Public messaging for summer concurrent risks: Extreme heat, drought and wildfires

Published 16 December 2025

Public messaging for summer concurrent risks: Extreme heat, drought and wildfires

July 2025

Executive summary

Background

This project aimed to assess the consistency of public-facing behavioural advice related to extreme heat, drought, and wildfires in the UK. It was commissioned by the Government Office for Science’s Social and Behavioural Sciences for Emergencies group. Using purposive sampling, advice to the public in a range of formats was obtained from national and local bodies, key messages were extracted and then categorised and analysed for consistency and any contradictions.

Key findings

-

69 sources were reviewed from UK and devolved governments, local government, public bodies and water companies. Within these, 1,209 messages were identified that contained behavioural advice to the public.

-

Advice on each risk was largely consistent, with similar information on extreme heat, drought or wildfires provided by a range of organisations.

-

Few contradictions were identified when 1 or more risk occurs concurrently, with some exceptions, which included: Extreme heat messages often advise people to stay indoors and open windows, but during wildfires this may not be safe and can undermine advice to evacuate. For wildfire related risks, there was inconsistent advice regarding whether barbecues and other open fires are permitted or prohibited in certain public outdoor areas. There were also contradictions between advice asking people to report fires immediately versus intervening if they felt confident to do so. Guidance on water resource management can be contradictory during periods when extreme heat and drought co-occur in terms of staying hydrated and maintaining hygiene while also conserving water.

-

Advice provided by local organisations was largely consistent with national bodies. Tailoring advice to local contexts can support behaviour change, but relatively few examples of this were identified.

-

Most sources advised the public to perform several behaviours with little or no clarification of which are most important for whom and in what context. Advice was not always clear or provided enough information about the conditions in which advised behaviours are beneficial. A good example of clarity and explanation from drought is “watering [the garden] in the early morning or evening to reduce evaporation”.

-

There were some gaps in advice for some groups or situations. There was inconsistency in terms of considering vulnerable groups (for example, older people, disabled people, those experiencing homelessness) and few examples of signposting to services, tools or resources for additional support. In advice relating to wildfires, child or pet safety was rarely mentioned.

-

Few documents used images to support their messaging, which evidence suggests is effective at capturing attention, communicating complex information simply, and aiding memory.

Recommendations

Despite the relative consistency in behavioural advice for each individual risk and few contradictions across risks, our review identified several recommendations to improve messaging and support relevant behaviours.

-

Prioritise, contextualise and sequence behavioural advice. When multiple actions are recommended, it would be preferrable to clearly prioritise behaviours based on urgency as well as health and environmental impact. Consistent, logically sequenced messaging can help people understand which actions to take first and in which contexts. Where possible, behavioural advice should be rooted in the local context.

-

Enhance clarity and coherence of messaging. Distinguishing between different behavioural goals (e.g. health protection vs resource conservation) and avoiding overlapping instructions is preferable. Use consistent and directive language appropriate for target populations and clearly explain the rationale behind each behaviour to support informed decision-making. Where summarising advice for short-form communications, ensure that details most relevant to recommended behaviours remain and clarity is maintained. Use pictures or images where possible rather than long blocks of text.

-

Coordinate cross-agency messaging and communication channels.Ideally develop integrated, multi-risk communication frameworks that align messages across organisations and risk; this could be supported by the development of guidance around how messages should be adapted and disseminated. This reduces duplication, ensures consistent use of terminology, and helps the public navigate advice from multiple authorities and channels.

-

Ensure inclusive and resource-aware communication.Messaging should consider the needs and constraints of vulnerable populations and key groups of interest (such as children and pets). Ideally behavioural advice would be accompanied by information on how to access support (e.g. access to services, tools or resources) where socioeconomic and structural barriers exist.

-

Improve signposting to alerts and information sources.Make sources and systems for monitoring warnings (e.g. rainfall gauges, river flow index, reservoir storage levels, heat-health alert, fire risk severity index, etc.) easy to understand and accessible and clearly signpost these sources. Employ a mixture of communication tools including alerts, social media posts, webpage updates to ensure high engagement with warning messages.

-

Messaging should be pre-tested and evaluation with relevant groups. Changes to or new communication strategies should be based on feedback and observed behaviours.

Project initiation and approach

Background

This project was conducted in response to a request from the Social and Behavioural Sciences for Emergencies (SBSE) group convened by the Government Office for Science, as well as stakeholders across government, including the Met Office, Defra and the Environment Agency.

Every year, environmental and health risks from drought, extreme heat and wildfires are expected. Several sources, including government and national agencies at UK and devolved nations levels provide behavioural advice on how the public should respond to each of these risks. SBSE was interested to understand whether public-facing behavioural advice is consistent across different sources, and whether there are contradictions across risks. If the risks occur simultaneously, conflicting advice could cause confusion among the public, increasing individual and societal risks during these periods.

Aims

-

Rapidly review current recommended advice in the UK on how to respond to extreme heat, drought and wildfire.

-

Identify areas of consistency and contradiction, and suggest ways advice can be amended or clarified to ensure greater consistency.

-

Explore how different national sources of warnings and advice are likely to be received at the same time and understood by the public and whether such materials and channels could/should be better coordinated.

-

Explore how local sources of advice & messaging (e.g. public health bodies, local government, fire & rescue services, water companies) can reflect local conditions within an overall national situation.

Project approach

The commissioning team shared known national and local resources with BR-UK for review. The authors then searched for additional resources, including those from 6 water companies across all 4 nations, as well as a selection of unitary authorities, London boroughs, county councils, and locally delivered fire and rescue services (see Annex B for the Sources List). Purposive sampling of sources was used to ensure coverage of key geographical areas across all 4 nations and to include a spread of messaging and advice types. This project does not constitute a comprehensive search or review of all available resources.

After collecting resources, the BR-UK team developed and applied an iterative framework to extract messaging from each. Once messages were extracted, they were grouped into higher-level behavioural advice and educational information categories using the large language model Claude Sonnet 4. These categories for each risk served as a codebook for coding the message datasets with Claude Sonnet 4. The team used R to analyse the consistency of codes across documents and sources within each risk. Claude Sonnet 4 was used to initially analyse the category codebooks and messages to detect potential consistency and contradictions within and across the weather risks. The research team reviewed each of the AI outputs for accuracy, relevance, and appropriateness based on their understanding of the datasets and the research aims. Please see Annex C for more information on methods, including the use of AI.

Consistency of advice within risks

Extreme heat

Extreme heat advice in the UK is commonly shared via websites of UKHSA, UK and devolved governments, the Met Office, and local authorities. We extracted 537 separate messages from 25 documents, including 20 readily available documents (e.g., permanent webpages, general heat advice) and 5 heat event-specific communications (e.g., heat warnings, news updates). Most messages (N=410 messages from 21 documents) contained behavioural advice or a combination of educational information and behavioural advice, while the remainder contained solely educational content. The type of content (behavioural vs. educational only) did not differ notably between readily available guidance and event-specific messages. The messages were mainly disseminated in text format through webpages, blogs and checklists. There were limited examples of short-form content (e.g. posters, social media posts).

Behavioural advice

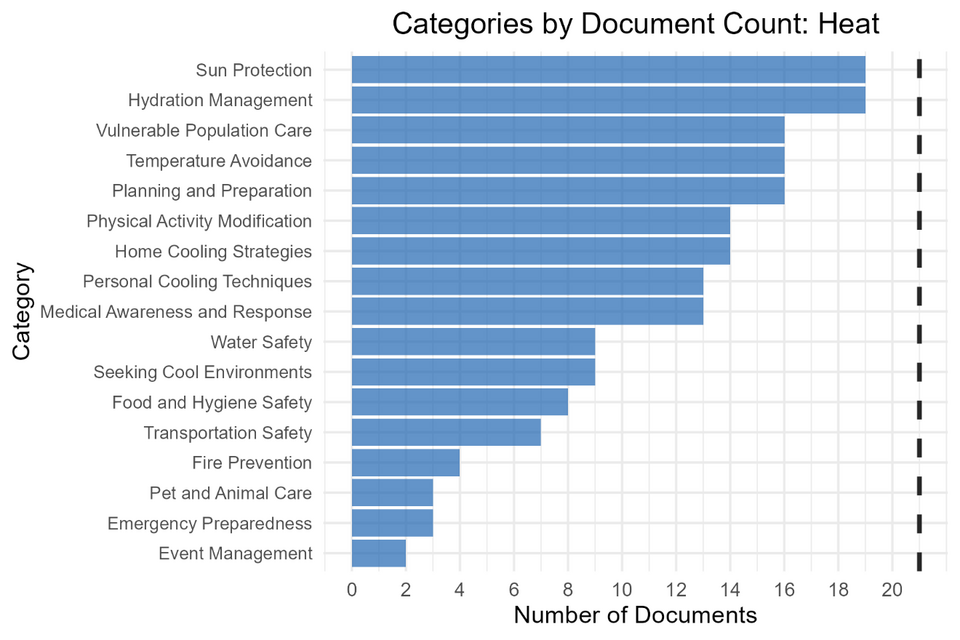

Seventeen higher-order categories for behaviours advised in extreme heat were identified by the BR-UK team. Figure 1 shows that 9/17 behavioural advice categories were included across more than half on the documents and by most organisations. Sun protection and hydration management were the most common across the documents, followed by guidance on vulnerable population care, temperature avoidance (e.g. seek shading between 11am to 3pm during the day) and planning and preparing (e.g. check weather forecasts and plan journeys ahead). The least frequently mentioned categories were fire prevention, pet and animal care, emergency preparedness (e.g. preparing for heat-related emergencies and power outages) and event management.

These 17 categories contain advice to perform several different but related behaviours. For instance, planning and preparing contains proactive measures such as checking weather forecasts, planning activities around heat, stocking supplies, and preparing homes/vehicles for hot weather.

While some behavioural advice seems generally applicable across most situations (e.g. hydration management), others are context specific, such as transportation safety.

Figure 1: The bar plot shows the number of documents containing at least 1 message regarding each behavioural advice category in extreme heat. The black dotted line denotes the total number of documents containing behavioural advice (N=21). See Annex D, Table A1. Behavioural Advice Categories – Heat, for the descriptions of each category.

Categories by Document Count: Heat

| Category | Number of documents |

| Sun protection | 19 |

| Hydration management | 19 |

| Vulnerable population care | 16 |

| Temperature avoidance | 16 |

| Planning and preparation | 16 |

| Physical activity modification | 14 |

| Home cooling strategies | 14 |

| Personal cooling techniques | 13 |

| Medical awareness and response | 13 |

| Water safety | 9 |

| Seeking cool environments | 9 |

| Food and hygiene safety | 8 |

| Transportation safety | 7 |

| Fire prevention | 4 |

| Pet and animal care | 3 |

| Emergency preparedness | 3 |

| Event management | 2 |

Consistencies and inconsistencies in heat-related messaging

In addition to the same behavioural advice consistently appearing across documents, the way the advice is communicated is also consistent. However, there were some variations in wording that affected clarity. For example, ‘avoiding hottest part of the day (11am–3 pm)’ versus ‘avoid heat’, or ‘wear sunscreen’ versus ‘wear a factor 30 SPF sunscreen’. Such differences are common and often reflect changing from long to short form messaging mediums.

Inconsistencies in the communication of behavioural advice across documents include:

-

Unclear guidance on when opening windows may become counterproductive due to high outdoor temperatures;

-

Conflicting messages about cold water, warning about cold water shock in swimming but also recommending cold water for cooling, which could confuse people;

-

Inconsistent guidance on electric fan use, with some messages specifying temperature limits (e.g. “use electric fans if air temperature is below 35°C”) and warnings against directing fans at the body, while others simply suggest fan use without detail. There is no advice for scenarios where air temperature exceeds 35°C, such as could occur in a poorly ventilated, inner city, top floor apartment.

Educational messages

Educational messages were grouped into ten categories, covering information about a variety of topics, such as who is vulnerable during extreme heat, types of housing at high risk of overheating, and how to recognise heat-related illness (see Annex D for full details). Depending on the purpose of the resource, the breadth of educational advice available varies.

One prevalent inconsistency in educational messages is the age threshold for vulnerable older populations. Some messages state, “65 years and over” while others mention “75 years and over”, which could create confusion if people receive such risk communication from different sources, and potentially risk leaving certain populations unprotected.

Annex D contains more detailed descriptions of the behavioural advice (Table A1) and educational message (Table A2) categories and additional figures on the consistency of advice across sources and documents (Figure A1 -A4).

Recommendations

-

Clarify window opening/closing advice: Provide specific temperature thresholds or conditions for when to open versus close windows (e.g. “open windows when outdoor temperature is cooler than indoor temperature”).

-

Standardise fan usage advice: Advice should include the 35°C temperature threshold (“Do not use electric fans when indoor temperatures exceed 35°C”) and where possible (e.g. in longer format content) explain why this threshold exists. Provide alternative cooling strategies for air temperatures above 35°C, such as seeking cooler environments. Provide warning about not aiming fans directly at the body to prevent dehydration. Additional fan use strategy can be provided, such as using fans to enhance cross-ventilation by placing them near open windows or doors, but only if the outside air is cooler than inside.

-

Clarify cold water shock advice: Clarify that cold water shock warnings apply to full-body immersion in very cold water, not gradual cooling applications.

-

Clarify vulnerable age groups: Make a consistent, evidence-based recommendation of the age groups that face a higher risk of heat-related illness.

-

Integrate cooking guidance: Provide advice about indoor vs. outdoor cooking during extreme heat that balances fire safety with avoiding indoor heat generation. For instance, advice on barbecue safety and restrictions from wildfire messaging should be integrated.

-

Summarising recommendations: When summarising advice for short-form communications, ensure the details that are kept are those most relevant to behaviours being advised and that they don’t lose clarity after being summarised. Keeping more detailed components of advice could be incorporated through means other than text, e.g. “wear sunscreen” messaging alongside an image of a 30 SPF sunscreen bottle.

-

Prioritisation and contextualisation of advice: To aid understanding, the most important general behaviours should be emphasised in documents for the public, and it should be made clear when advice relates to a specific context or scenario. Separating out general from context-specific advice can also help guide decisions about whether a short communication (for example a poster) or a longer format (for example a guidance checklist) is most appropriate.

Drought

Drought advice in the UK is typically shared via text-focused websites of government departments and agencies, and water companies (see Annex B for the full list). More than 400 (N=403) messages from 31 (of 35) documents were reviewed. There were 25 readily available documents (e.g. permanent web pages, drought planning documents, guidance documents, communication toolkits and strategies, policy paper) and 10 drought event-specific documents (e.g. new stories, press releases, blogs). Most messages (N=290 messages, 29 documents) contained behavioural advice or a combination of educational information and behavioural advice, while the rest contained solely educational messages. The type of content (behavioural vs. educational only) did not differ notably between readily available and event-specific materials. Drought reports and communication plans, blogs and social media were most used to disseminate these messages, while policy brief is the least used medium.

Behavioural advice

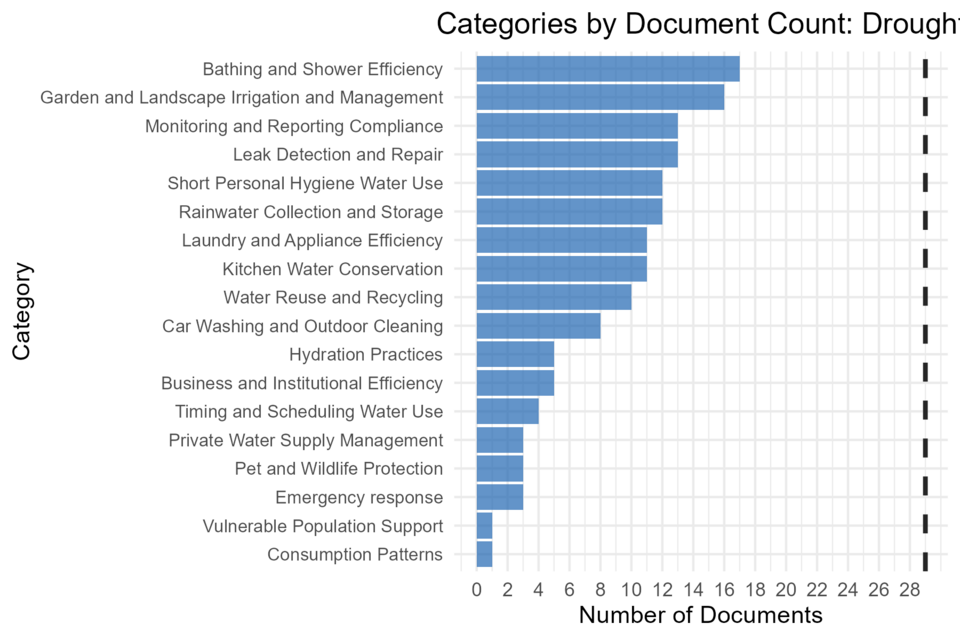

Advice generally addresses water shortage risks for the public and primarily focuses on water conservation behaviours, such as reducing water use for bathing and showering (e.g. bathing and shower efficiency – switching from baths to shower and shortening shower time) and shortening personal hygiene water use (e.g. turning off taps while brushing teeth) (see Figure 2). Some advice focuses on reusing water such as collected and stored rainwater for garden and landscape irrigation and management (e.g. installing water butts); and avoiding waste through monitoring and reporting water compliance and detecting and repairing leaks (e.g. repairing taps, pipes, and toilets for leaks).

Figure 2. The bar plot shows the number of documents containing at least 1 message regarding each behavioural advice category in drought. The black dotted line denotes the total number of documents containing behavioural advice (N=29). See Annex D, Table A3. Behavioural Advice Categories – Drought, for the descriptions of each category.

Categories by Document Count: Drought

| Category | Number of documents |

| Bathing and shower efficiency | 17 |

| Garden and landscape irrigation and management | 16 |

| Monitoring and reporting compliance | 13 |

| Leak detection and repair | 13 |

| Short personal hygiene water use | 12 |

| Rainwater collection and storage | 12 |

| Laundry and appliance efficiency | 11 |

| Kitchen water conservation | 11 |

| Water reuse and recycling | 10 |

| Car washing and outdoor cleaning | 8 |

| Hydration practices | 5 |

| Business and institutional efficiency | 5 |

| Timing and scheduling water use | 4 |

| Private water supply management | 3 |

| Pet and wildlife protection | 3 |

| Emergency response | 3 |

| Vulnerable population support | 1 |

| Consumption patterns | 1 |

Few messages addressed health-related risks such as dehydration, the spread of water- and food-borne diseases, mental health conditions (e.g. stress, anxiety), and physical health. There was also limited actionable advice aimed at occupational/recreational (e.g. farming, fishing) or vulnerable groups. Messages on the provision of opportunities or support for water conservation behaviours in the reviewed documents may be limited in their effectiveness because they do not link to advice on how to source or fund adaptations needed for these behaviours; this is especially challenging for those without the immediate means to do so. Examples of such behaviours are installing water butts, investing on dishwashers and washing machines with eco mode functions, fitting of cistern devices, and plumbing maintenance.

Educational messages

Drought education messages were categorised into 14 categories covering topics from climate-drive water scarcity, water infrastructure capacity, and impact on vulnerable populations (see Annex D for full details).

The most frequently occurring education content focused on water consumption patterns, explaining usage trends, comparative statistics, and consumption baselines (i.e. “150 litres every day”) that underpin public understanding of water demand. This was closely linked with messages on seasonal demand dynamics and water scarcity causes, forming a consistent narrative how climatic shifts (e.g. shifting season norms and unpredictability in rainfall; hotter and driers summers) are contextualised within household and sectoral water use. Messages on consumption (e.g. “150 litres of water are used per person per day”) and seasonal dynamics (e.g. 25% increase in water demand during dry season) were consistently emphasised across documents and sources, reinforcing water conservation behaviours.

Consistencies and inconsistencies in drought-related messaging

Most drought-related behavioural recommendations are consistent and complementary to each other. Advice for drought shows strong consistency across most categories of actionable advice.

Areas of consistent advice include:

-

Suggested use of water-saving tools across all outdoor activities (e.g. gardening, landscape irrigation, car washing, outdoor cleaning) such as using watering cans over hoses, or buckets over running water;

-

Guidance on optimal timing recommendations for garden watering techniques such as “watering in the early morning or evening to reduce evaporation”;

-

Promoting and maintaining health while implementing water efficiency measures, especially on essential health needs such as “staying hydrated”, “keeping to hygiene standards”, and “using clean water for cooking”;

-

Promoting efficient uses of water-consuming appliances in residential, public, and commercial settings such as using “eco-settings” across all appliances; leak prevention, more specifically on preventing, detecting, and repairing sources of leaks or systems and equipment that is at risk for water waste; and

-

Alternative water sources, specifically on using rainwater, greywater, and other alternative water sources rather than freshwater supplies for non-essential uses, to preserve treated water for essential needs.

Based on the heatmap in Figure A6, there are some examples of inconsistency in the main themes of drought-related messages across all information sources, which may imply a lack of coordination across different national and local level organisations. While some behavioural advice categories (e.g. bathing efficiency or garden irrigation) are covered by certain organisations, other organisations (e.g. Environment Agency, Natural Resources Wales, UKHSA) have limited coverage of these. Some sources focus on specific categories, while others distribute messages more broadly but without alignment.

While the messages use directive language, they frequently fall short of providing clear, contextualised, and actionable guidance necessary for effective public understanding. The use of vague language (e.g. “try”, “help”, “encourage”) has the potential to weaken behavioural directives, while unclear or incomplete advice (e.g. “small adjustments”, “water saving tips”) lacks the specificity needed to support action. Although many messages appear instructive (e.g. “turn off the tap”, “use eco mode setting”), some messages are often conditional (e.g. “consider installing a water butt”), and don’t explain why the behaviour matters. Some present a range of recommended actions without prioritisation, which could leave recipients of the messages uncertain about which behaviours are most important or urgent.

There are also some contradictions in message categorisation. For example, health and environmental impacts are sometimes described using the same wording, even though they related to different issues. 1 message, for instance, urges the public to “help preserve water supplies and the natural environment” without clarifying whether the priority is environmental protection or health-related water security. Another message highlights the benefits of water efficiency in businesses, such as “cost-savings,” “environmental compliance,” and “enhanced reputation,” without distinguishing the regulatory, environmental, or health rational behind them.

Annex D contains detailed descriptions of the behavioural advice (Table A3) and educational message (Table A4) categories and additional figures on the consistency of advice across sources and documents (Figure A5 - A8).

Recommendations

1.Distinguish and clarify advice on personal health needs from water conservation measures for homes and businesses.Clearly separate advice between essential (e.g. hydration and personal hygiene) and non-essential water uses for homes and businesses (e.g. garden irrigation). This will avoid confusion and prevent unintended health risks. For garden management and irrigation, consider introducing a simple decision tree to guide household garden watering practices, clearly identifying when to use stored rainwater, when to delay watering based on the time of the day (e.g. watering plants in the morning during cooler temperature for less evaporation) or when rain is expected, and when to adopt stricter conservation measures.

2.Strengthen connection between related water conservation behaviours.Make explicit connections between interdependent behaviours, such as linking leak detection guidance across all relevant water use efficiency categories. Consider sequencing recommendations by presenting actions in a logical implementation order (e.g. assess water use and fix leaks and adopt efficiency measures a monitor) to help the public understand system-wide water-saving practices.

3.Standardise terminology for equipment and practices. Ideally use clear and more direct language that has been pre-tested across all message categories.

Wildfire

Wildfire advice is commonly shared by local and national fire and rescue services, government campaigns (e.g. UK Prepare, Ready Scotland), and the Forestry Commission (See Annex B for full list). We extracted 269 messages from 13 documents, which (in their current form) includes 8 readily available guidance documents (e.g., permanent webpages), and 5 time and event-specific communications (e.g., social media posts, news articles). Most messages were text based, often accompanied by photos from recent wildfires rather than infographics or images demonstrating desired behaviour. Messages were disseminated on dedicated webpages, with a considerable number of social media posts (on Twitter/X) from local fire and rescue services. The majority of the messages (N=211) contained behavioural advice either on its own or combined with educational information, while the remainder (N=58) contained educational information only.

Behavioural advice

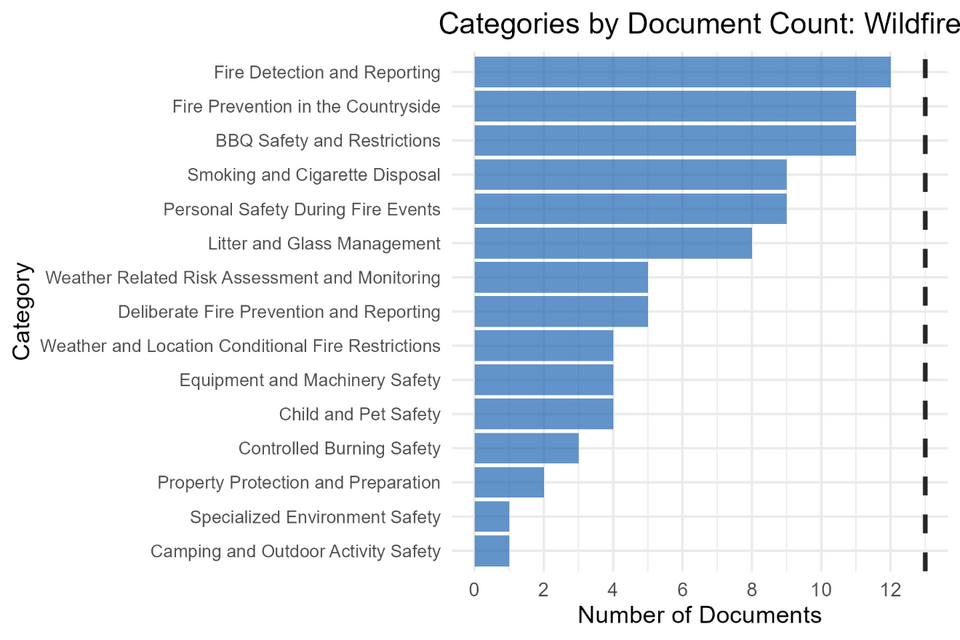

Behavioural advice regarding wildfire prevention, reporting, and other actions included in the documents were grouped into 15 higher-order categories (see Figure 3). There was variety in the coverage of categories across sources, with only 6 out of 15 behavioural advice categories being included in at least half of the documents analysed. The most common behavioural advice across the documents were relating to fire detection and reporting (e.g. immediate actions like calling 999, providing location and other detailed information to emergency services) and safe use of barbecues (e.g. safe setup distances from structures, proper fuel use, complete extinguishment procedures as well as advice for not using barbecues at all during high-risk conditions). These were followed by advice on fire prevention in the countryside, personal safety during fire events, and disposal of cigarettes, glass and other litter.

Figure 3: The bar plot shows the number of documents containing at least 1 message regarding each behavioural advice category in wildfire. The black dotted line denotes the total number of documents containing behavioural advice (N=13). See Annex D, Table A5. Behavioural Advice Categories – Wildfire, for the descriptions of each category.

Consistencies and inconsistencies in wildfire-related messaging

There were considerable consistencies in the content of behavioural advice and educational messages related to wildfire across categories and documents.

Areas of consistent advice and messages include:

-

Checking weather conditions and avoiding fire activities during high-risk periods.

-

Proper disposal of potentially fire-starting materials (cigarettes, glass, litter).

-

Being vigilant about deliberate fire-starting activities and reporting instances to the right authorities.

Annex D contains more detailed descriptions of the behavioural advice (Table A5) and educational message (Table A6) categories and additional figures on the consistency of advice across sources and documents (Figure A9 - A12).

While there were no major inconsistencies detected across wildfire messages, there were some issues of clarity, mainly relating to the hierarchy of advice and restrictions and the definition of different types of fires. The recommendations below may help to improve the clarity of behavioural advice and educational messages related to wildfire.

Educational messages

Educational messages related to wildfire were grouped to 9 higher-order categories including characteristics and causes of wildfires, geographic and weather-related risk conditions for wildfires, socioeconomic and environmental impacts of wildfires, wildfire risk assessments and related restrictions, and information on fire and rescue services and their activities (see Annex D for full details). These messages showed high levels of internal consistency across different documents and sources.

Recommendations

1.Clarify the geographical and conditional boundaries for permission and restriction of behaviours to prevent wildfires. Define what constitutes countryside where stricter restrictions apply versus other outdoor areas where some fire-related activities can take place under safety guidelines.

-

Improve the definition and terminology related to different types of fires. For example, clarify whether “open fires” include campfires and bonfires; define controlled burning in residential and agricultural contexts.

-

Establish a hierarchy of restrictions.Clarify whether and when local fire bans override general guidance, weather conditions override seasonal permissions, etc. Signpost clearly where individuals can best find out about this information (alerts, websites, calling local authorities, etc.).

-

Help individuals seek out and understand risk assessments.Simplify access to information regarding risk assessments and warnings related to risk of wildfires. Consider experimentally testing guidance on integrating multiple risk factors (weather, location, fire type, personal capability) into decision-making with the public.

Contradictory advice within and across risks

Across risks

In all 3 risk contexts, integration that considers concurrent risks is uncommon in the messaging. Communication documents offer limited actionable guidance for managing multiple hazards at once. We identified 2 main contradictions in our analyses comparing the behavioural advice messages across all risks (N=906 messages):

Water resource management

Extreme heat messages most frequently advise maintaining hydration but lack guidance on water conservation amid drought risks. Drought messages advise maintaining hydration and conserving water but lack guidance on how to balance this competing advice. For example, advice to reduce bathing frequency or take shorter showers may contradict the need for more frequent washing during hot weather, especially when the advice is not paired or contextualised with extreme heat advice. If both risks co-occur, people exposed to both extreme heat and drought messaging may be confused about which advice to prioritise to manage water resources.

Wildfires need water for suppression, but there is no guidance or prioritisation framework addressing the competing demands to “save water” and “take cool showers”, for example.

Indoor/outdoor activity advice

Advice related to engaging in activities may be contradictory if both wildfire and extreme heat coincide. Extreme heat messages often advise people to stay indoors if it is cooler than outdoors. However, during wildfires, indoor environments might not be safe and extreme heat messages may contradict the need to evacuate. Wildfires can also cause polluted air outdoors, making it unsafe for people to open windows to ventilate their homes during cooler periods of the day to mitigate extreme heat indoors.

Within risks

Extreme heat

We found no contradictions across the behavioural advice within extreme heat messages and therefore don’t include here any recommendations for alignment. However, this review is based on a non-complete set of resources, so these may appear in others not reviewed.

Drought

The following contradictions in drought messaging were identified:

-

There is a tension between hygiene and water conservation. While people are advised to maintain personal hygiene, this can conflict with efforts to reduce water use, especially if interpreted as continuing pre-drought hygiene routines.

-

Guidance on greywater reuse raises safety concerns, as it may blur the lines between environmental sustainability and health protection, particularly regarding the risk of water- and food-borne diseases.

Recommendations

-

Balance health protection with water conservation. Drought messaging should clearly distinguish between essential and non-essential water use. Guidance should prioritise health-critical needs (e.g. hydration and hygiene) and encourage people to continue engaging in these behaviours, while identifying areas where water use can be reduced safely.

-

Define and clarify hygiene and safe water standards.Guidance should clarify “maintaining hygiene standards” in water-scarce conditions, including specifying essential hygiene behaviours (e.g. handwashing before eating, after toilet use) versus adaptable behaviours (e.g. frequency and length of showers). Safety messaging should clearly identify which types of greywater are safe for reuse (e.g. from showers or laundry) and for what purposes (e.g. garden irrigation).

-

Establish a water use priority hierarchy.Messaging should offer a clear order of priority for water use that is simple, intuitive and repeated consistently across all communication materials, covering essential health needs (hydration of self and others, including animals), basic hygiene (handwashing, limited showering), and other uses (cleaning, gardening).

Wildfire

A contradiction in wildfire messages was identified between behavioural advice that allows outdoor fires in certain contexts versus advice that prohibit all fires, regardless of conditions. This is particularly relevant to barbecue and campfire use advice. Contradictions tend to emerge between general guidelines from national sources versus time, weather, and location-sensitive advice from local fire and rescue services.

For example, Fire England’s webpage [W3] advises using barbecues in “designated areas of the countryside and follow safety”, which echoes messaging from Ready Scotland [W5] which advises individuals “Only have a barbecue within safe designated areas outdoors”. This contradicts advice, for example, from the Forestry Commission [W8.4] which states, “Follow the Countryside Code and never light open fires, such as campfires or barbecues, in the countryside”, from Surrey Fire & Rescue Services [W8.16] which asks people to “swap barbecues for picnics and avoid open fires” and from the West Yorkshire Fire and Rescue Service which encourages individuals to ‘never be tempted to light a fire in the countryside and only barbecue in authorised area’.

While most sources advise that the public should not attempt to put out fires, but instead report to fire and rescue services immediately, some sources recommend cautious intervention. The contradictions centre around what types of fire (e.g. a campfire or a fire lit in the backyard of a home versus a fire that is in the countryside or in a woodland area) and whether different levels of personal interventions can be appropriate under different circumstances and locations.

For example, Fire England [W3] asks individuals to “not attempt to tackle fires that cannot be put out with a bucket of water – leave the area as soon as possible” and states “if in doubt, don’t fight a fire yourself. Get out, stay out and wait for the fire and rescue service”. Ready Scotland [W5] on the other hand states that individuals “should only try to extinguish a fire if you have suitable means of extinguishing it and are confident that you are able to do so safely”, while Northern Ireland Water [W7] clearly asks people to “not attempt to intervene or fight fires under any circumstances”.

Recommendations

-

Clarify the scope of prohibitions. Specify whether countryside fire prohibitions apply to all fires or only to unauthorised/recreational fires. Indicate whether there are exceptions for designated camping areas. Clarify whether prohibitions are weather and location dependent or if they are blanket bans.

-

Resolve conflicting advice regarding individual fire response. Provide clear guidelines on whether individuals should try to fight fires before reporting to fire and rescue services and distinguish between types of fire that could be fought (e.g. campfires, fires in the backyard of a home) versus those that should be reported immediately (e.g. fires in the countryside). Do not use subjective language such as “if you are in doubt” or “if you feel confident” when describing a situation where personal intervention could be appropriate.

Concurrent risks

Few resources were identified that guide public behaviour during periods of concurrent extreme weather risks. In the context of drought and extreme heat, messaging is unclear, e.g. not distinguishing between drought and extreme heat and how they are related. Messaging is also not contextualised in terms of cooccurring risks and lacks clear prioritisation or integration of recommended behaviours when multiple risks occur simultaneously.

Recommendations

An integrated framework of what advice to give during concurrent weather risks should be developed for national and local use. Within this, the following issues could be helpfully clarified by helping the public prioritise behaviours where contradictory advice exists:

1. Create clear hierarchical prioritisation of behavioural advice to use during concurrent weather risks for:

-

Water use and resource management. Establish minimum allocations for life-safety (e.g. hydration, fire suppression) vs. comfort cooling.

-

Indoor/outdoor activities. Create explicit priority hierarchies that guide what behavioural advice is best for public health and safety (e.g. fire risk overrides heat management when both are severe).

2. Modify public advice for emergency response to explicitly address concurrent weather risk scenarios.

3. Develop integrated and coordinated communication guidance across all 3 weather risks that provides clear recommendations for local use on how to assess people’s relevant knowledge, skills, and opportunity and to offer support in preparation for concurrent weather risks.

Overall considerations on how messaging, guidance and advice is likely to be received by the public

Public guidance for extreme weather conditions in the UK displays several gaps when assessed against risk communication best practice criteria. We analysed the strengths and weaknesses of the messages within each risk (see Table 1) using the WHO and other relevant criteria for evaluating risk communication in public health emergencies and extreme weather conditions (World Health Organisation, 2017; MacIntyre et al., 2019), to gauge if the existing messages could be effectively received by the public.

Most messages provide behavioural advice without explaining the rationale or potential consequences. Research shows that impact-based warnings that incorporate weather event information, potential impacts, and behavioural advice are more effective (Shin et al., 2022; Weyrich et al., 2018). For example, “Drink plenty of water” is less effective than “Drink plenty of water because dehydration increases risk of heat stroke.” Enabling changes in people’s habitual behaviours that form part of people’s stable daily routines (e.g. what people drink and how they wash) is difficult to achieve through messaging alone (Verplanken & Orbell, 2022; Albarracín et al., 2024). It may be helpful to focus on helping people to set intentions for particular situations, such as incorporating if-then plans, in the form of “If I am in the situation X, then I will Y” (Bieleke et al., 2021).

Research demonstrates that weather warnings incorporating behavioural advice increase intentions to engage in protective behaviours during extreme weather conditions (Heidenreich & Thieken, 2024), indicating the need for behavioural advice in emergency weather warnings. Few of the reviewed documents make use of social media, print, radio, television, and other communication channels. Social media is a proven tool for real-time public engagement during extreme weather events (Sadiq et al., 2023), and so this could also be used during emergencies.

Most advice in the reviewed documents was provided in English only, with very limited multi-lingual accessibility (only appearing in a few national sources) and lacked specific guidance for vulnerable and isolated populations. This is a key gap, especially given that isolation exacerbates negative health effects during crises (Kung & Steptoe, 2024). Vulnerable groups require clear, targeted guidance tailored to their needs. It is important to consider how to tailor advice according to contexts, and relevance for different populations. Being selective and prioritising relevant types of actionable advice for specific groups can prevent overwhelming the audience with an extensive list of actions. Some actions may be more relevant, and therefore usefully targeted, for different groups. For example, vulnerable groups need tailored messaging and potentially message delivery via intermediary communicators as they may not have direct access to the common risk communication channels and languages (McLoughlin et al., 2022).

Most research on extreme weather communication focuses on influences on behaviour, such as attitudes or intentions, with little on how to achieve sustained behaviour change. Addressing these gaps requires implementing impact-based messaging, establishing timeliness protocols, adopting multi-modal strategies, producing multi-lingual and equity-oriented guidance, and developing evaluation metrics that measure protective behaviours over time.

The volume of advice and guidance provided in a single resource may pose a problem for the public. Many of the documents reviewed were lengthy and unlikely to be read in full by most people. When people attempt to set multiple behavioural goals or intentions, these are less likely to lead to behaviour change than when 1 or 2 are set (Bieleke et al., 2021). Communicating a large amount of information can also reduce the effectiveness of messaging, especially for vulnerable groups (Lambert et al., 2025).

Table 1. The matrix shows a summary of strengths and weaknesses of public advice for extreme weather conditions in the UK.

| Criteria for Effective Risk Communication* | Extreme heat | Drought | Wildfire | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transparency | Weakness: Most messages do not explain the rationale behind recommended behaviours or the link between these components is limited (e.g. across different pages). There is also a lack of information on what temperature might constitute extreme heat. | Weakness: Most messages do not explain the rationale behind recommended actions. | Weakness: Many messages do not explain the rationale behind fire bans or specific thresholds for activity restriction procedures. | ||

| Clarity and comprehensibility | Strength: Most behavioural advice is written in plain, accessible language. | Strength: Messages on protective actions and conservation are often conveyed in clear, simple, and instructive language, making them accessible to wide audience. Some messages adopt a more cautious or general phrasing, allowing for flexibility and broad applicability across contexts. | Strength: Core protective actions are conveyed using simple and direct language, however increased clarity is needed for terminology relating to types of open fire and natural areas. | ||

| Timeliness and relevance | Weakness: Most messages within static webpages or documents and it is unclear from these when and how this advice will be disseminated. | Strength: Messages acknowledge current drought conditions and seasonal water usage patterns. | Weakness: Messages lack prioritisation between general guidance and weather and location specific actions which may hinder decision-making under time pressure. | ||

| Acknowledgement of uncertainty | Weakness: Few messages explain the evolving nature of extreme heat risks such as the temperatures when this advice becomes relevant or the additional risk of concurrent risks such as drought and heat. | Weakness: There is little to no mention of limitations, evolving risk conditions, or uncertainty. | Weakness: Fire risk measures generally do not explain how risk levels are determined or updated, nor do they communicate uncertainty in forecasts and emergency response. | ||

| Multi-lingual accessibility | Weakness: There is little indication of translation into multiple languages or adaptation to low-literacy or culturally diverse audiences. | ||||

| Multi-modal delivery | Weakness: While messages are disseminated across multiple platforms (e.g. websites, social media, videos), most of these are static. Based on the reviewed documents, there was limited indication of how the messages could be adapted in other formats for prints, radio, television, etc, except in one national source on extreme heat where such communication guidance was provided, and 2 sources on wildfire that mocked up potential social media posts. While actual implementation was not assessed, reviewed drought communications plan provided guidance on how traditional media (e.g. television, radio) and other communication channels (e.g. text messages, press releases, leaflets, letters) will be used to deliver advice at each stage of drought. | ||||

| 2-way engagement | Communication is predominantly top-down and one-way, with limited visible mechanisms for feedback. | ||||

| Source credibility | Strength: Guidance is consistently issued by trusted national and local organisations | Strength: Most messages originate from government agencies and local water utilities in England and Wales. In Scotland, advice is from Scottish Water. | Strength: Guidance is consistently issued by trusted national and local organisations. | ||

| Evidence-informed content | Strength: Practical advice suggests evidence on protective actions during extreme heat. | Strength: Specific water usage statistics are provided with references to water utility duties and regulatory requirements. | Strength: Messages appear to be based on established fire safety principles (e.g. proper cigarette disposal, barbecue safety, etc.) | ||

| Actionability | Strength: Messages offer specific actions that can be easily implemented. | Strength: Many messages contain clear, directive language. | Strength: Advice is generally action-oriented, offering specific behavioural instructions. | ||

| Protective framing | Strength: Messages prioritise public health and safety. | Strength: Guidance aligns with the goal of protecting public and environmental health. | Strength: Many messages are focused on protecting life and property, fire prevention, and personal safety. | ||

| Equity and vulnerability sensitivity | Weakness: While vulnerable groups are mentioned, but messages often lack tailored advice for specific needs. | Weakness: Messages rarely address the situational constraints of vulnerable groups, nor do they tailor advice accordingly. | Weakness: Messages rarely account for the needs of vulnerable people and at risk groups. | ||

| Inclusivity and cultural relevance | Weakness: Limited consideration of different cultural practices around heat management. | Weakness: There is limited evidence of content designed for people with different literacy levels, languages, or cultural contexts. | Weakness: Limited cultural adaptation or recognition of different cultural practices and traditions around fire use. | ||

| Message framing and relevance | Weakness: Many messages lack contextual framing that links actions to broader outcomes. | Weakness: Messages often lack prioritisation of behaviours and urgency framing. | Weakness: Some messages focus on negative consequences without balancing with positive action framing. |

*WHO (2017), Macintyre et al (2019)

Further work is needed on effective ways to communicate behavioural advice concisely without sacrificing clarity in short-form messaging. How advice is framed can also affect public perception of each risk and hence their subsequent actions. For example, loss framing (e.g. presenting information by highlighting the potential negative outcomes or loss if the action is not taken), is often used to promote pro environmental and health behaviours (Homar and Cvelbar, 2021; Bosone and Martinez 2017). The effectiveness of these strategies depends on people’s psychological characteristics. For instance, promotion-focused individuals, driven by growth and aspirations, respond best to messages that highlight potential gains, while prevention-focused individuals, motivated by avoidance of negative outcomes, are more influenced by messages that stress potential losses or the dangers of inaction (Higgins, 1997). More generally, public perceptions of weather risk messaging are under-researched, and so it is important to consider future primary research exploring, and empirically testing, how these messages are received to guide improved messaging.

Recommendations

-

Ensure targeted, inclusive, and culturally relevant messaging. Tailor messages to specific groups (e.g. older adults, low-literacy populations) using local languages, cultural references, and relevant examples. Where appropriate, incorporate images alongside text to improve accessibility and comprehension, supported by clear guidance on image use.

-

Use clear, actionable, and context-sensitive communication. Provide simple, specific, and feasible instructions ground in local realities. Enhance behavioural uptake by including implementation prompts such as “if-then” statements to help adapt actions to people’s own contexts.

-

Establish credibility through trusted and coordinated sources. Attribute messages to trusted institutions or experts, using consistent branding and voices that are authoritative in relevant communities. Strengthen impact through coordination of materials and messaging channels to prevent confusion and fragmentation.

-

Deliver timely messages through multiple, accessible channels. Disseminate messages early and repeatedly using coordinated mix of accessible formats (e.g. SMS, radio, social media, visual materials) to reach diverse and underserved audiences.

-

Test, monitor, and adapt communication strategies. Pre-test messages particularly short-form advice and visual formats with target audiences to assess clarity and personal and local relevance. Establish feedback loops and impact monitoring systems to continuously refine content, tone, and delivery.

Local messaging, advice and guidance considerations by risk

Extreme heat

Most public facing messages, guidance and advice communicated by local sources for each of the individual risks were consistent with the messages communicated by national or general sources across all risks. For instance, Tower Hamlets Council [E24] had a comprehensive coverage of most recommendation categories similar to the national sources in coping with extreme heat. However, there are differences in messaging content between national and local authorities. Extreme heat recommendations varied across local councils, for example, Edinburgh [E23] had limited advice on hydration and sun protection, while Monmouthshire [E21] lacked guidance on vulnerable populations, and Hammersmith and Fulham Council [E20] prioritised a reminder to check on homeless population in the area. There were also recommendations that were inconsistent across both national and local sources. For example, not all extreme heat-focused national sources mentioned seeking cool environments, energy preparedness (e.g. power outages) and fire prevention.

There were examples of consistent messaging being shared and framed in the local context, which are likely to be particularly effective. A good example is the guidance for staying safe for attendees at Glastonbury Festival by the Somerset Council that was circulated in advance [E19]. Amber heat health alert and weather forecast for the festival were mentioned, with brief behavioural recommendations including hydration and sun protection, and information on signs and symptoms of heat illnesses. Another example is the suggested cool spaces and water foundations for refills in local areas by Hammersmith and Fulham Council [E20], offering details relevant and accessible to the local population, instead of simply stating “seek cooler environment” and “stay hydrated”.

Drought

Many drought-related messages supported enhancing general awareness and offer water-saving tips, but few fostered a deeper understanding of local drought risks or the underlying rationale for behaviour change. Skills-based behaviours, such as actions on installing water butts or identifying leaks, are insufficiently addressed. Local opportunity and resources to enable appropriate changes in behaviour are often assumed, with no information as to how to access them or attention to infrastructural inequalities across housing types or communities. Some messages are aimed at increasing motivation as well as knowledge and skills: ideally messages would aim to increase knowledge and skills (capability), resources to enable change (opportunity) and motivation for the desired behaviour. The limited contextual and behavioural adaptation of these messages weakens their potential for effective risk communication and sustained water-saving behaviours.

Drought-related messaging across UK water utilities has a high degree of uniformity, with content largely homogenised across geographic regions. The messages focus predominantly on generic water-saving behaviours (e.g. taking shorter showers, turning off taps, or using water butts), with little to no tailoring to regional water supply contexts, vulnerabilities, or sociodemographic factors. Nearly all messages target the general public without segmentation by geographic locations, socioeconomic status, or household type. Few messages reference to specific settings. For example, Waterwise provides specific guidance for general settings such homes [D10], schools [D11], workplaces [D12], while Scottish Water offers similar guidance (e.g. “Waste less water”) for hospitality and beauty businesses [D20]. Place based framing is limited, with exceptions like “Don’t let the Skye go dry” [D22] offering emotional or local meaning. While messages emphasise water conservation behaviours, these are not often linked to localised water stress indicators or community narratives, thereby limiting personal relevance. Messages lack the local anchoring which may help enhance behavioural relevance or create a sense of place-based responsibility.

A 6-stage process (1-Normal Operation; 2-Developing Drought; 3-Drought; 4-Severe Drought; 5-Emergency Measures; 6-End of Drought) is evident across sampled drought communication plans of UK water utilities [D26, D29, D30, D33, D34, D35]. This framework structures the dissemination of key messages, matching content, audiences, and communication channels with the severity of drought conditions. For example, South Staffs Water [D33] and Welsh Water [D34] adhere closely to this framework, escalating from routine water efficiency messaging to more urgent appeals and formal restrictions as drought conditions intensify. However, the content of key messages remains largely standardised. Messaging tends to focus on individual responsibility and water-saving tips, and the tone remains predominantly informative and directive, relying on increased frequency and urgency. The final stage (e.g. post-drought) focuses on lifting restrictions but offers no clear plan to sustain the behavioural gains achieved during drought.

Wildfire

There were differences in advice regarding lighting outdoor fires for wildfire prevention given by national sources and local fire and rescue services. For example, while Northumberland [W8], Devon & Somerset [W11], and West Yorkshire [W12] fire and rescue services explicitly communicate that no barbeques or campfires should be lit in the countryside or moorlands, general guidance from England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland all state that barbeques and small fires can be lit in designated areas within the countryside.

Based on the heatmap in Figure A10, local sources varied in their coverage of different categories of messages. For example. Devon & Somerset [W11] and Surrey Fire and Rescue Services [W9] communicated behavioural advice relating to property protection and preparation, while Dorset & Wiltshire Fire and Rescue Services [W8.12-13] mentioned camping and outdoor activity safety, and Lincolnshire Fire and Rescue Services [W8.19-22] focused on weather and location conditional restrictions. These variations may reflect different priorities and concerns of local services.

Conclusion

Public-facing guidance on extreme heat, drought, and wildfire in the UK is largely consistent within individual risks, particularly in promoting protective actions such as sunscreen application, hydration, hygiene, water conservation and fire prevention. Some contradictions and inconsistencies emerge when messages for concurrent risks intersect, such as the tension between conserving water during drought and body cooling during extreme heat. These may be exacerbated by unclear language, limited contextualisation, and a lack of prioritisation across multiple recommended behaviours. There was also limited advice for vulnerable populations, and few documents used pictures to support their messaging, which evidence suggests is effective at capturing attention, communicating complex information simply, and aiding memory.

To address these challenges, messaging should move beyond single-risk frameworks toward an integrated, multi-risk communication strategy. This includes harmonising guidance across concurrent risks, clearly framing behavioural trade-offs, and explicitly prioritising actions where conflicts arise. Advice statements, where possible, should be tied to specific behaviours and explanations for advice should be given. Some messages are aimed at increasing motivation as well as knowledge and skills. Ideally messages would aim to increase knowledge and skills (capability), resources to enable change (opportunity) and motivation for the desired behaviour.

Communication strategies should expand in range from documents to multi-modal and multi-lingual formats, with tailored guidance for high-risk vulnerable populations. Improving the consistency and alignment of public messaging is essential to increase comprehension, trust, and protective action during increasingly frequent and compounding extreme weather events in the UK.

References

Albarracín, D., Fayaz-Farkhad, B., & Granados Samayoa, J. A. (2024). Determinants of behaviour and their efficacy as targets of behavioural change interventions. Nature Reviews Psychology, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44159-024- 00305-0

Bieleke, M., Keller, L., & Gollwitzer, P. M. (2021). If-then planning. European Review of Social Psychology, 32(1), 88–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/10463283.2020.1808936

Bosone, L., & Martinez, F. (2017). When, how and why is loss-framing more effective than gain- and non-gain-framing in the promotion of detection behaviors? International Review of Social Psychology, 30(1). https://doi.org/10.5334/irsp.15

Heidenreich, A., & Thieken, A. H. (2024). Individual heat adaptation: Analyzing risk communication, warnings, heat risk perception, and protective behavior in three German cities. Risk Analysis, 44(8), 1788–1808. https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.14278

Higgins, E. T. (1997). Beyond pleasure and pain. American Psychologist, 52(12), 1280–1300. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.52.12.1280

Homar, A. R., & Cvelbar, L. K. (2021). The effects of framing on environmental decisions: A systematic literature review. Ecological Economics, 183, 106950. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2021.106950

Kung, C. S. J., & Steptoe, A. (2024). Changes in well-being among socially isolated older people during the COVID-19 pandemic: An outcome-wide analysis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 121(18), e2308697121. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2308697121

MacIntyre, E., Khanna, S., Darychuk, A., Copes, R., & Schwartz, B. (2019). Evidence synthesis evaluating risk communication during extreme weather and climate change: A scoping review. Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada: Research, Policy and Practice, 39(4), 142.

McLoughlin, N., Howarth, C., & Shreedhar, G. (2023). Changing behavioral responses to heat risk in a warming world: How can communication approaches be improved? WIREs Climate Change, 14(2), e819. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.819

Lambert, H., Doumont, D., Reviers, N., Vandenbroucke, M., & Aujoulat, I. (2025). Enhancing accessibility of crisis communication to people in vulnerable circumstances. Journal of Public Health. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-025-02436-x

Sadiq, A.-A., Dougherty, R. B., Tyler, J., & Entress, R. (2023). Public alert and warning system literature review in the USA: Identifying research gaps and lessons for practice. Natural Hazards, 117(2), 1711–1744. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-023-05926-x

Shin, J., Rang Kim, K., & Choi, H. (2022). The effects of impact-based heatwave warnings on risk perceptions and risk-mitigating behaviors. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting, 66(1), 1761–1761. https://doi.org/10.1177/1071181322661343

Weyrich, P., Scolobig, A., Bresch, D. N., & Patt, A. (2018). Effects of impact-based warnings and behavioral recommendations for extreme weather events. Weather, Climate, and Society, 10(4), 781–796. https://doi.org/10.1175/WCAS-D-18-0038.1

World Health Organization. (2017). Communicating risk in public health emergencies: A WHO guideline for emergency risk communication (ERC) policy and practice. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. Licence: CC BY-NCSA 3.0 IGO. https://www.who.int/emergencies/risk-communications/guidance

Annexes

A: Original request from SBS team

is a short-term piece of social and behavioural science work that our SBSE working group has raised as a priority for this summer. I am including details below about the scope, ideally it would be completed by the end of June to inform govt and local responder comms and engagement.

We were wondering if BR-UK might have capacity through the rapid response workstream?

Scope

Given the potential for concurrent risks this summer around droughts, wildfires and extreme heat, the task is to review messaging, advice and recommended actions to identify:

-

Areas of consistency across extreme heat, drought and wildfires materials advice

-

Any contradictory advice (for example, advice for drought around conserving water could contradict advice to use showering as a means for staying cool) and if so whether it can be simply amended to provide more consistency

-

How different national sources of warnings and advice (central government like Cabinet Office, national services & agencies like Met Office, UKHSA & Environment Agency) are likely to be received at the same time and understood by the public and whether such materials and channels could/should be better coordinated

-

How local sources of advice & messaging (e.g. public health bodies, local government, fire & rescue services, water companies) can reflect local conditions within an overall national situation.

The sources of advice, messaging and action to be considered – and any other relevant guidance and materials - will be provided by members of the cross-government Social and Behavioural Science for Emergencies Steering/Working Group.

B: Sources list

| Sources | Extreme heat | Drought | Wildfire |

|---|---|---|---|

| Affinity Water | / | ||

| Anglian Water | / | ||

| Consumer Council for Water (CCW) | / | ||

| Devon and Somerset Fire and Rescue Service | / | ||

| Dorset and Wiltshire Fire and Rescue Service | / | ||

| Edinburgh City Council | / | ||

| Environment Agency | / | ||

| Fire England | / | ||

| Forestry Commission | / | ||

| GOV.UK Prepare | / | / | / |

| Hafren Dyfrdwy – Severn Dee | / | ||

| Hammersmith & Fulham Council | / | ||

| Hampshire & Isle of Wight Fire and Rescue Service | / | ||

| Kent Fire and Rescue Service | / | ||

| Lincolnshire Fire and Rescue Service | / | ||

| Met Office | / | ||

| Middlesbrough Council | / | ||

| Monmouthshire Local Council | / | ||

| National Fire Chiefs Council | / | ||

| Natural England | / | ||

| Natural Resources Wales | / | ||

| Northern Ireland Water | / | / | |

| North Yorkshire Fire and Rescue Service | / | ||

| Northern Ireland Direct Government Services | / | / | |

| Northern Ireland Water | / | ||

| Northumberland Fire and Rescue Service | / | ||

| Ofwat | / | ||

| Public Health Wales | / | / | |

| Ready Scotland | / | ||

| Scottish Government | / | ||

| Scottish Water | / | ||

| Sommerset Council | / | ||

| South Staffs Water | / | ||

| Surrey Fire and Rescue Service | / | ||

| Tower Hamlets Council | / | ||

| UK Health Security Agency | / | ||

| Waterwise | / | ||

| Welsh Water (Dwr Cymru) | / | ||

| West Yorkshire Fire and Rescue Service | / |

The full resource list, including sources, individual document and message identifiers, message medium, type of context, is available on request.

C: Methods and use of AI statement AU Usage Statement

During this research, the author(s) used Claude Sonnet 4 to assist in conducting qualitative analyses of the data. While using this tool, the author(s) tested their prompts and reviewed the AI generated outputs for consistency and accuracy in representing the raw data. The authors edited all AI generated text before its inclusion in the final report and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Step 1: Call for Extreme Weather Advice

National government departments (e.g. UK Health Security Agency, Met Office) were asked to submit documents, such as communication plans, websites, and blogs, containing behavioural recommendations for the public when dealing with extreme heat, drought, and/or wildfires. We also carried out searches for behavioural recommendations from other sources, such as water companies and local councils.

Step 2: Data Extraction of Behavioural Recommendations

We developed a framework to extract concrete behavioural recommendations from raw government messaging data about extreme heat. Each row in our dataset represented a single behavioural recommendation, with the following columns:

-

Document identifier (ID): Source document reference.

-

Page no.: Page where the message was located.

-

Message ID: Unique identifier for the original message.

-

Author: Specific source of the advice.

-

Medium: Communication channel (e.g. social media, government website).

-

Type of content: Format of the message (e.g. text, image, video).

-

Message: Original message text.

-

Type of message: Categorised as either educational or actionable.

-

Target risk: The specific health risk addressed (e.g. dehydration, heat exhaustion).

-

Target population: Intended audience (e.g. general public, older adults).

During the extraction, we took notes regarding potential conflicting and consistent messages within and across risks, how well the recommendation can be tailored or disseminated via local communication channels, and suggestions to improve clarity, accessibility, or applicability of the original advice.

Step 3: Generating a Codebook of Recommendations

For each extreme weather category, we separated the extracted message data into messages containing actionable and educational messages in R. We input these messages into a large language model, Claude Sonnet 4, using the prompts outlined in Box 1. This generated a codebook of distinct behavioural recommendations that can be used to code the dataset. 2 researchers each used the prompt to separately generate a codebook. They then compared the similarity between the codes (e.g. exact matches, overlap, unique codes) in each codebook using Claude. Pairs of researchers then discussed the 2 codebooks and the comparison file produced by Claude to decide on a final set of codes based on their familiarity with the underlying data.

Box 1: Prompts for Codebook Generation

Below is a list of recommendations issued to the public during [extreme heat events]. It includes free-text behavioural recommendations (e.g. “Drink plenty of water”, “Check on older neighbours”, “Avoid strenuous exercise during midday”). Your task is to develop a coding framework that groups similar recommendations based on:

-

The core behaviour being recommended

-

The context or situation (e.g., time of day, location, conditions)

-

The target population, if any (e.g., older adults, children, outdoor workers, pets).

Please return a list with the following information:

Label: A short, descriptive code for the group (e.g., “Hydration”, “Check on vulnerable people”). Brief description: 1–2 sentences explaining what the label covers, including the types of behaviours, situations, or populations it includes.

Each code should be discrete and distinct, with no overlap between the labels. Aim for clarity and usefulness for someone using these to code the dataset to summaries the types of recommendations being made across documents.

The recommendations are: [insert messages here]

Educational Messages Below is a list of messages issued to the public during [extreme heat events]. It includes free-text educational (or informative) messages (e.g., “Who is at risk”, “Places more at risk”). Your task is to develop a coding framework that groups similar messages based on broader topic of the educational content. In creating the broader topics, please exclude behavioural recommendations or protective actionable measures, such as “Check weather forecasts”.

Please return a list with the following information:

Label: A short, descriptive code for the group. Brief description: 1–2 sentences explaining what the label covers, including the topic of the educational message and the types of situations or populations it relates to.

Each code should be discrete and distinct, with no overlap between the labels. Aim for clarity and usefulness for someone using these to code the dataset to summarise the types of educational messages included across documents.

Step 4: Applying the Codebooks

For each extreme weather category, the actionable and educational codebooks were used to code the datasets with Claude Sonnet 4 using the prompt in Box 2. We then randomly sampled 20% of the messages from each of the coded datasets for manual review by 1 researcher to assess whether they agreed with the codebook assignments.

Box 2: Prompt for Codebook Application

Actionable messages

The CSV file “[insert csv file name]” contains behavioural recommendations for the public during [insert weather event]. The columns are document_id, message_id, and message. Please print a table with document_id in the first column and message_id in the second. Add a third column to manually assign each message into 1 of the predefined categories below, using the category definitions to determine the best match.

IMPORTANT: Do NOT write any code, JavaScript, Python, or automated scripts to categorize these messages. I want you to use your own language understanding and judgment to manually review and categorize each message 1 by 1. Do not use keyword matching, NLP libraries, or any automated categorization methods.

Categorisation instructions:

Step 1: Review Process

-

Read each message completely and understand its primary intent

-

Consider the main behavioural recommendation being communicated

-

Identify the primary focus of the message (what is it mainly trying to achieve?)

-

Determine if the message addresses 1 or multiple distinct behavioural categories.

Step 2: Category Assignment Logic

-

Match the message’s primary purpose to the category definitions

-

Use the category descriptions as your guide, not just the category names

-

Consider the specific action or behaviour being recommended

-

Assign the PRIMARY category that best represents the main behavioural focus

-

If the message substantially addresses a second distinct category of equal or near-equal importance, assign a SECONDARY category using a semicolon separator (e.g., “Primary Category; Secondary Category”)

-

Only use dual coding when both categories are genuinely essential to understanding the message’s behavioural recommendations.

Step 3: Decision Framework

-

Ask yourself: “What is the primary behaviour this message is trying to encourage?”

-

For potential dual coding: “Does this message give substantial guidance for 2 different types of behaviour?”

-

Choose the category that best captures the primary behavioural goal

-

Only assign dual categories if removing either category would significantly diminish the message’s meaning

-

Only assign ‘N/A’ if the message truly doesn’t fit any category or is too general

-

Avoid dual coding for minor mentions or secondary elements.

Output Format: Format the table as CSV and include it in a code block. Each message should be assigned to 1 primary category, or where absolutely essential, use dual coding with semicolon separation for messages that address multiple categories of equal importance.

Categories: “[insert Category Labels]” Category Descriptions: “[insert Category Descriptions]”

Educational Messages

The CSV file “[insert csv file name]” contains educational messages for the public during [insert weather event]. The columns are document_id, message_id, and message. Please print a table with document_id in the first column and message_id in the second. Add a third column to manually assign each message into 1 of the predefined categories below, using the category definitions to determine the best match.

IMPORTANT: Do NOT write any code, JavaScript, Python, or automated scripts to categorize these messages. I want you to use your own language understanding and judgment to manually review and categorize each message 1 by 1. Do not use keyword matching, NLP libraries, or any automated categorization methods.

Categorisations Instructions:

Step 1: Review Process

-

Read each message completely and understand its primary intent

-

Consider the main educational message being communicated

-

Identify the primary focus of the message (what is it mainly trying to achieve?)

-

Determine if the message addresses 1 or multiple distinct educational categories.

Step 2: Category Assignment Logic

-

Match the message’s primary purpose to the category definitions

-

Use the category descriptions as your guide, not just the category names

-

Consider the specific educational or informational content being communicated

-

Assign the PRIMARY category that best represents the main focus

-

If the message substantially addresses a second distinct category of equal or near-equal importance, assign a SECONDARY category using a semicolon separator (e.g., “Primary Category; Secondary Category”)

-

Only use dual coding when both categories are genuinely essential to understanding the message’s educational content.

Step 3: Decision Framework

-

Ask yourself: “What is the primary educational topic this message is trying to convey?”

-

For potential dual coding: “Does this message give substantial information for 2 different topics?”

-

Choose the category that best captures the primary educational goal

-

Only assign dual categories if removing either category would significantly diminish the message’s meaning

-

Only assign ‘N/A’ if the message truly doesn’t fit any category or is too general

-

Avoid dual coding for minor mentions or secondary elements.

Output Format: Format the table as CSV and include it in a code block. Each message should be assigned to 1 primary category, or where absolutely essential, use dual coding with semicolon separation for messages that address multiple categories of equal importance.