Review of the oil and gas fiscal regime: call for evidence

Updated 4 December 2014

0.1 Ministerial foreword

The government recognises the considerable contribution that the UK oil and gas sector makes to the UK economy. Even as we move towards a less carbon-intensive future, oil and gas are set to remain a vital part of our energy system for years to come. The sector also has an important role to play in driving jobs and growth across the UK, and is a rich source of skills, expertise and technology.

It is therefore important that we do all we can to maximise the economic recovery of our indigenous hydrocarbon reserves, and the government remains firmly committed to encouraging investment and innovation in the UK Continental Shelf, whilst ensuring a fair return for the nation.

2014 marks 50 years since the first licensing round in the UK Continental Shelf. And we have 40 years or more of resource extraction ahead of us. But as the basin matures, the oil and gas remaining is becoming increasingly difficult and more expensive to extract. Opportunities are often smaller, technically challenging or both. As the nature of the opportunities has changed, so has commercial activity become more varied, with around 125 groups of companies now involved as licensees in offshore exploration and production, showing much more diversity than in earlier decades.

As we move into the second half of the basin’s lifetime, this government has been taking action to safeguard its future. We commissioned Sir Ian Wood to review how to maximise the economic recovery of oil and gas from the UK Continental Shelf, and are implementing his recommendations including by establishing a new regulator, the Oil and Gas Authority, which we are aiming to set up in shadow form in autumn 2014. And in the tax system we have expanded allowances and introduced certainty over decommissioning costs in order to support investment, examples of how the broad shoulders of the UK are able to maximise the benefits oil and gas can bring to the economy.

As the revised regulatory arrangements take shape over the coming year, it is right that we consider the long-term shape of the fiscal regime to ensure that tax and regulation work together to support economic recovery as the basin matures. That is why the Chancellor announced at Budget 2014 that the government would conduct a review of the fiscal regime.

This will be a wide-ranging review of all key elements of the regime. Our aim is to set a direction of travel for the long term that helps cement stability and certainty. We will publish interim conclusions at Autumn Statement.

Action by government must be matched by action by industry. The answers to many of the challenges of a mature basin must come from companies operating in the UK and on the UK Continental Shelf and in the supply chain, for example from greater cooperation, more effective use of assets, more efficient production and cost-effective decommissioning. Fiscal reform will at best be part of the answer.

The views of industry will be vital to the review. This call for evidence invites comments and evidence to help ensure we reach the right conclusions. I look forward to working with interested stakeholders as we explore the long-term future of the oil and gas fiscal regime.

Rt Hon Nicky Morgan MP, Financial Secretary to the Treasury

1. Introduction

1.1 Background

The UK has been a major producer of oil and gas since the 1970s. The UK government’s objectives for managing the UK’s oil and gas reserves are twofold:

- to maximise the economic recovery of hydrocarbon resources [footnote 1]

- to obtain a fair share of the net income from those resources for the nation, primarily through taxation

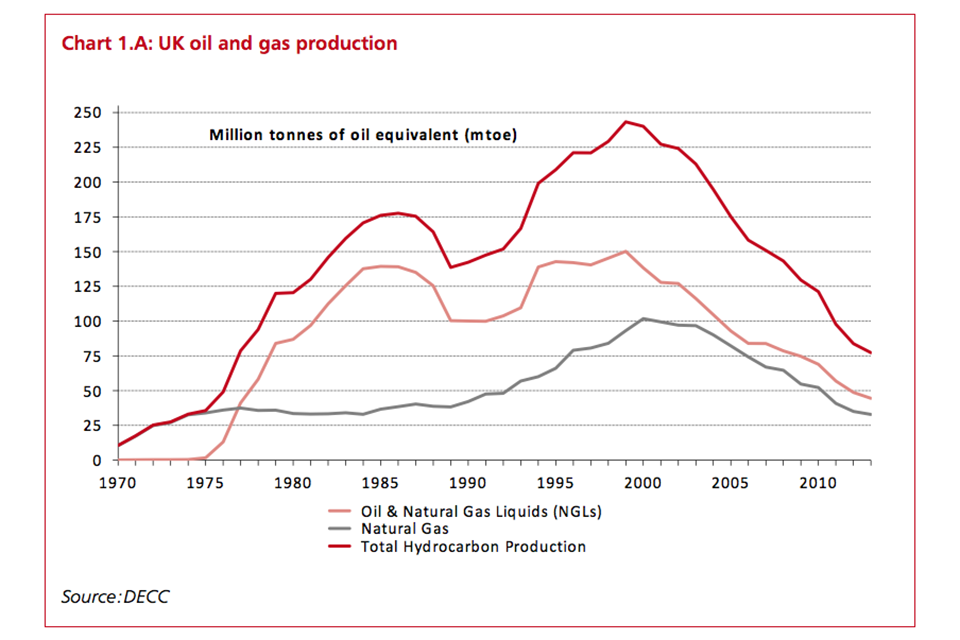

Since the late 1960s, production in the UK and UK Continental Shelf (UKCS) has totalled around 42 billion barrels of oil equivalent (boe) (see Chart 1.A). There are some 300 offshore fields in production [footnote 2] and the sector:

- still provides nearly 40% of the UK’s primary energy needs [footnote 3]

- directly and indirectly supports around 450,000 jobs across the UK [footnote 4]

- paid £4.7 billion in upstream taxation in 2013/14 [footnote 5]

Chart 1.A: UK oil and gas production

Chart 1.A: UK oil and gas production

The government estimates that there are between 11 and 21 billion boe remaining in the UKCS that could be economic to recover. [footnote 6] This is a significant resource, and has the potential to support employment, skills, economic growth and tax revenues for several decades to come. A record £14.4 billion was invested in the UKCS in 2013, demonstrating confidence that this potential can be realised. [footnote 7]

However, as the basin matures recovering the remaining oil and gas is becoming more difficult. In recent years, the UK oil and gas industry has faced a growing challenge to maintain production – which has fallen 37% since 2010 [footnote 8] – and production efficiency [footnote 9] – which is down to near 60%, having averaged around 80% a decade ago. [footnote 10] A number of factors are contributing to these outcomes, including:

- new fields are generally smaller, harder to find and more technically challenging to exploit. This means that the potential benefits from exploration are less attractive. Exploration rates have been relatively low since 2009

- extending the production of old fields often entails making significant investment in existing infrastructure to extend their lives. This is also an issue for many new small fields, which require access to existing infrastructure if they are to be economic to develop

At the same time, the UKCS has to compete for global investment capital. Numerous less mature basins overseas offer commercial opportunities, such as Norway, West Africa and North America.

In light of these challenges, the government has been taking action in support of the objective to maximise economic recovery:

- to ensure regulation of the UKCS is encouraging companies to improve asset stewardship and collaborate effectively on new developments, the government commissioned Sir Ian Wood to review how to maximise the economic recovery of oil and gas from the UK Continental Shelf. The government is working to implement his recommendations including by establishing a new regulator, the Oil and Gas Authority, to be set up in shadow form in autumn 2014 [footnote 11]

- joint government-industry PILOT programme is, amongst other things, identifying ways to remove barriers to exploration and development

- to ensure that uncertainty over tax relief does not create a barrier to asset trades between companies and new investment, the government has introduced Decommissioning Relief Deeds, now signed by 61 companies

- to enable development of resources that are economic but commercially marginal the government has doubled the value of the small field allowance, introduced a £500m allowance for large shallow-water gas fields, a £3bn allowance to support investment in large and deep fields, an allowance for incremental investment in older fields, a new allowance for onshore oil and gas projects, and has announced a new cluster area allowance for ultra high-pressure, high-temperature projects, on which a consultation will be published later this month

Following the completion of the Wood Review and whilst the Oil and Gas Authority is being established, the government is taking the opportunity to review the long-term future of the fiscal regime to ensure that the tax and regulatory systems work together to support maximising economic recovery as the basin matures.

1.2 Objectives and scope

The government’s objective in undertaking this review is to ensure that the UK’s tax treatment of the UKCS continues to support maximising economic recovery as the basin matures. The government will publish an initial report alongside Autumn Statement 2014 which will:

- assess the competitiveness of the regime and the case for reform

- identify how the tax regime can best work alongside the new approach to regulation [footnote 12] recommended in the Wood Review to help maximise economic recovery

- set out how the regime can provide stability and certainty for the long term, and propose a timeframe or roadmap for making any changes

- identify whether fiscal support in the form of allowances is being targeted effectively, and options for reform (options would be subject to further work and consultation to a longer timeframe)

In the period to Autumn Statement the review will comprise a strategic look at the future shape of the fiscal regime in its totality, including Petroleum Revenue Tax, Ring Fence Corporation tax, Supplementary Charge, capital allowances, field allowances and the Ring Fence Expenditure Supplement. Chapter 2 and Chapter B describe the current regime in more detail. Depending on the conclusions set out at Autumn Statement, there may be further phases of work and consultation on more specific areas and /or technical issues.

The review will consider how any changes in the regime could affect the future development of unconventional hydrocarbon production, including shale gas. However, as the government has only recently introduced a tax allowance for onshore activity including shale gas [footnote 13], the focus of the review will be on the taxation of offshore production (including unconventional sources) rather than onshore production.

Whilst the government will use the review to consider the structure of the main elements of the fiscal regime in future, it will not be looking at abandoning the UK’s current system, which is based on taxation of ringfenced profits, in favour of a radically different alternative such as the production sharing approaches adopted by some countries. The government believes that to do so would entail excessive disruption and uncertainty at a time when supporting investment is paramount.

Also out of scope of the review will be mainstream elements of the UK tax system as they apply to the industry and its supply chain, including income tax, National Insurance contributions, VAT and mainstream Corporation Tax, changes to which are considered in the context of the wider UK tax system.

Changes to the oil and gas fiscal regime are always made in the context of the overall UK fiscal position. The government’s top priority has been to address the largest budget deficit in the UK’s post-war history. It was in this context that the Supplementary Charge on oil and gas production was raised in 2011. The Office for Budget Responsibility is currently forecasting a small budget surplus in 2018-19. Until then and perhaps beyond, the need to continue to improve the UK public finances will remain a key element of the context in which fiscal policy for oil and gas is made.

Given this broader fiscal context, it will remain vital that the overall tax regime ensures a fair return for the nation, and that allowances are cost-effective. The government’s position is that though the fiscal regime does have an important role to play in maximising economic recovery, tax changes will not be the solution to every challenge facing the UKCS. Part of the purpose of the review is therefore to reach an understanding with industry on those areas where tax changes could have the greatest impact on the objective of maximising economic recovery.

1.3 Stakeholder engagement

HM Treasury is keen to hear from a wide range of stakeholders. Whilst this call for evidence is open HM Treasury will be looking to meet with representatives from:

- the upstream oil and gas industry

- companies involved in the upstream supply chain

- providers of finance to the industry

- non-government organisations with an interest in the future of the industry

The Treasury will be working closely with the Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC) and HM Revenue and Customs (HMRC) during this period, and will be engaging with DECC and, once it is established, the shadow Oil and Gas Authority on the question of how fiscal and regulatory regimes can best complement one another.

To facilitate conversations about detailed aspects of the fiscal regime, the government will establish four working groups with the upstream oil and gas industry covering:

- fiscal structures and principles

- the Petroleum Revenue Tax

- exploration, appraisal and new development

- asset stewardship

These groups will meet with officials during the call for evidence period at regular intervals. Chapter 4 provides more details on the issues they will cover. If you would like to be a working group member please send a nomination, identifying which group you would like to be a member of and your current position, using the correspondence details provided below.

1.4 Structure of this document

The remainder of the document is set out as follows:

- Chapter 2 describes briefly the objectives and history of the fiscal regime and its key components

- Chapter 3 sets out the issues on which responses are invited

- Chapter 4 details the working groups that the government will be running with industry

- Chapter 5 describes the key elements of the fiscal regime in more detail

1.5 How to respond to this call for evidence

The government welcomes responses from all stakeholders. It would be helpful if written responses could be organised around the key issues and questions set out in Chapter 3. Please send comments by 3 October 2014 to:

oilgasfiscalreview@hmtreasury.gsi.gov.uk

or

Matthew Ray

Oil and Gas Fiscal Review

Business and International Tax

HM Treasury

1 Horse Guards Road

London

SW1A 2HQ

Please be aware that responses may be shared with HMRC and DECC.

1.6 Confidentiality

Information provided in response to this consultation, including personal information, may be published or disclosed in accordance with the access to information regimes. These are primarily the Freedom of Information Act 2000 (FOIA), the Data Protection Act 1988 (DPA) and the Environmental Information Regulations 2004.

Please note confidential data collected in the consultation by HM Treasury will be protected under the absolute exemption at section 41 of the Freedom of Information Act. The statutory Code of Practice under section 45 of the Freedom of Information Act sets out, amongst other things, the obligations of confidence that public authorities must comply with. If you consider that the information you provide should be treated as confidential, please include an explanation of why this is the case. Please ensure that your response is marked clearly if you consider that your response should be kept confidential. An automatic confidentiality disclaimer generated by your IT system will not, by itself, be regarded as binding on the Department.

HM Treasury will process your personal data in accordance with the DPA and in the majority of circumstances this will mean that your personal data will not be disclosed to third parties.

1.7 Consultation principles

This consultation is being run in accordance with the Government’s Consultation Principles.

If you have any comments or complaints about the consultation process please contact:

Consultation Coordinator

Budget Team

HM Revenue & Customs

100 Parliament Street

London, SW1A 2BQ

Email: hmrc-consultation.co-ordinator@hmrc.gsi.gov.uk

Please do not send responses to the consultation to this address.

2. The UK oil and gas fiscal regime

Profits arising from the extraction of oil and gas in the UKCS potentially fall within two distinct fiscal regimes: Petroleum Revenue Tax and Ring Fence Corporation Tax which also incorporates a Supplementary Charge. Together, these are known as the Oil & Gas (or North Sea) fiscal regime. This chapter provides a brief overview of the current regime, its objectives and history, all of which is important context for the questions set out in Chapter 3.

2.1 The current regime

The fiscal regime which applies to the exploration and production of oil and gas in the UK and UKCS currently comprises three taxes:

- Ring Fence Corporation Tax (RFCT) – This is calculated in the same way as the mainstream corporation tax applicable to all companies but with the addition of a “ring fence”. The ring fence prevents taxable profits from oil and gas extraction in the UK and UKCS from being reduced by losses from other activities or by excessive interest payments. The current rate of tax on ring fence profits, which is set separately from the rate of mainstream corporation tax, is 30%

- Supplementary Charge (SC) – This is an additional charge, currently set at a rate of 32%, on a company’s ring fence profits (but with no deduction for finance costs)

- Petroleum Revenue Tax (PRT) – This is a field-based tax charged on profits arising from oil and gas production from individual oil fields which were given development consent before 16 March 1993

There are around 100 such fields still producing in the UKCS, of which the majority (around 60) have never been profitable enough to pay PRT. The current rate of PRT is 50%; PRT is deductible as an expense in computing profits chargeable to RFCT and SC.

Box 2.A: Marginal tax rates

The combined effect of the fiscal regime is a marginal tax rate of:

- 81% on income from PRT-paying fields

- 62% for other fields

In a similar way to mainstream corporation tax, trading losses arising within the ring fence are relievable. They can be set off sideways against other profits, group relieved, carried forward into future accounting periods or carried back against the previous year’s profits. To assist particularly those smaller companies entering the UKCS and incurring losses during the early stages of development, Ring Fence Expenditure Supplement (RFES) helps retain the value of losses incurred until they can be set off against profits, by allowing an uplift of 10% per annum, up to a maximum of six accounting periods offshore and 10 accounting periods onshore.

Oil and gas production is highly capital intensive and so the tax treatment of capital expenditure is a key element of the regime. 100% first year capital allowances are available for virtually all capital expenditure. Relief is also available for expenditure incurred when decommissioning infrastructure after production has ceased.

In recent years opportunities in the UK and UKCS have become more varied, with developments involving quite different geology, technology and infrastructure. The government has responded by introducing a suite of field allowances to allow a range of more marginal developments to become commercial. Field allowances reduce a company’s liability to SC if certain qualifying criteria are met. Since May 2010 86% of all new field approvals have received an allowance. And since its introduction in September 2012 84% of all projects in existing fields requiring approval have received the brown field allowance.

Chapter 5 provides further detail on the key elements of the regime.

2.2 Objectives and history

The government designs the fiscal regime to support its twin objectives of maximising the economic recovery of hydrocarbon resources whilst ensuring a fair return on those resources for the nation. A ‘fair return’ implies that a share of the profits should be retained for the nation, whilst ensuring returns on the private investment needed to exploit these resources is sufficient to make extraction activity commercially attractive. This is particularly important where ownership of companies by foreign investors means corporate profits flow overseas. Overseas ownership is increasingly common with companies operating in the UKCS.

In practice, the design of oil and gas taxation involves making judgements about the combination of tax measures that will achieve the right balance in meeting these objectives. A key consideration is the degree to which a lower effective tax rate will incentivise investment in more challenging fields to increase production in future. This is important not just in ensuring a future flow of tax receipts but wider economic benefits such as employment, skills, supply chain activity, exports and security of energy supply. However, these benefits need to be balanced against the risk of incurring deadweight costs – that is, reducing the return for the nation from less economically challenging fields which would have still been commercially attractive at a higher tax rate.

Another judgement is the trade-off between a simple regime which is easily understood by investors but which fails to take account of the commercial challenges of individual fields, and a more tailored regime which seeks to match tax take to the profitability of fields, but at the cost of greater complexity.

These judgements change over time as circumstances change. Some changes in tax policy are a response to changes in the commercial position of the industry, which is driven by fluctuating oil and gas prices, its cost base, and the value of future commercial opportunities. Some tax changes are a response to the wider UK fiscal position, such as the current need to reduce the fiscal deficit. Therefore – in common with other countries – the regime has been adapted over time (see table 2.A).

Table 2.A: History of the UK oil and gas fiscal regime

| Period | Key changes in regime | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mid-1970s – UK emerging as a significant producer | Introduction of PRT and RFCT in addition to a Royalty (12.5%) on gross production | |||

| 1980s – reforms to capture share of higher prices whilst encouraging new investment | a Supplementary Petroleum Duty (SPD) introduced briefly, replaced by an Advance PRT (APRT) which was soon phased out | PRT oil allowances increased | Royalty abolished for all oil fields developed after March 1982 | |

| 1993 – changes to stimulate investment during period of low prices | PRT abolished for new fields | PRT rate for existing fields reduced from 75% to 50% | ||

| 2000s – reforms to capture higher share of rising oil prices and encourage capital expenditure | SC introduced at a rate of 10% (2002) and increased to 20% (2006) | 100% first year capital allowances introduced for RFCT and SC for most capital expenditure | Exploration Expenditure Supplement introduced then replaced by RFES | Remaining Royalty abolished with effect from 2003 |

| 2008 to 2010 – new measures to incentivise investment in maturing basin | Field allowances introduced to encourage investment | Relaxation of decommissioning loss carry back rules to extend period in which losses are carried back | Operators of unexploited parts of PRT fields can apply for them to be taken outside of PRT | |

| 2011 to 2014 – further action to encourage investment in marginal developments; main rate increase at time of record high oil prices and fiscal consolidation | SC rate increased to 32% | Field allowances expanded (including brown field allowance) | Introduction of Decommissioning Relief Deeds |

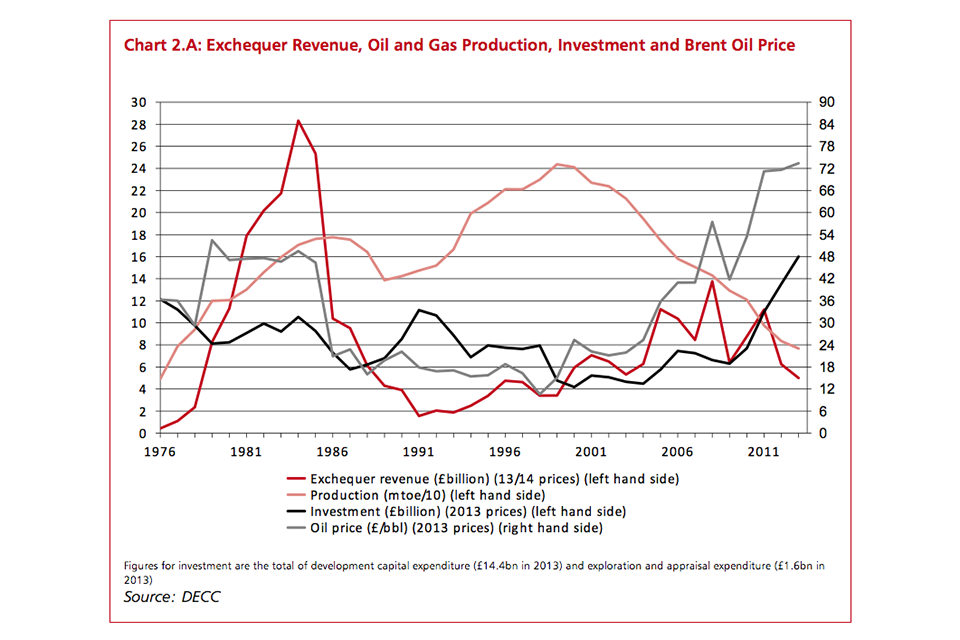

Oil and gas tax receipts have fluctuated over time, as a result of changes in prices, costs, production levels and the fiscal regime (see Chart 2.A). The early 1980s saw revenues peak as production ramped up during a period of high prices. In the late 1980s revenues fell driven by falling prices and production. The 1990s were a period of relatively low revenues due to low oil prices and a comparatively low tax rate. But as prices rose significantly in the 2000s, the tax rate was increased to ensure the nation took a fair share of the benefits. This period also saw significant rises in investment by the industry from an historic low in 2000 to a record high in 2013, partly in response to the introduction of field allowances.

Chart 2.A: Exchequer Revenue, Oil and Gas Production, Investment and Brent Oil Price

Chart 2.A: Exchequer Revenue, Oil and Gas Production, Investment and Brent Oil Price

Figures for investment are the total of development capital expenditure (£14.4bn in 2013) and exploration and appraisal expenditure (£1.6bn in 2013)

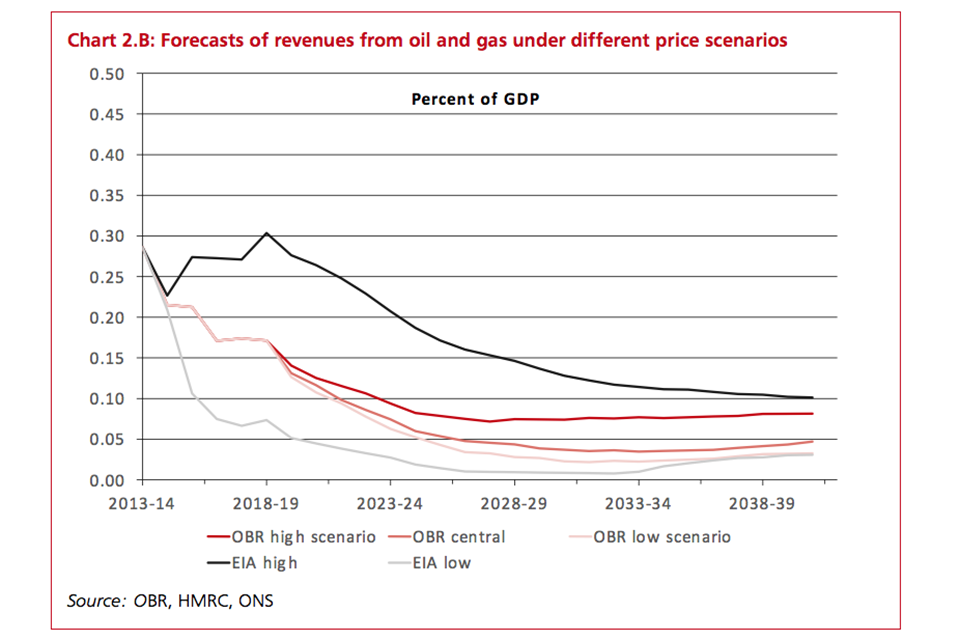

In terms of future receipts, the Office for Budget Responsibility’s (OBR) latest forecasts suggest that that oil and gas revenues will decline until the 2020s and thereafter remain low, averaging around 0.06 per cent of GDP between 2019-20 and 2040-41, around a fifth of the level recorded in 2013-14 [footnote 14]. This is a result of the gradual decline in production as the UKCS matures. Chart 2.B shows this forecast alongside estimated revenues for other price scenarios, demonstrating the uncertainties inherent in making such forecasts. Since 2002-03 the average absolute percentage change in oil and gas revenues from one year to the next has been nearly 35% – compared with just 5% for income tax or 7% for VAT. As the OBR notes, ‘oil and gas receipts are the most volatile revenue streams in the UK public finances and forecasting them over even short horizons is extremely difficult’. In the context of uncertain and declining tax revenues, the wider economic benefits of oil and gas production to the UK such as employment and exportable skills will potentially become relatively more important.

Chart 2.B: Forecasts of revenues from oil and gas under different price scenarios

Chart 2.B: Forecasts of revenues from oil and gas under different price scenarios

3. Questions for stakeholders

The government would particularly welcome views on the questions listed below. Questions are grouped around some of the key issues highlighted in Chapters 1 and 2.

Responses should be supported by evidence, including on the impact of possible changes on specific project economics or production levels where possible. The government is interested in receiving quantitative data and case examples where they can help to illuminate the issues. [footnote 15]

3.1 Adapting to the changing economics of the basin

As set out in Chapter 2, the fiscal regime has changed over time reflecting changing economics in the basin. The government is interested in hearing views from stakeholders as to how the regime should continue to evolve over the coming decades in order to incentivise the recovery of resources and ensure a fair return for the nation. Though there remain significant resources to exploit, as the basin matures commercial activity will become more focused on more marginal projects and on decommissioning, and offshore production will gradually decline. Although tax receipts are likely to fall the UK will continue to benefit from having a successful industry supporting employment and developing skills and technologies that can be exported overseas.

Questions

| 1. How do stakeholders expect economics of UKCS projects to evolve over the coming decades, including new and incremental investments? Would stakeholders expect to see greater variety in field economics than has been the case in the past? How could evolution in the fiscal regime support the objective of maximising economic recovery as the economics of the basin change? |

| 2. How will the changing economics of the basin affect risk? What is the role of the fiscal regime in sharing risk between industry and government? |

| 3. In recent years prices for oil and gas have diverged, with the result that gas production is relatively less economic. This is particularly an issue in the Southern North Sea, which is largely a gas producing region. To what extent should the fiscal regime reflect the differing economics of oil and gas production, and of different regions in the UKCS? |

| 4. Decommissioning will become an increasingly important activity in the UKCS in the coming decades. Is the fiscal regime set up to ensure that decommissioning will be undertaken in the most cost-effective way? |

3.2 Creating stability in an uncertain environment

The oil and gas industry is characterised by cyclicality, with returns heavily dependent on commodity prices and input costs, both of which are highly variable. As set out in Chapter 2, revenues are volatile and difficult to predict. A stable fiscal regime needs to ensure a fair share of returns between industry and government not just now but for decades to come, during which time prices and costs will continue to vary. If the fiscal regime is to be resilient to changing circumstances and remain fit for purpose, it must have some degree of flexibility or else there will inevitably be periods when the industry may either be making profits that are seen to be excessive, or struggling to make any profit at all.

Questions

| 5. How sensitive are project economics to changes in commodity price/input costs? |

| 6. How can the government ensure the regime provides certainty and stability even as prices and costs change? What criteria should apply in judging any changes to the regime? |

| 7. Do stakeholders have evidence of specific areas of the tax regime where changes could improve certainty for investors? |

3.3 Helping the UKCS compete for investment

The oil and gas industry is a global one and developments in the UKCS must compete for capital, skills and infrastructure. In judging relative competitiveness the tax regime is an important factor although other factors such as skills, regulation, and political stability are also important. Some industry players have argued that the complexity of the current regime reduces competitiveness, as global investors may not factor in the various reliefs included in the UK regime in making decisions on project sanction.

Questions

| 8. Is there evidence that the UKCS is becoming uncompetitive and if so, to what extent is the fiscal regime contributing to this? What range of options is there to ensure the UKCS is perceived by investors as attractive to invest in? |

3.4 Simplifying the regime

As set out in Chapter 2 and Chapter 5 the regime includes three different taxes with a range of reliefs and allowances, which have increased in number and scope in recent years. There may be benefits to simplifying the regime but this could mean it is less tailored to the economics of individual fields.

Questions

| 9. What are the advantages and disadvantages of the more bespoke allowances introduced in recent years? How can any disadvantages be mitigated? What would be the pros and cons of reverting to a simpler regime with fewer or no allowances and what would need to be considered as part of that transition? |

| 10. PRT is a complex tax but only applies to fields given development consent before 16 March 1993. The Treasury held several rounds of discussion with industry over the future of PRT in 2007 and 2008, and the government would welcome views on whether developments since would suggest that the conclusions of that work should be revisited. [footnote 16] What should be the future of PRT and why? |

3.5 Helping to maximise economic recovery

The Wood Review identified a number of areas of action including a new regulatory approach, the need for operators to focus on maximising economic recovery as well as pursuing individual commercial objectives, the need for greater collaboration between operators, and better implementation of industry strategies, all of which should support the objective of maximising economic recovery.

Questions

| 11. How can the fiscal regime best support the themes of the Wood Review? |

| 12. The main way in which the fiscal regime currently helps maximise economic recovery is through the system of field allowances which help make more marginal projects commercially viable. It is important that allowances are cost effective and prioritised where they can achieve greatest impact. Are field allowances targeted on the most valuable projects to maximise economic recovery? |

| 13. The Wood Review also identified asset stewardship and technology as key issues, including aging infrastructure, under-investment in assets and insufficient uptake of Improved Oil Recovery and Enhanced Oil Recovery techniques and technologies. What evidence is there that the fiscal regime could support action in these areas? |

| 14. Exploration rates have been relatively low since 2009. What evidence is there that further action on fiscal policy could have a meaningful impact on exploration rates? |

| 15. Investment in existing fields is becoming increasingly important as part of maximising economic recovery. How do the economics of incremental investments differ from other developments and does that justify a different tax treatment? How effective has the brownfield allowance been in supporting incremental investment? |

4. Working groups

As part of the call for evidence process, the government will establish four working groups which will be run with assistance from Oil & Gas UK. These will be made up of industry representatives to discuss detailed aspects of the fiscal regime as they impact industry activity. As set out in Chapter 1, HM Treasury would also welcome views from other stakeholders through written responses or, where possible, through separate meetings.

4.1 Working group 1: Fiscal structures and principles

This group will look at the overall shape and structures of the ringfenced regime, looking at how we can ensure it remains fit for purpose over the basin’s remaining lifetime, reflecting the economics of the basin as they change. The group will consider:

- the overall competitiveness of the regime and its impact on attracting investment to the UKCS

- the appropriate balance of risk and reward between industry and government and how this is reflected in tax rates and allowances

- what principles should inform changes to the regime in future

- how the fiscal system can support the key themes of the Wood Review

- the pros and cons of the more bespoke, but more complex, system of field allowances that have been put in place over recent years, and how allowance should evolve over time

- whether and how the fiscal regime should reflect the differing economics of oil and gas, including economics of the southern north sea

The group will maintain an overview of all the issues and questions raised in Chapter 3.

4.2 Working group 2: Petroleum Revenue Tax

This group will take a strategic look at the future of PRT, considering:

- whether the conclusions of previous consultation in 2007 to 2008 on the future of PRT still stand

- what options exist to ensure PRT is not a barrier to investment

Questions 10 and 15 in Chapter 3 are particularly relevant to this group.

4.3 Working group 3: Exploration, appraisal and new development

This group will look at interactions between the fiscal regime and exploration and early life developments. The group will consider:

- to what extent recent trends in exploration are a fiscal issue

- how well existing fiscal incentives are working to encourage / de-risk exploration, appraisal and the early stages of new developments

- interactions between the fiscal regime and access to infrastructure

Questions 11, 13 and 14 in Chapter 3 are particularly relevant to this group.

4.4 Working group 4: Asset stewardship

This group will look at interactions between the fiscal regime and strong asset stewardship. The group will consider:

- whether the economics of late life investment justifies a different tax treatment

- interactions between the fiscal regime and maintaining aging infrastructure

- the effectiveness of the brownfield allowance

- the tax treatment of decommissioning

Questions 4, 13 and 15 in Chapter 3 are particularly relevant to this group.

5. Key elements of the fiscal regime

This chapter sets out more detail on the key elements of the fiscal regime.

5.1 Petroleum Revenue Tax

PRT was introduced by the Oil Taxation Act 1975 and repealed by Finance Act 1993 for all fields given development consent on or after 16 March 1993. There are around 100 such fields still producing in the UKCS. Of these fields, the majority (around 60) have never been profitable enough to pay PRT, mainly due to oil allowance which is outlined below. In Finance Act 2008, the government legislated to give HMRC the power to remove fields that are unlikely ever to pay PRT from the PRT regime if all companies party to the licence in any such field so elect.

PRT is a field-based tax. Fields liable to PRT are currently charged at 50% on their net profits from oil and gas won under licence in the UKCS. There are a number of reliefs and allowances that protect smaller and less profitable fields from paying this tax, which were intended to encourage investment in and exploration for such fields. The main allowances and reliefs are:

- Safeguard – is intended to guarantee companies a specific return on their capital before they have to pay PRT. Availability of relief is limited to a prescribed number of chargeable periods. Relief under safeguard is against a participator’s PRT liability and is therefore applicable only once all expenditure and other reliefs have been taken into account in the PRT computation

- Oil Allowance – ensures that for at least the first ten years of a field’s life (and often for much longer), a substantial slice of production is free from PRT. Except for safeguard relief, oil allowance is given only after all other expenditure and reliefs have been allowed. The allowance is field-based in that if a participator has insufficient profits in a particular chargeable field to absorb the allowance, it is not carried back or forward by the company, but rather it remains available for later use in the field

PRT is charged in respect of profits from oil (for most PRT purposes ‘oil’ refers also to gas and other hydrocarbon products) won under a licence issued by the Secretary of State for Energy and Climate Change. It is assessed on each participator in an oil field.

For PRT purposes, companies have to make a number of returns for what are termed ‘chargeable periods’. There are two six-month ‘chargeable periods’ each year. PRT can produce an assessable profit or an allowable loss. Where there is an allowable loss, this is carried forward to set against assessable profits from the same field in later periods without time limit, unless the participator claims to have it carried back against earlier profits from the same field, again with no time limit.

If the field reaches the end of its productive life and decommissioning costs are incurred, to the extent that such costs are deductible for PRT purposes, any losses arising can be carried back for offset against profits from the field without limit, subject to the retention of the licence or within two chargeable periods of the relinquishment of the licence.

Any losses still unused (termed Unrelievable Field Losses (UFLs)) may be set against profits from another field owned by the same company (or an associate thereof) and are relieved in that field in the same way as other non-field expenditure.

PRT is deductible in arriving at profits charged to RFCT and the SC (both described below) – a PRT paying field will therefore have a marginal tax rate of 81%.

5.2 Ring Fence Corporation Tax

Corporation tax on upstream oil and gas profits is levied at 30%. It is subject to special rules, which were first introduced in 1975 to ensure the UK gains the proper benefit from UKCS oil extraction activities. The main purpose and effect of these rules is to stop profits from oil extraction activities and oil rights in the UK and UKCS being reduced for tax purposes by losses from other trading activities.

This is achieved by virtue of a ‘ring fence’ being placed around these profits and the normal rules, which would otherwise allow the profits to be reduced by losses from other activities carried out by the company, or from losses other than from UK oil extraction activities accruing to other companies in the same corporate group, are disapplied. The rules work by treating the ring-fenced activities as a separate trade, and then preventing trading losses being set against income from oil extraction activities or oil rights (and ring fence chargeable gains) except insofar as they are losses derived from those activities.

Virtually all capital expenditure incurred in the UKCS, including putting the plant and machinery in place, or in dismantling it at the end of the life of an oil field, now qualifies for 100% first year allowances (FYAs), allowing the cost to be written off for tax purposes in the accounting period in which the expenditure is incurred. The general rules applying to capital expenditure incurred in a ring fence trade are set out below:

- capital allowances. There are 100% FYAs for expenditure on plant and machinery for use wholly within a ring fence trade including, since Finance Act 2008, long life assets (LLAs), (those with a useful economic life of at least 25 years)

- decommissioning expenditure in the UKCS. Nearly all decommissioning expenditure is capital in nature and is relieved under the capital allowances legislation. Since Finance Act 2008, virtually all capital expenditure on decommissioning plant and machinery, whenever incurred, now attracts 100% FYAs

- corporation tax loss relief for decommissioning expenditure. Since Finance Act 2008, losses arising as a result of decommissioning expenditure are allowable against a company’s ring fence and other profits in the year in which the loss was incurred. They can be carried forward against ring fence profits and/or carried back against total profits for three years. In addition, where there are sufficient losses, they can then be carried back against a company’s ring fence profits to 17 April 2002

- corporation tax post-cessation period. Prior to Finance Act 2008 the fiscal regime allowed decommissioning expenditure incurred in the 3 years after the cessation of the ring fence trade to be treated as if it were incurred in the last period of trading. Finance Act 2008 extended this ‘post cessation period’ so it now runs to the point where DECC publish their ‘close-out’ report, which confirms that decommissioning has been completed. In this way companies are assured of obtaining relief for all their allowable decommissioning costs

Whilst profits from oil extraction activities are ring fenced, trading losses arising from such activities are relievable for corporation tax in the same way as losses from other trading activities. Ring fence losses can be set off sideways against other profits, group relieved, carried forward into future accounting periods or carried back against the previous year’s profits. The ring fence also contains RFES, targeted particularly at those smaller companies entering the UKCS and incurring losses that they are unable to offset against other profits. RFES helps retain the value of losses incurred until they can be set off against profits, by allowing an uplift of 10% per annum, up to a maximum of six accounting periods offshore and 10 accounting periods onshore.

5.3 Supplementary charge

Finance Act 2002 introduced an SC of 10% on adjusted ring fence profits. Adjusted ring fence profits are the amount of profit or loss arising from any ring fenced activities, excluding any financing costs. The rate of SC was increased in Finance Act 2006 to 20% and was further increased to 32% in Finance Act 2011, while at the same time relief for decommissioning costs effectively remained at the existing 20% rate.

The overall effect of the fiscal regime when PRT, RFCT and SC are combined is a marginal tax rate of:

- 81% on income from PRT-paying fields

- 62% for other fields

5.4 Field allowances

The government provides support through field allowances for technically and commercially challenging projects that are economic but commercially marginal under the current tax rates. Fields that qualify for allowances obtain relief against the 32% SC on a slice of their profits. On these profits, companies pay tax at 30% or 65% (depending on the age of the field), instead of 62% or 81%. For example, companies receive an £800m allowance for ultra heavy oil fields that meet certain qualifying criteria. This means that on £800m of their profits, companies will not have to pay the SC but only RFCT – equating to £256m of tax relief.

Finance Act 2009 introduced a field allowance for small fields, which provided relief against adjusted ring fence profits chargeable to SC. In successive Finance Acts the field allowance has been extended to include ultra high pressure/high temperature, ultra heavy oil, deep water gas, large deep water oil and large shallow water gas fields. In addition, a relief for incremental investment in existing fields (the “brown field allowance”) was introduced with effect from September 2012.

A new onshore allowance is currently being taken through Finance Bill 2014, effective from 5 December 2013. In addition, there will be a consultation shortly with a view to introducing a new cluster allowance for areas with ultra high pressure, high temperature potential.

5.5 Decommissioning Relief Deeds

The UKCS is one of the oldest areas of oil production in the world and contains a lot of ageing infrastructure. Some current estimates of the cost of decommissioning all assets in the UKCS (wells, platforms, pipelines etc) are in excess of £35 billion. There are special rules for the treatment of decommissioning costs for the purposes of RFCT as outlined above. In order to encourage future investment and provide certainty around the amount of relief available from decommissioning costs in FA 2013 the government introduced DRDs to provide industry with certainty and to encourage future investment.

The DRD is an agreement between a company and the government. One of the main purposes of the DRD is to underpin the quantum of expenditure that qualifies for tax relief in perpetuity based on Finance Act 2013. Any changes to the tax legislation made after Royal Assent to Finance Act 2013 that reduce the amount of relief available in respect of decommissioning expenditure will trigger a payment under the DRD. If this happens, the company can make a claim under the DRD and the government will make a payment to restore the total relief paid to the company to Finance Act 2013 levels. This provides industry with certainty over the availability of decommissioning relief in future years.

In addition, the DRD guarantees a certain level of relief in the event of a default by a company on its decommissioning liabilities and another company is required by the Department of Energy and Climate Change to meet those (default) costs. This enables companies to post decommissioning security on a post-tax basis rather than for the whole of the cost. This reduces the annual payment made by companies in respect of decommissioning liabilities and in addition frees up capital for investment.

5.6 Chargeable gains

Broadly, a chargeable gain arises when the consideration from the disposal of an asset exceeds its purchase cost plus any other costs and indexation relief allowed in computing the gain. In general, the standard UK capital gains taxation rules are applied within the ring fence.

When an oil or gas interest is sold, typically the purchase price will include an estimate of both the value of the hydrocarbons in the ground and the associated physical infrastructure. Most of the infrastructure is plant and machinery, which depreciates, and is therefore unlikely to give rise to a gain on disposal. Any gain that does arise is likely to relate to the increase in the value of the unexploited hydrocarbons during the period of ownership, and possibly other factors such as geography. For example a hub might have more value if other fields have been discovered in its vicinity and conversely a newly built hub or pipeline nearby might also increase the value of the hydrocarbons in a nearby field.

Where a company disposes of an asset used for oil and gas activities, and reinvests all of the proceeds into new oil and gas assets or exploration activities within certain time limits, reinvestment relief provides that no chargeable gain arises.

Where a company disposes of a field interest by selling the company that holds the licence interest, rather than selling the actual licence interest itself, there is the possibility of the substantial shareholdings exemption applying. Provided certain conditions are met, including minimum share ownership, period of ownership and the status of the investing company then any gain is exempt from tax.

-

In simple terms, maximising economic recovery means ensuring that all resources are recovered where the benefits of recovery outweigh the costs, in such a way as to maximise value in current terms for the UKCS overall. A key priority for the new Oil and Gas Authority will be developing what this means in practice and a strategy for achieving it. ↩

-

DECC figures ↩

-

DECC figures ↩

-

‘Economic Report 2013’, Oil & Gas UK, 2013 ↩

-

HMRC figures ↩

-

DECC estimates ↩

-

‘Activity Survey 2014’, Oil & Gas UK, 2014 ↩

-

DECC figures ↩

-

The ratio of a field’s actual production performance against its maximum capability. ↩

-

‘Activity Survey 2014’, Oil & Gas UK, 2014 ↩

-

‘UKCS Maximising Recovery Review: Final Report’, Sir Ian Wood, February 2014 ↩

-

The government’s formal response to the Wood Review will be published shortly ↩

-

The onshore oil and gas allowance was introduced at Autumn Statement 2013 with immediate effect ↩

-

‘Fiscal Sustainability Report’, Office for Budget Responsibility, July 2014 ↩

-

Confidential data collected as part of this call for evidence by HM Treasury will be protected under the absolute exemption at section 41 of the Freedom of Information Act. The statutory Code of Practice under section 45 of the Freedom of Information Act sets out, amongst other things, the obligations of confidence that public authorities must comply with. If you consider that the information you provide should be treated as confidential, please include an explanation of why this is the case. Please ensure that your response is marked clearly if you consider that your response should be kept confidential. An automatic confidentiality disclaimer generated by your IT system will not, by itself, be regarded as binding. ↩

-

‘The North Sea Fiscal Regime: a discussion paper’, HM Treasury, March 2007; ‘Securing a sustainable future: a consultation on the North Sea Fiscal Regime’, HM Treasury, December 2007; ‘Supporting investment: a consultation on the North Sea fiscal regime’, HM Treasury, November 2008. ↩