Leading Public Services through Covid-19 HTML

Updated 10 November 2022

1. Executive Summary

The National Leadership Centre (NLC) supported the Government’s response to COVID-19 by acting as the conduit between Central Government and the NLC’s network of public service leaders. As part of this, the NLC ran a quantitative survey with public service leaders from March to June 2020. The NLC also commissioned Ipsos MORI to conduct qualitative research with their network, which ran from July 2020 to March 2021. This report brings together findings from both strands of research.

1.1 Research methods

The COVID-19 Response Public Service Leaders Survey ran for 12 Waves over 15 weeks, between 20 March and 22 June 2020. The questionnaire was iterated over the 15 weeks to reflect responses from previous waves and changes in the wider context, with questions being added and removed as appropriate. For certain questions, not all codes were shown to all sectors, which impacts the ability to compare across waves. These have been highlighted where appropriate.

The first nine survey Waves ran weekly (20 March to 11 May), with the remaining three Waves running fortnightly (26 May to 22 June). All members of the NLC Network were eligible to participate in the survey, along with leaders from the Public Service Leadership Group (PSLG) from Wave 2 onwards. The response rate declined across the waves. This makes it more difficult to complete sector specific analysis in later waves, when the sample sizes for some were much smaller than to begin with.

Ipsos MORI led the programme of online qualitative research with senior public service leaders on behalf of the NLC. This included a programme of depth interviews, focus groups, workshops and six case studies exploring collaboration. Throughout each qualitative strand, leaders were recruited from across the sectors and regions involved in the NLC’s network. Leaders were asked if they were interested in participating in qualitative research through voluntary self-selection in the quantitative survey. From the leaders who volunteered, a selection was invited to participate in different strands of the research to achieve a fair balance of sectors, regions and genders. Leaders were able to take part in multiple activities, for example attending both an interview and a focus group.

1.2 Service delivery during COVID-19

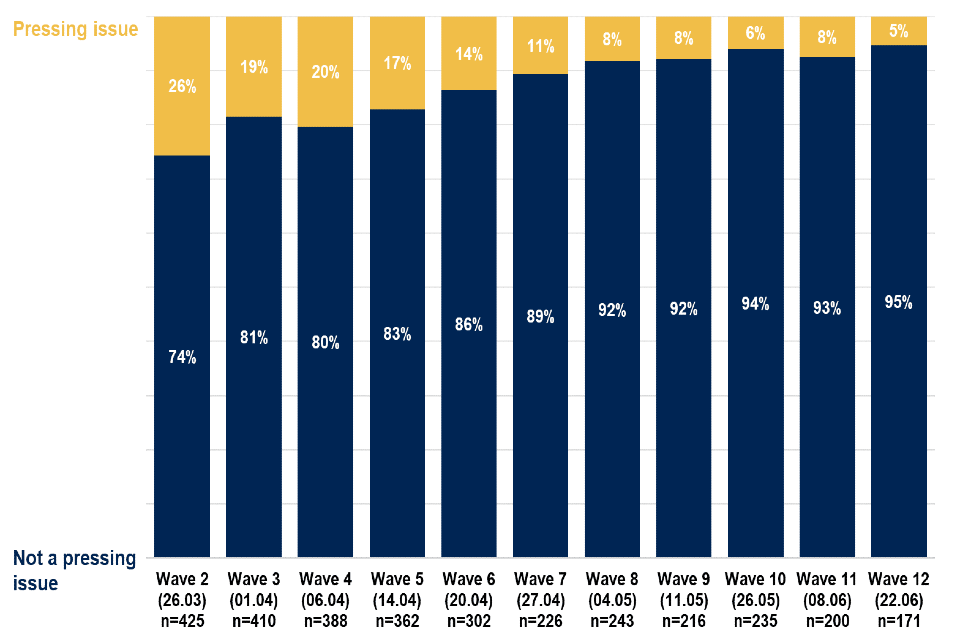

From the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the most significant challenge facing leaders was the need to quickly transform services to continue to meet citizens’ needs. Transitioning services online, supporting teams to adjust to remote working and making locations COVID-secure, often had to happen at the same time as maintaining services, without a chance for planning or consultation. These challenges were immediate in March 2020 and tended to ease as organisations adapted to new circumstances. This was reflected in the NLC’s survey findings: in Wave 2 in March, one in four (26%) leaders reported “maintaining critical services” as a pressing issue, whereas by Wave 12 in late June this had dropped to just 5%. Examples of adaptions made by organisations included:

- Primary care organisations rolled out digital consultations (“e-consulting”) to prevent patients from exposing themselves to COVID-19 unnecessarily;

- The prison service enabled prisoners to conduct “virtual visits” with their friends and relatives using tablets and phones provided to them;

- Organisations within the education sector moved learning resources and teaching online, which had previously been considered too costly. Across sectors more generally, organisations started hosting training and external events online.

Organisations overcame these challenges to service delivery through:

- Staff resilience and their willingness to work hard and quickly. Teams pulled together and worked longer hours to ensure services were able to adapt. Individuals, including leaders, often went beyond the traditional remit of their role and at times assumed additional responsibilities.

- Motivation to ensure services could continue. Staff recognised that the pandemic posed an existential threat to parts of their service, which created a shared purpose bringing people together. In some sectors, organisations also worked to limit the pressure on the NHS, motivated by playing a part in their region’s response to the crisis.

- Collaboration with public, private and voluntary sectors. Organisations worked together to support each other in the form of expertise, supplies and resourcing. This was vital to the response given the scale of change required, reduced workforce as a result of COVID-19, and the level of demand for critical provisions such as PPE supplies.

- Creative thinking and flexible processes. Adapting service delivery at pace required leaders to think creatively about how to redesign their approach, testing new ideas and accepting that not all policies would work perfectly first time. This required greater flexibility in decision-making, with organisations reducing standard processes to allow for greater innovation.

On the whole, leaders were immensely proud of how their teams adapted to remote working. They acknowledged the benefits of a better work-life balance and reducing their companies carbon footprint. However, they also recognised that capabilities to work from home were not consistent across their work force, with parents, carers and those in shared accommodation experiencing additional pressures. Digital poverty also posed a threat, particularly in the education sector where not everyone had the technology for remote learning. These challenges required tailored support including providing staff and service users with the necessary technology where possible, but this was not always fully overcome.

1.3 Collaboration across public services

Increased collaboration between public services was consistently highlighted as one of the most positive experiences of the pandemic. Leaders widely described how previous barriers to collaboration including misaligned structures, competing priorities or ineffective communication, fell away as organisations came together to respond to COVID-19.

In the NLC’s survey, the vast majority of leaders consistently reported that collaboration was better than usual within the workplace (ranging from 65%-82% across waves), with other organisations in their sector (64%-73%), and in the local area (63%-74%). This varied between sectors, with health care and local government reporting the biggest overall improvements in all three areas from late April to June 2020. Examples of organisations collaborating during the pandemic included:

- Private sector businesses procuring and producing PPE for health and care workers;

- Local authorities, private landlords and local businesses renting out venues to HM Courts and Tribunals for use as temporary courts;

- Fire services diversifying their remit to support other organisations including delivering food parcels to self-isolating residents, managing the distribution of PPE, supporting local logistics operations and delivering laptops to school children;

- Fire stations offering their premises as sites for blood and plasma donation;

- Local authorities and the army working with NHS organisations to establish and man COVID-19 testing sites;

- Police services assisting NHS organisations with the logistics of increasing bed capacity and the establishment of additional mortuaries.

Increased collaboration was enabled by:

- Pre-existing emergency response structures. Pre-existing structures such as Local Resilience Forums (LRFs) and Strategic Coordinating Groups (SCGs) kicked into action at the beginning of the pandemic, meeting on an almost daily basis as opposed to typically a couple of times a year in usual circumstances. These forums created spaces for leaders to communicate more regularly, identify local needs, share resources and build trust without having to establish a new body to co-ordinate the response.

- A shared purpose. The scale, severity and sustained nature of the crisis fostered a sense of a shared purpose as organisations worked together to support their region’s response. Many organisations went beyond their traditional remit to support other services in their area, with the pandemic response taking priority over individual, organisational aims. There was greater willingness to provide support, with less concern about the longer-term implications on organisations.

- A focus on outcomes as opposed to processes. The need to make fast decisions meant organisations shared resources, expertise and data more freely without always going through the formal processes required in business as usual. This created a spirit of openness and flexibility to achieve the outcomes needed, reducing bureaucratic barriers that can limit collaborative working.

- Additional funding enabled collaboration as there was less concern about which partner was financially responsible for decisions. At times, funding was pooled between organisations further reducing competition and enabling joint decisions.

- Building and maintaining new relationships. Public services relied on each other throughout the pandemic. This created a greater willingness to build relationships and learn more about what each organisation does and how they can support each other in the future. Increased remote working has also broken-down physical barriers, expanding leaders’ networks and enabling individuals to work together across greater distances. Leaders felt that to maintain these relationships they needed to continue open and frequent communication to build mutual understanding and trust.

1.4 Decision making at a time of crisis

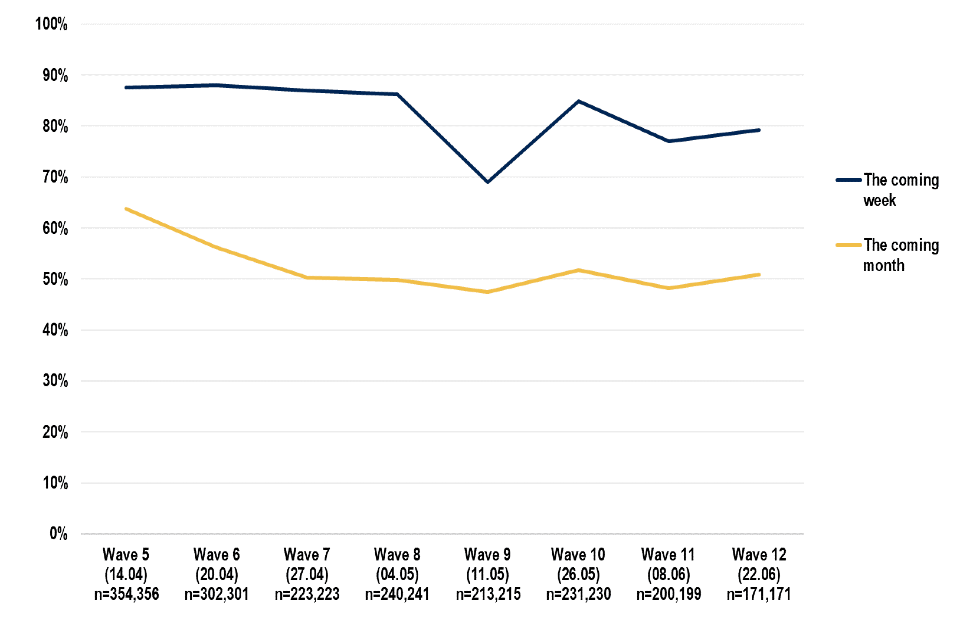

The significant uncertainty brought by the pandemic was a key challenge to decision-making for leaders. They had to make decisions impacting their organisation and the public, without knowing how the crisis would develop or how long it would last. Added to this, increased collaboration with other organisations meant at times they were working with new people to deliver large scale projects at pace. The uncertainty was borne out in the NLC’s survey findings, as only around half of leaders (ranging from 47% to 64% across eight waves) consistently agreed that they had the tools and information they needed to plan effectively for the coming month.

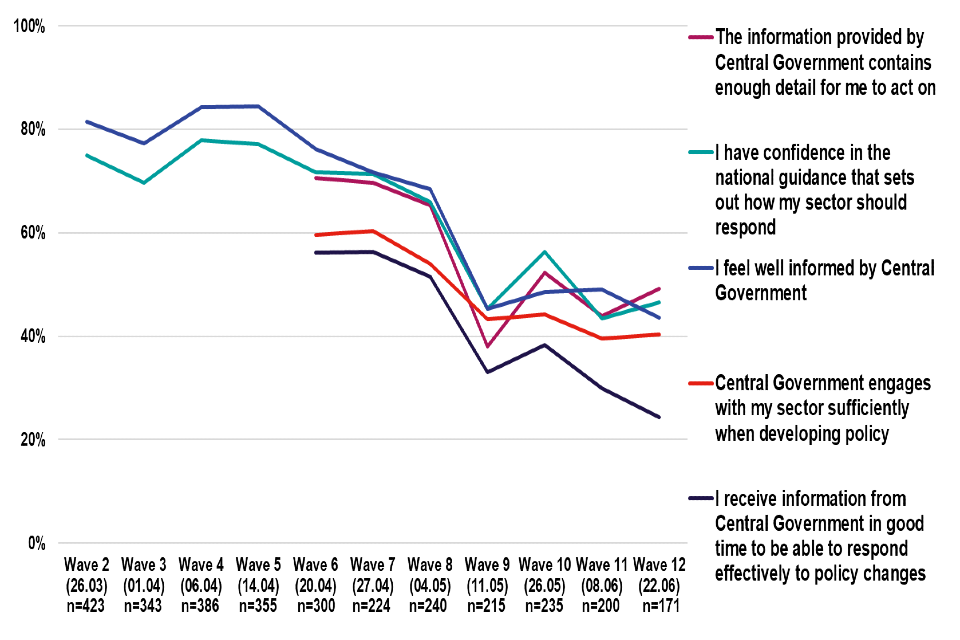

Uncertainty was reported to be exacerbated by inadequate business continuity plans and poor communication from central government, which at times leaders felt was inconsistent, vague and given without prior consultation. NLC survey results show that at the start of the first national lockdown, the majority of public service leaders were positive about government communications and reported confidence in national guidance. However, over the following three months opinions became increasingly negative.

By the Autumn, there was growing scrutiny of decisions leaders had made during the pandemic. This focused both on looking back on how leaders had handled the first wave of the crisis, and scrutiny of what they planned to do next. There was a fear that leaders could be blamed for what had gone wrong and face an inquiry before they were given time to recover from the crisis.

Despite the challenges, some leaders described embracing the uncertainty of the pandemic and found the challenge invigorating as they were making fast-paced decisions that mattered. When collaborating with other leaders, uncertainty also fostered a sense of camaraderie as they tried to interpret information together. These challenges were overcome by:

- Establishing formal structures. Organisations established internal COVID-19 response teams, often operating on a tiered structure with “gold” and “silver” groups. This allowed them to bring together expertise within their organisation and assign groups different areas of oversight beyond the crisis, to ensure their senior team’s attention was not fully consumed by the pandemic response.

- Delegating decisions to other senior team members. Leaders realised it was not possible for them to make every decision as they did not have the time to stay fully informed of developments within their wider organisation or region. Delegating decisions allowed leaders to maintain strategic control and focus on relationships with partners, while further building trust with their staff.

- Organisations increasing their risk appetite. Leaders acknowledged that the need to find rapid and workable solutions required a relaxation in certain processes and oversight, allowing teams to take greater risks or try different approaches without certainty of success. This resulted in the streamlining of governance processes and promoted collaboration by sharing responsibilities across organisational boundaries.

1.5 A focus on wellbeing

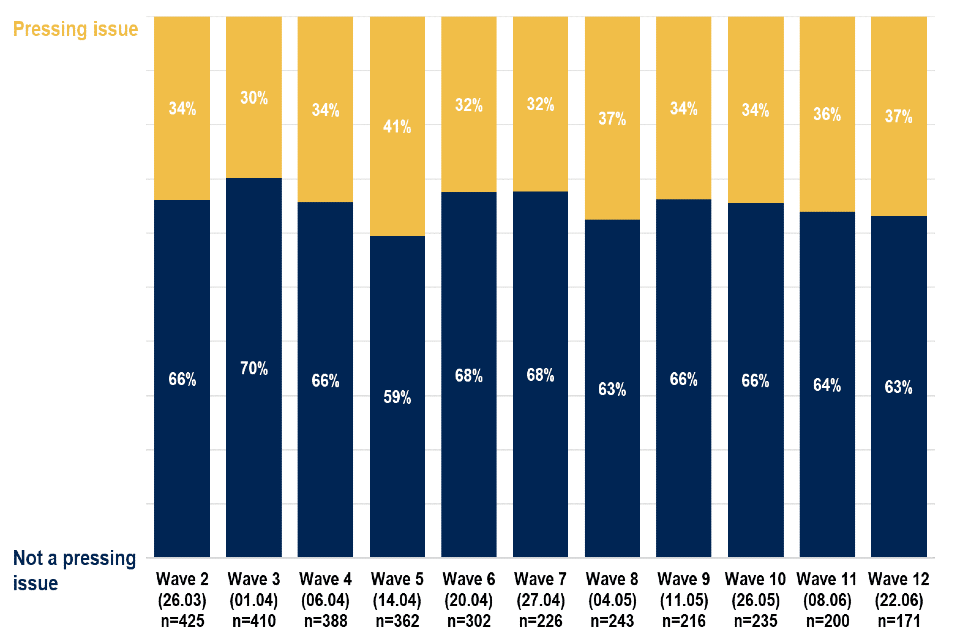

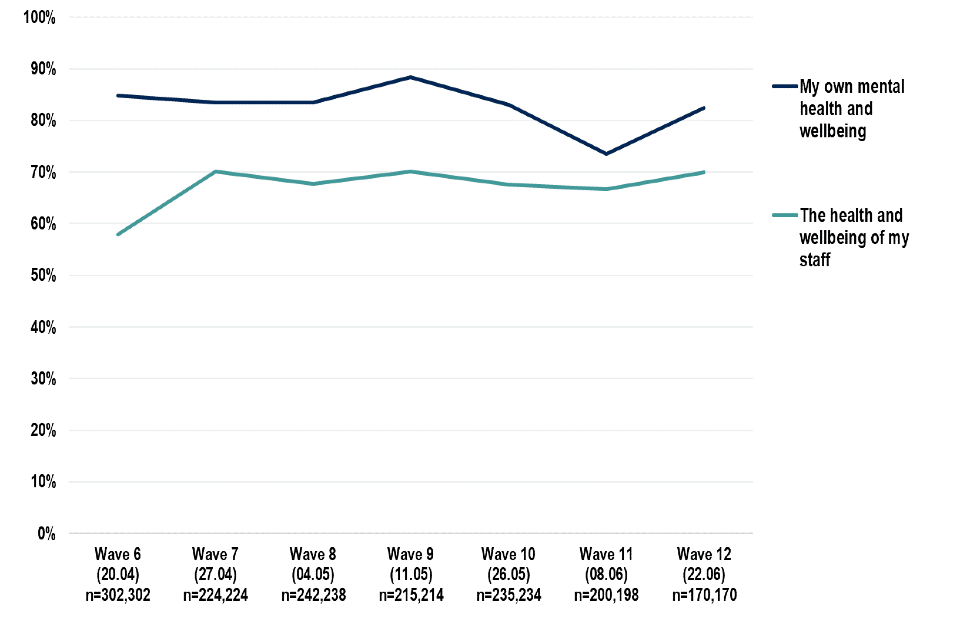

Maintaining their own wellbeing has been a challenge for leaders during the pandemic. Especially during the early stages, leaders were working long hours at their computer screens with very few breaks, attending back-to-back virtual meetings and dealing with an increased workload. Many were also affected by the pandemic in their personal lives. At the same time, supporting the wellbeing of their staff has also been an area of increased focus. Leaders felt that after the initial adrenaline waned, work fatigue combined with prolonged periods of lockdown posed the threat of burnout among their teams. Throughout the NLC’s survey around a third of leaders consistently identified staff wellbeing and resilience as a pressing issue. Unlike some of the other challenges reported by leaders, this remained consistent across Waves and sectors.

Leaders acknowledged they have not been able to fully look after their wellbeing, and voiced regret for not doing more for their teams during the early stages of the pandemic. However, as the crisis progressed, they have addressed wellbeing through:

- Being honest in asking people how they are and prioritising wellbeing in the workplace. Remote working has blurred the distinction between the personal and professional, which has made it easier for leaders to speak to staff about their own wellbeing. This has also facilitated relationship building with other public service leaders, as they have been able to create private and informal forums to discuss their wellbeing and shared challenges. There has also been a recognition of the importance of wellbeing for service delivery, with leaders seeing this as an area they want to prioritise going forward.

- Increasing their communication with staff. Leaders have established regular webinars and newsletters to provide updates to their staff and publicly acknowledge the length their teams have gone to maintain services during the crisis. They explained the balance of remaining calm and collected in front of teams, while also being honest about their own experiences.

- Taking a facilitative approach. Leaders have highlighted the need to consult their staff more in finding solutions to problems, rather than imposing policies without discussion. This became particularly evident following discussions around the Black Lives Matter movement and wider health inequalities, as they wanted to strive to promote equality. They described running internal surveys or large-scale consultations within their organisation and setting up the means for staff to provide anonymous feedback and suggestions.

- Creating a unified message that recognised the contribution of the whole workforce. Leaders recognised that individuals and teams were experiencing the pandemic differently, particularly where some might have been working remotely and others on the frontline. They stressed the importance of using regular communications to promote a unified message and the idea that everyone was pulling together to support one another.

1.6 Going forward

Despite the challenging circumstances of the last year, leaders consistently expressed a desire for learning from the pandemic to be taken forward and applied to how public services are delivered in the future. The pandemic provided an opportunity to rapidly experiment with different ways of working including increased collaboration, digital transformation and greater engagement with their workforce which leaders argued had brought benefits to service delivery. However, they also questioned the feasibility of continuing certain changes without the willingness and shared sense of purpose brought by the pandemic (both of which have already started to diminish) and wanted to strike a new balance when it came to areas such as risk taking. Although leaders were not always sure how changes could be sustained after the pandemic, they were keen to work with others to adapt public services during and beyond the pandemic recovery.

Future service delivery

- The move to digital ways of working showed what was possible in terms of how quickly services can be adapted and the wide-ranging benefits to both service users and organisations that being more digitally focused offers. Leaders wanted to hold onto new ways of working, increasing convenience and choice for citizens as well as providing efficiencies in terms of service delivery.

- A number of leaders described exploring the options for reducing their estate, believing teams are unlikely to return to the office full-time. There was a desire to increase the flexibility of remote working, giving staff the option to decide where and when they work.

- Leaders saw future services taking a blended approach to ensure accessibility to those without internet access or who would prefer to attend services face-to-face. Reflecting discussions around the Black Lives Matter movement and wider health inequalities, leaders wanted to look further at who can access services and do more to put equality at the heart of what they do.

Maintaining collaboration

- Although there was some scepticism about maintaining the level of collaboration seen during the pandemic, leaders aspired to continue working with other public services within their region. This was seen as a vital part of the COVID-19 recovery and critical for improving services.

- Leaders wanted to create or maintain collaborative structures and relationships, both within their organisations and beyond, recognising the importance of having established ways of working to a rapid crisis response. Even though these relationships take time and resources to nurture, leaders saw this as a critical investment in future preparedness.

- Recognising the shared purpose created by COVID-19, leaders wanted to develop a common goal for their local area that could act as a way of unifying organisations behind the needs of the community after the pandemic. This should be specific to their community and have a clear deadline. For example, if they have a particular issue around poverty or working towards an environmental goal. Without a shared set of values or aims, leaders worried that organisational priorities and demands would take preference over collaborative ones.

- To facilitate a shared purpose, leaders suggested that pooled funding could be made available so no one organisation was responsible for financing a project, which can often lead to tensions.

Decision making

- The increase in innovation and risk taking seen during the pandemic was also something leaders wanted to hold on to. Balancing this against the need for accountability and proper scrutiny of decisions, they wanted to find a way of encouraging creativity and giving staff the opportunity to make mistakes without unwarranted fear about the consequences.

- Getting this balance right was seen as a challenge for leaders. They wanted to hold on to a more facilitative style developed during the pandemic, where they practiced greater delegation and involved staff and service users in decision making more frequently. Leaders saw their role as bringing others together to draw on wider expertise rather than making decisions in isolation.

- Alongside this, leaders wanted to promote more transparent decision-making processes where they could be honest and admit mistakes without facing intense scrutiny. They recognised they would still be ultimately responsible but wanted to work with others to find solutions to problems.

- They also wanted to reduce the number of bureaucratic processes that can delay decision making, whether that is reducing the length of forms or number of planning stages within projects. It was suggested that where possible, processes could be standardised across services to enable collaboration. Again, achieving the right balance was seen as important. Leaders acknowledged some decisions required extensive consultation but felt this could be decided at the start of a project.

- There was a desire for greater collaboration and consultation from central government. Although leaders recognised that it may not be possible to disclose confidential information, they wanted local decision makers to be involved in policy discussions at an earlier stage. This was seen as a way of reducing the frustrations of local leaders, providing more time to plan for emerging policies and improving the approach by ensuring it could work at a local level.

- Similarly, leaders aspired to greater local decision making going forward. The pandemic highlighted how local services could work together to achieve outcomes for their community and the benefits of local knowledge for solving problems.

Wellbeing

- Prioritising wellbeing as part of an organisation’s culture was widely recognised as a long-term impact from the pandemic. Both staff and leaders’ own wellbeing came to the fore, with leaders recognising the importance of looking after each other to deliver services effectively.

- There was a commitment to continuing more open forms of communication and empathetic leadership styles, involving staff more widely in decisions and creating spaces for conversations about topics affecting different groups. They wanted to build upon conversations around mental health which have been so prominent during the crisis.

- Leaders wanted to maintain the honesty and humanity shared with their teams and continue to embed kindness and positivity into their values. They sought to put their staff’s wellbeing at the heart of any decision making around the future of working, conscious that they did not want to force anybody to either return to the office or continue to work from home. It was seen as important that leaders continue a consultative approach and let people decide what is best for themselves.

2. Methodology

The National Leadership Centre (NLC) was established in October 2018 to help leaders work together to improve public services. The NLC’s core audience are the most senior leaders of public services in England, who form the basis of the NLC network.

On 18 March 2020, the Cabinet Secretary redeployed the NLC to support the Government’s response to COVID-19 by acting as the conduit between Central Government and the NLC network. The NLC gathered information on the health status of public service leaders, workforce availability in their organisations, and the most pressing challenges they were facing via a regular survey. This information was shared with the Cabinet Secretary, reported to COBR, and circulated to key government personnel including Permanent Secretaries of all Whitehall departments and selected Ministerial Private Offices and Special Advisers.

2.1 Aims of the research

As the COVID-19 pandemic started, the NLC launched a quantitative survey which ran from March to June 2020. The research aimed to:

- Provide public service leaders with the opportunity to engage directly with the centre of government.

- Provide timely insights to the centre of government about the current status of, and issues facing, public service organisations across the UK during COVID-19.

- Monitor change in issues, needs, attitudes and behaviour over time, and how these differed across sectors.

The NLC commissioned Ipsos MORI to conduct a separate strand of qualitative research with leaders from their network, which ran from July 2020 to March 2021. The aims of this research were to:

- Deliver in-depth insights into the challenges, opportunities and experiences of public service leaders, their organisation and their workforce

- Provide additional context to the findings from the survey

- Consider both the practical and emotional impact of the pandemic, and the associated implications

- Explore current experiences of leadership and collaboration both within the organisation, the sector and across the system

This report brings together findings from both stands of research.

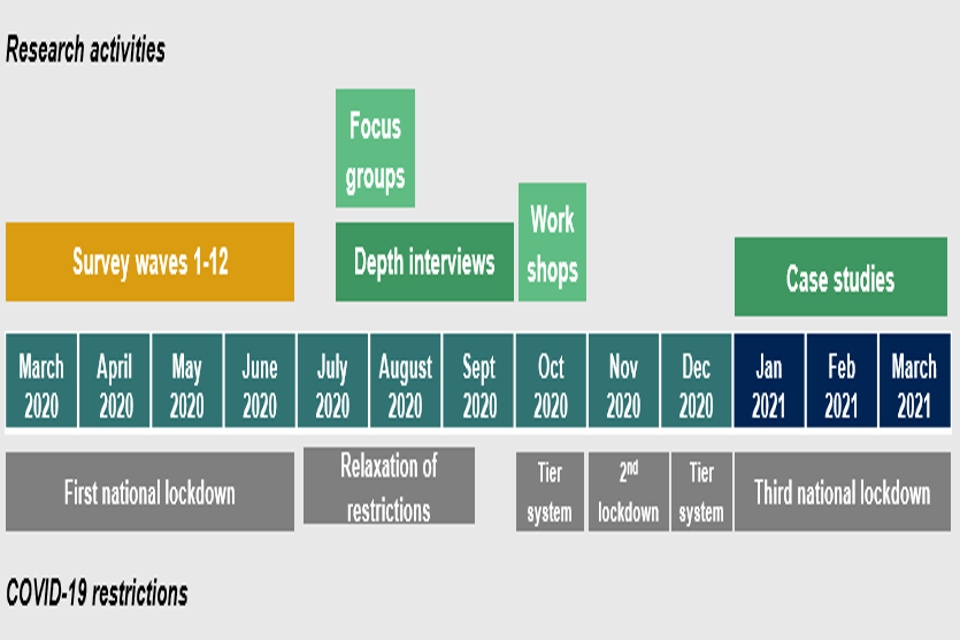

Timings of each research activity are shown below in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1: Timeline of research activities

Timeline of research activities

Alongside this synthesis report, the NLC has published the following reports on Gov.uk:

- Analysis of the quantitative survey findings

- Detailed descriptions of the six case studies exploring collaboration in public services

- A summary of the challenges and enablers to collaboration identified in the case studies

2.2 Quantitative research conducted by the NLC

The COVID-19 Response Public Service Leaders Survey ran for 12 Waves over 15 weeks, between 20 March and 22 June 2020. The questionnaire was iterated over the 15 weeks to reflect responses from previous waves and changes in the wider context, with questions being added and removed as appropriate. Annexes including all the questions asked across survey waves, data tables (overall and for each sector) and results from the significance testing are available on Gov.uk.

The first nine survey Waves ran weekly (20 March to 11 May 2020), with the remaining three Waves running fortnightly (26 May to 22 June 2020). All members of the NLC Network were eligible to participate in the survey. The NLC network is open to leaders of public services in England who meet the following criteria:

- Significant funding of the organisation comes from public finances;

- The public has significant ownership of the organisation;

- The organisation’s budget or spending is in excess of £10 million per annum; and

- Sector specific criteria usually related to role and/or organisation type or size.

The NLC had contact details for 676 senior public service leaders when Wave 1 was launched in March 2020. There was then a concerted effort to improve the data held about this stakeholder group, and an additional 208 leaders’ contact details were collected. Additionally, from Wave 2, the survey was also sent to 155 senior leaders of organisations within the Public Service Leadership Group (PSLG) that met similar criteria to those in the NLC network, including:

- Devolved administrations;

- Local Authorities and Emergency Services within the devolved nations;

- Organisations in the Third Sector, Charity Sector or Civil Society that deliver public services in the UK, each with a turnover of over £100 million.

As a result, from mid-April onwards, the survey was sent to 1,039 senior public service leaders, 94% of the 1,104 eligible NLC and PSLG network members. In total, 3,591 responses were completed, with an average of 299 responses per survey and an average response rate of 27%.

Table 2.1: Response rate by survey wave

| Survey Wave | 1(20/03) | 2(26/03) | 3(01/04) | 4(06/04) | 5(14/04) | 6(20/04) | 7(27/04) | 8(04/05) | 9(11/05) | 10(26/05) | 11(08/06) | 12(22/06) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of responses | 413 | 425 | 410 | 388 | 362 | 302 | 226 | 243 | 216 | 235 | 200 | 171 |

| Response rate | 37% | 38% | 37% | 35% | 33% | 27% | 20% | 22% | 20% | 21% | 18% | 15% |

Sample profile

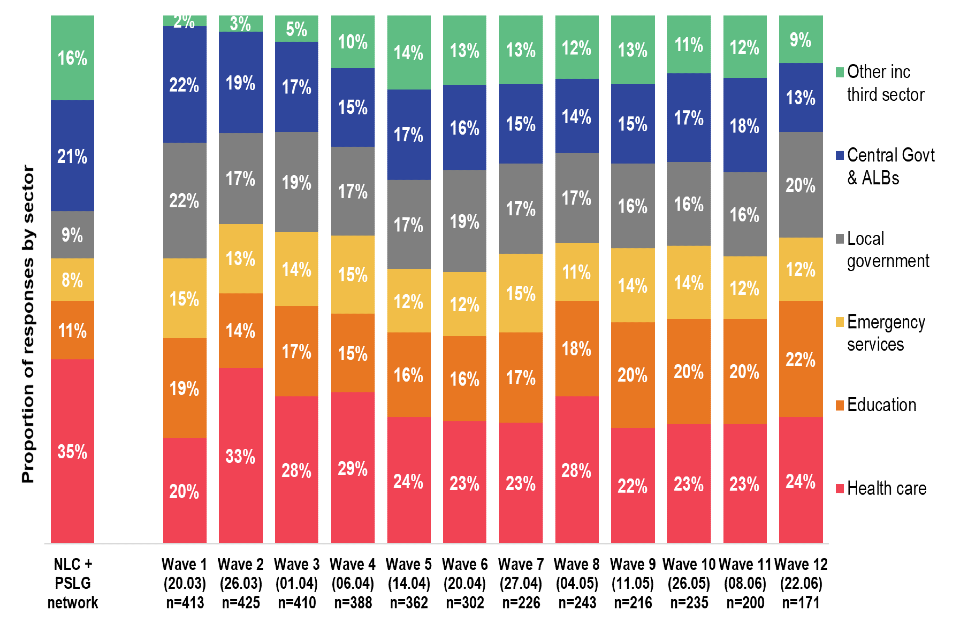

The distribution of respondents by sector remained relatively stable throughout the survey period. The proportion of respondents from the health care sector consistently made up the largest proportion of the survey sample but remained under-represented overall, whereas the Local Government and Education sectors were consistently over-represented.

Figure 1.2: Proportion of responses by sector, Waves 1-12

Proportion of responses by sector

Questionnaire design

Questionnaire design was iterated over the 15-week period to reflect responses from previous waves and changes in the wider context, with questions added and removed as appropriate. An overview of the broad topic areas covered are listed below:

- Leaders’ health and wellbeing

- Staff health and wellbeing

- Pressing issues facing the organisation

- Workforce availability

- Operational effectiveness

- Government communications and engagement activity

- Government measures to manage COVID-19

- Support required from government

Quantitative data analysis

The NLC conducted analysis of the quantitative data using significance testing to determine where there were statistically significant differences between the responses from different sectors and/or survey waves. Kruskal-Wallis and Z-tests were conducted to identify overall significantly different distributions in responses, and post-hoc pairwise comparisons were conducted to determine specific differences between sectors or survey Waves.

Where statistical significance has been referenced, this has been taken at an alpha level of 0.05, which indicates that the probability of the outcome occurring due to chance and chance alone is less than 5%. For full details of significance test results, please see the accompanying survey report and annex. Any differences that are not explicitly described as statistically significant should be assumed to be statistically non-significant.

Where questions asked respondents to indicate the extent to which they agreed with a series of statements, ‘Not Applicable’ responses have typically been removed from the analysis for consistency and to ensure findings were based on valid responses only. The volume of respondents who selected this category was consistently small.

Limitations of the quantitative survey

- Sampling: Only public service leaders who the NLC had an email address for were invited to participate in the survey. As the NLC gathered more details, the sampling frame expanded week-on-week. It was a self-selecting sample, meaning leaders had to engage with the survey invite and choose to participate.

- Response rate: As tends to happen with multi-wave surveys, the response rate declined over time. By Wave 12, 171 leaders responded compared to 425 in Wave 2. This makes it more difficult to complete sector specific analysis in later waves, when the sample sizes for some sectors were much smaller than in the earlier waves. It also impacts the extent to which changes over time can be described as significant.

- Trends: Questionnaire development was an iterative process. Not all sectors were consistently asked the same questions, which affects the way trends can be presented. This is particularly notable for the question asking about the most pressing issues facing leaders. Each issue was not consistently shown to every sector as leaders were selecting from a list which was amended for each wave as additional issues were raised in the open text box comments or removed if they were consistently not identified as pressing for a sector.

2.3 Qualitative research conducted by Ipsos MORI

From July 2020 to March 2021, Ipsos MORI led a programme of online qualitative research with senior public service leaders on behalf of the NLC. This included a programme of depth interviews, focus groups, workshops and six case studies exploring collaboration.

| Activity | Total no. of participants | Duration |

|---|---|---|

| Depth interviews (27) | 27 | July - September 2020 |

| Focus groups (3) | 11 | July - August 2020 |

| Workshops (2) | 23 | October 2020 |

| Case studies exploring collaboration (6) | 37 | January - March 2021 |

| TOTAL | 98 |

Throughout each strand, leaders were recruited from across the sectors and regions involved in the NLC’s network. Leaders were asked if they were interested in participating in qualitative research through voluntary self-selection in the quantitative survey. From the leaders who volunteered, a selection was invited to participate in different strands of the research to achieve a fair balance of sectors, regions and genders. Leaders were able to take part in multiple activities, for example attending both an interview and a focus group. Case studies were either identified by the NLC from their network or selected from earlier interviews carried out by Ipsos MORI as part of the wider research project. They involved an initial interview with a leader who connected the research team with wider public service professionals involved in the collaboration. Subsequent interviews explored the example from different perspectives, building a detailed picture of what took place.

Across the different strands of qualitative research, the 98 leaders split across sectors:

| Sector | Number of leaders |

|---|---|

| Health Care | 16 |

| Education | 15 |

| Central Government & Arm’s Length Bodies (ALBs) | 21 |

| Local Government | 19 |

| Emergency Services | 18 |

| Other incl. third sector | 7 |

| Private sector | 2 |

| TOTAL | 98 |

The aim for recruitment to the qualitative research was to ensure each sector was well represented, as opposed to representing the profile of the NLC’s database. This was important for ensuring the research reflected the range of experiences across sectors. Some sectors are better represented than others due to the selection of case studies, which included two interviews from the private sector.

Depth interviews

The report draws upon findings from 27 depth interviews. These interviews were designed to explore leaders’ experiences during the pandemic, providing a chance to share learning from the crisis. It was intended to capture good practice and understand the challenges leaders faced during this period. The research broadly covered the two themes of leadership and collaboration. Interviews were conducted between July to September 2020 and spread across sectors and regions:

| Sector | Number of leaders |

|---|---|

| Health Care | 5 |

| Education | 6 |

| Central Government & ALBs | 4 |

| Local Government | 5 |

| Emergency Services | 4 |

| Other incl. third sector | 3 |

| Region | Number of leaders |

|---|---|

| East Midlands | 2 |

| East of England | 3 |

| London | 4 |

| Multiple regions | 2 |

| North West | 1 |

| North East | 1 |

| South East | 3 |

| South West | 6 |

| West Midlands | 2 |

| Yorkshire and the Humber | 3 |

Online focus groups

Ipsos MORI also conducted three online focus groups. Two of the groups explored learning from COVID-19 and one focused on collaboration between public services. The table below includes the dates and attendance for these groups.

| Theme | Date | Number of leaders |

|---|---|---|

| Learning from COVID-19 | Thursday 30 July 2020 6-7:30pm | 6 |

| Collaboration | Tuesday 4 August 2020 8-9:30am | 2 |

| Learning from COVID-19 | Wednesday 5 August 2020 8-9:30am | 4 |

The groups brought together 11 leaders split across sectors (one leader attended two sessions on the different topics):

| Sector | Number of leaders |

|---|---|

| Health Care | 2 |

| Education | 2 |

| Central Government & ALBs | 2 |

| Local Government | 2 |

| Emergency Services | 3 |

Online workshop

Two online workshops attended by 23 public service leaders were held in October 2020. Sessions involved the NLC sharing interim research findings with leaders, followed by small group discussions focused on how the findings might impact any return to business as usual. Conversations revolved around the themes of decision making, people and wellbeing, and collaboration. These themes had been identified from the previous two strands of research as areas where leaders wanted to carry learnings forward. The table below includes the dates and attendance for these workshops.

| Date | Number of leaders |

|---|---|

| Wednesday 14 October 2020, 5:30-7:30pm | 10 |

| Friday 16 October 2020, 8:00-10:00am | 13 |

The workshops brought together 23 leaders split across sectors:

| Sector | Number of leaders |

|---|---|

| Health Care | 3 |

| Education | 7 |

| Central Government & ALBs | 3 |

| Local Government | 2 |

| Emergency Services | 4 |

| Other incl. third sector | 4 |

Case studies focusing on collaboration in public services

From January-March 2021, Ipsos MORI developed six case studies exploring collaboration between public services. These did not solely focus on experiences of the pandemic, so some examples are drawn on more than others in this report. More information on the individual case studies can be found in a separate report published on Gov.uk.

Across the case studies, Ipsos MORI interviewed 37 participants. The NLC identified examples of collaboration from their network and interviews with leaders as part of the wider research project. Following an initial call to explain the research and agree their involvement, leaders took part in an interview with Ipsos MORI to explore the situation in more detail. They also identified others involved in the example, who were subsequently invited to take part in an interview. As such, recruitment took place through a ‘snowball’ approach, identifying individuals who could help build our understanding of what happened.

| Sector | Number of leaders |

|---|---|

| East Ayrshire Council, Vibrant Communities | 6 |

| Her Majesty’s Prison and Probation Service, Homelessness Prevention Taskforces | 8 |

| Responding to COVID-19 in Northumbria | 7 |

| Her Majesty’s Courts and Tribunal Service, Nightingale Courts | 5 |

| The Stepping Up Leadership Programme, Bristol | 6 |

| Kent Fire and Rescue, Responding to COVID-19 | 5 |

| TOTAL | 37 |

These 37 leaders split across sectors:

| Sector | Number of leaders |

|---|---|

| Health Care | 6 |

| Central Government & ALBs | 12 |

| Local Government | 10 |

| Emergency Services | 7 |

| Private sector | 2 |

Qualitative data analysis

Throughout each strand of research, raw qualitative data was captured in the form of recordings and observational notes taken by researchers. During and following fieldwork, Ipsos MORI and the NLC conducted regular analysis sessions together to identify emerging insights and common themes, helping familiarise the team with the wide-ranging dataset. These sessions formed the starting point of constructing a thematic “code frame” to apply to the data from across fieldwork. This thematic code frame was structured around the discussion guides used during the research. Once the code frame was complete, it was analysed to look for patterns by sector and region. Each strand of research had a separate code frame.

Ipsos MORI delivered an interim report in August 2020 when they had completed the majority of the depth interviews and all of the online focus groups. Findings from this interim report informed the discussion guide for the online workshops which were held in October 2020.

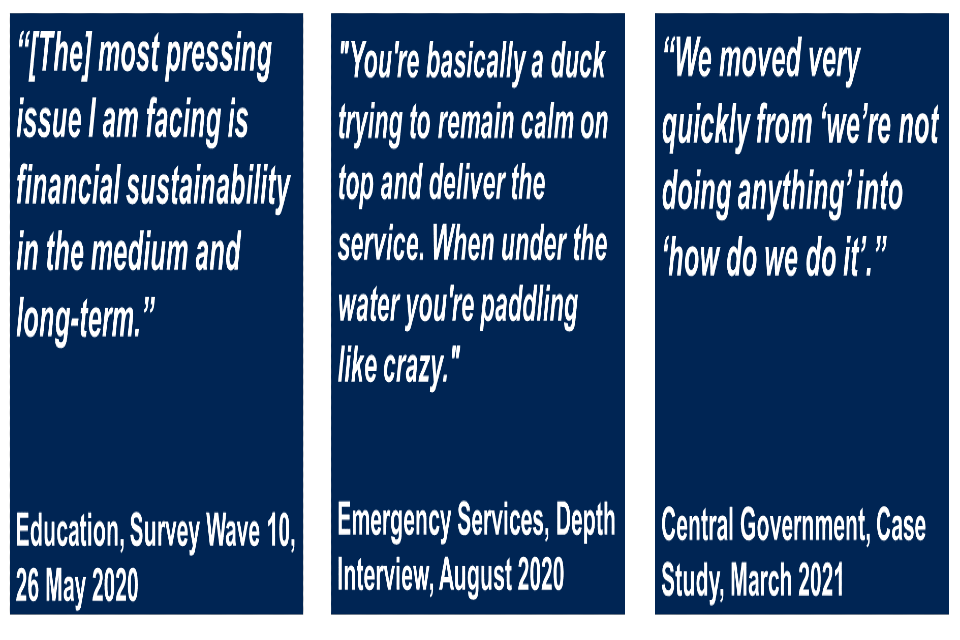

Throughout the report we have used verbatim comments from leaders, attributing these to the relevant sector, research activity and date.

Limitations of the qualitative research

- Sampling: Leaders were asked to express interest in participating in qualitative research during later stages of the quantitative survey when the response rate had already fallen. This means that the leaders interviewed during the qualitative research had the time to participate in research and were keen to share their experiences. These experiences might differ compared to someone who was unable to participate.

- Trends: Where possible we have explored how attitudes and behaviours have changed over the course of the research from July 2020 to March 2021. However, the project did not follow a longitudinal design as we have not returned to the same leaders interviewed at each stage. This means reflections on developments during the pandemic should be considered indicative.

- Snowballing: Recruitment for the case studies adopted a snowballing approach where the leader initially contacted suggested further people to interview. As we were only speaking to individuals suggested by leaders, their views may not necessarily reflect those of everyone who was involved in each case study.

3. Service delivery during COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic presented immediate challenges for service delivery across the public sector. Face-to-face delivery was prohibited for all but essential services, and those which remained open had to adapt to make venues COVID-secure. Leaders worked hard both to transition services online and protect citizens and staff who were required to continue delivering in-person services.

This section brings together leaders’ experiences of delivering services during the pandemic. It explores how leaders adapted in response to COVID-19 restrictions, including the instruction to stay at home and social distancing measures which led many services to move online.

Responses

The challenge to maintain critical services

The NLC’s quantitative survey tracked the most pressing issues facing leaders and their organisations from the first national lockdown in March 2020 through to June 2020 as restrictions were relaxed.

The initial challenges selected as most pressing by leaders focused on continuing service delivery, including ensuring provisions such as Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) supplies were in place to protect staff and service users (selected by 70% in Wave 2) and maintaining critical services (selected by 26% in Wave 2). Health care, emergency services, and local government were predominantly focused on securing supplies of PPE, medicines, food and other equipment, and on facilitating the adoption of social distancing and shielding measures. Leaders in education and central government put a greater emphasis on maintaining and adapting delivery of their core services.

Over time, as services successfully adapted, these early concerns dissipated and the focus turned to the longer-term implications of lockdown such as the impact on budgets and planning for recovery, including resuming business as usual. As shown in Figure 2.1, “maintaining critical services” was most pressing up to Wave 5, when around one in five leaders consistently referenced it (between 17%-26%). This compares to later waves when it was mentioned by closer to one in twenty (between 5%-8%, Waves 8 to 12), as leaders became accustomed to new ways of working.

Figure 1.3: Percentage reporting “maintaining critical services” as one of their three most pressing issues across all sectors, Waves 2-12.

Percentage reporting “maintaining critical services” as one of their three most pressing issues across all sectors, Waves 2-12.

Delivering public services during COVID-19

Transitioning services online

The most significant challenge faced by leaders was to transition their services online, along with moving all or parts of their workforce to remote working. This included leaders themselves, many of whom have worked from home full or part-time over the last year. Examples include:

- Primary care organisations rolled out digital GP consultations (“e-consulting”) to prevent patients from exposing themselves to COVID-19 unnecessarily, which interviewees reported has also improved efficiency in the NHS. This had “been in discussion for years” but the crisis provided an impetus for change.

- The prison service enabled prisoners to conduct “virtual visits” with their friends and relatives by using tablets and phones provided to them.

- Organisations within the education sector moved learning resources and teaching online, which had previously been considered too costly. Across sectors more generally, organisations started hosting staff training and external events online.

On the whole, leaders spoke positively about how their teams were able to overcome challenges by bringing innovative solutions and adapting to delivering services remotely. They were particularly impressed with the speed their organisation managed to work at, describing how it felt like their teams were running on adrenaline. There was an atmosphere of camaraderie as a shared sense of purpose pulled teams together, focused on solving problems and maintaining a positive attitude despite the uncertain circumstances. Many individuals, both leaders and their staff, went beyond the traditional requirements of their role, working longer hours and taking on additional responsibilities to adapt services so they could continue to meet the needs of users.

“There have been some fantastic learnings in terms of better ways of delivering our services, more efficient ways of delivering our services. And for many of our staff, finding ways of allowing roles to be defined and delivered in more flexible ways.” - Central Government, Depth Interview, August 2020

While challenging, this also provided an opportunity for leaders to see how services could be transformed in the future, both in terms of service delivery and the management of their workforce. Many described how they implemented digital transformation programmes which had been talked about for many years within days during the early stages of the pandemic, including those mentioned above. For some initiatives, where they improved efficiencies there was little appetite to return to pre-pandemic approaches, with leaders seeing the benefits for both service users and staff. For example, a leader described how by moving their training courses online, they were able to pool all their development materials onto one webpage and make them accessible to participants, who could interact with each other and share their own resources.

“It is good to see how we can work together and what we can achieve when we do. Seeing things start one evening and having them put in place the next day. It can be very rewarding to see how things can be achieved so quickly with the necessary effort.” - Local Government, Focus Group, July 2020

However, this transition was also a source of stress for leaders who saw the pandemic as an existential threat to their organisation due to their reliance on face-to-face interactions and the subsequent end of certain income streams. One leader of an apprenticeship training programme worried they might not be able to engage students remotely. To overcome this, they described reimagining the scope of their organisation, by increasing their social media presence, generating blog material and training videos, and fundamentally changing how the service would operate in the future. Similarly, leaders from the higher education sector described concerns about their ability to attract students to their courses and accommodation as the pandemic continued, with additional anxieties related to the impact of the pandemic on international students. These concerns were also highlighted in the NLC’s quantitative survey, which leaders worried would have long term consequences to university funding.

Remote working and COVID-secure facilities

Shifting teams to remote working was also a challenge for leaders who expressed uncertainty about whether this would work effectively. However, these initial hesitations were widely thought to have been unnecessary with leaders crediting staff for all they achieved and leading some to consider the possibility of reducing their estate in future. In turn, leaders described how staff enjoyed the additional flexibility and felt more trusted. There were also other smaller benefits including reducing an organisation’s carbon footprint by not printing documents, using e-signatures, online payments instead of cheques, and staff not commuting.

However, leaders noted that capabilities to work from home were not uniform across their workforces. This created challenges for managing different needs and expectations, supporting staff with the infrastructure and flexibility required to carry out their roles. This ranged from supporting parents and carers balancing home schooling with work, individuals living in shared accommodation or without suitable workspaces at home, and those who did not have an adequate internet connection for remote working. There was an immediate need for leaders to ensure staff had the equipment they needed. One leader described how their IT team provided remote working kits to all staff within eight days, working 24/7 to deliver equipment across the country. Digital poverty was highlighted as an issue particularly in the education sector where students, as well as staff, did not always have the digital technology required for remote learning. At times, education leaders relied on charities or local government to source devices, but where this was not possible or sufficient, they were concerned about the long-term impact on students.

“Digital poverty has come up a number of times and access to devices and the internet has been a significant problem.” - Education, Focus Group, August 2020

At the same time, leaders faced the challenge of rapidly making in-person work environments COVID-secure. This involved sourcing adequate supplies of PPE and managing adjustments to the workplace. In a number of cases, leaders described working with local companies to procure PPE given national shortages. One hospital Foundation Trust worked with a local textiles business to set up a PPE factory to deliver daily supplies, given the extent of their concerns about procuring equipment through existing channels.

“Some of the anxieties colleagues had we had no control over. For example, very valid anxiety over PPE we had no ability to do anything about it. We felt out of control. We only felt better when we found a local company and arranged with them directly to make us some visors.” - Health Care, Depth Interview, September 2020

PPE supplies as a pressing issue

PPE supplies and COVID testing for staff were significant issues for leaders in health care and emergency services – both were selected as one of the top most pressing issues in the quantitative survey based on the overall number of responses between March and June 2020. Although across sectors, the numbers identifying PPE supplies as a pressing issue reduced significantly over time.

At the highest point (Wave 3) 28% of leaders reported this as a pressing issue, compared to 1% at the lowest point (Wave 10). The qualitative research suggests this decline may have happened as organisations established supply lines and adapted to new ways of working.

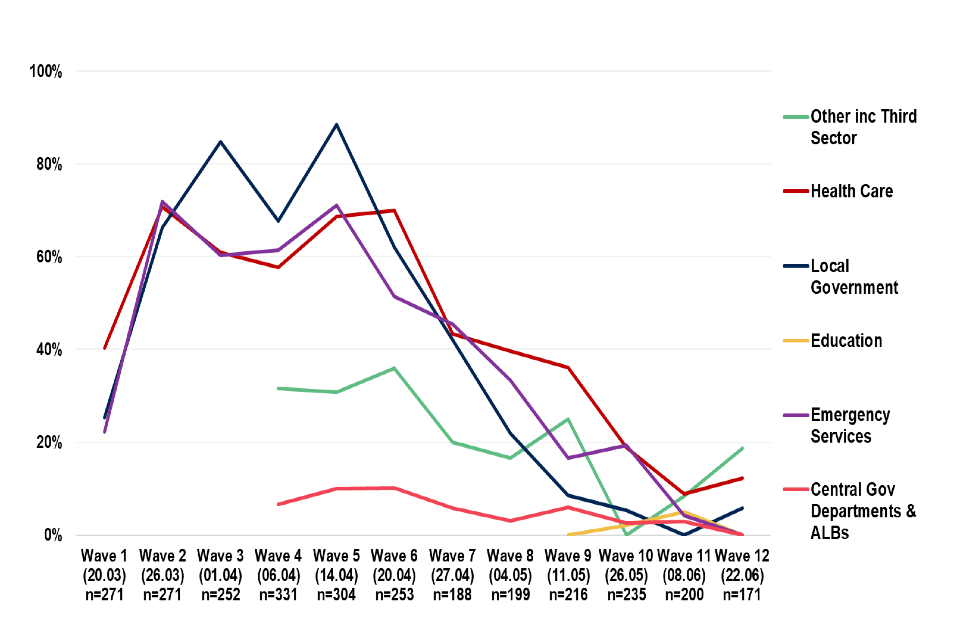

Figure 1.4: Percentage reporting PPE supplies as one of their three most pressing issues by sector, Waves 2-12.

A graph showing percentage reporting PPE supplies as one of their three most pressing issues by sector, Waves 2-12.

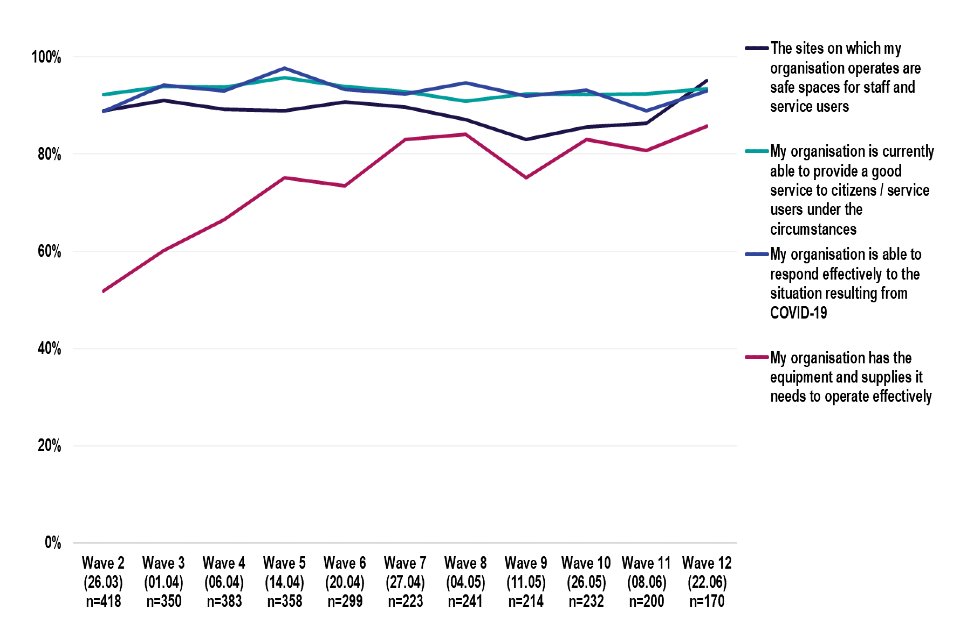

Similarly, at the start of the national lockdown only half (52%) of leaders agreed that their organisation had the equipment and supplies it needed to operate effectively. This steadily rose to 86% in June 2020 as organisations adapted.

Figure 1.5: Percentage agreeing that organisations were equipped to respond to the pandemic, all sectors, Waves 2-12.

Graph showing percentage agreeing that organisations were equipped to respond to the pandemic, all sectors, Waves 2-12.

Despite this, leaders were near unanimous in agreeing that their organisation was able to respond effectively to the situation, provide a good service to citizens and service users under the circumstances, and that the sites on which their organisation operates were safe spaces from the second wave of the survey (the first wave when these questions were asked). In this way, although there were significant concerns about sourcing equipment and supplies in the early stages of the pandemic, leaders had full confidence in their teams to continue to deliver services and respond effectively as highlighted in the qualitative findings.

Social distancing measures often meant limiting the number of people that could be on-site at any given time, resulting in potential reductions to services as well as implications for the workforce. One leader described having to make their canteen staff redundant as their biggest office could only accommodate 30% capacity to comply with social distancing measures. Similarly, courts were redesigned to enable hearings to continue while complying with social distancing measures with the capacity in some courts reduced from running six to one jury trials at a time. All these adaptations were made at pace while organisations continued to deliver services, putting pressure on teams and requiring extensive project management and logistics support.

“We opened the first jury trial in six weeks from first examination of the building to first use of it. That is phenomenal when you consider sorting the technology, making physical changes to the fabric of the building, getting in security guards, getting it cleaned.” - Central Government, Case Study Interview, March 2021

During later stages of the pandemic, leaders and teams were responsible for organising frequent COVID-19 testing of staff and managing incidents of positive tests, including returning people to work after false positives. This required additional infrastructure and logistics to ensure organisations had the equipment needed as well as staff to carry out these additional tasks beyond normal service delivery. These challenges were especially prominent in closed environments like hospitals and prisons where the risk of an outbreak was greatest.

Resourcing the response

While organisations changed how and where they delivered services, the workforce was also being affected by the pandemic at an individual level. This presented further challenges for leaders in supporting their workforce while managing service delivery.

“The crisis began for us once the staffing levels began to fall. There were a few early false alarms of individuals reporting that they had the virus and we had to stop everything each time.” - Education, Depth Interview, August 2020

Many of those working face-to-face were exposed to the virus or were required to shield or isolate, with implications for the number of staff available. One ambulance service reported having up to 25% of its workforce absent during the second nationwide lockdown and needing to rely on support from the fire service, who were fully trained to attend emergencies, to help drive ambulances and support paramedics where needed. More generally across organisations, staff were redeployed to the frontline or placed on furlough, with implications for how services could be maintained. The rapid increase in the scale of some services led to both formal recruitment and a greater reliance on volunteers and unpaid carers to try and overcome the resourcing shortage. One leader described how a programme they were setting up rapidly increased in scale by a factor of five, requiring them to hire and train hundreds of new staff while working from home. Often measures relied on public and professional good will to support efforts. For example, some air ambulance services were forced to furlough staff as they were unable to implement social distancing in their helicopters. Instead, air ambulance staff volunteered at hospitals.

“A lot of this wouldn’t have happened if it wasn’t for unpaid carers, and a lot of our response wouldn’t have worked without them.” - Health Care, Depth Interview, July 2020

Leaders from some sectors, especially higher education and fire services, explained how negotiating with unions added pressure to resourcing during the crisis. Unions needed to be satisfied that leaders would provide adequate safeguards or compensation for staff such as a COVID-secure working environment, PPE provision or paid overtime. Providing reassurance that these provisions were in place delayed the response as these issues had to be finalised before staff could return to work or be redeployed. Where there were pre-existing positive relationships with unions, it was easier to coordinate collaboration across sectors. For example, one fire service was able to offer support at no expense to local ambulance services, relying on existing relationships, a relaxation of funding and greater flexibility in terms of service delivery.

Although the predominant focus was on resourcing the emergency response, leaders also highlighted anxieties about their future financial situation as a result of the pandemic. In addition to the cost of the response itself – including additional equipment, staff and technological support – existing transformation programmes had also been paused with implications for the future. One council Chief Executive described how the pandemic interrupted the implementation of programmes designed to make savings, funding the council would not get back.

“Our issue is losing council tax. If people are made unemployed and if the council can’t make the money back, we’ll need to make up the savings. Frankly we’ll be back to having to make some savage cuts.” - Emergency Services, Depth Interview, August 2020

Workforce availability

Issues of workforce availability also became significantly less prevalent over time in the issues reported by leaders in the quantitative survey. This was particularly noticeable within health care (42% mentioning it as a pressing issue in Week 2, compared to 5% in Week 12), where many leaders initially reported difficulties maintaining critical services due to the proportion of their staff self-isolating. However, concerns among leaders in emergency services increased in the last waves of the survey period (although still reaching up to just 14%), with leaders describing concerns about large proportions of their workforce needing to self-isolate as a result of positive contacts through the Test and Trace app.

3.1 Summary

From the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the most significant challenge facing leaders was the need to quickly transform services to continue to meet citizens’ needs. Transitioning services online, supporting teams to adjust to remote working and making locations COVID-secure often had to happen at the same time as maintaining services, without a chance for planning or consultation.

These challenges were immediate in March 2020 and tended to ease as organisations adapted to new circumstances. Challenges were overcome by:

- Staff resilience and their willingness to work hard and quickly. Teams pulled together and worked longer hours to ensure services were able to adapt. Individuals, including leaders, often went beyond the traditional remit of their role and at times assumed additional responsibilities.

- Motivation to ensure services could continue. Staff recognised that the pandemic posed an existential threat to parts of their service, which created a shared purpose bringing people together. In some sectors, organisations were also working to limit the pressure on the NHS and were motivated by playing a part in their region’s response to the crisis.

- Collaboration with public, private and voluntary sectors. Organisations worked together to offer support to each other in the form of expertise, supplies and resourcing. This was vital to the response given the scale of change required, the reduced workforce as a result of COVID-19, and the level of demand for critical provisions such as PPE supplies.

- Creative thinking and flexible processes. Adapting service delivery at pace required leaders to think creatively about how to redesign their approach, testing new ideas and accepting that not all policies would work perfectly first time. This required greater flexibility in decision-making, with organisations reducing standard processes to allow for greater innovation.

Both collaboration and decision-making during the pandemic are discussed in more detail in the subsequent chapters.

4. Collaboration across public services

Increased collaboration between public services was consistently highlighted as one of the most positive experiences of the pandemic. Not only did certain services become increasingly reliant on volunteers and unpaid care staff, other providers stepped in to support local communities often going beyond their traditional remit. This was especially notable in public, private and voluntary sector organisations coming together to support the health response. As such, collaboration enabled leaders to overcome challenges associated with transforming service delivery as organisations shared their expertise, supplies and wider resources. Examples included:

- Private sector businesses procuring and producing PPE for health and care workers;

- Local authorities, private landlords and local businesses renting out venues to HM Courts and Tribunals for use as temporary courts;

- Fire services diversifying their remit to support other organisations including delivering food parcels to self-isolating residents, managing the distribution of PPE, supporting local logistics operations and delivering laptops to school children;

- Fire stations offering their premises as sites for blood and plasma donation;

- Local authorities and the army working with NHS organisations to establish and man COVID-19 testing sites;

- Police services assisting NHS organisations with the logistics of increasing bed capacity and the establishment of additional mortuaries.

Activities were often organised through existing relationships between leaders who recognised a need and could provide the resources or capacity required by others in their area. However, organisations including private businesses also approached leaders with offers of support and new relationships built during the pandemic brought public services together for the first time. Leaders spoke positively of the high degree of local ownership involved in the management and running of partnership working, with place-based solutions proving vital to the effective co-ordination of the response in local areas.

This section brings together leaders’ reflections on working in collaboration to respond to the pandemic.

More responses

Improved collaboration resulting from the pandemic

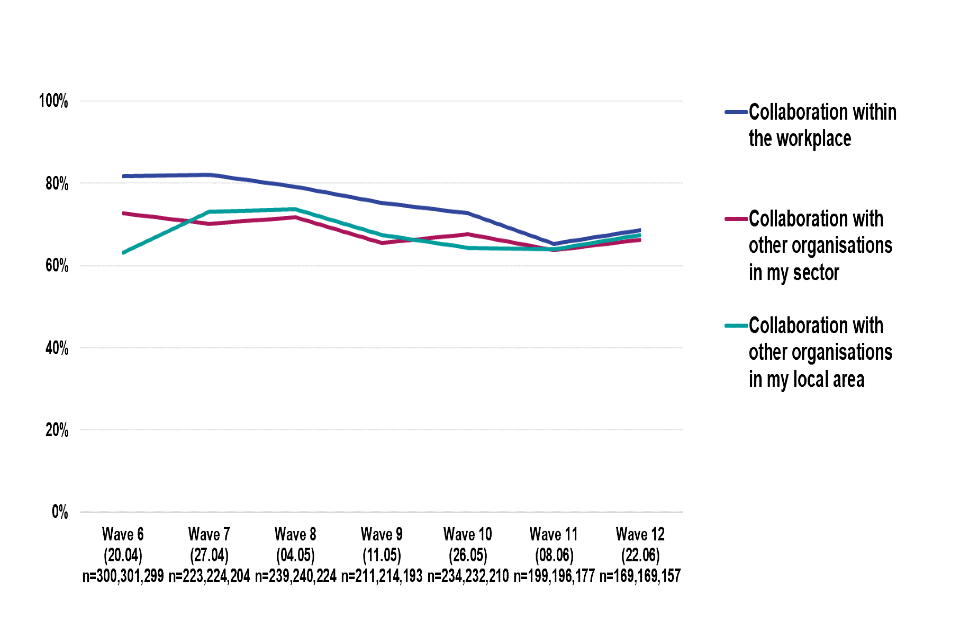

Collaboration was one of the most positive themes from the survey. The majority of leaders consistently reported that collaboration was better than in usual circumstances within the workplace (ranging from 65%-82% across waves), with other organisations in their sector (64%-73%), and in the local area (63%-74%). This varied between sectors, with health care and local government reporting the biggest overall improvements in all three areas from late April to June 2020.

Positive views about improvements in collaboration with other organisations within the sector and the local area were mainly stable throughout all, or most, of the survey period. The proportion of leaders reporting improvements in collaboration in the workplace was initially the largest but reduced significantly over time to the same level as the other measures. This reduction was most prominent within health care (91% to 75%) and central government departments and ALBs (48% to 38%). Across sectors, even in the last wave, around two in three reported that collaboration was better than in business as usual.

Figure 1.6: Percentage reporting collaboration has been better than usual, all sectors, Waves 6-12.

Graph showing percentage reporting collaboration has been better than usual, all sectors, Waves 6-12.

Formal structures for collaboration in local areas

At the beginning of the crisis, many leaders were immediately involved in co-ordinating regional responses, often through formal structures such as chairing Local Resilience Forums (LRFs) or Strategic Coordinating Groups (SCGs). These groups existed before the pandemic but met on an infrequent basis. Early on, LRFs were used to co-ordinate the emergency response in accordance with the Civil Contingencies Act, acting as the focus point for planning local activities and gathering information. SCGs supported decision making by bringing together key leaders from emergency services, local government and health care services. Together, these forums provided a space for leaders to co-ordinate activities locally and share resources. Although the same structures existed across the country, the approach and individuals involved were based on local needs. Through LRFs and SCGs, many leaders rapidly established working groups to focus on elements of the local response. By dividing responsibilities and giving individuals ownership of a theme, leaders were able to share the workload and ensure areas beyond public health, such as the local economy remained a priority.

Some leaders held places on strategic boards and were leading the co-ordinated efforts in their local areas on issues such as health care, policing, and care homes. Leaders involved in these forums rapidly moved from meeting every few months to meeting daily, which entailed a significant time commitment. In certain areas the individual charged with chairing the SCG was rotated between local leaders to spread this burden. In addition to attending meetings, leaders were required to read briefing documents and stay abreast of government advice as well as delivering on various local needs. The leaders appointed as chairs of these groups tended to be from the emergency services or universities as they were considered impartial. Political neutrality was seen to be particularly important, especially in areas with organisational, social or political tensions.

“I’ve been chairing and rotating with the police, for seven days meeting at one o’clock and you have to gather lots of information before you can attend and chair that meeting. It brought with it an exponential increase in workload.” - Emergency Services, Depth Interview, August 2020

Shared purpose and motivations across the system

The scale, severity and sustained nature of the pandemic provided a clear and shared purpose for organisations to collaborate towards a common goal. Pre-pandemic priorities dissipated as the emergency response meant organisations across sectors and regions worked together towards the same, small number of outcomes. Organisations were brought together through formal structures as well as the frontline response. For example, the NHS worked with local councils and the armed forces to set up COVID testing sites. These instances allowed the establishment of relationships and trust, which in turn facilitated collaboration.

“There were three priorities: preserving life, supporting the vulnerable, and doing what we can to protect livelihoods. There’s been a unity of purpose which brings out the best of the public sector.” - Local government, Depth Interview, August 2020

The severity of the pandemic meant organisations were collectively focused on the outcome to preserve lives and protect the NHS. This meant processes, such as completing full risk assessments or extensive forward planning became less important as organisations collaborated to meet a common goal. To achieve this, there was greater flexibility and willingness to share resources, knowledge, expertise and data. This often overcame the traditional challenges associated with incompatible structures and processes between organisations. There was a central belief that outcomes needed to be achieved to ease the burden on the health care sector, which if not met, would have an impact across the local system. Leaders noted this was evident among almost everyone involved, from senior management to volunteers, and from public, private and voluntary sectors.

“I think we have learned to be more focused in what we are trying to achieve, to focus on the outcome rather than spend lots of time thinking about all of the inputs, issues and activities.” - Central Government, Depth Interview, August 2020

Additional funding meant organisations could achieve joint goals with less concern about which partner was financially responsible for decisions. In health care, pooled central funding meant organisations were able to help people without needing to decide which organisational budget support came from. This also reduced competition between partners as they were delivering services in tandem, from the same funding pot.

“[Previously] most areas of disagreement with councils was who is paying for an elderly patient? Are they ours or are they yours? The fact that all the funding was pooled and funded from a central source had a huge impact and that’s not going to continue indefinitely.” - Health Care, Depth Interview, August 2020

However, there was scepticism about whether this level of collaboration would continue. In the autumn, some leaders within the health care sector pointed to signs of financial competition resurfacing as routine services returned. Across sectors, there was a sense that the immediacy of purpose created by the early stages of the pandemic was easing as organisational priorities more broadly rose in prominence. For example, a leader from the education sector described how universities had shared learning during the early stages of the crisis around making campuses COVID-secure and delivering remote learning. However, the same leaders took individual responses to the government’s handling of exam grades in the summer, as their priorities shifted towards the organisational need to attract students.

Increased awareness and building relationships

Having shared priorities and a common purpose brought leaders and workforces together out of necessity. Working together through both formal and informal channels strengthened local relationships, with leaders frequently describing the generosity of people across their area. As well as the formal structures described above, leaders quickly established informal communication channels such as WhatsApp groups to share information. Although the local response often involved forming new relationships, leaders emphasised the value of their existing contacts. This enabled them to work faster based on existing bonds of trust, to delegate decisions as well as to offer a form of peer support.

“My experience is that if you’ve been through crises together you will always go the extra mile if it has been positive. I think it will survive, but what will damage it is the competition stuff which is just part of life.” - Housing, Depth Interview, September 2020

During this time, leaders also gained a greater understanding of the roles, experiences and expertise of other organisations through open discussions, temporary redeployment of staff to other areas, and resources explaining roles and organisational structures. This facilitated collaboration as it was easier to identify common goals, share resources and avoid overlap or duplication of effort. For example, the probation service shared information sheets with local authorities which detailed the funding they had available and how it could be used to provide prison leavers with housing during the pandemic.

“I met some firefighters this week who work in [the fire service’s Education Team] that provides safety education to schools on water, fire and road safety. It’s common sense to think that these roles exist in the fire service, but you don’t think about them. . . There are so many roles the fire service fulfils so why are we not tapping into it?” - Charity sector, Case Study Interview, March 2021

4.1 Summary

Increased collaboration between public services was consistently highlighted as one of the most positive experiences of the pandemic. Leaders widely described how previous barriers to collaboration including misaligned structures, competing priorities or ineffective communication, fell away as organisations came together to respond to COVID-19. Increased collaboration was enabled by:

- Pre-existing emergency response structures. Structures such as Local Resilience Forums (LRFs) and Strategic Coordinating Groups (SCGs) kicked into action at the beginning of the pandemic, meeting on an almost daily basis. These forums created spaces for leaders to communicate more regularly, identify local needs, share resources and build trust without having to establish a new body to co-ordinate the response.

- A shared purpose. The scale, severity and sustained nature of the crisis fostered a sense of a shared purpose as organisations worked together to support their region’s response. Many organisations went beyond their traditional remit to support other services in their area, with the pandemic response taking priority over individual, organisational aims. There was greater willingness to provide support, with less concern about the longer-term implications on organisations.

- A focus on outcomes as opposed to processes. The need to make fast decisions meant organisations shared resources, expertise and data more freely without always going through the formal processes required in business as usual. This created a spirit of openness and flexibility to achieve the outcomes needed, reducing bureaucratic barriers that had previously limited collaborative working.

- Additional funding enabled collaboration as there was less concern about which partner was financially responsible for decisions. At times, funding was pooled between organisations, further reducing competition and enabling joint decisions.

- Building and maintaining new relationships. Public services relied on each other throughout the pandemic and this created a greater willingness to build relationships and learn more about what each organisation does and how they can support each other. Increased remote working has also removed physical barriers, expanding leaders’ networks and enabling individuals to work together across greater distances. Leaders felt that to maintain these relationships they needed to continue open and frequent communication to build mutual understanding and trust.

Leaders described wanting to maintain these collaborative relationships after the pandemic as they had discovered how much each organisation could offer and recognised the potential to reduce the duplication of work. However, there was some scepticism around whether this level of collaboration would continue, with signs of financial competition and different organisational priorities resurfacing.

5. Decision making at a time of crisis

Throughout the pandemic, leaders had to make decisions in a context of sustained uncertainty often exacerbated by unclear or short-notice communications. This created significant challenges for leaders who adapted decision making processes to reflect the emergency response. They also grappled with balancing risks, delegating decisions and increasing scrutiny as the pandemic developed into the autumn. This section brings together leaders’ experiences of making decisions and adapting how they do so as part of the emergency response.

Responses and quotes

5.1 Dealing with uncertainty

Leaders faced significant uncertainty while implementing major changes to service delivery and the wider anxiety brought by the pandemic. Particularly in the early stages, they did not know how the situation would develop, how long it would last or what the impact might be on day-to-day life. Consequently, it was difficult to properly gauge and plan for likely outcomes, creating significant challenges for knowing how to lead during this time. One leader described feeling daunted at the prospect of transforming a conference centre into a hospital within ten days with a team they had never worked with before. They emphasised the challenge in learning to be comfortable with uncertainty and the unprecedented nature of the situation. They were unsure whether the task was even possible and were unable to know what everyone involved was doing, despite being responsible for the project.

That said, having embraced this uncertainty many leaders found it invigorating. They described gaining energy and momentum from being at the heart of fast-paced decisions that really mattered to their community and teams.

“There’s something quite exciting about a crisis. As a leader you are trained for drama, when you have to think things through, when something has never happened before. It was really interesting, stimulating, making my brain work. Just feeling free from all the rules.” - Housing, Depth Interview, September 2020

Some sectors (like the emergency services) had more experience of dealing with uncertainty as their job often requires them to respond to emergency situations based on developing information. However, across the board, leaders agreed that decision making during the pandemic was more complex, faster and had a greater impact on staff and the public than normal. For example, during the early stages of the pandemic leaders had to make quick decisions about remote working, fundamentally changing how their teams operated based on limited knowledge about how long the pandemic would last. The sustained nature of the crisis created a substantial challenge for leaders who struggled to know what timeframe to make decisions for.

This uncertainty was exacerbated by the inadequacy of existing business continuity plans which did not prepare organisations for the scale and sustained nature of the pandemic. One leader from central government explained how the early spread of the virus led them to update their business continuity plan, but this was outdated a fortnight later reflecting the rapid development of the situation. The move to remote working also highlighted issues with the resilience of IT systems. For example, one leader in local government described how their server froze when too many of their employees tried to log onto it from home, so they had to work at pace to find a digital solution. Leaders in the emergency services tended to believe their continuity plans had been more resilient, with many having prepared and practiced for a flu pandemic outbreak.