Evaluation of National Citizen Service 2023 to 2025

Published 13 February 2026

Applies to England

Summary

The National Citizen Service (NCS) was a key youth programme for 16 to 17-year-olds in England for over a decade. Between 2023 and 2025, a new programme with three distinct ‘service lines’ were offered by delivery partner organisations: residential experiences of at least four nights; community experiences;[footnote 1] and digital experiences. [footnote 2] NCS aimed to help young people to build skills for life and independent living; enhance employability and work-readiness; provide opportunities for volunteering and social action; and enable social cohesion. A consortium of external evaluators led by Verian, and including The Social Agency and London Economics, evaluated the NCS programme between 2023 and 2025.[footnote 3] This report outlines combined findings across both years of the new programme.

Delivery partners praised the new, diversified programme model as more inclusive by design. However, implementation was challenging for several reasons. Prolonged contract negotiations in the first year reduced the window for delivery. The lack of a centralised marketing function and absence of the online MyNCS platform (originally envisaged as a way for young people to register for all experiences) meant delivery partners had to undertake significantly more recruitment activity than originally planned. Multi-service line participation was limited in practice and tended only to occur where the same providers were delivering multiple service lines in a region. Funding constraints meant some providers had to supplement NCS monies themselves. The payment mechanism was felt to create greater financial risk for residential service line providers, compounded by high attrition rates particularly among bursary recipients. Despite these challenges delivery partners praised NCS Trust (NCST), Department for Culture, Media and Sport’s (DCMS’s) commissioning and delivery body, as a flexible and supportive partner. They also reported that the programme had resulted in regional and local partnerships between youth organisations which were expected to continue beyond the end of the programme.

Young people’s feedback on NCS residential trips was overwhelmingly positive, with more than 4 in 5 reporting that their experience was ‘enjoyable’ and ‘worthwhile’. They particularly valued the social aspects, the quality of staff, and adventure-based activities. However, evidence for the impact of the residential service line on outcomes is a more mixed picture. The programme appears to have had positive effects on leadership skills, teamwork skills in relation to helping others and asking for help, the perceived importance of social mixing, and problem solving. However, negative effects have been observed on social inclusion, responsibility, and empathy. No significant evidence of impact was identified in other areas, including listening and speaking, creativity, initiative, civic engagement and work readiness. There are some limitations to consider in interpreting these findings, the principal one being that they reflect only one of the service lines and therefore may under-represent the true impact of the 2023 to 2025 NCS model as a whole.

Reflecting on the evaluation evidence, it is recommended that similar future programmes should:

- introduce flexible ways for young people to engage

- build in data sharing systems between delivery partners from the outset

- draw upon popular elements of NCS

- capitalise on peer recommendation to encourage engagement

- ensure realistic timeframes for delivery

- aim to have a more stable and longer-term funding model

- ensure the programme theory of change is aligned with both design and delivery; and

- closely match the evaluation approach to the programme ethos and delivery model

Executive summary

Introduction

The National Citizen Service (NCS) was a key youth programme for 16 to 17-year-olds in England for over a decade, funded by DCMS. Until the COVID-19 pandemic, NCS delivered intensive part-residential programmes lasting 2 to 4 weeks twice per year. From 2023 to 2025 the NCS programme model was redesigned from a ‘one size fits all’ residential experience to a year-round model with three distinct groups of activities (or ‘service lines’). These were:

-

shorter residential experiences of two to four nights, tailored to reflect one of three ‘content themes’ – ‘Live it’ (focussed on building confidence and resilience through adventure-based activities), ‘Change it’ (focussed on helping young people make a difference through social change-focussed activities) and ‘Boss it’ (building work-readiness through skills and employment-focussed activities)

-

community experiences offering ‘open to all’ activities close to young people’s homes all year-round, and ‘targeted’ activities which scaled up existing interventions for specific groups or locations (e.g. Scouts)

-

digital experiences ranging from self-serve modular and multimedia online content (e.g. articles and advice) to live, interactive workshop sessions, live keynote ‘broadcast sessions’, and immersive games.

Through these experiences, NCS aimed to help young people build skills for life and independent living; enhance employability and work-readiness; and provide opportunities for volunteering and social action. All three service lines aimed to facilitate social mixing of young people from all backgrounds, as a key way of building longer-term social cohesion.

A national evaluation of NCS 2023 to 2025 ran for two years from February 2023 to August 2025, led by Verian and supported by The Social Agency and London Economics.

A process evaluation captured insights about programme implementation, delivery, reach and engagement in both years of the programme, drawing on NCS monitoring data, interviews with delivery partners and discussions with young participants.

An impact evaluation sought to understand the impact of participation on young people’s outcomes. A baseline and follow-up survey of NCS residential and community open to all participants and a comparison group took place in both years, with difference-in-difference analysis applied to estimate net impact.

An economic evaluation explored the average household’s willingness to pay in taxes to support NCS (i.e. estimating its non-use value), as well as estimating economic benefits and providing benefit-cost ratios associated with the residential service line in Year 1 in relation to the impacts on participants.

Implementation and delivery

The evolution of the new NCS programme model was viewed as a positive step by delivery partners engaged through the evaluation. They broadly endorsed the diversified service lines and introduction of community-based experiences, which were felt to make NCS more inclusive by design, facilitating the introduction of more varied opportunities that worked for a broader set of young people. Delivery partners still valued and embraced the residential aspect of NCS though it was recognised that shorter residential experiences might make it more challenging to achieve positive outcomes, relative to the previous model.

The new programme faced several implementation and delivery challenges. Prolonged contract negotiations at the beginning of the programme effectively shrunk the year 1 delivery window, which had implications for setting up and recruiting for experiences. The lack of a centralised marketing function and the absence of the MyNCS platform (originally envisaged as a ‘one-stop shop’ for young people to register for experiences) meant delivery partners had to undertake significantly more marketing work than originally planned. The ambition for multi-service line participation and engagement in more of a ‘year-round’ offer was limited in practice (not helped by delivery partners’ inability to be able to share participants’ data) and tended to be more likely to occur where the same providers were delivering multiple service lines in a region. Funding uncertainty could make it hard to plan for the medium-term, whilst funding constraints meant some providers had to supplement NCS monies themselves. The payment mechanism ‘pay mech’ was felt to create greater financial risk for residential providers, compounded by high attrition rates particularly among bursary recipients.

Delivery partners praised NCS Trust (NCST), the national arm’s length programme body, as a flexible and supportive partner. They particularly valued the open communication, flexible and supportive approach to managing grantees, and the visible senior engagement from NCST’s leadership team. Delivery partners also reported that the new regional delivery model for the community service line facilitated stronger collaboration within the youth sector, enabling providers to build regional consortia and cultivate local networks. These were expected to continue beyond the lifetime of the programme. Note that the evaluation only covered perspectives of organisations involved in NCS and so may not reflect the views of the wider youth sector.

Outcomes for young people

Young people’s feedback on NCS was largely positive, with 83% of residential participants surveyed reporting ‘enjoyable’ experiences, and 81% reporting the experiences were ‘worthwhile’. Interviews with young people taking part in residential and community experiences also showed feedback to be overwhelmingly positive. These participants particularly valued the social aspects of the programme, the quality of staff, and adventure-based activities that pushed them outside their comfort zones. No primary research was conducted with young people taking part in digital experiences, however, strategic leads involved in these experiences reported they had received positive feedback from young people.

To quantitatively assess the impact of the NCS programme, Verian conducted impact surveys with NCS participants taking part in the residential and community open to all service lines, alongside a comparison group of similar young people. It was not possible to conduct impact surveys with the community targeted and digital service lines due to the devolved nature of delivery (i.e. by third parties). While impact surveys were conducted for the community open to all service lines, the devolved and more flexible nature of delivery meant that baseline response rates were very low and confined to a short period towards the end of delivery. The impact analysis for community open to all is presented in the appendix to reflect these limitations.

Using aggregated data across both years of the programme, quasi-experimental analysis matched 2,984 NCS residential participants completing both baseline and follow-up surveys to a comparison sample of 2,949 respondents. Results from this residential only analysis are mixed, with some statistically significant evidence of findings that both align with and contradict the original objectives (outcomes) set out in the NCS theory of change. These are summarised below.

Findings for outcomes relating to life skills and independent living were mixed, with evidence of an increase in leadership skills, teamwork skills in relation to helping others and asking for help, and problem solving. However, the analysis also found evidence of negative impact estimates for the participant group relative to the comparison group, on outcomes including responsibility and empathy.

For social action outcomes, findings show some evidence of a positive impact on the number of the different types of volunteering in which participants engaged, relative to the comparison group.

Social cohesion outcomes were again mixed, with findings indicating that NCS had led to lower levels of social inclusion among participants, relative to the comparison group. However, there was evidence of an increase in the perceived importance of social mixing, for example, learning about someone’s culture, standing up for the rights of others, and treating people with respect, regardless of their background.

It is positive that participation in the residential programme has supported improved outcomes in some areas, but they also present a conflicting picture with some negative findings that are harder to explain. It may be that there are some outcomes that are more realistic or plausible to be achieved by certain forms of provision, and these should be prioritised for measurement in future programmes. For example, it may be that resilience, empathy and emotion management are not likely to be affected by a 2 to 4 night residential intervention. Or it may be that participation in NCS exposed participants to different people and ideas which heightened their awareness of challenges or difficulties in social inclusion, hence scoring themselves lower in the follow-up.

It is important to note that these findings consider only the residential service line as the impact survey approach was difficult to implement consistently for the community open to all service line. Hence these impact evaluation findings may under-represent the true impact of the new NCS model as a whole.

Reflections and recommendations

Reflecting on the above evidence, this report makes a number of key recommendations for the design, implementation and evaluation of similar future programmes.

Future youth programmes may benefit from flexible, multi-route engagement models that accommodate diverse participation preferences and organisational capacities.

The new diversified, ‘year-round’ NCS model was perceived as more inclusive by design; both as a way to encourage smaller community organisations to deliver experiences, and to engage a wider range of young people, including those who may struggle to engage with more traditional residential experiences.

Grant funding models should be utilised to catalyse regional partnerships and leverage local expertise for high-quality youth provision.

The community open to all service line successfully stimulated new partnerships and delivery innovations through its regional grant structure. This structure allocated one grant per region and encouraged local organisations to team up and work together to bid for and deliver the service line in their region. This approach could provide a useful foundation for localised National Youth Strategy delivery.

Implementation timelines must be realistic and allow adequate lead-time for partnership building and contracting processes.

Despite achieving Year 1 experience targets, delayed contracting created significant operational pressures and financial strain for delivery partners throughout their supply chains. These delays were particularly challenging for smaller providers with limited cash flow resilience.

Data sharing systems and cross-referral mechanisms should be embedded from programme inception, to maximise participant impact through multi-service engagement.

The absence of referral pathways between service lines, hindered by the absence of a unified MyNCS platform, led to missed opportunities to enhance programme coherence and increase individual participant outcomes through co-ordinated provision.

Longer-term funding commitments are essential for programme stability, staff retention, and effective partnership development.

Year-on-year funding uncertainty hindered delivery organisations’ ability to retain experienced staff, invest in innovation, and build sustainable relationships with schools and other partners. Payment-by-results mechanisms[footnote 4] appeared to create financial risks for some residential providers, especially given high Year 2 attrition rates beyond partner control.

Activities with an employability focus must be designed to feel engaging and aspirational, while adding clear value beyond existing educational provision.

While the programme showed positive impacts on leadership skills, confidence, and problem-solving, employability outcomes were inconclusive. Qualitative findings indicated that ‘Boss It’ elements were less popular among residential participants than interactive ‘Live It’ and ‘Change It’ components, suggesting the need for more appealing and less ‘classroom based’ approaches to work-readiness support.

Evaluation frameworks should align with programme delivery models and organisational capacities to ensure meaningful data collection and impact assessment.

The structured residential service line was well-suited to centralised evaluation approaches, whereas flexible community and digital programmes required more proportionate monitoring systems. Smaller grassroots organisations faced burden from ongoing monitoring and evaluation requirements that did not match their operational capabilities or the tailored nature of their provision.

Introduction

About National Citizen Service

The National Citizen Service (NCS) was a key youth programme for 16 to 17-year-olds in England for over a decade. Until 2019, NCS delivered intensive part-residential programmes lasting 2 to 4 weeks twice per year but due to the Covid-19 pandemic, significant changes were made to the programme. From 2023, the NCS programme model changed from a ‘one size fits all’ part-residential experience to a year-round model with three distinct groups of activities (or ‘service lines’) with varied interventions or ‘experiences’ for young people:

-

residential experiences: trips away from home for 2 to 4 nights. Residential experiences were delivered in different strands, depending on their varying focal points: ‘Boss it’ focused on employability, ‘Live it’ on life skills and ‘Change it’ on social action

-

community experiences: non-residential experiences delivered locally. These included ‘open to all’ experiences (regular year- round activities open to all young people) and ‘targeted’ experiences (those targeting a specific demographic, setting or geography)

-

digital experiences: structured online experiences, ranging from self-serve articles to interactive online games

In November 2024, the Secretary of State for Culture, Media and Sport announced her intention to wind down NCS programmes from March 2025, and formally close the delivery body, the NCST. The Royal Charter, which incorporated the NCST, was surrendered in July 2025.

NCS evaluation approach

A consortium of external evaluators led by Verian, and including The Social Agency (previously known as Basis Social) and London Economics, delivered a national evaluation of NCS. The evaluation ran from February 2023 to August 2025 and comprised three work streams:

-

process evaluation: to understand how the new programme model was implemented on the ground and to identify best practice, as well as risks and challenges

-

impact evaluation: to measure whether the new programme model had the desired effects

-

economic evaluation: to estimate the social and economic value that the new programme model generated. The economic evaluation was only conducted for Year 1 of the programme 2023 to 2024 and focused on the residential service line. It was not conducted for Year 2. Findings from the economic evaluation are included in the technical annex.

Process evaluation

The process evaluation employed both quantitative and qualitative methods.

Verian led the quantitative component, which intended to analyse monitoring data gathered from NCST’s monitoring systems to answer questions about participant profiles and their journeys through the programme. However, data availability was limited and primarily covered the residential service line. Community open to all data was not collected directly into the NCST’s Salesforce system and required manual processes. No monitoring data was collected directly by NCST for community targeted or digital experiences, beyond overall experience volumes.

The Social Agency led the qualitative component, which covered all service lines and was carried out during Years 1 and 2 of programme delivery, permitting learning and improvement over time. This included:

-

forty-two online interviews with delivery partner staff responsible for both the design and implementation of NCS experiences and for managing relationships with NCST (referred to hereafter as ‘strategic leads’)

-

ten half-day site visits to NCS residential and community open to all experiences, during which researchers observed programme activities and spoke to delivery staff and young people

-

twelve online interviews with young people who had taken part in residential experiences

Research questions for the process evaluation included:

-

Are new service lines being implemented as intended, and how well has implementation gone?

-

How well is the relationship between NCST as a grant funder / contractor and the partners delivering the programme working?

-

What has been the programme’s reach and level of engagement across different service lines and activities?

-

What do young people think about the various experiences on offer?

Further information about the process evaluation methodology, sampling and analysis is available in the technical annex.

Impact evaluation

The impact evaluation was led by Verian and used a rolling baseline survey with NCS participants (the ‘treatment group’) administered online by NCST, and an online comparison survey of young people with similar characteristics to NCS participants but who did not participate in NCS (the ‘comparison group’) administered 4 to 9 months after baseline. The sample for the comparison survey was drawn from the National Pupil Database (NPD).

The impact evaluation employed a difference-in-difference approach, which compares the change in results of the treatment and comparison groups between the baseline and follow up surveys. The assumption behind difference-in-difference is that if the programme had no impact on its participants, then the treatment group trend between the baseline survey and the follow up survey should be very similar to the trend for the comparison group. When a change between the baseline survey and the follow up survey for the treatment group is different from the comparison group trend, this suggests that participating in the NCS programme has had a statistically significant impact.[footnote 5]

Where a statistically significant impact has been observed, an ‘impact estimate’ has also been provided that describes how different the results were between the treatment and comparison groups, and therefore how much impact the NCS programme has had on the results. In some cases, statements or questions have been combined into one ‘summary outcome measure’ for ease of analysis.

Research questions for the impact evaluation included:

-

Did the programme achieve its intended outcomes?

-

Did the programme achieve its intended impacts?

-

To what extent did the new NCS model cause or contribute towards observed outcomes?

For more information on impact methodology, please refer to the technical annex. Some considerations to aid in interpreting the impact evaluation findings in this report can be found below:

-

Coverage of NCS service lines: the data presented for the impact analysis in the main report only covers the residential service line. Impact analysis for the limited community open to all data is found within in the technical annex

-

Monitoring data collection: NCST data systems were not designed to record whether individuals had participated in more than the residential service line, the specific aspects of the residential service line they had participated in (e.g. Boss It/Live It/Change It) or how delivery varied by provider. This limited the extent to which impact analysis findings can be confidently linked to specific features of the programme design or delivery

-

Timing of survey fieldwork: the timetable of the evaluation meant that the follow-up surveys were mainly conducted during late spring, including over the exam period. This may have influenced respondents’ answers to some degree, for example young people experiencing increased stress in this experience may have influenced responses to wellbeing questions. Moreover, the time between baseline and follow-up varied from four to nine months, meaning effects were not captured consistently for all respondents. However, further analysis of the outcomes data suggests that these inconsistencies in timing generally do not substantially influence the impact estimates, see technical annex for further details

-

Survey non-response: not all NCS participants took part in the baseline survey. The analysis attempts to account for non-response using survey weights (see technical annex) to ensure the findings are representative of NCS residential participants as far as possible. However, there may still be residual differences between the young people who took part in the survey and those who did not take part which are not fully accounted for in the analysis

-

Unobserved differences between the participant and comparison groups: Propensity Score Matching (PSM) was used to attempt to account for differences between the two groups which could influence the results. However, some differences may remain. For example, respondents’ answers could be affected by personal relationships, wider economic and social pressures, and other factors. These factors could influence the findings to the extent they affect the participant and comparison groups in different ways

-

Statistical power: in general, the impact analysis is powered to reliably detect impacts of around 0.10 points on the standardised scales presented in this report. Effects smaller than 0.10 points may still be present, but the evaluation may not have sufficient statistical power to identify them with confidence. We consider this impact analysis to have sufficient power to detect any impacts likely to have occurred, for example the 2019 evaluation[footnote 6] found impacts of over 0.10 across outcomes relating to life skills and independent living.

Implementation and delivery

Reflections on the new model

In principle, the new model was recognised as a positive step in the right direction. The decision to diversify the NCS service lines was seen positively by delivery partners overall. Strategic leads engaged through the evaluation broadly endorsed the ethos of the new programme model, particularly the introduction of community ‘open to all’ and ‘targeted’ experiences. These were seen as making NCS more inclusive by design. Specifically, they facilitated the introduction of more varied experiences that worked for a broader set of young people (including those who may not typically have wanted to take part in a traditional residential experience) and offered greater flexibility for delivery partners (for example, by enabling smaller community organisations to get involved in programme delivery). Some organisations were using NCS funding to helpfully ’scale up’ existing programmes to reach greater numbers of young people, and in some instances to pilot new types of interventions.

Of note is that this flexibility meant community experiences in practice could end up looking and feeling very different to one another – for example, in terms of content and activities, the routes through which participants were recruited (from single colleges to multiple sources), and the period over which a programme was run (whether more intensive activity over a single weekend, or more spread out over the course of several months). Whilst this flexibility was embraced, it has had implications for the way in which community service lines can be evaluated. In effect, it means trying to compare very different activities against the same outcome.

Delivery partners still valued and embraced the residential aspect of NCS, the cornerstone of the old programme. They felt that participation was valuable for young people but recognised that there was only so much impact a shortened 2 to 4 night offer could have, relative to previous iterations of the programme (which involved 3 to 4 week programme experiences).

Strategic leads also saw the inclusion of the new digital service line as a critical part of reaching and engaging more young people. This was about targeting young people where they were at and using media that was more familiar to them.

Implementation challenges

There were some notable challenges to programme rollout from an operational aspect, though some of these were overcome in time for Year 2 delivery. Learning and improving ‘as you go’ has felt to be an important underlying principle across the new programme’s implementation, especially for new (community and digital) service lines.

Delays to programme roll out and tight delivery timelines were identified as key challenges during Year 1. These were primarily driven by prolonged contract negotiations between NCST, Ingeus and Quantum 360 (NCST’s partner procurement agency) post-award, and ultimately reduced the window that delivery partners then had to recruit to, and design, experiences. This was seen to have a knock-on effect on quality - for example, by reducing the choice of accommodation or transport suppliers that could be procured. These contract negotiations only happened at the beginning of the programme. By Year 2, strategic leads were confident that any knock-on effects from the delays had been resolved, contributing to improved implementation and delivery of experiences later in the programme.

The lack of a centralised marketing function within the new model, compared to the old programme, presented some initial challenges for delivery partners (an organisation called Ingeus led on marketing and recruitment for the residential service line, but community and digital delivery partners marketed their own experiences). This was especially difficult for those organisations without a central marketing function or in-house expertise, or who were new to NCS and potentially lacked the strong regional connections into institutions like schools (a key route to recruiting young people). It was also seen to result in a lack of a clear messaging to young people and their sponsors about the new model. While a significant challenge in Year 1, by Year 2 delivery partners had adapted to new ways of working and were confident in their ability to achieve targets.

The digital service line proved particularly challenging to implement. Most digital experiences did not go live until Year 2, and some only at the very end of the programme. While it was always planned for digital experiences to come on stream at different points during the programme, the delays were much more significant than originally expected. These delays were partially due to NCST tendering for experiences later than planned. This was an internal matter for NCST and so out of scope for this evaluation. Post-tender, these delays were compounded by a long and complex contracting process. According to strategic leads, this was symptomatic of NCST’s lack of experience procuring digital assets at the outset of the programme, which improved over time. They also attributed it to the fact that NCS is government-funded, which resulted in digital delivery partners having to demonstrate additional certifications and competencies (for example, Cyber Essentials) beyond what is normal for them.

Performance against targets

Although there were challenges in implementation, by the end of Year 2, NCS had over-achieved against its overall experience participation target, on all service lines. However, one key reason for over-achievement was the digital service line, which was close to target in Year 1, but falling behind in year 2 (at just under 13,000 experiences in December 2024) until the final quarter when the Neohaven Noodles game was launched. This generated an additional c.280,000 experiences.[footnote 7]

Table 1: NCS experiences delivered against target by service line, 2023 to 2025

| Service line | Target | Actual |

|---|---|---|

| Overall | 261,000 | 601,068 |

| Residential | 46,000 | 45,456 |

| Community | 140,000 | 257,740 |

| Digital | 75,000 | 297,872 |

Experiences of delivery

Programme-wide offer

Whilst the design of the new model was viewed positively, in practice interviewees felt that the programme lacked cohesion. The new programme was initially envisaged as a programme-wide ‘year-round’ offer, where young people could engage in several different programme experiences over time, moving between service lines. Strategic leads reported that this integrated offer had not materialised in practice.

This was considered a missed opportunity, since the various service lines were seen to offer different, but complementary, benefits to young people. For example, community experiences, especially when delivered over longer timeframes, could offer more time to embed outcomes, and give young people more agency over their experiences. Meanwhile, the residential service line was seen as uniquely suited to improving confidence because it took young people into a new, unfamiliar environment, where they could mix with young people from different areas.

Several factors affected young people’s movement between service lines. Firstly, the promise of MyNCS as a single gateway through which young people could learn about and access different service lines did not materialise (understanding the reasons for this was out of scope for this evaluation). MyNCS was intended as an online ‘one stop shop’ platform for young people to register their details and contact information, and to browse and sign up for experiences. Service line providers would then receive contact details for registered young people to take forward. As a result, delivery partners had to undertake a lot more of their own marketing and recruitment to meet targets than was originally intended.

This was further exacerbated by delivery partners being unable to compliantly share young people’s personal data as a way to cross-market experiences (something that could arguably have been more effectively planned for when designing registration and consent forms).

Qualitative research with young people attending residential experiences anecdotally supports this finding. Most of the participants in the (albeit small, and not representative) sample were unaware that there were multiple service lines offering different types of experiences.

There also appears to have been an issue of knowledge sharing between delivery partners, even within a single region. This could make it difficult for delivery partners to promote and cross-sell other local experiences. Some strategic leads said that this problem improved over time - for example, the NCS national conference and regional events had served as useful opportunities to get to know other delivery partners working in their areas. However, others remained unaware of who else was operating in their region, even late into Year 2. There was also a view that programme funding was insufficient to cover the work required for delivery partners to cultivate relationships and link up experiences.

As such, evidence of multi-service line participation tended to be focused where the same delivery partners were responsible for both residential and community experiences in the same region. This set-up enabled organisations to clearly communicate to young people about other experiences they could take part in and provide assurances that they would be able to do follow-on experiences with friends they had made on their initial NCS experience. According to staff involved in one site visit, staying connected with friends made on NCS was a key motivator for young people to want to take part in follow-on experiences.

Finally, there was relatively little read across between in-person and what were intended as more ‘year round’ digital experiences, as a way to drive cumulative impact, due to the delays to digital experiences being rolled out noted previously.

Impact of the funding model

Providers commented that the amount of funding relative to the requirements and ambitions of the NCS programme was comparatively small. To compensate, there were examples of delivery partners having to ‘plug’ NCS grant funding with additional money from elsewhere, or streamlining delivery, for example, by using full-time staff to deliver programmes because they could not afford to recruit additional seasonal staff. The nature of the two-year contract was also felt to discourage investment and create uncertainty. There were reports that it could make it harder to recruit and retain staff for the long-term.

Some residential delivery partners engaged through the evaluation also reported feeling financially exposed by the new contract ‘pay-mech’. Specifically, it was felt to introduce greater financial risk compared to previous NCS programmes. Delivery partners were effectively expected to invest money into programme planning whilst receiving much less than previous contracts if they did not hit target places. This was seen to act as a disincentive for investing in the way they might otherwise have wanted to.

These funding issues could be further compounded by challenges with attrition for in-person service lines. Year 2 interviews highlighted an ongoing challenge with young people not turning up to, or dropping out of, residential and community experiences. This was reported as being driven by factors such as young people feeling too anxious to participate, or inadequate public transport links in some regions. For the residential service line, young people receiving bursaries were also felt to be a significant driver of attrition. The bursary scheme’s purpose was to remove financial barriers to participation. However, according to strategic leads, by reducing these barriers the scheme effectively reduced the financial incentive to turn up, since parents/guardians had not paid for the experience.

Monitoring and evaluation requirements

When it came to NCST’s monitoring data reporting requirements, views were fairly mixed – they were regarded as more than some other grant providers look for, but less than others. Certainly, they could be seen as quite burdensome for some of the smaller grassroots organisations engaging with the new programme model. In practice, data requirements and monitoring systems varied by service line (for example, for residential service lines data was collected via a cloud-based system, Salesforce, but for community service lines manual data entry via Google spreadsheets was required). This ultimately made producing a reliable and rounded picture of NCS engagement across service lines challenging.

In terms of the DCMS-commissioned NCS evaluation, the impact evaluation required young people to complete a baseline and follow-up survey, administered by NCST on a rolling basis based on participant information supplied by delivery partners. This approach was well-suited to the residential service line, which involved discrete cohorts of young people participating in a relatively standardised intervention (2 to 4 nights away from home), delivered by seasoned NCS delivery partners using a common set of well-established systems and processes. By contrast, the community service line was much more flexible by design. Delivery partners developed their own delivery models and delivered a much more diverse set of experiences that made a one-size-fits-all evaluation approach difficult. In many cases, these experiences were also delivered by local grassroots organisations with little capacity or experience of collecting and managing data. These factors made community service line data collection difficult and ultimately resulted in insufficient sample for conclusive impact analysis.

Partnership working

Despite some of these operational challenges, it should be stressed that views towards NCST as a working partner were in the main very positive. They were generally regarded by the strategic leads interviewed as a flexible and supportive partner. NCST was praised for how it tried to support partners to iron out teething problems, especially during Year 1, and in listening and responding to their partners’ needs. Individual grant managers appeared to be a key asset for building and encouraging such positive relationships. The level of senior engagement from NCST (including regular conversations with the chief executive and chief operations officer) was also seen positively. This demonstrates the value of open communication in running grant programmes and ensuring strong relationships between grant givers and grantees.

Our grant manager is brilliant. He’s local to the region and has great knowledge and understanding of NCS delivery because he used to be involved in it himself.

– Community open to all strategic lead

The new programme model also appears to have facilitated more positive working within and across the youth sector. Through the interviews, it was apparent that community experiences had enabled delivery partners to take a lead in setting up their own consortia and in cultivating local networks. For example, several strategic leads who had built new regional consortia to deliver open to all experiences said that they had built stronger relationships with others in their region as a result. They also saw regional partnerships continuing beyond the 2023 to 2025 NCS programme – a potential legacy of the new programme model.

In the initial stages we were going to be a delivery partner, but we had such a positive response to the consortium call out that we stepped back to manage the partnership. We’re very familiar with partnership working now. Even with NCS going, we’re going to continue with this partnership.

– Community open to all strategic lead

Adopting a design-led approach to digital experiences

Challenges with the digital service line have offered delivery partners, NCST and DCMS useful learnings. In particular around how to procure high quality youth-focussed digital experiences. Strategic leads observed that NCST initially approached the digital service line with preconceived ideas of the types of experiences they wanted to create (for example, a series of YouTube videos). They perceived this approach as sub-optimal, because it risks making assumptions about what will be most engaging and impactful for young people. Strategic leads recommended instead that NCST contract suppliers to deliver a process for designing digital experiences focussed on specific objectives and by working in collaboration with young people, but without prescribing what the outputs of that process need to be. This was the approach used by NCST later in the programme, resulting in some of the programme’s most successful digital experiences, including Neo Haven Noodles. The Neo Haven Noodles game was co-designed with young people to support improvements in financial literacy and attracted almost a quarter of a million participants in just over two months.[footnote 8]

Social mixing

Residential experiences were seen as more effective for promoting social mixing as they brought together individuals from different areas. The community service lines were seen as being less suitable to cultivating genuine social mixing, because of their more local focus and (for targeted experiences) their focus on specific cohorts of young people (for example, SEND). This suggests that delivery partners tended to think of social mixing in a limited way, primarily in relation to recruitment rather than through mixing activities or engagement with wider professionals/organisations, for example. The degree and mechanisms by which digital experiences enabled social mixing varied between experiences. Some were designed for young people to complete on their own (for example, a web-based game), meaning no opportunities for social mixing. Others involved group-based working, such as a hybrid online and in-person enterprise skills courses, providing some opportunity for social mixing.

Young people’s experiences of NCS

Overall, young people taking part in NCS residential and community open to all service line were positive about their experience of the programme. Of those who completed the follow-up survey:

-

83% residential participants and 74% of community open to all participants reported an enjoyable experience

-

81% residential participants and 68% of community open to all participants said the experience was worthwhile.[footnote 9] Of the residential participants, 36% considered the experience to be completely worthwhile)[footnote 10]

Feedback from young people interviewed during site visits and interviews also demonstrated broadly positive feedback.

Across programme experiences, the social aspect of NCS was a key driver of young people’s enjoyment of the programme. Young people engaged through qualitative interviews shared how much they enjoyed opportunities to socialise with their friends, meet new people, and have new and exciting experiences together. They felt these interactions had increased their confidence in social situations, plus developed their team working and communication skills. Some young people also reflected on how meeting new people had improved their understanding of people from different backgrounds to them. This was more of a theme during interviews about residential experiences; possibly because young people are recruited from a broader catchment area, as opposed to concentrating on a local area.

Speaking to people of all backgrounds and ages, that was very eye-opening. There was a lot of things during the NCS trip that I haven’t ever seen before because I’ve been quite sheltered all my life… seeing people from all over and doing things that I’ve never done before, the fact it was all new, was helpful for understanding different things.

– Young person, residential experience

The quality of staff and volunteers also played a critical role in making experiences enjoyable and worthwhile. The young people interviewed widely praised them as fun, supportive and relatable, engaging with them in a genuine and authentic way. For example, on residential experiences there were examples of how staff had encouraged young participants to speak to new people in the group, usually by breaking them up into teams with new people each day. As a result, even when a group of friends went to NCS together, they ended up speaking with new people and working with them through challenges and activities each day.

In terms of programme content, experiences which offered young people variety and choice of activities were particularly valued. They also enjoyed the sense of excitement and novelty offered by more outdoors-y, adventure-based activities, like archery or kayaking. These sorts of activities forced them to step out of their comfort zone. This was reinforced through the strategic lead interviews, where it was noted how young people are looking for a sense of adventure, rather than traditional classroom-based activities.

New things don’t always have to be as scary as your brain makes them. Sometimes our brain overthinks, makes things scary, but once you step out of your comfort zone you realise it’s not that bad.

– Young person, residential experience

Providers adapted their programmes accordingly. For example, several open to all and targeted strategic leads described how, in Year 1, they structured their experiences so that young people would move through each NCS objective sequentially, spending two weeks on activities focussed on one objective, and then two weeks on another, and so on. Feedback from young people called for more agency over what types of activities they focused on at different points, and also more variety at any given point. In response, some strategic leads transitioned in Year 2 to a so-called ‘dovetailed’ model, which mixed multiple objectives into single blocks of activity. Subsequent feedback from young people suggested this approach worked much better for them.

This was similar for residential providers. For example, young people taking part in the Year 1 residential ‘Boss it’ and ‘Change It’ experiences felt that these featured too many overtly educational activities, and they wanted more adventure-based activities. In Year 2, delivery partners responded by blending adventure-based activities, like abseiling, into their experiences – for example, by doing a morning of outdoor, adventure-based activities and an afternoon of project-based learning, and adjusting the focus of reflection time by encouraging young people on ‘Boss it’ experiences to think about how they could present their adventure activity in a job interview or CV. Strategic leads believed this blended approach ensured the experience overall was more fun and exciting for young people. Interviews with young people also suggest these changes were received positively, with several ‘Boss it’ and’ Change it’ participants highlighting adventure-based activities as the most enjoyable parts of their experience.

The young people interviewed also enjoyed and recognised the impact that employment and social action focussed activities could provide. For example, those who took part in a ‘Change it’ residential programme recalled feeling more aware of challenges faced by their local communities as a result. They enjoyed the opportunity to debate current issues with their peers. Participants taking part in ‘Boss it’ residential experiences similarly felt they had learnt some important career skills, such as developing business proposals, leadership, and presenting ideas. Feedback suggests that more could have been done to develop these outcomes further, through more support in helping participants use these skills in the real world - for example, by signposting them to work experience and volunteering opportunities in their local area.

Outcomes for young people

Whilst young people’s qualitative feedback on NCS was largely positive, results from the impact evaluation for the residential service line are more mixed. This chapter presents impact analysis findings across both years of the evaluation for the residential service line only. Limitations with the standalone analysis of the community open to all line (i.e small sample sizes and a restricted time period) mean that findings should be treated as indicative. Nevertheless, there are positive findings within this analysis, which suggest community-based approaches may be beneficial for young participants. Findings are presented in the technical annex.[footnote 11]

In this chapter, the impact estimates have been given in all cases where a statistically significant impact was found.[footnote 12] All results, including those that are not statistically significant are reported in the technical annex.

Interpreting impact evaluation findings

The outcomes achieved for young people participating in the NCS programme were measured through an impact evaluation. Impact surveys were conducted with young people participating in the residential and community open to all service lines, as well as a comparison group drawn from the National Pupil Database.

Both treatment and comparison groups were surveyed before the NCS group had started their NCS experience (the baseline survey) and were surveyed again between four and nine months later (the follow up survey). The treatment group consisted of 2,984 young people that participated in the NCS residential programme between July 2023 and November 2025 and completed both a baseline and follow up survey. The comparison group consisted of 2,949 young people who completed both a baseline and follow up survey. This comparison group was sampled to match the treatment group as closely as possible on four key characteristics: age, gender, ethnicity and deprivation. Further matching was undertaken using Propensity Score Matching to make the two groups as similar as possible.

Difference-in-difference impact findings

Difference-in-differences compares trends between a treatment group and a comparison group. The key assumption is that the change observed for the comparison group is the same as the change would have been for participants had they not taken part in NCS. Under this assumption, any difference in these trends can be attributed to the effects of NCS. If the change between baseline and follow up for the treatment group is significantly different to the change between baseline and follow up for the comparison group, this suggests that participating in the NCS programme has had either a positive or negative impact.

Figure 1: Example summary measures A to C: positive impact estimates

Figure 1 provides examples of what positive impact estimates can look like. For score A, the NCS treatment group has seen an increase, whilst the comparison group experienced a decrease. For score B, both the NCS treatment group and the comparison group have evidence of an increase, but the NCS group have increased much more than the comparison group. For score C, both the NCS and comparison group both have evidence of a decrease, but the NCS treatment group decrease is much less than the comparison group. This suggests that the NCS programme has offset the general downward trend.

Figure 2: Example summary measures D to F: negative impact estimates

Figure 2 shows examples of what negative impact estimates can look like. For score D, the comparison group has increased, but the NCS treatment score has decreased. For score E, both groups have seen a decrease, but the NCS treatment group decrease is much greater than the comparison group. For score F, both groups have seen an increase in the impact measure, but the comparison group has increased much more than the NCS treatment group. This suggests that the NCS programme has negatively offset a general increasing trend for its participants and is therefore a negative impact estimate.

Figure 3: Example summary measures G to H: No significant impact observed

Figure 3 outlines examples where there has been no impact of the NCS programme, as the trend is similar to the comparison group. For Score G, both treatment and comparison group increased at a similar level. For Score H, both treatment and comparison group declined at a similar level.

Outcome measures

The impact survey contained multiple statements or questions to measure over 60 different outcomes for participants. Summary outcome measures were developed for ease of analysis. These summary outcome measures were created by averaging individual measures.

For more information on the approach to difference-in-difference analysis and summary outcome measures, please refer to the technical annex.

Life skills and independent living

NCS aimed to promote life skills and independent living, addressing the ‘skills gap’ and supporting young people to gain the skills they need for work and life. Essential life skills such as teamwork, problem-solving and resilience were expected to be critical for future employment. The ‘Live It’ residential strand specifically aimed to build these skills.

Key activities of the residential programme, such as action and reflection models, youth-led activities, perspective-taking and team building exercises, were intended to facilitate short-term outcomes such as greater connections and networks, increased confidence and better essential skills. This was expected to facilitate the achievement of outcomes such as increased confidence in their own essential skills and being capable of managing difficult situations.

The NCS impact survey gathered data to understand young people’s confidence in their own essential skills, including confidence and resilience. Survey respondents were asked how much they identified with a series of statements relating to life skills and independent living. The questions were all asked on a scale of 0 to 10 or ‘Never’ to ‘Always’ and referenced ten essential skills, summary outcome measures for which are shown in Table 2.

Table 2: Composition of summary outcome measures for essential skills

| Summary outcome measure | Outcome measure |

|---|---|

| Teamwork A | - I feel confident when meeting new people - I find it difficult to work with people if they have different ideas or opinions to me - I try to see things from other people’s viewpoints |

| Teamwork B | - I seek help from others when I need it - I go out of my way to help others - I remind people to do their part |

| Leadership | - I like being the leader of a team |

| Listening and speaking | - I am able to explain my ideas clearly - I try to see things from other people’s viewpoints - I feel confident speaking in public - I find it hard to express myself to others - I find it hard to speak up in a group of people I don’t know well |

| Creativity | - I like coming up with new ideas for ways to do things - I feel confident about having a go at something new |

| Emotion management | - I bounce back quickly from bad experiences |

| Empathy | - I understand how people close to me feel - It is easy for me to feel what other people are feeling |

| Responsibility | - People can count on me to get my part done - I do the things that I say I am going to do - I take responsibility for my actions, even if I make a mistake - I do my best when an adult asks me to do something |

| Initiative | - I give up when things get difficult - I work as long and hard as necessary to get a job done |

| Problem-solving | - I start a new task by brainstorming lots of ideas about how to do it - I make step-by-step plans to reach my goals - I make alternative plans for reaching my goals when things don’t work out - I am good at managing time when I have to meet a deadline |

Overall, the findings are mixed for essential skills. The analysis found no statistically significant evidence of impact for summary measures relating to listening and speaking, creativity and initiative. It also found statistically significant evidence of negative impact estimates for the participant group relative to the comparison group, on summary measures including responsibility (impact estimate -0.21)and empathy impact estimate (-0.08).

There was statistically significant evidence of an increase for participants, relative to the comparison group, on the following summary measures: leadership, teamwork skills related to asking for help and helping others (Teamwork B), and problem solving. This indicates a positive impact of the NCS for these skills, with more detail below.

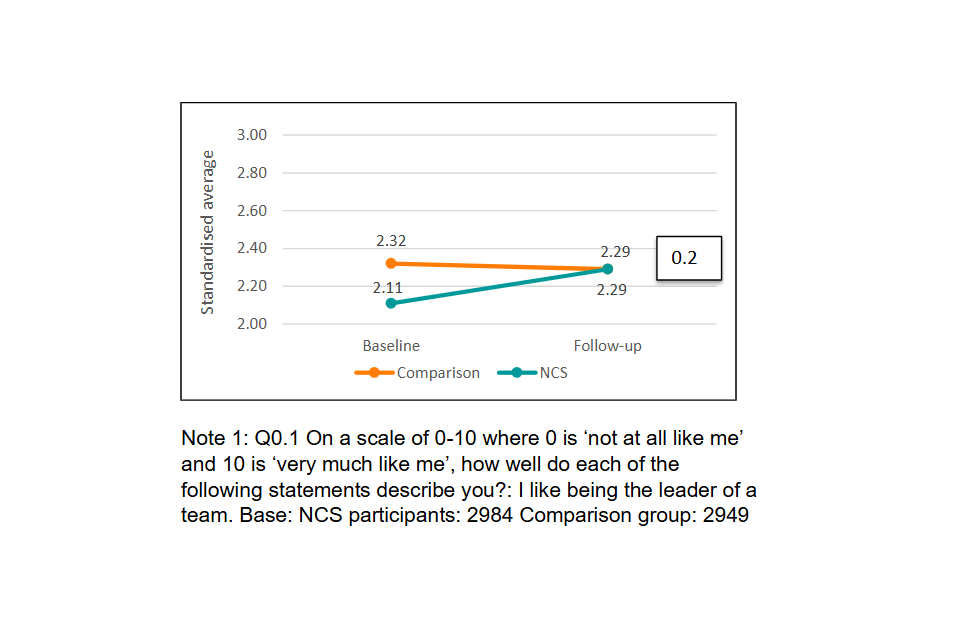

Leadership skills

Results show evidence of a statistically significant increase in leadership skills (see Figure 4), among NCS participants, with an impact estimate of 0.2. This indicates an improvement in NCS participants’ confidence in being a team leader, relative to the comparison group.

Figure 4: Change in the mean score on liking to be a team leader[footnote 13]

| Title | Impact estimate | Comparison baseline | Comparison follow-up | Treatment baseline | Treatment follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Figure 4: Change in the mean score on liking to be a team leader | 0.2 | 2.32 | 2.29 | 2.11 | 2.29 |

Note 1: Q0. 1 On a scale of 0 to 10 where 0 is ‘not at all like me’ and 10 is ‘very much like me’, how well do each of the following statements describe you?: I like being the leader of a team. Base: NCS participants: 2984 Comparison group: 2949

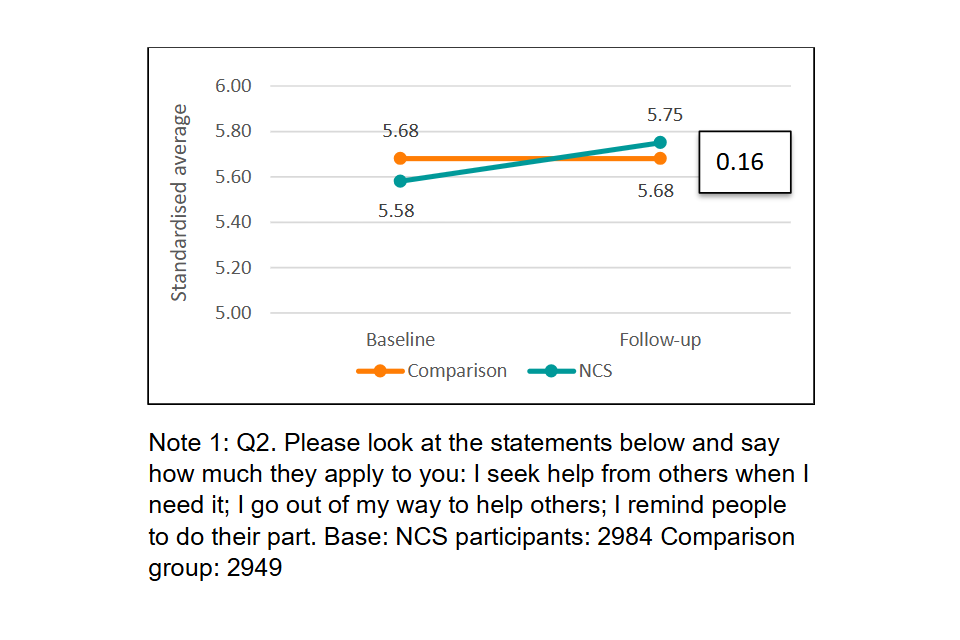

Teamwork

There are several teamwork questions within the impact survey and for analysis these have been grouped into two summary measures. Teamwork A covers statements about working with new and different people and Teamwork B relates to seeking help and helping others (see Figure 5).

Findings are mixed across the two measures with Teamwork A showing an impact estimate of -0.12 relative to the comparison group. By contrast, results demonstrate a statistically significant increase in the summary measure Teamwork B, i.e. seeking help and helping others, with an impact estimate of 0.16 (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Change in the mean score on teamwork skills related to seeking help and helping others (Teamwork B)[footnote 14]

Note 1: Q2. Please look at the statements below and say how much they apply to you: I seek help from others when I need it; I go out of my way to help others; I remind people to do their part. Base: NCS participants: 2984 Comparison group: 2949

| Title | Impact estimate | Comparison baseline | Comparison follow-up | Treatment baseline | Treatment follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Figure 5: Change in the mean score on teamwork skills related to seeking help and helping others | 0.16 | 5.68 | 5.68 | 5.58 | 5.75 |

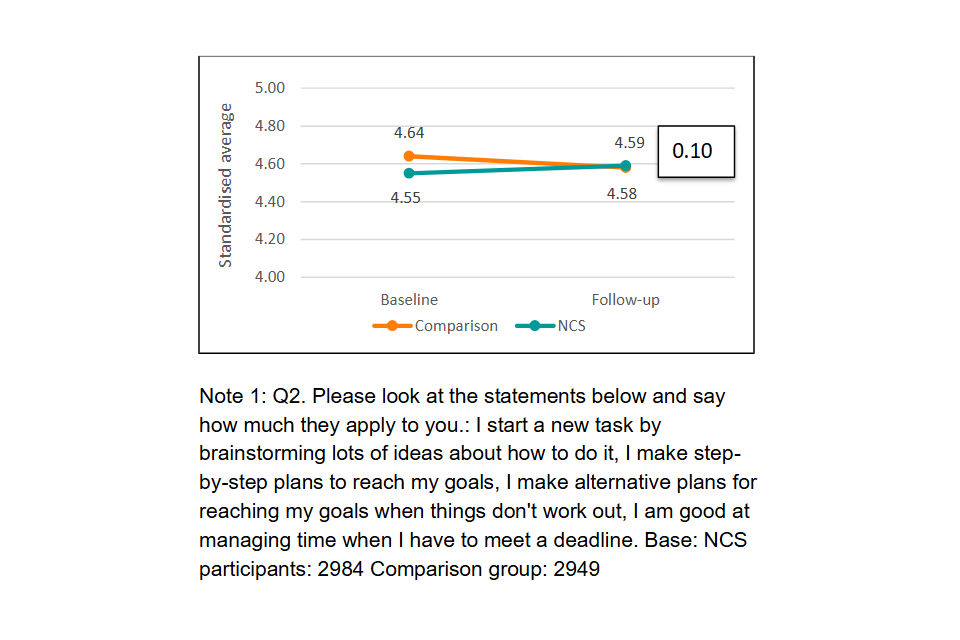

Problem solving

Findings show statistically significant evidence of an increase of 0.1 on this measure, indicating a positive impact of the NCS for participants on problem solving skills, see Figure 6).

Figure 6: Change in the mean score on problem solving skills[footnote 15]

Note 1: Q2. Please look at the statements below and say how much they apply to you: I start a new task by brainstorming lots of ideas about how to do it, I make step-by-step plans to reach my goals, I make alternative plans for reaching my goals when things don’t work out, I am good at managing time when I have to meet a deadline. Base: NCS participants: 2984 Comparison group: 2949

| Title | Impact estimate | Comparison baseline | Comparison follow-up | Treatment baseline | Treatment follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Figure 6: Change in the mean score on problem solving skills | 0.10 | 4.64 | 4.58 | 4.55 | 4.59 |

Employability and work readiness

Unemployment is a problem that disproportionately affects young people.[footnote 16] Increasing employability as well as ensuring access to work opportunities, information and guidance is vital to ensuring young people can access jobs that suit their talents and aspirations.

The NCS residential programme, specifically the ‘Boss It’ element, was designed to support young people to enhance their employability and work readiness. Additional activities such as the inclusion of employers in delivery were intended to lead to outcomes such as greater confidence in practical work skills (e.g. interviewing and CVs) and awareness of the pathways and opportunities open to them. This in turn was expected to lead to increased feelings of optimism about their prospects and future employment.

Overall, the impact findings around employability and work readiness show no statistically significant evidence of impact on any of the relevant summary outcome measures.

Volunteering and social action

For the NCS programme, social action and volunteering was expected to boost educational attainment, and support participants to develop key employability skills. Involvement in these activities was also intended to help young people to develop important life skills. Wider research and evidence also suggest that social action and volunteering can support mental health.[footnote 17]

The NCS residential programme, with its ‘Change It’ element, was designed to support young people to get involved in volunteering and social action. Additional activities such as working alongside community partners to shape and implement social action were intended to lead to outcomes such as greater confidence in practical skills for social action and a greater awareness of the challenges facing their community and how to make a difference (civic engagement). The intended impact of this was that young people would feel better able to have an impact on the world and are more likely to volunteer.

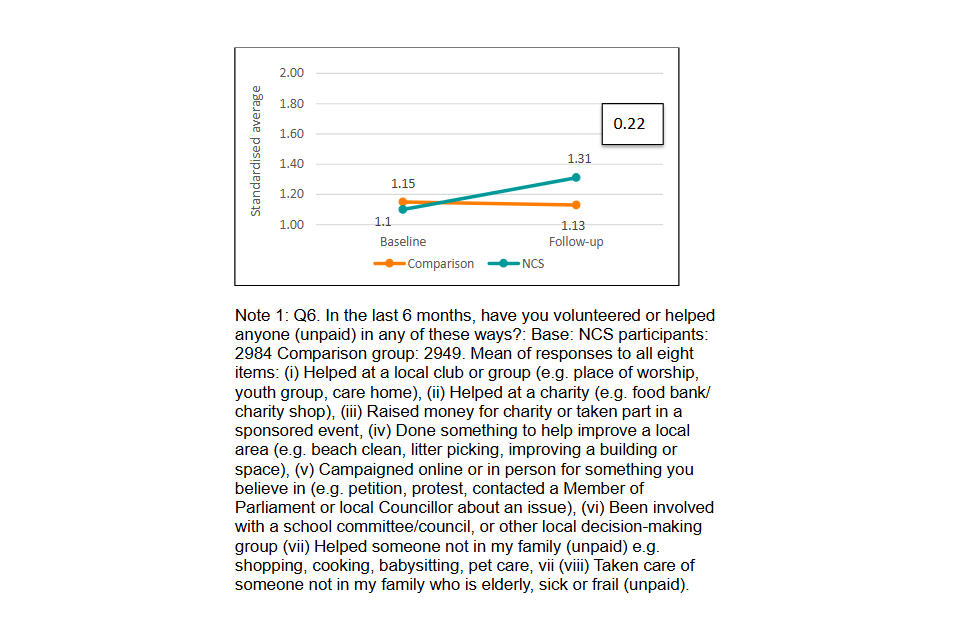

Overall, evidence suggests a greater variety of social action carried out by NCS participants, demonstrated by a statistically significant rise in the different types of volunteering undertaken, compared to the comparison group (see Figure 7). However, there was no statistically significant impact of the programme on the number of hours volunteered. Findings show no statistically significant evidence of an impact on the summary measure relating to civic engagement.

Volunteering

To measure participants’ engagement in volunteering and social action since NCS, participants were asked to list the types of volunteering they had done in the last six months and the number of hours they spent volunteering in the last four weeks. The types of volunteering listed were:

-

helped at a local club or group

-

helped at a charity

-

raised money for charity or taken part in a sponsored event

-

done something to help improve a local area

-

campaigned for something you believe in

-

been involved with a school committee/council, or other local decision-making group

-

helped someone not in my family (unpaid) e.g. shopping, cooking, babysitting, pet care

-

taken care of someone not in my family who is elderly, sick or frail (unpaid)

There is statistically significant evidence that NCS participants increased the different types of volunteering they engaged in relative to the comparison group, with an impact estimate of 0.22.

Figure 7: Change in the mean score on all types of volunteering carried out in the last 6 months[footnote 18]

Note 1: Q6. In the last 6 months, have you volunteered or helped anyone (unpaid) in any of these ways?: Base: NCS participants: 2984 Comparison group: 2949

Mean of responses to all eight items: (i) Helped at a local club or group (e.g. place of worship, youth group, care home), (ii) Helped at a charity (e.g. food bank/ charity shop), (iii) Raised money for charity or taken part in a sponsored event, (iv) Done something to help improve a local area (e.g. beach clean, litter picking, improving a building or space), (v) Campaigned online or in person for something you believe in (e.g. petition, protest, contacted a Member of Parliament or local Councillor about an issue), (vi) Been involved with a school committee/council, or other local decision-making group (vii) Helped someone not in my family (unpaid) e.g. shopping, cooking, babysitting, pet care, vii (viii) Taken care of someone not in my family who is elderly, sick or frail (unpaid).

| Title | Impact estimate | Comparison baseline | Comparison follow-up | Treatment baseline | Treatment follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Figure 7: Change in the mean score on all types of volunteering carried out in the last 6 months | 0.22 | 1.15 | 1.13 | 1.10 | 1.31 |

Social cohesion

A common thread through all NCS activities was creating opportunities for social mixing, which is critical in driving outcomes for disadvantaged young people and reducing stigma. The impact survey contained questions about social inclusion, social mixing, and a sense of belonging in local areas. These questions are intended to measure the impact of the programme on its intended outcome to allow ‘young people to develop a greater understanding and awareness of others from diverse backgrounds’. This in turn was intended to support the long-term impact that ‘young people feel a stronger sense of belonging - with greater tolerance and respect for a diversity of people and views.’

Overall, the results were mixed. While there was an observed decrease in the social inclusion summary measure among NCS participants relative to the comparison group, there was statistically significant evidence of an increase in the perceived importance of various forms of social mixing. There was no statistically significant effect of the programme on social belonging in the local area.

Social inclusion and sense of belonging

NCS participants and the comparison group were asked how well each of the following statements described them; whether they were “very much like me”, “mostly like me”, “somewhat like me”, “not much like me” or “not at all like me”.

-

“I treat all people with respect regardless of their background”

-

“I respect the views of others”

-

“I feel badly when somebody is treated unfairly”

-

“I find it difficult working with people who have different backgrounds to me”

-

“If I saw a young person getting picked on by others, I would stand up for them or try to get help.”

There was an observed decrease in the social inclusion summary measure among NCS participants relative to the comparison group, with an impact estimate of -0.16.

The survey also included questions about the participants local area (defined as the area within 15-20 minutes from their home) and asked whether they agreed or disagreed that they:

-

“could personally influence decisions affecting their local area”

-

“could trust people around here”

-

“feel that I belong to this local area”

-

“would be willing to work together with others on something to improve my neighbourhood”

-

“feel a sense of responsibility towards my local neighbourhood”

There was no statistically significant difference of the programme in relation to social belonging.

Social mixing and acceptance

To identify changes in NCS participants’ levels of social mixing and acceptance, the survey asked participants to rank from “1 to Not all important” to “5 to Very important” the importance they personally place on a series of actions related to the ways they interact with people, such as their friends, classmates, teachers and people they work with. These actions were:

-

spend time with people who are different to you (for example their ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, religion or family background)

-

learn about other people’s cultures

-

stand up for the rights of others

-

treat people with respect, regardless of their background

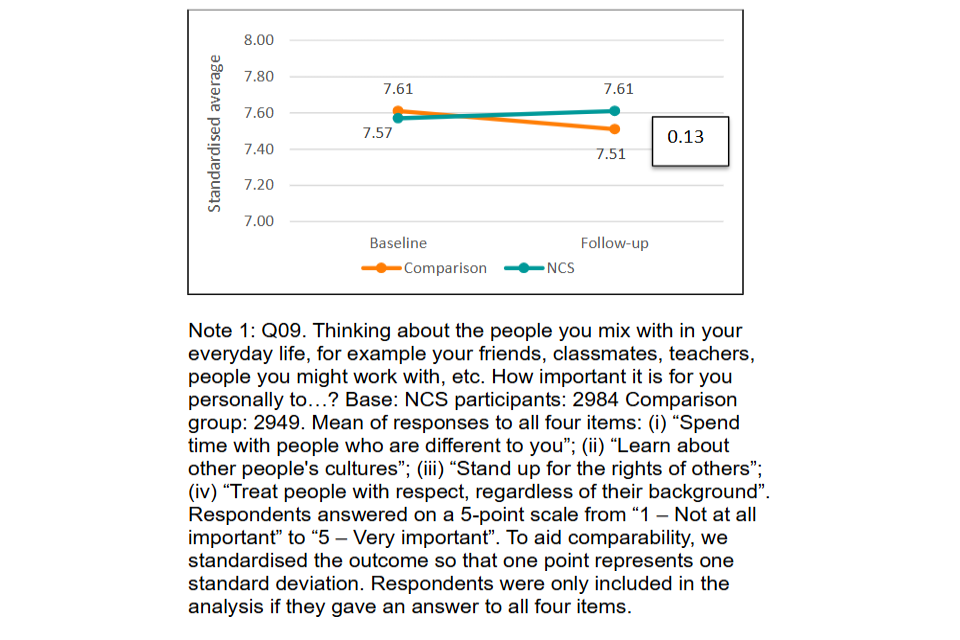

The findings for this summary outcome show a statistically significant increase among NCS participants compared to the comparison group (with an impact estimate of 0.13). This reflects the positive contribution of NCS in fostering social mixing among participants (see Figure 8).[footnote 19]

Figure 8: Change in mean score of importance for social mixing

Note 1: Q09. Thinking about the people you mix with in your everyday life, for example your friends, classmates, teachers, people you might work with, etc. How important it is for you personally to…? Base: NCS participants: 2984 Comparison group: 2949. Mean of responses to all four items: (i) “Spend time with people who are different to you”; (ii) “Learn about other people’s cultures”; (iii) “Stand up for the rights of others”; (iv) “Treat people with respect, regardless of their background”. Respondents answered on a 5-point scale from “1 – Not at all important” to “5 – Very important”. To aid comparability, we standardised the outcome so that one point represents one standard deviation. Respondents were only included in the analysis if they gave an answer to all four items.

| Title | Impact estimate | Comparison baseline | Comparison follow-up | Treatment baseline | Treatment follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Figure 8: Change in mean score of importance for social mixing | 0.13 | 7.61 | 7.51 | 7.57 | 7.61 |

Wellbeing

The final set of measures contained in the impact survey relate to how young people are feeling in themselves at the time of the survey. To measure wellbeing, the survey uses four questions developed by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) to provide a consistent measure of personal wellbeing ‘as individuals, as communities and as a nation’. Known as the ‘ONS-4’ these questions ask respondents to rank on a scale of 0 to 10 the extent to which they feel their life is worthwhile; how satisfied they are with life nowadays; how happy they felt yesterday; and how anxious they felt yesterday.

No statistically significant change was found for NCS participants, relative to the comparison group, for any of these wellbeing measures.

There are many factors affecting young people’s wellbeing, which makes it difficult to isolate an impact based on participation in a 2 to 4 night programme some months ago. For example, the survey was run during what would be an exam period for many young people. This might have had an impact on their wellbeing at that point. Similarly factors such as personal relationships, wider economic and social pressures, jobs and media can all influence participants’ responses to questions on their wellbeing. While the impact analysis is designed to address these factors to the extent to which they would affect the participant and comparison groups equally, if the effects of NCS are small it would be difficult to reliably detect these factors.

Reflections and recommendations

Programme design

The intent of the new NCS model as a diversified, year-round programme was welcomed by the sector. The design, which offered young people multiple routes in and ways to engage with support, was viewed as making the overall intervention more inclusive by design. This inclusiveness was true both for delivery partners (for example, it enabled smaller, community organisations to get involved) and young people (some of whom may not want or be able to take part in a residential experience, for example). Future programmes should similarly look to introduce flexible ways for young people to engage in ways that best meet their needs.

The programme has shown that young people are attracted to the opportunity to do something different, to occupy their free time and meet new people. Positive testimony of others (built over multiple years of NCS) was a key motivator in engaging young people with the residential service line. A future programme can build on these aspects to design experiences and market them to potential participants, and should make use of peer recommendation and word of mouth to create engagement.

The community open to all service was reported to have catalysed new partnerships and led to delivery model innovation; this is seen as a key legacy of NCS and a solid foundation to support delivery of more place-based funding. This was thanks, in part, to the regional grant funding model of the service lines, which awarded one grant per region and encouraged applicants to build consortia of local organisations to deliver experiences. Future programmes could utilise a similar grant funding model to catalyse regional partnerships and leverage local knowledge and assets to deliver high quality youth experiences.

Programme delivery

The potential of the new model was constrained by implementation challenges. Firstly, long delays to contracting meaning that, while experience targets were achieved in Year 1, delivery ran late. This created pressures for delivery staff (especially around recruitment) and financial implications for lead providers and their supply chains (including smaller providers). Future programmes must learn lessons from NCS implementation to ensure realistic timeframes are allowed for delivery to commence, particularly if they require local partnerships to be built.

Secondly, there was little to no referral between service lines by delivery partners and no MyNCS platform to act as a single front door for young people to navigate through the programme and engage in multiple ‘year-round’ experiences. This was seen by delivery partners as a missed opportunity to make NCS more than the sum of its parts and increase the impact on young people through multi-service participation. Building in suitable systems and permissions to enable data sharing between organisations (e.g. to more readily promote multi-service engagement from young people) should be considered and built in from the beginning.

The uncertainty around continuity of programme funding year-to-year presented some challenges for delivery organisations in terms of retaining staff, programme planning, being able to invest and innovate, and in building partnerships. Programme changes were also reported to hinder relationship building between delivery organisations, and between delivery organisations and schools (a key stakeholder in facilitating recruitment to the programme). Future programmes should consider funding sustainability and diverse sources of funding from the outset in order to ensure stability and security for staff, which in turn fosters more efficient and effective delivery.

Linked to this, the payment-by-results mechanism was seen as a source of financial risk for residential experience delivery partners, particularly given high attrition rates in Year 2, over which partners had limited control. In short, some organisations were having to cover costs out of their own pockets, which is not a sustainable model, especially if trying to encourage smaller organisations with less cash flow into the fold. Using alternative funding mechanisms may help future programmes achieve more impact and minimise risks to delivery.

Programme outcomes

The 2023 to 2025 NCS programme provided over 600,000 experiences for a diverse group of young people. Feedback from young participants was overwhelmingly positive with very high proportions finding it an enjoyable and worthwhile experience.

From the quantitative impact evaluation some key themes emerge. For life skills and independent living, there was a positive impact on confidence in leadership skills and problem solving, and a positive trend on one of the teamwork summary outcomes, which are arguably key skills in preparing young people for future life. It is perhaps surprising that there were not more positive outcomes observed, with several outcome measures showing no statistically significant evidence of impact.

For example, outcomes around employability and work readiness were inconclusive, which presents a challenge given the importance of not only providing young people with practical tools to access jobs, but also facilitating aspirations and positivity for the future. Qualitative findings suggested that ‘Boss It’ aspects were less popular in Year 1 compared to more exciting and interactive ‘Live It’ and ‘Change It’ programmes. Delivery partners had adapted their approach to integrate these elements into Boss It in Year 2, but this may not have been sufficient to show up in the impact findings. Future programmes will benefit from creating employability related activities that feel fun and appealing to young people and which add value beyond that already received in education, to maximise impact on both skills and aspirations.