Platform for action promoting the rights and wellbeing of children born of conflict-related sexual violence

Updated 14 July 2023

Photo credit: © 2015/World Vision UK

This Platform has been collaboratively developed by: the UK’s Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative (PSVI); Erica Hall, member of the PSVI Team of Experts; The United States; Mexico; Guatemala; Kosovo; the Offices of the Special Representatives of the Secretary-General (SRSG) on sexual violence in conflict, on violence against children and for children and armed conflict; UN Action Against Sexual Violence in Conflict; UNICEF; the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR); the PSVI Survivor Champions; Congo Restoration; Green Kordofan; Children Born of War Project; Annie Bunting, York University; Joanne Neenan, International lawyer; Lejla Damon; the Forgotten Children of War Association; and the Global Survivors Fund.

The development of this document was funded by UK aid from the UK Government, however the views expressed do not necessarily reflect that of the UK government or its policies.

Photo credit: I.Š./Klix.ba

1. Introduction

This Platform for Action is a sister document to the Call to Action to Ensure the Rights and Wellbeing of Children Born of Sexual Violence in Conflict (CtA). While the CtA represents a pledge to work with and for children born of conflict-related sexual violence, this Platform outlines how we will do this. It provides context for understanding the challenges faced by children born of conflict-related sexual violence and outlines a set of urgent priorities for addressing these challenges, providing a framework for coordinated action.

Governments, UN entities and civil society organisations are encouraged to concurrently endorse the CtA and make commitments under this Platform. Commitments are being compiled by the PSVI Team in the UK Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, as coordinators of this initiative[footnote 1].

2. Overview

Sexual violence is too often a reality for all people living in conflict zones around the world, particularly women and children. The circumstances in which sexual violence is committed can vary. For instance, it may be used by military forces as a tactic of war and/or may amount to torture. As outlined in the Secretary-General’s 2022 report Women and girls who become pregnant as a result of sexual violence in conflict and children born of sexual violence in conflict[footnote 2], one of the ways armed actors have used sexual violence as a tactic of war and ‘ethnic cleansing,’ including forcibly impregnating women and girls. Military personnel, peacekeepers and humanitarian workers may also opportunistically commit sexual violence amidst a breakdown in rule of law during and following conflict. Crimes involving sexual violence have been documented in Colombia, Rwanda, Uganda, Colombia and the former Yugoslavia, and are being reported in Cameroon, the Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Iraq, Mali, Myanmar, Nigeria, Somalia, South Sudan, the Syrian Arab Republic and elsewhere.

The root causes of sexual violence, as with all forms of gender-based violence, lie in structural gender inequalities and patriarchal norms. These are further compounded and intensified by the widespread societal acceptance of men’s use of violence against women, girls and boys with impunity. Women and girls then face further barriers with a lack of access to appropriate sexual and reproductive health services particularly in fragile and conflict affected states to ensure immediate and longer-term medical care.

Furthermore, a society’s understanding of ‘childhood,’ including at what age childhood ends, what agency or vulnerabilities are inherent at different ages and stages, and what role communities have in protecting children, can also increase the risk of violence against them. Sexual violence is used as a tactic to terrorise and demoralise communities and so children may be specifically targeted to maximise fear in the community. In such situations, child survivors’ and children born of conflict-related sexual violence’s vulnerability “to abduction, recruitment and use by armed groups and forces and to conflict-driven trafficking and sexual exploitation[footnote 3] is increased.

While there is no comprehensive data on the exact number of survivors of conflict-related sexual violence who give birth to children as a result, it is estimated that 20,000 children were born from conflict-related sexual violence during the civil war in Sierra Leone alone.[footnote 4] Given the perpetration of sexual violence has been and continues to be witnessed in conflicts the world over, the true global figure is likely to be significantly higher, with children born of conflict-related sexual violence in every region of the world[footnote 5].

While no two contexts are the same, the mental, physical, emotional, social, economic, political and security costs of sexual violence can be devastating. These consequences deeply affect survivors, including those who become pregnant as a result and their children, who are often marginalised, their needs ignored, and their rights violated and abused[footnote 6].

Photo credit: © World Vision UK

Some children born of conflict-related sexual violence have expressed feeling ‘invisible’ and ‘unrecognised,’ and of remaining ‘in the shadow of war’ even after the war has ended.[footnote 7] The barriers they face have lifelong impacts on their ability to live life in all its fullness, in turn impacting their futures and those of their communities and nations. Furthermore, for every child born of sexual violence, there is a woman or girl whose life chances may have been dramatically affected and whose relationship (or absence of any relationship) with the child can lead to mental health impacts for years to come. Some adolescents face stigma and discrimination when pregnant which may be further compounded by a pregnancy from sexual violence. And yet, survivors and children born of conflict-related sexual violence demonstrate great strength and resilience, which must be supported through active engagement and further empowerment.

Photo credit: © 2011 Jon Warren/World Vision

UN Security Council Resolution 2467 and the ensuing Secretary-General’s report Women and girls who become pregnant as a result of sexual violence in conflict and children born of sexual violence in conflict have highlighted the specific challenges faced by survivors[footnote 8] who become pregnant, and children born of conflict-related sexual violence. Children born of conflict-related sexual violence and the survivors who give birth to them face both distinct and overlapping challenges. Full respect for the rights of one cannot be reached without recognition of the rights of the other.

Ensuring a survivor-centred approach is a guiding principle of the Women, Peace and Security (WPS) agenda; the Call to Action on Protection from Gender-Based Violence (GBV) in Emergencies, and UN Secretary General’s 2017 framework for addressing sexual exploitation, abuse and harassment. This approach must be at the core of supporting survivors of sexual violence and promoting their access to justice.

Effectively supporting children born of conflict-related sexual violence requires concerted effort to ensure their rights, at the global, regional, national and local levels, recognising the specifics of the context and drawing on important learnings from the broader gender-based violence and child protection sectors. Effective support further requires a holistic approach that supports children’s best interests whether as part of families (alongside their mothers and other caregivers) or in alternative care. Such support must also consider how both age and gender can affect risks of conflict-related sexual violence and the impacts it has on children born of conflict-related sexual violence and survivors.

States Parties have obligations under the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC),[footnote 9] the UN Convention on the Elimination of All forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), and other human rights instruments[footnote 10] to respect and ensure human rights without discrimination, including with respect to the rights of children born of conflict-related sexual violence and survivors. It is vital to recognise and uphold the agency of children and survivors to make their own choices and decisions. Such action is also needed to realise the Sustainable Development Goals.

3. Framing action under the Platform

Background to the Platform for Action

Recognising the need for urgent action, the Call to Action to Ensure the Rights and Wellbeing of Children Born of Sexual Violence in Conflict (CtA) was launched in London in November 2021. In endorsing the CtA, stakeholders have agreed to work together to:

- speak out on the challenges faced by children born of conflict-related sexual violence and the need to ensure their rights and wellbeing as a critical step towards sustainable peace

- provide space for children born of conflict-related sexual violence and survivors who wish to share their knowledge safely and meaningfully, including through meaningful consultation and participation in the wider discussions and debates on these issues and support the agency they already exhibit

- strengthen legal and policy frameworks to eliminate barriers obstructing full respect for, realisation and pro-active support of the rights and wellbeing of vulnerable and/or marginalised groups of children, including children born of conflict-related sexual violence - and the rights of the survivors who have given birth to them - in ways that do not further harm, isolate or stigmatise them

- encourage child-sensitive approaches to humanitarian assistance, peacekeeping and sustainable development that recognise children born of conflict-related sexual violence as one of most vulnerable groups at risk of being left behind

Since the launch of the CtA, a broad Advisory Group has worked collaboratively to develop this Platform for Action (Platform),[footnote 11] with the aim of promoting the rights and wellbeing of this group of children without discrimination or stigma. The process of drafting the Platform has brought together the voices, experiences and expertise of children born of conflict-related sexual violence, survivors of conflict-related sexual violence and those who support them, UN agencies, academics and government stakeholders. The Platform also draws on a wide range of research and wealth of existing guidance on cross-cutting issues of gender-based violence, sexual exploitation, abuse and harassment in the humanitarian sector, and the protection of children in armed conflict.

The Platform recognises the interconnection with the rights and wellbeing of survivors, including those who give birth to children from conflict-related sexual violence. The CtA and this Platform have been developed at the same time as and consistently with the Secretary-General’s report, each recognising that a holistic approach to addressing conflict-related sexual violence means upholding the rights of both survivors and children born of conflict-related sexual violence. They shine a spotlight on the inequality and stigma impacting both children born of conflict-related sexual violence and the survivors who give birth to them.

To fully ensure the rights and wellbeing of survivors of sexual violence who give birth to children as a result, as well as their access to holistic support, services and justice, the Platform must be implemented alongside and, where feasible, integrated into Action Plans on Women, Peace and Security; the Call to Action on the Protection from GBV in Emergencies; the Committee on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW); the UN Secretary-General’s Special measures for protection from sexual exploitation and abuse; and other global initiatives. Close coordination with organisations that support survivors of gender-based violence, including those that provide tailored comprehensive sexual and reproductive health and psychosocial services is essential.

Lejla Damon

This Platform provides context for understanding the challenges faced by children born of conflict-related sexual violence[footnote 12] and efforts they are making to overcome them, based on consultation with members of this population and those who advocate on their behalf. It outlines a framework for change promoting the rights of these children, consistent with the UNCRC, as well as their rights once they enter adulthood. It defines critical areas of concern and a set of principles for addressing these challenges and provides a framework for commitments and coordinated action. It recognises that some children born of conflict-related sexual violence face compounded discrimination based on personal circumstances and status.

Areas of concern

In 2019, UN Security Council Resolution 2467[footnote 13] recognised the distinct risks of economic and social marginalisation of children born of conflict-related sexual violence and the potential for statelessness and discrimination against them. It also called on States to recognise these children’s equal rights in national legislation, consistent with their obligations under the UNCRC and CEDAW, as applicable. The Secretary-General’s 2022 report highlights several risks and harms faced by children born of conflict-related sexual violence, including: exclusion from cultural and family networks; long-term mental health consequences in the home; discriminatory birth registration policies and socioeconomic marginalisation; and the long-term impacts of barriers to education, healthcare and other necessities.[footnote 14]

These areas of concern are interrelated and interdependent. They have a significant bearing on a child’s ability to enjoy all their rights. Although more longitudinal studies are needed to fully understand the long-term impacts of the challenges noted above, the absence of accessible and safe education, mental health and psychosocial support and livelihood opportunities present a serious threat to the wellbeing of survivors and children born of conflict-related sexual violence.[footnote 15] This in turn leaves children born of conflict-related sexual violence at even greater risk of poverty, exposure to crime and violence, exploitation and mental health issues.

Areas of concern

Guided by children born of conflict-related sexual violence and existing literature, the Platform identifies six areas of particular concern:

- inequality, stigma and exclusion: situated within a wider environment of gender inequality and victim-blaming, children born of conflict-related sexual violence face a significant risk of stigmatisation that compounds their vulnerability and exclusion, and adversely affects their enjoyment of their human rights. Children born of conflict-related sexual violence may be forcibly separated from their birth mothers and ostracised by their communities, compounding issues of exclusion, identity, and trauma

- barriers to legal identity, belonging and access to reparations: laws and policies can reinforce the stigmatisation and exclusion of children born of conflict-related sexual violence by restricting birth registration and nationality, inheritance rights, access to legal and civil documentation, and access to their right to effective remedies

- lack of access to physical and mental health support: access to healthcare in conflict and post-conflict settings is often a challenge, with children born of conflict-related sexual violence facing additional barriers due to stigma and family circumstances. At the same time, the need for mental health services and psychosocial support has been identified as a key concern by these children, both for themselves and their mothers. In these situations, early delivery of nurturing care, including health, nutrition, safety and protection, from birth onwards will have a significant impact on a child’s outcomes

- insufficient consultation and opportunities for children born of conflict-related sexual violence who wish to speak out: children born of conflict-related sexual violence (whether they are still children or are adults) can feel ‘invisible’ in their communities and stigmatised. Their agency and positive powerful role is often under-recognised or championed. For those who wish to speak out, this feeling is compounded when they are not consulted in decision-making and dialogue at the local and national level. Throughout their lives, children born of conflict-related sexual violence have a unique and important perspective on gender discrimination, gendered violence, armed conflict and building peace; involving them will not only benefit their wellbeing but also the future of their communities and countries

- increased risk of violence, exploitation and abuse: because of their marginalisation, often poor economic situation and other vulnerabilities related to their birth status, children born of conflict-related sexual violence are at increased risk of violence, exploitation and abuse

- economic, social & health challenges for survivors who give birth to children as a result of conflict-related sexual violence: women and girls who experience conflict-related sexual violence and give birth to children as a result may face the ‘double stigmatisation’ of the violence and of the child’s parentage. In addition to significant physical and psychological impacts, they may also suffer socially and economically, such as ostracisation and an inability to support themselves and their children financially and in meeting basic needs, which can lead to intergenerational poverty and a downward spiral of opportunity and outcomes for both. These challenges may be experienced by both survivors who go on to raise the child, as well as those who are forcibly separated from them

A full list of commitments to date will be included as an Annex to the Platform when it is launched at the Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict conference in November 2022.

Using the Platform

The Platform identifies concrete solutions to address these areas of concern, as outlined in Section 3. Endorsers of the CtA and this Platform should therefore consider which priorities they are best placed to support and commit to one or more concrete actions. Commitments will be brought together in a single table to map actions and identify where collaboration is possible.

At the core of these commitments will be those made by:

- conflict-affected and post-conflict States, which may include reviewing the status of their laws, policies and practices and taking concrete steps to adapt and/or strengthen them and championing the most vulnerable children domestically and internationally

- supporting States, which may include financial and other support to: strengthen the evidence base; prioritise the most vulnerable children in overseas development assistance and diplomacy; and support the active participation of networks of children born of conflict-related sexual violence in domestic and global advocacy

- UN entities, which may within their mandates include support to building the evidence base and tracking progress; using their voice to speak out with and on behalf of children born of conflict-related sexual violence; programming commitments to address the needs of children born of conflict-related sexual violence along with other at-risk children and survivors (particularly those who give birth to them)

- NGOs and other civil society actors, which may include building the evidence base, listening to and supporting networks of children born of conflict-related sexual violence and programming to support these children, alongside other at-risk children, and survivors (particularly those who gave birth to them)

Commitments will be delivered through concerted collaborative action by States, UN entities, and civil society actors, working together with children born of conflict-related sexual violence, survivors who give birth to them and communities supporting them. The Platform seeks to galvanise political will into action, setting a global agenda that will advance the rights and wellbeing of children born of conflict-related sexual violence. Therefore, stakeholders should use the Core Principles[footnote 16] in this Platform and be mindful of the areas of concern they are trying to address.

©2015/World Vision

4. Strategic priorities

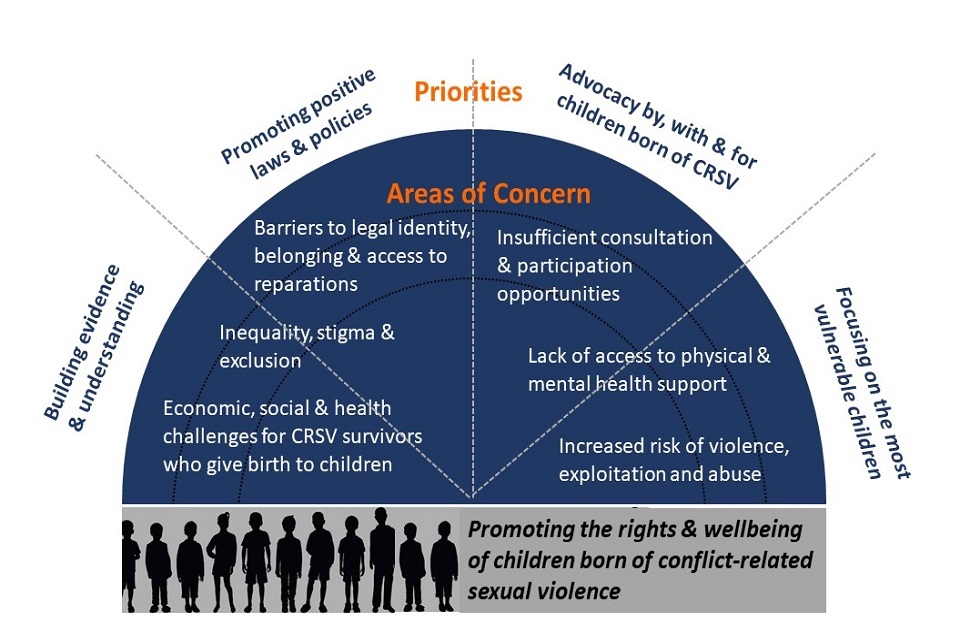

The four Strategic Priorities outlined below have been identified as key categories under which urgent action is required to promote the rights and wellbeing of children born of conflict-related sexual violence. They encompass key solutions to address the areas of concern identified and aim to impact positively on survivors who give birth to these children, whether or not they are their caregivers.

The Actions span the areas of concern detailed in Section 2 and reflect the Core Principles for action outlined in Annex C, including the need to apply a gendered and child-sensitive lens. The Strategic Priorities are interlinked, are of equal priority and are mutually reinforcing.

While the context and specific gaps may differ from country to country, and practical implementation must recognise the gendered nature of challenges faced by girls and boys, the Priorities apply equally at the local, national, regional and global levels.

Outlines the 4 strategic priorities and 6 areas of concern

Priority 1: building evidence and understanding on children born of conflict-related sexual violence

A culture of silence reinforces the stigmatisation and marginalisation of children born of conflict-related sexual violence and survivors who give birth to them. In many conflict and post-conflict contexts, the conversation around their rights and experiences has not even started. We must build a comprehensive picture – by and with children born of conflict-related sexual violence – of the challenges and harms they face, to improve the global and country-specific picture of the situation. It is also important to build evidence on what positive interventions have been effective, and to showcase the stories of those who have been able to thrive.

Priority actions

-

commission a comprehensive, gender-sensitive global study on children born of conflict-related sexual violence covering relevant countries, regions and communities. This study would build on existing academic research[footnote 17] and the findings of the UN Secretary-General’s report and should be developed in collaboration with children born of conflict-related sexual violence. It would aim to provide a broad analysis of the immediate and long-term risks, harms and challenges faced by children born of conflict-related sexual violence and explore strategies to empower both children and mothers over the long-term. The study would seek to identify factors, variables and positive interventions to help reduce or eliminate the immediate life-threatening and long-term challenges faced by children born of conflict-related sexual violence. It could also include positive stories from children born of conflict-related sexual violence and survivors who gave birth to them to highlight best practice and lessons learned, as well as information gathered from national assessments (where available)[footnote 18].

-

compile evidence of what works to promote wellbeing.[footnote 19] Examples of laws, policies and interventions that have made a positive impact can be used in advocacy and in the development of new commitments under this Platform. This evidence can sit alongside the global study noted above

Priority 2: promoting effective laws, policies & practices

For the rights and wellbeing of children born of conflict-related sexual violence to be respected and protected, equality and inclusion must be both embedded in national laws and policies and implemented in practice. The principles and rights enshrined in the UNCRC are a deeply important foundation for safeguarding the wellbeing of all children. Ensuring that all children can be registered and have a legal identity and nationality, regardless of the circumstances of their conception or parentage and without resulting in further discrimination of them or their mothers and families, is extremely important. This is often a precursor to enjoyment for other rights, including to the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health, education, and participation in the conduct of public affairs – which must be afforded to all without discrimination.

Given the challenges faced by children born of conflict-related sexual violence often continue into adulthood (as do the impacts on survivors who give birth to them), survivors and their children must be explicitly included in laws and transitional justice processes. For example, they should be included in any special status for victims of the war, should be entitled to reparations and should be included in mediation and peace talks.[footnote 20]

Stigmatisation and exclusion often happen in practice, underpinned by discriminatory laws even if it is prohibited in law. Reducing and preventing stigma requires concerted effort at global, regional, national and community levels. The Principles for Global Action on Preventing and Addressing Stigma[footnote 21] are an important tool to ensure policies, communications and actions relating to conflict related sexual violence do not create or reinforce stigmatisation of children born of conflict-related sexual violence and survivors. Laws and policies must be robust and non-discriminatory. Additionally, community-level interventions may be needed to ensure attitudes and practices actively accept these children and respect their rights.[footnote 23]

Priority actions

-

promote, support and conduct reviews of national law, policy and practice in conflict-affected and post-conflict states,[footnote 22] against their specific impact on the rights and wellbeing of children born of conflict-related sexual violence. National reviews should be conducted in line with the UNCRC, CEDAW and other legal instruments and standards, where applicable, and be both gender- and child-sensitive. They should also identify barriers to implementation of laws, including social, religious, and cultural norms and practices. Based on the review, the State should embed measures to address any shortcomings into new or existing strategies and action plans.

- promote the use of existing tools aimed at addressing conflict-related sexual violence as they apply to promoting the rights and wellbeing of children born of conflict related sexual violence and survivors who give birth to them. These tools, which include but are not limited to the Principles for Global Action on Preventing and Addressing Stigma (PDF, 954 KB), the Murad Code, the International Protocol on the Documentation and Investigation of Sexual Violence in Conflict (PDF, 3.7 MB), and the Declaration of Humanity provide important guidance for positive policies, communications and actions affecting survivors, children born of conflict-related sexual violence and other marginalised children.[footnote 23]

- promote survivor-centred and child -sensitive justice and transitional justice mechanisms that do not exacerbate stigma and harm faced by children born of conflict-related sexual violence and survivors who give birth to them, and address the root causes of this stigma. This should include full and holistic reparation and guarantees of non-repetition as a means of reducing the compounded stigmatisation. It is important that these individuals are able to return to school, resume employment, access relevant services and take part in all their normal activities.

Priority 3: empowering children born of conflict-related sexual violence and advocating with, and on behalf, of them

Children and youth have an important advocacy role to play if they choose to and are given the opportunity to speak out[footnote 24]. Their right to be heard is enshrined in the UNCRC[footnote 25]. For example, Article 12(2) UNCRC provides for children to be provided the opportunity to be heard in any judicial and administrative proceedings affecting them; This is paramount to fulfilling their rights, building sustainable peace and promoting equality in their communities.

This role does not cease when children born of conflict-related sexual violence become adults. They may feel a responsibility to speak out to stop the scourge of conflict-related sexual violence and help others in a similar position to themselves. Recognising that some children born of conflict-related sexual violence (whatever their age) and survivors who gave birth to them would like to engage in such conversations while others may prefer more privacy, ensuring safe and trusted spaces for those who choose to participate is critical.

To ensure safe and meaningful participation when engaging children born of conflict-related sexual violence and survivors who give birth to them, the following principles should be taken into consideration[footnote 26]:

- ensuring all consultation and engagement with children born of conflict-related sexual violence adheres to best practices in child protection and child participation, centre the best interests of the child, and follow a survivor-centred approach

- is voluntary, respectful and does no harm, honestly representing potential benefits to participants

- takes account of risks and prioritises safety, security and mental health

- recognise that children born of conflict-related sexual violence and survivors, even when choosing to engage, may have significant and ongoing medical, psychosocial, educational, financial and legal needs that make engagement challenging

- promote meaningful participation, using standardised scope, quality and outcome benchmarks for consultation and participation.[footnote 27]

Promoting the agency of children born of conflict-related sexual violence and survivors who give birth to them is a key overarching component of this Platform, as is giving visibility to children born of conflict-related sexual violence -led initiatives. They should have the choice to bring their perspectives and knowledge to policy discussions, event planning and political dialogue. Stakeholders should listen to and amplify the voices of children born of conflict-related sexual violence where possible and challenge others to do the same.

Priority actions

- support existing networks of children born of conflict-related sexual violence, where they exist, and the development of further networks on national, regional and global levels to share their challenges and successes and lobby for greater action. Support solidarity between networks of survivors who have borne and/or raised children born of conflict-related sexual violence and networks of children born of conflict-related sexual violence to share lessons learned and advocate for change

- using existing guidance for safe and meaningful consultation with survivors of sexual violence and children, provide space to and actively consult with children born of conflict-related sexual violence and survivors who choose to engage with policy, programmatic and other discussions. Stakeholders can use their access and influence to promote the agency and views of children born of conflict-related sexual violence and survivors, as well as raising awareness of the political, social, economic and health challenges they face and their role in building peaceful, prosperous societies. Depending on remit, this may include addressing these matters in and through international organizations and other intergovernmental bodies (such as the UN Security Council, Human Rights Council, African Union Peace and Security Council, African Commission on Human and People’s Rights and African Committee of Experts on the Rights and Welfare of the Child, League of Arab States, and the European Commission) to speak out. It also means involving children born of conflict-related sexual violence meaningfully in community, national, regional or global dialogues and decisions on peacebuilding, equality, sustainable futures, preventing conflict-related sexual violence and children’s rights – including as part of the Youth, Peace and Security agenda

Priority 4: focusing on the most vulnerable children

In 2015, UN Member States made a transformative commitment to ‘leave no one behind’ in seeking to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Reducing inequalities and vulnerabilities are intertwined with the ability to eradicate poverty and create a fair, safer and sustainable future. Vulnerable and marginalised children, including children born of conflict-related sexual violence, are most likely to be left behind unless they are at the heart of sustainable development. Abiding by the commitment to leave no one behind requires focusing on the most vulnerable and marginalised children in policies and practices across the humanitarian-development-peace nexus – and addressing the gender inequality that provides acute challenges for children born of conflict-related sexual violence and the survivors who give birth to them. In this way, the Strategic Priorities are linked and achieving Strategic Priority Four is an important part of achieving Strategic Priorities One-Three. Stigmatisation of children born of conflict-related sexual violence can be reduced and community affiliation increased by including them in national and community-based initiatives targeted at broader groups of vulnerable children.

Actions to be taken

- allocate resources and implement targeted initiatives to address the needs of the most marginalised children and women, including children born of conflict-related sexual violence and survivors who give birth to them. These should include: improving psychosocial and wider health services (including sexual, reproductive and maternal health services), early childhood development, positive parenting and other support that help children and mothers cope with complex relationships; social inclusion, economic support and livelihood opportunities; empowerment of women and children; access to and provision of education for all children; ending violence against children; and providing support for children affected by conflict[footnote 28]

- embed child rights and wellbeing risk assessments into programmatic funding and design decisions. Prioritise reaching those children facing the greatest barriers to realisation of all their rights, including civil, political, economic, social, and cultural rights

Photo credit: © 2014/Peter Simpson/WorldVision

5. Monitoring and evaluation progress

Success of this Platform is dependent on robust commitments, with progress measured and shared for the benefit of other stakeholders involved. In order to support transparency, evaluation and best practice sharing, an easy-to-use annual reporting template will be included with commitment guidance. The individual stakeholder reports will feed into global reporting and moments to assess cumulative progress against the objectives.[footnote 29]

6. Conclusion

The Convention on the Rights of the Child is the most widely ratified human rights treaty with near universal ratification. It clearly states that all children are entitled to the same rights.

General Comment No. 5 of the Committee on the Rights of the Child recognises that for some children, recognition and exercise of their rights may require “special measures.”[footnote 30] Children born of conflict-related sexual violence are often amongst the most vulnerable and marginalised in their communities. They are entitled to the respect and protection of their rights as children[footnote 31] and into adulthood, irrespective of how they were conceived. It is therefore important to recognise that children born of conflict-related sexual violence and other marginalised children are likely to fall through the cracks without effective recognition and realisation of their rights.

The Platform is based on this principle. However, it also recognises that children born of conflict-related sexual violence do not stop being ‘born of sexual violence’ when they become adults – and their human rights must continue to be respected and ensured. While efforts to change the situation of children under this Platform will create a better world for those who are children now or are born in the future, action must include the voice of those who have already reached adulthood and continue to promote their rights and wellbeing – including the right to participate in the social, political and economic life of their communities.

This Platform provides a structure for action to promote the rights and wellbeing of children born of conflict-related sexual violence. However, no two contexts are the same. Therefore, any approach implemented must take into account, as appropriate, the cultural and local context. Putting the voices and needs of children born of conflict-related sexual violence at the heart of local, national and international approaches to peace and security, development and peacebuilding is a crucial step towards creating a world fit for all children.

Annex A: terminology

Various terms are used in literature, discussion and advocacy related to the rights and wellbeing of children born of conflict-related sexual violence. Where possible, this document has drawn on the preferences of children born of conflict-related sexual violence and those who have given birth to them in agreeing a standardised term. Below is the terminology used and explanation for the rationale.

Conflict related sexual violence

The Platform uses the United Nations definition - rape, sexual slavery, forced prostitution, forced pregnancy, forced abortion, enforced sterilization, forced marriage and any other form of sexual violence of comparable gravity perpetrated against women, men, girls or boys that is directly or indirectly linked to a conflict. That link may be evident in the profile of the perpetrator (who may be affiliated with a State or non-State armed group, which includes terrorist entities); the profile of the victim (who may be an actual or perceived member of a political, ethnic or religious minority group or targeted on the basis of actual or perceived sexual orientation or gender identity); and the climate of impunity, which is generally associated with State collapse, cross-border consequences such as displacement or trafficking, and/or violations of a ceasefire agreement. The term also encompasses trafficking in persons for the purpose of sexual violence or exploitation, when committed in situations of conflict.[footnote 32]

Children

Refers to all individuals, boys and girls, below the age of 18 years, which is generally consistent with Article 1 of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child.

Children born of conflict-related sexual violence

Refers to all individuals born from a pregnancy that was the result of conflict-related sexual violence, regardless of the individual’s current age. The circumstances of their conception impact these individuals throughout their lives, even after they reach the age of 18. It includes children born of sexual exploitation and abuse by peacekeepers and humanitarian workers during and following conflict.

Gender sensitive approach

An approach that acknowledges gendered power dynamics and their impacts, and recognises different needs of women, men, boys and girls.

Child sensitive approach

An approach that recognises children’s rights, evolving capacities and the special protections to which they are entitled; is based on the best interests of the child, is age appropriate and inclusive of their views and experiences.

Survivor

In the context of this Platform, the term ‘survivor’ is used to refer to a survivor of conflict-related sexual violence.

Survivor-centred approach

Following UN guidelines, a survivor-centred approach means putting the rights, needs, and choices of survivors, as identified by themselves, at the centre of all prevention and response efforts. This includes: protecting survivors’ rights; and respecting survivors’ individual choices; promoting survivors’ empowerment by placing their informed choices at the centre of responses; treating all survivors with respect, dignity, and equality, without discrimination.[footnote 33] These principles apply equally to survivors of conflict-related sexual violence and children born of conflict-related sexual violence.

Survivors who give birth to children as a result of conflict-related sexual violence

This Platform deliberately uses the term “survivors who give birth as a result of conflict-related sexual violence” in order to maintain the focus on the interconnection with the situation of children born of conflict-related sexual violence. Women and girls who become pregnant as a result of conflict-related sexual violence and do not give birth to the children are beyond the scope of this Platform.

Annex B: key issues of concern

Inequality, stigma and exclusion

Situated within a wider environment of gender inequality and victim-blaming, children born of conflict-related sexual violence face a significant risk of stigmatisation that compounds their vulnerability and exclusion. Common themes reported by children born of conflict-related sexual violence include harassment, bullying, rejection (by their families and/or communities), shame, and exclusion from school, friendships and opportunities. They describe feeling underrepresented within society – their very existence not always recognised – being marginalised, their needs ignored and their rights violated or abused. They may feel ashamed or excluded from their family or rejected by their mother, be seen as outcasts within the family and potentially abandoned.

The root causes of stigma are bound up with cultural, social and gender norms, political dynamics and the legal context, meaning that stigma may manifest itself in different ways in different conflict-affected or post-conflict settings.[footnote 34] However, regardless of the setting, the stigmatisation of children born of conflict-related sexual violence and their mothers embeds a sense of ‘otherness’ and insult. Research has identified a range of derogatory monikers being used, including “children of hatred” or “children of bad memories” (Rwanda), “children of shame” (Kosovo), “children of the enemy” (Timor-Leste), “rebel children” (Uganda), “Chetnik babies” (Bosnia) and “monster babies” (Nicaragua).[footnote 35] In the Democratic Republic of Congo, many children born of conflict-related sexual violence are not seen to have a place in traditional family structures because they are ‘without a father’ and are considered a ‘replica of the rapist’.[footnote 36] In Iraq, many in the Yazidi community believe that children born of conflict-related sexual violence “have evil in their blood and will not grow as Yazidis, but as ISIS.”[footnote 37] For some children, their forenames reflect the conditions of their birth, with names that translate to ‘insult’, ‘I have suffered’ or ‘only God knows why this happened to me.’[footnote 38]

In some situations, the circumstances of the conception are hidden by the family with someone else taking on the role of the father to avoid the perceived shame. While it is sometimes easier to hide the circumstances of the conception if the survivor is already married, it is not uncommon for the children to then be used as leverage against the mother by her husband and his family. They may threaten to remove her and/or the child from the family if she disagrees with any choices they make.

Children born of conflict-related sexual violence often identify the stigma and exclusion they face within their family and community as the most significant barrier to their wellbeing. This is compounded by the stigma and inequality faced by their mothers. Stigma is a cross-cutting issue that impacts on the children’s ability to access education, healthcare, nutrition and other basic needs on equal terms with other children. It also has tremendous impacts on their mental health and personal relationships.

Barriers to legal identity, nationality and belonging

Laws and policies can reinforce the stigmatisation and exclusion of children born of conflict-related sexual violence. For example, a child’s legal identity is often a prerequisite for accessing education, health care or travel outside of the country and is critical for protecting children (preventing child labour or child marriage, for example). Yet, in some countries, the law requires a marriage certificate or the inclusion of the father’s name to register a birth, placing greater value on the male parent for the child’s identity. For example, in DRC, as in some other countries, an unmarried woman cannot pass on the father’s name without his consent. This means that the birth of a child born of conflict-related sexual violence is very likely to remain unregistered due to a survivor’s inability or unwillingness to obtain this consent. In Iraq, for example, the lack of identification card exposed children to a risk of arrest and detention, as security forces interpret the lack of identification as resulting from the denial of security clearance owing to past association with ISIL/Da’esh.[footnote 39]

Additionally, the national law may not allow a mother to pass nationality on to her child or to choose the child’s nationality, potentially leaving the child stateless.[footnote 40] Legal identity is not only often a prerequisite to accessing services but also impacts children’s sense of belonging and identity, hindering their freedom of movement, further stigmatising them and potentially increasing their vulnerability to risk.

The impact of barriers to legal identity, particularly in those contexts where legal or customary inheritance rights stem from the paternal family, are compounded by the child’s often contested identity and belonging within the family and community. An inability to have a registered birth and nationality therefore intensifies a child’s feeling of not belonging or not knowing where they belong, heightening the risks to their mental health. The legal and cultural barriers may also put the child at increased risk of physical violence against them.[footnote 41] They may hamper a child’s ability to enter education and use the health system, such that he violation of the right of the child to preserve his or her identity including nationality, name and family relations as recognised by law without unlawful interference, could become the trigger for further rights violations.

Lack of access to physical and mental health support

Millions of children around the world living in contexts affected by conflict suffer from mental health conditions such as anxiety and depression. Given the number of protracted crises today, children born of conflict-related sexual violence may grow up in a continued context of insecurity, displacement, violence and disruption to services. The combined toll taken by the distress and exposure to continued traumatic events and the emotional impacts of the stigma and contested identity noted above, present significant threats to the mental wellbeing of children born of conflict-related sexual violence. The children’s risk of mental health issues is also often integrally linked to the mental health of the survivors who have given birth to them. As children grow into adolescents their vulnerability to drug and alcohol abuse, self-harm and suicide increases.

Some children born of conflict-related sexual violence also require specialised physical health care, particularly if born in difficult circumstances or to young women or girls. As they grow, they need access to regular medical care, including immunisations and inclusive, comprehensive sexual and reproductive health services.

Children born of conflict-related sexual violence often cite mental health support as one of their greatest needs. However, access to health care, particularly mental health support, is lacking in contexts where conflict and other emergencies has further entrenched weaknesses in the health system. Whether the need is for specialised services for the child or community support, there are significant gaps in availability and accessibility in conflict and post-conflict settings. For children marginalised by stigma and/or lacking legal identity, the barriers to access may be even greater.

Insufficient consultation and opportunities to be heard

Stigmatisation and the sense of feeling ‘invisible’ in their communities is only compounded for those children born of conflict-related sexual violence who would like to speak out but are not consulted in decisions and discussions surrounding their lives and their communities. For children born of conflict-related sexual violence who are still in childhood, the lack of consultation and space to speak out may, depending on the circumstances, result in a violation of their rights under the UNCRC. Young people who were born of conflict-related sexual violence should be provided with the opportunity to shape law, policy and practice affecting them, and to work with other young people to create a space for expressing youth needs and ideas. As stated by the Forgotten Children of War Association in Bosnia and Herzegovina, “Young people can only be creators of change when they are directly involved in decision-making processes in order to build a better future.”[footnote 42]

Children born of conflict-related sexual violence of all ages have a unique and important perspective on gender discrimination, gendered violence, armed conflict and building peace. They can communicate the lasting effect of sexual violence, and many feel a responsibility to speak out so there may be no more children born this way. Involving them is therefore not only of benefit to their wellbeing but also to the future of their communities and countries. Others may not wish to identify themselves or speak out; their preference must be respected and protected.

Vulnerability to violence, exploitation and abuse

Each year, 1 billion children suffer some form of violence.[footnote 43] The Committee on the Rights of the Child has made clear its view that the principle of “non-discrimination” requires States Parties to actively identify individual children and groups of children whose recognition and exercise of their rights may require “special measures.”[footnote 44] Because of their marginalisation and other vulnerabilities related to their conception status, children born of conflict-related sexual violence fit into this category and research shows that they are at special risk of violence, exploitation and abuse in their homes and communities.

Where protection systems are weakened due to conflict, political instability, economic fragility, the climate crisis, epidemics and/or other circumstances, the most marginalised children face the greatest risk of being forgotten. In protracted conflict settings, the UN Special Representative of the Secretary-General for Children and Armed Conflict highlighted there is an increased risk of children born of conflict-related sexual violence becoming victims of what the United Nations Security Council has recognised the “six grave violations”[footnote 45] especially due to proximity to armed groups and forces and/or due to marginalisation and vulnerabilities related to their status. The tenuous economic situation of their mothers and potential lack of safe family networks may make them particularly vulnerable to trafficking, exploitation and/or living on the streets. They may also face abuse or neglect in the home.

While all children living in a conflict-affected context are at risk of violence, exploitation and abuse, and exposure to crime and violence, best practice suggests particular attention should be provided to those facing multiple and intersecting forms of discrimination and vulnerability (based on gender, ability, level of poverty, ethnicity, religion, etc.), as they are the most likely to have their needs ignored, their rights violated, and to suffer further harm. They are the most likely to fall through the cracks.

Economic and social challenges for survivors who give birth to children from sexual violence

Women and girls who experience conflict-related sexual violence and give birth to children as a result, likely face double stigmatisation – both as survivors of sexual violence, and as bearers of children as a result. The physical impacts of the rape, injury and birth will be compounded by significant psychological, social and economic impacts of the violence and having a child as a result if support is not given. In some instances, these survivors are forced into marriages, for instance when a man approaches the woman or family offering to take care of them, the offer is accepted because it is perceived that no man would want to marry them.

These challenges have an indelible impact both on the lives of the survivors and of their children, as the disadvantages are passed onto the children. If a birth mother is the primary caregiver for a child born of conflict-related sexual violence, their life chances are bound together even more closely. The stress, emotional suffering and trauma of experiencing sexual violence and motherhood in these circumstances can affect their ability to provide nurturing care and meet the child’s basic needs. It “creates additional risk factors for children, including poor mental health, economic and social exclusion.”[footnote 46] Consultations with children born of conflict-related sexual violence in Uganda identified livelihood assistance for mothers, parenting support and joint therapy with the children to be key factors in their own wellbeing.

The economic and emotional burden of giving birth to a child of rape can make it difficult for the survivors to cope with their own lives and needs, creating a difficult decision of whether it is ‛better’ to keep the child or give them up. Where the birth mother is unable or chooses not to be the child’s caregiver, it does not eradicate the emotional burden, and support for both will continue to be needed. Further, survivors of sexual violence are often forced to make decisions about their future and the future of their children in an instant, based on limited information and choices. There is a critical need to provide necessary services and safe spaces for survivors to make informed choices about their future.

Annex C: core principles for action

Implementation of this framework should be underpinned by the following core principles to ensure success and avoid further harm to children born of conflict-related sexual violence and survivors who give birth to them:

-

build on existing good practice of promoting the rights and wellbeing of other marginalised children. For example, good practice in changing community attitudes and supporting children born with or orphaned by HIV/AIDS[footnote 47] or children released from armed groups

-

apply the best interests of the child principle, in any action or initiative concerning children born of conflict-related sexual violence. The UNCRC states that, in all actions concerning children their best interests shall be a primary consideration. Applying this principle requires understanding the circumstances of the individual or group or children and, where relevant, actions should align with the rights and principles outlined in the Convention

-

use a survivor- and child-centred, human rights-based, gender sensitive-approach and intersectional lens to decide what actions are most appropriate in the setting or context. The rights recognized in UNCRC, CEDAW and other relevant human rights treaties should form the foundation of discussions and action. Action must take account of the differing experiences, treatment and vulnerabilities of and challenges for girls and boys, as well as of children of differing abilities or backgrounds. For example, underlying gender and other inequalities must be recognised, including but not limited to the impacts of gendered violence on survivors and their children

-

work in collaboration to ensure coherence of messaging and action, and to maximise impact. International cooperation to respect and promote the rights of children born of conflict-related sexual violence and the survivors who give birth to them is key to achieving the objectives in this Platform. Collaboration with and among communities, community-based organisations and children and youth is also critical. In particular, all stakeholders should promote the participation and leadership of children born of conflict-related sexual violence and survivors of sexual violence – whose lived experience provides the most valuable insight in designing action and measuring success – as well as those who act with and for them

-

prevent siloing of action and further stigmatisation of children born of conflict-related sexual violence. It is vital that this Platform not be seen in isolation; all stakeholders must continue to build child rights and sustainable development principles that benefit all children and the wider community. This includes embedding the wellbeing of children born of conflict-related sexual violence across all policy priorities and recognition of them as a group of children most likely to be left behind by peacebuilding and sustainable development approaches. While ‘do no harm’ principles make security and confidentiality of paramount concern, this should not preclude pro-active advocacy and policymaking to meet the needs of this vulnerable group

-

adopt a holistic approach that recognises and meets the needs of children born of conflict-related sexual violence, the survivors who give birth to them and their families. Children born of conflict-related sexual violence and the survivors who give birth to them face both distinct and overlapping challenges. Full respect for the rights of one cannot be reached without recognition of the rights of the other

-

be context specific: no two contexts are the same and it is important to base all action on local knowledge. Local leadership will ensure the role of culture and the sensitivities and opportunities in the local context are taken into account

Annex D: further resources for reference and support

Foundational resources

UN Convention on the Rights of the Child

UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (PDF, 90.5 KB)

Addressing stigma

Principles for Global Action on Preventing and Addressing Stigma (PDF, 954 KB)

Child participation and consultation

General Comment No.12 on The Right of the Child to be Heard

A Toolkit for Monitoring and Evaluating Children’s Participation (PDF, 1.3 MB)

The Research Ethics Guidebook, Research with Children

UNICEF Guidance on Child and Adolescent Participation (PDF, 953 KB)

Save the Children Consultation Toolkit (PDF, 551 KB)

World Vision Guidelines for Child Participation (PDF, 225 KB)

Preventing and responding to CRSV and GBV in Emergencies

Inter-agency Minimum Standards for Gender-Based Violence in Emergencies Programming (PDF, 2MB)

Call to Action on the Protection from Gender-Based Violence in Emergencies

SEAH and Safeguarding

UN Secretary-General’s Special measures for protection from sexual exploitation and abuse

Safeguarding Resource and Support Hub

Able_Child_Africa_Save_The_Children_DiCS_Guidelines (PDF, 3.5 MB)

Core Humanitarian Standard Alliance PSEAH Index

IASC Six Core Principles on Sexual Exploitation and Abuse

UN Protocol on the Provision of Assistance to Victims of Sexual Exploitation and Abuse (PDF, 187 KB)

New guide for NHRIs to support victims of sexual exploitation and abuse

Survivor-centred communications, investigation and documentation

International Criminal Court Policy on Children (PDF, 4.9 MB)

Core Humanitarian Standard Alliance SEAH Investigation Guide

-

A full list of commitments to date will be included as an Annex to the Platform when it is launched at the Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict conference in November 2022. ↩

-

UN Security Council doc S /2022/77, 31 January 2022 ↩

-

UN Security Council doc S /2022/77, 31 January 2022 ↩

-

UN Security Council doc S /2022/77, 31 January 2022 ↩

-

Joanne Neenan, 2018, citing Kai Grieg, “The war children of the world”, War and Children Identity Project, 2001; Forgotten Children of War Association (Udruženje “Zaboravljena djeca rata”), 2021. ↩

-

See eg., Carpenter, R. Charli, ed., Born of War. Protecting Children of Sexual Violence Survivors in Conflict Zones; Mochmann, I. C. (2017). Children Born of War - A Decade of International and Interdisciplinary Research. Historical, Social Research, 42(1), (2017), pp320-346. ↩

-

E.g., Forgotten Children of War Association (Udruženje “Zaboravljena djeca rata”), 2021; Wagner, K., Bartels, S.A., Weber, S. et al. UNsupported: The Needs and Rights of Children Fathered by UN Peacekeepers in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Hum Rights Rev 23, 305–332, 2022. ↩

-

Throughout the Platform, where we refer the women and girls who give birth to children born of conflict-related sexual violence, the term “survivor” is used to simplify the sentence structure; this is not intended to obscure the reality that both adult women and adolescent girls become pregnant and give birth as a result of conflict-related sexual violence. ↩

-

The Convention on the Rights of the Child is the most widely ratified international human rights convention. The provisions of the treaty are therefore nearly universally binding. ↩

-

See, eg., Mochmann, Ingvill C., and Sabine Lee, The Human Rights of children born of war: case analyses of past and present conflicts. Historical Social Research 35(3): 268-98, 2010. ↩

-

Endorsers involved in drafting the Platform for Action include: the Governments of the Democratic Republic of Congo, Kosovo, Mexico, the United Kingdom and the United States; and UN Special Representatives of the Secretary- General on Children and Armed Conflict, Sexual Violence in Conflict and Violence Against Children. The drafting Advisory Group also included UN Action members, organisations representing children born of conflict-related sexual violence, organisations representing survivors and academics with expertise in this area. Content drew invaluably on consultation workshops with children born of conflict-related sexual violence in Uganda and Bosnia. ↩

-

In using this Platform, it is important to check our own biases to ensure that we are not reinforcing stigma (for example in fearing the perceived association of the child with a UN-recognised terrorist organisation because of their parentage). ↩

-

UNSC Res 2467, PP18. ↩

-

UN Security Council doc S /2022/77, 31 January 2022, paras 15-18. ↩

-

UN Security Council doc S /2022/77, 31 January 2022 ↩

-

See Annex C for Core Principles to use when developing commitments and undertaking action to ensure success and avoid further harm to children born of conflict-related sexual violence. ↩

-

For example, the Children Born of War Project. ↩

-

It is critically important to consider varying reactions to children born of conflict-related sexual violence, within countries and even communities. ↩

-

Evidence of what works could be compiled as part of the global study, as a separate exercise, or become a separate research programme. ↩

-

A child born of rape can suffer many rights violations and is entitled to reparations, including access to health services, rehabilitation and legal identity, etc. ↩

-

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/645636/PSVI_Principles_for_Global_Action.pdf (PDF, 954KB) ↩

-

See Annex D for a broader resources for information and support with implementation. ↩ ↩2

-

Government leadership of the reviews and ownership of the follow up is the most effective way to achieve the Strategic Objective. However, assessments led by the United Nations or CSOs can support further action by the State. A toolkit to support this review will be available before the end of 2022. ↩

-

General Comment No.12 (2009), The Right of the Child to be Heard, UN Committee on the Rights of the Child https://www.refworld.org/docid/4ae562c52.html ↩

-

Article 12. ↩

-

General Comment No.12 (2009), The Right of the Child to be Heard, UN Committee on the Rights of the Child https://www.refworld.org/docid/4ae562c52.html. See also Annex D for additional resources on safe and meaningful consultation with and participation of children. ↩

-

The scope of participation of children born of conflict-related sexual violence and survivors ranges across a continuum from no involvement or consultation, being consultative, being collaborative (with join decision-making) to being child-, youth- or survivor-led. See A Toolkit for Monitoring and Evaluating Children’s (2014), https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/pdf/me_toolkit_booklet_4_low_res1.pdf/ (PDF, 1.3 MB) ↩

-

Specific attention must be paid to the needs of those forcibly recruited and abducted survivors held in captivity for long periods of time. ↩

-

Plans for how this will be done will be presented at the Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative (PSVI) International Conference in November 2022. ↩

-

Committee on the Rights of the Child, GENERAL COMMENT No. 5 (2003) General measures of implementation of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (arts. 4, 42 and 44, para. 6), UN Doc. CRC/GC/2003/5, 27 November 2003. ↩

-

For example, Article 2 of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child requires States parties to: “respect and ensure the rights set forth in the present Convention to each child within their jurisdiction without discrimination of any kind, irrespective of the child’s or his or her parent’s or legal guardian’s race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national, ethnic or social origin, property, disability, birth or other status” and “take all appropriate measures to ensure that the child is protected against all forms of discrimination or punishment on the basis of the status, activities, expressed opinions, or beliefs of the child’s parents, legal guardians, or family members.” ↩

-

Conflict-Related Sexual Violence Report of the United Nations Secretary-General (S/2019/280) ↩

-

For further details, see the Handbook for United Nations Field Missions on Preventing and Responding to Conflict-Related Sexual Violence (https://www.un.org/sexualviolenceinconflict/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/2020.08-UN-CRSV-Handbook.pdf (PDF, 9.7 MB)) and the Inter-agency Minimum Standards for Gender-Based Violence in Emergencies Programming (https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/19-200Minimun_Standards_Report_ENGLISH-Nov.FINAL.pdf (PDF, 2MB)) ↩

-

Much can be learned from the HIV/AIDS response, including taking a holistic approach that balances recognition of the needs and situations of survivors of sexual violence in as well as children born of conflict-related sexual violence. ↩

-

Forgotten Children of War Association, 2021; World Vision, 2015. ↩

-

Kimberley Anderson & Elisa van Ee, 2019. ↩

-

https://www.seedkurdistan.org/Downloads/Reports/201223-Children_Born_of_the_ISIS_War.pdf (PDF, 2.53MB) ↩

-

World Vision, 2015. ↩

-

UN Security Council doc S/2022/77, 31 January 2022, cites discriminatory nationality laws and practices in Iraq, Libya, Somalia, the Sudan, the Syrian Arab Republic, para 13. ↩

-

Joanne Neenan, 2018. ↩

-

Forgotten Children of War Association, 2021. ↩

-

See, e.g., United Nations, Keeping the Promise: Ending Violence Against Children by 2030, July 2019. ↩

-

UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, General Comment 5: General measures of implementation of the Convention on the Rights of the Child, CRC/GC/2003/527 November 2003. ↩

-

The 6 Grave Violations identified by the United Nations are: recruitment and use of children, killing and maiming of children, rape and other forms of sexual violence against children, abduction of children, attacks on schools and hospitals, and denial of humanitarian access. ↩

-

Joanne Neenan, 2018. ↩

-

See e.g., Tran, Thi Thu Nga, and Lillian Mwanri. “Addressing Stigma and Discrimination in HIV/AIDS Affected Orphans and Vulnerable Children in Vietnam.” World Journal of Preventive Medicine 1.3 (2013): 30-35; World Vision – Channels of Hope & Community Care Coalitions, South Africa. ↩