Modern Slavery Fund review (2019 to 2021): findings, lessons and recommendations (accessible)

Published 20 May 2022

Overview

1. This report summarises trends and recommendation identified as part of a fund-wide review of the Modern Slavery Fund (MSF). The £33.5m MSF was publicly announced in July 2016 with the aim of reducing the prevalence of modern slavery internationally through a combination of core programming focused on UK priority countries and through a new Modern Slavery Innovation Fund (MSIF) aimed at trialling innovative ways of countering the problem. The MSF and MSIF are focussed on five mutually reinforcing outcomes that constitute the Fund’s pillars, namely:

Pillar 1: improved global coordination and disruption of trafficking routes and groups;

Pillar 2: more responsible business practices and slavery-free supply chains;

Pillar 3: reduced vulnerability to exploitation;

Pillar 4: improved victim support and recovery; and

Pillar 5: an improved evidence-base on what works best, how and where.

2. Detailed programme annual reviews and mid-term reviews have been produced over the subsequent phases of the programme. In turn, the objective of this fund-wide review is to identify overarching themes, lessons and recommendations that can be applied both with the context of future strategies and programming. Therefore, it does not provide individual programme scores, although these same programmes - alongside key achievements - are described in Annex 4. Instead, this report consists of the following sections:

- A strategic overview of the fund’s performance, including with respect to its geographic and thematic focus;

- Macro-level, ‘whole of fund’ findings, themes, and recommendations, drawn from the meta-analysis of the programmes. These are categorized under cross-cutting themes and the MSF pillars (see above).

3. To arrive at the above findings, this review employed a bespoke assessment framework testing performance against the Fund’s pillars as well as evaluating key questions relating to efficiency, relevance, and value for money (this framework is detailed in Annex 2). This review was conducted remotely due to the Covid-19 pandemic and does not, therefore, involve independent verification of results, such as through interviews with beneficiaries[footnote 1].

Performance ‘at a glance’

Overall, the fund delivered significant outputs over its two phases, whilst some early conclusions can be also drawn about its aggregated strategic impact. These are outlined below in the form of judgements, alongside corresponding levels of confidence. These conclusions have been drawn from the combined quantitative and qualitative analysis of the fund’s different projects.[footnote 2]

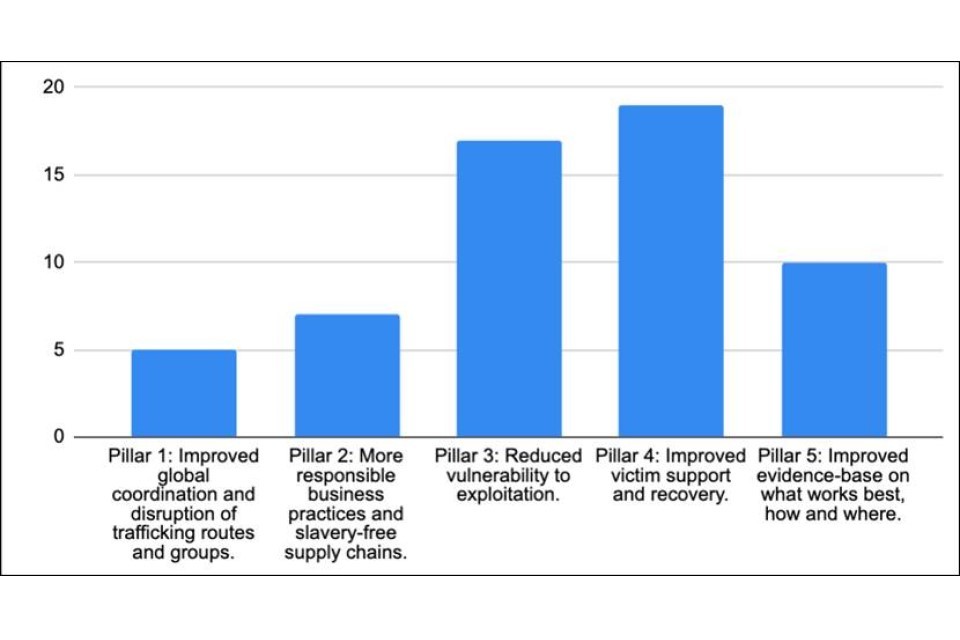

Judgement 1 (High Confidence): The fund demonstrated a relatively balanced spread across outcomes, with a particular emphasis on reducing vulnerability to exploitation (PREVENT) and improving victim support and recovery (PROTECT). The fund is therefore considered to have constituted a genuine attempt at addressing the drivers of modern slavery and human trafficking in priority countries, rather than just treating their symptoms. A more detailed illustration of the balance of focus between different outcomes is provided in Figure 1, below).

Figure 1 Distribution of programme outcomes across the fund pillars

Judgment 2 (Medium Confidence): The fund contributed to approximately 35 different policies. This included support to national-level, regional and local government strategies, action plans and implementation structures in at least 14 different countries (delivering against MSF Pillars 1, 3 and 4).

Judgement 3 (Medium Confidence): At least 8 UK companies/brands and many more overseas companies or supply chain groups committed to implementing outputs delivered within the context of the MSF.[footnote 3] A further 145-200 local companies were provided with training and guidelines in upstream contexts (Pillar 2).

Judgement 4 (Medium Confidence): Messaging via strategic communications campaigns conducted within the context of the programme may have reached at least one and a half million people around the world.[footnote 4] Additional targeted preventive communication activity (such as those focussed on specific communities) reached at least 50,000 PVoTs[footnote 5] (Pillar 3).

Judgement 5 (Medium Confidence): The fund is assessed to have directly contributed to supporting and/or reintegrating approximately 2500 potential victims or victims of trafficking across the different programmes, protecting them from further harm (Pillar 4).

Judgement 6 (Medium Confidence): The fund involved the training of close to 4000 service providers across the different outcomes, ranging from social workers to government officials and law enforcement personnel (Pillars 3 and 4).

Judgement 7 (High Confidence): The fund delivered over 30 evidence products, helping to advance collective understanding of the problem, and informing responses. These ranged from localised surveys and reports drawn from around 20 different countries to more generic best practice guidance (Pillar 5).

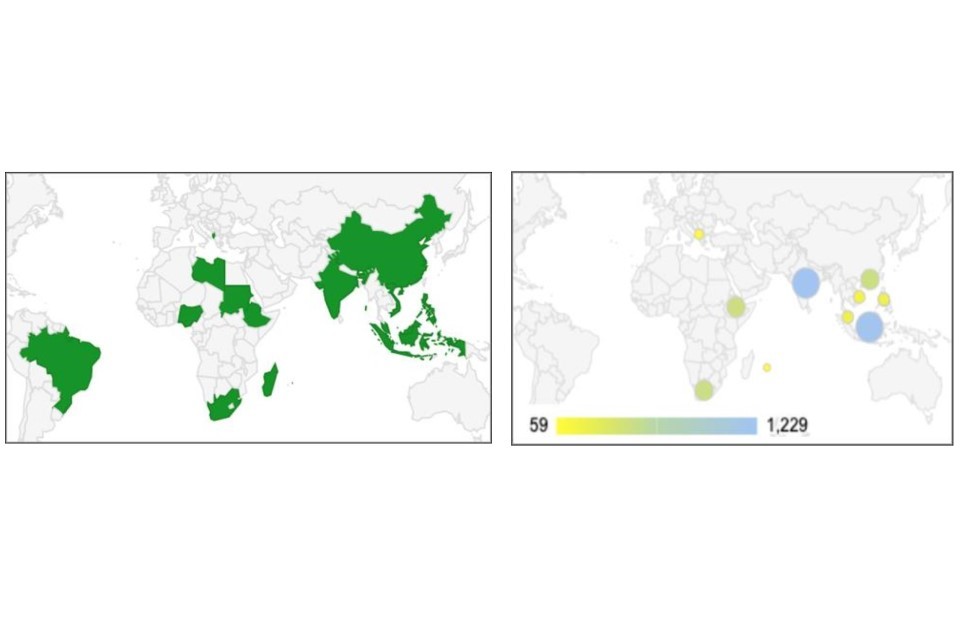

Judgement 8 (High Confidence): The fund focussed on the highest-risk source and transit countries with respect to human trafficking to the UK based on pre-programming analysis and referral numbers (see Figure 2, below).

MSF and MSIF programmes: Brazil, Nigeria, Libya, Sudan, Ethiopia, South Africa, Madagascar, India, China, Vietnam, Malaysia, Indonesia, Philippines. Service providers: India, Indonesia, South Africa, Ethiopia, China, Vietnam, Philippines, Malaysia.

Findings, Lessons and Recommendations: Detail

This fund-wide review produced the following findings, themes, and lessons, which are organised under the fund’s different pillars as well as three general introductory sections covering the topics of relevance, efficiency, sustainability, and coherence/coordination (i.e., the key evaluation criteria of this evaluation). These findings focus on the effectiveness of the results obtained, whilst highlighting accompanying recommendations.

The political context

1. Overall, the fund demonstrated a strong understanding of – and engagement with – different political contexts, with approaches well-tailored to their political, economic and social environments.

2. The fund also highlighted the extent to which strategic impact in any given context is often highly dependent on political will, regardless of the level of investment. It follows that securing the consent and buy-in from the relevant government ministries/executives is a pre-requirement for ensuring access to both the relevant stakeholders and performance results (such as with respect to capacity-building outputs). All MSF programmes have done this successfully and should continue to do so.

3. Engagement on MSHT can sometimes be a controversial area for international cooperation in terms of governments recognising the prevalence / occurrence of MSHT within their countries. Alternative language was therefore used across different projects (e.g., human trafficking, bonded labour/servitude, vulnerable working migration), reflecting different sensitivities around the use of MSHT terminology. Terminology was adapted to what local partners saw as contextually necessary to diminish risks – a pragmatic approach that should be continued.[footnote 6]

4. The fund provides a strong example of adaptive programming in the face of political and social change. Delivered in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic and other shocks such as revolutions, conflict, and natural disasters, it demonstrated flexibility both with respect to effective remote delivery and in adapting deliverables to the evolving context.

Recommendations for strategy and programming:

-

Continue to secure the consent of relevant partners from the outset using the appropriate terminology (e.g., Human Trafficking) and (if required and where appropriate) engage in diplomatic lobbying alongside programming activity, unlocking blockages as and when these arise. When working in politically sensitive areas, this may mean choosing long-standing partners with existing entry points at the local level (an approach generally adhered to by the MSF).

-

Include qualitative and politically focussed indicators within the results framework to better measure politically focussed outcomes/results, including with respect to political access and level of influence over strategies, policies, and government attitudes.

Case Study: IOM victim support framework (China)

In China, IoM chose a non-contentious area of work, aimed at giving the country sufficient practical experience to pilot a national referral mechanism with the aim of subsequently expanding work to other activities. It produced pilot Standard Operating Procedures (SoPs) for the identification, referral and support of trafficked persons and vulnerable migrants to be used by the Civil Affairs Bureau (CAB) and Public Security Bureau Officers (PSB) in Jiangxi Province. The pilot SoPs were consolidated with feedback from local authorities and helped to codify pre-existing counter-trafficking roles and the responsibilities of different actors while harmonising local regulations with international best practices. Upon delivery, these were approved by the central and provincial authorities to be distributed to participants attending the project workshops, and CSOs, police and shelter staff received practical and theoretical training. Pre and post-surveys of the training revealed a significant increase in knowledge, particularly regarding VOT identification, interviewing techniques and needs assessment.

Case Study: Global Partners Governance (GPG) – Tackling Modern Slavery in Sudan

GPG’s programme, which was run under the MSIF, was aimed at developing locally led solutions for combatting human trafficking in Sudan using a peer-to-peer capability-building approach, working directly with the (Transitional) Government of Sudan. The programme adapted to significant political volatility by using the momentum of Sudan’s revolution to influence the policy debate on human trafficking. Policy action, which focussed on providing support to the country’s Ministry of Justice, appears to be connected to the passing of amendments to the 2014 anti-trafficking law that criminalised sex and labour trafficking. This in turn has nudged the legislation further towards compliance with the Palermo Protocol on Human Trafficking and other international conventions, whilst Sudan has also progressed from the US State Department’s Tier 2 Watchlist to Tier 2 (demonstrating a gradual improvement). The programme also seems to have contributed to the education of politicians, resulting in increased public messaging and commitments as well as improved coordination structures connecting central and sub-national institutions.

The breadth versus depth debate

5. The majority of the programmes sought to spread their activities - and therefore risk - across multiple MSF pillars, the latter of which roughly correspond to the MSHT vulnerability chain. Moreover, 56% of programmes contained outcomes that corresponded to three or more outcomes. This is arguably in line with the MSF’s ‘whole of system’ logic but may also have resulted in a reduction in overall concentration of effort on specific vulnerabilities or entry-points in different contexts, such as those corresponding to specific UK comparative advantage.[footnote 7]

Recommendations for strategy and programming:

-

Ensure that programmes are situated within an understanding of the wider system, including other sectors that may require unlocking in order to maximise overall programmatic impact.

-

Allow for concentration of effort on specific areas corresponding to UK comparative advantage within any given context (including those that might complement the activities of other actors and donors).

The sustainability challenge

6. The fund has delivered significant capacity-building, ‘train and equip’ and security sector reform outputs across the different programmes (see Pillar 1). In some contexts, these led to the establishment of entirely new national and local level structures, committees, and law enforcement units, some of which are likely to outlive programming activity.

7. At the same time, longer-term sustainability remains the single greatest challenge for the fund - ensuring that short-term gains, particularly the outputs of capacity-building assistance, survive. Medium, and longer-term funding challenges to capacity-building projects are also already apparent across many of the programmes[footnote 8] even though genuine attempts have been made by HMG Teams and partners to reduce these risks. [footnote 9]

8. The fund also highlighted the importance of being able to work pragmatically with the political and social grain, rather than seeking to create new units or entities from scratch - the latter of which are more likely to lead to entanglement, complicating exit strategies.

Recommendations for strategy and programming:

-

Develop better mechanisms to measure the efficacy of capacity building efforts beyond relatively binary output indicators such as the number of individuals trained, workshops conducted, or convictions secured. Some mechanisms have already been suggested within the annual reviews and are being used in other HMG funds such as the CSSF and FCDO Governance programmes (outcome mapping, political access, and Insight Analysis), and some are being implemented[footnote 10].

-

Experience from other HMG programme managers could be used to deliver capacity building to partners and HMG MSF Programme and political officers.

-

Consider committing to specific high-potential projects for the longer term to gauge project impact (following careful initial design and needs analysis). Examples include: (a) regional programmes involving transnational work with the same implementer particularly across South Asia, North and West Africa, (b) support to wider partnerships with the private sector spanning across multiple locations and supply chains.

-

Plan for post-delivery evaluations with partners (after 1 to 2 years after the end of the projects) and not only end line evaluations. This assessment in part responds to this recommendation for some of the projects which ended in 2020, but the same approach is suggested for projects ending in 2021 or 2022. This could include agreeing with partners to share results after one or two-year of completion of the programme and incorporating it as part of grant agreements[footnote 11], or implementing a third-party post-delivery evaluation.

Case Study: India

Three projects were implemented in India with varying budgets and scopes, all offering strong value for money (VfM), demonstrating that it is not only larger programmes that offer strong cost-efficiencies and sustainability. The three projects had very different scopes/aims and worked in different geographic locations across India, yet built strong VfM through a common approach and by ensuring: (a) a strong focus on building capacity and leadership at the grassroot level; (b) ensuring consistency and building from (and not against) local regulations; (c) cooperating with local authorities; (d) a focus on sustainability by advocating for stronger local policies and public funding, creating efficiencies amongst local organisations, creating capacity and leadership within the community of survivors; and (e) ensuring replicability by creating models that could be taken into other states, with low added costs.

Some of the outcomes achieved through these projects included: (a) police, child protection committees and child welfare committees in 5 states using better information more effectively for policy and investigative purposes; (b) 30 frontline organisations across India using an integrated online service model for collection of VoTs’ data; (c) bonded labourers were included as a vulnerable group by India at the second Voluntary National Review (VNR) on Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in the UN-High- Level Political Forum in 2020 and considered in the COVID-19 support packages provided by the national government; and (d) three trafficking survivors in Telangana won local-body elections and their advocacy led to Bonded Labour Vigilance Committees being established in most of their districts. Other results are included in Annex 3 and 4.

Cross-programme coordination and reporting

9. Real attempts were made at developing cross-fund cohesion, including by way of sharing products and via online presentations/training sessions. However, coordination was complicated by both Covid-19 (including travel restrictions) and by the lack of a streamlined mechanism for sharing and comparing both lessons and performance outputs.

10. This meant that performance and quarterly reporting tended to be submitted via relatively opaque as well as lengthy MS Word documents, whilst also reducing the ease with which partners could access existing evidence products (such as on what constitutes ‘effective’ training for service suppliers and/or P/VoTs. This significantly impacted complementarity across the fund, possibly also impacting value for money.

11. Project management and coordination processes also deliberately differed quite significantly from one programme to another based on size/scale/scope of programme and ease of doing business in certain places as different programmes require different levels of management[footnote 12]. Coordination tended to increase when programme/project accountability rested with the same person(s) or at least the same unit. In some cases, the lack of coordination meant that even projects implemented within the same country (e.g., India and Indonesia, more detail in Annex 4) did not know what each other was doing, increasing the likelihood of duplication, and restricting possibilities for joint work and better cost-efficiencies.

12. In what is perhaps a wider issue, HMG staff tended to lack formal programme management training prior to taking on oversight roles, whilst changes/rotations in and/or fast hand-over of HMG staff complicated the task of maintain corporate memory. The Fund is now managed by a specific International Serious and Organised Crime programme management hub, however.

Recommendations for strategy and programming:

-

Develop a central web portal or knowledge repository (e.g., via DevTracker that can be accessed by all the different implementers and programme managers. This should include easy access to evidence products and lessons, case studies, points of contact as well as guidance on best practice, and benchmarks (such as with respect to costs). Performance data (including quarterly reviews) could also be entered via this platform, allowing for the easier aggregation and visualisation of data, and reducing bureaucracy (e.g., by providing a simplified reporting template).

-

Consider programme and financial management training for staff overseeing the delivery of large programmes as well as providing opportunities for different coordinators to exchange and discuss experiences and challenges, as done with the MSIF all-partner meeting (and as planned for the whole portfolio before Covid-19 made this difficult).

Assessment against Programmatic Pillars

Pillar 1: improved global coordination and disruption of trafficking routes and groups

13. The fund reveals clear examples of helping to bolster coordination at the national and sub-national level both across government structures and between different societal sectors (such as civil society, non-government, and communities). Some examples include programming in Vietnam, India, the Philippines, Albania, and Nigeria which are provided in wider detail in Annex 4. However, these did not overall extend to international and regional structures (such as by improving multinational mechanisms), even if national-level capacity building can arguably contribute to more integrated international responses.

14. Similarly, there were relatively few examples of where PURSUE capacity-building programmes in different countries were directly connected to each other or to wider HMG activities in those same countries (e.g., Nigeria and Albania),[footnote 13] such as by enabling the collection of intelligence in source countries to enable operations further downstream in transit countries. This partly stemmed from safeguarding and (victim) data protection requirements that precluded the sharing of some types of sensitive information/intelligence.

15. Experience gained across the fund highlights the importance of conducting a baseline analysis of the capacity and capabilities of beneficiaries (such as, for example, law enforcement counterparts) before investing in training and mentoring activity. Such projects can rapidly become expensive and require the acquisition of equipment, capabilities, and infrastructure.

16. Depending on the context, there may be a high level of distrust in the authorities and/or concern about denouncing human trafficking groups (such as for fear of reprisal). Understanding such risks can help to inform programming, including by way of adding safeguards such as witness protection. Most relevant projects offered specific mechanisms to address this risk, including online data-secured platforms to ensure the protection of the information and the survivors (examples include in India, Malaysia, Mauritius and Albania – see Annexes 3 and 4).

Recommendations for strategy and programming:

-

Consider how national level structures might link to international or multilateral mechanisms as well as to the other programmes in the wider region.

-

Conducting a baseline or needs analysis of specific potential future beneficiaries can help to avert unforeseen risks, costs, and requirements. This was done in some projects (Vietnam, Albania, India, China) but could be expanded as a minimum requirement. The pre-programming/design phase should include a data collection agreement with beneficiaries to ensure that performance information (such as relating to the use of equipment and/or training) can be obtained.[footnote 14]

-

Where appropriate, consider ways of linking different security sector reform programmes (e.g., criminal justice capacity-building) across regions and/or source and transit routes so that these add up to more than the sum of their parts.

Case Study: Vietnam

IoM’s Tackling Modern Slavery programme harnessed internal and external organisational networks and an evidence base built within the country to reconstruct victims/survivor routes of migration. Information collected from survivors was shared and disseminated with local UK authorities, charities, and law enforcement, who distributed information among their professional and social networks, including to frontline units in the southeast of England and near the border of France. IOM Vietnam and UK also facilitated a series of webinars with country offices along migration routes to discuss challenges, gaps, and opportunities to cooperate in assisting Vietnamese migrants and victims of trafficking in transit countries. As part of this effort, country-specific victim support information was translated into Vietnamese to support victims and materials were distributed among Government and NGO networks working in transit hubs. More information on other results for this project in Annex 4.

Pillar 2: more responsible business practices and slavery-free supply chains

17. Programmes within the fund revealed the importance of ensuring the direct participation of all of those involved in the labour recruitment chain, rather than only the employees. These include employers, recruitment agents, trade unions and relevant membership associations (particularly those issuing required certification), shipping and logistics providers (including warehouses and storage facilities) and online retailers.

18. Some projects, moreover, highlighted the value of adding awareness-raising components to onboarding and professional development training in vulnerable workplaces such as factories (e.g., ASI project in Mauritius, Freedom Fund and IJM project in India). Some of these were developed as online tools that could continue to be delivered after the end of the projects. Given the possible lack of trust in authorities (see Pillar 1), some projects also realised the value of communicating messages through local (migrant) community leaders.

19. The leverage-efficiency dilemma: Implementation partners who already benefited from a wider set of donors - particularly private sector businesses - were able to operate at greater scale and appeared to have a greater likelihood of ensuring sustainability. At the same time however, some of these same organisations also required greater overheads and demonstrated less efficiency than smaller, albeit less well connected, partners.

Recommendations for strategy and programming:

-

Continue to include multiple communities of stakeholders when conducting risk awareness activities within the business sector, including those responsible for issuing certifications and accreditations.

-

Include delivery partners who already have experience with, or are directly part of, private sector-supported initiatives. Joining efforts from already established programmes can contribute to larger outcomes.

-

Consider creating incentives for private organisations - particularly those that are in supply chains to the UK - to support responsible practices.

-

Consider the following indicators as measures of progress for more responsible business practices, when funding future programmes with this aim: (a) number and type of public commitments to policies and principles to tackle human trafficking and modern slavery; (b) number of (or amount of financial contributions) directed to increase the number or quality of safeguarding mechanisms for migrant workers; and (c) existence of verification mechanisms to ensure adequate conditions for migrant workers within all supply chain. Attendance at training workshops does not constitute a sufficient indicator.

-

Consider capturing examples of where adoption of tools, evidence or training has led to changes in public and business policy and practice, drawing out case studies of good and bad results/practices (a number of which are detailed in Annex 3).

Case Study: Working across the supply chain in South Africa

Stronger Together developed strategic partnerships (guidance, training, and cross-sector ‘safe space’ dialogues) with South Africa’s agribusiness sector to reduce the risk of forced labour across the supply chain. This involved working with employees, employers, trade unions, membership organisations (those providing certification to businesses), civil society, NGOs, and key influencers in the private sector as a means of increasing knowledge of relevant legislations and employer responsibilities. Through this approach, the programme contributed to safeguarding fruit and wine supply chains, including to the UK. Involvement from the certifying membership organisations acted as an incentive for businesses to participate in the dialogue, a lesson that could likely be applied in other contexts.

Pillar 3: reduced vulnerability to exploitation

20. Overall, at least one third of the programmes in the fund included specific vulnerability-reduction projects or deliverables[footnote 15]. However, many of the wider deliverables contained within the other pillars also arguably contributed to this outcome indirectly (strengthening business practices, for example, supports the end state of reducing vulnerability within the private sector). In this respect, Pillar 3 may be closer to a whole of fund aim, rather than an outcome.

21. Most Pillar 3 projects consisted of different variations of either strategic communications or targeted risk-awareness campaigns, representing a significant proportion of overall spend. This is despite a relatively low evidence base on the overall effect of large-scale strategic communications campaigns and the challenges in measuring results beyond outputs and basic interaction indicators.

22. Training courses, modules and workshops also made up a high proportion of projects. These ranged from pre-departure training for migrants to e-courses aimed at increasing knowledge of online risks. Whilst some of these effectively amounted to a variation on the theme of messaging campaigns, others offered a more localised (and often in-person) mechanism through which to engage with vulnerable communities. In some of the projects implementing these mechanisms, specific examples of behaviour change were captured and revealed greater efficiencies by engaging communities and local authorities (see testimonies below). Yet in many others, there was poor understanding of what had been achieved.

23. Credibility in some cases proved to be a challenge. Here, UK involvement in risk-awareness campaigns was perceived to be aimed at dissuading migrants from departing source countries.

Recommendations for strategy and programming:

-

Carefully consider the likely impact of messaging campaigns in different contexts and how changes in behaviour or attitudes will be monitored. Continue to build on existing post-campaign evaluation methodologies (e.g., Nigeria and Albania), such as through audience surveys.[footnote 16]

-

MSF and MSIF projects, including in Albania and Nigeria, offer examples of how to conduct a systems-wide analysis of key vulnerabilities in order to avoid falling into the trap of generic risk messaging.

-

Consider producing meta-analysis of the communications products and surveys across the fund to distil guidance for future efforts (this would also provide a good example of additionality and contributions to future efforts), accepting that campaigns will always need to be tailored to the local context.

Case Study: Nigeria - Not for Sale campaign

The Not for Sale communications campaign, which was coordinated by the Government Communication Service International in partnership with the Nigerian National Agency for the Prohibition of Trafficking in Persons (NAPTIP), consisted of a multi-channel communications campaign aimed at promoting alternative livelihoods to young women vulnerable to human trafficking for sexual exploitation.

The campaign launched on 29 March 2019 and ran for six weeks across TV, radio, social media, outreach events, billboards and bus adverts targeted to Edo and Delta states. The campaign resulted in 631,000 social media views, 30,000 engagements (likes, shares, comments), 47,438 microsite page views, 8 national print articles, 15 online news and blog placements, and primetime TV coverage.

Case Study: Testimonies from Vietnam

A PVOT in Nghe An, father of one the 39 VOTs who died in Essex also said: “After the training, I learned a lot from the workshop, which helped me be more confident to work out my livelihood plan. I joined the workshop hoping for an investment loan to re-open the carpenter’s shop that I used to run. With all the knowledge gained from the workshop, I realized that there were many other alternatives that suit my condition better. Without delay, I want to start making hygiene liquid, then using the liquid to see if it can deodorize; I also want to make compost and livestock feed to reduce the input investment cost. I will also work with my communal leaders to deodorize the trash bins. I am willing to learn more to fulfil my aspiration to run an exhilarating business that does not require great physical strength but still helps generate stable income.”

Pillar 4: improved victim support and recovery

24. Assistance provided by the eleven projects working on this area spanned across the spectrum of screening, improved protection policies and structures, shelter and counselling/legal support to survivors, and reintegration to local communities. Detailed examples of the spread of activity and what was achieved is provided in Annex 3.

25. There is strong evidence that the project is giving a voice to survivors and potential victims, either by reflecting their views directly in research products, or through direct engagement with local organisations and support providers. In a few instances, victim representatives have also been included in public policy discussions.

26. The fund demonstrated several examples of where projects were able to leverage existing government policies such as social security schemes, sustained livelihoods, or counselling programmes. In these cases, the main factor of success was the previous experience of local partners, which in many cases had already developed relationships with local governments.

27. The task of assessing the value for money of victim support and recovery programmes is significantly complicated by the lack of baseline cost guidance (such as per-assisted-individuals) to benchmark the spending of different projects, the difficulty in quantifying risks and benefits and the high costs of victim support in the UK. Furthermore, divergences in the way budgets are presented or even cross-cutting contributions from different budget lines (or from local authorities) to a single objective means that it is difficult to pin-point exactly what proportion of the budget is directly aimed at supporting victims.

28. Additional frequently cited issues included a lack of follow-up on reintegration cases, data loss, the absence of unambiguous definitions relating to potential victims within local legislation, the lack of local government resources, and a lack of clarity on the specific status of victims. Some of the projects specifically worked on creating innovative solutions to some of these issues (e.g., Freedom Fund working on data loss across grassroot organisations; IJM and Partnering Hope into Action (PHIA) increasing follow up and resources from local authorities). Better inter-project coordination could ensure that learning is shared and creative solutions implemented in all contexts.

Recommendations for strategy and programming:

-

Develop a list of VfM benchmarking indicators on per capita victims- assistance, based on those being used in the UK, to inform victim support and recovery value for money assessments.[footnote 17]

-

Consider including intended audiences into programme design (particularly in the development of mobile Apps and standard operating procedures. When Apps are used, these should provide information of legal rights, what to expect at work and include a reporting mechanism. Where relevant, information should also be available in multiple languages and via audio (e.g., where literacy rates are low). These measures seem to have been implemented in all MSIF projects so far.

-

Include home follow-up visits within projects. These offer a means to ensure that survivors are looked after and have access to the relevant resources (livelihood, education, and health). These can be conducted by local government, municipal bodies, CSOs and/or local grassroot organisations (particularly in areas where distrust to local authorities is higher). Follow-up sessions (such as training on specific themes) should also be considered.[footnote 18]

Spotlight: The impact of Covid-19 on victim recovery

Mid Term Reviews and wider programme reporting stress that the COVID-19 pandemic has worsened the situation of victims of trafficking, bonded labour, forced servants and vulnerable migrants. Continued uncertainty placed workers at higher risk of exploitation, particularly those in desperate need of employment and therefore willing to work in the informal sector and/or accept unfair working conditions.

Some good adaptations and responses to the pandemic included:

-

In the context of the ASI project, the Government of Mauritius was convinced to install a redeployment desk to support migrant workers who had lost their job due to COVID-19 and needed urgent work elsewhere in the country.

-

The Freedom Fund project in India was adapted to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic by providing hands-on support to participant NGOs with ad-hoc analysis of community-level data to call for more aid and to help direct government aid distributions to the most affected communities. A ‘Voice of the communities’ tool was also built and used by 21 participant NGOs to gather info from affected communities to inform government response to the pandemic. As a result, 42 government schemes were identified, and at the time of writing over 1,800 applications to these schemes were being tracked in the Pathways system.

-

Guidelines on Gender Responsive and Non-stigmatising Approaches for Shelter and Quarantine Place Officers developed by the IOM ASPIRE project are supporting community and district government in operating shelters and quarantine spaces for returnee migrants who need to quarantine before returning to their own community (in Indonesia).

-

In response to COVID-19-related additional risks for vulnerable migrants, the ETI project in Malaysia enabled the local partner to increase their support in assisting migrant workers with the resolution of labour cases. Local partners also distributed emergency food supplies to migrant workers, who were ineligible for most government emergency support.

-

The IJM project in India provided substantive inputs to guidelines on bonded labour during the COVID-19 pandemic, which were accepted and informed government guidelines and schemes, thus increasing the reach of the support provided. Survivors were also supported in accessing the new schemes.

Testimonial – Child Victims of Trafficking Receive Psychological Support Services – A Human Story (UNICEF Albania).

Psychological support is a basic need for the beneficiaries of the services provided by the Vatra Centre to victims of trafficking and their children. Support is provided to child witnesses of trafficking in order to develop their personality in a healthy way.

Ana is seven years of age and began school in Grade 1 this year. Her life has been far from easy. Her mother was not always present in the first years of her life, and she has never known her father. Two months ago, Ana started taking part in therapy sessions with the shelter’s psychologist as her behaviour had become concerning. At the same time, the psychologist worked with Ana’s mother to empower her to make better decisions in her life, to provide appropriate parenting and to live a more stable life.

Ana’s emotional state has significantly improved for the moment, and she has started building positive relationships with family and her new classmates. “My dearest friend is Megi. We both look after each other if we are being bullied by other children. Megi is a very close friend,” said Ana.

The psychologist is continuing to work to enhance the girl’s self-image and assist the complete elimination of self-harming thoughts that have arisen as a result of her feelings of abandonment.

Pillar 5: Improved evidence base on what works best, how and where

29. The fund produced a large variety of research outputs, with some of these opening the possibility to support future programmes. Some specific recommendations on this area were already provided in the cross-programme coordination section.

30. Research and evidence products covered a wide ground - from local perceptions assessment to macro-level guides that could be applied within different contexts. However, attempts at developing new Artificial Intelligence and innovative visualization solutions were impeded by a lack of source data (the latter of which is also required for effective monitoring). This included a dearth of national/local available statistics and data with respect to both referrals and criminal justice outcomes. This meant that more advanced, multi-data analytics and visualisations (such as layered heat maps) were difficult to develop. Similarly, few attempts were made at developing an overall data and evidence-driven baseline and benchmarking criteria that could be used to inform progress and performance monitoring in different contexts (other than the indicators provided in individual log frames).

Case Study: United Nations University (UNU)

Named after Target 8.7 of the UN Sustainable Development Goals, UNU’s ‘Delta 8.7’ programme consisted of developing a global knowledge platform bringing together different resources relevant to countering forced labour, modern slavery, human trafficking, and child labour. This led to the creation of web portal containing a range of resources, including 193 country dashboards with information ranging from child labour statistics to government policies as well as three strategic-level policy guides focussed on justice, crisis response and markets.

Additional Implications for Future Strategy

Taken together, the findings, insights, lessons, and recommendations of this review point to various implications for strategy making.

-

Despite achieving some impressive results at the output level which have changed lives for thousands of people in just a few years, a £33.5m fund cannot realistically be expected to deliver transformational impact across four ambitious pillars in almost fifteen countries, most of which are fragile. This means that unless longer-term funding can be committed to, a real trade-off is required for any future strategy or fund – namely to invest more significantly in a much smaller number of countries (depth) or to narrow the aperture to specific vulnerabilities or opportunities that play to UK comparative advantage or clear gaps in a wider number of contexts (breadth).

-

Additionally, opaque terms such as ‘eradicate’, ‘combat’, ‘tackle’ or ‘address’ should be avoided, as these are difficult to measure and can be interpreted broadly. Whilst the 4P framework offers a ready-made strategy template, achieving real-world impact will likely require a more focussed definition of the desired end-state and, as a result, clearer trade-offs. The tailored approach taken by each of the MSF projects and programmes so far broadly supports this, but results frameworks can and should continue to be refined.

-

The effective delivery of campaigns requires clear leadership from the centre (which has been provided by the Home Office) and Senior Responsible Officers with accountability for specific deliverables and/or partnerships across missions and sectors. Whilst much of this is already in place - and simply advocating for increased coordination is never helpful - effective ‘operationalisation’ (i.e., day to day delivery) may nevertheless require a clearer means through which to better connect different strands of activities.

-

A much simpler and common reporting process (i.e., one that does not include complex log frames and quarterly performance reporting) would help considerably with the above (accepting that the current format may be one imposed by commercial teams). This would not mean reducing accountability but increasing it - preventing opportunities to ‘hide’ behind lengthy and nebulous reports and instead focussing more clearly on actual results, challenges, and delivery. This could also feed into an easily accessible central dashboard and SMART objective-focussed template if this allowed for local nuance/complexity.

Annex 1. Framework of analysis

To what extent has the fund resulted in improved global coordination and disruption of trafficking routes and groups? (Pursue)

Outcome Indicators

-

Number of OCGs dismantled as a result of fund assistance.

-

Ability of OCGs to operate as a result of assistance.

-

Quantifiable increase in regional/international cooperation (e.g., investigations, intelligence exchange etc.)

Output-level Indicators

-

New legislation passed.

-

Successful operations/interdictions/ prosecutions.

To what extent has the fund resulted in more responsible business practices and slavery-free supply chains? (Prevent/Protect)

Outcome Indicators

-

New legislation and/or regulatory provisions passed.

-

Responsible recruitment policies, systems and data gathering

-

Global/country-level framework agreements between businesses and trade unions, or business and suppliers on workers’ rights.

Output-level Indicators

-

Signatures and/or participatory agreements.

-

Products (e.g., guidance and best practice).

-

Sessions/modules delivered to the private sector.

To what extent has the fund resulted in reduced vulnerability to exploitation? (Prevent/Protect)

Outcome Indicators

- Perceptions of risk within vulnerable communities.

Output-level Indicators

-

Awareness raising products and/ or campaigns (e.g., strategic communications).

-

Number and/or reach of target audience.

-

Education modules on risks/mitigations.

-

CSOs supported.

To what extent has the fund resulted in improved victim support and recovery? (Protect)

Outcome Indicators

-

Number of victims removed from harm.

-

Number of victims rehabilitated/reintegrated.

Output-level Indicators

-

Establishment of new structures (e.g., referral mechanisms, resource centers).

-

Number of referrals through NRM or similar mechanism.

-

Number and scope of projects aimed at rehabilitating victims.

To what extent has the fund resulted in improved evidence-base on what works best, how and where? (Evidence base)

Outcome Indicators

- Extent to which evidence base and lesson sharing has been reflected in programming.

Output-level Indicators

-

Evidence and learning products delivered.

-

Dissemination, recipients and reach of products.

Impact

-

Did the outputs lead to outcomes or impact achievements?

-

What are the key achievements in this area?

Effectiveness

-

Did the interventions achieve its intended outputs?

-

How were these delivered? What were the key enablers and challenges?

Efficiency

- Was delivery achieved in a VFM manner (including cost-efficiency and effectiveness and sustainability?

Relevance/ Coherence

-

Were country projects/programmes relevant for the specific contexts?

-

Were they coherent/ complementary and strategic between themselves?

-

Have voices from potential victims, victims and survivors being part of the interventions?

Cross-cutting

-

Did the programmes have an agreed approach to conflict and gender sensitivity?

-

Gender sensitive analysis on the drivers and consequences of migration and trafficking

-

How did this analysis inform programming?

-

Were recommendations from previous assessments applied/taken into consideration?

-

What new lessons and learning was produced (if any)?

Annex 2. Findings against ICAI recommendations

More interventions in neglected areas of modern slavery[footnote 19] and mainstreaming in other development projects

-

The fund contributed to approximately 35 different policies. This included support to national-level, regional and local government strategies, action plans and implementation structures in (at least) 14 different countries.

-

New areas of work were incorporated within the Fund including work to address bonded labour and domestic servitude in India, Malaysia and Indonesia, Child Sexual Abuse and Exploitation (CSAE) in the Philippines and working with centrally placed politicians in Sudan.

-

Some of the projects specifically invested in understanding migration paths and offering integrated assistance and support across the whole routes (e.g., IOM Vietnam, Stronger Together in Ethiopia).

-

Projects involved ‘hyper local’ activities in hotspots and problem localities (e.g., Nigeria, Albania, Ethiopia, South Africa, India).

Draw on survivor voices, in ethical ways[footnote 20]

-

At least one third of the programmes in the fund included specific vulnerability-reduction projects or deliverables with a number of these also involving survivor stories.

-

There is strong evidence that the project is giving a voice to survivors and potential victims, either by reflecting their views directly in research products, or through direct engagement with local organisations and support providers. In a few instances, victim representatives have also been included in public policy discussions.

-

95% of the research products focused on deepening the understanding of survivor stories, better documenting the key factors or risk, vulnerability and obstacles in resettlement or reintegration, or building data collection mechanisms that would avoid their revictimization.

-

Some of the projects brought forward innovative mechanisms to strengthen survivor voices, including providing leadership training and accompanying them in the route of becoming elected officials and/or advocating directly for better protection/assistance.

-

In all projects we found evidence of HMG ensuring gender and conflict-sensitive programming, particularly for those programmes directly engaging with survivors.

More systematic approach to filling knowledge and evidence gaps

-

The fund delivered over 30 evidence products, helping to advance collective understanding of the problem, and informing responses. These ranged from localised surveys and reports drawn from around 20 different countries to more generic best practice guidance.

-

Research and evidence products cover wide ground - from local perceptions assessment to macro-level guides that could be applied within different contexts. Attempts at developing new Artificial Intelligence and innovative visualization solutions were impeded by a lack of source data (the latter of which is also required for effective monitoring).

-

Genuine attempts were made at developing cross-fund cohesion, including by way of sharing products and online training sessions even though this was complicated by both Covid-19 (including travel restrictions) and the lack of a single mechanism or platform for sharing and comparing lessons and performance outputs.

-

Research products could have been more effectively shared across the portfolio, such as through a central knowledge repository, platform or website allowing for easy cataloguing and searching.

Clear statement of overall objectives and approach

-

The fund’s five pillars reflected the need to address the drivers of modern slavery and human trafficking in priority countries, rather than just treating the symptoms.

-

The fund focussed on the highest-risk source and transit countries with respect to human trafficking to the UK, drawing on evidence from the Home Office joint specialist analysis centre team and referral numbers

Partnerships on modern slavery, including engagement with private sector and partner governments to develop locally owned actions[footnote 21]

-

The fund has delivered significant capacity-building, ‘train and equip’ and security sector reform outputs across the different programmes (see Pillar 1). In some contexts, these led to the establishment of entirely new national and local level structures, committees, and law enforcement units.

-

The Fund specifically contributed to the delivery of at least 25 local/national policy-level outputs including national action plans, widening the scope and support provided by migrant/resettlement desks or the inclusion of international best practices within legislation.

-

The fund demonstrated several examples where projects were able to leverage existing government policies such as social security schemes, sustained livelihoods, or counselling programmes. In these cases, the main factor of success was the previous experience of local partners which in many cases had already developed relations with local governments.

-

One of the five MSF Pillars specifically focused on creating more responsible business practice and slavery-free supply chains. 20% of the outcome-level indicators specifically focused on this area.

-

Programmes within the fund revealed the importance of ensuring the direct participation of all of those involved in the labour recruitment chain, rather than only the employees. Private-sector partnerships were built with at least three private sector confederations/ supply chains.

Annex 3. Outcome selected highlights against MSF pillars

Pillar 1: Improved global coordination and disruption of trafficking routes and groups.

Pillar 2: More responsible business practices and slavery-free supply chains.

Pillar 3: Reduced vulnerability to exploitation.

Pillar 4: Improved victim support and recovery.

Pillar 5: Improved evidence-base on what works best, how and where.

Nigeria/MSF

Pillar 1

Nigerian National Agency for the Prohibition of Trafficking in Persons (NAPTIP) increased ability to conduct active investigations, secure at least 8 convictions as well as rescue in excess 200 victims, 110 and of whom were referred to IoM (and therefore presumably Outcome 1 funded activity).

Pillar 3

Awareness-raising includes the flagship ‘Not for Sale’ campaign, which resulted in 631,000 social media views, 30,000 engagements (likes, shares, comments), 47,438 microsite page views, 8 national print articles, 15 online news and blog placements and primetime TV coverage. Pre and post tracking surveys with 1680 girls.

Pillar 4

Support to at least 300 victims of trafficking, with assistance spanning across the spectrum of screening through to rehabilitation.

Albania/MSF

Pillar 1

Institutional capabilities of law enforcement, judiciary and social welfare sector strengthened. Training curricula has been provided for the Security Police Academy and the School of Magistrates; 26 judges and prosecutors trained; 62 graduating students of Security Academy trained.

Pillar 3

Programme has worked with 5,000 vulnerable people and first responders. Training provided for 300 judges, prosecutors, victims’ advocates, police officers, social services and child protection units. Direct technical support to the Ministry of Interior and to the Office of the National Anti-trafficking Coordinator for the preparation of the new NAP on human trafficking 2021 – 2023.

Pillar 4

Essential reintegration services to over 330 potential/victims of trafficking and their dependents.

Pillar 5

Initial study on youth knowledge and attitudes, which involved interviews with over 1,500 Albanian youth in Diber, Kukes, Shkoder and Tirana.

GPG-Sudan/MSIF

Pillar 1

Policy action contributes to the passing of amendments to the 2014 anti-trafficking law with Sudan progressing from the US State Department’s Tier 2 Watchlist to Tier 2. Mentoring results in improved coordination structures connecting central and sub-national institutions.

Pillar 3

Education and training to politicians resulted in public messaging and commitments.

UNU-Delta 8.7/MSIF

Pillar 4/5

Three policy guides focussed on justice, crisis response and markets. Symposia on addressing child labour in a pandemic, gender and measurements of MSHT, and use of AI in achieving Target 8.7. Web portal containing a range of resources, including 193 country dashboards with information ranging from child labour statistics to government policies. Three country-level workshops to identify best practices and policy or implementation gaps in local contexts.

Retrack/HfJ-Ethiopia/MSIF

Pillar 1

Training to government officials from the Ministry of Women, Children and Youth, Addis Ababa Police Commission, Agency for Civil Society Organisations and Addis Ababa Bureau of Women and Children.

Pillar 2

Community conversations’ established dialogue between employers of domestic labour, domestic workers and recruiting agents(brokers) and resulted in the public signing of codes of conduct (signed by 135 participants).

Pillar 3

Local level self-help groups created as a means of messaging and bolstering community resilience. Close to 500 women have been helped with financial literacy (saving and establishing small businesses). Moreover, 1000 children appeared to have gained a greater understanding of risks because of wider messaging activity (based on programme reporting).

Pillar 4

Lydia Lighthouse project, a shelter and recovery centre located in Addis Ababa capable of taking on victims (usually referred by the police) and offering psycho-social, medical and rehabilitative care, supports rescue and reintegration of 421 girls.

Stronger Together-SA/MSIF

Pillar 1

Multi-sector, ‘safe space’ dialogue established through partnerships and stakeholder steering groups, which included representatives form trade unions, civil society, NGOs and the government.

Pillar 2

Strategic partnership with membership organisations as well as training and awareness-raising events. The programme also worked with key influencers within the private sector as a means of increasing knowledge of relevant legislations and employer responsibilities.

Pillar 5

Capturing of lessons on ways of strengthening supply chains.

Mauritius-Madagascar/Anti Slavery International (ASI)

Pillar 2

One company fully committed to the application of the app and MRC (ASOS). Extension to supply chain pending.

Pillar 3

Redeployment desk to support migrant workers who had lost their job due to COVID-19 and needed urgent work elsewhere in the country established, revision of national legislation on migrant workers. Pre-departure trainings (PDOT) piloted with 444 PVoTs.

Pillar 4

444 VoTs assisted by a Migrant Resource Centre. Remedy mechanisms to address complaints also include online app.

Pillar 5

Research in Bangladesh and Mauritius finishing outlining the impact of COVID-19 on migrant workers, and access to remedy for migrant workers in the global supply chain.

India/Freedom Fund

Pillar 3

Police, Child Protection Committees and Child Welfare Committees in 5 states using information for policy and investigative purposes.

Pillar 4

30 frontline organisations in India using integrated online service model for collection on VoTs data.

Indonesia-Ethiopia/IoM ASPIRE

Pillar 3

Recommendations from the research were considered in the Ethiopian. National Partnership Coalition’s five years (2012-2025) strategic plan, expanding formal migration channels for returnees, increasing support for job creation for them and adding gender sensitivity.

Pillar 5

Two research reports in Indonesia and Ethiopia investigating the role of social groups in resettlement, and the risk factors for victim of trafficking, especially in providing reintegration support for victim and returnees.

Malaysia/ETI

Pillar 2/3/4

Access to Remedy principles for migrant workers in global supply chains in Malaysia finalised (https://migrantworkerremedy.org). Six UK brands and supply chain groups already supporting (TFG London, KAREX, The Very Group, ARCO, Fifty-Eight, Our Journey).

JustGoodWork app Malaysia finalised and launched. Provides information on legal rights, pre-departure information and reporting mechanism in local languages of migrants. Channels grievances through a local NGO, who will support the worker in resolving the issue and by working with the employer.

Pillar 5

Formative research on Human Rights Due Diligence in Malaysia’s Manufacturing Sector.

China/IoM

Pillar 4

New Pilot Standard Operating Procedures for the Identification referral and support of Trafficked Persons and Vulnerable Migrants approved in Jiangxi Province, China which codify roles and responsibilities of different actors while harmonising local regulations with international best practices. Pilot might be extended to other provinces.

Pillar 5

The new National Action Plan on human trafficking included many of the suggestion provided within the research that supported the SoPs.

India/International Justice Mission (IJM)

Pillar 2

Guidelines and findings shared with 133 national and global delegates representing sectors of textile and apparels, labels and stickers, IT, food, service, paper, malt extracts, exports, agriculture, packaging, jewellers, instrumentation, logistics and warehouse, as well as think tanks and senior management institutions.

Pillar 3

Inclusion and acknowledgment of Bonded Labourers as a vulnerable group by India at the second Voluntary National Review (VNR) on Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in the UN-High- Level Political Forum in 2020.

Pillar 4

Five survivors in Telangana stood for local-body elections (not seen before) and three won (all women). One of them is now Deputy Sarpanch (village-level local self-governance leader). Stronger advocacy led to Bonded Labour Vigilance Committees been established in most of their districts.

Pillar 5

Assisted state governments to analyse the local triggers of bonded labour in two areas in Telagana.

Research study on socio-economic factors contributing to forced labour, specific to the state of Rajasthan.

India/Partnering Hope into Action (PHIA)

Pillar 4

59 village governments (Gram Sabhas) in Jharkhand initiated record keeping with respect to child trafficking and 35-watch committee and 59 village child protection committees formed and operating. Public policies now prioritising victims as beneficiaries of social welfare schemes during planning process.

Pillar 5

Implementers data on local migration supported the consolidation of policies that facilitate informed and supported migration between Jharkhand and other states. Information was used by the Department of Labour, Employment and Training in Jharkhand, and the Border Roads Organisation, and supported COVID-19 returning working migrants.

Vietnam/IoM

Pillar 1

Through cooperation with ECPAT, the project developed strategic information about modern slavery and support services for Vietnamese migrants in the UK and across the route of migration (in Europe).

Pillar 3

Developed an anti-trafficking prevention behaviour change communication (BCC) campaign which is being integrated within key local organisations (the Women’s Union (WU) and Community Advocacy Groups (CAG) and is using the increased evidence-base from other project activities to keep improving the messaging and methods of delivery though community outreach and popular social media platforms.

Pillar 4

Assisted the Department of Social Vice and Prevention (DSVP) to review and revise policy governing the eligibility and provisions of victim support services in Viet Nam, increasing its coverage and provision of victim support.

Helped to develop policies, guidance, training, and an integrated systems for National TiP and Child Protection Hotline to (111) to better collect and manage data of victim support/ counselling.

Pillar 5

Vulnerability Report and Knowledge, Attitude and Practice (KAP) assessment developed and presented. Information used, alongside technical and financial backing to the Ministry of Public Security (MPS) to review the existing National Plan of Action to Combat Trafficking and develop its next five-year plan and 2030 vision (including Vietnam-UK trafficking networks as a priority).

The Philippines/ StairwayFund

Pillar 3

Institutionalized Local Child Protection Plans to prevent Child Sexual Abuse and Exploitation (CSAE) in the cities of Caloocan, Malabon and Navotas (CAMANA) supported and finalised.

Pillar 5

Baseline Study on the Landscape of Child Sexual Abuse and Exploitation in the three municipalities of CAMANA. Information expected to be used for the development of Local Plan of Action to End Violence Against Children (LPAEVAC).

Indonesia/Institute for Criminal Justice Reform (ICJR)

Pillar 3/4

Creation of a of a new systematized data system of modern slavery cases in. four cities of Indonesia (Jakarta, Kupang, Makassar and Surabaya).

Three cities developed policy briefs to allow increase in the number shelters, the revision of the local regulation on modern slavery to include data collection as a key priority and data gathering and investigation of potential modern slavery cases involving children.

Pillar 5

Getting to Good Human Trafficking Data: A Workbook and Field Guide for Indonesian Civil Society published and shared with XX local CSOs.

Annex 4. Project Level assessments

Tackling Modern Slavery Programme – Nigeria (MSF)

Programme overview

The Tackling Modern Slavery (TMS) programme is aimed at addressing the underlying drivers of modern slavery in and on routes from Nigeria, with a focus on four outcomes (each constituting the programme’s pillars of activity:

-

Strengthened return and reintegration support provided to victims of trafficking, through tailored support to (potential) victims delivered primarily by the International Organisation for Migration (IoM).

-

Enhanced (Nigerian) State capacity to investigate trafficking suspects, through HMG direct capacity-building support to law enforcement (specifically, the National Agency for the prohibition of Trafficking in Persons, NAPTIP, in Benin City)

-

Increased judicial capacity to adjudicate and apply legislation to cases involving trafficking suspects, through HMG training of judges and provision of equipment to courts.

-

Enhanced public awareness regarding the risks and realities of human trafficking and alternative home opportunities, via strategic communications as well as mass media, including the “Not for Sale” campaign (HMG- led implementation).

Assessment of overall impact/effectiveness

The stated overall impact of the programme is where activity results in an improved enabling environment for the deterrence of human trafficking in and from Nigeria. Overall, it is assessed that the programme has taken concrete steps towards this end, particularly by bolstering Nigerian investigative capabilities, although the challenge will be to sustain progress over the longer term. The extent to which victim support can be directly situated against the stated deterrence aim is debatable, although this may have contributed to making the business of recruiting victims more difficult (thus achieving deterrence by denial).[footnote 22] It also (arguably) provides a necessary accompaniment to the mentoring of law enforcement investigations teams, by ensuring that rescued victims are given necessary protection and support (and in this respect also supports the stated aim).

MSF Pillar 1: contributions improved global coordination and disruption of trafficking routes and groups.

Despite experiencing Covid-related delays, NAPTIP staff appeared to increase their safeguarding knowledge because of training and, critically, were able to conduct active investigations, secure at least 8 convictions as well as rescue in excess 200 victims, 110 and of whom were referred to IoM (and therefore presumably Outcome 1 funded activity). Previous reviews concluded that this activity was both the highest scoring on outputs and outcome and the most consistently evaluated and monitored.[footnote 23] Key to the efficacy of this strand was the provision of equipment, including vehicles, to NAPTIP.[footnote 24] At the same time however, contributions to increased judicial capacity to adjudicate and apply legislation to cases involving trafficking suspects through the training of judges and the provision of court equipment to courts appeared the hardest to measure as a result of a dearth of monitoring and evaluation data.

MSF Pillar 3: contributions to reduced vulnerability to exploitation.

Primary outputs relevant to this pillar consisted of communications products aimed at potential victims and those in their circles of influence (e.g., family members) and disseminated across multiple channels (via GCSI implementation), including the flagship ‘Not for Sale’ campaign.[footnote 25] These were aimed clearly at enhancing public awareness of the realities of human trafficking and of alternative home opportunities (i.e., in line with Outcome 2 of the programme). NAPTIP capacity to deliver its own messaging campaigns was also enhanced. Annual reviews and stakeholder interviews suggest the pillar reached a large audience, although it is unclear to what extent this translated into strategic impact or behaviour change.

MSF Pillar 4: contributions to improved victim support and recovery.

Overall, the programme’s work aimed at delivering outcome 1 appears broadly on track (following the granting of a no-cost extension) to support at least 300 victims of trafficking, with assistance spanning across the spectrum of screening through to rehabilitation. It has also exceeded its targets in terms of providing training to counsellors, shelter, and health workers. However, the FY 2020/21 Annual Review does point to delays (including Covid-related) in implementation and a lack of reporting against the results framework,[footnote 26] although the former problem seems to have been mitigated by an extension to the programme. It would be helpful for the IoM to produce a specific breakdown of beneficiaries is provided by IoM (see also gender sensitivity section).

Cross-cutting evaluation questions

Efficiency: did the project/programme achieve VFM (including cost efficiency and sustainability)?

Annual and mid-term reviews have consistently raised concerns about VFM, including the lack of concrete reporting/measures, complicating the task of providing an overall assessment. On balance however, the provision of training to NAPTIP, support to victims, and strategic communications do seem to have delivered against the aims of the programme, although:

-

Victim support (Outcome 1) has come at a high cost of almost £3.5m, representing a high recovery and reintegration cost per person (particularly when compared to individual average annual salaries).

-

Sustaining the very real gains made via support to NAPTIP (Outcome 2) are almost entirely predicated around the availability of future funding by either the Federal Government of Nigeria or external donors.

-

In the absence of reporting, it must be assumed the Outcome 3 did not represent VFM, although this remained a small part of the overall programme at just under £180k.

-

At almost £1.4m the strategic communications products (Outcome 4) were relatively expensive given the lack of clarity on their overall impact amongst target audiences, although these did at least reach high numbers (particularly the Not for Sale campaign).

Relevance/Coherence: Was the programme relevant and coherent? - Describe the extent to which projects were (a) relevant to specific contexts; (b) complementary and strategic between themselves.

Overall, the programme demonstrated direct relevance to the MSF’s overall theory of change and intended outcomes. The projects were selected based on their potential to disrupt trafficking organisations, protect victims, and communicate risks to a large audience. There are also clear examples of complementarity, perhaps most notably the extent to which victims identified by NAPTIP investigations were subsequently referred to the IoM for protection, support, and reintegration. Consideration was also given to ensuring that the provision of training was appropriate to both the context and the needs of the beneficiaries which, in the case of NAPTIP, reflected the low starting baseline for programming and the need to invest in very basic equipment as part of the project.

There are also concrete examples of where the voices of (potential) victims and local communities are reflected within the programme. Illustratively, design of the Not for Sale messaging campaign involved interviews with just under 1,700 young women and their family members as well as detailed focus groups in Edo and Delta states.[footnote 27] The same research campaign also yielded some useful findings on the ways in which women and girls obtained their information and on some of their motivations for leaving their home state (with the potential to also contribute to Fund’s overall aim of enhancing the evidence base around modern slavery).

Some of the (the lower cost) activities did appear to fall short with respect to complementarity. For example, questions remain on the extent to which training provided to the judiciary bolstered – or in fact was in any way linked to – support to NAPTIP. This includes whether NAPTIP investigations were prosecuted by the judges and courts to which support had been provided (this criminal justice pathway appeared to be part of the logic underpinning the programme’s design). With respect to relevance, open questions also remain as to the exact profile of all of victims, as return flights from Libya may have been used to carry non-victims and reportedly even traffickers on rare occasions (partly because IoM deliberately seeks to avoid discrimination in its approach to screening).

Conflict and Gender Sensitivity: Describe the extent to which the programme reflected conflict and gender sensitivity and gender/conflict sensitive analysis

Previous reviews have highlighted gender sensitivity (GS) gaps within the programme, including the lack of an initial GS analysis to inform subsequent delivery (and specifically the need for a more thorough understanding of roles and positions in society as these related to gender). The (revised) results framework does however contain indicators disaggregated by gender, although these did not – once again according to previous reviews – provide sufficient clarity on the overall aim of the programme with respect to gender. Concerns were also previously raised on the extent to which gender dimensions could impact NAPTIP investigations – an area requiring further analysis. This Fund-level review has nevertheless picked up on a number of real attempts at reflecting gender within project delivery, both with respect to victim protection (reflected inter alia in the higher number of women beneficiaries and shelters) and communications (which included gender-based analysis within the design phase).

UNICEF - Transforming National Response To Human Trafficking In And From Albania (MSF)

Programme overview

The Transforming [the] National Response to Human Trafficking (HT) in and from Albania programme is aimed at an overall reduction of human trafficking in and from Albania, with a focus on four outcomes:

-

Outcome 1: Innovative and strategic communications that bring positive change in [the attitudes of] individuals, families, and communities with respect to human trafficking, thus reducing vulnerability to HT.

-

Outcome 2: Victim-oriented justice and effective law enforcement and prosecution through the strengthening of investigations, prosecutions, and the penal code.

-

Outcome 3: Sustainable and rights-based models for reintegration of the victims and the at-risk population – where the victims and potential victims of trafficking are identified in a timely manner, their immediate needs addressed, and their reintegration facilitated.

-

Outcome 4: Preventative resilience building through community-driven solutions for those at high risk of trafficking through education, vocational training, and alternative employment support.

The programme has been implemented in Tirana and the three northern regions of Shkoder, Diber and Kukes, via a UNICEF-led consortium of implementers.

Assessment of overall impact/effectiveness:

Despite relatively broad outcome statements (which also vary slightly across the programme documentation),[footnote 28] the programme has delivered a large number of outputs across a wide spectrum of activities, ranging from the production of national action plans all the way through to working with local actors. These appear to have at the very least contributed to the higher-level outcome of establishing stronger cross-societal cooperation and dialogue on human trafficking as the basis for collective action, including by way of a receptive government counterpart in the form of the Office of National Anti-Trafficking Coordinator (ONAC).

MSF Pillar 1: contributions improved global coordination and disruption of trafficking routes and groups.

Under Outcome 2, the programme produced outputs ranging from virtual simulation-based training exercises for the judiciary through to manuals for the School of Magistrates (adapted as a distance learning manual for the SoM’s intranet) and Security Academy (adapted as a distance learning course). It also delivered a revised National Action Plan for Albania on combatting human trafficking, providing an overall strategic framework for countering the problem. This latter product arguably contributed towards encouraging a ‘whole of system’ approach within Albania as well as more clearly linking central and local structures. The programme may yet also contribute to the passing of a new law on anti-trafficking which, in turn, would outline roles and responsibilities for overall delivery in Albania.

MSF Pillar 3: contributions to reduced vulnerability to exploitation.

The programme contributed to reducing vulnerability to exploitation through awareness-raising activities ranging from community engagement to social media messaging. These also appear to have been conducted across multiple outcomes/pillars. Illustratively, facilitators working on community-level awareness reached close to 1,300 individuals, whilst Facebook content generated more than 891,000 impressions (where content is displayed on feeds). Electronic newsletters were also produced, with the programme’s 4th iteration (published in February 2021) reaching 600 stakeholders, partners, and influencers across different organisations (Government, NGO’s, the media, and international organisations). As ever, gauging the specific impact of these messaging campaigns is a challenge (not least as this requires proving a negative), although their reach at least appears to have been significant.