Call for evidence on commercial rents: responses and analysis

Updated 4 August 2021

Introduction

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic the government’s key policy aim was and remains to preserve otherwise viable businesses and the millions of jobs that they provide. To this end the government introduced measures to protect tenant businesses from the threat of eviction or insolvency as a result of being unable to pay their rent while essential restrictions on trading were in place to combat the pandemic.

These measures have encouraged many landlords and tenants to come together to agree to share the impact of the pandemic in fair and sustainable ways with landlords agreeing to waive or defer some or all accumulated rent debt to enable tenant businesses to survive, preserve jobs, and make their contribution to the recovery. However, there remain many landlords and tenants that have been unable to reach agreement, and the level of accumulated rent debt threatens the existence of many tenant businesses and the millions of jobs that they support.

To assess the true situation on the ground the government launched a call for evidence inviting landlords, tenants, and other interested parties to describe their experience in seeking to negotiate settlements of rent debt during the pandemic. The call for evidence also sought views on a number of options for withdrawing or replacing the existing tenant protection measures as we embark upon the recovery.

Following careful analysis of the more than 500 responses received to the call for evidence, the government announced on 16 June that legislation will be introduced during this parliamentary session to support the orderly resolution of rental payments accrued by commercial tenants during the pandemic.

New legislation will ringfence rent debt accrued from March 2020 for tenants who have been impacted by COVID-19 business closures until restrictions are removed for their sector and introduce a system of binding arbitration to be undertaken between landlords and tenants. This is to be used as a last resort, after bilateral negotiations have been undertaken and only where landlords and tenants cannot otherwise come to a resolution.

Ahead of the system being put in place, we will publish the principles which we will seek to put into legislation in a revised code of practice, to allow landlords and tenants time to negotiate on that basis.

Section 82 of the Coronavirus Act 2020, which prevents landlords of commercial properties from being able to evict tenants for the non-payment of rent, will continue until 25 March 2022 unless legislation is passed ahead of this, in order to provide sufficient time for this new process to be introduced. Government is clear that those tenants who have not been affected by closures and who have the means to pay, should pay. Additionally, government expects commercial tenants to begin paying rent as per their lease from the point of restrictions being lifted for their sector.

As soon as legislation is passed, the moratorium on evictions will only apply to ringfenced arrears. This includes rent debt accrued from March 2020 by commercial tenants affected by COVID-19 business closures until restrictions for their sector are removed. This means that landlords will be able to evict tenants for the non-payment of rent prior to March 2020 and after the end of restrictions for their sector and who have not been affected by business closures during this period.

The responses to the call for evidence have been used to inform the government’s next steps. The two most favoured options were to allow the tenant protection measures to lapse on 30 June 2021 (89.5% of responding landlords were in favour of this option) and to introduce a scheme of binding arbitration to resolve rent debt (66.3% of responding tenants were in favour of this measure).

Overall, 57.3% of respondents were against letting measures expire on 30 June, whilst a significant group (33.7%) were in favour of it. 49.2% of respondents were in favour of binding adjudication, whilst only 27.4% were against it.

Recognising the clear dichotomy of views expressed by landlords and tenants the government considered the options in the light of its original policy objective; to preserve viable tenant businesses and the millions of jobs that they support. This has led to the decision to bring forward legislation to ringfence rent debt accumulated during enforced closures and to set out a process of binding arbitration to be undertaken between landlords and tenants that are still unable to reach agreement on rent debt.

The responses to the call for evidence indicate that 84% of respondents thought that binding arbitration would either not impact employment (44%) or increase employment (40%). This compares with only 40% of respondents if measures were allowed to lapse on 30 June (of which 29% reported “no impact” and 11% an increase). UK Hospitality estimates that around 332,000 jobs could be lost in the hospitality sectors if measures expired on 30 June – about a sixth of the remaining workforce of 2 million.

The government’s decision also acknowledges the fact that a number of large commercial landlords, together with sector representative bodies from both landlords and tenants, have recently published proposals for binding arbitration and the ringfencing of rent arrears independently of the call for evidence.

Findings

The call for evidence ran from 6 April to 4 May 2021. There were 508 respondents to this call for evidence. A summary of the responses received to each group of closed questions and emerging themes captured from an analysis of open questions can be found in the sections below.

1. Profile of respondents

The opening questions in this call for evidence captured information relating to the profile of respondents. The two largest groups of respondents were Commercial Tenants (or “tenants”) and Direct Investors/Landlords/Commercial property owners (or “landlords”). Collectively these tenants and landlords represent just over 86% of all respondents. There were 306 and 133 respondents in these two groups respectively.

There were “Other” respondents to for call for evidence (66 respondents of which 50 stated their organisation type); lenders (2 respondents) and indirect investors (1 respondent) made up the remainder of responses.

Others comprised of representative organisations (13 respondents), surveyors/agents (13 respondents); legal (12 respondents); property managers (6 respondents); debt enforcement (5 respondents); and mediation / alternative dispute resolution (1 respondent).

The remainder of this section focuses on the profile of tenants and landlords capturing a number of economic characteristics summarised in responses to closed questions (4-18). Limited information will be provided on the other groups.

1.1 Profile of tenants

Size

231 tenants (or about 77% of tenants) that responded to the call for evidence are Small or Medium Enterprises (SMEs) i.e. businesses with between 0 and 249 employees. Table 1 provides a summary of the size of respondents based on employees and annual total annual turnover. Size classifications are based on ONS definitions, based on the number of employees. There were 5 tenants that did not provide employee numbers.

Table 1. Profile of tenants (by number of employees and turnover)

| Size | Respondents (number) | Employees (number) | Annual turnover (Total, £ millions) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small | 192 | 2,675 | £229.0 |

| Medium | 39 | 3,995 | £271.2 |

| Large | 70 | 650,593 | £81,079.9 |

| Total | 301 | 657,263 | £81,580.2 |

Main business activity

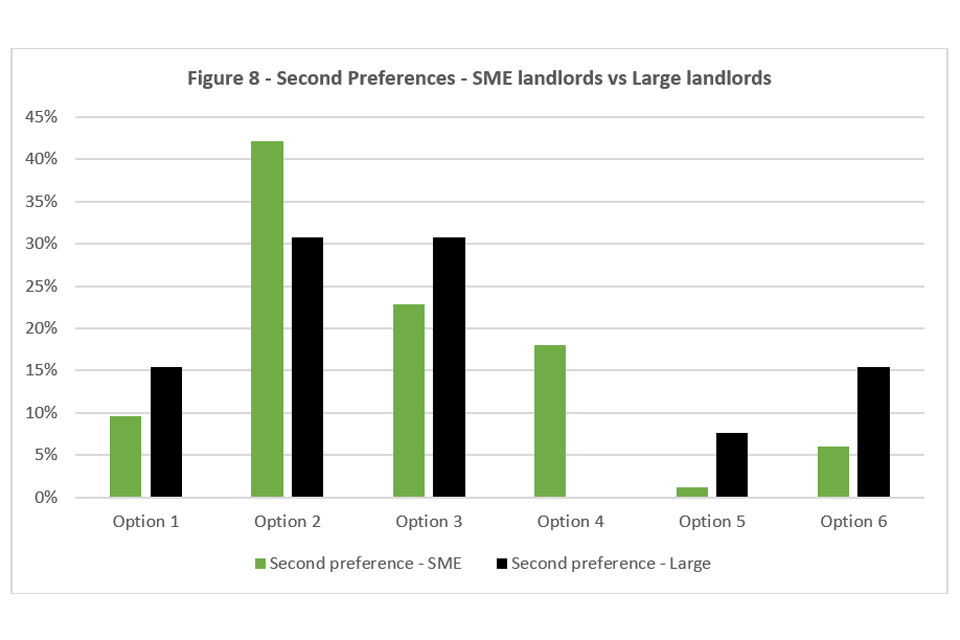

Respondents were also requested to provide 5-digit Standard Industrial Classification Code (“SIC” code) to characteristic their main business activity. Figure 1 summarised the top 10 SIC codes of tenant that provided this information. Most respondents were public houses (69 respondents), licenced restaurants (54) and fitness facilities (26).

1.2 Profile of landlords

Size

108 landlords provided a response to these questions relating to employment and turnover. Some 87% of respondents are SMEs. The total number of respondents, employees, and annual turnover by size of business is shown in the Table 2 below. There were 9 direct investors/landlords that did not answer the questions relating to number of employees.

Table 2. Profile of landlords (by number of employees and turnover)

| Size | Respondents (number) | Employees (number) | Annual turnover (£ millions) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small | 90 | 749 | £570.8 |

| Medium | 18 | 1,980 | £1,317.2 |

| Large | 16 | 74,451 | £21,223.5 |

| Total | 124 | 77,180 | £23,111.5 |

Location of premises

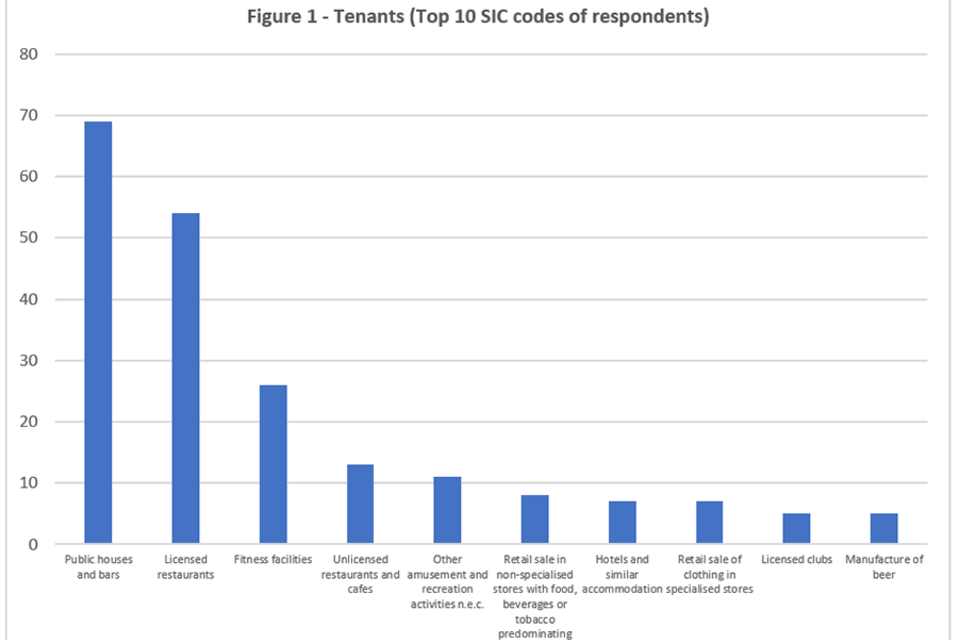

43% of landlords’ premises are in Greater London. While for tenants, 22% of their leased premises are in this region. Figure 4 summarises the regional breakdown of the percentage of premises owned by landlords (or leased, in the case of tenants).

Vacancy rates

A total of 117 landlords provided information on vacancy rates. The vacancy rate of respondents ranged from 0 – 100%.

The average vacancy rate across all respondents is 7.6%. Based on the SIC code information provided, the highest average vacancy rate (26%) is for businesses engaged in activities of property unit trusts. The average vacancy rate is higher for large landlords (8.7%) than for SMEs (7.4%).

1.3 Profile of other respondents

Of the ‘Other’ respondents, 61 out of 69 provided information about their employee numbers and turnover. Based on the employment figures, 45 of these respondents are SMEs with a total annual turnover of approximately £120m. 16 respondents are large businesses (i.e. with 250 or more employees), with total annual turnover of £2,994m.

Based on the SIC code information provided, the main business activities of this group of respondents are management of real estate (18 respondents); activities of business and employers membership organisations (8 respondents); solicitors (8 respondents); real estate agencies (5 respondents); and activities of collection agencies (3 respondents).

Two respondents in this category are lenders comprising of a relatively small lender in specialist funds and a very large non-bank CRE lender, with the value of investments in excess of £8,243m.

2. Current trends

The following section refers to the questions relating to the rent negotiations that have taken place, as well as the current moratorium and code of practice. The common outcomes, types and levels of concessions agreed and the ability to repay rent arrears are discussed at length. Additionally, the effectiveness and impacts of the current moratorium, the effectiveness of the code of practice and necessary changes to the code are explored. This should help to create a counterfactual in order to frame the discussion of options that follows.

2.1 Rent negotiations

Amount owed

The total rent tenants claim to owe is £571,107,558. The total rent landlords claim they are owed is £1,732,084,445.

A breakdown of rent arrears of tenants is shown in Table 3 (by amount owed) for the top 10 SIC codes. These businesses are predominately in retail and hospitality sectors, making up £458m (or 80%) of the total rent that tenants claim to owe.

Table 3. Amount owed by business description

| Business description of tenants (based on SIC code) | Amount owed (£) |

|---|---|

| Public houses and bars | £127,272,161 |

| Licensed restaurants | £74,417,356 |

| Retail sale of clothing in specialised stores | £70,521,408 |

| Hotels and similar accommodation | £38,837,000 |

| Fitness facilities | £38,693,689 |

| Other retail sale of new goods in specialised stores (not commercial art galleries and opticians) | £30,000,000 |

| Retail sale of footwear in specialised stores | £26,500,000 |

| Retail sale of books in specialised stores | £20,700,000 |

| Gambling and betting activities | £17,500,000 |

| Retail sale of cosmetic and toilet articles in specialised stores | £13,500,000 |

Outcomes of negotiations

The majority of tenants (52.9%) believed that between 0-20% of landlords were engaging in the spirit of the code of practice. On average, landlords stated that 56.5% of tenants were engaging in the spirit of the code of practice. It is also worth noting that, on average, the ‘Other’ respondents felt that only 46.5% of landlords were engaging, whereas as few as 41.5% of tenants were.

The most common outcomes of negotiations were the same for both landlords and tenants. These outcomes were agreement of longer duration to pay arrears (experienced by 39.2% of tenants and 61.7% of landlords), agreement to write-off of an agreed amount of rent arrears (experienced by 33.3% of tenants and 54.1% of landlords) and reduced rent for a proportion of the remainder of the lease (experienced by 18% of tenants and 44.4% of landlords).

A significant group of tenants stated that they had also commonly experienced landlords refusing to negotiate. Alternatively, a subgroup of landlords suggested they had pursued what was commonly referred to as ‘Asset management deals’ – this is where some form of rent forgiveness (reduced, deferred or waived) was agreed in return for something beneficial to the landlords (e.g. removal of break clause or extension of lease).

Many landlords stated that they were negotiating in order to share the burden of the pandemic. Another group of landlords stated they wanted to assist tenants with cashflow problems, whilst a small number of landlords suggested that the outcomes of negotiation were better than nothing.

For tenants, the most common duration to repay arrears agreed was within 12 months, experienced by 22.5% of tenants. The next most common was within 6 months, experienced by 16% of tenants. For landlords, the most common duration to repay arrears agreed was within 12 months, experienced by 41.4% of landlords. The next most common was within 24 months, experienced by 20.3% of landlords.

More tenants (54.9%) had not been able to agree any concessions than those that had been able to (42.2%). The predominant reason for this was the willingness of landlords to negotiate. The most common percentage of concessions agreed was 0-19%, experienced by 19.6% of tenants. According to landlords, the most common percentage of concession granted was also the 0-19% bracket, granted by 22.6% of landlords.

The most common type of concession granted by landlords was longer duration to pay off arrears, granted by a large majority of landlords (73.7%). Reduced rent and writing of an agreed amount of debt were also common concessions, both granted by a slight majority of landlords (both 55.6%). A small subgroup of landlords also referred to granting rent deferrals, as well as several landlords agreeing turnover based leases with tenants.

The sectors given the most concessions were as follows: Retail, Hospitality and leisure granted by 71.4%, 66.2% and 45.9% of landlords respectively.

Many (46.7%) tenants said they will not be able to repay rent arrears. A significant number (27.8%) stated they were unsure if they would be able to, whilst a smaller group stated they would be able to (22.2%). The most common timeframe for tenants to repay arrears was more than 24 months, expected by 19.9% of tenants. The most common reasons for not being able to repay rent arrears was a lack of income and that the built-up debt was too great. A small group of tenants stated their ability would depend on the recovery from the pandemic.

There was no clear consensus on whether landlords expected their tenants to be able to repay rent arrears. The largest group of landlords (39.8%) did not expect to be able, whilst a similar number (33.1%) did expect them to repay all arrears. A smaller but significant group of landlords were unsure (23.3%). The main reasons for landlords not expecting repayment were the tenants’ ability to refuse to pay and simply a lack of income. There was no clear consensus on when tenants would be able to repay arrears, but the most common expectation was within 12 months, predicted by 18.8% of landlords.

It was commonly expressed by all parties that the current code allows both tenants and landlords to avoid negotiating if they want and hence negotiations are often dependent on the willingness of individuals.

2.2 Current moratorium and code of practice

There was no clear consensus on whether the current moratorium encourages negotiations. The predominant opinion, expressed by 39.2% of respondents, was that it does not. 50% of these were tenants, whilst 37.7% were landlords. The predominant opinion expressed by many respondents was that the voluntary nature of the current measures makes them easily ignorable which limits their effectiveness. Another significant group of respondents (26.2%) suggested it does encourage negotiations. 66.9% of these were tenants, whilst only 19.5% were landlords.

There was no clear consensus on whether the current moratorium provides sufficient time for negotiations. 35% of respondents suggested it does and 35.3% suggested it does not. The vast majority of those suggesting that it does not provide sufficient time were tenants (84.4%). Conversely, the majority of those suggesting it was sufficient time were landlords (50.6%) – this equates to 67.7% of all landlords.

The predominant opinion expressed by respondents was that time is not the issue. It was often suggested that the length of time was not the factor enabling/inhibiting negotiations, and that negotiations were more dependent on the willingness of individuals. Some respondents suggested that too much time had been given and an extension would be detrimental, whilst another group suggested an extension was needed to further assess the COVID-19 situation.

Many respondents (45.7%) suggested that the current moratorium had had no impact on employment. A significant proportion of these were tenants (48.7%) and slightly fewer were landlords (38.8%). It is worth noting that this equates to a 67.7% of all landlords. A significant group (32.7%) stated it had reduced their employment. The vast majority of these were tenants (78.9%). The predominant reason for this was it resulting in a reduced income, with a limited subgroup suggesting it had resulted in a lack of certainty.

The majority of respondents stated that the current measures provide ability to pay other creditors in order to enable trade (51.2%). The majority of these were tenants, only a limited group were landlords. There was no clear consensus on why this enabled trade, but some respondents suggested that they found it easier to negotiate with other creditors/service providers than landlords/tenants.

The majority (61%) of respondents either disagreed or strongly disagreed that the current code of practice is effective. A large majority of these were tenants (68.8%). Only 20.9% were landlords, but this does equate to 48.9% of all landlords. The predominant opinion expressed to explain this was that the voluntary nature of the current code of practice means that it is easily ignored and therefore limits its effectiveness. A subgroup stated that the code was unnecessary and suggested how it was just delaying the inevitable.

A limited subgroup suggested they either agreed or strongly agreed (10.4%), split evenly between tenants and landlords. Several respondents suggested that the code had helped to encourage negotiations.

The key change wanted by many respondents was the code to be made legally enforceable, in order to make it effective. Another group suggested that landlords and tenants should have to provide proof of their situations in negotiations (e.g. consider pre-Covid trade, ensure that those who can pay do pay, ensure a % of grants given to tenants is passed on to landlords).

3. Options

This section refers to the questions relating to the discussion of options going forward. There are 6 options discussed each with their own subsection. For each option the proportion of those in favour, a breakdown of key expected outcomes and a breakdown of the expected impacts on business will be provided, as well as more specific questions for individual options. The section ends with a brief discussion of alternative options as suggested by respondents.

3.1 Option 1 – allowing the current tenant protection measures to expire

The majority of respondents (57.3%) were against letting measures expire, whilst a significant group (33.7%) were in favour of letting measures expire. The vast majority (89.7%) of those against letting measures expire were tenants. This equates to 85.3% of all tenants. On the other hand, the majority of those in favour (69.6%) were landlords. This equates to 89.5% of all landlords.

The predominant reason given as to why respondents were against letting measures expire was simply that expiration would harm business. Another significant group of respondents suggested that it was too soon in terms of the recovery from the pandemic and therefore they wouldn’t be in a position to pay back arrears. A smaller but still significant group of respondents stated their preference for option 1 was dependent on the post-expiration plan.

The most commonly expected outcome of option 1 was rent arrears to be demanded in full, expected by the majority of respondents (60.6%). This option had the largest numbers of respondents expecting rent arrears being demanded in full, tenant eviction procedures, Closure of premises redundancies and insolvencies compared to all other options.

Many tenants stated that they believed this option would give all the power to landlords. Another significant group of tenants stated that it was too soon to lift measures, as they needed more time for income to pick up before they start paying rent. A small group of landlords, who were in favour of letting measures expire, emphasised their desire to help tenants as they would not want vacant properties.

Three-quarters of respondents stated landlord/tenant discussion as what has informed their opinion. The next most common source of information was word of mouth.

The majority (53.7%) of respondents stated that this option would either reduce or cease trade. The vast majority of these were tenants (88.3%). The majority of landlords stated that it would enable trade (54.1%).

The majority (51.4%) of respondents to this question stated that this option would either reduce or cease employment. The vast majority of these were tenants (89.3%). The predominant reason expressed for this was the expiring of measures harming the respondent’s business or forcing its closure. This was followed by a significant group (27%) who thought it would have no impact on employment. A small subgroup, mainly made up of landlords, thought this option would increase employment. The reason for this was the increased income from the payment of rent arrears.

When asked specifically how many jobs would be gained or lost, the totals were as follows: 525 jobs gained, 5,359 jobs lost (Net –4,834). Please note that 1,800 job losses were forecast by one respondent for the first 5 options. The same respondent then forecast 2,500 job gains for option 6.

Over half of (55.9%) of respondents felt this option would decrease their ability to invest in the future. The vast majority of these (88.4%) were tenants. The predominant reason for the decreased ability to invest was the option resulting in a lack of income to invest with. Similarly, over half of respondents (51.2%) said this option would decrease their ability to contribute to government priorities.

3.2 Option 2 – allow the moratorium on commercial lease forfeiture to lapse but retain the insolvency measures and restrictions on the use of CRAR

The majority (61.81%) of respondents were not in favour of this option. 60% of these respondents were tenants whereas only 28.6% were landlords. This equates to the majority of both tenants (62.1%) and landlords (67.7%) being against this option.

A significant group of tenants were against this option as they felt it would give landlords an unfair amount of power. An alternative group, mostly tenants, also suggested it would harm their business. Several respondents felt that this option would just delay the inevitable, rather than actually create change.

A small group of respondents (18.9%) were in favour of this option. These respondents were split fairly evenly between landlords and tenants. A limited subgroup suggested that this would encourage landlords to engage, and others felt it would provide tenants some protection.

The most commonly expected outcome of this option was rent arrears to be demanded in full (49.8%). Other commonly expected outcomes included tenant eviction procedures and closure of premises. The predominant reason provided for these expected outcomes was the option still enabling the refusal to negotiate.

The majority of respondents (62.2%) felt that this option would either reduce or cease trade. A large majority of these were tenants (74.7%). The main reasons being business closures and reduced income if businesses were to survive. However, a limited subgroup did feel that option would lead to the resolution of conflict and in turn enable trade.

The majority of those (55.1%) who responded to this question suggested this option would result in reduced employment or completely cease employment. Alternatively, a significant group of respondents felt that this option would have no impact on employment.

When asked specifically how many jobs would be gained or lost, the totals were as follows: 88 jobs gained, 7,208 jobs lost (Net –7,120).

Many respondents felt that this option would decrease their ability to invest in the future. A large majority of these were tenants (74.5%). The reasons for this included a lack of income, decreased certainty and having to focus on paying off debts before investing. Small groups felt that it would have increase their ability or no impact. Many respondents also felt this option would decrease their ability to contribute to government priorities, with very few suggesting it would increase their ability.

3.3 Option 3 – targeting existing measures to businesses based on the impact that Covid restrictions have had on their businesses

The majority of respondents felt that both capacity or trading restrictions (63.4%) and full closure (60.8%) should be considered. Many also suggested that any restrictions that resulted in a loss of business should be considered.

A significant group of respondents suggested that the response should be targeted by sector, region or size of business. An alternative group of respondents suggested that tenants should be made to prove the impact of the pandemic on their business (e.g. consideration of pre-Covid trade, ensure that those who can pay do pay, ensure a % of grants given to tenants is passed on to landlords etc.).

The majority (61.2%) of respondents did not think that 6 months was the right amount of time to lift the targeted measures. 72.8% of tenants felt that it was not the right time, whilst only 41.4% of landlords felt that it was not. Roughly a quarter of respondents did think it was the right time.

When asked why, 63% of individuals that responded suggested more time was needed. Almost all (92.5%) of these were tenants. The predominant reason for this was needing more time to recover (financially) from the impacts of the pandemic. Another group of respondents suggest that the impacts of Covid remain and will continue to remain on business (e.g. footfall down, unable to operate at full capacity). Another small group of respondents made specific reference to seasonal trade and their busy period not being included in the 6-month window.

Only 15% suggested less time would be more beneficial. A large majority of these (77.5%) were landlords. The main reason given for wanting less time was that the restrictions are no longer helping or are damaging for business. An alternative subgroup suggested there has been enough time for agreements to be reached.

The most commonly expected outcomes were negotiation on rent arrears amount owed and negotiation on rent arrears duration to pay (both 42.1%). The next most common expected outcome was rent arrears demanded in full. The predominant reason for these expected outcomes is that it would encourage / force outcomes. However, another group suggested that their counterparts would take advantage of this option (the majority of these were tenants).

Almost half (48.2%) of those responded suggested this option would either reduce or cease trade, whilst roughly a quarter of respondents suggested it would enable trade.

Many respondents believed that this option would reduce employment or cease it completely. Over three-quarters (76.5%) of these were tenants. The predominant reason for this was the option harming business or forcing closure. The next most commonly expected outcome was no impact on employment. A small group of respondents suggesting it would increase employment as it would increase confidence and certainty.

When asked specifically how many jobs would be gained or lost, the totals were as follows: 1,714 jobs gained, 6,194 jobs lost (Net –4,480).

Roughly half of those who responded suggested this option would reduce their ability to decrease their ability to invest. The predominant reason for this was due to a lack of income, while another smaller group of respondents suggested it was due to decreased certainty and therefore incentive to invest. A similar number suggested it would reduce their ability to contribute to government priorities.

3.4 Option 4 – encourage increased formal mediation between landlords and tenants

Marginally more (43.1%) respondents were against this option than for it (40.2%). Out of those not in favour, 47% were tenants and 39% were landlords. It is worth noting that this equates to the majority of landlords (64.7%).

A large group of respondents suggested that mediation would not lead to any more negotiations, whilst another suggested that it was not a strong enough measure and needed legal backing. Another subgroup was against it because it would be a costly and/or complicated process.

Out of those in favour, 74.5% were tenants and only 14.7% were landlords. This equates to 49.7% of all tenants. There was no clear consensus as to why people were in favour of this option. A small group suggested it would be an effective way to encourage negotiations, whilst another said the involvement of a third party would make the process clear and/or fair.

Many respondents (35.8%) stated that mediation is sometimes effective, and another large group (29.33%) stated it is not effective. The predominant reason suggested for why mediation is only sometimes effective is that it is dependent on the specific mediator as well as the willingness of both parties. Another group suggested it was not strong enough as a measure and needs legal backing to ensure its effectiveness.

A small group suggested that mediation can be effective or very effective. A large majority of these (78.6%) were tenants.

Only a small group (17.3%) claimed to have used mediation in the past. Out of those who answered, 35% of individuals felt that mediation had been successful whereas 65% of individuals felt that mediation had not been successful. The predominant reason it was not successful was that the voluntary nature of it means that individuals were still able to refuse negotiation.

The majority of respondents (66.3%) claimed to have not used mediation in the past. The predominant reason for why individuals did not consider mediation was they did not feel it would resolve the issue. Other reasons included the belief that not all parties would agree and cost.

The most common expected outcomes were negotiation on rent arrears amount owed (43.3%), negotiation on rent arrears duration to pay (40.8%) and rent arrears demanded in full (30.3%). There was no clear consensus on why these would be the outcomes. There was a strong opinion expressed that this option would not materially change very much and therefore would not lead to many further negotiations.

A significant proportion of those who responded (46.2%) suggested that this option would reduce or cease trade. The majority of these were tenants (69%). The predominant reasons suggested for this was the ineffectiveness of mediation resulting in little material change.

A significant proportion of those who responded (47.5%) suggested that this option would have no impact on employment. Another group (42.2%) suggested it would reduce or cease employment. A small group (21.2%) suggested it would increase employment.

When asked specifically how many jobs would be gained or lost, the totals were as follows: 76 jobs gained, 7,358 jobs lost (Net –7,282). Please note 1,800 job losses were forecast by one respondent.

The majority (54%) of those who answered suggested that this option would decrease their ability to invest in the future. There was no clear consensus as to why this would enable or inhibit future investment. Many of those who answered (48.4%) felt as though this option would decrease their ability to contribute to government priorities. The main reasons for this include a lack of income to contribute with, as well as mediation being costly and/or time consuming.

3.5 Option 5 – non-binding arbitration

The majority (51.2%) of respondents were not in support of non-binding adjudication. The predominant opinion expressed by respondents not in favour of this option was that it needs to be binding in order to ensure its effectiveness. Alterative groups felt that that this option was unnecessary and that it would be costly and/or timely. Roughly a quarter of respondents (25.2%) were favour of non-binding adjudication. A large majority of these were tenants (80.5%).

The most common expected outcomes of non-binding adjudication were negotiation on rent arrears amount owed (39.8%), negotiation on rent arrears duration to pay and rent arrears demanded in full. The reasons for these expected outcomes were split between those believing that having an adjudicator would encourage negotiations further, and those suggesting the option would be ineffective if it is not binding.

The most commonly suggested remedies of non-binding adjudications were give additional time to pay arrears (51.6%) and waive a proportion of rent arrears (51.4%). There was no clear consensus as to why these were the most popular remedies. There was a group of respondents, mostly tenants, who suggested that adjudicators need the most remedies available to maximise flexibility and find effective solutions.

A significant proportion of those who responded (40.4%) suggested that this option would enable trade. The vast majority of these were tenants (87.2%). The predominant reasons suggested for this was the increase in income and the resolution of the conflict. Another significant group suggested this would reduce or completely cease trade (38.9% of those who responded). The predominant reasons suggested for this was reduced income and the ineffectiveness of the option as it is non-binding.

A significant proportion of those who responded (47.6%) suggested that this option would have no impact on employment. Another group (31.3%) suggested it would reduce or cease employment. The predominant reason for this was a lack of income, whilst another group suggested the option would harm the respondent’s business or force its closure. A small group (21.2%) suggested it would increase employment. Almost all (93.8%) were tenants. The main reason for this was the option resolving the ongoing conflict which would lead to increased confidence and certainty.

When asked specifically how many jobs would be gained or lost, the totals were as follows: 526 jobs gained, 5,158 jobs lost (Net –4,632).

A significant group of respondents felt that this would decrease their ability to invest in the future. A smaller group felt that it would increase their ability. The vast majority of these were tenants. The main reasons for this were increased certainty providing an incentive to invest and increased income providing the ability to invest. Many respondents also suggested this would reduce their ability to contribute to government priorities. The reasons for this included a lack of income, having to focus on repaying debts and increased uncertainty.

3.6 Option 6 – binding arbitration

49.2% of respondents were in favour of binding adjudication, whilst only 27.36% were actively against it. The vast majority of those in favour were tenants (81.2%). This equates to 66.3% of all tenants. The predominant reason for supporting binding adjudication was simply because it forces negotiations. Other key reasons for those in favour were the belief that it would help stop the abuse of power in negotiations as well as the framework provided by binding adjudication bringing clarity.

The majority (63.3%) of those against were landlords. This equates to 66.2% of all landlords. The predominant reason respondents were against binding adjudication was the belief it would be costly, time consuming and/or management intensive. Also, a small group of respondents suggested it would undermine existing legislation. The most common expected outcomes were negotiation on the amount of rent arrears owed (56.1%) and negotiation on duration of time to pay rent arrears (52%). These outcomes were expected to be produced by this option more commonly than any other.

Additionally, this option had the least expected insolvencies. The predominant reason for these expected outcomes was expressed by a significant group of tenants who stated that it should stop their counterparts in negotiations abusing their power, resulting in fair negotiations.

The predominant view expressed by those in favour was that adjudicators should have the most possible options available to them as this would ensure flexibility and in turn a fairer result. As a result, there was significant support for all remedies offered. In particular, the majority of respondents were in support of ‘Give additional time to pay arrears’ (55.3%) and ‘Waive a proportion of rent arrears’ (54.9%).

The majority (63.3%) of those who responded stated that binding adjudication would enable trade. The vast majority of these were tenants (87.1%). The predominant reason for this was because the option would build certainty and bring confidence. An alternative reason given was that it would help resolve the conflict and in turn help to re-establish cashflow. A small but significant group of respondents (20.4%) stated that binding adjudication would reduce or cease trade. The majority of these were landlords. 106 (or 67.5%) fewer insolvencies were expected if option 6 was implemented compared to option 1.

The predominant opinion (43.7% of respondents who answered) was that this option would have no impact on employment. This was closely followed by a group (41.8%) who thought it would increase employment, over 90% whom were tenants. The main reason given for this was the option facilitating business recovery, whilst others suggested it was due to a re-established income stream. Another significant group suggested it was due to the increased confidence and certainty that the option brings. A small group of respondents (14.5%) felt that it would reduce or cease employment, all of whom were landlords.

This option had the largest number of individual respondents predicting that it would enable employment. When asked specifically how many jobs would be created or lost, the totals were as follows: 4,967 jobs gained, 87 jobs lost (Net +4,880). Please note that 2,500 jobs created were forecasted by one respondent.

Many respondents felt this option would increase their ability to invest in the future. The vast majority of these (89.1%) were tenants. The predominant reason for increased ability to invest was the option increasing certainty and providing an incentive to invest. Another key reason was that the option provided an increase income and therefore the ability to invest further. Many respondents also suggested it would increase their ability to contribute to government priorities, the vast majority of whom were tenants (89.6%).

3.7 Other options

There was no clear consensus to the other options that should be considered. The main opinion expressed in the responses was a desire for the government to force negotiations, and therefore it was requested that the government bring in some legislation that forces negotiations. Another significant group of respondents requested a change to a turnover based lease model (often referred to the Australian model). Another smaller group of respondents requested the use of sector specific measures.

4. Ranking of preferred options

The following section refers to questions in the survey where respondents were asked to rank the options in order of their preference. Analysis into what types of respondents had preference for different options has been provided.

4.1 Most preferred and least preferred options

Respondents were asked to rank the six options in order of preference. The most preferred option for 79% of landlords is Option 1 (i.e. allow the measures to expire on 30 June 2021). Option 6 (Binding non-judicial adjudication between landlords and tenants) is the most preferred by tenants (57%). First preferences across all options are summarised in Figure 5.

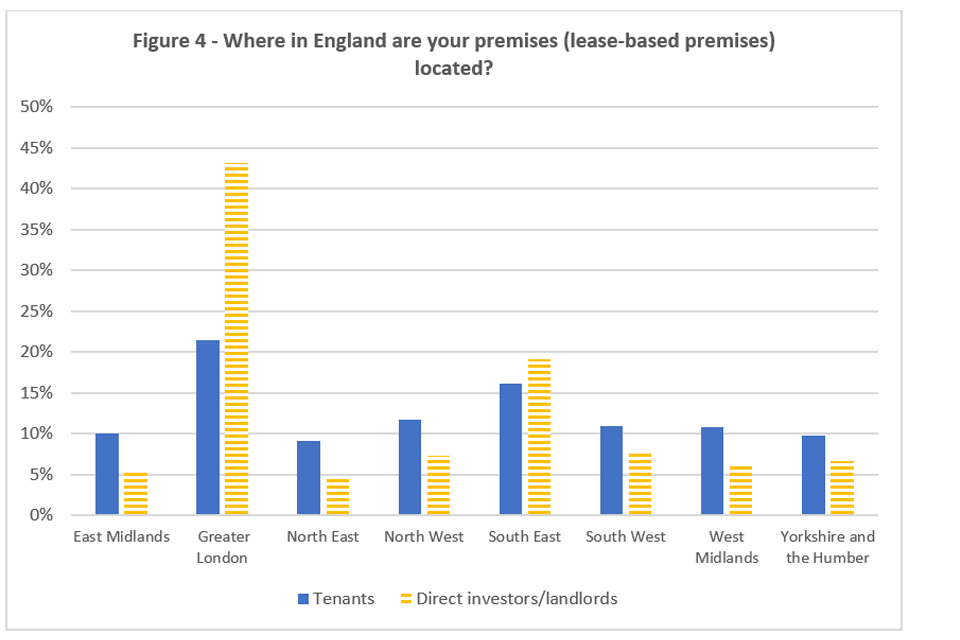

As shown in Figure 6, Option 6 is least preferred by landlords. Some 49% respondents in this group ranked this option as the sixth preferred. While Option 1 is the least preferred Option by 89% of tenants.

Given the relatively low number of landlord respondents (133) compared to tenants (301), further analysis based on landlords’ second preferences and business sizes is shown in the following section.

4.2 Further analysis of landlord preferences

There was some disparity between SME landlords and large landlords based on first and second preferences.

It is important to note that only a very small proportion of landlords are large organisations (16 respondents) – with only 14 of these providing a ranking of preferred options, which limits the conclusions that can be drawn from the analysis below.

First preferences

While most landlords have stated Option 1 as their first preference, a smaller proportion of large landlords are in favour of this option compared to landlords that are SMEs. Option 3 and Option 2 were more popular options for large landlords compared to SMEs. This is shown in Figure 7.

Second preferences

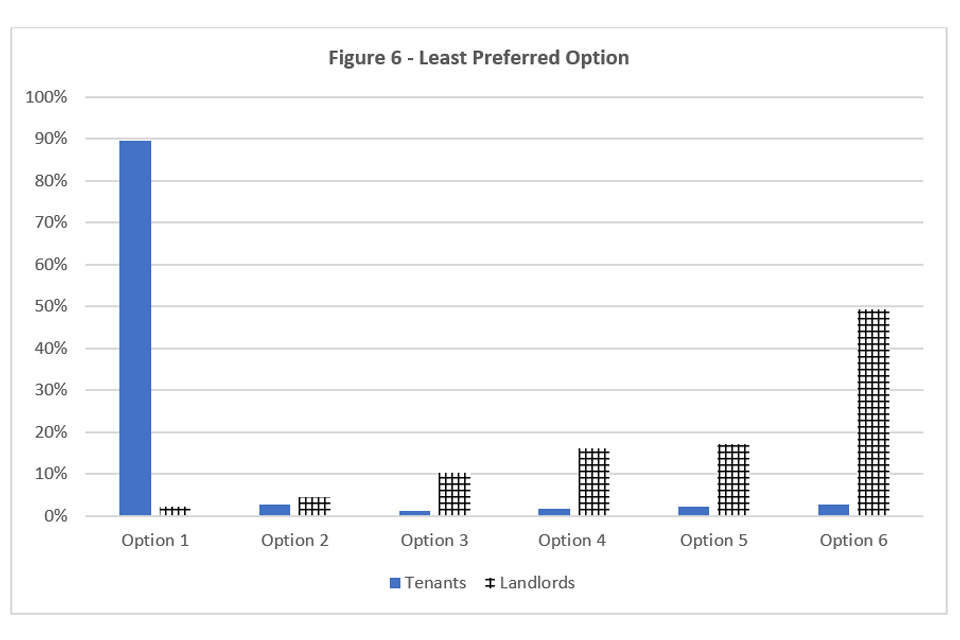

In terms of second preferences, Figure 8 shows that Option 2 is the second most preferred option for 42% of SME landlords compared to 31% of large landlords.

Large landlords have stated Options 2 and 3 as their second preference in equal proportions (31%). While Option 6 is popular with a relatively higher proportion of large landlords compared to SMEs.

Option 4 has the biggest disparity between SMEs and large landlords in terms of second preference. None of the large landlords stated this option as their second preference compared to 18% of SMEs.