Improving families’ lives: annual report of the Troubled Families Programme 2020 to 2021

Updated 29 March 2021

Applies to England

Including further findings of the national evaluation of the Troubled Families Programme

Presented to Parliament pursuant to Section (3) 6 of the Welfare Reform and Work Act 2016

Foreword – Eddie Hughes MP

COVID-19 has been an unprecedented challenge and people have shown great resilience and determination to fight this dreadful virus. The pandemic has reminded us all of the importance of families and communities in supporting each other.

Whether it was a phone call to our relative shielding alone or supporting our children’s education at home, our families were who many of us turned to first in order to give and receive help, getting us through difficult moments over the last year. Strong families are the foundation of our society and it’s therefore right that we are supporting our most vulnerable families to grow stronger.

COVID-19 has been tough for all families and in particular those who were already vulnerable before the pandemic. I am proud that the Troubled Families Programme played an important role in supporting those who needed some extra help at this time. This built on the programme’s established role in supporting families with multiple and complex needs across domestic abuse, unemployment, health, school attendance and other interconnected issues. Keyworkers and other local partners have shown tenacity and ingenuity, pioneering remote and virtual ways of supporting families and carrying out safe home visits to those in need. I am delighted that this report is able to shine a light on some of this fantastic work.

As we look to recover and build back better I was pleased that we were able to announce further funding for the programme. Up to £165m of additional funding was announced at the 2020 Spending Round. The programme has a key role to play in supporting families to recover from the pandemic, making sure we get our children back to school, that we help those who have lost their jobs get back to work, that we protect mental health and that we stop domestic abuse. This report sets out some excellent examples of great work to reach these goals. Despite the challenges of the last year, the programme hit a milestone of reaching 400,000 successful family outcomes since it began.

We know that we mustn’t stand still, the work continues to adapt and improve services. Our 2019 manifesto committed to improving the Troubled Families Programme. Our response to COVID-19 has shown us how we can transform services rapidly and work together across boundaries to support those in need. We can take forward this spirit to continue to improve. I look forward to working with Troubled Families Programme services as a Minister and to visiting teams across the country as soon as it is possible to do so.

Eddie Hughes

Minister for the Troubled Families Programme

Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government

Executive summary

The programme will begin a new phase in 2021-22 with up to £165 million of funding announced in the 2020 Spending Round. Funding for future years will be determined at 2021 Spending Review. Allocations have been made to local authorities across the country. Up to £165m is available dependent on performance.

The programme has been a key part of the response to COVID-19 by supporting families with immediate needs. The programme will play an important role in the recovery, supporting families with longer term impacts of the pandemic such as unemployment and mental ill health. Troubled Families Programme funded services supported families during lockdown by providing access to food and equipment for home learning. Services also adapted to social distancing rules by using virtual engagement where possible and prioritising need.

The programme had achieved a total of 401,719 successful family outcomes as of January 2021. The programme continues to deliver significant and sustained outcomes with families despite the difficult circumstances in 2020-2021.

Each local area has been audited twice during the programme, giving us confidence in the validity of Payment by Results claims. A high proportion (92%) of payment by results claims submitted by local areas were found to be valid in our spotcheck audit process.

An independent evaluation of the Supporting Families Against Youth Crime fund shows that the fund improved the provision of local services addressing youth crime. The fund supported a number of innovative approaches in 21 local areas. Local areas reported that whole family interventions, role model based and mentoring interventions were successful.

New data sharing guidance was published to support areas with information governance. It encourages areas to consider using the Digital Economy Act as a legal gateway for sharing data and provides guidance on data protection legislation.

A data maturity survey shows that some areas have achieved advanced use of data relating to their families but most areas had much more basic systems and basic software. The most advanced local areas are able to identify need earlier and build a fuller picture of the help a family needs. The programme will continue to support the less advanced areas to improve.

Staff surveys showed consistent support for the programme from local teams. 95% of Troubled Families Coordinators agree that the programme is effective at achieving whole family working and 89% agree it’s successful at achieving long term change for families.

New research has been commissioned which looks at what is most effective practice for achieving outcomes with different families. Fieldwork is underway and the research should report later in the year.

Troubled Families Programme overview

The Troubled Families Programme supports targeted interventions for families experiencing multiple problems including domestic abuse, crime and antisocial behaviour, poor school attendance, unemployment, mental and physical health and children in need of help and protection. Services are managed by upper tier local authorities in England working together with a range of partner organisations. The four key principles of the Troubled Families Programme are outlined below:

- Whole family working – Problems experienced by family members are often interconnected. A keyworker builds a relationship with the whole family. They complete one assessment for the whole family, coordinate services around a single plan and offer support and challenge.

- Multi-agency working – Multiple professional agencies cooperate and share information in a joined-up approach to supporting families and protecting children.

- Focus on outcomes and data – The programme requires areas to establish an outcomes framework across multiple services and encourages them to achieve those outcomes by tracking them over time.

- Earlier intervention - The programme funds early help services, i.e, services that support families requiring a lower level of intervention than statutory services such as children’s social care or the criminal justice system. It encourages services to intervene to address problems before they reach crisis point.

National programme developments

In the last year the national team has responded to the COVID-19 pandemic, announced and allocated further funding through the one-year 2020 Spending Round, continued to support areas use of data and integration of services and built the evidence base around family support services.

New funding for 2021-2022

The government has invested up to an additional £165m for the 2021-2022 phase of the programme. This was announced at the 2020 Spending Round, enabling the programme to continue to deliver until March 2022. This will enable local areas to sustain and improve their local programmes at this critical time. Funding allocations were confirmed to local authorities in January 2021. Decisions on funding beyond 2021-2022 will be taken at the 2021 Spending Review.

Supporting families through COVID-19

The national team worked closely with local areas to monitor the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on vulnerable families and children. The team interviewed around 100 local areas and used this intelligence to brief other government departments to improve their understanding of the local context.

The national team organised a series of webinars which were attended by hundreds of local authority staff. Webinar themes included good practice in virtual engagement methods with families; young people and youth crime; parental conflict; school attendance; and a digital showcase event on better use of data. Feedback from local areas was positive and we hope to run similar events in the future.

These webinars supported the programme in three important ways during the pandemic:

- They facilitated the sharing of best practice between local areas on supporting families through the pandemic.

- They enabled other government departments and voluntary and community sector organisations to provide guidance to local authorities on tackling emerging risks resulting from the pandemic.

- They enabled the national team to gather intelligence on the impact of the virus from local areas.

The Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG) will continue to support local areas to adapt their services during the pandemic, to monitor the longer-term impacts on vulnerable families and on services and to consider what elements of practice developed during the pandemic could be useful when social distancing is no longer required.

The national team responded to the feedback from local areas that they needed extra resource to cope with the pandemic by moving some funding from the Payment by Results system to upfront funding. The team also introduced temporary adjustments to the Payment by Results system to adapt to school closures and the furlough scheme. This is explained in more detail in the “Successful family outcomes for 2020-2021” section.

Providing evidence of what works

The programme has commissioned new research to look at what aspects of practice are most effective in achieving positive outcomes for families i.e, what works. This is qualitative research (interviews) with around 10 local areas. An independent research organisation, Kantar, has been appointed to lead the research and fieldwork has already begun. The national evaluation has provided evidence of positive impacts on outcomes for the programme as a whole. However, this new research will go into greater detail about what specific approaches and interventions are most effective. Findings from this new research will be shared with local areas to inform good practice and support the development of the national programme.

Using data to inform service delivery

The national team has been providing areas with dashboards on performance for some years now. This presents Payment by Results data to local areas and enables them to benchmark their performance. This year we have developed this further by including analysis of evaluation data from the national impact study in these. Local areas can therefore see their trends on key outcomes such as children in need and looked after children. All data is anonymised and looks at trends in that area. This is intended to support local areas to monitor their own performance.

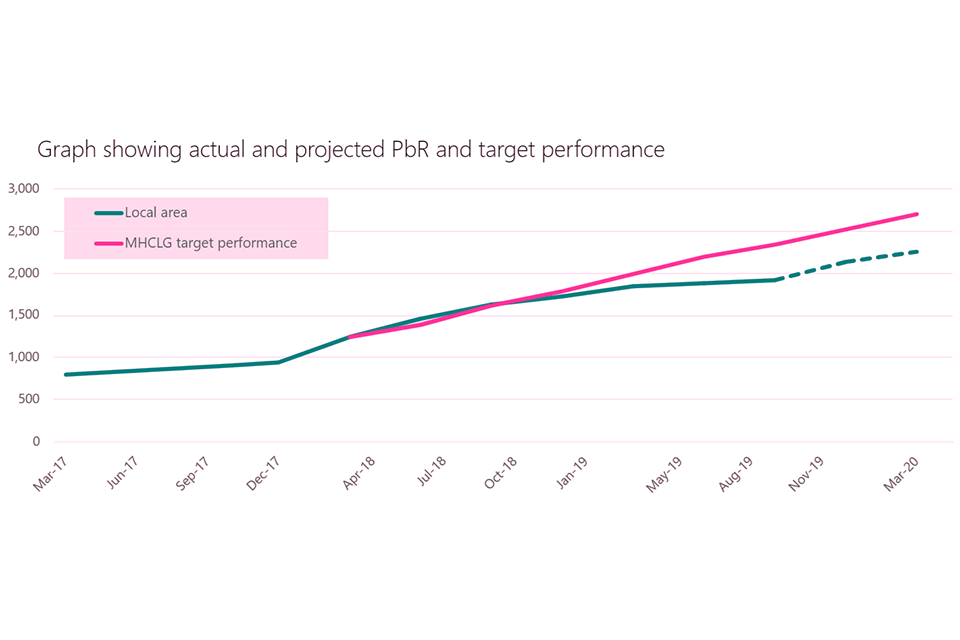

Figure 1: A sample of the type of output from the Local Area Analysis Dashboard. Please note that this data is not from any actual local authority and is for illustrative purposes only.

Successful family outcomes for 2020-2021

In 2020-2021, the programme has continued to support families to improve their lives. Successful family outcomes are the way the programme records positive change at a family level. In most areas successful family outcomes are measured through a Payment by Results claim. Fourteen areas have earned autonomy status and Greater Manchester has a devolution deal with the government. These areas receive all their funding up front and do not make Payment by Results claims. However, they continue to track and report on successful family outcomes, reflecting the importance of this measure. The figures in this report combine the Payment by Results claims and the successful outcomes from earned autonomy areas and Greater Manchester.

Why we track family outcomes

Each family outcome represents a family whose life has changed for the better, which is the central aim of the programme. They represent the result of substantial work from a family, the keyworker, and other services. Each local authority’s Troubled Families Programme Outcomes Plan must include outcomes against the key issues set out in the Troubled Families Programme Financial Framework, which are:

- Parents or children involved in crime or antisocial behaviour.

- School attendance.

- Children who need additional support.

- Risk of worklessness or financial difficulties.

- Domestic abuse.

- Physical and mental health.

There are two types of payment by results claim: the first is significant and sustained progress and the second is continuous employment. For a significant and sustained progress claim, a family must have made sustained improvements with the problems that led to them joining the programme. For a continuous employment claim, a family member must have achieved sustained employment. This incentive towards employment outcomes reflects the transformative effect that sustained employment can have on a family’s life. Full details of outcomes and sustainment periods are available in the programme’s financial framework. The standards are high to ensure each successful family outcome genuinely represents a significant change.

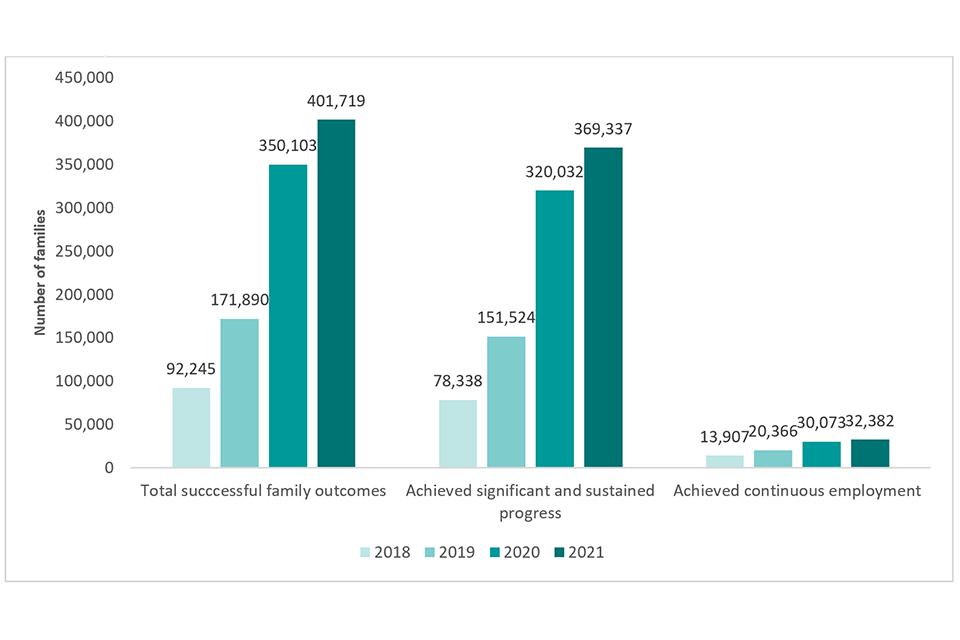

Progress on successful family outcomes up to 2021

The latest figures submitted in January 2021 show that a total of 401,719 families had reported successful family outcomes. This is up from 350,103 in April 2020 and an increase of 51,614 families over nine months. As of 5th January, 77% of the 2020-21 target number of outcomes for was met.

Figure 2: Number of successful family outcomes achieved through the Troubled Families Programme up to January 2021 and compared to cumulative totals published in previous annual reports.

*snapshots of total claims are taken at different time points: March 2018, March 2019, April 2020 and January 2021.

This is not intended to provide a year-on-year comparison. The chart above shows snapshots of total successful family outcomes as published in previous annual reports. There is variation in the time periods between these snapshots. The 2021 figures show change over nine months only. The previous report was published later than usual due to COVID-19 and covered a longer time period. Successful family outcomes figures are subject to change following the auditing process.

Adaptation of local authority funding during COVID-19

This year saw the unprecedented challenge of COVID-19. Local services adapted quickly to support vulnerable families from the COVID-19 crisis and its associated economic and social impacts. At the national level, MHCLG made changes to funding and the measurement of the school attendance and continuous employment outcomes to ensure local areas were able to maintain services.

MHCLG recognised that the pandemic made it more difficult for local authorities to make claims using the Payment by Results system, particularly for school attendance as schools were closed and for employment outcomes while many people were furloughed through the government’s Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme. MHCLG recognised some of the limitations of working virtually and issued some guidance around whole family working in this situation. MHCLG adopted the following temporary changes to the Payment by Results system in response to the crisis:

- Adjusting the way in which local authorities could show progress against the education outcome in response to the school closures in Spring 2020, to prevent local authorities being penalised for children not attending school while they were unable to.

- Ensuring that families on the furlough scheme were recognised as employed and that local authorities could still claim employment outcomes for furloughed workers.

- Moving 25% of the programme’s Payment by Results funding to upfront funding in order to ensure that local areas had sufficient resources to support vulnerable families.

Validation of claims

The programme’s validation process for Payment by Results claims ensures that local programmes are meeting the national programme requirements. It is referred to as the spot check process. In normal circumstances, it involves visits to local authorities to view local data systems and case files, as well as an opportunity to meet service managers and keyworkers. This process checks whether families are eligible for the programme, that local practice adheres to the whole family working principles, and that there is evidence that the outcomes have been achieved. At the start of the financial year the spot check process was paused due to COVID-19. Later in the year, the spot check process restarted in a new virtual format. This will continue while social distancing measures are in place.

This year the programme reached the significant milestone of having spot checked each area twice since the programme began. This gives us confidence in the validity of claims. The majority (92%) of claims have been found to be valid, with invalid claims removed from the claims total. Feedback is provided to local areas on their claims and on their data systems. The national claims validation procedures are in addition to local auditing and assurance of claims.

Case study one: A family’s journey of improvement

To illustrate what a successful family outcome means in practice, the report contains a family level case study from a local authority in the North East.

Family case study: Rachel, 31, is mum to Sam 12, and Jack 7. They moved in with Rachel’s partner John aged 45, three years ago.

What problems did they have?

Sam was in his first year of high school and was anxious about leaving home in the mornings, so had started to scratch his arms with scissors. He would become angry if things didn’t go well at school and was fighting with classmates. At home, Sam sometimes hit his brother and had kicked Rachel. Rachel was nervous of what Sam might do to Jack if they were left alone. Rachel has anxiety and depression, and home life was making this worse. John also has long-term depression and had recently been made redundant.

What help did they receive?

Sam was being seen by Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) who recognised the need for a wider whole family approach. CAMHS approached the local authority and Mary, an intensive family support worker (IFSW) from the council’s Early Help team was introduced to the family.

Mary worked with Sam’s teachers to assign him staff mentors, arranged for Jack to attend counselling at school and John agreed to try talking therapy. Mary helped Rachel choose strategies for supporting the children, like reward charts, structured quality time together and earlier bedtime routines. Arguments were frequent between the parents, so Mary saw Rachel alone at the library for sessions on her relationships. Sam’s therapy continued with CAMHS and Mary encouraged Rachel to talk to the therapist about Sam’s earliest years. He had seen some frightening things done to his mum by his biological dad. The therapist explained that this may have shaped how Sam had attached to Rachel.

As the work progressed, tensions between the adults intensified and one day John told Rachel to leave. Mary and a housing officer helped Rachel apply for benefit entitlements in her own name, bid for a house and move in. Furniture, decoration grants and school uniform vouchers were sourced and Rachel spent the summer organising the new home.

What progress was made?

Rachel and John remain separated. Rachel was successful in applying for a part time job with the help of a specialist employment adviser that Mary had referred her to. John continued with therapy and was supported by Mary into a volunteer job. Rachel attends a weekly women’s support group on healthy relationships and has stuck to the new routines at home. She reports enjoying time with the boys more. Teachers say Sam has made a friend or two and is coping better with stress. Sam has stopped scratching his arms and walks away instead of hitting out. Jack is happier at school and more confident around his brother. At times, arguments still happen, but Rachel feels much surer of her parenting and is no longer worried that Sam will hurt himself or someone else.

Improved services

This section will outline some of the work of central and local government to improve services over the last year.

Helping families earlier

In order to improve family outcomes, the Troubled Families Programme encourages local services to work together and provide earlier help for the whole family. This creates a local partnership of services which is better able to improve a family’s resilience and reduce the risk of problems escalating. From the family’s point of view this means that, regardless of whether they are talking to a teacher, a nurse, a social worker or a police officer, they get support with all their problems. That frontline professional will not always have the skills and specialist training to provide all the necessary help themselves, but they will know where to go to bring in that help from a partner service.

In order to help local partners make sure families’ experience of services is as seamless as possible, the national team published the Early Help System Guide. The guide is based on what is already working around the country and allows local partnerships to benchmark their joint working and local services. They can then plan how they can further improve families’ experience. MHCLG will also be using self-assessments shared by local partnerships to plan their support for local partners in the coming months and years.

Better use of data

Better use of local data is a critical building block for partnerships joining up services for families. The Early Help System Guide covers this in detail, setting out how partners should be using data to help support families, identify problems early and inform their strategic and commissioning decision making.

In addition to the Early Help System Guide, MHCLG has run two annual surveys (2019 and 2020) asking all top tier local authorities to self-report on their local use of data, including data sharing, use of case management and data systems, partnership integration of case management and data usage and how reports are used to inform and develop the support for families.

Sharing data between agencies is the first building block of any mature data system. All but one local authority is receiving inputs of data from at least one service, meaning that every local authority has started the process of sharing data and linking them together, but there is more still to do. The survey showed that:

- The most commonly shared datasets are those that are internal to local authorities, for example, Childrens’ Services and Youth Offending Teams. It is easier to share data from different services in the same organisation than between services in separate organisations.

- More local authorities were accessing missing children’s data in 2020 than in 2019. There was a 26 percentage point increase, the biggest proportion increase of any type of data included in the survey.

- Approximately a third of local authorities access housing and homelessness data. We will be working with local authorities to continue to expand access to this data.

- 41% of local authorities have been able to provide data held by services to family workers to inform their work with families and enable more holistic assessments and action plans.

- Almost three quarters of local authorities now have outcome measures integrated into their case management systems, allowing for quantitative reporting across all cases and therefore understanding of what issues families are facing and outcomes families are achieving.

- Almost half of the local authorities responding said that partner organisations complete assessments on the same case management system as the local authority, promoting shared practices and visibility of cases across services.

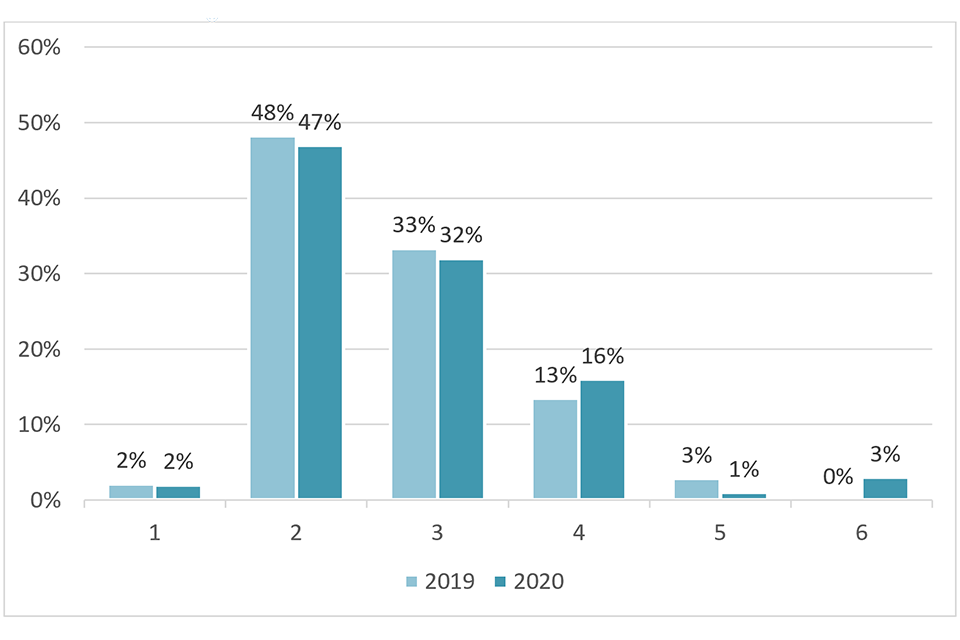

To make sure that data can be used to inform decision making at a strategic level, it is essential to provide analysis and reports explaining what families are experiencing. Almost 9 out of 10 local authorities provide reports on the numbers of families worked with and the outcomes achieved by families. In 2020, 40% of local authorities said that they are able to report on the needs of the population and therefore understand the demand on services. This shows that needs analysis is becoming more widespread, enabling better understanding of support needs in the community. It is important that areas continue to expand the application of needs analysis. This informs decisions about what resources are required to support families. At the end of the survey local authorities are asked to categorise their data maturity into one of six models, increasing in maturity from manual to advanced, as detailed below:

- Manual - Receiving data from other partners which is stored in separate files and which is unmatched to case management systems. The local authority Troubled Families Outcome Plan is not quantified and there is no reporting from the case management system to keyworkers.

- Basic - Some data sources are brought together in basic data software which is used to match and store data, identify families who may need support and to monitor progress. The Troubled Families Outcomes Plan is embedded in the case management system and receives manually inputted reports on outcomes and key indicators.

- Building blocks - Bringing most data sources together including early help case management data. The data is visible to keyworkers in a spreadsheet or form which is only provided once or twice during a case.

- Early maturity - Using a data warehouse or lake where data is accessible to workers automatically in the case management system and which is updated when new feeds are received. More advanced data system software is used with automated matching and calculation of whether Payment by Results outcomes are met is built in. There are likely to be some open feeds[footnote 1].

- Mature - Data warehouse or lake model as in the early maturity model but where primarily open feeds are used and data is used to conduct needs analysis.

- Advanced - Sophisticated data model with open feeds as in the mature model, but where the system has been expanded beyond Troubled Families Programme services and includes whole children’s services or whole of council solutions.

The survey results show that whilst most areas are in basic and building block models, already 20% of local authorities are operating early mature to advanced models. This shows that while some areas are excelling in their use of data, many require further support to continue to develop their data models to a mature level to most effectively support families.

Figure 3: Percentage of local areas on a six-point scale of data maturity – 1 being least mature and 6 being most mature.

MHCLG is using this intelligence to develop a refreshed support offer for local partners including:

- Identifying and sharing good practice through a programme of webinars.

- Tailored one-to-one support for local areas, focusing on unblocking specific issues.

- Focus groups on the barriers to data sharing.

- Working with other government departments to provide joint support.

Having this clear overview of how well data is being used in local areas helps shape the future programme to ensure that families are receiving the most effective support at the right time.

New data sharing guidance

The programme has published new data sharing guidance on gov.uk. This aims to support areas to share data to identify and support families most effectively. The guidance provides support on information governance. This includes the legal gateways organisations can use to share data and the data protection legislation organisations need to comply with when processing that data. It encourages areas to make use of the multiple disadvantage objective in the Digital Economy Act. This is a legal gateway for sharing data to identify individuals or households who face multiple disadvantages to enable the improvement or targeting of public services.

New funding for data projects

MHCLG was awarded £7.9m from HM Treasury’s £200m Shared Outcomes Fund for a new Data Accelerator Fund which aims to improve local areas’ use of data to support vulnerable families. This is one strand of a wider Department for Education led Data Improvement Across Government project which aims to improve data sharing and analysis in both central and local government for vulnerable children and families. The fund is being managed by the national team in MHCLG. However, the fund is broader in scope than the Troubled Families Programme and could be used to fund data improvements targeted on children’s social care, early years, special educational needs and other areas.

Case study two: Family hubs

The following case study describes how in one area services funded by the Troubled Families Programme are delivered from family hubs. Family hubs bring multiple services together under one roof to enable better join up between multiple agencies.

Westminster Family Hubs – improved services case study

Acquiring up-front Earned Autonomy funding through the national Troubled Families Programme helped Westminster to accelerate their Family Hubs model, funding a workforce development programme and introducing a ‘Family Navigator’ role, which acted as a catalyst for true whole family working.

Westminster’s Family Hubs bring together, in one location, all early intervention work delivered by the wide spectrum of early help services. The Hubs are not just buildings, they are a focal point for agencies to come together as an integrated workforce, with a common approach to working with families. This includes council Early Help teams, health visitors, the Children’s Centre School Health, housing, Child and Adolescent Mental Health services (CAMHs), maternity services, police, schools and local voluntary providers, youth clubs and youth services.

One pilot site opened in 2018 has since developed into a network of three Hubs covering the borough. Success has been underpinned by integrated leadership teams, represented by all parts of the Early Help system including local authority services, social work, health and the voluntary sector. These teams have led shared practice models and development plans which are responsive to the needs of families.

Support was introduced early on to address organisational barriers across the existing Early Help system and build professional confidence in the new integrated model. A training programme saw practitioners from schools, the police, health, the voluntary sector and more come together in a shared learning environment. Family Navigators were recruited to act as role models for translating the training into practice, building relationships between local schools and GP practices, helping across the system to support families into the right services and coordinating the professional network around a family. A digital platform was also developed enabling any agency to create family plans, in a common format that can be shared across all services in the Hub system, and with families themselves.

Family Hubs are now an integral part of how Westminster is delivering its Early Help Strategy. Practitioners increasingly report feeling part of a wider system through joined-up training and through working as part of an extended team. Families report getting quicker access to services and not having to repeat their stories. As a result, they are increasingly referring themselves to Early Help through the model.

Local responses to COVID-19

The national programme team has remained in close contact with local areas during the pandemic who have reported some important innovations and adaptations during this time. The first lockdown severely curtailed face-to-face interaction between keyworkers and families. Most local areas used virtual contact with families alongside face-to-face engagement with personal protective equipment when a family had crossed the risk threshold to necessitate a visit. When regulations allowed, local areas looked to innovate to provide safer face-to-face contact for families. Some local areas used “garden visits”, “doorstep visits” or a walk in the park in order to safely meet while maintaining social distancing in an outside space.

Early help services increasingly looked to alternative routes to identify hidden need. Many areas said that they ran local campaigns to promote the support and contact points available. Some set up a helpline for families to call directly. Multiple local authorities reported working more closely with the voluntary sector to identify families who needed help. Families could present at foodbanks saying that they needed help with food and would be asked further questions which might lead to a call with the local authority early help team. Many local areas reported that the lockdown had led to better local service coordination and data sharing as agencies focussed on the crisis. Schools continued to play an important role in identifying need despite school closures. Many remained in remote contact with children and were relaying concerns to early help services. The police also played a prominent role in identifying families who may need help.

Most areas used remote and virtual methods to engage with families during the lockdown. Some areas said that virtual interventions took longer due to the increased time needed to communicate remotely. Others remarked that they could get through caseloads more quickly without the travel time between appointments. Many local areas raised the risk of disguised compliance when using virtual methods. In a virtual call it was easier for families to hide problems, especially related to child safeguarding, compared to a home visit or a face-to-face meeting. Some areas said that virtual methods could work effectively when a family was already known to the keyworker, but that establishing trust and a new relationship through remote methods alone was more difficult. A further problem with virtual methods was that some families did not have devices, internet access or digital skills to engage with early help services. Digital fatigue was reported as having set in for both families and keyworkers from sustained use of these engagement tools.

Remote support included physical deliveries. Some local areas had provided activity packs for families including sports equipment or books. Early help services in some areas sought to include messaging and advice for families with food deliveries. The lockdown presented challenges for keyworkers to engage with domestic abuse victims as it was harder for them to find a safe and private space to discuss their situation openly. Some authorities sought to get around this problem by using written communication. One local authority included a message in a food parcel with a phone number for victims to call, and a further number to dial while on the line if they wished to signal that they were at risk of domestic abuse but could not talk freely.

Many local areas said that they would look to take forward elements of practice developed for social distancing post pandemic, especially virtual methods of communication with families which could be blended with face-to-face methods in the future.

Troubled Families Programme services have, for the most part, remained resilient and adaptive. Local areas have embraced virtual methods of support for families and many intend to take elements of this approach forward post pandemic.

New research findings

Alongside this report, MHCLG is publishing new evaluation reports by the independent researcher Ipsos MORI. This includes the final set of staff surveys as part of the national evaluation and the evaluation report for the Supporting Families Against Youth Crime project (a £5m fund to prevent youth crime). This section summarises new research findings from 2020-2021.

Staff surveys

The staff surveys report the views of staff working on the programme. Questions cover the effectiveness of the programme, how the programme is delivered in that area, workforce development, how the programme could improve and much more. There were three separate staff surveys for Troubled Families Coordinators (TFCs), keyworkers and Troubled Families Employment Advisers (TFEAs). This is the final wave of staff surveys after five years of annual surveys as part of the national evaluation.

The Troubled Families staff survey has been an invaluable resource for tracking progress of the programme over time. Apart from providing an annual update on the programme delivery at national level, it has helped inform and shape the focus of the qualitative case studies to dig deeper on successes and challenges of the implementation and delivery of the programme. MHCLG and Ipsos MORI are grateful to all participants over the years who have given their time generously and contributed to its success.

Many measures have remained consistent over the five years including the high level of support from staff for the programme. Troubled Families Coordinators’ views of the programme remain positive and consistent with previous years: 95% agree the programme is effective at achieving whole family working; 89% agree it’s successful at achieving long term change for families; and 68% agree it’s effective at improving data sharing between agencies. More Troubled Families Coordinators say the programme is effective at achieving cost savings than in the previous year (up from 37% to 47%) and that it is effective at managing children’s social care demand (up from 65% to 74%).

Keyworkers remain confident that the programme is effective in achieving whole family working (84%) and achieving long term change in families’ circumstances (79%). The role of keyworkers remains largely unchanged based on the data from the last year. The majority (82%) visit families at least once a week. Most keyworkers continue to work with families at home (76% most of the time). To help families make positive changes, almost all keyworkers highlight the importance of building trust with families (89%), active listening (85%) and empathy (84%). The average caseload is 13. Keyworkers most commonly help with parenting skills, mental health support and with getting children to school.

The survey of Troubled Families Employment Advisers reported that 97% continue to believe that the programme is successful at achieving long term change and 95% say it is effective at achieving whole family working. 89% believe the programme is effective at achieving wider system change and 86% think it’s successful at achieving change in their Jobcentre Plus area. These are slightly more positive findings than last year.

Evaluation of Supporting Families Against Youth Crime Fund

Alongside this report, MHCLG is publishing an independent evaluation of the Supporting Families Against Youth Crime fund which ran in financial years 2018-2019 and 2019-2020. The fund made £9.5m available to local authorities and partners to tackle gang and youth crime as an enhancement to their local Troubled Families Programme funded services. The project was designed to support the early intervention and prevention themes of the government’s Serious Violence Strategy published in April 2018. There was an emphasis on integrating with the Troubled Families Programme, working with the voluntary and community sector, with schools and with children about to transition from primary to secondary school.

The fund supported interventions in 21 local authority areas: Manchester City, Enfield, Lambeth, Brent, Bradford, Liverpool City, Newham, Nottingham City, Greenwich, Coventry City, Kent County Council, Birmingham City Council, Sefton, Redbridge, Haringey, Sandwell, Islington, Tower Hamlets, Stoke on Trent, Central Bedfordshire and Hammersmith and Fulham.

The evaluation

The independent evaluation looked at the range of interventions supported by the fund. It carried out interviews with local stakeholders, delivery staff, parents / carers and children in a selection of areas and a survey of staff in all areas that received funding. It also reviewed local evaluations carried out by local authorities as part of the fund. It reported back on how the fund was implemented and how it was viewed by practitioners and those who received support. It was a process evaluation and was not designed to provide a measure of impact. Therefore it cannot tell us the overall impact of the interventions. However, it gives indications of promising interventions and practice that could be tested for impact in the future.

The findings will feed into wider work across government to build the evidence base for what is effective in tackling youth crime. This work includes the ongoing Youth Endowment Fund which is a £200m project to review evidence, fund promising practice and rigorously evaluate those interventions.

Findings from national research

The evaluation reported positive responses to a number of interventions. It found that activities outside of school hours run by relatable positive role models helped young people build confidence, make new friends and improved their resilience. Young people with support from the keyworker could open-up to a trusted adult who could help them with mental health concerns or problems at school and in their family. Parents gained access to social support and positive family activities.

In terms of engaging with families, the report found that families were best engaged through schools, particularly in the key transition years between primary and secondary school where children were most likely to be drawn into risk routes. The Troubled Families Programme infrastructure facilitated partnership working with the voluntary sector who helped in reaching families.

The surveys of practitioners provided further evidence of the reported risk factors for youth crime and violence. Practitioners identified key risk factors of youth crime and where this intervention could have a real impact. These were poor school attendance, child criminal exploitation, and negative influence from peer groups. Other risk factors reported were poverty and exposure to violence and crime within the family, but practitioners felt that those factors were more difficult to influence.

Findings from local evaluation

Ipsos MORI reviewed the local evaluations of the 21 local authorities who had participated in the fund. Interventions ranged from whole school or whole year group interventions to one-to-one mentoring, parent focused work and whole family approaches.

Overall, the local evaluations showed some encouraging findings including that:

- Role model based interventions were reported as effective in improving young people’s confidence to say no to negative peer pressure and improved motivation.

- Mentoring for parents and young people, parenting programmes and additional family support had resulted in improvements in behaviour in detention and in expressing feelings, and less bullying and arguing with parents.

- In one area, a whole family working based intervention resulted in reduced risk of exclusion, improved employment potential, improved family communication and reduced drug use. In another area whole family interventions were associated with improvements recorded on questionnaires on parenting and family relationships. The role of the trusted practitioner was key to realising these outcomes.

- Practitioners felt they needed access to better quality information to assess a family’s suitability for intervention.

- Trusted and committed practitioners were seen as key to success and for interventions to seek to strengthen both parent to child and child to child relationships. Ipsos MORI’s assessment of the methods used in local evaluations found that most local authorities used either quantitative or qualitative methods. It was rare for local authorities to use both (mixed methods). Quantitative methods included before and after intervention surveys, analysis of existing data sources and new engagement data. Qualitative methods included focus groups, interviews, case studies and observation of a young person’s behaviour and engagement before and after the intervention.

Case study three: Supporting Families Against Youth Crime

Sandwell Council was supported through the youth crime fund. This case study explains how tools were developed to educate school children about the dangers of getting involved in youth crime and the importance of making positive choices. Note: This is not taken from the Ipsos MORI evaluation. This is a separate case study provided by the local area.

Sandwell Council used funding from the Supporting Families Against Youth Crime project to support innovation in service delivery and build collaborative relationships between place-based, voluntary and community services and the central Early Help team. This partnership is bolstered by close personal working relationships built between Early Help leads, community police and school pastoral team leads.

Community police officers in Sandwell identified that increasing numbers of children moving from primary school to secondary school were already in need of preventative support relating to youth crime and the risk of exploitation. In response, they designed inhouse a ‘choose your own adventure’ style book, taken from real cases which had been investigated locally.

The reader experiences the story through the eyes of the main character who is just starting secondary school. The book then offers the reader two possible choices and the decision made will determine which page to turn to next. At the back of this book there is a local directory of helplines and websites. Police were supported by school pastoral leads to begin trialling it in lessons and Early Help teams and their partner agencies were engaged. One school led by rolling the programme out to year seven and eight students. An educational toolkit was developed with lesson planning and resources, and family practitioners began using it with parents and children at home to highlight risks for children of primary school age.

The toolkit is co-produced, collaborative and is now widely used across the spectrum of the area’s services. Local partners cite the Choices Book and educational toolkit as an essential example of the collaborative working taking place locally across statutory and targeted services, to eradicate serious violent crime by fostering and promoting protective behaviours.

Annex A: Successful outcomes by local authority to January 2021

Please see the separate download of successful outcomes by local authority.

-

Open feeds are data feeds which provide information on the whole of the relevant population rather than a cohort that is already defined. This is important to identify unmet needs. ↩