowments, private sector payments for ecosystem services; government grants, or tax incentives for landowners to offset both any loss of land value and management costs; and Environmental Land Management payments. Some also mentioned tax incentives to help secure uptake.

Other

Some thought the proposals should provide for covenants to stay with the land when it changes hands, so binding on future owners. Others thought the proposals should provide for covenant obligations to be both positive and restrictive, or for the parties to be able to design the covenant to suit their particular circumstances, such as to negotiate the terms on its duration or how changes might be dealt with. Another proposal was that any decision to create a conservation covenant should be a clear and conscious one of the parties. One other point sought clarification on the arrangements when a responsible body ceases to exist.

Government response

Core elements of conservation covenants

We believe that the public good concept of conservation covenants should be retained. Delivering conservation outcomes for the public good is a key aspect of conservation covenants. It is what makes them different from the existing private rights and interests, such as easements or restricted covenants. We intend to provide general guidance on public good.

On changes to the definition of conservation purpose, we do not intend to extend it to public access for the reasons given by the Law Commission in paragraphs 3.35 and 3.36 of their 2014 report. We also consider the definition is broad enough to capture the areas highlighted by respondents.

Nor do we intend to replace “natural resources” with “natural capital” or drop “setting” from the definition. We note the arguments for these changes but if the conservation purpose and public good criteria can be met, we see no reason for there not to be a covenant. On the definition of land, again we do not intend to make any changes as we consider it broad enough to capture the concerns raised. We also note that the Interpretation Act 1978 provides that references to ‘land’ are taken to include buildings and other structures.

We think the Bill and our guidance will set out sufficiently clearly what qualifies as a conservation covenant. We note the points about potential conflicts between covenant objectives, such as access and biodiversity, and the suggestion that there should be strategic oversight to ensure covenants complement or dovetail with other initiatives. Our guidance will encourage parties to be mindful of this but a responsible body will need to be satisfied with the covenant’s objectives. Ultimately, it should not become party to a covenant if it has concerns.

The balance between public and private interests was a theme that came up most noticeably in relation to the proposals for monitoring and enforcement and modification and discharge. We cover them in more detail later, but we consider the Law Commission has the balance right. These are private agreements that deliver a public good.

Content of covenants

We consider that the Law Commission proposals on duration provide the right balance between permanence and flexibility (i.e. the default is for an indefinite duration unless the covenant provides for a shorter period or where the covenant is with a tenant, in which case the covenant cannot exceed the remaining period on the lease). There is scope for the parties to agree to a shorter duration or to add provisions, such as break clauses. We do not think it right for government to restrict this flexibility in any situation, whether that be for net gain or anything else. This is consistent with the nature of covenants being private, voluntary agreements. There is also scope to modify a covenant including by referring the matter to the Lands Chamber of the Upper Tribunal when parties cannot agree. We would expect such recourse to be a last resort - with other mechanisms to resolve the dispute used beforehand.

On registration, again we support the Law Commission recommendation to record the covenant on the Local Land Charges register for the reasons they give in paragraphs 5.62 to 5.65 of their 2014 report. We will design a registration form and develop guidance to local authorities and responsible bodies to provide for consistency in registration. As to the proposal to require registration on the Register of Title (under the Land Registration Act 2002), conservation covenants would not fit easily into the scheme created by the 2002 Act as they are statutory burdens rather than proprietary interests affecting land. They fit more naturally into the scheme for local land charges (which already applies to similar kinds of statutory burdens on land). In addition, we see no reason to create a separate central government register when covenants will be on the Local Land Charges register.

As for transferring covenants between responsible bodies, we support the Law Commission recommendation for the reasons they give in paragraphs 5.98 to 5.106 of their 2014 report. This provides for a responsible body to transfer covenants to another responsible body but that the parties should also be able expressly to exclude the ability to transfer when creating the conservation covenant. We consider that approach strikes the right balance between continuity of covenants and the flexibility for parties to negotiate terms which fit their particular circumstances.

We do not think that there should be any restrictions on the number of covenants on one plot of land. If the landowner so wishes and can find responsible bodies to hold the covenants, then that is a matter for the parties to agree. Equally, we cannot see any reason why multiple neighbouring landowners should not be able to enter into an equivalent conservation covenant with one or more responsible bodies to create a larger continuous area of covenanted land.

We see no reason to alter the minimum contents of a covenant proposed by the Law Commission. They need to contain details of the parties to the covenant – name and address, explicit statement from the parties that the legislation should apply to the agreement, and the specific obligations on the parties – these can be positive and restrictive. We do not wish to be overly prescriptive on this. Covenants are private agreements and there should be flexibility for the parties to agree the content to suit their particular circumstances.

The interaction of covenants with other government policies, or other statutory mechanisms

Clarification was sought on how covenants would interact with other policies and statutory mechanisms. We consider it important to emphasise that conservation covenants are a tool which can be used in a range of scenarios. How they might be used in those scenarios will be shaped by relevant policy or legislative frameworks. In all scenarios, we consider it a matter for the parties to be satisfied that the covenant is delivering genuine conservation outcomes.

Moreover conservation covenants do not override these pre-existing rights. Pre-existing rights binding the land (whether statutory rights or private property rights) will still be enforceable by the appropriate bodies or landowners, regardless of the later creation of a conservation covenant.

We are of the view that whether conservation covenants could be used as evidence of a landowners’ intention to dedicate their land as a public right of way will depend on the individual circumstances of each case. The Law Commission’s proposals make provision for the treatment of conservation covenants where the covenanted land is compulsorily acquired for planning purposes. We do not consider there to be implications from conservation covenants for farm business tenancies under either the Agricultural Holdings Act 1986 or the Agricultural Tenancies Act 1995.

As for tax, we cannot guarantee covenants will be tax neutral. We will include in guidance that landowners should seek specialist advice on potential tax implications. The question of tax breaks to incentivise uptake is covered in the later section on funding

Monitoring and enforcement arrangements

We do not intend to provide for responsible bodies to have a statutory right of entry, nor do we want to give them the power to issue enforcement notices, or equivalents, nor do we intend to transfer the monitoring and enforcement functions to a public body, such as the Office for Environmental Protection. We agree with the Law Commission that the responsible body should secure a right of entry to the covenanted land if they consider it important for their monitoring and enforcement role. To transfer the monitoring and enforcement function to a public body, or to give responsible bodies a power to issue enforcement notices, would move covenants out of the private voluntary sphere into the public sphere. This runs counter to our overall approach.

We do not think that the public should have a role in monitoring and enforcement with access to the land, to information and to justice, nor do we think there should be provision for third parties to take enforcement action when a responsible body does not do so. We agree with the Law Commission that it is the role of the responsible body to undertake monitoring and enforcement and that they would be expected to perform that role diligently. All responsible bodies will be assessed for their suitability against published guidelines at the time of their application and can face being de-listed when they are not fulfilling their role.

We do not intend to provide for the parties to be able to take enforcement action against neighbours whose actions on their own land impede delivery of a covenant’s objectives. Conservation covenants are private agreements and the neighbour is not a party to the covenant. Therefore if the objectives of the covenant cannot be delivered because of a third party, the covenant will have to be modified.

We also see no reason to extend the limitation period from six years to 12 for actions for breach of a covenant. In practice, responsible bodies should be monitoring their covenants on a regular basis. Equally, we see no reason to specify that injunctive relief and special performance should be the primary remedies for breaches. We do not wish to fetter the discretion of the courts to determine the most appropriate remedy.

We have considered the concern that the Secretary of State, as both holder of last resort and the keeper of the list of responsible bodies could, potentially, bring all covenants to an end simply by de-listing the responsible bodies and not taking over active responsibility for the covenants. We see this as an extremely remote possibility that would face significant political pressure and might be challenged by way of judicial review.

Modification and discharge arrangements

We consider that the Law Commission proposals set out clearly the process for modification and discharge of a conservation covenant. The parties are free to agree to modify or discharge any or all of the covenant’s obligations and where they cannot agree they can ultimately refer the matter to the Lands Tribunal. The Law Commission set out in schedule 1 of their Bill the matters which the Tribunal may wish to consider. We would expect the parties to use the Tribunal only as a last resort and will encourage them through guidance to utilise alternative dispute resolution mechanisms.

We do not intend to introduce requirements for greater public engagement in the modification and discharge process. To do so would take conservation covenants out of the private sphere and could adversely affect uptake of covenants. We expect responsible bodies to act responsibly and diligently, whether they are public bodies with competing interests to balance, such as the Secretary of State or local authorities, or others.

On unilateral discharge, this would only be possible if expressly provided for in the terms of the covenant. This is consistent with the flexibility to allow parties to design their covenant to suit their circumstances. We would, however, expect such provisions to be the exception rather than the rule.

We also intend to retain the landowners’ right to enjoyment of their land as a factor that the Lands Tribunal can consider in modification and discharge cases. The Law Commission included this to provide for unforeseen circumstances which could undermine the feasibility of delivering obligations. As covenants will generally be very long term we think it important to build in flexibility for changes that are a product of time and make it impracticable to continue with the obligation.

Funding and incentives

There will be a cost to both the landowner and the responsible body in delivering and monitoring the delivery of covenant objectives, but these are private agreements that are entered into voluntarily and so the associated costs are taken on voluntarily. In some situations these costs might be more than offset by income generated where the landowner receives an income – e.g. for managing land to deliver an ecosystem service or as compensatory habitat in a net gain scenario. In some cases, conservation covenants may be profitable to both the landowner and the responsible body. There is no direct public funding provision for covenants, so both parties will need to be satisfied that resources will be available to deliver the conservation outcomes. We have no plans to change tax arrangements to incentivise uptake.

Other

We consider that the Law Commission proposals already provide for covenants to stay with the land when it changes hands; for the obligations to be both positive and restrictive; for the parties to be able to design covenants to suit their particular circumstances; for the parties’ decision to create a covenant to be a clear and conscious one; and for when a responsible body ceases to exist by transferring the covenant to another responsible body or if that is not possible, to the Secretary of State as holder of last resort.

Tenants and landlords

Question 7a: Should tenants be able to enter into conservation covenants?

Question 7b: If so, do you agree that the qualifying threshold for the remaining length of a lease should be set at a minimum of 15 years?

Question 7c: If not, what level would you set it at and why?

Question 8a: Should tenants be required to secure the agreement of the freeholder before entering into a covenant?

Question 8b: If not, what is the basis for your view?

Question 8c: Should freeholders be required to secure the consent of a tenant before entering into a covenant when the land affected is leased?

We used these questions to seek information on whether covenants should be available to tenants and, if they should, whether the qualifying criteria should be stricter than proposed by the Law Commission. This was one of the proposed amendments to the Law Commission proposals we consulted on. We have grouped these questions together.

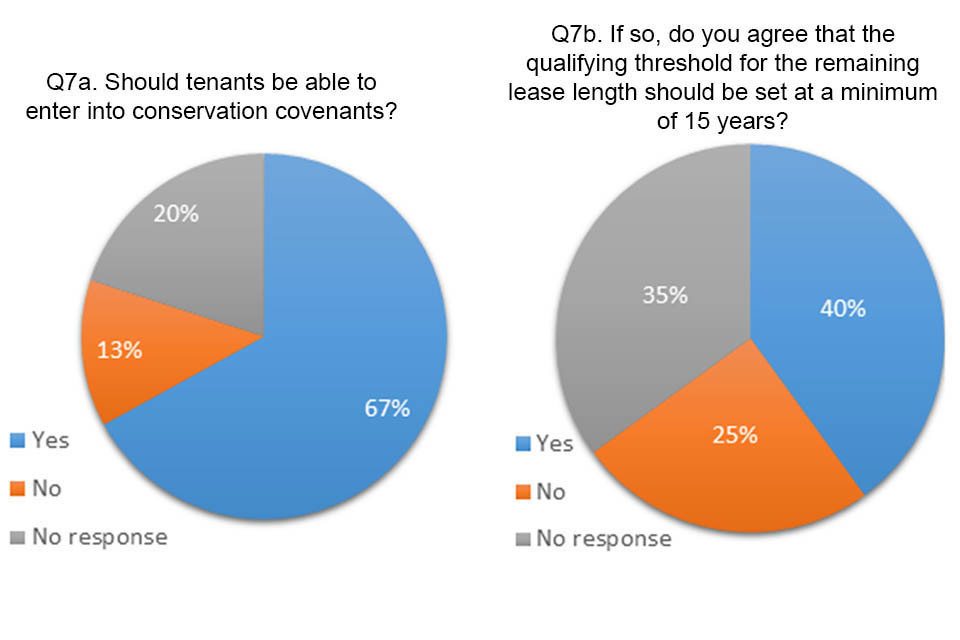

Summary of responses

The pie charts show that 75 (67%) of responses support tenants being able to enter into covenants; 45 (40%) agree that tenants should have at least 15 years left on their lease before they can do so; and that 77 (69%) believe tenants should have to first secure the agreement of the landlord. The pie charts also show that 62 (56%) consider landlords should also be required to secure the agreement of tenants before they enter into covenants.

Pie charts showing answers to question 7a and b. 67% agreed that tenants should be able to enter conservation covenants, Of those that agreed, 40% thought the lease length should be set at a minimum 15 years,

A number of key points were raised. Several noted that a tenancy agreement covers the relationship between the landlord and tenant and sets out what a tenant can and cannot do on the leased land. Some felt that introducing qualifying thresholds for covenants would add an unnecessary layer of complexity. Any threshold linked to the period of time left on the lease was also considered to be arbitrary. Some mentioned that there is a statutory threshold for registering tenancies, (for any that are more than seven years in duration), and some thought this might be used as the appropriate qualifying threshold. There was also a view that the parties should be free to enter into covenants, even very short covenants, when they are satisfied that it can deliver lasting conservation outcomes.

Pie charts showing the answers to question 8a and c. 69% agreed tenants should get the freeholder's agreement before entering into a covenant. 56% agreed that freeholders should get the tenants consent before entering into a covenant.

Government response

We have carefully considered the arguments made and intend to provide for tenants to be able to enter into conservation covenants. We note that tenants’ interests in land can be virtually equivalent to those of landlords, with some having very long leases. After consideration of consultation responses, we do not propose to set a threshold of 15 years remaining on the lease as a qualifying criterion. We agree that it is for the parties to be satisfied that whatever time left on the lease is sufficient for them to secure the lasting conservation outcomes that they wish to deliver. Tenants will, however, have to have a lease of more than seven years with some time remaining on the lease. This is consistent with the proposals from the Law Commission. The seven-year threshold is consistent with the limit for mandatory registration of leases under legislation.

After consideration of consultation responses, we do not believe it is necessary for our legislation to require either the tenant or landlord to secure approval from each other to enter into a covenant. This is also consistent with the proposals from the Law Commission. The tenancy agreement sets out the tenant’s rights to use the land and tenants cannot act beyond the limits of their powers and legal obligations. A landlord who enters into a conservation covenant would not be able to discharge the obligations under the covenant if they were to involve a breach of the lease. To introduce an additional blanket requirement of consent would stray into a private matter between the landlord and tenant, and would be out of place in cases in which, for example, a tenant can grant other rights binding a leasehold without needing the landlord’s consent. It would also create an additional due diligence burden on the responsible body to ascertain if a lease had been granted and whether consent had been secured.

Public oversight - annual reports

Question 9a: Should public oversight provisions require responsible bodies to provide details of the location and headline conservation objectives of conservation covenants held by them?

Question 9b: If not, what would you propose and what is the basis of your proposed alternative?

We used these questions to gather views on our proposals for additional public oversight provisions should be covered through the annual reporting requirements and, if not, what should be captured. This was another one of our proposed amendments to the Law Commission proposals.

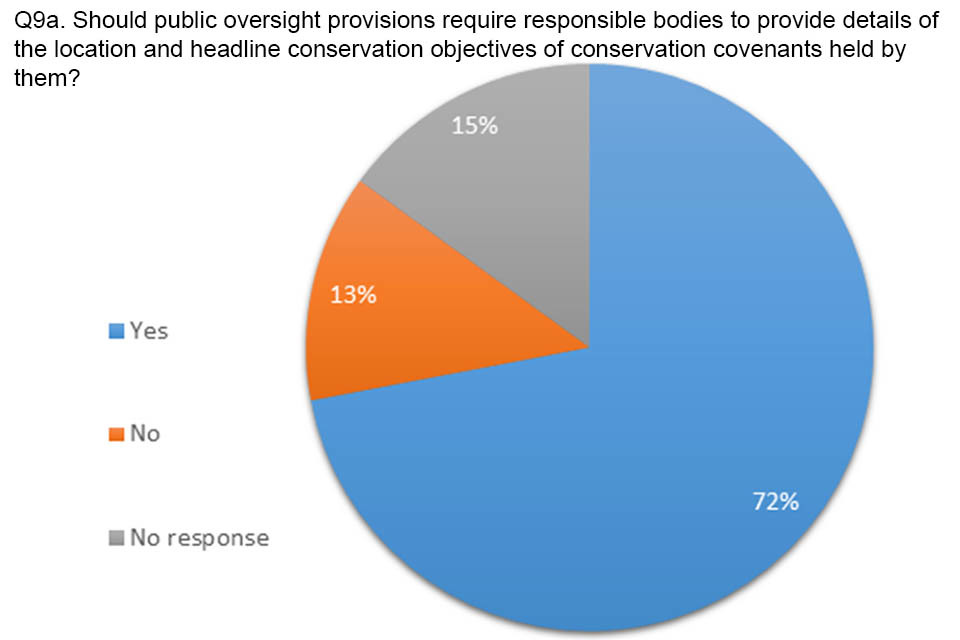

Summary of responses

The pie chart shows that 81 (72%) of responses supported the proposal to extend the annual reporting requirements. The key points raised were that the additional information would be important to assess the effectiveness of covenants including their contribution to the implementation of the measures in 25 Year Environment Plan; that the local land charges register will hold information on the location of the covenants, so gathering this information was an unnecessary burden; and that capturing any information at all was not consistent with the private nature of covenants and therefore responsible bodies should only be encouraged to provide it on a voluntary basis unless the covenant was being funded with public money.

Pie chart showing response to question 9a. 72% agreed that responsible bodies should provide location and headline conservation objectives for any conservation covenants held.

Government response

We want to strike the right balance between the private nature of covenants and the public good they will deliver. The spectrum of views on public oversight is wide. We intend to require annual returns from responsible bodies on the number of covenants they hold and the extent of land covered by those covenants, as proposed by the Law Commission. This will allow us to assess the uptake of covenants.

We will encourage responsible bodies through guidance to provide information voluntarily on the progress and successes of their covenants. We consider responsible bodies will want to do this, as they will have been selected using guidelines which will demonstrate a commitment to conservation. Our reporting template will have a section to capture this information.

We intend to include just one further element. Covenants will generally involve a very long-term approach, and we think it is important to have the flexibility to gather additional information that may prove to be important in the future. Our legislation will therefore provide for the Secretary of State to be able to use secondary legislation to specify any additional information required. We think these reporting arrangements strike the right balance between the private nature of covenants and the public good they will deliver.

We accept the point that information about the location of covenants will be recorded on the local land charges register. We see no need to require reports on covenants to capture information when public money is involved, as there will be no direct public funding provision for covenants. Where covenants are used to support the delivery of conservation schemes drawing on public money, reporting should be through what is needed for those funding mechanisms.

Responsible bodies

Question 10a: Should for-profit bodies be able to hold conservation covenants?

Question 10b: Should there be additional mechanisms introduced for for-profit bodies which provide assurances that the covenants they hold are delivering conservation outcomes for the public good? If so, what mechanisms would you suggest?

We used these questions to explore views on whether for profits should be able to become responsible bodies and, if they should, whether they should be subject to any further checks and balances to ensure their covenants are delivering for the public good.

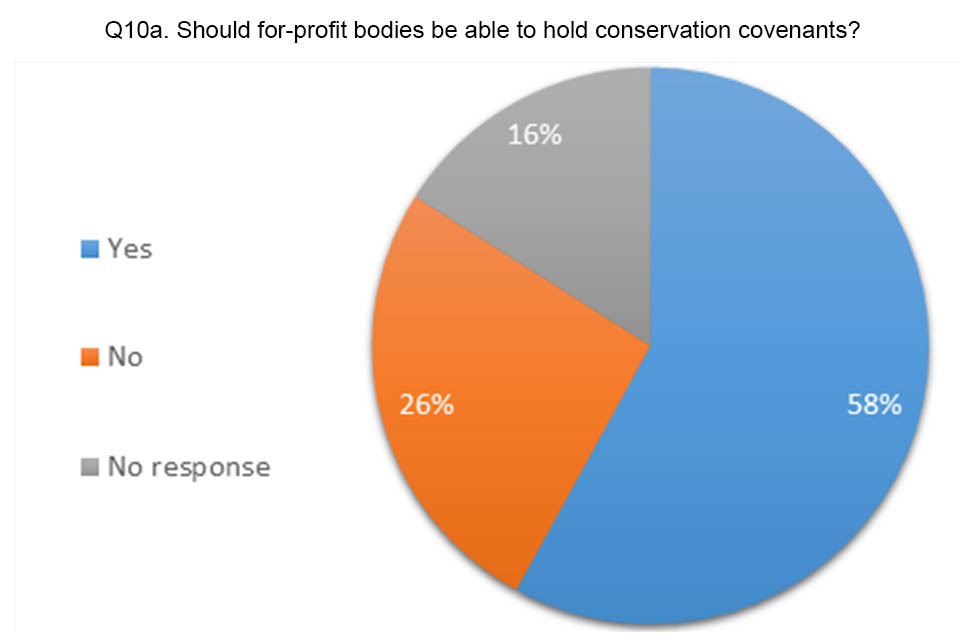

Summary of responses

The pie chart shows that a majority of respondents 64 (58%) were supportive of for-profit bodies holding conservation covenants but a large minority 29 (26%) expressed concerns.

Pie chart showing answers to question 10a. 58% agreed for-profit bodies should be able to hold conservation covenants

The key points raised related to monitoring of for-profit bodies holding conservation covenants, including additional regulation or oversight by public bodies such as Natural England, and prior approval by the Secretary of State to allow for-profit bodies to hold conservation covenants. Motivation for this additional scrutiny stemmed primarily from views that such bodies will not have conservation as their primary purpose, so may face a conflict of interest, whereas charities have different drivers and are already regulated by the Charities Commission.

Public oversight

Many of those who considered that some form of additional safeguard would be necessary proposed a system of monitoring, and/or regulation by an independent or public body, such as Natural England or the Environment Agency, and generally requiring a level of transparency in the operation of covenants held by for-profit bodies. This included a suggestion of unannounced auditing by a public body to ensure that for-profit bodies are fulfilling their side of a covenant and the relevant conservation purposes.

Several felt that any for-profit body should be approved by the Secretary of State before being allowed to hold a conservation covenant, citing criteria such as longevity of purpose, and the ability and funds to monitor and enforce the covenant. One suggestion was that such decisions by the Secretary of State should be open to scrutiny to allow challenge where decisions do not appear to be in the public interest.

Financial and other penalties

In conjunction with the proposed additional scrutiny, several felt that failure to achieve outcomes of a conservation covenant should result in fines for the for-profit bodies, and potentially the forfeiture of the right to hold covenants in future. Some respondents were wary of the possibility of for-profit bodies claiming damages for breach of a covenant.

Some suggested that for-profit responsible bodies should be required to feed some of the profit made from a conservation covenant back into the land, or for other conservation purposes or projects. Related to this, one suggestion was that there should be a restriction on the use of damages by for-profit responsible bodies, limiting the use of income from damages to conservation purposes; whereas such a restriction was not felt to be necessary for charities which put all their funds towards charitable objects.

Multi-party provisions

Some thought that for-profit bodies should be required jointly to hold covenants with bodies which have conservation as their primary purpose. It was felt that this mechanism would ensure that any changes made are environmentally justifiable. It was also thought that multi-party agreements are more enduring. Another suggestion was that for-profit bodies may create a charity, which in turn could act as a responsible body.

Government response

In line with our consultation proposal, we intend to allow for-profit bodies to apply to hold covenants. We consider there are for-profit organisations with expertise in land management that can deliver conservation outcomes. We will require these bodies to be designated by the Secretary of State (through regulations). We will draw up guidelines which will be used by the Secretary of State to determine which organisations can become responsible bodies.

We have considered the arguments in consultation responses that for-profit responsible bodies should be subject to additional scrutiny from a public body, but do not find that there are compelling reasons to do so, for two primary reasons. Firstly, bodies such as Natural England and the Environment Agency may become responsible bodies in their own right, and we do not consider it appropriate that one responsible body oversee another in obligations it has taken on in a private agreement with a landowner. Secondly, public oversight of conservation covenants would take conservation covenants out of the voluntary, private sphere and into the public sphere.

We have also considered the concerns raised with regard to the potential conflict of interest, transparency, and accountability of for-profit bodies. We believe that the selection guidelines coupled with the provision for the Secretary of State to de-list any responsible body that is not fulfilling their role provides sufficient safeguards. Further, we do not anticipate that responsible bodies of any type will, as a rule, fail to comply with their responsibilities, as they will have voluntarily applied to become a responsible body and entered into covenants with landowners.

We consider that the Law Commission proposals already allow for more than one responsible body to be a party to a covenant. We do not intend to make it a requirement for for-profits to include another body which has conservation as its primary purpose in their covenants. We note that in order to be eligible for designation as a responsible body, at least one of the for-profit body’s functions must be, or be connected to conservation. If a for-profit wanted to create a charitable arm, and for that to apply to become a responsible body, it could do so.

Safeguards against misuse

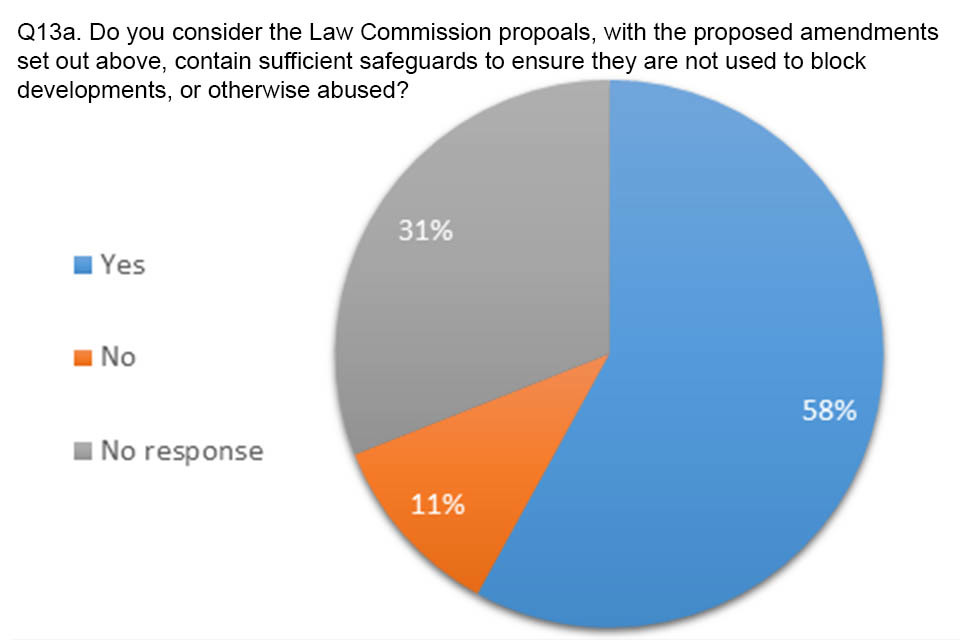

Question 11a: Do you consider the Law Commission proposals, with the proposed amendments set out above, as containing sufficient safeguards to ensure they are not abused?

Question 11b: If not, what changes would you make?

We wanted to know if the Law Commission proposals with our amendments were sufficient to ensure conservation covenants were not misused. The majority of consultees thought they were 46 (42%) but a sizeable minority 31 (28%) expressed concerns. There was a lot of overlap in the points raised about potential misuse of covenants and those raised in respect of changes to the Law Commission proposals and/or our proposed amendments to them.

Summary of responses

The main points raised related to the safeguards associated with monitoring and enforcement arrangements; the modification and discharge arrangements; the core elements of covenants; the interaction with other policies and mechanisms; and responsible bodies.

Pie chart showing answers to question 11a. 42% agreed that there were sufficient safeguards in the Law Commission proposals

Monitoring and enforcement

Some thought that strengthening the monitoring and enforcement processes would provide greater safeguards against misuse. Suggestions focused on greater public participation in the process with a possible role for the Office for Environmental Protection; for third parties to have a role, particularly when responsible bodies do not take action; for publication of information on monitoring and enforcement; for more oversight of for-profit responsible bodies by statutory bodies; and for more public oversight when covenants are underpinned by public money.

Others simply felt that responsible bodies will need to perform properly and fulfil their obligations under covenants with safeguards to ensure they do; or that the procedures for resolving breaches needed to be determined. Others raised concerns about the possible misuse which affects landowners. A particular concern was if enforcement action was taken against a landowner when the breach was the result of a change to accepted practices or policies.

Modification and discharge arrangements

Some thought a fast inexpensive and robust mechanism would provide a safeguard against misuse of these arrangements, whereas others thought the procedures for resolving disputes needed to be determined between the parties. Some held the view that criteria needed to be established for when the parties or the Tribunal could modify or discharge obligations in a covenant, with others thinking that a covenant should not be discharged in a net gain scenario. Some thought that there needed to be a greater public role in the process – for example, with the public able to contest cases at the Lands Tribunal. There were conflicting views about the breadth of the role of the Tribunal with some thinking it should have wide discretion, whereas others thought there should be greater restrictions on its actions. There was one suggestion that a replacement responsible body should be able to deputise at a Tribunal if the relevant one cannot attend to contest the dispute.

Core elements

Some thought that greater clarity over what qualifies as a conservation covenant together with clear criteria covering the circumstances when covenants might be used and what should be in a covenant would act as a safeguard against misuse. Some thought there was a need for a clear definition of public good. Again there were views that the definition of conservation purposes should extend to public access.

Some thought greater public participation in the whole process would provide safeguards against misuse. Suggestions included engaging parish councils and statutory bodies at creation stage; and greater public access to information. There was also a concern that future government policies could undermine conservation covenants and that safeguards were needed to guard against this. There was a view that safeguards were needed to protect landowners against public access to their land.

Interaction with other policies and mechanisms

Some thought that there needed to be greater clarity over the interactions to avoid misuse. The key area of concern focused on how covenants would fit with the planning regime. Some thought covenants could be used to undermine planning controls and facilitate damage to important habitats. Others were concerned that covenants could be too easily overridden to allow for development and/or that development should not be permitted on covenanted sites in a net gain scenario.

Other concerns were that covenants should not be used to inhibit statutory undertakers performing their statutory functions and that covenants should not be agreed in national parks with obligations which run counter to the statutory purposes of these parks.

Responsible bodies

The key point raised was that safeguards need to be designed into the guidelines for these bodies to ensure that, if for-profits were to be eligible to apply to become responsible bodies, that they do not abuse their position when faced with conflicting interests.

Government response

We consider that the monitoring and enforcement arrangements are clearly and sufficiently set out. As with any agreement, the parties will monitor and, where necessary, enforce compliance of each other’s respective obligations - the responsible body monitoring the landowner’s obligations and the landowner monitoring the responsible body’s. A breach will occur when an activity is carried out contrary to a restrictive obligation and when it is not carried out in respect of a positive obligation. Breaches can, ultimately, be referred to the courts, if the matter cannot be resolved by the parties, or through alternative dispute resolution. We would anticipate that court action would occur very rarely owing to the voluntary nature of conservation covenants and the fact that successor owners would acquire the land in the knowledge that it has a conservation covenant on it.

We see no need to give the public a role in the enforcement process. We have covered this in other parts of the response but in essence the responsible body will have been designated by the Secretary of State and can be delisted if they do not perform their functions. We also believe that increasing the role of the public, whether through statutory bodies, third party enforcement or publication of information, would move conservation covenant away from the private voluntary sphere into the public sphere, which runs counter to their purpose. We do not consider that the Office for Environmental Protection should have a role in enforcing and monitoring individual conservation covenants.

Where covenants are used to support the delivery of conservation schemes drawing on public money, reporting should be through what is needed for those funding mechanisms. There is no dedicated public money that accompanies conservation covenants.

We do not think any further safeguards are needed to ensure responsible bodies perform their functions. We consider that they would do them diligently as they have chosen to be a responsible body and decided that any covenants they hold would be ones that they wish to see delivered. Ultimately, if they were not to undertake their role, they face the sanction of being de-listed.

We would expect responsible bodies to act in a reasonable manner. We would not expect covenants generally to generate adversarial sentiments, as the parties will have entered into them voluntarily or acquired land knowing about the covenant. If a breach was a product of changing policies or practices and the landowner thought the obligation should be modified or discharged in the circumstances, they can, ultimately, apply to the court to secure an order for the matter to be referred to the Lands Tribunal for a decision. We would expect that to happen very rarely.

We consider that the arrangements for modification and discharge as proposed by the Law Commission are fair, fast and robust. The two parties can agree to modify or discharge in very quick order. The responsible body will provide the assurance that such a course of action is appropriate. Where the parties cannot agree the process will necessarily be longer as arguments need to be heard by an independent body. That might be through alternative dispute resolution if the parties agree but ultimately it can be by the Lands Tribunal.

We do not propose to set criteria for when the parties or additional criteria for when the Tribunal can modify or discharge covenant obligations. It is a matter for the parties to decide. This is consistent with the private, voluntary nature of conservation covenants. In the case of the Tribunal, our proposals already set out the factors which the Tribunal can have regard to when exercising its power to modify or discharge, and these factors will be set out in the Bill. We do not propose to increase the public role in the process for the reasons given for monitoring and enforcement above.

It would not be appropriate for a ‘replacement responsible body’ to be able to deputise for another at the Lands Tribunal. Another responsible body would not be a party to the covenant so would have no locus in the proceedings.

We have covered all of the points on core elements of covenants in other parts of this response, particularly in respect to question six on changes to the Law Commission proposals.

We do not think it necessary to build in safeguards against future government policies. Such policies will have a public mandate. They will need to be balanced against the public good being delivered through conservation covenants.

We also do not consider that there need to be additional safeguards to protect landowners against public access to their land. Conservation covenants are entirely voluntary. Landowners do not have to enter into them and if they do, they do not have to provide for access to their land. In some cases, public access will have a neutral impact on conservation but, in some cases, it could prove harmful.

We do not consider additional safeguards are required in respect of the interaction with other policies and mechanisms. How conservation covenants are used in the planning regime will be shaped by planning and development land use policies. These policies require the authorities to balance competing priorities including their role on conservation. They are subject to a number of checks on their work, such as access to information schemes, judicial review, and local authorities are democratically elected bodies. These provide the safeguards against misuse.

We also do not consider that additional safeguards need to be introduced to protect the interests of statutory undertakers or others with statutory interests in the land, such as National Park Authorities. As mentioned in other parts of this consultation response, landowners need to take account of existing third party rights when agreeing conservation covenants. Conservation covenants do not override these pre-existing rights. Pre-existing rights binding the land (whether statutory rights or private property rights) will still be enforceable by the appropriate bodies or landowners, regardless of the later creation of a conservation covenant.

On guidelines for designating responsible bodies, we will develop these in conjunction with stakeholders and set them out in guidance.

Simple and practical to use

Question 12a: Do you consider the Law Commission proposals, with the proposed amendments set out above, as simple, practical and capable of delivering lasting conservation outcomes?

Question 12b: If not, what changes would you make to them?

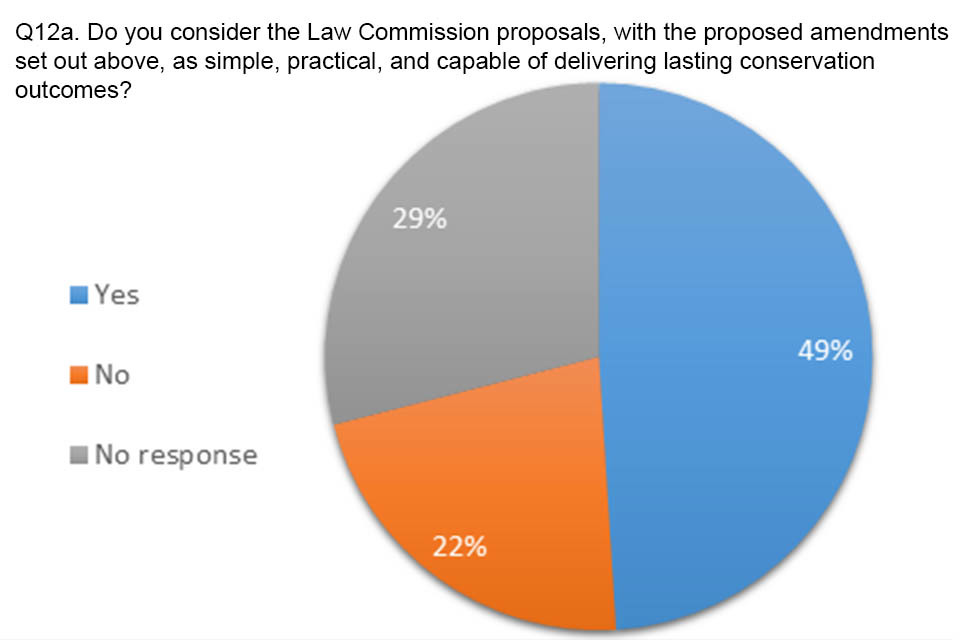

We sought views on whether the Law Commission proposals with the proposed amendments were simple, practical and capable of delivering lasting conservation benefits. The pie chart shows that the majority of consultees who expressed a view 54 (49%) thought they were but a large minority 25 (22%) thought they were not.

Summary of responses

The main points raised echoed, in many instances, those made in respect of question 6 on changes to the Law Commission proposals.

Pie chart showing answers to question 12a. 49% agreed that the Law Commission proposals were simple, practical and capable of delivering lasting conservation outcomes

They have been put into the following categories:

- the core elements of conservation covenants

- the content of covenants

- monitoring and enforcement arrangements

- modification and discharge arrangements

- the interaction of covenants with other conservation or planning policies, or other statutory mechanisms

- funding and incentives

- guidelines for responsible bodies

- public oversight – annual reporting

Core elements of scheme

The concerns around the public-good limb of the criteria for covenants; the definition of conservation purpose, including the issue of public access; what qualifies as a conservation covenant; and the balance between public and private interests in conservation covenants were raised again. There were also suggestions to broaden the scope of conservation covenants by allowing any organisation to hold them, not just responsible bodies, and that covenants should be allowed to deliver private as well as public good.

Content of covenants

The issue of duration and flexibility came up again. Clarification was also suggested for how and when the management obligations are defined, how they are managed and monitored.

Monitoring and enforcement arrangements

Greater public involvement in monitoring and enforcement including a possible role for the Office for Environmental Protection; and increasing the limitation periods for action against breaches came up again, as did concerns about conflicts of interest for those responsible bodies with multiple functions undermining effective enforcement action. Other points included: greater protection for landowners when responsible bodies failed to perform their functions or where breaches were a result of unforeseen issues or changing policies or practices; and a proposal that de-listed responsible bodies should still be able to enforce obligations.

Modification and discharge arrangements

Greater clarity on the process and greater public engagement came up again. There were suggestions that the Lands Tribunal should have authority, where necessary, to secure expertise from others to help them reach a decision; that the Tribunal should also be able to consider responsible body rights in a covenant; and that the modification and discharge arrangements should align with those for restrictive covenants.

On the interaction of covenants with other conservation or planning policies, or other statutory mechanisms: funding and incentives, guidelines for responsible bodies; and public oversight – annual reporting - no new points were raised. Please see responses given for questions 6, 9 and 10.

Government response

Core elements of the scheme