DFID Research: Getting children into school and breaking the cycle of disadvantage

DFID-funded research helps generate new knowledge to improve access to primary and secondary education for disadvantaged children in poor countries

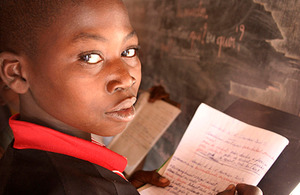

Young girl in school classroom. Picture by Simon Davis/DFID

Education is a key policy priority and DFID supports research that changes the way we think about how to deliver education in the developing world. We want to understand the broader factors that both help and hinder ordinary people’s access to school and learning. DFID research generates new knowledge that assists governments in poor countries to improve both the quality of education they provide, and its outcomes.

September 2011 saw the launch of DFID’s Girls Education Challenge Fund (GEC) - a new initiative aimed at helping NGOs, charities and the private sector to find better ways of getting girls into primary and lower secondary education in the poorest countries in Africa and Asia. Billed as “Educating 1 million girls to tackle poverty” the GEC initiative significantly raises the profile of educational access within the UK government’s development portfolio.

The social and economic benefits of educating girls are profound and well recognised. An increase of just 1% in the number of girls attending secondary education boosts annual per capita income by 0.3% while additional schooling directly leads to improved levels of health and family planning. Promoting gender equality and empowering women is an essential route to poverty alleviation: it is a process that begins with education.

DFID action on universal access

The Girls Educational Challenge Fund will be a competitive process that encourages organisations to set up a range of projects targeting marginalised girls of primary and lower secondary age. Non-governmental organisations - including businesses and charities - are being asked to put forward ideas to get girls into good quality education.

There will be a focus on working with new organisations and partners to try fresh approaches where traditional ones have not been successful. The British Government will then back the best of these. In order to receive continued funding, the organisations have to demonstrate measurable improvements in the quality of education and increased numbers of girls going to school.

Innovative projects could be funded in any of the 27 countries in which DFID operates. It is likely that some of the activities that are supported will ensure that facilities at schools - for example separate latrines and “safe spaces” for girls - are provided. The types of initiative sought are those that provide support to girls and young women such as scholarships that not only pay for school fees but ensure girls are able to buy their own uniform, travel safely to school and support them to find work once they leave school. Pilot projects and strategic partnerships will also be encouraged alongside the smaller “step change” projects funded through the GEC.

The need for evidence-based intervention

Over 67 million children are estimated to be out of primary school across the world. Women and girls are the most marginalised and often face the biggest obstacles when it comes to accessing education. In the poorest countries, families that face severe financial constraints often find it is a challenge to send their children to school, and it is girls that are the most likely to be pulled out of education first. Those girls that do make it to school often have a lower completion rate with many having to drop out due to lack of school fees.

In addition to gender inequality and the influence of traditional values, other supply side realities like long distances to school, inadequate provision, and poor quality educational programmes complete a vicious circle that bars many from decent schooling. Poverty remains a key catalyst for exclusion with cost and affordability being significant disincentives to enrolment and regular attendance. Research by Addressing the Balance of Burden in HIV/AIDS (ABBA)found that in Swaziland (and South Africa as whole) 11% of primary, and 30% of secondary school children report missing a month or more of schooling each year.

Studies by the Consortium for Research on Educational Access Transitions and Equity (CREATE) also show that over the last 10 years, the problem of late enrolment in Ghana appears to have become worse rather than better, and in 2005/6 nearly half of all Grade 1 children were over-age by two or more years.

CREATE’s work in Ghana, India, Bangladesh, South Africa, and the UK has led to recommendations on how to improve access to education, including by giving school councils and governance structures a say on the issue of children’s rights; making school opening hours flexible; abolishing corporal punishment; and training teachers about child-centered teaching methods and inclusion. This type of evidence-based approach plays a vital role in informing the policy process and ensuring that interventions are appropriate and effective.

Beyond enrolment

The Girls Education Challenge (GEC) initiative is one example of DFID’s continued commitment to making a difference across the 3 interrelated areas of access, outcomes and quality in education where interventions will have the greatest impact.

However, when we talk about “getting children into school” it is not simply a case of enrolling large numbers into primary and secondary education. Following enrolment it is easy for children to join the ranks of the “silently excluded” - those who are enrolled but not learning. Increasing enrolment and the quality of provision, therefore, have to be achieved hand-in-hand. Recognising the urgent need for educational interventions beyond enrolment is a welcome change in thinking and one that helps redefine the position of education in relation to wider poverty alleviation strategies. Getting kids into school is about increasing life chances and helping break the cycle of disadvantage.

Research has generated vital insight into the repercussions of persistent poor quality provision in education. Policy recommendations by CREATE promote a view of educational access as far more than a child’s enrolled presence. They argue it has to include judgements of educational quality and outcomes (what competencies and capabilities are acquired through learning). Without this emphasis on quality of provision, many vulnerable children will remain both excluded from school and silently excluded within schools, learning little while they are there.

Increasing project scale

Projects that deliver measurable improvements in the quality of education and increased numbers of girls going to school need to be scaled up and supported. However, the process of scaling up, or “orchestrated replication”, is no simple feat. Whilst it is critically important to replicate cost-effective, high impact projects that deliver results quickly, studies have shed light on specific contexts that can stand in the way of the process.

Implementing Quality Education in Low Income Countries (EdQual) is a DFID-funded programme doing research in sub-Saharan Africa where some of the lowest enrolment ratios and achievement rates are to be found. EdQual worked closely with teachers to develop strategies that work locally. The programme found that good quality education depends on the interaction between policy, the school and the home and community environment.

A recent working paper published by EdQual warns that “enlarging scale” can “undermine or destroy promising reforms rather than spread them” if projects are not rooted in levels of local demand, participation and design. EdQual’s research underscores the importance of having a charismatic and effective local leadership dedicated to scaling up backed by strong local demand, and adequate funding (not necessarily high level).

However, the report notes that communities and local organisations can also be obstacles to change and should not be romanticised as the “magic formula” for scaling up initiatives. Local participation and ownership of education projects differs hugely from place to place, with educational reform being a very slow process in some localities and regions.

The programme found that local educational initiatives can often deliver higher levels of quality and uptake than those planned by central authorities. The report states that “some of the programmes widely regarded as effective education reforms and successful scaling up began outside the national formal education system”. Examples cited are the Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee, Lok Jumbish (India) and Escuela Nueva (Colombia) - projects founded to address gaps in state provision. However diligent centrally planned reforms may be, ultimately it is communities themselves who will be the long-term arbiters of change.

Managing participation by local communities is essential for delivering best practice, appropriate interventions, and ensuring sustainability. DFID research enables initiatives like the GEC to respond appropriately to local needs, and ensures that UK aid delivers maximum value for money and long-term impact.

Transforming the trends that produce cycles of deprivation

The Research Consortium on Educational Outcomes and Poverty (RECOUP) - a consortium led by the University of Cambridge with core funding from DFID - conducted a 5-year research programme into the trends that drive cycles of deprivation. This research identified the need for policies that ensure educational outcomes benefit the disadvantaged. RECOUP findings have raised awareness of the links between patterns of schooling and gender inequality.

A RECOUP policy briefing on gender inequality highlighted the issue of poor quality schooling reinforcing gender patterns within societies. Findings suggest that girls who attend schools that reinforce gender stereotypes are less ambitious and less successful in the kinds of jobs that they go on to do. Equally, schools reinforce male superiority through greater investment in male schooling and failure to act against male harassment of girls.

The key to change, it is suggested, may lie in supporting communities to become socially transformative with respect to education and gender relations over the long-term. Creating an environment where equality as a guiding principle is fundamental to improving girls’ educational chances and outcomes. The Women’s Empowerment in Muslim Contexts (WEMC) programme is an example of how converting the way people think about education - especially for girls - increases women’s capabilities to challenge the kinds of power relations that underpin inequality.

Conclusion

Improving access to education is not simply a matter of expanding enrolment in schools. Problems of irregular attendance, poor progress, exclusion and dropouts in schools across low and middle-income countries continue.

New thinking on education and development reveals the need for a revolution in access, outcomes and quality if future generations are to realise their full potential. Initiatives like the GEC place girls at the heart of DFID’s education work, helping to remove barriers from the start.

Education is not just about getting kids into school. It’s about making sure they are well taught, and that what they learn in different education settings improves their lives and economic opportunities in the long-term.

Related Links

Distance Education Technologies: An Asian perspective

Young Lives Working Paper 69. Eliminating Inter-Ethnic Inequalities? Assessing Impacts of Education Policies on Ethnic Minority Children in Vietnam

Equality and Education in Peruvian schools

Building relationships to leverage change: Young Lives and Ethiopia’s Ministry of Education

RECOUP Working Paper No. 41. The RECOUP Household Surveys: Methods, implementation and some results