Exploring loneliness stigma through qualitative interviews and focus groups

Published 12 June 2023

Executive summary

Overview of the research

This report presents the findings from a qualitative study exploring loneliness stigma. Previous research has highlighted that both self- and social stigma can present barriers to sharing and overcoming feelings of loneliness. For the purpose of this research, loneliness and stigma are defined as follows:[1]

-

Loneliness: “A subjective, unwelcome feeling of lack or loss of companionship. It happens when we have a mismatch between the quantity and quality of social relationships that we have, and those that we want.”[2]

-

Social stigma: Negative attitudes or beliefs towards an individual or group, based on experiences or characteristics which are seen to distinguish them from other people (in this case, experiences of loneliness). This results in the person or group being devalued and/or suffering discrimination.[3],[4] This research explores actual and perceived social stigma.

-

Self-stigma: Feeling shame around a personal characteristic or experience and being inclined to conceal it from others. [5]

-

Stigma: Covers both social and self-stigma.

The Department for Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) commissioned this study to explore loneliness stigma and address evidence gaps identified in reviews of the literature. The Tackling Loneliness evidence review (published on 26th January 2022) critically examined the existing literature on loneliness, identifying that little was known about loneliness stigma. The Loneliness Stigma evidence review was subsequently commissioned to explore existing research on loneliness stigma. This review identified specific evidence gaps around how loneliness stigma is experienced and how it can be tackled, subsequently recommending further qualitative research to explore the drivers of loneliness stigma across different population groups, along with how interventions could effectively tackle such stigma.

This research aimed to explore:

-

Understandings and expressions of loneliness.

-

Barriers that prevent people from taking actions to overcome their loneliness.

-

The experience of loneliness stigma, and strategies for reducing this stigma.

-

How these issues are experienced across different population groups.

The report draws on findings from:

-

Six interviews with professionals with experience tackling loneliness stigma (“stakeholders”).

-

Forty in-depth interviews and diaries completed by participants experiencing loneliness regularly (“interviewees”). These participants were recruited based on their age/life stage (young adults (age 16-30); parents of young children (age 27-35); middle-aged (age 40-60); retired people age 65+).

-

Three focus groups with participants with little or no recent experience of loneliness (“focus group participants”) to explore wider societal understandings of loneliness. Each focus group contained participants from one age group (16-34; 35-64; 65+).

Key findings

Understandings and expressions of loneliness

As detailed in the Government definition of loneliness above, this research found that experiences of loneliness are related to negative feelings about quantity (i.e., number) and/or quality of social connections. Spending time alone could drive feelings of loneliness for interviewees, regardless of the number of social connections they had. For those with a higher quantity of day-to-day connections, experiences of loneliness were also driven by negative feelings about the quality of their connections. This included feeling disconnected from others and/or wanting specific additional connections, such as a romantic partner.

The Government definition gives equal weight to experiences of loneliness which are driven by negative feelings about quantity or quality of social connections. However, there was a view presented by some interviewees and focus group participants that more “serious” loneliness relates to the quantity of connection and is experienced by people who are socially isolated. This view was contested by other interviewees and focus group participants, with some interviewees highlighting that their most difficult experiences of loneliness were driven by feelings of disconnection (i.e., quality of connection). Interviewees attributed their feelings of loneliness to a variety of life experiences, including health conditions, life events and commitments (e.g., parenthood). These experiences caused physical and emotional barriers to connecting with others. A common view across the interviews and focus groups (i.e., those with regular and little/no recent experience of loneliness) was that everyone is likely to experience some form of loneliness at some point in their lives. However, some interviewees felt that loneliness within certain population groups was harder for society to understand. For example, both young people and new parents felt that their experiences were dismissed (or not recognised at all) due to assumptions that their needs for social connection were met by those around them. While focus group participants perceived that loneliness could be experienced at any age, one perspective (raised across all three groups) was that older people might experience a more severe form of loneliness due to having fewer opportunities for connection.

Interviewees had mixed perspectives on whether their experiences of loneliness were driven by circumstance, their actions and/or the actions of others. Where interviewees linked their loneliness to their own actions, this tended to be driven by feelings that they should be doing more to seek out and develop connection with others. When discussing the causes of loneliness in others (i.e., outside personal experiences), both interviewees and focus group participants demonstrated consideration and sympathy. However, some of these participants attributed loneliness in others to internal causes (e.g., lack of confidence) or felt that others could do more to control or overcome their experience.

Barriers to managing and overcoming loneliness

Interviewees felt that sharing feelings of loneliness helped them feel less alone and more able to manage their experience. However, some interviewees had little experience of talking about how they felt. Barriers that made it more difficult to share feelings of loneliness included:

-

Past responses to sharing feelings of loneliness. These responses included limited experiences of negative reactions (e.g., experiences being dismissed and assumptions of blame) and wider responses that interviewees considered unhelpful (e.g., offering unwanted advice or attempts at distraction).

-

Fear of how others might react. Interviewees also refrained from sharing experiences due to concerns about being judged, pitied or perceived differently. While some interviewees had negative experiences of sharing their feelings, others felt these fears stemmed from their own assumptions or internal thought processes (e.g., anxiety).

-

Fear of burdening others. This fear was experienced across all interviewee groups, but specifically applied to those who identified some form of care and support responsibility (e.g., for family or friends). In some cases, this fear was driven by cultural or gender stereotypes around caring.

-

Lack of opportunity or means to discuss loneliness. While some interviewees described themselves as “private” or struggled to express their feelings, there was also a more general sentiment that there is a lack of language around loneliness. This perspective was echoed by some focus group participants (not experiencing loneliness), who lacked the language and tools to discuss loneliness with people experiencing it and help identify solutions.

Interviewees also identified wider actions which they had taken to overcome loneliness, including joining groups and learning to enjoy time alone - this included taking steps to do enjoyable activities alone (e.g., hobbies or holidays). There were a number of barriers to taking these actions – which often overlapped with causes of loneliness – including lack of time, financial and emotional barriers to connection and accessibility concerns.

Loneliness stigma

The findings in this report demonstrate perceived social stigma and self-stigma, with some (limited) evidence of actual social stigma.

-

Exploring actual social stigma involved examining attitudes towards those who experience loneliness, to understand the extent of negative perceptions. This report has paid particular attention to whether opinions ascribe blame to those who feel lonely, as this emerged as a driving factor of social stigma in the Loneliness Stigma evidence review. Some interviewees had experienced negative responses when sharing feelings of loneliness. In some cases, these responses could be considered stigmatising (in line with the definitions used in this research), for instance where jokes were made, or responses assumed blame. However, many responses interviewees considered unhelpful (e.g., “glossing over” their feelings) were not necessarily suggestive of negative beliefs around loneliness. Some focus group participants and interviewees perceived that loneliness in others could be caused by individual traits and actions, such as low confidence and self-isolation. However, only in some cases did these opinions lead to responsibility being ascribed to those experiencing loneliness. Generally, these opinions were presented with sensitivity and understanding (e.g., an understanding that some people may self-isolate due to health issues). Both interviewees and focus group participants were open to reflecting on their views and proactively questioned some of the more “stereotypical” views that they presented (e.g., loneliness being common among older people).

-

Exploring perceived social stigma involved examining whether people who feel lonely perceive that others hold negative opinions about loneliness. This was considered separately to experiences of actual social stigma (see above). There was a perception of social stigma among interviewees. This included perceptions that loneliness is seen as a weakness and those who feel lonely are seen as “odd”, “sad” or blamed for their experience. While participants tended to believe that everyone experiences loneliness, some interviewees felt that the stigma they perceived was driven by a societal lack of understanding about who experiences loneliness and what causes it.

-

Exploring self-stigma involved considering whether people experiencing loneliness felt embarrassment or shame around their experience and were inclined to conceal their feelings. While some interviewees had shared feelings of loneliness, others did conceal their experiences due to embarrassment or shame. These feelings were driven by factors such as self-blame or feeling that they “shouldn’t” be lonely. As well as having concerns about what others might think, interviewees worried that sharing would impact how they felt about themselves. This included worries about feeling “needy” or vulnerable. While some fears appeared to be driven by experiences or perceptions of social stigma (rather than actual social stigma), other participants felt that their concerns were driven by internal thought processes (e.g., internal anxiety about how they presented themselves to others).

Recommendations to tackle loneliness stigma

This research indicates that the following actions would help reduce social stigma (perceived and actual) and self-stigma around loneliness:

-

Use of national campaigns to normalise loneliness. It was suggested that promoting loneliness as a normal and universal emotion would help those experiencing it to feel part of the majority, rather than the minority (thereby reducing self-stigma). It is recommended that campaign design considers the following:

-

Recognising a diverse range of experiences of loneliness. As well as ensuring that all campaign imagery is inclusive and diverse, stakeholders suggested focusing on the variety of drivers of loneliness, including life events and/or circumstances, such as parenthood, health and employment changes.

-

Reframing loneliness to remove some of the negative connotations. Given the findings in this report, it may also be helpful for campaigns to consider messaging which targets blame around loneliness or fears of being burdensome to address both self- and (perceived and actual) social stigma.

-

Making campaigns accessible to different population groups. Tailoring campaign messaging to different target population groups was proposed to ensure that messaging is accessible and relevant to all.

-

Taking more direct steps to support people to discuss experiences of loneliness. Wider actions could mitigate loneliness stigma, such as encouraging group discussions around experiences of loneliness, signposting to loneliness-specific services and supporting other services to identify and support people experiencing loneliness. Schools, workplaces and other organisations can all play a role in normalising day-to-day discussion of loneliness.

A number of enablers could support organisations to address stigma through national campaigns and direct support mechanisms. In particular:

-

Considering the language around loneliness. In service delivery and campaigns, the language used around loneliness needs to be carefully constructed, so as to not perpetuate stigma. This could include avoiding negative words like ‘tackle” and using a range of terms to describe support/services (including more positive terminology such as “connecting,” and “building relationships”).

-

Coordinating across organisations. Collaborating with partner organisations who work “on the ground” could help ensure services and campaign messaging considers diverse lived experience and reaches wide-ranging groups. Stakeholders also suggested that further coordination of campaign activity across relevant organisations could ensure year-round messaging.

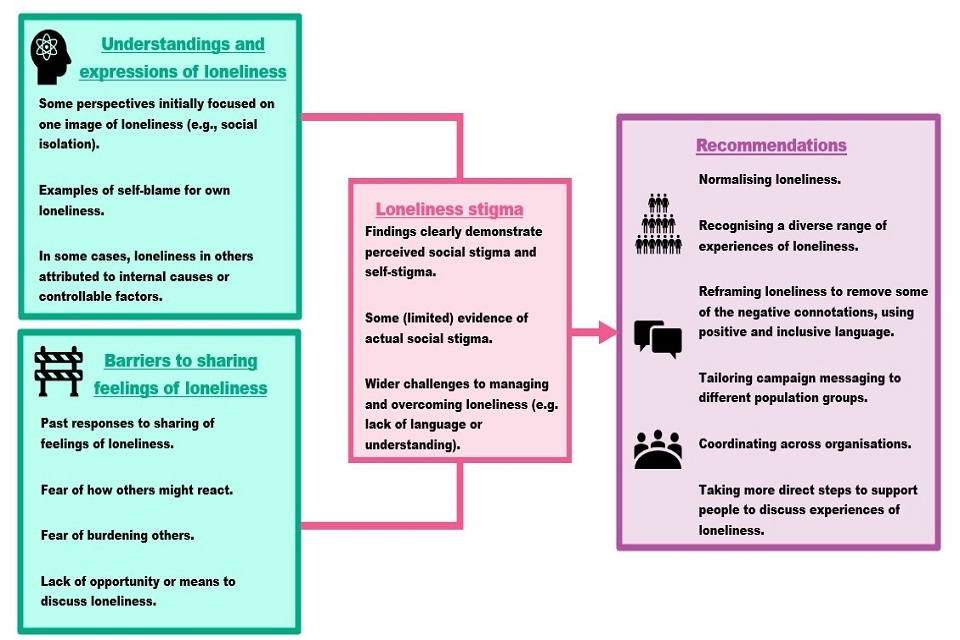

This research demonstrates that normalising loneliness, tackling negative associations and encouraging conversations would help people experiencing loneliness feel less alone, help remove associated internal shame (i.e., self-stigma) and anticipate more positive reactions from sharing their feelings (thereby reducing perceived social stigma). There is also the potential for these actions to address actual social stigma by addressing some of the more “stereotypical” or negative perceptions of loneliness. There are wider barriers to overcoming loneliness which would need to be addressed alongside stigma (e.g., practical challenges to socialising such as lack of childcare, local groups or free time). However, this research suggests that these actions still have the potential to help people feel less alone and more able to manage their experience, even where the experience of loneliness cannot be completely overcome. Please see below for an illustration of the key findings:

Figure 1. Key findings

[1] These definitions align with recent academic papers on loneliness stigma (e.g., Barreto et al., 2022 which reports on the BBC Loneliness Experiment).

[2] Drawing on Perlman and used in the UK Government’s Loneliness Strategy (2018), D. and Peplau, L. A. (1981) Toward a Social Psychology of Loneliness. In R. Gilmour & S. Duck (Eds.), Personal Relationships: 3. Relationships in Disorder (pp. 31-56). London.

[3] Drawing on Link, B. & Phelan, J. (2001). Conceptualizing Stigma. Annu Rev Sociol, 27, 363–85.

[4] Drawing on Barreto, M., van Breen, J., Victor, C., Hammond, C., Eccles, A., Richins, M. T., & Qualter, P. (2022). Exploring the nature and variation of the stigma associated with loneliness. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 39(9), 2658–2679.

[5] Drawing on Barreto, M., van Breen, J., Victor, C., Hammond, C., Eccles, A., Richins, M. T., & Qualter, P. (2022). Exploring the nature and variation of the stigma associated with loneliness. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 39(9), 2658–2679.

Glossary and abbreviations

DCMS - The Department for Culture, Media and Sport.

Evidence review - A research method which locates and synthesises existing evidence on a particular topic or issue.

Focus group participants - Participants with little recent experience of loneliness who took part in focus groups (n=24).

Framework / Framework method - A method for extracting and analysing data, whereby each row represents one paper, and each column represents a research question or sub-question.

Intersectional approach - An intersectional approach recognises that different facets of a person’s identity ‘intersect’ to shape the lived experience of the individual.

Interviewees - Participants experiencing loneliness regularly who completed interviews and diary entries (n=40)

Loneliness - “A subjective, unwelcome feeling of lack or loss of companionship. It happens when we have a mismatch between the quantity and quality of social relationships that we have, and those that we want.”[1]

Rapid Evidence Assessment (REA) - A type of evidence review (see definition above) which seeks to understand the existing evidence on a particular topic within a short period of time.

Self-stigma - Feeling shame or embarrassment around a personal characteristic or experience and being inclined to conceal it from others.[2]

Social stigma - Negative attitudes or beliefs towards an individual or group, based on experiences or characteristics which are seen to distinguish them from other people (in this case, experiences of loneliness). This results in the person or group being devalued and/or suffering discrimination.[3],[4] This review explores actual and perceived social stigma.

Stigma - Covers both social and self-stigma.

Stakeholders - Professionals with experience tackling loneliness stigma who took part in interviews (n=6).

Qualitative research - The collection and analysis of non-numerical data (e.g., data from interviews).

[1] Drawing on Perlman, D. and Peplau, L. A. (1981) Toward a Social Psychology of Loneliness. In R. Gilmour & S. Duck (Eds.), Personal Relationships: 3. Relationships in Disorder (pp. 31-56). London.

[2] Drawing on Barreto, M., van Breen, J., Victor, C., Hammond, C., Eccles, A., Richins, M. T., & Qualter, P. (2022). Exploring the nature and variation of the stigma associated with loneliness. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 39(9), 2658–2679.

[3] Drawing on Link, B. & Phelan, J. (2001). Conceptualizing Stigma. Annu Rev Sociol, 27, 363–85.

[4] Drawing on Barreto, M., van Breen, J., Victor, C., Hammond, C., Eccles, A., Richins, M. T., & Qualter, P. (2022). Exploring the nature and variation of the stigma associated with loneliness. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 39(9), 2658–2679.

1. Introduction

1.1 Background

Long-term feelings of loneliness are associated with higher rates of mortality and poorer physical health outcomes.[1] Furthermore, loneliness can predict the onset of common mental disorders, such as depression and anxiety.[2],[3] The UK Government’s tackling loneliness strategy sets out the approach to tackling loneliness in England. The goals set out within this strategy include “reducing the stigma attached to loneliness so that people feel better equipped to talk about their social wellbeing” (pg. 9). However, as demonstrated through the Tackling Loneliness evidence review there are gaps in the evidence base around loneliness stigma.

In 2022, DCMS commissioned The National Centre for Social Research (NatCen) to undertake a Rapid Evidence Assessment (REA) of existing research on loneliness stigma (“the Loneliness Stigma evidence review”). The full report identified 36 relevant papers. Although evidence of self- and social stigma was found, national and international surveys indicated that social stigma may not be widespread. It was also demonstrated that self-stigma and the perception of social stigma can present barriers to discussing and overcoming loneliness. However, evidence gaps were identified around how loneliness stigma is experienced and how it can be tackled. The Loneliness Stigma evidence review accordingly recommended further research to explore the drivers of loneliness stigma across different population groups, along with how interventions could effectively tackle such stigma.

1.2 Research aims

To further develop the evidence-base around loneliness stigma, DCMS commissioned NatCen and RSM UK Consulting (RSM) to explore the following research questions:

-

How do different demographic groups understand and express loneliness?

-

What are the barriers that prevent people from taking actions to try and overcome their loneliness, and do these differ across demographic groups?

-

Do different demographic groups experience stigma around loneliness? If so, how?

-

How do you reduce the stigma experienced by people experiencing loneliness?

-

Could reducing stigma alleviate loneliness and, if so, in what ways?

-

How could a national campaign to reduce stigma be effective, and for whom?

1.3 Methods and participants

This research consisted of three parts: interviews with stakeholders, in-depth interviews and diaries with participants experiencing loneliness regularly and focus groups with participants with little or no recent experience of loneliness. For more details of the sample, methodological approach and ethical considerations, please see Appendix A.

Stakeholder interviews

Six interviews were conducted with stakeholders with professional experience in tackling loneliness stigma. These interviews provided expert insights into interventions and strategies to overcome loneliness stigma.

Interviews and diaries with interviewees

Forty in-depth interviews were conducted with participants who reported regular feelings of loneliness and loneliness stigma. Participants were sampled based on their life stage (young adults; parents of young children; middle-aged; retired). Secondary sampling criteria (e.g., ethnicity, disability and relationship status) were also monitored to ensure that the research captured a diverse range of experiences. Over two weeks prior to the interview, participants completed online diary entries documenting their connections with others, experiences of loneliness and whether they had discussed their feelings. Interviewers drew on entries to facilitate the discussion and generate richer insights into day-to-day experiences of loneliness.

Focus groups

Three focus groups, each with eight participants, were conducted to explore societal perspectives of loneliness in others. Participants reported little or no recent experience of loneliness. Each focus group contained participants from one age group (16-34; 35-64; 65+).

Analysis and interpretation of findings

Interviews and focus groups were transcribed and analysed using the Framework approach,[4] whereby each row represented one interview or focus group and each column represented a topic of relevance. Relevant information from each interview or focus group was written into the corresponding cell. This grouped information around each research question, enabling the research team to assess the relevant evidence. Findings have been integrated across the three work strands and are presented thematically.

This report does not provide numerical findings, since qualitative research cannot support numerical analysis. Instead, the qualitative findings provide in-depth insights into the diverse range of views and experiences of participants and verbatim quotes are used to illustrate these. Experiences of interviewees were informed by a range of factors, including demographics and life circumstances, which culminated in unique experiences for each individual. While this report comments on the impact of demographics and wider factors, this focuses on qualitative insights (i.e., how and why demographics impact experiences) rather than making quantitative claims that certain experiences are more or less common in different groups.

1.4 Structure

This report is divided into the following sections:

-

Chapter 2 explores expressions and understandings of loneliness

-

Chapter 3 discusses barriers to sharing and managing experiences of loneliness

-

Chapter 4 explores experiences of loneliness stigma. This Chapter also contains illustrations of how experiences of loneliness and loneliness stigma can be shaped by demographic factors

-

Chapter 5 makes recommendations for how stigma can be tackled and considers the likely impact of these interventions.

[1] Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., & Layton, J. B. (2010). Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS medicine, 7(7)

[2] Mann, F., Wang, J., Pearce, E., Ma, R., Schleif, M., Lloyd-Evans, B. and Johnson, S. (2021). Loneliness and the onset of new mental health problems in the general population: A systematic review. MedRxiv.

[3] Nuyen, J., Tuithof, M., de Graaf, R., Van Dorsselaer, S., Kleinjan, M. and Have, M.T. (2020). The bidirectional relationship between loneliness and common mental disorders in adults: findings from a longitudinal population-based cohort study. Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology, 55(10)

[4] Ritchie, J., Lewis, J., Nicholls, C.M. and Ormston, R. eds., 2013. Qualitative research practice: A guide for social science students and researchers. Sage.

2. Expressions and understandings of loneliness

This Chapter explores how different population groups understand and express loneliness by drawing on insights from interviewees (i.e., those experiencing loneliness regularly) and focus groups (i.e., those with little or no recent experience of loneliness).

2.1 Personal expressions of loneliness

This section explores how interviewees described their experience of loneliness and the factors driving it. Section 2.2 will then consider broader perceptions of loneliness, and how these perceptions align with lived experience.

2.1.1 The experience of loneliness

Interviewees’ experiences of loneliness were related to negative feelings about their quantity or quality of social connection. For some participants, feelings of loneliness were driven by having very little day-to-day connection with other people (e.g., not speaking to many other people daily). This caused consistent negative and unwelcome feelings such as isolation, a sense of loss and emptiness.

“I don’t have any family and I don’t have any close friends really, so I am a bit bereft of that type of family connection, and also they’ve [extended family and friends] got children and grandchildren, and they’ve got their own lives that I’m not connected with, really” – Interviewee (40-60 age group)

However, loneliness was also experienced by those with higher day-to-day levels of social connection, including those with strong relationships. In these cases, feelings of loneliness were driven by three factors:

- Physically spending time alone due to circumstances (rather than active choice). These feelings were experienced by interviewees who did not live with other adults, but were also triggered by doing activities alone which the interviewee would prefer to do with others. For some parents, this included time spent with small children but without other adults. These activities were specific to each individual and included entertainment outside the house (e.g., going to the cinema) and day-to-day chores. When physically spending time alone, participants explained that they missed companionship and the “little things”, such as the physical presence of another person.

“When I’ve done my night-time chores and I sit alone in my flat. The feelings of lack of companionship overwhelm me” – Diary entry (parent)

-

Feeling disconnected from others. In some cases, disconnection was driven by the interviewee feeling different from those around them. This led interviewees to feel that they were not understood or created a barrier to finding commonality or shared interests. For others, disconnection related to the quality or strength of their relationships. One interviewee described having only “surface level” relationships while others were unable to have meaningful conversations with family and friends. Feelings of disconnection could be experienced when interviewees were alone or spending time with others that they did not feel connected to.

-

Missing particular connections. Some participants felt that while they had meaningful relationships, particular connections were “missing” from their lives. This included particular relationships (e.g., a partner) and particular people (e.g., friends and family who lived far away).

As illustrated in section 2.1.2 below, these factors can be experienced alone or simultaneously.

2.1.2 Causes and drivers of loneliness

Interviewees attributed their feelings to different life experiences. As described below, they felt that these experiences led to loneliness by – directly or indirectly – reducing the quantity and/or quality of their connections.

Health and disability

Some participants felt that their experience of loneliness was attributable to physical or mental health conditions including disability, cancer, depression and anxiety. Older people tended to attribute their loneliness to physical health while younger people were more likely to discuss the impacts of their mental health.[1] One younger interviewee felt that mental health was a key driver of loneliness among their peer group. Health challenges and disability were felt to cause loneliness in the following ways:

-

Physical health barriers to social connection. In some cases, interviewees struggled to socialise due to their health condition or disability, which resulted in them spending time alone. Physical health challenges and pain made it difficult for interviewees to leave the house or socialise face-to-face. In some cases, interviewees in the 40-60 and 65+ age groups spoke about how poor health prevented them engaging in activities which had previously been important in their social life (e.g., sports clubs). Some people living with health conditions or disabilities had experienced very difficult periods of loneliness at times when they were physically prevented from seeing others (e.g., during hospital stays).

-

Emotional barriers to social connection. Interviewees living with a health condition or disability also felt that their experiences had led to emotional barriers to connecting with others. Some felt that poor mental health was a barrier to connecting with others because they found socialising difficult, particularly in times of low mood or heightened anxiety. Others described how physical health conditions (e.g., cancer) caused them to lose confidence or emotionally withdraw from friends and family. In some cases, the COVID-19 pandemic had prompted or exacerbated mental and physical health anxieties which continued to drive worries about socialising. Feelings of disconnection could also arise for interviewees with a health condition or disability due to a lack of shared experience. For example, an interviewee living with a disability could not do the “normal stuff” that his friends could (e.g., playing football) and had experiences of hospitalisation that his friends could not relate to. Some interviewees with a health condition or disability highlighted the role of others in creating or perpetuating these emotional barriers to connection. For example, one interviewee attributed their “fear of rejection” to first-hand experiences of stigmatising views around disability. However, others focused on their own actions and mindset, such as whether they took proactive steps to socialise and were open to new connections. In some cases, this led to interviewees feeling accountable for their experiences of loneliness.

“It’s like a rejection type thing. I think it’s just me, got this mindset that thinks that other people, they’re always going to be busy and not to bother or trouble them type thing. Yes, I think it’s down to me really.” – Interviewee (40-60 age group)

Life circumstances and experiences

Some experiences of loneliness were caused by life events and commitments which reduced social connection. This included:

-

Retirement, unemployment or other working changes (e.g., working from home) that reduced day-to-day social connection.

-

Parenting commitments that reduced time for socialising or prompted lifestyle changes, which resulted in interviewees spending less time with other adults.

-

Death of a partner or other relative, with interviewees missing the close connection and companionship they previously enjoyed with that person. One interviewee who had lost his wife explained “it’s been a big like culture change of doing everything together, then, all of a sudden, you’re on your own”.

-

Other changes to relationships, such as friends or family moving away. Similarly, divorce or relationship break- down led to some interviewees feeling lonely due to spending more time alone. However, these interviewees also tended to describe feelings of loneliness or disconnection within their relationship, with some describing these were worse than the feelings they experienced post-break up.

The life events discussed above had immediate impacts on interviewees’ social connections. However, in some cases there were also long-term impacts on loneliness. This could occur when experiences (e.g., bereavement, divorce or working away from home) forced interviewees into a routine of spending time alone, which then felt hard to break.

As well as impacting the quantity of social connection, life events and circumstances could prompt feelings of disconnection from others who did not share the same experiences. This was due to interviewees not feeling understood or wanting empathy (even if those around were supporting and sympathetic).

“Motherhood is a very lonely thing, especially if you’re going through struggles…It was a really lonely time, because no one was going through quite what I was around me. There’s only so much people can sympathise.” – Interviewee (parent)

Non-working interviewees also experienced disconnection because they did not have experiences of work or socialising to contribute to discussions with others. One interviewee felt that working “gives you something to talk about”. Similarly, parenthood caused some interviewees to feel a reduced level of connection with their partners because the focus of the relationship had changed.

When discussing these types of life events, interviewees had mixed perspectives on whether their experience of loneliness was driven by their actions, by the actions of others or by circumstance (e.g., getting older, family moving away). Some interviewees described the impact of their own actions or choices in reducing their level of social contact. For example, one retired interviewee felt that changes to their self-image, which accompanied retirement, caused them to withdraw from others. Another experience was that of parents with little time to socialise, who described how they took decisions to prioritise spending time with family over socialising with others.

“I suffer from a lot of mum guilt…So I exclude myself from social activities, and actually putting myself out there, and taking the time to actually meet people and be in networks where I’m able to establish relationships, friendships, any kind of companionship that would be open to me, had I not had the guilt.” – Interviewee (parent)

However, some interviewees had considered the role of others in their experiences of loneliness. For example, some people who had been through a life change (e.g., serious illness, retirement or parenthood) felt that those around them made fewer efforts to connect with them than before.

“You notice that people don’t bother inviting you anymore. You then get that little bit older, then they might have children, so then they’re focused on that. That again dwindles your circle down… It’s just what happens.” – Interviewee (parent)

2.2 Societal understandings of loneliness

This section explores how loneliness is understood from a societal perspective, drawing on findings from focus groups (i.e., those with no/little recent experience of loneliness) and interviews with people experiencing loneliness.

2.2.1 Understandings of the experience of loneliness

Across the interviews and focus groups, there were mixed perceptions about how loneliness (outside personal experiences) related to quantity and/or quality of social connection. Some participants initially perceived that loneliness only related to the quantity of connections. For example, the word ‘loneliness’ prompted some interviewees and focus group participants to think about images of social isolation or a person with few connections.

“I think for me, [the image of loneliness is] no friends or family and no contact with anybody that they could have conversation with or contact.” – Focus group participant (65+ age group)

However, interviewees and focus group participants who reflected on these views tended to ultimately perceive that experiences of loneliness could be driven by negative feelings about both quantity and quality of connections.

Some focus group participants perceived that loneliness was “less about” the quantity of connections, suggesting that someone could be physically surrounded by others and/or have long-term relationships but still experience loneliness if they felt disconnected or if their needs were not being met. These participants did not disagree that some experiences of loneliness were caused by a low quantity of social contact. Instead, their perspective was that quality of connection was a more useful measure to understand loneliness because it captured a wider range of experiences. Similar comments were made by interviewees, particularly those with higher levels of day-to-day connection.

There were mixed understandings as to which factors were important in distinguishing severity of loneliness. The Government definition gives equal weight to experiences of loneliness driven by negative feelings about quality or quantity of social connection. However, some interviewees believed that severity of loneliness was linked to the level of social isolation (i.e., quantity of social connection). One perspective was that “really serious loneliness” was being totally isolated and alone. The impact of this was that although interviewees regularly felt lonely, some did not believe that they could experience the most serious type of loneliness because they had friends and family. Conversely, some interviewees with more social contact felt that others did not understand how serious feelings of loneliness in their situation could be. An interviewee in the 16-30 age group stressed that loneliness was a really serious issue among young people despite some perceptions to the contrary, and that young people really “feel it” – this suggests that it is more important to understand how the experience impacts the person, rather than how it appears from the outside. Altogether, interviewees who discussed the severity of loneliness tended to relate this to the intensity of their current experience, rather than the length of time they had felt this way. When thinking about imagery of loneliness, focus group participants (with little/no recent experience of loneliness) found it difficult to distinguish between long-term and transient loneliness, given the variety of factors (e.g., life events and wider circumstances) which could lead to loneliness. However (as explained below) some focus group participants perceived that certain factors (e.g., old age and low confidence) could lead to more frequent feelings of loneliness.

2.2.2 Causes and drivers of loneliness

Understandings of the experience of loneliness across the life course

Interviewees and focus group participants felt that everyone is likely to experience some form of loneliness at some point in their lives. It was perceived that some experience of loneliness is almost inevitable at some point in the life course due to the connection with certain life events (e.g., changing jobs, divorce or widowhood). As explained above, focus groups did not generally distinguish particular experiences as long term or transient loneliness, perceiving that experiences of loneliness were likely to vary depending on individual factors.

“I think there’s probably people that are more prone to it than others, I’d have thought. Everyone’s got other things going on in their lives and everyone processes things in different ways, so I’d imagine there’s probably people that are more prone to feeling lonely or depressed, or things like that than others. I’d be surprised if there was anyone that ever could say that they’ve never felt lonely.” – Focus group participant (16-34 age group)

On the basis of personal experience, some interviewees felt that loneliness within certain groups was harder for society to understand. For example, both younger people and new parents felt that loneliness within their peer group was dismissed (or not recognised at all) due to assumptions that their needs were met by those around them. One interviewee in the 16-30 age group also questioned how common loneliness was in their peer group due to a perception that most people spent a lot of time socialising. In comparison, interviewees felt that loneliness among older people was well recognised, particularly in the media.

“They expect you to be bubbly…You’re at uni, you’re going out clubbing, you’re drinking, you’ve got all your friends from school…I do think they dismiss it [loneliness] because…you can do all that.” – Interviewee (16-30 age group)

One perspective from an older interviewee was that younger people may not understand their experience of loneliness. This appeared to relate to a perception held by the interviewee that younger people are less likely to face the same barriers to social connection as older people (e.g., living alone or physical health barriers) and therefore would not be able to understand why loneliness could not be overcome.

While focus groups recognised that loneliness could be experienced at any age, there was a common perception (contrary to the Government definition of loneliness) that older people were susceptible to a more severe or frequent experience of loneliness, due to being socially isolated and not having distractions to remove them from the feelings.

“My old neighbour…she’s not really going to change the way that she feels loneliness-wise. She may have very short periods where she’s reading or she’s doing something, but I think those are very few and far between. Whereas I think children or young adults, they have to have some sort of interaction with adults or schools or whatever, so they are getting some form of contact. I think that an elderly group is going to feel that loneliness more than a child or a young adult.” – Focus group participant (65+ age group)

However, perceptions were often stated in terms such as “the automatic thing to say is it’s older people”. This image was questioned by participants, who reflected that other age groups can experience loneliness or highlighted examples of retired friends or family who “love every minute of it”. However, despite this self-reflection, the regularity with which this group was mentioned indicates that society continues to view loneliness as being inextricably linked with old age.

Interviewees and focus group participants drew on personal experiences when discussing how they understood loneliness. Focus group participants were sampled on the basis that they had not recently experienced regular feelings of loneliness. However, some had felt lonely themselves at some point, had friends or family who had experienced loneliness or had encountered loneliness in the course of their work.[2] Focus group participants recounted specific examples in their lives, such as a friend who could not leave the house, an elderly neighbour or young people they had worked with. Older focus group participants also spoke about their experiences during the life course, which guided their views on loneliness among younger age groups. Interviewees and focus group participants also felt that the media, including TV, film and books, may have influenced some of their views. While some felt that media focus tended towards older people living alone - “it’s shown as elderly people that live alone-type situation” - coverage around the COVID-19 pandemic was felt to have highlighted broader experiences of loneliness.

Understanding of causes of loneliness

As explained in section 2.1, interviewees tended to focus on individual causes when describing their own experiences of loneliness (e.g., health conditions and life experiences). Within each focus group, participants (with little/no recent experience of loneliness) recognised that these experiences could drive feelings of loneliness, referencing similar examples of life events leading to feelings of loneliness for friends or loved ones. In this respect, focus group participants did not attribute feelings of loneliness to being within the control of the individual or place blame for loneliness on those experiencing it.

Focus group participants perceived that certain traits (e.g., confidence and resilience) may drive people to proactively seek social connection. Some interviewees also felt that loneliness could be caused by the actions of the individual. While some interviewees only raised this perspective in the context of their own experiences (see section 2.1.2 for findings about self-blame), others felt that other people isolated themselves. In some cases, it was acknowledged that self-isolation was driven by circumstantial factors (e.g., old age and health problems). However, there was also a perception that some people could do more to seek out connection.

“I would say that certain people do feel lonely quite often. I think confidence has a big impact…I’ve known people in the past and now who aren’t very confident in themselves, so they isolate themselves away, or don’t know how to get involved, which, obviously, in itself creates being alone and not in the mix with people, which I would class as being lonely.” – Focus group participant (35-64 age group)

“I think you can control it. You can make yourself isolated and lonely. You’ve got to put effort in yourself, and if you don’t, there’s no guarantee that other people will, so I think you can. Certain people can create their own loneliness where they cut themselves off, but then I feel for me, my loneliness has gone how things have changed as my friends and everyone have got older, families, grandchildren.” – Interviewee (40-60 age group)

When considering the causes of loneliness in society, both focus group participants and interviewees attributed loneliness to a range of societal factors, including social media and virtual communication.

Younger focus group participants (age 16-34) suggested that social media use could lead to feelings of “not fitting in” or being “left out”. Younger interviewees confirmed that social media exacerbated their feelings of loneliness, by causing them to compare themselves negatively to others they saw online.

“I do think social media has a really big influence on it. I think it’s very easy to post things and then, as a viewer, watching this, thinking, how do these people get to - these people have got loads of friends, and they’re always out and about, and they have money to do these things. Why can’t I? That can make you feel quite lonely and isolated.” – Interviewee (16-30 age group)

Focus group participants (with little/no recent experience of loneliness) also perceived that loneliness was driven by a lack of physical contact, caused by the increased use of virtual communication methods, such as social media or Zoom (in work contexts). These participants suggested that virtual communications do not satisfy the need for human connection and promote less meaningful interactions. To some extent, this perspective was reflected in the first-hand experiences of interviewees. For example, some older interviewees felt that phone calls and face-to-face contact had decreased, being replaced by text messages, which they felt exacerbated experiences of loneliness. Younger and older interviewees who spoke about the impact of virtual communication on their own experiences discussed this as a societal issue and an external driver for loneliness, rather than something they could control. However, there was a perception (particularly among older focus group participants and interviewees) that some younger people felt lonely because they prioritised screen time or social media over face-to-face or deeper connections. For example, some older focus group participants (age 65+) perceived that many young people are more concerned with how many “Facebook friends” they have, rather than building closer relationships with their family and friends. It should be noted that this suggestion was not supported by data collected from young interviewees. While some young interviewees acknowledged social media as a societal driver of their loneliness (see above), they did not suggest that their lonely feelings resulted from a choice to prioritise social media over face-to-face connection. Therefore, this can be considered (see Chapter 4) as a potentially stigmatising view of loneliness.

“I think social media plays a very, very big part in loneliness. Maybe I’m wrong in saying that, but that’s the feeling I get from people who are on the screens all the time. It’s okay being on the screens if you’re doing something productive, but that’s just my feeling about the internet.” – Focus group participant (65+ age group)

It is important to note that some interviewees had positive experiences of using social media to overcome feelings of loneliness. This included experiences of joining online groups or talking to friends and family who they struggled to see face-to-face. While younger and older interviewees highlighted the importance of face-to-face contact, virtual communication provided a way to connect when face-to-face connection was not possible.

Some focus group participants and interviewees perceived that loneliness may have increased due to a decline in community and neighbourly relations. It was felt that people were too busy and “wrapped up in their own worlds”, therefore less likely to check in on those around them. In particular, the older focus group (age 65+) perceived that both families and communities could do more to support people who may be at risk of loneliness.

“I think family could help a lot more than they do. I think the trouble is they’re very busy these days.” – Focus group participant (65+ age group)

Some interviewees recounted experiences of others not reaching out to them during difficult or transitional periods in their lives. However, others spoke positively of friends and family. While some interviewees felt they would like to see family more, they did not blame their experiences on those around them.

[1] This finding should not be assumed to be representative of the wider population (given the qualitative methodology and sampling). However, it can help guide interpretation of the findings below.

[2] As research has demonstrated, it is likely that most people experience some form of loneliness at some point in their lives. Therefore, it is likely that any composition of focus group will have experiences of loneliness (even if these are not chronic experiences).

3. Barriers to managing and overcoming feelings of loneliness

This Chapter explores actions taken to manage and overcome loneliness, along with barriers to taking these actions. This primarily draws on views from interviewees (i.e., those experiencing loneliness regularly), as well as with some insights from stakeholders and focus groups (i.e., those with little/no recent experience of loneliness).

3.1 Overview of approaches to managing and overcoming feelings of loneliness

The Loneliness Stigma evidence review found that stigma prevents people from talking about loneliness and accessing support. However, the review also identified wider barriers to talking about loneliness which may or may not be linked to stigma. It was suggested that further research could explore the range of barriers which prevent those experiencing loneliness from accessing support, and the impact of tackling stigma in this context.

Interviewees shared examples of actions they had taken (or wanted to take) to overcome feelings of loneliness. However, others felt that their experiences were not something they could or should “overcome”. This was particularly the case for those who attributed their loneliness to circumstances, such as caring or work commitments, that they could not “fix”. Therefore, this Chapter will discuss barriers to overcoming and managing feelings of loneliness. While there was some consistency across interviewees, some factors driving these barriers related to demographics or wider life experiences. These factors are set out throughout this Chapter. Please also see Chapter 4 for illustrations of how lived experiences are shaped by gender, age and health.

3.2 Sharing feelings of loneliness

While some interviewees had shared their feelings of loneliness with other people, others had little experience of talking about how they felt. Interviewees typically shared lonely feelings with those close to them or where there was trust and/or mutual understanding. As discussed in Chapter 2, some interviewees attributed loneliness to specific life experiences. These individuals valued talking to others with similar experiences who could understand their feelings in context. For instance, some mothers felt able to share their feelings with “mum friends”, whereas others felt comfortable sharing experiences at groups for people with similar health conditions. In some cases, interviewees had sought support from professionals about feelings of loneliness, including GPs and Samaritans. This action was taken when feelings of loneliness had become severe or where interviewees did not feel comfortable talking to those close to them.

3.3 Barriers to sharing feelings of loneliness

Interviewees identified several barriers to sharing feelings of loneliness, which are set out below (please see Chapter 4 for a discussion of the role of stigma in these barriers):

Past responses to sharing feelings of loneliness

Some interviewees who shared their feelings reported positive responses. This included empathy and appropriate action being taken, such as friends and family visiting or facilitating opportunities to socialise. Knowing that others cared made participants feel more able to share feelings of loneliness going forward. This was particularly the case when others were able to empathise with their experience.

“I feel like then I don’t feel stupid for the way I feel sometimes because other people feel like that as well, it’s not just me.” – Interviewee (parent)

However, not all well-intentioned reactions left interviewees feeling comfortable to share future experiences of loneliness. Some interviewees received unwanted advice, including suggestions to “go out more” or take other steps to socialise (e.g., join clubs). In cases where the interviewee did not take the recommended action, because they were unable or did not want to, they felt less comfortable sharing with these people in future. This was driven by a fear that friends and family might be frustrated that their earlier advice had seemingly been ignored. Other interviewees felt patronised by advice they received from professionals (e.g., counsellors), who suggested they take up unsuitable activities to leave the house. Another unhelpful response involved others trying to distract interviewees from how they were feeling. While this response was well-intentioned, some interviewees would have preferred space to discuss their feelings.

“Some people when you say, ‘Oh, I’m feeling a bit lonely,’ they just go, ‘Oh, make yourself busy then. Make plans. Have you tried messaging someone? Have you tried ringing someone?… but it’s not always as simple as just ringing someone or just making yourself busy.” – Interviewee (16-30 age group)

“I just sometimes might want to vent, and I just think I don’t want people to try and start problem-solving for me.” – Interviewee (parent and 16-30 age group)

Some interviewees received responses which were felt to be less well-meaning, including “shrugging off” or “glossing over” loneliness. Other reactions implied blame. For example, one parent was told that their experience of loneliness was a result of their life choices. After sharing feelings, some interviewees received no “follow-up” offers of support or checking in. Other interviewees were cautious about sharing their experience because they had experienced situations where their feelings – or the feelings of others – had become “gossip”.

Fear of how others might react

As well as reactions already received, anticipated or feared reactions were a barrier to sharing feelings of loneliness. Interviewees worried that sharing experiences of loneliness could be perceived negatively as “moaning” or being “miserable”. Interviewees feared that expressing negativity would cause others to view them as “sad” or “boring” and distance themselves. Instead, interviewees wanted to view themselves, and have others view them, in a more positive light. This concern was particularly relevant for those experiencing wider challenges (e.g., health issues), who worried about sounding like a “broken record”. Interviewees struggled to pinpoint the cause of their fears and spoke about their worries being assumptions rather than based on the attitudes or actions of others.

Interviewees also feared judgement from others, particularly those who did not share similar life experiences. Some mothers feared being judged as ungrateful and avoided discussing their experiences so as not to appear that they did not enjoy motherhood. Other interviewees were concerned that people would blame them for their experience. In some cases this stemmed from perceptions about societal assumptions, while others were unsure where this fear came from. Another view was that others without shared experiences (e.g., parenting) would not judge, but their lack of understanding would render them unable to offer an appropriate response.

“I wouldn’t tell my friends as they just don’t get it. They have never been in this position so don’t understand.” – Interviewee (40-60 age group)

Fear of pity was also a barrier to sharing feelings. Interviewees did not want to feel that people were engaging with them just because they felt sorry for them, but because they enjoyed their company. This feeling was expressed across all age groups, but was particularly key for older adults in respect of their grown-up children. This concern was often cited along with a fear of burdening others (see below) but specifically related to how the interviewee was perceived – by themselves and others – rather than the impact on others.

Fear of burdening others

Fear of burdening others prevented interviewees from sharing feelings of loneliness with certain people. For example, some older people refrained from sharing with their adult children to avoid worrying them. A similar explanation was provided by those whose close friends and family had “a lot on their plate”, such as physical or mental health needs. In these cases, interviewees felt that they had to remain emotionally “strong” for others, which entailed not sharing their own struggles. For some, wanting to avoid burdening others was explicitly linked to their prescribed role as dictated by gender and/or culture. Parents felt that their caring role meant they were not meant to seek support from their children. One mother did not feel comfortable sharing feelings of loneliness due to a cultural expectation of strength, related to her gender and caring role – “in my culture they just say that women just have to stay strong and carry on with whatever they are feeling and things will get better”.[1] While fears about burdening others were influenced by societal expectations, interviewees did not feel that these feelings were driven by specific first-hand experiences. Interviewees acknowledged that they did not personally feel burdened when others had opened up to them about their struggles. However, the fear of being a burden remained a strong barrier to instigating conversations about experiences of loneliness.

“Everyone has been really helpful, but again I guess it’s my mindset where I think that I’m loading them up with my problems all the time and dragging them… I think it’s just me that thinks that really.” – Interviewee (40-60 age group)

Lack of means or opportunity to discuss loneliness

Some interviewees had not shared experiences of loneliness because they did not feel able to express their feelings effectively. Some interviewees described themselves in terms such as “private” and explained that sharing any personal matter did not come naturally.

“I just think I struggle with saying my emotions out loud to other people and communicating them the way I mean them.” – Interviewee (16-30 age group)

While these experiences were expressed across all age groups, some older interviewees felt that their generation did not share personal feelings. In other cases, interviewees whose experience of loneliness was tied to a life experience (e.g., bereavement) explained that discussing their feelings would raise wider experiences that they did not feel able to talk about. In some cases, interviewees also struggled to express what support they wanted from others or could not foresee a response that could “fix” their feelings. Stakeholders highlighted that older people may be more likely to hide their feelings due to a societal perspective that loneliness is particularly common among this generation (as highlighted in Chapter 2). In the experience of stakeholders, this perception prevented some older people from seeking support because they assumed that loneliness should be accepted as a consequence of ageing.

Other interviewees wanted to share their experiences, but had not had the opportunity to do so. This tended to be because the interviewee did not feel comfortable initiating the conversation and it was never raised by others. Some felt that others feared upsetting them, particularly where feelings of loneliness stemmed from a difficult life experience, such as the death of a partner. In other cases, it was felt that society generally lacks the language and understanding to have conversations about loneliness.

Focus group participants (with little/no recent experience of loneliness) supported the above, whereby some felt unsure how to best initiate and manage discussions about loneliness. Despite wanting to provide support, some participants felt that concerns about upsetting or embarrassing others prevented them from raising the topic. These concerns were driven by a number of factors. Some participants felt that they lacked the understanding and language to sensitively find out if someone felt lonely and create an environment where they could discuss their feelings. The biggest challenge for focus group participants appeared to be asking direct questions around loneliness. In contrast, participants felt they would be more comfortable providing broader support (e.g., inviting others to socialise). In some cases, participants linked their discomfort to not having personally experienced loneliness, leading to concerns around providing the right comfort and/or solutions. Participants also worried about making assumptions that others feel lonely, particularly where they had a higher level of social connection than the person concerned.

“I wouldn’t really know how to go about getting information out of someone about loneliness and getting them to open up and talk about it. I wouldn’t know how to elicit that information without perhaps upsetting or embarrassing them.” – Focus group participant (65+ age group)

“I don’t even think asking someone if they’re lonely is even really in our language.” – Focus group participant (35-64 age group)

Despite the challenges raised, some focus group participants felt comfortable discussing loneliness and had done so with family, friends, and neighbours who felt lonely. For these participants, a key enabler was having professionally developed communication skills (e.g., through customer/service user facing roles). In some cases, this included professional experience in conducting sensitive conversations (e.g., working in schools or the emergency services).

3.4 Other actions taken to manage or overcome loneliness

Interviewees reported several strategies for managing loneliness in addition to, or instead of, talking about their feelings with others. This included actions to increase their level of social interaction, for example by joining groups to meet others with shared interests. While these activities provide opportunities for relationships to develop, thereby improving social connection, they could also provide a welcome distraction from feelings of loneliness. Similarly, interviewees described focusing time on their own interests (e.g., attending to an allotment, knitting or playing music) as a “release” from loneliness. Rather than increasing their level of social connection, some interviewees wanted to change how they felt by becoming more content in their own company - this included taking steps to do enjoyable activities alone (e.g., hobbies or holidays).

Barriers

Interviewees identified a number of barriers to taking these actions, which often overlapped with causes of loneliness (see Chapter 2):

-

Lack of time. Practical considerations, such as work and caring responsibilities, meant that some interviewees had no time to take actions to manage or overcome feelings of loneliness. This was particularly true for interviewees in the 16-30; parents and 40-60 age groups who were in employment. The combination of work and childcare constraints also posed a barrier for parents.

-

Financial barriers. Financial concerns were a practical barrier to managing loneliness. Some interviewees could not afford to socialise as much as they would like, or did not have time to because they have had to increase their working hours to ensure their financial security. Some made references to the recent rise in the cost of living as exacerbating this barrier.

-

Exhaustion. A combination of the factors outlined above led some interviewees to feeling tired consistently. This prevented them from doing activities that helped manage feelings of loneliness when they arose, such as socialising or playing video games.

-

Emotional barriers. Some interviewees felt that emotional barriers, such as low self-confidence or fear of rejection, prevented them from taking action to connect with others. Some felt more comfortable being alone when feeling lonely. Feelings of low self-esteem led some to feel like they did not have anything to offer those around them, which made them less confident in reaching out to others. To some extent, these emotional barriers were widespread across interviewees. However, in some cases interviewees felt these were driven by mental health challenges or wider experiences (see Chapter 2 for more details).

“When I feel lonely, as well, my self-esteem can tell me to just stay on my own.” – Interviewee (40-60 age group)

- Availability and accessibility of options. Some interviewees had looked for opportunities to make connections, but struggled to find anything of interest in their local area. In some cases, interviewees assumed that this was because their area was rural or “quiet”. Others had considered attending local events or groups, but found travelling to the event to be tiring or anxiety-inducing. In some cases, labelling or first-hand experience of groups had stopped interviewees attending. For example, one interviewee in the age 65+ group who did not feel “older” avoided groups targeted at “older people”, perceiving them as irrelevant and uninteresting. One parent also described how they did not want to join local mother and baby groups, because they felt that the groups were exclusionary to mothers with lower incomes.

[1] The culture of the interviewee is not provided here because this finding represents one experience and should not be taken to be common across that culture. However, when understood with wider findings in this paragraph it does indicate that cultural expectations can drive barriers to sharing feelings of loneliness.

4. Experiences of loneliness

This Chapter draws the findings from Chapters 2 and 3 and wider insights from stakeholders, interviewees (i.e.,those experiencing loneliness regularly) and focus group participants (i.e.,those with little/no recent experience of loneliness) to examine how loneliness stigma is understood and experienced.

4.1 Defining loneliness stigma

The definitions of stigma used in this research were developed through the Loneliness Stigma evidence review. This section discusses the findings from this research in the context of the literature identified in this review.

-

Social stigma: Negative attitudes or beliefs towards an individual or group, based on experiences or characteristics which are seen to distinguish them from other people (in this case, experiences of loneliness). This results in the person or group being devalued and/or suffering discrimination.[1],[2]

-

Self-stigma: Feeling shame around a personal characteristic or experience and being inclined to conceal it from others.[3]

Stakeholders defined stigma in similar terms, and were guided by the literature when expressing their views. However, wider reflections from interviewees and stakeholders could broaden the definition of social stigma in future research. Both groups spoke more broadly about stigma as a general negativity around loneliness. Some interviewees struggled to pinpoint specific attitudes or beliefs but still felt this negativity, with one describing stigma as “like a negative thing that’s stuck onto it [loneliness]”.

4.2 Experiences and perceptions of social stigma

Actual social stigma

The Loneliness Stigma evidence review found that some people do hold stigmatising views of loneliness. However, these are not universal and tend to be grounded in stereotypes of people who feel lonely (e.g., assumptions that people are responsible for their experience). It was suggested that further research could explore the extent of societal assumptions around loneliness and whether (and how) people who feel lonely have experienced stigmatising views from others.

Exploring actual social stigma involved examining attitudes towards those who experience loneliness, to understand the extent of negative opinions. This report has paid particular attention to whether opinions ascribe blame to those who feel lonely, as this emerged as a driving factor of social stigma in the Loneliness Stigma evidence review.

As discussed in Chapter 3, some interviewees had experienced negative or unhelpful responses when sharing feelings of loneliness. In some cases, these responses could be considered stigmatising (in line with the definitions used in research), for instance where jokes were made which portrayed the interviewee in a negative light or comments were made that loneliness was caused by their own life choices. One interviewee in the 16-30 age group spoke of first-hand experiences of stigmatising views during conversations at school, whereby students linked loneliness with social isolation (i.e.,someone without friends). In this situation, the interviewee felt that the tone of the discussion was that “there’s got to be something wrong with you”. However, many responses that interviewees considered unhelpful were not necessarily stigmatising or suggestive of negative beliefs around loneliness. For example, reactions such as “glossing over” experiences of loneliness or offering oversimplified solutions may be driven by the types of issues discussed in Chapters 2 and 3 rather than negative perceptions of those experiencing loneliness. This could include perceptions that more “serious” loneliness tends to impact older people and/or the confidant not feeling confident discussing loneliness.

Focus group participants generally did not discuss views of loneliness which were explicitly negative or blame those experiencing loneliness. This related to a strong view that feelings of loneliness are a normal part of life, and an understanding that these can be driven by a wide variety of life events and circumstances. As explained in Chapter 2, some focus group participants were informed by their own personal experiences of loneliness and experiences of loneliness among friends and family.

Chapter 2 described some perceptions among focus group participants and interviewees that loneliness could be linked to individual factors such as a lack of confidence, resilience and self-isolation.

“I would say that certain people do feel lonely quite often. I think confidence has a big impact…I’ve known people in the past and now who aren’t very confident in themselves, so they isolate themselves away, or don’t know how to get involved, which, obviously, in itself creates being alone and not in the mix with people, which I would class as being lonely.” – Focus group participant (35-64 age group)

For the most part, the degree to which these views are stigmatising is debatable. For example, one focus group perception was that loneliness could be attributed to individual factors such as low confidence and resilience. It was also perceived that some people self-isolate due to various circumstantial reasons (e.g., ill-health). However, these participants did not speak negatively about people experiencing loneliness or make assumptions that factors such as low self-confidence were controllable or should be viewed as a failing.[4] It is also notable that (as set out in Chapter 2) interviewees described their experiences of loneliness using similar language around self-confidence and self-isolation. However, other perceptions (from both interviewees and focus group participants) that placed a certain degree of responsibility on those experiencing loneliness could be seen as more stigmatising. In particular, there was a perception among older interviewees and focus group participants that young people may experience loneliness because they prioritise virtual, less meaningful connections (e.g., ‘Facebook friends’) above more meaningful relationships. Some interviewees and focus group participants also used stigmatising language around self-isolation (e.g., “certain people can create their own loneliness where they cut themselves off”).

When discussing imagery of loneliness, the first reaction of some focus group participants was to think of people experiencing loneliness as appearing in a certain way (examples included thinking of someone who was “sad” or thinking of an isolated older person). However, as the discussion in each group progressed, it was recognised that people experiencing loneliness did not fall within one group or image. Interviewees and focus group participants were open to reflecting on their views and proactively questioned some of the more “stereotypical” views that they presented (e.g., loneliness being common among older people).

Perceived social stigma

The Loneliness Stigma evidence review found that some people who feel lonely spoke directly about a social stigma, however stigma was spoken about in a general sense with no specific examples of social stigma provided. Other people experiencing loneliness described fears of being judged or rejected. While these people did not speak directly about loneliness stigma, their views indicated a perception of such stigma. However, in the BBC Loneliness Experiment, the average participant (including those who did and did not experience loneliness) did not perceive much social stigma in the community.[5] It was suggested that further research could explore perceptions of social stigma to better understand the nature and impacts of these perceptions.

Exploring perceived social stigma involved examining whether people who feel lonely perceive that others hold negative opinions about loneliness. Some interviewees (who had and had not experienced stigmatising views) perceived that there was a social stigma around loneliness. While some used this term, others spoke of expectations that if they shared feelings of loneliness, others might think negatively of them. For example, interviewees worried about being seen as “sad”, “boring” or “weak”, or being blamed for their experience. In some cases, these fears aligned with the interviewee’s experience of self-stigma (i.e.,feeling internally that their loneliness was a sign of weakness). However, other interviewees did not hold these negative views about their own experiences but felt that others would.

“Yes, sad, get out and get a life, basically! That’s probably what they’d be thinking.” – Interview participant (40-60 age group)

Some interviewees felt that this perceived stigma was driven by a lack of understanding about who experiences loneliness and what causes it. This was particularly the case for interviewees who felt that their experience of loneliness was not well recognised. In particular, these interviewees felt that they may be blamed because of assumptions that these feelings are due to their own actions. On the contrary (as shown in Chapter 2) loneliness is driven by a variety of life circumstances and experiences which can impact anyone. While concerns about blame were present across all age groups, some younger people felt that – because of their age and circumstances – others must assume that they had ample opportunity to socialise if they wanted to. One interviewee linked these concerns to a broader feeling that society views those who spend time alone in a negative light, particularly when this is felt to be by choice.