Youth Justice Statistics: 2020 to 2021 (accessible version)

Published 27 January 2022

Applies to England and Wales

We are trialling the publication of this statistical bulletin in HTML format alongside the usual PDF version and we are seeking user feedback on the use of HTML for the publication of statistical bulletins. Please send any feedback to: informationandanalysis@yjb.gov.uk.

The youth justice system in England and Wales works to prevent offending and reoffending by children. The youth justice system is different to the adult system and is structured to address the needs of children.

This publication looks at the youth justice system in England and Wales for the year ending March 2021. It considers the number of children (those aged 10-17) in the system, the offences they committed, the outcomes they received, their demographics and the trends over time.

Some of the reductions or increases to these figures in the year ending March 2021 are likely to be due to impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. We have added a separate section following the main points which highlight these.

Main points

| 15,800 children were cautioned or sentenced | ↓ | The number of children who received a caution or sentence has fallen by 17% in the last year with an 82% decrease over the last ten years. |

| 8,800 first time entrants to the youth justice system | ↓ | The number of first time entrants has fallen by 20% since the previous year, with an 81% fall from the year ending March 2011. |

| 3,500 proven knife and offensive weapon offences were committed by children | ↓ | There was a 21% decrease in these offences compared with the previous year. Levels are 14% lower than those seen in the year ending March 2011. |

| Almost three quarters of children remanded to custody received a non-custodial outcome | ↑ | There was an 8 percentage point increase compared with the previous year in outcomes which did not result in a custodial sentence. Of the outcomes which did not result in a custodial sentence, half resulted in a non-custodial sentence and half resulted in acquittal. |

| The average time from offence to completion at court increased | ↑ | The average time from offence to completion was 219 days, compared with 172 days in the previous year. |

| The number of children in custody has fallen to its lowest level | ↓ | There was an average of 560 children in custody at any one time during the year. This is a fall of 28% against the previous year. |

| All custodial Behaviour Management measures saw decreases in rates | ↓ | Compared with the previous year, rates of assaults decreased by 26%, Restrictive Physical Interventions by 24%, self harm by 23% and separation by 3%. |

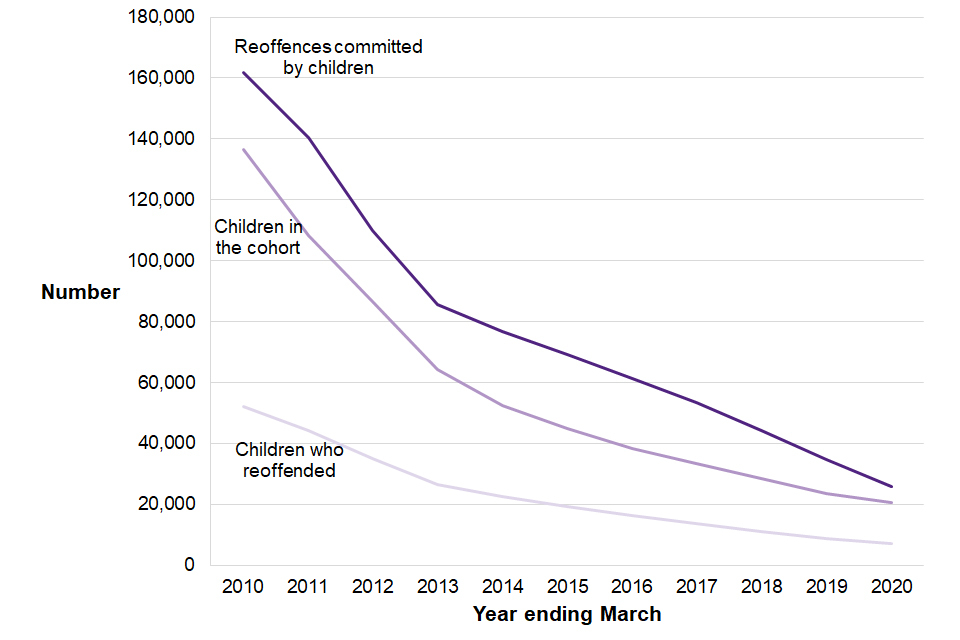

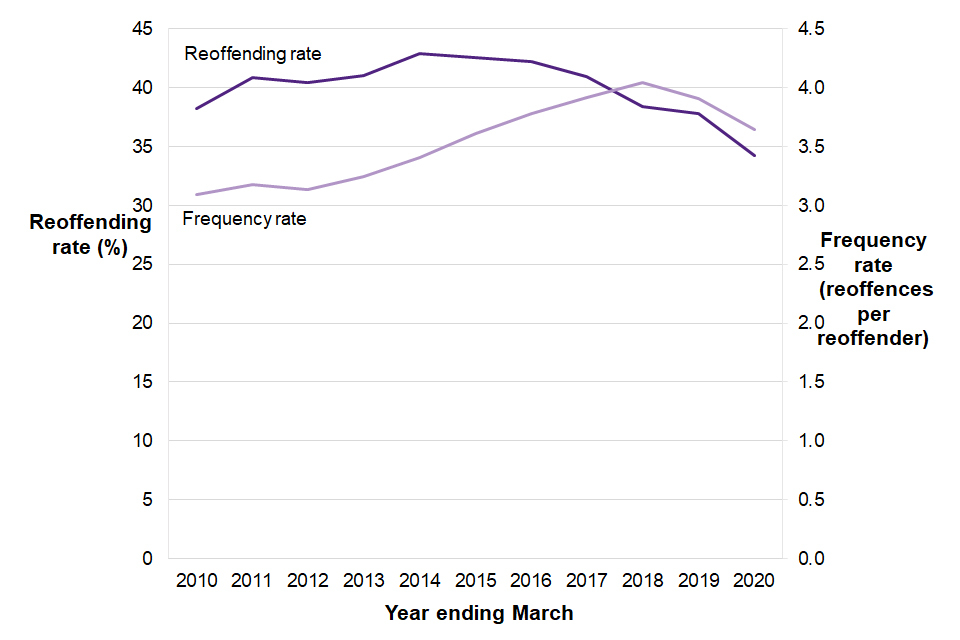

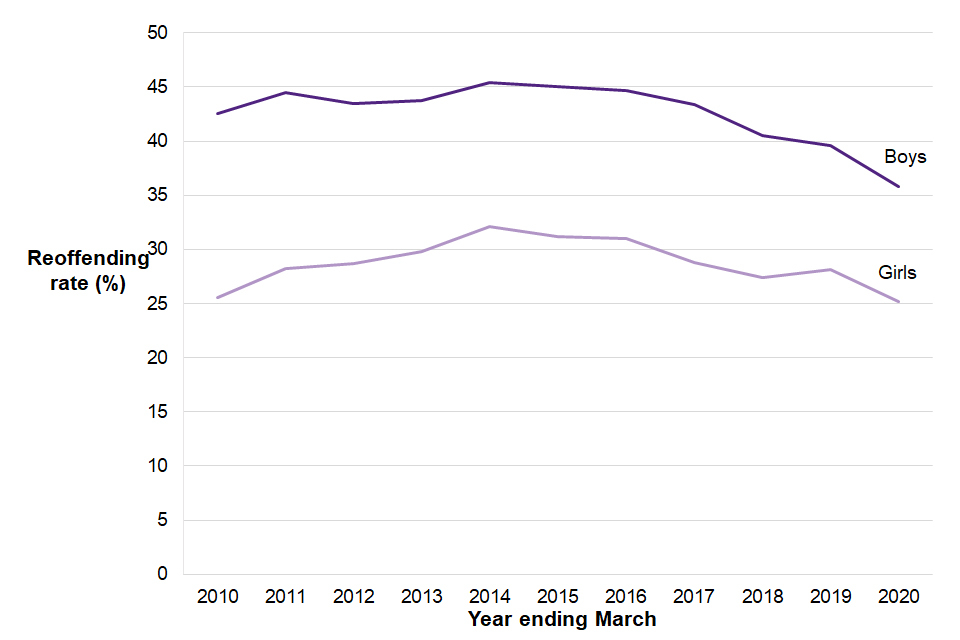

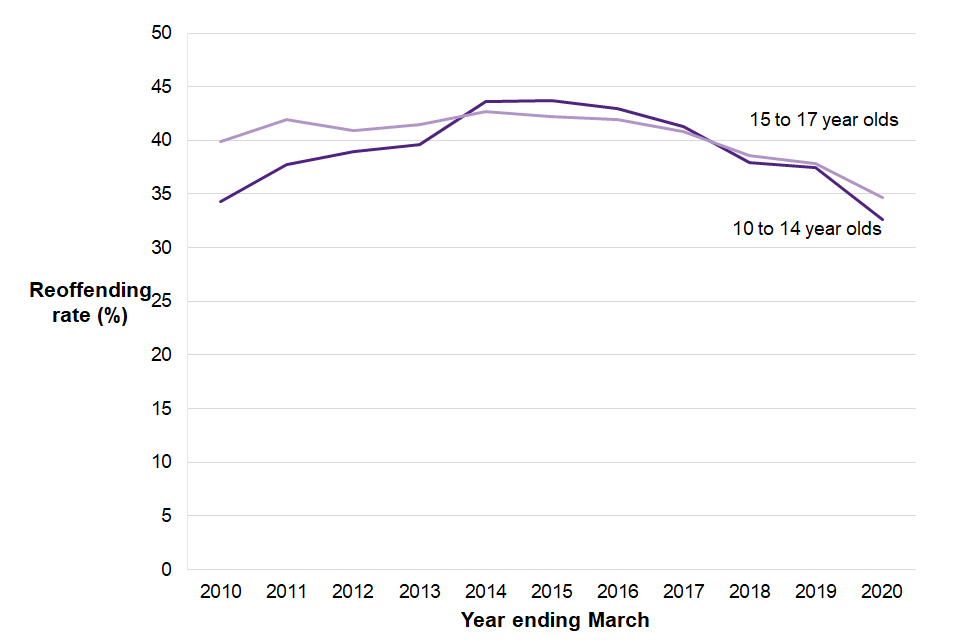

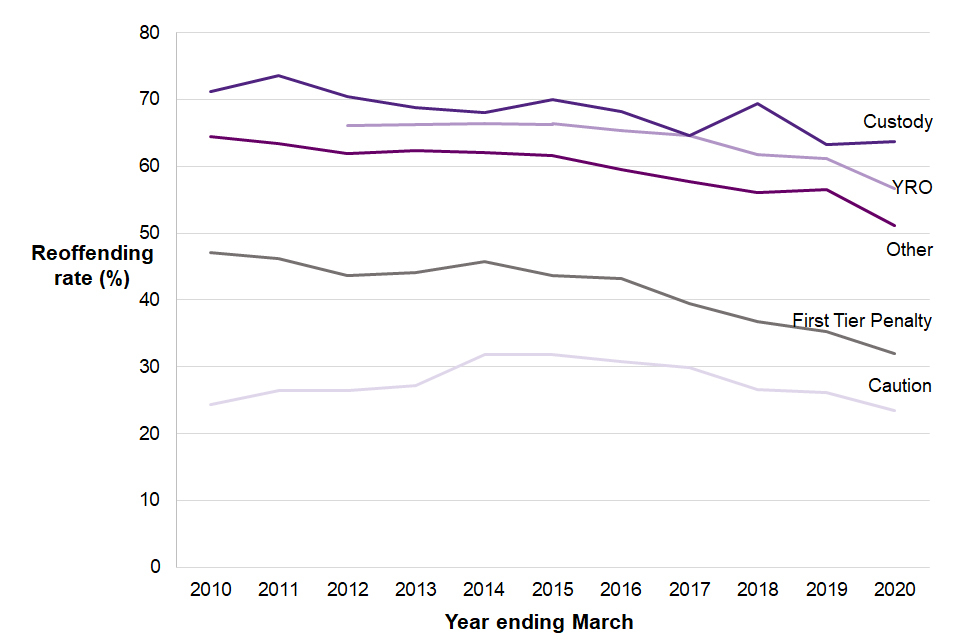

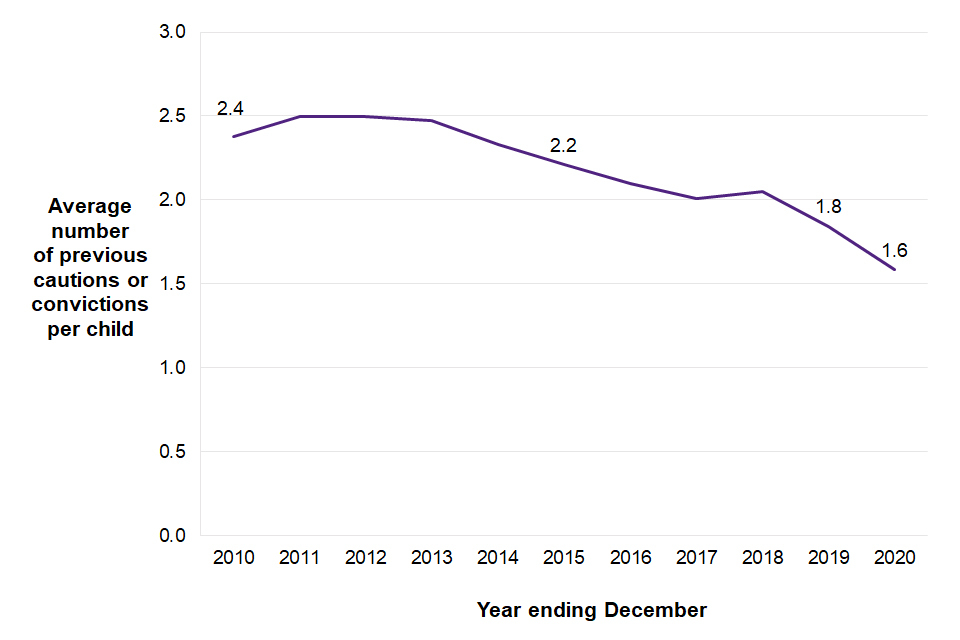

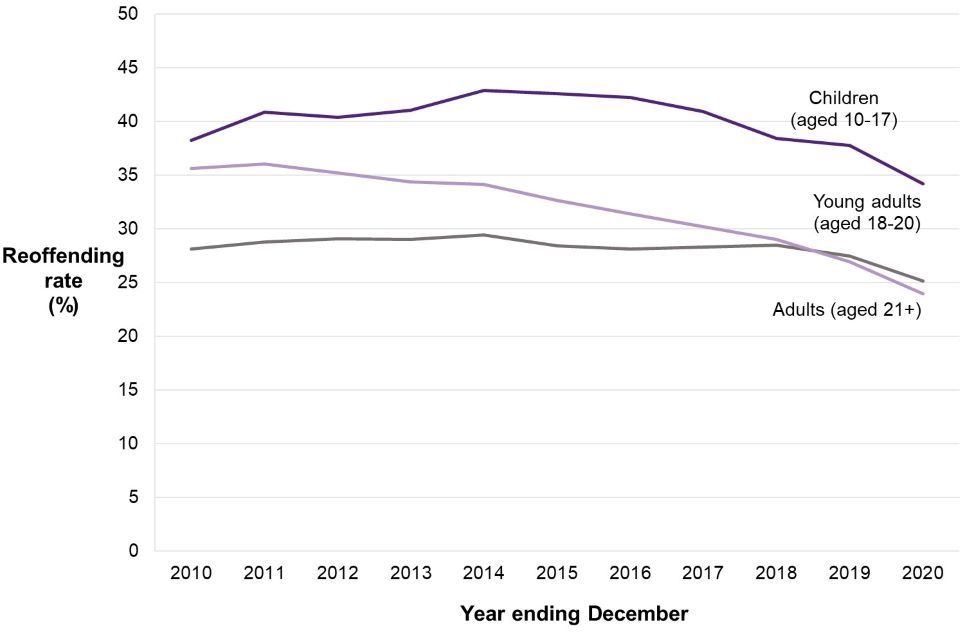

| Reoffending decreased to its lowest level | ↓ | The reoffending rate decreased by 3.6 percentage points in the last year and 4.1 percentage points from the year ending March 2010. This was the sixth consecutive year on year fall. |

For technical details see the accompanying Guide to Youth Justice Statistics

We would welcome any feedback to informationandanalysis@yjb.gov.uk

Likely impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the youth justice system

The likely impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the youth justice system can be seen in several areas within this publication. Periods of restrictions including court closures, pauses to jury trials, court backlogs, home schooling for many children, changes to people’s behaviour including reduced social contact and changes to custodial regimes are all likely to have contributed to changes in rates and numbers in several key areas.

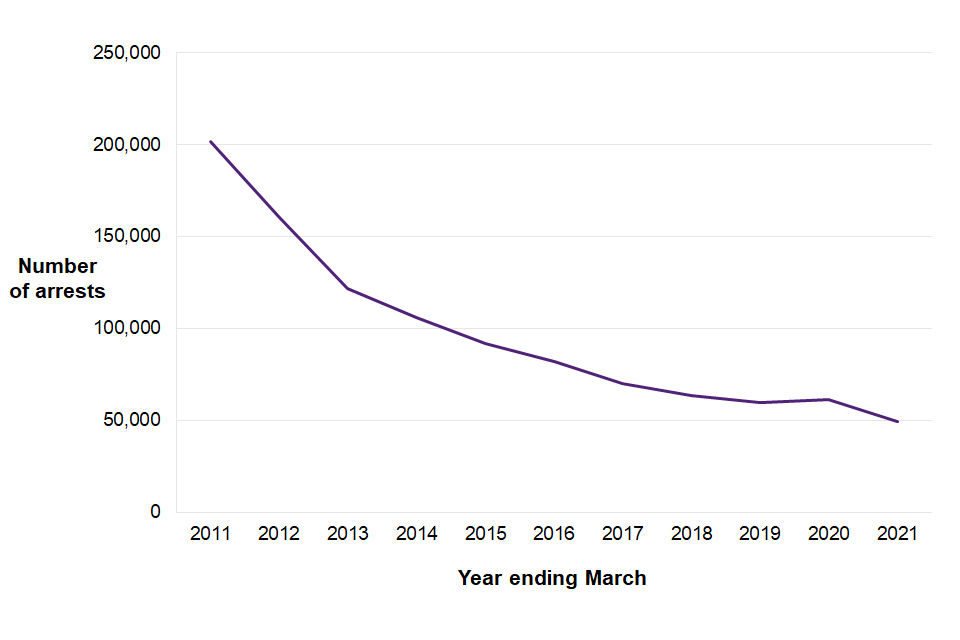

| Arrests at lowest level since the time series began | ↓ | This large decrease, the biggest in eight years is likely to be driven in part by the COVID-19 pandemic; with many children being home schooled for large parts of the year, as well as changes to people’s behaviour and a reduction in police recorded crime. |

| The proportion of younger children cautioned or sentenced was at the lowest level since the time series began | ↓ | This fall for the younger age group could, in part, be due to many children being home schooled for long periods of the year as well as a reduction in police recorded crime. |

| The number of children held in custody has fallen to its lowest level | ↓ | This was the biggest year on year percentage decrease since the time series began 20 years ago. It is likely due in part to fewer children being sentenced to custody during periods of restrictions when jury trials were paused, alongside a large decrease in offending by children compared with the previous year. |

| The proportion of children on remand and length of time on remand increased | ↑ | Children on remand made up the highest proportion of the custodial population for the first time. Children spent an average of over two weeks longer on remand than the previous year. This is likely due to limits on court activity, including pauses to jury trials and the subsequent backlog of cases. |

| The average time from offence to completion at court increased | ↑ | The average time from offence to completion was almost seven weeks longer than the previous year, which is likely due to limits on court activity, including pauses to jury trials and the subsequent backlog of cases. |

| Behaviour Management rates in custody down | ↓ | Changes to custodial regimes, including longer time in rooms and staff shortages are likely factors in reductions in rates across the four behaviour management measures. |

| Reoffending rate at lowest level on record | ↓ | The reoffending rate saw a much larger decrease than in previous years with court closures, pauses to jury trials, increases in time from offence to completion, as well as actual decreases in offending all likely factors. |

Things you need to know

This publication draws together a range of statistics about children in the youth justice system from 1 April 2020 to 31 March 2021 (hereafter the year ending March 2021), where available.

The Information and Analysis Team at the Youth Justice Board (YJB) produce this report. The data described in this publication come from various sources including the Home Office, the Ministry of Justice (MoJ), the Youth Custody Service (YCS), local Youth Justice Services (YJSs) and youth secure estate providers.

Details of all the administrative databases and bespoke collections used for this report can be found in the Guide to Youth Justice Statistics which provides users with further information on the data sources, data quality and terminology, in particular the types of disposals given to children.

This is an annual report, with the focus on the year ending March 2021, however much of the data used in this report are drawn from quarterly publications and there may be more up to date data available. The purpose of this report is to provide an overall summary of the system, allowing users to find everything in one place. All data referenced are available in the Supplementary Tables that accompany this report. Separate tables covering Youth Justice Service level information are also available, including in an open and accessible format.

In this years’ publication, data on trends around Youth Cautions in the Gateway to the youth justice system chapter are not available as MoJ analysts had limited access to Police National Computer terminals due to COVID-19 restrictions. Data on stop and searches are available at age group level for the first time, though this is for the latest year only. Data on criminal histories are only available for calendar year and not financial year.

Within this publication the words ‘child’ or ‘children’ are used to describe those aged 10 to 17. When the terms ‘child or young adult’ or ‘children and young adults’ are used, it means that 18 year olds may be included in the data.

The term Youth Justice Services has replaced the term Youth Offending Teams. The statutory definition of a local youth justice service is contained in the Crime and Disorder Act 1998. In statute these are known as Youth Offending Teams. However, as services have evolved, they have become known by different names. For this reason, we now prefer to use the term Youth Justice Services (YJSs).

Rounding conventions have been adopted in this publication to aid interpretation and comparisons. Figures greater than 1,000 have been rounded to the nearest 100 and those smaller than 1,000 to the nearest 10. Rates have been reported to one decimal place. Percentages have been calculated from unrounded figures and then rounded to the nearest whole percentage. Unrounded figures have been presented in the Supplementary Tables.

The data in this report are compared with the previous year (the year ending March 2020 in most cases), with the year ending March 2011 as a long-term comparator (ten years). Where a ten year comparator is not available, the year ending March 2016 has been used (five year comparator). Any other reference period is referred to explicitly.

Statistician’s comment

This report draws together a range of statistics about children in the youth justice system. The latest figures highlight a full year’s impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the system.

It is difficult to quantify the exact effects of the pandemic on the system, though it’s clear that measures taken during the periods of restrictions, such as court closures, pauses to jury trials and remote hearings along with the subsequent backlog of cases have had an effect on the number of sentences and time spent on custodial remand. Changes to people’s behaviour, including reduced social contact may have had an effect on the number of proven offences and type of offences committed. Changes to custodial regimes during the periods of restrictions, including less time out of rooms are likely to have affected behaviour management incident rates.

It is important to note that in addition to the impacts of the pandemic, there have been downward trends in many areas in recent years. For example, the long-term falls in the number of First Time Entrants (FTEs) to the youth justice system and the number of children receiving a youth caution or court sentence have continued, while the number of children in custody was at a record low in the latest year. The proportion of children who reoffend, while decreasing, remains higher than that for young adults or adults.

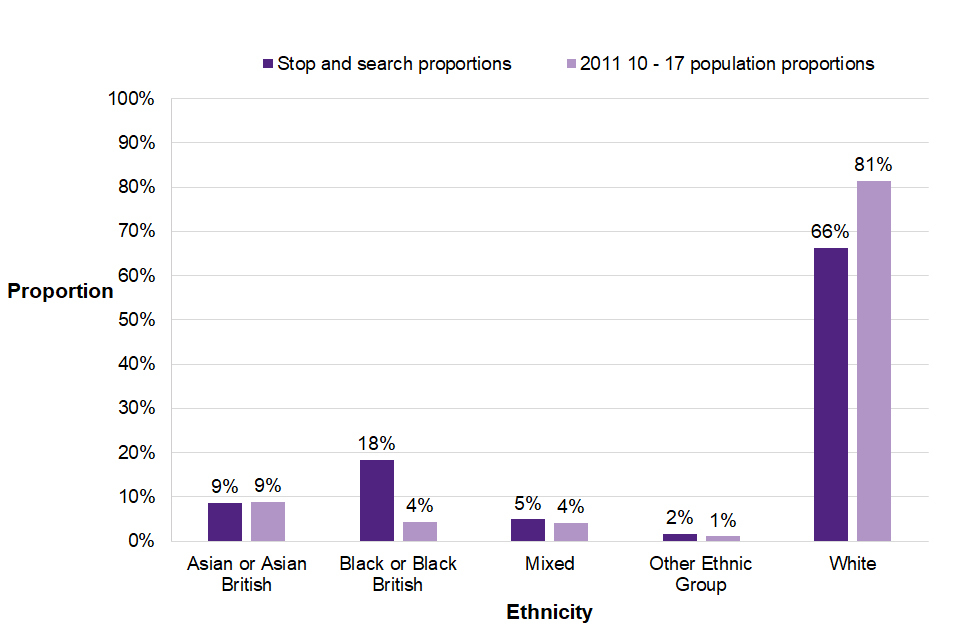

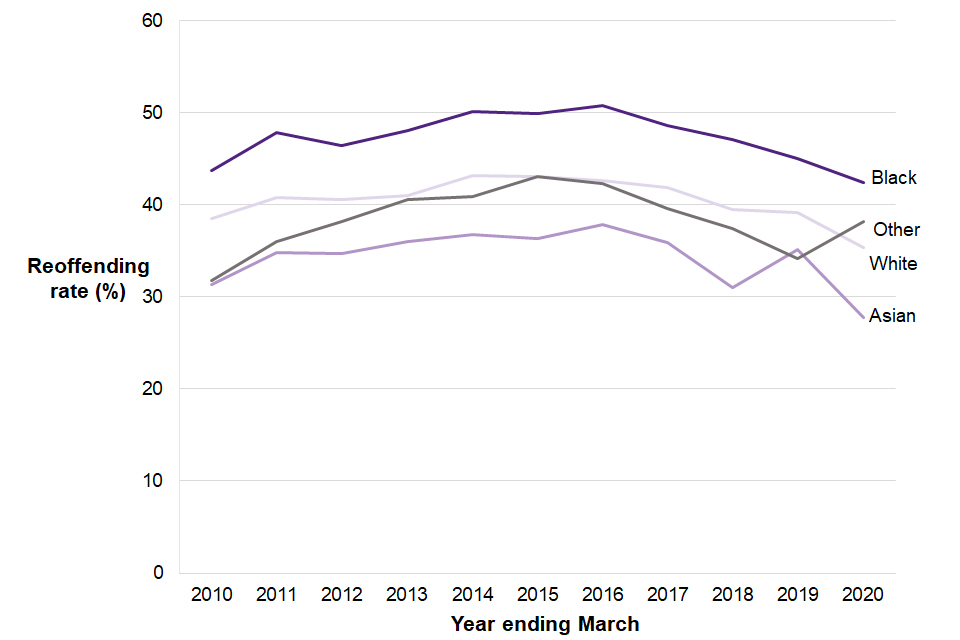

For the first time, stop and search data for 10 to 17 year olds is available. It showed that Black children were more likely to be stopped than other ethnicities. It also shows that four out of five stop and searches, across all ethnicities, resulted in no further action.

Ethnic disproportionality is seen at many other stages of the youth justice system. While the number of FTEs from a Black background has decreased compared with ten years ago, the proportion they comprise of all child FTEs (where ethnicity was known), has increased, from 10% to 18%. The proportion of children in custody who are Black is up to 29% from 18% ten years ago.

Proven reoffending rates have reduced to the lowest on record. While there has been a downward trend in recent years, the large reduction in the latest year is likely to have been impacted by the impacts of court closures and pauses to jury trials during the periods of restrictions.

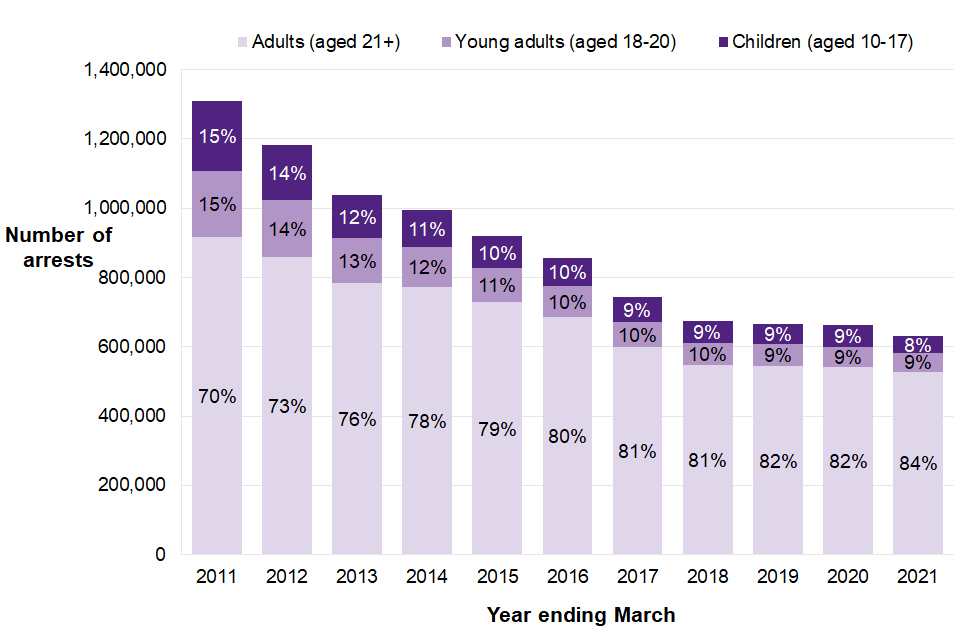

1. Gateway to the youth justice system

In the year ending March 2021:

-

Black children were involved in 18% of stop and searches (where ethnicity was known). This was 3 percentage points higher than the proportion of children arrested who were Black and 14 percentage points higher than the proportion of Black 10 to 17-year-olds in the 2011 population.

-

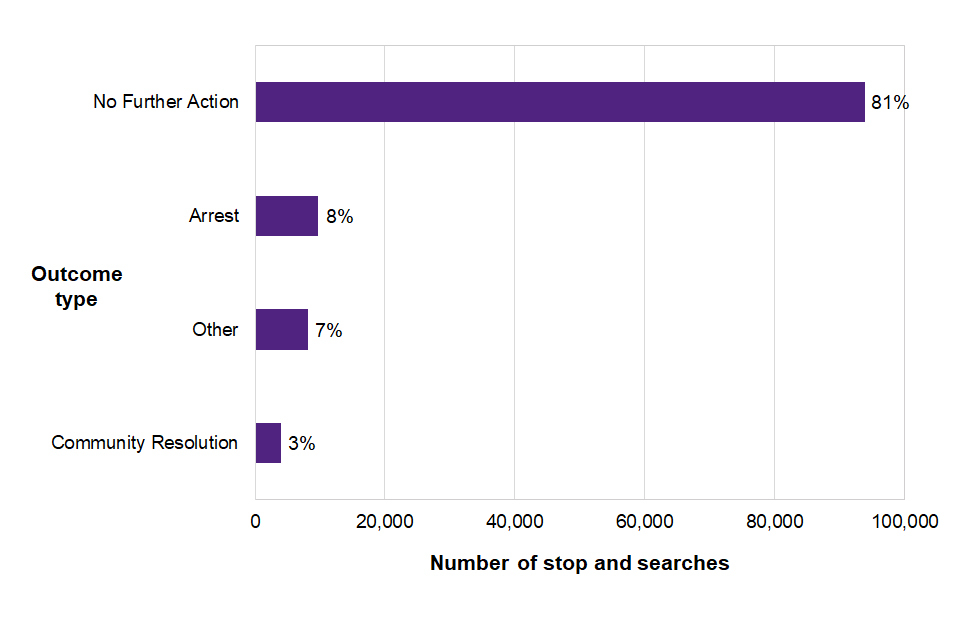

The majority (81%) of stop and searches of 10 to 17-year-olds resulted in No Further Action, while 8% resulted in arrest.

-

Arrests of children decreased by 19% compared to the previous year to around 49,500[footnote 1], the lowest level since the time series began and likely driven in part due to the lockdown measures during the COVID-19 pandemic.

This chapter covers data on stop and searches of children and arrests of children. Data on youth cautions for the year ending March 2021 are not available so have not been included.

1.1 Stop and searches of children aged 10-17

Figure 1.1: Number of stop and searches of children by ethnicity as a proportion of total where ethnicity is known[footnote 2], England and Wales, year ending March 2021

Stop and searches of children by ethnicity as a proportion

For the first time, stop and search data are available for children. There were around 115,600 stop and searches of children in the year ending March 2021. Black children were involved in 18% of stop and searches (where ethnicity was known). This was 14 percentage points higher than the proportion of Black 10 to 17-year-olds in the 2011 population.

Around 113,800 (98%) stop and searches were carried out under Section 1 of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act (PACE) 1984 which provides police with the power to stop and search a person or vehicle where they have reasonable grounds that they will find prohibited items including offensive weapons or drugs.

The remaining 1,800 (2%) of stop and searches were carried out under section 60 of the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act of 1994, which gives police the right to search people in a defined area during a specific time period after serious violence has taken place or when police believe that serious violence will take place.

Figure 1.2: Number and proportion of stop and searches by outcome type, England and Wales, year ending March 2021

Proportion of stop and searches by outcome type

As figure 1.2 shows, the majority (around 93,800 or 81%) of stop and searches of 10-17 year olds resulted in No Further Action, while around 9,800 (8%) resulted in arrest, 3,900 (3%) resulted in Community Resolutions and the remaining 8,100 (7%) resulting in other outcomes including Cannabis Warnings, Seizure of Property or Verbal Warnings.

1.2 Arrests of children for notifiable offences

Figure 1.3: Trends in arrests of children for notifiable offences, England and Wales, years ending March 2011 to 2021

Arrests of children for notifiable offences

In the latest year, there were just over 49,500 arrests of children (aged 10-17) for notifiable offences. This was a decrease of 19% compared to the previous year and the lowest number of arrests of children since the time series began. This large decrease, the biggest in eight years is likely to be driven in part by the periods of restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic.

1.3 Arrests of children by offence group

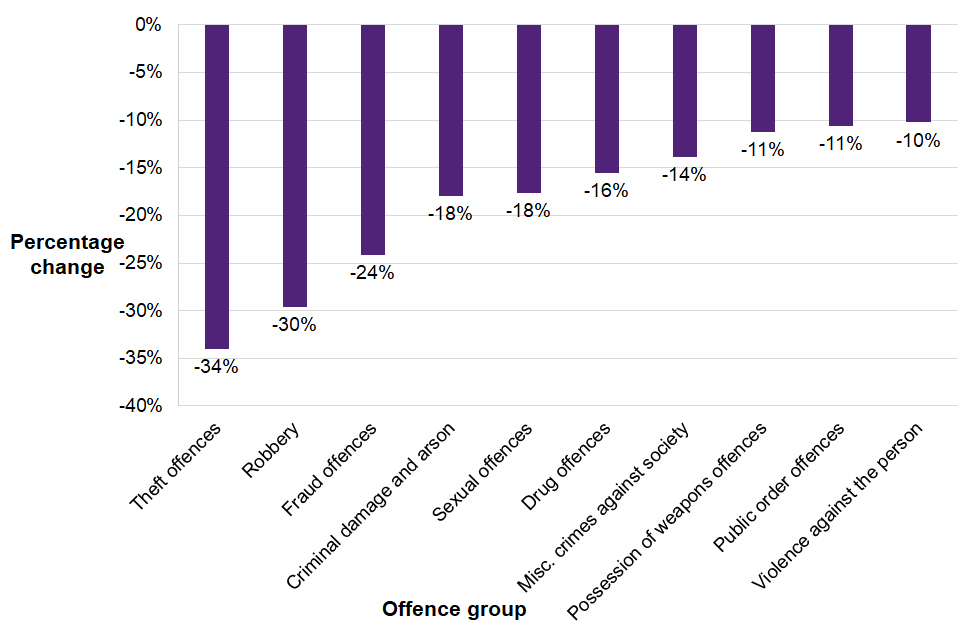

Figure 1.4: Percentage change in arrests by offence group, England and Wales, years ending March 2020 to 2021

Percentage change in arrests by offence group

Figure 1.4 shows the year on year percentage change in the number of arrests by offence group. Acquisitive crimes (Theft and Robbery) saw the biggest decreases, which is likely to be in part driven by changes to people’s behaviour, including reduced social contact and other measures during the periods of restrictions and beyond during the COVID-19 pandemic in the year ending March 2021.

1.4 Arrests of children by ethnicity

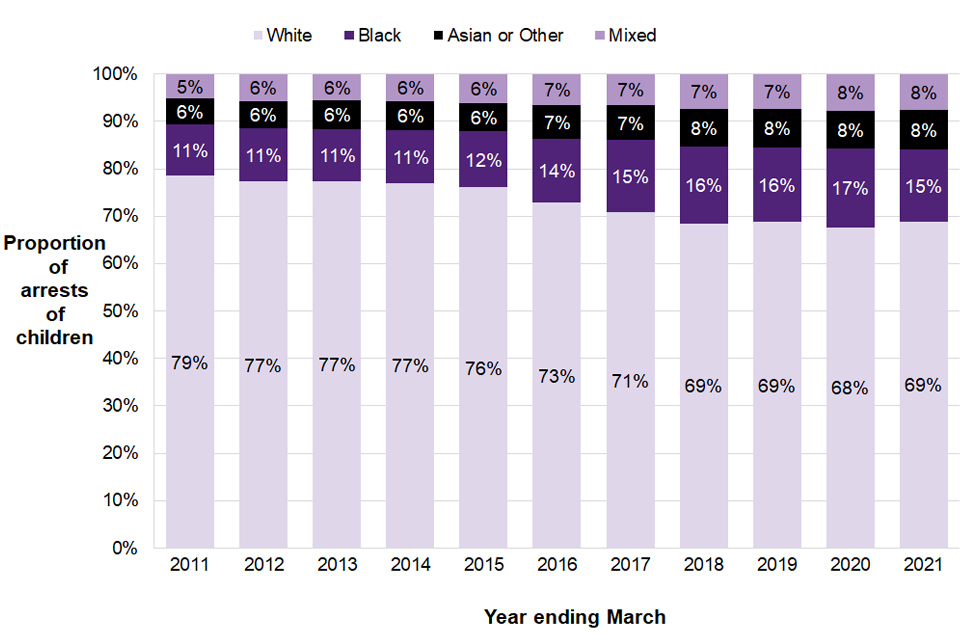

Figure 1.5: Arrests of children for notifiable offences by ethnicity as a proportion of total arrests of children, England and Wales, years ending March 2011 to 2021

Proportion of arrests of children for notifiable offences

Compared with the year ending March 2011, the numbers of arrests of children of each ethnicity have all decreased by a large degree, but at different rates. For example, arrests of White children have fallen by 81% compared to 69% for Black children. This has led to a change in the proportions of arrests by ethnicity.

In the latest year, 69% (around 30,100) of arrests were of White children. This proportion is a decrease from 79% in the year ending March 2011. Arrests of Black children accounted for 15% (around 6,700) in the latest year, four percentage points higher than the proportion of ten years ago. Arrests of Mixed (around 3,300) and Asian and Other (just over 3,600) children both made up 8% of the total in the latest year and have also seen changes in proportions over the last ten years, albeit on a smaller scale.

2. First time entrants to the youth justice system

In the year ending March 2021:

-

There were around 8,800 child first time entrants (FTEs) to the youth justice system. The number of FTEs has continued to fall, with a 20% decrease since the previous year, the biggest year on year decrease in eight years, though this is likely in part due to the impacts of restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic.

-

While there were minor increases for FTEs committing Robbery and Miscellaneous Crimes Against Society compared with the previous year (rising by 3% and 7% respectively), all other offence types committed by FTEs decreased, with Theft and Summary Offences Excluding Motoring seeing the biggest decreases (falling by 38% and 33% respectively).

-

While the number of FTEs from a Black background has decreased since the year ending March 2011, the proportion[footnote 3] they comprise of all child FTEs has increased, from 10% to 18%.

This chapter covers data and trends on trends, demographics, offence and outcome types of child first time entrants. A first time entrant to the youth justice system is a child aged between 10 and 17 who received their first caution or court sentence.

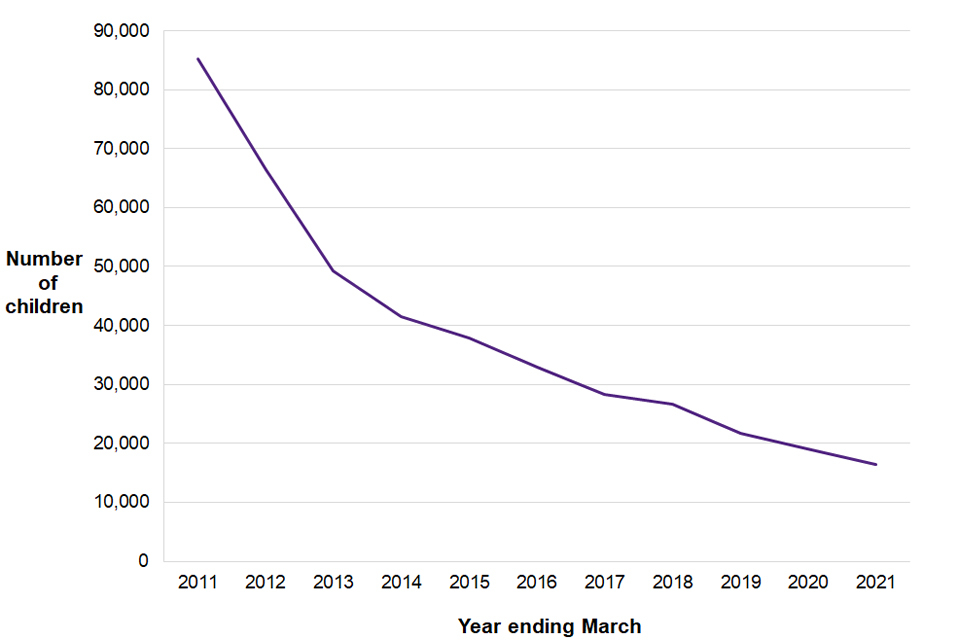

2.1 Trends in the number and proportion of child first time entrants to the youth justice system

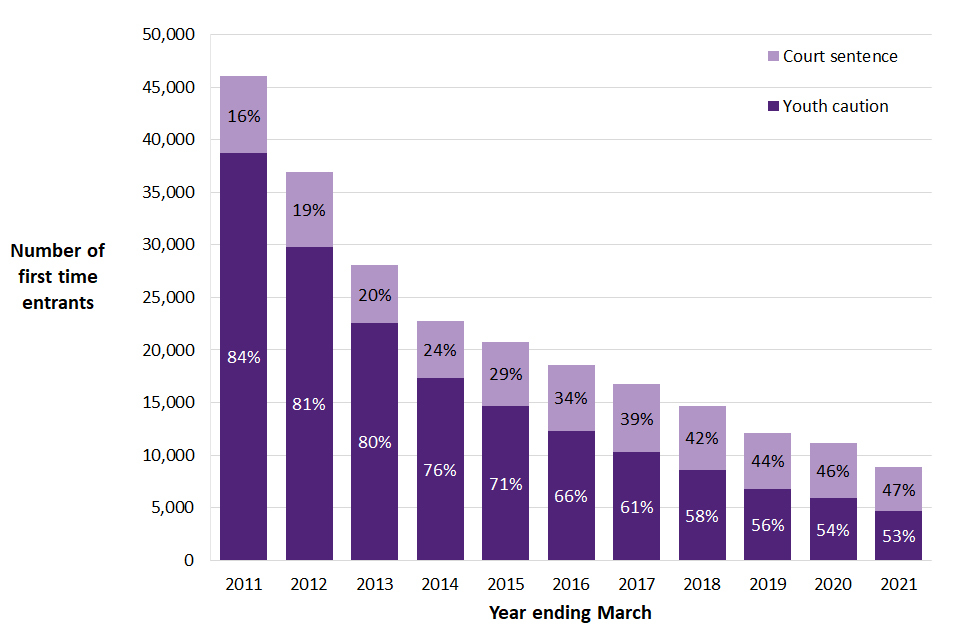

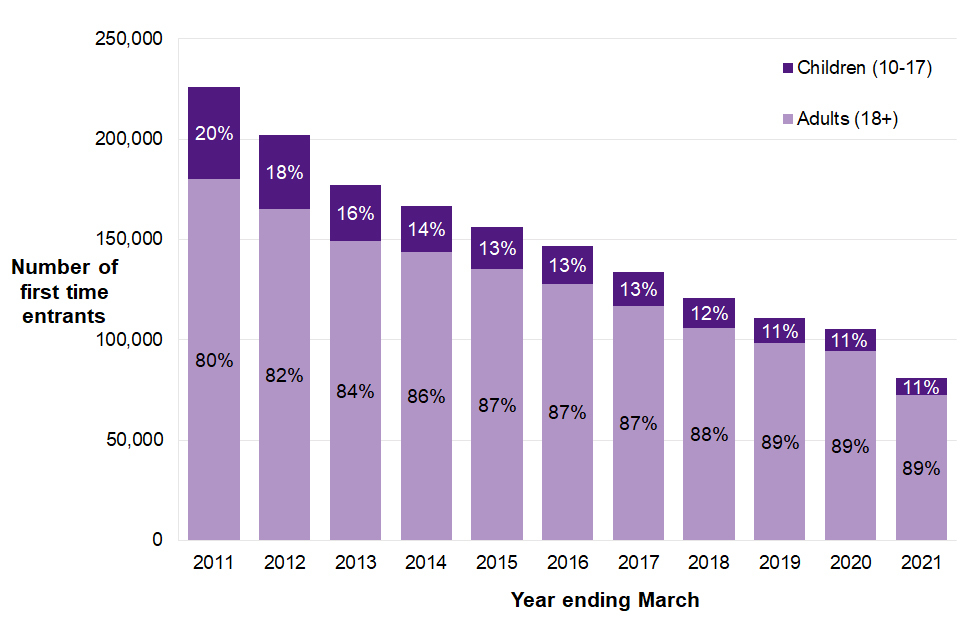

Figure 2.1: Child first time entrants, England and Wales, years ending March 2011 to 2021

Number and proportion of child first time entrants

The number of child FTEs (aged 10-17) has continued to fall. Compared with the previous year, the number fell by 20% (from 11,100) to around 8,800, the biggest year on year decrease in eight years, though this is likely in part due to the impacts of restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Compared with the year ending March 2011, the number has fallen by 81% (from around 46,000).

As shown in Figure 2.1, the difference between the number of FTEs to the youth justice system receiving a caution as opposed to a court sentence is much smaller in recent years than compared with ten years ago. While the majority of FTEs received a caution in each of the last ten years, this proportion has fallen from 84% in the year ending March 2011 (when around 38,700 FTEs received a caution), to 53% in the year ending March 2021 (when around 4,600 FTEs received a caution).

The number of FTEs receiving a court sentence (predominantly community sentences) had been falling year-on-year from the year ending March 2011 to March 2015, when it increased, before falling again from 2018. Since the year ending March 2011, the proportion of FTEs receiving a sentence has increased from 16% to 47% (Supplementary Table 2.4).

2.2 Characteristics of child first time entrants

Figure 2.2: Demographic characteristics[footnote 4] of child first time entrants compared to the general 10-17 population, England and Wales, year ending March 2021

| Aged 10-14 | Aged 15-17 | Boys | Girls | |

| FTEs | 24% | 76% | 85% | 15% |

| 10-17 population | 65% | 35% | 51% | 49% |

Age

The proportion of 10 to 14-year-old FTEs fell by five percentage points compared with the previous year. This may be due to the impacts of the periods of restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic, where many children were being home schooled, which meant they were being supervised by their parents or carers and there was less opportunity for offences to be committed.

The average age of FTEs has increased slightly compared with ten years ago. It increased from 15.0 years old in the year ending March 2011 to 15.5 in the latest year. Over the last ten years, the average age of FTEs receiving a sentence has always been higher than the average age of those receiving a youth caution (Supplementary Table 2.8).

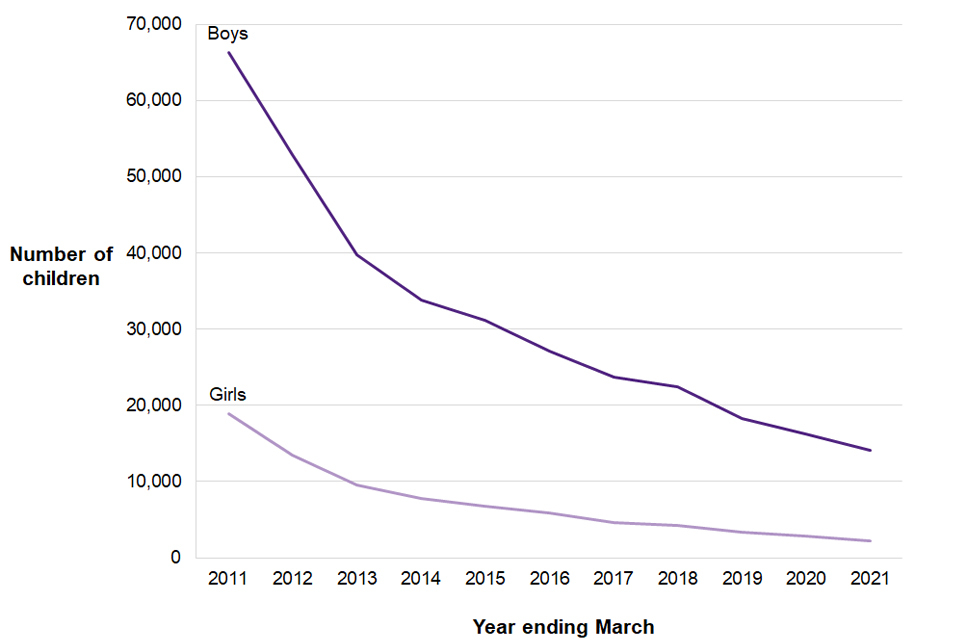

Sex

There have always been more boys than girls who are FTEs. In the year ending March 2021, boys comprised 85% of the total FTEs, whilst making up 51% of the general 10 to 17-year-old population.

The number of FTEs has fallen for both boys and girls over the last decade, with the larger percentage decrease seen in girls. The number of FTEs who are girls has fallen by 90% (from around 12,900 to around 1,300) over the last ten years. This compares to a decrease of 77% for FTEs who are boys over the same period (from around 32,900 to around 7,400). In the latest year, there was a 33% fall in FTEs who are girls compared to an 18% decrease in boys (Supplementary Table 2.6).

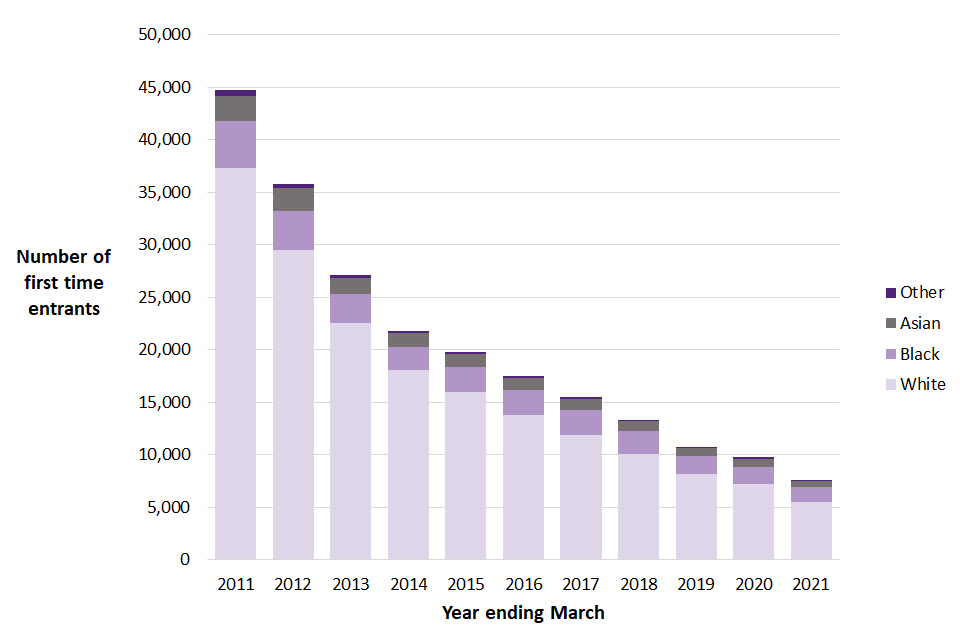

Figure 2.3: Number of child first time entrants by ethnicity, England and Wales, years ending March 2011 to 2021

Number of first time entrants by ethnicity

Ethnicity

As shown in Figure 2.3, the number of child FTEs has been falling for each ethnicity over the last ten years (except for FTEs from a Black ethnic background in which there was a small increase between the years ending March 2016 and March 2017). FTEs from a White ethnic background have fallen at the fastest rate, by 85% over the last ten years, resulting in the proportion they comprise of all FTEs reducing from 83% to 73%.

The proportion of FTEs from a Black background has increased over the last ten years, from 10% to 18%. The proportion of FTEs from an Asian background has increased from 5% to 8% over the same period and the proportion of FTEs from an Other ethnic background has increased slightly from 1% to 2%.

2.3 Types of offences committed by child first time entrants

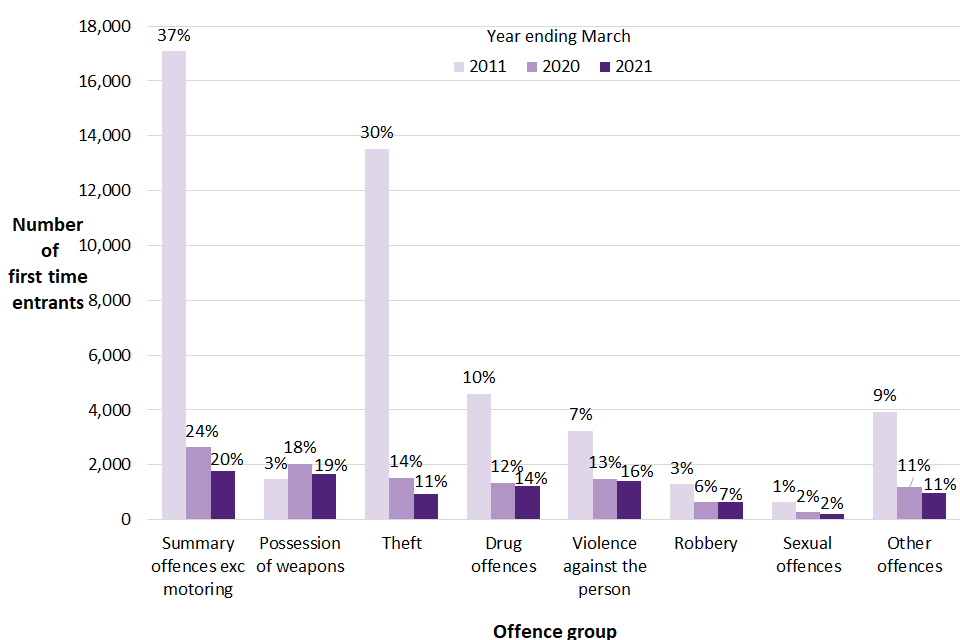

In the year ending March 2021, the most common offences committed by 10 to 17-year-old FTEs were summary offences excluding motoring. This offence type made up one fifth (around 1,800) of all offences committed by FTEs and includes lower level offences such as common assault and low-level criminal damage. Possession of weapon offences were the next most common and made up 19% of all offences committed by FTEs, a proportion which has been increasing over the last ten years. Compared with the year ending March 2011, the proportion of theft offences fell from 29% to 11%.

The proportion of FTEs committing possession of weapon offences has increased by 16 percentage points over the last ten years and is the only offence group to see a real term increase in that period.

Figure 2.4: Number of offences committed by child first time entrants by offence group, England and Wales, years ending March 2011 to 2021

Number of offences committed by first time entrants by offence group

Supplementary Table 2.2 shows that in the year ending March 2021, with the exception of robbery offences, there were fewer offences committed by child FTEs for all offence groups compared with the previous year.

Compared with ten years ago, child FTEs across all offence groups have fallen, with the exception of possession of weapons offences. There have been some significant changes in the proportions across offence groups over the decade.

The offence groups that have seen percentage point increases compared with ten years ago are:

-

Possession of weapons offences, increasing by 16 percentage points, to 19%;

-

Violence against the person, increasing by nine percentage points to 16%;

-

Drug offences and robbery both increasing by four percentage points to 14% and 7% respectively;

-

Summary motoring offences, increasing by two percentage points to 3%; and

-

Sexual offences, increasing by one percentage point to 2%.

The offence groups that have seen the largest percentage point decreases compared with ten years ago are:

-

Theft offences, decreasing by 19 percentage points to 11%;

-

Summary offences excluding motoring, decreasing 17 percentage points to 20%; and

-

Criminal damage and arson decreased by one percentage point to 2%.

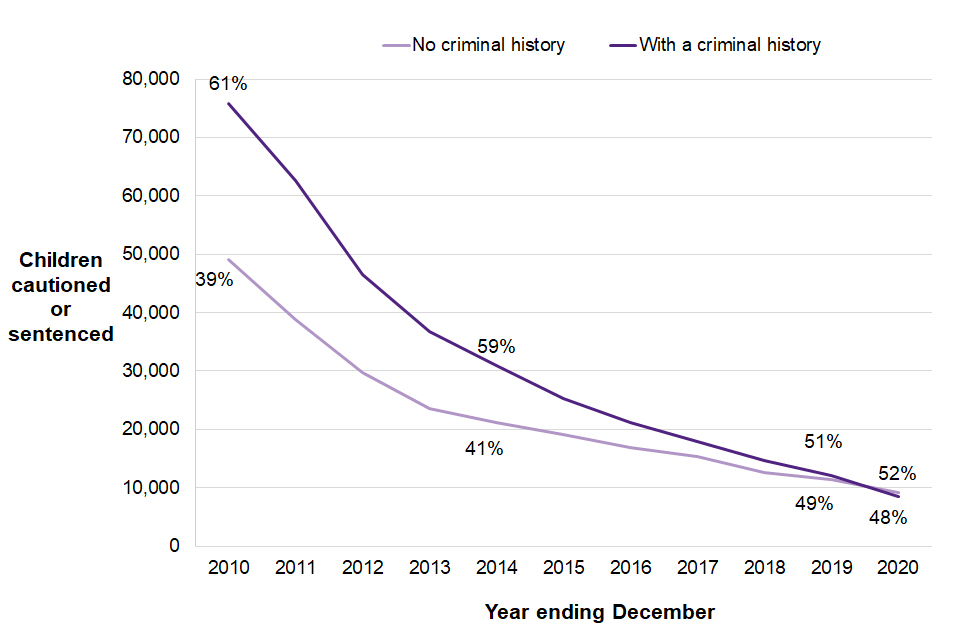

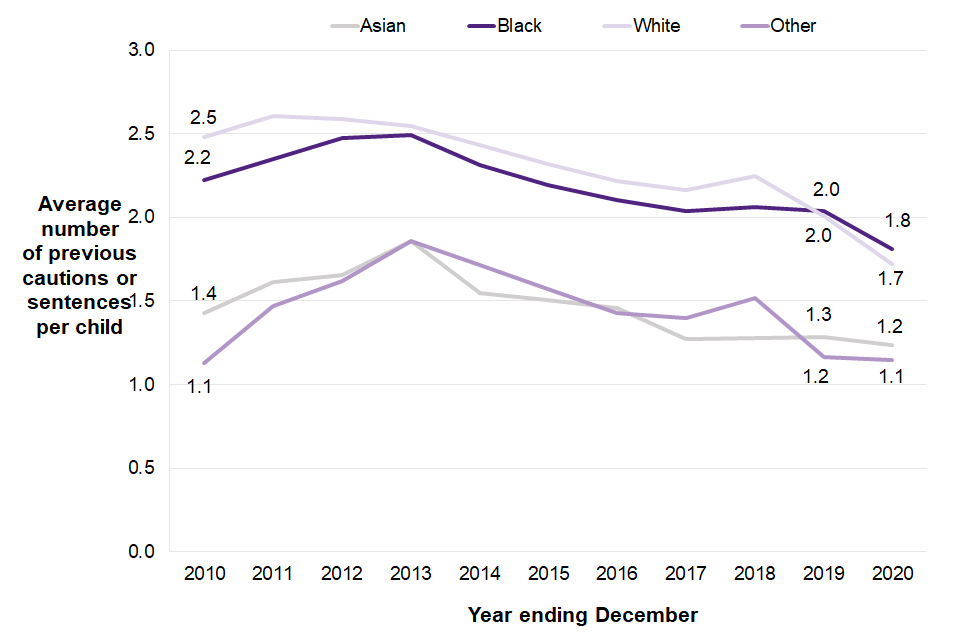

3. Demographic characteristics of children cautioned or sentenced

In the year ending March 2021:

-

Around 15,800 children received a caution or sentence, a fall of 17% compared with the previous year and a fall of 82% compared to ten years ago.

-

The proportion of children cautioned or sentenced who are Black has been increasing over the last ten years and is five percentage points higher than it was in the year ending March 2011 (12% compared to 7%).

-

The number of 10 to 14-year-olds cautioned or sentenced decreased by 34% compared with the previous year, while there was a 12% decrease for 15 to 17-year-olds. This fall for the younger age group may be due to many children being home schooled in the period of restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic.

This chapter looks at the trends and demographic characteristics of children who received at least one youth caution or court sentence.

3.1 Number of children who received a caution or sentence

Figure 3.1: Number of children given a caution or sentence, England and Wales, years ending March 2011 to 2021

Number of children given a caution or sentence

Around 15,800 children received a caution or sentence in the year ending March 2021. There have been year-on-year falls in each of the last ten years, and in the latest year, 17% fewer children received a caution or sentence than the previous year.

There was an 82% decrease in the number of children who received a caution or sentence compared with ten years ago.

3.2 Demographic characteristics of children who received a caution or sentence

Figure 3.2: Age group and sex of children receiving a caution or sentence compared to the general 10-17 population, England and Wales, year ending March 2021

| Aged 10-14 | Aged 15-17 | Boys | Girls | |

| Children receiving a caution or sentence | 18% | 82% | 87% | 13% |

| 10-17 population | 65% | 35% | 51% | 49% |

Children aged 15-17 made up 82% of the offending population, while making up 35% of the 10-17 population in England and Wales.

Boys made up 87% of the offending population compared with 51% of the 10-17 population in England and Wales.

Figure 3.3: Number of children receiving a caution or sentence by sex, England and Wales, years ending March 2011 to 2021

Number of children receiving a caution or sentence by sex

In the year ending March 2021, around 2,100 girls and around 13,600 boys received a caution or sentence, a decrease of 25% and 16% respectively. The number of girls as a proportion of the total number of children who received a caution or sentence fell to its lowest level (13%), with a decrease of two percentage points compared with the previous year. Compared with the year ending March 2011, the numbers of girls and boys receiving a caution or sentence have fallen by 89% and 79% respectively.

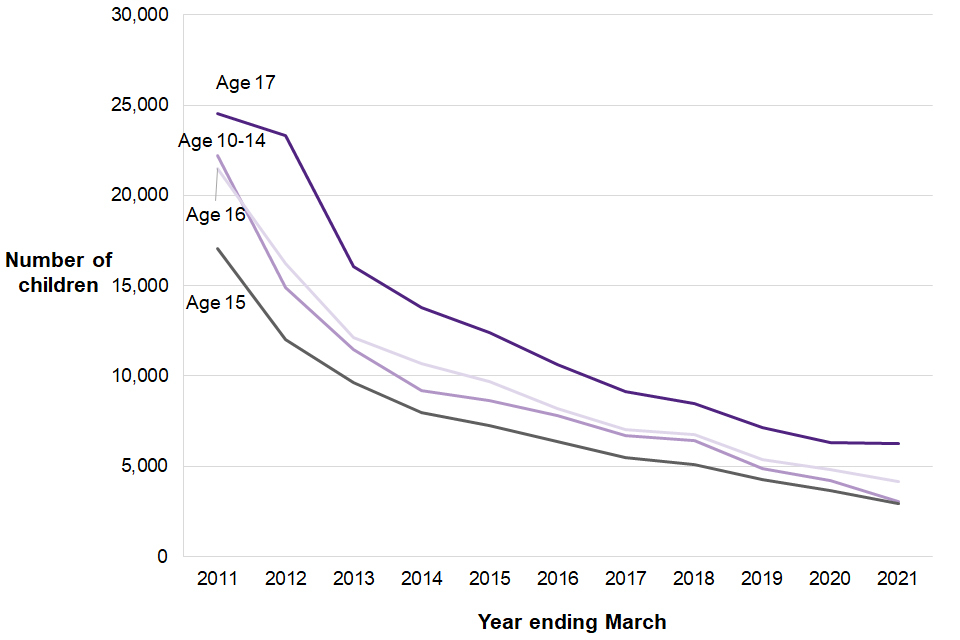

Figure 3.4: Number of children receiving a caution or sentence by age, England and Wales, years ending March 2011 to 2021

Number of children receiving a caution or sentence by age

Figure 3.4 shows that there have been decreases in the number of children given cautions and sentences across all ages.

From the year ending March 2011 to the year ending March 2020, 10 to 14-year-olds made up between 22% and 26% of the total number of children cautioned or sentenced. In the latest year, 10 to 14-year-olds made up 18% of the total, with a year on year fall of five percentage points.

The number of 10 to 14-year-olds cautioned or sentenced decreased by 34% compared with the previous year, while there was a 12% decrease for 15 to 17-year-olds.

This fall for the younger age group may be due to many children being home schooled in the period of restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic.

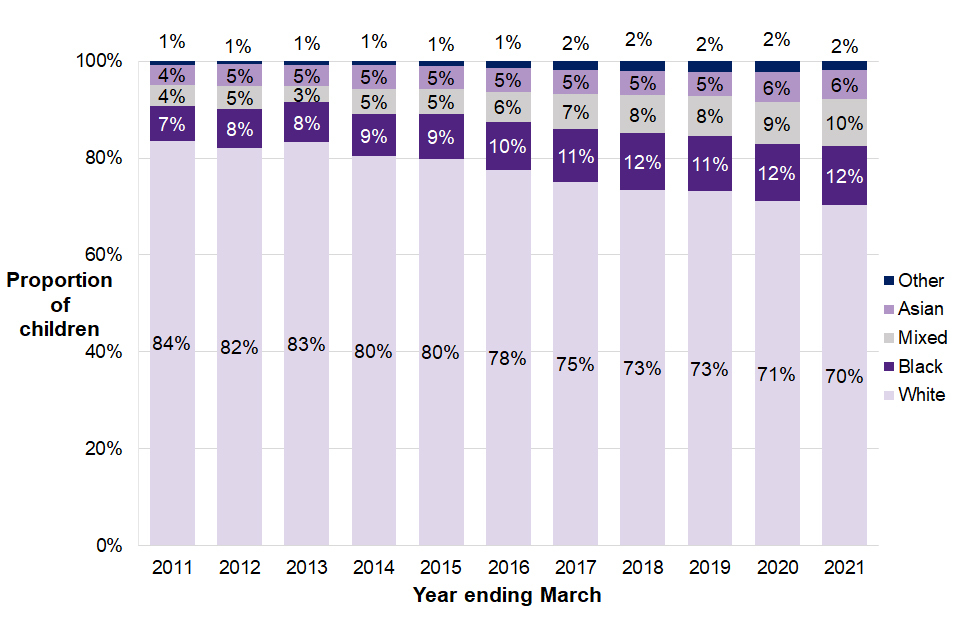

Figure 3.5: Proportion of children receiving a caution or sentence by ethnicity[footnote 5], England and Wales, years ending March 2011 to 2021

Proportion of children receiving a caution or sentence by ethnicity

Supplementary Table 3.1 shows that the number of children given cautions or sentences has varied by ethnicity over the last ten years. This has led to changes in the proportions each ethnic group make up of all cautions and sentences.

Figure 3.5 and supplementary table 3.1 show that:

-

Asian children accounted for 6% of children receiving a caution or sentence in the latest year, which along with the previous year was the highest proportion for that group in the last ten years. There were 21% fewer Asian children who received a caution or sentence compared with the previous year.

-

The proportion of children cautioned or sentenced who are Black has been increasing over the last ten years and is now five percentage points higher than it was in the year ending March 2011 (12% in the latest year compared to 7% in the year ending March 2011).

-

Children from a Mixed ethnic background accounted for 10% of those receiving a caution or sentence in the latest year, more than doubling since the year ending March 2011, when it was 4%.

4. Proven offences by children

In the year ending March 2021:

-

The number of proven offences committed by children fell by 22% from the previous year to just over 38,500, the largest year on year decrease in eight years and the lowest number of proven offences in the time series.

-

Theft offences decreased by 41% from the previous year, which may be due in part to the periods of restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic with non-essential shops closed and changes to people’s behaviour.

-

While the number of violence against the person offences has followed an overall downward trend, this offence group has been steadily increasing as a proportion of all offences over the last ten years, and now accounts for 32% of all proven offences.

-

There were just over 3,500 knife or offensive weapon offences resulting in a caution or sentence committed by children. This is a fall of 21% compared with the previous year.

4.1 Trends in proven offences by children

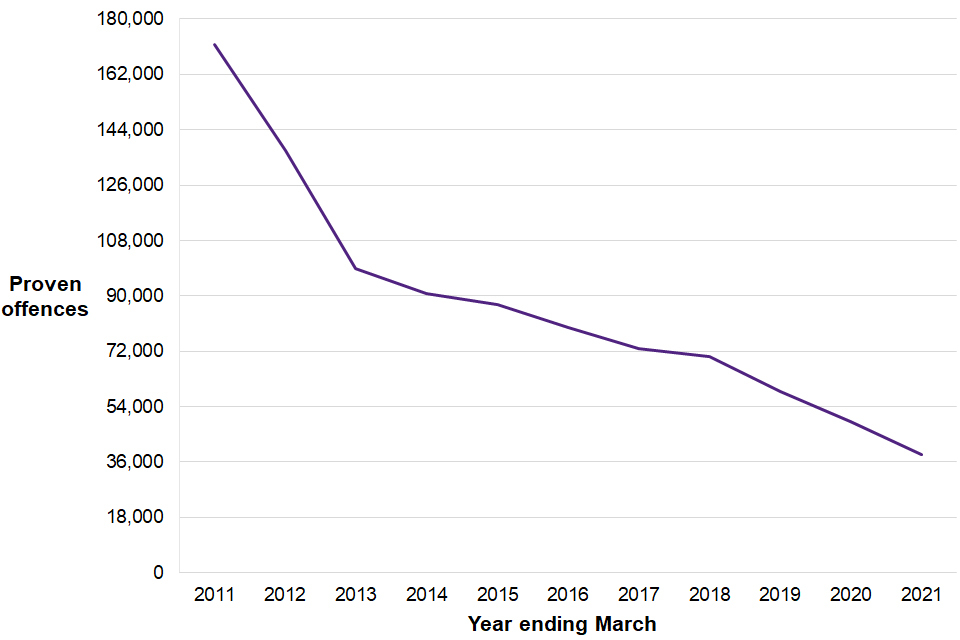

Figure 4.1: Number of proven offences by children, England and Wales, years ending March 2011 to 2021

Number of proven offences by children

The number of proven offences committed by children has continued to fall. In the year ending March 2021, there were just over 38,500 proven offences committed by children which resulted in a caution or sentence in court. This is a fall of 22% from the previous year and a fall of 78% since the year ending March 2011.

As Figure 4.1 shows, there were larger falls in the number of proven offences committed by children between the years ending March 2011 and 2013, with more modest decreases since then, however the 22% fall in the latest year is the largest year-on-year fall since the year ending March 2013.

Offence volumes

Supplementary Table 4.1 shows that in the last ten years, the number of proven offences has fallen across all offence groups. Theft and breach of statutory order are the two offence groups to see the largest fall over this time (both decreasing by 91%).

Compared with the previous year, Sexual offences was the only offence group to see an increase (rising by 2% from around 880 to 900). Breach of statutory order and theft offences saw the largest year on year decreases falling by 45% and 41% respectively. The decrease in theft offences may be due in part to the periods of restrictions when non-essential shops were closed and changes to people’s behaviour including reduced social contact, during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Supplementary Table 4.3 shows that in the year ending March 2021, most proven offences were committed by children who were[footnote 6] :

-

Boys (86%),

-

Aged 15-17 (84%), and

-

White (72%).

Offence volumes as a proportion of total

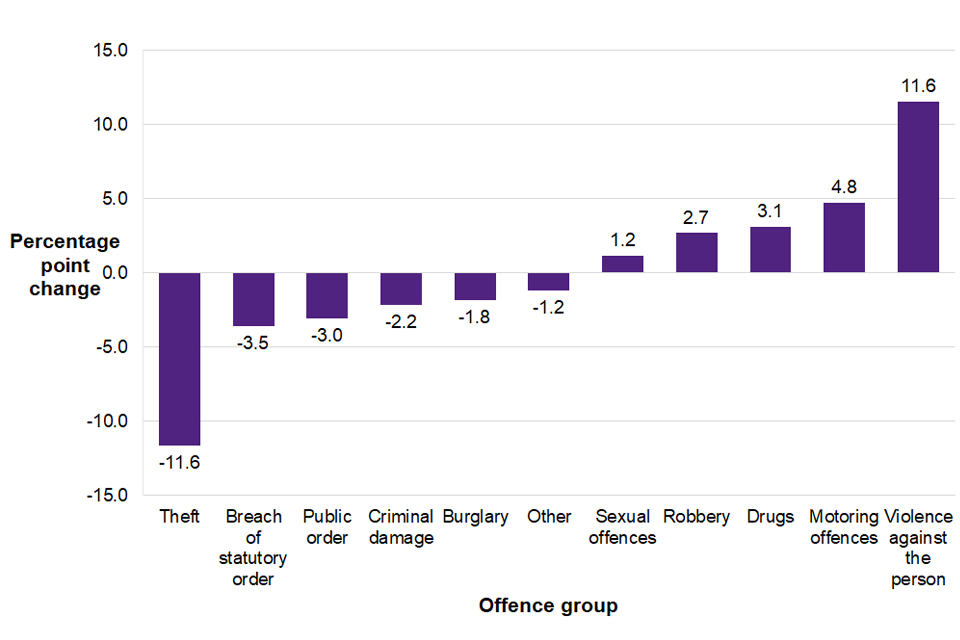

Figure 4.2: Percentage point change in the proportion of proven offences committed by children, England and Wales, between the years ending March 2011 and 2021

Percentage point change in the proportion of proven offences committed by children

Whilst the number of proven offences committed by children has fallen for all crime types when compared with ten years ago, the proportions of these offence groups has been changing (Figure 4.2). Violence against the person offences have seen the greatest increase in proportion, gradually increasing from 21% in the year ending March 2011 to 32% of proven offences in the latest year.

Theft and handling stolen goods offences have seen the largest proportional decrease in the last ten years, falling by over half from 19% in the year ending March 2011 to 7% in the latest year.

4.2 Offence group by gravity score

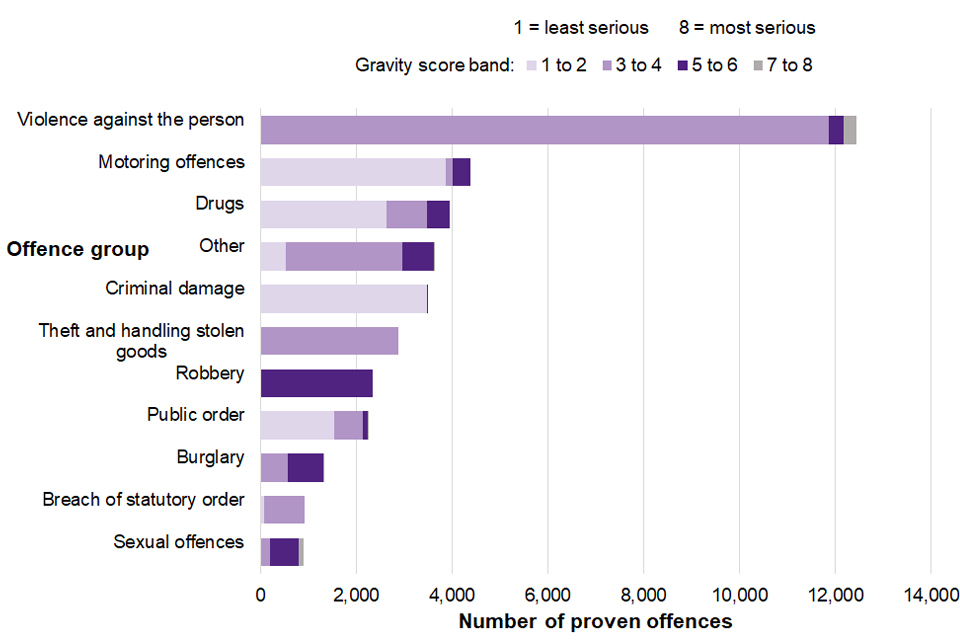

Figure 4.3: Proven offences by children, by offence group and gravity score band, England and Wales, year ending March 2021

Proven offences by children, by offence group and gravity score band

An offence’s gravity score is scored out of eight, ranging from one (less serious) up to eight (most serious).

As Figure 4.3 shows, while the violence against the person offence group made up the largest share of offences, only a small proportion of offences (5%) within this group had a higher gravity score of five to eight. For offences within robbery, burglary and sexual offences, the majority had a higher gravity score of five to eight.

In the latest year, around 130 proven offences committed by children had the highest gravity score of eight, which accounts for 0.3% of all proven offences (Supplementary Table 4.4).

Figure 4.4: Proportion of proven offences by gravity score band and demographic characteristics, England and Wales, year ending March 2021

| Gravity Score 1 to 4 (Less Serious) | Gravity Score 5 to 8 (Most Serious) | ||

| Ages | 10-14 | 88% | 12% |

| 15-17 | 84% | 16% | |

| Ethnicity | Asian | 81% | 19% |

| Black | 77% | 25% | |

| Mixed | 81% | 19% | |

| Other | 75% | 25% | |

| White | 87% | 13% | |

| Sex | Girls | 94% | 6% |

| Boys | 83% | 17% |

Figure 4.4 shows that the proportion of proven offences with a gravity score in the higher band of five to eight, was greater for:

-

Those aged 15-17 (16% compared to 12% of offences committed by 10 to 14-year-olds),

-

Black children and Other children (both 25%, with the other ethnic groups ranging from 13% to 19%), and

-

Boys (17%, compared to 6% for girls).

4.3 Knife or offensive weapon offences committed by children

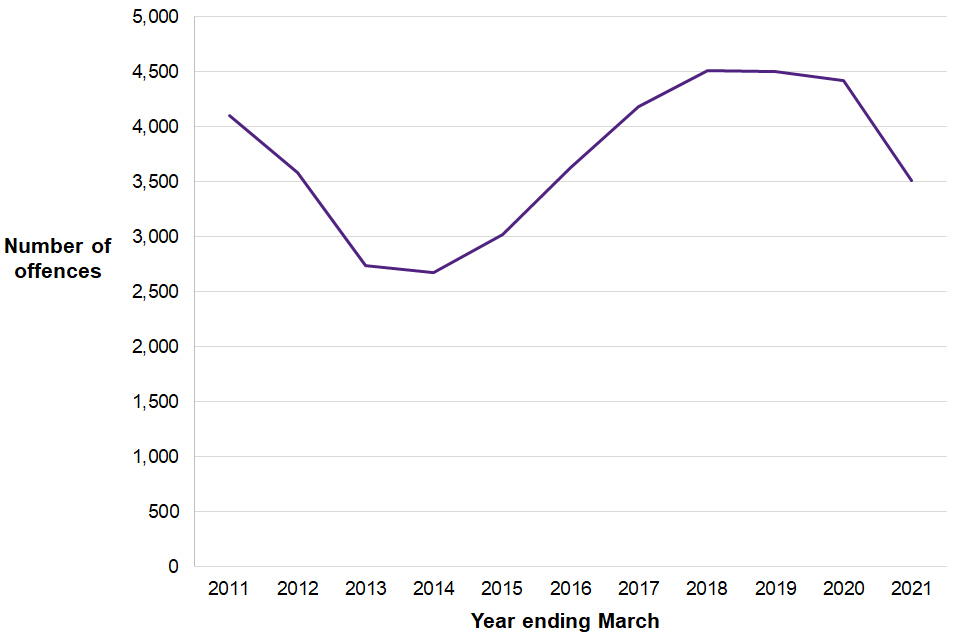

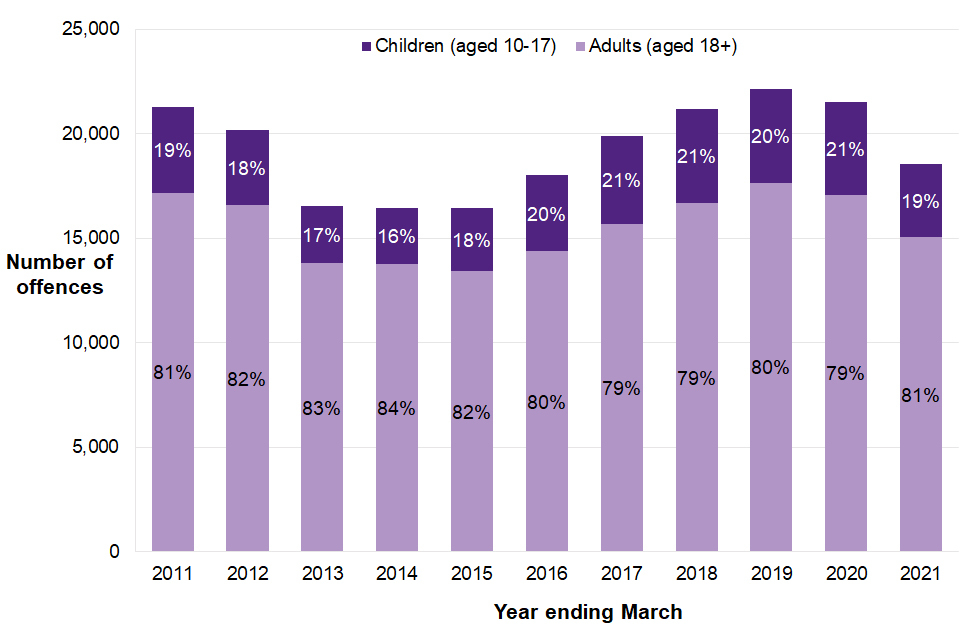

Figure 4.5: Knife or offensive weapon offences committed by children, resulting in a caution or sentence, England and Wales, years ending March 2011 to 2021

Knife or offensive weapon offences committed by children

This section covers offences for which children received cautions or sentences for possession of an article with a blade or point, possession of an offensive weapon, or threatening with either type of weapon. In the year ending March 2021, there were just over 3,500 knife or offensive weapon offences committed by children resulting in a caution or sentence, which is 21% lower than the previous year and 14% lower than ten years ago. This is the third year in succession that has seen a decrease in the number of these offences.

In the latest year, the majority (97%) of knife or offensive weapon offences committed by children were possession offences and the remaining 3% were threatening with a knife or offensive weapon offences. These proportions have remained broadly stable over the last five years[footnote 7].

Supplementary Table 4.7 shows that in the year ending March 2021, just over half (51%) of disposals given to children for a knife or offensive weapon offence were a community sentence. This proportion is broadly stable over the last five years.

37% of children received a caution, which is an increase from 34% in the previous year and is the highest proportion seen across the last ten years.

The proportion of children sentenced to immediate custody decreased from 10% to 7% in the last year, which is the lowest proportion seen across the last ten years.

5. Sentencing of children

In the year ending March 2021:

-

There were just over 12,200 occasions where children were sentenced at court, which is 28% lower than the previous year. This fall is likely to be due in part to the impact of court closures and pauses to jury hearings during the periods of restrictions in the COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent backlog of cases.

-

The average time from offence to completion was 219 days, compared with 172 days in the previous year. This was despite the number of children proceeded against in court falling by 24% compared with the previous year and, again, is likely due to court closures and court backlogs during the COVID-19 pandemic.

-

Of all sentencing occasions for indictable offences, the proportion[footnote 8] of sentencing occasions involving Black children for indictable offences increased from 16% in the year ending March 2016 to 21% in the latest year.

-

The average custodial sentence length for all offences has increased by over five months over the last ten years from 11.4 months to 16.8 months.

This chapter focuses on trends of children proceeded against at court, time taken from offence to completion at court and sentences received at court by children by type of sentence and court.

5.1 Children proceeded against

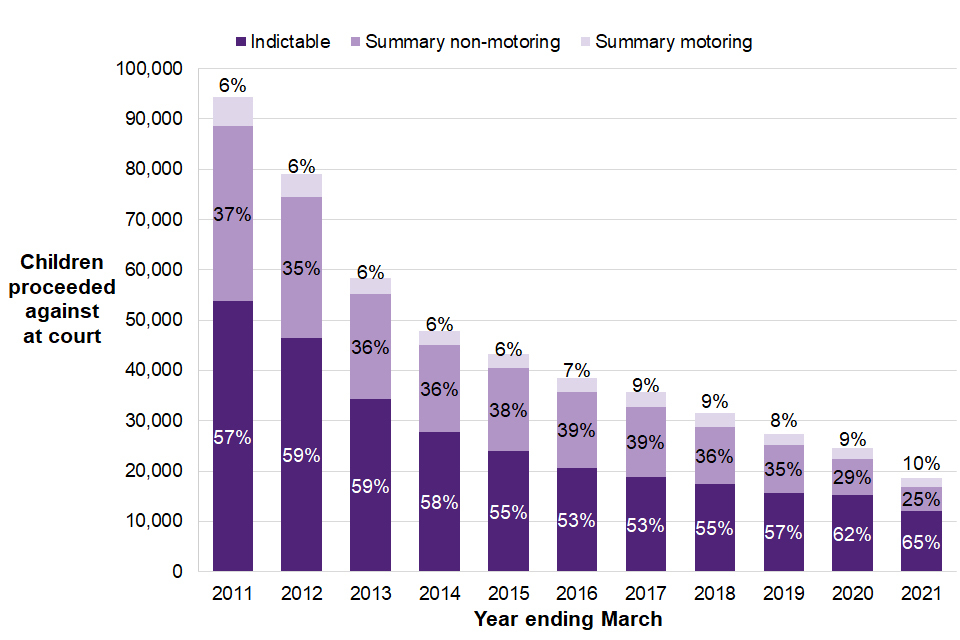

Figure 5.1: Children proceeded against at court, England and Wales, years ending March 2011 to 2021

Number of children proceeded against at court

There were around 18,600 children proceeded against at court in the year ending March 2021, a fall of 24% in the latest year and a fall of 80% compared to ten years ago. Almost two thirds (65%) of these proceedings were for indictable offences, 25% were for summary non-motoring offences and the remaining 10% were for summary motoring offences (Supplementary Table 5.1).

5.2 Average time from offence to completion at court

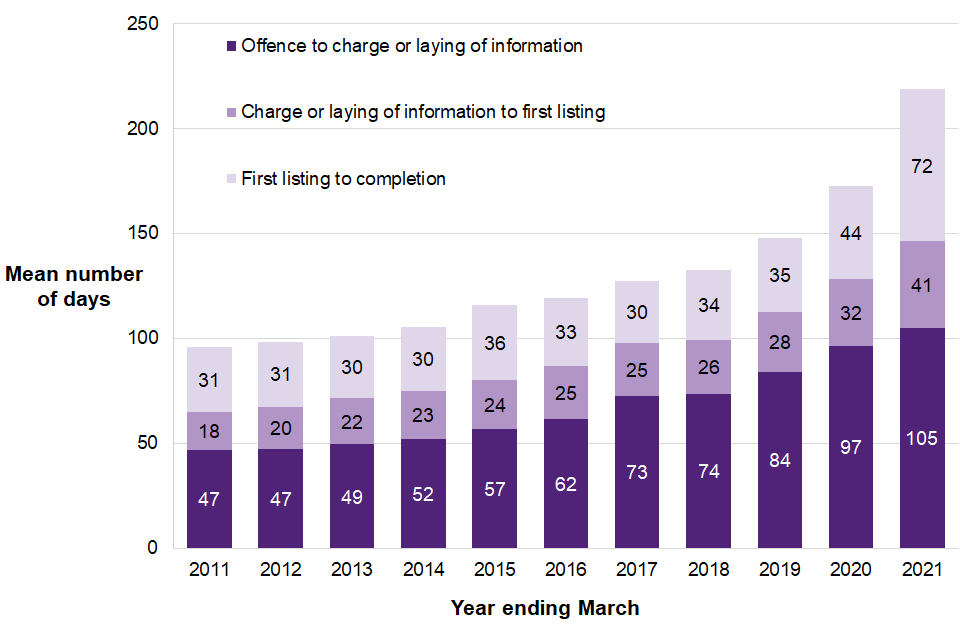

Figure 5.2: Average time from offence to completion at court, England and Wales, years ending March 2011 to 2021

Average time from offence to completion at court

Figure 5.2 shows the average (mean) number of days taken from the day of the offence or alleged offence to the day the case was concluded at court with the child being found guilty or acquitted.

In the year ending March 2021, the average time from offence to completion was 219 days, compared with 172 days in the previous year and 96 days in the year ending March 2011.

The average time for offence to completion has increased in each of the last ten years, though the year ending March 2021 saw the biggest year on year increase in the time series.

Figure 5.2 shows year-on-year increases across all measures for offence to completion. The average days for:

-

offence to charge or laying of information increased by eight days (9%) to 105 days;

-

charge or laying of information to first listing increased by nine days (30%) to 41 days; and;

-

first listing to completion, which increased by 28 days (64%) to 72 days.

The average time from first listing to completion was between 31 days and 44 days in the years ending March 2011 to 2020. The increase in the latest year to 72 days is very likely to be an impact of the court closures, pauses to jury trials and subsequent backlogs in the periods of restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic.

5.3 Sentencing of children in all courts

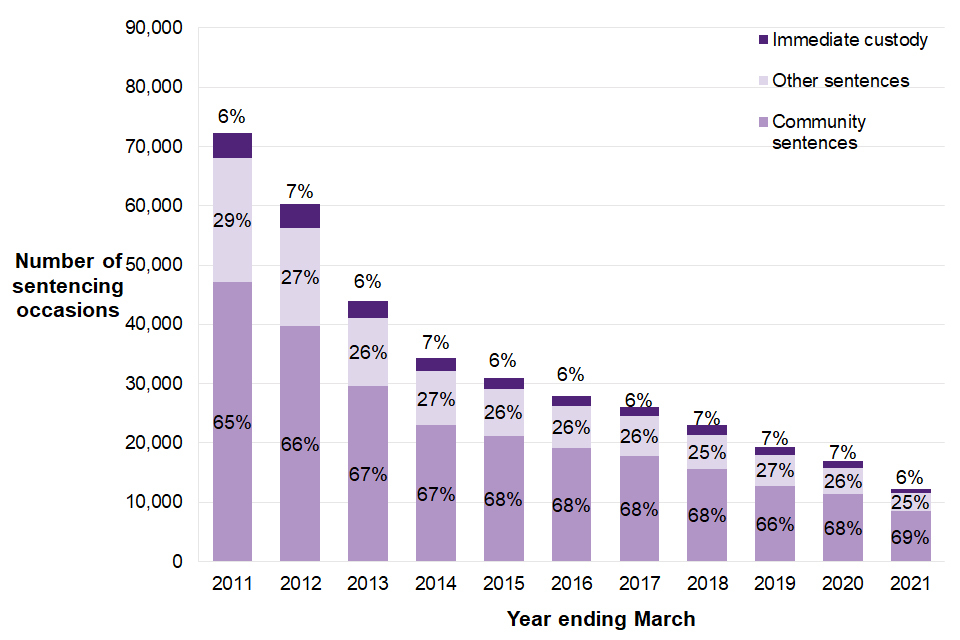

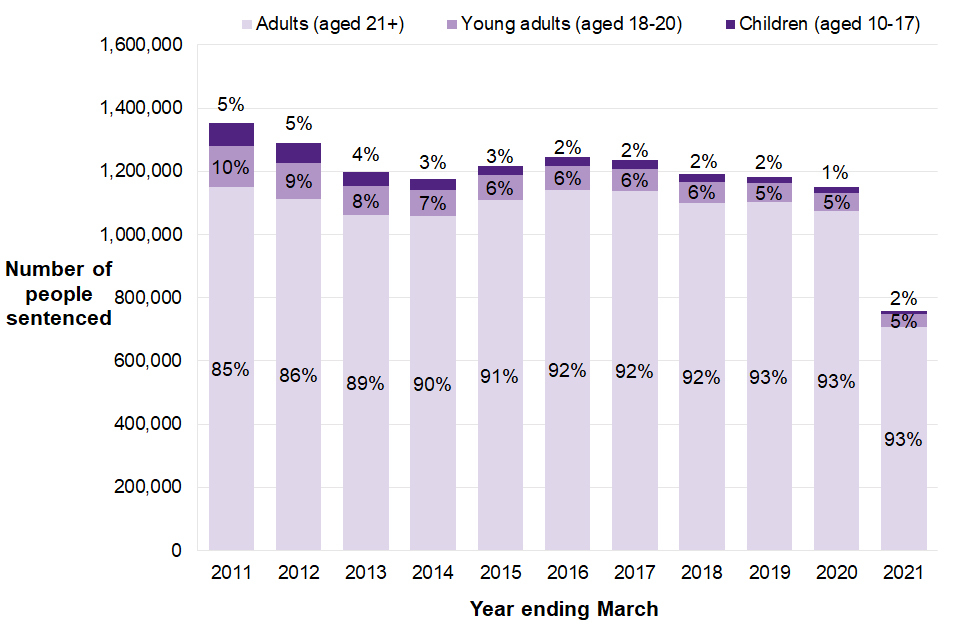

Figure 5.3: Number of sentencing occasions of children in all courts by sentence type, England and Wales, years ending March 2011 to 2021

Number of sentencing occasions of children in all courts by sentence type

There were just over 12,200 occasions where children were sentenced in all courts in the latest year, which is 28% lower than the previous year and 83% lower than the year ending March 2011. There have been year-on-year falls in the number of sentencing occasions of children over the last ten years, with the latest year being the largest yearly percentage decrease in the time series.

The number of custodial sentences decreased by 41% from the previous year, the biggest year-on-year percentage decrease since the time series began. This is likely to be due to court closures, remote hearings and pauses to jury trials in the periods of restrictions and the subsequent backlog that built up during the COVID-19 pandemic with custodial cases tending to be more serious and taking longer at court and more likely to require jury trials.

As Figure 5.3 shows, although the number of custodial sentences fell by 84% over the last ten years, the proportion of custodial sentences has remained broadly stable, varying between 6% and 7% over this period.

Supplementary Table 5.4 shows that in the year ending March 2021, of the 12,200 sentencing occasions of children for all types of offences in all courts there were:

-

Around 670 sentences to immediate custody (6% of all sentences), with most (75%) of these being Detention and Training Orders;

-

Around 8,500 community sentences (69% of all sentences), of which 71% were Referral Orders (around 6,000) and 29% were Youth Rehabilitation Orders (around 2,500); and

-

Just under 3,100 other types of sentences (25% of all sentences); these include absolute and conditional discharges, fines and other less common disposals.

5.4 Sentencing of children by court type

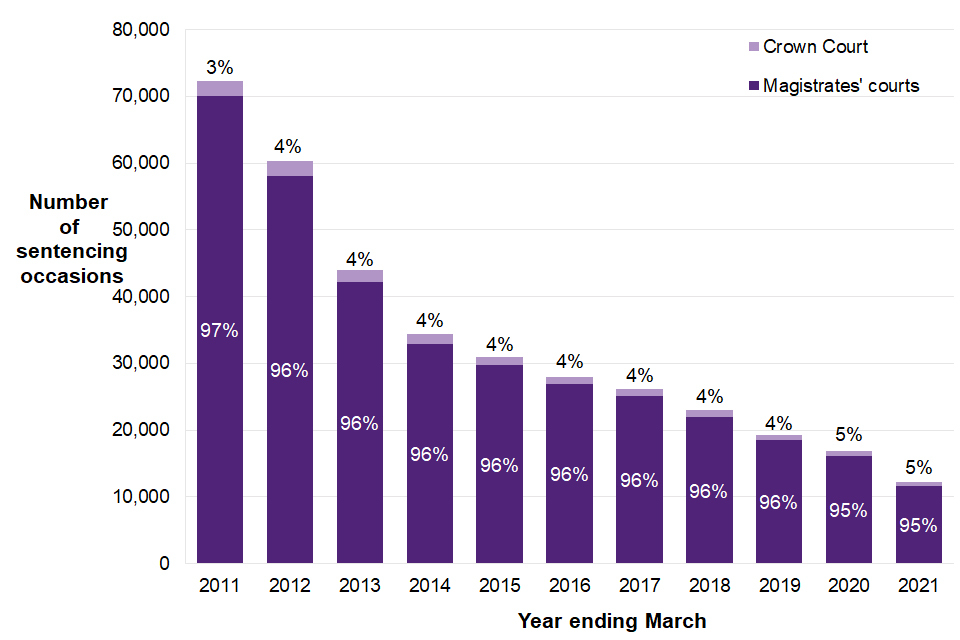

Figure 5.4: Number and proportion of sentencing occasions of children by court type, England and Wales, years ending March 2011 to 2021

Number and proportion of sentencing occasions of children by court type

Depending on the seriousness of the offence, cases will either be heard in a magistrates’ court from start to finish or will be referred from a magistrates’ court to the Crown Court. The Crown Court only hears cases involving more serious offences, so a much smaller number of children are sentenced in this type of court compared with magistrates’ courts.

In the latest year, just 5% (around 600) of all sentencing occasions of children were at the Crown Court. This proportion has remained broadly stable over the last ten years varying between 3% and 5% (Figure 5.4).

The fact the Crown Court tries the most serious cases is reflected in the types of sentences given. In the year ending March 2021, custodial sentences were given in 41% (around 240) of the 580 sentencing occasions of children at the Crown Court. This compares to just 4% (around 440) of the 11,600 sentencing occasions at magistrates’ courts.

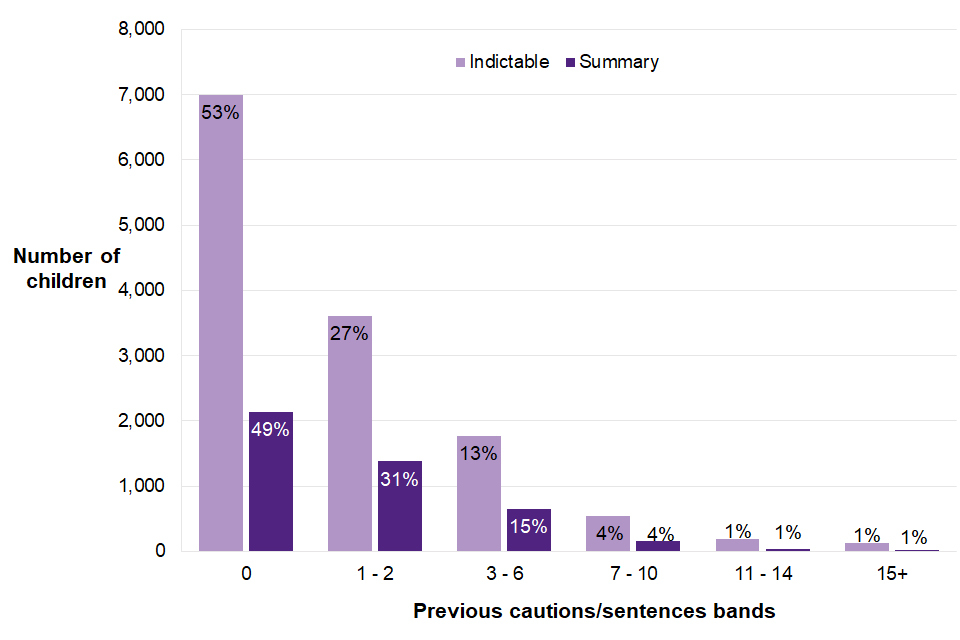

5.5 Sentencing of children at all courts by type of offence

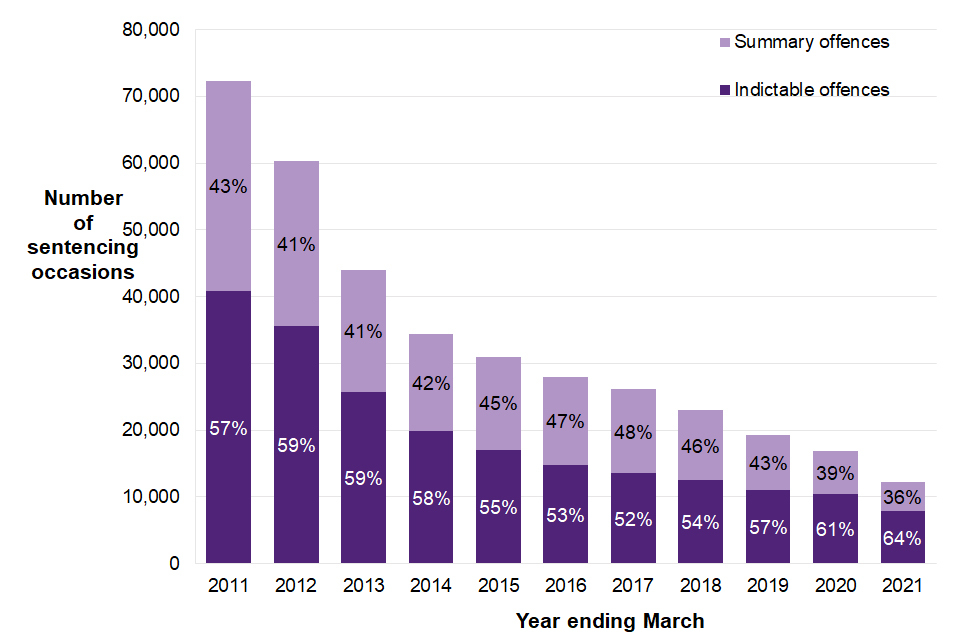

Figure 5.5: Number of sentencing occasions of children sentenced in all courts by type of offence, England and Wales, years ending March 2011 to 2021

Number of sentencing occasions of children sentenced in all courts by type of offence

Of the 12,200 occasions in which children were sentenced in the year ending March 2021, 64% were for indictable offences and 36% were for summary offences. This compares to 57% being indictable offences and 43% for summary offences ten years ago. The proportion of sentencing occasions of children for indictable offences has been increasing over the last four years.

Of the almost 7,900 occasions on which children were sentenced for indictable offences in the latest year, 78% involved a community sentence, whereas, of the 4,300 occasions in which children were sentenced for summary offences, 54% involved a community sentence.

In the year ending March 2021, 8% of the occasions in which children were sentenced for indictable offences involved a sentence to immediate custody, compared with 1% for summary offences (Supplementary Tables 5.4a and 5.4b).

5.6 Sentencing of children for indictable offences by ethnicity[footnote 9]

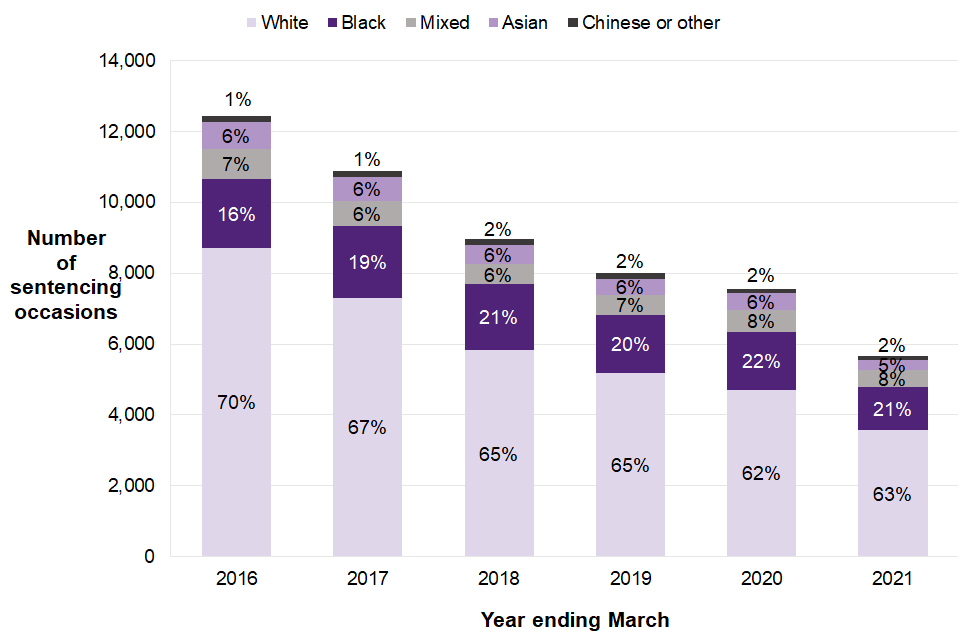

Figure 5.6: Number of sentencing occasions of children sentenced for indictable offences by ethnicity, England and Wales, years ending March 2016 to 2021

Number of sentencing occasions of children sentenced for indictable offences by ethnicity

In the year ending March 2021, the number of occasions on which children were sentenced at court for indictable offences varied by ethnicity[footnote 10]. In the latest year there were:

-

around 3,600 sentencing occasions for White children;

-

just over 1,200 sentencing occasions for Black children;

-

around 470 sentencing occasions for Mixed children;

-

just under 300 sentencing occasions for Asian children; and

-

around 110 sentencing occasion for Chinese or Other children.

Over the last five years, there have been decreases in the number of occasions in which children of each ethnicity group have been sentenced at court for indictable offences. The decrease in sentencing occasions for White children has been at a higher rate than for those in other ethnic groups.

This has led to a decrease in the proportion of all occasions in which White children were sentenced for indictable offences from 70% in the year ending March 2016 to 63% in the latest year. Conversely, over the same period the proportion of all occasions in which Black children were sentenced for indictable offences increased from 16% to 21%. The proportions for other groups have remained broadly stable.

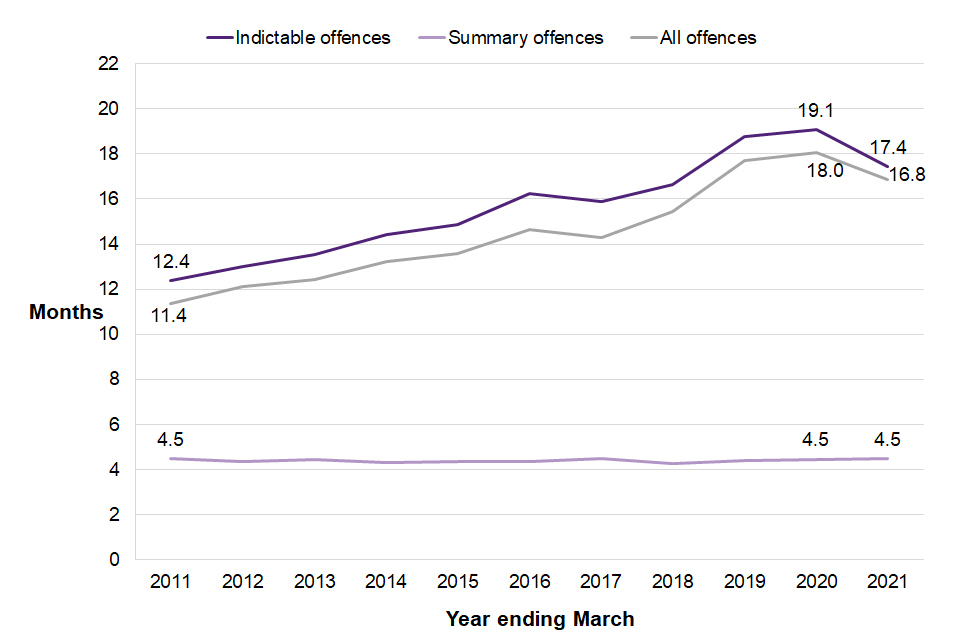

5.7 Average custodial sentence length[footnote 11]

Figure 5.7: Average custodial sentence length in months by type of offence, England and Wales, years ending March 2011 to 2021

Average custodial sentence length in months by type of offence

For children sentenced to custody, the average custodial sentence length varied based on the type of offence the child was sentenced for. In the latest year, the average custodial sentence length was:

-

16.8 months for all offences;

-

17.4 months for indictable offences; and

-

4.5 months for summary offences.

While the average custodial sentence length remained broadly stable for summary offences, it has increased by five months for indictable offences over the same period, from 12.4 to 17.4 months but decreased by almost two months from the previous year’s average of 19.1 months.

6. Use of remand for children

In the year ending March 2021:

-

Almost three quarters (74%) of children remanded to youth detention accommodation did not subsequently receive a custodial sentence. This is the highest level seen on record. It is likely that fewer cases for children overall have made progress through the courts due to the backlog in response to COVID-19 restrictions.

-

The average number of children held on remand accounted for 40% of all children in youth custody, the largest proportion in the last ten years and nine percentage points higher than the previous year. It’s likely that court closures and subsequent backlogs during the COVID-19 pandemic was a factor in this.

-

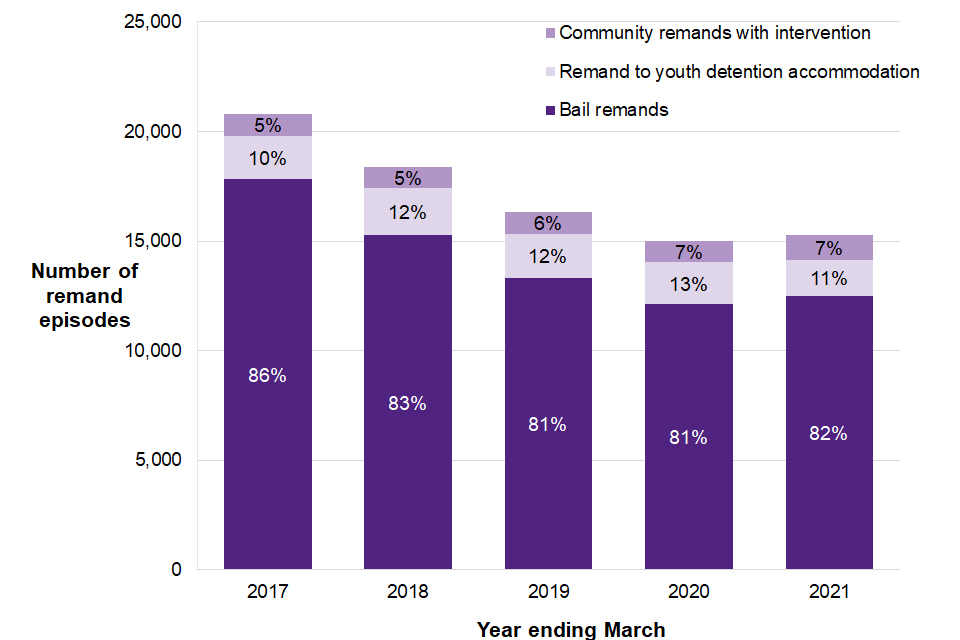

There were around 15,300 remand episodes[footnote 12] of which the majority (82%) were bail remands, with youth detention accommodation remands accounting for 11%, and the remaining 7% being community remands with intervention.

This chapter presents data on trends of use of remand for children aged 10-17, characteristics of the custodial remand population and the outcomes for children following custodial remand. There has been a change to the counting rules for the types of remand given to children. Please see the Guide to Youth Justice Statistics for further details.

6.1 Types of remand given to children

Figure 6.1: Type of remand given to children, England and Wales, years ending March 2017 to 2021

Type of remand given to children

This data shows the number of remand decisions made for outcomes occurring in each year. There has been a change of counting rules this year, whereby only the most restrictive remand decision applied to the most restrictive outcome on a given day during the court proceeding is counted.

Where a child was given more than one remand decision during the court process, only the most restrictive is shown. Where a child was given multiple outcomes on the same day, only the most restrictive is counted. There may be some double counting if children received different outcomes on different days.

There were around 15,300 remands given to children in the year ending March 2021, of which:

-

the majority (82%) were bail remands;

-

11% were remands to youth detention accommodation; and

-

the remaining 7% were community remands with intervention.

There was a 2% increase on the number of remand episodes compared to the previous year. This was driven by increases in Community Remands with Intervention which increased by 13% and Bail Remands, which increased by 3%. Remands to Youth Detention Accommodation decreased by 13% from the previous year.

For remands given in the year ending March 2021, the breakdown of demographics (Supplementary Table 6.1) shows:

-

Most episodes (89%) involved boys;

-

The majority (89%) involved children aged 15-17; and

-

Most episodes were given to White children (57%), while Black children and Mixed children were the next highest (22% and 13% respectively)[footnote 13].

6.2 Average monthly population of children on remand in youth custody

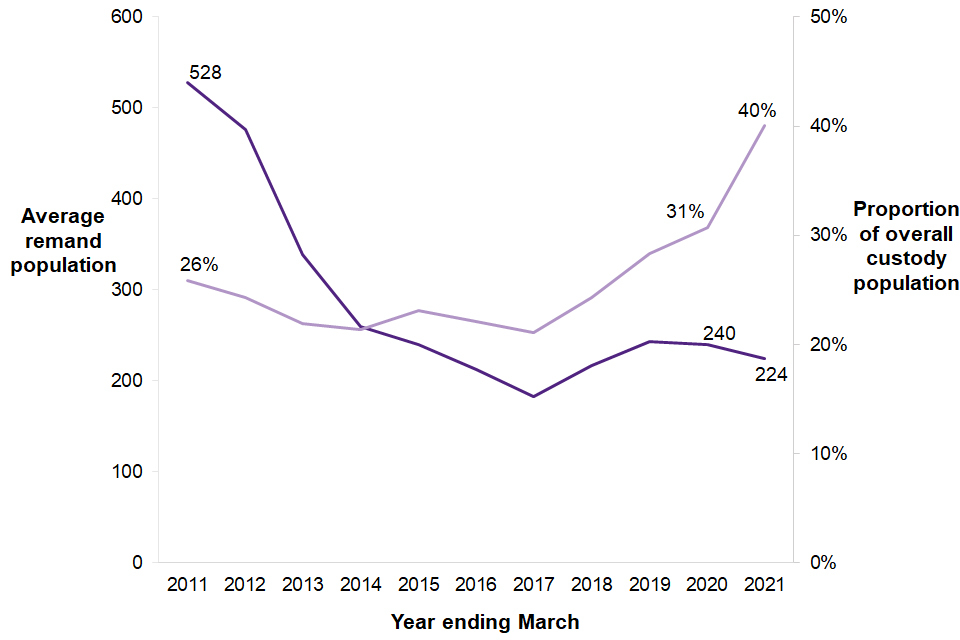

Figure 6.2: Average monthly population of children on remand in youth custody, youth secure estate in England and Wales, years ending March 2011 to 2021

Average monthly population of children on remand in youth custody

There was an average monthly population of around 220 children remanded in youth custody at any one time in the year ending March 2021, which was 6% lower than the previous year and 57% lower than ten years ago.

Children remanded in youth custody accounted for 40% of the average youth custody population in the latest year, an increase from 31% in the previous year. This is the highest proportion seen in the last ten years.

While there was a year on year decrease in the remand population, the sentenced population decreased at a greater rate. Prior to the year ending March 2021, the proportion of the total custody population that children remanded to youth custody comprised had fluctuated between 21% and 31%. The increase is likely due to court closures, remote hearings and pauses to jury trials in the periods of restrictions and subsequent backlogs built up during the COVID-19 pandemic, leading to children spending longer in custody on remand (Supplementary Table 6.3).

Supplementary Tables 6.3 and 6.4 show that for children remanded in youth custody, the majority were:

-

in a Young Offender Institution (74%);

-

male (98%), a proportion which has remained broadly stable over the last ten years);

-

from an ethnic minority group (60%); and

-

aged 17 (60%), an increase from 51% in the previous year.

See Chapter 7 for information on the length of time children spent in youth custody on remand.

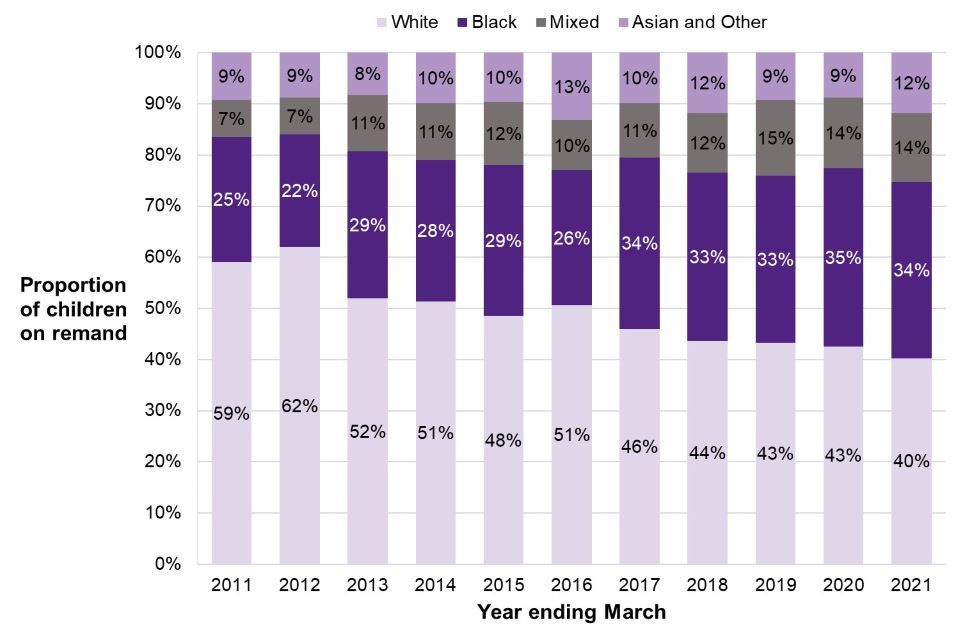

Figure 6.3: Proportion of children in youth custody on remand by ethnicity[footnote 14], youth secure estate in England and Wales, years ending March 2011 to 2021

Supplementary Table 6.3 shows that in the latest year, the average number of children in custody on remand has decreased for each ethnic group, except for children from an Asian or Other background, which increased by an average of five.

This is represented in Figure 6.3, which shows that the proportion that ethnic minority groups comprised increased from 57% to 60% in the last year. This is the highest proportion in the last ten years and compares to 41% ten years ago.

Figure 6.3 also shows that:

-

over the last ten years the proportion of children from a White background remanded in youth custody has seen a general downward trend, falling from 59% to 40%, the lowest level in the last ten years;

-

children from a Mixed ethnic background account for 14% of those remanded in youth custody in the latest year, which is the same as the previous year but double compared to ten years ago (7%); and

-

the proportion of children from an Asian or Other background rose to 12%, from 9% in the previous year. This proportion has fluctuated between 8% and 13% over the last ten years.

6.3 Outcomes for children following remand to youth detention accommodation

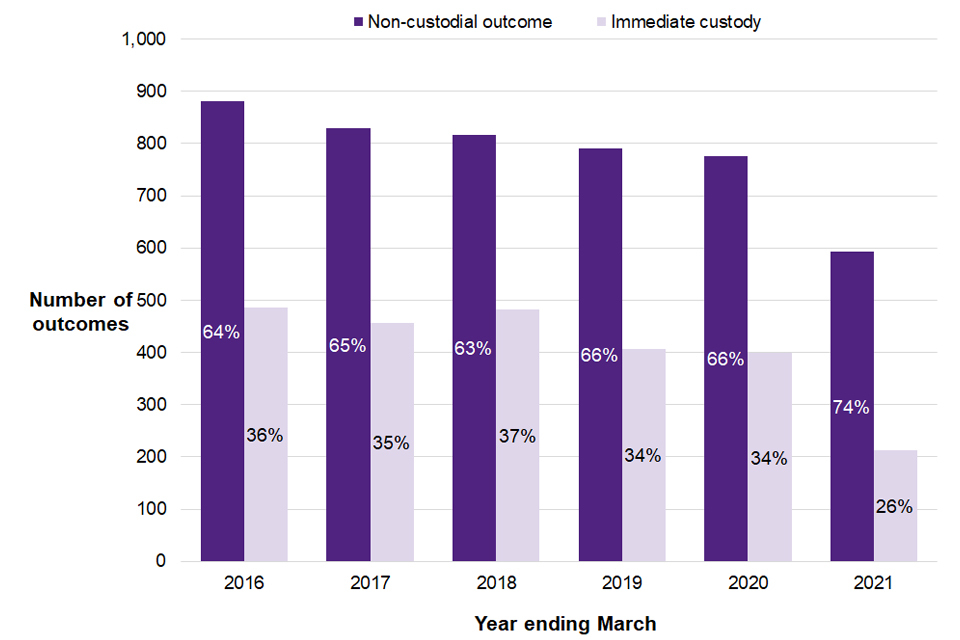

Figure 6.4: Outcomes following remand to youth detention accommodation, England and Wales, years ending March 2016 to 2021

Outcomes following remand to youth detention accommodation

In the year ending March 2021, while the number of outcomes for children remanded to custody was 31% lower than the previous year, almost three quarters (74%) of outcomes for children remanded to youth detention accommodation at some point during court proceedings did not subsequently result in a custodial sentence. This was the highest proportion in the time series, which had previously remained broadly stable, fluctuating between 64% and 66% and was an increase of eight percentage points from the previous year.

In the latest year, there were just over 800 outcomes following a remand to youth detention accommodation and 37% of these outcomes resulted in acquittal.

Of the 74% (almost 600) outcomes which did not result in a custodial sentence, half resulted in a non-custodial sentence and half resulted in acquittal. The proportion receiving a non-custodial sentence was one percentage point higher than the previous year, while the proportion who were acquitted was seven percentage points higher than the previous year.

An increase in the proportion of acquittals in the most recent year is likely driven by large decreases seen in the volume of immediate custody sentences (down 47%) and non-custodial sentences (down 31%). This makes the proportions of acquittals artificially inflate for the year ending March 2021 (up 7 percentage points at all courts), despite acquittals still decreasing 15% since the previous year. It is likely that fewer sentences for children overall have made progress through the courts due to the backlog in response to COVID restrictions.

The proportion of outcomes for those who were remanded to youth detention accommodation at any point during court proceedings which did not result in a youth detention accommodation sentence varies by court type. In the latest year, 86% of those sentenced at magistrates’ courts and 57% of those sentenced at the Crown Court did not go on to receive a custodial sentence (Supplementary Table 6.6).

This proportion also varies by ethnicity (Supplementary Table 6.7). The proportion of outcomes for those remanded to youth detention accommodation who did not go on to get a custodial sentence varies from 52% for Asian children, 69% for Mixed children, 74% for White children, 76% for Black children, and 79% of Chinese and Other children, however this figure should be treated with caution due to small numbers (fewer than 15 children).

7. Children in youth custody

In the year ending March 2021:

-

There was an average of 560 children in custody at any one time during the year. This is a fall of 28% fall against the previous year, the biggest year on year percentage decrease since the time series began and is likely due to fewer children being sentenced to custody during the COVID-19 pandemic.

-

The proportion of children held in custody on remand increased from 31% to 40% compared to the previous year, the largest proportion since the time series began and is likely due to court closures and backlogs during the COVID-19 pandemic.

-

While the number of children in youth custody from a Black background decreased in the last year, as the whole population has decreased, Black children accounted for 29% of the youth custody population. This is an increase from 28% last year and 18% ten years ago.

-

The number of custodial episodes ending fell by 36% compared with the previous year, which reflects the fall in the custodial population and is likely due to fewer children being placed in custody during the COVID-19 pandemic.

-

Children spent an average of 16 nights longer on remand than the previous year. The proportion of remands that lasted 274 nights or more increased by 10 percentage points compared with the previous year, from 3% to 13%, which is likely due to pauses to jury trials and court backlogs during the COVID-19 pandemic.

This chapter presents data on trends of children (aged 10-17) in youth custody in England and Wales by demographic characteristics, offence types, legal basis for detention, distance from home and data on length of time in custody.

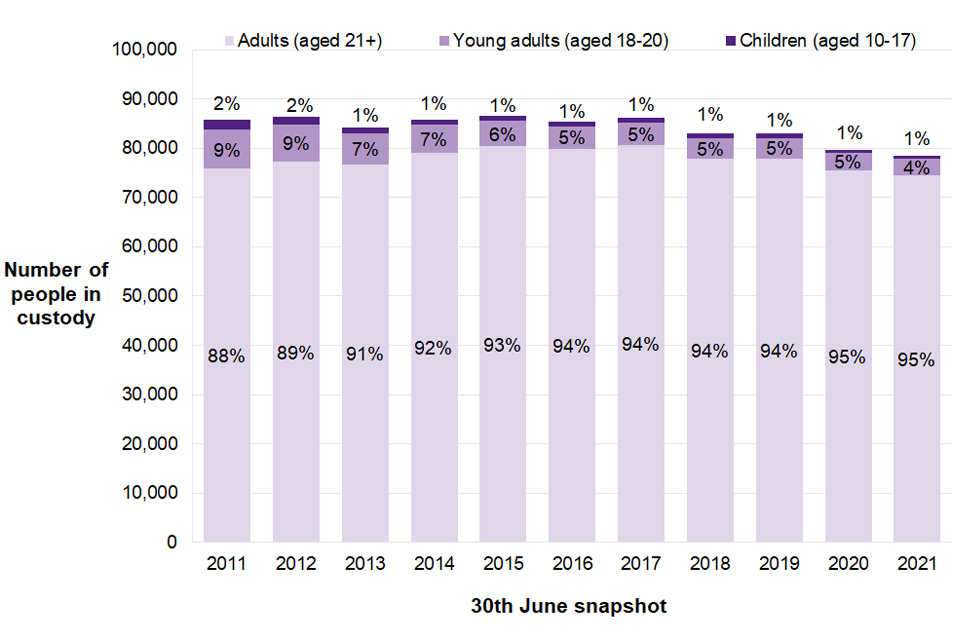

7.1 Average monthly youth custody population

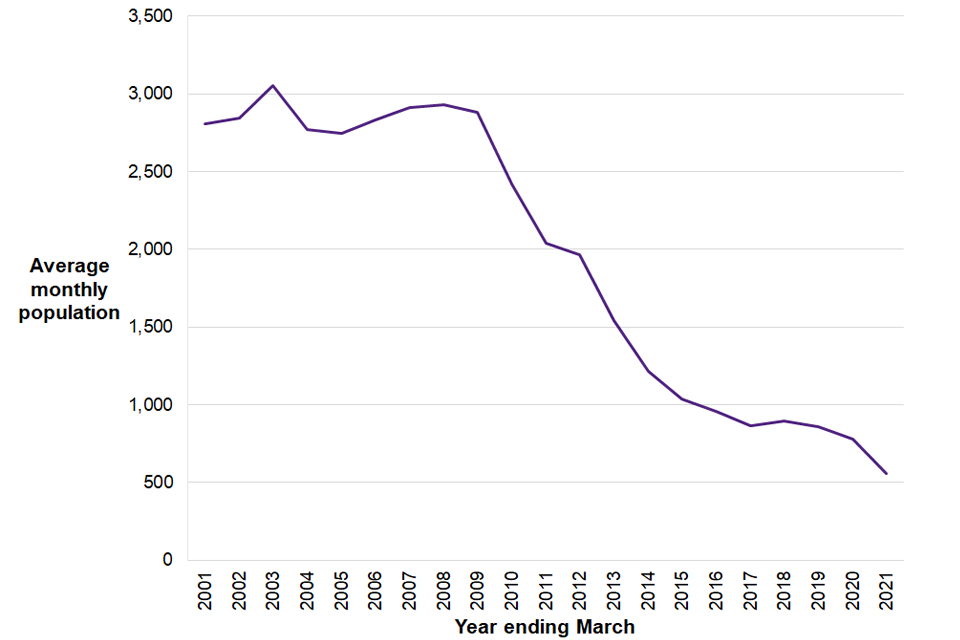

Figure 7.1:Average monthly youth custody population, youth secure estate in England and Wales, years ending March 2001 to 2021

Average monthly youth custody population

While the average youth custody population has fallen in each of the last ten years, in the year ending March 2021, it decreased by 28%. This was the biggest year on year decrease since the time series began and likely due in part to the impacts of the periods of restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic where fewer children were being sentenced to custody when courts were closed, jury hearings paused and backlogs of court cases built up.

In the year ending March 2021, there was an average of 560 children in custody at any one time which was the lowest number on record. This is a reduction of 73% compared with ten years ago, when there was an average of around 2,040 children in custody.

7.2 Average monthly youth custody population by sector

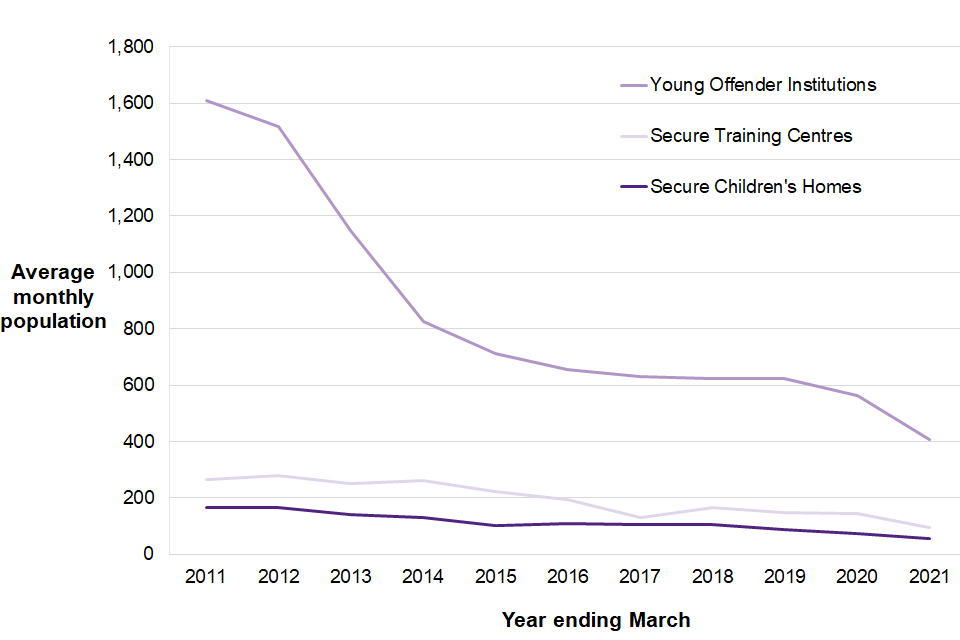

Figure 7.2: Average monthly youth custody population by sector, youth secure estate in England and Wales, years ending March 2011 to 2021

Average monthly youth custody population by sector

The largest long-term fall in the average monthly youth custody population has been seen in the number of children in Young Offender Institutions (YOI), falling 75% over the last ten years, with a 27% fall in the last year. As in previous years, in the year ending March 2021 the majority of children in custody were in a YOI (73%).

The average monthly population of Secure Children’s Homes (SCH) decreased by 65% over the last ten years, with a 23% fall compared with the previous year. As in the previous year, this accounts for 10% of the youth secure estate population.

Secure Training Centres (STC) decreased by 64% over the last ten years, with a 35% decrease compared with the previous year. Of all children in custody, 17% were held in an STC in the latest year.

7.3 Legal basis for detention of children in custody

Information on the legal basis for detention relates to the most serious legal basis for which a child is placed in custody.

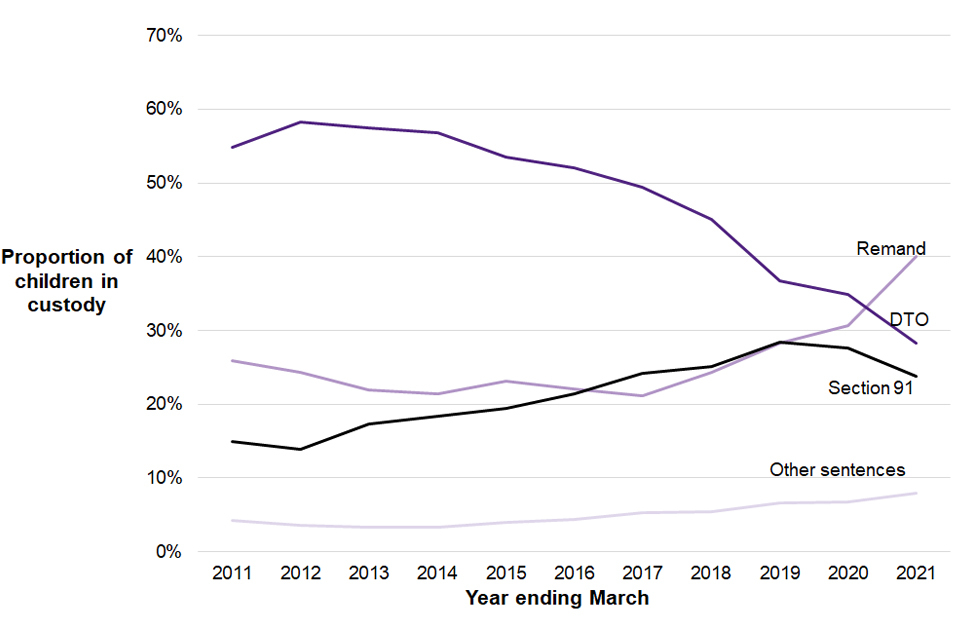

Figure 7.3: Average monthly youth custody population by legal basis for detention as a proportion of the total, youth secure estate in England and Wales, years ending March 2011 to 2021

Average monthly youth custody population by legal basis for detention as a proportion of the total

Figure 7.3 and supplementary Table 7.5 show that while the number of children in custody has decreased for all legal basis types over the last ten years, the proportions of these legal basis types have been changing:

-

The proportion of children on remand was 40% in the latest year, nine percentage points higher than the previous year, and higher than Detention and Training Orders for the first time, which is likely due to children spending longer on remand, due to court closures, pauses of jury trials and the subsequent backlogs of court cases in the periods of restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic.

-

Children serving a Detention and Training Order (DTO) have historically made up the largest proportion, but have also seen the largest decrease, from 35% in the year ending March 2020 to 28% in the latest year and is likely due to fewer children being sentenced to custody due to the COVID-19 pandemic, with fewer jury trials taking place and courts being closed for large parts of the year.

-

The proportion of those serving a Section 91 sentence steadily increased from 15% in the year ending March 2011 to 24% in the latest year.

-

The proportion of children on Other sentences continues to make up the smallest share, at 8% in the latest year, although it has increased steadily since the year ending March 2014.

7.4 Offences resulting in children going into custody

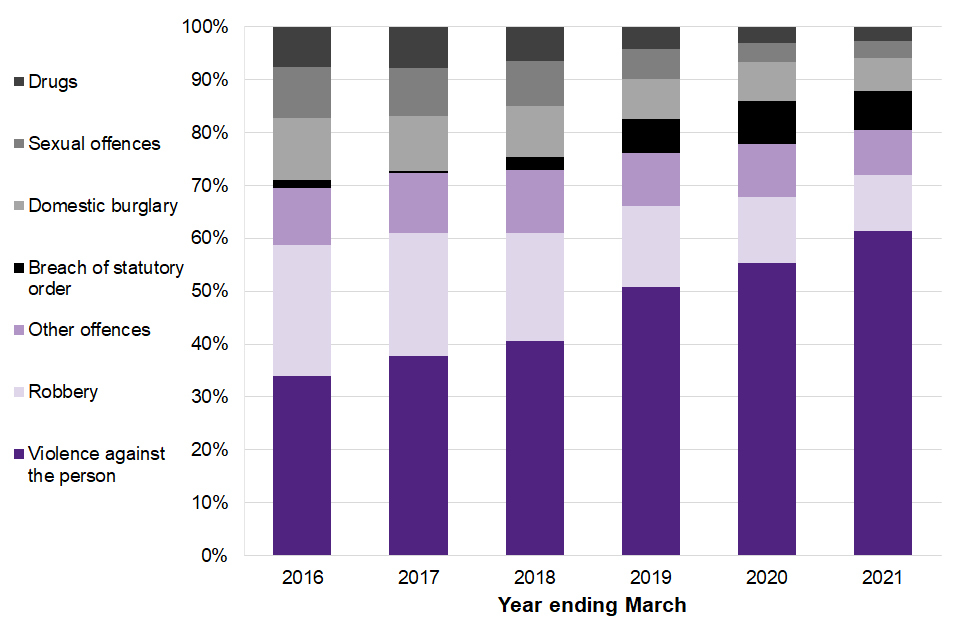

There was a decrease in the number of children in custody across all offence groups compared to the previous year, with the two biggest decreases seen in domestic burglary and robbery, both falling by 40%. This is may be due to more people being at home in the periods of restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic with less opportunity for these types of offences to take place.

Figure 7.4: Proportion of children in custody by offence group, youth secure estate in England and Wales, years ending March 2016 to 2021

Proportion of children in custody by offence group

Figure 7.4 shows that the proportion of children in youth custody for violence against the person offences has continued to increase and accounted for over half (61%) of the youth custody population in the latest year. The proportion of children in custody for robbery meanwhile has more than halved, from 25% to 11% over the last five years.

7.5 Demographics of children in custody

Figure 7.5: Demographics of the youth custody population compared to the general 10-17 population, England and Wales, year ending March 2021

| Aged 10-14 | Aged 15-17 | Boys | Girls | |

| Youth custody population | 3% | 97% | 97% | 3% |

| 10-17 population | 65% | 35% | 51% | 49% |

In the latest year, the majority of children in the youth secure estate were boys (97%), which is broadly similar to the previous year although a slight increase compared with the year ending March 2011 (95%).

Those aged 17 have made up over half of the youth custody population in each of the last ten years and accounted for 61% in the latest year (Supplementary Table 7.10).

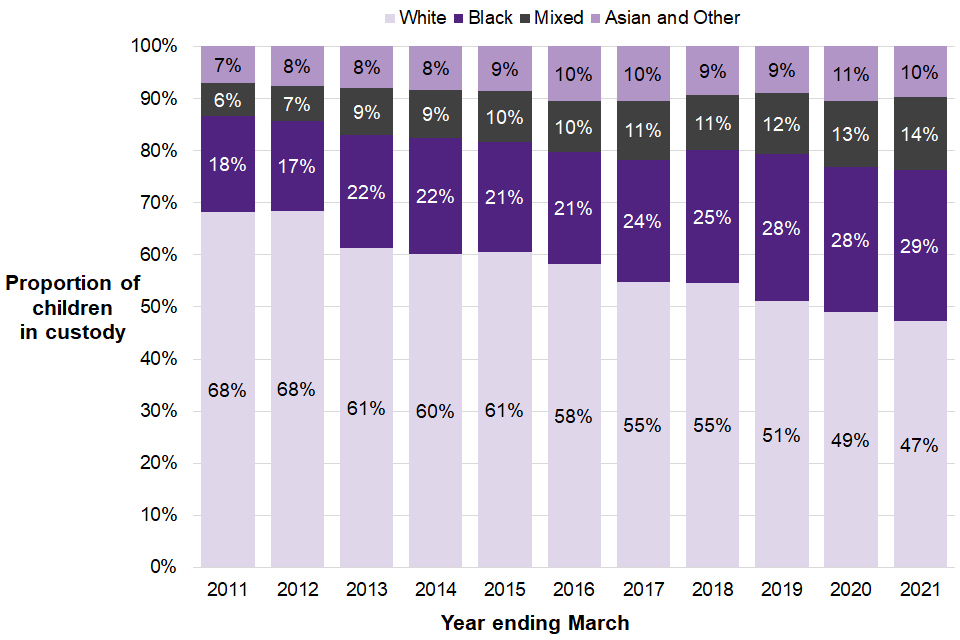

Figure 7.6: Proportion of children in custody by ethnicity, youth secure estate in England and Wales, years ending March 2011 to 2021 [footnote 15]

Proportion of children in custody by ethnicity

While all ethnic groups have seen a decrease in the average custody population over the last ten years as the whole population has decreased, they have been falling at different rates which has led to a change in the proportion each ethnic group comprises.

Figure 7.6 shows that over the last ten years:

-

The proportion of children in youth custody who are White has been falling, from 68% to 47%;

-

the proportion of children from a Black ethnic background has increased the most, and now accounts for 29% of the youth custody population, compared with 18% ten years ago;

-

the proportion of children from a Mixed ethnic background has increased from 6% to 14% over the last ten years; and

-

the proportion of children from an Asian or Other ethnic background has increased from 7% to 10% over the last ten years

Supplementary Table 7.11 shows that in the year ending March 2020, White children made up less than half of the youth custody population (49%) for the first time since the data series began, as they continued to do in the latest year (47%).

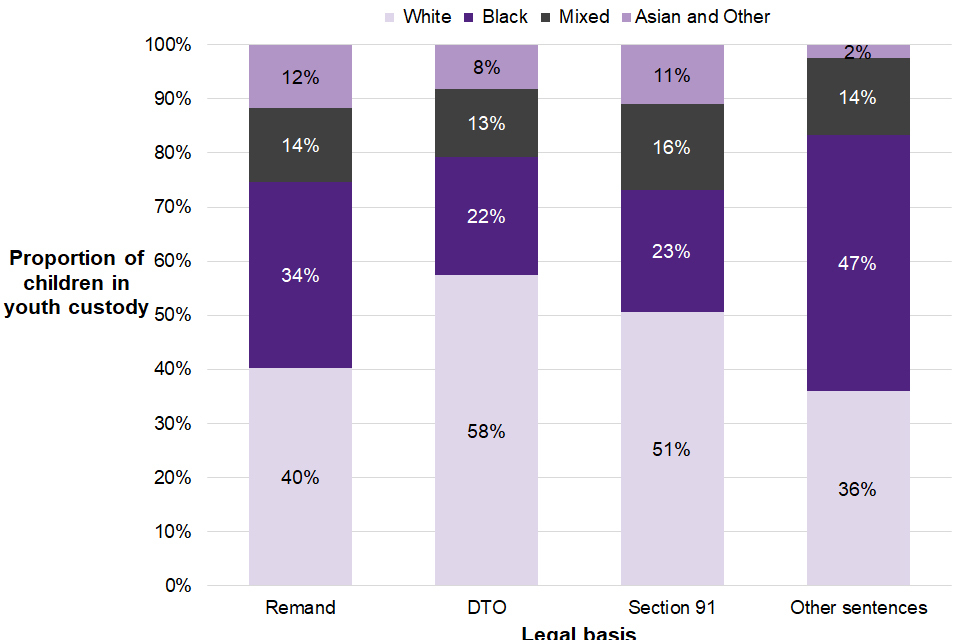

Figure 7.7: Proportion of children in custody by ethnicity and legal basis for detention, youth secure estate in England and Wales, year ending March 2021

Proportion of children in custody by ethnicity and legal basis for detention

Supplementary Table 7.14 shows that the proportions each ethnicity make up by legal basis has been changing over the last ten years:

-

the proportion of children on Other sentences who were Black has seen the greatest increase in the last ten years, from 29% to 47%;

-

the proportion of children on remand who were Black has increased from 25% to 34% in the last ten years;

-

in the last year the proportion of children on remand who were from an Asian or Other ethnic background increased from 9% to 12%, while the proportion of child who were White decreased from 59% to 40%;

-

the proportion of children on DTOs who were from a Mixed ethnic background has more than doubled in the last ten year, from 6% to 13%; and

-

the proportion of children serving a Section 91 sentence who were from a Mixed ethnic background has doubled from 8% to 16% in the last ten years

7.6 Region of home Youth Justice Service (YJS) and distance from home for children in custody

Supplementary Table 7.17 shows that in the year ending March 2021, children who were under the supervision of a London YJS made up the largest share of children in youth custody (28%). This has remained broadly stable in the last ten years.

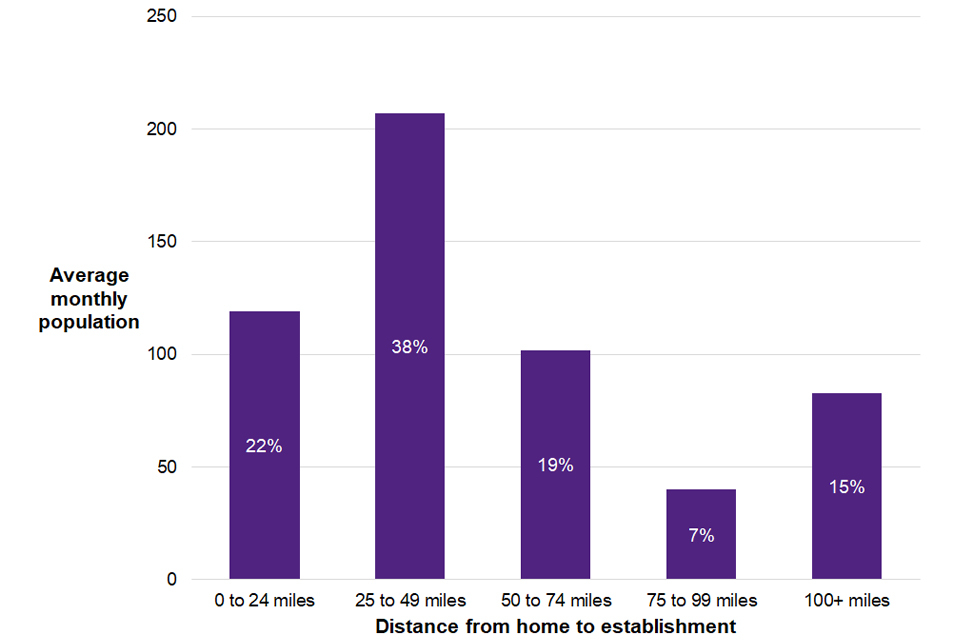

For children in the youth secure estate, the distance between their home address and the secure establishment they are placed in can vary (see Figure 7.8). It is not always possible to place children in an establishment close to their home as placement decisions are determined by a number of factors, including the risks and needs of the individual child and available capacity at establishments.

Figure 7.8:Number and proportion of children in custody by distance from home, youth secure estate in England and Wales, year ending March 2021 [footnote 16]

Number and proportion of children in custody by distance from home

As Figure 7.8 shows, while 59% of children in custody were in an establishment less than 50 miles from their home address, 15% were placed in an establishment 100 miles or more from their home. These proportions are broadly unchanged compared with the previous year.

Length of time spent in custody

7.7 Legal basis episodes ending by nights spent in the youth secure estate

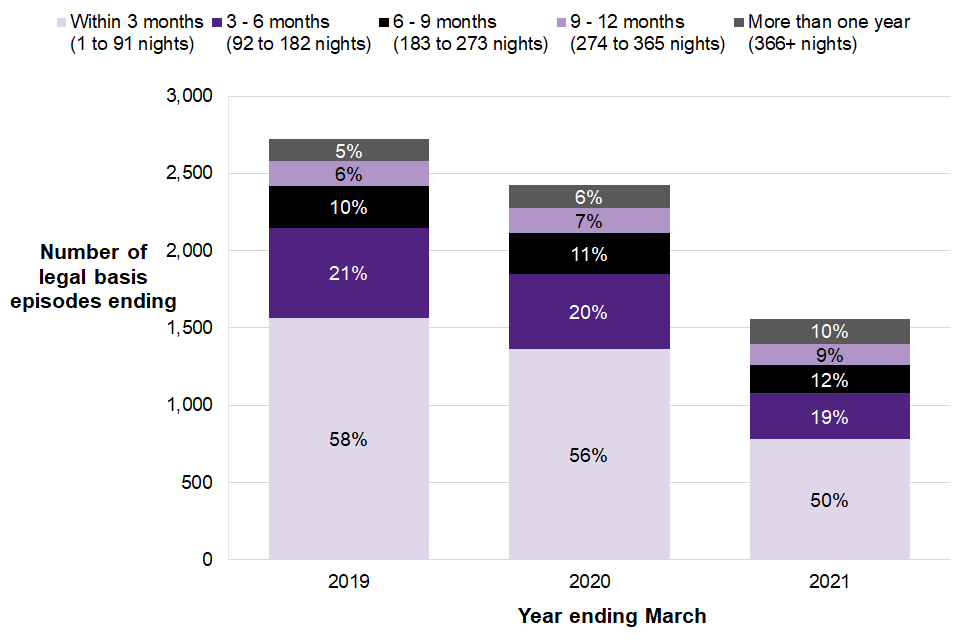

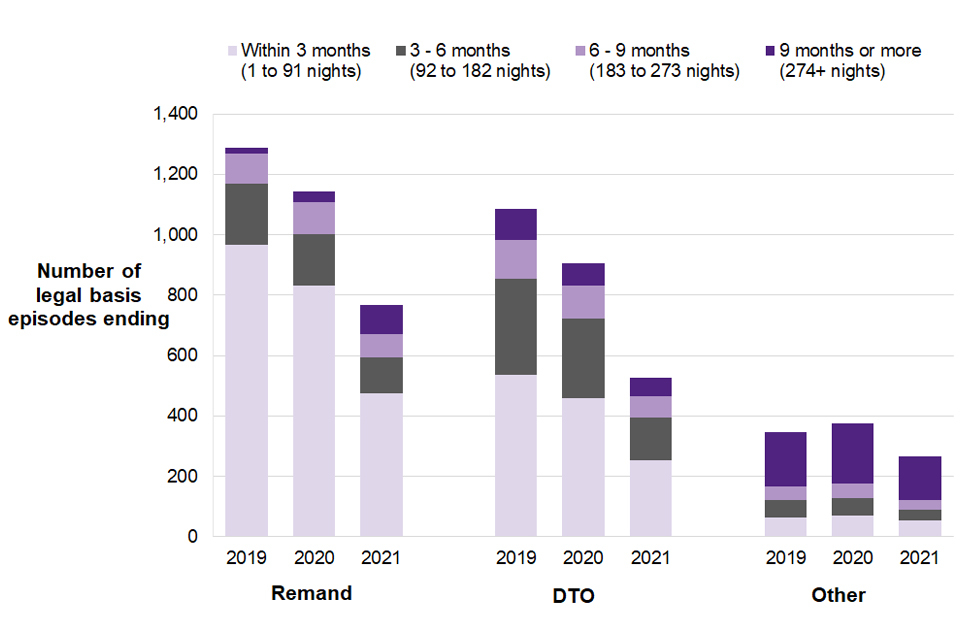

Figure 7.9: Number and proportion[footnote 17] of legal basis episodes ending by nights spent in the youth secure estate in England and Wales, years ending March 2019 to 2021

Number and proportion of legal basis episodes ending by nights spent in the youth secure estate

| 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Median number of nights | 88 | 90 | 91 |

The length of time spent in custody is now recorded by legal basis rather than the length of time in total. Data under this new methodology is only available from the year ending March 2019 and is not comparable with previous publications on length of time spent in youth custody by custodial episode. Please see the Guide to Youth Justice Statistics for further details.

In the year ending March 2021, around 1,600 legal basis episodes in the youth secure estate ended. This was a decrease of 36% compared to the previous year and likely due to the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic where fewer children were remanded and sentenced to custody. Of the 780 legal basis episodes that ended within three months in the latest year, around 100 (13%) ended within seven nights.

In the latest year, around 10% (around 160) of legal basis episodes lasted more than one year which is an increase compared to the previous two years (5% and 6% respectively).

The median number of nights spent in youth custody per legal basis episode was 91 nights in the year ending March 2021. This is an increase of one night compared with the previous year, and of three nights compared with the year ending March 2019.

7.8 Legal basis episodes ending by nights spent in the youth secure estate and legal basis for detention

Figure 7.10: Number of legal basis episodes ending by nights spent in youth custody and legal basis for detention, youth secure estate in England and Wales, years ending March 2019 to 2021

Number of legal basis episodes ending by nights spent in youth custody and legal basis for detention

Remand only episodes

While the overall number of remand episodes has continued to decrease, children are spending longer on remand than in previous years. The median number of nights spent on remand in the latest year was 16 nights longer (37%) than the previous year and 20 nights longer (51%) than the year ending March 2019.

The increases have been, in part, driven by the proportion of episodes ending after 274 nights. In the year ending March 2021, these made up 13% of all remand episodes ending, compared with 3% in the year ending March 2020 and 2% in the year ending March 2019 and is likely an impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on court closures and backlogs.

Detention and Training Order (DTO) only episodes

For those held on a DTO only, most episodes (48%) ended within three months, which is a slight decrease on the previous two years (49% and 51% respectively). In the latest year, a quarter of DTO episodes ended after six months, compared with 20% in the previous year and 19% in the year ending March 2019.

Other

In the latest year, around 270 legal basis episodes that ended were recorded as Other, which includes long term sentences. Around two thirds of these episodes (66%) lasted six months or longer which is broadly similar to the previous two years (64% and 66% respectively).

The median number of nights spent on this type of legal basis was 301 in the latest year, an increase from 294 nights in the previous year and 291 nights in the year ending March 2019.

7.9 Legal basis episodes ending by nights spent in the youth secure estate and ethnicity[footnote 18]

In the latest year, the number of legal basis episodes ending for White children was around 770, a decrease of 38% from the previous year, compared with around 780 episodes ending for children from ethnic minorities, which had a smaller decrease of 33% from the previous year.

Figure 7.11: Proportion[footnote 19] of legal basis episodes ending by nights spent and ethnic group, youth secure estate in England and Wales, year ending March 2021

| Number of nights | 1-91 | 92-182 | 183-273 | 274-365 | 366+ |

| Ethnic minorities | 48% | 21% | 11% | 9% | 11% |

| White | 52% | 17% | 13% | 9% | 10% |

As shown in Figure 7.11, over two thirds (69%) of custodial episodes ended within six months for both White children and children from ethnic minorities, though the number of episodes ending between three and six months was four percentage points higher for children from ethnic minorities than White children. The other proportions were broadly similar.

7.10 Deaths in youth custody

In the year ending March 2021, no children died in custody in the youth secure estate. Between the years ending March 2010 and 2020, there were seven deaths in youth custody (see the formal Prisons and Probation Ombudsmen Reports).

8. Behaviour management in the youth secure estate

In the year ending March 2021:

-

The number of incidents per 100 children and young adults in the youth secure estate across all behaviour management measures decreased from the previous year. Changes to custodial regimes, including longer time in rooms and staff shortages during the COVID-19 pandemic are likely factors in these reductions.

-

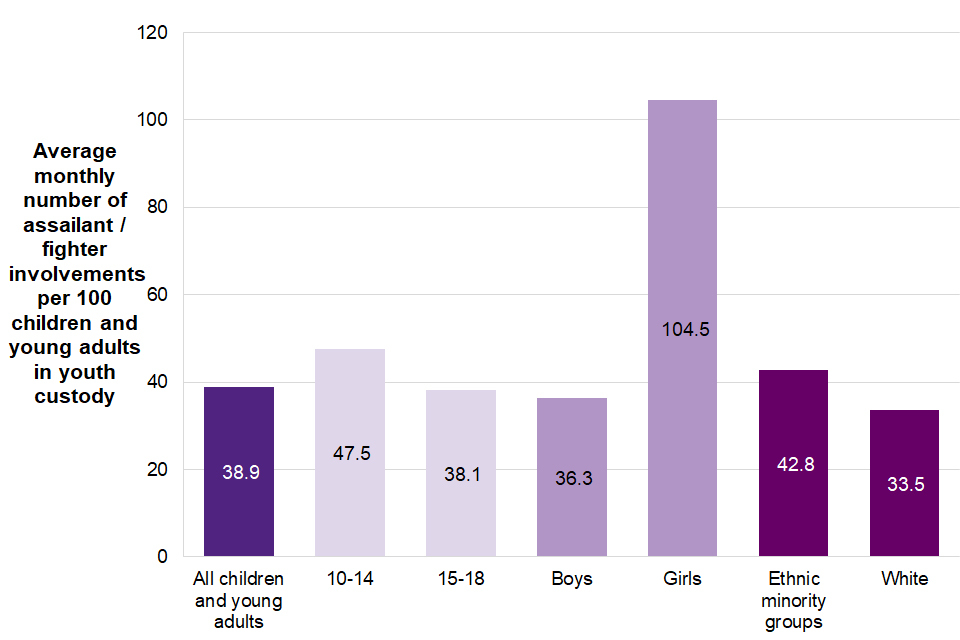

The number of incidents of assault per 100 children and young adults in the youth secure estate has seen the largest decrease of the four behaviour management measures, decreasing by 26% in the last year to 38.9 incidents per month.

-

The number of Restrictive Physical Interventions (RPIs) per 100 children and young adults in the youth secure estate fell by 24% to 55.0 incidents per month. This reverses year-on-year increases seen in the previous four years.

-

The number of incidents of self-harm per 100 children and young adults in the youth secure estate decreased by 23% in the last year to 18.6 incidents per month. This also reverses the year-on-year increases seen in the previous five years.

-

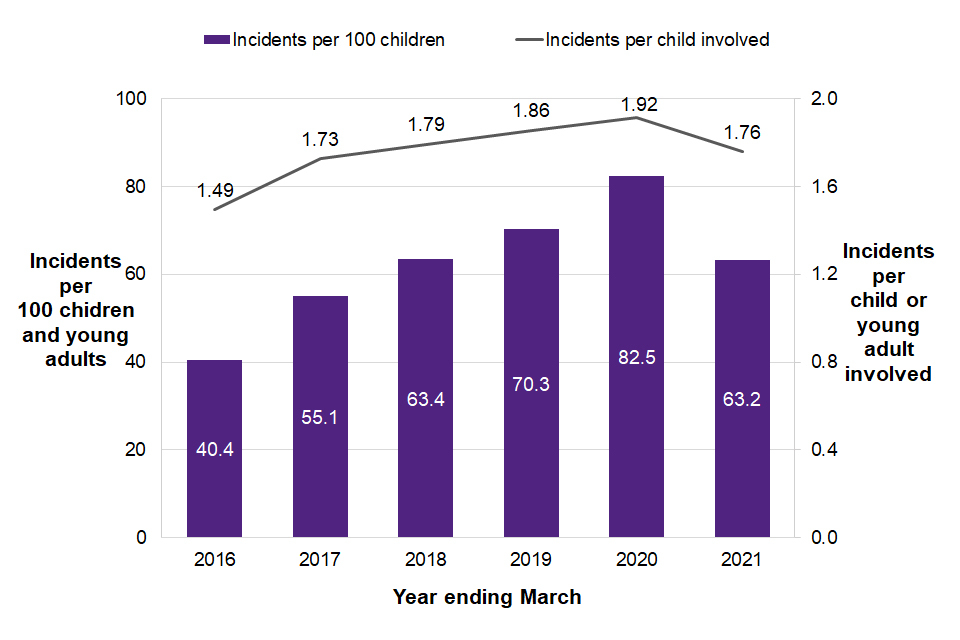

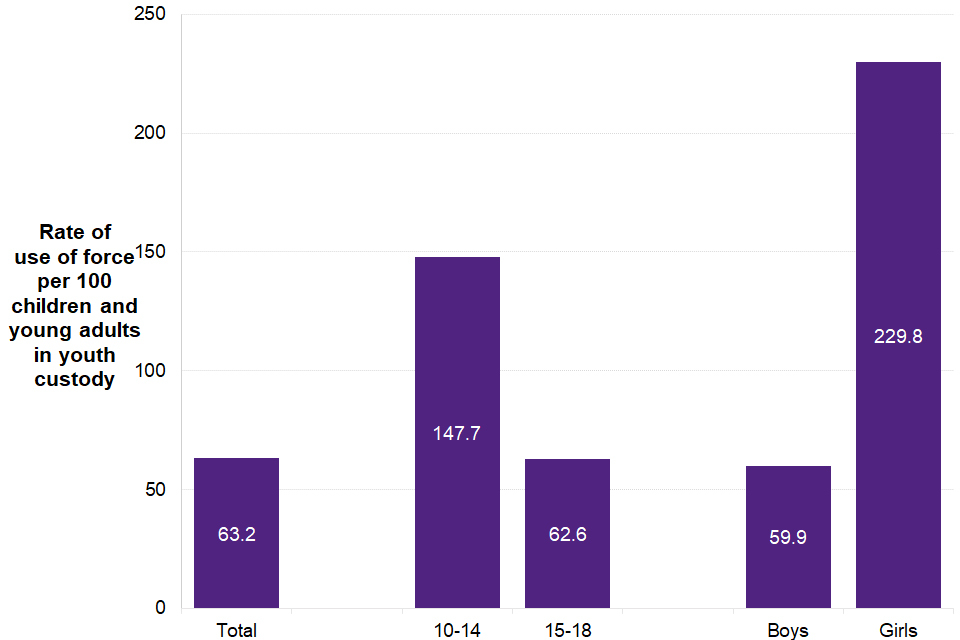

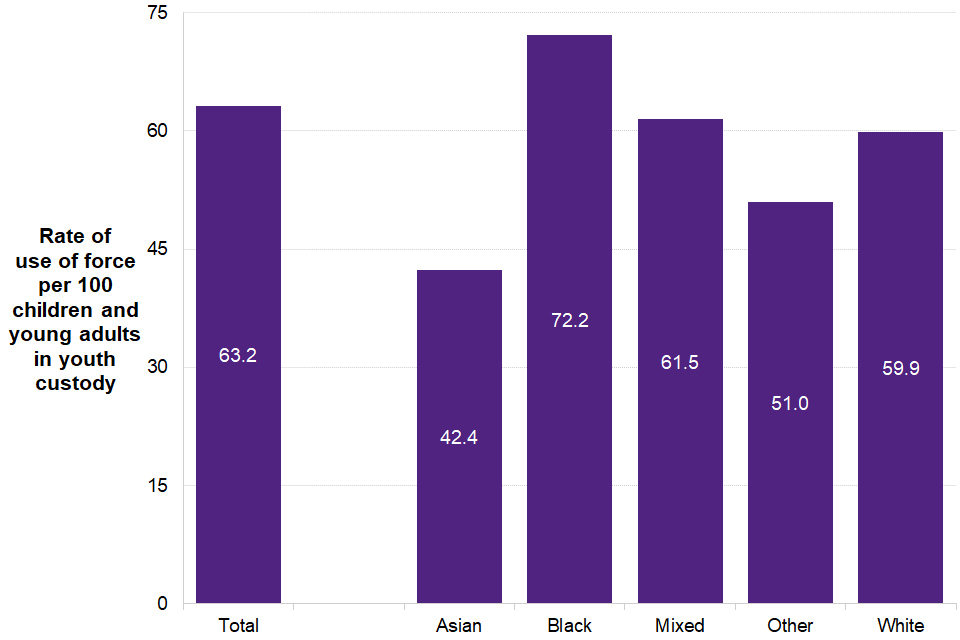

There was an average of 63.2 use of force incidents per 100 children and young adults across the two Secure Training Centres and five Young Offender Institutions, decreasing 23% from the previous year.

This chapter presents data on trends of behaviour management incidents by type and use of force in the youth secure estate by demographic characteristics. It includes 18 year olds still in the youth estate, so the term ‘children and young adults’ is used throughout, but only includes those held in the youth secure estate.

The COVID-19 pandemic in the youth secure estate will have impacted on the number and rate of incidents in the latest year. As well as falling numbers of children in custody, changes to regimes including shorter time out of rooms and reduced staffing levels due to sickness or self-isolation will have contributed to these changes.

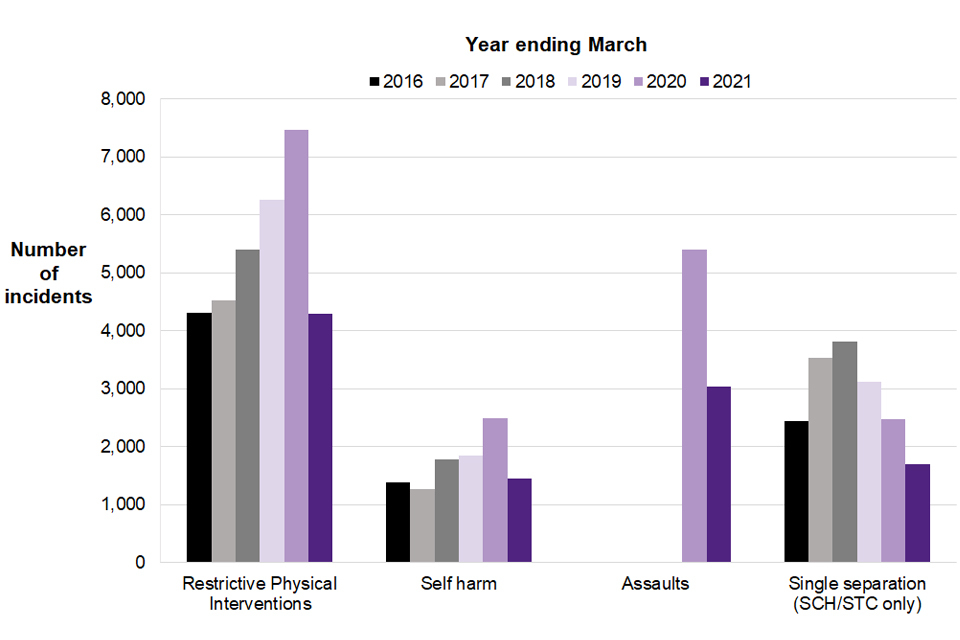

8.1 Trends in the number of behaviour management incidents

Figure 8.1: Trend in the number of behaviour management incidents, youth secure estate in England and Wales, years ending March 2016 to 2021

Trend in the number of behaviour management incidents

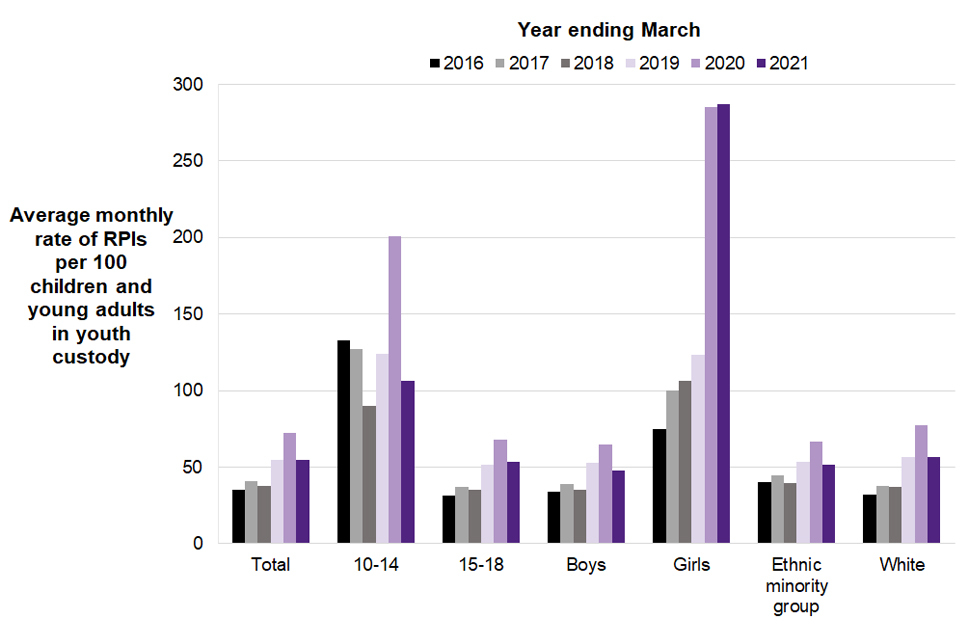

8.2 Use of Restrictive Physical Interventions (RPIs) in the youth secure estate

As shown in Figure 8.1, in the year ending March 2021 there were just under 4,300 RPIs, down 42% compared with the previous year. This reverses the upward trend seen over the last four years and is the lowest number of RPIs in the last five years.

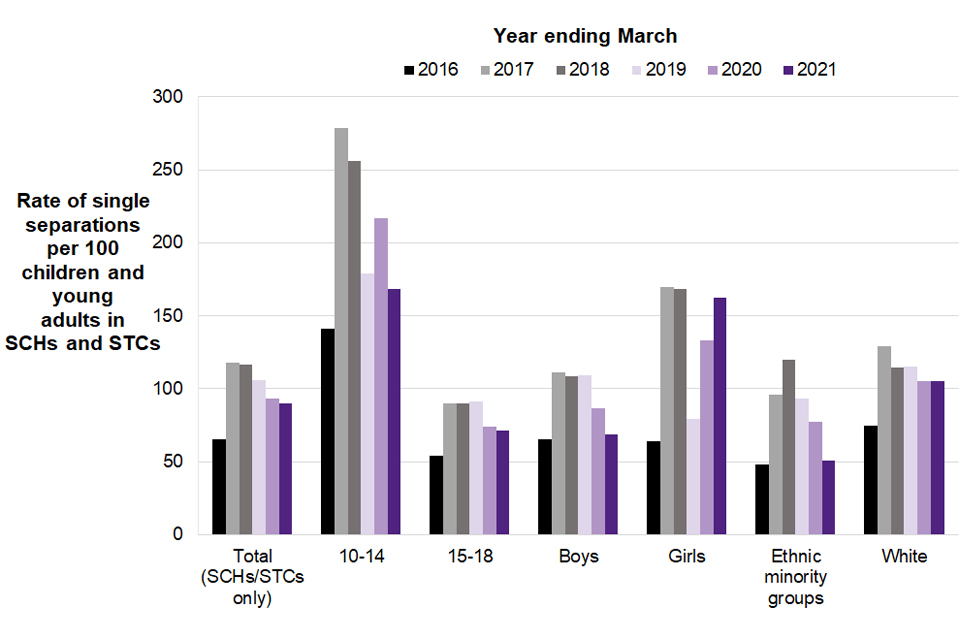

As with the number of RPIs, the average monthly rate of RPIs per 100 children and young adults in the youth secure estate has also decreased for the first time in the last five years. In the latest year, the average monthly rate of RPIs per 100 children and young adults in the youth secure estate was 55.0, a decrease from the previous year (72.4). As shown in Figure 8.2, decreases in the rate of RPIs were seen in all demographic groups except for girls, which saw a minor increase.

The average number of RPI incidents per month per child or young adult involved has also decreased over the last year to 1.9 from 2.0 in the previous year, reversing the trend of year-on-year increases over the years from 1.5 in the year ending March 2015 to March 2020 (Supplementary Table 8.3).

These reductions, following previous years’ increases, should be viewed in the context of restrictions introduced as a response to COVID-19. Children and young adults in custody, being subject to these restrictions, were less able to leave their rooms and to mix communally than would have been expected pre-COVID-19. As a result, occasions on which incidents of restrictive physical intervention may have been needed were also reduced. Also, staff absences may have had an effect on the level of staffing available in establishments to carry out interventions.

Figure 8.2: Average monthly rate of RPIs per 100 children and young adults in custody by demographic characteristics, youth secure estate in England and Wales, years ending March 2016 to 2021

Average monthly rate of RPIs per 100 children and young adults in custody by demographic characteristics

Figure 8.2 shows that in the year ending March 2021 the average monthly rate of RPIs per 100 children and young adults in custody was higher for:

-

Those aged 10-14 (an average monthly rate of 106.3 per 100 children compared to 53.6 for children and young adults aged 15-18) as has been the trend since the time series began;

-

Girls, at 287.4 compared to 47.6 for boys – the rate for girls has seen year-on-year increases every year since the year ending March 2015 and is now over four times the rate in that year.

-

White children and young adults (at 56.7 compared to 51.8 for children and young adults from ethnic minority groups). This is the third consecutive year that the rate has been higher for White children and young adults than those from ethnic minority groups but the difference in rate is smaller than in the previous year.

Figure 8.3: The number of injuries requiring medical treatment to children and young adults by severity of injury resulting from an RPI, youth secure estate in England and Wales, years ending March 2016 to 2021

| Severity of RPI injury requiring medical treatment | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

| Minor injury requiring medical treatment on site | 84 | 92 | 76 | 54 | 79 | 34 |

| Serious injury requiring hospital treatment | 3 | 8 | 2 | 7 | 3 | 7 |

| Total injuries requiring medical treatment | 87 | 100 | 78 | 61 | 82 | 41 |

| Proportion of RPIs that resulted in an injury requiring medical treatment | 2% | 2% | 1% | 1% | 1% | 1% |

In the year ending March 2021, the number of RPIs resulting in medical treatment halved compared to the previous year and 1% of all RPIs resulted in injuries requiring medical treatment. This proportion is unchanged from the previous year and has remained broadly stable for the last four years (Supplementary Table 8.7).

As shown in Figure 8.3, there were 41 RPIs that resulted in an injury requiring medical treatment, of which:

-

Most (83%) were minor injuries requiring medical treatment on site; and

-

Seven incidents (17%) were serious injuries requiring hospital treatment.

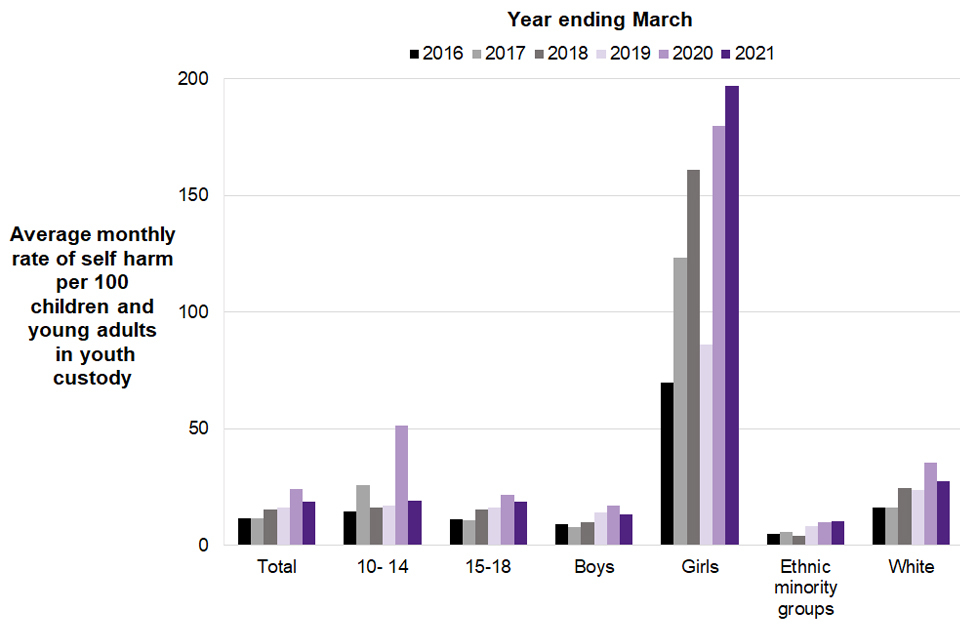

8.3 Self harm in the youth secure estate

The number of self harm incidents has decreased by 42% in the latest year, to around 1,500 incidents and is the lowest number of incidents seen since the year ending March 2017. (Figure 8.1).

The average monthly rate of self harm incidents per 100 children and young adults in custody has decreased for the first time since the year ending March 2015, after five successive year-on-year increases.

In the latest year, there was an average of 18.6 self harm incidents per 100 children and young adults in custody per month, down from 24.2 in the previous year but still nearly double the rate of five years ago (11.4).

The average monthly rate of self harm incidents per child and young adult involved is the joint highest, it has been in the last five years along with the previous year, at 2.8, the same as the previous year but higher than five years ago (1.9).

Figure 8.4: Average monthly rate of self harm incidents per 100 children and young adults in custody by demographic characteristics, youth secure estate in England and Wales, years ending March 2016 to 2021