2023 survey of law enforcement use of uncrewed aerial vehicles

Published 1 September 2023

Applies to England and Wales

In March 2023, the Biometrics and Surveillance Camera Commissioner Professor Fraser Sampson wrote to all 47 police forces in England and Wales, seeking to clarify and develop the picture of the uncrewed aerial vehicles (UAVs) or ‘drones’ used by policing and law enforcement in England and Wales.

This followed the publication of the Commissioner’s 2022 survey of police use of overt surveillance camera systems in public places, where a general overview of use of UAVs was initially identified.

The letter sought answers to 11 questions about the use of UAVs and counter-UAV technology, to which we received a 77% response rate (36 responses). Of these, 3 forces stated they do not use drones [footnote 1]. These findings are based on the returns of 34 forces across England and Wales.

Headlines

Most forces who use UAVs are aware of which manufacturer and models they are using, as well as how long they have been in use. When asked about counter-drone technology, however, many forces referred us to a different body for this information. This indicates a lack of integration in the approach to this field.

Forces were uncertain of the security risks around the use of UAVs and what protocols they have in place to mitigate them.

Findings

Q1

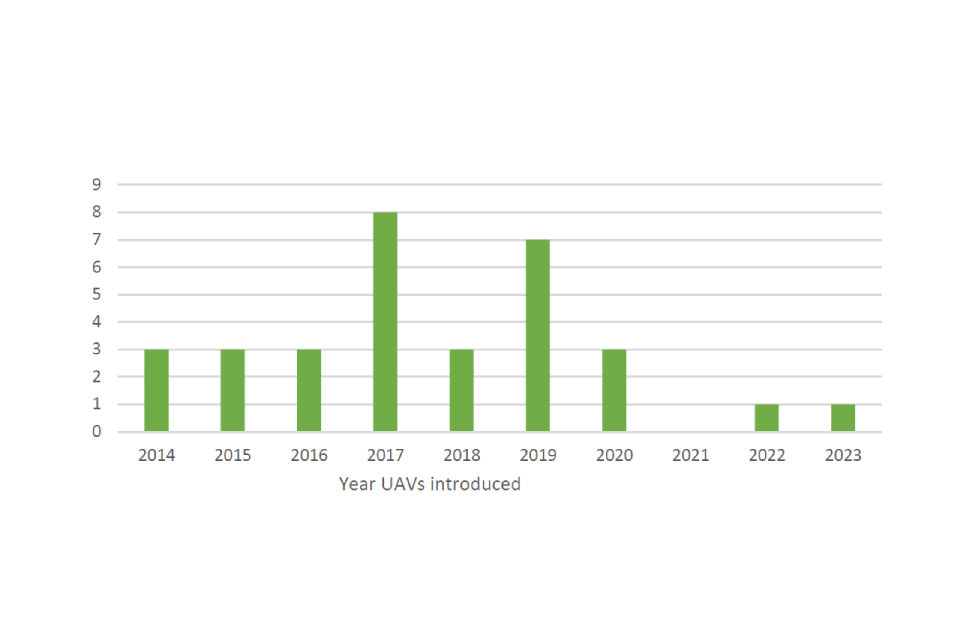

Over half of the returns received (62%) reported that their force introduced the use of UAVs between 2017 to 2020. A quarter of these were between 2014 and 2016. Two forces have only introduced UAVs in the past 2 years, while one force did not provide this information.

Q2

Overall, there were 9 different manufacturers reported by forces. All forces who confirmed they deploy drones use DJI-manufactured drones.

Q3

Perhaps the most important question relating to data security, 62% of forces (21 respondents) stated that they use a standalone device (for example a mobile phone, laptop or tablet) to control their UAVs when they deploy one or more. Similarly, 59% use the manufacturer’s controller or the UAV itself.

In terms of connectivity, 6 forces answered they use wifi, 2 forces stated they use a HDMI cable, and one force also uses a command vehicle, however no further detail was provided to clarify these responses.

Q4

The most common protocol in place to protect against data breaches is use of an SD card to extract footage from the UAV (62% of responses), which is then wiped afterwards. 18% stated they download the footage digitally, most using encryption or carried out behind a firewall. One force made no mention of using any form of firewall protection when downloading, while another stated they store all data on the UAV itself, providing no further information regarding what happens when the memory is full.

Only 3 forces specifically mentioned adhering to the Guiding Principles within the Home Office Surveillance Camera Code of Practice (SC Code). Two forces stated they have not considered any protocols as they have not identified any security risks.

Q5

As well as what protocols are in place to mitigate security risks, it was useful to find out what considerations forces give regarding the sensitivity of a site. Most forces said they assess the need to deploy on a case-by-case basis. Some forces said they never deploy to sensitive sites and thus have no protocols. This could be cause for concern as a site’s sensitivity can be fluid, for example by visits of key individual, temporary change of function (as in the case of polling stations) or other events taking place in the public eye (see below on counter-UAV technology).

This question has highlighted the need for much clearer guidance on how sensitivity is measured and what protocols forces should be taking to mitigate security risks. Having guidance in place would also remove the need for hastily contrived policy.

Counter-drone technology

Q6

The second half of the survey asked for details on the use of counter-UAV technology (C-UAV).

Six forces stated they do not use C-UAV technology, one of which also stated they do not have plans to implement it in the future. Of the 28 remaining who do, nearly 80% referred us to another body better-placed to provide an answer. These were either the National Police Chiefs’ Council (NPCC), the Counter Terrorism Policing Headquarters (CTPHQ) or the Home Office Counter Drones Unit (CDU).

Two forces mentioned the only times they have used C-UAV technology is for major events such as The Open and the King’s Visit (reinforcing the comments above about transient sensitivity).

Q7

When asked what year C-UAV was introduced, if in use, again most forces referred us to either the NPCC, CTPHQ or CDU. Of those that did provide an answer, every force said between the years 2019 to 2022, therefore somewhat later than their own use of UAV.

Q8

Regarding security training around the use of CUAV’s, again most forces referred us to either the NPCC, CTPHQ or the CDU. Of those that did provide an answer, nearly 60% use internal training methods, such as their own training sessions and bulletins around their headquarters. Fewer than 20% said they source security training externally, and the remaining 20% said they use both.

Q9 and Q10

We also asked what policies and procedures forces have in place to mitigate security risks when updating their UAV technology.

Some forces, again, referred us to the NPCC or CTQPH, however most forces did provide an answer.

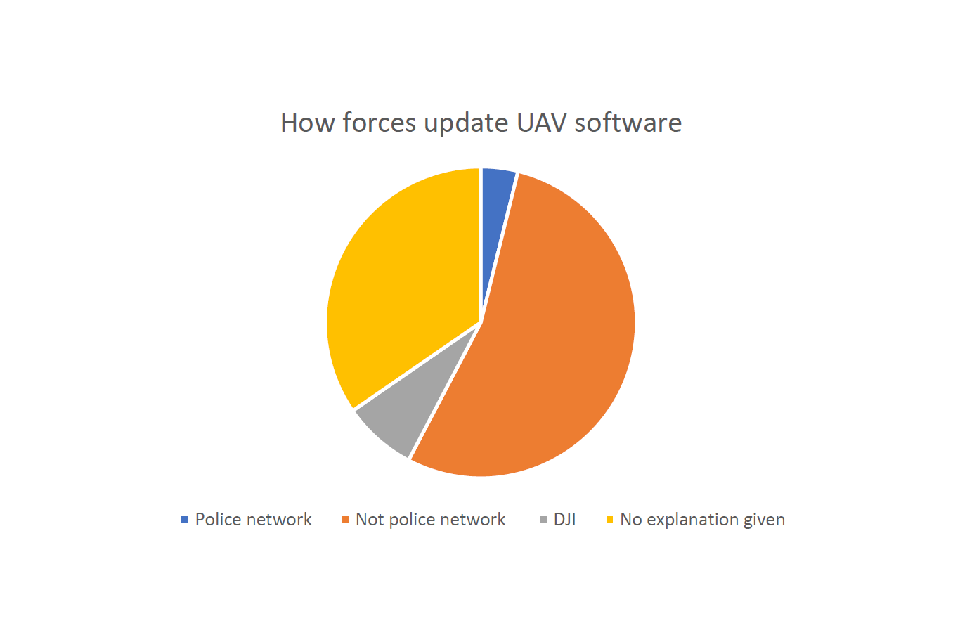

Of the 26 forces that responded, just over half (54%) said that software updates are never done on a police network, instead via either a standalone laptop or an independent wifi connection.

What raises some concerns is that of the forces remaining, 35% did not explain how their systems are kept up-to-date, merely that they are. Without any further detail from forces on this response, it is not possible to say whether this is a matter for concern or not. One force stated they do in fact make updates via their police network, and 2 forces said they do it through the manufacturer.

Q11

Finally, we asked who holds their use of UAV and C-UAV to account, and how often.

Again, most forces referred us to the NPCC or CTPHQ. There was nearly an equal number of forces who answered that they are held to account internally, those who use an external body, and those who use both. The external bodies mainly included the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA), while only 2 forces mentioned the Biometrics and Surveillance Camera Commissioner’s Office.

It is worth mentioning that none of the forces mentioned being held to account by their Police and Crime Commissioner (PCC), the Police, Fire & Crime Commissioner (PFCC) or the Mayor’s Office for Policing and Crime (MOPAC), These are the only bodies with legal responsibility for holding Chief Officers to account.

Only 7 of the forces who gave an answer gave us a timeframe. Most said this was yearly, however some also said quarterly, and one said monthly. There were 4 forces who said they have not implemented any protocols to hold them to account, and one force responded that they do not know who holds them to account.

Recommendations

-

Guidance needs to be made available to forces on the procurement and deployment of surveillance technology from companies whose trading history and engagement with accountability frameworks has raised significant concern and the attendant risks.

-

Guidance is needed on how to mitigate UAV-specific security risks, such as hacking and the use of counter-UAV technology.

-

Chief officer should seek a single, overarching approach from their local elected policing bodies to ensure that:

- a. they have agreed mechanisms for holding them to account publicly and

- b. the procurement and deployment of UAVs is demonstrably ethical

4. Chief officers should consider a standardised, and documented, procedure for assessing sensitivity, whether that relates to a geographical site or a more transient operation involving the use of UAV. Guidance on the assessment and measurement of sensitivity is urgently needed.

Annex: survey questions

-

When were UAVs introduced into your force?

-

Details of the UAV and Uncrewed Aerial Systems (UAS) manufacturer(s): makes and models used or available to you or collaborative partner agencies, including Fire and Rescue, Local Authorities, and coast guard.

-

Which ground control stations are used when your force or others deploy UAVs in or over your force area and how do these work in practice (e.g. standalone base unit, force issued mobile phone running internal apps, or on a force laptop)?

-

What mitigations/protocols are in place against possible data/security breaches when this technology is used in or over your force area.

-

When deploying UAVs, what considerations are documented as to their suitability when assessed against the security rating of the incident?

-

Details of manufacturers of any counter-UAV technology and operations together with details of the ground operating systems used.

-

When was counter-UAV technology introduced to your force?

-

What security training is in place around the deployment of this technology? Specifically, what security training is given to pilots of UAVs and those deploying counter-UAV technology, and the technical teams supporting their deployment.

-

What policies and procedures do you have in place when updating software, firmware or flight apps provided by the manufacturer?

-

When considering tactics, techniques, and procedures, what penetrating testing has been completed against Counter-UAV equipment being used?

-

How, where, and how often is your use of UAV/Counter-UAV capability held to account for your force area?

-

The 3 forces not using drones are Civil Nuclear Constabulary, West Mercia and Northumbria. ↩