Levelling up for families: Annual report of the Supporting Families programme 2021-2022

Published 31 March 2022

Applies to England

Presented to Parliament pursuant to Section (3) 6 of the Welfare Reform and Work Act 2016

© Crown copyright, 2022

Copyright in the typographical arrangement rests with the Crown.

You may re-use this information (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. To view this licence visit http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3/

If you have any enquiries regarding this document/publication, email correspondence@levellingup.gov.uk or write to us at:

Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities

Fry Building

2 Marsham Street

London

SW1P 4DF

Telephone: 030 3444 0000

Ministerial foreword – Kemi Badenoch MP

In 1954, Winston Churchill, reflecting on what he cherished most in life, remarked that around the family and the home, all the greatest virtues are created, strengthened and maintained. It is a sentiment that is as true today as it was then.

Our determination to reinforce the bonds that hold our families and our communities together is at the heart of our plans to level up the country - giving people the support they need to get on, to live healthier and happier lives, and to realise their true potential.

By helping individuals to access the right mental health support, to leave abusive relationships and to find stable jobs, the Supporting Families programme is not only making levelling up a reality, it is giving people reasons to be hopeful for a better future.

Prevention is a centrepiece of the programme with every family assigned a dedicated keyworker who brings local services together to diffuse issues at an early stage before they get out of control.

And it is paying off. All the evidence shows that this approach is changing people’s lives for the better.

Since 2015, over 470,000 vulnerable families have received direct support to build a brighter future but the positive ripple effect of that has been huge with over a million families having benefitted from the programme’s ‘whole family’ approach.

There is also evidence which shows that this programme reduces the number of children who need to be taken into care. Indeed, the Independent Review of Children’s Social Care, in its recently published “Case for Change” has stressed the importance of providing meaningful support early on to struggling families. It also highlighted Supporting Families as one of the programmes which is delivering real results. I am looking forward to reading the full findings of their report.

Our ambition now is to take these achievements and really build on them, channelling support into what we know is working and finding new ways to support people through turbulent periods in their lives.

That is why, at last year’s Budget, the government announced an additional £200 million for Supporting Families - a 40% real-terms increase in funding by 2024-25.

This takes total planned investment over the next three years to £695m – testament to the importance the Government places on this programme in levelling up the life-chances of families across England.

This enhanced funding will enable local services to provide more meaningful, practical help to families, for example, parenting support and giving more families proper budgeting advice. Together, this will help alleviate some of the obvious stresses and strains families face so that they can concentrate on the things that really matter.

In addition, this report sets out a number of improvements we are making to the programme this year. We are updating our expectations on what a successful outcome is across a range of problems a family might face. We are fulfilling our manifesto pledge to put Supporting Families on the path to continued success, but we are also strengthening the ties that bind our families and our society together so that our country emerges from the COVID-19 pandemic stronger, fairer and more united than ever before.

Kemi Badenoch, Minister for Equalities and Levelling Up Communities

Kemi Badenoch MP

Minister for Equalities and Levelling Up Communities

Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities

Executive summary

Supporting Families received an additional £200m investment at the 2021 Budget and Spending Round which takes total planned investment to £695 million by 2024-25. This new funding will enable the programme to continue until March 2025 and help secure better outcomes for up to 300,000 families over the three-year period.

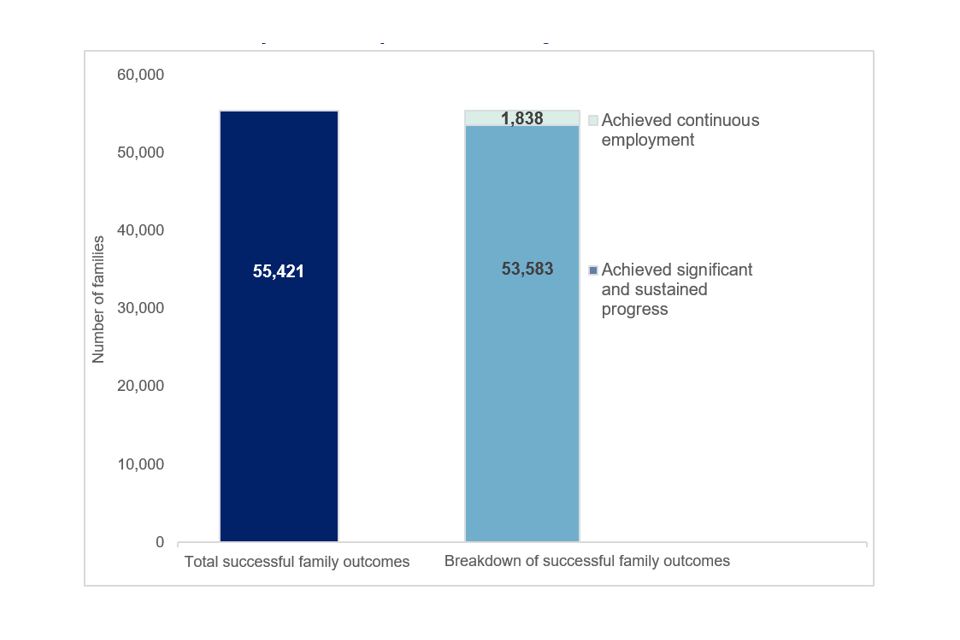

The current phase of the programme has been operational since April 2021, and as of January 2022 has achieved a total of 55,421 successful family outcomes. This builds on the 414,955 successful family outcomes achieved by the Troubled Families Programme between April 2015 and March 2021.

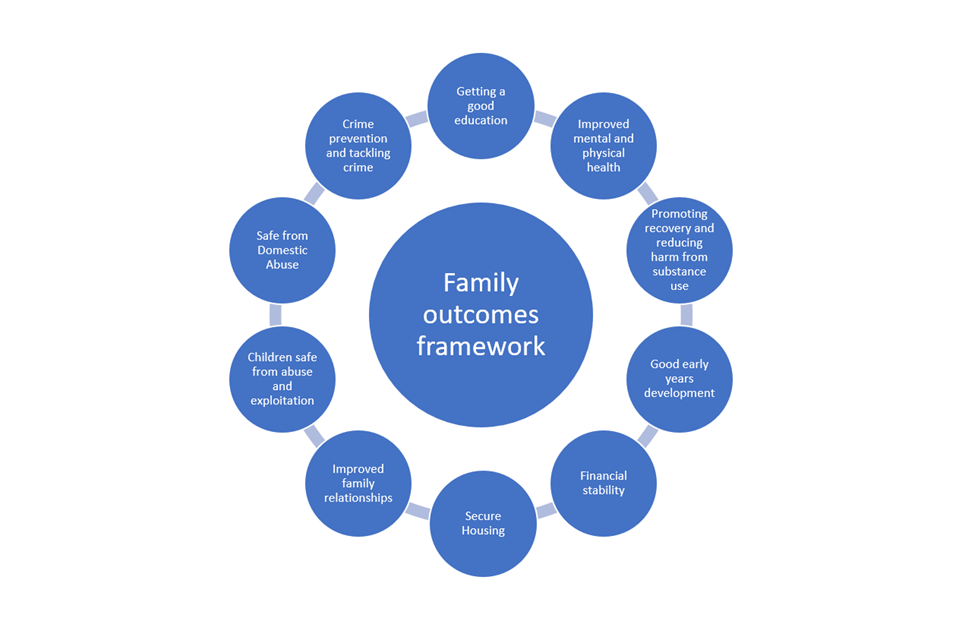

A new outcomes framework has been developed in consultation with local authorities. The new framework includes ten headline outcomes rather than the previous six.

The funding formula for the programme has been updated and is now using the latest deprivation data and more recent population data. The formula now includes the 2019 Index of Multiple Deprivation which provides a better reflection of current need and supports levelling up by ensuring funding is distributed fairly.

A new process for local authorities to apply for Earned Autonomy status has been launched. A prospectus sets out the level of maturity local authorities and their partners will need to demonstrate to move to Earned Autonomy status.

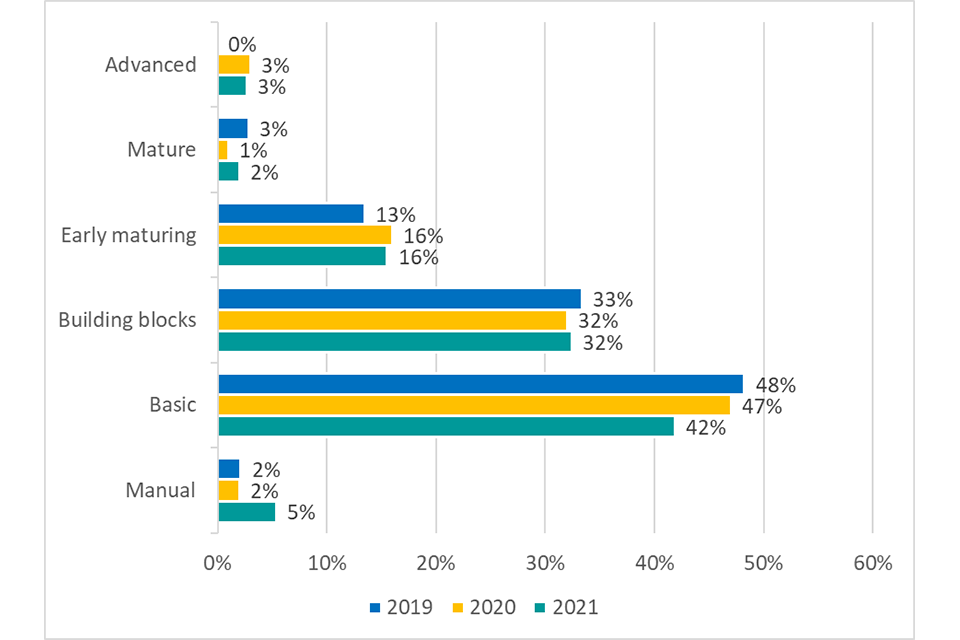

Five local authorities were selected for a funded Housing and Whole Family working pilot. The local authorities have been developing models of good practice with the aim of improving relationships between housing services and early help and family support services. A data maturity survey shows that 21% of local authorities are operating early mature to advanced data models. The most advanced local authorities have offered excellent examples of how data is being used to support families.

A £7.9m Local Data Accelerator Fund for children and families is funding ten data sharing and data linking projects. The projects are being funded through to March 2023 and are aiming to advance use of data to better support vulnerable children and families.

A refreshed Early Help System Guide has been published following collaboration with local authorities and other government departments. The refreshed version improves on the content and clarity of the self-assessments and works to encourage local transformation in line with the descriptors.

Alongside this report we are publishing qualitative research looking at effective practice and service delivery. Supporting Families is delivered differently in each local authority and this report explores the most effective way to deliver the programme.

Supporting Families overview

This is the sixth annual report for the programme and sets out the key achievements and policy developments over the last year. This report fulfils the duty to report on disadvantaged families in the Welfare Reform and Work Act 2016.

The programme

Supporting Families launched in March 2021 and builds on the previous Troubled Families Programme. The programme received £165m for 2021-22. As set out in the policy narrative ‘Supporting Families 2012 to 2022 and beyond’, this phase of the programme has focussed on building the resilience of vulnerable families to help them thrive, and on enabling system change locally and nationally. This means making sure that every local authority has joined up, efficient local services and are able to identify families in need and provide the right support at the right time. Supporting Families is committed to driving strong multi-agency local partnerships in every local authority, and mature local and national data systems which means investing more in good practice, overcoming barriers to data-sharing, and involving the voice of families in service design and commissioning.

Supporting Families provides targeted interventions for families with complex interconnected problems including unemployment, poor school attendance, mental and physical health problems, involvement in crime and antisocial behaviour, domestic abuse and children in need of help and protection. Services are managed by upper tier local authorities in England working together with a range of partner organisations. The four key principles of Supporting Families are outlined below:

-

Early intervention – The programme funds early help services outside of the statutory system (such as children’s social care or the criminal justice system). It encourages services to intervene to address problems before they reach crisis point.

-

Whole family working – A keyworker works with all members of the family to understand the family’s interconnected problems. They build relationships with the whole family and coordinate services to help the family resolve them.

-

Multi-agency working - Supporting Families is designed to bring agencies together to provide joined up support for vulnerable families.

-

Measuring outcomes and data - The programme requires local authorities to establish an outcomes framework across multiple services and encourages them to track and report family outcomes.

New funding for 2022-2025

An additional £200m for Supporting Families was announced at the 2021 Budget and Spending Round. This represents around a 40% real-terms uplift in funding for the programme by 2024-25, taking total planned investment across the next three years to £695m. This funding will enable the programme to continue to deliver until March 2025.

This investment represents a major expansion of the Supporting Families programme. This funding will enable local authorities and their partners to provide help earlier and secure better outcomes for up to an additional 300,000 families across all aspects of their lives and deliver savings for children’s social care over this three-year period. The new investment in the programme follows a robust national evaluation showing that the programme was successful in reducing the number of children needing to be taken into care.

Year ahead

As we reach the tenth anniversary of Supporting Families, the 40% expansion of the programme is a significant milestone. This enhanced funding will enable local authorities to provide more meaningful, practical help to families, and provide earlier support to more families with complex needs.

Over the last ten years, the programme has achieved positive outcomes for over 470,000 families. Positive evaluation findings have given us confidence that the programme is effective. After ten years of work we have seen huge progress on systems change with improved local partnerships and joined up delivery across services.

The Department for Levelling up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC) and the Department for Education (DfE) will work together closely on the new programme with joint governance across the two departments. We have a strong shared objective to deliver early help to even more families and prevent high-cost statutory interventions such as children going into care. We look forward to the findings of the Independent Review of Children’s Social Care and the role that Supporting Families can play in helping create a better system of support for families and children for the future. We will make sure that family voice continues to inform our policy decisions in this new phase.

The investment is part of a wider package to deliver more early help support for families and improve outcomes for children and families. The combined Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC), DfE, and DLUHC £500m package announced at the Budget and Spending Round includes investment in family hubs and funding to transform ‘Start for Life’ services in half of local authorities in England.

Successful family outcomes for 2021-2022

Successful family outcomes are the way the programme records positive change at a family level. In most local authorities successful family outcomes can be claimed through a Payment by Results claim. Fourteen local authorities have Earned Autonomy status and Greater Manchester has a devolution deal with the government. These local authorities receive all their funding up front and do not make Payment by Results claims, however, they continue to track and report successful family outcomes. The figures in this report combine the Payment by Results outcomes and the successful outcomes from Earned Autonomy local authorities and Greater Manchester.

There are two types of Payment by Results claim: the first is significant and sustained progress and the second is continuous employment. For a significant and sustained progress claim, a family must have made sustained improvements with the problems that led to them joining the programme. For a continuous employment claim, a family member must have achieved sustained employment.

Why we track family outcomes

Each family outcome represents a family whose life has substantially changed for the better, which is a central aim of the programme. Outcomes represent the positive work by a family, the keyworker, and other services supporting that family. Tracking outcomes is also an important way that authorities are able to understand local need and what works in their local authority.

Each local authority has an Outcomes Plan that sets out the indicators of eligibility and progress needed to evidence a successful outcome against the six headline objectives set out in the Supporting Families programme guidance. These are:

- Staying safe in the community: parents or children involved in crime or anti-social behaviour.

- Getting a good education and skills for life: children who have not been attending school regularly.

- Improving children’s life chances: children who need additional support, from the earliest years to adulthood.

- Improving living standards: families experiencing or at risk of worklessness, homelessness or financial difficulties.

- Staying safe in relationships: families affected by domestic abuse.

- Living well, improving physical and mental health and wellbeing: parents and children with a range of health needs.

Progress on successful family outcomes up to 2022

The latest figures submitted up to 05 January 2022 show that a total of 55,421 families have achieved successful family outcomes in 2021-22, representing 79% of the national allocation of outcomes for 2021-22. With three months of this financial year remaining, local authorities are on target to meet their allocations of successful family outcomes for 2021-22.

These outcomes build on the 414,955 successful family outcomes achieved by the Troubled Families Programme between April 2015 and March 2021. Successful family outcomes in previous years are available in previously published annual reports on gov.uk.

Figure 1: Number of successful family outcomes achieved through Supporting Families from April 2021 up to 05 January 2022

Validation of claims

The validation process makes sure that local programmes are meeting the national programme requirements. It is also referred to as the assurance or ‘spot check’ process.

The assurance process seeks to make sure outcomes meet the criteria set out in guidance and in a local authority’s own local outcomes plan. There is also a review of how local authorities use their case management and data systems and how they are progressing against the sign-up conditions[footnote 1]. On an assurance visit, the team meet with keyworkers and partners to understand how whole family working is being embedded within the local authority and how early help is being delivered. The team offer support and guidance to the local authority. Increasingly population level data is used to support the conversations.

This year, as a result of robust checks undertaken to date, experienced local auditors and having access to a wealth of information, the national team took a more nuanced approach to the assurance process. The team introduced a risk-based approach across both Payment by Results and Earned Autonomy outcomes. This approach enabled support to be directed where it was most needed. Indicators used to determine local authorities that may benefit from an assurance visit included:

- An unexpected number of family outcomes.

- Issues identified during a previous engagement.

- No engagement for a significant length of time.

- A local authority identified as needing performance improvement support.

These indicators are not exhaustive and are not looked at in isolation.

As of the end of January 2022, six assurance visits had been conducted. The vast majority (97%) of claims have been found to be valid, with invalid claims removed from the claims total.

Case study one: A family’s journey of improvement

This case study illustrates the multiple complex needs a family on the programme experiences and what a successful family outcome means in practice. Please note that all names and identifying features in this case study have been changed to preserve confidentiality.

Julie, 27, is a single mum to four children; Tom, 9, Jake, 6, Molly, 3, and Chloe, 1. She feels quite isolated and doesn’t have a strong support network around her.

What problems did they have?

Julie was referred for early help support by Tom’s school. He was not progressing well, had poor attendance, demonstrated some behavioural issues and they were concerned that he may have some educational needs.

The keyworker, Martin, did an early help assessment with Julie and the whole family to understand their needs. This assessment helped Julie understand how her own mental health problems and feelings of isolation were impacting her and the family. They were also able to identify the family’s unhappiness in their home was due to financial worries which meant they were unable to pay bills or furnish the home. Julie also identified some potential development needs of the two younger children.

What help did they receive?

Martin liaised with other professionals on behalf of the family and coordinated the support the family needed. Martin made sure Julie was accessing support from her GP to address her mental health issues. He supported Mum and Tom through the Special Educational Needs Coordinator (SENCo) assessments at school and Tom was also seen by the educational psychologist.

Martin went with Julie, Chloe and Molly to visit the local nursery and children’s centre. He worked with the perinatal team to secure a placement at nursery for Molly and provision through the children’s centre for Chloe.

Julie participated in a parenting programme to enable her to be confident in putting bedtime routines and boundaries in place for all the children. She also took part in a domestic violence programme to help her identify unhelpful relationship patterns. Martin also helped Julie see how she had become isolated from her family and supported Julie in reopening the conversation with her own mum.

Martin referred Julie to the Supporting Families Employment Advisor (SFEA) who signposted Julie to where she could access essential baby items and furniture for the children and where she could access debt advice.

What progress was made?

Julie is more confident and happier. She is able to better manage the children’s behaviours and routines and knows who she can talk to at school and nursery for support and feels able to do so. The training helped her improve her relationship with her mum. Chloe and Molly are settled in nursery and attending children’s centre provision. Julie is also engaging with other mums at the centre and feeling more involved and less isolated.

With the right support in place, Tom is now happy attending school which has improved his attendance and his behaviour. He is feeling happier and less stressed which has led to improved behaviour at home, especially in the mornings getting ready for school, which has made Jake happier at home too. Tom is making friends and sharing stories about what he enjoys at school, and he can see the progress he has made.

Working with the SFEA to put payment plans in place for debt, as well as helping the family’s finances, has lifted a weight from Julie and helped improve her mental health and stress levels.

The improved atmosphere in the house, along with the new furniture, makes homelife happier and more comfortable. Julie can see the children are happy and is working with the SFEA to plan for the future. She is planning on starting work when Chloe is able to access full time nursery provision. She is preparing herself by doing online courses now, which she had never considered as an option for her before.

National programme developments

The national team co-designs programme developments with local authorities and other public services across the country. This section sets out developments in the programme over the past year, including a new outcomes framework, an updated funding formula, an improved Early Help System Guide and a refreshed approach to Earned Autonomy.

New outcomes framework

The Supporting Families Financial Framework, originally designed in 2014, defined which families were eligible for support based on their needs, and what was included in the six headline criteria of the programme. This document served as the guidance for Payment by Results funding. Local authorities then had flexibility to define specific indicators of need and what outcomes they would work towards in their “Troubled Families Outcomes Plans”.

Given the previous framework was initially created back in 2014, it needed updating to reflect the current needs of families and to make sure that local authorities could continue to target intensive support at those who need it most. The national Supporting Families team have used the past year to co-design a new family outcomes framework with local authorities and other government departments which outlines the family needs and corresponding outcomes everyone should be working towards.

It was important to focus on providing support to families where there are multiple risk factors and avoid some of the poorest outcomes for families such as family breakdown, children entering care, involvement in the criminal justice system and homelessness.

Figure 2: The ten headline outcomes in the new outcomes framework

What has changed?

The main change is the programme moving from six headline criteria to ten outcomes: getting a good education; good early years development; improved mental and physical health; promoting recovery and reducing harm from substance use; improved family relationships; children safe from abuse and exploitation; crime prevention and tackling crime; safe from domestic abuse; secure housing; and financial stability.

This enables local authorities to report in much more detail on the actual problems families are facing. This means families should receive a truly holistic assessment, considering the interdependencies of the needs of individuals within the family. The pre-determined outcomes and evidence measures will push local authorities to work towards ambitious outcomes for families. It also helps the national team focus in on newer areas of priority for the programme such as secure housing and good early years development.

The national team are also providing much more guidance on what good looks like for these outcomes and what levels of evidence would be expected when measuring these outcomes. This will help build consistency of outcome measurement across the country and give clearer guidance to local authorities on what is expected, but also what is possible.

Updated funding formula

The policy narrative ‘Supporting Families 2012 to 2022 and beyond’ committed to reviewing and updating the current funding distribution model. The Supporting Families national team consulted with local authorities on these changes in 2021.

The first change that has been made is updating the data sources. The programme has always allocated funding to local authorities based on estimated overall need, as established by the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) and population. These data sources are used to determine how many families in each local authority are potentially eligible for Supporting Families. The formula previously used 2015 data for deprivation and population data from 2011 and these figures are now several years out of date. The data has now been updated to the 2019 IMD and 2017 population estimates and will continue to be updated as more data becomes available. In line with the levelling up agenda, updating the formula with 2019 IMD data ensures we reflect current need by redistributing funding to the more deprived areas.

The second change that has been made is to simplify the funding formula by removing the Income Deprivation Affecting Children Index (IDACI) adjustment from the calculation. The simplified formula uses the untransformed IMD. Removing the IDACI adjustment improves transparency by increasing clarity on how decisions have been made about funding and simplifies the process.

This updated funding formula was used in the calculation of funding allocations across the next Spending Review period (2022-25).

Refreshed Early Help System Guide

In the March 2021 policy narrative ‘Supporting Families 2021-22 and beyond’, the national team committed to work with local authorities to “identify the key features that underpin a successful local system and map these into a ‘transformation road map’ alongside exploring what we can do to better incentivise progress against these, including the possibility of financial rewards”.

Ten local authorities came forward to work with the national Supporting Families team on refreshing the Early Help System Guide (EHSG) and to consider how transformation in line with the descriptors in the EHSG could be encouraged. The team worked with these local authorities, as well as key government departments, to improve the content and clarity of the self-assessment process and consider options for encouraging transformation.

During September a refreshed version of the EHSG and a proposal for how transformation could be further incentivised was released for informal consultation. As a result of the consultation and helpful feedback from local authorities, the EHSG was further improved and the refreshed version is being published alongside this document. Local authorities will be required to conduct a self-assessment against the EHSG and to commit to three descriptors from the EHSG they will work towards during the coming year with the possibility of future funding being delayed if progress is slow.

Refreshed approach to Earned Autonomy

In 2018, the programme launched a pilot to test a new up-front funding model for local authorities. Fourteen local authorities were granted Earned Autonomy status after making a successful case through an application process that receiving all their funding upfront would accelerate their local transformation. These local authorities do not make Payment by Results claims, however, they continue to track and report successful family outcomes. The selected local authorities were Barking and Dagenham, Brighton and Hove, Bristol, Camden, Cheshire West and Chester, Durham, Ealing, Islington, Kent, Leeds, Liverpool, Sheffield, Staffordshire and Westminster. In addition to the 14 local authorities, Greater Manchester Combined Authority (GMCA) currently receive the Supporting Families funding for the ten Greater Manchester local authorities through a devolution agreement which began in 2016.

During 2021, the national team carried out a formal consultation with local authorities around connecting Earned Autonomy more closely with system maturity. A prospectus is being published setting out the level of maturity local authorities and their partners will need to demonstrate to move to Earned Autonomy status.

Local service improvement

This section outlines some of the work of central and local government over the last year to improve services, identify and share good practice and promote data sharing. This section includes analysis of self-assessments completed by local authorities using the EHSG, the Local Data Accelerator Fund, data maturity survey results, Early Help Data Pilot, developing good practice and webinars and digital showcases.

Learning from Early Help System Guide assessments 2020-21

The Supporting Families programme has been, since its inception in 2012, funding and advocating for transformation in the early help system. Early help is the total support that improves a family’s resilience and outcomes or reduces the chance of a problem getting worse. In 2020, the national Supporting Families team published the Early Help System Guide (EHSG) which gave a national vision for early help and a self-assessment designed to guide conversations between partners, think about the right questions, and develop a common language for the changes we all want to see.

During 2020-21 local authorities used the EHSG to self assess the maturity of their early help system.

What did the self-assessments show?

The Supporting Families team carried out analysis of the self-assessments submitted by local authorities. 133 (89%) local authorities returned a self-assessment. Whilst these varied in in terms of quality and quantity of evidence, the self-assessments have provided a rich source of insight into the good practice developing in local authorities and have been used by the team to approach local authorities for case study material to be shared more widely. The following provides a summary of some of the key themes arising from the self-assessments.

Whole family working

Working with the whole family, understanding how their needs interact and coordinating the support they need, has always been a core aim of the Supporting Families programme. Achieving whole family working continues to be at the centre of the objectives of the programme including expanding the range of different services who work in a whole family way. The analysis of evidence provided in the self-assessments submitted suggested that in 80% of local authorities, whole family working was in place in core internal local authority services, for example, family support and children’s centre and early help services. In 58% of local authorities the evidence suggested that this practice extended beyond the local authority to at least one other partner. In 28% of local authorities, the analysis showed that whole family working was more widespread in a wider range of services. The results of this show whole family working appears to be widespread within local authority services and extending to a wider range of services for many, but that there is more to do to make this way of working commonplace.

Health visiting and whole family working

98% of local authorities answered, ‘yes’ or ‘mostly yes’ in response to ‘do health partners practice whole family working and act as whole family worker when appropriate?’. The evidence provided in the self-assessments identified that for many local authorities, whole family working is in place in health visiting services and in some local authorities it is in place around school nursing. In many local authorities, this has been accelerated in response to commissioning of these services moving into local authorities. In some local authorities, health visiting and school nursing services are integrated with other family support and early years professionals in children’s centres or family hubs.

A number of local authorities also reported having link workers or practice developers in place to support the embedding of whole family ways of working. This type of role is someone who understands both the aims of the programme and the service they are aiming to support to change practice. This role would provide, for example, training, coaching or supervision to enable this. Developing a whole family assessment tool aligned to the early help assessment or providing access to case management systems has, in some local authorities, helped accelerate joint working. In a small number of local authorities, a proportion of the overall health visiting service have been commissioned to work in a whole family way and act as whole family worker.

Team Around the School approaches

The Team Around the School approach is a mechanism for schools to meet with family support services and other key partners on a regular basis to have a joint conversation about children and young people they are worried about. Through this approach, partners develop a shared understanding of the profile and needs of the school and local community to enable earlier intervention.

75% of local authorities answered, ‘yes’ or ‘mostly yes’ in response to ‘are relevant professionals working together in a Team Around the School approach to anticipate and respond to the needs of the school?’ The analysis shows that this approach is well established in some local authorities while others are either pilots or developing from projects within a local authority. The analysis, however, also shows there is no common model for Team Around the School. Many local authorities have dedicated single points of contacts for early help in schools while some local authorities link to other teams such as inclusion or school improvement. Several local authorities have social workers linked or based in schools whereas others may have an approach where schools can contact a social worker or other professional for information and advice. A number of local authorities have locality-based models working with school clusters rather than individual schools as part of a wider locality model. This is a model that is developing across the country and the Supporting Families team will continue to work with DfE and local authorities to explore this and develop practice examples for sharing.

Development of practice models

77% of local authorities answered ‘yes’ or ‘mostly yes’ in response to ‘is there a shared practice model and set of processes for professionals in partner agencies working across the wider early help system?’. There were a variety of themes in response to this question. Some local authorities described their overarching practice framework for working with families whilst others focused specifically on the early help model of practice.

Many local authorities described having an overarching practice framework that was implemented across children’s social care and their more intensive family support service. Some local authorities have implemented their framework across early help and with partners, whilst others reported plans to do this. Practice models were commonly described as being grounded in systemic practice; signs of safety; strengths-based approach; relationship-based approach; adverse childhood experiences and trauma-informed practice; restorative practice; and, in a small number of local authorities, the Thrive model, which is an integrated, person-centred and needs-led approach. Local authorities often described their frameworks as encompassing more than one of these approaches and models.

Many local authorities described their early help model in terms of the early help assessment, multi-agency planning and Team Around the Family meetings. Team Around the Family is a meeting between a child or young person, their family and the group of practitioners who are working with them. A significant number of local authorities mentioned work with partners as needing development in relation to developing a shared framework and/ or their role in implementing early help processes. A small number of local authorities mentioned that shared case management systems enabled partners to fully participate in early help whole family processes.

Collaboration with the voluntary and community sector

The Early Help System Guide places a strong focus on local authorities and partners working closely with the voluntary and community sector. This includes building positive and collaborative working relationships to engage voluntary and community groups proactively, and building capacity in communities to enable help to be provided at the earliest opportunity by those closest to families. The analysis of evidence provided for self-assessments showed that there was evidence of some or extensive collaborative working with the voluntary and community sector and vision to do more for 71% of local authorities. For many, the response to COVID-19 necessitated and facilitated these closer working relationships and many local authorities expressed their intention to continue to build on this activity in their local authority. This positive trend is something we will continue to support and encourage through the national programme.

Family voice

The experience of families who have received support or need it should be heard routinely and acted upon to improve the way support is provided. The analysis of evidence from the self-assessments showed that whilst for 57% of local authorities there was evidence that there were methods in place to gain and act on the voice of families and for many there were plans to do more, for the remainder there was limited evidence this was happening. There is clearly much room for improvement around family voice and lived experience and this has been the subject of a good practice project this year.

Quality assurance approaches

The Early Help System Guide asks local authorities to consider the quality of early help practice, including assessment, planning and delivery. When asked ‘whether they knew the quality of early help practice across professionals, including health and education sectors?’, 74% answered ‘yes’ or ‘mostly yes’. There were a variety of quality assurance methods described, the most prevalent being case audits. Many of these were for partner-led as well as local authority-led cases, with some being collaborative, multi-agency or thematic.

Some local authorities described their auditing of early help cases being embedded in over-arching quality assurance frameworks, led by the local authority, multi-agency partnerships or Local Safeguarding Children Partnership arrangements. Other methods described as being part of the measure of quality were practice observations, case supervisions and contract management. In addition, local authorities were asked whether they supported partners with regard to improving quality. Most described models of support through advice, training, workforce development and roles such as ‘Linked Worker’, ‘Multi-Agency Practice Lead’ or ‘Early Help Coordinator/Consultant’. The most common areas for further development were increased quality assurance with partners and revising quality assurance frameworks.

Learning from the analysis

The analysis of Early Help System Guide self-assessments and lessons learned have informed the development of the next iteration of the guide. We have improved the detail in the descriptors, reduced duplication and improved the scoring system. This will improve the quality of the analysis of the next round of self-assessments.

Local Data Accelerator Fund

The Local Data Accelerator Fund is a £7.9m innovation fund that was announced for 2021-2022 and 2022-2023. It aims to improve services for children and families by improving the local use of data. This funding is provided by HM Treasury’s £200m Shared Outcomes Fund and is part of a wider Data Improvement Across Government programme that was announced in 2020.

Local authorities and other local agencies bid for funding in groups as a partnership and were asked to propose an exemplar project involving sharing and linking data from multiple agencies to improve services for families. They were also asked to propose work to share skills and good practice. Ten projects were awarded funding for the two years.

Many of the projects are directly relevant to family support/early help services. These include:

- Data modelling to identify families that require early help and support from services, with a focus on financial problems and homelessness (Nottingham and partners).

- Developing a single-family view and protocols on use of data enabling them to identify family need, get information to frontline practitioners and evaluate effective practice (Berkshire).

- Developing data standards for recording and reporting on early help services, enabling local authorities to look at what works and understand how services succeed (East Sussex).

Case study two: Local Data Accelerator Fund project

Avon and Somerset Data Partnership

Since 2015, Bristol City Council has evidenced the transformative effect data can have on public services and demonstrated how advanced analytical techniques can enable services to intervene earlier, save money and improve outcomes for children and families. For this project that is being funded through the Local Data Accelerator Fund, Bristol have partnered with four other local authorities, the police, educational settings, NHS commissioning support unit and academic partners to implement a consistent ‘state of the art’ capability across the whole Avon and Somerset police force area.

The data partnership will aim to establish a simple, sustainable and consistent approach to two-way information sharing between local authorities and the police which will enable the scaling up of risk modelling across the region. A pilot project in educational settings within high deprivation areas of Bristol and Somerset provides the feasibility to test that the risk modelling is accurate and test the hypothesis that increased access to information provides improved outcomes for children through better decision making. The academic partners will assess the impact that access to safeguarding information can have on educational and social outcomes. This study will shape the rollout of databases into educational and health settings across the region and create a blueprint for others to replicate.

The partnership will scale the ‘Insight Bristol’ multi-agency hub into a regional approach and create a common area wide information sharing governance framework which will enable less data mature local authorities to make rapid progress and an ethical framework which will improve community confidence and transparency around the use of data. This will create an infrastructure which facilitates a better understanding of the intersecting issues that form ‘vulnerabilities’ for families.

Data survey results

Supporting Families has always promoted the use of data as an intrinsic enabler to help local services to identify, understand and better support children and families at the right time to prevent them reaching crisis point. Data is a critical part of any strong early help system, beyond the Supporting Families programme. Good use of data helps the partnership to evaluate interventions, provide better and more timely support to families by identifying problems earlier as well as informing their strategic and commissioning approaches.

The Supporting Families Data Survey ran for its third year in 2021. Every year the national team ask all upper tier local authorities to complete a comprehensive survey on their data maturity, systems, reporting and analytics. The response rate is extremely high, with 99% (148 /150) of local authorities responding in 2021.

Sharing data between agencies is the first building block of any mature data system. Compared to 2020, the levels of data sharing across local authority partnerships have remained broadly stable.

-

Overall, 22% of local authorities said data sharing had improved over the last twelve months, 74% said it had stayed the same and 4% said it had decreased.

-

Internal local authority data are the most often shared. For example, this could include those not in education, employment or training, children’s services data and education census and exclusions data. Compared to 2020, the survey shows some small increases across these datasets, and a larger six percentage point increase in those accessing children’s social care data, which is intrinsic to understanding the family’s journey through services.

-

There have been some slight changes in police data access, with 16 local authorities reporting that they have gained a police feed since 2020. The proportion accessing youth offending and adult offending data both continue to be slightly under 50%, demonstrating there is still significant work to do to promote sharing data. In 2021-2022 we have a project focused on improved data sharing between police forces and local authorities.

-

Approximately a third of local authorities access housing and homelessness data. The national team have been working on a project in 2021-2022 with local authorities and central government colleagues to expand access to these datasets.

-

Low levels of data sharing with health partners at a local level continue, with less than 20% of local authorities reporting receiving these data feeds. In 2021-22 our work with health colleagues to develop data sharing pathways for local partnerships has accelerated. The national team have a project with a dedicated lead and intend to produce guidance for local authorities to help them navigate accessing this data.

-

32% of local authorities have been able to provide data held by services to family workers to inform their work with families and enable more holistic assessments and action plans. This has seen a slight decrease compared to 2020, so the national team are holding workshops about this to understand it more fully.

-

Almost three quarters of local authorities now have outcome measures integrated into their case management systems, allowing for quantitative reporting across all cases and therefore understanding of what issues families are facing and outcomes families are achieving.

-

Almost half of the local authorities responding said that partner organisations complete assessments on the same case management system as the local authority, promoting shared practices and visibility of cases across services.

To make sure that data can be used to inform decision making at a strategic level both locally and nationally, it is essential to provide analysis and reports that explain what families are experiencing. Almost three quarters of local authorities provide strategic level reports on the numbers of families worked with and the outcomes achieved by families. In 2021, 39% of local authorities said that they are able to report on the needs of the population and therefore understand the demand on services (remaining broadly stable compared to 2020). There continues to be a strong appetite to develop needs analysis with 54% of local authorities saying they intend to be able to complete this within the next twelve months. It is important that local authorities continue to expand the application of needs analysis which informs decisions about what resources are required to support families.

At the end of the survey local authorities are asked to categorise their data maturity into one of six models, increasing in maturity from manual to advanced, as detailed below:

- Manual - Receiving data from other partners which is stored in separate files and which is unmatched to case management systems. The local authority Supporting Families Outcome Plan is not quantified and there is no reporting from the case management system to keyworkers.

- Basic - Some data sources are brought together in basic data software, which is used to match and store data, identify families who may need support and to monitor progress. The Supporting Families Outcomes Plan is embedded in the case management system and receives manually inputted reports on outcomes and key indicators.

- Building blocks - Bringing most data sources together including early help case management data. The data is visible to keyworkers in a spreadsheet or form which is only provided once or twice during a case.

- Early maturity - Using a data warehouse or data lake where data is accessible to workers automatically in the case management system and which is updated when new feeds are received. More advanced data system software is used with automated matching and calculation of whether Payment by Results outcomes are met is built in. There are likely to be some open feeds.

- Mature – Data warehouse or data lake model as in the early maturity model but where primarily open feeds are used and where data is used to conduct needs analysis.

- Advanced - Sophisticated data model with open feeds as in the mature model, but where the system has been expanded beyond Supporting Families services and includes whole children’s services or whole of council solutions.

Advanced use of data in Liverpool

Liverpool City Council is an example of a local authority with an advanced data model. Liverpool used their existing Supporting Families data system and built a bespoke COVID-19 data linkage module into it, working against time to establish the system change ahead of the anticipated peak of the pandemic in May 2020. Before the height of the pandemic was reached, Liverpool was able to create an essential ‘vulnerability index’ of individuals and families in case the prioritisation of food, prescription deliveries or care packages were needed.

See more details in this Supporting Families blog post.

The survey results show 21% of local authorities are operating early mature to advanced models. These local authorities have offered excellent examples of how data are being used to support families. These examples are used alongside a suite of national and peer support networks to help local authorities who are operating with manual, basic or building blocks models to develop to more mature models that are better equipped to effectively support families.

Figure 3: Percentage of local authorities on a six-point scale of data maturity

DLUHC are using this intelligence to develop a refreshed support offer for local partners including:

-

Identifying and sharing good practice through a programme of webinars.

-

A national online forum for all Supporting Families analysts.

-

Developing data sharing guidance for partnership sharing of specific data sets.

-

Tailored one-to-one support for local authorities, focusing on unblocking specific issues.

-

Focus groups on the barriers to data sharing.

-

SQL training offered to one Supporting Families analyst in every local authority.

-

Working with other government departments to provide joint support.

Having this clear overview of how well data is being used in local authorities helps shape the future programme to make sure that families are receiving the most effective support at the right time.

Early Help Data Pilot

As part of the 2021-22 programme, all Earned Autonomy local authorities were asked to take part in a pilot to explore if it was possible to capture national level data on all families who are being worked with by early help partnerships across the country. The aim is to better understand families’ needs, which services are providing support and the outcomes achieved.

This data will enable central government and local authorities to resource and commission support more effectively, targeting specialist support at specific issues and a better understanding of the complexities of issues families are facing.

This was a ground-breaking pilot to see if it is possible to capture data to inform national and local support packages and policies for families. The future of the pilot is now being considered including whether this should be rolled out across the programme over the next Spending Review period.

Developing good practice

During 2021-22, six local authority secondees have worked with the national team on a part time basis to bring in local expertise and develop a series of good practice projects. The projects cover a range of themes and aimto improve data sharing standards, develop guidance on data sharing and share good practice.

Housing and Whole Family working

Applications were sought for a funded Housing and Whole Family working pilot programme. The pilot aims to test methods for increasing whole family working amongst housing partners by systemically identifying issues early and improving data sharing between housing services and early help and family support services. Five local authorities were successful in their bids for funding and commenced work on their projects in summer 2021. A total of £214,902 was granted to these local authorities.

The five local authorities that were successful are:

- Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole £59,500

- Lincolnshire £41,859

- Dorset £25,000

- North Tyneside £46,543

- Somerset £42,000

The national team are working with the Housing and Whole Family pilot local authorities as they develop their projects to maximise impacts through action learning. The project aims to share best practice with all local authorities, focusing on developing activities including cross team training between early help and housing, improved data sharing and mentoring and co-location in teams.

Summary of other projects

-

A council tax data sharing project to share good practice from local authorities that have experience of using council tax data and produce guidance that will help support local authorities with using this to overcome challenges.

-

A project working in partnership with DHSC to explore good practice and challenges to improvement in mental health and wellbeing.

-

A collaborative project with DfE to understand what works in responding to school attendance issues within wider early help systems and to make sure there is a whole family response to attendance issues. Following an initial webinar where a selection of local authorities highlighted their good practice in this area, a series of three action learning sessions were jointly facilitated by DfE and DLUHC. These sessions also had input from local authority attendance teams, Supporting Families Coordinators and a Multi-Academy Trust representative.

-

A project to improve data sharing between the police and local authorities, working in partnership with National Police Chiefs Council (NPCC) and the Home Office. The outcome of the project is to issue programme data sharing guidance endorsed by partners to support and promote the benefits of sharing data.

-

A project exploring how whole family approaches are currently implemented in local authorities to support the prevention of young people’s offending behaviour, with support from the Ministry of Justice Youth Justice Policy Unit, the Youth Justice Board and Association of Youth Offending Team Managers. A national survey completed by over 60 youth justice services and a series of deep dive visits to local authorities were completed. The outcome will be a report to help inform future practice and policy.

-

A project on family voice and lived experience to identify and share good practice from local authorities where they are involving families in the design and delivery of the Supporting Families programme and promote continuous improvement in this area.

-

A joint project with the Home Office on Violence Reduction Units (VRUs) and whole family working. There have been deep dive visits to a range of VRUs and to linked local authorities to explore themes around driving and supporting a joined up local system, the significant role of families and communities in identifying solutions to the challenges they are facing, and identifying and sharing good practice. These visits will be summarised in a report to inform future policy and practice.

Good practice webinars and digital showcase events

The national team has continued to host webinars, workshops and digital showcases to develop and share good practice. Webinars were held on themes such as youth crime, school attendance, housing, police data sharing and adverse childhood experiences. Several digital showcases have been hosted this year, giving local authorities a platform to share the innovative ways they use data.

New research findings

Alongside this report, the programme is publishing a new research report by the independent research organisation Kantar. This looks at effective practice and service delivery in local authorities. This section summarises the main findings of the research.

Background

Supporting Families has a clear model of family intervention, which has proven to be successful in achieving positive outcomes for families. There is significant variation, however, in how the programme is delivered in different local authorities.

The research builds on the findings from the national evaluation by looking at how practice and service delivery varies in different local authorities. It considers what approaches to practice and service delivery are most effective in achieving positive outcomes for families.

Kantar worked with eleven local authorities and conducted a series of interviews with local stakeholders including local authority staff, partner organisations and families. The research report covers different models of programme delivery, the role of keyworkers and other local partners, engagement methods with families and use of data.

Programme delivery models

Supporting Families is viewed as an intrinsic part of the early help system and is embedded in various ways. The size, structure, existing infrastructure, and geography of a local authority influence the complexity of the delivery model of the programme.

The research describes the range of Supporting Families delivery models in the case study areas and has categorised the models based on how embedded the programme is in the early help local system and who works with the families. There were three different delivery models identified among the case study areas.

1. Mainstreamed – The local authority has completely embedded the principles of whole family working across the workforce, including partners. The local authority and partner services share the responsibility for families and any professional could, in theory, take on the lead practitioner role.

2. Targeted – The local authority has teams embedded in their early help locality models who retain a distinct identity for the tier or type of family they work with. The different tiers vary according to the complexity of the support needs of the family, the number of families they worked with, and the way they worked with them.

3. Hybrid – The local authority combines elements of the other two models. The model promotes the importance of all partners and agencies having a joint responsibility to reach out and work with families but also recognises the need to provide a more targeted family support offer for families who have more complex needs.

The research highlights some key learning and recommendations on the topic of programme delivery models, including:

- Adopting locality models - It is important to recognise the importance of local context and continue to support the diverse ways in which local authorities have implemented their practice model, whether these are mainstreamed, targeted, or hybrid models.

- Making co-location meaningful - Views varied about the importance of co-locating services. To add value to partnership working, it needs to be designed in a way that helps build relationships rather than just for convenience.

- Supporting the workforce - For all models to be effective, the workforce needs to have a clear framework, a shared case management system and shared language to guide their work with families. The workforce will also benefit from an induction, training, and supervision programme to develop their skills and a system for quality assuring their practice.

Keyworker and lead practitioner roles

The research highlighted that keyworker caseloads need to be carefully and flexibly managed. Length of support varied across local authorities and families. The focus was on empowering families and striking a balance between making positive changes and families not being too reliant on the keyworker.

Keyworkers felt that there was a need for more consistent training and greater access to specialised training across areas such as mental health. A more universal approach to the training and development of keyworkers and lead practitioners would help to professionalise this workforce.

There is no one size fits all approach, it is the role of the keyworker to build an effective but flexible plan of support for families. Keyworkers also play a role in understanding how to effectively sequence support, taking into account core needs of the family, the reasons for referral, what issues are most urgent, easy wins, and understanding what is most important for the family. This also involves liaising and working with wider organisations to provide specialist support.

The research demonstrated the importance of effective partnership working. The combination of keyworker and partner delivered interventions was key to achieving successful outcomes with families. These wider partner organisations are important for providing specialist support outside of the keyworker remit, particularly for intensive interventions for higher complexity cases involving mental health and/or domestic abuse.

On the topic of keyworkers and lead practitioner roles there were some recommendations from the case study research including:

-

Intervening as early as possible - The system is seen to work reasonably well to help families get back on their feet, but it was still felt to be too reactive and intervening too late at times. More could be done to help identify and support families before they reached the point of crisis. High demand leads to a focus on presenting issues, rather than proactive preventative support. Suggestions included aspects such as greater training and support for schools to provide mental health support to children and continuing to build awareness of the programme and thresholds across all organisations working with children and directly with families.

-

Making sure caseloads are manageable - Keyworkers benefitted from lower caseloads to have more time to implement good practice when working with families. For complex cases, somewhere between five and ten families was generally viewed as appropriate to be able to complete the intensive work required.

-

Sequencing support to meet family need - As there is no one size fits all approach, it is important to provide a range of evidence-based and locally tailored programmes so that support can be tailored to the diverse needs of families.

-

Improving workforce training - Key priority areas for investment and continuing support included the training and professionalisation of the keyworker and lead practitioner workforce.

-

Partnership working and adopting practice models - Investment in good partnership working is key. For example, shared practice models, networking, co-location, communication, shared case management and peer discussions.

Recognising the diversity of family types and tailoring support

The research found that there was no ‘typical’ family on the programme and so the support offered to families was not based around offering similar support to seemingly similar types of family. Families had unique needs and circumstances and there was no one size fits all approach, even for families with similar characteristics. Complexity and need could also change over time due to changed circumstances or the uncovering of additional issues as the keyworker learnt more about the family.

Keyworkers described a number of effective approaches that helped to engage families on the programme including assessment tools, achievable goals and quick wins. Assessment tools can help to create a shared language between the family and keyworker and providean opportunity to focus on positives as well as negatives, in an objective non-judgemental way. Setting achievable goals and communicating these clearly were seen as effective in the family feeling that the programme is manageable. Creating quick wins were seen as important to gaining trust and engagement early as they are focussed on sorting important problems quickly. Along with these approaches, keyworkers emphasised the importance of having time and being available for families to build rapport and trust with them.

On the topic of families, engagement and support there were some recommendations from the case study research including:

-

Offering a bespoke plan for each family - The complexity and fluid nature of working with families means that local authorities are not designing their approach to address a specific typology of families. It is therefore vital that each plan is tailored to the individual circumstances and needs of each family.

-

Tailoring the intervention to the level of complexity - As there is no clear typology of families, it is recommended that the Supporting Families programme continues giving local authorities the flexibility to tailor their approaches to the individual circumstances of each family. Local authorities did distinguish between high and low complexity families. High complexity families were often considered on the edge of care (high end of level 3 or equivalent, on the threshold of need) and could have anywhere between six and eight issues including complex combinations such as mental health, domestic abuse and safeguarding issues. This group required longer, and a greater number and variety of interventions. Lower complexity families tended to present two or three issues and were often situated at level 2 or lower level 3 on the threshold of need. Common issues for this group include parenting and education needs and they required a shorter intervention. However, this distinction was treated flexibly as it is recognised that families’ levels of complexity will change during their time on the programme.

-

Adopting effective engagement methods – Keyworkers described a number of effective approaches that helped to engage families on the programme including assessment tools, achievable goals, and quick wins. Along with the range of engagement methods, a keyworker’s time needs to be protected and carefully balanced against the resourcing plans and caseloads in each local authority, to allow sufficient time to work with families. Higher caseloads will often mean lower capacity for intense working with families.

Use of data

The use of data has been a core component of the way the Supporting Families programme has operated from the outset. The case studies found significant variation in the sophistication of the systems that local authorities used to manage their data.

On the topic of use of data there were some recommendations from the case study research including:

-

Importance of investing in data - Effective use of data was seen as a crucial element for effective delivery of the programme. It was used to identify families, review and track progress, make Payment by Results claims and to carry out effective evaluation.

-

Partner access to case management systems - Using a case management system and giving access to external partners working with a family was seen as a feature of effective practice.

-

Embedding programme criteria in data systems - To facilitate Payment by Results process (outcomes monitoring), the programme’s criteria and tracking of outcomes needed to be built into case management systems, data systems and processes.

Annex A: Successful outcomes by local authority to 05 January 2022

| Local authority | Maximum funded successful family outcomes 2021-22 | Number of families achieving significant and sustained outcomes up to 05 January 2022 | Number of families achieving continuous employment outcomes up to 05 January 2022 | Total successful family outcomes achieved up to 05 January 2022** | Total successful family outcomes achieved up to 05 January 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barking and Dagenham* | 431 | 404 | 7 | 411 | 95% |

| Barnet | 388 | 305 | 0 | 305 | 79% |

| Barnsley | 386 | 340 | 26 | 366 | 95% |

| Bath and North East Somerset | 122 | 95 | 2 | 97 | 80% |

| BCP | 387 | 340 | 0 | 340 | 88% |

| Bedford | 161 | 137 | 0 | 137 | 85% |

| Bexley | 246 | 90 | 0 | 90 | 37% |

| Birmingham | 2,497 | 2,115 | 0 | 2,115 | 85% |

| Blackburn with Darwen | 292 | 192 | 1 | 193 | 66% |

| Blackpool | 320 | 157 | 0 | 157 | 49% |

| Bracknell Forest | 70 | 46 | 1 | 47 | 67% |

| Bradford | 1,060 | 853 | 4 | 857 | 81% |

| Brent | 560 | 423 | 20 | 443 | 79% |

| Brighton and Hove* | 398 | 314 | 2 | 316 | 79% |

| Bristol* | 716 | 408 | 308 | 716 | 100% |

| Bromley | 297 | 224 | 0 | 224 | 75% |

| Buckinghamshire | 325 | 241 | 0 | 241 | 74% |

| Calderdale | 288 | 193 | 34 | 227 | 79% |

| Cambridgeshire | 496 | 366 | 12 | 378 | 76% |

| Camden* | 367 | 121 | 39 | 160 | 44% |

| Central Bedfordshire | 196 | 150 | 0 | 150 | 77% |

| Cheshire East | 332 | 315 | 4 | 319 | 96% |

| Cheshire West and Chester* | 318 | 235 | 11 | 246 | 77% |

| Cornwall | 700 | 510 | 37 | 547 | 78% |

| Coventry | 552 | 398 | 29 | 427 | 77% |

| Croydon | 533 | 441 | 0 | 441 | 83% |

| Cumbria | 590 | 584 | 6 | 590 | 100% |

| Darlington | 162 | 122 | 0 | 122 | 75% |

| Derby | 389 | 254 | 15 | 269 | 69% |

| Derbyshire | 787 | 477 | 23 | 500 | 64% |

| Devon | 747 | 577 | 0 | 577 | 77% |

| Doncaster | 515 | 469 | 46 | 515 | 100% |

| Dorset | 327 | 253 | 4 | 257 | 79% |

| Dudley | 426 | 342 | 0 | 342 | 80% |

| Durham* | 761 | 687 | 74 | 761 | 100% |

| Ealing* | 526 | 358 | 109 | 467 | 89% |

| East Riding of Yorkshire | 292 | 256 | 3 | 259 | 89% |

| East Sussex | 602 | 582 | 3 | 585 | 97% |

| Enfield | 519 | 358 | 0 | 358 | 69% |

| Essex | 1,322 | 1,004 | 22 | 1,026 | 78% |

| Gateshead | 337 | 197 | 2 | 199 | 59% |

| Gloucestershire | 520 | 505 | 15 | 520 | 100% |

| Greater Manchester* | 4,754 | 4,285 | 0 | 4,285 | 90% |

| Greenwich | 485 | 364 | 4 | 368 | 76% |

| Hackney | 613 | 480 | 0 | 480 | 78% |

| Halton | 236 | 236 | 0 | 236 | 100% |

| Hammersmith and Fulham | 295 | 158 | 64 | 222 | 75% |

| Hampshire | 967 | 712 | 15 | 727 | 75% |

| Haringey | 546 | 474 | 18 | 492 | 90% |

| Harrow | 232 | 225 | 0 | 225 | 97% |

| Hartlepool | 175 | 119 | 13 | 132 | 75% |

| Havering | 253 | 238 | 0 | 238 | 94% |

| Herefordshire | 190 | 144 | 9 | 153 | 81% |

| Hertfordshire | 815 | 675 | 2 | 677 | 83% |

| Hillingdon | 347 | 341 | 6 | 347 | 100% |

| Hounslow | 367 | 299 | 3 | 302 | 82% |

| Isle of Wight | 175 | 120 | 16 | 136 | 78% |

| Islington* | 459 | 459 | 0 | 459 | 100% |

| Kensington and Chelsea | 197 | 130 | 13 | 143 | 73% |

| Kent* | 1,606 | 1,377 | 11 | 1,388 | 86% |

| Kingston upon Hull | 613 | 307 | 113 | 420 | 69% |

| Kingston upon Thames | 119 | 76 | 0 | 76 | 64% |

| Kirklees | 653 | 476 | 17 | 493 | 75% |

| Knowsley | 351 | 154 | 9 | 163 | 46% |

| Lambeth | 608 | 521 | 9 | 530 | 87% |

| Lancashire | 1,505 | 1,300 | 3 | 1,303 | 87% |

| Leeds* | 1,205 | 1,052 | 13 | 1,065 | 88% |

| Leicester | 688 | 573 | 9 | 582 | 5% |

| Leicestershire | 484 | 400 | 0 | 400 | 83% |

| Lewisham | 553 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 1% |

| Lincolnshire | 831 | 822 | 9 | 831 | 100% |

| Liverpool* | 1,180 | 785 | 165 | 950 | 81% |

| Luton | 339 | 150 | 0 | 150 | 44% |

| Medway Towns | 360 | 351 | 9 | 360 | 100% |

| Merton | 201 | 129 | 0 | 12 | 9 64% |

| Middlesbrough | 325 | 323 | 2 | 325 | 100% |

| Milton Keynes | 279 | 143 | 0 | 143 | 51% |

| Newcastle upon Tyne | 526 | 379 | 0 | 379 | 72% |

| Newham | 702 | 587 | 1 | 588 | 84% |

| Norfolk | 992 | 931 | 0 | 931 | 94% |

| North East Lincolnshire | 297 | 135 | 3 | 138 | 46% |

| North Lincolnshire | 220 | 205 | 0 | 205 | 93% |

| North Somerset | 176 | 77 | 1 | 78 | 44% |

| North Tyneside | 258 | 179 | 3 | 182 | 71% |

| North Yorkshire | 471 | 471 | 0 | 471 | 100% |

| North Northamptonshire | 772 | 578 | 2 | 580 | 75% |

| Northumberland | 370 | 303 | 1 | 304 | 82% |

| Nottingham | 670 | 476 | 50 | 526 | 79% |

| Nottinghamshire | 903 | 739 | 55 | 794 | 88% |

| Oxfordshire | 498 | 360 | 0 | 360 | 72% |

| Peterborough | 302 | 135 | 7 | 142 | 47% |

| Plymouth | 416 | 326 | 2 | 328 | 79% |

| Portsmouth | 332 | 188 | 12 | 200 | 60% |

| Reading | 204 | 169 | 0 | 169 | 83% |

| Redbridge | 347 | 274 | 0 | 274 | 79% |

| Redcar and Cleveland | 225 | 140 | 2 | 142 | 63% |

| Richmond upon Thames | 113 | 77 | 0 | 77 | 68% |

| Rotherham | 437 | 312 | 2 | 314 | 72% |

| Rutland | 17 | 11 | 0 | 11 | 65% |

| Sandwell | 684 | 510 | 15 | 525 | 77% |

| Sefton | 372 | 272 | 3 | 275 | 74% |

| Sheffield* | 936 | 704 | 10 | 714 | 76% |

| Shropshire | 276 | 188 | 20 | 208 | 75% |

| Slough | 220 | 175 | 0 | 175 | 80% |

| Solihull | 211 | 190 | 5 | 195 | 92% |

| Somerset | 524 | 291 | 36 | 327 | 62% |

| South Gloucestershire | 183 | 139 | 1 | 140 | 77% |

| South Tyneside | 250 1 | 91 | 1 | 192 | 77% |

| Southampton | 389 | 342 | 0 | 342 | 88% |

| Southend-on-Sea | 258 | 195 | 0 | 195 | 76% |

| Southwark | 583 | 302 | 18 | 320 | 55% |

| St. Helens | 299 | 298 | 1 | 299 | 100% |

| Staffordshire* | 817 | 817 | 0 | 817 | 100% |

| Stockton-on-Tees | 272 | 160 | 6 | 166 | 61% |

| Stoke-on-Trent | 505 | 329 | 5 | 334 | 66% |

| Suffolk | 718 | 531 | 24 | 555 | 77% |

| Sunderland | 443 | 318 | 3 | 321 | 72% |

| Surrey | 646 | 408 | 0 | 408 | 63% |

| Sutton | 194 | 68 | 0 | 68 | 35% |

| Swindon | 229 | 175 | 0 | 175 | 76% |

| Telford and Wrekin | 237 | 146 | 0 | 146 | 62% |

| Thurrock | 213 | 164 | 9 | 17 | 3 81% |

| Torbay | 206 | 116 | 0 | 116 | 56% |

| Tower Hamlets | 639 | 620 | 1 | 621 | 97% |

| Wakefield | 529 | 499 | 0 | 499 | 94% |

| Walsall | 494 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0% |

| Waltham Forest | 522 | 270 | 0 | 270 | 52% |

| Wandsworth | 382 | 379 | 3 | 382 | 100% |

| Warrington | 218 | 136 | 6 | 142 | 65% |

| Warwickshire | 487 | 338 | 0 | 338 | 69% |

| West Berkshire | 94 | 57 | 29 | 86 | 91% |

| West Sussex | 688 | 688 | 0 | 688 | 100% |

| Westminster* | 363 | 204 | 59 | 263 | 72% |

| Wiltshire | 347 | 287 | 0 | 287 | 83% |

| Windsor and Maidenhead | 80 | 60 | 4 | 64 | 80% |

| Wirral | 524 | 451 | 1 | 452 | 86% |

| Wokingham | 59 | 53 | 0 | 53 | 90% |

| Wolverhampton | 505 | 78 | 42 | 120 | 24% |

| Worcestershire | 555 | 435 | 0 | 435 | 78% |

| York | 166 | 108 | 4 | 112 | 67% |

| Total | 69,831 | 53,583 | 1,838 | 55,421 | 79% |

(*) Earned Autonomy local authorities and Greater Manchester (which delivers the programme under a devolution agreement) no longer submit numbers of family outcomes for Payment by Results purposes. Instead, they report successful family outcomes on a quarterly basis. (**) All results are subject to assurance check.

-

As a condition of the programme, local authorities must meet some basic conditions for delivery. Further information on these are in the Supporting Families Programme Guidance (chapter 2). ↩