Review of the cross-cutting functions and the operation of spend controls: The Rt Hon Lord Maude of Horsham

Published 22 July 2021

Foreword - Introduction to Lord Maude Review 2020

In the summer of 2020 I was asked by Ministers in the Cabinet Office to conduct a short review relating to the efficiency of government spending. The terms of reference were:

Over the last ten years the Government has attempted to improve government through the introduction of the functional model and Cabinet Office spending controls. Recent events, in particular the Covid-19 pandemic and its impact on the economy, mean that the government must be far more ambitious in its approach to driving efficiencies and value for money.

The purpose of this work is a) to assess the effectiveness of the functions, in particular those that drive efficiency and effectiveness; arrangements in the Cabinet Office to operate effective real-time spend controls; and progress in delivering key parts of the 2012 civil service reform plan; and b) make recommendations.

I completed the review and submitted my report in the autumn. I have made a number of recommendations, and it is for Ministers to decide which should be adopted. I have concluded that there are very substantial further efficiency savings that can be made. It is worth noting that the key to success in delivering these savings lies in the detail of how any of my recommendations are implemented.

The cross-cutting functions considered in my review - principally commercial, IT and digital, property, major projects, finance, HR - have historically received scant attention either from Ministers or the leadership of the Civil Service. Yet it is through these functions that the bulk of taxpayers’ money gets spent and on which citizens depend for the successful implementation of policies, projects and programmes for which they have voted. Even in the otherwise comprehensive Fulton Committee Report of 1968, these functions get only a passing mention. Tony Blair’s government began a programme of reform, but in 2010 there remained much to be done, with the need for radical change lent urgency by the fiscal crisis the country faced.

The pandemic has dealt punishing blows to the public finances, both in the UK and elsewhere. It is even more important today that the government is organised to ensure that every pound is spent effectively and efficiently. This Report sets an agenda for the next stage of reform. I am encouraged that current Ministers and Civil Service leaders are showing a strong interest in taking it forward.

I am grateful to officials in the Cabinet Office for administrative support in the conduct of my review, and for many in the functions and more widely for giving their time in interviews and in responding to requests for information.

FRANCIS MAUDE

Review of the cross-cutting functions and the operation of spend controls: The Rt Hon Lord Maude of Horsham

The Functional Model

In any government, there are several cross-cutting or horizontal functions that are recognisably the same wherever they exist, which include financial management, procurement, IT and digital, major projects, property, HR and internal audit.

In most governments, these functions are divided vertically: in the individual ministries, agencies or government companies. This means that there is no centre of technical expertise in the function; capability is weakened by being too scattered, which leads to great inefficiency and waste. It also means that the only flow of management information to the centre of government comes out of the top of the separate entities. When it comes to decisions on big programmes and projects, decision-takers at the centre of government are overly dependent on technical advice coming out of the top of the line ministries. There is insufficient capacity and knowledge at the centre to interrogate what is being said by the line ministries, where the technical advice may well have been skewed towards the political and/or bureaucratic preferences of the ministry’s leadership.

The Functional Model introduces a strong central authority for these functions. The heads of function in the separate entities - ministries etc - report directly to the function leader at the centre of the government, where there will be a small but cutting edge centre of technical expertise. The function leader will be empowered to enforce common standards across the government, ensure that resources are used to benefit the whole of government and that projects and programmes are implemented effectively.

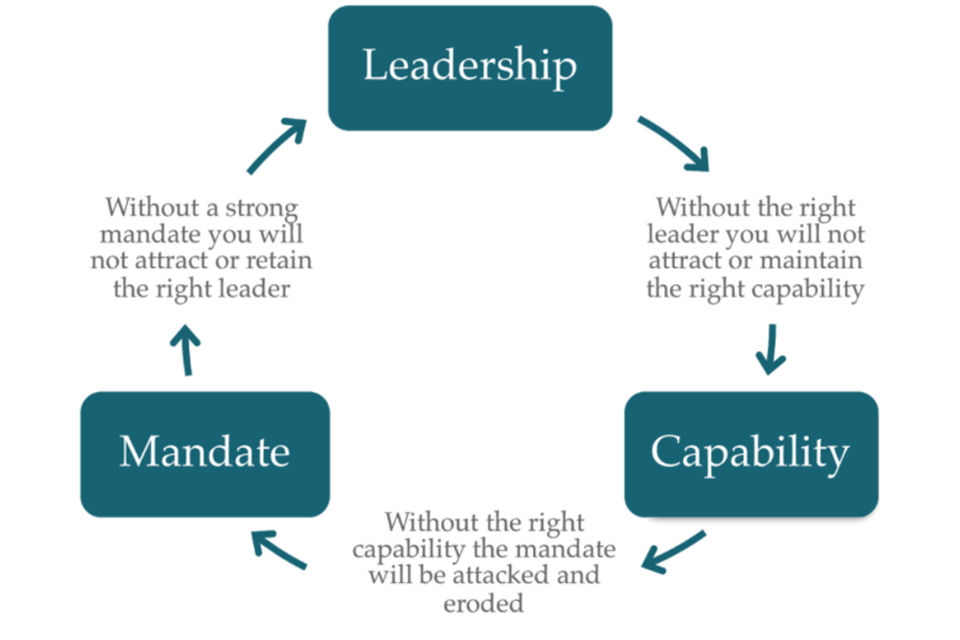

Three elements are essential for the Functional Model to succeed: a leader, with high technical credibility and the ability to lead; a critical mass hard core of high-end capability at the centre; and a strong mandate. These are closely interconnected, as this diagram illustrates. If any one of these is too weak, the whole function comes under pressure.

These functions exist in order that the government can in the most efficient and effective way serve the needs of the citizen. If implemented properly, the functional model can contribute to the creation of a headquarters function for government. This does not mean that the centre would attempt to deliver everything. Indeed the centre of the functions should be relatively small. It is however essential that they have strong leadership, a powerful mandate across government, and a hard core of high-end cutting-edge technical capability.

Background in the UK

It was clear when the Coalition Government was formed in 2010 that things needed to be done very differently. Efficiency savings that had been claimed to have been made by the previous government had evaporated under scrutiny by the NAO. There was a great deal of circumstantial and anecdotal evidence that money was being wasted. The first steps taken by the centre were to negotiate reductions in the cost of the government contracts with its major suppliers on behalf of the line departments; and to impose spend controls on property, IT contracts and advertising and marketing. An external review found that:

- “In the private sector, corporations that have moved to global functional operating models have made substantial savings.”

- “When compared to a reference group of other OECD countries, the UK government has a relatively weak functional leadership model.” This review was invaluable in confirming both the scope for and the benefits to be had from moving towards a much stronger functional model.

Over the five years to 2015, some elements of the functional model came into existence. There was no textbook for this. Some elements were spectacularly successful. GDS quickly became a global brand, winning prestigious awards for its work, being emulated by a number of other governments, and enabling Britain to be ranked best in the world for e-government by the United Nations in 2016. The Major Projects Authority turned a failure rate of 70% into a success rate of 70% in just two years. The Government Property Unit drove substantial reductions in the government’s office occupancy footprint, achieving significant financial savings and harvesting uncovenanted productivity benefits through co-location. In the later years the reforms also benefited the wider public sector as well as central government. There was good progress on the communications function; and a real impact from creating a (more or less) single legal function under the Treasury Solicitor. Commercial and procurement presented the greatest challenges.

I have heard it said in the course of my review that “nobody today disagrees with the functional model”. Too often I heard that the central functions exist to “support the departments”. Of course they should support the departments. But their mandate must enable them to intervene to prevent departments from going down the wrong path before the damage is done. A review of the operation of the functional model in 2018 reported that departmental permanent secretaries did not agree that the role of the Civil Service CEO – now COO – should include “overseeing delivery”. This illustrates the limited extent to which the functional model has been truly embraced by the leadership of the Civil Service in the Departments.

I believe it is absolutely essential that the centre of government - Ministers, the COO and the central functional leaders - must have real-time oversight and ultimately - when needed - direction over delivery.

When the first steps were being taken to introduce the functional model, there was a concern that heads of functions in the line departments would resent and resist the line of accountability to the functional leaders. To a surprising extent, this turned out not to be the case. The best of the functional heads welcomed it. Without this, too often, they can find themselves having to compromise their professional judgement because of the reality that their only reporting line is upwards within the line entity. The creation of a line of accountability to a senior, experienced and highly qualified functional leader at the centre of government increased the status and clout of the functional heads within the line departments. This was one of the uncovenanted benefits of moving to the functional model. We often talk about checks and balances within the UK government system, and this is generally taken to apply to checks on the power of ministers. However it is equally important that there are checks and balances that constrain the executive power of senior officials. The functional model makes an important contribution to this.

Generally, it will be ministers acting collectively who provide the mandate for functional leaders. Without collective ministerial leadership, official leaders are unlikely voluntarily to cede mandatory powers to the centre. Indeed if they did, because it is voluntary, they could reverse it just as easily.

A crucial element in the successful partial introduction of the functional model in the Coalition Government was the Cabinet sub-committee, PEX(ER). Its remit covered efficiency and reform, and included setting strategies for the cross-cutting functions and establishing the mandate for individual functional leaders. At some stage after 2015, this sub-committee was disbanded. I recommend:

- A Cabinet sub-committee on efficiency and transformation should be established, co-chaired by the Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster and the Chief Secretary, with the Minister for Efficiency and Transformation as a member, and including ministers from the major spending departments.

Recruitment of functional leaders

The government of a country like Britain operates at scale, and undertakes tasks of the highest importance. The government leaders of the technical functions must therefore be among the very best that there are. It will always be desirable with these functions to mix internal and external appointments - there is much for both sides of the public-private divide to learn from each other.

Functional leaders must have real qualities of leadership: the ability to inspire, persuade and take people with them. They must also possess the requisite expertise to inspire confidence and build the necessary capability. It is often said that in order to attract the very best functional leaders from outside government it is necessary to offer remuneration that is competitive with what they can command in the private sector. I disagree with this view. The attraction for people at the top of their field to join the government is the opportunity to drive change and deliver results, making a difference on a grand scale that benefits their country.

The biggest deterrent for these top players is concern about how they will be treated when they join. Too much still remains of an outdated class divide in the civil service between Whitehall “policy” officials, who - usually - still get the top jobs, and the professional specialists - finance, commercial, technology, HR, project management and so on - who see less of ministers, don’t generally get the top jobs, and yet are expected to implement decisions and run government operations which spend hundreds of billions of taxpayers’ money. Parity of esteem is essential, and we are still some way short of it.

There is a wider issue around the ability and willingness of the Civil Service culture to absorb and benefit from those recruited from outside. The Baxendale report in 2015, based on many interviews with external hires, highlighted the “club” culture which keeps at bay those from outside unless they accept the compromises involved in joining the club. As one distinguished recruit from business put it:

“You search for a way in, eventually locate the door, but find it only opens from the inside”.

These are deep cultural issues which need to be resolved over time if the British civil service is genuinely to become the best in the world. The first step is to acknowledge them.

There are other issues around the ability of government to attract and retain the very best into these crucial leadership roles. One is about whether the leader will have the clout to make big, difficult things happen. For functional leaders at the centre of government, this is about the mandate. Part of that is the formal mandate, in which the role of a reinstated cabinet committee is important. But it is also really important for functional leaders to have a strong sense that senior ministers will support them.

To be effective, some of what they need to do involves challenge to the Civil Service leadership in line departments, and this is hard to do without the confidence that ministers at the centre of government will support and protect them. The problem is exacerbated because Ministers are excluded by the Civil Service Commission from being overtly involved in appointing these leaders. This flows from the long-standing doctrine that key policy officials must be and be seen to be politically impartial.

However for the most part these functional leaders operate in fields where their political dispositions are utterly irrelevant. The most important element must be that there is a sensible and short recruitment process to attract the best people – and to allow ministers to be properly involved in their recruitment. For that reason, I recommend:

- Consideration should be given to revising Civil Service recruitment principles to ensure a sensible and proportionate process similar to those used in the private sector for the appointment of functional leaders. Moreover, for these functional leaders to be effective, they need to carry higher status. I recommend:

- Functional leaders should be appointed at either permanent secretary or director general level.

The Policy Function/Profession

This is generally held to include mainstream Whitehall officials who provide policy advice to Ministers. While they certainly undergo some forms of training, there do not seem to be any kind of formal hoops of testing or accreditation through which they need to pass in order to progress.

A government needs three things from the majority of its policy officials. First, it needs pools of deep and expert subject matter expertise, where knowledge is accumulated and maintained with real continuity, a well-organised collective institutional memory, and continuous updating. Second, it needs the ability to marshall and analyse data and evidence in a rigorous and comprehensive way, delivering insights and conclusions from the analysis of the evidence. Third, it needs a relatively small cadre of real generalists - with analytical capability of the highest order - who can be moved into demanding positions as business need and events require.

The first is compromised by the Civil Service promotion arrangements which encourage officials to rotate into new jobs in an uncontrolled way. This has made the development and maintenance of the institutional knowledge bank impossible. The second is compromised because analytical skills and techniques seem not to be a priority in the training and assessment of policy officials. The third exists – but because there are so many generalists there is insufficient focus on developing and managing the really tight and elite cadre that is needed.

An excellent recent development is the creation of a cross-government “analysis function”, headed by the National Statistician. This function encompasses a number of occupations, including statisticians, economists and actuaries. I recommend:

- The National Statistician should be tasked with undertaking a comprehensive audit of analytical capability in the universe of policy officials, with a rigorous assessment and accreditation programme, and with devising an improvement programme.

The mandate for the functions

Functions should be expected to carry out the following tasks:

- Developing capability

- Continuous improvement

- Setting and enforcing standards

- Providing expert advice

- Setting and enforcing cross government strategies

- Developing and delivering services

It is essential that there is clarity about the role of the central functions in all of these tasks, and I deal with each in turn in this section. The central functions must have a strong mandate on all of these tasks, but with considerable discretion on how they exercise that mandate. It simply doesn’t work to try to design the perfectly balanced one-size-fits-all model.

I stress that a strong mandate is not a substitute for functional leaders who can win goodwill and buy-in from the line departments. Functional leaders must have real qualities of leadership: the ability to inspire, persuade and take people with them. They must also possess the requisite expertise to inspire confidence and build the necessary capability.

I have observed a significant weakening of the mandate of the central leadership of most of these functions since 2015. It must of course always be possible for these mandates to be refined and amended over time; however it should not happen by stealth. I recommend:

- When decisions have been taken on the implementation of my recommendations in this report, they should be conveyed to the Chair of the Public Accounts Committee with details of the revised mandates to be held by the leaders of the functions.

- There should be an agreement with the Chair of the PAC that no subsequent changes should be made to those mandates before the Chair of the PAC has been notified.

Develop capability and continuous improvement

Key to successful implementation is really serious assessment and accreditation of professionals within that function across government. I have made recommendations on this in relation to multiple functions.

The role of the central leader of the function in the appointment of function heads in line departments and entities is also critical to success. There is a very mixed picture across the various functions. I recommend:

- Appointments of function heads in line departments and entities should be made by the functional leader at the centre, with the agreement of the permanent secretary.

Setting and enforcing standards

The central functions should set standards across government, but they must also ensure that they are enforced. This means sanctions for non-compliance, and a power for the central function to require real-time visibility where they have reason to believe that a department may be falling short of full compliance.

Providing expert advice

It is essential that the advice provided by central functions is genuinely expert. The central functions do not need to be huge - indeed I have been surprised at how large some have grown - but they must however contain capability of the very highest quality. This is a crucial factor for gaining buy-in from the departments. This is a mixed picture at present.

Of course, the quality of the capability starts with the functional leader. That leader must have high technical and professional credibility, and needs the self-confidence that credibility brings, to be ready to exercise the mandate and to overcome the gaming and diversionary tactics which too often in my experience were the hallmarks of departmental resistance to central leadership and direction. With leaders of that quality, it becomes possible to recruit into the central functions capability of the very highest quality at well below their private sector market rates because they see the opportunity to be part of delivering change on a historic scale.

Delivering expert advice is not the end of it: function leaders must be able to exercise direction as well. Central to this are spend controls and the ability to stop departments from doing the wrong thing, which are an essential part of the functions’ mandate. Departments are more likely to listen to expert advice from the centre that will help them to do the right thing if they know that the centre has the power to stop them from doing the wrong thing. This is covered in more detail below.

Setting and enforcing cross government strategies

This is a crucial task for the central functions. And it should go without saying that these strategies cannot simply be laid down by decree from the centre. There needs to be full participation by the functions in the line entities and departments in the formulation of the strategies so that there is some real degree of collective ownership. Different structures and processes will be appropriate for different functions at different times, and there is no universal template. It is essential that the process is not unduly protracted and that the leadership of the central functions has the ability to resolve differences and get closure in good time.

It ought to go without saying that the central functions must also have responsibility for enforcing compliance with the strategy. Again, spend controls are central to this. I have referred previously to the need for a cabinet committee which is empowered to sign off and put a collective ministerial stamp on these functional strategies. Experience suggests that even with such ministerial mandates compliance can be mixed.

In a perfect world, the development of these functional strategies would precede the comprehensive spending review. I address some of the funding issues below. In some cases central functions are strong enough to have put together a compelling cross government strategy to inform the spending review. In other areas sadly this is not the case.

Develop and deliver services

One of the Aunt Sallies put up to discredit the functional model is that its advocates believe that everything should be delivered by the centre. Nothing could be further from the truth. Of course there are some activities that are best delivered from one place for the whole of government. The purchase of commodity goods and services should be done in one place for the whole of government to maximise the buying power of the whole organisation. Common technology platforms should be developed in one place for the whole of government: gov.uk/notify and gov.uk/pay are notable examples.

When it is agreed that services should be delivered in one place for the whole of government, there should be no inhibition about this being done from the centre. There have sometimes been anxieties about whether the Cabinet Office should be a “delivery department”, and attempts have often been made for “whole of government” activities to be delivered from one of the line departments. I am not aware of any cases where this has been a success, and the temptation to move a central function to a line department should be resisted. It is perfectly normal in big complex organisations for some activities to be delivered from headquarters.

Having said that, of course most activities will be delivered by the functions in the line departments. However, it must be clearly understood that there will be oversight and direction from the centre of the function.

Funding

Many of the difficulties and conflicts around the mandate for the central functions have arisen because of the recharging model. At the heart of the recharging model is the mistaken idea that this is a quasi-commercial relationship, where the central function is a supplier and the department a customer. A true functional model cannot work on this basis. As I make clear elsewhere, the centre must in the last resort be able to direct departments. It is a fundamentally different kind of relationship. I recommend:

- Recharging for services provided by the central functions should in general be replaced by a simple allocation of “head office costs” to the line departments and entities. ‘Hard charging’ should be permitted only in rare and specific cases, and only with the explicit consent of Ministers at the centre of government.

The Functions

Commercial

Government procurement of goods and services accounts for around one third of total government spending. The commercial function, which has responsibility for government procurement, carries a heavy burden of responsibility to ensure that value for money at every stage is delivered. The commercial function has come a long way since 2010 but there is much more to do.

There are three stages in any procurement. First comes pre-tender market engagement, when commercial experts engage in a knowledgeable and confident way with potential suppliers to scope out the best way for the procurement to be structured and the specification to be drafted. Then comes the formal tender process following which a contract is awarded. The third stage is the effective management of the contract. In 2010 it was clear that there was inadequate capacity to undertake the first stage with confidence. All the focus was the second stage which was often extremely protracted and expensive both for the procuring department and for bidders (and therefore in turn for the department, through higher prices to compensate for the cost of the tender).

It is clear that the commercial function across government is now in much better shape than in 2010. A systematic assessment and accreditation process, launched around 2014-2015, has led to a marked improvement in the capability of procurement and commercial personnel across government. This has meant that procurements are much more likely to focus on the commercial outcome rather than rigid adherence to a protracted process. One innovation in 2010 was to start to treat the biggest suppliers to government holistically. The strategic supplier initiative, with experienced Crown Representatives man-marking each strategic supplier, has improved the extent to which these suppliers are required to deliver real value for the taxpayer’s money.

Central procurement

There are numerous categories of spend on goods and services which are essentially the same wherever they are bought and used. This ranges from basic stationery and IT equipment through to energy, vehicles, and so on. High performing organisations ordinarily expect to buy these commodity goods and services as a single organisation, using the buying power of the whole organisation to drive the best deals - which of course is not just about the lowest price; it is about the optimal balance of quality and price.

The Cabinet Committee, PEX(ER), decided early in the Coalition Government that central procurement of commodity categories should be introduced. This decision was not implemented at the time, and so far as I can see little progress has been made since to implement it. I believe this now needs to change. It is not possible to forecast accurately the savings that will accrue from it, but it is certain that it will run into billions. I recall that stationery, electricity and fuel were being successfully purchased for the whole of government, but little else. Indeed CCS currently allows for 23 alternative suppliers for passenger vehicle purchases which prevents savings through standardisation or volume.

The central procurement of commodity categories is different from the use of frameworks, which is CCS’ principal operating model (and the one used for vehicle purchases) - and has been from way before 2010. Typically frameworks do not aggregate demand, and do not set a single price. Their principal benefit is to provide a convenient contracting arrangement through which line entities can purchase as they determine their individual needs. These are real benefits, but leave very large amounts of unharvested savings on the table.

Central commodity procurement beyond the use of frameworks is hard to do. It requires a determined will from the centre of government to overcome the resistance from departments, and serious expert capability in the central buying entity to ensure that it is done well. It will require a strong mandate backed by ministers, with spend controls enforced strictly as each category is brought into central procurement to ensure that departments use only the central deals. It requires departments and other central government entities to provide to the centre their best estimate of their future needs so that overall demand can be aggregated, and the best deal be negotiated. It requires some standardisation to be imposed, which is hard; entities tend to claim that their requirements are entirely unique and distinctive. In a few cases this may be true; however in most cases it is not. A very high bar should have to be met before any exceptionalism is permitted.

This cannot be done overnight, nor should all of it be attempted at once. The introduction of central procurement will take at least three years, and must be carefully sequenced. I recommend:

- The head of the Government Commercial function and the CEO of CCS should be asked to prepare an implementation plan for the phased extension of central procurement of commodity goods and services.

- An immediate start should be made with a category where strong capability exists within CCS, and where there is least scope for exceptionalism.

A review in 2013 and another in 2015-16 revealed that significant Exchequer risk existed in many parts of central government because the quality of contract management was so poor. Too often, contract management has been delegated to junior officials without commercial experience or background, who are ill-equipped to interact effectively with suppliers or to exact high performance standards from them. It is essential that just as much emphasis should now be placed on the assessment and accreditation process for contract managers as the equivalent process for procurement professionals. I recommend:

- The Chief Commercial Officer should submit to the Minister for Efficiency a plan for completing the assessment and accreditation process for current contract managers.

- The Chief Commercial Officer should be given a mandate to ensure that all contracts are being managed by properly accredited contract managers.

Digital, Data and Technology

The Digital Economy Council (DEC) report addresses the digital, data and technology (DDAT) function and I was able to feed in comments to an early draft.

The UK has fallen from 1st to 7th in the UN rankings. In that period, it has made several leadership changes at the top of the function; diluted direction and leadership from the centre to departments; overseen a severe diminution in open data; and put a far weaker emphasis on delivery by the centre. The challenges to the DDAT function are structural and cultural.

The DEC Report outlines seven challenges that stand in the way of meeting the government’s admirable ambition “to make UK government digital services the best in the world”. I agree with this analysis of the challenges. However, there is a thread which runs through the first five challenges which I would draw out. This concerns the role of a strong functional model in addressing them. More specifically:

- “Uncertain quality” of technical product delivery - it is only with a really strong functional model that you will get a critical mass of top end technical capability.

- Unaddressed legacy systems and technical debt - this challenge exists because strong central direction and capability is needed to tackle the challenge across government departments.

- Relatively weak operational performance monitoring - you need a strong centre with the capability, mandate and credibility to monitor operational performance.

- Failure to leverage scale - scale doesn’t leverage itself spontaneously; it requires a strong centre with a strong mandate.

- Missed opportunities in leveraging Government held data sets - leveraging government-wide data doesn’t happen spontaneously, it requires leadership and capability at the centre with a strong mandate. It is important to acknowledge that there are success stories. GOV.UK has continued to be the (mostly) undisputed single web domain for the government, and has clearly performed very well through the fast-moving demands of Brexit and Covid. The Notify, Verify and Pay platforms have supported the rapid creation and scaling of many critical new services in the past few months. At the same time, a handful of departments have clearly built significant digital capacity, and the ability of HMRC to deal with the radically different demands created by Covid illustrates that. What unites these successes is what made GDS successful in the first place: an emphasis on trust, users and delivery.

GDS

The repurposing and rebuilding of GDS as a cutting-edge world-leading driver of digital transformation is urgent. I recommend:

- The government should accelerate the recruitment of a chief digital officer - GCDO. The GCDO must have a strong mandate to oversee and direct digital, data and technology across government.

- The GCDO’s mandate should include authority over the user experience across all government online services and, through the operation in real time of the digital spend control, the power to direct all government online spending.

- It should be made clear that line departments will be held accountable for digital and technology delivery by the GCDO and ministers at the centre. The GCDO’s mandate should include leading the recruitment, appointment, appraisal and remuneration of chief digital officers in the line departments.

- A new CEO of GDS should urgently be recruited at director general level. If this appointment can be made from within government, it should proceed without delay, and without waiting for the appointment of the GCDO.

- The new GDS CEO should be encouraged without delay to start repurposing and rebuilding GDS as a smaller but much more capable digital centre of government. This must include the rebuilding of capability within GDS to deliver digital transformation.

- The “Automation Task Force” should immediately be placed under the newly appointed CEO of GDS.

- The Civil Service COO should set a date later when permanent secretaries are invited to explain the basic technology architecture of their department in front of their peers, the GCDO, the COO and the Minister.

- A replacement for the GDS real time performance platform gov.uk/performance urgently be constructed, with line departments mandated to provide real time data feeds to it.

- Notwithstanding the existence of a partial digital pipeline, the digital spend control should be operated rigorously real time, with the Minister for Efficiency making decisions with the advice of the GCDO.

- The four “red lines” introduced by the Coalition Government should be rigorously enforced using the spend controls: ○ No IT contract to have a lifetime cost above £100m ○ No contract extensions ○ No systems integrator to be also a service provider to the same entity ○ No hosting contract to be more than two years.

- An audit should be conducted of a selection of recent digital transformation projects to assess the extent to which they comply with user need, and the extent to which the product was tested with real users continuously during development.

- A new central acceleration entity should be created under the GCDO, with strong powers of mandation, to assess the current state of the legacy backlog, and devise and direct a comprehensive whole of government strategy, with ruthless prioritisation and sequencing, for the replacement of the obsolete technology legacy in line departments and entities. It should create a central register of all data centres used by government, and use this to drive improvements in performance, security and efficiency. Its overall task would be to partition and contain the brownfield legacy, while a renewed and revitalised GDS oversees and directs the greenfield replacement. The GCDO should receive advice from the security function on cyber security risk associated with legacy tech.

Data

The Government has multiple different data sets covering the same subject matter. We do not need a single “data lake”, but we do need a single canonical data set for each subject matter - businesses, addresses, etc - which is genuinely as accurate as it can be and which can be used - in a carefully controlled way - by outside providers and developers.

Government should re-boot its open data programme. There are public benefits too numerous to describe here from this: real time accountability for the government; stimulating improvements in data quality and accuracy; providing raw material to the UK tech sector and making the UK a magnet of data entrepreneurs and developers. The UK at one time led the world on transparency and open data. I recommend:

- The government should make a public commitment to move over the next five years to create single canonical data registries for each category of information, replacing the multiple data sets that exist in different parts of the government covering the same categories.

- DEC report recommendation 8, to create a government data application centre of excellence, should be adopted. It should report to the GCDO, and be closely coordinated with the renewed and revitalised GDS. It should have a wide mandate, including the power to review government data sets.

- The government should renew its commitment to open data and transparency, with an aggressive programme to release data sets in accordance with the open data charter.

Major projects

Major projects and programmes are vital to the delivery of any significant piece of policy. However, they are also vulnerable to failure on one or more of three criteria: budget, timetable and quality. Strong consistent and effective leadership by capable Senior Responsible Owners (SROs), and the deployment of dedicated and experienced project managers is essential. In addition it is important that there should be consistent and objective monitoring and oversight to provide assurance that the project or programme is on track.

Before 2010, it was routine for line departments to be left to mark their own homework when it came to major projects and as a result, monitoring and assurance was inconsistent. In early 2011, the Major Projects Authority (MPA) was established and in 2012 the Major Projects Leadership Academy (MPLA) was set up to improve skills of senior civil servants in providing leadership over these major projects. In the first two years of MPA’s operation, a failure rate of 70% was converted into a success rate of 70%.

In 2016 the MPA was merged with Infrastructure UK to form the Infrastructure and Projects Authority - IPA. The IPA has strong leadership, which should be supported to ensure that the necessary project leadership and oversight capability is in place in IPA. My focus is on the IPA’s mandate which seems to have been diluted from the original 2011 version. The decision on which programmes and projects should be included in the GMPP must be according to criteria set by ministers at the centre of government, acting on the advice of the Head of IPA.

There seem to be several documents that contain elements of the IPA’s mandate. I have been told that these are incremental, but this has led to confusion. I recommend:

-

There should be a single clear statement of the IPA’s mandate set out in a single document, with no scope for ambiguity or differing interpretations. The following should be included (the requirements immediately following mostly already exist but are now brought together in one place):

- Departments must add all projects which meet the existing criteria to the GMPP. These must be agreed with Ministers in the Cabinet Office and the Treasury, on the advice of the Head of IPA, with the Treasury able to withhold funding in cases of non-compliance.

- Departments must submit Integrated Assurance and Approval Plans (IAAPs) for all major projects. These must be validated by both the Treasury and the IPA before being recommended to pass through any gateway reviews.

- Early engagement on Major Projects is critical. The ability to influence the outcomes of such projects deteriorates rapidly after the project starts and IPA must be involved at the earliest stages. “Starting Gate” or “Project Validation” reviews should be mandatory on all major project initiatives, and should precede any announcements on cost or timescale.

- Projects must gain the approval of the IPA to pass through any stage gates. Where this is not followed, the Treasury will withhold funding until there is clear evidence that the department has implemented the IPA’s recommendations.

- The Treasury will complete an affordability assessment before any project is permitted to make any tender or contracting decisions.

- To pass through any stage gates, projects should have a competent Senior Responsible Officer (SRO) in place, with a signed appointment letter, a commitment to the required training, and a deliverable span of work agreed with the IPA.

- A formal business case, which defines the scope and operating parameters of a project, must be prepared, in accordance with Treasury guidance, for every Major Project. In addition, an “Accounting Officer Assessment” must be produced for projects or programmes on the GMPP. This AO Assessment should be submitted with the request for the AO’s approval of the Outline Business Case. In order to ensure the scope of the project and any major issues are controlled, an updated accounting officer assessment must be prepared if the project departs from the four accounting officer standards (regularity, propriety, value for money and feasibility) or from the agreed plan – including any contingency – in terms of costs, benefits, timescales, or level of risk, which informed the accounting officer’s previous approval.

- If a major project is considered to be failing by the IPA, the IPA will intervene directly in the delivery of the project. This should include the provision of commercial and expert project delivery support.

- Departments must ensure that senior, qualified project managers review all high risk major projects every 12 months. Departments must also support all capability training related to project management that the IPA offers.

- All Ministers who are responsible for major projects must attend IPA training. ○ For all significant contracts within major projects, departments must identify and put in place trained contract managers accredited by the Government Commercial Function for the lifetime of those contracts.

- Departments are required to collaborate with the IPA, providing verified & timely data, on the publication of the Annual Report on Major Projects [and the Government Major Projects and Programmes Report].

- The IPA should submit to the Prime Minister quarterly outcome data flowing from live major projects.

-

The following are additional powers that should be included in the IPA’s Mandate:

- Departments must keep, and provide to the IPA when requested, data on all their major projects. This data should be kept consistently up to date, and be accurate and complete according to the IPA’s standards.

- The data should follow a template set out by the IPA to ensure departments are recording all the necessary information, and provide consistency between departmental records.

- No SRO should be allowed to leave their role for another post in central government without the knowledge of the Head of IPA. In addition, the IPA Head must be involved in the selection of SRO for each programme in the GMPP.

- The IPA CEO will sign off all SRO appointments to major projects in the GMPP, jointly with the Departmental Accounting Officer, and has the right of veto on SRO selection for, and exit from, these projects.

- In projects where SROs will inevitably need to change, there must be a successor identified and signed on at least three months before the current SRO leaves their post. The incoming SRO must then work with the current SRO for a month before taking control to build knowledge of the project.

- SROs should be appointed for defined terms to ensure clarity on the date at which they will leave the project. The assumption must also be that they are expected to work their full notice period if they depart early.

- SROs should be offered a retention bonus if they stay the length of their agreed contract, providing that contract is longer than a certain time period. This bonus option must also include a requirement that they have been successful in managing the project.

- SROs must be MPLA qualified or hold equivalent qualifications and experience for all major projects in the GMPP.

- For projects outside the GMPP above a lifetime cost of [to be agreed with IPA], all central government line entities should be required to provide details of the SRO, including their skills, experience, tenure and time allocation.

- The IPA should be involved in the assessment of projects during the Spending Review process to ensure that the project is deliverable within the budget and timeline provided to the Treasury.

Property

There are several different types of property. My focus is on office accommodation. The introduction of the National Property Control in 2010 allowed the centre to have holistic oversight of the government’s occupancy office property. The ability to prevent a line entity from taking on a new lease gave the centre levers to drastically improve the government’s office occupancy efficiency. This led to the government’s central Whitehall Estate being better used, with colocation of departments, open plan and hot desking more accepted. Latterly in the Coalition Government, the One Public Estate programme enabled the wider public sector to participate in this holistic approach, with hubs being created in several places where numerous public bodies - central government, local government, NHS, ALBs - could be co-located.

There are obvious financial benefits from this holistic approach. Furthermore, spaces that are used more intensively develop their own vibrancy and energy, and productivity and morale improves. Colocation leads to greater collaboration and understanding across the different parts of the public sector.

In 2014 a decision was announced to establish the Government Property Agency (GPA) with the intention that it would own and manage all central government office property, whether leased or freehold. Departments and entities would then rent these from the GPA, who would accordingly be able to manage the government office estate in a holistic hands-on and proactive way. This would enable properties to be released to the private sector, deals to be done with developers for redevelopment and optimisation of leasehold properties and so on. Regrettably, the business case was not approved until 2017, and the GPA not actually established until 2018. So far only 10% of departments have been onboarded, which represents significant slippage from what had been agreed in the business case.

Sitting above GPA is the government property function which exercises some oversight of all government property activity, including specialist areas such as the defence estate, transport and so on. This central organisation will need a strong mandate. The National Property Control is at the heart of this mandate, but it also must include the ability to requisition data from all parts of central government, and the ability to act on behalf of the whole government in negotiations with private sector landlords and developers. I recommend:

- Ministers should consider whether it would be better a) to press ahead with on-boarding the rest of central government’s office estate into GPA or b) to rely on the property controls to drive efficiencies and enable value to be maximised through creating redevelopment opportunities. This review should also assess whether the GPA should be part of a single property organisation, close to Cabinet Office ministers and the COO, which exercises general oversight of the property function across the whole of Central Government and across all types of property, while exercising direct control over the government’s office estate.

- The government property function should undertake an assessment and accreditation process for property professionals across government, and the head of the organisation should be the central actor in the appointment of heads of the property function in departments and other central government entities.

- Once the central organisation has gained sufficient capability, it should begin to work with the commercial function to operate the facilities management spend control and build oversight of all government facilities management contracts.

CSHR

It has been a welcome development to appoint a Chief People Officer at a senior level to oversee HR across the government. A new and much more unified approach is essential, which will start to rectify clear deficiencies in skills and capabilities, and by doing this on a much more whole of government basis will be able to make substantial reductions in cost.

Consideration should be given to creating a “licence to operate” model, with every civil servant holding a skills passport to record their skills, training and specialisms. It is also clear that there are significant variations in HR practice in different parts of government. I recommend:

- The spend control should be used to enforce a much more unified and strategic cross-government approach to learning and development.

- Consideration be given to creating a “license to operate” model, with a skills passport for every civil servant. I believe that the time is right for a significant strengthening of the Chief People Officer’s mandate. I recommend:

- The HR function should move to the same kind of single employer model that has been so beneficial in the government commercial organisation.

- The Chief People Officer should set in train an assessment and accreditation programme to increase the capability and cohesiveness of the function across government.

- The Chief People Officer should have the power to insist on the standardization of definitions, data and HR practices across government.

Fraud, Error, Debt and Grants

If there were a strong and unified Financial Management function across the whole government, and if the internal audit service were genuinely a service that is internal to the whole of government, the fraud, debt, error and grants function would probably not need to have been created. It was brought into existence in 2010 because although it was well known that tens of billions were being lost to the Exchequer through fraud, error and uncollected debt, there was no coordinated cross-government approach to reduce the losses. Grants came into the picture later when it became clear that many different parts of central government were issuing tens of billions in grants to numerous organizations, again without any coordination. It was obvious that there was huge scope for duplication, fraud and error.

In the 10 years since the function was created, the team has struggled to get the attention it deserves from across government. Despite this, it has delivered significant benefits to the Exchequer in the prevention of financial loss.

Fraud and Error

It is estimated that billions is lost every year to fraud and payments made in error. In the US, every department has an Inspector General whose role includes ensuring that fraud is minimised. I believe that the government should now create an Inspector General covering the whole of central government.

Its mandate should be to report on progress in measuring and reducing fraud and error. I recommend:

- The Government should appoint an Inspector-General (I-G) to oversee counter fraud measures across all central government entities.

- The I-G should set in train an assessment and accreditation programme for individuals involved in counter fraud work to drive up capability in all central government entities.

- The I-G should have the power to create data sharing gateways where needed to facilitate a coordinated approach to fighting fraud.

- The I-G should have the power to put units of government into special measures if they don’t deal with fraud effectively, including where a department fails to comply with requests made by the I-G.

- The I-G should have the power to require a fraud risk assessment on each major new spending proposal to ensure that the fraud risk is understood and capable of being managed.

- While any necessary legislation is prepared, this post can be created in shadow form at the head of the FEDG functions, and so far as is possible within existing legislation these powers should be given to the shadow I-G.

Debt management

The case for a coordinated and holistic approach to debt management is obvious. There are many debtors who have creditors in different parts of the public sector. Some can’t pay, and some won’t pay. In both cases, it makes sense to manage the debtors holistically. This is both more effective and kinder to those in genuine difficulty. The Debt Market Integrator (DMI) was set up in 2014 to analyse debts provided to it by government departments and other parts of the public sector, and to commission outside agencies to collect the debt, operating holistically. I recommend:

- All central government departments and entities should be required by year end to furnish FEDG with comprehensive data on their uncollected long-dated debt and their plan to reduce it.

- The Minister for Efficiency should direct these departments to provide all of their 21 long-dated debt to the DMI on a phased basis as a crucial component of their debt reduction plan.

Grants Management

Billions of pounds are disbursed by central government in grants. Every grant programme is intended to promote some defined social or other benefits. As a matter of good practice, those benefits should be specified properly, and there must be a proper regime for assuring that the benefits are being delivered. The centre must be aware of any duplication and/or overlap where an organisation may be receiving grants from different parts of government covering some aspect of the same purpose. This will also help to avoid continuing to give grants to fraudulent organisations. I recommend:

- The head of the FEDG functions should have the power to require all central government departments and entities to: ○ Provide full data to the centre on every grant programme under their control, including details of grant recipients, so that the Grant Management Information System can be fully populated. ○ Satisfy the centre that their machinery and processes for awarding grants is fit for purpose, including follow-up monitoring.

Shared Services

The government decided in 2004 that an ambitious shared services programme should be launched. Very little happened until 2012, when the first substantive steps were taken. There was a great deal of resistance from departments and other entities, who typically would grudgingly offer to host another entity’s activity on their system, always requiring the “guest” entity to adapt their requirements to the host’s existing system. It appears that there has been little progress in driving forward shared services since 2015. There should be no more than five back office centres for the whole of government, and ideally fewer. This programme must be managed from the centre, whether the work is outsourced or continues to be delivered in-house. This consolidation is an essential lever to enable much greater standardisation of HR and other practices across government, which will greatly increase interoperability and reduce costs. I recommend:

- The head of the shared services function should be tasked with drawing up an implementation plan for the onboarding of all back office services into a maximum of five centres by the end of 2022.

Security

Although security is one of the youngest functions, established only in late 2018, it is also one of the largest, covering eleven and a half thousand employees. The security function has made some strong early steps in developing the capability of both its central team and the security teams in line entities. As with the other functions, creating genuine centres of specialist expertise will both reduce costs to the government overall and remove the need for departments to seek expensive external support. As the function looks to improve capability further, its focus should be on assessment and accreditation. On mandate, it is vital that the Departmental Security Health Check is conducted regularly (and by the security function) and that line entities are required to comply with any recommendations as a result of these reviews.

Communications

Good progress has been made on communications. However some issues still remain. Too often departments operate in silos, don’t share insights or data, and too often say different things to the same people. Government needs a clear and co-ordinated approach to its communications to best serve the public particularly in these times. The aim should be for the Government to speak with one voice with world-class communications across the board, so the public know and understand the message the Government is trying to communicate.

In communications as in so many other areas, the functional model requires that the centre of Government has oversight and control over the direction of delivery. What is needed is a small but highly professional central team running cross-governmental campaigns and coordinating messaging. I recommend:

- The Government Head of Communications shall be at least Director-General level.

- The Head of GCS should run an assessment and accreditation programme - a licence to practice - and better incentives for communications specialists to progress. It makes no sense that as of today a high performing Director level communications professional has to leave their specialist area and move to policy to be promoted. The civil service needs to be more specialised not less. To that end, only GCS should be able to recruit and quality assure communication professionals in Government. There will need to be real sanctions on departments that circumvent this quality assurance regime by recruiting “shadow” teams.

- Different campaigns by different departments on the same issue is confusing for citizens and a waste of time and money. The Government can achieve more with less if it is coordinated properly. A pooled centralised campaign budget is a vital tool in making that happen and delivering intelligent, data driven and effective cross-governmental campaigns. The spend control should be used rigorously to 23 ensure coordination.

- The advertising and marketing spend control should be applied across ALBs as well as to Departments.

- The “Great” campaign was for several years the Government’s only brand for the promotion of UK assets and attributes. The spend controls enabled the centre to enforce compliance with this and to ensure that the brand equity, developed carefully over that period, was not diluted by competing brands and campaigns being developed. At some stage since 2016 control of “Great” was transferred to DIT. It - or any successor - should now be returned to the control of GCS.

- Government communications has grown significantly. Smaller more flexible departmental teams focusing on what is agreed by the centre are their specialty areas, while the centre coordinates larger campaigns. This would be a small fast moving data-driven central HQ comms function that can deliver key cross-government campaigns while providing oversight and support across the rest of the government.

Legal

Good progress has been made since 2011 in creating a single government legal service: the Government Legal Department (GLD). This has enabled centres of specialist expertise in areas such as employment and commercial to be created. This has both reduced the need for skills to be duplicated in different places and also by creating centres of excellence has reduced the need for departments to engage external lawyers.

Two departments are not currently served by GLD: HMRC and the FCO. In relation to HMRC, most of their lawyers are tax specialists, and these are skills that are not really needed elsewhere in government. There is however a need for international law expertise in many parts of government, and it could be beneficial for FCDO to join GLD, where this expertise can be made available in an integrated way. I recommend:

- The FCDO Legal Department should be folded into the GLD.

Finance

Finance falls under HM Treasury, and is therefore outside my remit. Finance has not been a “function” in any sense that would be recognised elsewhere. Until recently, cross-government financial management was led by the Finance Director of a very major spending department, as a part-time secondary task. While he made sterling efforts to drive up quality, it is apparent that this model cannot succeed in increasing capability and financial performance in anything like the way that is needed. I am delighted that the Director-General for Public Spending in the Treasury has now become Head of the Government Finance Function. I recommend:

- The Head of the Government Finance Function should be given a strong mandate covering the appointment and appraisal of finance directors across government, and to set in train an assessment and accreditation programme for financial management personnel across government, including ALBs.

- The head of finance should be mandated to enforce universal accounting and reporting standards across the whole of government.

- The Risk Centre of Excellence in the Government Finance Function should be charged with providing a quarterly risk report, with input from the GIAA, to go to the Prime Minister and Cabinet, similar to what now appears on most corporate board agendas. This will be sponsored by the Minister for Efficiency and Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster.

Internal Audit

It was a surprise in 2010 to discover that internal audit was considered to be something that was internal to each individual department, rather than internal to the government as a whole. This is of course in stark contrast with how normal large organisations would operate. It has frequently been observed that the UK government is poor at understanding its risks in a holistic way. One of the key functions of internal audit is to assess risks and provide assurance on how they are being controlled. The creation in 2015 of the Government Internal Audit Agency (GIAA) was an important step forward, and has markedly improved the quality and professionalism of internal audit in most of the government. While there is strong and effective leadership in GIAA, three out of 16 departments continue to run their own internal audit departments.

In addition GIAA reports are currently confidential to the permanent secretary in the department they cover. This represents a change from the rubric under which GIAA was originally established. GIAA is currently obliged to treat the line departments as clients, which inevitably risks compromising the robust independence that is so important for internal audit to be effective. I recommend:

- It should no longer be voluntary for line departments and other central government entities to use GIAA. By the end of 2023, the remaining three departments should have been onboarded into GIAA, with a plan agreed for other remaining entities to follow shortly thereafter.

- The rule whereby internal audit reports are confidential to the line entity should be discontinued. A sharing protocol should be developed and agreed setting out how and under what circumstances internal audit reports should be shared by the head of GIAA with ministers and senior officials in the Treasury and Cabinet Office, having first discussed the issues of concern with the Permanent Secretary and Minister in charge of the Department.

Review of Cabinet Office spending controls

Introduction

Cabinet Office spend controls were introduced by the Coalition Government in June 2010 in response to the urgent need for fiscal consolidation. The controls were widely expected to be temporary but it became clear that they could play a lasting role in driving out wasteful expenditure. They were seen as a feature of the “austerity“ era, but in truth any organisation, whether in financial distress or not, should always be insisting on maximising the efficient spending of money. Government departments, when left to themselves, do not always exhibit a steely determination to ensure that the best possible value is extracted from every pound they spend.

Furthermore, finance ministries typically concern themselves primarily with the budget for individual line departments. Thereafter their interest in how the money is actually spent tends to diminish, even when they have the technical capability to assess it. The question they tend to ask on any item of expenditure is whether it is covered by a line in the department’s budget, and make some kind of assessment of the cost/benefit ratio. They are not always well equipped to analyse the cost side of the equation to assess whether it can be reduced to improve the cost-benefit equation and make the available money go further. For all these reasons, value for money in government spending is often poor. It is therefore helpful to have horizontal spend controls operated from the centre of government but outside the finance ministry.

One of the reasons why the Treasury has been at best ambivalent about these real-time controls may be that the savings that are made through the operation of spend controls do not flow back to the Exchequer. They remain within the control of the department, and can make a significant contribution to that department’s budget being deployed more effectively and delivering greater economic, social and other benefits. However, this also provides a real advantage to the Treasury in its essential role as guardian of the overall control of expenditure. The savings that are made through the operation of the functional model and the exercise of spend controls will certainly reduce the demand for additional spending, and thus support the Treasury’s control of the overall expenditure envelope. It is a welcome development that HM Treasury has become much more alert to these issues, and the establishment of the new Public Value unit should help to make a real difference here, with a focus on outputs and outcomes rather than inputs.

Benefits of spend controls

There are numerous benefits from real-time spend controls operated on a horizontal basis.

- At the centre of government, over time you build visibility and data over the entirety of government spending in particular categories e.g. property occupancy, specific procurement categories, IT and digital etc.

- You can suppress demand. You can ask whether Department X’s proposal to buy 50 new vehicles, or take on a new office lease is in line with relevant strategies and standards.

- Once the demand/need test is passed, spend controls enable you to bear down on unit costs. So the fleet specialists in central procurement can require the Department of X to acquire their vehicles in a particular way or from a particular supplier, so that value for money for the whole of government is maximised. The central property function can direct a Department to take space in a building that the government is already paying for rather than taking on a new lease, - even if the new lease might represent good value for that Department taken alone, it is likely that the shared occupancy will represent better value for the government overall.

- Properly administered and with good discipline, controls require departments to plan ahead more effectively. This can encourage a more strategic approach.

- Controls enable government to operate in a much more holistic and joined-up way. They can deliver IT systems that are compatible and interoperable; common terms and conditions; buildings with shared spaces that promote real-time collaboration. These are softer benefits than the hard cash savings, but just as real.

For these benefits to be realised, strong and capable central leadership of the specialist horizontal functions is essential to enable good and timely spend control decisions to be made. And spend controls are a crucial component in the mandate held by the leadership of functions, which is why spend controls and the functional model are inextricably linked.

Accountability

There is a notable lack of clarity, even honesty, around the extent to which departments are accountable to the centre for operational delivery and value for money. In the course of my review I saw an internal document where officials asserted that in their discussions with departments on spend controls, “we will emphasise that controls do not affect their … operational independence”. However, this assertion is quite simply untrue - there are few more blatant incursions into “operational independence” than the ability of the centre to tell departments how they can and can’t spend money, and is at the heart of what spend controls were set up to do. Spend controls will not work fully effectively while this issue continues to be fudged.

The issue stems from the late 19th century theology that accounting officers (permanent secretaries) are accountable only to Parliament for how they spend public money. In reality the Public Accounts Committee scrutinises spending late in the day and often when the permanent secretary responsible has departed. The reality is that permanent secretaries are remarkably immune from real time accountability for, and oversight over, how they spend public money. This was one of the issues that spend controls were introduced to address. The issue could be fudged during the Coalition Government without unduly constraining the operation of spend controls because of the imperative of financial stringency together with robust cross-government ministerial support. But it should now be resolved.

I recommend:

- There should be a clear statement that operational and capital expenditure by line entities is and will continue to be subject to real-time oversight and direction from the centre of government. In addition to normal HM Treasury controls, this oversight is effected through the operation of updated Cabinet Office spend controls and through the - also updated - mandates of the central functional leaders. Departments’ policy independence, subject of course to collective processes, remains unchanged.

Counting and publishing the savings

For all the financial years from 2010-2011 through to 2015-2016, a rigorous exercise was conducted to count - and publish - the savings made across the whole of central government through the efficiency programme, of which the Cabinet Office spend controls were a central element. There were great benefits from this:

- The public was able to see that the government was getting its house in order, and making the sort of difficult decisions that they themselves had been making in the hard times since the global financial crash;

- It was a transparent way for the government to hold itself to account for improving efficiency; and

- It enabled ministers and officials to take ownership of the difficult decisions being 28 made and to take pride in what was being achieved.

The methodology used from 2010-2015 was not perfect, but it was rigorous enough to survive expert scrutiny by numerous bodies, and the overall savings numbers are still considered to be robust. I believe it was a grave mistake to discontinue the series. All too often in government, a valuable and instructive data series has been discontinued, with the intention of replacing it with something “better”. All the value of continuity, of being able to follow trends and make comparisons, which is critical to genuine accountability, is lost. I recommend:

- Publication of numbers for efficiency savings should be resumed on the same basis as between 2010 and 2015 and figures for the intervening years should be published.

Exemptions

Numerous entities within the central government’s ambit have been exempted from spend controls. The Minister for Efficiency and Transformation has already instructed that all of these exemptions must be presented to him so that he can make a decision on whether the exemption should remain. I strongly agree with this approach, and recommend:

- There should be a presumption that there are no exemptions at all unless there are specific and powerful reasons. The bar for exemption should be set very high.

Pipelines and earned autonomy

In April 2016 a “pilot” approach to controls was introduced, in which GDS and the commercial function would “scrutinise IT, digital and commercial expenditure via consolidated pipelines for relevant projects and programmes which would be reviewed on a quarterly basis”. Coming on board with this pipeline approach seems to have been voluntary for departments, and participation is still far from complete. This partial move to a less intrusive approach to spend controls inevitably created the impression that real-time spend controls were on the way out across the board. I suspect that this has contributed to a decline in compliance since 2016.

Continued visibility by the central functions - including through pipelines - is indispensable, but participation in these pipelines is not a substitute for the operation of real-time spend controls at the time of commitment.

I heard a great deal about “earned autonomy”. The idea is that line departments that show that they can operate in a responsible and efficient manner should enjoy more autonomy and be free from the need to submit to the same degree of oversight and control as the less efficient. There are obvious attractions in this approach. The problem is that without continuing real-time visibility over what the department is doing all too often things go backwards. Even at its best, the department may make decisions that look perfectly sensible when seen only through its own lens but which militate against the overall interests of the government when seen holistically. This is especially true in the cases of IT (systems introduced which are not interoperable with other parts of government), commercial (dealing with suppliers separately reduces the buying power of the government overall), and property (a department considering only its own needs may close out relocation and co-location options that benefit the government overall).

Trying to formalise and institutionalise “earned autonomy” is therefore a mistake. It can require extensive negotiation, with definitional challenges coming to the fore. In any event it is in the nature of the functional model that it will always be for “head office” to decide how to operate its controls. Typically, controls become looser in good times, while in tough times the strings are rapidly drawn in. But in either case, the decision is to be taken by the centre.

The better approach to delivering earned autonomy is to maintain the control framework on the tight basis that I am recommending here, but to operate the controls on a pragmatic and risk-aware basis.

I recommend that:

- A pipeline for future property transactions eg lease terminations and lease breaks should be established;

- It should now be made mandatory for all departments and entities subject to the controls regime to participate in the current commercial and DDAT pipelines (and future property pipeline);

- Notwithstanding the operation of the pipelines, the centre must decide in each case whether spend controls should operate at the moment when it is intended to enter a commitment.

Thresholds

These have been set at different levels for the various controls from the outset. These were refined during the Coalition Government, and have seen numerous changes since, all upwards, with the effect of excluding ever greater volumes of spending from real time scrutiny. I believe that the time has come for this trend to be reversed. I deal below with each of the controls in turn.

Commercial

The principal spend control on commercial covers the management of disputes as well as 30 spend. The threshold for this control was raised from £5 million to £10 million in 2016, and its scope extended from spend with strategic suppliers to cover all spend. I recommend:

- The threshold should be returned to £5 million.

The commercial models control was removed in 2016 on the basis that the potential transactions were already covered by controls operated by HM Treasury. The original control covered the following transactions:

- all disposals of a business, the assets involved in delivering a service, or both;

- all outsourcing contracts, or significant extensions of existing contracts, above £5m;

- the creation of any new organisation, including (but not limited to) a spin-off from central government, joint venture, public corporation, charity, public service mutual, or social enterprise, in-house delivery and conventional outsourcing.

This gave the Cabinet Office visibility over all of the activity that might present an opportunity to innovate. This led to the creation of more than 100 public service mutuals owned and led by the workforce; and mutual joint ventures that delivered services significantly cheaper while giving the government a valuable carried ownership interest in the new entity, such as the Crown Hosting Service.