UK-Switzerland Enhanced FTA Strategic Approach Chapter 4: Scoping Analysis

Published 15 May 2023

For further information, see the full UK approach to negotiating an enhanced free trade agreement with Switzerland.

Introduction

The Scoping Analysis sets out the potential economic impact of a renegotiated UK-Swiss Confederation (Switzerland) free trade agreement (FTA).

The United Kingdom (UK) currently trades with Switzerland under the UK-Switzerland Trade Agreement, which came into force on 1 January 2021. This agreement replicates the existing trade agreements between the European Union and Switzerland as far as possible. There is no single comprehensive trade agreement between the EU and Switzerland but a series of smaller agreements that have been built up over 45 years. These agreements focus mainly on trade in goods, whilst also addressing some other areas such as government procurement.

There is no comprehensive agreement on trade in services to replicate, but in 2020 the UK and Switzerland secured the Services Mobility Agreement (SMA), which allows UK professionals to work in Switzerland for up to 90 days without a work permit. This came into force on 1 January 2021 and is set to expire on 31 December 2025. In 2022, the UK and Switzerland signed the Mutual Recognition Agreement on goods (MRA) which has been applied provisionally since 1 January 2023. This applies to a specific set of goods which when tested in the UK against Swiss regulations can be sold in Switzerland without additional testing in Switzerland.

The Department for Business and Trade (DBT) is preparing for negotiations to upgrade the current set of agreements to a new, modern, and comprehensive Trade Agreement. It will be adapted to build on the strengths of the UK and Switzerland, focusing on areas not significantly covered by the existing agreement such as services, mobility, and investment. A new agreement with Switzerland is expected to present new opportunities in services sectors, such as financial services, professional and business services, digital services, and new opportunities in goods trade through opened market access and simplified Rules of Origin (RoO) and customs.

As a member of the European Free Trade Association (EFTA), Switzerland has normally concluded FTAs together with Norway, Iceland and Liechtenstein. In 2021, the UK signed an agreement with Norway, Iceland, and Liechtenstein (the EEA EFTA States). Switzerland can negotiate bilateral agreements outside this framework, as in the case of agreements with Japan (2009) and China (2013).

About scoping analysis

Scoping Analysis is used where the negotiations cover an augmentation of an existing trade agreement and focus on where the UK can make additional gains. It uses tools including tariff analysis and descriptive analysis as the main evidence base to highlight where there are remaining barriers to trade. Given there is an existing FTA in place already, it does not include economic Computable General Equilibrium (CGE) modelling which estimates the potential impacts on the macroeconomy. Tools such as CGE modelling and services gravity modelling can also not be deployed in this instance due to data limitations.[1]

At the end of negotiations, an Impact Assessment will be published.

A note on data and statistics

Statistics in this scoping analysis are based on 2022 or the latest available data as of May 2023, unless otherwise specified. Tariff liberalisation analysis uses 2018 to 2020 average trade flow data. Due to the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, trade data was more volatile in 2020 and 2021.

The rationale for a bilateral FTA with Switzerland

-

This is an opportunity to expand the scope and depth of existing arrangements with an important trading partner. Trade between the UK and Switzerland has quadrupled over the past 20 years to reach £52.8 billion in 2022. The current agreement is predominantly goods focussed and does not include areas associated with more modern and comprehensive FTAs. Renegotiations provide an opportunity lock in existing benefits and expand to cover a broader number of key areas of shared strength including services, digital and data, and the environment.

-

There are particular opportunities to increase trade in services and investment, a key driver of economic growth in both countries. As services represent over 70% of GDP for both economies, the UK and Switzerland have much to gain from enhancing the current agreement. The current agreement does not include services provisions, yet nearly half of bilateral trade is in services. The FTA provides a chance to remove non-tariff barriers and support further growth in these areas. There is also an opportunity to embed and build on existing arrangements under the Services Mobility Agreement to facilitate the movement of skilled business persons and make it easier to deliver services in both countries. In 2019, there were an estimated 383,000 business visits from the UK to Switzerland and 229,000 visits in the other direction. The deal could support trade in vital sectors such as financial services, professional and business services, and life sciences.

-

A bespoke FTA could foster conditions to support and promote innovation between 2 of the top innovative nations, including in digital and emerging technologies. There are opportunities for the UK and Switzerland to agree to cutting edge digital and data provisions that support all sectors of the UK economy to trade online. Digitally delivered services accounted for 69% of UK services exports to Switzerland in 2019, rising to 80% in 2021, in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Both countries’ shared values also provide significant opportunities for greater cooperation in areas of mutual interest that trade can support, such as ambitions for tackling climate change and promoting green technology.

-

An enhanced FTA could support UK businesses to export into the Swiss market by reducing or eliminating burdensome tariffs. There is also an opportunity to negotiate the reduction or removal of existing tariffs on agricultural goods not covered by the current trade agreement. Removing the remaining tariffs on UK exports to Switzerland could reduce the current estimated £7.4 million duties paid on exports. Swiss tariffs on some products, such as red meat, chocolate and baked goods, are currently very high, with businesses describing them as a key barrier to trade.

-

An upgraded agreement will bring further economic opportunities for the whole of the UK and support small and medium enterprises (SMEs) across the country to benefit from trade. A new FTA with Switzerland will provide increased opportunities for businesses across the UK that are involved in trade with the country. As well as supporting regions like Northern Ireland and the East of England by reducing tariffs, a new agreement will benefit the UK’s world-leading services companies, such as the top financial services firms based in London, Scotland and the North West. In 2021, 14,100 UK businesses exported goods to Switzerland, of which 86% were SMEs. This agreement could support SMEs trade with Switzerland by streamlining existing complex arrangements, simplifying and digitalising customs procedures and ensuring SMEs can access the wider benefits of a new FTA.

The existing trade and economic relationship between the UK and Switzerland

Total trade in goods and services between the UK and Switzerland was worth £52.8 billion in 2022, which consisted of £33.3 billion of UK exports to Switzerland and £19.5 billion of UK imports from Switzerland. Switzerland was the UK’s 10th largest trading partner in 2022.[2] In 2021, 14,100 UK businesses exported goods to Switzerland, of which 86% were SMEs.[3]

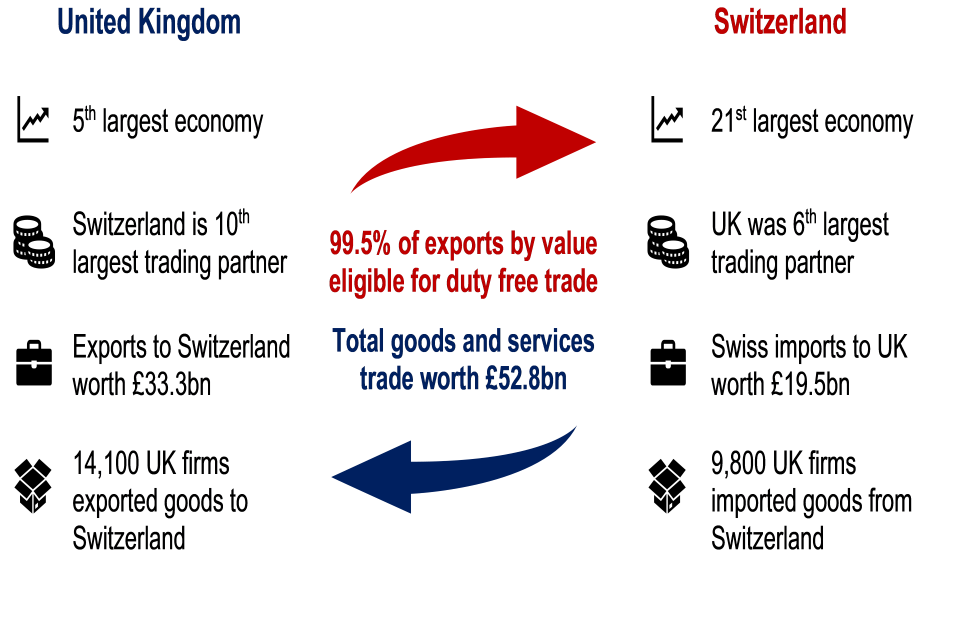

Figure 1: Economic indicators for the UK and Switzerland

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook (October 2022); World Integrated Trade Solution (WITS); ONS UK total trade: all countries, non-seasonally adjusted, April 2023 edition; HMRC UK trade in goods by business characteristics 2022.

Figure 1 highlights key economic and trade indicators for the UK and Switzerland. The UK and Switzerland are the fifth and 21st largest economies respectively. Switzerland is the UK’s 10th largest trade partner and the UK was Switzerland’s sixth largest trade partner is 2020. Exports to Switzerland were worth £33.3 billion and Swiss imports to the UK worth £19.5 billion with total trade worth £52.8 billion. 14,100 UK firms exported goods to Switzerland, and 9,800 UK firms imported goods from Switzerland. 99% of exports by value are eligible for duty free trade.

Trade in services

Services activity accounts for the majority of UK economic activity and a large proportion of exports. In 2021, the sector provided 80% of UK economic output by value, a high proportion even among developed economies.[4] Total trade in services with Switzerland in 2022 was worth £23.7 billion, made up of £14.9 billion of UK exports and £8.8 billion of UK imports.[5]

The top services trade between the UK and Switzerland in 2022, shown in Figure 2, was other business services, 53% of total services trade.[6] 77% of imports and 44% of exports in this category were professional and management consulting services. Other key exports were financial services and telecommunications, which together with other business services made up 73% of all UK services exports to Switzerland. The other top services imports were transportation and travel, which together with other business services, made up 77% of total services imports from Switzerland in 2022.

Figure 2: Key services traded between the UK and Switzerland in 2022

| Key imports by the UK from Switzerland in 2022 | Value of services imported |

|---|---|

| Other business services | £5.4 billion |

| Transportation | £0.8 billion |

| Travel | £0.72 billion |

| Intellectual property | £0.65 billion |

| Financial | £0.37 billion |

| Key exports from the UK to Switzerland in 2022 | Value of services exported |

|---|---|

| Other business services | £7.3 billion |

| Financial | £2.3 billion |

| Telecommunications, computer and information services | £1.3 billion |

| Transportation | £1.1 billion |

| Travel | £1 billion |

Source: ONS UK trade in service: service type by partner country, non-seasonally adjusted, April 2023 edition

Trade in goods

Total trade in goods with Switzerland increased from £11.6 billion in 2012 to £29.2 billion in 2022, a 152% increase. The UK exported around £18.5 billion of goods to Switzerland in 2022.[7] The UK’s top export category was unspecified goods (£12.1 billion) making up 65% of total exports. According to HMRC data, 99% of this was non-monetary gold (gold bullion, gold coin, unwrought or semi-manufactured gold and scrap), which is sometimes excluded from trade statistics due to its volatility and neutral direct impact on GDP.[8] The UK’s other top exports were non-ferrous metals, works of art and medicinal and pharmaceutical products. These 3 products together accounted for 14% of all UK goods exports to Switzerland in 2022.[9] Across 2018-2020, 99.5% of the value of exports (79% of tariff lines) to Switzerland were eligible for tariff-free trade.[10]

Similarly, the UK imported around £10.7 billion of goods from Switzerland in 2022.[11] Medicinal and pharmaceutical products was the UK’s top goods imports from Switzerland, followed by non-ferrous metals and photography equipment and clocks, as shown in Figure 3.[12] Together, these 3 product groups accounted for 41% of all UK goods imports from Switzerland in 2022. Across 2018-2020, 99.7% of the value of imports (81.1% of tariff lines) from Switzerland were eligible for tariff-free trade.[13]

Figure 3: Key goods traded between the UK and Switzerland in 2022

| Key imports by the UK from Switzerland in 2022 | Value of goods imported |

|---|---|

| Medicinal and pharmaceutical products | £1.7 billion |

| Non-ferrous metals | £1.5 billion |

| Photographic and optical goods and clocks (consumer) | £1.2 billion |

| Unspecified goods | £0.76 billion |

| Works of art | £0.44 billion |

| Key exports from the UK to Switzerland in 2022 | Value of goods exported |

|---|---|

| Unspecified goods | £12.1 billion |

| Non-ferrous metals | £1.3 billion |

| Works of art | £0.65 billion |

| Medicinal and pharmaceutical products | £0.61 billion |

| Jewellery | £0.45 billion |

Source: ONS Trade in goods: country-by-commodity imports and exports, April 2023 edition.

The existing UK-Switzerland trade agreement has ensured that UK exports have preferential access to the Swiss market. Were the UK trading on most favoured nation (MFN) terms, UK exports would have incurred estimated annual duties of £42 million. The preferential tariffs under the existing agreement reduce annual duties on UK exports.[14]

Both Swiss exporters and UK businesses importing from Switzerland have also benefited from preferential access to the UK market. Were the UK trading on MFN terms, UK imports would have incurred estimated annual duties of £45 million, with preferential tariffs reducing these.

The products that could have benefited most from tariff reductions are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Maximum annual reduction in tariff duties on exports and imports available to business for the top 10 HS chapters under the current UK-Switzerland TA were preferential duties fully utilised (£ million)

| Imported goods | Maximum annual reduction in tariff duty |

|---|---|

| Organic Chemicals | £7.5 million |

| Miscellaneous edible preparations | £4.3 million |

| Plastics | £4 million |

| Dairy products | £3.3 million |

| Aluminium | £3 million |

| Footwear | £2.9 million |

| Non-knitted clothing | £2.3 million |

| Machinery and mechanical appliances | £2.3 million |

| Vehicles excluding rolling stock | £1.8 million |

| Electrical machinery | £1.7 million |

| Exported goods | Maximum annual reduction in tariff duty |

|---|---|

| Vehicles excluding rolling stock | £5.7 million |

| Aluminium | £3.9 million |

| Plastics | £3.4 million |

| Perfumes and cosmetics | £2.2 million |

| Paper and paperboard | £2.2 million |

| Miscellaneous edible preparations | £1.8 million |

| Dairy products | £ 1.8 million |

| Non-knitted clothing | £1.5 million |

| Machinery and mechanical appliances | £1.4 million |

| Beverages | £1.2 million |

Source: DBT calculations using tariff data from DBT, ITC Market Access Map (MacMap), and WTO TAO and annual import data averaged over 2018-2020 (Swiss import data from ITC TradeMap and UK import data from HMRC). It assumes full utilisation of tariffs and compliance with rules of origin requirements.

Economic analysis of a bespoke UK-Switzerland FTA

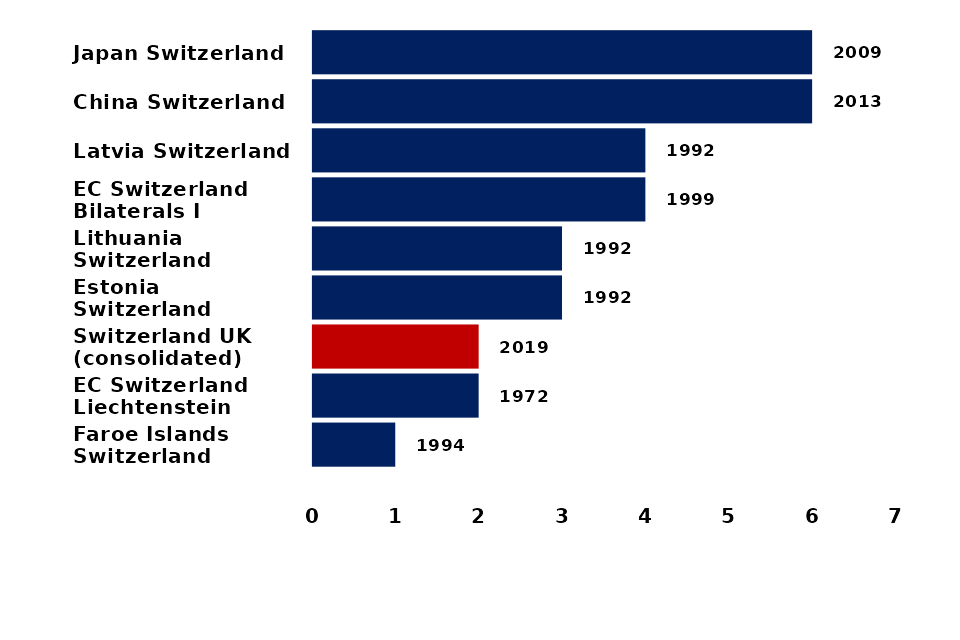

The current trade agreement between the UK and Switzerland is relatively shallow, reflecting the depth of the European Commission (EC) Switzerland Liechtenstein (1972) agreement upon which it is based. Figure 5 shows academic research into the depth of agreements to compare across FTAs Switzerland currently has in force. The UK’s existing relationship ranks comparatively poorly here, as in recent years Switzerland has negotiated increasingly ambitious trade agreements. Their latest agreements with Japan (2009) and China (2013) rank first and second.

Figure 5: Depth of Switzerland’s FTAs, as measured by the Design of Trade Agreements (DESTA) index (max = 7)

Source: Dür, Andreas, Leonardo Baccini and Manfred Elsig. 2014. “The Design of International Trade Agreements: Introducing a New Database”. Review of International Organizations, 9(3): 353 to 375.

Note: The index measures the scope of trade agreements by identifying seven key provisions that can be included, with agreements scored based on whether they contain substantive provisions in each area. UK (consolidated) refers to EC Switzerland Liechtenstein (1972) and UK Switzerland Temporary Services Agreement (2019) but not others such as the Service Mobility Agreement (2020). When consolidating, the presence of provisions takes precedence over the absence of provisions.

Some deeper Swiss agreements include provisions on intellectual property, cross-border investment, and services trade. Call for Input respondents highlighted that these are areas that they would like to expand on in a bespoke UK-Switzerland FTA.

A more modern and deeper FTA would benefit businesses, given the size of Switzerland’s import market and similar consumer preferences. Switzerland consumers have relatively high incomes, with a GDP per capita of $92,000 in 2021, and between 2021 and 2035 its import market is expected to grow by 54% in real terms.[15]

A deeper agreement could include comprehensive mobility commitments, and provisions on investment and financial services. This section explores the potential benefits that could follow a deeper agreement in these and other areas.

Trade in services

Both the UK and Switzerland are services-focused economies, with 80% of the UK’s and 74% of Switzerland’s value added coming from services sectors, though services accounts for around half of bilateral trade.[16] Both the UK and Switzerland also have highly educated workforces, ranking first and fifth respectively amongst G20 economies for the proportion of the workforce with advanced education.[17]

Switzerland is more restrictive to trade in services than the UK and OECD average for 19 out of the 21 sectors with data. Relative to the OECD, Switzerland is most restrictive in postal and courier, broadcasting and commercial banking services.[18]

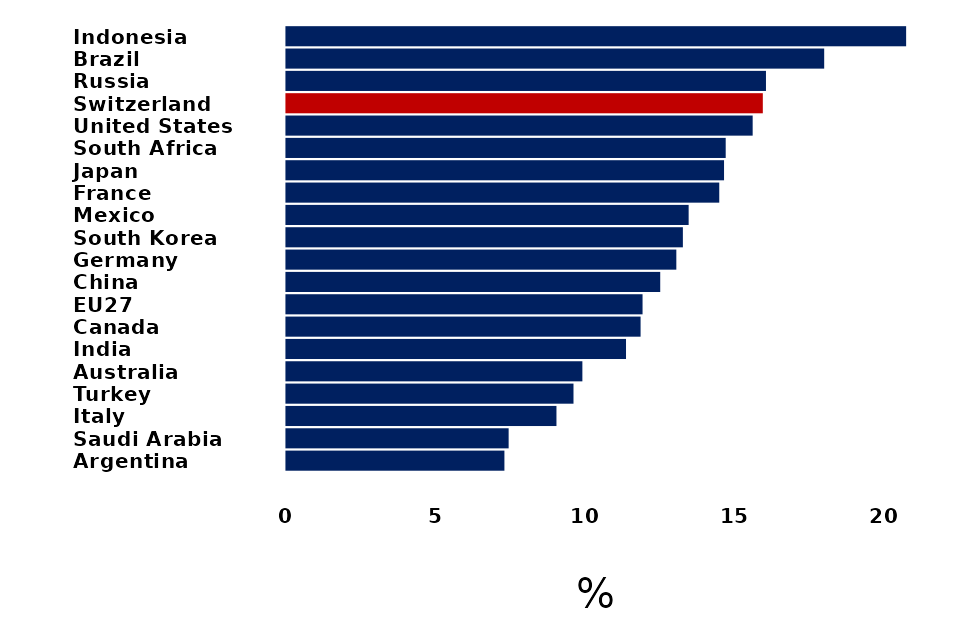

Many Call for Input responses noted their desire for services provisions in a new agreement including areas such as recognition of professional qualifications and stronger mobility commitments, including procedural facilitation and comprehensive sectoral coverage. In 2019, 16% of the UK’s services exports to Switzerland were conducted via Mode 4, the movement of natural persons. Figure 6 shows this to be the fourth largest of any of the UK’s G20 trading partners. In 2019, there were an estimated 383,000 business visits from UK residents to Switzerland, and 229,000 business visits from Switzerland to the UK.[19]

Switzerland’s is the third most restrictive in the OECD for movement of persons, more restrictive than the UK in 20 of the 21 sectors with complete data. Whilst the SMA represents a liberal approach, stronger commitments on mobility present significant value for the UK.

Figure 6: Proportion of UK Services Exports (Modes 1, 2 and 4) delivered by Mode 4 with G20 and Switzerland

Source: ONS Trade in services by mode of supply, 2019 edition. Note: 2019 is preferred to the latest data (2021) due to the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on cross border travel in 2020 and 2021.

The SMA, which came into force on 1 January 2021, reduced restrictions on the movement of highly skilled businesspersons between the UK and Switzerland. Securing comparable outcomes to those that UK businesses currently benefit from will provide certainty to businesses currently taking advantage of the agreement and reduce disruption. There is opportunity to go beyond the provisions in the SMA, where possible, to further reduce barriers to trade in services.

The most direct benefit of liberalising travel restrictions is to reduce costs. As 2 of the most innovative and highly educated economies there are also significant opportunities to accumulate and transfer knowledge between the 2 countries.[20]

Key sectoral opportunities in the FTA

The Call for Input identified these sectors amongst priorities for the FTA.

Financial services

-

Financial Services (FS) constitutes a major industry for both the UK and Swiss economies, with London, Edinburgh, Geneva and Zurich developing a reputation for being some of the leading financial centres globally.[21]

-

In 2022, Switzerland was the UK’s eighth largest FS trading partner, with trade amounting to £3.3 billion, of which £2.6 billion was in the form of UK exports, equivalent to 18% of total service exports from the UK to Switzerland.[22]

Professional and Business Services:

- The Professional and Business Services (PBS) sector covers a range of knowledge-intensive industries including legal services, accounting, advertising, architecture, engineering, consulting and many other professional, administrative and support activities.[23]

- Trade in PBS with Switzerland is a key part of the UK economy, with Switzerland ranking as the UK’s second largest PBS trading partner.[24] In 2022, total PBS trade with Switzerland amounted to £9.2 billion (39% of total UK services trade with Switzerland), with UK exports of PBS accounting for £5.0 billion (33% of total UK services exports to Switzerland).

- The largest contributors to PBS exports were management consulting services (37% of UK PBS exports) and research and development services (25%).

- Recognition of professional qualifications could be a valuable facilitator of trade in PBS, with CFI respondents noting a particular interest in this area.

Life Sciences

- The life sciences sector is among the most valuable and strategically important in the UK economy covering medical technology and pharmaceuticals.[25]

- In 2022 Switzerland was the UK’s 8th largest life sciences trade partner, with total trade amounting to £2.4 billion. UK exports of life sciences to Switzerland amounted to £0.6 billion, ranking Switzerland as the UK’s ninth largest life sciences export partner. Exports are primarily of medicinal and pharmaceutical products, accounting for 95% of exports.[26]

Digital trade

Most of the services trade between the UK and Switzerland is delivered remotely, demonstrating the importance of digital trade between the 2 countries. Around 69% of UK services exports to Switzerland and 66% of UK imports were delivered remotely (mode 1 of services trade) in 2019.[27] These shares rose to 80% and 75% respectively in 2021, in the context of the global COVID-19 pandemic.[28]

Switzerland has lower barriers to digital trade than the OECD average and has the same level of restrictiveness as the UK.[29] Barriers around infrastructure and connectivity, as well as electronic transactions, are the main impediments to digital trade in the UK and Switzerland, accounting for 66% and 34% of restrictions respectively for both countries.[30] These barriers have led to Switzerland and the UK ranking as the joint third most open to digital trade of the 38 OECD countries.[31]

In the Call for Input, respondents called for a digital chapter to enshrine commitments on cross-border data flows and maximise collaboration on data sharing. Maintaining the ability for firms to transfer data across and between countries, including Switzerland, is an important channel by which the UK can promote cross-border digital trade.

Foreign direct investment

FDI is an important contributor to economic growth due to its potential to enhance productivity and innovation, create employment, and benefit a broad range of sectors and regions. The stock of inward FDI from Switzerland into the UK was £74 billion in 2021, the 8th largest inward FDI position.[32] Between December 2012 and December 2022, there were over 400 Swiss greenfield FDI projects started in the UK.[33] The 3 sectoral clusters with the greatest number of projects, were professional services, retail trade and financial services. This included projects in all the nations and regions in the UK. There were over 100 projects started across Scotland, Yorkshire and the Humber, and the North West across a range of sector clusters. The sectors with the most projects in these regions were financial services, retail trade, and professional services respectively.

In 2021, the outward stock of FDI from the UK in Switzerland was £52 billion, the ninthlargest outward position.[34] Between December 2012 and December 2022, 117 British FDI projects were started in Switzerland, the majority of which fell under the financial services and professional services sector clusters.[35]

Switzerland is more restrictive than both the UK and the OECD average to receiving inward FDI.[36] Switzerland’s higher restrictiveness index is driven by a small number of sectors, particularly electricity, real estate and broadcasting where the most significant barrier is due to equity restrictions. This limits the extent of foreign ownership permitted in companies or in the aggregate of companies in these sectors. Switzerland is also more restrictive than the UK in banking and other finance. There may be opportunities to facilitate greater UK FDI by reducing restrictions in some of these sectors. Expanding mutual FDI flows may deepen links between both countries and encourage trade growth.

Trade in goods

The UK exported around £18.4 billion of goods to Switzerland in 2022. Although the UK’s existing agreement ensures that 99.5% of the value (79% of tariff lines)[37] is eligible for tariff-free trade, there are several sectors eligible for significant tariff reductions. Call for Input respondents asked to retain preferential tariffs and for greater liberalisation where possible. Removing the remaining tariffs on UK exports to Switzerland could reduce the current estimated duties of around £7.4 million.[38]

There is also a subset of goods with particularly high tariffs; over 200 products have an estimated ad valorem equivalent tariff of over 100%.[39] Affected sectors include meat and offal, vegetables, animal and vegetable fats and dairy products. Reducing or removing these tariffs may help open new markets for UK agricultural exporters.

Eliminating the remaining tariffs on UK imports could reduce the duties of £1.1 million on current imports. This would predominantly benefit importers of beverages, fish and crustaceans, miscellaneous edible preparations (for example, extracts, yeasts, seasoning), and could result in lower prices for UK consumers.[40]

Utilisation of the agreement

Usage of preferential tariffs in the UK-Switzerland trade agreement for UK exports is lower than some other UK FTAs. Barriers to usage could include, but are not limited to, meeting rules of origin requirements and customs procedures. Many Call for Input respondents expressed the need for simplification of customs paperwork and border control. This may particularly affect SMEs due to the time and cost of administrative burdens.

The average preference utilisation rate (PUR) for UK exports to Switzerland in 2019 was 57%. This means that 57% of UK exports that were eligible for preferential treatment were exported to Switzerland under preferential terms, with the remainder exported under MFN terms. The chemical products sector represented around half of the value of exports eligible for preferential tariffs, however utilisation of preferences was just 67%.[41]

Consolidating the existing agreements into a single modern and comprehensive FTA, as well as the inclusion of an SME chapter, could make the agreement more accessible to SMEs. By enhancing the current agreement, there is an opportunity to further reduce existing barriers, resulting in higher utilisation of preferential tariffs and lower costs for businesses. An illustrative 5 to 10 percentage point increase in the use of available preferences across all products would reduce annual duties on UK exports to Switzerland by £1.8 million to £3.5 million.[42] Increasing utilisation is necessary to realise maximum tariff liberalisation savings.

The average preference utilisation rate for UK imports from Switzerland in 2019 was 90% with most sectors above 80%. The sectors with the most trade eligible for preferential tariffs were optical and other apparatus, machinery and mechanical appliances and chemical products. Utilisation of preferences in these sectors was in line with utilisation in other sectors.

Encouraging greater innovation

The UK and Switzerland are among the world’s most innovative economies, having been ranked fourth and first respectively in the Global Innovation Index.[43] Both countries have large digital and scientific industries. Switzerland is a global leader in research and development (R&D) expenditure as a proportion of national income, ranking 8th globally, spending over 3% of GDP on it in 2019.[44] Furthermore, amongst the ten countries with the highest business-funded R&D expenditure in an EU R&D index, Swiss firms average the highest level of R&D intensity (ratio of a company’s R&D expenditure to net sales).[45] pharmaceuticals and biotechnology was the largest driver of R&D expenditure amongst the Swiss companies studied, accounting for 66% of R&D expenditure from Swiss companies.[46]

The UK’s ambition is that trade agreements with innovative economies, such as Switzerland, go beyond precedent and have sufficient flexibility to adapt to changes in what and how both countries trade as the economies grow and develop.

Intellectual property

Innovation relies heavily on effective intellectual property (IP) rights. Call for Input respondents highlighted the need to lock in and go beyond current existing intellectual property rights, with emphasis on copyright and enforcement law.

This is significant for both the UK and Switzerland as the seventh and eighth ranked economies for number of patents granted in 2021.[47] Amongst the 25 countries the UK exports the most services to, Switzerland ranks fifth for the proportion of those exports that are charges for intellectual property, over half of this comes from licenses for the outcomes of research and development. In the other direction, Switzerland is the UK’s fifth largest partner for intellectual property imports.[48]

Promoting R&D, through strong and balanced IP provisions and simplified regulations, would benefit both the UK and Switzerland. Traditionally, high-tech manufacturing, transport equipment, and life sciences encompass the most patent-intensive sectors in the UK so may benefit most from opportunities in this area.

Wider economic impacts

An enhanced FTA provides the opportunity to:

Support both small and large businesses that trade with Switzerland

The Call for Input responses highlighted the importance of provisions for SMEs to provide extra support to develop their business in the Swiss market. In 2021, 14,100 UK businesses exported goods to Switzerland and 9,800 UK businesses imported goods from Switzerland, of which 86% (12,100) and 80% (7,800) respectively were SMEs.[49] Provisions supporting SMEs provide the opportunity to increase the number of businesses of all sizes trading with Switzerland.

Supports women’s access to the benefits of trade

Experimental analysis published by DBT and the Fraser of Allander Institute shows that, in 2016, 64% of full-time equivalent jobs directly and indirectly involved in exports were held by men, with the remaining 36% filled by women. As opportunities are created for workers, businesses and consumers, the UK and Switzerland can work together to overcome the barriers to trade experienced by women. This FTA provides the opportunity to advance gender equality in trade.

Support UK jobs across all regions

Exports to Switzerland supported around 143,000 jobs in the UK in 2018, over 75% of which were in service sectors.[50] In addition, 3.4 million people were employed by UK businesses that exported goods to Switzerland in 2021.[51] London, the South East, and the East had over 2,900, 2,600, and 1,500 businesses exporting goods to Switzerland in 2021, respectively, with these top regions having a combined value of over £3.0 billion.[52]

Around 40% of the UK’s services exports to Switzerland originated outside of London and the South East in 2020.[53] Scotland and the North West each exported over £700 million of services to Switzerland, 30% of which was in financial and insurance services. The East exported £1.2 billion of services, including £800 million in professional, scientific, and technical activities. Wales exported £175 million to Switzerland in 2020, its largest export was in financial and insurance services.

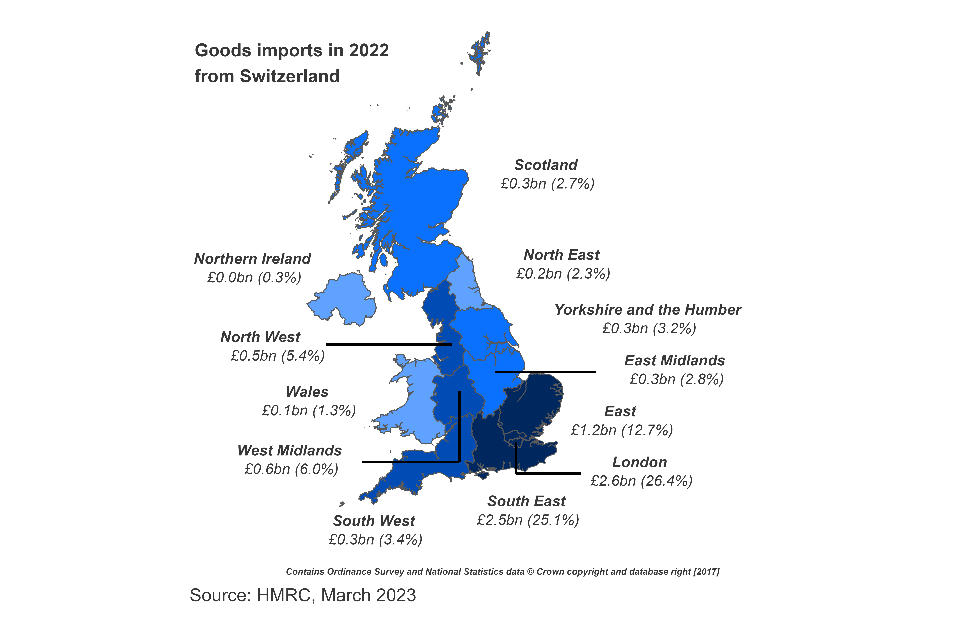

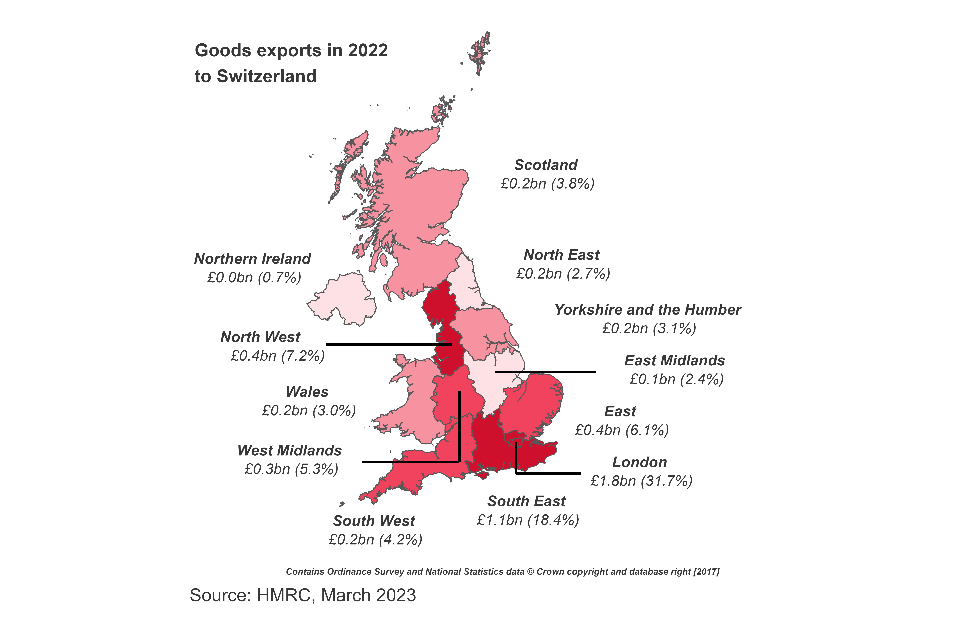

Figure 7: Regional trade with Switzerland in 2022

Figure 7 shows 2 maps of the United Kingdom, coloured according to the share of goods, imports and exports between the nations of the UK and English regions, and Switzerland. Regional imports, in descending order, are split between London (26.4%), the South East (25.1%), East (12.7%), West Midlands (6%), North West (5.4%), South West (3.4%), Yorkshire and the Humber (3.2%), East Midlands (2.8%), Scotland (2.7%), North East (2.3%), Wales (1.3%) and Northern Ireland (0.3%).

In descending order, the exports are split between London (31.7%), the South East (18.4%), North West (7.2%), East (6.1%), West Midlands (5.3%), South West (4.2%), Scotland (3.8%), Yorkshire and the Humber (3.1%), Wales (3.0%), North East (2.7%), East Midlands (2.4%) and Northern Ireland (0.7%).

Source: HMRC Regional Trade Statistics (data extracted from the interactive tables) [54]

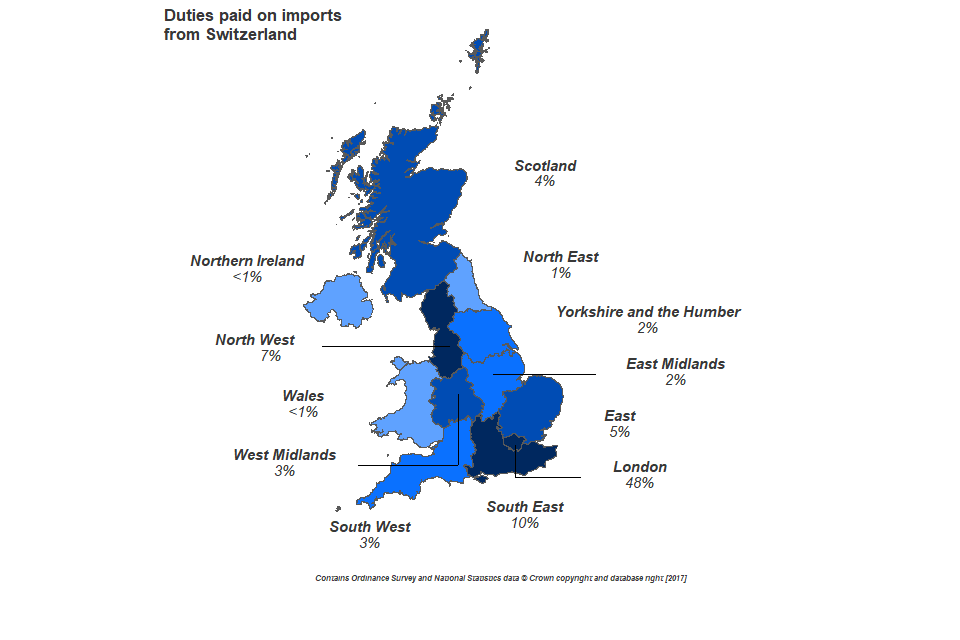

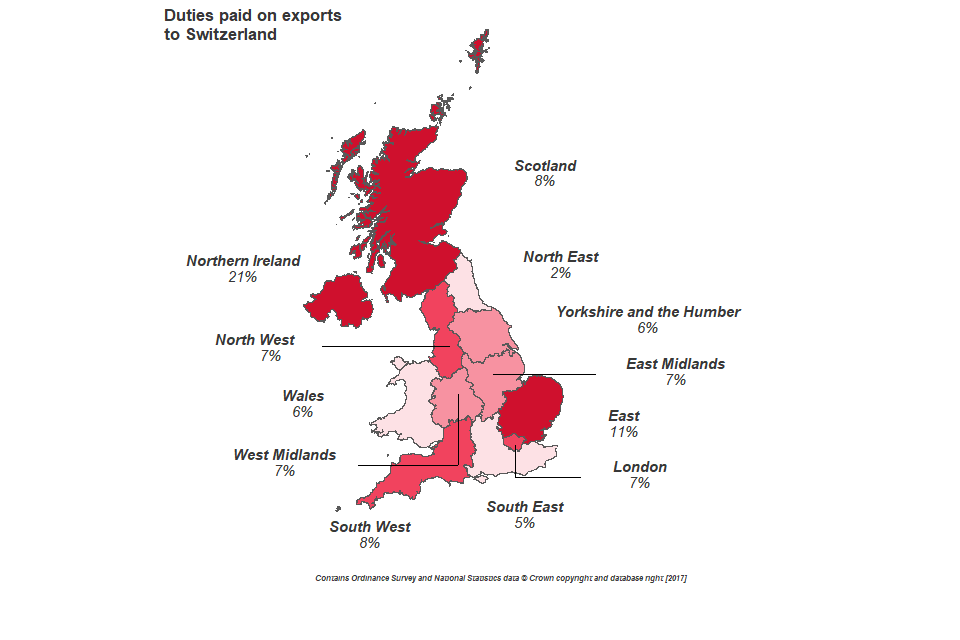

Removing the remaining tariff lines on UK goods exports to Switzerland could benefit exporters across all UK nations and regions of England, reducing the £7.4 million in duties on current UK exports. Assuming full utilisation of the agreement, the greatest savings could be present in Northern Ireland (21%) and the East (11%). Some of the largest savings are likely to be in Northern Irish, South Western and Welsh beef exports. Eliminating the remaining tariffs on UK imports could reduce the £1.1 million in duties, with the greatest savings in London (48%) and the South East (10%).

Figure 8: Share of estimated tariff reductions on UK trade with Switzerland, by UK regions and nations of England

Source: DBT calculations using tariff data from DBT, ITC Market Access Map (MacMap), and WTO TAO and annual import data averaged over 2018-2020 (Swiss import data from ITC TradeMap and UK import data from HMRC). It assumes the removal of all tariffs, and full utilisation of preferences and compliance with rules of origin requirements.

Environmental impacts

In 2019 the UK emitted 5.2 tons of CO2 per person, compared to 4.4 tons emitted per person in Switzerland. Both countries have lower emissions per person compared to the OECD average of 8.5 tons per person.[55] The UK has a comparative advantage in exporting low carbon technology products, while Switzerland possesses a relative disadvantage in the same metric.[56]

As set out in Section 2, the rationale for an enhanced agreement with Switzerland is focused on areas such as services, innovation, and digital trade. UK services trade with Switzerland is around 50% less carbon intensive than trade in industry, manufacturing or agriculture, and the carbon intensity of the UK’s services trade with Switzerland is the second lowest amongst UK trading partners.[57] The UK’s ambition is to promote trade and investment in environment and climate friendly goods and services through a modern FTA to support our respective decarbonisation goals.

[1] This is due to difficulties establishing a baseline with which to compare an enhanced FTA. The complexity of the current UK-Switzerland relationship, which is based on a series of smaller continuity EU-Switzerland agreements in addition to the SMA and MRA, makes it prohibitive to quantify the baseline in the services trade restrictiveness index (STRI) database which is used to model changes to services provisions in FTAs

[2] ONS (2023), UK total trade: all countries, non-seasonally adjusted, April 2023 edition

[3] HMRC (2022), UK trade in goods by business characteristics 2021 data tables

[4] OECD (2022), Value added by activity

[5] ONS (2023), UK total trade: all countries, non-seasonally adjusted, April 2023 edition

[6] ONS (2023), UK trade in services: service type by partner country, non-seasonally adjusted, April 2023 edition; ‘Other Business Services’ includes professional services such as management consulting, legal, accounting, and architecture, as well as numerous other miscellaneous services

[7] ONS (2023), UK total trade: all countries, non-seasonally adjusted, April 2023 edition

[8] HMRC (2023), Overseas trade by Standard International Trade Classification (SITC): custom tables; Non-monetary gold (NMG) is dominated by financial transactions, where gold is traded as a safe-haven asset, often without moving borders or even being physically present in the country reporting the trade. This makes trade in NMG volatile, but international guidance (BPM6) states non-monetary gold should be treated the same as any other commodity and is thus included in ONS export/import values to ensure comparability between countries. [9] ONS (2022), Trade in goods: country-by-commodity exports, April 2023 edition

[10]DBT calcs using tariff data from The Federal Office for Customs and Border Security (Tares) (2021), ad valorem equivalents (AVEs) from ITC Market Access Map (MacMap) for 2020 and average Swiss imports from the UK between 2018-20 from ITC TradeMap. It assumes full utilisation of tariffs and compliance with rules of origin requirements

[11] ONS (2023), UK total trade: all countries, non-seasonally adjusted, April 2023 edition

[12] ONS (2023), Trade in goods: country-by-commodity imports, April 2023 edition

[13] DBT calculations using tariff data from DBT and annual UK import data averaged over 2018-2020 from HMRC

[14] DBT calcs using tariff data from The Federal Office for Customs and Border Security (Tares) (2021), ad valorem equivalents (AVEs) from ITC Market Access Map (MacMap) for 2020 and average Swiss imports from the UK between 2018-20 from ITC TradeMap. It assumes full utilisation of tariffs and compliance with rules of origin requirements

[15] IMF (2022) World Economic Outlook October 2022; DBT (2023) Global Trade Outlook

[16] OECD (2020), Value added by activity; ONS (2023), UK total trade: all countries, non-seasonally adjusted, April 2023 edition

[17] International Labour Organization. “Education and Mismatch Indicators database (EMI)” ILOSTAT

[18] OECD (2022), Services Trade Restrictiveness Index

[19] ONS (2020), Travel trends estimates: overseas residents in the UK, 2019 and ONS (2020), Travel trends estimates: UK residents’ visits abroad, 2019. More recent data shows just 40,000 outward and 19,000 inward visits respectively for 2021, but this will have been significantly affected by COVID-19 travel restrictions

[20] WIPO (2022), Global Innovation Index 2022: What is the future of innovation-driven growth?; International Labour Organization. “Education and Mismatch Indicators database (EMI)” ILOSTAT

[21] Financial Services defined using EBBOPS 2010 Classification, 7: Financial Services and 6.1: Direct insurance, 6.2: Reinsurance, and 6.3: Auxiliary insurance services, unless specified otherwise

[22] ONS (2023), UK trade in services: service type by partner country, non-seasonally adjusted

[23] The agreed definition is based on SIC 2007 69-74, 77-78 and 82. In this document, unless stated otherwise, we will be proxying using EBOPS 10 (Other business services) excluding sub-sectors not included within PBS (10.3.2 and 10.3.4 and 10.3.5, which is partially within the scope of PBS but has been excluded here)

[24] ONS (2023), UK trade in services: service type by partner country, non-seasonally adjusted

[25] Life sciences defined as including SITC 541, 542, 774 and 872. This is a non-exhaustive definition of the life sciences sector, and the size of sector may change with different definitions

[26] HMRC (2023), Overseas trade by Standard International Trade Classification (SITC) (data from interactive tables)

[27] ONS (2020), Exports of services by country, by modes of supply: 2019 and ONS (2020), Imports of services by country, by modes of supply: 2019. Mode 1 is used as a proxy for digital delivery

[28] ONS (2023), Exports of services by country, by modes of supply: 2021 and ONS (2023), Imports of services by country, by modes of supply: 2021. Mode 1 is used as a proxy for digital delivery

[29] OECD (2021), Digital Services Trade Restrictiveness Index

[30] ‘Infrastructure and connectivity’ comprises Digital STRI measures covering restrictions related to interconnection on communication infrastructures and restrictions affecting connectivity (for example, measures affecting cross-border data flows)

[31] OECD (2022), Digital Services Trade Restrictiveness Index

[32] ONS (2022), Foreign direct investment involving UK companies: 2021

[33] FDI markets, Online database of cross border greenfield investments. As this only covers greenfield investment, it likely underestimates the scale of the UK-Switzerland investment relationship

[34] ONS (2022), Foreign direct investment involving UK companies: 2021

[35] FDI markets, Online database of cross border greenfield investments

[36] OECD FDI Restrictiveness Index, 2020. The OECD’s FDI Regulatory Restrictiveness Index (FDI Index) measures statutory restrictions on FDI across 22 sectors from 0 (open) to 1 (closed). It considers the four main types of restrictions on FDI: 1) Foreign equity limitations; 2) Discriminatory screening or approval mechanisms; 3) Restrictions on the employment of foreigners as key personnel and 4) Other operational restrictions, for example, restrictions on branching and on capital repatriation or on land ownership by foreign-owned enterprises

[37] DBT calculates using tariff data from The Federal Office for Customs and Border Security (Tares) (2021) and ad valorem equivalents (AVEs) from ITC Market Access Map (MacMap) for 2020 and average Swiss imports from the UK between 2018-20 from ITC TradeMap. It assumes full utilisation of tariffs and compliance with rules of origin requirements

[38] Ibid

[39] Ibid

[40] DBT calculations using tariff data from DBT and annual UK import data averaged over 2018-2020 from HMRC

[41] Director General for Trade of the European Commission calculations based on data from national customs administrations of importing third countries and MADB, updated 21st October 2020. 2019 is the latest publicly available

[42] DBT calculations based on data from Director General for Trade of the European Commission, updated 21st October 2020. It assumes an increase in utilisation, even if this would exceed total available preferences

[43] WIPO (2022), Global Innovation Index 2022: What is the future of innovation-driven growth?

[44] World Bank (2022). Data from 2019

[45] European Commission: The 2022 EU Industrial R&D Investment Scoreboard. The scoreboard analyses the 2500 companies that invested the largest sums in R&D globally in 2021, accounting for 86% of the world’s business-funded R&D

[46] Sectors as defined by Industry-ICB3 Sector Names

[47] World Intellectual Property Organisation (2023). Total patent grants (direct and PCT national phase entries) by applicant’s origin

[48] ONS (2023) UK trade in services: service type by partner country, non-seasonally adjusted, April 2023 edition

[49] HMRC (2022), UK trade in goods by business characteristics 2021 data tables

[50] OECD (2021) Trade in employment database 2021 edition

[51] HMRC (2022), UK trade in goods by business characteristics: 2021

[52] HMRC (2022), Regional Trade in Goods Statistics, Business Counts, Q4 2021; HMRC (2023), Regional trade data: custom tables

[53] ONS (2021), Subnational trade in services, 2020 edition. Data does not include Northern Ireland

[54] Note that these figures from HMRC are reported on a physical movement basis and are not directly comparable to trade data from ONS which are reported on a change of ownership basis. Totals presented here will differ from overall HMRC trade figures and percentages will not total 100% due to the exclusion of trade in non-monetary gold and non-response estimates and the exclusion of data not allocated to a UK country or region. Figures for 2022 are provisional and subject to change

[55] World Bank data, Metric tons of CO2 emissions per capita, 2019

[56] IMF (2020), Climate Change Dashboard: Comparative Advantage in Low Carbon Technology Products

[57] OECD TECO2 database