Main report – HTML version

Published 13 November 2020

1. Executive summary

Effective training and careers guidance for frontline or low skilled workers can increase progression, pay, and subsequently, social mobility.[footnote 1] Benefits of a strong progression culture for organisations include increased productivity and growth, higher quality outputs, decreased staff turnover (and recruitment costs) and being a more attractive employer.

Despite these benefits, progression from the frontline within the retail, industrial, and hospitality industries is low. Offering training to the frontline is also less common, and when it is provided and optional, uptake can be low.[footnote 2] Supporting frontline staff to achieve upward social mobility has the potential for positive intergenerational impacts, as children who grow up in more affluent households tend to have better outcomes.

We used a behavioural approach to explore barriers and facilitators to the provision and uptake of training and careers guidance amongst frontline workers in the retail, industrial, and hospitality sectors. We developed an Organisational Practice Model that identifies barriers to desired behaviours and opportunities to intervene for positive change. This report makes recommendations about how the government can support organisations to increase their offer.

1.1 Key barriers to organisations offering training and progression conversations to frontline workers

The most significant barrier was that social mobility was rarely reported to be a priority for organisations in these sectors. Leaders did not see the business case for investing in a strong training and progression culture for frontline staff.

There was generally low engagement with the concept of social mobility. Few leaders in these sectors saw it as a priority or within their remit. Organisations commonly did not see the business case to make investment worthwhile and lacked sight of potential benefits.

These fast-paced sectors are customer and profit-focused. There was a tendency to view frontline staff as replaceable, therefore not worth investing in their progression.

With retail facing a particularly challenging environment even before COVID-19, some organisations did not prioritise investing in staff development at the frontline level. Frontline roles were reported to have high turnover rates.[footnote 3]

Frontline staff in these sectors tended not to see jobs as careers. They often reported having other priorities and were reluctant to take on extra responsibility.

Staff sometimes lacked confidence in their ability to complete training, and they associated progression with added stress. They also had low expectations of these sectors to provide training and access to progression, particularly where there was seen to be a lack of meaningful opportunities. Where opportunities existed, frontline staff were not often supported to take them up alongside other priorities.

Organisations did not work collaboratively and consistently with frontline staff to develop opportunities that were appealing or in an appropriate format.

Training opportunities were more commonly offered to higher-skilled, office-based staff. Some organisations applied the same format to training for frontline workers without consulting about what topics to include and which formats to use. This meant that workers were less likely to engage with the training, the topics were less likely to be aligned to their goals, and the format did not suit their needs and learning styles well.

Channels to communicate training and progression opportunities to frontline staff were not always effective.

Many organisations lacked regular line management meetings giving frontline staff little opportunity to discuss their training needs or aspirations. Some organisations used email or intranet systems to advertise vacancies, which frontline staff did not always use. In some cases, language barriers presented further challenges.

Organisations tended to have a short-term focus. This hindered investment in longer- term gains, such as training staff to retain them, preventing them from realising benefits.

Too little funding was made available for investment in frontline employees and any restructuring that would benefit a training and progression culture was less likely. Some organisations, especially smaller ones, with stronger training and progression cultures, relied on passionate individuals to champion and engender this strong culture. However, they lacked structures to ensure that when individuals left, change would be sustained.

1.2 Key facilitators to organisations offering training and careers guidance to frontline workers

We found that having buy-in from strategic leaders was essential to develop and embed an effective progression culture.

In organisations with a strong progression culture, strategic leaders had chosen to prioritise staff development at all levels, including the frontline, to increase staff satisfaction and retention. Leaders tended to see this as an important part of their company brand and reputation. They also linked it to the quality of their service delivery.

Organisations ensured that the structure enabled access to meaningful and realistic progression opportunities at all levels.

These organisations saw the value in retaining long-serving staff over higher turnover and new starters. They engaged in two-way dialogue with frontline staff to develop appropriate opportunities. They also provided structured support for staff to participate in training and progression in line with their needs and aspirations (for example, line management meetings and stress management).

Organisations had created an environment where it was the norm for frontline staff to expect to have training and career conversations with their managers.

Inductions for new staff set expectations about annual performance reviews and goal setting. Regular team and line management meetings presented the best environment to communicate training and progression opportunities to frontline staff. They used these forums to discuss the value of taking them up and support requirements to do so.

Employers had made a commitment to staff progression. They had embedded within the organisation’s culture that training was a key part of being an employee.

Organisations provided all employees with training logs to record and monitor progress against goals. They ring-fenced a training budget to ensure they could offer development opportunities to staff at all levels. Learning and Development roles were created to ensure accountability to their commitment to staff progression. They communicated this commitment in both internal and external job adverts.

1.3 What does this mean for policymakers?

With increasing focus on adult skills and lifelong learning, government interventions should consider the following steers in sectors with high numbers of frontline staff.

1. Target senior and strategic management to gain buy-in to the business case of investing in staff.

This is the most important step. Organisations need to have a clear vision of what an engaged and motivated workforce can look like and the tangible value this delivers – financially and for the brand. Use case studies and data showing how other organisations like them have benefitted from investing in staff.

2. Demonstrate the value of organisations adding stepping stones to staff structures to create meaningful progression routes.

These include opportunities to access higher pay, so staff consider the organisation to be worth investing time and loyalty. Use case studies to show what structures and progression routes have worked for other organisations like them.

3. Encourage organisations to listen and respond to the needs of frontline staff.

This in turn helps to increase workers’ confidence to progress and fosters loyalty when they see their job as a valued career that requires commitment and engagement. Use evidence to show how other organisations like them have set up staff forums and dedicated Learning and Development staff who listen and act on employee feedback.

4. Invest in support for organisations to increase their offer of training and careers guidance to frontline staff.

For example, training schemes and subsidies, particularly for training that results in a qualification. Incentivise participation in these opportunities and ensure that organisations in these sectors hear about them by communicating through channels they use.

This research also informed a separate piece of research, conducted by Kantar, to design and test interventions to increase the socio-economic diversity and inclusion of the workforce.[footnote 4]

2. Introduction

A key recommendation of the 2017 Taylor Review was for government to support employers to promote and deliver lifelong learning.[footnote 5] Furthermore, SMC’s recent report The Adult Skills Gap highlights that the majority of investment in training comes from employers (82%), with 7% government funding.[footnote 6] However, the report also shows that while the proportion of UK organisations offering vocational training is higher than the EU average, levels are falling. Employer spend per employee and the proportion of employees accessing training and are both below EU levels. Employers’ investment in and offers of training focus on higher-level jobs and higher socio-economic groups – frontline staff and those from disadvantaged backgrounds are relatively neglected.

Upskilling frontline workers via in-work training can enable staff to access higher incomes via progression opportunities, subsequently increasing their social mobility. This is important as this portion of the workforce is predominantly made up of those from lower socio-economic backgrounds.[footnote 7] Supporting frontline staff to achieve upward social mobility has the potential for positive intergenerational impacts, as children who grow up in more affluent households tend to have better outcomes. Benefits of a strong progression culture for organisations include increased productivity and growth, higher quality outputs, decreased staff turnover and recruitment costs, and being a more attractive employer. It can also build employee confidence and permit more innovative uses of this level of the workforce.

Despite these benefits, progression from the frontline within the retail, industrial, and hospitality sectors is low and offering training to the frontline is also less common.[footnote 8] When it is provided and optional, uptake can be low. Lack of employer and employee engagement in lifelong learning places additional strain on existing government funding, designed to plug skills gaps through support schemes such as the National Skills Fund.

We used a behavioural approach to explore and understand barriers and facilitators to the provision and uptake of training and careers guidance by organisations and the frontline in 3 sectors: retail, industrial, and hospitality. This report makes recommendations about how to support organisations to increase this offer.

3. Methodology

The purpose of this research was to identify behavioural insights which could encourage the provision and uptake of in-work training and career guidance around progression for frontline workers. ‘Frontline’ was defined as low-skilled workers with qualifications at Level 2 (GCSE- equivalent) or below.[footnote 9] The research took a multi-stage, mixed-method qualitative approach involving a scoping stage and 10 ethnographic case studies. The research focussed on 3 sectors with low rates of frontline progression: retail, industrial and hospitality. The sample included a range of organisation sizes and geographies.

3.1 Research aims

- Understand what drives employers to offer training and careers guidance to frontline workers, and what prevents this, and to understand how to leverage and overcome these factors to increase incidence.

- Use insights to develop ideas for interventions and ensure they are likely to be affordable, practical, effective, acceptable, safe and equitable (the APEASE criteria).

- Gather views from organisations about 4 interventions and make recommendations for whether and how interventions could be rolled out.[footnote 10]

3.2 Scoping phase

- Policy maker focus group with key stakeholders

- Rapid evidence assessment reviewing 21 articles against the COM-B model[footnote 11]

- 10x 60-min telephone interviews with policy and sector experts and 25x 60-min telephone interviews with managers / HR leads from organisations in 3 sectors

3.3 Primary research

- 10x ethnographic case studies speaking to staff at various levels to learn about their organisational culture around training and progression

- Intervention co-design with stakeholders developing ways to improve progression culture

This research was completed in March 2020 prior to the COVID-19 outbreak – therefore, findings do not reflect this context. Research considerations of COVID-19 are discussed in chapter 8. More information about the methodology is included in the Technical Appendix.

4. Developing the Organisational Practice Model

4.1 Analytical approach

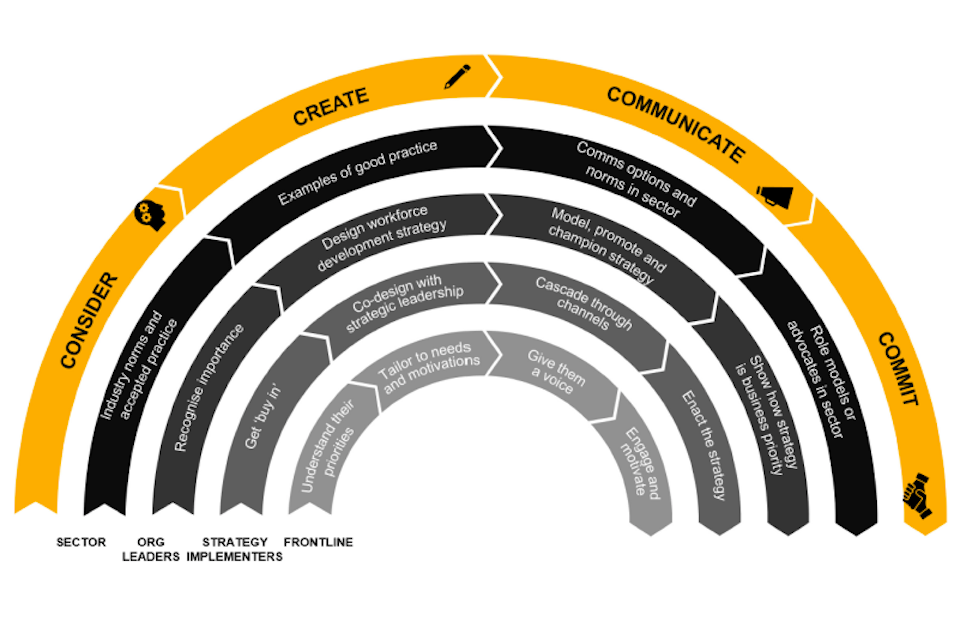

Kantar’s Organisational Practice Model (OPM) is a diagnostic tool looking holistically at organisational practices. It identifies barriers to desired behaviours and opportunities for change. The OPM describes 4 sequential stages that influence behaviours found within organisations (Figure 1):

- Consider the issue

- Create policies and processes to address the issue

- Communicate policies to staff

- Commit to embedding policies and processes

Figure 1. The OPM explains 4 stages that influence organisational behaviour

-

Consider: Recognise the importance of the issue, the benefits of addressing it, and/or the penalties for inaction.

-

Create: Develop policies and processes to address the issue, ensuring these are appealing and accessible to all.

-

Communicate: Communicate these policies and processes so they are clear and motivating throughout the organisation.

-

Commit: Work to create a culture that supports delivery and take-up of the policies and processes across the organisation.

Within each stage, influences are exerted at 4 levels: strategic, middle management, frontline, and the wider sector context. Individuals at different levels within an organisation exert influence at the different stages within the model (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The OPM contains 4 levels explaining where behaviour is influenced

Context: Encompasses the norms, influences and actions of the sector.

Organisation leaders: Encompasses senior management, including strategic HR leads.

Strategy implementer: Includes middle and line managers, and HR staff who implement and deliver strategy.

Frontline: Employees on the receiving end of strategy.

We developed a tailored OPM that outlines drivers of provision and uptake of training and careers guidance within organisations in 3 sectors: industrial, retail and hospitality. The tailored OPM (Figure 3):

- demonstrates the role of different individuals in provision and uptake of in-work training and careers guidance

- acts as a diagnostic tool identifying barriers in these 3 sectors

- provides a way to design targeted interventions at the appropriate level and stage of the journey towards best practice.

The OPM should be read in sequence, starting with the Consider stage, to enable a journey towards best practice.

Figure 3. Organisational Practice Model for in-work training and progression

Figure 3 image description

Figure comprising 5 concentric half circles, each divided into 4 sections.

Outer arc: (heading): CONSIDER

- Arc 2 - SECTOR: Industry norms and accepted practice

- Arc 3 - ORG LEADERS: Recognise importance

- Arc 4 - STRATEGY IMPLEMENTERS: Get ‘buy in’

- Inner arc - FRONTLINE: Understand their priorities

Outer arc: (heading): CREATE

- Arc 2 - SECTOR: Examples of good practice

- Arc 3 - ORG LEADERS: Design workforce development strategy

- Arc 4 - STRATEGY IMPLEMENTERS: Co-design with strategic leadership

- Inner arc - FRONTLINE: Tailor to needs and motivations

Outer arc: (heading): COMMUNICATE

- Arc 2 - SECTOR: Comms options and norms in sector

- Arc 3 - ORG LEADERS: Model, promote and champion strategy

- Arc 4 - STRATEGY IMPLEMENTERS: Cascade through channels

- Inner arc - FRONTLINE: Give them a voice

Outer arc: (heading): COMMIT

- Arc 2 - SECTOR: Role models or advocates in sector

- Arc 3 - ORG LEADERS: Show how strategy is business priority

- Arc 4 - STRATEGY IMPLEMENTERS: Enact the strategy

- Inner arc - FRONTLINE: Engage and motivate

5. Barriers to provision and uptake of in-work training and progression support

This chapter outlines the key barriers to the provision and uptake of in-work training and careers guidance observed in the retail, industrial, and hospitality sectors. It highlights that the most significant blockages were found at the ‘Consider’ stage of the OPM. There was a lack of buy-in from employers on the importance and benefits of progressing frontline workers. Strategic leaders lacked awareness of how a strong training and progression culture could benefit businesses in these sectors, and particularly their profitability. Additionally, sampled frontline workers tended not to consider progression as a priority. Many saw their role as a job rather than a career and reported having other priorities in their lives which they needed the job to work around.

Senior leadership buy-in was critical to ensuring changes were effective and sustained. Therefore, attempting to address barriers at other stages of the OPM would be ineffective without having first overcoming the Consider stage barriers.

After addressing the key barriers at this stage, the chapter explores barriers at the next stages in the OPM.

5.1 Consider the issue

The Consider stage of the OPM explains the extent to which organisations see value in investing in employee progression, and employees consider progression opportunities available to them. Across the 3 sectors, the most significant barriers to a strong training and progression culture were found here, particularly amongst strategic leaders who tended not to have bought-in to the benefits of investing in frontline workers’ training and progression support and opportunities. On the frontline side, the Consider stage is also where the most significant barrier towards taking up opportunities lay. Frontline workers tended not to prioritise their progression, often because they had competing priorities that took up much of their time, energy and resources. This meant they often did not consider progression or see the costs of progressing (such as increased responsibility) as worthwhile.

“There’s no point bringing staff members onto [management development training]” – General Manager, Hotel (50-249 employees)

Businesses’ considerations of training and progression support

The key barrier was a lack of buy-in from senior leadership to the idea that a strong culture of training and progression for frontline workers could benefit the organisation. In some cases, this was partly due to a lack of awareness of the business benefits. In these 3 sectors, profit and productivity are the predominant priorities. Senior leaders in many organisations did not see investing in a strong training and progression culture as an immediate business priority. In some cases, middle managers wanting to champion training and progression faced hurdles to get the investment required. Particular challenges were presented in the retail and food services sectors, where profit margins were marginal and frontline staff could be viewed as easily replaceable. This finding supports literature indicating that these workers are not viewed as ‘valuable assets’.[footnote 12]

“Companies are thinking are they going to survive… I hope retail changes for the better, but I cannot see it.” – Middle Manager, Shoe Shop (250+ employees)

Several organisations in the sample had fast- paced work environments. This meant that time devoted to training or career conversations was considered to be more costly than in other industries. In smaller businesses particularly, the fast-paced environment meant that there was less focus on long-term staff development, and to developing and implementing new policies that would foster a stronger training and progression culture.

Automation has also reduced the need for frontline workers in some organisations in these sectors.[footnote 13] Frontline roles that were not customer-facing (a large proportion of the frontline in industrial organisations) appeared more replaceable to some employers. Although some staff received training to use new equipment, frontline employees’ progression was often not seen as a priority.

Some employers in the sample were less keen to invest in migrant workers’ progression because they thought they were less likely to stay with the organisation long-term. There was a perception among some employers that migrant employees were unlikely to settle in a UK-based frontline job For instance, it was assumed that those who had family abroad would return to them. There was therefore a perception that any investment in their training and progression risked not producing a return for the organisation.

Some migrant frontline workers were overqualified for their role but wanted a temporary job to improve their English before moving onto other professional work. In some cases, organisations were less likely to invest in training and career guidance for these employees, and the workers had a lower incentive to take up opportunities that would facilitate a long-term future in the company or industry.

Within smaller organisations, senior leadership was composed of a few individuals and there was no capacity for a manager to take responsibility for learning, development and progression. Where organisations did have a policy, the remit was usually shared among senior leadership, but this meant that there was little accountability or proactive ownership.

Frontline workers’ considerations of training and progression

From the point of view of frontline workers, a key barrier to the uptake of training and progression opportunities was that they saw their role as a job, rather than a long-term career. Frontline workers reported having other priorities, such as caring and childcare responsibilities, and they wanted a job to earn income around these. Frontline workers had often therefore begun a job with no or low expectations for progression– or the training to facilitate it. In many cases this view was not challenged by organisations or managers.

“[I’m doing this] because it’s very easy to get into this job” – Porter, Hotel (50-249 employees)

Responsibilities outside of work made roles that required higher responsibility seem less feasible and attractive. The roles that frontline staff could progress into often required more employee flexibility, time and engagement. Those with other priorities such as caring responsibilities or health issues sometimes said they felt they were unable to meet additional expectations or thought they might find them too stressful when juggling other priorities, therefore progression was sometimes seen as out of their reach.

Frontline workers often also had low expectations that their employers’ would offer training and fostering progression in the first place. They were therefore less likely to see requesting these opportunities as fruitful or worthwhile.

Some frontline staff saw their career in a different industry and viewed their current job in these sectors as temporary and a means to an end. This was a barrier to their consideration of progression directly from their current role. Even though these workers wanted to move into a different industry, this barrier meant they were missing out on developing transferable skills that could be gained via training and progression which could increase their prospects elsewhere.

Some frontline workers in the case studies reported that negative experiences of education prevented them from engaging with in-work training. Some were nervous about applying for jobs where they would need to undergo an assessment or testing process, potentially alongside colleagues. Others in the sample found the idea of classroom-based learning unappealing. Meanwhile other frontline workers reported feeling nervous about the idea of progressing and working alongside colleagues with additional educational qualification, particularly graduates.

Another barrier for some frontline workers was a lack of awareness or understanding of opportunities available to them. Progression pathways were rarely clear, particularly in smaller organisations where the workplace had a flat structure or where there was a more pronounced division between shop floor and office workers. In such cases, progression was sometimes seen as abnormal, including by middle managers. This fostered a fixed mindset around progression and prohibited some frontline staff from considering it. This finding supports literature indicating that a lack of information, advice and guidance (IAG) regarding career progression is a key barrier for frontline workers.[footnote 14] Lack of knowledge regarding opportunities was also sometimes due to poor communication from more senior staff, which is explored in the Communicate stage.

5.2 Create policies and processes to address the issue

Where senior leadership had bought into the idea of investing in training and progression for frontline staff, there were sometimes barriers to creating training and progression policies that benefited the frontline.

In some of the case studies, separation between frontline and office staff was very pronounced, and this extended to learning and development strategies, which could be completely discrete. Office workers tended to have access to more training and progression opportunities than frontline staff in these sectors.

Where employers had developed training programmes that supported frontline workers to go beyond the expectations of their current job, staff were not always consulted about what topics to include and which formats to use. This meant that workers were less likely to engage with the training, the topics were less likely to be aligned to their goals, and the format did not suit their needs and learning styles well.

Online training was recognised as having advantages and disadvantages. Some organisations provided all or almost all training online, and this was cited as unappealing and more difficult to engage with than face-to-face training by some frontline staff. On the other hand, some frontline staff who did use online training found the added flexibility to be a facilitator to taking up training, as explored in chapter 6. Some small businesses did not have the technology infrastructure to engage with and reap the benefits of online training.

Face-to-face training that required travel presented significant challenges to some frontline workers. Being expected to cover travel expenses on a low wage or having to

arrange cover for other responsibilities – for example, childcare was not feasible for some workers. This finding supports research from interviews with policy experts that shows frontline workers tend to be more geographically constrained than other workers. Similar issues arose when the only realistic progression opportunities available required relocating, such as when office and factory sites were far apart.

“Some people say, ‘I don’t want the 4 days away from my family’ [required for some training].” – Yard Manager, Scrap metal recycler (50-249 employees)

Few organisations in the sample enabled or supported workers to track the training that they had completed. Self-tracking was a significant facilitator for higher engagement in training in organisations in the sample that did use schemes such as training passports – personal paper or electronic booklets where workers kept and a record of upcoming training, along with an explanation of why is was useful and a space to tick off completed sessions.

5.3 Communicate policies to staff

There were organisations where leadership saw the value of a strong progression culture and had developed a training programme for frontline workers. However, barriers at the Communicate stage prevented decisions from becoming actions that benefitted frontline staff.

Some organisations had no one-to-one meetings with frontline staff, and few or no team meetings, particularly within the industrial sector. This limited efforts to build a strong development culture where employees felt able to progress, because time was solely focused on day-to-day tasks. This made it difficult to engage workers in discussions about their longer- term aspirations because there was no forum for, or culture of, seeing a picture that was bigger than daily tasks and issues.

A lack of one-to-one meetings meant that workers did not have the space to confidentially communicate their aspirations to someone who could effect change in the organisation. This also generally meant that the company was reliant on alternative methods such as e-mail to communicate vacancies, training, and progression opportunities. These methods of communication were not regularly engaged with by frontline workers, who cited emails as impersonal and easy to ignore.

“Human discussion is good. If it comes in an email it seems a bit rude, like they don’t really care.” – Front-of-house, Dessert parlour (50-249 employees)

Some organisations with large office workforces used online portals or websites, which were rarely read by frontline staff, particularly if they did not have access to a computer during working hours. There was reluctance among the frontline to use company portals and read emails about training or human resource issues. The lack of engagement was driven by the requirement for significantly different action compared to most frontline work, unlike office work, which tended to involve time at a computer.

A further barrier for some was that not all frontline migrant workers had strong English- language skills. Some organisations had significant workforce populations speaking foreign languages, and they sometimes translated documents or offered English lessons. However, in most instances, this was presented as a significant barrier for these workers to engage with training and progression opportunities like career conversations.

5.4 Commit to embedding policies and processes

Where organisations faced barriers at the Commit stage, this prevented a training and progression offer from embedding effectively across the organisation and among frontline workers.

Organisations were often not engaging with their frontline workers to get bottom-up feedback about any work processes. As with the lack of meetings, this contributed to an unwillingness among the frontline to engage beyond day-to-day tasks. Organisations that lacked such forums for feedback were less likely to have frontline staff who felt they had a voice, and in turn were less likely to see themselves as agents of change. This prevented them from seeing how progression could benefit them and did not leave them feeling motivated to engage.

“People don’t always feel they can ask about another side of the business. They are in their role and don’t necessarily see it as an option to request training on something else.” – Middle Manager, Retail warehouse (50-249 employees)

Related to the lack of buy-in to the idea of investing in training and progression opportunities, Boards and finance leaders within companies tended to have a short-term focus. This hindered investment in longer-term gains, such as training staff to retain them. Therefore, even if senior managers bought in to the value to the organisation of training and progression for the frontline, they said it was difficult to convince Board members of this.

Consequently, too little funding was freed up for investment in this area and any restructuring that would benefit a training and progression culture was less likely.

Finally, some organisations, especially smaller ones, which had relatively strong training and progression cultures, relied on passionate individuals to champion and engender this strong culture. However, a number of these companies lacked structures to ensure that when certain individuals left, change would be sustained.

Case study: School catering department (1-49 employees)

A school catering department that does not have a strong culture of training and progression. Progression occurs based on the motivation of the individual with many satisfied doing their current jobs and not motivated to pursue training and development opportunities.

Training and progression summary:

- In-work training tends to be mandatory formal and on-the-job training – for example, health and safety and food hygiene.

- There is scope for training beyond their everyday role (for example, opportunities for apprenticeships or Teaching Assistant training), but typically individuals would need to ask for it rather than there being a training policy or suite/portal of training on offer.

- Training is communicated in wider team meetings (every 6 weeks/once every half term).

Key areas of good practice:

- There is a culture of progression and development beyond kitchen roles – for example, 2 kitchen staff are undertaking Teaching Assistant training at the school.

Areas for improvement:

- There are no formal career progression or personal development structures in place. Any progression “success” stories are ad hoc and motivated by the individual rather than a formal progression policy/pathway.

- Time is a significant barrier and meetings focus on the everyday running of kitchen rather than wider staff goals.

- There are currently no formal one-to-one meetings in place. One suggestion from staff was that a specialist training provider could come in to discuss options with team members.

- Communication is not consistent, and all levels felt opportunities needed to be discussed more frequently and be more visible, for example, via a training portal.

“There is individual training that they will give you if you push for it” – Frontline worker

6. Facilitating provision and uptake of in-work training and progression

This chapter outlines the key facilitators enabling the provision and uptake of in-work training and careers guidance observed in the 3 sectors. It highlights that attitude shifts at the Consider stage of the OPM by both strategic leaders and frontline staff were key to driving change. Whilst there were significant barriers observed in these sectors, some organisations had recognised the benefits of offering training and careers guidance to frontline staff, for example higher quality outputs and reduced turnover, and had developed cultures that supported frontline staff to flourish and progress. In these cases, frontline workers reported being more engaged and invested in their organisations because support provided was aligned to their needs and aspirations.

6.1 Consider the issue

A key facilitator within the Consider stage was having buy-in to training and careers guidance from strategic leads. This was key to driving change across the organisation. Having a clear business case was critical for gaining strategic buy-in and securing commitment to the provision of training and progression opportunities. There were organisations who had identified and considered the value of offering training and progression, responding to factors affecting the organisation including high staff turnover, inconsistencies in working practices and variable standards of products or services. To address these issues, organisations had consulted directly with frontline staff and listened to their feedback. They were then able to consider how they could implement approaches that would benefit the organisation overall as well as their employees.

“The more you invest in people, the more likely they are to invest in you… you look after your people, they look after your customers, that brings revenue in.” – Senior Manager, Utilities company (250+ employees)

A further facilitator was understanding the priorities of both the organisation and frontline staff. Opportunities that addressed staff priorities or interests led to increased engagement. For example, a small construction company recognised that their staff had interests in different specialisms. Therefore, they were able to ensure staff received training relevant to their interests, which helped expand the capabilities and resources of the organisation – they had more staff able to deal with a range of requirements. As a result of the training, employees felt valued, listened to and appreciative that they were able to put the skills to use.

“I want to work in carpentry, and I’ve been really supported to focus on that.” – Front line worker, Construction company (1-49 employees)

6.2 Create policies and processes to address the issue

Reviewing structures and ways of working helped organisations create meaningful routes for progression and specialisation to engage frontline staff with training and guidance. In some organisations, this involved creating more diverse roles, adding layers for employees to move into or supporting them to work in different locations. Examples included having staff with additional management responsibilities or offering the option to relocate to the same role at a different store. Where there were opportunities to progress into, staff saw greater value in training and guidance as it was linked to recognition and reward. They were more inclined to go beyond minimum role requirements and some managers felt this built trust and loyalty with the organisation. This approach was seen within a supermarket chain. They recognised that staff were feeling disengaged and dissatisfied and staff turnover was high. They explored ways to create more opportunities, both via promotion and lateral transfers.

Relocating to a different store exposed staff to different management, responsibilities, and colleagues. This helped to stimulate engagement and for staff to feel they were facing new challenges.

“Staff can be moved sideways to different areas. People tend to feel happy about being moved and some see it as progression. I tell staff that working in different stores is very healthy for them, because they get more experience, work for different people and learn from others” – Area Manager, National supermarket chain (250+ employees)

Creating training opportunities that staff were supported to attend resulted in higher engagement. This was achieved by allocating time during staff shifts to complete training. Employees who faced challenges participating in training outside of working hours (for example, due to personal commitments or for training that required travel) were able to attend. This was seen within a large utilities company which dedicated a training day for each team every 8 weeks, which demonstrated its commitment to the investment that it was viewed as a worthwhile use of paid time and ensured inclusivity of all staff.

6.3 Communicate policies to staff

A key way of facilitating uptake of training and careers guidance was to communicate and promote opportunities in team and line management meetings. Managers found that these meetings offered a dedicated space to discuss training and progression opportunities and the benefits of participating. As opportunities comprised both upwards and sideways moves, face to face meetings helped to communicate the value of gaining new experiences –

even if they were not promotions. Organisations found discussing these topics in dedicated spaces, such as line management, had more cut through than e-mails or noticeboard announcements, which were passive and easily ignored by staff. Some managers found discussing sideways moves in one-to-one line management meetings helpful to directly challenge perceptions that progression was not available or that training was not worthwhile.

“It is important to communicate and set up targets together. If you don’t talk to employees and just let them work, they’ll lose interest.” – General Manager, International sandwich and coffee shop chain (250+ employees)

Clearly communicating details about training opportunities, such as benefits, requirements and expectations, increased engagement with frontline staff. Clear messages, such as whether the company would pay and whether it was mandatory to attend, increases engagement. A fencing company reported that whenever they required their employees to attend training, they were upfront about when the training was and whether staff would be paid over-time or given time off in lieu for attending.

“There are quite a lot of people in the business who started out driving cars and who are now in quite high positions.” – HR Manager, Automotive (250+ employees)

Regular performance reviews and goal setting meetings supported progression goals. Organisations supported and monitored progress towards goals via training attendance. Goals helped give employees tangible steps to work towards, increasing engagement and motivation. This was seen in a large automotive organisation who required all employees to have personal development plans in addition to their annual appraisal.

Inducting new joiners presented an opportunity to clearly communicate an

organisation’s commitment to frontline staff training and progression. Requiring all staff to complete training upon joining set a precedent of how training was viewed and valued within the organisation. This was seen in a number of organisations, including an international sandwich and coffee chain and a supermarket chain. Both organisations had rigorous processes in place, which included extensive induction training programmes that all new employees were required to complete.

“The organisation is changing for the better – it’s empowering staff and saying they have potential and can have a good job. It makes people want to progress more.” – Store Manager, National supermarket chain (250+ employees)

6.4 Commit to embedding policies and processes

Establishing an environment where training was a key part of being an employee helped to embed it within the organisation’s culture. Demonstrating a willingness to invest in frontline staff helped them to feel valued and motivated. It built their trust that there were opportunities to progress into if they wished and to put skills they had developed into practice within a supportive environment. There were also benefits for the organisation overall. Employees were ‘upskilled’ so could take on more responsibility, and there was greater staff retention, which meant less resources required for recruitment processes. Ensuring that all employees had access to comprehensive training across multiple areas also allowed for flexibility if there was need to cover shifts at short notice. This helped business continuity and minimised disruption. An example of this was seen at an international sandwich and coffee chain. The importance placed upon training was demonstrated at hiring, with all new starters completing mandatory training. Training was then continually available and required throughout, with employees attending mandatory refresher courses and training on new legislation changes.

“If you give the right training to a team member, the team member will stay with you forever.” – General Manager, International sandwich and coffee shop chain (250+ employees)

Providing employees with training logs or passports further embedded this commitment to continuous training and development. Logs gave employees accountability for their learning and targets to work towards as well as records of achievement. This was evidenced by a medium-sized manufacturing company who operated a points-based training system. Different courses had different points and reaching a certain number meant employees were able to apply for roles or take new courses. Employees had access to a system where they could track their points and monitor their progression.

“We have a flexible, leader-led approach. Employees can decide where their skill shortages are and pick a course. They get points for attending training courses” – HR Manager, Fencing company (50-249 employees)

Ringfencing a budget guaranteed funding to spend on training and enabled it to be offered during working hours, maximising uptake. This was practised by a fencing company, who required employees to regularly attend mandatory training sessions. This upskilled employees and the organisation took on more business as a result.

“The more people that are trained, the more jobs you can fill.” – HR Manager, Fencing company (50-249 employees)

Creating specific learning and development roles helped to embed training within the culture, for example, establishing mentoring roles throughout organisations. Mentees worked with their mentor to identify specific skill gaps and how to address them. This was an effective approach seen within a large utilities company. Mentors helped more junior staff to develop their softer skills or to familiarise themselves with a new skill entirely. This built confidence in junior staff and gave them a direct route through which they could ask for specific training or support.

There were opportunities to make the organisation’s commitment to training and progression public, both internally and externally. This was done in both internal and external job adverts. Senior management also held targeted ‘feedback sessions’ where they listened to staff views, including areas for further development. These steps fed into strategic aspirations to be a ‘destination employer’ to support recruitment and retention. This approach was seen in a local branch of a national supermarket chain that had a strong standing in the community. They held regular sessions between frontline staff and senior management to hear any grievances. Managers thought that this commitment contributed to high staff retention rates.

Case study: Supermarket chain (250+ employees)

The chain’s culture nurtures the progression of its frontline staff. Senior leaders feel this is important to the company’s brand, and this attitude is evident in the structured, well-communicated training programmes it provides to help its staff progress. It also offers opportunities to work in different branches, which exposes employees to further career opportunities.

Training and progression summary:

- Formal progression routes are in place and are well advertised to employees:

- Boost modules – mix of face-to-face and online training on how to upskill to the next level.

- Excellence Programme - paid training that focuses on softer skills such as leadership.

Key areas of good practice:

- There are opportunities for sideways moves – store managers are relocated to another store every few years as standard. This normalises expectations of switching roles and progressing within the organisation.

- The organisation listens to its employees and values their opinions – they have a policy specifically around listening to opinions and taking action to fix any issues.

- Training programmes are well advertised to employees via notice boards and during reviews.

Areas for improvement:

- Opportunities for progression are dependent upon how much individual store managers prioritise training and investing in staff, which means there could be variation across stores in the chain.

- Many staff are only willing to progress so far (to store manager, but not to area manager), which seems to be down to a lack of confidence. The organisation could potentially be doing more to help staff feel prepared for an upwards move, such as stress management training and more regular feedback.

“There’s now more opportunities to progress in house from in store. HR has changed its approach at looking at pathways for progression.” – Store Manager

7. Intervention approaches

Behavioural tools were leveraged with the insights on the barriers and facilitators to codesign an approach that would most effectively drive organisational change. We found that 4 sequential steps are required to create and embed a culture that supports and normalises the provision and uptake of training and careers guidance for frontline workers in the retail, hospitality and industrial sectors. The sequencing of these steps is important to the success of interventions and organisations should consider each in turn.

7.1 Step 1 – Gain buy-in from strategic leaders

The first step is to secure buy-in from strategic leaders within organisations across these sectors. Demonstrating to strategic leaders that there is value to the business in providing in-work training and careers guidance will help to ensure it is given priority and made sustainable. Strategic leaders will need to be presented with a strong and compelling business case to justify the investment. A case would be strengthened by up-to-date data and evidence, particularly relating to other organisations within their sector.

Given the need for investment and potentially changes to the organisational structure, any attempts to change the culture without strategic buy-in may falter. For many organisations, the benefits of in-work training and progression were not obvious or well known. It is therefore important to understand that first there must be investment, and results and changes may take time to materialise. An upfront long-term commitment should therefore be secured in preparation of change.

7.2 Step 2 – Create meaningful career progression opportunities

The second step is to review company structures and ways of working to create meaningful career progression opportunities for frontline staff. It is important to understand why processes might need to be changed so they can be addressed appropriately. For example, an organisation may have a very flat structure with limited progression routes. Lack of progression opportunities can make training and careers guidance less meaningful when there are no positions or specialist areas to aspire to. This can lead to high turnover and a disengaged workforce. Moving away from a flat structure would create more opportunities. Training should also be provided to support employees to reach a higher position. This would both upskill staff and demonstrate a commitment to continually investing in employees.

7.3 Step 3 – Engage in two-way conversation with frontline employees

The third step is to engage and build trust with frontline employees. This could be done by actively listening to their feedback on aspirations and concerns they have about progressing. An organisation that is supportive of their employees is more likely to see a return on any investment. It is important to continually engage with employees and to recognise that an individual’s priorities may change. Whilst an employee may express little interest in training or progression at one point in time due to other commitments, priorities or confidence level, this may evolve over time. Regular check-ins should be standard procedure as well as fostering a culture where employees feel empowered to ask for guidance and help if needed.

7.4 Step 4 – Embed measures and commit to maintaining them

These steps should be supported by the fourth step – to embed measures throughout the business that support individuals to progress at their own pace. An employer should offer a suite of training and progression options for staff at different levels. It is important to recognise that each employee has their own priorities, commitments and learning needs.

Suggested interventions

These interventions, designed in collaboration with policy experts, have potential to facilitate action.[footnote 15] However, they target step one, which is the most significant barrier to overcome:

- Maturity assessment – an online tool assessing an organisation’s training and progression culture and identify priority areas to focus on to improve (including links to the Social Mobility Commission Employers’ Toolkit)[footnote 16]

- Case studies – examples of how organisations like theirs have successfully overcome similar challenges to the benefit of the business and staff

- Consultancy – a service embedding an expert in the organisation to assess their training and progression culture, identify priority areas to improve, and support them to execute changes

- Accreditation – a certification identifying employers as displaying best practice to build and sustain a strong training and progression culture for frontline staff.

These interventions were tested in a broader piece of research, conducted by Kantar, to understand how to increase the socio-economic diversity and inclusion of the workplace.[footnote 17]

8. Reflections on COVID-19 context

Since completing fieldwork for this research in March 2020, the UK’s employment landscape has changed as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Here we discuss considerations of the research findings given the changed context which has particularly impacted the retail, industrial and hospitality sectors as they rely on onsite working.

8.1 Challenges

There is high risk to job security as organisations in some sectors are forced to make cost- savings to maintain liquidity. This could have a significant impact on how much leaders are willing or able to prioritise resources to upskill frontline staff. Budgets for training and staff development could be deprioritised as funding is diverted to delivering the core business, maintaining revenue and retaining staff roles.

Therefore, it is more important than ever that the business case for why organisations should prioritise training for frontline staff is clear. Mapping out both short- and long-term benefits could help them to buy into the commitment by seeing both immediate results and potential positive outcomes for the future. The business case must be accompanied with practical examples of low-cost ‘quick wins’ to encourage organisations to take the first step without being deterred by larger steps in the journey. Case studies that demonstrate how other similar organisations have taken action during challenging financial periods could be impactful.

8.2 Facilitators

The COVID-19 outbreak highlighted the importance of frontline roles to sustain services and product availability. Organisations may have a heightened awareness of the key role their frontline staff play to enable business continuity. As a result, employers may be more likely to see the business case to invest in them via training and progression opportunities. Furthermore, job insecurity may mean that frontline workers are more interested in developing and gaining new skills.

Physical restrictions caused by COVID-19 have made online a more accessible channel for many. Online learning is more mainstream and could be leveraged to offer training for lower costs that is more flexible and without the negative ‘classroom’ associations.

9. Additional case studies

9.1 Organisations with developing progression cultures

Case study: Waste management company (50-249 employees)

A family-run organisation that does not offer many opportunities for progression or training for frontline workers outside their existing role. Staff feel the organisation is resistant to change and is fixed in its attitude that there is little value to training employees beyond their role.

Training and progression summary:

- Mandatory training is offered in (for example) Health and Safety training. IBOSH health and safety training involves 4 days away. Compliance training is also offered, which can help workers progress to managerial positions.

- Optional training is offered to become a fire warden/first aider and cross-training to use cranes and forklifts is offered when someone extra is needed.

- If a supervisor leaves, a manager might suggest someone to be the new supervisor and will train them as needed. However, these positions do not often open up and are a big step up in responsibility.

Areas for improvement:

- There are few opportunities for progression and more senior positions rarely open up, so staff feel stuck in their role.

- The company has a high turnover of staff, many of which are from migrant families who intend to return home after a year or 2 and so have no interest in progressing.

- The current yard manager does not meet staff as a team or in one-to-ones. As a result, staff do not feel that he is approachable and do not talk about their goals.

Regarding one-to-ones “[It would] probably be quite a good thing in some ways - you could say what you think would work better.” – Frontline worker

Case study: Shoe shop (250+ employees)

The organisation’s focus is on keeping finances stable rather than investing in employees, an approach that seems typical of retail. Employees feel the sector lacks credibility and prestige, and that this could be overcome by introducing a formal retail qualification.

Training and progression summary:

- New joiners are given a 12-page training pack to read when they start work, which was described as “very basic”. New staff also shadow another worker for their first 2 weeks.

- Management training courses are offered but otherwise training is ad-hoc.

- There is no formal line management system and any conversations about progression happen informally.

Key areas of good practice:

- There has been progression in store, with the deputy manager and store manager both progressing up to their current roles.

- The store manager is interested in staff welfare and proactively tries to develop people who he thinks have potential when vacancies are available.

Areas for improvement:

- There is a lack of interest in providing any formal training as the company is focussed on their financial situation and the costs of providing such training are perceived to be too high. They are interested in the idea of a retail NVQ and think this would bring credibility and prestige to the sector – but are not aware of any available opportunities.

- Confidence of frontline staff is another barrier, as they are nervous about progressing into supervisor roles.

“You just get trained by your manager and hopefully you get good by the end of it.” Frontline worker

9.2 Organisations with more developed progression cultures

Case study: Construction company (1-49 employees)

A small construction company which seems to be doing things differently to other organisations in the sector, investing more in developing its employees. In particular, they take on a lot of apprentices who are qualifying in a specific skill.

Training and progression summary:

- They have several apprentices who are all qualifying or are qualified in a specific skill. Other training is on the job depending on what the business needs at the time.

- Staff have 6-monthly meetings (or 3-monthly if they are an apprentice) with their line manager or overall boss to discuss how happy they are in the job, what they would like to do next and progression opportunities.

Key areas of good practice:

- The head of the company is very socially motivated towards training and developing his staff. He wants to offer opportunities to young people in order to improve their prospects and seems to personally care about developing staff.

- For a small organisation, there are good structures in place for discussing career development opportunities. There is a sense that being a smaller organisation is a facilitator, as they can be more flexible with how their time is spent, rather than larger firms who are sticking to very tight timescales.

Areas for improvement:

- “Careers” are not associated with the construction industry, and the staff at this construction company did not identify with having “a career”. They see their progression as being able to access a higher wage, or possibly becoming self-employed. The word ‘career’ made them think of office jobs and big firms rather than their current industry.

10. About the Commission

The Social Mobility Commission is an independent advisory non-departmental public body established under the Life Chances Act 2010 as modified by the Welfare Reform and Work Act 2016. It has a duty to assess progress in improving social mobility in the UK and to promote social mobility in England.

The Commission board comprises:

- Sandra Wallace, Interim Co-Chair, Joint Managing Director Europe at DLA Piper

- Steven Cooper, Interim Co-Chair, Chief Executive Officer, C. Hoare & Co

- Alastair da Costa, Chair of Capital City College Group

- Farrah Storr, Editor-in-chief, Elle

- Harvey Matthewson, Aviation Activity Officer at Aerobility and Volunteer

- Jessica Oghenegweke, Presenter, BBC Earth Kids

- Jody Walker, Senior Vice President at TJX Europe (TK Maxx and Home Sense in the UK)

- Liz Williams, Chief Executive Officer of Futuredotnow

- Pippa Dunn, Founder of Broody, helping entrepreneurs and start ups

- Saeed Atcha, Chief Executive Officer of Youth Leads UK

- Sam Friedman, Associate Professor in Sociology at London School of Economics

- Sammy Wright, Vice Principal of Southmoor Academy, Sunderland

11. About Kantar Public Division

Kantar Public Division specialises in social research. Our specialists provide evidence and capability-building for governments and multilateral organisations to deliver better public policies and communications. https://www.kantar.com/

-

BEIS, Good work: the Taylor review of modern working practices, 2017 ↩

-

Eurostat, Education and training database, accessed November 2020 ↩

-

This research was completed in March 2020 prior to the COVID-19 outbreak – therefore, findings do not reflect contextual factors related to COVID-19. ↩

-

Social Mobility Commission, Interventions to improve socio-economic diversity and inclusion in the workplace, 2020 ↩

-

BEIS, Good work: the Taylor review of modern working practices, 2017 ↩

-

Social Mobility Commission, Adult skills gap and the falling investment in adults with low qualifications, 2019 ↩

-

Social Mobility Commission, State of the Nation 2018-19, 2019 ↩

-

Eurostat, Education and training database, accessed November 2020 ↩

-

Grades 4-9 / A*-C at GCSE, intermediate apprenticeship, Level 2 NVQ ↩

-

Social Mobility Commission, Interventions to improve socio-economic diversity and inclusion in the workplace, 2020 ↩

-

COM-B considers the presence of 3 factors - capability, opportunity and motivation - to influence behaviour. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3096582/ ↩

-

Green, A., Sissons, P., Qamar, A., and Broughton, B., Raising productivity in low-wage sectors and reducing poverty. London: Joseph Rowntree Foundation, 2018 ↩

-

Social Mobility Commission, State of the Nation 2018-19, 2019 ↩

-

Green, A., Sissons, P., and Lee, N., Harnessing Growth Sectors for Poverty Reduction: The Role of Policy. Public Policy Institute for Wales, (2017) ↩

-

Refer to the accompanying PowerPoint slide pack, which contains a fuller list of intervention ideas explored. ↩

-

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/863502/Employers_Toolkit.pdf ↩

-

Social Mobility Commission, Interventions to improve socio-economic diversity and inclusion in the workplace, 2020 ↩