Research about connecting with others via the local physical and social environment

Published 7 January 2025

Applies to England

This research was commissioned under the 2022 to 2024 Sunak Conservative government

Glossary

Area deprivation - The extent to which an area is deprived based on the availability of resources.

Absolute diversity - The likelihood that any two people randomly chosen from a given community or organisation will belong to the same social group. [footnote 1]

Anti-social behaviour - Behaviour by a person which causes, or is likely to cause, harassment, alarm, or distress to persons not of the same household. [footnote 2]

Blue space - Outdoor environments, which can be either natural or manmade, which prominently feature water and are accessible to people. Examples are rivers, lakes, the sea, marinas, and canals. [footnote 3]

Bumping spaces - Places where people bump into each other, either intentionally or unintentionally, such as communal spaces and gathering places.

Chronic loneliness - Defined as those who feel lonely (see loneliness below) often or always.

DCMS - The Department for Culture, Media, and Sport.

Demographic Diversity - The similarities or differences of people within a community.

Demographic factors - Personal characteristics, such as gender and age.

Digital exclusion - Where a section of the population has unequal access and capacity to use digital technologies that are essential to fully participate in society.

Focus group - A facilitated group interaction which allows qualitative data collection.

Framework / Framework method - A method for extracting and analysing data, whereby each row represents one interview or focus group, and each column represents a research question or sub-question.

Green space - Natural spaces which are accessible to the general public, including specific local gardens, parks, nature reserves, or countryside (e.g., woodland or farmlands).

Group representation - Representation of people with similar demographic characteristics within a population. [footnote 4]

Hierarchy of needs - A psychological theory of motivation which is based on different levels of need. [footnote 5]

Housing tenure - The legal status under which people have the right to occupy their accommodation. [footnote 6]

Indices of deprivation - The official measure of relative deprivation in England across seven distinct domains of deprivation which are combined and weighted to calculate the Index of Multiple Deprivation 2019. [footnote 7]

Loneliness - A subjective, unwelcome feeling of lack or loss of companionship. It happens when we have a mismatch between the quantity and quality of social relationships that we have, and those that we want. [footnote 8]

Lower Layer Super Output Areas - Areas of between 400 to 1,200 households (or 1,000 to 3,000 persons) made up of around four to five Output Areas, which are the smallest geographical areas used for census statistics. [footnote 9]

Marginalisation - The treatment of a person or group as insignificant or peripheral.

MHCLG - Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government

Neoliberalism - A political approach that favours free-market capitalism, deregulation, and reduction in government spending. [footnote 10]

Physical environment - Refers to how the places where we live, live, study, work, and engage in leisure activities are built and connected to each other. [footnote 11] For example, green spaces, housing, and transport.

Purposive sampling - Sampling which is not based on probability and people included are selected based on characteristics that they possess.

Qualitative research and data - Research methods which gather non-numerical data, such as data from interviews.

Rural area - An area which is sparsely populated (less than 10,000 resident population). [footnote 12]

Semi-urban area - An area which has a higher population and is more built up than a rural area.

Snowball sampling - A sampling technique where existing participants help to recruit further participants in research.

Social cohesion - The extent of social connection within a group or society.

Social environment - The functioning of communities, such as how cohesive they are and how much they focus on mutual help. [footnote 13]

Stigma - The disapproval of, or discrimination against, an individual or group based on perceived characteristics. This can manifest itself as self-stigma (an internalised shame that people have around their own feelings) and social stigma (negative attitudes or beliefs towards an individual or group, based on experiences or characteristics which are seen to distinguish them from other people).

Structural factors - The broader political, economic, social, and environmental conditions and institutions that can increase or decrease the opportunities, resources, and wellbeing of individuals.

System-level interventions - The design and implementation of changes at a structural level (for example related to broader systems of funding or working relationships between organisations).

Topographic factors - Features of land surfaces.

Transport infrastructure - The fixtures and installations, structures, and networks which allow the movement of people and goods, such as bus stops, roads, cycle lanes, and pavements.

Urban area - A built-up area with a large population (over 10,000). [footnote 14]

VCSE - An incorporated voluntary, community, or social enterprise organisation which serves communities.

Walkability - The ability to safely walk to services and amenities within a reasonable distance.

Executive Summary

This report presents findings from a research project that explored how social connection and loneliness relate to physical and social structural factors. Previous research has shown that chronic loneliness is associated with higher mortality rates and poorer physical health outcomes. A recent evidence review examining inequalities in loneliness [footnote 15] identified six structural factors that can influence loneliness, two of which are the focus of this research: the physical and social environments. The physical environment includes factors such as transportation infrastructure, housing type and provision, and green spaces. The social environment includes factors such as social cohesion and community belonging. To further develop the evidence base around how these structural factors affect loneliness and social connection, The Department for Culture, Media, and Sport (DCMS) commissioned The National Centre for Social Research (NatCen) and RSM UK Consulting to answer the following research questions:

Research questions:

1. How do structural factors relating to physical and social environments impact loneliness in areas of high deprivation?

-

How does the local physical environment facilitate and/or create barriers to social connections?

-

How does the social environment facilitate and/or create barriers to social connections?

-

What indications are there, if any, that the role of the physical and social environments differ between urban, semi-urban and rural geographies in areas of high deprivation?

-

What, if any, are the general and distinct physical and social environment factors between areas?

2. What are the potential points of intervention on these structural factors that could influence loneliness for those living in areas of high deprivation?

-

How can communities identify mechanisms to tackle loneliness within their community and what is missing?

-

What interventions and/or solutions relating to the physical or social environment can help/are helping to support social connections?

-

How did successful interventions/solutions relating to the physical or social environment achieve change in local areas (e.g. the mechanisms and processes applied)?

-

Are there insights into how these interventions should be tailored to specific communities and/or geographies?

-

What are the facilitators and barriers for implementing these interventions?

-

How do local and central government stakeholders perceive their role in regard to these potential points of intervention?

To answer the above questions, this project applied the following methods:

-

Six focus groups with residents across three areas in England: Castleford, Oldham, and Torquay.

-

10 interviews with stakeholders from the selected areas, each with a role in the local physical and/or social environment.

-

One national stakeholder workshop, with representatives from multiple government departments and the Local Government Association.

Key Findings

How physical structural factors influence social connection and loneliness

-

Focus group participants highlighted how transport infrastructure (e.g. roads, pavements, and public transport) can both support and hinder social connection. Transport could enable focus group participants to visit friends and family, access broader social connections outside of their local community, and access increased work opportunities (leading to interactions with colleagues). Furthermore, public transport itself was cited as a place to meet and get to know others living locally. Transport-related barriers to social connection included feeling unsafe on public transport, the cost of tickets, service reliability, road congestion, parking, and the quality of cycle lanes and pavements.

-

Housing and neighbourhood design (e.g. housing type, layout, density, and tenure) influenced how focus group participants built social connections. For example, focus group participants described how housing estates had often been built with a communal space, which facilitated a sense of community. High levels of home ownership were felt to support a strong sense of community, whereas high levels of renting were felt to negatively impact a sense of community due to a more transient population. Focus group participants had mixed views on the role of housing density on social connection. For some it enabled more people to chat and children to play together, whereas others noted concerns around an imbalance between high housing density and sufficient infrastructure which could lead to tension and frustration.

-

Green and blue spaces (such as parks, nature reserves, beaches, and canals) were felt to be important to building social connections. These spaces were a place to meet others, socialise (e.g. picnics), and attend events or initiatives, as well as support physical, social, and psychological health. In general, focus group participants used green spaces to meet those they had existing relationships with, and although in some cases residents greeted one another in outdoor spaces, this rarely led to long-term social connections. Transport costs were cited as a key barrier to accessing green space, especially for spaces located far from residential areas (e.g. nature reserves). The appeal of using green spaces was affected by high levels of litter and anti-social behaviour.

-

Local buildings and spaces acted as both a facilitator and barrier to building social connections, depending on their availability and quality and wider factors such as anti-social behaviour. In all three areas, the decline of high streets and closing of local pubs, bars, and other spaces (e.g. theatres) impacted focus group participants’ ability to socialise with others in local venues. In addition, focus group participants and stakeholders emphasised the benefits of local community centres and youth centres for community cohesion and building social connections locally.

-

A number of interventions relating to the physical environment to support social connection were identified across the three areas. These fell into three main categories: connecting people to the physical environment, maintaining the physical environment, and creating new physical spaces. These included cycle lane improvements, bus routes to connect focus group participants living in different areas, supporting local shops and facilities, maintaining green spaces (e.g. community gardens and coastal path maintenance to ensure beach accessibility), and creating new spaces for interaction (e.g. benches and community “lounges”). Stakeholders emphasised the importance of resident involvement in the development, design, and implementation of physical space intervention to ensure that interventions were based on local community needs but in general found it difficult to outline how local needs were identified and mechanisms for change. Stakeholders were less aware of how communities identify mechanism to tackle loneliness, how interventions achieved change, and how interventions could be tailored to specific communities.

How social structural factors influence social connection and loneliness

-

Common interest-based groups and activities were identified as ways to build social connection locally by focus group participants and stakeholders. They tended to focus on sport and exercise, arts and crafts, and family. These were hosted in a range of venues, including community centres, places of worship, libraries, and sports venues. Groups and activities tended to target specific demographics, which often pertained to age and gender, to bring people with common experiences together. This included structured youth clubs (e.g. musical performance and school holiday food provision) and drop-in activities for older people (e.g. coffee mornings and dementia peer support). Focus group participants reported a limited number of groups, events, and “bumping spaces” (places where people can meet or interact spontaneously i.e. ‘bump into each other’) that were designed for the general public and did not focus on a specific interest or hobby.

-

Barriers to involvement and participation in local groups, activities, and events included a lack of awareness, and advertising format diversity (e.g. print and social media). Focus group participants noted that social media was often a key information source yet reached a limited number of people. They also highlighted the decline of local newspapers in which to advertise groups and activities across all three areas. Focus group participants also felt that many available groups occurred during the day when many were at work. Other barriers included accessibility challenges due to limited transport and active travel options, as well as activity costs.

-

Focus group participants had mixed feelings about social cohesion and their sense of belonging to where they lived. Whereas some had historical ties to their area, others found it difficult to meet new people and felt frustrated that some friends had moved away. Some focus group participants did not have ties to the local area, but lived there due to cheaper housing costs. This meant that their social life existed elsewhere, which acted as a barrier to building social connections locally.

-

Interventions relating to the social environment were identified in the three areas. These fell into three main categories: connecting people to groups and services, connecting people to each other, and connecting groups and services to each other. This included mapping local services for referrals, a single-point referral platform for multiple services, neighbourhood organisation, and moving services closer to each other or target groups.

-

Local partnership working (e.g. between Voluntary, Community and Social Enterprise (VCSE) organisations and local councillors) was cited as a key facilitator to building interventions. Barriers included a lack of clarity about roles and responsibilities between organisations and increased demand for more essential services. Stakeholders were less aware of how communities identify mechanisms to tackle loneliness, how interventions achieved change, and how interventions could be tailored to specific communities.

The relationships between social connection and physical and social environments

- Local groups, activities, and events were often reliant on high quality, safe, and accessible physical spaces in order to take place. This included green spaces to host exercise classes or events, and spaces such as libraries or community centres to host local activity groups. Conversely, the social environment was often key to the development and maintenance of physical environment spaces.

Role of local and central government stakeholders

-

National stakeholders who were consulted as part of the workshop (largely a sample of central Government representatives) felt that the role of central government departments was primarily to provide strategic direction on matters such as wellbeing, community cohesion, and green spaces, as well as providing funding and resources to stakeholders at a local level. National stakeholders felt that many of the issues highlighted in this research should therefore primarily be addressed and led by local government (with support from central government, VCSE organisations, local businesses and key stakeholders, including the police).

-

Local stakeholders held varied views on the role of local and central government, particularly when it came to the social environment. There was a general consensus that any initiative should be produced collaboratively with both local/central government and stakeholder organisations in the area.

1. Introduction

1.1 Background to the research

Loneliness is defined as “a subjective, unwelcome feeling of lack or loss of companionship. It happens when we have a mismatch between the quantity and quality of social relationships that we have, and those that we want”. [footnote 16] Chronic loneliness (defined as feeling lonely often or always) has been shown to be associated with higher rates of mortality and poorer physical health outcomes, [footnote 17] and additionally predicts the onset of severe Common Mental Disorders (CMD), such as depression and anxiety. [footnote 18] [footnote 19] Furthermore, qualitative research has found a cyclical and bidirectional relationship between loneliness and mental health. [footnote 20]

The government’s tackling loneliness strategy [footnote 21] sets out the government’s approach to tackling loneliness in England with the overarching aims to reduce stigma around loneliness, drive action across sectors, and build the evidence base around loneliness. A review of the existing evidence base around tackling loneliness in 2023 [footnote 22] recognised that structural factors are important drivers of stigma and are likely to influence experiences of loneliness, particularly among marginalised communities. The six identified structural factors were:

-

Area deprivation (Crime rates, socio-economic status)

-

Community attitudes (Prejudice, loneliness stigma)

-

Demographic diversity (Absolute diversity, group representation)

-

Physical environment (Transportation, housing, green space)

-

Public policy (Discriminatory policy, diversity policy and Neoliberalism)

-

Social environment (Social cohesion, community belonging)

The review highlighted that although structural factors are “amenable” to change, there is a lack of evidence regarding how they influence loneliness, which structural factors cause loneliness, and how these can be addressed.

The review concluded that further research is needed to understand how structural factors affect loneliness, which draws on specific lived experiences and obstacles for social connection with affected communities. This research focuses on two of these structural factors, which were selected by DCMS as it was felt these were two areas that DCMS could have most impact in. Please see below:

-

The physical environment: This includes factors such as transportation infrastructure, housing type and provision, and green space; and

-

The social environment: This includes factors such as social cohesion and community belonging.

There is a broad scope of applicable structural factors and experiences of impacted marginalised groups. This research therefore does not aim to make conclusions around the comparative importance of different structural factors between communities. Instead, it focuses on the interplay between social connections, the physical and social environment, and area deprivation, while engaging with a diverse sample of participants. While area deprivation can be considered a structural factor in itself, this research examined how it can influence the physical and social environment specifically (and deprivation metrics were used to influence the selection of areas, as outlined in section 1.3 below).Comprehensively and accurately assessing changes in loneliness (particularly among different groups) is challenging. However, there is a clear evidence base that stronger, more vibrant communities can support the alleviation of loneliness. [footnote 23] It is also important to understand how physical and social structural factors impact social connection as part of wider initiatives to tackle loneliness.

1.2 Research aims

To gain insights into how social connection and loneliness relate to physical and social structural factors, the Department for Culture Media and Sport (DCMS) commissioned the National Centre for Social Research (NatCen) and RSM UK Consulting (RSM) to explore the following research questions:

1. How do structural factors relating to physical and social environments impact loneliness in areas of high deprivation?

-

How does the local physical environment facilitate and/or create barriers to social connections?

-

How does the social environment facilitate and/or create barriers to social connections?

-

What indications are there, if any, that the role of the physical and social environment differ between urban, semi-urban and rural geographies in areas of high deprivation?

-

What, if any, are the general and distinct physical and social environment factors between areas?

2. What are the potential points of intervention on these structural factors that could influence loneliness for those living in areas of high deprivation?

-

How can communities identify mechanisms to tackle loneliness within their community and what is missing?

-

What interventions and/or solutions relating to the physical or social environment can help/are helping to support social connections?

-

How did successful interventions/solutions relating to the physical or social environment achieve change in local areas (e.g., the mechanisms and processes applied)?

-

Are there insights into how these interventions should be tailored to specific communities and/or geographies?

-

What are the facilitators and barriers for implementing these interventions?

-

How do local and central government stakeholders perceive their role in regard to these potential points of intervention?

1.3 Methods and participants

This research consisted of three parts: focus groups with participants from three local areas of high area deprivation, in-depth interviews with stakeholders from the selected local areas, and a workshop with national government stakeholders. Full details of the sample, methodological approach, and ethical considerations are provided in Appendix A.

Area selection was informed by the existing evidence base and government policy interests, as well as practical factors related to the feasibility of recruitment in the timeframe of the project and location of recruitment resources. The Tackling Loneliness Evidence Review [footnote 24] recognised that area deprivation and environmental features (e.g. green spaces, transport, and volunteering opportunities) are linked to loneliness. There is evidence that communities living in areas of higher deprivation have less access to quality green spaces, [footnote 25] [footnote 26] [footnote 27] [footnote 28] safe public places, [footnote 29] and public transport. [footnote 30] [footnote 31] [footnote 32] As such, in collaboration with DCMS and the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG), NatCen selected three areas three areas that had been selected for the Levelling Up Partnership Programme and the Long-Term Plan for Towns (government funding for 55 towns to provide long-term investment for local priorities) [footnote 33] that:

-

Ranked low for the following domains of the Indices of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) [footnote 34]: barriers to housing and services and living environment

-

Offered geographical properties that enabled us to explore the relationship between social connection and physical and social structural factors

-

Were located where our recruitment partner, Criteria, had sufficient local resources to recruit participants within the given timeframe

Three local areas were chosen (see Figure 1 below):

-

Castleford (a semi-urban area within the City of Wakefield district in West Yorkshire, surrounded by rural areas)

-

Oldham (an urban area which is a borough of Greater Manchester in North West England)

-

Torquay (a coastal town in Devon in South West England, surrounded by rural areas)

Figure 1: Map of England showing locations of selected local areas

Focus groups

Two focus groups were conducted in each of the three selected areas with local residents that had experience of loneliness. Age was the primary sampling criteria, with one focus group including participants aged 18-40 and the other including participants over 41. Secondary sampling criteria (ethnicity, living arrangements, relationship status, and socio-economic status) were also monitored. Focus groups aimed to gain the perspectives and experiences of residents around the local physical and social environment, and the related impacts on building and accessing social connections.

Interviews with stakeholders

Interviews were conducted with 10 stakeholders from the areas selected, each with a role in the local physical and/or social environment. Participants included those working for the local government (n=2) and Voluntary, Community and Social Enterprise (VCSE) organisations (n=8). Due to challenges recruiting stakeholders working in local government, a higher number of stakeholders working for VCSE organisations were included. In some cases these stakeholders worked closely with local government as part of their role. Interviews provided insight into the influence of physical and social factors on social connections in local areas and interventions that have been tried to support social connection.

National stakeholder workshop

A workshop was conducted with central government stakeholders with responsibilities related to the physical and social environments (e.g. transport, communities, anti-social behaviour). This included stakeholders from DCMS, the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA), MHCLG, and the Department for Transport (DfT), and one stakeholder for the Local Government Association (LGA), The workshop aimed to gain an understanding of how findings from focus groups and stakeholder interviews could be generalised to the wider population, including the role and responsibilities of central government in interventions to improve social connection.

1.4 Analysis and interpretation of findings

All areas of fieldwork (focus groups, local stakeholder interviews, and national stakeholder workshop) were audio recorded, with consent from participants, and subsequently transcribed. Data was analysed and managed using the ‘Framework’ approach[footnote 35] , whereby a framework was used to represent individual focus groups or interviews in each row. Each column then represented a research question, sub-question, or theme. Through this method, data was grouped and could be analysed and presented thematically to explore the full range of views and experiences expressed across work strands. This report does not present numerical findings, since qualitative research cannot support numerical analysis. Instead, the qualitative findings present in-depth insights into the diverse range of views and experiences of participants, influenced by demographic and life experiences, with verbatim quotes used to illustrate insights.

1.5 Structure of the report

This report is divided into the following sections:

-

Chapter 2 discusses how physical structural factors influence social connection and loneliness

-

Chapter 3 discusses how social structural factors influence social connection and loneliness

-

Chapter 4 summarises findings on the relationships between social connection and physical and social environments and makes recommendations for future research

-

Appendix A presents place-based case study findings from Castleford, Oldham and Torquay

-

Appendix B provides a more detailed methodology for the research

2. Structural factors and the physical environment

2.1 Features of the physical environments

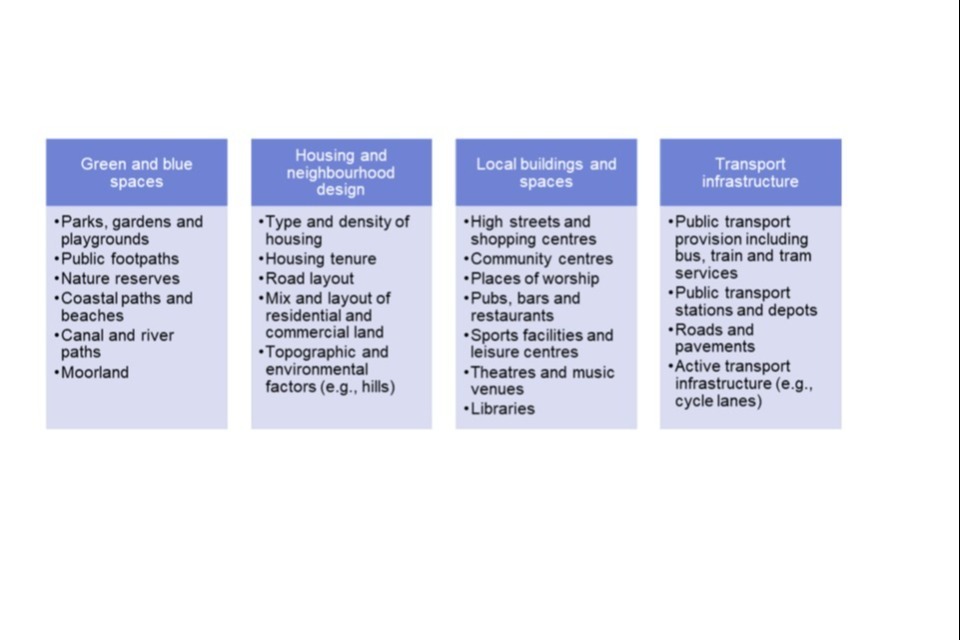

The term ‘physical environment’ refers to how the places where we live, study, work and take part in leisure activities are built and connected. [footnote 36] Stakeholders and focus group participants identified several key features of the physical environment that impacted social connection (either positively or negatively). These included green space, housing and neighbourhood design, local buildings and spaces, and transport infrastructure (see Figure 2 below).

Figure 2: Features of the physical environment which impact social connection

Across the three areas, stakeholders reported that local authorities were mainly responsible for features of the physical environment, with some variation between areas in relation to non-statutory provision e.g. of community centres. However, it should be noted that a low number of local authority stakeholders were interviewed due to recruitment difficulties. Local authorities have a number of statutory duties including planning and housing services, road maintenance, library services, waste collection, and transport planning. [footnote 37] Stakeholders highlighted that other organisations such as Voluntary, Community and Social Enterprise (VCSE) organisations, residents groups, local businesses, and central government also play a key role in the creation, maintenance, and protection of the physical environment. The role of different organisations will be discussed further throughout this chapter.

2.2 The role of local physical environments in building social connection

Transport infrastructure

Transport infrastructure includes roads and paths used by individuals, private vehicles, and public transport networks. Focus group participants highlighted how public transport (e.g. trains and buses) can support social connection. In particular, by allowing people to visit friends and family who do not live locally, which enabled them to widen their social connections outside of the local community. While Torquay focus group participants highlighted the importance of train links to Exeter, focus group participants in Oldham highlighted the tram links to Manchester City Centre and Rochdale. The ability to connect with friends, family and colleagues using public transport was facilitated by fast connections to local towns across all three areas.

It [public transport] makes it accessible, it makes the world bigger for people. It’s not just what they can walk to. It means that people don’t have to socialise within their own community as well, which isn’t always what people want to do, so that helps

– Stakeholder (Oldham)

Focus group participants also described how public transport provides access to work opportunities, which can facilitate social connections through interactions with colleagues. For example, Castleford focus group participants described how the train connection to Leeds allowed them to access work opportunities that were not available in Castleford. Additionally, stakeholders felt that public transport to cities can allow specific minority communities (e.g. LGBTQ+ groups) to access bespoke social activities and support groups, where these are locally unavailable.

Some focus group participants reported that public transport itself could act as a place to meet and get to know others. For example, focus group participants in Torquay described how taking the same public transport route regularly could result in getting to know others who take the same route.

I do think that if people take the same bus every day at the same time, they get to know the same people…they will just chat in general as they’re travelling.

– Focus group participant (Torquay)

Focus group participants highlighted how transport infrastructure can create barriers to building social connections. Across all three areas, focus group participants reported sometimes feeling unsafe on public transport or in stations (e.g. bus/train/tram), creating a disincentive to travel and meet others. For example, Castleford focus group participants perceived the last train from Leeds on a weekend to be “rowdy”, while buses had previously been cancelled due to vandalism.

Focus group participants highlighted several other barriers to accessing transport to build social connections. These included their proximity to transport stops, ticket costs, service reliability (e.g. frequent delays and/or cancellations) and timetabling (e.g. the last train back to a home station being earlier than desired). Of those focus group participants who used private transport (e.g. cars), road congestion and challenges finding safe and affordable places to park were sometimes barriers to socialising.

Active travel and walkability

Active travel involves making journeys in physically active ways, including by walking, using a wheelchair, or cycling[footnote 38] . Focus group participants highlighted ways that active travel can facilitate social connection. For example, walking or cycling to meet others on a local high street, as well as travelling to a public transport stop or station. This could enable social connection where other forms of transport were not available or accessible (e.g. residents who did not have a private car, or where the cost of public transport tickets was a barrier). However, focus group participants also reported that poor quality cycle lanes and pavements could make active travel to meet others challenging. One disabled participant who used a mobility scooter highlighted how challenges with the quality of pavements was particularly an issue for those with a disability. Torquay focus group participants also highlighted how the hilly layout of the town rendered active travel difficult, especially for those who lived on hills further from the town centre.

Housing and neighbourhood design

The physical environment is also constituted by housing and neighbourhood design. This can include factors such as housing type, layout, density, tenure, and the mix of residential and commercial land. Focus group participants had mixed views on housing and neighbourhood design and varied experiences of building social connections with their neighbours. As well as variation between the three case study areas due to specific local challenges (e.g. a high proportion of holiday homes in Torquay), focus group participants living in different areas of the same town often had different experiences. These tended to relate to the type (and design) of housing they were living in and broader factors, such as a higher proportion of holiday homes in certain neighbourhoods.

Focus group participants and stakeholders described how some types of housing (e.g. housing estates) had been built with communal spaces (e.g. community centres and/or pubs). It was felt that these facilitated social connection with neighbours, although they reported that many such spaces had since closed. Despite this, some focus group participants felt that living on a housing estate brought a sense of community compared to other types of housing (such as terraced streets) and felt that neighbours looked out for each other.

I found there was more of a camaraderie on a council estate, to be honest with you. People looked out for each other a bit more than they do anywhere else.

– Focus group participant (Oldham)

Social connection was also influenced by housing tenure (e.g. renting and home ownership), as this impacted how long focus group participants stayed in the same area. Focus group participants in Oldham reported that some local areas had a strong sense of community due to long-term inhabitants and high levels of home ownership. In other areas, social connection was negatively impacted by the prevalence of renting and residents (not necessarily focus group participants) consequently moving around frequently. This made it more difficult to build long-term relationships with neighbours and those living locally. One stakeholder working with Oldham residents reported this was a particular challenge for those living in temporary accommodation. They felt that local community connection was often a secondary thought for local residents, as insecure housing resulted in uncertainty around how long they would be in a particular building, street, or area.

Focus group participants had mixed views on the role of housing density on social connection. Some highlighted that dense housing enabled people to chat and children to play together, particularly in the summer. Conversely, focus group participants highlighted that high housing density combined with insufficient infrastructure (e.g. a lack of parking and communal spaces), can lead to frustration and prevent positive social interaction.

When you tend to find there’s no communal space and the housing density is really high, and there’s a lack of infrastructure and parking, then you get people grating on each other and not interacting in a positive way. If it’s a little bit less dense, a little bit more communal spaces and better links, you do get social interaction and some community events even occasionally

– Focus group participant (Castleford)

Focus group participants and stakeholders also identified empty homes as a barrier to connecting with others locally. Although homes could be empty for a range of reasons, Torquay focus group participants highlighted a particular issue with part-time second or holiday homes.

Green and blue spaces

Green spaces are an important form of public space with a range of research pointing to their mental health and wellbeing benefits [footnote 39]. Green spaces can include parks and gardens in urban and semi-urban areas, as well as nature reserves, woodland, and farmland. Blue space refers to environments close to water. This includes both natural and manmade sources, such as rivers, lakes, the sea, marinas, and canal paths. Blue spaces contribute to physical, social, and psychological health, offering the opportunity for sports and exercise[footnote 40].

Focus group participants described how local green spaces were a place to meet others, socialise, and attend events or initiatives. In Castleford, this included St. Aidan’s Nature Reserve or Pontefract Park, while in Oldham focus group participants described socialising during summer walks along local canal paths. In Torquay, focus group participants highlighted a “wealth” of green and blue spaces for socialising near the seafront, including playgrounds, coastal paths, beaches, moorland, and downs.

We’re very lucky; we’re within five minutes’ walk of the beach and we’ve got the greens. We’re within ten minutes’ drive of about three or four parks, so we can – we do meet a lot of people socially with the dogs.

– Focus group participant (Torquay)

Although focus group participants described saying “hello” to strangers that shared green spaces, such interactions rarely led to long-term friendships. Instead, focus group participants generally used green spaces to meet people they had existing relationships with. In some cases, green spaces hosted local clubs and events (see Chapter 4), such as community Eid celebrations in Oldham.

Focus group participants and stakeholders highlighted three main barriers to using green spaces, related to their accessibility and appeal. Firstly, the cost of transport to reach green spaces was emphasised as a barrier, particularly for those on low incomes. This was a greater challenge when accessing green spaces that are often further from residential areas, such as nature reserves. Secondly, focus group participants highlighted challenges with litter. They felt that this was often due to a lack of bins or waste collection in green spaces and reported that it discouraged them from using spaces to socialise. Thirdly, the impact of anti-social behaviour was consistently raised by focus group participants across all three areas. Focus group participants reported that some local parks were primarily used by teenagers, who they felt damaged facilities. This resulted in others not wanting to use local parks or feeling unsafe while there. Parents also expressed safety concerns for children around park playgrounds, with one resident citing a previous experience of finding broken glass.

Several other barriers were highlighted. Focus group participants and stakeholders emphasised that local green spaces did not appeal to all residents, with some people preferring to spend time in places more local to them where they would know others. Stakeholders in Torquay highlighted that some young people living in the town had never been to a beach, despite a wealth of local coastal areas. However, the reasons for this were unclear and this point was not raised by focus group participants in Torquay. Focus group participants in Castleford also had concerns that local green spaces were being built on, particularly for newer housing estates. They felt this was limiting the green spaces available for them to socialise in.

Local buildings and spaces

Local buildings and spaces include a wide range of places, from retail and leisure facilities to community centres and places of worship. Local buildings and spaces can act as a facilitator or barrier, depending on their availability and quality.

Focus group participants had mixed views on the availability of local spaces and venues to meet with others. They highlighted that retail parks and leisure centres can act as meeting places for the community. For example, focus group participants in Castleford highlighted the Junction 32 shopping centre as a place to visit restaurants, cafes, and shops with friends. Events venues, such as the Queen Elizabeth Hall in Oldham, were also reported as places to meet and spend time with others.

In all three areas focus group participants felt that the decline of high streets and closing of local pubs, bars, and other spaces (e.g. theatres) impacted their ability to socialise with others in local venues. In Castleford, focus group participants described the high street as “failing”, emphasising the presence of empty shop units and low footfall which disincentivised them from shopping or socialising there. In Oldham, some focus group participants chose to travel to other areas, such as Ashton-under-Lyne or central Manchester. This was due to a perceived lack of local shops, facilities, and social spaces to meet up with friends in Oldham town centre. In Torquay, focus group participants and stakeholders discussed how the town centre had also experienced decline. In particular, they highlighted that the closing of shops, banks and post offices had led to them using the town centre less frequently.

Focus group participants and stakeholders emphasised the benefits of local community centres and youth centres for building social connection and community cohesion.

Stakeholders described how, in Torquay, many housing estates were designed with embedded community centres and how there had also been a growth in the number of youth centres in recent years. In Oldham, community centres (e.g. The Honeywell Centre) provided a space for local groups to meet. These spaces also provided places for support groups and activities, and the green spaces outside centres were often used for football and exercises classes. Despite the social benefits of community centres, focus group participants felt they were often focused on support for specific groups or offered specific classes and did not provide a space just to socialise. They compared centres to physical spaces, such as pubs, which they perceived to be better for general socialising with friends and neighbours. This reflection was echoed by stakeholders. One stakeholder in Torquay described how many community centres are now run by specific charities or organisations, which focus on support for certain groups (e.g. adults with learning difficulties). In general, focus group participants and stakeholders discussed spaces for people to meet existing social connections. It should be noted that spaces to meet new people are also likely to be important for combatting chronic loneliness. This theme links closely to the social environment and is explored further in Chapter 3.

2.3 Interventions relating to the physical environment to support social connection

Focus group participants and stakeholders identified a range of potential intervention points related to the physical environment to improve social connection. These points of intervention spanned green spaces, local buildings and venues, neighbourhood design, and transport infrastructure (see Figure 3 below).

Figure 3: Potential points of intervention related to the physical environment to improve social connection

Stakeholders discussed physical environment interventions that tended to fall into three main categories: connecting people to the physical environment, maintaining the physical environment, and creating new physical spaces. These included cycle lane improvements, bus routes to connect residents living in different areas, supporting local shops and facilities, maintaining green spaces (e.g. community gardens and coastal path maintenance to ensure beach accessibility), and creating new spaces for interaction (e.g. benches and community “lounges”). Although stakeholders identified a number of interventions, as well as barriers and facilitators to their implementation, they were less aware of other areas. In particular, how communities identified mechanisms to tackle loneliness, how interventions achieved change, and how interventions could be tailored to specific communities. The following specific interventions were identified:

Castleford

-

Castleford Connections Project[footnote 41] : Wakefield council was successful in gaining £23.9 million from the Government’s Towns Fund to support a range of local projects in Castleford. One of the four key projects is “Castleford Connections”, which has also secured additional funding from Network Rail. The project aims to improve active travel infrastructure for pedestrians, wheelchair users, and cyclists by improving signage and ensuring clear directions to key locations (e.g. train and bus stations, Castleford market, and heritage attractions). The project started in early 2024 and will be running until early 2026.

-

First and Last Mile Funding Project: Castleford was allocated £720,000 in 2023 from Network Rail to improve the surrounding areas of Castleford train station. The project aims to increase train usage, improve passenger experience, and improve air quality. It will involve increased CCTV coverage, lighting, and public art.

Oldham

-

Town Centre Regeneration Projects: Stakeholders highlighted several projects focused on the regeneration of Oldham town centre. This has included the installation of cycle lanes to support active travel, the pedestrianisation of some streets, and adding gym equipment to local parks. However, stakeholders highlighted barriers to the success of interventions, including access to, and affordability of, bikes for many residents.

-

Chatty Café Project: This project involved setting up “Chatter and Natter” tables within local cafes, where customers can sit if they are happy to talk to other customers. The project was part of a wider initiative to set up tables across the UK [footnote 42] and was supported by Oldham Council, local charities, and businesses. However, stakeholders had mixed views on the success of the project, with some highlighting that some tables were not being used.

Torquay

-

Friendly Benches Project: The “Friendly Benches Project” involves identifying benches in public spaces, such as parks and walking routes, and designating them (with a sign) as “Friendly Benches”. The concept is that anyone sat on the bench would be open to having a conversation with someone else locally. The project has involved local residents who have been involved in decisions about where the benches should be.

-

Torquay Community Lounge Project: Torbay Communities (a local charity that aims to create stronger and more resilient communities), set up a lounge in Torquay for those experiencing loneliness. The lounge offers a space for people to spend time with others, without taking part in specific activities or events, a need identified by the local community. Residents were involved in the development of the space. Stakeholders highlighted that a key facilitator to the success of the project was giving agency to residents to create and decorate the space as they wanted. One stakeholder described how the space functions as a place both for residents to meet each other as well as a safe space where housing officers and social workers could meet residents.

It became the baseline for other things to happen because you have people who wouldn’t ordinarily have crossed paths going in there, talking, chatting.

– Stakeholder (Torquay)

Facilitators to implementing interventions

Stakeholders emphasised the value of resident involvement in the development, design, and implementation of physical space interventions. For example, stakeholders in Torquay highlighted how residents were involved in the development of the “Community Lounge” and “Friendly Benches” Projects. This resulted in interventions which were based on local community needs and that residents were invested in.

Barriers to implementing interventions

Many of the local physical environment interventions highlighted by stakeholders were run by VCSE organisations, or partnerships between these organisations and the local authority. Stakeholders working in VCSE organisations highlighted a lack of certainty about long-term funding for some local community organisations, which constrained planning of future physical environment-related projects and interventions. Challenges related to insufficient local government funding security were also raised in the national stakeholder workshop. Such challenges may have knock on effects for VCSE organisation projects aiming to improve the physical environment which are more reliant on local government funding.

Stakeholders also highlighted how delays to previous local council projects had led to challenges with trust among residents, with many questioning whether new projects or ideas will come to fruition. They felt that this had led to some residents losing faith in the local area and council, which is a barrier to engaging people in future interventions locally.

That [delays to previous projects] breeds that resentment. People don’t have any sort of faith in the local area and in the system.

– Stakeholder (Torquay)

The role of local and central government

Overall, there was consensus among national stakeholders on the role of central government. This was two-fold:

-

Providing strategic policy direction on issues related to the physical environment (such as transport); and

-

Providing funding and resources to stakeholders at a local level (for example through local government funding or specific national funding programmes).

UK government departments highlighted previous central government programmes of work, which aimed to address challenges highlighted by local stakeholders and focus group participants. An example of a government department’s involvement in seeking to enhance social connection includes the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA)’s work to promote increased access to good quality green and blue spaces locally. National stakeholders also highlighted the “Tackling Loneliness with Transport Fund” led by the Department for Transport (DfT), where 12 pilot projects were funded to support those experiencing loneliness to engage in transport-based activities to build and sustain their social connections.

3. Structural factors and the social environment

3.1 Features of social environments

The term ‘social environment’ refers to the functioning of communities, including how cohesive they are, how much they focus on mutual help, and access to local groups and activities[footnote 43] . Stakeholders and focus group participants identified several key features of the social environment that impacted social connection (either positively or negatively), which will be discussed in this chapter. These included the range and timing of local groups, activities and events, as well as social cohesion and sense of belonging.

Across the three areas, stakeholders felt that local authorities have some responsibilities for the social environment (e.g. commissioning support services, such as social work). This role is supported by Voluntary, Community and Social Enterprise (VCSE) organisations and the private sector, through the development and maintenance of the social environment (e.g. running social groups and activities). The role of these different organisations will be discussed further throughout this chapter.

3.2 The role of local social environments in building social connection

Local groups, activities, and events

As might be expected, stakeholders expressed greater knowledge of the local social environment than focus group participants across the three areas. This generally consisted of activities and groups that were interest-based or targeted at specific demographics, as well as wider groups, events, and “bumping spaces”. Please see Appendix A for a more detailed description of the social environment in each area.

Common interest-based groups and activities tended to centre on sport and exercise (e.g. badminton, football, Pilates, rugby, running, and yoga), arts and crafts (e.g. knitting, sewing, theatre, cooking, and music), and family (e.g. parent and baby groups). These were hosted in a range of venues, including community centres, places of worship, libraries, and sports venues. In Torquay, local green and blue spaces were also leveraged to create activities around coastal walking and wild swimming.

Everyone stuck together and really helped each other out and clapping as they all came round [running] and stuff and give you that kind of support. People became quite friendly off the back of that.

– Focus group participant (Oldham)

Groups and activities also targeted specific demographics, often pertaining to age and gender, to bring people with common experiences together. This included youth clubs and projects, such as the year-round participatory activities delivered by the Torbay Youth Trust (e.g. musical performance and informing health commissioning), school holiday-based food provision in Oldham, and activities such as bowling at The Hut, a youth centre in Castleford. Those activities aimed at older people tended to work on a drop-in basis (e.g. bingo, coffee mornings, and dementia peer support), such as the local Wakefield Age UK-run “Time for Tea” service. Group activities targeting men mostly focused on mental and physical health. In particular, participants across all three areas reported that Andy’s Man Club operated locally. These clubs provide opportunities for local volunteers to provide peer-to-peer support around mental health and were also perceived as an opportunity to build social connection. Groups specifically for women were also identified in Oldham and Castleford. These tended to take an intersectional approach by either aiming to support or appealing to minority ethnic women (e.g. Black African and South Asian women, as well as refugees and asylum seekers), parents with children or grandchildren in school, or new mothers.

I think I made a lot of social connections and then from there, I think I’ve helped quite a lot of ladies.

– Stakeholder (Oldham)

Participants reported a lack of inclusive groups, events, and “bumping spaces”, which appealed to the general public and did not focus on a specific interest or hobby (see section below on how this can create barriers to engaging with the social environment). Participants identified examples of these types of events; in Torquay, this included events hosted at Torre Abbey (e.g. festivals, film viewings, and talks) and a cost-of-living event that aimed to provide people with advice and guidance on managing finances. Conversely, public events such as carnivals and the switching on of Christmas lights were promoted to a wider range of people. Focus group participants in Torquay reported that the town previously hosted an annual carnival to bring people together, but that this no longer happened. In Castleford, focus group participants identified the local switching on of the Christmas lights as an opportunity to build social connections. However, they also noted that events in other local towns were better advertised and coordinated, and as a result better attended.

Barriers to involvement and participation in local groups, activities, and events

Focus group participants across all three areas expressed a lack of awareness about local activities, groups, and events. They linked this to advertising being limited in both quantity and format diversity. The main reported source of activity and group information was social media (e.g. the local Facebook page). However, many focus group participants did not use such platforms and/or felt that they reached a limited population (a view shared by stakeholders). Although some focus group participants reported being made aware of local events through print (e.g. door leaflets), many noted a distinct lack of physical or print advertising. For example, focus group participants in all three areas reported how free local newspapers that widely advertise social activities were discontinued, and nothing had replaced them. Stakeholders in one area also reported that attendees were often referred to activities (e.g. through the local authority or social prescribers), which was thought to limit their reach.

I don’t really know what groups exist, but there might be lots, and actually I just haven’t discovered them, because I do other things instead outside of Torquay, but in terms of advertisement, I’m not sure I see too much.

– Focus group participant (Torquay)

Across all three areas, many focus group participants reported that local activities, groups, and events had a narrow appeal to the broader local population, which focused on specific demographics (e.g. older and younger people) or occurred during the day. In particular, it was felt that there was a lack of activities that generally targeted working age adults and parents/families. The exception to this was in Castleford where focus group participants highlighted an increased need for opportunities to build social connections during this life stage. Stakeholders recognised that community-based activities tended to take place during the day, which limited the people who could attend, with one stakeholder reporting that there was increased demand for weekend-based activities. In Torquay, focus group participants and stakeholders noted the seasonality of activities and events during the summer months, resulting in fewer year-round social opportunities for permanent residents.

There’s not just a nice safe place for somewhere for families to go, your kids can play and meet new people and things like that. So, that’s something that’s lacking within the area.

– Focus group participant (Oldham)

It [activities and groups] tends to be the older generation that go to those events. I have been to a couple, but I feel like I don’t kind of fit there.

– Focus group participant (Castleford)

Stakeholders identified that activities, groups, and events were not always accessible for prospective attendees. This included digital exclusion whereby opportunities were solely advertised online, attendees being unable to make their way to the venue via transport or active travel (particularly in Torquay), lack of accessibility within venues, and language barriers (highlighted in Oldham). Stakeholders identified that a lack of available support and services (e.g. for drug and alcohol use, mental health, occupational health, and social care assessments) resulted in some potential attendees finding activities inaccessible as their health declined. This resulted in those individuals becoming further isolated.

Although stakeholders and focus group participants identified free or subsidised activities, some participants highlighted cost and income deprivation as a barrier to taking part in social activities; particularly for certain groups such as families with young children. While for focus group participants this related to activities such as going to restaurants, bars, and pubs, stakeholders expressed concerns over more vulnerable people affording relatively less expensive (often subsidised) activities. This was described as a hierarchy of needs, [footnote 44] whereby increased costs for basic essentials (e.g. accommodation, clothing, and food) decreased any surplus to spend on activities, which was compounded by higher overheads and consequent increase of activity costs. In other words, people with limited financial resources have little, if any, money to spend on social activities once they have paid for their essentials. Subsequently, some people were ‘priced out’ of activities and became further isolated.

We need a whole little team of drivers that can just pick people up and take people places in their cars; that would be amazing if we could do that. Then at least some of those people would be able to go out.

– Stakeholder (Torquay)

If you’re worrying about where your next meal is coming from… where do you get the trainers from to go to the group? Where am I going to be sleeping?… [if] people haven’t got their basic needs met, then actually £2.50 to go to a community event or activity actually appears quite a lot.

– Stakeholder (Oldham)

Social cohesion and sense of belonging

Although focus group participants within and across areas had mixed views on feelings of a sense of belonging, they generally struggled to describe and define what a sense of belonging is or should mean. In Castleford and Torquay, focus group participants tended to report having historical family ties to the area, which in some cases contributed to a sense of belonging bolstered by long-term friendships. In contrast, others in Torquay found it difficult to meet new people and felt frustrated that some friends had moved away (e.g. for work or university). Although new people did move to the area, this was often temporarily for seasonal summer work, which made it difficult to socialise with them. While Oldham focus group participants also reported historical family ties, some were originally from or worked in nearby and more expensive areas (e.g. Trafford), and resided in Oldham due to its more affordable housing rather than a sense of belonging to the area. For example, one resident described how a change in work location (from Oldham to Manchester City Centre), had resulted in fewer social ties and feeling less connected to the area through work. Others with historical ties to Torquay and Oldham felt inclined to move away for employment opportunities, resulting in a trade-off between maintaining existing social connections and employment opportunities.

I feel connected because I like where I live…I’ve got a lot of family round here, but if there was a good opportunity I would leave

– Focus group participant (Oldham)

Across all three areas, focus group participants noted pull factors from nearby places perceived to have a better social environment in terms of facilities (e.g. nicer town centre, swimming pool, shops, and cafes), friends and family, and events. For example, Manchester City Centre and Trafford for Oldham, nearby villages and Exeter for Torquay, and Leeds for Castleford. This often led to focus group participants living in one place but choosing to seek and build social connections in another, impacting their sense of belonging to where they lived.

Feelings of social cohesion were mixed across the three areas, especially with regards to neighbours. In Torquay and Castleford, focus group participants reported feeling a low sense of community spirit. While neighbourly relations were described as friendly and unproblematic, they did not go as far to feel socially connected to their neighbours. Focus group participants generally struggled to ascertain why this was, sometimes comparing their area to nearby towns and villages that had a “community feel”. For some, it was felt that this was due to neighbours generally no longer speaking as much or a higher turnover of people due to the rental market (see Chapter 2), a particular seasonal issue in Torquay.

I think we [neighbours] look out for each other, but I wouldn’t go to the pub with them, necessarily. If I saw them there, I’d interact and we’d have a catch-up and things, but we’re not best of friends

– Focus group participant (Torquay)

Interventions relating to the social environment to support social connection

Stakeholders identified higher or system-level interventions, which aimed to encourage or support the types of activities, groups, and events referred to in section 3.1 and appendix A of this report. These fell into three main categories: connecting people to groups and services, connecting people to each other, and connecting groups and services to each other. These included mapping local services for referrals, providing a one-stop referral platform to connect people to multiple services, encouraging neighbours to organise and help each other, and moving services closer to each other or target groups (e.g. to a shopping centre) (see Figure 4). Although stakeholders identified a number of interventions, as well as barriers and facilitators (see below) to their implementation, they were less aware of other areas. In particular, how communities identified mechanism to tackle loneliness, how interventions achieved change, and how interventions could be tailored to specific communities

Figure 4: Potential points of intervention related to the social environment to improve social connection

The following interventions were identified:

Castleford

-

Castleford Town Board: The Castleford Town Board involves the local community in planning for the town’s future and helped develop Wakefield Council’s long-term strategy for Castleford town centre. The board meets regularly and brings together various stakeholders including local councillors, representatives from schools and colleges, VCSE organisations, West Yorkshire Police, and local businesses. A key role of the board is engaging with residents to identify key priorities for Castleford.

-

Time for Tea project: Run by Wakefield District Age UK, “Time for Tea” is a drop-in event run in communal spaces across Castleford. The aim of the initiative is to provide an opportunity for older people to gather and build or maintain their social connections, in a space they feel comfortable in. Local stakeholders highlighted how, for some participants, the initiative has led to the rekindling of old friendships.

-

Community Hub: Hosted at Castleford Library, the Community Hub is a social space used for arts and crafts, foodbanks and other initiatives. There are other venues within Castleford, namely ‘Queen’s Mill’ which also provide similar services. These community centres provide important access to social interaction within the wider community at little-to-no cost.

Oldham

- Oldham Community Advice Network (OCAN): OCAN is a web-based referral platform, which offers a single touchpoint to connect service users with multiple providers. By doing so, service users only need to give (often sensitive) information once, assistance is given to navigate complex systems, and a more holistic response can be made involving multiple organisations. Stakeholders reported that this can also systematically help people to access support in a timely way to help with social connection.

Torquay

- Good Neighbour Scheme: Run by Torbay Communities, the “Good Neighbour Scheme” encourages street-based support between neighbours to help build social connection/cohesion. Information, advice, and a “Community Builder” staff member are provided to assist coordination efforts. Neighbours are matched based on needs, skills, and availability. For example, people who do not leave the house would be matched with a nearby resident who can help with shopping and provide company.

Facilitators to implementing interventions

Local partnership working was highlighted as a facilitator by stakeholders. In Torquay, VCSE stakeholders reported having a good working relationship with local councillors, who can advocate for them or facilitate actions on their behalf. They also reported that a “Community Partnership” has been set up by the council. This involves regular meetings between local councillors, residents, the police, and third sector organisations, which facilitates dialogue about community related issues in order to plan interventions. One stakeholder also identified a platform that mapped local services, which provided a one-stop referral platform to connect people to multiple services.

Barriers to implementing interventions

Collaborative working challenges were reported by stakeholders with experience of working with other organisations. In particular, VCSE stakeholders found that fostering and maintaining a relationship with the local authority and police was difficult, due to a lack of communication and agreed actions not followed up after meetings. Other stakeholders reported the need to establish a better overview of local services, to provide a more holistic offer to service users through signposting and cross-organisational working.

A lack of clarity on roles and responsibilities was also cited by some stakeholders as a barrier to successful interventions. For example, local authority representatives in Castleford highlighted blurred lines between where their responsibilities correspond with those of other stakeholders/organisations. In the context of addressing concerns around anti-social behaviour, stakeholders in Castleford highlighted a lack of clarity between what the local authority can and should be doing and the remit of the police.

Funding was a key challenge reported by stakeholders. Firstly, funding was seen as short term and uncertain, which limited organisations’ ability to effectively plan long-term interventions alongside experiencing increased demand. To mitigate this, one stakeholder suggested local VCSE funding could be included in council tax, which would provide increased financial security and enable staff to focus on service delivery.

The demand for essential services was cited by stakeholders as a two-fold challenge to providing direct social connection or loneliness interventions. Firstly, stakeholders had to prioritise their own resources to provide for an increased demand for essential services. Secondly, service users were unable to attend activities perceived as less important due to the hierarchy of needs described above.

Stakeholders also highlighted how the setting up and embedding of new community hubs, such as youth centres, can be time consuming. One stakeholder working in Torquay described how a new youth centre has been recently set up, but only has a small number of users compared to other youth centres in the area, which are well used. They felt this was because it takes time for youth centre staff members to build trust with young people.

The role of local and central government

As with the physical environment, there was consensus among national stakeholders that the role of central government within the social environment (such as anti-social behaviour or volunteering) was primarily one of providing strategic policy direction and providing funding and resources to stakeholders at a local level, including local authorities and VCSE organisations. A representative from the Local Government Authority suggested that the responsibility to fund and deliver local projects should sit with local councils, due to their knowledge and expertise of local issues.

UK government departments also highlighted many ongoing central government programmes/funds of work which aim to address social environment challenges highlighted by local stakeholders and residents. For example, the Department for Culture, Media, and Sport (DCMS), in collaboration with The National Lottery Community Fund are leading the “Million Hours Fund” [footnote 45]. The initiative is providing funding to youth organisations to extend youth support provision, to ensure that young people who may be at risk of anti-social behaviour have options to engage in positive activities.

Local stakeholders identified that the role and power of local authorities is currently restrained to ONS ward boundaries and central government’s long-term funding plans, although there can be wider confusion about responsibilities; one stakeholder representative from a local authority suggested that the public feel councils are “responsible for everything”. However, the local stakeholder believed that to deal with pertinent issues such as anti-social behaviour, there needs to be a combined effort from councils, VCSEs and organisations such as the Police. To combat this, as one example, Castleford’s upcoming Town Deal will aim to address the confusion around responsibility, by bringing together a board consisting members of the Police, Wakefield District Housing and other local organisations to help “steer and deliver the funding” to the correct places. The local stakeholder suggested this will help people see that “it’s not just the Council’s responsibility; it’s everyone’s responsibility to make a town as good as it can be”.

When looking at the social environment, the role of local government was echoed through another local stakeholder, as they commented that for initiatives to exist, the role of local government is to “facilitate bringing those groups together by making resources available for them, making places available for them, making it free, making it cheap, making it interesting”, as opposed to directly providing the services.

4. Discussion and recommendations

4.1 Summary of findings

The findings presented in this report go some way to addressing evidence gaps highlighted by previous research around how physical and social structural factors influence social connection and loneliness. This research found strong evidence that physical and social environments features can both support and hinder social connection. The identified structural factors tended to be consistent across the three areas; however, the specific relationships between those factors and social connection varied.

This research identified that for the physical environment, social connection can be influenced by:

-

The nature of (and access to) local green and blue spaces such as parks, nature reserves, beaches, or canal paths which provide spaces to meet others and attend events;

-

Housing and neighbourhood design, including the type and density of housing (and the influence of this on the ability to meet neighbours), housing tenure (influencing how transient local populations are), and road layout (affecting ease of access to surrounding areas);

-

Topographic and environmental factors, including terrain (e.g. hills which can make it more difficult to move between areas, particularly via active travel);

-

Types of local buildings and spaces available locally including community centres, sports and leisure facilities, theatres and music venues, libraries, and shops (which provide spaces to meet others and host activities); and

-

Transport infrastructure including public transport (including availability, safety, and cost), roads and pavements, and active travel infrastructure (e.g. cycle lanes) which can all provide ways to travel to meet friends and family and attend activities and events.

For the social environment, the following factors which influence social connection were identified:

-

Awareness, availability, and accessibility of local groups, activities, and events (which provide opportunities to meet others);

-

A sense of belonging to a local area and social cohesion;

-

Work and education opportunities available locally (the availability of local jobs and good schools resulting in residents (and families) staying in an area);

-

Seasonality and tourism (which can result in empty homes and transient communities); and

-

Opportunities for volunteering which can provide opportunities to build social connections locally.