Joint Analysis of Conflict and Stability (JACS) guidance note

Updated 14 November 2024

1. Overview

1.1. What is the JACS?

A Joint Analysis of Conflict and Stability (JACS) is a strategic assessment used to underpin UK national security strategies or their equivalents, as well as HMG policy and programming. The process is flexible and can be used to determine answers for different policy questions and programme objectives, however its key purpose is always to inform decision-making.

A JACS helps the UK government to understand the historical and current causes of a conflict, the relationships between key actors, and what drives the conflict now. The JACS adopts a similar analytical framework to other strategic conflict assessment tools, and it brings together teams from across government departments to result in a shared understanding of the actors involved in and the causes and drivers of conflict in a particular situation, and agreement on the key priorities for UK government intervention.

The process is focussed on identifying where the UK government should collectively put its efforts on supporting conflict prevention and resolution, resilience, stability, and peace, balanced against relevant risks. Without well- evidenced and coordinated interventions (from the strategic to the local) there is a higher risk of missing peace opportunities, inadvertently exacerbating conflict dynamics, failing to respond appropriately to the context, and undermining UK interests.

A JACS can:

-

sharpen decision-making by providing a common understanding of the context in which the UK is engaged, ensuring that the government’s approach is tailored, realistic and achievable

-

steer decision-making by providing a compelling rationale for UK engagement on addressing conflict, supporting prioritisation and ensuring a focus on what is most important

-

challenge decision-making by allowing for an honest discussion on prioritisation, trade-offs and competing interests of UK engagement and competing interests, flagging potentially harmful consequences of various courses of action

The JACS was originally introduced by the UK’s Building Stability Overseas Strategy (BSOS) in 2011 as a tool to strengthen cross-government approaches to tackling overseas conflict and instability. The approach was reviewed in 2014 and again in 2023 through cross-government consultations. This update follows the most recent review and provides new guidance on a ‘scalable’ model as well as new supporting elements to the core methodology.

1.2. JACS principles

1. Jointly commissioned and signed off at a senior level

The role of senior commissioners – ideally geographic directors or HMAs – is not simply to approve work on a JACS but to champion and resource it.

2. Commissioned with a clear strategy, policy or programmatic decision point in mind

Government departments need to agree the purpose of the JACS which are typically commissioned when the context and/or UK engagement has shifted; in response to an emerging risk; or ahead of key decisions. This will determine the appropriate scope, depth of analysis and frequency of updates.

3. Be internally owned and managed to support shared understanding

External consultants and experts can play critical roles, but it is key that the process involves participation throughout from relevant HMG stakeholders at Posts and in the UK: eg conflict advisers, defence attaches, political teams, desk officers.

4. Carried out and overseen cross-departmentally

JACS should be joint at all levels – oversight, drafting and delivery. In practice, departments often have different levels of resources that they can commit, but wide consultation and engagement is vital.

5. Meets minimum standards of quality assurance

Following the robust analytical framework, making use of external challenge to avoid group bias. FCDO Research Analysts and Defence Intelligence Analysts can play a key role here.

6. Based on all available source material and seeks external challenge

The available time and resources will determine the breadth of stakeholders and sources that can be consulted, but it is critical to integrate a mix of perspectives and to design the process to invite challenge, especially from outside HMG.

7. Be proportionate to the need

JACS should be scaled to meet the decision-making requirements in a way that is proportionate – there is no one-size-fits all.

8. Lead to future action

JACS recommendations should be action-oriented. JACS commissioners should ensure follow up is built into the process when the analysis is complete.

9. Aligned with wider UK policies and strategies

Analytical findings should be linked with key relevant thematic areas of government policy, such as Women, Peace and Security, serious organised crime, and counter-terrorism.

10. Conflict and gender-sensitive, in both process and outcomes

The process of JACS research and analysis should not cause harm (for example, placing key informants at risk). JACS recommendations need to be reviewed for their likely impact on the conflict and the risk of doing harm.

2. Outline

2.1. Using this guidance note

This guidance note sets out the essential components of the analytical framework and provides practical guidance for users who are designing and delivering a JACS. It is designed to be used flexibly, according to need and dependant on resources available.

There is additional detail on some of the approaches and tools to apply the analytical framework available from OCSM, including on atrocity risks and prevention, integrating climate and conflict, scenarios approaches, and conflict and stability trackers.

There is also more information for teams that want to engage OCSM support in delivery, including its roster of consultant experts.

2.2 Process

The JACS methodology has 3 main phases:

Initiation phase:

- establish need and scope for a JACS

- appoint a lead and agree on stakeholders

- develop terms of reference outlining aims, methodology, roles and timeline

- conduct literature review and additional research to inform analysis

Analysis phase:

- identify causes of conflict across security, political, economic and social domains, including structural and proximate causes

- analyse the main conflict actors – their interests, motivations, power

- understand dynamics between actors and causes to reveal key drivers and overall conflict trends

- identify potential triggers for further conflict

- identify sources of stability and resilience

- identify and, where possible, quantify the manifestations of conflict, showing the links to UK interests or national security

- recognise opportunities to promote stability and peace, including opportunities to initiate or support dialogue processes seeking a sustainable political settlement

Utilisation phase:

- hold discussions on key analysis findings

- develop recommendations for UK actions to mitigate conflict and align with UK aims

- ensure recommendations are conflict-sensitive, utilise UK strengths, reflect policy realities and resources

- connect findings and recommendations to actions, and establish suitable monitoring

2.3. Outputs

The JACS process is centred on informing decision-making. Outputs from the process should reflect this: they should be concise and focussed on policy implications or actions. (see 3.1 Proportionality).

The principal product in all cases should be a short paper covering the key findings. This should be a maximum of 20 pages and cover the key points from the analysis, any policy implications, and the recommendations. It does not need to summarise everything the analysis has covered; additional analysis and further information can be annexed to this as appropriate.

Further outputs may include:

- a longer paper which covers elements of the detailed conflict analysis (causes, actors, triggers etc)

- thematic deep-dives on particular areas: eg climate, atrocities

- summaries of potential scenarios and responses

Note that the process of doing a JACS – bringing together a range of HMG perspectives, stakeholders and varied inputs, and discussing and prioritising future work – is an important output in itself.

Classification: where possible and practical, the JACS key findings paper should be produced at Official. This allows the findings to be shared as widely as possible with UK partners. If necessary, the key findings paper and/or its annexes may be produced at Official-Sensitive, or higher, and handled appropriately.

2.4. Who is involved?

A broad range of UK government officials are involved in a JACS

This breadth of individual perspective and expertise is critical to enabling the success of the JACS and ensuring that the analysis is utilised. There are 4 groups of key actors – commissioners, leads, authors, contributors – as well as wider stakeholders.

| Role | Responsibilities |

|---|---|

| JACS Commissioners | Initiate and sign-off a JACS. Normally the most senior individuals at Posts (ie Heads of Mission, may be several if regional) and/or at Director-level in HMG departments. Commissioners must be engaged in the process, and are responsible for ensuring it represents a joint and accurate understanding of the conflict context. |

| JACS Lead | Coordinate delivery. They are ideally Conflict Advisers, Head/First Secretaries in political sections, or Defence Attaches comfortable working across government departments. They coordinate working level inputs from across government and are responsible for ensuring the analysis meets the decision-making requirements. JACS leads report to the JACS commissioners. Several in neighbouring countries may work jointly together. |

| JACS Author(s) | Lead the research and drafting. The author, or one of them, may be the same as the JACS Lead but could be another internal actor (eg Research Analyst) or an external consultant (eg Deployable Civilian Expert). If a separate individual, they report to the JACS Lead. |

| JACS Contributors | Provide specific insight or analysis. Contributors are subject- matter experts from across government eg Research Analysts, Economists, Political Officers, Gender Advisers, Defence representatives. The JACS Lead sources, coordinates, and collates the input of the contributors. JACS Commissioners, or their representatives, should ensure relevant government departments engage and make their expertise available. |

Other stakeholders

Importantly the JACS should gather first-hand views and experiences of actors directly engaged in and affected by the particular conflict – local communities (expressly including women, children and young people[footnote 1], partner and host government politicians and officials, civil society, and armed groups.

In challenging contexts, this input may come from diaspora communities in the UK, or remotely from local civil society organisations. Additionally, the JACS will use other expert input drawn from eg UK academic institutions, think tanks, and research conducted by other organisations. FCDO Research Analysts can provide recommendations of contacts and resources.

Other donors and UK partners should also be considered as potential stakeholders. Depending on the context the JACS itself could be done as a joint process with other donors.

2.5. Timing

There is no set timeframe for conducting or updating a JACS, and the process is designed to be flexible and context-dependant. A JACS should, however, always be focussed on informing decisions, so commissioning should be linked to an appropriate decision point that will lead to action.

Reasons to commission a JACS include:

- anticipation of increased UK government engagement or to test viability of engagement, as the JACS can surface both common understandings and differences between UK government departments

- shifting operating context: this can be sudden (eg outbreak of conflict or political transition) or it may be slowly worsening risk picture which demands a thorough assessment

- new context: there is a significant benefit in conducting a JACS in a context where the UK has little institutional knowledge or experience

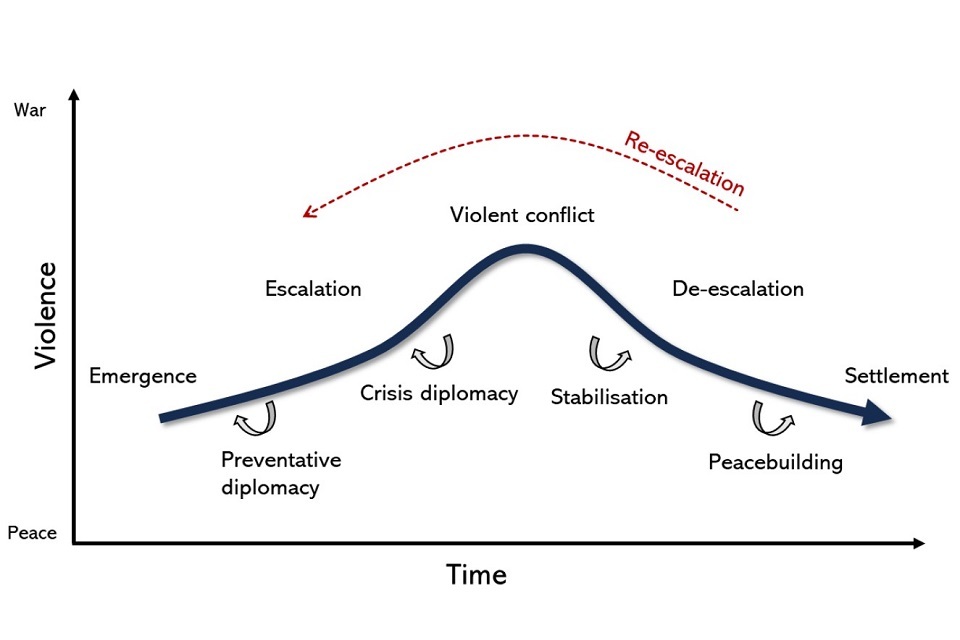

The JACS methodology can be applied at all stages of conflict (see figure below). Conflicts do not develop in a linear fashion, but can follow phases involving a growing polarisation of differences, followed by escalation and intensification of violence, followed by periods of de-escalation.

- in stages of emerging risks or escalation a JACS can be used to explore the potential triggers and risks for conflict and develop scenarios that can inform the design of appropriate strategies and conflict prevention approaches including through dialogue

- in ongoing conflict, the JACS framework can explore potential developments and the impact on UK interests and resources, grounded in a robust evidential base

- in post-conflict scenarios, the JACS can assess the durability of political settlements, identify potential risks of a return to violence and opportunities to consolidate peace

Conflicts are increasingly internationalised in their nature and usually have important cross-border, regional and transnational dimensions, sometimes central to the conflict. Confining a JACS to national boundaries may be necessary for focus and manageability but the analysis needs to recognise that the factors driving and sustaining conflict could be located externally, across borders, regionally and internally, or along networks which transcend multiple borders and contexts.

Once conducted, a JACS should be updated regularly, though the timescales may vary. In very live conflict contexts the conflict analysis could be updated on a quarterly basis, focused on key drivers and actors. For other contexts, an annual refresh or less frequent update may be appropriate.

Where they are not updated regularly, there should always be a means of keeping the findings of JACS live and identifying when an update is needed. This could be through a formal conflict and instability tracker that follows set indicators, by embedding the findings and recommendations into an existing risk process, or another method of monitoring (OCSM can advise on approaches). The methodology for updating or refreshing a JACS may simply be a comparison between the existing analysis and the current context in the form of a short workshop to identify and discuss what has changed and what the implications are for the UK government (see Rapid Review) in the scalable model

2.6. Asking the right questions

The outcome of the JACS should be action-oriented and focussed on informing decision-making. Ideally, it should therefore set out clear policy questions to answer that can provide the basis for common agreement from the commissioning group on the implications for the UK as well as next actions.

Action-oriented questions protect against the JACS becoming a purely exploratory exercise in conflict analysis that doesn’t address the implications for the UK. They should keep the process accountable and worth the resource invested. It is important to develop good research questions, which set clear boundaries as to what should be included and excluded.

JACS Leads should work with Commissioners to identify a realistic scope for the policy questions and ensure they are practically bounded for the time and resource available.

They may, for example, want to determine the sorts of decisions they want the JACS recommendations to address at the outset.

Where specific policy questions are harder to identify, teams can set hypotheses for the analysis to test assumptions about the trajectory of existing or planned UK activity. You may find it useful to do an initial inception report in these cases, to narrow down the scope and refine the question set for the main analysis. It could cover eg:

- brief context of the history of conflict and any relevant political details

- where existing HMG interests and strategic priorities lie

- the long list of proposed questions and preliminary findings (based on eg a lit review)

- what initial blockers and limitations arise for further evidence collection

- whether any of the proposed questions are immediately answerable (quicker) or significantly more complex (longer)

- a refined list of questions based on the above

- a workplan for the main analysis (timings, responsibilities)

A JACS is a powerful tool for programming – although it’s focus should be broader than just programming and seek to provide a robust analytical evidence base for wider UK strategy and policy positions to address conflict and instability.

3. Key concepts

3.1. Proportionality

The JACS is intended, under the most recent Review, to be a flexible approach. The process should be proportionate to need and suited to the context in which it is being undertaken. That means:

- proportionate in terms of purpose: the JACS should inform decisions and lead to action. The scope should be realistic from the outset about the extent of UK interests and capacity to affect and influence change

- proportionate in terms of effort: the JACS should fit the available resources (time, budget, people)

- proportionate in terms of output: the JACS should always result in a concise, usable key findings paper as a primary output. Deeper analysis and longer explanation is good, but only as far as it will be read, discussed, and used

3.2. Scalable approach

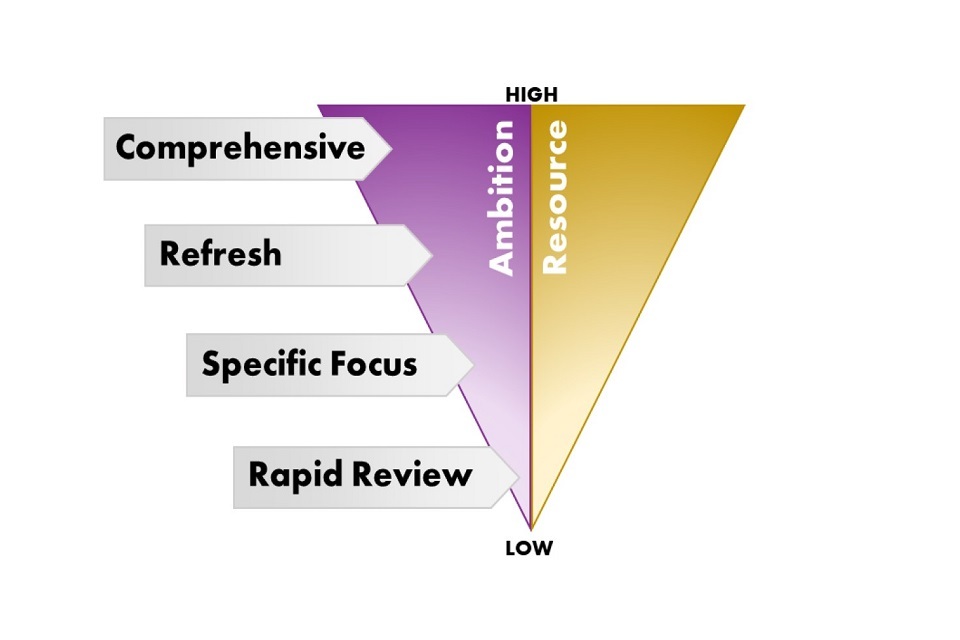

There is no one-size to a JACS but rather a range of scalable options from low to high ambition depending on need, available time, and available resources.

The scale below has 4 illustrative points from low to high ambition, but the intention of introducing a scale is to provide JACS teams the options to moderate the process depending on individual context.

The need should set the level of ambition. Ideally, a higher ambition JACS process will be used wherever there is no comprehensive conflict analysis in place, but this will depend on the specific context, what analysis already exists and how up-to-date it is. Updates to existing processes may use less-intensive processes towards the middle or low end of the scale; eg updating proximate drivers or other changes. Often there is knowledge on the general conflict context, but need for in-depth analysis on key issues such as climate- related drivers which requires only a lighter touch conflict analysis to frame deeper thematic analysis.

Timing will shape scale. A fast-moving context may demand rapid analysis which will by necessity need to be at the lower ambition scale. There are no set periods of time for the process, as it can flex depending on need, but broadly range from around 4-5 months for a fully comprehensive approach, down to a few weeks for a rapid review.

It is also important to consider the resources available. High ambition processes will require higher levels of resource (especially in terms of time spent and stakeholder engagement). Where there is limited funding, time available, or where the team is very small the ambition of the process should also be moderated accordingly.

Whichever option is used, the key elements of senior championing, joint working, external challenge, and clarity of policy and programme objectives apply – as well as use of the core conflict analysis approach.

Comprehensive

The ‘full’ JACS uses a deep analysis of the structural and proximate drivers and a mapping of actors and systems involved in the conflict to draw out as comprehensive a picture as possible for UK policy. It combines extensive and comprehensive insights into both the overarching pressures related to a conflict or conflict system and could also go into granular detail in particular sub-districts, wider regional and transnational dynamics, drivers and implications, and thematic areas of relevance – eg organised crime, climate effects, atrocity risks. A full JACS synthesis draws from a diverse range of experts and data sources to identify key drivers, dynamics, and potential response options.

Undertaking a comprehensive JACS requires dedicating substantial time and resources to gather and integrate different perspectives.

Refresh

A refresh process should be used to provide regular updates to a JACS (generally every year, or every few years depending on the context, but could be more frequently in particularly dynamic contexts).

This requires pre-existing analysis that has comprehensively covered the structural causes of conflict that can be used as a baseline to update. A quick process – literature review and workshop – can be used to establish whether the structural drivers remain consistent and identify the main proximate drivers to focus on. This can be coupled with a gap analysis to identify where additional knowledge could be useful and to determine what perspectives are missing and how to acquire those to augment the primary conflict analysis.

Alternatively, where there is limited capacity – in time or expert resource – but a clear need for joint analysis has been identified a lower ambition ‘Refresh’ process could be used. In this case the JACS would provide broad but shallower analysis of the principal conflict drivers and would need to be tightly bound in its terms

Specific focus

As with the Refresh, this will generally require some existing conflict analysis to use as a baseline. The Specific Focus approach is intended to introduce new knowledge to address gaps in understanding. These could include deep dives on particular geographic areas or thematic dimensions. It may be that there has been a specific change of context from a previous analysis, or a need for an evaluation of a new area eg climate, gender, atrocity risk, regional instability and spillover.

Again, as with the Refresh, a quick process will be needed to establish whether the structural drivers remain consistent and that can identify where the specific gaps are to focus on.

Rapid review

At the low end, existing analysis and resources can be used to develop a picture of the context, which can then be reviewed and challenged or developed in cross-government discussions, to assess how successfully they explain the current conflict dynamics and the potential implications for the UK government.

A Rapid Review can also provide an initial process to bring groups together and identify whether there are gaps that require a deeper analysis when time or resources allow.

At the extreme low end, a minimal approach may simply involve a short workshop to bring together existing knowledge and previous analysis to test for changes in conflict drivers, actor incentives and relationships, and the potential impact or new points of leverage that arise. Even this basic internal exchange of perspectives and debate can update understanding of a conflict, so long as this is taken by a cross-government group, and it may be particularly suitable for a regular update of a JACS in an active conflict phase.

3.3. Gender in conflict

Conflict shapes and is shaped by gender. Men and women experience and contribute to conflict in different ways. Integrating gender within conflict analysis therefore helps us to:

- better tackle the root causes of instability through understanding the gendered causes and drivers of conflict

- better prioritise the form of the UK government response through a more in-depth understanding of the specific needs, capabilities and experiences of women, men, boys, girls and sexual and gender minorities

- recognise and mitigate the risks of policies, programmes or other interventions that may exacerbate the gendered dimensions of conflict, or harm the post-conflict settlement

- build gender equality and peace by ensuring that conflict and post-conflict assistance doesn’t rebuild a gender discriminatory society that contains the seeds of future violence

The JACS process (in all scalable options) should adopt a gender responsive approach to the analysis to more fully understand patterns of behaviours, motivations, beliefs, values and power, and the consequences of these, including on recommendations for action.

The JACS must also consider how conflict is experienced across different populations and stages. At a community level, for example, conflict and associated violence against women and girls (VAWG) often continues after the kinetic stage of a conflict has ended.

If there is not sufficient gender expertise within the JACS team or stakeholders, external expertise should be sought as early as possible. OCSM can provide further information, and there is also provision of support through the Women, Peace and Security (WPS) helpdesk.

Gender considerations should be explicitly mentioned in the ToR in terms of questions for analysis, literature review and research, plans for workshops or discussions, and direct attention in output documents.

For more background information on how gender relates to conflict and security, please see the UK government’s Women Peace and Security National Action Plan 2023 to 2027 on GOV.UK.

Women are often portrayed in conflict situations either as victims of sexual violence, as mothers, or as uncritical advocates for an end to conflict and can often be overlooked in actor analysis. Protection of women and children can be used as a justification, by some state and non-state actors, for military intervention, similarly societal norms around masculinity can play an important role in perpetuating conflict.

In contemporary conflicts, girls and women also take active roles as politicians, spies and high-ranking military commanders, in perpetrating inter-community violence, being active combatants, as well as being active supporters of violent extremist groups.

Women face major challenges in meaningfully and safely participating in formal peace processes and exclusion is often the norm. Their local contributions to peace efforts often go unrecognised as they take place outside of official, high-level forums. In a similar way, consider which other marginalised groups, including men, may be excluded by current gender assumptions.

3.4. Conflict sensitivity

Interventions in conflict settings are never neutral.

Conflict sensitivity is acting with the understanding that any initiative conducted in a contested environment will interact with that environment and that such interaction will have consequences that may have positive or negative effects.

The JACS process and outcomes must be conflict sensitive and should seek to:

- understand the context: how power and resources are divided up and manged between elites in society, dynamics between them, drivers of conflict drivers etc

- understand the interaction between the UK’s engagement and the context: acting to review the conflict sensitivity of existing UK activity

- act upon this understanding in order to avoid negative impacts and maximise positive impacts

As part of this approach, the process should evaluate both HMG activity that addresses the conflict directly, but also wider HMG approaches within the conflict context – those that include eg development, security, and political responses and actors.

The following questions are a guide to help ensure the JACS recommendations are conflict sensitive:

What

- are there recommendations that focus on how the UK government will address conflict drivers identified in the JACS? Do these contain a viable theory of change?

- are there any obvious trade-offs or tensions between different sets of recommendations? For example, between recommendations to support security objectives (including UK security) and those longer-term objectives to promote an inclusive political settlement and sustainable peace. Are these trade-offs articulated and are there recommendations on how they should be managed?

- are there any recommendations that, if enacted, might strengthen the actors or drivers of conflict and increase hostilities or tensions (eg by reinforcing inequalities, strengthening certain elites etc)?

- are any recommendations being made which, while coherent in isolation, might heighten the likelihood of conflict across borders or regions (eg building the strength of 2 opposing security forces, for domestic reasons, which also increases their capacity for conflict)?

Who

- will any of the recommendations lead to conflict actors inadvertently being empowered or disempowered with potentially destabilising consequences?

- will any of the recommendations have an impact on how the UK government is perceived in the context? How might that affect what it is trying to achieve?

- could recommended UK government action or association with groups or individuals make the latter targets for aggression?

Where

- what is the likely impact of the recommended geographical focus of UK government interest on the conflict drivers? For example, is it concentrated in certain geographic areas (urban versus rural, different regions, centre versus periphery)? Could that reinforce grievances or divisions, for example around marginalisation?

How and when

- how might the recommended choice of instruments and partners influence conflict drivers and opportunities for peace and institutional resilience? For example, decisions to provide support inside or outside of government systems, implementation approaches etc

- is there a risk of diversion of resources to pursue conflict-related aims or the potential for reinforcing corruption and patronage?

- is the recommendation time-dependent? Will ceasing activity before the objective is achieved cause more harm?

3.5. Cross-border, regional and transnational dimensions

Conflicts in the 21st century are rarely confined to a single nation-state. A national focus, while necessary in many cases to align with HMG decision-making, can prevent us from analysing and understanding the complex systems and interdependencies that drive and sustain conflict which may be across borders, at the regional, or of a transnational nature.

JACS teams should make connections across countries and regions in neighbouring HMG Posts to identify research questions such as:

- cross border conflict dynamics, and eg analysing centre-periphery dynamics

- regional conflict systems and interconnections

- transnational links, which either drive conflict or provide resilience – or perhaps do both but in different geographies (eg what may be stabilising for one conflict could be destabilising for another)

- impact of global policies like sanctions, international financial system, CT frameworks, migration policy

4. Phase 1: Initiate

4.1. Define scope

The purpose of the initiation phase is to define the scope of the JACS through engaging the appropriate cross-section of stakeholders across government.

After a JACS has been proposed, the JACS Lead should determine which government departments need to be involved and meet with all stakeholders to establish consensus around the requirements, objectives, expected process and scale. Once established, this detail should be clearly articulated in the Terms of Reference (ToR) for the JACS and signed off by the JACS Commissioners.

4.2. Terms of reference

The JACS terms of reference (ToR) should cover the agreements reached between departments on the purpose, scope, scale, resources and timescales. It should also identify a clear policy, strategy, or programmatic question for the process to answer, to guide the analysis. The ToR will provide guidance for the JACS lead throughout the analysis phase, as well as a point of reference for the commissioning team prior to JACS sign-off, when deciding whether the JACS has sufficiently met its objectives.

Care must be taken to ensure that the ToR are realistic in terms of expected outputs for resources committed. Experience has shown that unrealistic ToRs will cause disagreement at time of sign-off. In particular, issues arise when processes are set up in overly general terms to ‘deepen understanding’ and are unable to identify clear implications for the UK. Findings may appear too ‘shallow’ due to overstretch of the analytical team trying to cover too much ground, or recommendations are of limited utility because different stakeholders have different ideas of the objectives. If there are limitations to the resources in terms of available time or people – and there often are – these need to be addressed at the outset and the scope suitably modified.

Gender considerations should be explicitly mentioned in the ToR in terms of questions for analysis, literature review and research, plans for workshops or discussions, and direct attention in output documents.

In brief, the basic structure should cover:

- aim and objectives: how the JACS will be used, including specific sub-objectives, and a clear overarching policy question

- approach and methodology: how the JACS framework will be adapted based on the needs and any time or other resource constraints, as well as the sequential process that will be followed (eg literature review, field research, workshops). There should be clear timelines for each process

- roles and responsibilities: be clear about who has commissioned the JACS, who will lead, who will be responsible for drafting, and what support is to be offered to the JACS team from the relevant departments. The ToR should also identify any external contributions

- costs: any anticipated costs for externally commissioned research, field travel etc

4.3. Commission background research

Unless very limited in time, or very sure of the baseline evidence (eg if doing a refresh of a recent JACS), the JACS Lead should commission background research based on the initial questions identified in the ToR and/or clear gaps known at the outset. This will usually take the form of a literature review or FCDO Research Analyst’s paper, but could also take the form of short research notes from other HMG departments, as relevant.

This initial background research should provide a solid platform for the main analysis. It can distil key issues, providing a starting point for both field research and discussions; key findings can be used to formulate discussion points for use in key informant interviews or workshops with UK government and external partners.

A literature review or research paper should be designed to check assumptions and overcome biases. This should be guided by good research questions, which set clear boundaries as to what should be included and excluded eg:

- define or measure a specific phenomenon: what is the impact of forcible evictions on demographics in a specific location, or how are the protection risks for children changing because of instability (as indicators of changes in level of instability in the context)?

- test a hypothesis or theory: what evidence supports the theory that failure to manage environmental degradation has generated grievances among the rural population and contributed to popular support for anti-government protests?

- compare 2 or more theories: does the evidence favour corruption or environmental degradation as a key driver of conflict?

It may also highlight inconsistencies or gaps in existing knowledge and understanding. Teams may then wish to commission additional, targeted research to address these.

Literature reviews and rapid research notes can also be commissioned through the Knowledge for Development and Diplomacy helpdesk (K4DD).

4.4. Identify key informants

Key informants are knowledgeable individuals who can provide relevant context and information for the analysis. They can also serve as a check on the information obtained from other sources. Key informant interviews (KIIs) are an important way to get valuable insight, and should come from a range of sources.

There is no set formula or quota for the compilation of a KII list; however, consultations should be wide enough to ensure broad information on the conflict context is understood and well documented.

Internal to UK government: specialists from both from Whitehall departments headquarters and at Posts. Additionally, there is value in using KIIs to elicit buy-in to the JACS process and its eventual recommendations.

Key informant interviews with members of the intelligence community should be undertaken where possible. While certain information cannot feed directly into JACS processes due to classification levels, JACS Leads should verify that emerging findings are consistent with intelligence agencies’ assessments where relevant.

External sources: these may include prominent national or international researchers, academics, or individuals from development agencies and non-governmental organisations (NGOs). Key individuals from the private sector may also be useful interviewees. Where possible, engaging individuals who are party to or affected by the conflict is likely to prove beneficial, although careful consideration of the relevant sensitivities is necessary.

It is especially important to get beyond those with whom the UK government engages on a regular basis, as their views are likely to be known and already reflected in analysis. A fresh perspective can be gained by seeking interlocutors in different geographical locations or different government ministries, for example. Consider designing KIIs to provide specific analysis or to address gaps in understanding, such as gender perspectives. A range of ages and genders in KIIs should be consulted and helps to challenge assumptions.

External KIIs can also be particularly useful when seeking to sense-check emerging findings to ensure they are is not at odds with the understanding of external experts or local perceptions. Where there is limited access to external individuals, perception surveys and public polls on issues related to conflict and security, may also provide some insight.

5. Phase 2: Analysis

5.1. Framework of analysis

A JACS should systematically explore the causes of the conflict, the main actors, dynamics and triggers, and existing opportunities to reduce instability. This is the information required to provide a useful analysis of a conflict and instability context and to inform prioritised responses. Busy teams may find it easiest to conduct a series of separate workshops on each aspect of the framework – causes, actors, dynamics, and opportunities – rather than trying to cover all of them in a consolidated one- or 2-day workshop. This approach can work particularly well if the majority of stakeholders are located in one place.

While the depth and ambition of the process may scale up or down, every JACS should follow the following core conflict analysis approach.

What are the causes of conflict and instability?

It is important to understand the historical root causes of a particular conflict, but also to recognise that conflict is dynamic. Analysis should also focus on how these causes have evolved and identify the key drivers currently enabling the conflict. This combination of factors can then be explored to enable appropriate prioritisation and response: what needs to be done to mitigate violent conflict in the short term and what is required to achieve sustainable peace and stability.

Causes exist across security, political, economic and social domains – useful lenses through which they can be analysed. They can emerge as a result of grievance or opportunity and occur across a number of geographic levels, whether local, national, regional or international.

Structural causes (also known as root or underlying causes) are long-term or systemic causes of conflict, which create an environment in which violent conflict can manifest.

Examples include geo-political pressures, deep-rooted social exclusion and demographics, such as a youth bulge in the population.

Proximate causes (also known as immediate causes) are causes that are more recent, change more readily and can accentuate the root causes. They generally require more rapid responses. Examples include small and light weapons proliferation; food insecurity causing population movement; and the discovery of natural resources. The consequences of conflict such as forced displacement, sexual violence and emerging war economies can become proximate drivers of conflict in themselves. For example, significant volumes of displacement can lead to tensions between host communities and incoming populations fleeing from violence.

Examples

| Structural causes | Proximate causes |

|---|---|

| Poverty and inequality | Terrorist attacks |

| Socio-economic grievances | Climate shocks, severe environmental or weather events |

| Exclusionary political settlement and contested elite bargain | Demographic pressures from urban-rural displacement |

Who are the main actors?

Actor mapping identifies conflict actors to understand how and why they are engaging in the conflict, with a view to changing (or reinforcing) the nature of that engagement. Actors to be considered in the context of a JACS include the main individuals, groups or entities that can have an impact on a conflict – negatively or positively. For example, those most capable of driving the violence, or minimising it and resolving it. This should also include organisations that represent or advocate on behalf of particular groups (ie women’s rights organisations). Consider their interests, motivations, power, influence, capability, legitimacy, opportunities, and resources, as well as their vulnerabilities.

Actors may relate to and operate at local, national, regional, or global levels. They can range from those directly contributing to a conflict (eg an insurgent grouping) or those undertaking activities that are enabled as a result of instability, as well as potentially feeding it (eg criminal networks). External actors (including the UK and other international or regional actors) may have significant influence over the direction of travel for conflict-affected countries. It is vital to consider the impact that these actors have on long-term peace and stability, including how these actors perceive external efforts to influence the conflict. Children and young people’s lives are also shaped by conflict and will comprise many of the main actors in the coming years; their rights, needs and protection must therefore be considered and prioritised now.

Examples

Local:

- traditional, community and religious leaders

- civil society organisations

- armed group members

National:

- trade unions

- security forces

- national political leaders

Regional:

- neighbouring governments

- economic and political groupings (EU, ECOWAS, ASEAN etc)

- cross-border ethnic groups

International:

- Donors, multilateral organisations

- international non-governmental organisations (NGOs)

- multinational corporations

What are the triggers to further conflict?

An accurate understanding of conflict triggers – incidents or changes in the situation which may lead to a sudden worsening of levels of conflict or fracturing of peace – can enable timely and effective conflict mitigation. Example conflict triggers can range from the apparent (such as political manipulation of ethnicity around election time) to the unpredictable (such as the self-immolation of Tunisian Mohamed Bouazizi leading to civil unrest and the emergence of the Arab Spring).

Mapping triggers involves identifying the potential for volatility – this could be upcoming activities which could potentially trigger an escalation in the conflict, such as elections, large movements of people, or economic changes; identifying environmental pressures and the likelihood of natural disasters – and whether any of these have been destabilising in the past.

To ensure analysis of triggers does not simply result in an arbitrary list, the triggers must be understood within the wider context, and through their interaction with root and proximate conflict causes, as well as actors impacting on the conflict context. A number of methods can be used to identify potential triggers. In particular, it may be beneficial to examine historical incidences of violence and map the triggers for that violence, and the severity of conflict that followed, to identify any patterns of violence triggered by specific types of incidents or events.

What are the conflict dynamics, key drivers and systems?

Conflict dynamics are the result of the interaction between the structural and proximate causes of the conflict with the conflict actors and their interests.

Understanding conflict dynamics can also reveal overall trends; for example, whether the conflict is intensifying, decreasing or in a situation of stalemate. Understanding trends enables the timing of responses to be improved, to prevent or limit instances of violence.

Trends over time can also be overlaid to highlight or clarify further connections. For example, a structural cause (an exclusionary political settlement) may link to a proximate cause (perceived bias in provision of access to water) and a trigger (a drought) which results in a conflict dynamic: a fractured social contract where the state response is corrupt and leads to increasing violence and exclusion of particular groups.

Analysis of conflict dynamics is a clarifying process which helps to identify the most critical factors and actors driving and maintaining the conflict. The typical outcomes of the first stages of conflict analysis are static lists of causal factors and actors. The volume of information generated can be overwhelming. But not everything identified in the first stages of conflict analysis necessarily ‘matters’. Conflict is not an absence of order, but a dynamic process of establishing a new order. Conflict-affected environments are complex, noisy and messy, and they can be fast-changing.

It is likely that there will be multiple and potentially inter-locking conflict systems at work in a single context. These may manifest differently in distinct geographical locations. Understanding conflict dynamics can also reveal overall trends; for example, whether the conflict is intensifying, decreasing or in a situation of stalemate.

What are the sources of resilience?

Sources of resilience are factors that can restrain conflict from manifesting in violence, or containing violent conflict or instability in some way. By identifying what opportunities there are in the context for de-escalation, and increasing stability and resilience, the JACS can identify relevant entry points for UK government engagement.

It is worthwhile asking why the situation is not worse than it is. This helps to identify the factors that are either restraining conflict from manifesting in violence, or containing violent conflict in some way – for example, limiting its geographical spread. Among a number of factors to consider, it is important to understand a society’s ability and capacity to manage and contain conflict; to address incentives and motivations for violence; to restrict or deny access to weapons, access to illicit funding for violence and other resources; and to constrain opportunistic elites.

It is also worth considering that some resilience factors may, paradoxically, be the same issues that drive conflict and instability – eg where a military-captured political settlement acts to both drive conflict (as a contested elite bargain) and manage or constrain it (where military elites use their influence to arbitrate or broker informal deals between socio-economic and political elites, groups and institutions).

5.2 Determine key findings findings

The key findings should directly answer the questions set out in the ToR. This is not a summary of all of the information gathered as part of the analysis, but the most important points that are relevant to UK interests and the objectives of the JACS.

Findings should flow from the analysis of conflict dynamics, summarising the trends and drawing out potential implications. These implications should focus on the context – ie what does the analysis conclude is happening – rather than the implications for UK government interests and policy, which are explored in the next stage of the JACS process.

Key findings must be agreed cross-departmentally, as they form the foundation for determining the implications for the government and subsequent JACS recommendations. This is also a good point in the process to ‘test’ analysis with external analysts, commentators and researchers to ensure that findings are robust. Ideally this is done through a workshop process with key working-level stakeholders from relevant departments.

6. Phase 3: Utilisation

6.1. Agreement on recommendations

Discussion should be held on the key findings of the analysis, ideally with the JACS Commissioners present, focusing on the key findings of greatest relevance to the UK government. This is best done through a facilitated workshop involving all relevant departments and officials both from London and Post.

Recommendations should be based on the key findings of the analysis, suggesting courses of action to mitigate conflict and instability in line with UK government aims. This is a critical step in the process: it should aim to build a shared understanding amongst key HMG actors. However, it is also an opportunity to surface trade-offs and to challenge established policy and practice. Some teams have found it useful to hold separate discussions on findings before developing recommendations. Alternatively, they can be explored and agreed within the same workshop.

These recommendations should provide insight into the actors, sectors or thematic areas that would benefit from UK engagement. This can support strategy processes or key decision-points such as Ministerial submissions. If programmatic in nature, recommendations can be used to build the case for allocations sought from the ISF and to feed into departmental planning or the development of business plans.

Recommendations should be scrutinised through a number of lenses during their finalisation:

- trade-offs: not all good things come together. Recommendations should be open about difficult trade-offs between different courses of action to mitigate conflict, and/or between those actions and other UK activity or interests

- UK government comparative advantage: this entails focusing on areas in which the UK Government has existing relevant experience, expertise, influence, relationships, capacity, resources or policy commitments etc, or in some cases political interest, relative to other international actors

- policy realities: recommendations must be cognisant of the policy landscape, with current government policy stances reflected in their wording. For example, a recommendation to work with a certain actor group should take into account the policy stance on working with that actor group

- findings with potentially good cost–benefit ratios: recommendations that can catalyse significant change for the resources invested are desirable. Given the strategic focus of the JACS, some recommendations may be wide-ranging, requiring significant resource investment to realise a return

- availability of resources: government resource availability is finite, so recommendations should be realistic. For example, if it is known that the UK government’s programme budget is minimal in a given context (and is likely to remain so); recommendations may need to be more focused on advocacy and diplomacy interventions

- demonstrating the anticipated change: recommendations should be accompanied with short ‘change narratives’ demonstrating how the recommendation is expected to drive the desired change. This not only ensures that recommendations are more accessible to uninformed readers, but also that they can be easily tracked, changed and adapted during refreshes

- conflict sensitivity: JACS recommendations will naturally be formed with positive effects to the conflict context in mind; however, it is equally necessary to interrogate recommendations to ensure that they are not inadvertently causing harm. Recommendations and courses of action suggested as a result of the JACS analysis must be conflict-sensitive, including those that go beyond those that directly respond to the conflict (ie development, political, security)

6.2. Define outputs

Following the information in the Outputs section above, the JACS should now be written up in line with what was the specified in the ToR. At minimum this will be a key findings paper that answers the question(s) set. Other outputs should be annexed to this key findings paper (including eg longer analyses of the conflict dynamics, potential scenarios).

The key findings paper should also include a concise list of key recommendations, each of which is supported by an accompanying change narrative, and an indication of how it links to the JACS key findings. Where possible, recommendations should be prioritised. Recommendations must be signed off by the original JACS Commissioners.

It is also important that the outputs capture any gaps left by the analysis, either where there was insufficient resource or insufficient information to draw conclusions – including where these gaps affect any conclusions. These can be linked to cases for further research and analysis (eg a future Specific Focus) if appropriate.

6.3. What can the JACS be used for?

Following agreement and sign-off of JACS recommendations, there are a number of uses for the jointly agreed analysis moving forward:

- updating NSC or other strategies such as business plans: supports decision-making on the prioritisation of resource on conflict mitigation relative to UK capabilities, capacity and other interests

- informing programme design and delivery: providing analysis-backed rationale for country ODA or ISF allocations sought, in particular thematic or sectoral areas of focus

- steering policy: sense-checking current policy and changing or refining if necessary on the basis of up-to-date analysis, including via Ministerial decision-making

- diplomatic tool: using the analysis as a tool with which to influence international partners and other stakeholders, aligning them with UK government priorities and interests

- conflict or stability tracker baselines: designing indicators that can be used to track changes in the context

- supporting risk management: ensuring risk registers and risk escalation processes reflect the understanding afforded by a JACS, in particular the likelihood and impact of individual risks

- scenario planning: using the analysis and understanding of the context to examine the ramifications of a variety of scenarios, including both changes within the context itself and changes to how the UK government interacts with the context

- conflict sensitivity review: informing a conflict sensitivity review of UK government programme or portfolio activity

-

The perspectives of children and young people are important to understand, however, this must be done in a way that is meaningful, sensitive and follows safeguarding principles. Child-focused civil society actors (UNICEF, Save the Children, World Vision, War Child) and/or FCDO advisors should facilitate this process. Women may be harder to access in some contexts where there are social norms restricting their public participation or interaction with outsiders. Particular steps need to be taken to consider how to access women’s views and perspectives, for example working with local women’s rights leaders or organisations and having a gender balanced review team. ↩