Mining and quarrying in the UK

Published 20 December 2019

Ahead of collection and publication of information on extractive-related payments to the UK government in 2018, the UK EITI Multi-Stakeholder Group (MSG) decided to exclude such payments to the Coal Authority. These payments are no longer material relative to overall government revenues and the MSG believes that their exclusion will not affect the comprehensiveness of UK EITI reporting. The continuing economic contribution of the coal sector is, though, still included in the background information set out below.

Production

The UK has relatively diverse and large deposits of minerals that have been mined historically. Key sectors include:

- energy minerals – coal

- construction minerals – aggregates, brick clay and cement raw materials

- industrial minerals – kaolin (china clay) and ball clay, silica sand, gypsum, potash, salt, industrial carbonates, fluorspar and barytes

- metal minerals – tungsten, gold

The largest bulk market for non-energy minerals is construction. Industrial minerals extracted and used in the UK range from those used primarily domestically (for example, silica sand and limestone for glassmaking, iron and steel manufacture) and minerals such as kaolin, ball clay and potash, which have significant international markets. Mineral production supports a wide variety of upstream, midstream and downstream industries.

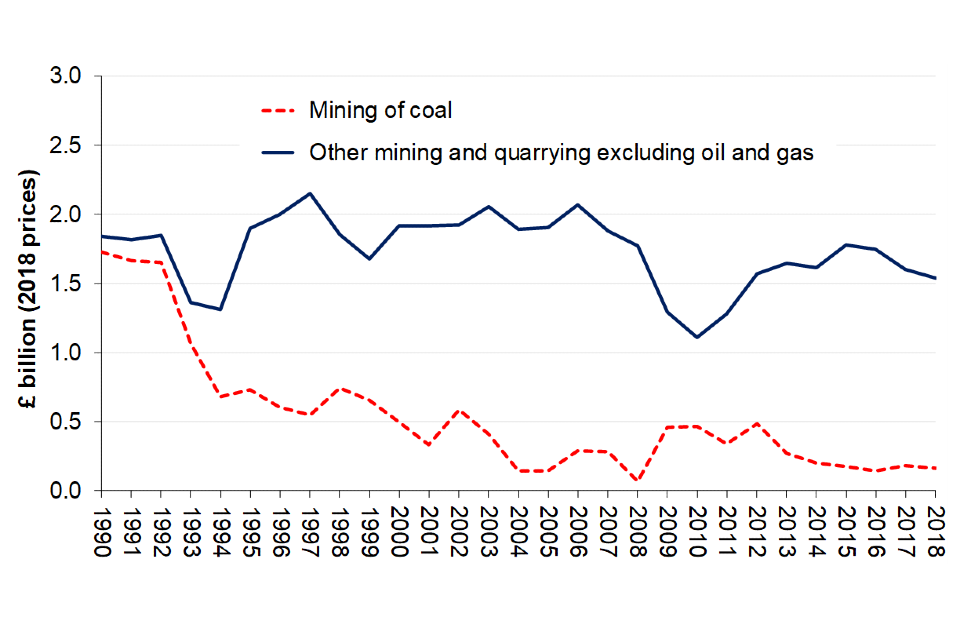

UK mining and quarrying non-coal production has been broadly flat in recent years while coal production volumes have consistently fallen for the past three decades.

Figure 1. GVA of UK mining and quarrying (excluding oil and gas) 1990–2018

Source: ONS, UK GDP(O) low level aggregates, 21 December 2018

Production and trade

Although the UK has significant domestic supply of some minerals, it is a net importer of many minerals and mineral-based products, particularly metals, and in the long term has experienced a balance of trade deficit. UK mineral exports and imports have both increased in recent years. However, imports and exports of the largest minerals flow, aggregates, are relatively low, accounting for less than 5% of the market[footnote 1].

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) publish data on the volume of production and trade of metal ores and non-metallic minerals in its material flows account for the UK while they also report on the value of imports and exports. These data have yet to be verified so they are not included here to avoid giving a misleading impression of the scale of the sector.

Legal framework

Extraction of minerals is subject to the UK’s mineral planning process. The aim of mineral planning is to facilitate the sustainable supply and use of minerals. Mineral working is not a permanent use of land, and extraction sites are usually restored for beneficial after-use.

Mineral planning policy is devolved and set out in the National Planning Policy Framework (England), Planning Policy Wales and National Planning Framework for Scotland 3. In Northern Ireland, policy and guidance are provided through documents such as the Strategic Planning Policy Statement for Northern Ireland, which partly supersedes the Planning Strategy for Rural Northern Ireland. In Northern Ireland since 1 April 2015 responsibility for planning is shared between the Department of the Environment (from 8 May 2016 in respect of planning, the Department of Infrastructure; Department of Infrastructure planning page and the 11 local councils. Exploration for and extraction of metalliferous and industrial minerals are licensed by the Department for the Economy in Northern Ireland under the Mineral Development (Northern Ireland) Act 1969. The UK framework is supported by technical documents providing guidance on particular issues of mineral planning. The focus of the mineral planning process is on whether the development itself is an acceptable use of the land[footnote 2].

Mineral planning and decisions on planning applications are a responsibility of a local authority body designated as the Mineral Planning Authority (MPA). In Wales, Scotland and some parts of England MPAs are Unitary Authorities. In Wales, Local Planning Authorities including Local Authorities and National Parks Authorities are responsible for minerals planning. In most of England MPAs are the County Councils or National Parks. In Northern Ireland, the Minerals Unit, part of the Planning Service of the Department of the Environment, was responsible for minerals planning until 1 April 2015[footnote 3].

MPAs have 4 areas of planning responsibility:

- planning to guide future developments

- safeguarding mineral resources

- managing developments by deciding on planning applications

- monitoring and enforcement of existing planning permissions

Some minerals permissions last for many years, and there may be a need for periodic reviews of the planning conditions attached to that permission. MPAs control mineral developments under the orders established under the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 (Section 97, Part II of Schedule 5, and Schedule 9)[footnote 4].

Minerals extraction may only take place if the operator has the agreement of the landowner and has obtained both a planning permission from the MPA and any other permits and approvals. The latter may include:

- permits relating to surface water, groundwater and mining waste, issued by the Environment Agency (under UK legislation related to the EU Water Framework Directive and Mining Waste Directive)

- where appropriate, European Protected Species Licences, issued by Natural England

- where appropriate heritage asset consents issued by Historic England

- licences for exploration and extraction of coal, or agreements to enter into or pass through a coal seam to extract any other mineral, need to be granted by the Coal Authority

- licences for exploration and extraction of minerals managed by The Crown Estate (TCE) need to be obtained from the latter[footnote 5]

Additional consents, such as relating to diverting and reinstating rights of way or temporary road orders, may need to be obtained. Additional rights of way and land use may need to be secured from landowners. Active mining and quarrying operations are also regulated by the Health and Safety Executive (in Great Britain). The corresponding Northern Ireland regulatory authority is the Health and Safety Executive for Northern Ireland (HSENI).

Marine plans are being developed by each of the UK marine planning authorities in accordance with the requirements of the Marine and Coastal Access Act 2009 and the UK Marine Policy Statement. Each marine plan will set out policy to support public authorities determining licensing applications including those for marine minerals and oil and gas extraction[footnote 6].

A marine plan:

- sets out priorities and directions for future development within the plan area

- informs sustainable use of marine resources

- helps marine users understand the best locations for their activities, including where new developments may be appropriate

Relevant public authorities must take their decisions in accordance with the relevant marine planning documents, that is the UK Marine Policy Statement and any marine plan prepared and adopted by the marine planning authority.

Information about mineral planning and environmental permitting within the UK’s devolved administrations is available as follows:

- Scottish Government, Guide to the Planning System in Scotland

- Northern Ireland Environment Agency (NIEA) and Scottish Environment Protection Agency (SEPA), NetRegs: Environmental Guidance for Your Business in Northern Ireland and Scotland

- Northern Ireland Planning Service, Minerals Planning

- Welsh Government, Planning

- Natural Resources Wales, Mining waste

Licensing, fiscal regime and revenue streams

Mineral ownership and licensing

With the exception of oil, gas, coal, gold and silver, mineral rights in Great Britain[footnote 7] vest in landowners rather than the state. It follows that there is no single, national licensing system for the exploration and extraction of such privately owned minerals. While planning permissions and environmental permits are generally required for such purposes, these are not licences.

Where mineral rights belong to a private landowner, permission for exploration must be received from the landowner. As TCE and (in GB) the Forestry Commission manage land on behalf of The Crown, they also issue exploration and extraction licences for mineral deposits under their management and grant access right permits (wayleaves). In some cases, mineral rights can be managed by a private agent on behalf of a public body (TCE and Forestry Commission Scotland).

Coal Authority

The Coal Authority is a regulatory executive non-departmental public body, established in 1994 when the industry was privatised. It is sponsored by BEIS. The Authority owns, on behalf of the State, the majority of unworked coal and abandoned underground coal mine workings in GB and regulates and grants licences for working of coal and underground coal gasification (UCG), together with agreements to enter its coal estate for other processes such as:

- coal bed methane extraction

- abandoned mine methane extraction

- mine water heat recovery

- deep energy exploitation (for example geothermal, shale gas)

The Coal Authority holds an offline public registry of licences and does not publish licences online. Information about coal licences can be requested by post and email[footnote 8]. The Authority provides online coal mining data including on licence areas and known areas of activity.

Coal Authority revenue streams include:

- fees for statutory licences, either operating or conditional (where the licensee is yet to secure planning permission) for surface and underground coal mining operations and UCG

- fees for licences for coal exploration

- production-related rents under coal leases which transfer the property interest in the coal to the licensee when holding an operating licence

- fees and royalties for digging and carrying away coal during non-coal-related development (Incidental Coal Agreement)

- fees for agreements to access or pass through the Authority’s coal estate for processes such as coal bed methane and abandoned mine methane extraction, mine water heat recovery and deep energy exploitation (for example geothermal, shale gas)

- payments for coal rights under options for lease (granted with conditional licences) and rights for pillars of support in coal

Further information on licensing activity can be obtained from the Coal Authority.

Northern Ireland

With certain exceptions, mineral rights in Northern Ireland[footnote 9] are vested in the Department for the Economy (DfE). The DfE publishes a description of the process for the award of Mineral Prospecting Licences (MPLs) and consults publicly on applications. Applications are accepted on a “first come, first served” basis, although there is provision for a competitive process where there is more than one interest in an area.

The Crown Estate and Crown Estate Scotland: marine licences

The Crown Estate (TCE) manages the seabed to the 12-nautical mile territorial limit and other rights including non-energy mineral rights out to 200 nautical miles in all parts of the UK excluding Scottish territorials waters and the Scottish offshore zone, where Crown Estate Scotland manages these rights. TCE typically awards, through a market-based tendering process, commercial agreements to companies to explore for or extract marine aggregate minerals, and it collects royalties for minerals extracted. All licensed application and exploration/option marine aggregate area details are published online and are available at no charge.

TCE does not disclose contracts and agreements relating to minerals where they contain commercially confidential information. There are no currently commercial marine aggregate extraction licenses in Scotland, future proposals would lead to an equivalent process with the relevant seabed manager.

Such rights and options can only be exercised once the necessary regulatory consent (marine licence) is obtained under the Marine and Coastal Access Act 2009 or Marine (Scotland) Act 2010 from the national regulator – the Marine Management Organisation (MMO) in England, Natural Resources Wales (NRW), Marine Scotland or in Northern Ireland the Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs (DAERA) – according to location[footnote 10]. All regulators are required to keep a public register of marine licences they have issued[footnote 11]. Applications for marine licences must be publicised to allow anyone who is interested a chance to object[footnote 12].

Revenue streams for marine aggregates comprise:

- marine licence payments of fees and relevant charges to the relevant regulator

- rent and production royalty payments to TCE[footnote 13]

The Crown Estate and Crown Estate Scotland: terrestrial minerals

TCE also grants mineral leases across England and Wales (except in Scotland) for land-based mineral extraction operations, including sand, gravel, hard rock, dimension stone and slate. It charges royalties for minerals extracted. Lease conditions and royalty payment provisions are negotiated on an open market and case-by-case basis. Crown Estate Scotland undertakes the same process for minerals on Scottish Crown Estate assets.

TCE also manages the right to gold and silver (“Mines Royal”)[footnote 14], in England and Wales, but there is no significant gold or silver production in these areas.

In Northern Ireland under the Mineral Development (Northern Ireland) Act 1969 with certain exceptions (exceptions include gold and silver) all mineral rights are vested in the Department for the Economy (DfE). Since 1970 the mineral rights specified in the 1969 Act are held in public ownership.

In Scotland, Crown Estate Scotland manages the rights to Mines Royal across most of Scotland. Planning permission was granted in Autumn 2018 for a gold mine at Cononish, Tyndrum. Crown Estate Scotland has granted lease rights to the operator for the extraction of gold and silver.

Local Planning Authorities (planning obligations payments)

Planning obligations are agreements made between a planning applicant (including the freehold owner of land where the operator only has a minerals lease) and a Local Planning Authority (LPA) under section 106 of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 in England and Wales, section 75 of the Town and Country Planning (Scotland) Act 1997 (as amended by the Planning etc. (Scotland) Act 2006) in Scotland and Article 40 of the Planning (Northern Ireland) Order 1991. Planning obligation payments are site-specific and negotiated case by case. They may comprise:

- monetary payments to LPAs

- “in-kind” infrastructure provisions: mainly off-site provisions, (on-site provisions within the boundary of a planning permission are theoretically possible but more likely to be included in planning conditions rather than under planning obligations)

The difference between off- and on-site “in-kind” infrastructure provisions can be understood as between provisions that benefit the local community and those used by the extractive company itself. Only monetary payments and off-site provisions are in scope for the UK EITI.

Planning obligations can be short term, such as obligations to carry out works before the extraction can take place, or long term, such as obligations to restore or provide after-care of extraction sites.

Obligations are recorded in online planning registries kept by LPAs, but payments owed or made are not always recorded, and no central registry of such planning obligations or relevant payments exists.

Fiscal regime

Mining and quarrying companies pay corporation tax (CT) on their profits at the standard rate, unlike profits from oil and gas extraction, which are subject to Ring Fence CT regime. Profits from upstream and downstream activities are not separated, and such companies pay a single amount of CT on the profits arising from all their activities. It is therefore not possible to say how much of the taxes paid by the companies whose tax payments are reported here related to their extractive activities nor what the total of such taxes was (and therefore what proportion of the total is covered by this report).

Companies based in the UK have to pay CT on all their taxable profits, wherever in the world those profits originate, although double taxation relief is available where appropriate to avoid the same profits being taxed twice. Companies not based in the UK, but with branches operating in the UK, have to pay CT on taxable profits arising from their UK activities. CT payments by mining and quarrying companies are included in the scope of the UK EITI. The figures reported are for total CT and include tax on both upstream and downstream activities. Corporation tax is paid by a small number of larger companies whose activities are primarily downstream.

Capital allowances are a feature of business taxation in the UK and apply to the mainstream CT regime (as well as to income tax). For CT purposes, the general rule is that capital expenditure is not allowed as a deduction for tax purposes. This means that profits chargeable to CT cannot be reduced by depreciation or similar expenses. The capital allowance regime exists to provide some relief for capital expenditure incurred. The main allowance which is commonly relevant for companies carrying on mining and quarrying activities is Mineral Extraction Allowance (MEA).

There are several other payment streams, such as the Aggregates Levy, which involve payments from extractive companies to the Exchequer. These are outside the scope of EITI as they are indirect taxes not direct taxes. They are documented by the ONS in its annual publications on environmental accounts and environmental taxes[footnote 15].

Mineral subsectors

Coal

The majority of coal output comes from surface mining (opencast) sites in Scotland, North East England and South Wales. UK coal production peaked in 1913 and has been contracting, with fluctuations, since the mid-twentieth century, with the sharpest decline in the 1990s. Electricity-generating power stations currently account for most of the UK’s coal consumption.

Table 1: Volume & value of UK production, gross UK exports and imports and net exports of coal

a. Volume (million tonnes of oil equivalent) of UK production

| Volume (million tonnes of oil equivalent) | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UK production | 7.3 | 5.4 | 2.7 | 2.0 | 1.7 |

| Gross exports | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.4 |

| Gross imports | 27.6 | 14.9 | 6.0 | 5.7 | 6.8 |

| Net exports | -27.3 | -14.6 | -5.7 | -5.4 | -6.3 |

b. Volume (million tonnes) of UK production

| Volume (million tonnes) | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deep-mined production | 3.7 | 2.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Surface-mined production | 8.0 | 5.8 | 4.2 | 3.0 | 2.6 |

| Total production | 11.6 | 8.6 | 4.2 | 3.0 | 2.6 |

| Gross exports | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.6 |

| Gross imports | 42.2 | 22.5 | 8.9 | 8.5 | 10.1 |

| Net exports | -41.8 | -22.1 | -8.5 | -8.0 | -9.5 |

c. Value (£ million) of UK production

| Value (£ million) | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UK production | 390 | 245 | 125 | 190 | 160 |

| Gross exports | 55 | 45 | 50 | 60 | 85 |

| Gross imports | 2,260 | 985 | 590 | 725 | 825 |

| Net exports | -2,205 | -940 | -540 | -665 | -740 |

Source: Digest of UK Energy Statistics 2019, BEIS, July 2019

Table 2: Coal Authority extractive income as given in Coal Authority Annual Reports and Accounts

| Income (£000s) | 2010-11 | 2011-12 | 2012-13 | 2013-14 | 2014-15 | 2015-16 | 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Licensing and permissions indemnities of which: | 929 | 1,336 | 916 | 940 | 821 | 941 | 788 | 771 | 824 |

| Income from licensing | 675 | 1,083 | 616 | 547 | 351 | 432 | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Income from permissions indemnities | 254 | 253 | 300 | 393 | 470 | 509 | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Consolidated fund income (£000s) | 2010-11 | 2011-12 | 2012-13 | 2013-14 | 2014-15 | 2015-16 | 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Production related rent (gross) | 730 | 794 | 958 | 823 | 944 | 517 | 429 | 243 | 315 |

| (less) Cost of collection | (185) | (175) | (162) | (120) | (138) | (86) | (60) | (31) | (29) |

| = Production related rent (net) | 545 | 619 | 796 | 703 | 806 | 431 | 369 | 212 | 286 |

| Incidental coal (net of cost of collection) | 227 | (3) | 9 | 61 | 8 | 14 | 5 | 15 | 10 |

| Options for lease | 0 | 275 | 45 | 33 | 77 | 73 | 58 | 18 | 19 |

| Other coal mining income | 37 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Property sale proceeds | 0 | 100 | 75 | 0 | 4 | 32 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| Income payable to the consolidated fund | 809 | 991 | 925 | 797 | 895 | 550 | 432 | 245 | 322 |

| Balances held at start of year | 150 | 232 | 162 | 260 | 197 | 229 | 110 | 111 | 114 |

| Income payable to the consolidated fund | 809 | 991 | 925 | 797 | 895 | 550 | 432 | 245 | 322 |

| Payments made to the consolidated fund | (727) | (1,061) | (827) | (860) | (863) | (669) | (431) | (242) | (383) |

| Balances held at end of year | 232 | 162 | 260 | 197 | 229 | 110 | 111 | 114 | 53 |

The Coal Authority acts as an agent on behalf of the consolidated fund. Amounts collected and payable to the consolidated fund are reduced to cover the Coal Authority’s cost of collection. This income adjustment is included within Licensing and permissions indemnities income given above.

Production related rent is earned on each tonne of coal extracted from existing operating coal mining sites. Incidental coal is royalty income from other sites where coal production is incidental to the main purpose of the activity being carried out.

Options for lease for future coal mining sites are granted in the form of a conditional licence and option for lease for the coal and income is recognised on the granting of the option. The site cannot become operational until certain conditions (for example, planning consent) have been met and payments are made annually based on the area of the option.

Property sale proceeds are recognised within the consolidated fund income where the initial purchase was made from grant in aid in previous periods. Income is recognised following the exchange of contracts and on completion of the sale of property.

Cost of collection relates to the element of income retained to finance licensing activities and the cost of any unrecoverable amounts owed.

Balances held at end of year represent amounts still to be remitted to the consolidated fund.

Source: Coal Authority Annual Reports and Accounts

Construction minerals

Construction minerals include aggregates, brick clay and cement raw materials. The supply of aggregates includes crushed rock, sand and gravel (land-won and marine-dredged) with significant contributions from recycled and secondary materials. Brick clay is an essential raw material for the manufacture of bricks; limestone and chalk are the primary materials for the production of cement.

The aggregates industry produces crushed rock, sand and gravel. According to the Mineral Products Association, in 2018 the industry produced 180 million tonnes of primary aggregates (in addition to 72 million tonnes of recycled and secondary aggregates), 12.6 million tonnes of cementitious products and 1 million tonnes of dimension stone for construction uses in GB. In addition, 18 million tonnes of rock and 4 million tonnes of industrial sand for non-construction use in GB, and 5 million tonnes of clay, were extracted in 2014 for brick manufacture[footnote 16]. The British Geological Survey (BGS) does not record statistics on the value of production of construction minerals. Aggregates are the largest element of the supply chain of the construction industry, and fluctuations in construction have a large impact on demand and production. The market declined steeply following the 2008 economic crisis, but increased substantially between 2012 and 2016, with more modest growth between 2016 and 2018.There is evidence of a long-term decline in reserves of land-based sand and gravel, which could constrain supply if production continues to be greater than the approval of new reserves[footnote 17].

Most (66% of) UK primary aggregates production in 2017 took place in England, 14% in Scotland, 12% in Northern Ireland and 8% in Wales[footnote 18]. In 2017, 1,057 sq km (less than 0.1% of the total area of UK seabed) were licensed for dredging by TCE. The area dredged in the year, however, was significantly lower – 91 sq km, within which 90% of extraction effort (defined by hours dredged) occurred in an area of 38.3 sq km[footnote 19]. 81% of landings of marine dredged aggregates were made in London and the South East, reflecting the importance of marine aggregates to construction markets in these Regions.

The UK is a net exporter of aggregates, although both imports and exports represent less than 5% of UK markets. Because transport costs are a very significant factor for aggregates, most markets are local or regional, with relatively little international trade. Historically, the UK has been self-sufficient in the supply of primary aggregates due to significant geological resources and adequate reserves with planning permissions. Exports of UK aggregates were valued at £77.3 million in 2014, compared with imports worth £39.4 million[footnote 20].

Industrial minerals

Please note that final production figures for 2018 for industrial minerals are not yet available.

Industrial minerals include a number of raw materials used in specialised processes, with notable production in the UK of the following[footnote 21].

Kaolin

Kaolin, also known as china clay, is a commercial clay with specialist applications in paper production, ceramics, cosmetics and other industries. UK deposits of kaolin are concentrated in Cornwall and Devon and are world-class in terms of size and quality[footnote 22].

Production peaked in 1988 at 2.8 million tonnes but since then has declined to an estimated 970 thousand tonnes in 2017, 90% of which was exported, mostly to Europe.

Ball clay

Ball clay, another major industrial mineral, is produced in Devon and Dorset mainly for the manufacture of white ware ceramics. Production levels peaked between 2005 and 2008 at more than 1 million tonnes. In 2017, production was estimated at 850,000 tonnes.

Potash

Yorkshire has one of the largest proven world deposits of potassium-rich minerals. There is one potash mine in the UK, at Boulby, Yorkshire, and in June 2015 a planning application was approved for another mine in the North York Moors (NYM) National Park. 90% of potash mined in the UK is used for agricultural fertiliser production. Small quantities are also used in the pharmaceutical and chemical industries. Production of potash reached its record high of 1.04 million tonnes (refined potassium chloride) in 2003 but then declined. Current production (2017) is estimated to be 216 thousand tonnes[footnote 23].

The Boulby mine, which produces salt in conjunction with potash, directly employs about 1,000 people, half of whom work underground[footnote 24]. It has been reported that progress of the mine under development in the NYM National Park is under review[footnote 25].

Salt

England accounts for 95% of UK salt production, 80% of which takes place in Cheshire. The Boulby potash mine in Yorkshire is another large centre. About 70% of salt is extracted through solution mining, the rest mined as rock. County Antrim is the main area of salt production in Northern Ireland. Rock salt is primarily used for de-icing roads and in agriculture. Brine salt is chiefly used in chemical industrial processes that require chlorine. An estimated 4.50 million tonnes of salt were produced in the UK in 2017.

Silica sands

Silica sands contain a high proportion of silica and their properties make them essential for glass making and a wide range of other industrial and horticultural applications. UK production has declined from approaching 7 million tonnes in 1974 to an estimated 4.5 million tonnes in 2017.

Gypsum

Natural gypsum is used in plaster, plasterboard and cement making and has historically been mainly extracted by mining in the UK. The amount extracted in the UK has declined appreciably because of the use of desulphogypsum derived from flue gas desulphurisation at coal-fired power stations. In 2017 the UK produced an estimated 1.2 million tonnes.

Industrial and agricultural carbonates

These are important in iron and steel making, sugar refining and glass making, as fillers in various products, to reduce soil acidity in agriculture, and for flue gas desulphurisation in coal fired power generation. Total industrial carbonates production peaked at around 11.5 million tonnes in the late 1990s but was around 9 million tonnes in 2014.

Fluorspar

Fluorspar is the most important and only UK source of the element fluorine, most of which is used in the manufacture of hydrofluoric acid. It is extracted from the Southern Pennine ore field in the Peak District National Park. In 2017, an estimated 11,000 tonnes were extracted.

Barytes

Barytes is principally used as a weighting agent in drilling fluids used in hydrocarbon exploration, to which its fortunes have been linked. The major source comes from the Foss mine near Aberfeldy in Scotland. Production in 2017 was 50,000 tonnes.

The above data are sourced from the BGS World Mineral Production publication and cover extraction from 2012–2016.

Metal minerals

Tungsten (wolfram)

Tungsten is an essential element in a range of industrial processes, valued for its high melting point, density and extreme strength. England hosts the world’s fourth largest known tungsten deposit – the Drakelands Mine near Plympton, Devon. This has been estimated to contain 318,800 tonnes of tungsten metal, or about 10% of the world’s known reserves, as well as an estimated 43,700 tonnes of tin. Production at Drakelands, historically known as Hemerdon mine, began in 2015 after a 70-year break, operated by Australian company Wolf Minerals, but stopped in 2018 following the operating company going into administration[footnote 26].

Glossary of abbreviations

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| BEIS | Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy |

| BGS | British Geological Survey |

| BIS | Department for Business, Innovation and Skills |

| BMAPA | British Marine Aggregate Producers Association |

| CES | Crown Estate Scotland |

| CT | Corporation Tax |

| DAERA | Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs |

| DCLG | Department for Communities and Local Government |

| DfE | Department for the Economy |

| EU | European Union |

| HSE | Health and Safety Executive |

| HSENI | Health and Safety Executive for Northern Ireland |

| GB | Great Britain |

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product |

| GVA | Gross Value Added |

| LPA | Local Planning Authority |

| MEA | Mineral Extraction Allowance |

| MMO | Marine Management Organisation |

| MPA | Mineral Products Association / Mineral Planning Authority |

| MPL | Mineral Prospecting Licence |

| MSG | Multi Stakeholder Group |

| NIEA | Northern Ireland Environment Agency |

| NRW | Natural Resources Wales |

| NYM | North York Moors |

| ONS | Office for National Statistics |

| SEPA | Scottish Environment Protection Agency |

| TCE | The Crown Estate |

| UCG | Underground Coal Gasification |

| UK | United Kingdom |

-

British Geological Survey (BGS). United Kingdom Minerals Yearbook 2015, June 2016 ↩

-

For environmental issues that may be considered during the planning process, see DCLG, Assessing environmental impacts from minerals extraction ↩

-

The functions of the Department’s Strategic Planning Division Minerals Unit in Northern Ireland transferred to each of the 11 councils on 1 April 2015. Under the 2-tier planning system, councils are the determining planning authority for the vast majority of planning application, including mineral applications. Applications of regional significance are submitted directly to the Department of the Environment. However, from 2016, applications in respect of planning should be submitted to the Department of Infrastructure under the provision set out in section 26 of the Planning Act (Northern Ireland) 2011. ↩

-

For more information see DCLG, Minerals planning orders ↩

-

The Crown Estate is an incorporated public body that manages the monarch’s property portfolio. ↩

-

Marine planning in England

Marine planning in Wales

Marine planning in Scotland

Marine planning in Northern Ireland ↩ -

BGS Minerals UK, Legislation & policy: mineral ownership ↩

-

Contact details. Information about coal licences (including licensee details) can be viewed free of charge from the Coal Authority offices, but there is a charge if a copy is requested. Discussions are ongoing to set up an on-line electronic register. ↩

-

British Marine Aggregate Producers Association (BMAPA), Licensing and regulation; the Marine Management Organisation (MMO) is an executive non-departmental public body sponsored by the Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs ↩

-

England: MMO Public Register

Wales: Applications received and determined

Scotland: Marine licensing register

Northern Ireland: the functions and services delivered by Department of the Environment have been transferred to new Northern Ireland departments. A register of licensing information is available for inspection at all reasonable times by members of the public free of charge. Contact Marine Strategy and Licensing Branch or the Northern Ireland Environment Agency (NIEA), Marine Dredging. ↩ -

UK Environmental Law Association, Marine Licensing ↩

-

Royalty rates vary between licences and are commercially confidential. Companies also pay “dead rent”, a standard minimum annual fee payable to TCE if no dredging has occurred within the past 12 months. ↩

-

With an exception of a few places in Scotland, where mineral rights were transferred historically. ↩

-

ONS. UK environmental accounts 2018

ONS. UK environmental accounts: environmental taxes

HMRC guidance, Environmental taxes, reliefs and schemes for businesses

and, in particular, Excise Notice AGL1: Aggregates Levy ↩ -

Mineral Products Association, Profile of the Mineral Products Industry 2018 ↩

-

UK Minerals Forum, The future of our minerals: A summary report, November 2014 ↩

-

Mineral Products Association, The mineral products industry at a glance ↩

-

British Marine Aggregate Producers Association, Sustainable development report 2016. ↩

-

BIS, Monthly Bulletin of Building Materials and Components ↩

-

Sources of data in this sub-section include:

BGS, UK Minerals Yearbook 2015

BGS, Mineral Planning Factsheets

BGS, UK mineral statistics

UK Minerals Forum, Trends in UK Production of Minerals ↩ -

Company information. ↩

-

BBC. Sirius minerals ↩

-

BBC. Wolf Minerals miners’ jobs at risk as it stops trading ↩