Identifying New UK Growth Opportunities Within the UK-Singapore DEA and Future Digital Partnerships

Published 24 September 2025

1. Foreword

The digital landscape is evolving at unprecedented speed. For the UK—with our world-leading services sector—digital trade presents extraordinary opportunities to boost exports and strengthen our position as a global innovation hub.

The UK-Singapore Digital Economy Agreement (UKSDEA), signed in February 2022, was the first Digital Economy Agreement (DEA) between Singapore and a European country. This established an ambitious framework for digital cooperation between our two countries. In the year that we celebrate 60 years of UK-Singapore Diplomatic relations, this groundbreaking agreement has strengthened our digital trade links with Singapore. It has also helped British businesses access new opportunities both in Singapore and across Southeast Asia.

This assessment confirms that the UK-Singapore DEA remains best-in-class, setting high standards for digital trade that reflect our shared values of openness, innovation and fair competition. British businesses at the cutting edge of innovation have praised the agreement for fostering a collaborative ecosystem where they can connect with Singaporean partners, access new markets, and develop technology solutions with global applications. However, the pace of technological change means we must continually evaluate and enhance our approach.

This report identifies several promising areas for further development: streamlined paperless trading systems, enhanced cybersecurity cooperation including quantum-resistant technologies, improved regulatory coherence in cross-border data governance, and deeper collaboration on emerging technologies like artificial intelligence and blockchain. We are particularly encouraged by the opportunities to build on existing pilot projects and develop new initiatives that deliver tangible benefits and efficiency gains for businesses in both countries. As the report suggests, the structure of the agreement facilitates adjustments by encouraging both governments to meet and discuss changes in the digital environment

Delivered with businesses at the heart of the implementation, the DEA has the potential to take our trading relationship with Singapore – worth £22.4 billion in 2023 – to the next level.

We would like to offer thanks to those who contributed to this report, particularly Dr. Deborah Elms and Jia Hui Tee at the Hinrich Foundation, the British Chamber of Commerce in Singapore, and all the UK companies who contributed through their participation in the roundtable and interviews.

The UK and Singapore are committed to pioneering new approaches to digital trade together, setting standards that will shape the global digital economy for years to come.

British High Commissioner to Singapore, Nikesh Mehta OBE and His Majesty’s Trade Commissioner for Asia Pacific, Martin Kent

Disclaimer

The analysis provided in this report has been prepared for information purposes and should not be relied upon for any commercial, financial, legal or contractual advice or decisions.

2. Executive Summary

Digital trade represents a rapidly expanding segment of the global economy. For the UK, a services-oriented economy, the opportunities in digital trade are vast, especially for innovative and agile businesses. Digitalisation is reshaping industries such as finance, healthcare, manufacturing, and retail, fostering a global marketplace less constrained by geographical boundaries.

There are different formal mechanisms which the UK and others have used to enhance digital trade cooperation between countries such as: 1) signing a free trade agreements (FTAs) with an e-commerce chapter outlining rules for digital trade, 2) inking digital economy agreements (DEAs) which provide a more holistic approach to digital cooperation, or 3) crafting projects, perhaps under an umbrella of digital partnership, which can be a less formal way to establish cooperation and can be signed among government bodies, private sector companies, or both.

The UK and Singapore initially established an FTA that included chapters on e-commerce and services. To further advance digital trade and seize new digital opportunities, both countries signed a DEA in February 2022 with additional memorandums of understanding (MOUs) attached. Since then, advancements in technology and regulatory frameworks have highlighted the importance of continuously assessing and updating digital trade policies. By staying informed of global trends and adapting policies to align with current needs, the UK can maximise the benefits of digital trade for its businesses and help ensure their success in the digital era.

This report aims to: 1) outline global and regional developments in the digital economy; and 2) review the impact of the agreement on UK businesses by gathering views from private sector stakeholders and provide recommendations for future enhancements. These recommendations are aimed at addressing current gaps and improving the framework to ensure that UK businesses can fully leverage digital trade opportunities provided by the UKSDEA.

It is timely to review the impact of the DEA, particularly as seen by businesses attempting to take advantage of provisions in the agreement. However, it is also important to note that the agreement has only been in force for a short period, making an assessment of concrete deliverables difficult to discern. This challenge is exacerbated by the context: the UK and Singapore have a long history of free trade and integration, follow similar legal frameworks, and have been at the cutting edge of crafting supportive domestic digital environments. This means that any DEA between them will likely have only narrow gaps to plug in policy settings to achieve better alignment. Largely as a result, businesses have struggled to clearly identify opportunities for digital trade that have been opened directly as a result of signing UKSDEA. An expanded network of DEAs in the region, however, could help companies better navigate digital trade as the overall economic conditions in less like-minded markets are often not as automatically favourable to UK businesses.

Business views on the impact of the UKSDEA

The UKSDEA has been praised by UK businesses interviewed in the study for fostering a collaborative digital trade environment. UK business stakeholders highlight its role in enhancing cooperation, trust, and legal transparency, enabling firms to connect with the Singaporean market more effectively. The agreement has facilitated more dialogue through government and business-led initiatives, supporting digital trade expansion.

Despite its advantages, some businesses struggle to identify the UKSDEA’s immediate benefits, questioning its practical impact. Companies emphasise the need for clearer communication on its advantages and better demonstration of real-world applications. Stakeholders suggest that pilot projects, sector-specific mapping of agreement provisions, and stronger financial support for trade missions could enhance awareness and utilisation. Rather than viewing this as a problem, though, it actually reflects the already high levels of legal and regulatory alignment between the UK and Singapore, where the ease of doing business is at the top of the scale. The UKSDEA does lock in existing practices, ensuring that backsliding on digital commitments will not take place in the future. It also provides a convenient focal point for companies and a platform for building on existing government and business engagements in both markets.

Interviewed stakeholders appreciated the agreement’s role in enhancing trade, fostering cooperation, and promoting trust between the UK and Singapore. The MOUs signed under the UKSDEA have already spurred pilot projects namely the UK – Southeast Asia Trade Digitalisation Pilots (TDP), pioneered an initiative to fully digitalise cross-border movement of goods, and the exploration of scalable digital solutions like the use of quantum technology to secure the contents of electronic trade documents and shipment information exchanged. The MOU approach could be particularly useful to support rapidly evolving industries such as fintech, e-commerce, and cybersecurity. Stakeholders indicated interests in seeing strengthened commitments in regulatory coherence and greater transparency in data governance, and mutual recognition of professional qualifications to maximise the agreement’s potential. Overall, the UKSDEA positions both countries to more effectively navigate and capitalise on the complexities of the digital economy. If used as a template for future DEA negotiations, companies could see clear business benefits from enhanced alignment on digital policies.

Recommendations

A careful review of the provisions in the UKSDEA, supplemented by information gathered through stakeholder interviews, suggests seven broad business-focused recommendations for the future:

1. Enhance outreach and implementation:

- Stakeholders praised the engagement of the UK government and the High Commission in Singapore for providing strong support for business engagement. Firms highlighted the importance of trade missions and urged additional, ongoing engagement to drive meaningful collaboration.

- The UK government and associated stakeholders should continue to play a proactive role and focus more on increasing its outreach efforts particularly to publicise the UKSDEA and attract more attention from businesses in the US, Singapore, and the rest of Asia-Pacific.

- The governments could also help UK companies identify relevant industry experts in government trade bodies for guidance.

2. Greater mutual alignment on data policies:

- Governments should continue to focus on data regulations which can restrict businesses from engaging in cross-border data transfers and storage.

- Regulatory alignment of data collection, governance, and cross-border data flows should be encouraged, especially for emerging data-intensive fields like autonomous vehicles.

3. Integrate emerging technologies into DEA text or MOUs:

- AI provisions in DEAs tend to provide limited scope while blockchain and Internet of Things (IoT) technologies are not referenced in DEA text.

- Inclusion of these provisions into DEAs or MOU activities can facilitate the adoption of these technologies by providing a framework for cooperation and knowledge sharing among participating countries.

4. Expand cybersecurity cooperation on post-quantum cryptography

- Post-quantum cryptography, aimed at developing cryptographic systems secure against quantum computers, is crucial as quantum computing threatens current encryption methods.

- Business stakeholders recognised the cybersecurity strengths of the UK and strong cooperation on cybersecurity between the UK and Singapore and emphasised leveraging existing DEA partnerships for cybersecurity advancements, ensuring secure digital transactions, and protecting sensitive data.

5. Interoperable standards:

- The UK and Singapore governments should push for common international data standards or interoperability agreements. This is especially recommended for sectors such as the built environment and autonomous vehicle which faces high costs and inefficiencies created by redundant testing.

- The UK should continue to promote the use of open standards and innovative solutions to ensure cross-border interoperability and transparency.

6. Mutual recognition of professional qualifications:

- Governments could prioritise mutual recognition of professional qualifications to facilitate the smooth movement of skilled professionals across jurisdictions and streamline UK-Singapore talent mobility.

7. Practical pilot projects:

- The UK government could focus on practical pilot projects that offer tangible cost reductions built around concrete and scalable project outcomes. The UK and Singapore should develop projects to test digital trade infrastructure and interoperability.

Conclusions

Our overall assessment is that the UKSDEA remains best in class. Nevertheless, these recommendations from the literature review and business stakeholder discussions support the further development of the agreement.

The UKSDEA is an important framework for engagement between the UK and Singapore. It already contains a number of valuable provisions and a built-in platform for additional dialogue and communication between governments and companies.

Companies are not always aware of the operations underway by governments, but many of the specifics contained in the UKSDEA are important avenues for businesses to engage in digital trade. For example, the use of innovative approaches like MOUs to support bilateral pilot projects gives the UK government a way to anchor useful programming to the DEA structure. Requesting written submissions by firms on DEA elements provides a mechanism for receiving feedback from stakeholders.

Regular reviews of the DEA and the underlying FTA are important in the fast-moving digital world. Having these agreements completed is only part of the challenge—the government needs to continue to promote the DEA, develop materials and outreach that resonates with stakeholder communities, and nimbly execute adjustments or enhancements to the DEA and FTA including the use of pilot projects.

3. Introduction

Digital trade continues to grow, with over 60% of global gross domestic product (GDP) considered linked to digital transactions.[footnote 1] As a services-oriented economy, this burgeoning sector presents significant opportunities for UK businesses, especially those that are innovative and agile. Digitisation is disrupting and transforming entire industries, from finance and healthcare to manufacturing and retail, creating a global marketplace where geographical boundaries are less significant.

The UK was the first nation outside of Asia to sign a DEA when the UKSDEA was signed in February 2022. This agreement was an addition to the existing UK-Singapore Free Trade Agreement and built stronger and deeper rules to align both parties on digital trade. The UKSDEA also included pioneering commitments on Lawtech and Fintech. It laid the groundwork for trade digitalisation pilots between the UK and Singapore, facilitating smoother and more efficient cross-border e-commerce goods transactions.

Before turning to the substance of the DEA and an assessment of its provisions and impact for companies, it can be helpful to start with the broader economic context.

Exports of digitally deliverable services for both the UK and Singapore have been generally rising from 2010 to 2023 (Figure 1). Following a digital boom experienced in the Covid-19 pandemic (2020), the UK as a leading services exporter (second largest in the world), experienced a substantial increase in digital services exports in 2023 (16.2%) from the previous year; the increase for Singapore’s digital services exports is more moderate at 5.8%.

Figure 1: The UK’s and Singapore’s digitally deliverable services exports, billion £ (2010-2023). Source: UNCTAD[footnote 2]

The UK's and Singapore's digitally deliverable services exports, billion £ (2010-2023)

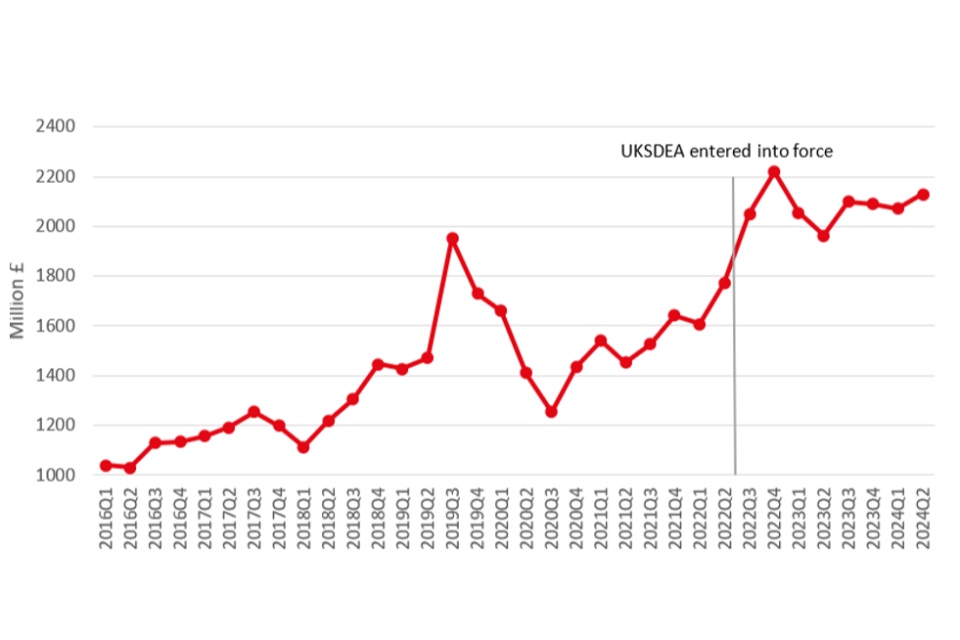

Figure 2: UK services exports to Singapore, million £ (2016Q1 to 2024Q1). Source: UK Office of National Statistics

UK services exports to Singapore, million £ (2016Q1 to 2024Q1)

Since the UKSDEA came into effect on 14 June 2022, the UK’s services exports to Singapore increased in the following two quarters (Figure 2), potentially showing an initial positive impact of the agreement although difficult to pinpoint exact attribution. Changing global economic conditions, industry-specific challenges, and market dynamics, all play a role in influencing services exports.

The digital landscape is continually evolving, and new developments have emerged since the UK-Singapore DEA was signed. For instance, Singapore signed its fourth DEA with the European Union (EU) in 2024, and the Digital Economy Partnership Agreement (DEPA) expanded to include South Korea as its fourth member, joining Singapore, Chile and New Zealand, reflecting the growing importance of digital trade in the Asia-Pacific region. Additionally, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Digital Economy Framework Agreement (DEFA) negotiations commenced in November 2023, aiming to create a comprehensive framework to enhance digital trade and cooperation among ASEAN Member States, with a target to reach conclusion in 2025.

These developments highlight the need for the UK to continually assess and update its digital trade policies. By staying informed about global digital trade trends and adapting its policies accordingly, the UK can maximise the benefits of digital trade agreements for its businesses. This proactive approach will enable the UK to maintain its leadership in digital trade and ensure that its businesses can thrive in an increasingly digital world.

This report provides an in-depth analysis of recent digital trade developments and its implications for UK stakeholders. Specifically, the report consists of five sections:

- Section 3 provides a summary of global and regional developments in the digital economy;

- Section 4 undertakes an assessment of the impact of the UKSDEA on businesses since its signing;

- Section 5 spotlights on the use of MOUs as an innovative mechanism for cooperation; and

- Section 6 sets out recommendations for the UK to strengthen digital trade partnerships with Singapore and the region.

4. Global and regional developments in digital economy

Assessing the fit of a DEA requires an understanding of evolving digital issues. This section identifies important developments in the wider digital economy. At the moment, many agreements simply reference these topics or agree to cooperate in future dialogues. Global developments in the digital economy extend beyond trade policy, encompassing a range of initiatives and innovations that are reshaping industries and societies. Key areas of development include advancements in fintech, artificial intelligence (AI), quantum technology, cybersecurity, and digital infrastructure enhancements (5G and 6G, IoT, data centres, submarine cables).

4.1. Fintech

In the realm of mobile payments, countries like Singapore and China are at the forefront of mobile payment adoption. Singapore has embraced mobile payment solutions extensively, fostering a cashless society through the use of various digital payment platforms. One prominent platform is PayNow, which allows users to send and receive funds instantly using just their mobile numbers or national identification numbers. China’s Alipay and WeChat Pay have transformed everyday transactions with digital wallets and QR code payments.[footnote 3] Beyond QR codes, companies as such Amazon,[footnote 4] Mastercard,[footnote 5] Alibaba, and Tencent are pioneering biometric payment methods, using palm scans and facial recognition to facilitate transactions without need for a mobile device.

Innovations in blockchain technology, which provided enhanced security and transparency for financial transactions, have contributed to greater trust and use of cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin and Ethereum as a payment method. While cryptocurrencies can facilitate cross-border transactions without the need for traditional financial intermediaries, the use of cryptocurrency payment, however, remained small due to its volatility and limited acceptance by merchants.[footnote 6] Coinbase Commerce and BitPay are a few of the leading payment gateway providers enabling seamless crypto transactions.

Growing interests and popularity of cryptocurrencies have contributed to the development of several central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) and pilots that are underway. The Bahamas, Jamaica, and Nigeria have successfully launched their CBDCs; several other countries including China and India are in the advanced stages of developing and piloting their retail CBDCs.[footnote 7] The UK has yet to decide whether to pursue a CBDC while Singapore will be piloting wholesale CBDC.[footnote 8]

Another noteworthy development is the rise of decentralised finance (DeFi), which leverages blockchain technology to create open, transparent, and automated financial services. DeFi platforms have attracted billions of dollars in investments,[footnote 9] offering various services, including lending, borrowing, and trading, without the need for traditional financial intermediaries. Its applications include the establishment of decentralised exchanges (DEXs) which are peer-to-peer trading platforms that allow users to exchange cryptocurrencies directly, without the need for a centralised exchange (e.g., Uniswap and PancakeSwap); lending and borrowing of cryptocurrencies (e.g., Aave and Compound); and permitting users to earn passive income by participating in liquidity pools (e.g, Curve and Yearn).[footnote 10]

Advancements in digital banking such as the emergence of neobanks, or digital-only banks are driving financial inclusion and convenience. These banks are particularly popular among younger consumers and tech-savvy individuals and the market size of neobanks is expected to see exponential growth to $836.11 billion in 2028 at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 47.5%.[footnote 11] Examples of neobanks include Chime, Revolut, Nubank, Wise, and Youtrip.

4.2. Artificial intelligence

Artificial intelligence (AI) is profoundly influencing the digital economy with its broad applications and transformative potential across many sectors. In the UK, 3,713 companies provide AI-related products and services; 58% are micro, 28% are small, 10% are medium, and 4% are large-size companies. In 2023, the total revenue generated by AI companies reached 17.5 billion dollars.[footnote 12]

AI-driven algorithms enhance the efficiency and accuracy of financial services by automating tasks such as credit scoring, fraud detection, and personalised financial advice. It was reported in 2023 that AI applications could potentially save the banking industry up to $447 billion by 2023 through improved operational efficiency and customer engagement.

Beyond fintech, AI is revolutionising various other sectors by enabling more sophisticated data analysis and predictive modelling. For instance, in the healthcare industry, AI algorithms analyse medical data to provide diagnostic support and predict patient outcomes, thereby improving treatment plans and patient care. In the UK, the National Health Service (NHS) adopts AI imaging and diagnostic support tools to increase the speed of diagnosis in stroke and cancer patients; AI technologies are also used to track patient admissions and optimise hospital resource allocation.[footnote 13] In India, AI-powered platforms and applications such as Curebay and Docty are assisting rural healthcare workers to manage telemedicine services and provide diagnostic support and treatment recommendations.[footnote 14]

In e-commerce, AI enhances customer experience through personalised recommendations, dynamic pricing, and efficient inventory management. Companies like Amazon leverage AI for supply chain optimisation, route planning, and customer service through chatbots and virtual assistants.[footnote 15] AI-powered augmented reality further enriches the shopping experience—Amazon’s ‘View in Your Room’ feature lets users visualise furniture and TVs in their homes via smartphones, reducing product return rates.[footnote 16] These advancements are transforming the e-commerce landscape, making it more efficient, personalised, and engaging for consumers.

Moreover, AI is pivotal in advancements in autonomous vehicles, where machine learning algorithms process vast amounts of sensor data to enable safe and efficient navigation. US companies such as Tesla and Waymo are at the forefront of developing self-driving technology. WeRide, a Chinese autonomous vehicle technology company has successfully launched commercial services for Robotaxi and Robobus in several parts of China and owned driverless permits in multiple countries.[footnote 17] Singapore has also made significant progress in autonomous vehicle deployment through a structured approach that integrates regulatory frameworks, policies to guide research and real-world testing, and comprehensive infrastructure planning to support widespread adoption.

Another significant AI application is in natural language processing (NLP), where AI enables machines to understand and respond to human language with remarkable accuracy. This technology is being utilised in virtual assistants like Apple’s Siri, Amazon’s Alexa, and Google’s Assistant, which provide users with seamless voice-activated control over their devices and services. Additionally, generative AI has witnessed tremendous growth and innovation in recent years, transforming various industries with creative and practical applications. AI models like OpenAI’s GPT and Google’s BERT have showcased impressive abilities in generating human-like text.

Generative AI is transforming the creative industry, enabling artists to generate unique visuals and making sophisticated design accessible to all. Tools like DALL-E and DeepArt enhance creativity, while AI-driven music applications compose original pieces and generate lyrics for uses such as game soundtracks and therapy. Singapore’s Infocomm Media Development Authority (IMDA) fosters AI innovation through initiatives like PIXEL Innovation Hub, which supports businesses and startups with facilities like prototyping labs, usability testing spaces, and content creation studios, enabling the development of next-generation digital products.

Finally, regulatory technology (Regtech) is playing a crucial role in helping financial institutions comply with ever-evolving regulations. Regtech solutions utilise AI, big data, and cloud computing to automate compliance processes, reducing the risk of human error and ensuring timely adherence to regulatory requirements. Organisations worldwide are increasingly adopting Regtech solutions to mitigate regulatory risks and lowering compliance costs. The Regtech market holds significant potential and is projected to grow at a CAGR of 23.1% from 2024 to 2030, with Asia Pacific RegTech market experiencing the fastest growth.[footnote 18] Leading Regtech companies include ACTICO GmbH, ComplyAdvantage, and NICE Actimize.

4.3. Quantum technology

Quantum technology is set to revolutionise digital trade, offering unprecedented advancements in computing, cryptography, and communication networks. The UK government has recognised the strategic importance of quantum technology and has made significant investments to foster its development. For instance, the UK National Quantum Technologies Programme has allocated substantial funding to research and development, aiming to secure the nation’s position as a leader in quantum innovations.[footnote 19] Initiatives like the Quantum Communications Hub aim to develop secure communication channels. Similarly, Singapore is strengthening its quantum capabilities. In May 2024, Singapore announced its National Quantum Strategy (NQS) with nearly $300 million investment to advance research, talent development, engineering, and industry collaboration, reinforcing its position in quantum innovation.[footnote 20]

4.4. Cybersecurity

In enhancing cybersecurity, AI has played a crucial role by detecting and responding to threats in real-time. Machine learning algorithms analyse patterns and anomalies in network traffic to identify potential security breaches, thereby safeguarding sensitive data from cyber-attacks. Cloud technology and service providers employ multi-layered security protocols, including encryption, intrusion detection systems, and continuous monitoring to safeguard sensitive data. For instance, cloud providers like AWS, Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud integrate machine learning algorithms to detect and mitigate threats in real-time, thus preventing potential breaches before they can cause harm.

As quantum computers become more powerful, new cryptographic algorithms known as post-quantum cryptography (PQC) are being developed to protect against quantum attacks. Companies such as IBM and Google have been at the forefront of PQC research. IBM’s Quantum Safe initiative focuses on creating and standardising cryptographic algorithms that can withstand quantum computing threats. Their researchers have developed algorithms like ML-KEM and ML-DSA, which were selected for standardisation by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST).[footnote 21]

Concerns on cybersecurity of electronic devices have contributed to the development of standards and labels applied to electronic devices. One example is Singapore, where the Singapore Cyber Security Agency of Singapore (CSA) has launched a Cybersecurity Labelling Scheme (CLS) for consumer smart devices to help consumers make informed decisions towards purchasing more secure devices. Singapore has also signed MOU with Finland and Germany to mutually recognise the cybersecurity labels issued by their national agencies[footnote 22] (Note that the UK-Singapore DEA Article 8.61-L contained a provision that could support establishing mutual recognition of a baseline security standard for consumer IoT devices with Singapore).

4.5. Digital infrastructure

Enhancements in digital infrastructure, such as 5G networks, are creating more scalable digital ecosystems. South Korea leads in 5G coverage, supporting IoT, smart cities, and high-speed innovations. The Electronics and Telecommunications Research Institute (ETRI) in South Korea is advancing terahertz frequency bands (6G), aiming to provide faster data transfer and greater bandwidth.[footnote 23] Their research addresses challenges like signal attenuation and device miniaturisation, enabling future applications like ultra-HD streaming and holographic communication. The UK government has launched a 50-million-dollar fund to support IoT and 5G connectivity nationwide. The local and regional authorities can apply for funding under this initiative, which strives to spur innovation in agriculture, advanced manufacturing, transport, public services, and other sectors.[footnote 24]

Furthermore, initiatives to develop nationwide digital identity like the Digital ID programs in Estonia[footnote 25] (e-Residency program) and India’s Aadhaar system[footnote 26] provide citizens with secure and efficient access to services, streamlining government processes and enhancing social inclusion. Singapore has developed a national digital identity system (SingPass) to provide secure, convenient access to a range of government services online. To support mutual recognition of digital identities across countries, several regions and countries are actively exploring collaborations and partnerships. In the EU, the Electronic Identification, Authentication and Trust Services (eIDAS) Regulation provides a framework for the mutual recognition of electronic identities across EU Member States. Other regional blocs such as ASEAN and the African Union are also evaluating options for mutual recognition of ID credentials across borders.[footnote 27] The UK government has also achieved a significant development in the digital identity space in 2024 having successfully integrated 50 government services into the Gov.UK One Login platform, which streamlines the login processes to Government Gateway and other Gov.UK services.[footnote 28]

The IoT epitomises the interconnectedness of devices and systems, enabling them to communicate and exchange data. This technology has seen exponential growth and is projected to revolutionise various sectors. Prominent examples of IoT uses include the development of smart cities where data collected and exchanged by sensors and cameras are supporting real-time traffic management, energy-efficient buildings, and smart public services. In the healthcare sector, IoT devices have significantly enhanced remote patient monitoring and telemedicine. Devices like wearable health monitors provide real-time health data to healthcare providers, improving patient outcomes and enabling timely interventions.

The Industrial IoT (IIoT) is transforming manufacturing processes through predictive maintenance, supply chain optimisation, and automation. By utilising IoT sensors and analytics, manufacturers can monitor equipment performance in real-time, predict potential failures, and schedule maintenance proactively, thereby increasing efficiency and reducing downtime. Companies like GE have leveraged IoT to enhance industrial operations and employed digital twin to test and predict outcomes to optimise manufacturing processes.[footnote 29]

Data centres are the backbone of digital infrastructure, providing the required storage and processing power for vast amounts of data generated by IoT devices, generative AI, and cloud computing. Hyperscale Data Centres are built by companies like Google, Amazon Web Services (AWS), Meta, and Microsoft Azure to cope with the increasing demand for cloud services.[footnote 30] As data centres are highly energy intensive, governments around the world have placed greater emphasis on greening data centres by introducing regulatory standards to improve energy efficiency and ensure that electricity consumed by data centres is produced from low carbon energy sources. One example is Singapore’s standard for Green Data Centres (SS 564).[footnote 31]

Submarine cables are critical components of global communications infrastructure, carrying nearly 99% of the world’s international data traffic. These underwater cables connect continents and ensure global transfer of data at high speeds. Examples of new submarine cables that were in service in 2024 include 2Africa which is the largest cable project in the world connecting Africa with Europe and the Middle East, Asia Direct Cable (ADC) connecting China, Japan, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam, and Myanmar/Malaysia India Singapore Transit (MIST).[footnote 32]

Examples of UK companies operating in key emerging technology sectors

| Sectors | Examples of UK Companies |

|---|---|

| Fintech | Allica Bank, IRIS Software Group, Lendable, Abound, Revolut, Wise |

| Cybersecurity | Clearswift, PQ Shield, PricewaterhouseCooper (PwC), Adarma |

| AI | Lendable, DarkTrace, Multiverse, Quantexa, Wayve (autonomous driving) |

| Quantum technology | Riverlane, ORCA Computing, Oxford Quantum Circuits |

| Digital Infrastructure | Telehouse, Virtus Data Centres, Sofant Technologies, BT Group |

The advancements in digital technologies and infrastructure are pivotal to the ongoing digital transformation. These developments not only enhance connectivity and data processing capabilities but also pave the way for innovative applications and services. As technology continues to evolve, the continuous upgrading and expansion of digital infrastructure will remain crucial in supporting the burgeoning digital economy and fostering a more connected world. For the UK Government, these global digital developments underscore the importance of actively participating in international digital trade agreements and partnerships.

4.6. Gaps between global digital developments and the UK

There are discernible gaps where the United Kingdom lags behind other advanced digital economies. While the UK’s digital infrastructure has experienced notable improvements, it continues to face considerable challenges. Emerging technologies such as 5G, artificial intelligence, and quantum computing are advancing rapidly in countries such as South Korea, China, and the United States, leaving the UK in a position where it must strive to keep pace.

- While countries such as South Korea and China have been leading the charge in the deployment of 5G technology, the UK has faced delays and slower rollouts. This affects the potential for high-speed, low-latency connectivity, which is vital for emerging technologies like autonomous vehicles and building smart cities. The UK’s digital infrastructure, while advancing, still falls short in terms of universal high-speed internet access. Countries like South Korea and Japan boast almost ubiquitous high-speed internet coverage. In comparison, rural and less densely populated areas in the UK often suffer from inadequate connectivity, creating a digital divide that restricts economic opportunities and growth.[footnote 33]

- Leading nations such as the US and China are investing heavily in AI and quantum computing research and development. While the UK has made strides, the level of investment and the pace of development remain behind these frontrunners, impacting future competitiveness.

Addressing these gaps with targeted investments and digital strategies will be essential for the UK to bolster its digital economy and secure its position as a global technological leader. By aligning with global standards and embracing advanced technologies such as AI, 5G, and quantum computing, the UK can ensure its competitive edge and economic resilience in the digital era. Additionally, investing in cybersecurity measures to mitigate post-quantum challenges and ensuring sustainable digital infrastructure will be key to safeguarding national interests and promoting a secure and sustainable digital future.

4.7. Reviewing digital agreements against global digital economy developments

Existing digital trade agreements still fall short of addressing the wide range of emerging technologies. While these agreements have made strides in facilitating digital trade, enhancing cybersecurity, and promoting data protection, they often lack comprehensive provisions for rapidly evolving areas such as artificial intelligence, blockchain, and the IoT. The pace at which technology is advancing demands more agile and forward-thinking frameworks that can adapt to new innovations and challenges.

Moreover, the harmonisation of digital standards across different jurisdictions remains a complex issue. Countries have diverse regulatory environments and priorities, leading to a patchwork of rules that can hinder the seamless flow of digital goods and services. In sectors such as autonomous vehicles, businesses could face the need for individual testing of vehicles under the same model (Box 1). This fragmentation poses challenges for businesses operating in multiple markets, as they must navigate varying requirements for standards, data privacy, cybersecurity, and digital transactions. To bridge these gaps, there is a growing need for cooperation and dialogue between governments and businesses. Such efforts could include the creation of interoperable standards for emerging technologies, as well as mechanisms for dispute resolution in digital trade matters.

Box 1 – Aurrigo: Navigating data regulation ambiguities through best practices

Aurrigo designs and develops fully automated smart airside solutions for the aviation industry, such as automated vehicles, systems, and software. The UK-based company provides innovative and critical solutions to various vehicle original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) and providers. Their services help enhance movement efficiency, reduce transport time and cost, and eliminate safety risks at the airside.

According to David Keene, the CEO of Aurrigo, a significant part of their work is based on collaboration between the company’s technical team and on-ground team based at the airport in different countries. To handle airport autonomous vehicle operations, which typically involve the collection and storage of massive amounts of data including recordings from cameras (a terabyte of data per vehicle per day), the company maintains an on-premises server that prevents data from being compromised by external threats and observe strict data storage and security measures.

Due to differences in data regulations across jurisdictions such as that of the UK and Singapore, the company upholds best practices observed in the UK where data regulations are comparatively more stringent and applies similar practices to their operations in other jurisdictions. While the company is aware of the UKSDEA, provisions covered in the agreement which promotes cross-border data flow and prohibits the need for data storage fall within the exceptions due to the sensitive nature of its airside operations. The DEA, however, serves to facilitate conversations with potential partners and clients built on the premise of an ‘umbrella for cooperation’, thereby contributing to positive synergies.

The regulation-related inconsistency between the two countries likely stems from the limited understanding of the nature and purpose of data collected by companies operating in the autonomous vehicles industry. This is evident in differing data retention policies, particularly at sensitive sites like airside, and inconsistent regulations on autonomous vehicle communication and operations. For example, every autonomous vehicle built in the UK must undergo individual testing upon arrival in Singapore, even if these are identical to approved models, due to a lack of homologation standards, causing delays and added complexity. As such, mutual agreement and cooperation among the UK and Singapore on harmonisation of regulatory and industrial standards in emerging frontiers, like autonomous vehicles, would foster a more conducive operational and decision-making environment for businesses.

One of Aurrigo’s key agendas for 2025 is to expand its operations across Asia-Pacific beyond Singapore. The company emphasises the importance of a proactive role by the UK government and its emissaries in Singapore and other regional countries to facilitate introductions, initiate formal discussions with relevant stakeholders, and explore potential opportunities in the region such as in Malaysia, Vietnam, Thailand, and Australia. Additionally, grant assistance from the UK government could serve as a crucial enabler for their business expansion efforts.

Source: From an interview with Mr. David Keene, CEO of Aurrigo (12 December 2024)

5. Business stakeholder comments

The DEA has two broad purposes—to help structure government-to-government engagement on digital trade and to support businesses delivering digital trade between the UK and Singapore. To get a better sense of the needs of companies, this project conducted a series of interviews with business leaders (shown in the Appendix) as well as a group session in a roundtable supported by BritCham. Overall, firms involved in the discussions reported on limited challenges doing business between the UK and Singapore. This is, in large part, because both countries share a common legal system, language, and have relatively similar levels of regulatory excellence. (Note that firms in the project did suggest that future DEA discussions with Singapore’s regional neighbours might reveal distinctly different types of challenges which are not present in the Singapore market.)

5.1. Benefits of the UKSDEA

Businesses have praised the DEA for fostering a collaborative environment that enhances digital trade . According to UK stakeholders interviewed in this project, this agreement has paved the way for enhanced trade and cooperation, particularly in industries that are rapidly evolving in the digital era. One stakeholder notes that ‘the DEA helps in facilitating and building trust between the two economies and businesses, knowing that the legal framework and jurisdiction are transparent,’ and another commended that ‘the DEA provides a good way of connecting up our value proposition to the market’.

With an established agreement that was promulgated to the business stakeholders by the UK and Singapore government and relevant support activities initiated by business chambers and associations forged around digital trade, the UKSDEA is an integral link in the digital ecosystem that provides an environment for more conversations to take place. Pivoting on the agreement, the MOUs signed between the UK and Singapore has also spurred pilot projects and the exploration of new digital solutions that can be scaled across the Asia Pacific region such as the UK – Southeast Asia Trade Digitalisation Pilots (TDP) and the use of quantum technology to secure the contents of electronic trade documents and shipment information exchanged. This proactive approach is particularly beneficial for industries that are rapidly evolving, such as fintech, e-commerce, and cybersecurity. According to a business that participated in the TDP under the MOU, tailoring these pilots to meet the unique needs of businesses is essential. Specifically, considerations around cost and the digital capacity of SMEs must be addressed to ensure the implementation of practical and cost-effective solutions.

Moreover, the MOUs signed between the UK and Singapore under the UKSDEA facilitate collaboration on specific digital issues, such as cybersecurity, digital trade facilitation, and digital identities. These MOUs provide a flexible mechanism for addressing emerging challenges and adapting to new developments, ensuring that the agreement remains relevant and effective in a dynamic digital landscape. Several businesses consulted have associated the successful exchange of electronic bill of lading between the UK and Singapore and the fintech bridge with the UKSDEA and MOU activities.

One business stakeholder pointed out that for larger firms, the impact of the UKSDEA could be more apparent in enabling cost savings facilitated by commitments toward cross border data flows and non-localisation which allows firms to make optimal decisions in resourcing. For instance, by not requiring data to be stored locally, companies can leverage global data centres, thereby reducing operational costs and improving data management efficiency. These cost savings translate to price competitiveness of UK firms, allowing them to offer more attractive pricing to their customers and maintain a competitive edge in the market.

5.2. Issues with demonstrating concrete benefits

Some business feedback indicates a strong disconnect in understanding the tangible benefits of the UKSDEA, with companies questioning, ‘How can the DEA assist us in ways that are perhaps not yet known?’ and expressing a lack of ‘real-world results.’ They further emphasised the importance of further communication of the benefits of the UKSDEA to enhance business awareness and utilisation.

A few stakeholders suggested that one effective method is through pilot projects that demonstrate the use cases and benefits. One commented that ‘Mapping out which parts of the DEA apply to different business sizes and sectors would make it more relevant and usable’. A stakeholder who has participated in the UK’s trade mission to Singapore and the region suggest that there needs to be more ‘follow-ups’ to realise the benefits of such engagements and that more financial support will need to be provided to encourage participation.

Although some stakeholders reported not having utilised or realised the benefits of the UKSDEA due to the existing strong regulatory alignment between the UK and Singapore (in its legal system, language, and historical links), they still appreciate the agreement’s presence. This continued support helps promote trust within the business and technology community by underscoring the strong digital partnership between the UK and Singapore.

5.3. Need to ensure commitments evolve to business needs

Businesses expressed the importance of ensuring that the digital trade commitments in the UKSDEA evolve to meet emerging challenges and opportunities. They welcomed an upgrade of the agreement to include strengthened commitments to achieve greater regulatory coherence and transparency in data and digital governance, more emphasis on emerging technologies to prevent fragmentation and regulatory uncertainty that could arise from new technological and regulatory developments, mutual recognition of professional qualifications, and improved coordination on standards setting and their recognition.

Comments from businesses include:

-

‘Direct mutual recognition would allow professionals to work seamlessly between the UK and Singapore, bringing skills, technology, and business opportunities’. — Head of Markets, Professional Organisation

-

‘Digital trade agreements that create clear, consistent data standards and cloud rules can significantly boost digital trade. It’s about clarity and reducing costs from uncertainty’. — Head of Digital Services, Professional Services Firm

-

‘One of the things that potentially could help is looking at how to reduce trade (export) barriers because quantum technologies are all cast under the same badge as being a little bit sensitive’. — Global Head of Business Development, Technology Company

-

‘There are things being suggested in AI governance that are massively unhelpful. Sensible reasons exist for these suggestions, but the value or harm lies in their execution’. — CEO, Technology Company

Overall, while the immediate benefits of the UKSDEA may not be universally felt, its strategic importance lies in reinforcing the digital alliance between the UK and Singapore, enabling cost efficiencies, fostering innovation, and providing a robust framework for ongoing digital cooperation. As digital trade continues to grow, the UKSDEA can position both countries to capitalise on new opportunities and navigate the complexities of the digital economy more effectively.

Box 2 – LIVR: Reforming AI investment and initiatives

LIVR develops foundational technology for Virtual Reality (VR) and Augmented Reality (AR) through AI solutions, catering to clients across diverse sectors such as education, real estate, and hospitality. Based in the UK, the company aims to establish a corporate office in Singapore and a technology hub in Malaysia.

According to Leo Kellgren-Parker, the CEO of LIVR, most of the company’s clients are in Asia-Pacific, with comparatively higher market penetration rates in Malaysia and Singapore. LIVR became aware of the UK-Singapore Digital Economy Agreement (DEA) through direct engagement with the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO). While the UKSDEA has had limited impact on LIVR due to the company’s existing collaboration with the Singapore government, there remains an opportunity for the UK government to enhance its outreach efforts to better inform domestic companies.

LIVR manages cross-border data flow and storage across different jurisdictions, viewing compliance with differing data regulations as an inherent aspect of conducting business rather than a significant challenge. The company’s digital and virtual asset business model does not involve the collection of personal or identifiable data, thereby reducing its reliance on data-related provisions in the UKSDEA.

Smaller UK companies like LIVR with relatively limited capital could find challenges competing in the AI-driven technology landscape dominated by a few global giants with control over foundational AI models and extensive resources. As such, increased and more strategically targeted funding, facilitated through a more streamlined process by the UK government, would significantly benefit local companies, enabling them to excel and compete more effectively in the AI sector.

Additionally, AI governance regulations will need to be better managed to reduce compliance burden on businesses. Reforming government-led initiatives like the Knowledge Transfer Partnership (KTP) to prioritise business interests and accelerate commercialisation is another area that could enable business innovation and growth.

Source: From an interview with Mr. Leo Kellgren-Parker, CEO of LIVR (11 December 2024)

6. Innovative approaches to digital trade: The use of MOUs

It can be difficult to adapt existing, negotiated agreements quickly to address changing economic conditions or better align with government priorities. But the DEA has an important innovation, the use of MOUs which can bridge the gap between legally binding negotiated commitments and desired outcomes. This section examines MOUs in greater detail as on key mechanism for flexible adaptation.

The digital economy is moving rapidly, with new commercial innovations taking place all the time. The speed of development has made it increasingly difficult for government officials to manage, particularly to be able to build any type of regulatory alignment to support consistency across markets. Regulatory alignment and coherence are important in the digital space, which rarely match geographic borders.

Existing trade rules may be interpreted or stretched to accommodate the specifics of digital trade, such as by extending any existing services pledges to the digital sphere, but the connection can be tenuous or forced. For example, a government promise made in the early 1990s to open up Mode 1 for professional services may have meant to apply only to the transmission of plans via mail or facsimile. It may never have been made in the context of professional services delivery via Zoom calls or via shared digital files in the cloud.

While some governments are building in new commitments in FTAs, extending market access for digital trade has been limited. Many new types of digital topics do not neatly fit into existing methods of handling trade commitments. Governments are often uncertain about the type of promises that ought to be made for rapidly adjusting issues.

Topics which are not seen as sufficiently ‘ripe’ for inclusion in a trade agreement are still important. Hence, leaving them completely off the agenda seems insufficient. Some governments, like Singapore’s Monetary Authority, have pushed policymaking into ‘sandboxes’ as a mechanism for trying out new technology approaches under carefully controlled conditions.[footnote 34] A sandbox approach does not work for every situation. In some instances, issues could present future legal or regulatory risks. For example, the use of AI has been clearly identified as a promising set of technologies that also contains potential sources of risk or harm.[footnote 35] Yet, determining the ‘right’ level of regulation remains unclear.

Parties signing advanced digital trade agreements or including such provisions into ongoing trade arrangements have recognised that agreements can serve as a useful vehicle for coordination. Governments have started using a new type of commitment to manage digital issues that are not sufficiently ready for inclusion in the main body of an agreement.

Singapore and Australia were working on the first digital-only extension to their FTA in 2019. By the end of negotiations, both sides had identified seven areas that were not ready for inclusion in the DEA text: artificial intelligence; electronic invoicing; digital identity; personal data protection; data innovation; electronic certification; and trade facilitation. An eighth topic, on unsolicited commercial messaging, was added in 2022.[footnote 36]

These two trade partners were already connected through a bilateral FTA; a regional ASEAN/Australia/New Zealand FTA (AANZFTA); the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP); and Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). Both were co-conveners of the ongoing Joint Statement Initiative on Electronic Commerce at the World Trade Organisation (WTO). In short, they had extensive experience negotiating and signing trade and digital commitments with one another as well as similar levels of domestic regulation for digital issues.

Yet the two sides still recognised that these eight issues were not yet ready for legally binding commitments in the DEA. They developed an innovative approach to handling important but ‘unripe’ topics: they were covered as part of attached MOUs signed by both sides and attached to the Singapore-Australia DEA (and, by extension, the FTA).

The format and content of the included MOUs varied. The MOU on unsolicited commercial messaging, for example, promised cooperation between the two sides to help investigate, enforce, and research unsolicited commercial electronic messaging, unsolicited telemarketing, and scam telephone calls and SMS. It provided clarity on the process of notification and rendering assistance between signatory agencies. The MOU on electronic invoicing was largely about sharing information about domestic approaches to e-invoicing through coordinated activities like bilateral visits or workshops. The newest MOU, on electronic certification, committed both sides to a pilot program to provide an e-Cert for agricultural products traded between the parties. Thus far, the initiative has contributed to parallel e-Cert to be exchange for edible meat export between Australia and Singapore but has not extended to paperless e-Cert exchange.[footnote 37]

Singapore has found the MOU approach valuable. It was also incorporated into the DEA that Singapore signed with the UK.[footnote 38] UKSDEA included three MOUs including on cybersecurity cooperation; digital trade facilitation; and digital identities cooperation. Both parties also signed two side letters to support negotiations of a UK-Singapore Fintech Bridge and to explore interoperability of single window customs systems.

Singapore’s third DEA, with South Korea, entered into force in January 2023.[footnote 39] It contained three MOUs: to support the exchange of electronic data to facilitate the DEA; to cooperate on AI; and to implement a Korea-Singapore Digital Economy Dialogue.

6.1. MOU activities under the UKSDEA

The UK and Singapore have utilised the MOUs approach to address 12 ‘unripe’ emerging topics within its Digital Economy Agreement. This strategy has facilitated cooperation on critical yet complex digital issues. This includes promising collaboration in areas like cybersecurity, digital trade facilitation, and emerging technologies cooperation. The following table illustrates some MOU activities under the UKSDEA.

Examples of MOU activities under the UKSDEA

| No. | MOU issue area | Event/ initiative/ collaboration | Participating agencies/ organisations | Outcome/impact to businesses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cybersecurity (Scope: Promoting cyber stability, cyber security skills, IoT security, capacity building) | The UK-Singapore Cyber Dialogue (June 13, 2023) | Cyber Security Agency (CSA) in Singapore, FCDO, National Cyber Security Centre, Department for Science, Innovation and Technology, Department for Business and Trade | Senior officials from both countries discussed deterrence strategies to counter cyber threats and the role of public-private partnerships in cybersecurity. The dialogue also facilitated alignment on approaches towards Internet of Things (IoT) security, app security and cyber skills development, including further work on mutual recognition of IoT schemes and mapping of skills and competencies of cybersecurity professionals in Singapore and the UK |

| 2 | Digital Trade, Emerging Technologies (Scope: Promoting business partnerships on AI, sharing experiences of building new telecommunication network) | SGTech organised visit to London Tech Week (June 13-17 2022) | A delegation of eight Singaporean companies, techUK, Tech Nation, InnovateUK, and British Standards Institution (BSI) Group | The event focused on AI, Sustainability, Web 3.0, and HealthTech. The visit introduced Singapore-based enterprise technology companies to the UK market and relevant organisations, with the goal of exploring potential value propositions within the Europe/London ecosystem. |

| 3 | Digital Trade (Scope: Electronic trade documentation, electronic invoicing) | UK - Southeast Asia Trade Digitalisation Pilots (October 2023) | Governments of UK, Singapore, and Thailand; businesses (SAESL, Big C, and Johnson Partners) | Facilitated by the UKSDEA and MoUs, the UK government undertook a series of digital supply chain pilots between Singapore, Thailand, and the UK to showcase the commercial benefits of digitalising supply chain processes. The pilots exemplified that digitalisation processes can significantly reduce cargo shipment time, the use of paper trade documents and related email traffic. It also led to an increase in staff productivity. |

| 4 | Digital Trade (Scope: Electronic trade documentation, electronic invoicing) | Tripartite Agreement by three BritCham member companies | UK firms (LogChain, Hurricane Commerce, and TMX Global) | Under the umbrella of the UKSDEA and its MoU, the three UK companies agreed to jointly collaborate to improve cross-border trade, digitalise supply chain and logistics industries, and assist SMEs. |

| 5 | Emerging Technologies | UK-Singapore Collaborative R&D Call (launched in 2023, annual event) | EnterpriseSG, Innovate UK, and UK and Singaporean businesses | The initiative encourages R&D collaboration among Singaporean and UK businesses into net-zero and digital challenges, commercialisation, and business expansion by covering 70% of the project costs. Areas covered by the funding include cybersecurity, AgriFood Tech, and Mobility and Transport. |

| 6 | Digital Trade, Emerging Technologies (Scope: Electronic invoicing, electronic trade documents, sharing new telecommunication infrastructure to advance future digital connectivity) | Singapore-United Kingdom Quantum Secure eBL pilot project (2023) | Chamber of Commerce UK, Centre for Digital Trade and Innovation (UK), Infocomm Media Development Authority (Singapore), businesses[footnote 40] | The aim of the pilot project was to provide a verifiable, secure, and legally recognised solution for future digital trade transactions. A quantum-secure cross-border electronic trade document transaction was completed for shipping sample building products from the UK to Singapore. |

| 7 | Digital Trade (Scope: Electronic trade documents, electronic invoicing) | UK-Singapore consortium’s first fully digitalised shipment | Singapore Airlines, NG Transport, Woodland Group, BT Rune, and EES Freight Services, Logchain, Fort Vale | The UK and Singapore successfully implemented the first fully digitalised shipment of goods using open and interoperable standards and distributed ledger technology. The digitisation of trade encourages cost savings and a reduced risk of delays for businesses. It also promotes better standards for security, transparency, and efficiency of trade for businesses. |

| 8 | Cybersecurity (Scope: Secure by default, operational delivery, sharing of best practices) | International action to support ransomware victims | Led by the UK and Singapore and included 37 other participants | The countries which are members of the Counter Ransomware Initiative (CRI), along with the cyber insurance bodies supported a new guideline on ransomware that urges companies to not use its funds to fulfil ransom demands but instead, contact law enforcement agencies and relevant cyber experts to retrieve lost data, stop potential additional leak, and identify vulnerabilities. The new guidelines aim to disincentivise the cyber attacker’s business model of financial exploitation and boost collective resilience of companies across the globe. |

| 9 | Cybersecurity (Scope: Cyber security skills, capacity building) | Cyberboost: Catalyse Programme (July 2024) | Singapore’s Cyber Security Agency (CSA), National University of Singapore (NUS), and UK-based innovation company Plexal | The organisations partnered to help early-stage cybersecurity startups in testing, validating, and building minimum viable products and assist companies during their growth stage by providing knowledge and connections to expedite their growth trajectory domestically and internationally. These emerging companies will receive assistance to gain investment, develop overseas networks and go-to-market strategies for new geographical locations for six months. |

| 10 | Data Cooperation (Scope: Sharing research and experimentation on how using data can deliver better public services and economic growth) | UK-Singapore Health Data Partnership (October 2024) | Health Data Research UK (HDR UK), National Research Foundation Singapore (NRF), and SAIL Databank (based in UK’s Swansea University) | The partnership between HDR UK and NRF seek to create innovative ways to improve patient outcomes by using secure and trustworthy health data. Enabled by SAIL databank’s Secure eResearch Platform (SeRP), both sides seek to share best practices in information governance and promote ethical use of data to transform global healthcare systems including the use of trusted research environments (TREs) and cross-border data analytics. |

| 11 | FinTech Bridge (Scope: Explore new business opportunities in each jurisdiction) | Connections Event at SG FinTech Festival (November 2024) | Singapore’s Center for Finance, Technology, and Entrepreneurship (CFTE), UK High Commission in Singapore and HSBC financial services | The exclusive Cocktails and Connections event organised by the UK High Commission in Singapore and HSBC provided an opportunity for companies to network and connect with finance and technology innovators from more than 20 nations and potentially forge valuable international partnerships. |

| 12 | FinTech Bridge (Scope: Explore new business opportunities in each jurisdiction) | UK Fintech Week (April 2024) (April 2024) | The UK’s Innovate Finance, Singapore FinTech Association (SFA), and Singaporean companies | The conference facilitated discussions on how the UK-Singapore FinTech Bridge could enhance financial cooperation and benefits for both countries. Through visits on the ground, the business delegation learnt about the operational aspects of establishing and conducting a business in the UK and provided feedback on how the FinTech platform would enable access to UK market and provide them assistance to deepen collaboration with the UK. |

The MOUs under the UKSDEA provide a helpful platform for coordination on digital issues with flexibilities that go beyond existing commitments. While implementation of the MOUs has been slow, there appears to be significant scope for using MOU commitments to achieve a wide range of objectives, as well as to craft and sign new MOUs, if needed. For example, the Memorandum of Cooperation (MoC) on AI technologies between the UK and Singapore was signed on November 6, 2024, to advance development in safety and reliability of AI technologies.

Different mechanisms of digital cooperation (FTAs, DEAs, digital partnerships)

FTAs frequently incorporate provisions within an e-commerce chapter that delineate the rules and guidelines for digital trade among the signatory nations. These chapters typically encompass aspects such as data protection, electronic signatures, and online consumer protection. Nevertheless, the scope of digital provisions may be somewhat restricted, primarily concentrating on facilitating e-commerce trade and addressing trade barriers. It should however be noted that FTAs could include robust institutional frameworks and dispute settlement mechanisms which can be leveraged to also address digital disputes. Additionally, certain exceptions to the e-commerce chapter and specific types of sectors should also be considered. With extensive trade issues often included in a ‘comprehensive’ trade agreement, FTAs tend to require extensive negotiations and consultations with various stakeholders across different ministries and agencies and may require significant time to conclude the agreement.

Conversely, DEAs adopt a more comprehensive approach to digital cooperation and commitments. They not only encompass the elements found in e-commerce chapters of FTAs but also address a wider range of digital issues such as digital identity, cybersecurity, and cooperation in digital innovation. DEAs are specifically designed to foster a more integrated digital economy among the participating parties, thereby promoting innovation and collaboration across various digital sectors. With niche topics involved, the negotiations of DEAs may be accelerated and thus, DEAs often require less time to be concluded relative to FTAs. For instance, negotiations of the UKSDEA started in June 2021 and reached substantial conclusions within a year in December 2021. Entry into force took place on 14 June 2022.

Digital partnerships tend to be more flexible and can assume various forms depending on the objectives of the cooperating entities. These partnerships may involve government bodies, private sector companies, or a combination of both, and they frequently focus on specific areas of mutual interest. Digital partnerships can be established more swiftly through Memoranda of Understanding (MOUs) or similar agreements. These MOUs outline the scope and objectives of the partnership but may not carry the same legal weight as formal treaties. For instance, digital partnerships might target advancements in fintech, lawtech, or regtech, and could include activities such as joint research, development projects, or policy alignment initiatives. Hence, the time required to conclude a digital partnership can be significantly shorter than that for FTAs or DEAs which allows for more agile and timely collaboration to meet the needs of businesses.

7. Recommendations

The UKSDEA is an important agreement that commits the UK and Singapore to focus attention on the critical arena of digital trade. It sits alongside a bilateral free trade agreement, which means that DEA commitments clarify and expand provisions in the larger FTA. The DEA does not need to outline all the myriad ways, for example, that the UK and Singapore might support services trade as the FTA already contains a substantial chapter for the sector along with provisions in areas like intellectual property rights. Instead, the DEA helps set baseline conditions for certain aspects of digital trade that were not included in the FTA and provides a framework for future legislative and regulatory activities in the digital sphere.

Clearly identifying gaps in coverage in the UKSDEA is difficult. This is partly because the agreement is quite new. It was a best-in-class agreement when concluded and it largely remains so today. In addition, the business environment between the UK and Singapore is broadly comparable, with a long history of engagement, similar legal systems and often identical domestic legislation, and compatible approaches to regulation.

Businesses tend to be unfamiliar with the DEA provisions and do not always recognise the importance of a specific commitment to their business operations. This is especially true if asked directly about the application of a DEA passage to their business model. However, companies are able to provide useful details about what sorts of digital trade operations they are currently conducting and which future activities they would like to undertake. These comments from businesses, as well as more specific suggestions for overall digital business improvement, have been noted in this report and are reproduced here as a set of recommendations.

Companies repeatedly noted how the DEA has been a useful mechanism for reinforcing business confidence and certainty about the overall direction of digital trade between the two countries. While there are some recommendations about ways to improve the operation of the agreement in the future and some specific ideas that might be well suited to pilot projects or specific activities, what businesses really identified was the importance of viewing the UKSDEA as a template for future replication in other markets. While digital trade with Singapore is relatively easy and straightforward, the same cannot be said for other markets in the region. Companies asked for the UK government to consider repeating the DEA negotiations with other, more challenging markets in the region in the future. This is particularly important as interviewed firms saw greater value in Singapore as a gateway market to the wider region, making it more critical that others in the region share similar alignment on FTA issues as well as DEA commitments.

This section highlights two types of recommendations from the project work. First, broader suggestions that apply across all stakeholders, particularly around the institutionalisation of the DEA and continued implementation of commitments. Second, the section pulls out specific recommendations made by stakeholders during the course of interviews and a roundtable. These ideas are often much narrower or more specific. Some may be implemented through the DEA, particularly through a creative use of the MOUs, while others could be seen as outside the scope of the agreement.

7.1. Utilise Agreement Commitments

The UKSDEA has, like the underlying FTA, a series of commitments for regular meetings. This includes consistent opportunities for engagement by officials in various agreement chapters or subcommittees, as well as an annual stocktake exercise. These regular meetings provide a platform for ongoing discussion and dialogue about the issues already tabled for review as well as a place to discuss any upcoming concerns or topics that might need to be visited or revisited in future senior level dialogues.

Some agreements have included businesses and other stakeholders as part of the ongoing consultations. Although UKSDEA does not explicitly require stakeholder engagement as part of regular committee activities, it is at least possible to decide to allow it in the future. Such engagement could take place formally, giving stakeholders a regular seat at the table, or in parallel with ongoing meeting activities. Even without a face-to-face process, it is also possible to include stakeholder inputs in written form in conjunction with regular meetings and, at a minimum, to allow stakeholder submissions ahead of the annual agreement review sessions.

Allowing written submissions to be considered by officials helps ensure that the widest possible array of inputs are part of the dialogue. Particularly for fast evolving sectors like digital, businesses and other stakeholders may have pertinent information that should be considered to ensure that the agreement stays relevant. Digital trade is likely to include stakeholders to the agreement that participating governments will not know, providing an opportunity to expand networks. Businesses were enthusiastic about participating in ongoing DEA activities and repeatedly noted the importance of getting feedback in the rapidly shifting digital landscape.

7.2. Thinking Holistically About Commitments

Governments can become obsessed with following up on their own commitments viewed from a narrow perspective. For example, officials worried about digital competitiveness may be pulling out relevant sections from UKSDEA, such as data flows or AI commitments, to investigate the issues.

However, the DEA is attached to a much larger FTA. To have improved digital economy competitiveness, for instance, it may be more useful to think harder about leveraging the commitments across both the FTA and DEA. How can services firms, for instance, be better encouraged and supported in their cross-border journey? How can commitments on investment which are included in the FTA be considered as a mean to support greater digital trade and transactions? How can companies be encouraged to use broader intellectual property rules in the FTA to support e-commerce trade with trust and confidence? Many of the comments made by companies during interviews were actually better tackled through the FTA than explicitly by the DEA.

The UKSDEA can also be a platform for engagement with other countries in the region or beyond. The UK can support the use of the DEA as a mechanism for future alignment around digital trade. This point was repeatedly made by companies—trade with Singapore is relatively easy. Trade with others in the region is considerably less so, particularly for cutting-edge digital activities.

7.3. Use MOUs

One important recommendation is to use the flexibilities built into the MOUs signed as part of the UKSDEA. These commitments provide a useful platform for dialogue, discussion, and project planning that appears to be insufficiently utilised to date. For example, various pilot projects or funding opportunities could be tied to MOUs or become part of future MOUs as a mechanism for driving bilateral engagement across government ministries and agencies.

MOUs are not, on their own, something that businesses recognise as a valuable tool. But they provide a framework that might be utilised for pilot projects or specific digital trade ideas that require government-to-government dialogue and interaction.

7.4. Agreements in a Drawer Are Unhelpful

Signing an agreement is an excellent first step. But it remains only a first step. Implementation requires governments to work hard at ensuring that companies understand the benefits in any trade commitments and are in a position to take advantage of new opportunities. This includes making sure that any outreach done about new agreements is written in common sense language that resonates with business. It involves working collaboratively with existing business groups to ensure that information is passed to the firms that need it most.

Simply putting information on a government website is never sufficient. Firms, particularly small ones, may not visit government websites for information. Governments have to think much more creatively about how to use other platforms, like social media, to spread information in the appropriate format for the platform. While the businesses in this study largely knew there was a DEA and had an understanding that it could support their digital business activities, they remained largely uncertain about what it might deliver.

The sample of companies that were interviewed is unlikely to be representative, as they were already actively involved in digital trade in Singapore or had made formal plans to do so. This is unlikely to be true for a wider set of companies from the UK. For these firms, knowledge of the DEA is likely to be even lower. It seems clear that greater outreach to the business community in the UK about the FTA and DEA benefits is critically important.

Companies did suggest that materials on the DEA, whether written or video or put on social media, needs to be as sector-specific as possible. This is especially important for smaller firms that are very time and resource constrained. They will only pay attention if the content appears directly relevant.

7.5. Continue to Collaborate with Business