Call for evidence: Review of the personal insolvency framework

Updated 4 August 2023

Applies to England and Wales

1. Introduction

The purpose of this document is to seek evidence that will help inform the Government on whether the current personal insolvency framework is still fit for purpose and, if not, what reforms are needed.

The personal insolvency framework is an essential part of the economy. It has evolved over many years, providing established processes for debt relief for those unable to pay their debts either in part or in full, and a means to ensure, where possible, returns to creditors. As the agency responsible for developing policy relating to the insolvency legislative framework in England and Wales, the Insolvency Service is gathering evidence to help assess whether the personal insolvency framework continues to work effectively for creditors, consumers and traders in the 21st century.

This review comes at a pivotal time as the economy recovers from the impact of the pandemic and rapidly rising energy prices. In April 2022 the ONS published a report on the rising cost of living and its impact on individuals in Great Britain. 87% of adults reported an increase in their cost of living, and the main reasons given for this were the increases in the cost of food, gas and electricity bills and fuel prices. Whilst there have been annual fluctuations in household indebtedness, it has generally risen over the past 40 years growing from around 30% of GDP in 1982 to around 87% in 2021.

Since 2017 a Government priority has been to promote and ensure fair debt outcomes for all through the Government’s fairness agenda. The Government works in partnership with the free-to-consumer debt advice sector and this year has continued to maintain record levels of debt advice funding for the Money and Pensions Service, bringing their debt advice budget to £91.4 million.

In issuing this call for evidence, the Government would like to gather as much information as possible on the effectiveness of the personal insolvency framework, its overall purpose, whether the different procedures within the framework are still working satisfactorily and, if reforms are needed, what these should be.

The last major review of personal insolvency was carried out in 1982, some 40 years ago, by the “The Review Committee on Insolvency Law and Practice”, chaired by Sir Kenneth Cork and commonly referred to as the “Cork Committee”. The broad thrust of the Cork-inspired reforms was directed towards modernisation and liberalisation. This strategy was informed by the perception that incurring consumer debt, which was a relatively new phenomenon at the time, made a positive contribution to the economy and should be dealt with compassionately. Many of the recommendations of the Cork Report were developed into the Insolvency Act 1986. The Cork reforms included automatic discharge for people subject to bankruptcy after a set period and the introduction of Individual Voluntary Arrangements (IVAs), which at the time were primarily aimed at those in trade.

In the decades after the introduction of the Insolvency Act 1986, debt forgiveness and the need to reduce the social stigma attached to personal indebtedness became increasingly important. This influenced a number of further developments in insolvency law, including the introduction of Debt Relief Orders (DROs) in 2009. The creation of this new procedure followed a Government consultation in 2004 which identified that there were people in long-term debt difficulty who had no assets or disposable income to offer their creditors and for whom bankruptcy would be a disproportionate and costly route to debt relief.

Historically, personal insolvency was primarily for individuals running a business, but the framework now primarily serves consumer and household debt cases, with a large number of insolvencies initiated to provide debt relief to people with low incomes and few assets. This changing landscape presents the current challenge and need for reform.

In preparation for this call for evidence, the Insolvency Service has been greatly assisted by four academics known for their expertise in the insolvency field: Professor David Milman of the University of Lancaster, Dr Katharina Möser of the University of Birmingham, Dr Joseph Spooner of the London School of Economics and Dr John Tribe of the University of Liverpool. The Government also sought input from a wider group of stakeholders, including Government departments, creditor representatives, legal and insolvency professionals and debt advice providers. Four themes were agreed upon to structure the review, namely:

- the history and background to the framework,

- its underlying purpose,

- the procedures available within the framework, and

- fees and funding.

The academics each chaired a stakeholder group to consider these themes, hear different views and perspectives, and identify potential issues to be addressed. Their work forms a significant contribution to this call for evidence. We would like to extend our thanks to the academics and to the stakeholders for their invaluable expertise and input.

1.1. The scope of this call for evidence

The personal insolvency review will cover the framework within England and Wales only. Personal insolvency is a devolved function within Scotland and Northern Ireland.

Within that framework, this review is limited to consideration of bankruptcies, DROs and IVAs. It is recognised that the Debt Respite Scheme (which includes Breathing Space and the Statutory Debt Repayment Plan (SDRP) currently in development) forms part of the wider debt management framework. Breathing Space is not an insolvency procedure, although it will be considered insofar as it interacts with the framework. The SDRP is not an insolvency solution as debtors are required to pay the full amount of their debts, therefore any detailed consideration of SDRPs falls outside the scope of this review. The SDRP’s contribution to the framework will need to be taken into account in any future policy development. In addition, County Court Administration Orders and Debt Management Plans (DMPs) are not within the statutory personal insolvency regime and are not part of this review.

The Government would welcome responses from individuals (particularly those who are or have been subject to bankruptcy, a DRO or an IVA), creditors and their representatives, trade bodies, debt advisers and charities, insolvency office-holders, recognised professional bodies, academics, and any other interested parties. Any requests for further information should be sent to the email address below.

The call for evidence will be open for 16 weeks from 5 July 2022 until 24 October 2022. During this time, we intend to hold a number of meetings with key stakeholders.

We look forward to receiving your evidence and views.

Enquiries to:

Email: PIR.CFE@insolvency.gov.uk

2. Executive summary

Although in recent decades there have been amendments to the regime, including the introduction of Debt Relief Orders (DROs) in 2009, there has been no substantive review of the entire personal insolvency framework in 40 years. This was recognised by the Government in 2021 when announcing changes to the DRO monetary eligibility limits following a public consultation. The consultation attracted calls for a wider review of the personal insolvency framework and this call for evidence is launched in response. The Government believes that a review of the personal insolvency framework is needed to ensure it is flexible, proportionate and meets the needs of the modern economy.

The Insolvency Service is an Executive Agency of the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) and has policy responsibility, with BEIS, for the statutory personal insolvency framework in England and Wales. We are publishing this call for evidence to enable us to assess the effectiveness of the current framework, whether it achieves its objectives and whether its underlying purpose is the right one. We are also seeking views on the procedures available, their interaction with each other and any barriers to entry. In addition, we are seeking views on the funding of the personal insolvency framework, including fees charged, and who should bear the cost of that funding.

Chapter 4 of this call for evidence covers the history and background to the personal insolvency regime and how it has developed into the current framework.

Chapter 5 is split into three parts covering three main themes of the review:

- Chapter 5.1 covers the underlying purpose of the framework. It seeks views on what the objectives should be for a modern insolvency framework and where the balance should fall in providing debtors with a fresh start or ensuring returns to creditors.

- Chapter 5.2 covers fees and funding. This looks at the current arrangements of how insolvency solutions are paid for, as well as some of the wider consequential costs. It seeks views on whether the burden of costs is apportioned fairly.

- Chapter 5.3 covers the different procedures and how they are working. This sets out some of the underlying areas of concern and seeks evidence on what motivates debtors to seek one particular insolvency solution over another. It also asks whether the framework is sufficiently flexible and provides the right sort of insolvency solutions for current needs.

At this stage of the personal insolvency review, we wish to emphasise that no decision on reform of the framework has been made. This exercise is designed to gather evidence from those operating in the insolvency market, those who have been affected by insolvency and other interested parties. Your views and experiences will help us to evaluate whether the current system remains fit for purpose, whether there are opportunities for reform and if change is needed. Any proposals emerging from this exercise will be subject to further consultation.

3. How to respond

This call for evidence opened on 5 July 2022 and will close on 24 October 2022.

When replying, please state in which capacity you are responding, e.g. as an insolvency practitioner, a creditor affected by financial failure, an individual subject to an insolvency procedure, an individual considering entering an insolvency procedure or a debt adviser. If you are responding on behalf of an organisation, please make it clear who the organisation represents and, where applicable, indicate how the views of members were gathered.

When responding to the questions in this call for evidence please provide full explanations for your answer and include supporting evidence wherever possible.

Responses can be provided via Smart Survey by accessing the following link

https://www.smartsurvey.co.uk/s/RKMSB1/, or emailed to the Policy Team at the Insolvency Service at PIR.CFE@insolvency.gov.uk.

You can also send written responses to:

PIR Team, Policy Team

The Insolvency Service of England and Wales

Floor 16

1 Westfield Avenue,

Stratford, London

E20 1HZ

You may make printed copies of this document without seeking permission. Calls for evidence published by the Department for Business, Enterprise and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) are digital by default but, if required, printed copies of this document can be obtained from the address above or by telephoning 03003 048482.

3.1. Confidentiality and data protection

Information provided in this call for evidence, including personal information, may be subject to publication or release to other parties or to disclosure in accordance with the access to information regimes. These are primarily the Freedom of Information Act 2000 (FOIA), the Data Protection Act 2018 and the Environmental Information Regulations 2004.

If you want information that you provide, including personal data, to be treated as confidential, please be aware that under the FOIA there is a statutory Code of Practice with which public authorities must comply and which deals, amongst other things, with obligations of confidence.

It would be helpful if you could explain to us why you regard the information you have provided as confidential. If we receive a request for disclosure of the information, we will take full account of your explanation, but we cannot give an assurance that confidentiality can be maintained in all circumstances. An automatic confidentiality disclaimer generated by your IT system will not in itself be regarded as binding on the department.

We will summarise all responses and place this summary on GOV.UK. This summary will include a list of names or organisations that responded but not the names and addresses of individuals.

3.2. Quality assurance

This call for evidence has been carried out in accordance with the government’s consultation principles.

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/consultation-principles-guidance

If you have any complaints about this process (as opposed to comments about the issues which are the subject of the call for evidence) please address these to:

4. The personal insolvency framework

This chapter contains background information, for those not already familiar, on the development of the framework and how the different personal insolvency procedures work. It does not include any questions seeking views or evidence. For those working in the field of insolvency or already familiar with the framework, you may wish to go straight to chapter 5 of the document.

4.1. History and background to the framework

Bankruptcy was first developed as a commercial law remedy for creditors of insolvent businesses. It provided for the fair distribution of a business’s assets between its creditors and thereby sought to avoid a multitude of separate creditor claims and competing actions. Bankruptcy was extended to non-business debtors in 1861, but the process remained largely business-focused for a further century.

The Cork Report and the Insolvency Act 1986

The personal insolvency framework was comprehensively reviewed in the Cork Report of 1982 (Insolvency Law and Practice: Report of the Review Committee Cmnd 8558 (1982)). The Cork reforms were intended to modernise and liberalise insolvency law by reducing the stigma of bankruptcy and providing rehabilitation to debtors. At the time, the consumer credit market was relatively new, and therefore the Cork reforms were largely aimed at those insolvent individuals who traded. Many of the recommendations suggested by Cork were brought into force in the Insolvency Act 1986 (IA 1986) and its rules, which remains the primary piece of personal insolvency legislation for England and Wales.

The IA 1986 reforms covered the two main personal insolvency procedures: bankruptcy and the Individual Voluntary Arrangement (IVA). Bankruptcy was designed to be available to both creditors and debtors, in that it enables a debtor to deal with debts they cannot pay by allowing them to apply for their own bankruptcy, and a creditor to petition for a debtor to be made bankrupt. The bankruptcy process divides any assets (after fees and expenses) held by the debtor amongst those that are owed money and at the end of the discharge period the debts are written off, enabling the individual to make a fresh start free from debt.

The IVA, an agreement between the debtor and their creditors to repay a certain amount in each pound owed, was intended to be more debtor-friendly, though its aim was to produce better returns for creditors than those available through bankruptcy.

The IA 1986 introduced automatic discharge from bankruptcy after 3 years. Income payments orders (IPOs), whereby a person subject to bankruptcy pays a portion of their surplus income into their bankruptcy estate, were introduced as a method of increasing the assets available for creditors. The investigation of a bankrupt’s affairs and any potential criminal behaviour had long been a feature of the framework, and IA 1986 provided further criminal sanctions for people subject to bankruptcy. There was a summary administration regime introduced for small bankruptcies, using a lighter touch approach. However, this was abolished by the Enterprise Act 2002 in the light of a general liberalisation of bankruptcy, which at the same time saw the automatic discharge period for bankruptcy reduced from 3 years to 12 months.

Modifying the 1986 reforms

The first change to the 1986 model came with the enactment of section 3 and Schedule 3 of the Insolvency Act 2000, which removed the need for an “interim order” from court in every case as a prerequisite to accessing an IVA. This change helped to cut down the cost and delays in the IVA procedure. Since then, the use of IVAs has increased dramatically; in 2000 there were 7,979 recorded and by 2021 this figure had increased to 81,193.

The Enterprise Act 2002

Additional reforms were introduced by the Enterprise Act 2002, with its personal insolvency provisions coming into force in April 2004. These reforms were intended to further liberalise insolvency law and were influenced by the US approach to insolvency and the benefits to free enterprise of giving debtors “a fresh start”. However, by this stage most people subject to bankruptcy in the UK were consumer debtors rather than traders. Automatic discharge in bankruptcy was reduced to one year and a number of bankruptcy offences were repealed. The reforms also included greater protection against protracted realisation of a family home, setting a limit of 3 years for a trustee to deal with the interest of a person subject to bankruptcy.

To protect against abuse of these more liberal bankruptcy provisions, Bankruptcy Restrictions Orders (BROs) were introduced to extend the restrictions of bankruptcy beyond the date of discharge for those people subject to bankruptcy who had been dishonest or reckless.

Following the Enterprise Act 2002 reforms there was an increase in bankruptcy levels. In 2004 there were 35,898 bankruptcies recorded. By 2009, the year that Debt Relief Orders were introduced, this figure had increased to 74,670. At the time this rise in bankruptcy numbers was attributed by some to changes made by the Enterprise Act 2002. However, the available evidence does not support this, but rather suggests that it was a result of increased availability of credit and accompanying increases in household indebtedness.

The introduction of Debt Relief Orders

Both bankruptcy and IVAs had originally been designed with traders in mind but were not suitable options for those with low levels of assets and income from whom creditors could not expect a return. Debt Relief Orders (DROs) were introduced from April 2009 for those with relatively low levels of debt, few assets and minimal surplus income. Debt Relief Restrictions Orders (DRROs) were introduced alongside to play a similar role to BROs in controlling abuse. The enforcement regime, of which these sanctions are a part, is discussed further in Chapter 5.

The judicial role and reducing costs

Bringing proceedings in court can be an expensive and often cumbersome process. An initial reduction in the court’s role occurred with the decoupling of the interim order from the IVA in the Insolvency Act 2000. This was followed by the introduction of Income Payments Agreements (IPAs) for people subject to bankruptcy, Bankruptcy Restrictions Undertakings (BRUs) and Debt Relief Restrictions Undertakings (DRRUs), by all of which a legally binding agreement is reached with the debtor rather than imposed by court order.

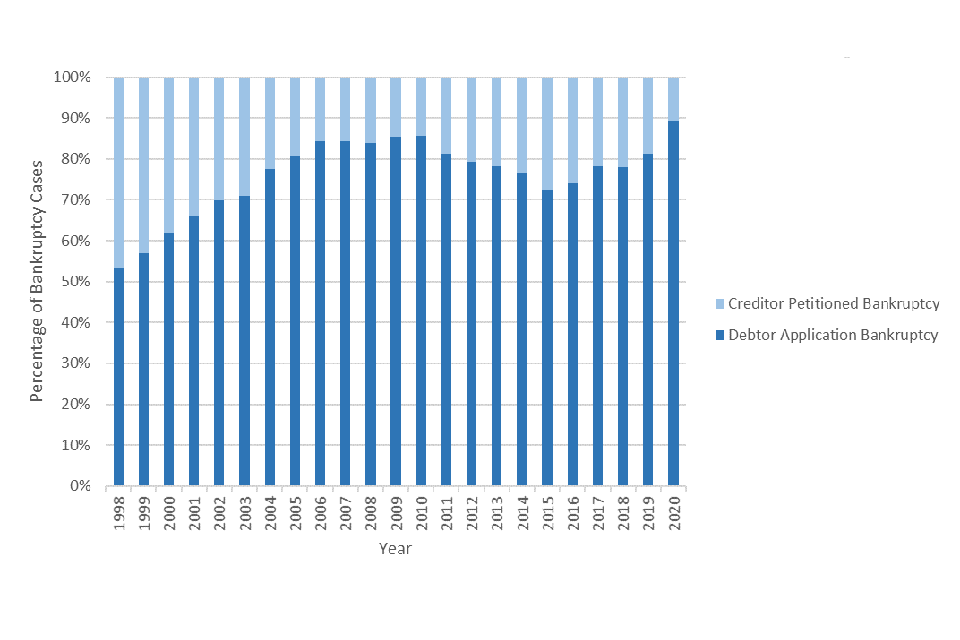

As most petitions for bankruptcy presented to court by debtors were uncontested, it was questioned whether the court needed to be involved at all. Since April 2016, debtor applications in bankruptcy have been handled by an Adjudicator using online procedures, removing the courts from the process. In 2021, 87% of the 8,715 bankruptcies in England and Wales were debtor applications.

The Debt Respite Scheme (Breathing Space)

Since May 2021, the personal insolvency framework has been supplemented by the Breathing Space Scheme. The purpose of a breathing space is to halt enforcement action from creditors by imposing a moratorium for 60 days. In the case of a mental health crisis breathing space, it halts action for as long as the debtor’s crisis treatment lasts, plus a further 30 days. The scheme freezes creditor enforcement action, most interest and other charges to provide a safe period for eligible individuals to seek professional debt advice and formulate a debt repayment plan or pursue other solutions.

Reflection on historical development

Over the past 40 years, the personal insolvency framework has undergone a series of changes, with new options being added as the need for alternative solutions to bankruptcy has emerged. There has been a fundamental shift in the circumstances of those seeking formal insolvency solutions, changes in the options available to them and the way those options are marketed and accessed.

4.2. The current framework

Bankruptcy

Bankruptcy is a remedy available to both debtors and creditors. It can also underpin other forms of insolvency as it may be used to recover funds, for example from directors of insolvent companies who are in breach of their duties and have a debt owing to the company. As mentioned above, bankruptcy was first conceived long before the substantial growth in consumer credit that has been a feature of the past few decades.

In order to apply for bankruptcy, a debtor must satisfy certain conditions and must show that they are unable to pay their debts. An online application is completed and delivered electronically to the Adjudicator, who decides whether to make the bankruptcy order. The debtor does not need to seek debt advice prior to making an application.

There are additional requirements if a creditor wishes to make a debtor bankrupt. Creditors must file a petition at court, which must show that a debt of at least £5,000 is owed and that the debtor has been unable to pay it within 21 days of an unsatisfied statutory demand or the execution of a County Court Judgment. The court decides whether to make a bankruptcy order.

If a bankruptcy order is made the Official Receiver is required to enter details of the bankruptcy on the individual insolvency register (IIR), which members of the public can search. The Official Receiver is appointed trustee of the debtor’s estate on the making of the bankruptcy order. Where the assets are complex to realise or where creditors so choose, an Insolvency Practitioner may be appointed trustee to replace the Official Receiver. If the debtor has surplus income after meeting normal living expenses, the trustee can apply for an Income Payments Order (IPO) or seek an Income Payments Agreement (IPA) (for the debtor to pay over a portion of their surplus income) for up to 3 years. The IPO or IPA can be updated if there is a change in income or expenditure and the amount payable reduced or increased accordingly.

In bankruptcy, the Official Receiver is under a general duty to investigate the conduct and affairs of each person subject to bankruptcy where it is deemed necessary, and this duty continues even where an Insolvency Practitioner is appointed trustee. Bankruptcy lasts 12 months, at the end of which the debtor is automatically discharged from their debts (subject to certain exceptions).

In 2021 there were 8,715 bankruptcy orders made in England and Wales, the lowest annual number since 1989. Of these, 7,610 (87%) were debtor applications and 1,105 (13%) creditor petitions. This was however an unusual year, the impact of the pandemic resulting in higher levels of creditor forbearance. For the 5 years before the pandemic in March 2020, bankruptcies had averaged just under 16,000 per annum, with debtor applications making up 77% and creditor petitions 23%.

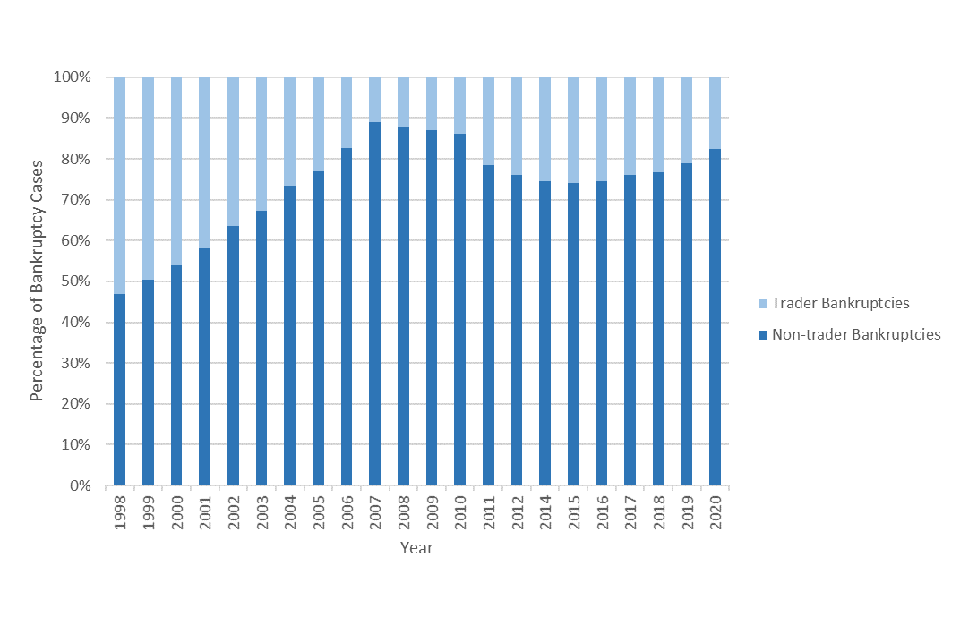

Data shows that in 2021, 16% of bankruptcies in England and Wales were traders (debtors who were either self-employed or ran an unincorporated business at the time of the order). This was a reduction from 18% of bankruptcies in 2020 (see Figure 2 at Chapter 5.3 below).

Debt Relief Orders (DROs)

DROs were introduced to deal with those cases where a debtor needs lasting debt relief but for whom bankruptcy would be disproportionate due to having few assets and little surplus income to pay to creditors. In order to apply for a DRO a debtor must meet monetary eligibility criteria regarding the level of debts owed, assets owned and surplus income.

A DRO application must be made by the debtor to the Official Receiver through an Approved Intermediary. The Official Receiver will either refuse the application or make a DRO. If an order is made, it must include a list of the debts, which the Official Receiver is satisfied are qualifying debts at the application date, specifying the amount of the debt at that time and the creditor to whom it was then owed. Upon making the order, the Official Receiver is required to enter details of the DRO on the IIR.

When a DRO is made the Official Receiver is not subject to a general duty to investigate where it is deemed necessary, as in bankruptcy. Instead, the legislation allows creditors with qualifying debts to raise objections against the making of the order or the inclusion of their debts. Such objections may prompt an investigation by the Official Receiver.

The Official Receiver has the power to revoke or amend a DRO under specified circumstances, for example where an increase in income or the acquisition of property exceeds the eligibility requirements.

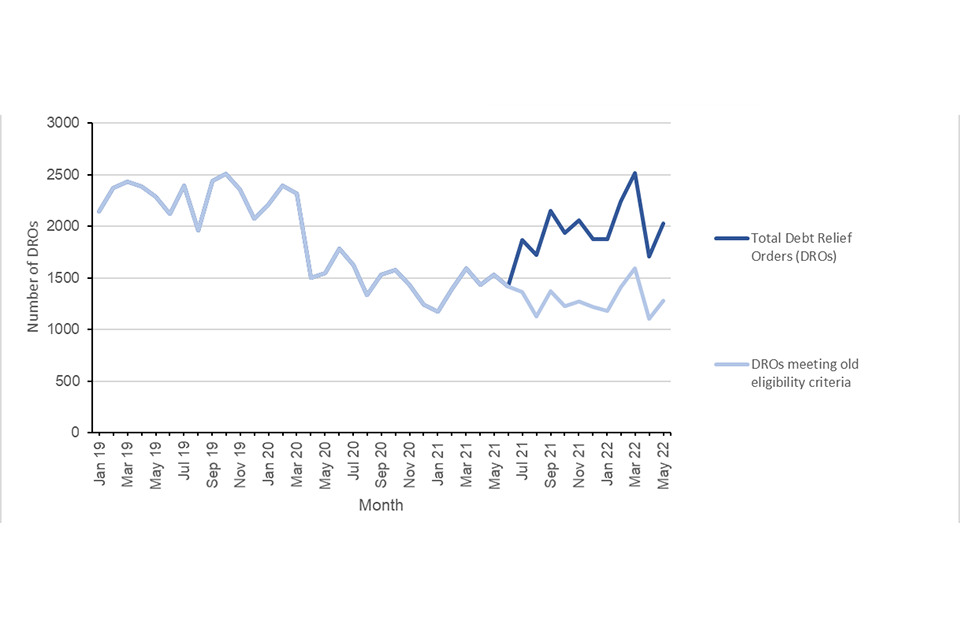

On 29 June 2021 the monetary eligibility limits for DROs were increased. A DRO may now be obtained where a debtor has debts of no more than £30,000, assets of no more than £2,000 (with an additional allowance where a vehicle is owned with a value of up to £2,000) and surplus income of £75 or less per month.

There were 20,135 DROs recorded in 2021 in England and Wales, which was lower than in 2020 (20,473). However, in the 11 months since the change in DRO eligibility criteria, an estimated 7,787 individuals have had a DRO approved who would not previously have been eligible. This means that (assuming no changes to application behaviour) the number of DROs is estimated to be approximately 55% higher than it would have been without the change to criteria. For the 5 years before the pandemic in March 2020, DROs had averaged just over 26,000 per annum.

Individual Voluntary Arrangements (IVAs)

As mentioned above, the IVA was created as an alternative to bankruptcy and its main application was originally expected to be for traders and professionals. An IVA is an agreement between the debtor and their creditors, whereby the debtor agrees to repay a proportion of monies owed to creditors, usually on a regular basis over a given period. This timetable of repayments is overseen by a private sector Insolvency Practitioner.

Most IVAs will be proposed for 5 or 6 years, which may include an extended payment arrangement instead of equity release from the family home. Any arrangement must be approved by at least 75% of creditors by value, and this approval binds all creditors who would have been entitled to vote. The Insolvency Practitioner has a duty to report the decision to the Insolvency Service. The Insolvency Service must then enter the details of the IVA onto the IIR.

The number of IVAs as a percentage of overall insolvencies has been increasing steadily over the past two decades. In 2002, bankruptcies were still considered the standard debt remedy at 79.42% with IVAs at 20.58%. By 2021 these numbers had shifted dramatically with IVAs making up 74% of all personal insolvencies (see Chapter 5.3). For the 5 years before the pandemic in March 2020, IVAs had averaged just under 60,000 per annum.

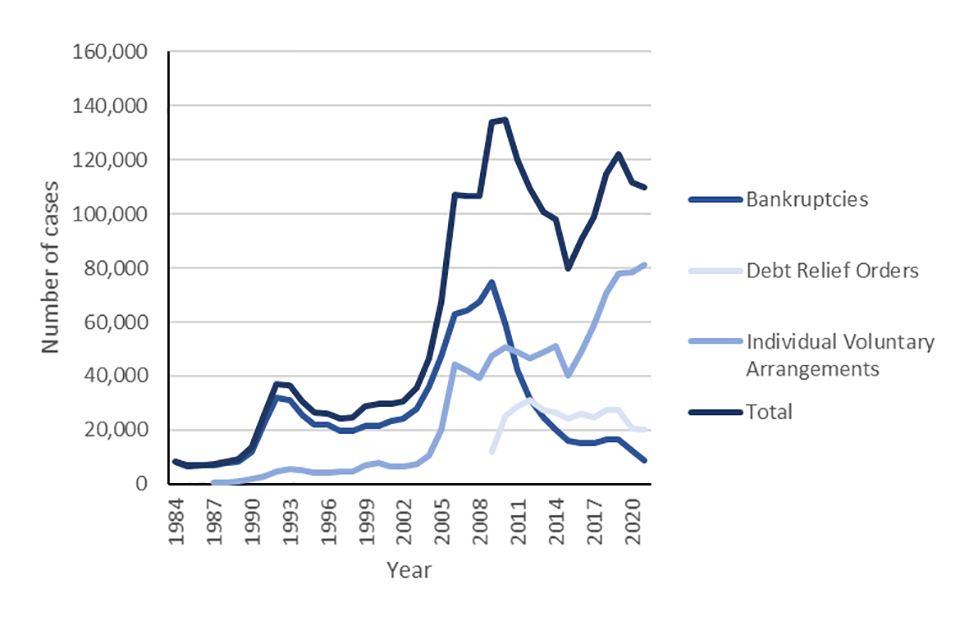

Figure 1 below summarises the number of insolvencies per year split between bankruptcy, DRO and IVA. This figure highlights the change over the years and the growth in IVAs compared to bankruptcy and DRO.

Figure 1: Number of bankruptcies, DROs and IVAs by year, England and Wales, 1984 - 2021

Number of bankruptcies, DROs and IVAs by year, England and Wales, 1984 - 2021

Source: The Insolvency Service, January to March 2022

Notes: Bankruptcies data for 1984-2021; Debt Relief Orders data for 2009-2021; Individual Voluntary Arrangements data for 1987-2021

Debt Respite Scheme (DRS)

There are two elements to the DRS: Breathing Space and the Statutory Debt Repayment Plan.

Breathing Space

The Breathing Space scheme is not an insolvency product but provides a period of protection against creditor enforcement action while a debtor seeks professional advice from a registered debt adviser with a view to dealing with their debts. There are two types: standard Breathing Space and mental health crisis Breathing Space. Individuals in a mental health crisis Breathing Space remain indefinitely in the scheme until their mental health crisis has improved.

As with DROs, the standard Breathing Space scheme relies on the involvement of private intermediaries. Eligible debtors must have their applications processed through a regulated debt advice provider, who can be any firm authorised by the FCA or a local authority. An application may not be made unless the provider has first advised the debtor.

Where a debt advice provider is satisfied that the application criteria have been met, they must confirm this to the Insolvency Service, who will then add an entry onto the Breathing Space register. Unlike the IIR, the Breathing Space register is not accessible to the public. Those entitled to the information contained on the register include the debtor, the debt advice provider, the Insolvency Service, and creditors owed debts that are included in the Breathing Space. Other debt advice providers also have access to information held on the register so that they can check whether any potential new client has been in a Breathing Space within the last 12 months. The Breathing Space moratorium begins one day after the registration.

The main difference between entry into a standard Breathing Space moratorium and entry into a mental health crisis moratorium is that, in the case of the latter, there is no prerequisite that the debtor has obtained advice from a debt advice provider. Whereas only a debtor can apply for a standard Breathing Space moratorium, prescribed persons as well as the debtor themselves can apply for a mental health crisis moratorium. Further, while a standard Breathing Space lasts 60 days, a mental health crisis moratorium ends 30 days after the debtor stops receiving mental health crisis treatment.

Since May 2021 there have been 69,613 Breathing Space registrations in England and Wales. Of these 68,490 were for a standard Breathing Space and 1,123 for a mental health Breathing Space.

Statutory Debt Repayment Plans (SDRP)

A Statutory Debt Repayment Plan (SDRP) scheme is currently in development and is anticipated to commence in 2024. On 17 May 2022 the Government launched a consultation on draft regulations to introduce the plan. The plan will enable an individual in problem debt to enter into a formal agreement with their creditors to repay their debts in full over a manageable period (in most cases, no more than 10 years), whilst receiving statutory protection from creditor action for the duration of their plan. Interest and penalties will not be charged by a creditor while an individual remains in the plan. The SDRP will be accessible only via professional, FCA-regulated debt advice providers, or through local authorities. An application may not be made unless the provider has first advised the debtor.

While debtors will make payments totalling 100% of the qualifying debts, it is envisaged that creditors will receive 90% with the remaining 10% being split between the debt advice provider (8%), payment distributor (1%) and scheme administrator (1%). Creditors must treat the 90% received as payment in full and will not be permitted to pursue the debtor to reclaim the 10% deducted to fund the plan. SDRPs will be listed on a private register that will be open to debtors, the creditors included in their plans and the debt advice providers.

Summary of the current framework

The table below compares the requirements, duration, impact and cost of bankruptcy, DROs, IVAs and SDRP.

| Procedure | Requirements to enter | Debt advice required? | Upfront cost to debtor/creditor | Debt write-off | Duration | Public/private register | Impact on debtor | Payments to creditors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bankruptcy | Debtor petition: - Unable to pay debts - Residency requirements Creditor petition: - Debt of £5,000 or more - Unsatisfied statutory demand or CCJ | NO | Debtor petition - £680 Creditor petition - £990 | YES | 12 months | Public | Restrictions on dealing with assets, including those acquired after the order is made.Stays on credit file for 6 years.Cannot obtain credit of £500 or more without disclosing the bankruptcy.Cannot trade without disclosing the name in which they were made bankrupt.Restrictions on holding certain occupations and offices. | YES – IPO/IPA for 3 years if sufficient surplus income. |

| DRO | - Debts £30,000 or less - Assets £2,000 or less- (plus £2,000 vehicle) - Surplus income £75 or less | YES -through Authorised intermediary | £90 | YES | 12 months | Public | Stays on credit file for 6 years.Cannot obtain credit of £500 or more without disclosing the DRO.Cannot trade without disclosing the name in which the DRO was made.Restrictions on holding certain occupations and offices. | NO |

| IVA | Approval by 75% of creditors by value | YES -through Insolvency Practitioner. | Overall fees vary – but around £ 4000 | YES | Average 5 to 6 years | Public | Restriction on dealing with assets that form part of IVA (family home).Stays on credit file for 6 years.Commonly IVAs include a clause that prevents debtor obtaining credit during IVA (otherwise seen as a breach of terms). | YES – usually proposed for 5 to 6 years. Average payment £130 a month. |

| SDRP (not currently operational) | - Debtor unable or likely to be unable to repay some or all of their qualifying debt as it falls due - Must have surplus income and be able to repay debts in a period not exceeding 10 years - Residency requirements - Approval by majority of creditors | YES – debt advice provider | No fee.Proportion of each payment made (10%) into a plan will fund costs. | NO | Up to 10 years when plan is proposed but this can be extended with creditor consent during the life of the plan. | Private | When obtaining additional credit must disclose that they are in a plan.Cannot obtain credit of more than £2,000 and can only obtain credit exceeding £500 if their debt advisor does not object.Impact on credit rating – unknown at present. | YES – the debtor repays 100% of the debt they owe via the plan. Creditors will be repaid 90% of their debt, which they must accept as payment in full. The remaining 10% of payments made will fund the costs of the scheme.Total surplus income as assessed using the Standard Financial Statement must be paid into the plan. |

5. Areas for consideration

5.1. The underlying purpose of the framework

The personal insolvency framework is intended to provide a robust regime which gives a fresh start to debtors and prevents future insolvency. It seeks to strike a balance between the interests of debtors and creditors and to ensure that those who can pay, will pay. These aims were explored by the Cork Report in 1982, with its recommendations on automatic discharge from bankruptcy and periodic payments to creditors from the proceeds of trading. They were expanded upon in the policy development leading up to the Enterprise Act 2002 (EA 2002), with its emphasis on encouraging entrepreneurs and combatting the stigma of financial failure.

The wider impact of personal insolvency

Both the Cork report and the reforms of EA 2002 were developed at a time when the provision of household credit was far lower than it is today and when its expansion was expected to lead to economic growth. Major economic policy institutions such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) now recognise that high levels of household debt can reduce or stifle economic growth, as households carrying heavy debt loads must reduce expenditure, lowering consumer spending and demand across the economy. In addition, debt is unevenly distributed, with lower income groups carrying relatively heavier debt burdens compared to wealthier groups. Middle and lower-income groups tend to spend most of their incomes, while the wealthy save and invest a greater proportion. The consequence is that over-indebtedness can deprive an economy of its chief spenders, as households who otherwise would spend most or all of their incomes must instead dedicate increasing portions of it to repaying historic debts. A robust and effective insolvency framework is therefore vital to ensure that people can return to financial viability and contribute to the economy.

The causes of insolvency

There can be many reasons for an individual not having enough money to pay their debts and which are not due to recklessness or mismanagement of finances. The Christians Against Poverty (CAP) Client Report 2022 identifies a number of primary reasons for their clients being unable to pay their debts, such as relationship breakdown, ill-health or loss of employment. Some may suffer from a mental health condition or from addiction. In some cases, debtors may have been using credit to supplement a low income or to cover unexpected expenditure such as the replacement of household appliances. Research by debt advice providers suggests that many debtors have unsustainable budgets and are unable to build up savings to mitigate against future financial shocks.

The ethos behind the framework

Historical views of bankruptcy as a commercial law remedy allowing creditors to share assets of a failed business have not entirely disappeared from the personal insolvency landscape. The current framework attempts to strike a balance, which has tilted in different directions at various points in history, between two aims which seemingly conflict with each other: the rehabilitation of debtors (the ”fresh start” ethos) and the maximisation of returns to creditors (the “can pay, will pay” ethos). This has led to complexity within the framework and, it may be argued, confusion as to its fundamental purpose.

A “fresh start” – debt relief

The concept of a fresh start has long been an objective of insolvency law, although definitions can vary. The OECD defines a fresh start as: “the exemption of future earnings from obligations to repay past debt due to liquidation bankruptcy”. This definition is given in relation to entrepreneurs’ prospects of starting new businesses, but freedom from existing debt is seen as an essential element. For consumer debtors, a fresh start may be defined more widely. CAP suggests social inclusion, better emotional wellbeing and an ability to move forward while financially healthy.

Once an individual has successfully completed an insolvency procedure, they are no longer liable for their qualifying debts. However, CAP research indicates that some individuals continue to face financial hardship due to unsustainable household budgets, the closure of bank accounts or lack of access to services due to their insolvency. In addition, certain debts are excluded (Section 281 IA 1986) such as Social Fund loans (Social Fund loans are not excluded in Scotland) and court fines. Other debts that are not cleared through the insolvency process include secured loans, student loans, maintenance payments and child support payments.

People subject to bankruptcy may also have to make payments to their creditors for a period of 3 years if they are assessed as having income beyond what is necessary for their reasonable domestic needs and those of their family (Sections 310 and 310A IA 1986). This 3-year period extends beyond the date of automatic discharge (one year). This demonstrates the conflict between the aims of debt collection and debt relief, with insolvency law attempting to strike a balance between the two.

A bankruptcy order, DRO or approved IVA is also entered onto a public register, the Individual Insolvency Register (IIR), and as such will be listed on the credit report of the debtor. Whilst the insolvency procedure is deleted from the IIR 3 months after it is concluded, it remains on the debtor’s credit report for up to 6 years. This may affect the debtor in a number of ways, such as the availability of credit and the interest rates charged, or potential barriers to certain professions.

The restrictions imposed by bankruptcy and DROs may also extend beyond the end of those procedures if a debtor is subject to a restrictions order or undertaking (see below).

The law does not seek to define a fresh start and there is little longitudinal research, such as empirical studies, on whether insolvency provides it.

“Can pay, will pay” – debt collection

The idea behind the “can pay, will pay” ethos is that the maximisation of returns to creditors will protect their position and allow them to lend more expansively and at lower cost as the risk of full default is minimised. However, this principle is reliant on the debtor holding assets or having surplus income which can be distributed to creditors.

In contrast, the purpose of DROs is to provide debt relief, with no prospect of creditors receiving any return. IVAs are intended to offer a better return for creditors than in bankruptcy, and usually provide for regular payments (albeit some small) to be made to creditors over a longer period, generally, than is the case with an IPO/IPA in bankruptcy.

Finding the right balance

The current personal insolvency framework must strike a delicate balance between the interests of the debtor, their creditors and the wider economy. Balance must be retained to ensure that a debtor’s contributions are not so high as to jeopardise the provision of debt relief and a debtor’s fresh start. At the same time, it must give creditors a fair return and ensure that the consequences of entering formal insolvency encourage responsible borrowing and management of personal finances.

There are also circumstances where significant contributions may be required, for example in creditor petition bankruptcies where there are high value assets at stake. In these cases, the balance tips more towards debt collection rather than debt relief.

Question 1: What should be the fundamental purpose of the personal insolvency framework? Does the current framework meet that purpose?

Question 2: If ‘fresh start’ and ‘can pay, will pay’ are the right objectives for the personal insolvency regime, does the current framework get the balance right?

Question 3: Please provide any evidence to show how well the objectives of ‘fresh start’ and ‘can pay, will pay’ are being met.

Question 4: Please explain whether there should be different objectives for different personal insolvency procedures.

Question 5: Please consider whether there should be different options for trading and consumer debtors. If so, how would the features differ?

Public confidence in the framework

In order for the framework to operate effectively, stakeholders must have confidence in the way it is delivered. This requires confidence in the professionals that provide insolvency solutions. Insolvency is a regulated profession, with Insolvency Practitioners being required to hold specialist qualifications and to follow legislative rules and procedures. They must also adhere to a Code of Ethics, along with Statements of Insolvency Practice (SIPs), which set out principles of required practice to maintain standards. These are updated regularly to ensure their fitness for purpose. Insolvency Practitioners are regulated by professional bodies, with the Insolvency Service acting on behalf of the Secretary of State as oversight regulator through its Insolvency Practitioner Regulation Section (IPRS). The Insolvency Service has recently consulted on changes to the regulatory framework.

In addition to the regulation and professional standards of the insolvency profession, public confidence requires transparency of process, safeguards to deal with and deter abuse and, for those who may be creditors, information to properly assess risk. The system of credit reporting covers many, but not all, of a debtor’s potential creditors, and can give creditors an indication of the level of risk posed by an individual debtor.

Restrictions placed on debtors

A number of automatic restrictions are placed on undischarged people subject to bankruptcy and debtors subject to DROs. These include restrictions on obtaining credit without disclosing their status, disqualification from certain professions and (for people subject to bankruptcy) loss of control of their assets (subject to certain exclusions). The period of bankruptcy may be extended indefinitely where a person subject to bankruptcy has failed to comply with their duties to the Official Receiver or trustee, for example where they have failed to provide information about their affairs. For debtors subject to a DRO, failure to comply with their legal duties may result in the DRO being revoked, and the debtor being liable for their debts once more.

The distinction between unfortunate and reckless debtors

Stakeholders must also have confidence in a debtor’s compliance with the duties and conditions placed upon them, and the overall effectiveness of the framework. Safeguards built into a personal insolvency regime to preserve its integrity should not unduly penalise honest but unfortunate debtors.

The concept of moral hazard is used to indicate the potential for individuals to increase their exposure to risks when they do not bear the burdens of those risks. Within personal insolvency this could be the risk that the availability of debt relief may lead to excessive or reckless borrowing by individuals and/or their early application for debt relief, rather than attempting to repay debt. A World Bank report suggested that “the most sensible response to moral hazard…is to design and implement proper access requirements—both for entry into the insolvency system and for receipt of a discharge or other relief—in order to isolate and exclude debtors who engage in excessively risky or other undesirable credit behavior”.

The insolvency framework in England and Wales contains a number of measures to police the system and address the issue of moral hazard. It differentiates between honest/unfortunate insolvents and dishonest/reckless insolvents through a range of criminal and civil sanctions.

Bankruptcy and Debt Relief Restrictions Orders

EA 2002 repealed some criminal sanctions, such as gambling and failing to maintain business records. Numerous criminal offences remain, including concealment of property or making false statements, but those repealed were replaced by the civil sanction of Bankruptcy Restrictions Orders (BROs) and later Debt Relief Restrictions Orders (DRROs). These provide for the restrictions of bankruptcy and DROs to be extended beyond discharge for a period of between 2 and 15 years where misconduct has occurred (a full list of the restrictions and other effects of a BRO/BRU or DRRO/DRRU may be found on the Insolvency Service website). Examples of misconduct that may result in a BRO or DRRO include disposal of assets, gambling, neglect of business affairs (for example failing to submit returns and pay over sums due to HMRC) or incurring credit with no reasonable expectation of repayment.

The Official Receiver investigates cases of potential misconduct and, where an allegation is made out and it is in the public interest to do so, may apply to court for a BRO or DRRO. Debtors who do not dispute the substance of the allegation may avoid court by agreeing to abide by the restrictions through a Bankruptcy Restrictions Undertaking (BRU). There are similar provisions for Debt Relief Restrictions Undertakings (DRRUs). In most cases, agreeing to an undertaking gives the debtor a modest reduction in the period of restriction, for example 6 months where the period is between 2 and 5 years, or 12 months for any period from 5 up to 15 years.

The BRO regime was intended to protect the public and to deter misconduct, with cases assessed on a balance of probabilities rather than the criminal standard of beyond reasonable doubt. A BRO or DRRO is not intended to punish the debtor; rather, it is intended to deter the debtor and the wider public from future misconduct, and to protect the public from harm.

Confidence in the effective enforcement of the insolvency regime is essential. Lenders must be able adequately to assess the risks of those to whom they extend credit. Potential customers of former insolvent traders must have confidence that the goods or services they contract for will be supplied. The current system provides for the publication of BRO/BRUs and DRRO/DRRUs on the IIR and the Insolvency Service regularly issues press releases covering the restrictions and prosecution cases concluded against debtors.

Misconduct in insolvency is rare. The draft regulatory impact assessment to the Enterprise Bill (that would later become the Enterprise Act 2002) anticipated that around 10% of bankruptcy cases would result in a BRO or BRU (Annex D of Insolvency: A Second Chance [2001] at para 5.5). However, the rate of cases in which misconduct has been identified and action taken against the debtor has not reached this level. In the five years to 2021/22, the number of cases resulting in a BRO was around 3% of the total number of bankruptcies. In 2021/22 there were 314 Restrictions Orders and Undertakings relating to Bankruptcies and Debt Relief Orders in England and Wales. The most common allegation type in 2021/22 was ‘Incurring debt without reasonable expectation of payment’, making up one fifth of allegations. The average length of restrictions was 5 years and 2 months.

Criminal sanctions

In addition to general offences (for example under the Fraud Act 2006) there are offences specific to those subject to bankruptcy or DROs (Sections 353-360 and 251O-251T IA 1986, respectively). Examples can be failure to disclose property, or breach of the restrictions on obtaining credit or acting as a director. Criminal penalties can range from fines to terms of imprisonment of up to 7 years. Breach of a BRO or DRRO is also a criminal offence and may be grounds for a further period of restriction in the higher bracket.

Question 6: How effective are the current safeguards (public records, public registers, restrictions and sanctions on debtors) at protecting the integrity of the personal insolvency framework?

Question 7: To what extent does the current enforcement regime (BROs/DRROs and criminal sanctions) adequately achieve the aims of deterring future misconduct (both individual and general) and protecting the public?

Question 8: How, if at all, should the personal insolvency framework distinguish between honest/unfortunate and dishonest/reckless debtors?

The international perspective

A European Commission discussion paper from 2016 stated that a well-functioning insolvency framework should ensure that debt is serviced where possible and, where that it is not possible, that it is written off. The paper suggested that any personal insolvency mechanism should be affordable, should encourage timely and definitive resolution, and should:

- Offer the genuine possibility of an effective fresh start

- Encourage settlements with creditors

- Offer affordable solutions to debtors

- Avoid disincentive effects for income generation; for example, repayment plans should be based on pre-defined payments rather than on the concept of “excess income”

- Offer full debt discharge after a limited period

The OECD’s 2018 report Design of Insolvency Regimes Across Countries considered effective insolvency regimes. The report concentrates on business rather than consumer debtors, but some general themes were covered which are evident in many jurisdictions as follows:

- An effective insolvency framework should provide that debt is serviced where possible and where that is not possible, it is written off

- A “fresh start” encourages enterprise

- Debt counselling can help debtors to learn lessons and prevent future insolvency

- Honest/unfortunate insolvents should not be treated the same as dishonest/reckless insolvents

Study of other jurisdictions shows that attitudes towards insolvency and the options available can vary. Research from the US and Australia documents the persistence of bankruptcy stigma and negative public attitudes towards those who default on their debts (Michael D Sousa, “The Persistence of Bankruptcy Stigma” (2018) 26 American Bankruptcy Institute Law Review 217). For the purposes of this call for evidence, we have considered the regimes in Australia, Canada, Ireland, Scotland, Singapore and the USA.

The duration of bankruptcy varies from around 4 months in the USA to 5-7 years in Singapore (for a person subject to bankruptcy for the first time). Canada has varying discharge periods depending on whether a debtor has surplus income to pay to creditors and whether they have previously been bankrupt. Scotland has introduced similar provisions to those in England and Wales, in that it provides for discharge from bankruptcy to be granted automatically, but for the restrictions of bankruptcy to continue (through the use of BROs/BRUs). Some jurisdictions have bankruptcy offences for misconduct similar to that which is dealt with by BROs/BRUs and DRROs/DRRUs in England and Wales. Other jurisdictions (Australia, Ireland) provide for discharge to be suspended in cases of misconduct, in some cases indefinitely (Canada, Singapore).

Studies from the UK and USA suggest that debtors retain a keen ambition of repaying debt and “doing the right thing”. One US study found that debtors would go without food or healthcare rather than file for bankruptcy (Polletta, F. and Tufail, Z. “The Moral Obligations of Some Debts” (2014) Sociological Forum 1). Evidence from Citizens Advice in the UK shows similar sacrifices by debtors attempting to avoid formal insolvency. For some jurisdictions (Canada, Ireland, Scotland, USA), debt counselling is mandatory. This may be prior to entering an insolvency procedure (Ireland, Scotland) or a requirement to receive discharge (Canada, USA).

Where an individual is bankrupt, some jurisdictions require a portion of surplus income to be paid over to their creditors (Australia, Canada, Ireland, Scotland). Ireland assesses a debtor’s income against Reasonable Living Expenses (RLEs) which allow for a “reasonable” standard of living, rather than subsistence living, and which includes modest savings.

Question 9: Are there any features of other regimes that would be beneficial to consider for England and Wales and how effective are these features? For example, debt counselling and rehabilitation programmes.

5.2 Fees, funding and costs

This section of the call for evidence considers the funding of the personal insolvency framework in England and Wales, including the fees and costs to both debtors and creditors. It poses several questions to help determine where the costs of insolvency fall and whether the balance is fair or whether there needs to be changes to rebalance the impact of costs and who should pay them.

The costs of personal insolvency, including provision of debt advice, consist of public and private sector costs and are borne by debtors, creditors and the taxpayer. Where an insolvency procedure is initiated by a debtor, the debtor pays at least some of the cost to enter that procedure, although in some cases this payment may be deferred, for which they will gain the benefits of debt relief. In contrast, in most cases, creditors do not receive full payment of their debts and therefore bear most of the cost burden of insolvency.

Current position

The current funding framework has evolved over time, and each of the statutory procedures has its own arrangements. The framework is designed to recover the administrative costs of the Insolvency Service and the courts, provide for payment of Insolvency Practitioner fees where appointed, and make a contribution to the funding of Competent Authorities for the work undertaken by Approved Intermediaries in DRO cases.

There are 4 potential areas of financial cost in personal insolvency:

- Debt advice

- Court proceedings fees as part of the insolvency framework administration (e.g. creditor bankruptcy petition fees)

- Insolvency Service fees and costs incurred in performing statutory functions as part of the insolvency framework administration (e.g. fees paid to the Official Receiver or Adjudicator, IVA registration fees and the costs incurred when dealing with assets)

- Insolvency Practitioner fees and costs in bankruptcy and IVA cases, including legal costs and costs incurred when dealing with assets.

Debt Advice

The availability of debt advice is important to help debtors identify and access the best debt solution for their circumstances. The wrong solution may prolong a person’s indebtedness unnecessarily without a corresponding benefit to creditors.

Funding for debt advice comes from several sources, including government, local authorities, charities, a levy raised by the FCA on lending institutions and what is known as Fair Share, whereby some creditors make a voluntary contribution to a regulated debt management organisation in respect of the arrangement of a debt management plan. Paid-for debt advice is also available.

The Money and Pensions Service (MaPS), an arms-length body sponsored by the Department for Work and Pensions, has a statutory duty which it does through commissioning free-to-customer debt advice services. The Government is continuing to maintain record levels of debt advice funding for MaPS, bringing their debt advice budget to £91.4 million this financial year.

The current regime requires an element of debt advice to be provided to debtors entering an IVA by the Insolvency Practitioner who is the prospective nominee (although the scope of that advice may be limited, see Chapter 5.3). It should, however, enable the debtor to make an informed choice that an IVA is a suitable solution. Debtors entering a DRO receive some debt advice from the Approved Intermediary. There is no requirement to seek debt advice when applying for bankruptcy, although some debtors do so.

A report from the then Money Advice Service suggested that helping people solve their debt issues reduced the cost of creditor recovery and administrative costs. The report estimated that creditors received an additional 5% through lower recovery costs when debt advice was provided to debtors, which resulted in a reduction of creditor recovery costs of £135-237m per year.

Court proceedings fees

A court fee must be paid by creditors wishing to petition for the bankruptcy of a debtor, in addition to the cost of the petition fee (see Table A below). Court fees go towards funding the running of the court system and its associated staff. Responsibility for the setting of court fees lies with HM Courts and Tribunals Service. Debtor application bankruptcy cases and DROs do not require an application to be made to court, and therefore debtors are not subject to these fees.

Court fees have increased over time, most recently in September 2021 (The Court Fees (Miscellaneous Amendments) Order 2021) and for creditor petition bankruptcy fees are currently as follows:

Table A: Creditor Fees Table from 2005 – Bankruptcy

| Year | Court Petition Fee (£) |

|---|---|

| Sept 2021 | 302 |

| 2014 – 2021 | 280 |

| 2011 – 2014 | 220 |

| 2005 – 2011 | 190 |

Insolvency Service fees and costs

Bankruptcy

The bankruptcy procedure can involve extensive work for the Official Receiver in administering the insolvent estate. A fee has been charged by the Official Receiver for this purpose since the office of Official Receiver was first introduced in 1883. The underlying fee structure has been amended over the years and was last updated in 2016 (The Insolvency Proceedings (Fees) Order 2016 (legislation.gov.uk)). The impact assessment accompanying the 2016 Fees Order explained that the changes in that order were designed to minimise the then disproportionate cross-subsidy from asset-rich cases to asset-poor cases (in some cases up to £80,000) and to provide a more transparent way to recover the necessary planned and managed cross-subsidy. In addition, the changes were designed to ensure that the fees complied with the principles of Managing Public Money i.e. on a full cost recovery basis.

Debtor application bankruptcy

When a debtor applies for bankruptcy, they must pay an application fee and a deposit to cover the initial costs of the Official Receiver. The debtor may pay the fees in instalments, but the application cannot be submitted until all fees are paid in full.

The deposit goes towards paying the Official Receiver’s administration fee, which is currently £1,990 per case. The remaining balance is found from realising assets in the insolvent’s estate. As most insolvent individuals have no or very few assets, a general fee of £6,000 is charged to all bankruptcy estates. This acts as a cross subsidy to cover the fees not recovered in cases with insufficient assets. If there are enough assets to cover all of the fees and costs, then the deposit is returned to the person who initiated the insolvency. Where the Official Receiver remains trustee in bankruptcy, a 15% fee is charged on net realised income from all assets. This fee covers the cost of realising the debtor’s assets and making distributions to creditors in the order of priority set out in legislation.

Creditor petition bankruptcy

A creditor who wishes to make someone bankrupt has to petition the court, pay a court fee (see table A above) and pay a deposit towards the Official Receiver’s administration fee, which in creditor petition cases is currently £2,775 per case

In addition to the court fee and petition deposit, most creditors will engage a solicitor (or use an in-house lawyer) to present the petition to the court, incurring additional costs by doing so. It is evident that the overall costs for a creditor are significant, and that bankruptcy is not, nor is it designed to be, a debt collection remedy to be used lightly.

Recovery of costs of the Insolvency Service in bankruptcy cases

As stated above, the Insolvency Service charges fees to recover the costs of administering insolvency processes, which are set at a level that is designed to cover the full cost of the service provided across the mix of cases handled by the Official Receiver, both those with assets and those without. The law provides for the recovery of unpaid Insolvency Service fees before any distribution is made to creditors, but where there are insufficient assets to cover costs, a deficit will be incurred on such cases.

The fee structure is designed with an element of managed cross-subsidy, where higher asset cases pay a higher amount to cover the costs of administering lower or nil asset cases. There is currently a deficit incurred in approximately two thirds of debtor petition cases and more than half of creditor petition cases.

Debt Relief Orders

A DRO application is made to the Official Receiver through an Approved Intermediary who is authorised by a Competent Authority. The fee for a DRO is £90. Where a debtor is unable to pay the fee in full it may be paid in instalments, but the application cannot be submitted until the full fee is paid. £10 of the fee is given to the Competent Authorities. The application fee of £90 (minus the £10 fee to the Competent Authority) is retained by the Official Receiver whether the DRO is made or not, and there are no further fees charged.

Insolvency Practitioner fees

Insolvency Practitioners’ fees are generally approved by creditors and can be charged on the following basis:

- time and rate i.e., a charge-out rate is agreed for different grades of staff working on a case and charged accordingly based on time spent

- a percentage rate applied to either or both the assets realised and amounts distributed to creditors

- a fixed fee, either for specific elements of work undertaken or the whole case.

- a mixture of the above

Fees can also be charged as a percentage rate applied to either or both the assets realised and amounts distributed to creditors

Insolvency regulators have a statutory regulatory objective to ensure that those they regulate provide quality services at a fair and reasonable cost.

Insolvency Practitioner fees - Individual Voluntary Arrangements

The structure and scale of Insolvency Practitioner fees vary substantially. IVA fees are agreed with debtors and creditors at the start of the process and are recovered from the contributions made by a debtor over the period of the IVA, as described below.

IVA fees are comprised mainly of nominee and supervisor fees. Nominee fees cover the preparation of the proposal, for example the income and expenditure assessment and obtaining the approval of creditors. Supervisor fees fund the management of the IVA. Nominee fees can range from £1000-£2000. This can be paid upfront, or with the first monthly payments (typically five) into the IVA.

Early termination of an IVA may occur because an individual can no longer meet the agreed terms of the IVA either due to a change in circumstance or because the IVA was unaffordable. Where early termination of an IVA occurs in the first or second year of the IVA, a significant part of a debtor’s payments will usually have gone towards paying for the fees of the IVA rather than their creditors. For IVAs registered in 2019, there was a two-year termination rate of 12%, which was the lowest since 2014.

Insolvency Practitioner fees - Bankruptcy

Where an Insolvency Practitioner is appointed trustee in bankruptcy in succession to the Official Receiver, there will be charges for the Insolvency Practitioner’s work in addition to the fees charged by the Official Receiver for the initial administration of the case. The charge will vary depending on the value of assets to be dealt with, how difficult the assets are to realise and the complexity of the case generally.

Where assets are costly to realise (e.g. legal action to recover a debt) and there are insufficient other assets in the estate, the trustee may seek funds or indemnities from creditors in order to pursue the matter. Insolvency law provides that the remuneration of the trustee (whether the Official Receiver or an Insolvency Practitioner) is generally recovered from assets ahead of any distribution made to creditors.

Question 10: Who should bear the costs of entering and administering personal insolvency procedures?

Question 11: How should the costs of entering and administering personal insolvency procedures be paid and structured between the different parties?

Question 12: What options are available to debtors and creditors who are unable to afford the cost of bankruptcy, IVA or a DRO?

Consequential costs of insolvency procedures

In addition to the direct financial costs of personal insolvency there are other costs that arise as a consequence of the procedures themselves, some of which impact adversely on the debtor.

Restrictions imposed by insolvency procedures.

Debtors subject to bankruptcy, an IVA or a DRO all have their name and address and other personal details recorded on the Individual Insolvency Register, which can be searched online. The register is also available to Credit Reference Agencies who use the data as part of their reports.

Bankruptcy and DROs impose legal restrictions on debtors as set out at Chapter 5.1 above. An IVA proposal will also impose requirements on a debtor which may be burdensome, for example, requiring the permission of the supervisor to obtain credit.

Loss of access to products or services

Some debtors may lose access to products and services due to insolvency clauses in the contracts for provisions of those product and services or the impact insolvency has on their credit rating. Debt advice providers report that cars bought on hire purchase agreements and rental tenancies can be at risk, but the most common problem encountered in this area is the closure of bank accounts. Debt advice providers report that this can happen in up to 50% of cases where there is no debt owed to the bank, and that this presents uncertainty for the debtor over whether the bank will choose to close their account.

In 2019 Christians against Poverty found that, of the 9 high street banks that offer basic bank accounts, 4 will not provide one in the first 12 months of a formal insolvency to undischarged people subject to bankruptcy. This may require the opening of a new account and can cause a great deal of anxiety. In some cases, it can take clients several months to open a new bank account.

The record of an insolvency remains on the debtor’s credit report for 6 years, and this may prevent access to cheaper utility tariffs or certain payment methods. For instance, some debtors may lose the option to pay their car insurance in monthly instalments or be unable to obtain a mobile phone contract. It may make it more difficult for someone to get a mortgage or a loan and where one is obtained the interest rates may be considerably higher than for those with no record of insolvency.

Lack of a savings buffer

The Standard Financial Statement that is used to assess essential household expenses and an income contribution towards payment of debts makes provision for a modest savings allowance of £25 per month. However, this level is often insufficient to build up a buffer to pay for emergency and other unforeseen expenses such as repairs to household appliances or a car to get to and from work. Consequently, there is a risk that people will obtain emergency credit at high rates of interest to pay for such expenses and fall into another cycle of over indebtedness.

Stigma of insolvency

Research by R3 in 2015 found that whilst approximately 50% of adults believe that the social stigma of insolvency was less than it was a decade ago, almost half (48%) believe that there is still a stigma associated with insolvency. The October 2015 report stated that the main causes of stigma are the publication of the insolvency, problems in obtaining a bank account, the fact that creditors went unpaid and the effect on the debtor’s credit rating.

Wider economic costs of insolvency

The damage of debt for individual households extends beyond mere financial hardship to include negative impact on economic opportunities, family relationships, health, and children’s well-being and development. It is widely recognised that over-indebtedness results in significant social costs, which are borne by wider society.

Question 13: What are the main consequential costs of the different insolvency procedures?

Question 14: How can we reduce the stigma of insolvency to both encourage early action by those in financial difficulty and to support a ‘fresh start’ from debt relief?

Question 15: Please provide any evidence to show whether consequential costs serve a useful purpose or whether they produce unintended consequences for different stakeholder groups.

5.3. The current insolvency procedures and how they are working

As stated in the Introduction, this review covers bankruptcy, DROs and IVAs and this section will discuss how these procedures are operating.

How are the insolvency procedures being used today?

Bankruptcy

As can be seen in Figure 1 at Chapter 4 above, until 2010 bankruptcy was the main insolvency remedy, with the number of bankruptcies rising significantly from 2002. Along with a rise in bankruptcy numbers, there was an increase in the use of bankruptcy by consumers, rather than traders. While in 1998 non-traders represented 47% of total bankruptcies in England & Wales, by 2007 this had increased to 89% as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Percentage of trader and non-trader bankruptcies, England & Wales, 1998-2020

Percentage of trader and non-trader bankruptcies, England & Wales, 1998-2020

Source: The Insolvency Service, Individual Insolvency Statistics: October to December 2021

In addition to the rise in consumer bankruptcies, the percentage of debtor petitions (and later applications) increased (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Percentage of debtor application and creditor petitioned bankruptcies, England & Wales, 1998 – 2020

Percentage of debtor application and creditor petitioned bankruptcies, England & Wales, 1998 – 2020

Source: The Insolvency Service, Individual Insolvency Statistics: October to December 2021

Since 2009, bankruptcy numbers have fallen dramatically and IVAs are now the primary insolvency debt relief remedy for both consumer and trader debtors. The rapid fall in bankruptcy numbers may be explained by various factors: these could include the cost to debtors and creditors (which is discussed in chapter 5.2), and the introduction of the DRO procedure, including the recent extension of the eligibility requirements. In addition, an increasing number of debtors are choosing IVAs rather than bankruptcy. Factors which may influence a debtor’s choice of procedure are discussed in more detail below. There has been some analysis of the motivation of consumer debtors (Möser, Making Sense of the Numbers: The Shift from Non‐Consensual to Consensual Debt Relief and the Construction of the Consumer Debtor’ (46) 2019 Journal of Law and Society 244), but little analysis of the motivations of trading debtors and creditors.

The number of bankruptcies has recently fallen to an historic low, although this needs to be seen in the context of the impact of the pandemic, which saw greater creditor forbearance across the economy. The current increases in the cost of living may see numbers rise again.

IVAs

IVAs are the most common personal insolvency procedure being used today. The rapid rise in IVAs after 2003 is usually explained by the change in market practices for this option. IVAs were originally aimed at traders, company directors and high-income professionals, but have developed into a broad-based remedy for consumer debtors (Walters, Individual Voluntary Arrangements: A ‘Fresh Start’ for Salaried Consumer Debtors in England and Wales? (2009) 18 International Insolvency Rev. 5). As a consequence, we can now distinguish between “Consumer IVAs”, which make up the majority of arrangements, and a smaller number of “Trader” or “Bespoke” IVAs, which are discussed in more detail below.

To assess the effectiveness of IVAs, it is helpful to consider the interests of debtors, creditors and the wider public interest.

As stated above, upfront costs can be lower for IVAs, although the debtor may pay a significant amount over the course of the arrangement. DROs and bankruptcy usually provide the debtor with a higher level of debt relief; debtors are not required to make any payments to creditors in a DRO. They offer a discharge after just one year (although bankruptcy can require payments to creditors for up to 3 years), while IVAs require debtors to complete a repayment plan that, in most cases, lasts for 5 years or more.

With this in mind, it is perhaps surprising that IVAs are the most popular insolvency procedure. Some stakeholders and academics have raised concerns over the level and quality of information given to debtors, particularly regarding transparency around costs and the suitability of other solutions, ahead of entering an IVA. The FCA highlighted its own concerns in a recent consultation on debt packager referral fees. Debt packagers are authorised, commercial firms that provide debt advice solutions, but do not provide debt solutions themselves. The business model relies on generating income from referral fees by passing customers onto certain debt solution providers.

In addition, it has been suggested that IVA users may be prone to over-optimism as to their ability to fulfil these agreements and may not take into account the long-term implications of the restrictive budgets they have calculated. It is also well documented that debtors want to “do the right thing” and make payment to their creditors. Debtors may also focus on immediate considerations rather than longer-term gains. They may choose an IVA because the upfront costs may be lower than those of bankruptcy and DROs, or because of the perceived stigma of other insolvency solutions. They may also be persuaded to choose an IVA because of high profile marketing of these as a debt solution.

What individuals consider as the best option often includes considerations beyond financial ones, such as mental health and the need for privacy. These considerations have recently been discussed in a report by the Insolvency Practitioners Association, which sets out a number of reasons why an individual may choose an IVA over other available personal insolvency solutions, including:

- Inability to afford the fee for bankruptcy (even where there was the option to pay in instalments)

- Impact on property (the family home)

- Moral obligation to repay creditors as much as possible

- Too drastic

- Stigma

- Concerns re impact on future employment

- Concerns re current employment

- Concerns re impact on motor vehicle(s)

- Concerns re impact on property rental

- Previous bankruptcy

There may be other reasons not included in the list above: for example, an individual may opt for an IVA over bankruptcy to avoid the investigation of the Official Receiver and the scrutiny and asset recovery powers of the Trustee in Bankruptcy.

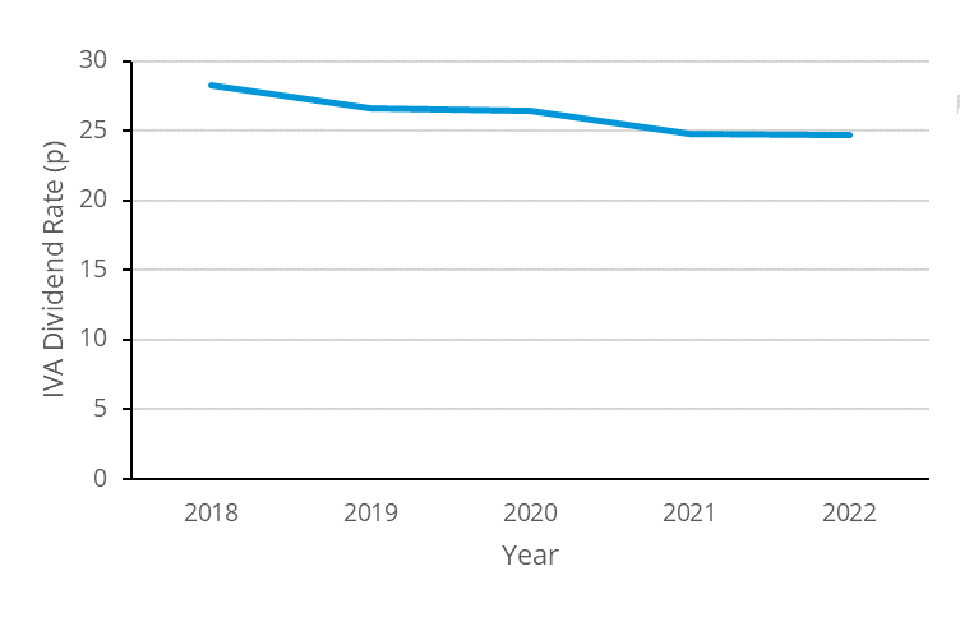

IVAs should generally deliver a better result for creditors than bankruptcy, so it is unsurprising that creditors prefer IVAs as an insolvency procedure. Data provided by TDX in Figure 4 below indicates that returns to creditors in 2021 were on average 24%, although this has declined from previous years.

Figure 4: Average dividend rate in IVAs 2018 to 2022

Average dividend rate in IVAs 2018 to 2022

Source: TDX Group

DROs: