Government response: mandatory reporting of child sexual abuse consultation (accessible)

Updated 9 May 2024

Introduction and contact details

This document is the post-consultation report for the consultation paper ‘Mandatory Reporting of Child Sexual Abuse’.

It will cover:

- the background to the consultation

- a summary of the consultation responses

- a detailed response to the specific questions raised in the consultation

- the next steps following this consultation.

Further copies of this report and the consultation paper can be obtained by contacting the Tackling Child Sexual Abuse Unit at the address below:

Tackling Child Sexual Abuse Unit

Home Office

2 Marsham Street

London SW1P 4DF

Email: mr_csa@homeoffice.gov.uk

This report is also available at: Child sexual abuse: mandatory reporting - GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

Alternative format versions of this publication can be requested from mr_csa@homeoffice.gov.uk

Complaints or comments

If you have any complaints or comments about the consultation process, you should contact the Home Office at the above address.

Background

The consultation paper ‘Mandatory Reporting of Child Sexual Abuse’ was published on 02 November 2023. The consultation invited comments on the Government’s proposed model for a new mandatory reporting duty, particularly:

- who the duty should apply to

- how reporters could be protected

- any exceptions which should apply

- the nature of sanctions which should apply to non-compliance with the duty.

The consultation period closed on 30 November 2023 and this report summarises the responses, including how they have influenced the final shape of the mandatory reporting duty.

The consultation was preceded and informed by a call for evidence exercise which took place between May – August 2023. Further detail on responses to the call for evidence questions which informed this consultation can be found at Annex A.

The Impact Assessment which accompanied the consultation is being updated to take account of evidence provided by stakeholders. A final version will be published as part of the Impact Assessment for the Criminal Justice Bill when the Bill receives Royal Assent.

Summary of responses

Overview

A total of 350 responses to the consultation paper were received. Of these, 321 completed the online questionnaire provided, and 29 submitted views to the dedicated consultation mailbox.

In addition to responses to the specific questions, the consultation attracted general reflections on the topic of mandatory reporting and the crime of child sexual abuse more widely.

A noticeable theme of the wider commentary was the suggestion that Government should delay introduction of the duty to allow additional time to build up preparedness.

The consultation document itself set out the Government’s willingness to provide an appropriate period to work on implementation preparedness with all impacted sectors. However, we must reiterate that any delay to accommodate specific practical challenges must be kept to a minimum.

We also acknowledge the view expressed by some stakeholders that the duty must be delivered as part of the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse’s (‘the Inquiry’) holistic package of recommendations, of which mandatory reporting was one. On 10 January, the Home Secretary issued a detailed written statement on the Government’s progress in implementing the recommendations to date.

Some respondents called for the Government to go further than its outline proposals in respect of the duty. Others expressed the view that bringing forward a duty on individuals and not organisations or institutions represents a missed opportunity.

The Inquiry did not recommend an organisational duty, and consultation responses did not set out a clear evidence base for adopting one. We believe criminalising obstruction of the individual-level duty will realise the policy intent of discouraging and punishing ‘cover-ups’ of child sexual abuse, with appropriate accountability on those responsible regardless of their position in a corporate hierarchy. We will consider the potential value which organisational reporting could add as we implement and evaluate the impact of this duty.

There were often differences in perspective between respondents who identified themselves as speaking for children and those who represented victims and survivors of childhood abuse, which we have tried to navigate sensibly and with respect.

Themes

Overall, the response to the consultation on mandatory reporting of child sexual abuse fell into the following themes:

- Impact on children and young people

- Preparing for the duty

- Wider impacts

- Alignment with other reforms and strategy

Impact on children and young people

Some respondents raised the potential impact of a mandatory reporting duty on the provision of safe spaces for children to discuss their concerns, and any disengagement from vital safeguarding services as an unintended result. This was particularly raised when discussing confidential advice helplines and web services. Health stakeholders emphasised the need to ensure that the duty does not inhibit or delay young people from accessing healthcare services including sexual and reproductive healthcare.

We acknowledge the need to allow for exceptional cases to avoid harmful unintended consequences. The duty to report will accommodate situations where there is a strong justification on the grounds of child safeguarding or where loss of confidentiality would fatally undermine service provision – for example, a reporter will be able to delay making a report for a reasonable period where this is in the child’s best interests.

Consultation respondents also questioned the potential interaction of the mandatory reporting duty with ongoing policy measures to better understand and address harmful sexual behaviour (HSB) in young people. Some respondents set out their concerns around the impact a criminal response may have on a child who discloses the ‘perpetration’ of harmful sexual behaviour; noting that many young people in this situation will be victims of sexual abuse or other forms of harms themselves.

We will limit the definition of such disclosures to those which are made by individuals over eighteen years of age, whilst making clear in guidance that such circumstances should still receive a robust safeguarding response from reporters. As with all aspects of the duty, this will not replace or supersede reports being made in line with existing reporting processes or professional guidance.

We also received concerns that limiting the duty to direct disclosures may be disadvantageous to babies, children and young people who are non-verbal or experiencing language barriers.

We will ensure the definition of a ‘disclosure’ under the duty may be made in any form, reflecting the potential for a range of communication methods available to children and young people. This may include non-verbal forms of communication.

Several respondents raised wider equalities impacts in respect of the new duty, including communicating its meaning and consequences to children, especially those with special educational needs and disabilities (SEND); and issues around the ‘adultification’ of ethnic minority children when reporters are asked to make judgements as to the nature of consensual relationships between teenagers.

We are committed to ensuring that this duty affords all children equal protection, and will ensure this is the case as we prepare for implementation. We will include specific reference to equalities impacts when carrying out our commitment to evaluate the duty at an appropriate point.

Preparing for the duty

A consistent theme among consultation responses was the need for reporters to receive adequate training and guidance. When discussing how the Government can best ensure reporters are protected in carrying out their duty, some respondents reflected that effective training can be a pre-emptive form of protection.

We received challenge to the published consultation Impact Assessment, which set out the Government’s position that a minimal amount of familiarisation would be needed given existing statutory responsibilities and guidance on reporting suspected harm to children. We are currently updating our assessment to reflect the feedback received.

Some respondents expressed the view that communicating the importance and requirements of the new duty effectively will be a key task for central government. This will include ensuring that the professionals responsible for delivery understand the duty and its relationship to existing reporting requirements and professional practice; but also that children, young people and their families are clear on how it affects their rights when accessing services and seeking support.

The Government will set out clear guidance (statutory or non-statutory) on the operation of the duty. We will work with regulators and professional standards-setting bodies to ensure the new duty is clearly communicated ahead of implementation. The suggestion to include the implications of the duty for relationships, health and sex education (RHSE) curriculum requirements will be a question for the Department for Education to consider.

However, accommodating familiarisation with the duty within recruitment, induction and working practices will be a key task for all individuals and organisations affected by the duty. Impacted sectors will consider any training and materials needed to support the workforce in delivering the duty and improving their response to child sexual abuse. The introduction of the duty should be seen as an important moment for the ‘national conversation’ on child sexual abuse envisaged by the Inquiry, and an important step leading to improvements across society in how this harm is identified and addressed.

Wider impacts

Recruitment and retention in impacted reporting roles were brought up by a significant number of respondents. Many felt the imposition of a new reporting duty with significant personal penalties could dissuade members of the public from roles involving children and young people.

Some groups felt that in introducing a duty to report child sexual abuse, the Government may create a ‘hierarchy of abuse’ in England, with physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect in danger of being perceived as less important and receiving a less robust response from safeguarding professionals and organisations as an unintended consequence.

Many respondents called for the draft Impact Assessment to include the cost of supporting the ‘additional’ victims identified by reporting under the duty, with the limited capacity of specialist therapeutic support services a particular concern. Others were concerned about the potential impact on the criminal justice system, including the capacity of the courts and prison estate; and the consequent delays which victims may face in securing justice.

We acknowledge the importance of those points. The Government is taking forward separate action in these areas (recommendation 16 of the Independent Inquiry and ‘Stable Homes, Built on Love’). We believe that recruitment and retention issues can be appropriately managed through responsible messaging from workforce leads and commissioning bodies, particularly within sectors already subject to stringent child protection and safeguarding duties. An accurate and robust assessment of need provided by improved reporting is needed to ensure appropriate support services are commissioned.

While the hierarchy of abuse has been a longstanding consideration in adopting harm-specific measures, there is strong evidence (including from the Inquiry) that child sexual abuse is chronically underreported, and therefore requires exceptional measures.

Alignment with other reforms and strategy

Many respondents made the point that mandatory reporting is not a panacea to the issue of protecting children from child sexual abuse. Others set out their view that the duty must sit within an integrated cross-Government strategy to prevent harm, deal effectively with perpetrators, and support victims and survivors.

The success of a mandatory reporting duty was generally considered to be contingent on the effective delivery of all recommendations in the Inquiry’s final report and the Independent Review of the Disclosure and Barring Service. Stakeholders have also called for a clear articulation of how the mandatory reporting duty relates to the Government’s Violence Against Women and Girls (VAWG) Strategy, children’s workforce development plans, and ongoing multi-agency safeguarding reforms.

The Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse recommended that the UK Government and Welsh Government introduce mandatory reporting regimes for this form of abuse. However, in April 2023 the Welsh Government confirmed that it would not be seeking to legislate in this area. As the duty discussed in this report will apply in England only, some respondents to the consultation took the opportunity to register their interest in understanding how it would interact with reporting and safeguarding regimes in the UK’s devolved administrations.

We will address all of these issues as we prepare for implementation of the duty ahead of commencement.

Responses to specific questions

Methodology

It is important to note when interpreting the findings that:

The analysis presented in this report is qualitative and therefore subjective. While we are confident that others would extract similar insights, some may have different views.

- Where a chart has been provided for illustrative purposes, the underlying data is drawn from Smart Survey responses only.

- Respondents were able to skip questions they did not wish to answer. This means not all respondents provided a response to each question.

The data collected through the consultation questions was generally provided though open, free-text entries, which therefore required qualitative analysis. To enable thematic analysis, questions were divided into separate frameworks, and a coding frame (list of identified themes or topics) developed for each. Responses were then coded to this framework to extract insights, with quality assurance provided to mitigate against subjectivity.

Themes were created both inductively (i.e. developing a theme by looking at the data) and deductively (i.e. developing a theme based on topic knowledge), and edited iteratively, to ensure they remained appropriate. Analysis was developed using both Smart Survey tools and Microsoft Excel.

Common responses to open, qualitative consultation questions have been grouped in accordance with our coding framework and are presented below each question, ordered from most to least common suggestions. In view of the subjectivity involved in coding responses, exact figures have not been presented.

Consultation Questions

Q: In addition to the definition of ‘regulated activity in relation to children’ provided by the Inquiry, the government is proposing to set out a list of specific roles which should be subject to the mandatory reporting duty. Which roles do you consider to be essential to this list?

- education staff and volunteers

- any position working with children

- NHS/medical staff and volunteers

- social workers

- police officers

- youth organisations staff and volunteers

- leaders and volunteers within religious/faith organisations

- sports and physical activity staff and volunteers

- nursery/early years staff and volunteers

- childcare roles

- counselling and psychotherapy roles

- all adult members of the public

- arts and leisure instructors and supervisors

- staff working with children in the entertainment industry or child-centred businesses

- youth justice agencies

- transportation workers

- specialist support services staff and volunteers

- employers of under-18s

- regulators and inspectorates

- Other: including fire officers, hotel workers, courts staff, supermarkets, shops, restaurants, care homes/residential homes, civil servants, librarians, sexual offence examiners, forensic clinicians, housing officers, sports club committee members, elected officials (e.g. Members of Parliament, councillors), respite care settings, military personnel overseeing cadet forces, transport services including taxis and coaches commissioned by the providers of regulated activities, night-time economy workers, paramedics, physiotherapists, and radiographers.

Commentary

We are confident that many of the roles proposed in response to this question will already be covered by the Inquiry’s definition of ‘regulated activity in relation to children’. We will provide for a regulation-making power in legislation to ensure any identified gaps can be filled, as well as to future-proof the mandatory reporting duty against the emergence of new functions or settings which it may be appropriate to consider.

Several respondents were concerned that defining specific roles could lead to unintentional loopholes in the duty; for example an organisation amending an individual’s job title while leaving their role’s essential functions unchanged in order to avoid liability. We will consider setting out a clear list of activities or functions in relation to children rather than roles. The work to develop this list will be aligned with the Government’s implementation of the Independent Review of the Disclosure and Barring Regime recommendations.

We have reflected on strong feedback that certain advice helplines, for which the assurance of confidentiality is an essential element of service provision, are not rendered inoperable by the implementation of the duty. We are considering available mechanisms to mitigate the impact of the duty in those exceptional cases where loss of confidentiality would fatally undermine the provision of safeguarding services.

Some respondents raised the importance of ensuring that introducing a duty on specific roles does not undermine longstanding messaging from Government that safeguarding children is everyone’s responsibility. We are mindful of the importance of communication in preparing for implementation and will take this feedback into account when developing messaging to contextualise the new duty.

Q: What would be the most appropriate way to ensure reporters are protected from personal detriment when making a report under the duty in good faith; or raising that a report as required under the duty has not been made?

- Anonymous reporting or confidentiality

- Protections modelled on existing whistleblowing laws

- Reporting culture written into organisational policies, procedures, codes of conduct

- Provision of roles servicing protection, confidentiality and support to reporters

- Centralised whistleblowing helpline or online portal for reports

- Immunity from civil action relating to a report

- Guidance to police/local authority on how investigations should treat reporters

- Other: including ‘without prejudice clauses’; disclaimer statements; clear procedures and guidance/definitions; greater levels of training and support; use of the NSPCC helpline; guidance setting out what will happen with a report once made; clarity that mandatory reports don’t breach confidentiality requirements; regulators auditing reporting culture; reporting should always be to an external organisation; create an offence of causing or threatening to cause detriment to a reporter.

Commentary

Those that expressed a view very commonly set out their preference for anonymous or confidential reporting as an appropriate protection. However, we consider that the submission of anonymous reports poses some contradictions with the implementation of a duty on individuals. It will be in the reporter’s interest to ensure the actions they have taken in respect of the duty are clearly documented, and agencies to which reports are made will be in a better position to make an accurate assessment of risk if they understand the full context of the referral. However, we understand that in some cases a reporter may feel at risk if their role is identified (for example, to those involved in perpetrating the disclosed abuse). Through statutory guidance, we will provide clarity to relevant agencies on how a reporter’s details should be handled from the point of a report being made; including that it should be made available only to those who require it.

More broadly, we believe an effective form of ‘protection’ for reporters will be a system-wide improvement in reporting cultures in relation to child sexual abuse and normalisation of ‘speaking out’. Acknowledging that this is likely to require a long-term cultural shift, the implementation of a mandatory reporting duty will nevertheless be an important catalyst. Since the Government announced its intention to introduce mandatory reporting in April 2023, we have provided the NSPCC with £1.6m to supplement the provision of national helpline services on child sexual abuse and whistleblowing and improve public awareness of this underreported crime through a national campaign.

We heard that the formulation of protections for reporters must not interfere with the general principle of privacy owed to children and their families; or the ability of the regulatory system to scrutinise risks to public protection. We fully agree with the need to ensure frictionless implementation and will ensure that policy development in this space does not encroach on the work of any inspectorates or regulators.

A small number of respondents set out the view that personal protections for reporters are not necessary, and others stated that meaningful protections cannot really be provided by Government.

Q: In addition to the exception for consensual peer relationships, are there any other circumstances in which you believe individuals should be exempt from reporting an incident under the duty?

- No other exemptions

- Disclosure relates to historical abuse and there is no risk of further harm present

- Considerations should be made to how children with special educational needs or disabilities are included in any proposed exemptions

- There should be categories or thresholds of abuse for reporting, with some situations exempt

- In situations where there are poor provisions for reporting, individuals subject to the duty should be exempt from reporting

- Lack of mental capacity involved

- Children and young people should be able to veto a report being made about their disclosure

- Specific role exemptions (patient confidentiality, seal of the confessional)

- Disclosure is believed to be malicious reporting

- Other: including an exemption where safety of the reporter or the child/young person would be threatened by a report being made; where a report would put live investigations into jeopardy; when it is established that a report has already been made by another professional.

Commentary

The overwhelming response to this consultation question indicated that no further exemptions should apply to the reporting duty.

Whilst not specifically raised by the consultation question, many respondents used this opportunity to provide additional commentary on the exemption for consensual teenage relationships designed by the Inquiry. Some expressed concern as to the practical complexity implied by the need to assess relative ages, maturity and the possibility of exploitation or coercion. Health stakeholders raised concerns that an exemption which is not wide enough to capture all consensual sexual activity between young people could deter children and teenagers from accessing sexual and reproductive healthcare services. Others warned that the exemption has the potential to create a loophole for abuse to continue, for example where a young person believes and states to reporters that an exploitative relationship is consensual (as is likely to be the case in instances of grooming). We will consider all these issues in the drafting of legislative measures and statutory guidance to support the exemption. However, it is important to give effect to the intent of the Inquiry’s exemption recommendation – which was designed to avoid undue interference with teenagers developing healthy relationships. The fact that this activity does not trigger the mandatory reporting duty does not mean it should be met by indifference or inaction by those in positions of responsibility for children. Guidance relating to the duty will make clear that sexual relationships involving teenagers under the age of consent should be referred to an appropriate agency for advice where appropriate. We will make explicit the links between this point and wider work across Government to tackle peer-on-peer sexual abuse and the development of harmful sexual behaviour.

Some responses to this question discussed the concept of ‘adultification’ (particularly in relation to black children) and how it may impact the application of an exemption based on the assessment of age or maturity. We have considered this feedback as part of our equalities impact assessment, and will continue to do so as we develop our plans for implementation.

Some health sector respondents were concerned that disclosures or confessions made to reporters while lacking mental capacity – for example, the expression of false memories or delusions during a mental health crisis – would have to be reported under the duty. We will ensure that the duty excludes cases where a suitable professional has assessed, with a reasonable foundation, that a disclosure or confession is not genuine and results from a person’s mental illness.

While not an exemption to the duty, we have reflected on feedback from some respondents on the need to accommodate the wider personal context in which a disclosure of child sexual abuse may be made. Accordingly, we will provide that a report under the duty can be delayed where this is judged by the reporter to be in best interests of the child. This will accommodate scenarios in which (for example) a child or young person is undergoing an immediate personal crisis. This will not allow for indefinite delays, and statutory guidance will make clear that any decisions to delay should be clearly documented and regularly reviewed.

The consultation received several representations setting out the view that an exemption to the mandatory reporting duty should be made in respect of sacramental confession. This is a proposal which was explicitly rejected by the Inquiry in setting out its recommendation on mandatory reporting. We are considering the implications of the duty on Article 9 of the European Convention on Human Rights (the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion) and will publish our assessment in respect of any final legislative measures.

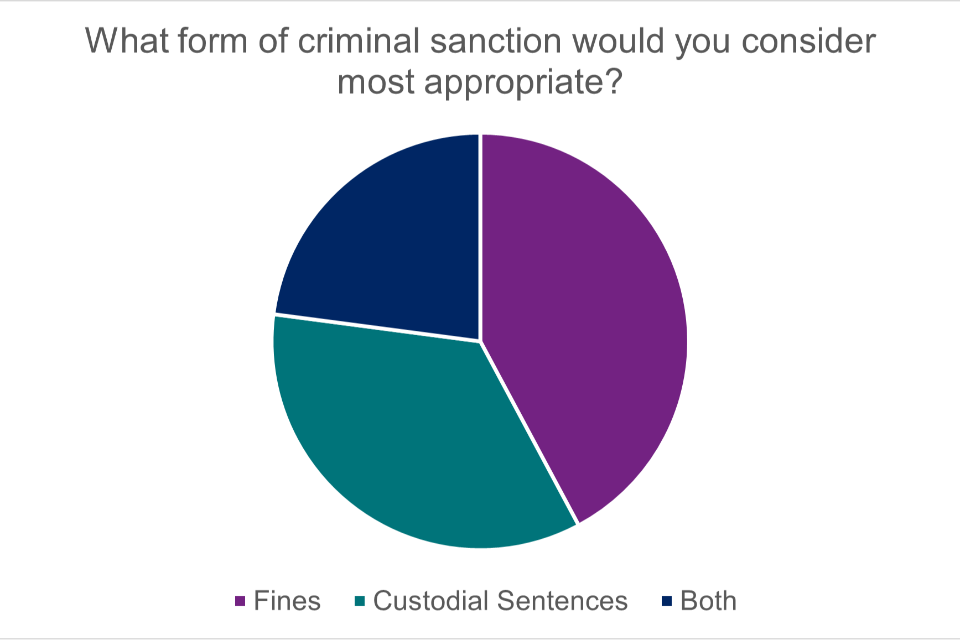

Q: We are proposing that there would be criminal sanctions where deliberate actions have been taken to obstruct a report being made under the duty. What form of criminal sanction would you consider most appropriate?

Commentary

Responses to this question indicated a reasonably even split between the options provided. We will reflect on this feedback as we develop legislative measures, keeping open the option of fines, imprisonment, or both applying on conviction.

Representatives of the voluntary sector raised concerns over potential liability for fines on smaller charities and other organisations with limited income. Their responses discussed the wider impact on child protection and safeguarding if such (often specialist) services were to be forced to close over the payment of fines. We are clear that liability will extend to the person engaging in such conduct, and not organisations.

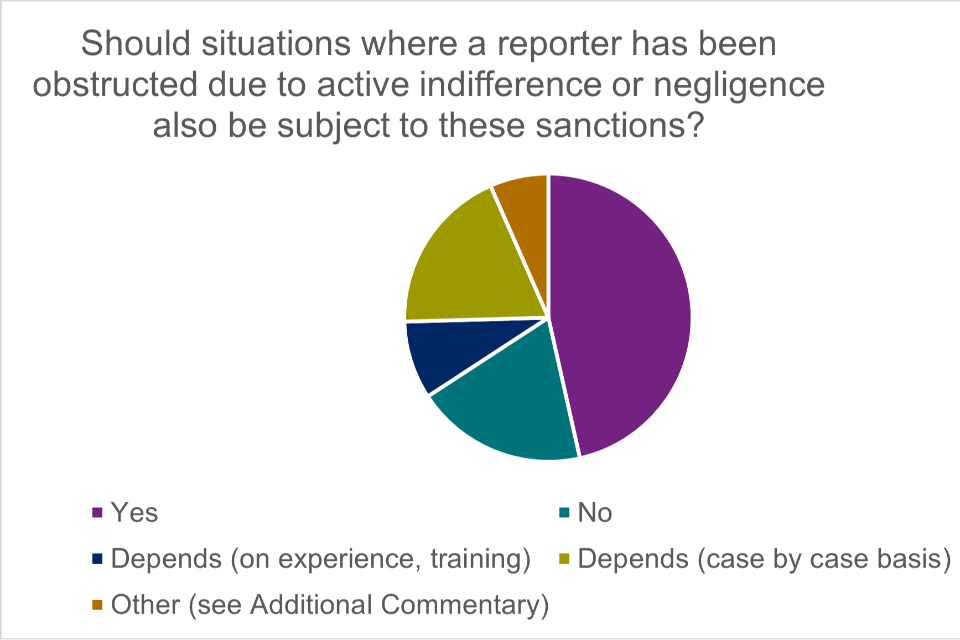

Q: Should situations where a reporter has been obstructed due to active indifference or negligence also be subject to these sanctions?

Commentary

While a significant amount of respondents answered ‘yes’ to this question, it was also widely acknowledged that defining or judging such behaviours would be very challenging. In addition to this being an objectively difficult assessment to make (and evidence), respondents were concerned about the potential for inconsistency of standards and approach across the various sectors the mandatory reporting duty will apply to.

We are mindful that there will likely be overlap to consider in such cases relating to the role and involvement of regulators; who may to consider active indifference or negligence in the face of child sexual abuse concerns a fitness-to-practice issue. Engagement with those responsible for regulating the different sectors involved in mandatory reporting will be factored into our implementation plans.

We recognise that reporters themselves will need clarity on what to do if their duty to report is being obstructed by negligence or active indifference. This will be covered in statutory guidance in respect of the mandatory reporting duty. We will also ensure the definition of obstructive conduct is made clear in our legislative measures and any associated guidance, reflecting the responses to this question.

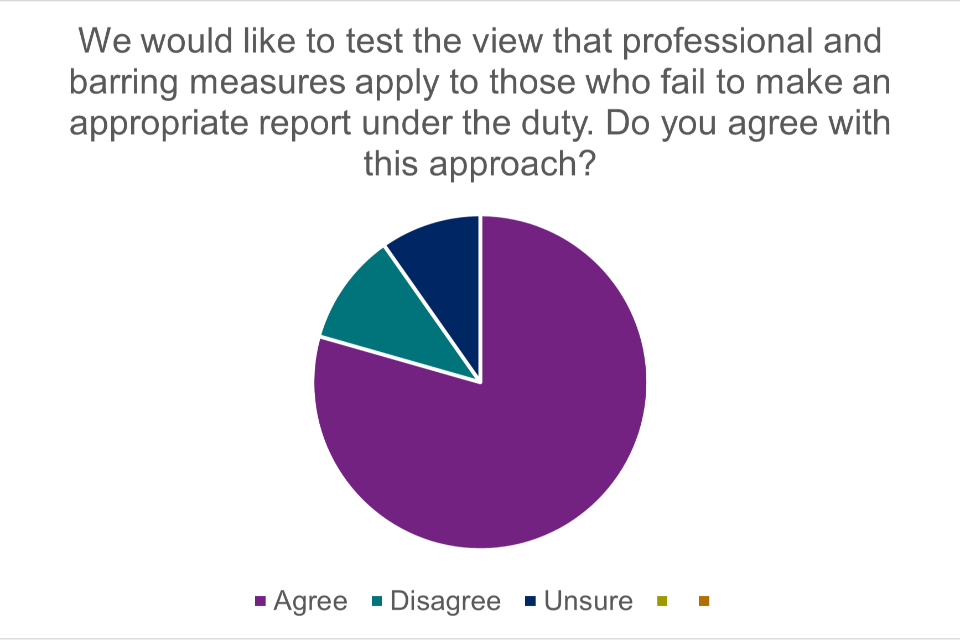

Q: We would like to test the view that professional and barring measures apply to those who fail to make an appropriate report under the duty. Do you agree with this approach? Would different situations merit different levels or types of penalty?

Commentary

There was overwhelming agreement with this approach from those who expressed a clear view. Where respondents provided details to support their answer, there was consensus that different scenarios could merit different penalties; with the level of ‘intentionality’ behind the failure to report often considered to be the right determinant factor.

Those disagreeing with the approach set out several reasons for their views, including that barring an individual from paid work would be disproportionate; and in a few cases disagreeing with the fundamental premise that any action should be taken against those who fail to report abuse.

A common request from respondents was for the Government to set out clear advice on process in advance for those involved in implementing the duty (for example, how to action a referral to the Disclosure and Barring Service). Several mentioned the need for Government to ensure consistency between regulators given wide range of sectors a mandatory reporting duty will apply to. We will address these points both through statutory guidance and implementation planning.

Q: Are there any costs or benefits which you think will be generated by the introduction of the proposed duty which have not been set out in the attached impact assessment?

Costs:

- Financial and wider resource costs of increased reporting

- Training and awareness raising

- Recruitment and retention of staff being negatively impacted

- Emotional harm to children and young people in having to detail their abuse

- Chilling effect on the willingness of children and young people to discuss abuse

- Other costs: including supporting whistle-blowers, changing reporting systems de-prioritisation of other forms of abuse, supporting siblings and non-abusing parents

Benefits:

- Improved safeguarding of children and reduction in child sexual abuse

- Increased awareness and reporting of child sexual abuse

- Faster identification of, and more evidence against, perpetrators

- Other benefits: including acknowledging the courage and contribution of those who participated in the Independent Inquiry, reducing ambiguity in reporting processes

Commentary

Responses to this question indicated a general sense of uncertainty over costs and benefits, with some making the point that this underscores the need to evaluate the impact of the duty in future.

There was widespread commentary that victim support services and therapeutic support will see an increase in demand. Similar points were made in respect of required placements for looked-after children. The Government is taking forward separate action in respect of these issues (recommendation 16 of the Inquiry, and Stable Homes Built on Love). We will ensure that communication and engagement with impacted workforces prior to commencement of the duty reflects their specific needs.

We acknowledge the feedback provided by many respondents that familiarisation costs assumed by the consultation impact assessment are unrealistically low. Work is being undertaken to update these figures accordingly.

Q: In light of the proposals outlined in this paper, what are the key implementation challenges and solutions reporters and organisations will face?

Challenges:

- Adjusting to the new duty with limited resources and time available

- Impact of potential over-reporting

- Reporting against a child or young person’s wishes - impact on trusted relationships

- Recruitment and retention of staff to roles subject to the duty

- Changes to pre-employment screening and employment contracts

- Additional difficulty in attracting/appointing designated safeguarding leads

Solutions:

- Training, toolkits

- Increasing skills and awareness

- Government policies and guidance

- Clear and effective reporting pathways and systems

- Additional funding or grants

- Protections for reporters

- Audits and monitoring of compliance with the new duty

- Sufficient time to prepare for implementation

- Improved multi-agency working between child protection agencies

Commentary

Many respondents reflected on the wide, cross-sector application of the mandatory reporting duty to various roles and the different levels of awareness, competence and confidence that will exist across such a broad group. We accept and acknowledge this as an inherent feature of the proposals. Ensuring that the mandatory reporting duty is kept as simple and straightforward as possible has been a priority throughout the policy development process. Impacted sectors will consider any training and materials needed to support their workforces in delivering the duty and improving their response to child sexual abuse. As mentioned elsewhere in this report, delivering a consistency of approach to reporting, and aligning with wider child protection and safeguarding reforms, will be key points of focus as we consider implementation.

Some provided general commentary on the expected administrative burden of adjusting to the new duty (through updating policies, refreshing terms in standard contracts etc.). Other specific concerns were the need for guidance on how to manage vexatious protests against the duty; and the need to consider alignment with the legal frameworks for reporting abuse in the devolved administrations of the United Kingdom.

Other respondents used this question to register their views on the specific equalities considerations which might be applicable to children and young people with protected characteristics. We are grateful for these insights, which have been considered and reflected in the our equalities impact assessment.

Impact Assessment and Equalities

Impact Assessment

An impact assessment was prepared in respect of our consultation proposals. We are currently updating this document, including to:

- Reflect the new criminal offence of obstructing a reporter and its potential impact on prison places, HM Courts & Tribunals Service, Legal Aid and police costs.

- Update the stated familiarisation costs to take into account feedback received on length of necessary guidance issued; as well as revising workforce statistics.

A final version of the analysis will be published as part of the overarching Criminal Justice Bill impact assessment in due course.

Equalities

An equalities impact assessment has been prepared in light of the consultation responses to consider likely impacts on people with protected characteristics: disability, race, sex, gender reassignment, age, religion or belief, sexual orientation, pregnancy and maternity, marriage and civil partnership. The equalities impact assessment has been published alongside this consultation response.

Where equalities impacts from our policy proposals have been identified, we have included a proportionate mitigation where necessary. The equalities impact assessment will continue to be reviewed and updated in line with our responsibilities under the Public Sector Equality Duty (PSED).

More information on the PSED can be found here: Equality and diversity - Home Office - GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

Conclusion and next steps

We are grateful to everyone who took the time to share their views, insights and expertise throughout the consultation process. A summary of how responses to the consultation have been reflected in our development of the policy is presented below at Annex B.

The mandatory reporting duty will, first and foremost, be a safeguarding measure. It will ensure that the words of children and young people who are seeking help are heard. It sets high standards of conduct and provides reporters with clear instructions on how to act when they are made aware of child sexual abuse. A report made under the duty is simply that – sharing information with the appropriate agencies, who can consider it further and take appropriate action to safeguard and support the child involved where necessary. We have not attached criminal penalties to the failures under the reporting duty, considering referrals to the Disclosure and Barring Service (and professional regulators where applicable) to be a more appropriate outcome. However, the reporting duty itself is accompanied by tough, punitive measures for anyone who seeks to cover up abuse. An individual who seeks to obstruct a reporter from carrying out their duty to report will face the prospect of up to seven years imprisonment. As we implement the introduction of the duty, we will continue to deliver the work outlined in the Government’s Tackling Child Sexual Abuse Strategy; ensuring professionals working with children have the skills and information they need to recognise and respond appropriately to all forms of child sexual abuse.

In presenting its final report to Government, the Inquiry reflected on the words of a participant in the Truth Project when describing their experience of disclosing child sexual abuse: “All I needed was just one person to act”.

“All I needed was just one person to act.”

Amongst those who did disclose child sexual abuse at the time, the majority said that they did not receive the help and protection that they needed. Victims and survivors often said that the person to whom they disclosed responded inadequately. Many victims and survivors were accused of lying, were blamed or were silenced. These experiences were common, whether victims and survivors disclosed as children in the 1950s or 2010s.

The Report of the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse (October 2022) p.137[footnote 1]

In closing this consultation report, we are conscious that this specific measure cannot, in isolation, resolve the complex reasons for the widespread under-reporting of child sexual abuse. But by introducing a mandatory duty to report child sexual abuse, we will ensure children and young people have the confidence to know that their disclosure will be taken seriously and actioned appropriately. We will provide clarity and consistency to the activities of those responsible for the welfare of children. And in so doing, we will also ensure the continuation of a vital national conversation on this hidden crime.

Next Steps

- The Home Secretary informed Parliament in January that the duty will be brought forward as an amendment to the Criminal Justice Bill, which is currently before the Commons.

- We will consider implementation aspects of the mandatory reporting duty, drawing on the outcomes of this consultation, to ensure an effective and consistent roll-out. Upon the Criminal Justice Bill receiving Royal Assent, we will allow a necessary time period for impacted workforces to update relevant policies and processes (and undertake a process of familiarisation) before commencing the duty.

- We will evaluate the operation of the duty after a specified period following its commencement, which will consider the impact of the duty on outcomes for children and young people, as well as system operations.

- We will maintain the engagement with stakeholders which underpinned this consultation, both to inform our implementation strategy and to assist in informing the evaluation of the operation of the duty.

Consultation principles

The principles that Government departments and other public bodies should adopt for engaging stakeholders when developing policy and legislation are set out in the Cabinet Office Consultation Principles 2018:

Consultation principles: guidance - GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

Annex A: Call for evidence (May – August 2023)

Call for evidence: summary

The consultation was preceded and informed by a call for evidence exercise which took place between May – August 2023. It attracted over one thousand responses: 993 responses to the online survey, and 68 submissions to our dedicated mailbox. It enabled the Government to consider a wide range of perspectives and ideas to develop the proposals set out in the November consultation.

The call for evidence demonstrated several areas of broad agreement with the Inquiry’s recommendation. For example, the range of reporters recommended by the Inquiry was generally considered to be appropriate, and the majority agreed with the concept of introducing a duty on relevant organisations, as well as individuals. Many noted the wider potential benefits of a new duty, for example in terms of improving awareness of child sexual abuse and giving young people greater confidence they will be listened to. Other positive impacts discussed include delivering culture change through greater accountability for organisations, reducing the likelihood of institutional ‘cover-ups’ and scapegoating of individuals. There was also agreement on the critical importance of ensuring the new duty contains appropriate protection for individuals who are making their reports in good faith.

There were also points on which opinions were mixed. Respondents were split on whether breaching the duty should be a criminal offence, with many saying different forms of punishment should be available based on the context and severity of failures. While the Inquiry recommended that the duty exclude non-harmful relationships between young people from reporting, respondents were divided on the question of there being exceptions to the duty more generally. While most agreed that young people should not be criminalised for being in a consensual relationship, there was widespread recognition that understanding and making judgements on relationships between young people could be highly challenging for those tasked with reporting. Views were also split on the question of what should be reported. Those who believed reporters should only be under a duty to report when they are directly told of sexual abuse by a child or perpetrator (or witness it themselves) often mentioned the need for clarity and consistency in order to deliver a manageable system. Respondents who believed that individuals under the duty should also make a report when they observe ‘recognised indicators’ of sexual abuse often highlighted the importance of early identification preventing more severe harm (with widespread recognition, however, that identifying the indicators of sexual abuse is a sensitive and complex task even for well-trained professionals).

Many respondents expressed concern around the potential negative impacts of implementing a new duty, from overburdening public services, lowering the quality of referrals to safeguarding agencies and reducing the amount of ‘safe spaces’ available to children and young people who may wish to discuss sexual abuse in confidence. There were also concerns raised around the potential for a new duty to be misused through false and malicious reporting. Comments on these points were generally in agreement that there would be a strong need for guidance and training relating to the new duty as well as clear, consistent processes and thresholds.

Methodology

- Please see the ‘Methodology’ section above for a description of how the call for evidence data was analysed.

Call for Evidence Questions

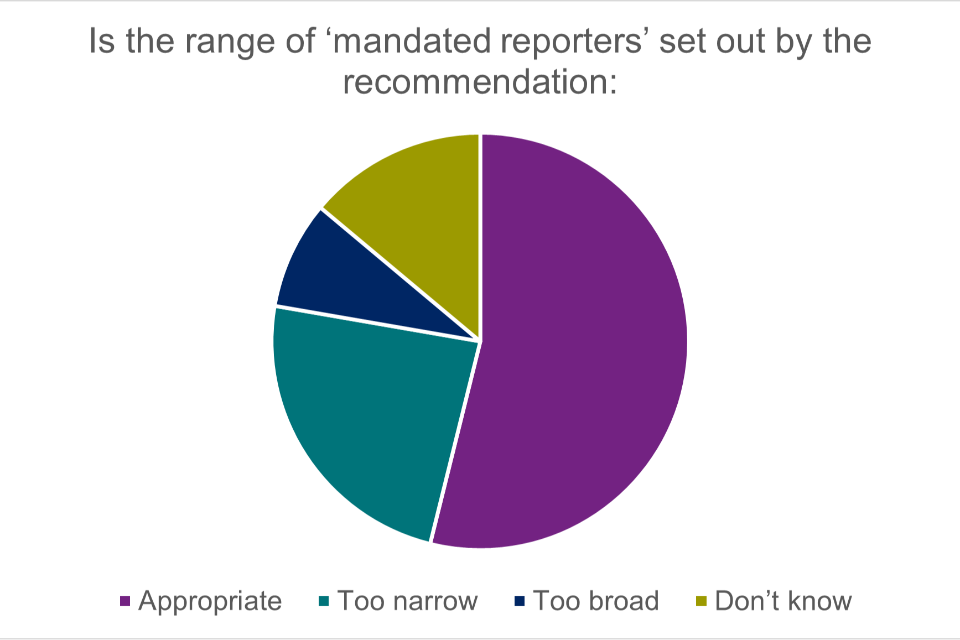

Q: Is the range of ‘mandated reporters’ set out by the recommendation (people working in regulated activity with children under the Safeguarding and Vulnerable Groups Act 2006, people in positions of trust as defined by the Sexual Offences Act 2003 and police officers): (Select one)

☐ Appropriate

☐ Too narrow

☐ Too broad

☐ Don’t know

Please provide details to explain your response

A large amount of respondents expressed a view that a mandatory reporting duty should apply to the general population, with some specifying that parents, foster carers and neighbours in particular should be included. This tended to be on the basis that peer abuse and familial abuse would not necessarily be captured by the duty as written.

A significant amount of responses expressed agreement that the range of mandated reporters as set out by the Independent Inquiry is appropriate.

Others highlighted potential gaps in the definition proposed by the Inquiry (e.g., therapists), and mentioned concerns the fact that the duty will not cover vulnerable young adults in the 18-25 year old age bracket.

Some respondents mentioned the difficult position faced by industries which lack the oversight of a national governing body (e.g. dance instruction) and the wider position of unregulated activities for children.

Several respondents mentioned the need for this work to be aligned with the Independent Review of the Disclosure and Barring Service and any future changes to regulated activity definitions.

There were a small amount of responses (on both sides of the question) relating to potential impact of the duty on religious communities and structures – some were very clear in their view that seal of confession cannot be permitted to be treated as an exemption, while others flagged the potential for intervention here to be in breach of the European Convention on Human Rights (specifically the freedom of thought, conscience and religion).

Responses also provided wider general commentary on the need for awareness raising work to be undertaken in respect of impacted individuals in certain roles who may not know enough about safeguarding processes.

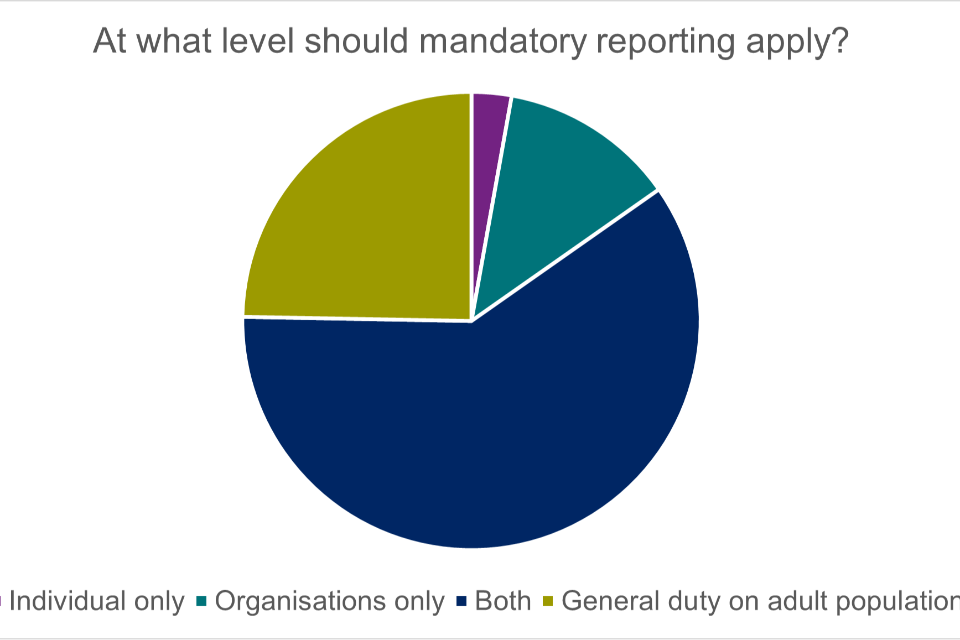

Q: At what level should mandatory reporting apply?

Responses to this question indicated a significant level of support for widening the scope of the Inquiry’s recommendation, either to include organisations or the general adult population.

Q: If you selected ‘Only at an organisational level (bodies, institutions or groups) / Both individual and organisational level’ in response to the question (At what level should mandatory reporting apply?). Which organisations or groups should it apply to?

Many respondents considered that all statutory partners and education settings should be accounted for under any new duty, while acknowledging that many, if not all, will already have statutory reporting duties.

Early years settings were commonly mentioned, alongside alternative provision, private schools, boarding schools, special residentials schools, and tuition settings. However, responses also reflected concern over the potential negative impact on safeguarding of overburdening professionals in this sector.

Some considered that mandating charities and the voluntary sector to report may result in children opt out of disclosing to a trusted adult. However, applying to duty to charities and the voluntary sector was generally considered to be necessary regardless of this risk.

Faith organisations, groups and leaders, sports organisations and clubs were noted as important settings to capture, largely justified by reference to examples of historical inadequate responses. Foster carers and staff within care homes were also flagged. Adult services were also suggested as an organisation which should be in scope, in order to facilitate the reporting of historical allegations.

Some recommended that the duty only apply to reports in relation children up to 16 years of age. Other responses however recommended extending the age to 25 years of age, particularly in respect of vulnerable young adults.

For organisations to undertake the duty, improvements were considered to be needed in respect of existing infrastructure to support a potential uptick in reporting. Many responses agreed that organisations and individuals would need appropriate training.

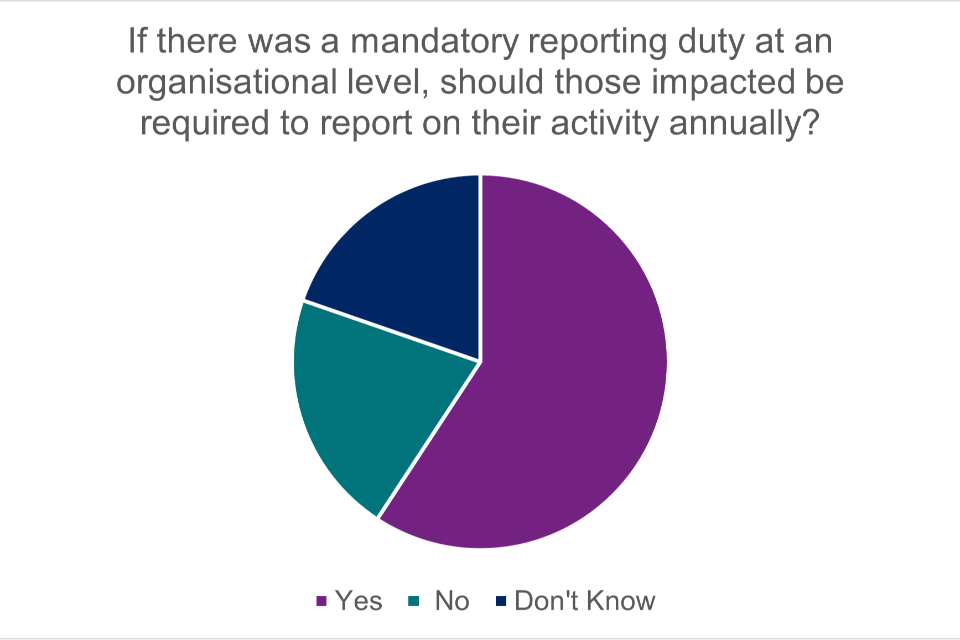

Q: If there was a mandatory reporting duty at an organisational level, should those impacted be required to report on their activity annually?

The responses to this question indicated a general agreement with the premise of a regular reporting requirement on organisations (if the duty were to apply at that level).

Q: If you selected ‘Yes’ in response to the question (If there was a mandatory reporting duty at an organisational level, should those impacted be required to report on their activity annually?) What form should that reporting take?

The most common response to this question described a regularly published annual return setting out anonymised quantitative data on reports of child sexual abuse and any subsequent actions taken.

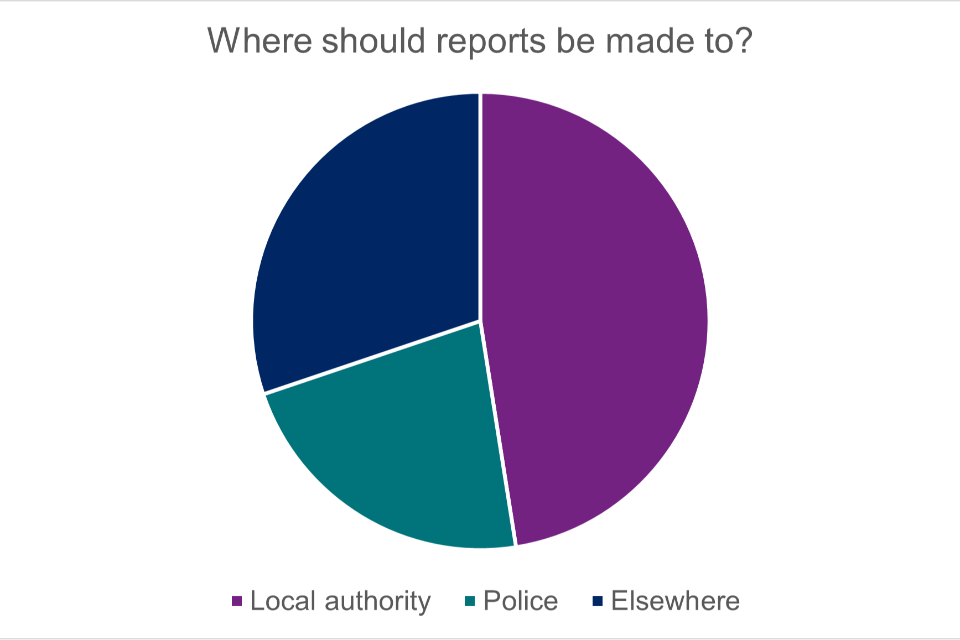

Some responses discussed where any organisational-level reports should be sent. This generally fell into two categories – national level oversight (e.g. a central Government department) or local safeguarding partnership structures. Responses suggesting the former tended to reflect on the importance of ensuring accountability and identifying trends through data; while the latter suggestions focused more on ensuring the reports went to those with statutory powers to investigate and holding a role in improving local practice. A small number of respondents suggested reports should go to an independent central body such as the NSPCC, or a newly created child protection authority.

Other common themes were the importance of simple, standardised forms for completion, which could for example be made easily accessible through an online portal. This was generally suggested in view of the need to minimise additional bureaucracy wherever possible, and on this theme many respondents also suggested that existing reporting routes (e.g. Designated Safeguarding Leads) should be utilised wherever possible, rather than creating a new process.

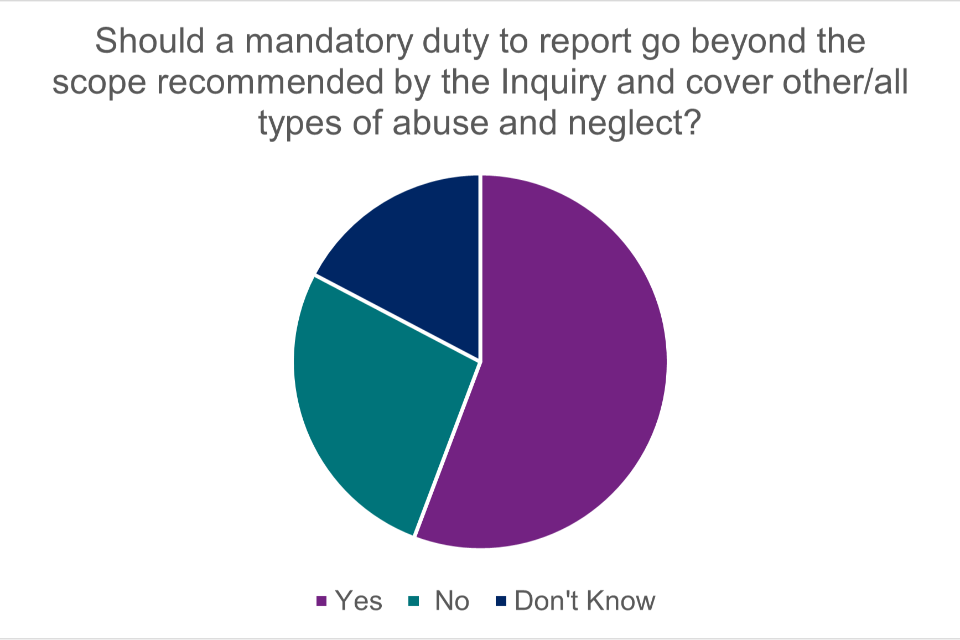

Q: Should a mandatory duty to report go beyond the scope recommended by the Inquiry and cover other/all types of abuse and neglect?

The responses to this question indicated a significant amount of support for widening the scope of a mandatory reporting duty to other forms of abuse.

Q: If you selected ‘Yes’ in response to the question (Should a mandatory duty to report go beyond the scope recommended by the Inquiry and cover other/all types of abuse and neglect?). Which types of abuse and/or neglect do you think should be covered?

A large amount of responses indicated that all forms of abuse should be covered, with strong levels of support also expressed for the mandatory reporting of physical abuse. A smaller amount suggested that mandatory reporting should apply to neglect and emotional abuse.

Other types of abuse respondents suggested should be included in a mandatory reporting duty included financial abuse, modern slavery, radicalisation and domestic abuse.

Q: What impacts (positive or negative) do you think a mandatory reporting duty would have on: Children choosing to make a disclosure, either partially or in full?

Responses to this question were mixed fairly evenly between the positive and negative impacts. The majority of positive responses fell into the categories of increased confidence that action will be taken, and an improvement in children feeling listened to and protected.

Most of the responses discussing negative impacts cited the potential unintended consequence of dissuading children and young people from making a disclosure if they are aware a subsequent report must be made.

Many responses differentiated between the potential impacts on younger children and older children, mentioning that it could be more difficult for older children to make a disclosure due to fear of losing their autonomy or control of a personal situation.

Numerous responses noted that children and young people will need to be informed of the process, and a requirement for support to be made available to them after making a disclosure of sexual abuse. Several responses stated that a disclosure of this kind is often not a singular event, but rather an ongoing process throughout which a young person must be supported appropriately.

Q: What impacts (positive or negative) do you think a mandatory reporting duty would have on: Individuals within scope of the duty reporting known / suspected incidents?

There was strong agreement that training and clear guidance to support professionals will be essential to the success of the duty. A lack of sufficient clarity and the fear of getting things wrong were cited as a key reason for present under-reporting.

Common positive themes that emerged from the responses were that mandatory reporting could empower individuals to report by clarifying their responsibilities and the appropriate reporting pathways, as well as creating a more robust safeguarding environment with better-informed professionals.

Common negative themes that emerged from the responses included the fear that professionals would adopt an over-cautious or incurious approach to child sexual abuse and overreport minor suspicions for fear of punitive action if a mistake is made. Some respondents felt that the duty could create an environment where false accusations, reprisals against reporters and overstretched staff were common.

A number of respondents were concerned that the duty could result in reporters “deliberately avoiding situations where they may be disclosed to”, and others described reporting child sexual abuse and safeguarding concerns as “breaking victim’s anonymity”.

Q: What impacts (positive or negative) do you think a mandatory reporting duty would have on: Organisations within scope of the duty reporting known / suspected incidents?

The responses to this question were more likely to discuss potential negative impacts, either believing mandatory reporting would have little effect (due to reporting already taking place or a belief that it will not be executed well), or that the wider consequences of reporting would be substantial for impacted organisations.

Responses highlighted that an increased level of resource and funding would be needed to support many struggling sectors. For organisations who rely on volunteers, there were concerns that mandatory reporting responsibilities could make recruitment more difficult by deterring prospective volunteers. These organisations also highlighted the relative difficulty they anticipated in ensuring the compliance of volunteers with reporting requirements.

Concerns were raised about the impact mandatory reporting would have on confidential services and whether victims, survivors and their families would still be willing to come forward to disclose abuse when fearing negative outcomes or involvement from statutory services.

Respondents also highlighted reputational and legal consequences as a barrier to organisations enforcing mandatory reporting effectively. For example, some considered that fear of being labelled as having an ‘issue’ with child sexual abuse could deter organisations from reporting. Others were concerned that the potential legal liability could encourage staff to only report where they were highly confident that abuse had occurred. Some respondents suggested that the scope of mandatory reporting should be narrower, or that the onus should be placed centrally within an organisation rather than on the individual to ensure correct processes are being followed.

Those who responded positively felt mandatory reporting would ensure greater accountability for organisations, and would strongly disincentivise organisations from ‘covering up’ or hiding abuse. Mandatory reporting could also give clarity to organisations about their responsibilities and encourage them to improve their internal policies and processes, therefore empowering staff and making space for appropriate whistle-blowing in organisations with poor reporting cultures. Others considered that mandatory reporting would improve multi-agency working, particularly around the important issue of information sharing. It was also suggested that mandatory reporting could lead to better data collection, which could help to identify hotspots of abuse where greater resource could be placed.

Q: What impacts (positive or negative) do you think a mandatory reporting duty would have on: Individuals outside the scope of the duty reporting known / suspected incidents?

There was a strong theme of respondents recognising that the introduction of a duty could be an important lever in improving awareness of child sexual abuse, and the culture of reporting child abuse more generally.

Respondents also expressed their concern over potential unintended consequences in relation to this question. The issue most commonly raised was the risk of a new duty being taken to imply that reporting child sexual abuse was a responsibility only for the legally defined cohort of ‘mandated reporters’. Some felt this had the potential to undermine established Government messaging that child safeguarding is ‘everyone’s business’. For some this point served to underline the importance of Government undertaking awareness-raising campaigns on the issue of child sexual abuse and reporting responsibilities, as recommended elsewhere in the Independent Inquiry’s final report.

A small number of respondents expressed the view that there would be no impact on reporting by individuals outside the scope of a new duty.

Q: What impacts (positive or negative) do you think a mandatory reporting duty would have on: Organisations outside the scope of the duty reporting known / suspected incidents?

A key theme in response to this question was the implied introduction of a hierarchy in reporting responsibilities – for example, non-mandated organisations feeling devalued, or the potential to fuel a perception that reports are only to be made by a particular set of organisations. The view was again expressed that this could cut across long-standing messaging that child safeguarding is ‘everyone’s business’.

Respondents expressed concern that a mandatory reporting duty may increase the amount of disclosures being made to settings or individuals outside of the duty’s scope, as they could be seen as a ‘safe space’ to discuss sexual abuse.

The potential for the duty’s introduction to generate cultural in attitudes to reporting was generally recognised as a positive. Even if not in scope of a mandatory duty, many respondents considered that all organisations should be encouraged to report child sexual abuse. The ability to access clearly understood, non-statutory reporting guidance was considered an important tool in supporting such efforts.

It was mentioned that those organisations not subject to a mandatory reporting duty could eventually be considered less attractive to commissioning bodies such as the NHS, local authorities etc., unless voluntarily matching the requirements of a mandated organisation.

Q: What impacts (positive or negative) do you think a mandatory reporting duty would have on: Agencies in the wider safeguarding system that are required to respond to reports of abuse?

A strong theme emerged from responses to this question that a duty to report could increase workloads across already stretched workforces, and that additional funding and resourcing would therefore be needed. Many of these views recognised that the impact would be a great deal higher if mandatory reporting applied to ‘indicators’ or suspicions, rather than disclosures.

Balancing that view was a common recognition that an impact on workload is not a good enough reason to hold back from implementing a measure that would keep more children safe from child sexual abuse. Related points were also made regarding the potential for tackling child sexual abuse to offset wider societal costs of support and intervention in later life.

Respondents also reflected that a mandatory duty to report does not require mandatory action in response to a report, and that effective triage and information sharing could prevent disproportionate impacts on workload. This linked to a number of comments that compliance with a mandatory reporting duty would generate improvements to multi-agency working and information sharing. Respondents also expressed the view that a duty could serve to increase clarity of process and improve accountability for failures.

Other responses underlined the need for strong protections akin to whistleblowing policies to be in place for those making reports under the duty.

Q: What impacts (positive or negative) do you think a mandatory reporting duty would have on: Members of the public?

A number of potential negative impacts came through as consistent themes in response to this question. These included fears that individuals with important information on child sexual abuse assuming others (mandated reporters) will take the lead. Responses also discussed a reporter’s fear of reprisals from those involved in the abuse; as well as the fear of criminal consequences deterring people from seeking informal advice where they are unsure what to do. False or malicious reporting was also raised as a concern, as was the potential for high volumes of poor-quality referrals obscuring more serious concerns. Some considered that people would be less likely to volunteer or work with young people for fear of being falsely accused of sexual abuse, and a report subsequently being made under the duty.

Several positive impacts were also discussed by respondents. A common one was the improvement in public confidence and awareness that child sexual abuse is being identified and dealt with, with more members of the public knowing that children are protected and that they are safer. Respondents also considered the positive impact on reporting culture and awareness of child sexual abuse as an issue, and the strong message of zero tolerance that the introduction of a duty would send to perpetrators.

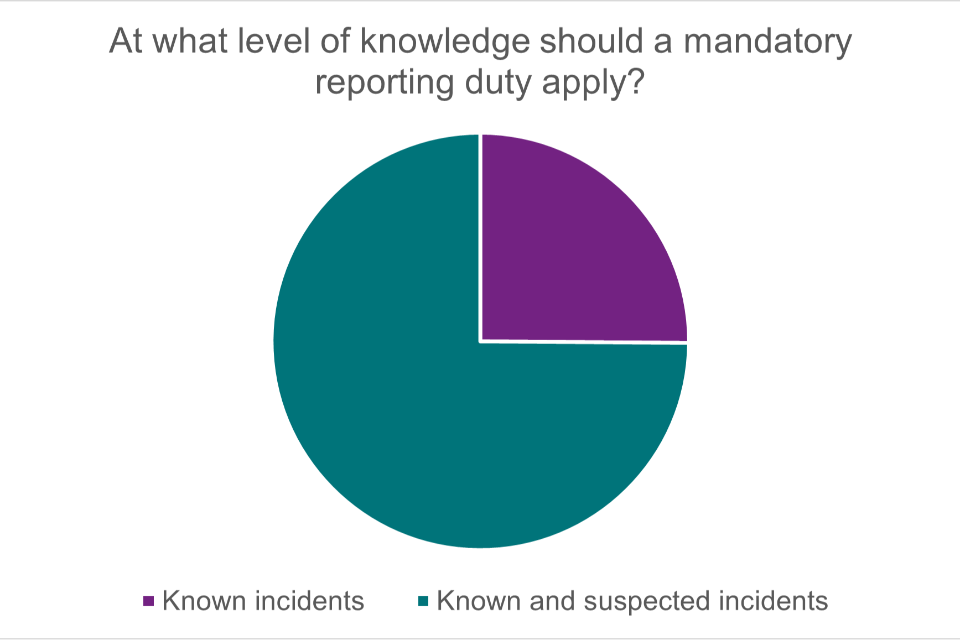

Q: At what level of knowledge should a mandatory reporting duty apply? (Select one)

☐ Restricted to known incidents of abuse

☐ Both known and suspected incidents of abuse (based on recognised indicators of abuse)

Please provide details to explain your selection

There were strong views expressed on both sides when considering whether the duty should apply to known or known and suspected incidents of abuse.

The key arguments for focusing on known abuse only included: greater clarity and consistency, reflecting the reality that assessing indicators can be complex and subjective; resulting in a more realistic and manageable duty for non-experts. Recognising indicators of abuse was mentioned by several respondents as being particularly problematic for those working in infrequent or irregular settings. Additionally, this approach was considered to tie the duty more closely to the deliberate concealment or withholding of disclosures which have been made by children and young people.

The key arguments for including suspected incidents of abuse in the duty included: greater opportunities to secure the prevention of further harm; making clear that children are not responsible for their own safeguarding; and the importance of establishing and identifying patterns in addressing abuse.

Respondents frequently mentioned the impact of communication difficulties impacting rates of disclosure, with particular considerations expressed for children with special educational needs and disabilities, and those for whom English is a secondary language.

Many respondents used this question to register their view that extensive supporting guidance will be required to specify appropriate timeframes for reporting and a list of recognised indicators relating to child sexual abuse.

Q: What should be considered a ‘disclosure’ of abuse?

Many respondents agreed that ‘disclosure’ of abuse could fall into a number of categories, including direct verbal disclosures by the child and indirect disclosure (including through writing, drawings and play). Wider indicators highlighted by respondents include changes in the child’s behaviour, physical indicators of abuse (including marks on their body or evidence, such as a photo), abuse that meets existing guidance and thresholds, and disclosure by the perpetrator.

Some respondents stated that disclosure should be a direct verbal disclosure from the child only. Others emphasised the importance of non-verbal disclosure to children who may not have the knowledge, language or ability to describe what has happened to them. Where concerns were raised, a large number of respondents stated that the Government’s definition of disclosure needs to be “unambiguous” and “fit for purpose in the context of criminal sanctions”. There was also common agreement that robust statutory guidance “must provide clear direction” to professions in scope of the duty, and that this should be supplemented by training.

There was recognition among some respondents that disclosure can take place over a long period of time, rather than being a singular incident. Some of these respondents were anxious that a system which mandates the reporting of any initial disclosure risks harming trusted relationships with children and young people.

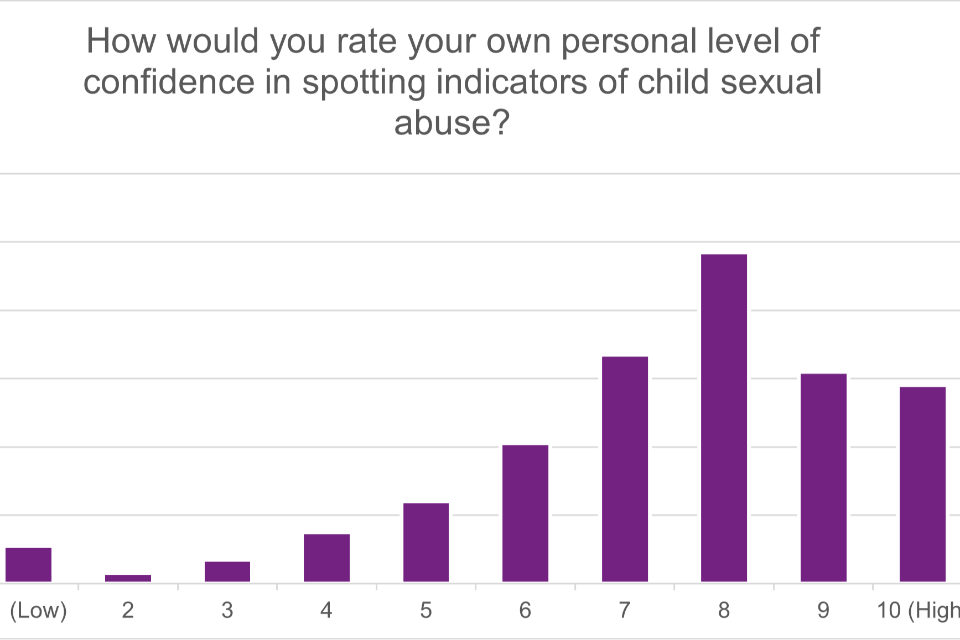

Q: The Inquiry calls for ‘recognised indicators of child sexual abuse’, which are unspecified, to be set out in guidance and regularly updated – how would you rate your own personal level of confidence in spotting indicators of child sexual abuse?

Indicate on a scale between 1-10 [1: low confidence, 10: fully confident]

☐1 ☐2 ☐3 ☐4 ☐ 5 ☐6 ☐7 ☐8 ☐9 ☐10

Please provide details to explain your response

In addition to explanations setting out the source of the respondent’s confidence level (which generally broke down evenly between ‘experience’ and ‘training’), a common theme emerged of respondents acknowledging that identifying abuse is complex even for experienced professionals, and that training should be provided for mandated reporters.

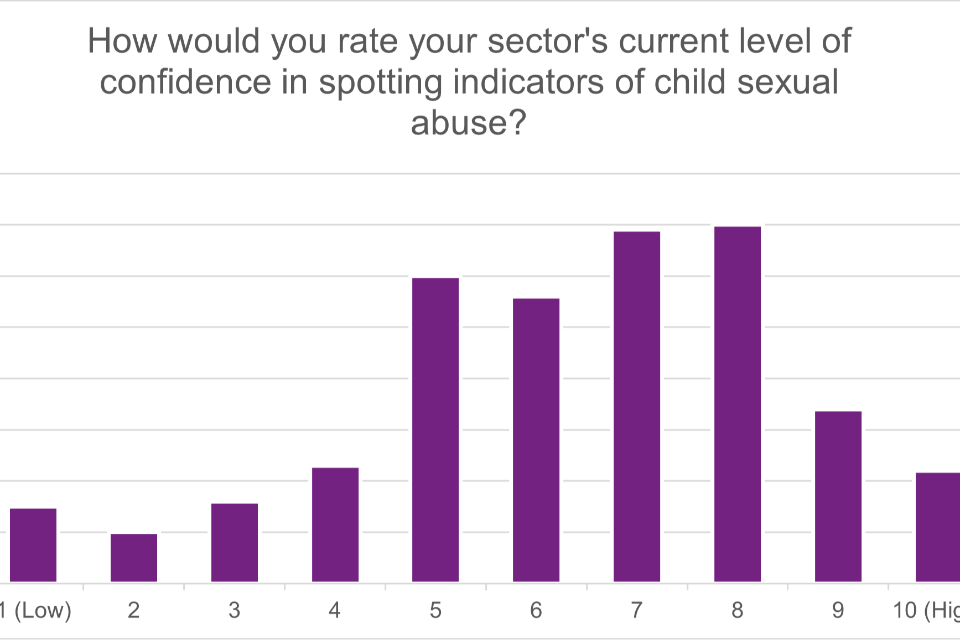

Q: How would you rate your sector’s current level of confidence in spotting indicators of child sexual abuse?

Indicate on a scale between 1-10 [1: low confidence, 10: fully confident]

☐1 ☐2 ☐3 ☐4 ☐ 5 ☐6 ☐7 ☐8 ☐9 ☐10

Please provide details to explain your response

Many respondents pointed out the variability in confidence they perceive to exist across their sector given the different degrees of proximity to children and access to training. High staff turnover was mentioned by several, as well as a general theme of reliance on accessing advice from more specialist colleagues when necessary.

The importance of multi-agency working and cross-pollination of effective reporting cultures or ideas were discussed by some respondents. In some cases, perceived confidence levels were explained as being influenced by a refusal or unwillingness to acknowledge ‘it could happen here’; as well as the fear of consequences in getting it wrong or prioritising reputations over good safeguarding practice.

As a highly complex and often stigmatised form of abuse, it was generally acknowledged that it would be very difficult for anyone to credibly claim complete confidence in spotting indicators.

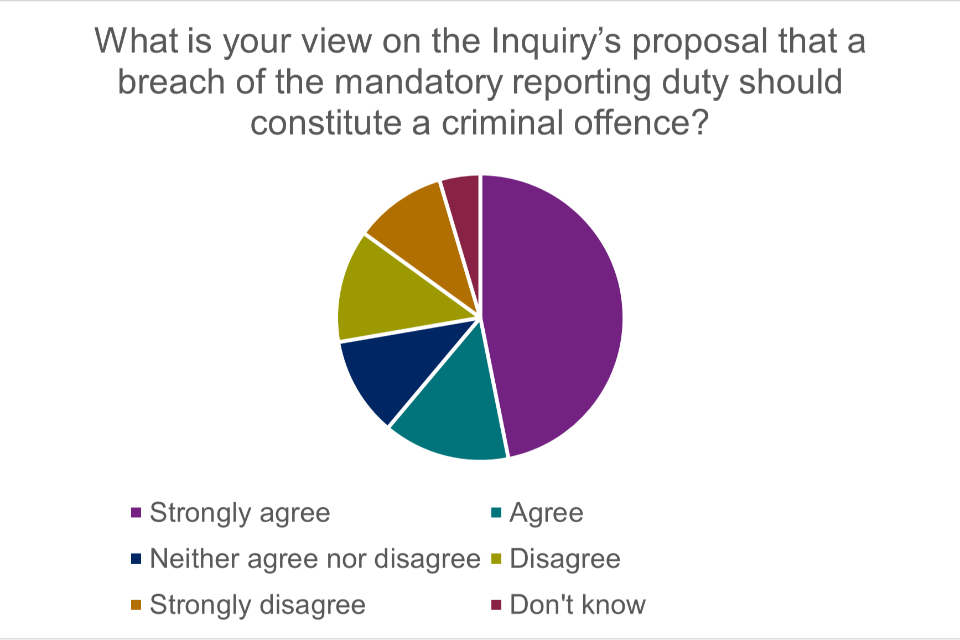

Q: What is your view on the Inquiry’s proposal that a breach of the mandatory reporting duty should constitute a criminal offence? (Select one)

☐ Strongly agree

☐ Agree

☐ Neither agree nor disagree

☐ Disagree

☐ Strongly disagree

☐ Don’t know

Please provide details to explain your response

Responses to this question were mixed, although a large proportion expressed agreement. The strongest theme emerging from responses which agree was the belief that the threat of a criminal offence would be needed in order for the duty to be successful.

Where respondents disagreed, many discussed the need to avoid a blanket approach to criminalising failures to report; arguing for example that failing to report should only be a criminal offence where disclosures have actively been covered up. These responses set out the view that individual failures to report due to a lack of skills or training, or as a result of genuine mistakes should not be criminalised. Concerns were also raised around the impact criminalisation will have on recruitment and retention in specific roles related to the safeguarding of children.

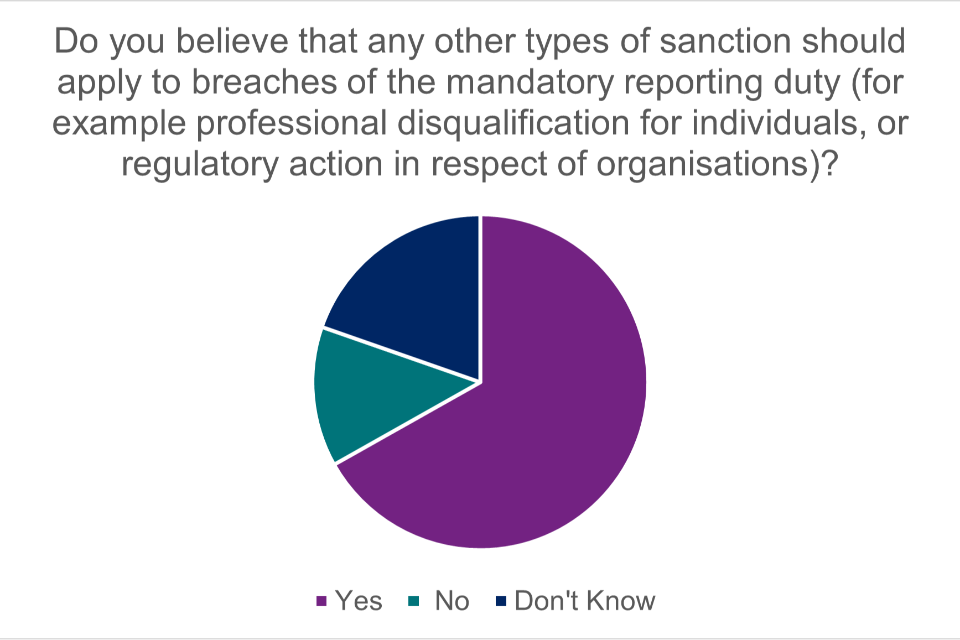

Q: Do you believe that any other types of sanction should apply to breaches of the mandatory reporting duty (for example professional disqualification for individuals, or regulatory action in respect of organisations)? (Select one)

☐ Yes

☐ No

☐ Don’t know

Please provide details to explain your response

Most respondents agreed that other types of sanction should be in place for failing to report cases of sexual abuse. Sanctions discussed by respondents range from disqualification, suspension and mandatory training for professionals, and regulatory action, fines and inspections for organisations. Respondents were divided as to whether they thought these sanctions should be in addition to, or instead of, criminal penalties.

Many respondents agreed that breaches of the duty will need to be considered on a case-by-case basis, with sanctions based on the context, severity and motivation behind the breach. Respondents favoured more severe sanctions in cases where there is evidence of a wilful failure to report or collusion to conceal abuse. Others are concerned about sanctioning individuals (particularly those in unregistered professions) who may not have the knowledge or confidence to report abuse or have not been properly supported by their organisation to do so. Where such issues were raised, almost all respondents agreed that appropriate training will need to be provided.

Some respondents said that anxiety over being prosecuted could lead to “overzealous reporting” by professionals. Others said that having no organisational sanctions could lead to the scapegoating of individual professionals and “witch hunts”.

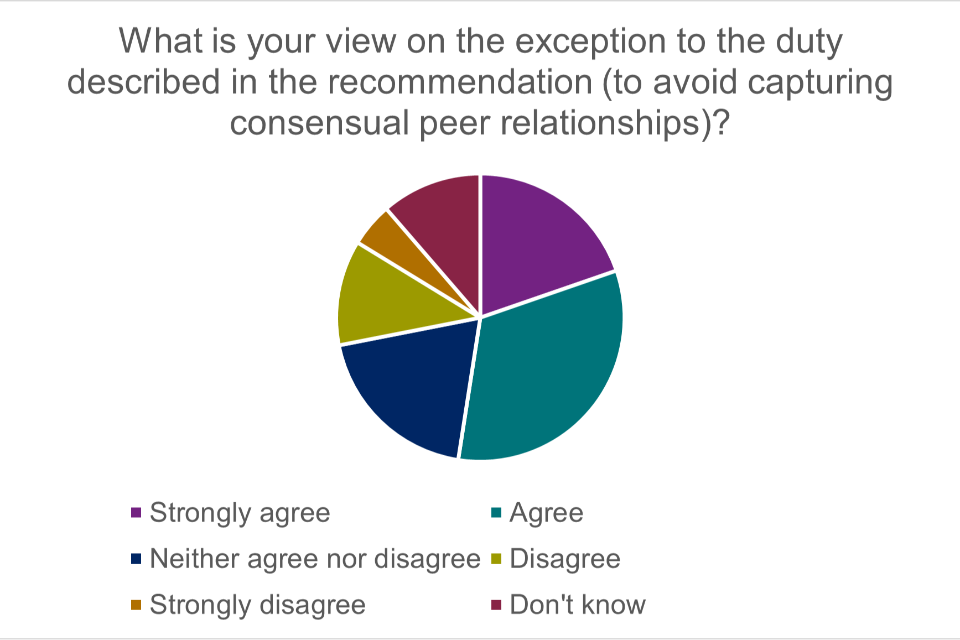

Q: What is your view on the exception to the duty described in the recommendation (to avoid capturing consensual peer relationships)?

The responses to this question were mixed, but indicated a general agreement with an exception designed to avoid capturing consensual relationships between young people.

Q: Is the exception (to avoid capturing consensual peer relationships) likely to cause any particular difficulties? (Select one)

☐ Yes

☐ No

☐ Don’t know

Please provide details to explain your response

Many respondents agreed that young people should not be criminalised for being in a consensual relationship. However, responses to this question also overwhelmingly recognised that defining ‘consensual’ relationships between peers will be complex and challenging for those tasked with reporting. These respondents argue that mandatory reporters may not be qualified to assess whether there is a “material difference” in the maturity and capacity of young people. Others reflected that even well-trained professionals may struggle to distinguish between consensual and coercive relationships, particularly if any of the children or young people are otherwise unknown to them. To overcome this, many respondents set out their view that clear guidance will need to be provided to ensure reporters understand the exemption and apply it appropriately.

Some respondents were concerned that the exemption could allow some inappropriate relationships to ‘fall through the cracks’ and create loopholes which could be exploited, including by gangs. It was also noted that relationships between teenagers can develop into a form of child sexual abuse through harmful sexual behaviour.

Other respondents were concerned that consensual relationships will inevitably be captured by the duty. They set out the view that the duty could lead to the inhibition of healthy sexual development, compromise relationships between young people and professionals in a position of trust, and deter young people from seeking sexual health advice.

Q: Do you think there should be any other exceptions to the duty which mean sanctions should not be applied? (Select one)

☐ Yes

☐ No

☐ Don’t know

Please provide details to explain your response

There was a mixed response to this question. While many respondents set out that no further exceptions should apply to the mandatory reporting duty, others advocated for exceptions for professionals acting in the best interest of the child or to allow consideration of the circumstances in which a disclosure was made. Another theme was the suggestion of the duty being disapplied where reporters believe a colleague or another relevant individual has already reported the disclosure.

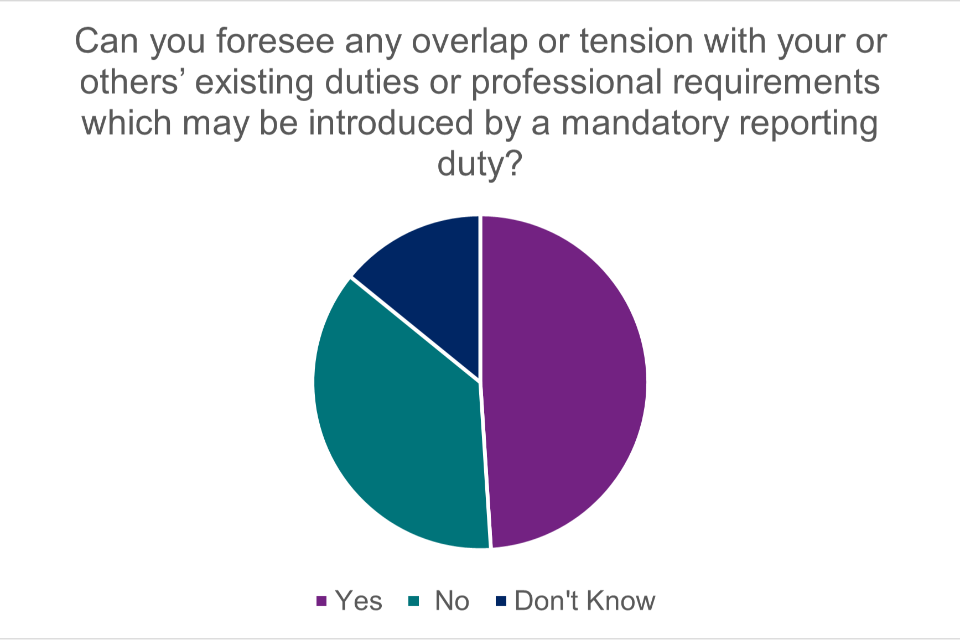

Q: Can you foresee any overlap or tension with your or others’ existing duties or professional requirements which may be introduced by a mandatory reporting duty? (Select one)

☐ Yes

☐ No

☐ Don’t know

Please provide details to explain your response

A strong theme emerged in responses to this question requesting clarity on how historical disclosures of abuse would be dealt with under the duty.

Several responses raised concerns over mandatory reporting either duplicating or superseding existing safeguarding duties. Questions were raised by others over whether the process-focused approach implied by a mandatory duty would undermine the child-focused approach of current safeguarding policies and practice.

Concerns were also raised as to how the duty might conflict with the reporter’s sense of agency. Such responses considered that certain professionals may no longer be able to rely on their own expertise and experience under the duty, and would be expected to report incidents against their professional judgement.

There was also concern around breaching duties of confidentiality to children and young people who may already be reluctant to engage with statutory services. The impact this could have on trusted relationships, and the likelihood of engagement with services in the future, were both raised by respondents as particular concerns.

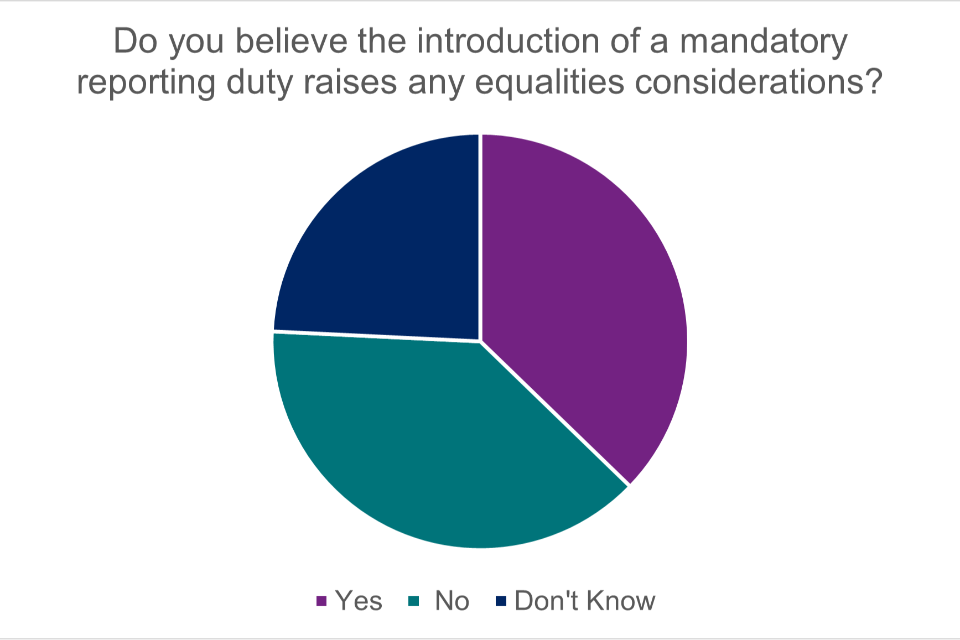

Q: Do you believe the introduction of a mandatory reporting duty raises any equalities considerations? For example, positive or negative impacts on groups with protected characteristics. (Select one)

☐ Yes

☐ No

☐ Don’t know

Please provide details to explain your response

Documented cases of bias and issues of discrimination were highlighted in response to this question, particularly linked to race, ethnicity, and experience of the care system. The ‘adultification’ of black children was raised as a specific equalities consideration. Respondents also expressed concern that children with special educational needs or disabilities, may be missed as potential victims of sexual abuse given that reporters can more easily miss non-verbal cues. A general perception of distrust in statutory services within marginalised communities was also flagged by some respondents.

Some respondents considered that before a mandatory reporting duty is implemented, inequalities within social systems need to be thoroughly considered and neutralised. Others expressed the view that for a duty to work, guidance and training on biases and discrimination, and how to tackle these issues, must be provided.

Other responses drew parallels to the mandatory duty to report female genital mutilation (FGM), referring to the challenges and opportunities experienced in implementation and suggesting that learning should be taken from this experience in delivering this policy.

A small number of respondents mentioned their view that human rights (specifically Article 9 of the European Convention on Human Rights: freedom of thought, conscience and religion) may be impacted given the interaction of a mandatory reporting duty with sacramental confession, and the potential unwillingness of individuals to participate in religious congregations if under a duty to report abuse they hear about or witness.

Q: What, if any, kind of protections do you think would need to be in place to ensure individuals making reports in good faith do not suffer personal detriment as a result?

Many respondents to this question agreed on the critical importance of ensuring reports made in good faith do not result in any detriment to the reporter. Common views expressed as to the nature of appropriate protections were whistleblowing laws, and the availability of full or conditional anonymity for reporters. Several respondents used this question to reiterate the importance of organisations providing sufficient support to reporters under their employ or care.

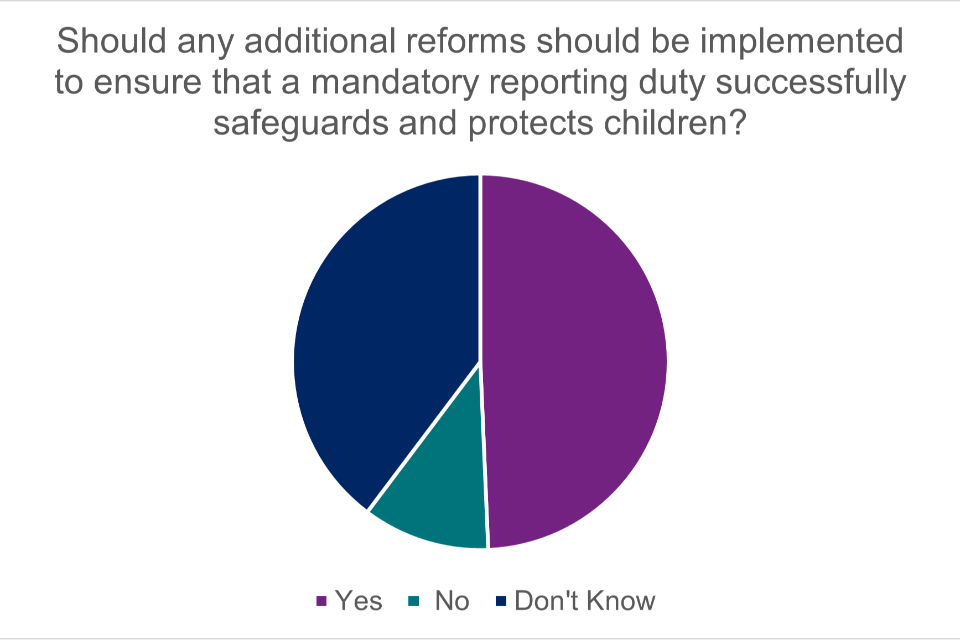

Q: Should any additional reforms should be implemented to ensure that a mandatory reporting duty successfully safeguards and protects children? (Select one)

☐ Yes

☐ No

☐ Don’t know

Please provide details to explain your response

Common suggestions made in response to this question were:

- Extending the availability and quality of therapeutic support for victims/survivors, their families and reporters themselves.

- The provision of a simple to use online portal and/or standardised reporting form.

- Piloting of the new duty before full implementation, and conducting a subsequent evaluation or review of its impact.

- Providing new or revised statutory guidance for mandated reporters. This should aim to give complete clarity on questions of exemptions and handling of historical allegations.

-