Violence reduction unit year ending March 2021 evaluation report

Published 1 April 2022

Executive summary

In 2019, the Home Office announced that 18 police force areas (PFAs) would receive funding to establish (or build upon existing) Violence Reduction Units (VRUs), as part of the Serious Violence Fund. VRUs take a preventative, whole-system approach to violence reduction, which comprises:

- multi-agency working

- data sharing and analysis

- engaging young people and communities

- commissioning (and developing) evidence-based interventions

The Serious Violence Fund also covers Surge activity, which is enforcement focused. Combined, VRU and Surge funding represents a total investment of £174m across the financial years 2019 to 2020 and 2020 to 2021 to tackle serious violence (SV). The 18 areas were selected, and funding amounts allocated, based on levels of SV between the financial year ending 2016 to that ending 2018.

The Home Office commissioned Ecorys, Ipsos MORI, the University of Hull and the University of Exeter to conduct a process and impact evaluation of VRUs in their second year of operation (April 2020 to March 2021). The broad aims of the evaluation were to:

- undertake a process evaluation, and linked theory-based impact evaluation, to understand how VRUs are implementing a whole-system approach to violence reduction in their second year of (Home Office) funding and how this is contributing to VRUs meeting their aims

- estimate the impact of VRUs against outcomes specified by the Home Office, and others also related to violence reduction.

The process evaluation (and linked theory-based impact evaluation) included a comprehensive document review to develop a theory of change (ToC) for each VRU and, based on these, the programme-level analytical framework and research tools. In-depth qualitative research was subsequently undertaken, with all 18 VRUs capturing the views and experiences of 290 stakeholders/beneficiaries in total.

The impact evaluation applied multiple quasi-experimental designs, which estimate what would have likely happened in the absence of funding, on a range of (serious) violence outcome measures to estimate as robustly as possible the initial impacts of the Serious Violence Fund.

Key findings

There are early indications of VRUs impacting on violence reduction. While there was no (statistically significant) impact detected on the most serious SV outcomes (hospital admissions and homicides), there were impacts on police recorded violence. Between April 2019 (when SV funding was deployed) and September 2020, it is estimated that 41,377 violence without injury offences had been prevented in funded areas, relative to non-funded areas. Alongside a reduction of 7,636 violence with injury offences, this represents potential costs avoided of £385m. Relative to the amount of SV funding over the same period, this represents a return of £3.16 for every £1 invested [footnote 1]. Recognising VRUs are a longer-term preventative approach, these results are encouraging. Past research into public health approaches to preventing violence (e.g. the Scottish VRU and the Cardiff model) indicates a greater impact will accumulate over the medium to longer term for VRUs. Furthermore, VRU and Surge activity appear to be complementing each other with a greater combined impact (and positive working relationships reported by stakeholders).

In terms of different elements of the whole-system approach, VRUs have continued to make progress since year 1. This was particularly evident for multi-agency working and data sharing, where previous work provided a strong foundation to build on. While some progress was evident for engaging young people and communities, and commissioning/delivering interventions, these were generally more susceptible to challenges resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic. The short-term nature of funding was also recognised as a limiting factor to embed a longer-term whole-system approach. Key findings against each element of the whole-system approach included:

-

multi-agency working:

- VRUs have made good progress in developing partners’ understanding, skills and practices of preventative approaches to SV

- at the strategic level, VRUs continued to strengthen partnerships, streamline approaches, and identify and facilitate areas for collaboration; owing to the large geographical coverage of the VRUs, some reported slower progress engaging (smaller) community and voluntary sector organisations

- multi-agency working was more developed at the strategic level than at the operational level; the latter was recognised as something that takes longer to achieve; VRUs, where this was more developed at the operational level (e.g. those building on VRUs that were in place prior to SV funding), reported that ensuring strategic alignment was essential for the vision of the VRU to take effect at the operational level

-

data sharing and analysis:

- the Strategic Needs Assessments (SNAs) – which identify local trends in violence, crime and their underlying causes – developed in year 1 provided an opportunity for VRUs to reflect on and refine their data focus; this has led to a greater appreciation for data as a tool to prevent violence

- police data continued to be the most accessible and used source by VRUs; data are most commonly accessed and analysed at an aggregate level (i.e. overall numbers in sub-areas and/or for specific cohorts); some VRUs are accessing individual-level data; progress has been made in accessing health, education and other sources but some challenges, particularly the requirement of multiple/complex data sharing agreements, persist

- having the expertise to analyse data from multiple sources in a meaningful and insightful way was identified as a key enabler; some VRUs were working with external experts, with experience of the data and the required data sharing agreements, to provide analysis in an accessible format (e.g. data dashboards)

- VRUs had/were developing overarching outcomes frameworks, which they intended to track progress against; however, recognising the scale and range of interventions commisioned, there was some challenges in collecting consistent and accurate data at this level

-

young people and community engagement:

- engagement activities were designed and delivered to serve a variety of purposes; some VRUs focused on understanding experiences of crime and SV, some aimed to understand communities’ needs and concerns, while others planned to embed young people and communities in the design of the interventions they commissioned

- despite most VRUs having engagement plans in place in year 2, only limited progress had been made to engage communities and young people in activities that would inform their strategy and objectives; a significant challenge in year 2 was the impact of COVID-19 restrictions; moving into year 3, young person and community engagement is a priority for VRUs

- VRUs can learn from and/or link in to VRU partners’ existing engagement strategies

-

commissioning and delivering evidence-based interventions:

- there were signs of VRUs making progress in terms of strategically commissioning interventions; this was most evident in the commissioning of interventions which aligned to the SNAs developed by VRUs; there was some evidence of the comissioned interventions being evidenced-based, but it was too early to provide a comprehensive assessment owing to missing data, funding cycles ongoing and the impact of COVID-19

- with an estimated 262,000 individuals supported in year 2, there is early indicative evidence to suggest that VRUs had effectively reached children, young people and adults through the delivery of interventions; recognising interventions were ongoing, limited progress in monitoring/evaluation, and delivery being affected by COVID-19 restrictions (as was the research with young people), the effectiveness of the individual interventions could not be assessed at this stage; however, young people who could take part in the research reported positive perceptions and benefits of their interventions

Recommendations

In terms of the future development of VRUs, the evaluation findings support the following recommendations:

For the Home Office to:

- support VRUs to improve the quality of intervention monitoring data which informs, and underpins, evidence-based commissioning

- urge other central government departments, including Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) and Department of Education (DfE), to improve data access at VRU level and ensure partners take responsibility for their role and involvement in the VRU

And for VRUs to:

- ensure clear, evidence-based rationale for commissioned interventions, supported by the Youth Endowment Fund (YEF) toolkit

- increase focus on effective engagement of voluntary and community sector at a strategic level

- consider the potential role of external experts to navigate common data-sharing challenges and increase data analysis and insight capacity

- share any good practice toolkits or resources on implementing whole-system approach with all VRUs through learning networks

Acknowledgements

The report authors wish to thank all individuals who contributed to this evaluation. In particular, we acknowledge the support and participation of all 18 VRU teams and their local stakeholders/beneficiaries. We also thank Home Office analysts and policy colleagues, for their support throughout the evaluation, and the wider evaluation team at Ecorys and Ipsos MORI for all their contributions to the fieldwork and analysis.

Special thanks also to the University of Exeter for providing additional funding through the Strategic Priorities Fund to support the evaluation.

1. Introduction

This report presents findings from the process and impact evaluation of Violence Reduction Units (VRUs) in the financial year 2020 to 2021, the second year of their operation. VRUs have been funded in 18 Police Force Areas (PFAs) since the financial year 2019 to 2020, primarily to provide leadership and strategic co-ordination of all relevant agencies to support a ‘whole-system’ approach to tackling SV and its root causes. This VRU evaluation was commissioned by the Home Office in July 2020 and conducted by Ecorys in partnership with Ipsos MORI, Prof. Iain Brennan (of the University of Hull) and Prof. Mark Kelson (of the University of Exeter).

This chapter begins with an overview of the policy background and context for the establishment of VRUs, followed by a description of the evaluation aims, objectives and methodology. The chapter then provides the overall theory of change (ToC) for VRUs that underpinned/informed the evaluation design and implementation. The chapter concludes by setting out the scope and structure of the remainder of the report.

1.1 Policy background

In the summer of 2019, the Home Office announced that 18 PFAs would receive funding to establish (or build upon existing) VRUs as part of the Serious Violence Fund announced by the Treasury earlier that year. The areas were selected by their levels of SV experienced between the financial year ending 2016 and that ending 2018. In early 2020, funding was confirmed for a second year (April 2020 to March 2021).

The core aim of a VRU is to provide leadership and strategic co-ordination of all relevant agencies, to support a public health/whole-system approach to tackle SV and its root causes. Alongside the VRU core function, each PFA is required to fund specific interventions working with young people (aged under 25).

Key aspects of the whole-system approach, as summarised in Home Office (2020), include:

- working with and for communities (and young people)

- unconstrained by organisation or professional boundaries (i.e. multi-agency)

- focusing on a defined population

- a response comprising short- and long-term solutions

Additional hallmarks of the whole-system approach are the need for data and intelligence to understand the pattern of SV experienced by the population and evidence of effective interventions to respond to the problem. These reflect both the internal monitoring and reporting required of VRUs and the evaluation work undertaken. The key outputs that inform each VRU’s response are the:

- Strategic Needs Assessments (SNA), which explore trends in SV and associated risk factors to understand the at-risk cohort (i.e. target population) and local issues

- Response Strategies, which set out how the VRUs are seeking to prevent/reduce violence, in the context of the SNA

The Home Office specified three outcomes against which the VRUs would be measured:

- reduction in hospital admissions for assaults with a knife or sharp object and especially among victims aged under 25.

- reduction in knife-enabled SV and especially among victims aged under 25.

- reduction in all non-domestic homicides and especially among victims aged under 25 involving knives.

The evaluation covers the above and additional outcomes (both quantitative and qualitative).

The Serious Violence Fund also covers Surge activity. The same 18 PFAs received Surge funding, which, like VRUs, aims to reduce violence (measured against the same outcomes) but focuses on enforcement (e.g. increased policing of hotspot areas, Stop and Search), rather than the more preventative focus of VRUs.

Table 1.1 details the funding allocations by PFA. Key points to note about funding are:

- both VRU and Surge funding were allocated based on the volume of hospital admissions for assault with a sharp object between the financial year ending 2016 and that ending 2018

- VRU funding (£70m across two years) followed a tiered system, whereas Surge funding (more) directly reflected each force’s percentage share of overall hospital admissions

- each VRU received the same amount of money in the financial year 2020 to 2021 as they did in 2019 to 2020

- Surge funding accounted for more than VRU funding in both 2019 to 2020 (£63m) and 2020 to 2021 (£42m)

- some VRUs were subject to local match funding (e.g. additional funding from the Office of the Police and Crime Commissioner and/or in-kind resource from partner agencies)

Table 1.1: Serious Violence (SV) funding allocations (overall total in the financial years 2019 to 2020 and 2020 to 2021)

| Police Force area | Surge | VRU | Total SV funding |

|---|---|---|---|

| London | £34,487,455 | £14,000,000 | £48,487,455 |

| West Midlands | £12,601,485 | £6,740,000 | £19,341,485 |

| Greater Manchester | £7,943,375 | £6,740,000 | £14,683,375 |

| Merseyside | £6,955,100 | £6,740,000 | £13,695,100 |

| West Yorkshire | £6,655,315 | £6,740,000 | £13,395,315 |

| South Yorkshire | £4,269,410 | £3,200,000 | £7,469,410 |

| Northumbria | £3,844,185 | £3,200,000 | £7,044,185 |

| Thames Valley | £3,203,960 | £2,320,000 | £5,523,960 |

| Lancashire | £3,009,610 | £2,320,000 | £5,329,610 |

| Essex | £2,912,435 | £2,320,000 | £5,232,435 |

| Avon & Somerset | £2,843,520 | £2,320,000 | £5,163,520 |

| Kent | £2,742,215 | £2,320,000 | £5,062,215 |

| Nottinghamshire | £2,543,730 | £1,760,000 | £4,303,730 |

| Leicestershire | £2,316,990 | £1,760,000 | £4,076,990 |

| Bedfordshire | £2,288,730 | £1,760,000 | £4,048,730 |

| Sussex | £2,211,555 | £1,760,000 | £3,971,555 |

| Hampshire | £2,090,250 | £1,760,000 | £3,850,250 |

| South Wales | £1,980,680 | £1,760,000 | £3,740,680 |

| Total | £104,900,000 | £69,520,000 | £174,420,000 |

1.2 Evaluation aims and objectives

The Home Office commissioned Ecorys, Ipsos MORI, the University of Hull and the University of Exeter to conduct a process and impact evaluation of VRUs. The 2020 to 2021 evaluation (covering year 2 of VRU funding and activity) follows research undertaken in 2019 to 2020 (year 1), which explored the early implementation of VRUs (process evaluation) and assessed the feasibility of a future impact evaluation. The broad aims of the 2020 to 2021 evaluation are to:

- undertake a process evaluation to understand how VRUs are implementing a whole-system approach to violence reduction in their second year of (Home Office) funding

- using a combination of approaches, estimate the impact of VRUs against outcomes specified by the Home Office, and others related to violence reduction

Specifically, the process evaluation explores how the VRUs are working with partners to deliver, and the progress made towards, core elements of the whole-system approach:

- multi-agency working

- data sharing and analysis

- involving young people and communities

- commissioning and supporting interventions

Each of these elements (or activities), and how they are anticipated to contribute to meeting the VRU aims, are detailed in the VRU programme-level ToC (set out in Section 1.3 below).

The impact evaluation seeks to explore the overall impact of SV funding (which includes enforcement-focused Surge activity, as well as VRUs) on key outcomes and, as far as possible, isolate the impact of VRUs (independent from Surge). Linked to the exploration of core elements of the whole-system approach (detailed above), the impact evaluation also considers how, and under what circumstances, outcomes/impacts occur.

1.3 VRU Theory of Change

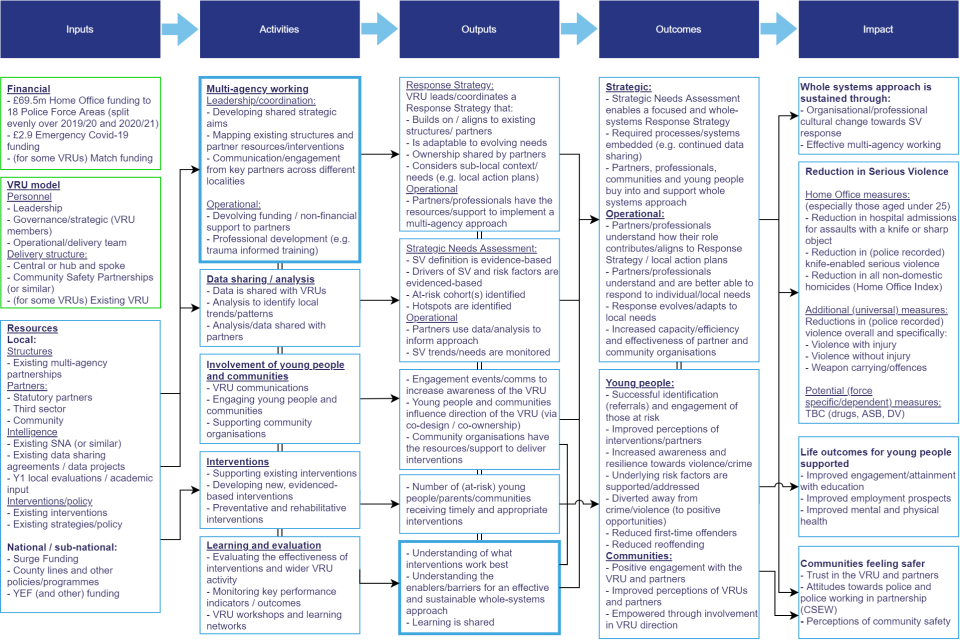

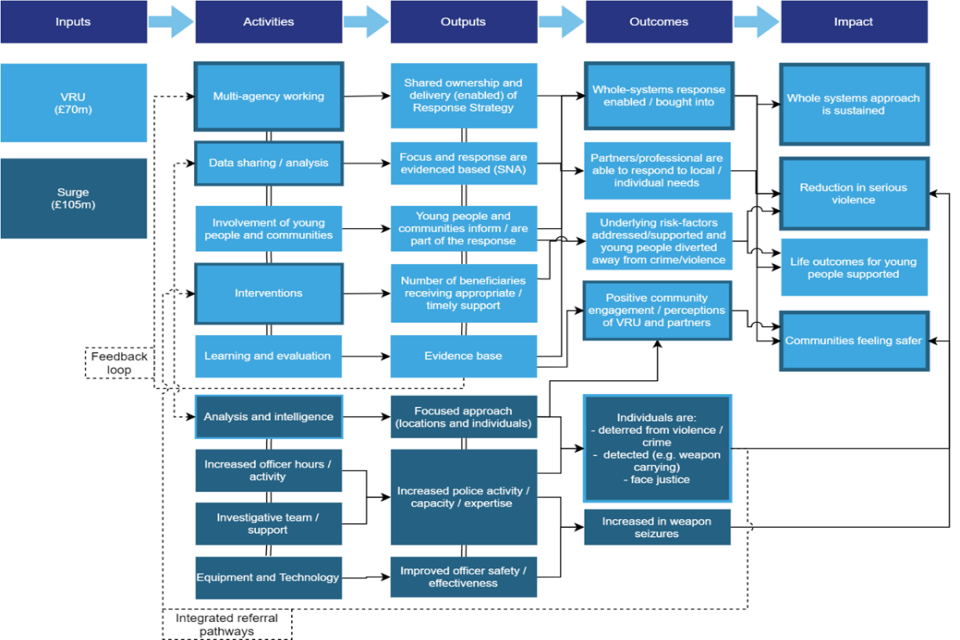

Figure 1.1 depicts a (whole) programme-level ToC for VRUs.

The ToC sets out the intended outcomes/impacts of VRUs and the presumed causal pathways (indicated by arrows) – through inputs, activities and outputs – to reach these.

The activities, which are the key elements of a whole-system approach, enable the intended outputs; these in turn are anticipated to result in outcomes. Outcomes at the strategic and operational, and young people and community levels, facilitate the ultimate impacts of a sustainable whole-system approach, reduced violence, improved life outcomes for young people, and communities feeling safe.

Figure 1.1: Programme-level Theory of Change (ToC) for VRUs

1.4 Evaluation methodology

The evaluation employs a mixed-methods design to gather and analyse evidence through several approaches to meet the evaluation aims. The different elements/stages of the evaluation methodology are:

- document review: key documents for each VRU (2020 to 2021 funding applications, SNAs and Response Strategies) were reviewed to identify potential changes to VRUs since the 2019 to 2020 evaluation and to develop/revise VRU-level ToCs and outcome frameworks; VRUs’ annual and quarterly monitoring reports were also reviewed for inclusion in later stages of the evaluation and analysis

- development of programme-level analytical frameworks: based on the document review and initial consultations with VRU leads, an evaluation framework (see Annex 2) and VRU programme-level ToC were developed to guide subsequent evaluation activity including research instruments, information and engagement materials and analysis tools

-

three phases of fieldwork to conduct qualitative research: a programme of in-depth consultations in all 18 VRU areas explored the implementation (process evaluation) and perceived effectiveness/impact (theory-based impact) of the core elements of the whole-system approach

- the three phases of fieldwork involved 290 interviews and discussion groups across the 18 VRUs between August 2020 and March 2021; comprising:

- 88 interviews with VRU leads, strategic VRU stakeholders and external partners

- 69 interviews with VRU operational and analyst staff

- 103 interviews with external operational and frontline staff (e.g. delivering VRU-funded interventions)

- 30 interviews with young people supported by VRU-funded interventions

- Impact evaluation using quasi-experimental designs, alongside a theory-based impact evaluation

An overview of the methods employed and key limitations, which are intended to aid interpretation of the findings presented, are provided in the sections that follow. Additional detail for the impact evaluation is provided in Annex 3.

Process and theory-based impact evaluation methodology

For the process and theory-based impact evaluation, semi-structured topic guides aligned to the evaluation framework and programme-level ToC were developed to inform data collection via in-depth consultations. The theory-based impact evaluation harnessed all evidence generated through the evaluation (quantitative and qualitative) to assess the contribution of different elements of the whole-system approach to violence reduction and wider VRU aims.

Impact evaluation methodology – outcomes of interest

The impact evaluation focused on select outcomes where there is a strong theoretical link to VRU (and wider SV funding) activity and data requirements were met [footnote 2]:

- NHS held data on hospital admissions resulting from intentional injury caused by a sharp object for:

- all ages

- those under 25 years old

- Home Office held data on homicides

-

Police recorded crime for the following offence groups:

- Violence with injury

- Violence without injury

- Possession of weapons offences

As far as available and reliable data allowed, these outcomes are aligned to the Home Office key outcomes for VRUs (see section 1.2). While police recorded crime is not a key outcome for the Home Office, it was included as an outcome of interest as it captures all types of violence (not just knife enabled), which is consistent with the preventative nature of VRUs, and is routinely used by the VRUs to monitor their own progress.

Impact evaluation methodology – analytical approach

Quasi-experimental designs (QEDs) were employed to meet the aims of the impact evaluation (see section 1.2). SV funding was awarded to the 18 PFAs experiencing the highest levels of violence, specifically, the number of hospital admissions resulting from intentional injury caused by a sharp object between the financial year ending 2016 and that ending 2018. As such, simple comparisons to areas that did not receive funding (which were experiencing less violence) are not appropriate. When funding is not allocated at random, QEDs are required to construct a suitable counterfactual (which is an estimation of what would have likely happened in the absence of treatment). QED approaches included:

-

Synthetic control methods (SCMs) to compare changes in outcomes following the introduction of SV funding between funded (‘treated’) and non-funded (‘comparator’) areas [footnote 3]; SCMs create a counterfactual by generating a weighted average of comparator areas based on their similarity on pre-VRU offending trends to treated areas; comparator areas, which depending on data availability, were PFAs and/or sub-areas within (e.g. community safety partnerships), that are more similar to VRU areas receive a heavier weighting than those that are less similar

-

Interrupted time series analysis (ITSA) to understand how trends within treated areas are affected following the introduction of SV funding; ITSA creates a counterfactual by forecasting outcome trends based on pre-SV outcomes, which can then be compared to the observed (post-SV funding) trends

The primary approach was SCMs recognising these include comparisons between funded and non-funded areas [footnote 4]. ITSA was a secondary/supporting approach. Both approaches included consideration of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the outcomes of interest [footnote 5]. Specifically, it was theorised that national lockdowns (and wider restrictions) affected people’s movement (e.g. they were spending more time at home) and, as such, this impacted on their exposure to / opportunity for violence. Exploratory analysis and models, using available data (e.g. data collected by Google on changes in movement), were conducted based on this theory.

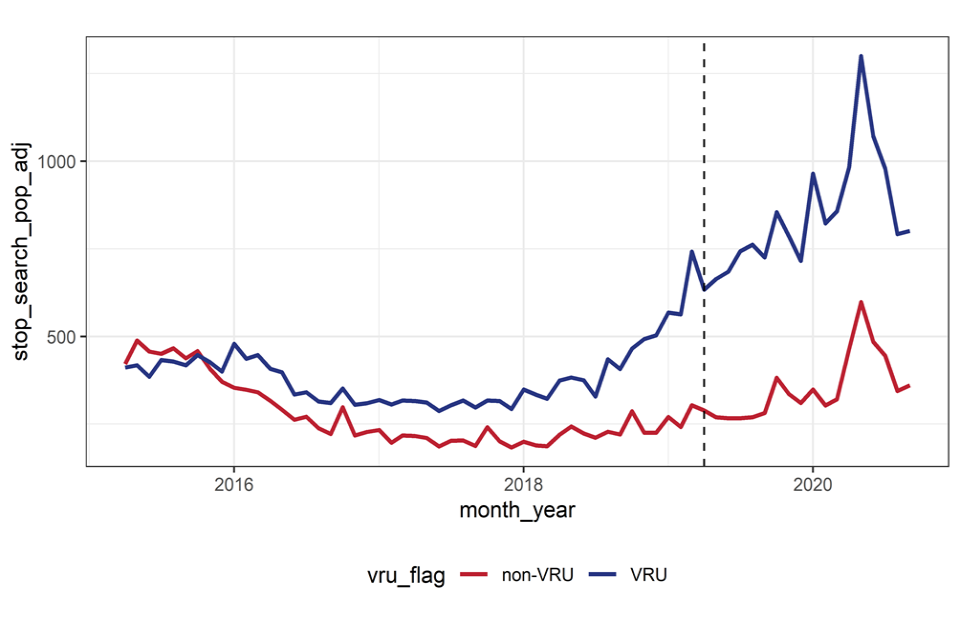

To, as far as possible, isolate the impact of VRUs independent from Surge activity, a combined VRU and Surge ToC was developed (see Annex 4). This led to the inclusion of Stop and Search rates (a proxy for increased police activity) in exploratory SCMs, where resulting impact estimates were compared to those from SCMs without Stop and Search rates included.

The term ‘impact’ is used when reporting the results. This is in recognition that SV funding was a substantial investment and, as such, there is an argument for attribution. However, it should be noted that there are other (unobservable) external factors and potential activity linked to violence prevention not fully captured in the methods described above.

Limitations to the evaluation findings

The evaluation was designed to ensure as robust and comprehensive approach as possible, combining multiple methods of data collection and analysis to provide a thorough investigation of how, why and in what context differing levels of success have been achieved within VRUs and at the programme-level.

However, there are some limitations to the approach which are important to bear in mind when considering the evaluation findings in this report. Key limitations to the data collection and analysis were:

- difficulties accessing some operational and frontline stakeholders due to impact of COVID-19: the second phase of evaluation fieldwork focused on expanding the range of stakeholder perspectives to conduct consultations with core VRU staff, alongside operational and frontline stakeholders; however, a second national lockdown at the start of this phase of fieldwork reduced the availability and ability of staff in these groups to participate in the research, particularly as some key staff were again redeployed to deal with their organisation/service’s responses to the pandemic; as a result, the proportion of operational and frontline staff is lower than anticipated; this presented some challenges in triangulating/comparing their views with those of staff in more strategic and senior leadership roles

- identification, selection and engagement of young people in the research: it was necessary to negotiate access to young people through VRU operational leads, as well as staff in frontline providers and delivery organisations; while research teams took all practical steps to avoid potential biases, there were limitations in their ability to target and sample research participants (e.g. only young people engaged by projects could be interviewed)

- timeframe required for observing outcomes and impacts: the ‘whole-system approach’ adopted by VRUs is a longer-term investment in addressing the root causes of SV and, as reflected in the programme-level VRU ToC, some of the intended outcomes of VRUs are only likely to be observable in the longer term, beyond the timescales of this evaluation

- variation in quality and coverage of monitoring and evaluation data on VRU-funded interventions: the available data on VRU-funded interventions, including that collected as part of the quarterly reporting process, varied significantly in the mode of collection and the extent to which the outcomes presented could be verified; as a result, it was challenging to consistently estimate the scale and nature of VRU-funded interventions with young people, or to assess outcomes and ‘distance travelled’ by young people given the lack of consistent and reliable baseline and follow-up data

1.5 About this report

The structure of this final report is:

- Chapter 2 sets out the approach to, and examines results from, the QED exploring the impact of VRUs on reducing SV

- Chapter 3 outlines VRUs’ definitions of SV and the at-risk cohort(s), and the processes and evidence used to agree these definitions, alongside a review of any changes to VRU models of working since year 1

- Chapter 4 examines the multi-agency element of the whole-system approach to violence reduction; this includes the different approaches taken to multi-agency working, the extent to which VRUs’ multi-agency activity is being implemented effectively, and an assessment of the extent to which multi-agency working is contributing to VRU aims (i.e. theory-based impact evaluation)

- Chapter 5 focuses on the data and intelligence-sharing element of the whole-system approach; this includes progress since year 1 on approaches to data sharing and analysis, the extent to which VRUs are effectively implementing these, and an assessment of the extent to which data and intelligence sharing is contributing to VRU aims

- Chapter 6 examines the changes in approaches taken to young person and community engagement since year 1, the effectiveness of these approaches, and the extent to which young person and community engagement has contributed to VRU aims

- Chapter 7 provides an outline of approaches to commissioning VRU-supported interventions, the types/numbers of interventions, and the extent to which interventions are being effectively commissioned and delivered; this is followed by an assessment of the extent to which VRU interventions are contributing to VRU aims

- Chapter 8 presents conclusions on the extent to which VRUs have contributed to violence reduction and wider aims, recommendations arising, and a brief review of any areas for further investigation

2. Impact of VRUs on violence

This chapter presents results from the impact evaluation. Section 1.4 explains the methodological approach (with Annex 3 providing additional detail).

2.1 Impact on hospital admissions

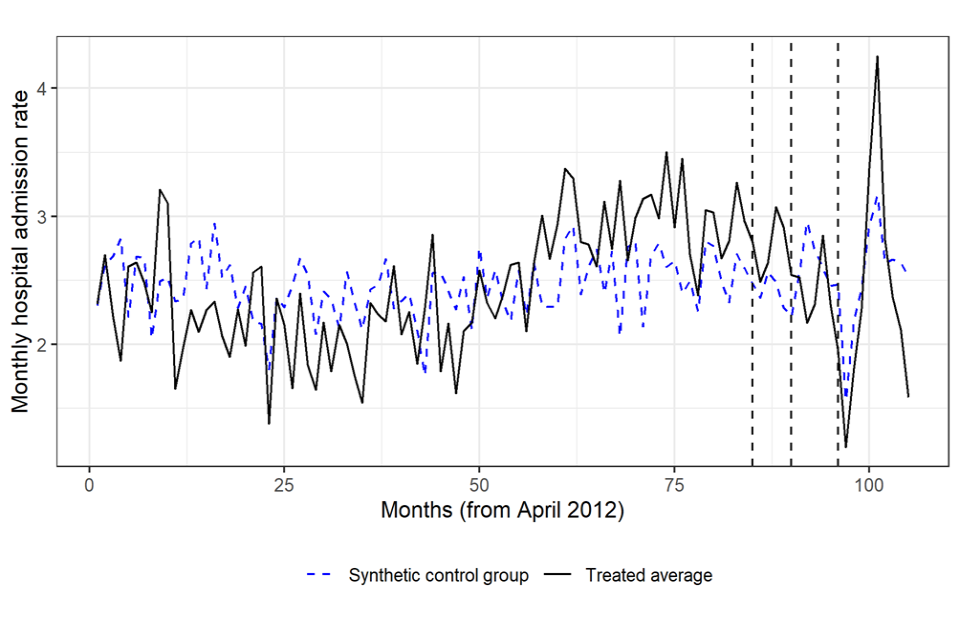

The impact evaluation did not detect a statistically significant association (impact) between SV funding (the intervention) and hospital admissions resulting from intentional injury caused by a sharp object (the outcome). In any statistics model, there is some uncertainty around the (impact) estimates due to variability in the data. Confidence intervals (CI) report this uncertainty by providing a range (upper and lower estimates), where there is a high degree of confidence (95% probability) that the true value (impact) falls within. If the CI range includes zero (i.e. where the true value could be positive or negative), the impact estimate is not considered statistically significant. CIs are reported throughout this chapter.

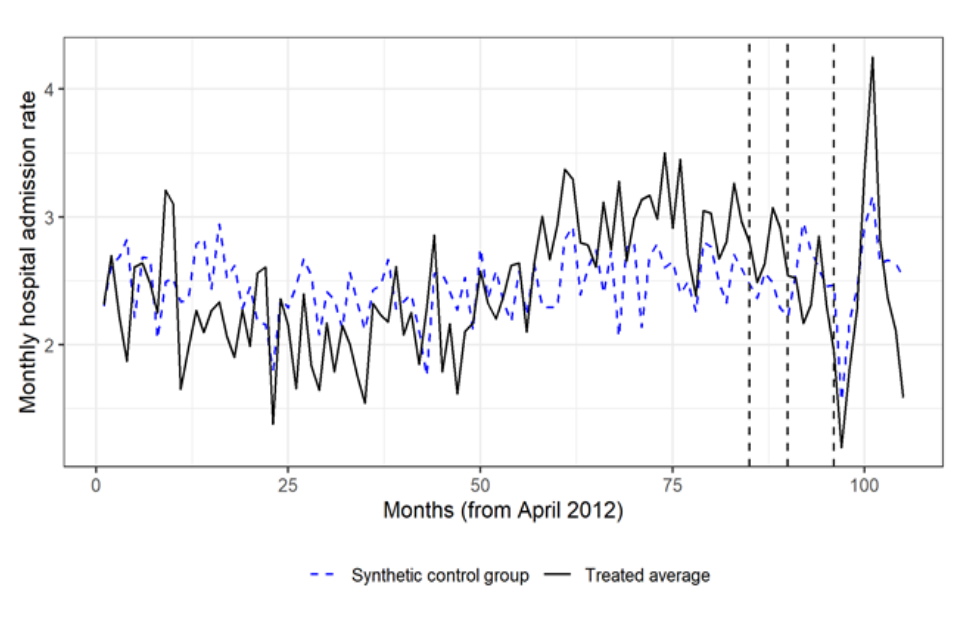

Relative to the synthetic control group (Figure 2.1), there was a small decrease of -0.03 per month (95% CI [-0.29, 0.25]) in hospital admission rates (per 1 million people) for under 25s in SV-funded PFAs, but this was not statistically significant. The wide range of CIs indicates high levels of variability in hospital admissions between areas and over time. Recognising the preventative/early intervention focus of VRUs, it can be argued that impacts on hospital admissions (a key measure of SV) may take longer to materialise (i.e. there is a lag effect). Evidence from the Scottish VRU (established in 2005) supports this argument, where homicides and SV were approximately halved, but this was over an eight-year period [footnote 6].

Figure 2.1 presents the results from the SCM for the rates of hospital admissions resulting from intentional injury caused by a sharp object for the under-25 age group (monthly PFA-level data). The SCM produced a good counterfactual with the synthetic control group (the dashed blue line) closely tracking the pre-intervention trend of the treatment group (solid black line). The treatment group in Figure 2.1 is the average hospital admission rate for SV-funded PFAs. The dashed vertical lines (left to right) represent SV funding allocated and Surge activity commencing (April 2019), VRUs set up (September 2019), and the start of COVID-19 restrictions (April 2020). For context, the increase in admission rates in June 2020 (month 101) was following the lifting of the national COVID-19 lockdown.

Figure 2.1: Average hospital admissions (under 25s) rates (per 1 million people) for treated PFAs and synthetic control group

SCMs adjusting for COVID-19 (using Google Movement data) and adjusting for Surge activity (using Stop and Search rates) also did not provide statistically significant results (and estimates were within the 95% CIs of the unadjusted SCM (Figure 2.1)).

Analysis conducted on the same hospital admissions outcome, but for all ages (not limited to under 25s), estimated an increase of 0.25 (95% CI [-0.27, 0.94]) in SV-funded PFAs relative to the synthetic control group constructed; however, this was not statistically significant.

2.2 Impact on homicides

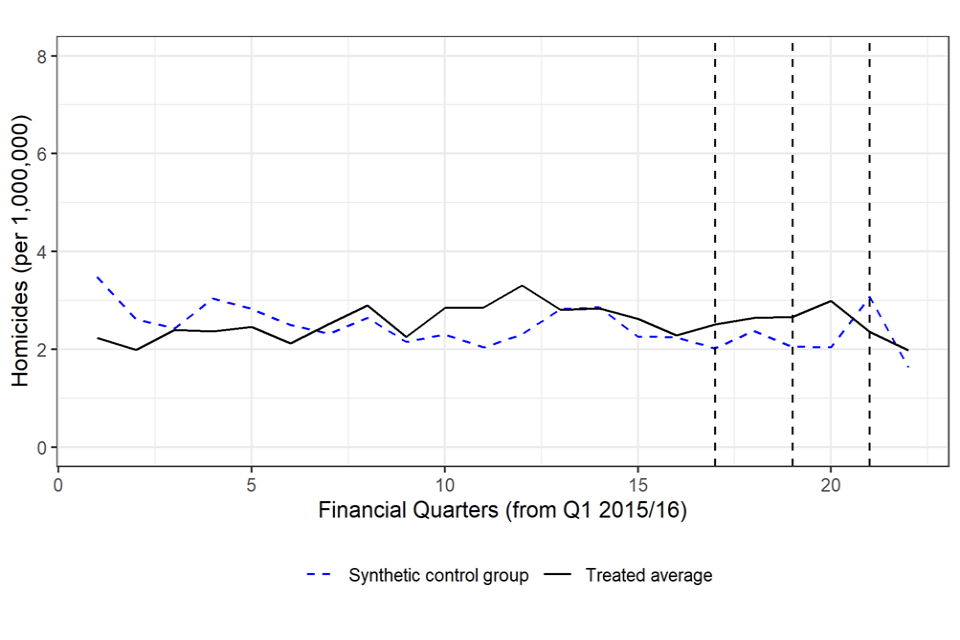

A statistically significant impact on homicides rates was not detected. The SCM estimated an increase of 0.32 (95% CI [-0.96, 1.61]). As per hospital admissions, the CIs reported are wide, and reductions in homicides are arguably a longer-term outcome for VRUs.

Figure 2.2 presents the results from the SCM for the homicides (quarterly PFA-level data), which can be interpreted similarly to Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.2: Average homicide rates for treated PFAs and synthetic control group

2.3 Impact on police recorded violence

There was a statistically significant decrease in police recorded violence in SV-funded areas. Impacts were most prevalent for violence without injury offences, which aligns to the more preventative/early intervention nature of VRUs.

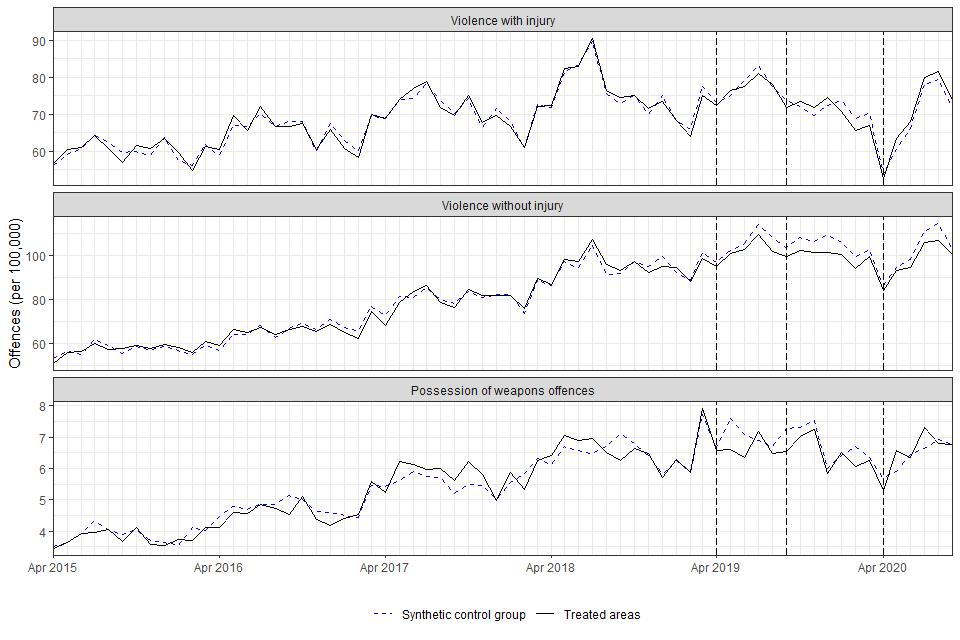

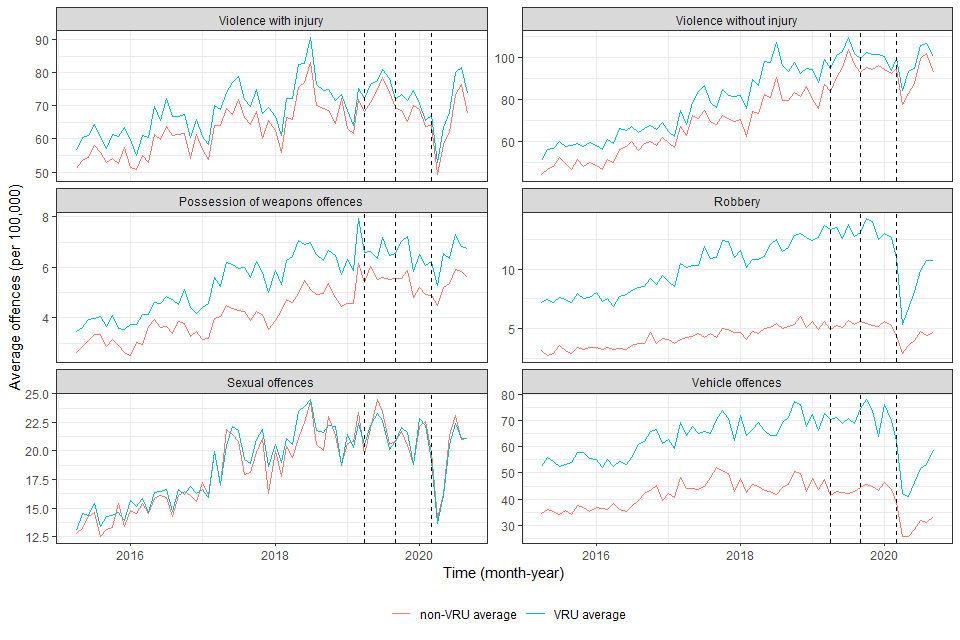

Figure 2.3 shows the results from the SCM for the violence offences and possession of weapons offence rates (per 100,000) (monthly Community Safety Partnership (CSP)-level data). The key findings are:

- relative to the synthetic control group, violence with injury rates in treated areas showed signs of reductions, but this was only statistically significant in some periods

- for violence without injury, there was a statistically significant reduction after allocation of SV funding; this impact was most prominent during live activity of both Surge and VRU

- there was a slight reduction in possession of weapons offences for treated areas, but this was not statistically significant

- the SCMs did not change substantially when adjusted for COVID-19 (using Google Movement data), indicating movement in SV-funded and comparator areas was similarly affected by COVID-19

Figure 2.3: Average police recorded offending rates for treated areas and synthetic control group)

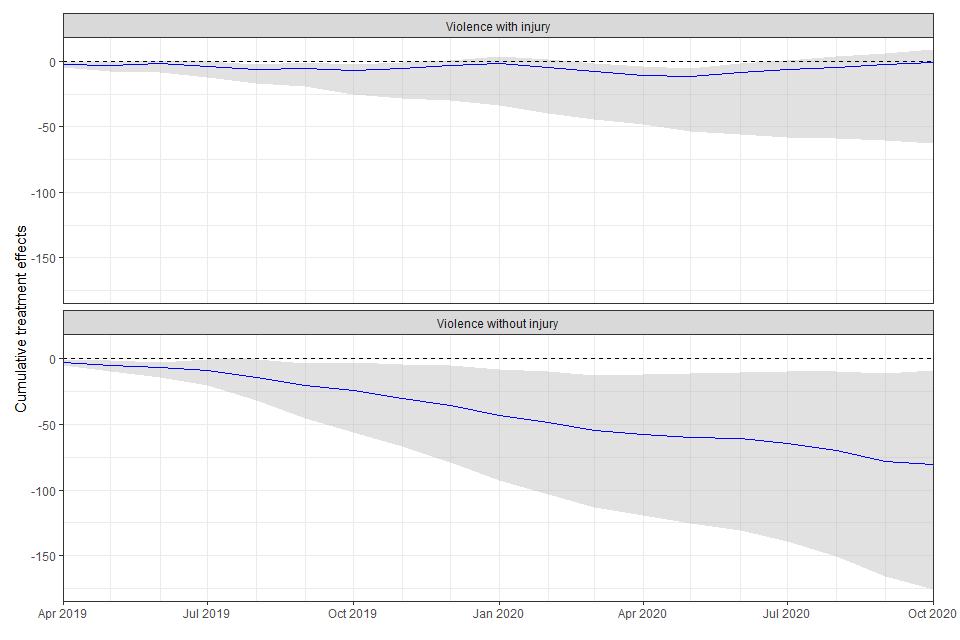

Figure 2.4 depicts the cumulative impact from the violence offences SCMs (above), which is the total difference in police recorded offences between the treated areas and synthetic control group [footnote 7]. In other words, for a given number of months after SV funding was allocated (April 2019), the figure shows how many offences in total had been avoided (the blue line). The grey shaded areas are 95% CIs. Key findings are:

- an impact was evident for violence with injury for brief periods (summer 2019 and early 2020) but not sustained throughout 2020

- there was a reduction of 80 violence without injury offences (per 100,000 population) by September 2020 (the latest period available) - based on the total population in funded PFAs (34,321,607), it is estimated that 27,585 violence without injury police recorded offences were avoided by September 2020

Figure 2.4: Cumulative impact on police recorded violence offences, from April 2019 (start of SV funding) to September 2020

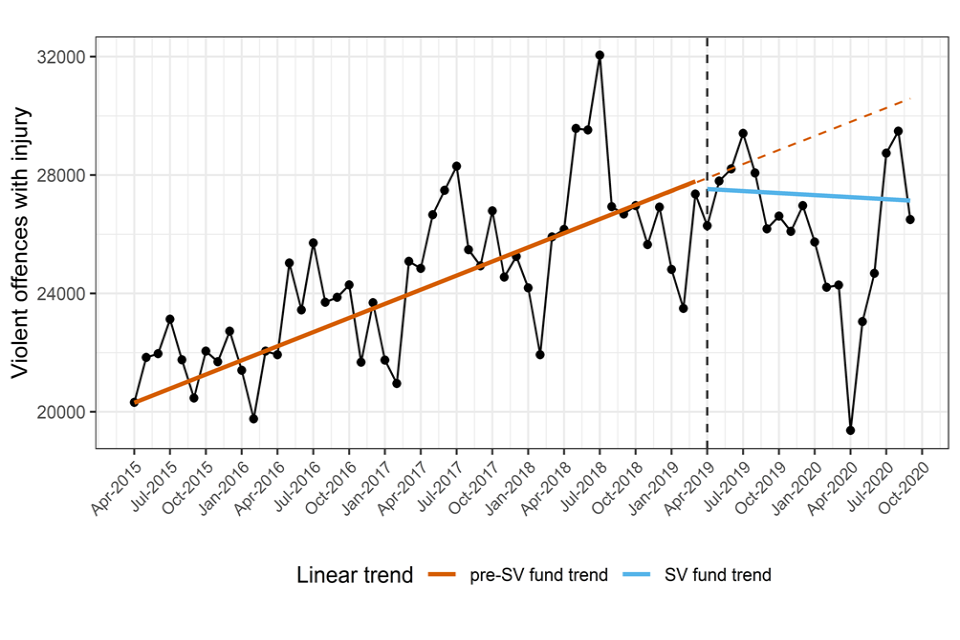

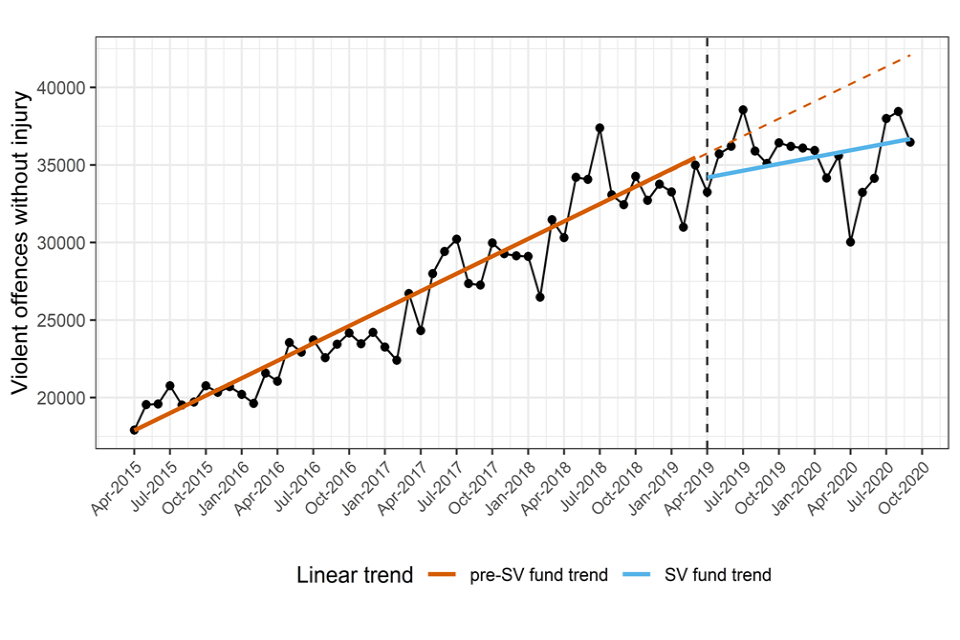

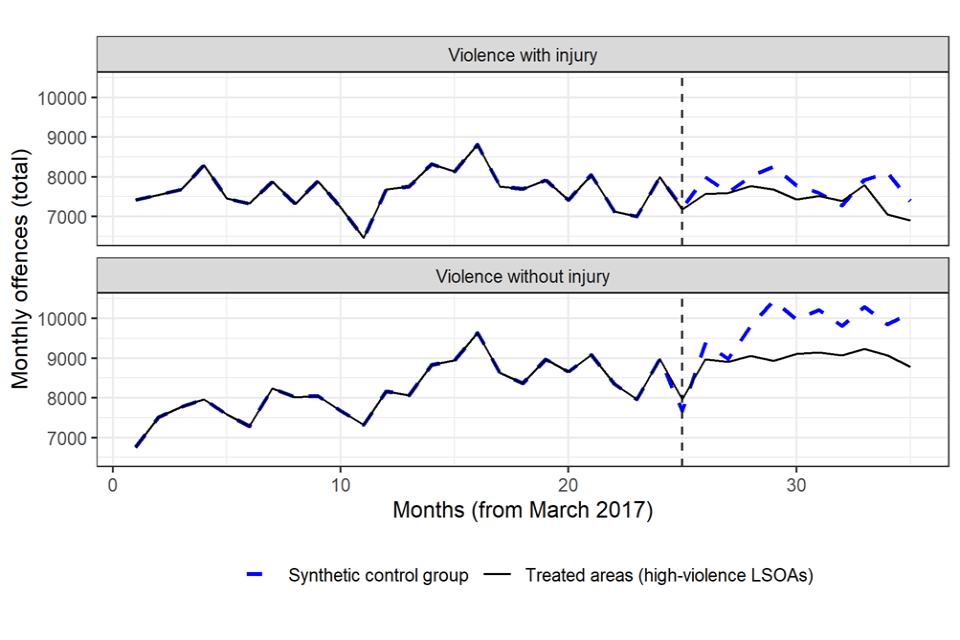

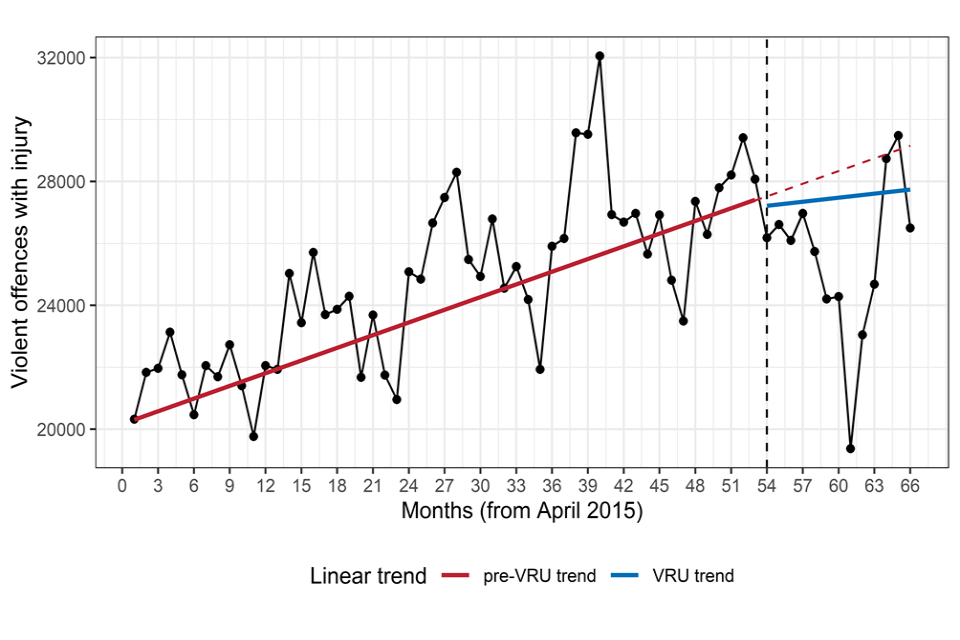

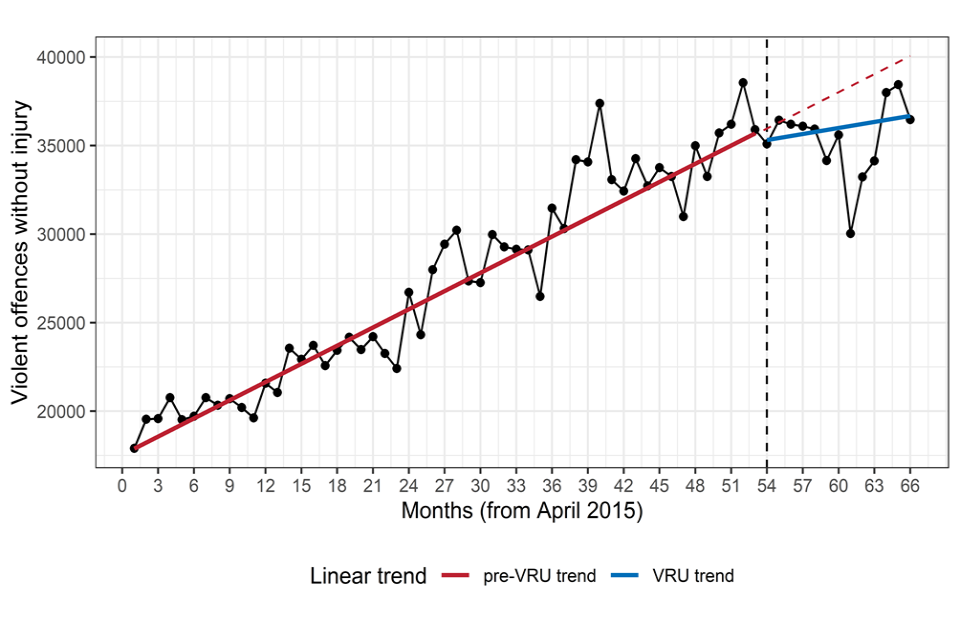

To further explore and validate the impacts from the SCM, interrupted time series (ITS) analysis was conducted. For violence with injury (Figure 2.5), there was an increasing trend in funded areas prior to introducing SV funding (left-hand side of the vertical dashed line). Following funding, the slope of the trend changed towards a slight decrease. This change in slope was statistically significant. For violence without injury offences (Figure 2.6), there was a levelling off in the trend following funding (not statistically significant). It is important to remember the ITS does not include a comparator group – the counterfactual is based on the pre-SV funding trend (dashed red line) – which explains the differences to the SCM results. The key finding is that both the ITS and SCM indicate reductions in violence offences, relative to their respective counterfactuals, following the introduction of SV funding.

Figure 2.5: ITS of police recorded violence with injury (all SV-funded areas)

Figure 2.6: ITS of police recorded violence without injury (all SV funded areas)

2.3.1 Analysis adjusting for Surge

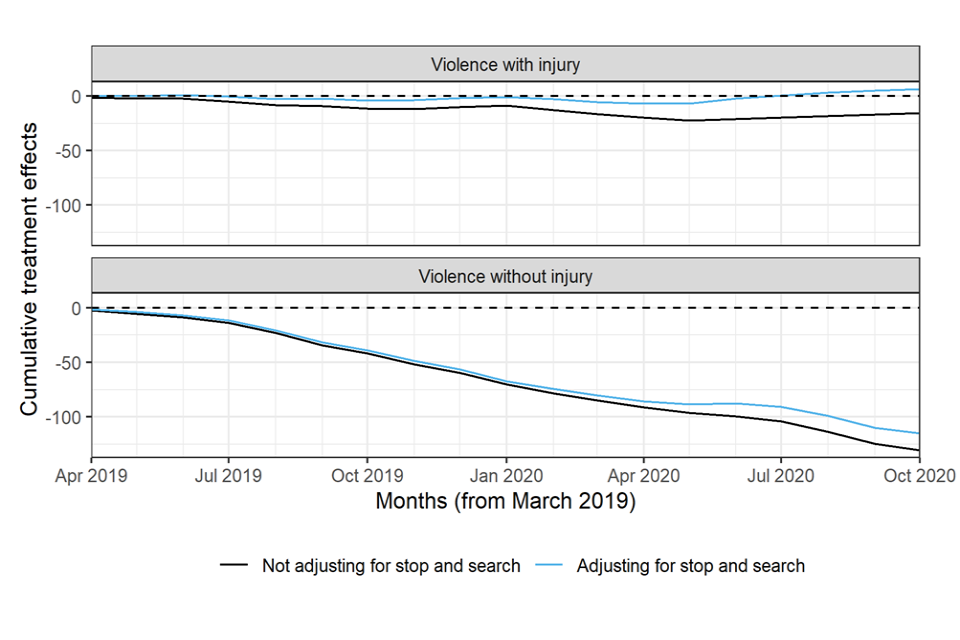

To isolate, as far as possible, the impact of VRUs from Surge activity, SCM models adjusting for Stop and Search rates (a proxy for police activity) were employed. This means impacts of SV funding, minus that associated with increased police activity (i.e. Surge), can be estimated. However, note that Stop and Search rates only capture an element of Surge activity (it works in multiple ways to reduce violence) and data for some PFAs were missing [footnote 8]. Recognising some PFAs were removed from the analysis, the (unadjusted) impact estimates presented below differ to those in the previous section.

Figure 2.7 shows the cumulative reductions in violence offences from SCMs with (black line) and without (light blue line) adjusting for Stop and Search rates. For violence with injury offences, the impact after adjusting for Stop and Search is much closer to zero (the dashed horizontal line) than without adjustment. This suggests that Surge activity is contributing to reductions in violence with injury. For violence without injury offences, there was also a reduction when adjusting for Stop and Search rates. This aligns with the preventative/early intervention nature of VRUs, where impacts on more serious forms of violence will likely take longer to materialise. The key finding at this stage is that VRU and Surge activity appear to be complementing each other, and adjusting for Stop and Search rates can help isolate the impact of each.

Figure 2.7: Cumulative impact on police recorded violence offences (with and without adjustment for Stop and Search rates), from April 2019 (start of SV funding) to September 2020

To further understand the impact of VRUs independent of Surge activity, ITS was conducted with the intervention period starting in September 2019 when VRUs became operational (rather than April 2019 in the previous section). The results showed a change in slope (levelling off) following intervention, but this was not as pronounced as the ITS covering the entire SV funding period. Again, this supports the dual approach of prevention (VRUs) and enforcement (Surge). The additional ITS outputs are provided in Annex 3.

2.3.2 Analysis focusing on violence hotspots

As highlighted in the programme-level ToC (see Figure 1.1), VRUs (and indeed Surge) are using data and intelligence to identify violence hotspots to target resources. To explore the potential impact of this approach, SCM was applied to Lower Layer Super Output Areas (LSOAs) [footnote 9]. LSOAs are small geographical areas that have an average population of 1,500, often considered as ‘neighbourhoods’. For PFAs with the required data, analysis was undertaken on LSOAs with historically high levels (top 10%) of violence offences in SV-funded areas [footnote 10].

The results from the LSOA-level SCMs support those at the whole VRU level (see previous sections), and indicate VRU and Surge activity are effectively targeting violence hotspots, with statistically significant decreases in both violence with (-2.8%) and without injury (-6.9%). Figure 2.8 presents the results from the LSOA-level SCM (‘high-violence’ neighbourhoods). The SCM produced a very closely matched synthetic control group. Shortly after introducing SV funding in April 2019 (dashed vertical line), impacts become visible [footnote 11].

Figure 2.8: Police recorded violence offences for high-violence treated areas (LSOAs) and synthetic control group.

2.3.3 Cost-benefit analysis

Cost-benefit analysis was conducted, building on the results of the impact evaluation.

Over the 18-months from when SV funding was deployed and up to the latest point where offence data were available (April 2019 to September 2020), 27,585 police recorded violence without injury offences had been avoided in treated areas, relative to the synthetic control group (see Figure 2.4). After accounting for under reporting/recording in police data (by applying a multiplier of 1.5) [footnote 12], an estimated 41,377 violence without injury offences were avoided due to SV funding.

The cost of violence without injury is estimated to be £6,480 per offence. This estimate (and that for violence with injury) is the total economic and social costs, which include the anticipation of, consequences of and response to crime [footnote 13]. Based on the number of offences avoided (41,377), the total costs avoided (benefit) were £268,125,706.

Following the same approach for violence with injury offences, an estimated 2,937 offences were avoided. After accounting for under reporting/recording in police data (by applying a multiplier of 2.6), an estimated 7,636 offences had been avoided due to SV funding. Based on the estimated cost per offence of £15,353, total costs avoided were £117,237,412.

The total costs associated with VRU and Surge activity over the same 18-month period was £121,952,973 [footnote 14]. The benefit-cost ratio (£385,363,118 total benefits divided by £121,952,973 costs) is 3.16. So, for every £1 of SV funding, there was a return on investment (as offences avoided) of £3.16.

It is important to note that the benefits are calculated based on impact estimates that have a degree of uncertainty. This uncertainty is captured within the CIs reported for each estimate (see Figure 2.4). For completeness, benefit-cost ratios were calculated for the upper and lower CIs. The benefit-cost ratio based on the lower CI was 11.07, and 0.4 for the upper CI; so, considering the uncertainty in the impact estimates, the true return on investment likely falls within the range of £0.40 to £11.07 for every £1 invested.

2.4 Wider evidence of impacts on serious violence

In this section, wider qualitative evidence from consultations with VRU stakeholders on the impact of VRUs on SV, the interaction between Surge and VRUs, and the impact of COVID-19 are considered.

2.4.1 VRU Perceptions of the impact on serious violence

Overall, VRU stakeholders were generally hesitant to attribute any changes in SV trends to VRU activity in year 2. This was due to several factors including perceptions of the impact of COVID-19 on SV incidents; the preventative nature of VRUs (relative to the enforcement focus of Surge); and VRU stakeholders feeling that the first two years of activity were having more of a tangible impact on local structures and co-ordination around the SV agenda. VRU stakeholders often felt that it was too soon to say if and how this had translated to changes in numbers, even if they were experiencing reductions in SV incidents locally.

“We can evidence that certainly knife crime is levelling out in [VRU area] and not continuing on its upward trajectory. I don’t think we can pinpoint any one bit of work though, that would say that’s causing that. It’s a whole package, and I guess it’s always going to be quite difficult with a whole-system approach to it.” Stakeholder

Despite challenges in speaking about the contribution of VRUs at the area level, in some VRUs, stakeholders noted they could link specific interventions to a decline in incidents. For example, one VRU tracked police interventions at the six- and 12-week markers of a programme for young people at most risk. The evidence showed a decline in the involvement of anti-social behaviour and criminal activity at the time points. The scale at which interventions were operating also affected VRU stakeholders’ perceptions of impact. For example, one VRU frontline stakeholder working in a village noted they had seen demonstrable changes in a young person’s life outcomes as a result of their project but, given the scale, it would not result in change at the VRU area level.

As discussed further in Chapter 4 (MA Working), in year 2, many VRUs were doing a lot of work to embed a trauma-informed approach across agencies’ workforce, including focusing on the impact of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs). Several stakeholders felt that this work would lead to system-wide changes in social work and education but noted that this would take years to translate into reductions in SV.

2.4.2 VRU and Surge interaction

As discussed further in Chapter 4 (Multi-agency working), in year 2, VRUs and Surge have increased their alignment at both the strategic and operational level, co-ordinating approaches and activity where possible. For many stakeholders, this increased alignment made it difficult for them to disentangle the impact of VRUs versus the impact of Surge on levels of SV. Where stakeholders could disentangle the two, they pointed towards Surge funding facilitating reductions in SV incidents over a short time. They found it easier to highlight the link between a particular Surge operation and subsequent changes in incidents. For example, in one VRU, an operational stakeholder highlighted that Surge funding had made a demonstrable impact on the reduction of crime locally, as they could use the funding to pay for police officer overtime so there was greater police presence on the streets.

“Actually having this [Surge] funding and allowing us to put extra cops on the street, especially during this time, has proved invaluable for us.” Operational stakeholder

Despite Surge funding having an impact in the short term, it was recognised that without being sustained, activity would increase again eventually:

“If you flood an area with police and other crime prevention functions you will have a quick impact. It doesn’t last, but at least it keeps people safe for that period.” Strategic Stakeholder

However, where stakeholders felt Surge funding activity was having an impact, they also emphasised the important role that VRU activity had played, such as identifying crime hotspots or developing awareness-raising campaigns about particular crimes alongside Surge-funded activity on the ground.

2.5 Conclusions

There is evidence of emerging impacts of SV funding, particularly for violence without injury offences. This is encouraging for VRUs (and supported by qualitative evidence) where the focus is on early intervention/prevention. Regarding SV (i.e. hospital admissions and homicides), statistically significant impacts were not detected. It will be important to monitor impacts on SV in the future, when it is anticipated the more preventative approach of VRUs will affect these longer-term outcomes. It should also be noted that the rates of SV do not appear to have increased in funded areas (relative to non-funded areas), which is a positive finding. The dual approach of prevention and enforcement from VRUs and Surge, respectively, appears to be effective and complementary.

3. VRU design, focus and models of working

This chapter describes the approach taken by VRUs to define SV and assesses the progress made by VRUs in identifying at-risk cohorts. It also sets out the evolution of the VRU models of working over year 2. The resultant effectiveness and contribution/consequences of these foci and models are discussed in the subsequent chapters of the report.

3.1 VRU definitions of serious violence and the at-risk cohorts

VRUs form a key component of the Serious Violence Strategy (2018) and, as a result, their priorities and associated definitions of what constitutes SV reflect those set out in the Strategy, associated Home Office guidance and the VRU key outcome measures (see Chapter 1 for more details). This formed the basis of the types of evidence that were drawn together over year 1 – including both hard and soft data from a range of sources – to develop SNAs. The resultant SNAs varied considerably in depth and quality, but as a minimum, sought to begin identifying the primary at-risk cohorts (i.e. individuals or groups of individuals that were at risk of becoming or remaining involved in SV) that were prevalent in each area and the hotspots (and hot times) where incidents were most likely to take place.

The SNAs provided an initial evidence-based foundation upon which to develop the first set of Response Strategies, that in turn informed the focus and activities for year 2 of the programme.

The research conducted in year 2 found that the SNAs and Response Strategies provided a deeper understanding of at-risk cohorts, an overview of existing services and a better understanding of the gaps in provision. This included some validation of the perceived key drivers of SV identified in the year 1 process evaluation, which most commonly included ACEs, deprivation/poverty and austerity measures which impacted the level of resource available to prevent and/or reduce SV.

Key findings and emerging evidence from the SNAs and Response Strategies were circulated to a variety of stakeholders and partners across most VRUs to raise awareness of the purpose and focus of their activities, and to foster engagement amongst a wide range of organisations. The reach of this specific communication varied considerably across the VRUs, with some promoting the findings amongst statutory partners, wider community and voluntary organisations and frontline practitioners that worked with the identified at-risk cohorts. Conversely, other VRUs had taken a more conservative approach which had, in the main, cascaded findings across the partners represented on their VRU Governance Boards and on the core VRU teams. This had led to lower levels of awareness of the detailed intentions of the relevant VRUs amongst some wider stakeholders and frontline practitioners, which is likely to have limited the scale of collaboration that took place within these areas.

The communication activities often involved workshops which included information sharing and feedback sessions, to engender a sense that the SNAs and Response Strategies were ‘live’ documents that would be updated on the basis of evolving local contexts, a growing evidence base and softer intelligence gathered from partners.

“We do sometimes have a conversation about do we need to revisit the serious violence definition? So, night time economy. We know community safety partnerships, have plans around that. We know there’s work around the town. High streets. Some of the funding that’s going in through the local economic partnership. So, it was like where’s the gap in provision? A lot of people who sit around our strategic board obviously sit around those other strategic boards as well [and can help identify the gaps], so this is where we need to go. The SNA has assisted us with understanding that a bit more, but it is something we need to keep under review.” VRU lead

Taken in the round, the newly established SNAs and Response Strategies and the associated communication activities resulted in many VRUs reviewing and refining their SV definitions at the outset of year 2, to:

- better reflect local need

- avoid duplication where established networks and provision were working well

- add value by addressing gaps in provision

- expand existing services where required

Consequently, some VRUs broadened their SV definition to address high incidences of specific types of SV, including those resulting from the night-time economy, county lines and domestic violence. Conversely, others narrowed their definition to avoid unnecessary duplication; for example, several VRU areas had sufficient existing domestic violence networks which freed up VRU resources to tackle other areas with little or no coordinated provision.

“There’s quite a strong structure put in place for domestic violence based on the work done 15-20 years ago. There was almost a view of domestic abuse is incredibly important, but it has its own governance framework and strategic view. So, we do not want to repeat that. We want to be a complementary piece. More generally, it was a view of like what are other parts of the system doing and where’s the gap. The gap tended to be that community violence out of the household and what did it look like? And that picture around county lines and gangs which is so difficult to measure.” VRU lead

In addition, although VRUs continued to focus their efforts on supporting young people up to the age of 25, the majority were not exclusively supporting this group, so they could offer some support to older beneficiaries where relevant. This included an expansion of work with vulnerable families in recognition that holistic approaches to supporting those most at risk of becoming involved in SV should involve whole family units. It also included a renewed focus on repeat offenders (both young people and adults) that were often ‘getting lost’ in the transition between youth offending services, the prisons estate, probation services and adult services.

“Something that we’ve got data on is around repeat offenders and repeat victims, and that’s something that we have seen a trend increasing. I think that’s quite important because actually, that suggests that those people, their risk factors for violence haven’t been addressed so therefore, they’re continuing to be violent, whether that’s related to organised crime or something else. Obviously, it’s a smallish proportion of the total of either victims or offenders, but it’s an increasing proportion and we’ve seen that over the last year, actually, that that’s increasing.” VRU Core Team Member

The SNAs also enabled VRUs to adopt place-based and people-based approaches to enable more effective targeting of their resources. These approaches were set out to varying degrees in VRU Response Strategies that were designed to articulate how they intended to respond to the needs outlined in their SNAs.

- place-based approaches – target an entire community and aim to address issues that exist at the sub-area (place) level (e.g. specific neighbourhoods); for example, some VRUs were targeting areas with high levels of deprivation, low attainment, high school exclusion rates and high levels of crime, with an aim to intervene at the earliest possible moment using a holistic approach to preventing SV

- people-based approaches – target specific groups of people or characteristics of a group of people; for example, targeting those already known to be involved in SV, or identifying at-risk cohorts such as young people on the verge of becoming not in employment, education or training (NEET) or those with behavioural problems or have experienced ACEs

Impact of COVID-19

Year 2 of the VRU programme has been significantly impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic and associated national and local lockdowns and restrictions. Nearly all interviewees consulted as part of the evaluation discussed the challenges the pandemic had posed, which at the broadest level included having to navigate disruptions and changing trends in the prevalence of different types of crime and SV. This included significant reductions in public violence over some months, alongside rising rates of what were commonly described as ‘less visible crime’ such as domestic violence and drug related-crime (see Chapter 2).

“What I think covid has potentially identified more so, is the violence in the home, domestic violence, violence against women and girls (VAWG), trends showing through our specialist charity networks an increase in calls and increasing requests for help and intervention in that space. I don’t think its necessarily changed the data… but its definitely changed the emphasis that brought it to the fore in just a very practical way – that street violence through covid and lockdown obviously declined and that exposed the fact that a lot of violence takes place in the home environment.” VRU Core Team Member

Many VRUs therefore adapted some of their work to address these new and somewhat unprecedented challenges, which involved a re-prioritisation of how some of their resource was deployed (see Chapters 4, 5, 6 and 7 for more details). Looking forwards, several interviewees from across the VRUs voiced their growing concern about the long-term effects of the pandemic, such as the economic downturn, rising levels of youth unemployment and the detrimental impacts this would likely have on mental health. They reflected that this would pose additional challenges for the work of the VRUs in the future, which may be increasingly reflected in the evolving nature of their at-risk cohorts moving forwards.

“What we have now is really worrying situation – what COVID has essentially done – we don’t know actually what is going to be created in terms of society after all of this has gone – what we do know is the economic downturn, the mental health, alcohol use, god knows what we are going to face.” VRU Core Team Member

“You’ve now got the double whammy really with the after effects of COVID, in terms of this work was hard enough in times when we were coming out of austerity. It’s going to get much harder in times when it’s getting worse and demonstrating to a vulnerable young person who’s, ‘Oh, do I go to school today and crack on with my education and get my exams, and all the rest of it, or do I go over there with that bloke who’s offering me the trainers and telling me that I can go running for him and I can be taking home £100 this evening?’ In the context we’re now going into it arguably becomes harder to influence that decision.” VRU Core Team Member

3.2 VRU models of working

The year 1 process evaluation report highlighted that most VRUs comprised at least three ‘layers’, which included a governance board, a dedicated team of strategic/operational staff commonly seen as ‘the VRU’, and an additional more localised interface that operationalised activity on the ground. For most VRUs, this manifested in a single/centralised unit model, though a small number had a hub-and-spoke structure where a core VRU team sat at the centre of local VRU teams responsible for local delivery. Regardless of the VRU structure, all VRUs were working closely with existing partnerships and local organisations to develop a more prevention-focused, holistic and coordinated approach to addressing serious youth violence.

In year 2, the structures and models utilised by VRUs were largely unchanged from year 1. One exception to this pattern was noted: where two VRUs were moving from a single/centralised structure to a ‘quasi-hub-and-spoke’ approach to enable the development and delivery of more place-based approaches. This transition was viewed more as an evolution in their model of working as their delivery has matured, as opposed to a result of their previous approach being ineffective.

A second year of delivery had also provided interviewees with more time to reflect on the challenges and benefits arising from their adopted approaches. For example, for hub-and-spoke VRUs, this included recognition of the need to ensure there was genuine co-ordination from the centre with common themes applied across the spokes, even where there was some variation within this in terms of local focus.

“There are elements that need to be pan-[region] and we see the value in that, there is a pan-[region] police force so this makes sense. But we also we have three distinct authorities that have their own needs. It is helpful to have that pan-[region] discussion but then be able to move to our local discussions and have that local steering moving forwards.” VRU lead

The balance between creating a regional approach while still allowing local areas to retain autonomy over their own needs and priorities was also a consideration in VRUs with centralised models; interviewees saw this as important to encourage stakeholder buy-in. For example, to address this, one centralised VRU had developed an elected members’ reference group, with representation from all component local authorities. This approach ensured local needs and priorities were reflected in VRU activities.

Strategic governance

In terms of strategic-level governance, the research reinforced the importance of executive boards and steering groups for facilitating true multi-agency working. Generally – as one might expect from a whole-system approach – these boards had broad, usually senior-level representation from partner agencies, including those from criminal justice, youth justice, education, health and safeguarding.

The main changes to this layer of the VRU infrastructure in year 2 included:

- a broadening of both the number and type of agencies involved, to support the development of collaborative delivery models that prevent duplication and complement existing service provision; the research found some examples of representation of service users and local communities at strategic boards; for example, one VRU had a board member with lived experience, and another had local-level steering groups working directly with local communities; a third had developed a Violence Reduction Citizens’ Advisory Panel, which feeds directly into the strategic board; some VRUs had also sought to ensure that other agencies, such as Voluntary Community and Social Enterprises (VCSEs) and faith groups, were represented at this level, and there also appeared to be increasing representation from the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) in a minority of cases

- the streamlining of wider governance boards to reduce duplication and enable a greater pooling of strategic resource to drive the relevant agendas; for example, one VRU streamlined an existing prevention board into their VRU board to ensure a more effective use of their resource

- improvements in the clarity of remit and responsibilities of the governance boards, reflecting a growth in maturity of VRUs and the associated embedding of whole-system approaches to tackle SV

No clear differences were identified between the governance structures associated with the different models of working.

Operational structures

At an operational level, the research found that core VRU teams had also expanded in terms of size and composition as year 2 progressed, with recruitment activities particularly significant in the first half of the year. Generally, and as seen in year 1, the teams had a lead, an analyst or team of analysts and researchers, public health colleagues and operational leads overseeing different aspects of activity, as well as support staff. Expansions to the core teams varied considerably across the VRUs. This included the recruitment of staff from the local Integrated Care System, children’s social care, a domestic abuse specialist, local evaluators and greater representation from the VCSE sector.

As per the findings in year 1, teams were often co-located (that is, prior to COVID-19 restrictions being implemented), and many staff had been seconded in from partner agencies, either on a full- or part-time basis. In the majority of such cases, interviewees noted that their ‘home’ roles (i.e. original roles within partner agencies) were complementary to their role in the VRU and the move had been beneficial.

The most significant change across many of the core VRU teams involved restructuring around the key priority themes or workstreams that had been identified through SNAs and Response Strategies. This form of restructuring was prevalent across both single/centralised and hub-and-spoke models, and had most commonly involved the appointment of an operational lead for each theme/workstream, who reported to the VRU lead and/or into the strategic boards via a ‘workstream sponsor’ at board level. The number and type of themes/workstreams varied across the relevant VRUs, though generally could be categorised as either operational- or policy-focused. Typical workstreams included data and evidence (including evaluation), developing capacity in communities and workforces, trauma-informed and early intervention approaches, approaches focused on violence hotspots and enforcement activities, and communication and campaigns.

Staffing challenges

Staff turnover remained a common issue in year 2, which was exacerbated by COVID-19 where staff (particularly those from public health and policing) were redeployed to their home teams to support the national response. In addition, sustainability of teams comprising primarily seconded staff also remained a concern, particularly as teams approached the point at which secondments were due to expire.

“A key organisational change has been that our public health analyst has been redeployed to the local authority due to COVID-19. Although this is unlikely to have a large impact on us, the SNA refresh and other parts of the research and evaluation strand are likely to be delayed and pushed back beyond their original schedule.” VRU lead

The root cause of both issues (when discounting for the impact of COVID-19) was perceived to be related to the short-term nature of the funding for VRUs, which led to instability and insecurity of staffing.

“This is a classic example of when you have cliff edge short-term funding, and you have good people in your team, people will always be looking over their shoulders for other things, because especially in the current climate, people need security.” VRU lead

Impact of COVID-19

While COVID-19 impacted negatively on staffing, there were some positive impacts of the pandemic in terms of providing VRUs with some ‘breathing space’ to develop their models and ways of working in more detail. Interviewees noted the pandemic had provided a ‘natural pause’ to reflect on their approaches, which had proved useful given the relatively tight timescales for the programme. Core VRU teams referenced close monitoring of the impact of COVID-19 on delivery via risk registers.

4. Multi-agency working

This chapter explores VRUs’ approaches to multi-agency working, including stakeholders’ views on the effectiveness of these approaches. It also examines the contribution of multi-agency working to VRUs’ overarching aims, both from a strategic and operational perspective.

4.1 Approaches to multi-agency working

All VRUs have focused on establishing and/or developing partnerships with a wide range of agencies. This section discusses how VRUs have worked with these partners both strategically (in terms of leadership and co-ordination) and operationally (through devolving funding, providing non-financial support and supporting professional development), and the progress made since year 1.

4.1.1 Strategic multi-agency working

VRUs typically had strategies underpinning their approach to multi-agency working. However, evidence-based principles shaped approaches in only a few cases. In two cases, VRUs used academic research and Public Health England’s ‘5Cs’ to frame their approach [footnote 15]. Other VRUs had already engaged with the Scottish VRU to identify how they could implement a similar model in their local area.

All VRUs took steps to develop shared strategic aims across partners, though approaches varied. Engagement included consultation – for example through workshops, co-production in developing SNAs and Response Strategies – and liaison to develop definitions of SV and the at-risk cohort. In all cases, board meetings were a key mechanism to maintain strategic engagement from partners. Police representatives were often on VRU boards to support the strategic alignment between VRU activity and Surge activity. Some VRU leads also attended Surge board meetings to further identify synergies and opportunities for collaboration. Regular meetings between VRU and Surge leads allowed discussions about each programme’s priorities and how to align them. In one case, the Surge lead was co-located in the VRU team and could align Surge spending with VRU activity (e.g. by allocating additional policing resource in hotspots that VRU analysis had identified). While this alignment was present in some VRUs in year 1, stakeholders noted how it had strengthened over year 2.

Similarly, approaches to multi-agency working developed in year 1, both building on existing partnerships and developing new ones, continued to develop and were strengthened in year 2. More work was done in year 2 to map existing structures and partner resources. This helped to identify and reduce the extent of duplication and siloed working across agencies. Linked to this, giving partners responsibility for workstreams helped ensure accountability and support for strategic VRU aims, whether workstreams were first developed in year 1 or new to year 2. For those building on year 1, more work had been done to operationalise the workstreams, for example by creating clear leadership and governance structures or focused operational groups. VRUs also facilitated new partnerships between agencies, in one case linking health partners with the police to develop an approach to improve patrolling in SV hotspots.

For most VRUs, the approach to multi-agency working sought to engage and involve partners across different localities. Including voluntary sector and/or community representation on boards was also acknowledged as important, whether informing VRUs’ strategic vision or to sense-check that strategy worked operationally. The ‘hub-and-spoke’ models of some VRUs naturally facilitated a locality-based approach to multi-agency working. In all of these cases, the hubs set the overall strategic direction of the VRU and the spokes operationalised this within their local context. Equally, there was evidence of multi-agency working across localities in more centralised VRU models. Several devolved the responsibility for developing and implementing local violence reduction strategies to CSPs. Others gave core team members responsibility for developing partnerships in specific geographic areas.

4.1.2 Operational multi-agency working

As discussed in Chapter 3, many VRU core teams seconded in staff from partner agencies to promote partner buy-in, as well as ensure operational-level co-ordination. Police secondments were viewed as helping to support operational co-ordination between VRU activity and Surge provision. Co-locating stakeholders also supported effective multi-agency working.

VRUs provided professional development opportunities for core team and partner agency staff as a mechanism to support consistent ways of working. For some VRUs, this included training and development to facilitate a trauma-informed approach [footnote 16]. For example, one VRU worked with local prisons and provided trauma-informed training to staff in the custodial estate. Devolving funding to partners also formed a key mechanism to facilitate multi-agency working at the operational level. Several VRUs devolved funding to CSPs to implement local Response Strategies, while funding local community organisations to respond to SV in specific locations/neighbourhoods was also common.

4.2 Effectiveness of approaches to multi-agency working

Across all VRUs, activity to develop multi-agency approaches was generally seen as effective. Overall, VRUs appeared to have made good progress in year 2 in building on existing partnerships and aligning structures, strategies and partners. There was consensus that VRUs had effectively mapped out and consolidated meetings and partnership mechanisms. However, there were still some concerns about activity being duplicated and partners being overburdened by VRU responsibilities. Strategic and operational stakeholders with this view often spoke about challenges for partners for whom SV is not a ‘focus of their day job’, perhaps indicating that more work is needed to truly embed the whole-system approach.

There was strong evidence of VRUs making progress in encouraging partners to take shared ownership of strategic aims. This progress occurred throughout year 2 and it was common for strategic stakeholders to flag that this process took time, particularly with some partners such as health and education, who often had less engagement due to having to focus on the immediate COVID-19 response.

Across strategic and operational stakeholders, there was generally a consensus that VRUs had been effective in providing partners (and their staff) with support and resources to engage in a multi-agency approach. VRUs were likewise viewed as an important additional resource to oversee and co-ordinate activity. However, some stakeholders within hub-and-spoke or locality models felt that occasionally the model could complicate the implementation of a multi-agency approach and hence compromise effectiveness. The sheer size of the VRU area and competing local/spoke-VRU priorities were cited as factors in this.

4.2.1 Enablers of effective multi-agency working

Additional enablers for multi-agency working, beyond those detailed above, included:

- perceived credibility of the VRU in engaging partners, as well as senior representation from those partners, helping to reinforce the multi-agency, partnership-based nature of the VRUs

“Whether it’s programmes or policies, people feel like they can trust that because it’s coming from a place that’s been done, ultimately, with the backing of the Home Office… it is a partnership-led initiative, so I think that’s been really important, that leadership and communications aspect of us having a common goal to reduce violence.” Operational external partner

-

although the involvement of different partners was important, the perception of the VRU being a unit independent of the police was an important enabler for building trust with communities and community organisations

-

as well as creating shared ownership through initial consultation work and co-production to inform SNAs and Response Strategies as outlined above, publishing these documents indicated outwardly that partners were engaged and supported the VRU’s aims

-

clearly articulating the approach helped agencies to decide whether they would engage in the partnership; this was especially important for operational and frontline stakeholders; strategic stakeholders said it was important to get partners to understand that “they are a cog in a much bigger wheel”; for partners to see where their role fits in the SV reduction agenda alongside other agencies; operational stakeholders noted that a concise SNA and response strategy, clear terms of reference setting out responsibilities, sharing information, government guidance and strategy, all helped to communicate the approach

“For me, open honesty [and] commitment to work as a partnership is really important… it’s around that sharing of information and having a rich picture of information to actually tackle the most significant issues.” Operational external partner

-

the interpersonal skills, drive and leadership of VRU leads was a key enabler to keep strategic members engaged; strong relationships established prior to VRUs facilitated multi-agency working, reiterating the importance of the person leading the VRU; however, it was acknowledged that this may not be sustained should they leave

-

additional focused resource from the VRU to co-ordinate activity was noted as a key enabler; VRUs helped stakeholders to ‘focus minds’ and to identify opportunities for collaboration; ultimately, this was seen as supporting the development of a whole-system approach to tackle the cross-cutting issue of SV

“The fact that there is this pure focus on serious violence is very helpful as a way to bring people together and put fresh eyes on a particular issue, because if you’re siloed into one way of working, say around crime, youth crime, you’re not necessarily looking wider. Or, you’ll know that trauma’s a factor, but when you’ve got a VRU, it’s enabling more focus on trauma.” Strategic stakeholder

-

strategic stakeholders highlighted the role (and potential further role) of wider policy that facilitated multi-agency working to tackle SV; some partners from statutory agencies mentioned the Serious Violence Duty (Home Office, 2019), which required them to develop their own SNAs and thus inform their response; they also felt the VRU added value by supporting agencies to access different datasets and enrich their analysis, although there was a concern about potential duplication

-

with the sustainability of the whole-system approach in mind, some VRUs have tried to ensure that they support multi-agency working at the operational level through engaging local community organisations; several VRU leads highlighted how, through commissioning interventions, they were trying to build the capacity and capability of the community sector; for example, one VRU-supported networking between grassroots organisations to facilitate the development of a consortium that could later bid for funding/work

-

strategic and operational stakeholders from several VRUs commented that a positive consequence of COVID-19 and the shift to virtual working had facilitated closer multi-agency working in some ways because people could make meetings more regularly than they could before COVID

4.2.2 Barriers to effective multi-agency working

Barriers included:

-

competing strategic priorities within partner organisations meant they could not always take full ownership of the VRU’s strategic vision; stakeholders noted that there was a risk, especially for statutory organisations (e.g. police, local authorities), that changes in political leadership could affect engagement

-

a perceived lack of central government direction, fully embedded across all departments, was viewed as a barrier; it was felt that greater cross-departmental buy-in and direction of the violence reduction agenda would ensure a stronger mandate for all partners to be involved and to take more ownership and accountability for delivering the vision

“If… the centre of Government were seeking a multi-agency response then we should be able to get briefings about the existence of the VRU as well as leverage and encouragement to engage to come down through the NHS, the Department of Health, the Department for Education. It feels to me entirely absent at the moment, this encouragement and support for the VRUs to be multi-agency, through any government department bar the Home Office.” Strategic Stakeholder

- stakeholders in multiple VRUs still had concerns that the VRU was too police-led, which acted as a barrier to engagement from other partners; strategically, this meant that some partners took a step back from taking ownership of the response, while operationally it could erode trust; for example, one VRU employee highlighted how their email address had ‘police’ in it and felt that this could be a barrier