Risk Allocation and Pricing Approaches guidance note (HTML)

Updated 25 February 2026

1. Context

1.1 Overview

1.1.1. This note builds on chapter 8 in the Sourcing Playbook to provide more detailed guidance for contracting authorities when they are considering risk allocation in devising the commercial strategy for any contract or outsourcing initiative. Inappropriate or disproportionate risk allocation is recognised widely by government, suppliers and independent bodies, such as the National Audit Office as one of key reasons why government contracts underperform or fail.

1.1.2. This note seeks to provide government colleagues with some key information about the critical facets of risk allocation such that it is understood:

- why it is important;

- what they should be considering in regard to risk allocation in formulating commercial strategies; and

- how they might allocate various types of risk through the pricing approach chosen.

1.1.3. It is aimed at supporting practitioners in the identification of risks and development of suitable payment mechanisms and contractual terms in which to allocate such risks.

1.1.4. The contents of this guidance note apply to all Central Government Departments, their Executive Agencies and Non Departmental Public Bodies. Such bodies are referred to as “in-scope organisations”. Other contracting authorities may, at their discretion, choose to incorporate this guidance in their procurements.

1.1.5. This guidance note is expected to apply to all new procurements with an expected contract value exceeding the relevant threshold set out in the Procurement Act 2023 (“the Act”). In applying the guidance however, in-scope organisations will need to consider whether the recommended approach is appropriate to their particular procurement and to adopt a ‘Comply or Explain’ approach.

1.2 Contact

1.2.1. Feedback on and enquiries about this guidance note should be directed to markets-sourcing-suppliers@cabinetoffice.gov.uk.

2. What is Risk Allocation?

2.1 Core commercial principle

2.1.1. Allocation and management of risk is central to all commercial contracts and is one of the core commercial principles informing the approach to contracting with third parties. Each party seeks to minimise its overall risk and maximise its reward, which creates an inherent tension between contracting parties. Government can manage risk by engaging with suppliers and carefully negotiating provisions that allocate risk to the party best placed to manage it.

2.1.2. If a supplier is put in a position where they are managing an inappropriate balance of risk then the outcome is highly likely to be poor value for money (a high-risk premium will be loaded into the price), underperformance against the core contract objectives (as supplier focus increasingly shifts to cost cutting) and/or an onerous contract which could ultimately lead to its collapse.

2.2 Importance of risk allocation

2.2.1. Effectiveness and value for money of contracted services will only be achieved where risk allocation is equitable and where the party managing the risk is the one most reasonably able to do so. Contracting authorities and their advisers should be aware that the objective of risk allocation is not to transfer as much risk as possible to suppliers, but to distribute risk appropriately across the parties.

2.2.2. A possible consequence of getting risk allocation, inflation management or the payment mechanism wrong is that contracts can become onerous (loss making) for a supplier. When a contract is publicly designated by a supplier as onerous, this should prompt a root cause analysis and a conversation with the supplier about the options available to address this. There are provisions on dealing with publicly-declared onerous contracts in the Financial Reports and Audit Rights Schedule of the Model Services Contract.

2.2.3. Effective risk management is crucial to ensure successful contract delivery. Instances of contract underperformance or even failure can arise where a party has been responsible for factors beyond their control, particularly where payment is contingent on such external elements.

“If a supplier is put in a position where they are managing an inappropriate balance of risk then the outcome is highly likely to be poor value for money, underperformance against the core contract objectives, and/or an onerous contract which could ultimately lead to its collapse.”

3. When is Risk Allocation Required?

3.1 Commercial lifecycle

3.1.1. Contracting authorities should adopt a structured approach to the assessment of the risks in the contract early in the commercial lifecycle, so that all parties are clear as to the risks each is being required to bear and that they can make provision for mitigating and managing these risks in the most effective and economical manner.

3.1.2. An initial risk identification and assessment should be undertaken prior to commencement of the procurement process, either as part of completing the outline business case or the delivery model assessment (PDF, 1,196KB). The acquired information should be used to inform the contracting authority’s commercial strategy.

3.1.3. A review of risks should then be carried out periodically as the process evolves, new information emerges and circumstances change. Risk management is a continuous process and should not be treated as a ‘one-off’ exercise in the procurement/commercial lifecycle. Risks that were identified at the outset of the procurement process or contract can and do change throughout the procurement or contract for a variety of reasons, and new risks can arise which can affect the procurement or the operation of a contract. The contracting authority should give careful attention if they are considering making any contract changes in relation to risk allocation once the contract is in life. Any proposed changes should be fully impact assessed and made in line with legal advice.

3.1.4. Figure 1 sets out the key points throughout the commercial lifecycle where risk must be considered and Table 1 describes the steps in further detail. This is further described in HMT’s Orange Book: Management of Risk – Principles and Concepts.

Figure 1: Risk within the Commercial Lifecycle

Table 1: Descriptions of Risk within the Commercial Lifecycle

| Stage | Title | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Risk Identification | - Process of producing an integrated and holistic view of risks, often organised by taxonomies or categories of risk, to understand the overall risk profile. - Identification of the key risks that could impact delivery or users of the services and risks around service transfer on termination or partial termination. - Mapping the timing and impact in relation to these risks. - Risk identification is continuously carried out throughout the commercial lifecycle. |

| 2 | Risk Analysis | - Consider the likelihood of each risk arising. - Process of considering the nature and level of risk through use of a comprehensive risk register structured under a common set of risk criteria. |

| 3 | Risk Evaluation | - Involves comparing the results of the risk analysis with the nature and extent of risks that the contracting authority is willing to take to determine where and what additional action is required. |

| 4 | Risk Treatment | - Deciding whether to avoid, accept, reduce/mitigate, or transfer each risk. |

| 5 | Risk Allocation | - Defines which party will assume each risk and to what extent. - A ‘risk allocation matrix’ or ‘risk transfer matrix’ should be developed to aid the approach. |

| 6 | Risk Monitoring | - Continuous process of understanding whether and how the risk profile is changing and how well each party is managing the risks. |

| 7 | Risk Reporting | - Process of providing information to defined stakeholders to enable them to decide whether decisions are being made within their risk appetite to successfully achieve objectives. - Consideration of whether any changes are required to reassess strategy, policy and objectives. |

4. Principles of Risk Allocation

4.1 Principles

4.1.1. Risk is inherent in everything government does in order to deliver high-quality services. The Orange Book notes that public sector organisations cannot be risk averse and be successful. It is to be expected, therefore, that successful contracting will involve government taking an appropriate degree of risk as well as transferring some risks to their suppliers.

4.1.2. Suppliers may be better placed to price and manage certain risks better (and more cost effectively) than government. There are some types of risks that suppliers are well placed to manage for outsourced contracts such as day-to-day operational delivery risk. There have, however, been examples of less successful risk transfer, especially where risks that are beyond the supplier’s control are transferred from government.

The key to risk allocation is always in determining what an appropriate degree of risk looks like for both parties in order to achieve an equitable and affordable outcome for both parties that will deliver on key service objectives.

In several high-profile contracts, risk transfer has been inappropriately transferred through the pricing mechanism where suppliers were inappropriately paid on outcomes. In these scenarios, payment was linked to factors beyond their control and left the supplier exposed to the risk of not being paid for their services where the desired outcomes were not achieved.

4.1.3. One of the main drivers for risk allocation is achieving Value for Money (VfM). In general terms, transferring risk will promote VfM when the supplier is adding value in bearing and managing risk. Transferring risk appropriately to a supplier can create incentives for that supplier to deliver the contracted requirements to the scheduled timeframes, costs and to the right standards and conditions in an efficient way.

4.1.4. This principle is based on the theory that the party in the greatest position of control, in relation to a particular risk, has the best opportunity to reduce the likelihood of it materialising as well as ability to deal with the consequences of the risk if it does materialise.

4.1.5. This capability to manage the risk most effectively, and apply an efficient price, may be due to one or more of the following features:

- Greater ability to assess the risk (and associated issues or losses);

- Greater ability to negotiate with third parties and/or potential to pass through the risk to them at a reasonable or efficient price;

- Higher capacity to reduce the probability of the occurrence of a risk;

- Higher capacity to mitigate the impact should the risk materialise and to repair damage more efficiently.

4.1.6. When considering the risk allocation profile and the payment mechanism, be mindful of how this may impact the supplier’s ability to innovate over the term of the contract. Consult with the market in advance of the procurement process to assess whether the proposed approach is likely to restrict innovation and to ensure that the risk allocation and payment mechanism remain appropriate for the term of the contract and the contracting authority’s requirements.

4.1.7. When it is clear that a risk transferred to the supplier will result in a higher cost (because of risk premiums) than the expected potential loss if that risk were to be retained and managed directly by government, then the contracting authority should consider retaining that risk. However, it will only be fully possible to assess this if the probability of the risk occurring can be reasonably estimated and the consequences realistically measured. It is therefore crucial that a robust process is undertaken for achieving this.

4.1.8. Reputational risk cannot be transferred. Although certain risks may be transferred from government to a supplier, public perception is that the public does not always see it this way. In relation to public facing or public impacting services, the view is that government is responsible for the delivery of those services. If services fail or performance falls below acceptable levels, government will be held to account in the public’s eyes regardless of the contractual position on risk.

4.1.9. Understand what is being procured in detail and engage early with the relevant supply market. A key feature of poor government contracts has been a lack of early engagement with the market and clarity about what it is buying. Government cannot be in a position to understand key risks if there is a lack of market engagement and understanding, and therefore the approach to risk allocation is likely to be ill informed.

4.1.10. Placing risk with the party best able to manage it should lead to:

- Better pricing from suppliers which more accurately reflects the risk they are managing;

- Fewer performance and commercial issues during the contract term;

- A reduced likelihood that the contract fails completely, and the supplier prematurely exits the agreement or becomes insolvent;

- Greater opportunity for open and honest dialogue for mutual benefit.

4.1.11. Detail on common risks encountered in contracting, and considerations on allocating those risks can be found in Appendix I: Further Detail on Common Risks.

4.1.12. Section 12(4) of the Procurement Act 2023 requires contracting authorities to have regard to the fact that SMEs may face particular barriers to participation, and whether those barriers can be removed. In practice this could be supported by not transferring excessive risk to suppliers, particularly liability and cash flow risks (see below).

4.2 Risk allocation matrix

4.2.1. A risk allocation matrix should be developed in devising the approach to risk allocation and is indeed prescribed by the Green Book as a key component of the commercial case within any project business case.

4.2.2. The risk allocation matrix should be used to directly inform the proposed commercial model and pricing approach. During market engagement both before and during the procurement, the risk allocation matrix can be shared with potential bidders and bidders in order to seek their input. A high-level example of a risk allocation matrix is provided below.

Table 2: Example Risk Allocation Matrix

| Risk Category | Authority | Risk Allocation Supplier |

Shared |

|---|---|---|---|

| Design Risk | |||

| Delay Risk | |||

| Transition & Implementation Risk | |||

| Volume Risk | |||

| Etc. |

4.3 Allocating risk

4.3.1. Risk can be allocated in a number of ways but typically through the pricing and performance mechanisms and/or express provisions within the contract, for example, representations and warranties, insurance provisions, and indemnities.

4.3.2. The Model Services Contract guidance document for contracting authorities provides guidance on use of specific contractual provisions. For an overview of common provisions, please refer to the table below.

Table 3: Further detail on contractual provisions relating to risk

| Provision | Description |

|---|---|

| Insurance | Some of the risks identified may be covered by commercially available insurances which the supplier or contracting authority already hold, or should acquire for the purposes of the contract. Contracting authorities should use their assessment of risk to inform the insurances and limits required. Contracting authorities should recognise that in some cases, for example for the lowest and the highest value of potential claims, it may be the case that no insurance is available on the market and therefore the supplier may self-insure. In cases of self-insurance the contracting authority should satisfy itself that the supplier has sufficient resources to meet potential claims. Suppliers offering self-insurance should not be penalised for not providing a certificate of third-party insurance. Similarly, where a supplier uses a sub-contractor to deliver some of the contract, it may be the case that a Small and Medium Enterprise (SME) sub-contractor is not able to secure insurance so the supplier will assume that risk. The treatment of insurance is covered in section 1.5.3 and Annex 1 of the Model Service Contract guidance (PDF, 5.9MB) for authorities. |

| Specific liability limits | Having established what identifiable risks may materialise in the course of the contract, and arrived at a financial scale of such occurrence, limits of liability should be set for each risk, whether or not covered by insurance. The limit for each risk should be arrived at through some rationale and explicable relationship to the assessed risk level. Suggested limits on liability are set out in the standard contracts, and the standard liability position is summarised in Annex 1 to the Model Service Contract guidance (PDF, 5.9MB) as a starting point. For example, there are separate liability limits for data protection breaches and other general losses. As set out in the Sourcing Playbook, suppliers should not be asked to take on unlimited liabilities, other than the small number of incidences where limiting liabilities would not be lawful, or where a commercial cross-government policy has been agreed. A commercial cross-government policy has been agreed allowing for the following unlimited liabilities: - VAT, income tax and national insurance payable by the supplier; - Supplier employee claims against the contracting authority; - Third party (non-commercial off the shelf) intellectual property right claims against the contracting authority; - TUPE transfer liabilities; and - Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) issued fines for data protection law breaches. Paragraph 4.1 of Annex 1 to the Model Services Contract guidance for authorities (PDF, 5.9MB) provides further detail on these specific unlimited liabilities. For example, in relation to each head of insurance, professional Indemnity Insurance might be required to provide cover at 150% of contract value, but cover required for third party claims may be limited as they are of remote likelihood in the context of the contract. Contracting authorities should be proportionate when requesting insurance terms, such as being named as principal or per‑claim liability limits. Base any requests on the contract’s risks and value, and on standard practice in the relevant insurance market. These terms are often impractical for suppliers, and being named as principal may offer limited benefit to the authority. Authorities should also consider aggregate liability, including how far it extends (for example, to the Crown). Key negotiation issues related to liability, indemnity and insurance are covered in 1.5.4 and Annex 1 of the Model Services Contract guidance (PDF, 5.9MB) for authorities. |

| Performance related termination events | Escalation triggers to a termination event should be proportionate, and allow the supplier time to rectify performance levels for all but the most serious defaults. Termination triggers may include a critical performance failure; or a failure to implement an agreed rectification plan. Critical performance failures and rectification plans are detailed in Clauses 7 and 25 of the Model Services Contract. |

| Indexation | Indexation is a means of allocating inflation risk to the contracting authority. It sets out provisions to link prices to a suitable price index or indices to manage the risk of the supplier’s costs rising over time, by increasing prices in line with inflation. Further details can be found in Chapter 6: Inflation Management Mechanisms. |

| Residual liability limits | Once the main risks in the contract have been dealt with using these steps, then any residual risk, comprising lesser or undefinable areas of risk, can be considered. It may then be appropriate to establish a limit of liability for these residual risks. The aggregate liability limits established by undertaking the risk assessment exercise should be compared to the standard liability position summarised in Annex 1 to the Model Service Contract guidance (PDF, 5.9MB) as a starting point. Significant variance may be considered justification to depart from the standard but legal advice should be taken in such cases. |

5. Pricing Approaches and Payment Mechanisms

5.1 Effective payment mechanisms

5.1.1. The payment mechanism is used as a means to allocate the burden of delivery risk and incentivise the supplier to deliver to time and quality. The payment mechanism and the approach to risk allocation go hand-in-hand.

5.1.2. The aim of the payment mechanism and pricing structure is to reflect the optimum balance between risk and return in the contract. As a general principle, the approach should be to link payment to the delivery of service outputs and the performance of the service provider.

5.1.3. Where a risk is transferred to the supplier, the price paid by the contracting authority reflects this and there is no adjustment mechanism if the event does occur and impacts the supplier’s cost base. However, any decision to transfer risk may result in the supplier charging a risk premium or cause unintended behaviours.

5.1.4. Where a risk (e.g. inflation risk) is not transferred (or not wholly transferred) to the supplier, contractual mechanisms exist to adjust the price paid to the supplier by the contracting authority by adjusting the price, or elements of the price, linked to a specified index.

5.1.5. Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) should be easily measurable and objective, with suppliers only being held accountable for results they can influence. More detail on KPIs can be found in the Sourcing Playbook (PDF, 3.1MB), while guidance on the KPI-related provisions of the Act is available here: What notices are linked to this aspect of the Act?. KPI provisions can also be found in the Performance Levels Schedules of both the Model Services Contract and the Mid-Tier Contract.

5.1.6. More information on common payment mechanisms can be found in Appendix II: Further Detail on Common Payment Mechanisms.

5.2 Pricing structure

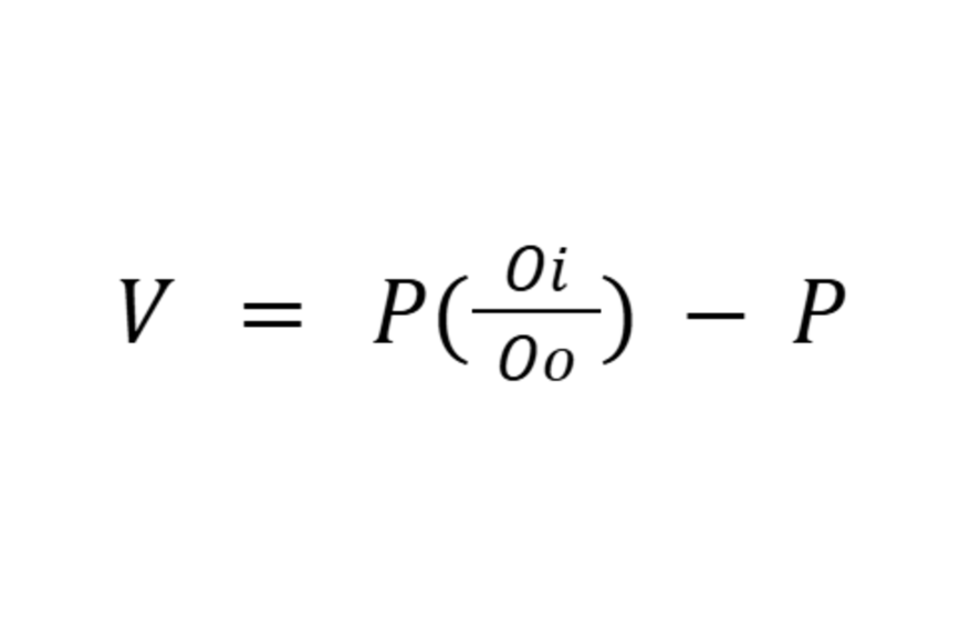

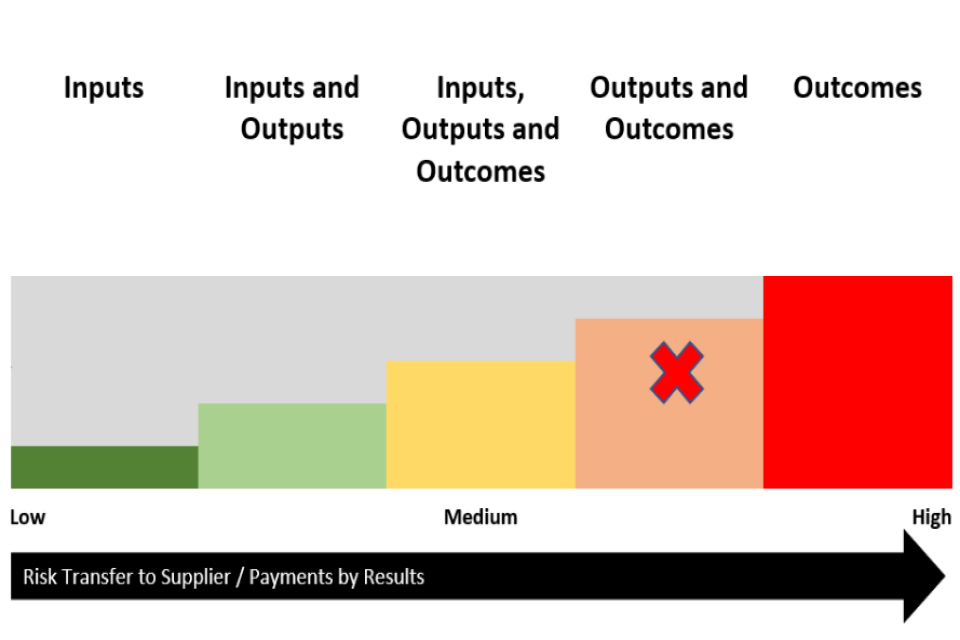

5.2.1. To determine the most appropriate pricing structure, it is necessary to understand whether the pricing applies to inputs, outputs or outcomes. There is a higher level of risk to the supplier if pricing is based on outcomes compared to inputs, this is due to payment being increasingly contingent on results. Market intelligence can aid decision making on the pricing approach[footnote 1]. Examples of market considerations include:

Policy novelty:

A new policy is unlikely to have a developed market.

Number of market participants:

Structuring the payment mechanism to reduce barriers to entry may increase the number of bidders.

Market capacity:

A market with low capacity will typically want greater assurance of cost coverage.

Delivery flexibility:

Input payment mechanisms can stifle innovation and reduce supplier flexibility.

Size of market participants:

Different sized entities will have varying risk appetites.

Cashflow implications:

High upfront investment or excessive lag from cost incursion to payment could result in sizeable cash deficits. This can cause particular issues for SMEs and Voluntary, Community and Social Enterprises (VCSEs) who may not have large cash reserves.

The point at which results become measurable:

It is more practical to pay for outcomes occurring in the short-term.

5.2.2. Payment mechanisms can also take on a hybrid approach to share risk between both parties. This approach is appropriate when both parties treating the risk results in a mutually beneficial reduction in risk.

5.2.3. Input-based payment mechanisms pay the supplier for the allowable costs incurred in delivering the contract. This approach is most appropriate where the contracting authority wishes to exercise a large degree of control over how the service is to be delivered. Input-based payment mechanisms result in the contracting authority assuming responsibility for managing all or most of the risks and should therefore not include risk premiums. However, input-based pricing reduces the ability and incentivisation for the supplier to innovate and generate efficiencies throughout the contract lifecycle which may result in poorer VfM.

5.2.4. Where the contracting authority elects to use an input-based pricing approach, it may wish to set a cap on input prices to reduce its level of risk. Any caps set need to be carefully considered alongside the risks, and caps should be set at reasonable levels to allow the supplier to recover cost increases which they cannot mitigate. It may be appropriate to only cap certain costs, such as staff salaries, whilst leaving certain costs uncapped depending on the degree to which the supplier can control each cost line.

5.2.5. The market may be best positioned to design the delivery solution. In this case, use of an output or outcome-based pricing approach may be preferable. Output-based payment mechanisms pay suppliers for meeting agreed outputs, for example pricing per unit delivered. Outcome-based pricing approaches pay the supplier for meeting agreed outcomes, for example paying per person supported into long-term employment. These pricing approaches provide the supplier with greater opportunity to innovate and allow for more operational flexibility. However, it should be expected that supplier margins increase as the supplier assumes more delivery risk.

5.2.6. If an authority is specifying an output-based pricing model and transferring delivery risk to the supplier, it should refrain from also specifying inputs, i.e. how the supplier should deliver this model. Overly descriptive specifications for output-based contracts can result in poor performance, and the supplier being held accountable for outputs/outcomes that were not truly within their control.

5.2.7. Output- and outcome-based payment mechanisms should be aligned with the contract objectives with payment directly linked to the delivery of the service and performance against KPIs.

5.3 Incentivisation and disincentivisation

5.3.1. The payment mechanism can be structured to encourage supplier behaviour, either through additional payments for meeting certain criteria, or through applying service credits for underperformance.

5.3.2. Additional payments can be linked to overperformance against priority KPIs, or for delivery to certain regions/populations. For example, a volume based contract may pay an enhanced unit price for every unit delivered above a target volume to encourage reaching stretch targets.

5.3.3. The payment mechanism can also be structured to disincentivise behaviours, e.g. through applying service credits to penalise underperformance. Any use of service credits or liquidated damages should be proportionate to the value and risk of the contract. Deductions should be capped at the contract profit level and should not include ratchet mechanisms, to prevent rapid escalation to unreasonable levels of deductions. Service credits should be considered alongside the primary payment mechanism to ensure suppliers are not penalised twice for the same underperformance. Service credit provisions can be found in the Performance Levels Schedules of the Model Services Contract, and the Mid-Tier Contract.

5.4 Key considerations when designing a payment mechanism

5.4.1. Ensure payment triggers are unambiguous:

Any payment event (whether for an input, service delivery or milestone completion) should have a sufficiently clear definition of the trigger for payment.

5.4.2. Provide sufficient explanation to bidders of proposed payment mechanism:

If the payment mechanism is not sufficiently understood by bidders, this can lead to poor incentivisation and suboptimal pricing. Detailing the rationale and providing worked examples both during market engagement and in tender and contract documents will reduce the risk of lack of understanding of how the payment mechanism works.

5.4.3. Understand the impact of the payment mechanism on cash flow:

Contracting authorities should generally seek to ensure suppliers cash flow is reasonable. This does not mean that there should be no cash flow risk to the supplier, but that it should be clearly defined and agreed from the outset. Contracting authorities should consider if the cash flow risk will disproportionately impact certain entities, such as SMEs or VCSEs.

5.4.4. Payment mechanism options should undergo thorough testing, both internally and with the market:

Scenario analysis is important to understand profitability and cash flow at multiple activity and performance levels to ensure the payment mechanism does not incentivise unintended outcomes. Testing the impact of external factors such as changes in legislation on profitability can help determine if risk transfer is excessive. The team responsible for contract management should be consulted on whether the proposal is appropriate.

5.4.5. Understand the level of risk premium:

Contracting authorities should have visibility over the level of risk priced into a bid and should consider use of ‘risk pots’ where the specific value of each risk is set out. Having visibility on each risk and the associated value should enable negotiation between the parties to ensure that the value is appropriate and proportionate. Use of ‘allowable assumptions’ (set out in the Charges Schedules of the Model Services Contract, and the Mid-Tier Contract) can reduce risk premium through introducing a formal mechanism whereby the value associated with a specific assumption is only released should the assumption prove to be inaccurate. See 1.6.1 of the Model Service Contract guidance (PDF, 5.9MB) for authorities for further guidance on use of allowable assumptions.

“The aim of the payment mechanism and pricing structure is to reflect the optimum balance between risk and return in the contract.”

6. Inflation Management Mechanisms

6.1 Determining the inflation management mechanism

6.1.1. When determining how best to manage inflation risk within the contract, an inflation management mechanism must be decided upon. Certain input-based payment mechanisms that allow for full cost recovery will manage inflation risk through the nature of their allowable charges. Other payment mechanisms may require specific clauses added into the contract to manage inflation risk appropriately.

6.1.2. When assessing how best to manage the impact of inflation in the contract, the following information is required:

- The project scope, specification of the goods or services being purchased and the project timetable;

- Details of supply chain options including the likely source country/countries and any foreign exchange impact;

- Where possible, estimates for base prices of the goods or services.

6.1.3. The three inflation management mechanisms are:

- Escalation factors;

- Indexation;

- Cost plus payment mechanisms and variants.

6.1.4. Once the payment mechanism has been determined, a suitable inflation management mechanism should be chosen. The available inflation management mechanisms for each pricing approach is shown in Table 4:

Table 4: Inflation management mechanisms and pricing approaches

| Inflation management mechanism | Pricing approach |

|---|---|

| Escalation Factors | Firm pricing Time and materials Volume based pricing Payment by results |

| Indexation | Fixed pricing Time and materials Volume based pricing Payment by results |

| Cost plus | Cost plus Guaranteed Maximum Price above Target Cost |

6.1.5. Escalation factors utilise a base price at a particular point in time which are uplifted in line with a set escalation factor (which may be 0%) agreed at the start of the contract. They are not subject to indexation. Use of escalation factors is a reasonable option only if the supplier is better placed to manage inflation risk as prices are relatively stable or predictable. Even then, contracts should only use escalation factors in the short term because it is easier to predict prices in the near future. Use of escalation factors transfers all inflation risk to the supplier.

6.1.6. Using indexation means that prices are subject to change in line with a chosen price index. Prices are set a base price at a particular point in time (normally the date of the contract) and incorporate price changes in line with a price index or indices at a set point in time (see Appendix III for information on how to choose the most appropriate indexation and section 6.6 to see requirements for fixed pricing in contracts). Contracting authorities can apply indices to specific cost lines within their pricing schedule to reflect price movements within different industries or countries. For contracts with considerable inflation uncertainty, using indexation is advisable. Indexation allocates inflation risk to the contracting authority.

6.1.7. If a cost plus pricing approach has been adopted, the supplier’s input costs are passed through to the contracting authority, consequently as prices change over time, so will the charges to the contracting authority. Therefore no further inflation management mechanisms are required. Use of cost plus to manage inflation, results in suppliers not being incentivised to keep up with industry standard productivity or efficiency gains. Cost plus pricing is not recommended if inflation is the sole risk consideration. Other risk/market considerations may mean cost plus is appropriate (see Chapter 5 for considerations when selecting the appropriate pricing approach). Cost plus pricing allocates inflation risk to the contracting authority.

6.1.8. Annual uplifts are similar to escalation factors, however, the level of uplift is agreed annually based on current market conditions. They are often used when prices are considered too volatile to agree at the start of the contract, but if this is the case, indexation is a better inflation management mechanism as it automatically aligns with market conditions and saves resources on annual negotiations which should be based on the most appropriate indices in any case.

6.1.9. It may represent VfM to use a combination of inflation management mechanisms, such as for cost lines with different cost drivers. The contracting authority should consider the supplier’s ability to manage contract costs, and only consider applying inflation management mechanisms to costs that are outside the control of the supplier.

6.2 Requirements for applying indexation

6.2.1. Price indices must be taken from an official government source, which in the UK is the Office for National Statistics (ONS), to ensure that price indices are independently compiled based on international best practices. Only published price index data may be used to calculate payments linked to indices, to ensure that actual values are used rather than forecasts.

6.2.2. The most appropriate index will depend on the specific cost drivers of a contract. Developing a Should Cost Model can help to identify costs and where indexation may be required.

6.2.3. Output price indices include all production/delivery costs, an element of productivity gains, and profit. This incentivises the supplier to make productivity gains at least in line with those made by other companies in their industry, whereas input price indices only reflect the input costs of the production process so do not incentivise efficiency. Input indices do not include indirect labour costs such as employer national insurance contributions. For most government contracts, output indices are more suitable, except in highly exceptional circumstances where input indices may be required. This is the case even for single source contracts which are best dealt with by setting appropriate base prices and using industry specific output price indices to adjust for inflation. Increasing inflation above the industry average could lead to spiralling labour inflation (as annual pay negotiations are commonly linked to industry averages) and wage price spirals.

6.2.4. The base period is an average of the data available for the twelve months/four quarters before the date of the contract and the price uplift period is an average of the twelve months/four quarters before the price uplift date. Only available index values that fall entirely within the twelve-month period should be used (for example, if using a quarterly index and the price uplift period runs from 01 June 2024 to 31 May 2025, only Q3 2024, Q4 2024 and Q1 2025 would fall entirely within the period).

6.2.5. All costs expected to be incurred prior to the first price uplift period (which might include set-up costs such as the acquisition of machinery and equipment, and the forward purchase of materials) must be priced using a method that is not subject to indexation.

6.2.6. There is no need to incorporate an inflation risk premium because the price indices track market prices. By using indexation, the contracting authority takes on the inflation risk and the supplier does not hold any inflation risk, so it would be inappropriate to provide additional inflation risk cover.

6.2.7. Caps and collars (restrictions on the maximum or minimum level of price uplift) distort the ability of indexation to reflect actual inflation. If suppliers cannot be guaranteed an appropriate price uplift, they may want to include an inflation risk premium, which may reduce VfM.

6.2.8. If an index used in an extant contract pauses publication, use the original index if at least six months of index values are available and if not, move to the closest replacement index as advised by the relevant statistical authority until sufficient index values are published to resume calculations.

6.2.9. If an index used in an extant contract ceases publication, the parties must negotiate a replacement index.

6.2.10. If an index used in an extant contract is rebased, use the rebased series if the index values for the base period and price uplift period are both available. If not, calculate a link factor by dividing the value of the index under new conditions by the value of the index under old conditions for the last period for which the index under old conditions is available. Index values under old conditions are then multiplied by this link factor to rebase the historic series, thus calculating the base period values under new conditions.

6.2.11. Open Book Contract Management (OBCM) can complement the operation of a contractual index. It is a structured process for the sharing and management of charges and costs and operational and performance data between the supplier and the contracting authority. OBCM provisions can be found in the Financial Reports and Audit Rights Schedule of the Model Services Contract, and in the Award Form and Core Terms of the Mid-Tier Contract (where it is referred to as ‘Financial Transparency Objectives’).

For specific inflation queries for contracts over £5 million, contact Analysis-Econ-PI-Contracts@mod.gov.uk.

7. Appendix I: Further Detail on Common Risks

This section of the document provides detail on some of the common risk areas and seeks to set out a description of the risk and some factors for the contracting authority to consider when devising its approach to risk allocation.

Data Accuracy Risk

Description of Risk

Risk that inaccurate or incomplete data is provided to bidders during the procurement exercise leading to inaccurate pricing or solution.

Ensuring the accuracy of the data provided is essential for both the contracting authority and bidders, as reliable and accurate data supports fair competition, accurate pricing, and effective contract delivery.

Risk to the Supplier

- Suppliers use data provided by departments at bid stage to inform the pricing of their bid/the contract. If data provided was incomplete/inaccurate then there is a risk that the contract price bid is insufficient to the supplier in contract life, e.g. the supplier may incur higher costs in running the service than forecast.

- The contract price may not allow the supplier sufficient profit or even to cover their costs, making the contract onerous.

Risk to the Contracting Authority

Where data is insufficient, there are several key risks to the department:

- Bidders may request extensions to key submission deadlines on the basis of deficient data, causing timing risks.

- Receiving heavily caveated bids (risking non-compliance) or a no-bid decision meaning there may not then be a viable competitive procurement, reducing the number of potential solutions available.

- Bidders may account for inaccurate data by including a ‘risk premium’ in their bid price to mitigate their risk that the incurred costs will be greater than the forecast costs. The department will pay this even if this is not the case.

- Bidders may simply get the price ‘wrong’ and bid a greater price than it would have, had it been able to rely on better data.

- With a high degree of competitive tension, bidders may drop risk premiums in order to secure the business, however these risk suppliers making insufficient profit or making a loss. The supplier may seek to reduce cost by reducing performance, which may lead to higher contract administration burden, or bidders may decide to seek to partially or fully terminate the service.

Risk Considerations

- Contracting authorities should invest sufficient effort to obtain a comprehensive and detailed set of bid data and share all appropriate data with bidders. For example, through provision of a data room, enabling bidders to undertake due diligence, query and ask for additional data. The nature of this will depend on the type, scale and route of procurement.

- Where bidders have been able to undertake sufficient due diligence and satisfied themselves as to the status of the data, then contracting authorities may ask the supplier to take the risk on data accuracy.

- In certain cases, the contracting authority may elect to warrant that the data is complete and accurate. While the contracting authority effectively takes the risk of data accuracy, with bidders given certain rights if the warranty is breached, they should reasonably expect bidders to demonstrate that there is no risk premium associated with data inaccuracy within their bid. Contracting authorities considering warranties should seek legal advice.

- Contracting authorities should not hold incoming suppliers responsible for errors in data, excluding forecasts. Contractual mechanisms should cover erroneous data, subject to restrictions relating to material variations under public procurement law. Any adjustments should take place no more than a year after service commencement.

- Contracts may include a ‘true up’ mechanism and/or use of allowable assumptions which permit suppliers to verify aspects of a contract after it has been signed. This is to reflect the practical reality that it is not always possible to conduct full due diligence prior to signing nor always appropriate for this risk to sit fully with the supplier. Where a supplier can demonstrate that an assumption is inaccurate, and where both parties agree there is a cost impact, the supplier can propose a change to the contract charges, subject to this not exceeding a specified cap. Allowable assumptions are set out in the Charges Schedules of the Model Services Contract, and the Mid-Tier Contract.

- Where service provision is already outsourced, the contracting authority is dependent on incumbent suppliers to provide relevant data. An obligation to provide and maintain a ‘virtual library’ throughout the contract should be included in contracts. Virtual library provisions can be found in the Exit Management Schedules of the Model Services Contract and the Mid-Tier Contract. The supplier should be obligated to provide information that is accurate, complete and up-to-date, meaning at the point of re-procurement there should be greater confidence in the data.

Inflation Risk

Description of Risk

Risk that the cost of supplier’s inputs will rise over time due to inflation.

For longer term contracts or in markets with volatile prices, failure to consider the impact of rising input prices may result in: bids including a large inflation risk premium which may not represent VfM should the risk not materialise; contract profit margins reducing; contracts becoming onerous.

Risk to the Supplier

- Where prices are firm, the submitted bid price could be, after actual inflation is considered, incorrect and insufficient to allow for recovery of costs after actual inflation is considered.

- Where inappropriate indices are used, the uplift could be misaligned with market prices and insufficient to allow for recovery of costs.

- Lack of appropriate mechanism, use of inappropriate indices, or use of caps or collars on indexation could lead to risk pricing rendering the bid uncompetitive.

- Reputational damage could be caused if margins are deemed too high after applying a mechanism which leads to over-recovery of costs.

Risk to the Contracting Authority

- Industry may choose not to bid if the mechanisms and/or indices are not appropriate.

- Industry may include risk pricing which will increase the overall cost of the bid and erode the value to the taxpayer.

- Supplier’s performance may decrease if the treatment of indexation leads to under-recovery of costs. If the supplier cannot bear losses arising from an inappropriate mechanism it may exit the market or become insolvent, possibly reducing the level of competition in the market and reducing future VfM in bids.

- Reputational damage could be caused if margins for the supplier are deemed too high after applying a mechanism which leads to over-recovery of costs.

Risk Considerations

- Suppliers take this risk in a ‘firm price’ approach, although may include a risk premium to compensate for taking risk. Supplier’s performance may decrease or the supplier may experience financial distress if the treatment of inflation leads to under-recovery of costs.

- Contracting authorities should assure themselves that any index/indices within the contract are appropriate and they understand the risks of specifying inappropriate indices. Reputational damage could be caused if margins for the supplier are deemed too high after applying a mechanism which leads to over-recovery of costs.

- When determining cost lines where indexation will apply, consider the supplier’s ability to manage different cost types, e.g. utilities cost, wage levels.

Performance Risk

Description of Risk

Risk that the services will not be delivered to the requisite performance/availability levels.

Robust KPIs are required to adequately assess supplier performance levels. More detail on KPIs can be found in the Sourcing Playbook (PDF, 3.1MB), while guidance on the KPI-related provisions of the Act is available here: What notices are linked to this aspect of the Act?. KPI provisions can also be found in the Performance Levels Schedules of both the Model Services Contract and the Mid-Tier Contract.

Risk to the Supplier

- Disproportionate payment mechanisms that make excessive deductions in relation to the actual level of failure, adversely impact contract profitability that could ultimately result in an onerous contractor, in extreme scenarios, put a supplier at risk of insolvency.

- Wrong metrics assessed which are not linked to desired deliverables thus causing a distraction to the delivery of the contract outcomes.

- Overly complex performance measurement, increasing the likelihood of error in reporting and resources required to provide assurance of performance to the contracting authority.

- Reputational risks of failure of KPIs, particularly where KPI failures are published in a contract performance notice; or where poor KPI performance could risk exclusion from future procurements.

Risk to the Contracting Authority

- Disproportionate payment mechanisms that make excessive deductions in relation to the actual level of failure, could cause suppliers to withdraw from the contract/market or, in extreme scenarios, put a supplier at risk of insolvency.

- Incorrect focus of the mechanism which does not correctly incentivise the supplier to deliver, i.e. the supplier is not penalised for significant failure and the contracting authority has paid for a service it has not received or not received to the required standard.

- Wrong metrics assessed which are not linked to desired deliverables thus causing a distraction to the delivery of the contract outcomes.

- Complexity in measurement and increase in risk of error and increase in cost of contract overall as more resources are required to measure and record performance.

- Reputational risks of failure of KPIs.

Risk Considerations

- The Supplier must take this risk. Risk can be allocated through the payment mechanism through which the supplier is incentivised to deliver through placing profit at risk.

- Contracting authorities also need to be clear on any dependencies upon them in order to enable the supplier to meet performance measures.

- The number of specific measures to be kept to a minimum; too many measures impacts on the risk profile of the overall contract and becomes too unwieldy to measure and manage which has a cost implication for the contracting authority in terms of additional resource required on the contract.

- Measures must be simple to understand (with defined joint understanding), simple to measure and sensibly measurable; all measurements must be objective and not based on subjective judgement. There should be minimised manual intervention to minimise margin for error.

- Measures should be achievable where a ‘good’ level of service is delivered. ‘Good’ in this context should be considered in the same way as benchmarking provisions and should be consistent with industry norms.

- Contracting authorities may consider a ‘bedding in period’ during which particular KPIs do not apply. Contracting authorities must comply with the relevant KPI-related provisions of the Act. Guidance on KPIs is available here: Guidance: Key Performance Indicators.

- Penalties in the form of liquidated damages or service credits should be proportionate to the value and risk of the service. Deductions should be capped at contract profit, not linked to revenue and should not include ratchet mechanisms which can quickly escalate to unreasonable levels of deductions. Liquidated damages should be a genuine pre-estimate of loss and the customer’s sole and exclusive remedy for service failure.

- Relief should apply when failure occurs as a result of a failure of a dependency.

- Escalation triggers to a termination event should be proportionate to contract risk and value, with early intervention encouraged to prevent escalation (see Clause 27 of the Model Service Contract regarding Intervention Events). Termination Trigger Events may include critical performance failure or failure to implement an agreed rectification plan for remediable defaults.

Volume/Demand Risk

Description of Risk

Risk that the actual usage of the service varies from the levels forecast.

Volumes may change over time for a variety of reasons, either slowly (e.g. due to changing preferences of the service user), or rapidly (e.g. due to policy changes).

Additionally, demand may vary predictably over a period, such as seasonally.

Risk to the Supplier

- The risks to the supplier will depend on the extent of the volume/demand movement and/or how far in advance the movement can be predicted. The impact of the risk is dependent on the pricing mechanism adopted.

- Suppliers develop their solutions, including entering into sub-contracts, based on the volumes provided in tender documents. In mature markets suppliers may have an appreciation that generally volumes can, and historically have, been variable. Without perfect foresight, or a set of consistent assumptions, provided by the department, suppliers are unable to assess the probability and extent of changes in volume.

- In entering into sub-contracts, suppliers will provide the data contained in tender documents to their supply-chain partners. Suppliers have a choice when working with their supply chain, they can either:

- Flow down the risk of volume movement to their supply chain partners;

- Hold the risk themselves rather than flow it down; or

- Adopt a hybrid approach where part of the risk is transferred, and part is retained.

Risk to the Contracting Authority

- Where an inappropriate payment mechanism is used, the contracting authority will not achieve value for money. For example, pricing variable services on a fixed price basis will result in the contracting authority paying for under-utilised capacity, if volumes subsequently decrease.

- Service quality can be impacted by volume movements which were not anticipated by the supplier in designing the solution. Where volume fluctuations can be predicted, suppliers will build an appropriate amount of flexibility/spare capacity into their solutions.

Risk Considerations

- Risk for volume forecasting should sit with the party who is best placed to manage the volume forecasting process.

- Where demand data is unreliable, contracting authorities may consider guaranteeing a minimum volume to suppliers or paying a fixed service fee, in order to allocate risk more equitably.

- Data is often summarised to bidders in the form of averages which can mask peaks and troughs of demand. For example, does the average number of calls received per day mask a peak between 08:00 and 08:30? Bidders having to rely on average demand can impact price or service quality as solutions will often be over or under-resourced.

Risk of Change in Law – General

Description of Risk

Risk that a general change in law affects the supplier’s ability to deliver any aspect of the contract to time, budget and performance.

A general change in law is one where the change is of a general legislative nature (including taxation or duties of any sort affecting the supplier) or which affects or relates to a ‘comparable supply’ or other contracts for the supply of similar services with other customers, i.e. it isn’t unique to the contract with the contracting authority.

Risk to the Supplier

- Some changes in legislation or mandatory industry standards which fall within the definition of a General Change in Law may have a significant impact on the cost of delivering the services either as:

- A one-off cost of making a change (e.g. an upgrade to IT security systems); or

- Recurrent costs (e.g. labour costs either as a function of labour rates, or additional time taken to perform tasks due to a new standard).

Where the pricing approach is not based on inputs, a General Change in Law may render the contract onerous, particularly for longer-term contracts.

- These changes may not be predictable at the point of forming the contract.

- It is not the change in law which necessarily creates risk for a supplier, but the way in which other contractual mechanisms either compound or mitigate the impact of the change.

- The risk impacts not only the prime supplier but their SME sub-suppliers. A supplier could seek to mitigate its own exposure by engaging in contracts with its supply chain which mirror the terms of the contract it has with government. Many suppliers won’t or can’t adopt this approach as to do so would cause significant harm to SMEs in its supply chain.

Risk to the Contracting Authority

- General change in law risk is mostly allocated to the supplier, the standard contracts state that suppliers bear the risk of change and are not entitled to request an increase in charges. Suppliers may seek to mitigate the risk through making a provision for possible impacts of changes in law within their price. However, due to the nature of competitive tendering it is unlikely that a supplier that seeks to fully pass on the cost of treating the risk will be successful.

- The risk to the department occurs prior to, and during the procurement process. When assessing whether to submit a bid, suppliers will assess risks that may prevent it from achieving their strategic and financial objectives. Where the balance of risk and reward is too great, prospective suppliers will not bid or will withdraw. This risk will be particularly great for SMEs since they may lack the financial resilience of larger suppliers for whom it is still a material consideration when electing whether to bid and at what price.

Risk Considerations

- The pricing approach used will determine the level of risk transferred. For example, a fixed pricing approach, linked to the most appropriate price index, would result in the contracting authority bearing the risk of changes to minimum wage laws, as the supplier recovers all costs. When contract pricing is subject to indexation, using output indices reduces the level of risk transferred to the supplier. Prices will be adjusted based on increases in the cost of goods and services, which generally reflect the total costs to the employer, including indirect costs that may not be captured by input-based indices.

Risk of Change in Law – Specific

Description of Risk

Risk that a specific change in law affects the supplier’s ability to deliver any aspect of the contract to requirement time, budget and performance.

A specific change in law is one that relates specifically to the business of the contracting authority and which would not affect a ‘comparable supply’.

Risk to the Supplier

- If the risk was reasonably foreseeable at the time of entering into the contract, the supplier takes this risk as it should have been included in the bid price. Therefore the risk to the supplier is if the change is deemed to have been foreseeable, the contractual profit could be reduced or parts of the contract may become undeliverable.

Risk to the Contracting Authority

- If the specific change in law was not foreseeable at the time of entering into the contract, the supplier may be entitled to an increase in charges or relief of obligations provided it has sought to mitigate the effect. The Model Services Contract and the Mid-Tier Contract Core Terms contain relevant provisions.

Risk Considerations

- To successfully manage risk in the contract, the following provisions must be designed to work in a complimentary manner: Change in Law provisions; Open Book Contract Management rights and Benchmarking; Indexation clauses; and Contract duration.

Specification Risk

Description of Risk

Risk that the contract does not fulfil the required purpose due to poor specification drafting.

Risk to the Supplier

- Reputational damage caused by delivering a solution that does not meet expectations, due to requirements being unclear.

- Costs of entering into disputes to obtain required clarity.

- Costs of redesigning solutions or in extreme cases developing new capabilities.

- Scalability issues can be experienced where volume data is inaccurate (see volume risk).

Risk to the Contracting Authority

-

Reputational damage caused by poor management of public money and insufficient direction and oversight.

- Services which fail to deliver intended results.

- Cost uncertainty relating to the solution and/or disputes.

- Requirement to pause the procurement resulting in programme delays whilst a less ambiguous specification is drafted.

- Procurement challenge if the specification is significantly amended during the procurement process such that other suppliers may have been interested in bidding, or if the contract is materially amended during its term to fix issues relating to an ambiguous specification (provided the modification is permissible under the Act).

Risk Considerations

- The contracting authority, as the buyer, is responsible for ensuring its requirements are clearly and unambiguously communicated.

- Engaging in pre-procurement market engagement will allow the contracting authority to test the specification with prospective bidders to determine whether the specification will result in solutions that deliver the contracting authority’s objectives.

- If there is a genuine lack of clarity of the requirements at the point of contracting, this should be reflected in the choice of payment mechanism. Use of a payment mechanism where the supplier is guaranteed cost recovery, such as a cost plus mechanism will mitigate the risk for the supplier.

8. Appendix II: Further Detail on Common Pricing Approaches

This section of the document provides detail on some common pricing approaches covering a range of risk allocation scenarios and applications.

Fixed Price

A requirement is specified using an output specification, with appropriate performance measures and incentives in place. Base prices for the goods or services are agreed at the outset and are uplifted in line with an appropriate price index or indices. The supplier takes on the performance risk of delivering the services to the agreed standards within the fixed price. This allows the contracting authority to achieve price certainty for a defined scope and standard of service, and the base price will not vary unless the contracting authority wishes to amend the scope or standard of service.

The key component of fixed price has to be “fixed scope”. Floating or variable scope is not suitable for fixed pricing.

Fixed pricing is not suitable where it is impossible to estimate base prices (e.g. where the output specification is unknown, such as an innovative new design not previously costed). In this case, cost plus pricing approaches may be the only option. In fixed pricing mechanisms, contracting authorities should specify, or request and agree, the elements of the contract that will be subject to indexation during the tendering exercise to ensure transparency from the outset.

Common Application

Fixed price approaches are most suited to medium to long-term agreements whereby the variation of prices as a result of macro-economic factors cannot reasonably be predicted. The price for an initial period should be firm. Thereafter the prices may be adjusted by a direct link to published indices. The output specification should be well-defined and easily understood. If the quantum (volume/frequency) is unknown then volume based pricing (see later section) may be appropriate.

Benefits

- Relative price certainty for the supplier: notwithstanding indexation risks, the supplier can make a reasonable estimate of the likely revenue it will generate and given that prices are inflated in line with the most appropriate indexation, this better protects profit margins from higher than anticipated inflation.

- Relative price certainty for the contracting authority: since prices will move only through contract variation or through indexation, financial planning is more straightforward.

- Encourages supplier efficiency: on the basis that the price to the contracting authority can only be varied due to specific scope or quantum changes, the supplier is encouraged to maintain efficiency to keep costs at least in line with forecast. If an output index is used to manage inflation risk, the supplier is further incentivised to innovate at least in line with industry average.

- Process certainty: there is an agreed approach to inflation management from the outset, this is easy to track and agree.

- For services defined as fixed price services in the contract, the financial and operational risk for delivery of the defined services and standards is transferred from the client to the supplier.

Risk Considerations

- The key risk considerations in relation to fixed price payment mechanisms relate to clarity of the specification and the appropriateness of the index used.

- The clarity of the specification is critical in underpinning price risk transfer. If the specification is ambiguous, or not comprehensive, it provides the supplier with ‘wriggle room’ once appointed to argue that certain aspects of the service were not included in the fixed price.

- The most appropriate index or indices must be used which reflects the main cost lines of the contact. A contract for a UK supplier to provide both office furniture and facilities management, a suitable UK Producer Price Index for furniture and a UK Services Producer Price Index for facilities management services. If an inappropriate index is used then the level of risk transfer to the supplier may become disproportionate.

Firm Price

Firm pricing is similar to fixed pricing, except base prices will not be subject to indexation. An escalation factor may be chosen to increase prices by a predetermined amount (e.g. 2% per year), which should be agreed during the tender process.

The key component of firm price has to be “firm scope”. Floating or variable scope is not suitable for firm pricing.

Firm pricing works best where prices are stable or predictable, thus not incurring a high risk premium. Firm pricing may be appropriate for short term contracts (generally considered to be up to three years), longer firm priced contracts attract an associated risk premium eroding VfM.

Common Application

Firm priced models are generally most suitable for short-term agreements. For contracts of longer length and/or with high inflation uncertainty, fixed pricing is considered commercial best practice as this approach will flex with market prices to suit any economic climate.

Benefits

- Price certainty for the contracting authority: the contracting authority has complete budget certainty for the duration of the term of service provision.

- Encourages supplier efficiency: the supplier is encouraged to maintain and/or create efficiency within the contract to maximise profitability against a predetermined revenue stream.

Risk Considerations

- The clarity of the specification is critical in underpinning price risk transfer. If the specification is ambiguous, or is not comprehensive, then it provides the supplier with ‘wriggle room’ once appointed to argue that certain aspects of the service were not included in the firm price.

- Divergent price and cost relationship: If used for short-term agreements cost, within a set scope, can be reasonably predictable. The more ambiguous the scope or the longer the contract period, the greater the uncertainty. The market, acting responsibly will respond to the unknowns by pricing for risk.

- Value for money: The pricing of risk is subjective and prone to error. Risk can be over-priced as easily as it is under-priced. Whilst firm pricing mechanisms transfer all inflation risk to the supplier, they also transfer any future inflation and efficiency benefits reducing the potential VfM for an authority.

Cost Plus

A cost plus mechanism is one where the payments to the supplier are calculated based on the cost of delivering the services, plus an extra amount to allow for profit (the profit paid is often dependent on the percentage tendered). Costs are calculated by reference to directly incurred supplier costs (often subject to tests to determine allowable and disallowable costs).

Cost plus requires transparency over the supplier’s actual, direct costs and allocation of overheads plus an agreed margin. It should be noted that the financial management burden for cost plus contracts may be significant so as to ensure that only allowable costs are recovered and that cost levels claimed are appropriate.

Common Application

Cost plus is particularly suited to novel or first generation contracts. The mechanism allows for reasonable costs (of hours spent and materials purchased) plus a fixed fee (either monetary value or percentage) to be paid to the supplier.

In certain scenarios, or pilots, where neither party can reasonably predict how the service requirements, and therefore cost, may evolve, the cost plus approach can work well. Since the service benefit can be offset by cost challenges, it may be appropriate to scale the pilot appropriately to constrain the impact of cost uncertainty.

Milestones should be used to track operational delivery against payments made. Over time, elements of a contract can be migrated to different pricing mechanisms when requirements and delivery challenges are better understood.

Benefits

- Price and cost relationship: since these arrangements are necessarily open book, the contracting authority has full visibility of costs. The price then moves proportionally to cost.

- Reasonableness for supplier in unknown environment: where the specification is unclear, using cost plus, although it does not provide certainty, does introduce a level of reasonableness, i.e. based on actuals, subject to open book, capped profit levels. The quality of materials is pre-determined and services can be flexed throughout the term of the agreement without either party taking an unreasonable, and unforeseen, level of risk.

- Removes service pressures such that the security of delivery is more assured: since suppliers are paid against actual costs, the risk of service deterioration is reduced should costs be higher than anticipated.

Risk Considerations

- Price uncertainty for the contracting authority: contracting authorities may enjoy the flexibility that cost plus arrangements provide. The ultimate budget holders for the contracting authority can experience difficulties in forecasting and maintaining appropriate budgetary control. It is very difficult to gain complete certainty on total outturn spend, although the relationship between costs and margin should be fully understood. However, as above, this does give suppliers greater flexibility to perform operationally; they will be paid for work undertaken without the restriction of a ‘cap’ on what is payable.

- Stifled innovation and reduced incentive for efficiencies: since payment to the supplier is based on actual spend, there can be little motivation to introduce cost saving innovation or other efficiencies.

Volume Based Payments

A volume based mechanism flexes the amount paid to the supplier according to how much the service is used. This is typically on a price per unit basis but can be combined with a fixed element (service fee) to cover certain fixed costs.

Common Application

Volume-based pricing is appropriate in instances where there is:

- A defined schedule of rates.

- Variable volume/demand.

- The rates paid may be fixed, firm or cost plus.

- Volume bands may exist recognising economies of scale/stepped price increments.

Benefits

Volume risk distribution for the contracting authority and supplier: the contracting authority pays for the volume of services actually consumed and the supplier has the potential for cost efficiencies by aligning their resources more effectively with demand.

Risk Considerations

- Value for money: where volumes are unknown, or uncertain, a supplier may take a risk-averse view and provide a unit cost appropriate to a low volume of activity (i.e. no recognition for economies of scale).

- Volume assurance: supporting evidence for invoices issued to the contracting authority can require significant supporting data to be consolidated from a variety of sources and presented in a range of formats which can be very time-consuming and expensive.

- Lack of total price/cost/profit certainty for the contracting authority and supplier: both contracting authorities and suppliers require a level of certainty regarding the total value of agreements to ensure that budget holders and the market can make investment decisions. Estimates can of course be made based on historic volume data taking into account trends but accuracy will vary.

- Recovery of fixed supplier costs: mechanisms need to recognise that fixed or semi-variable costs may have been incurred during mobilisation, or are incurred routinely throughout the contract life, and that significant changes in volume require adjustment to unit rates, to allow for total absorption of fixed or semi-variable costs.

Payment by Results (PbR)

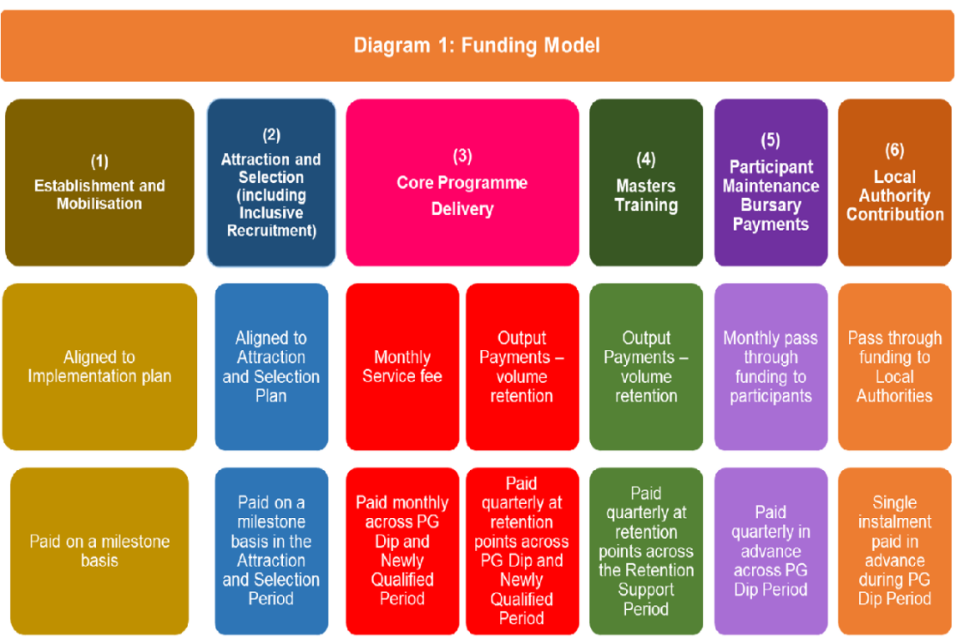

An outcome-based payment mechanism: payment by results is most commonly applied when the focus of outcomes is solely on the results achieved by the supplier.

Payment is dependent, wholly or partly, on the supplier achieving specified outcomes.

Suppliers should be given broad scope to determine the intervention required to achieve the outcome.

Benefits

- Promotes focus in terms of outcome delivery: this mechanism encourages focus on the delivery of results which should be compatible with the contracting authority’s objectives (unless this focus becomes misdirected, see below).

- This mechanism can be innovation-generative when structured correctly because suppliers are very well incentivised to deliver.

Risk Considerations

- Unintended focus of service provision: although the overall focus of service is on delivery of results, the emphasis may not be as intended. If payment is made based on results, suppliers will focus their attention on outcomes which are more likely to result in payment which may not be aligned to the intention of the contracting authority.

- High risk transfer to supplier: payment by results transfers a significant level of risk to suppliers, this may result in high risk premiums. Taking a blended approach by paying a fixed percentage of the contract value to the supplier irrespective of outcome achievements can reduce the risk transferred.

- Burden of proof on actual achievement of results: the demonstration of actual results can be difficult to prove, subject to subjective opinion and hard to document. There can be difficulty in establishing direct correlation between service quality/outputs and ‘measurement of results’.

- Cash management issues: the requirement to demonstrate results before payment is made can introduce significant cash flow issues for suppliers and could introduce additional cost of capital charges to contracting authorities. This is likely to have a greater impact on SMEs and VCSEs. Paying a portion of the total contract fixed service fee monthly throughout the contract term can mitigate this risk. The contracting authority may also wish to consider paying for mobilisation costs on an input basis (e.g. cost plus) where there are high initial fixed costs and there is a lag in measuring outcomes.

Guaranteed Maximum Price with Target Cost (GMPTC)

Under this mechanism, bidders bid a target cost for delivery of milestones or services and a margin. The target cost and the margin are together referred to as the target price. A guaranteed maximum price is set which is a specified percentage above the target price or target cost (10% above target price in the model services contract).

Where the supplier’s actual costs are less than its target cost, the savings made are shared with the contracting authority and the effect is an increase in margin achieved by the supplier. Where actual costs are greater than the target cost, the difference between the actual costs and the target cost is shared equally, provided that the most the contracting authority will pay is the guaranteed maximum price. This has the effect of reducing the margin achieved by the supplier.

Common Application

This model can be applied when outputs are known but delivery methods are not firm/defined.

Related models are also used where it is believed that changes to ways of working, or output requirements, will deliver significant efficiencies but the service quality risk attached to a wholesale movement to a new way of working is considered too great by the contracting authority.

Benefits

- Transparency of cost: open book accounting is necessitated through the application of the mechanism thus providing transparency of costs. Open book provisions should be as simple as is reasonably possible to achieve the required transparency objectives. The ability to fix an overhead percentage during the bid which carries into the open book process may simplify reporting.

- Sharing of cost increases both risk and savings benefit: the shared impact of both cost increases and savings benefit can help to form a true partnering relationship as both parties are incentivised to identify cost savings. The mark-up applied by the supplier can be treated as a percentage or as a fixed cash value. The fixed cash value approach reduces the risk of margin dilution for the supplier in the event that costs decrease but would dilute margin returns where the supplier is ineffective in managing costs.

Risk Considerations

- Uncertainty of cost for both the contracting authority and supplier: subject to the overall cap for the contracting authority, there is uncertainty for the contracting authority in terms of outturn cost. There is greater uncertainty for the supplier as, although there is an element of pain sharing up to the maximum cap, any costs above the cap are the responsibility of the supplier.

- Complex measurement: supporting calculations for qualifying costs (as defined as a target cost) can be complex as can calculations around gain share and pain share.

- Cost assurance: supporting evidence for invoices issued to the contracting authority can require significant supporting data to be consolidated from a variety of sources and presented in a range of formats which can be very time-consuming and expensive.

9. Appendix III: Indices and Building Inflation into Contract Clauses

This appendix serves as a guide for incorporating price indices into contracts. For further information on price indices and building inflation into contract terms please contact Analysis-Econ-PI-Contracts@mod.gov.uk.

How to choose the right price index