User guide to diversity of the judiciary statistics

Updated 8 September 2023

Applies to England and Wales

1. Introduction

This guide accompanies the fourth edition of the combined statistical report, published in July 2023. It covers statistics presenting data on diversity for current judicial office holders, for judicial applications and appointments and within the legal professions which provide the eligible pool of candidates for most judicial roles. These were first published together in a combined report in September 2020, and are now published annually.

These statistics are designated as Official Statistics, indicating that they are fit for purpose and are produced in compliance with the Code of Practice for Statistics, in accordance with the Statistics and Registration Service Act 2007.

This designation can be broadly interpreted to mean that the statistics meet identified user needs, are well explained and readily accessible, are produced according to sound methods; and are managed impartially and objectively in the public interest.

This user guide provides a brief background about the judiciary and also includes information on:

- users and uses of the statistics

- data sources and methodology

- the quality of the statistics

- changes made to the statistics and plans for future development

- links to other related statistics

- a glossary of terminology

- other explanatory notes

2. Background to judicial diversity statistics

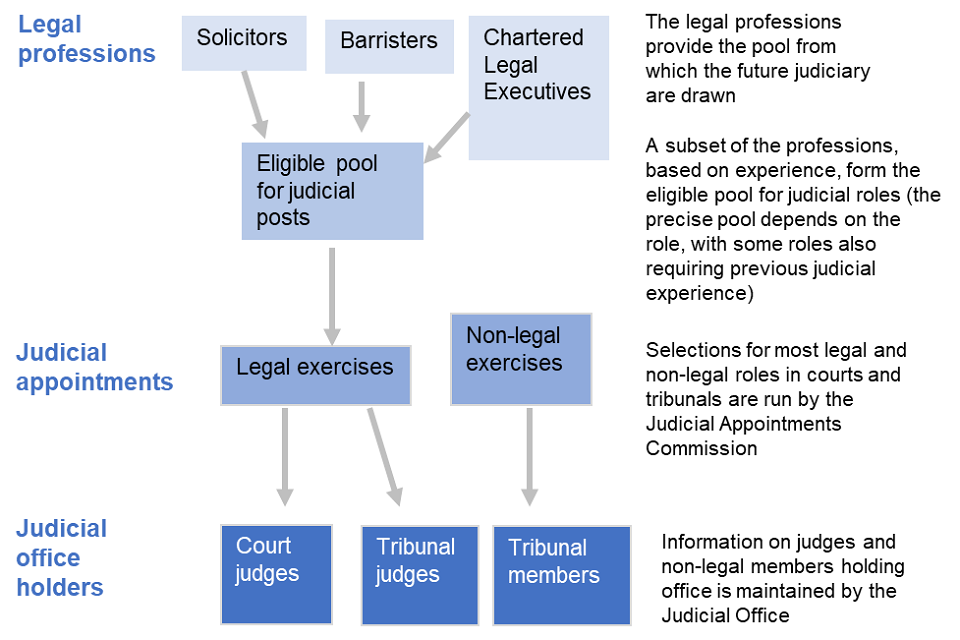

These statistics bring together information about the diversity for the current judiciary in England and Wales, during selection for judicial roles, and in the legal professions which provide the pool of eligible candidates for most judicial posts requiring legal experience (see Figure 1).

While the focus of the statistics is on diversity, they also provide a snapshot count of the number of judicial office holders.

A key aim of this publication is to bring together data into one place that before 2020 was published separately. In doing so, it provides a comprehensive picture of the data available and evidence gaps.

Figure 1: Information about becoming a judge and the data owners

Much of the diversity data included in this publication depends on voluntary self-declaration by legal profession members, judicial post applicants and judicial office holders. All percentages are calculated using the proportion of individuals where the characteristic is known. A characteristic is considered to be ‘unknown’ if an individual has chosen ‘prefer not to say’, or has left the answer blank. For intersections of multiple characteristics groups, individuals in the ‘unknown’ group are those that were ‘unknown’ for one or more of the characteristics being intersected.

2.1 The judiciary in England and Wales

The statistics provide an overview of the diversity of appointed court judges, tribunal judges, non-legal members of tribunals and magistrates. Figures are published on an annual basis, taking a snapshot of the staffing position as at 1 April of each year. An explanation of judicial roles is available from the judiciary website: www.judiciary.gov.uk/about-the-judiciary/who-are-the-judiciary/judicial-roles/

The Judicial Career Progression chart provides an overview of progression through the judiciary in England and Wales : www.judiciary.gov.uk/about-the-judiciary/judges-career-paths/judicial-career-progression-chart/

As from the 2023 report information about the recruitment of magistrates and their diversity characteristics has been included.

2.2 Judicial appointments

The Constitutional Reform Act 2005 (CRA) enshrined in law the independence of the judiciary and changed the way judges are appointed. As a result of the Act, the Judicial Appointments Commission (JAC) was set up in April 2006 to make the appointments process clearer and more accountable. Under the CRA, the JAC’s statutory duties are to:

- select applicants solely on merit

- select only those with good character

- encourage a diverse range of applicants

As part of its diversity strategy, the JAC publishes the diversity profile of applicants at application, shortlisting and recommendation stages.

Shortlisting: Shortlisting is the process used by the JAC to determine who is invited to attend a selection day. The main tools used, either together or separately, are currently:

- An online qualifying test, more likely to be used when the volume of applications is large, or

- A paper sift, which considers applicants’ self-assessment and other information (for example, independent assessments) and is more likely to be used for those exercises with a smaller number of applicants.

These tools may be used in conjunction with other shortlisting tools, such as a telephone assessment or written scenario test. The same types of selection tool are used for both legal and non-legal exercises. On rare occasions, when applicant numbers are very low, no shortlisting process is undertaken and all eligible applicants are invited to attend a selection day, which will involve an interview and may also involve situational questioning, a leadership presentation or role play.

Recommendations: Before making recommendations to the Appropriate Authority, the Commissioners of the JAC, sitting as the Selection and Character Committee, first assure themselves that applicants are ‘of good character’. The Selection and Character Committee then makes selection decisions based on the panel’s assessment of all the available evidence, and the result of statutory consultation with the judiciary. The Lord Chancellor, Lord Chief Justice or Senior President of Tribunals can reject a recommendation, although do so only on a very exceptional basis.

The JAC makes recommendations under section 87 of the Constitutional Reform Act 2005 (CRA). Recommendations are for a confirmed vacancy. If accepted by the Appropriate Authority, they are guaranteed to be offered appointment.

The JAC may also be asked to identify persons suitable for later selection under section 94 of the CRA (also referred to as ‘recommended to a list’). Those identified by the JAC are regarded as suitable for future appointment to specific roles if, and when, an appropriate vacancy arises. Those applicants are not guaranteed an offer of appointment. Applicants recommended under section 87 and 94 CRA are reported separately in the published statistical tables. In addition, if a vacancy subsequently becomes available for a post for which a selection exercise has recently been carried out, the JAC can make an additional recommendation using the results of that recent exercise. This is the case even if there are no applicants identified following a section 94 exercise for the specific location and/or jurisdiction.

Senior appointments: The JAC is responsible for running selection exercises for posts up to and including the High Court. It also has statutory responsibilities to respond to requests from the Lord Chancellor to convene panels that recommend applicants for appointment to other senior posts. These include the Lord Chief Justice, Heads of Division, and Lord Justices of Appeal. The JAC provides the secretariat for these exercises and, in line with statute, at least 2 JAC Commissioners sit on each 5-member panel.

While senior appointment selection panels are required to determine their own processes, selection exercises may include an application (form or letter), independent assessments, self-assessment, non-statutory consultation (seeking feedback on applicants from the senior judiciary and others), a sift and selection interviews.

From 2015-16, information on senior exercises has been included in these statistics (although figures are shown separately from the overall totals).

Quality assurance in selection: The JAC uses quality assurance checks throughout the selection process to ensure proper procedures are followed, standards are maintained and all stages of selection are free from bias. This includes:

- reviewing selection exercise materials, and observing dry-runs of role plays and interviews

- monitoring the progression of candidate groups at key stages in the selection process

- carrying out equality impact assessments on all significant changes to the selection process and

- making reasonable adjustments for applicants who need them

2.3 Legal professions

To become a judge, some degree of legal experience is required. This publication includes data for barristers, solicitors and Chartered Legal Executives. While it is not essential to be a current member of one of these professions to apply for judicial roles, in practice most of those who apply will have a background in at least one of these professions.

Solicitors, barristers and Chartered Legal Executives comprise very different populations and professions. Their population sizes are highly varied, as are their members’ qualification, progression and employment processes, eligibility and potential interest in applying for, and consequent representation in, the judiciary. As a result, caution is advised in making comparisons between different professions, and with the JAC and Judicial Office data. In particular, Chartered Legal Executives are unable to apply for judicial roles requiring 7 or more years legal experience[footnote 1].

-

Solicitors: all practising solicitors i.e. those who hold a practising certificate (PC) who provide general and specialist advice on a variety of issues, and some may represent their clients in court. They can work together with others in private practice or in government departments or commercial businesses. The professional body representing solicitors is the Law Society, and the profession is regulated by the Solicitors Regulation Authority(SRA). Solicitors wishing to carry out reserved legal activities must have in force a practising certificate issued by the SRA (or a relevant exemption). Individuals who have qualified as a solicitor and are on the roll of solicitors do not need to hold a practising certificate to apply for judicial office.

-

Chartered Legal Executives: all Chartered Legal Executives hold Practising Certificates. They are specialist lawyers who provide specialist legal advice on a number of issues. They work in private practice, commercial businesses, charities and Local and Central Government. The professional body representing Chartered Legal Executives is the Chartered Institute of Legal Executives (CILEX) and they are regulated by CILEx Regulation. Chartered Legal Executive is the regulatory title. A Chartered Legal Executive will also hold a practising certificate, and will be a CILEX Fellow. However, there are additional membership grades of: Fellow - Maternity/Paternity, Fellow – Non Practising (which includes retired Fellows), and Fellow – Dual Qualified (which is Fellows who have remained in membership, but have gone on to qualify, usually as a solicitor or licensed conveyancer). All of these grades of Fellows are included in the data used for the annual report, but they will not all be current practising Chartered Legal Executives.

-

Barristers: all practising barristers (those who hold a PC) who are specialists in certain legal fields that solicitors can instruct on behalf of their client to appear in court. The professional body for barristers is the Bar Council, and the regulatory body is the Bar Standards Board. In order to practise as a barrister, an annual practising certificate is required to carry out reserved legal activities. Barristers can be broken down into King’s Counsel (KC) barristers and junior barristers[footnote 2]. King’s Counsel is an office, conferred by the Crown, that is recognised by courts and is awarded for excellence in advocacy (although guidelines for award note it is unlikely that an applicant will have acquired the necessary skills and expertise for appointment without extensive experience in legal practice).

The oversight regulator of legal services in England and Wales is the Legal Services Board, which is independent from both the legal professions and government.

3. Data sources, coverage and definitions

3.1 Data sources

Judicial office holders

Data are a snapshot taken from the judicial HR database (as of April 2023). This contains details of each judicial office holder (judges, non-legal members and magistrates), including diversity characteristics.

Up to 2019-20, diversity characteristics, including ethnicity, were recorded as self-declared by judicial office holders at time of entry into the judiciary and not changed unless the information was specifically provided to judicial HR teams. However, from 2019/20, judges in courts and tribunals have been able to enter and edit their own diversity information, allowing them to ensure it is up to date and accurate. Additional diversity information (such as religion and sexual orientation) is now being collected, though declaration rates are not yet sufficient for publication.

Judges are given the option to decide not to declare any of their diversity information at any point via the option to ‘Prefer not to say’ and thus opt out of providing us their data, ensuring compliance with the General Data Protection Regulation. This impacts on the presentation of diversity information within these statistics[footnote 3].

Magistrates recruitment

In January 2022, an updated magistrates’ recruitment process was launched. This introduced a new applicant tracking system (ATS) which provides consistent, centralised data collection for magistrate recruitment across England and Wales and much wider diversity data on applicants and appointments to the magistracy.

Judicial appointments

In January 2020, the JAC replaced its legacy administrative data system JARS (Judicial Appointments Recruitment System) with a new digital platform. Both systems operated in tandem for a period to allow exercises that launched on JARS to draw to a conclusion. For exercises that launched prior to January 2020 and concluded in 2020-21, data is taken from JARS. For all exercises that launched January 2020 onwards, data is taken from the new platform. Both systems store candidate data which is subject to specific legislative provisions set out in the CRA, the Data Protection Act 2018 and Freedom of Information Act 2000. User access is strictly controlled and trail logs are kept for security checks and audit purposes.

Data from the JAC’s diversity monitoring form (which is part of the broader application form) are used to produce reports and to support statistical analysis. Completing the diversity monitoring form is not compulsory and not all applicants make diversity declarations on some or all items within the form. The form includes questions regarding sex, ethnicity, professional legal background, disability, age, socio-economic background, sexual orientation and religious belief.

Within the applications system on JARS, individuals were free to update their diversity data. For these statistics, diversity data are as captured at the point of download from the system (usually close to the date at which the exercise was completed following recommendations for appointment). Diversity data on the new platform cannot be amended by candidates following submission of their application.

Legal professions

Data for the legal professions are taken from administrative data systems used for the purposes of managing membership lists and certification. Figures for inclusion in this publication are provided in aggregate format and published in the form supplied. They have been provided for this publication specifically and may not match diversity data which is published separately by the professional bodies. For example, figures for solicitors used here differ from the published firm diversity data, which is collected by law firms and published by the SRA based on a slightly different subset of the population. They represent a snapshot of the position as at 1 April 2023. For the 2023 report, legal professions were requested to provide historical data back to 2014 in order to produce the new time series table.

Barristers: Data are provided by the Bar Standards Board (BSB), and cover all practising barristers i.e. those that hold a practising certificate.

Solicitors: Data are provided by the Solicitors Regulation Authority (SRA), and cover practising solicitors (those holding practising certificates) excluding Registered European Lawyers (RELs) and Registered Foreign Lawyers (RFLs)[footnote 4]. The practising population is different from the regulated population which includes all solicitors on the roll i.e. solicitors who qualified but do not have a current practising certificate and is therefore a larger group[footnote 5].

Chartered Legal Executives: Data are provided by CILEX from their membership database. Figures relate to all those who have achieved Fellowship of CILEX, so excludes those who are Students, Paralegals and Advanced Paralegals, and those in the affiliate grade of membership. Data is collected on initial registration and through a private member portal each year on renewal of membership where members are required to update their equality and diversity data.

3.2 Coverage and definitions

Judicial office holders

Coverage: These statistics broadly cover the judiciary in England and Wales[footnote 6]. For courts and magistrates, figures cover only England and Wales. Tribunals figures include all tribunals administered by HMCTS and Welsh Tribunals not administered by HMCTS. This includes Employment Tribunal in Scotland, in addition to Tribunals in England and Wales. Tribunals that are the responsibility of the devolved Welsh Government are not included.

Count of appointments: The focus of this bulletin is diversity, and accordingly the figures within the bulletin relate to individuals, and not to the posts held.

- Where a judge holds more than one appointment[footnote 7], the statistics are compiled for the appointment considered to be their primary appointment, i.e. the appointment they hold most of the time. There are a small number of posts that are by definition not primary appointments, for example Upper Tier Tribunal President and Employment Appeal Tribunal President. The post-holders are included only in the counts for their primary appointment, meaning that for these posts statistics are not presented.

- Figures are on a headcount basis, and do not reflect the full-time equivalent (FTE) value of part-time salaried judicial post holders (to do so would be to understate representation among part-time individuals). Similarly, for those in fee-paid roles, figures count individuals, not posts held nor appearances in court.

- All figures relate to the position as at 1 April of the relevant year.

New appointments and leavers: From 2018-19 onwards, statistics have been published for entrants to, and leavers from, the judiciary.

- New appointments include those who started their first appointment, have been promoted from fee-paid to salaried or have had a promotion from a salaried post to a higher salaried post. Judges or members changing appointment, such as extension, change of jurisdiction or returning to sit in retirement are excluded. These are further broken down into:

- New entrants (i.e. those taking up their first judicial role). Judicial office holders may take up a new appointment while in office; new entrants are counted as those starting a new appointment who did not hold another appointment at the start of the financial year. Although judicial office holders can have multiple appointments, they are counted on a head count basis and so will only be counted once by their primary appointment.

- Promotions from one judicial role that happened in the last financial year, either from fee-paid to salaried or from a salaried post to a higher salaried post. In the tables presenting diversity breakdowns for promotions, figures for fee-paid posts are 0.

- Leavers count those leaving the judiciary for any reason (including retirement, resignation, death in service and removal by the Lord Chancellor)[footnote 8]. As judicial office holders can hold more than one appointment, they are only counted when they leave their primary appointment and hold no other appointments.

Contract type: The bulletin provides breakdowns of fee-paid, salaried and salaried part-time judges and non-legal members of tribunals[footnote 9]. For both courts and tribunals, fee-paid positions are paid according to the number of sittings or days worked. The number of sitting days varies depending on the type of appointment, and will generally be at least 15 days a year. These judge and non-legal member figures exclude those who are solely sitting in retirement as a fee-paid judge, as sitting in retirement information has been included in the report as from 2023.

Judges sitting in retirement: Sitting in retirement is the policy which currently permits certain judges to retire, draw their pension, and continue to sit as a fee-paid judge, if there is a business need to do so, up to the mandatory retirement age of 75.

Magistrates recruitment

Coverage: The new applicant tracking system data collects data for magistrate recruitment across England and Wales. However, magistrates recruitment is an ongoing process that does not always conclude within a 12 month window, and will differ across regions and Advisory Committee areas. As such, any recruitment data, particularly in regards to recruitment stages should be caveated with this understanding - that it is live data and therefore some figures published as at 1 April in a given year are likely to change in future publications as more information is recorded on the system.

Judicial appointments

Exercises included: The statistics cover all selection exercises run by the Judicial Appointments Commission which have closed in a given one-year or three-year period, although any which are run for the Welsh Government (under the Government of Wales Act) are excluded, and figures for senior selections (for Court of Appeal and above) are shown separately.

The JAC makes recommendations for appointment to one of three Appropriate Authorities (the Lord Chancellor, Lord Chief Justice or Senior President of Tribunals). For the purpose of presenting information in the Official Statistics bulletin, the date of the report to the Appropriate Authority marks the point at which the JAC’s involvement in the selection exercise is considered to have ended. Those exercises for which recommendations have been considered by the Appropriate Authority within the financial year are included within the annual statistics[footnote 10].

In the event that a recommended candidate approved by the Appropriate Authority subsequently turns down the offer of a post, further recommendations may be made to fill the vacancy request. Where additional recommendations come from the same pool of candidates who applied initially and are appointed within the financial year, these will also be reported in addition to those made previously. Should further recommendations be made after the end of the financial year, these will not be included within the annual statistics. However, in the event of 10 or more additional recommendations being made in any single selection exercise after the end of the financial year, the additional recommendations may be published in the following year’s statistics bulletin.

The bulletin presents information on the outcome of selection exercises by the date of the report to the Appropriate Authority. This has implications for revisions (see section on revisions).

Applications: In selection exercises prior to December 2012, applicants were screened to ensure they met the eligibility criteria when they first applied. Ineligible applicants did not continue through to the next stage of the selection process. For exercises that completed from October 2013, information regarding applicants relates to all those who applied for a particular post, regardless of eligibility. The number of applicants excluded because of eligibility concerns is generally low, largely confined to entry-level roles and should, in most cases, make little substantive difference. However some caution should be taken when comparing the profile of applicants in exercises carried out at different times for this reason.

Where there are vacancies for two or more posts which are run as a single selection exercise[footnote 11] figures presented refer to individual applicants on a headcount basis, as opposed to the number of applications. Candidates may apply for both posts but would only participate in the exercise once. However, where the same person applies for selection through different selection exercises, each application is counted.

Recommendations: On rare occasions where a recommendation made by the Appropriate Authority is rejected, the JAC would make a further recommendation to the Appropriate Authority in line with legislation. If this occurred prior to the publication of the statistics they would be included in the published figures, unless timescales make inclusion impractical. If following publication, then any amendment to the published statistics would be considered a revision (see section on revisions).

Where a vacancy subsequently becomes available for a post for which a selection exercise has recently been carried out, any additional recommendations made prior to the end of the reporting year would be included within the published statistics (and, otherwise, would be included in the subsequent bulletin).

Recommendations from JAC selection exercises will not directly correspond to new entrants to the judiciary also covered in the publication, as there is a lag between selection exercises being completed and individuals taking up their post, and some will already have held a judicial role (often fee-paid).

Eligible Pool:(EP) The eligible pool provides context for the diversity statistics of different selection exercises. It presents the sex, ethnicity and professional background of everyone who meets the minimum formal eligibility criteria and certain additional selection criteria for a post. It should be noted that just because a candidate is included in the eligible pool, this does not mean they have a desire to apply for a given role, nor that they have the relevant talent and experience needed.

The data relating to the sex, ethnicity and professional background of the eligible pool is collated from data provided by the legal professions and the judiciary on the basis of the selection exercise eligibility criteria. Eligibility for judicial selection varies from one exercise to another, and with the exception of specialist posts, the criteria fall into four main categories:

- statutory requirement of 5 years or more post qualification experience

- statutory requirement of 7 years or more post qualification experience

- statutory requirements of 5 or 7 or more years post qualification experience and subject to additional selection criteria. For salaried posts, additional criteria often include that the Lord Chancellor expects that individuals must normally have served as a judicial office holder for at least 2 years or have completed 30 sitting days in a fee-paid capacity

- no statutory eligibility criteria (for non-legal posts)

For the first two categories (which are typically applied to fee-paid legal posts), data are supplied by the SRA, the BSB and CILEX as outlined below. Note that, based on advice from these professional bodies, the definitions used since 2019-20 differ from those used previously though the difference has been assessed as small and unlikely to materially impact on the resulting conclusions[footnote 12].

For the third category (which is typically applied to salaried legal posts), the data represent the information available on the composition of the pool of judicial office holders in England and Wales, taken from published statistics for the previous year.

The report also includes figures for average years of PQE among candidates who have applied for judicial selection in the latest three year period. These are a guide to actual levels of experience of applicants, and are therefore different from the eligible pool which is based on all those eligible for a role (many of whom will not apply).

Eligible pool figures are not calculated for non-legal posts, because there are no common statutory eligibility criteria, and are only calculated for characteristics where suitable data is available – currently sex, ethnicity and legal role.

The eligible pool figures presented in the statistics should be considered as best estimates of the pool, which while a good guide to the diversity of those theoretically eligible are unlikely to be precisely accurate. For example, there are some legal professionals who are not captured in the pool as defined here but who may be eligible to apply for certain judicial appointments.

Additionally, in order to estimate an overall eligible pool for legal exercises, individual exercises are weighted according to their share of recommendations rather than aggregating the eligible pools (as these vary greatly from around 1,000 to over 100,000, this would give disproportionate weight to exercises with large pools but few recommendations).

High average PQE among applicants does not necessarily lead to a better chance of success. Further investigation into the relationship between experience and success in the judicial appointments process is currently being conducted by the Judicial Diversity Forum. It will look at experience in terms of exposure to types of legal work, seniority level and PQE. This remains an area of interest for the JDF.

Professional Background When considering applicants’ professional background, applicants for judicial roles are analysed based on their full career history (i.e. whether they were ever a solicitor, or ever a barrister) as well as their current legal role at time of application. The “ever” legal role is based on applicants’ self-reporting and does not take account of the relative time spent in each profession. Numbers of Chartered Legal Executives are not high enough to be considered in the “ever” legal role analysis. Please see Section 4.5 for more details on “ever” legal role.

Legal professions

Coverage: As noted above, figures for barristers and solicitors are based on the practising population i.e. those holding practising certificates. Those who are not practising, and for solicitors, those who are not eligible for judicial appointment, are not included. Figures for Chartered Legal Executives are based on all those who have fellowship of CILEX, as only fellows of CILEX are eligible to apply for judicial appointments. This also currently includes those who are non-practising, but who remain eligible.

Post-qualification Experience: For barristers, years of post-qualification experience (PQE) are based on years after the completion of pupillage (and therefore becoming fully qualified) – this will include any years where a practising certificate was not held. This differs from the number of years from admission (or Call) to the Bar (‘years of Call’) which is an alternative measure and includes any time between Call and completion of pupillage.

For solicitors, years of PQE are based on the number of annual practising certificates held[footnote 13] which is different to the number of years on roll as a practising certificate may not be held every year. Compared to the number of years since qualification, this approach better takes account of those who have had a career break. Note however that having a practising certificate does not necessarily mean that a solicitor was working as such during that year.

For Chartered Legal Executives, years of PQE relate to years since achieving fellowship[footnote 14].

Seniority: Definitions of seniority for each profession are included in this publication, though it is important to note that these are not equivalent (so that comparisons between professions should be avoided). In particular, for barristers, KC status is awarded for excellence in advocacy and so is not equivalent to partner status shown for solicitors. While KC is used as an indicator of seniority in this publication, not all senior barristers will choose to apply for KC rank:

- Solicitors: solicitor at the lower level and partner at the higher level[footnote 15]. The senior level of partner includes owners and managers of law firms. There is no equivalent way of identifying seniority for in-house solicitors who are all included in the lower level of solicitor[footnote 16]

- Barristers: junior barristers (lower level) and Kings’s Counsel (KC)[footnote 17] at the higher level.

- Chartered Legal Executives: On the question of partner, this question is not directly asked of the CILEX membership. The categories which are offered for self-selection include partner or equivalent, other alternatives which would include partner or equivalent also include other roles, the data for which cannot be separated. Chartered Legal Executives that are only fellows represent the lower level, while those who are also partners represent the higher level of seniority (if an individual is a fellow and partner, they are counted as partner). There is no equivalent way of identifying seniority for in-house Chartered Legal Executives so they are all included in the lower seniority level.

3.3 Diversity characteristics

These statistics cover diversity characteristics where data is available and considered to be sufficiently robust - deemed to be when the minimum required declaration rate is achieved.

The minimum required declaration rate[footnote 18] for this publication is 60%. Where this declaration rate has not been met, the data has not been included. As declaration rates improve, we hope to include more information in future releases.

Sex

This report uses the term sex when describing the differences between men and women in the data (the relevant question for CILEX refers to gender rather than sex). For the avoidance of doubt, this is based on self-declared data provided about sex (males and females) not data relating to gender identity[footnote 19].

For the judiciary and JAC data, unknowns represent those who preferred not to declare their information.

Ethnicity

For the judiciary, judicial appointments and the legal professions, ethnicity is recorded by self-declaration on administrative systems on a non-mandatory basis, with the individual selecting the most appropriate category based on their own self-perception from the a list of options or stating they choose not to declare. These options are aligned as much as possible with the latest ONS Census definitions.

As with previous reports, we have considered the newest Cabinet Office guidance[footnote 20] and the findings of the Sewell Report[footnote 21]. Recommendations included moving away from the term Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) and disaggregating ethnicity as much as possible. As a result, in this publication:

- where possible, ethnicity is presented in data tables in aggregated form, using white, Asian or Asian British, black or black British, mixed, and other ethnic background, and “unknown”, where individuals have either not responded or have stated their preference not to give a declaration.

- in the report, or in data tables where the above approach could pose serious disclosure risks[footnote 22], those from the black, Asian, mixed and other categories are grouped together (referred to as the ‘ethnic minority’ group) and compared to those in the white group. This is different from the government’s recommendation of including white minority groups in the ethnic minority group so that all ethnic minorities are considered together. We will continue to include white minorities in the white group here to retain consistency and comparability with previous publications, but will keep this approach under review for future publication. We also acknowledge that grouping ethnicity in this way does not capture the different outcomes of people within these groups. However, it is necessary to not risk disclosure of personal information, and from a statistical perspective, to consider groups with sufficient numbers to make meaningful comparisons. The comparisons presented maintain consistency with previous iterations of this bulletin and is consistent with the approach used in other statistical publications.

The data tables accompanying this report provide breakdowns of ethnicity in the high-level categories referred to above for the legal professions and Judicial Office (JO). This breakdown is also provided for the Judicial Appointments Commission (JAC). However, due to the risk of disclosure from small numbers in a single year, only data for the aggregated ‘ethnic minority’ group is provided for the latest year. Statistics on the more granular ethnic groups are available as an aggregation of numbers of candidates over the latest 3 years of data, and so are only available in the “JAC_3_years” tables.

Age

For the judiciary and judicial appointments data, age is calculated from date of birth. Data is grouped for publication, based on the distribution of ages among the judiciary. These are under 40, 40-49, 50-59, 60-69, and 70 and over. The latter group has been included following the introduction of the new Mandatory Retirement Age of 75 as from 10 March 2022.[footnote 23].

For the combined publication, the same age groupings have been used for judicial appointments and legal professions, which differ from the groupings used in previous JAC publications. Age is calculated as at the date of close of applications[footnote 24].

Professional background / legal role

For the judiciary, this refers to the legal profession which individuals had predominantly been employed within prior to taking up judicial office. This information is collected by self-declaration on a non-mandatory basis, reflecting the perception of the individuals themselves. Options include, but are not limited to, ‘solicitor’, ‘barrister’, ‘Chartered Legal Executive’ (Fellows of the Chartered Institute of Legal Executives) and ‘other’. Some ambiguity may also exist where individuals have had multiple prior roles (for example an individual that had been both a solicitor and a barrister would need to choose just one of these to enter, which is likely to be the most recent profession at the time of taking up judicial office and figures will not capture the prior professional experience not recorded in such cases).

For applicants for judicial appointments, legal role is presented using information from a question on the application form regarding the professional background of applicants. Options include, but are not limited to, ‘solicitor’, ‘barrister’, ‘salaried judicial office-holder’, ‘CILEX’ (Fellows of the Chartered Institute of Legal Executives) and ‘other’. Changes to the questions asked on professional background have enabled more comprehensive data on the full professional background of applicants, in addition to their current legal role. From 2019 onwards, legal role has been reported using two methodologies: applicants who have a current legal role of solicitor and applicants who have declared ever holding the role of solicitor (which is compared to ever barrister i.e. those currently holding a legal role of barrister and those who have declared holding the role of barrister in the past).

Further information on the development of the ‘ever’ legal role methodology is included in the 2018-19 JAC statistics publication.

Disability

Disability data is currently published only for the JAC. It is recorded as a binary characteristic of whether individuals have self-declared that they have, or do not have, a disability. Disability comes in many forms, and the impacts, needs and adjustments that may be required vary from individual to individual. In order to make statistical comparisons, reasonable numbers are required, and while simple binary categories do not reflect these differences, increasing granularity would substantially reduce analytical capability.

For the judiciary, disability information is collected on a non-mandatory basis by self-declaration, representing the perception of the individuals themselves, but it is not currently possible to differentiate between those with no disability, and those who have chosen not to provide the information. Disability status may change over time; an individual’s diversity information is as provided at point of entry unless they contact the relevant HR staff to update their disability information should their status change. Judicial office holders can now enter disability data as part of self service, but it is not yet to the level required for publication.

Sexual orientation

This is currently available only in JAC data, and recorded by asking applicants to declare whether they identify as a gay male, a gay female/lesbian, bisexual, or heterosexual. This is collated for statistical purposes into a binary category, grouping gay, lesbian and bisexual individuals together, in comparison to heterosexual individuals. We acknowledge that this simplifies the diversity of sexual orientation, and does not capture all identities. Consistent with the Equality Act 2010, this protected characteristic is distinct from and independent of gender identity. Accordingly, the familiar acronym LGBT is not appropriate for use when looking solely at sexual orientation as a protected characteristic. Sexual orientation figures are currently only presented aggregated across all selection exercises conducted within the financial year, due to the small numbers observed in individual exercises.

Religion or belief

This is also only available in JAC data. It is recorded with a range of options, including Buddhist, Christian, Hindu, Jewish, Muslim, Sikh, other religions and no religion. Religion is presented grouped across all the exercises reporting in a year. While declaration of religion continues to be lower than for other characteristics, it is above the threshold at which we would have concerns about representativeness and bias. It would not be statistically meaningful to present the full granularity of declared religions by selection exercise, given the very low numbers observed for many religions.

Social mobility

This is not considered a protected characteristic under the Equality Act 2010, however it is an important aspect of diversity with a specific duty to consider social mobility in the public sector. Currently only JAC collects this data, having added questions on social mobility in October 2015, in line with the Social Mobility and Child Poverty Commission’s recommendation that government and employers should collect data on the social background of new and existing post-holders. This information has been published for exercises from 2017-18 onwards. Information captures the type of school attended from ages 11-18, identifying whether applicants attended an independent/fee-paying school, went to a state school, or attended a school abroad. It also captures whether applicants attended university, whether either one or both parents went to university, neither went to university, or that the candidate did not attend university.

3.4 Summary of declaration rates for all diversity characteristics

The following table compares the current availability of data[footnote 25], and where appropriate, declaration rates, for the different diversity characteristics. Where declaration rates are below 60%, data is not included within the publication. It is anticipated that where these rates are currently above 40%, they may improve to be suitable for inclusion over a 3-4 year timescale.

| Judiciary (Judicial HR data) | Judicial Appointments (JAC data) | Barristers (BSB data) | Solicitors (SRA data) | Chartered Legal Executives (CILEX data) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | See published data tables | See published data tables | See published data tables | See published data tables | See published data tables |

| Age | See published data tables | See published data tables | See published data tables | See published data tables | See published data tables |

| Ethnicity | Around 90% | Close to 100% | Around 90% | Around 80% overall, but under 50% for those with under 6 years PQE[footnote 26] | 97% |

| Professional background | Over 90% | 99% for current legal role (in legal exercises) | Not applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Disability | Not currently possible to identify accurately | Close to 100% | 62% | Around 80% [footnote 27] | 95% |

| Social mobility | Not recorded before 2019 | Close to 100% | 50-57% | Recently started recording | 81% |

| Religion or belief | Not recorded before 2019 | 92% | 56% | Under 40% | 91% |

| Sexual Orientation | Not recorded before 2019 | 92% | 58% | Under 40% | 91% |

| Post-qualification experience | Not applicable | Not currently published | Virtually 100% | Virtually 100% | Virtually 100% |

| Seniority | Not applicable | Not applicable | Virtually 100% | Virtually 100% | Virtually 100% |

| Practice area | Not applicable | Not applicable | Not included in this publication but available[footnote 28] | Not considered reliable | Not included in this publication but available[footnote 29] |

3.5 Confidentiality and disclosure

Judiciary: There is no suppression of small numbers within the published data tables. Currently figures are presented for each characteristic, so that the risk of using some information to deduce other characteristics for an individual is considered minimal. Where figures are presented on the intersection of characteristics in Table 3.3, similar appointments have been grouped together in order to further minimise the risk of disclosing sensitive information. All individuals have the right to withhold their diversity information (via choosing ‘prefer not to say’).

At the senior levels, lists and biographies of judges are published on the Judicial Office website. While there are low numbers for some appointments in these statistics, which may allow senior judges to be identified, it is considered that this does not disclose information which is not already in the public domain.

Publication of these figures is in accordance with the privacy notice maintained by the judicial HR team.

Magistrates recruitment data: {To be determined}

Judicial appointments data: Exercises with fewer than 10 recommendations are aggregated so that applicants cannot be personally identified and are presented in the following groups:

- Small court exercises (High Court and below)

- Small tribunal exercises

- Small exercises (the two groups above combined)

- Senior judicial (above High Court) exercises

In larger exercises, there may be cases where certain breakdowns presented result in low numbers within that breakdown. It is considered that this is an acceptable risk to confidentiality; the applicants’ anonymity is still protected because the process of application itself is confidential and applicants can come from a wide range of areas within the legal profession and judiciary. Therefore, even if there is only one candidate with a particular characteristic it should not be possible to identify that person. By contrast, smaller exercises for more specialised posts sometimes accept applicants from a very narrow pool of eligibility, increasing the risk of a particular person being identified in the statistical results. This risk is mitigated by aggregating such exercises together.

In the accompanying statistical tables, percentages have been suppressed and replaced with an asterisk if they are based off a category containing fewer than 10 individuals. This is because percentages can be volatile for small groupings and are not considered reliable from a statistical perspective. Relative Rate Indexes (RRIs) have also been suppressed if either of their constituent recommendation rates contain numbers too small to be displayed.

Legal professions: Data included in this publication are aggregated and given the large numbers involved, the risk of identifying individuals from the published figures is considered to be very low. However, for the newly-introduced 70 and over age-group, figures for the lowest PQE bands (0-4 and 5-6) have been grouped in the data for solicitors due to very low numbers.

4. Methodology and calculations

4.1 Representation percentages and declaration rates

Representation percentages - the representation of particular groups within a diversity characteristic - are calculated excluding unknowns. This is the standard approach used across the Ministry of Justice, and more widely across government. They are presented for applicants and those recommended for appointment in judicial selection exercises, as well as judicial office holders and the legal professions.

Representation percentages allow comparison of the distribution of each diversity characteristic at different stages of the selection process, and for the current judiciary. This is particularly useful for judicial applications, giving a clear picture of the diversity of the pool of applicants, and how closely they represent the general population, and, where applicable, the eligible pool. It is also useful at the recommendation stage to illustrate the end result from a diversity perspective. However, representation among those recommended for appointment is the combined result of the representation among applicants and rates of success for each group in being recommended for appointment. Consideration of whether there is any significant difference in outcomes for a particular selection exercise can be viewed independently of initial level of applications by considering recommendation rates (below).

It is appropriate to consider this alongside the declaration rate – the proportion of the total number of individuals who gave a declaration for the characteristic. Only where the declaration rate is sufficiently high to mean that coverage of the characteristic is good will the representation percentage be presented. Where declaration rates fail to meet the minimum threshold of 60%, representation percentages are withheld as the level of uncertainty is too great for representation percentages to be meaningful. The higher the declaration rate, the better the coverage and the greater the certainty over the representation figures.

4.2 Recommendation rates (judicial appointments)

The recommendation rate is a simple measure of the proportion of applicants in one group that were recommended for appointment, derived from the total number of applicants as the denominator, and the number of those applicants that were recommended for appointment as the numerator. Direct comparison can be made between the recommendation rate for one group (such as women) compared to the recommendation rate for the other group (such as men) to determine, of those from each group that applied, whether there were equal outcomes for both groups (similar rates of recommendation for both groups), or whether there was a difference in outcomes, with one group being recommended at a statistically significant different rate to the other group.

While the recommendation rates for each group allow direct comparison within a characteristic, these rates are entirely dependent on both the number of applicants to an exercise and the number of vacancies being recruited for in the exercise. As such, while comparisons can be made within a single exercise, it would not necessarily be meaningful or valid to make simple comparisons across different exercises or across time, where the scale of applicants relative to the number of vacancies would differ. When considering recommendation rates, it is important to consider these alongside the representation percentages of applicants in the eligible pool, where available.

To make more meaningful comparisons across time or across different exercises requires a measure of difference in outcomes on a standard scale. This standardised measure of difference in outcomes is described as the Relative Rate Index (RRI).

4.3 Relative Rate Index (judicial appointments)

The Relative Rate Index, or RRI, gives a standardised measure of difference between groups, independent of variation in the overall rates of recommendation. However, when considering the RRI, it is important to consider, where available, the representation percentages of applicants relative to the eligible pool (or, if not available, the representation in the relevant working age population).

The use of RRIs for judicial appointments statistics was reviewed by MoJ statisticians, with recommendations published in a report which contains further background to the approach[footnote 30].

The RRI is the rate of recommendation for one group divided by the rate for another group within a diversity characteristic, thus creating a single standardised ratio measure of relative difference in outcomes between those 2 groups. This is most suited to binary comparisons (for example: women and men, ethnic minority and white, disabled and non-disabled).

RRIs are also used to compare outcomes for solicitors relative to barristers, the particular comparison of interest for professional background, while noting this does not account for outcomes of those from other professional backgrounds. As interpretation of the RRI is to see this value as the comparison of outcomes of a group of interest (the group as the numerator in the calculation) to a baseline group (the group as the denominator), it is logical that the baseline should be the historically largest group by count of individuals.

An RRI value of 1 indicates no difference (that is, the recommendation rate of one group is precisely the same as the rate of the other group, so when dividing one by the other, a value of 1 is obtained). An RRI greater than 1 means the group of interest (women, ethnic minority individuals, solicitors, people with disabilities) had a greater likelihood of being recommended for appointment than the baseline group, while an RRI of less than 1 indicates that the group of interest was less likely than the baseline to be recommended for appointment. For example, a sex RRI of 1.5 would be interpreted as women being 1.5 times as likely (50% more likely) to be recommended than men. Similarly, a sex RRI of 0.5 would be interpreted as women being half as likely (50% less likely) to be recommended than men.

RRIs can be calculated for different stages of the application process, and following the recommendations of the review, the data tables include the following:

- Eligible pool to recommendation

- Application to recommendation

- Eligible pool to application

- Application to shortlisting

- Shortlisting to recommendation

This enables relative differences between groups to be compared for each stage of the process. However, within the publication, depending on the characteristic being discussed, only application to recommendation RRIs or eligible pool to recommendation RRIs are given – these present the best overall indication of relative success for different groups, which takes into account their prevalence among those eligible, although in some instances it may be more appropriate to look at one rather than the other. For example, where the proportion of the group in question (such as ethnic minority) within the eligible pool is smaller than that of the actual applicant pool, it may be more appropriate to look at RRI from application to recommendation rather than from eligible pool. All the exercise stage RRIs (Eligible Pool to Application, Application to Shortlisting, Shortlisting to Recommendation, Application to Recommendation and Eligible Pool to Recommendation) are presented in the accompanying tables.

Statistical significance: Where RRIs are calculated, their statistical significance is assessed – this provides a measure of the likelihood of the RRI being that large (or small) due to chance i.e. where the number of candidates is low, RRIs can fluctuate which may not indicate an underlying disparity. Statistical significance is estimated by calculating confidence intervals using a ‘bootstrapping’ approach which enables better estimation for smaller exercises[footnote 31]. A 95% confidence interval is calculated – broadly, the range of values which we can be 95% confident the true RRI lies between – and where this interval contains 1, an RRI is not statistically significant.

Practical significance: To further aid interpretation the “4/5th rule of thumb for adverse impact” is used[footnote 32],[footnote 33]. RRI values that fall within a range of 0.8 to 1.25 (the zone of tolerance) are considered not likely to indicate a difference in outcomes resulting in a disparity having practical significance. This does not imply that an RRI falling outside of this range is indicative of the presence of a meaningful disparity. The nature of selection exercises inevitably results in low numbers. In some cases, the numbers are too low to calculate the RRI. However, even where an RRI can be calculated, numbers within some selection exercises are too low for making meaningful attributions of a potential difference. As such, caution should be taken when considering whether an apparent difference in rates, as measured by an RRI falling outside the range of 0.8 to 1.25, could represent a meaningful difference.

Of the two, statistical significance is the more important measure. If an RRI is not statistically significant, we cannot be confident that the estimated RRI reflects a real difference between the groups being compared. If an estimated RRI falls outside of the “zone of tolerance” - and might therefore be referred to as “practically significant” - but is not statistically significant, its result should be interpreted with caution as it may be down to chance. If an estimated RRI is within the “zone of tolerance” - and not “practically significant” - but is statistically significant, we can be confident that there is a real difference between the two groups, even though it may be small. It is then up to the discretion of policy makers to decide whether the small difference is worth investigating further and acting upon.

Some figures in the bulletin show the RRI values with their confidence intervals in a graphical format. Statistically significant results – where the confidence interval does not overlap the parity line - are coloured light blue. The tolerance zone is shaded grey; results falling within this zone are considered to represent a disparity which is not large enough to be considered practically important (and tend not to be statistically significant).

4.4 Intersectionality (judicial appointments)

In the previous two reports, RRIs were also used for the analysis of intersecting groups of characteristics (e.g. sex and ethnicity, sex and professional background, etc) in judicial appointments. However, following an internal review a more robust approach to the methodology has been implemented for this year’s report to better separate out the main effects from the intersectional effects, as described below.

The role of intersectionality in judicial appointments was analysed using a statistical technique called a logistic regression. The model was built using sex, ethnicity, and professional background as predictors of recommendation. Three main effects (female, ethnic minority, solicitor) and four interaction terms (ethnic minority by female; ethnic minority by solicitors; female by solicitors; and female by ethnic minority by solicitors) were estimated using white male barristers as the comparator group. This approach allows readers to separate out the pure, or main, effect of ethnicity, sex and professional background from any effects of these factors combined. A 95% confidence level was used to determine the statistical significance of the results.

Logistic regression model results were converted into relative risk values, which follow a scale similar to how RRIs are presented elsewhere in the bulletin. Relative risk captures the estimated impact of each characteristic on the likelihood of recommendation for a given candidate. An estimated risk greater than one suggests a higher likelihood of recommendation than white male barristers, and an estimated risk below one suggests a lower likelihood.

4.5 Professional background - calculation of “ever” legal role (judicial appointments)

The 2018-19 JAC publication was the first in which “ever” legal role was reported in addition to current legal role. The “ever” legal role measure compares “ever” solicitors (those who have declared ever holding a role as a solicitor) to “ever” barristers (those who have declared ever holding a role as a barrister). Chartered Legal Executives data is not yet included because the totals of this group are too small within the judicial appointments data to make meaningful comparisons to other groups.

In the accompanying statistical tables, the values for “Solicitor in the past” and “Barrister in the past” are a count of those who have declared previously holding a role as a solicitor or barrister. “Adjusted solicitor numbers” and “Adjusted barrister numbers” consider those who have been both a solicitor and barrister in the past. If someone has held both roles they have been assigned a value of 0.5 for both solicitor and barrister to avoid double counting. Numbers are rounded up to the nearest whole number and therefore totals may not match.

A worked example using the methodology has been presented below:

- Solicitor (only) in the past = 340

- Barrister (only) in the past = 216

- Both a solicitor and barrister in the past = 41

- Adjusted solicitor numbers = 340 + (0.5 x 41) = 360.5 (rounded to 361)

- Adjusted barrister numbers = 216 + (0.5 x 41) = 236.5 (rounded to 237)

There are around 10% more applicants identified as solicitors using the wider definition of ever legal role. The ‘ever legal’ role typically results in increased RRIs when comparing solicitors relative to barristers, though broad patterns are similar; however, a smaller difference in success rates between solicitors and barristers was generally observed for senior roles using the ‘ever legal’ role. This is because an applicant’s current legal role is likely to be a salaried Judicial Office holder and so expanding the definition of legal role is likely to highlight previous experience as a solicitor and/or barrister. Further details were included in the background notes for the 2018-19 statistics.

It is important to note that the “ever legal” approach does not account for the relative periods of time an individual has spent in each profession (as this information is not captured). This may mean that some of those classified as ever solicitors may have spent the majority of their career as a barrister and should be kept in mind when interpreting the results.

5. Users and uses of these statistics

5.1 Known users

Among the individuals, groups and types of organisations with an interest in these statistics are:

| Internal customers: Ministry of Justice, Judicial Office and JAC | This group includes ministers and officials within MoJ, Judicial Office, Her Majesty’s Court and Tribunal Service and within the JAC in policy, operational or analytical roles. We have an ongoing dialogue with these users and receive most feedback from within this group. |

| Legal professional bodies (e.g. the Bar Council, The Law Society, Chartered Institute of Legal Executives) | These statistics include data supplied by professional bodies and in developing the new combined report we have engaged closely with them to incorporate feedback. More generally, we receive feedback from the Judicial Diversity Forum which brings together representatives from the legal professions. |

| Other groups with an interest in judicial diversity issues (e.g. JUSTICE, the Black Solicitors Network) | Published figures have been analysed in detail for JUSTICE’s report on diversity in the judiciary and we are happy to provide support and advice where this is useful. |

| Existing judges and candidates for judicial appointment | We receive occasional ad-hoc requests via the judicial statistics mailbox, or through officials. |

| Parliament | Statistics are used to answer parliamentary questions from both MPs and Lords. |

| Journalists/media | These statistics are sometimes reported on or cited, most often by specialist press. |

| Academics, researchers and members of the public | We receive occasional ad-hoc requests via the judicial statistics mailbox or via Freedom of Information requests. |

| Other public bodies | Judicial diversity statistics are included in the ‘ethnicity facts and figures’ publication produced by the Cabinet Office Race Disparity Unit. |

5.2 What the statistics are used for

These statistics have a variety of uses, some of which include:

- To inform the development and monitoring of policy and actions relating to judicial diversity. This includes the work of the Judicial Diversity Forum, which brings together officials from MoJ, JAC and the judiciary with the legal professions and draws on the patterns shown in these statistics to identify and monitor actions to improve judicial diversity

- Use as evidence for equality impact assessments relating to judicial issues (including the recent consultation on raising the retirement age for judges), and to inform other aspects of judicial policy including annual evidence to the Senior Salaries Review Body

- Use by charities, campaigning groups and others to hold government to account, and they inform reviews of judicial diversity including those as published by JUSTICE and the Lammy Review.

- Feeding in to cross-cutting publications to provide comparisons between diversity in the judiciary and elsewhere, including MoJ’s ‘Race and the Criminal Justice System’ statistics, and the Ethnicity Facts and Figures

- Responding to occasional Freedom of Information (FoI) or other ad-hoc requests[footnote 34] received directly or via the judicial statistics mailbox (judicial.statistics@justice.gov.uk)

5.3 User engagement

We always welcome feedback on the content, format and timing of these statistics.

In developing the new combined publication, a working group was formed with representatives from policy and diversity teams in MoJ, Judicial Office, the JAC and the legal professional bodies. Following its publication, the group still meet on a regular basis to discuss and agree potential changes and future developments on the content and presentation of the report. In addition, the way in which the outcomes of judicial selection exercises are presented in the statistics (specifically the use of the relative rate index) was independently reviewed by MoJ statisticians in consultation with a range of users, with the results of the review published in February 2020.

5.4 User feedback and changes made

The table below sets out selected details of the history of the combined judicial diversity statistics and the publications it superseded. These changes are made based on user feedback, or following consultation with users.

As noted above, we will seek and respond to feedback on the new combined report following publication, and log this as part of this guide.

| 2010 | Judicial appointments: the first Official Statistics bulletin was published in February 2010. Prior to that, the diversity results of selection exercises were published online. Publishing these data as Official Statistics aimed to improve users’ confidence in the information. |

| 2015 | Judiciary data: age breakdown included for the first time. |

| 2018 | Judicial appointments: inclusion of information related to social mobility for the first time as part of the 2017-18 statistics. |

| 2019 | Judiciary data: statistics on entrants and leavers added as experimental statistics, in response to answering requests for evidence from the Senior Salaries Review Body, FoI requests and other general enquiries. The new tables increased value for users, presenting flows in and out of the judiciary to allow an assessment of how diversity of the judiciary is changing. Following review of the approach and in the absence of user concerns, these have been incorporated into the statistics from 2019-20 onwards. Judicial appointments: inclusion of reporting on ‘ever’ legal role for the first time, providing comparison of solicitor and barrister applicants on a basis which takes account of their full professional background. |

| 2020 | Development and publication of the first combined judicial diversity statistics. Judicial appointments: review of the use of RRIs published, making a number of recommendations for improvements (annex A lists these together with the resulting actions). |

| 2021 | Included for the first time were data on the intersection of diversity characteristics: gender with ethnicity, gender with professional background, ethnicity with professional background and the intersection of gender, ethnicity and professional background. Also, jor the judicial appointment selection exercises, data for the most recent three years were combined for analysis, to provide more granularity with minimal risk of disclosure on Gender, Ethnicity and Profession intersections. |

| 2022 | Figures on the economically active population (EAP) based on data from the 2020 Annual Population Survey were included in the commentary of the report alongside where the 2011 Census data was used, to provide additional context when looking at the proportions of the different ethnic minority groups. |

5.5 Latest additions to the publication

As of this year’s report, information has been included from the new magistrates recruitment programme, and also about judges sitting in retirement. In addition, two new tables have been added - one with a time series of legal professions data and another with intersectional information about existing magistrates.

A more robust methodology was used to analyse the intersectionality of characteistics in the judicial appointments data for the 2023 report.

5.6 Future developments

We continuously look to gain wider feedback on the bulletin and try to develop the statistics as required in response to this. Indeed, a number of potential areas have been identified where further work could be carried out, and we will seek to investigate and address these for potential inclusion in future publication.

| Area | Planned Developments |

|---|---|

| Coverage of characteristics / improved declaration rates | As noted above, there is currently more limited coverage of diversity characteristics for the judiciary and the legal professions than for the judicial appointments process. We hope that reporting rates will improve to allow more complete coverage to be captured in this publication in future years, though this is unlikely to happen immediately. In addition, there have been some minor changes to the collection and recording of diversity information for applications for judicial selection, which may affect the presentation of these statistics in future (for example, the new form captures gender in a non-binary way). |

| Time series / historic data | Currently the publication presents limited data on trends over time, and does not make it easy for users to obtain data for different years; we will explore ways to bring the most recent and previously published data together better. |

For example, there is ongoing work to improve declaration rates for the characteristic groups. This includes:

- For the judiciary, the Judicial Office rolled out a new, improved data declaration system, including a campaign to encourage declaration by judicial office holders. Their declaration rates for disability, social mobility, religion or belief and sexual orientation should improve annually as a result, with data being publication-ready in the next few years.

- For the legal professions, all the professional and/or regulatory bodies have either just installed or have plans to update or establish new IT systems to enable diversity characteristic declaration from their members:

- The BSB introduced a new data declaration system in 2018 and subsequently saw a significant increase in their declaration rates. Assuming a continued annual increase, it is hoped that the declaration rate for characteristics including disability, sexual orientation, social mobility and religion will be suitable for publication in approximately 3 to 4 years. Additionally, it is anticipated that information collected during training (where response rates are higher) will be used to populate the records for newly-qualifying barristers.

- The SRA has updated the diversity questions on its systems and is actively engaging with solicitors to increase declaration rates.

- CILEX and CILEx Regulation run campaigns to encourage members to improve their declaration rates following the introduction of a new data declaration system. Their declaration rates have improved and should improve annually as a result, with data being publication-ready in the next few years.

While it is likely that these new systems will prompt significant improvements in declaration, it is difficult to identify a reliable estimate of how quickly declaration rates will increase at this point.

6. Revisions

6.1 Revisions policy

The procedure for handling planned or unplanned revisions to these statistics will be in line with the published revisions policy for MoJ statistics, available from www.gov.uk/government/statistics/ministry-of-justice-statistics-policy-and-procedures.

In particular, where errors are found in the published figures, an assessment will be made as to whether these are materially significant. If so, a revision will be announced and published at the earliest opportunity. If not (i.e. if any errors are considered to be minor) then the figures will be revised with the next publication.

The following outlines how the specific data within the publication is treated.

6.2 Judiciary

Data for the judiciary are an annual snapshot from a live administrative system, taken roughly two months after the period to which they relate. As the database is live, it is likely that were data for the same period extracted at a later date, the precise figures could be different, although we would expect any differences to be minimal. However, except where clear errors are identified, figures published for earlier years are not revised in any way.

6.3 Judicial appointments

The published statistics, though quality assured, are liable to revision. This could either be because of a late amendment to the database or because of recommendations made by the JAC after the initial report to the Appropriate Authority (see section on recommendations).

The standard process for revising the published statistics to account for these late amendments is to publish them in the next annual edition if the revision accounts for an additional 10 or more recommendations being made. However, revisions that consist of less than 10 recommendations will not be published. This is because a comparison of the original presentation of the exercise and the revised presentation of the exercise could identify those applicants recommended since the publication of the bulletin. In accordance with the disclosure policy for these data, releasing information on exercises of less than 10 recommendations may constitute a threat to applicants’ privacy (see section on confidentiality and disclosure).

6.4 Legal professions

The figures published are as provided by the professional bodies. It is not anticipated that these will be revised except when future year’s publications are produced; at this time, we will seek advice from the data suppliers as to whether any revisions are required to previously published figures.

6.5 Revisions made

For the 2023 combined publication, as mentioned previously, legal professions were asked to provide historical data going back to 2014. As these were provided based on the latest as at April 2023, there may have been a small number of revisions made compared to previously published figures.

In the previous report for 2022, the answer to the parental university attendance question for judicial applications was incorrectly coded, and so the analysis in that report for this question was incorrect, and has been corrected accordingly.

7. Related statistics

7.1 Other jurisdictions

As noted, these figures relate to the judiciary of England and Wales. Diversity statistics for other jurisdictions are available:

Northern Ireland: www.nijac.gov.uk/publication/equality-monitoring-report-2021

7.2 Other diversity statistics

Diversity statistics are published by the Ministry of Justice for other elements of the justice system

- Ethnicity and the criminal justice system statistics provide a compendium of available statistics www.gov.uk/government/statistics/ethnicity-and-the-criminal-justice-system-statistics-2020

- Women and the criminal justice system statistics provide a compendium of available statistics www.gov.uk/government/statistics/women-and-the-criminal-justice-system-2021

The Cabinet Office Race Disparity Unit presents a range of data on ethnicity, including the judiciary and other professions, in their Ethnicity Facts and Figures

7.3 Legal professions publications and data

Each of the legal professions considered within the combined publications publishes information on diversity within the profession. This provides further detail than the relatively high level summary captured in these statistics

-

Solicitors: Diversity data is published by the SRA in their firm diversity data tool, based on data collected through a bespoke survey of law firms every two years. The current firm diversity data is from 2021. This is aggregated data from law firms, representing approximately 70 percent of the practising population and therefore figures do not match precisely those used within this publication.

-

Barristers: The Bar Standards Board produces an annual report on Diversity at the Bar, the most recent of which, based on data for 2022, was published in January 2023.

-

Chartered Legal Executives: CILEX publishes some high-level diversity statistics on its website.

8. Contacts for further information