Future Issues for public service leaders

Published 25 July 2022

1. Executive Summary

For this report Ipsos Trends & Futures have used an evidence review and PESTLE (political, economic, social, technological, legal/regulatory and environmental) analysis, stakeholder workshops and leader interviews to explore recent, current and future issues facing public service leaders. It forms part of a wider set of research and evaluation activities conducted by the Government Skills and Curriculum Unit (GSCU) into the public sector response to COVID-19: this paper focuses on current and potential future challenges for senior leaders and the role collaboration can play in solving them. Other papers and activities identify and celebrate the positive developments and innovations arising from the past year and a half.

1.1 Potential future pressures for public service leaders

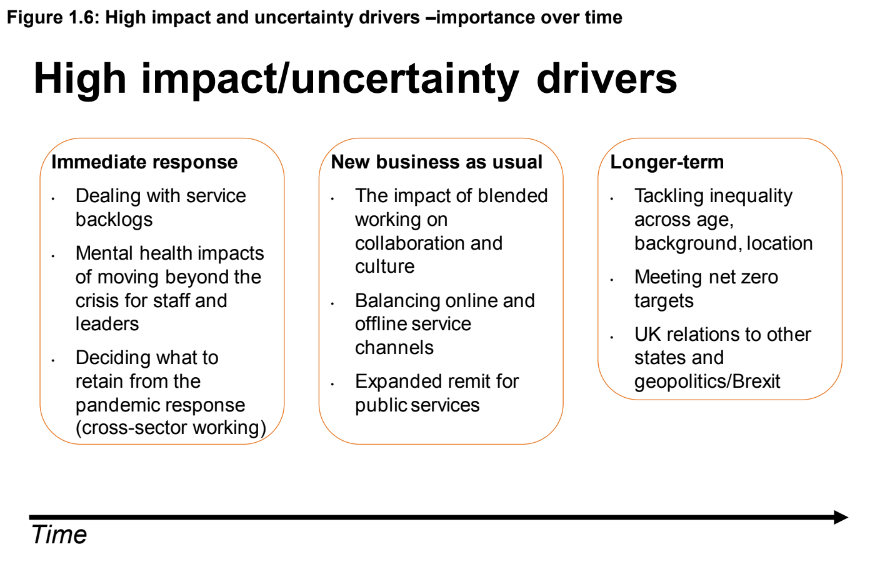

The review and analysis in this report has identified four thematic areas which may pose issues for leaders over the coming years. Each area contains a set of key challenges for public services leaders, which are summarised below:

Theme one: Moving public services online

Making greater use of data and online services are two areas of long-standing interest where COVID-19 has driven significant progress. Some areas of the private sector have made even greater progress still, which may drive expectations of public services in future. Research has suggested that key challenges in this theme include:

-

new public expectations of interactions with public services

-

public trust in automation and AI in public services

-

balancing online and offline across the public sector

Theme two: The changing role of the state

Even before the pandemic, there was research evidence pointing to wider currents in public opinion and government policy pushing towards support for higher levels of government spending and intervention. Research into the experience of COVID-19, combined with the implementation of the EU Exit agreement suggests growth for all parts of the public sector in the next few years. Key challenges here include:

-

unexpected impacts of EU Exit

-

emphasis on long-term planning and preparedness (on climate particularly)

-

tensions in decentralised decision-making between regional actors and the UK Government

Theme three: Rising complexity

Rising complexity in the provision of public services has been a key trend for some time but pre-existing issues around an ageing population, service integration, finance and funding have now been complicated by the long tail of COVID-19 and the large backlog in many services it has generated. Research has suggested that key challenges here include:

-

dealing with service backlogs from COVID-19

-

expanding remits for public services

-

deciding what elements to retain from the pandemic response

Theme four: New expectations of leadership

During the pandemic there has been a big shift in the expectation of what the job of a public service leader entails. Many have become more involved in day-to-day management and communication with staff, dovetailing with pre-existing agendas around well-being, diversity and resilience. The growth of ‘blended working’ where some workers can switch between working in the office and at home is another facet of this change that has been accelerated by the pandemic. Research has suggested that key challenges here include:

-

exiting crisis mode: the impact on morale and turnover

-

blended working: the impact on culture and collaboration

-

external visibility and informal accountability for public service leaders

1.2 Workshop and interview findings

These four themes were explored in greater detail through workshops with GSCU staff and the GSCU Leadership Advisory Board members alongside three in-depth interviews with public service leaders. These stages served to validate the findings and provide additional depth on the role collaboration can play in resolving these issues and how the work within GSCU to support the public sector can contribute to this.

There was agreement on the central importance of collaboration (see the model on p18), with many providing examples of effective short-term collaborations created in the face of the pandemic. It was felt that collaboration was also an important solution to dealing with longer-term issues, but the current situation makes it more challenging to focus on these forms of collaboration, which are likely to be more formal and require more preparation and a greater investment of time. But the pandemic has reaffirmed existing thinking that dealing with longer-term factors like inequality requires a holistic or systems approach that reaches across the traditional sectors of the public services, which requires public services to act in a more collaborative way:

Public service leader, Local Government:

I think [collaboration is] 100% the answer. Complex needs, the way people live their lives holistically, all those sorts of things, I just don’t see how multi-agency working can’t be a far stronger part of the future answer because we are going to need to work across those agencies to find those integrated solutions

Collaboration was also an important element to all other factors which were discussed as ways to help public service leaders deal with future pressures. For instance, prevention and early intervention was identified as a similarly important factor as it can help avoid issues that might require collaborative solutions from developing in the first place – but prevention is also reliant on collaboration as it frequently relies on joined-up thinking between services. Many service innovations developed over the past year were similarly considered to have been the product of greater collaboration. And locally-led responses to the pandemic, which were seen by participants and in the evidence review as being more responsive to circumstances than centrally-run efforts, were similarly helped by the collaborative working of different services.

The research also pointed towards further questions for research on the nature of collaboration between public services:

-

defining better what collaboration between public services is so that it can be assessed more easily

-

understanding the circumstances where more collaboration might be less effective

-

investigating how the focus of public service collaboration can be made more proactive

It also suggested some different roles the GSCU’s public sector facing teams could play in fostering collaboration

-

linking the short term and long term: providing a space where longer-term issues can be considered away from the day-to-day demands of leaders’ jobs and they can speak with their peers

-

connecting the central and local: preparing leaders for the challenges of a future where public service workers in some sectors might be more geographically dispersed and greater use of public services online reduces the volume of in-person interactions

-

providing a voice for leaders: ensuring leaders’ experiences are heard by communicating best practice and case studies to inspire others and celebrate the success of public service leaders, or acting as a convenor of leaders’ views and facilitating collaboration between leaders and policy-makers

-

as a safe space: with growing focus on well-being for leaders, the GSCU could provide informal opportunities for leaders to deal with the pressures of the job, creating a space for them to learn and share experiences

2. Introduction

This report details the findings of a project carried out by Ipsos on behalf of the Government Skills and Curriculum Unit (GSCU), a part of the UK Government. The aim of the project was to assess the pressures facing leaders of public services currently to understand the driving factors behind them and chart how these pressures might develop over the next few years. This is part of an ongoing series of research into senior leadership which informs and improves the GSCU’s offer to public sector CEOs.

The COVID-19 pandemic has had far-reaching impacts on the type and volume of work facing different public services. Understanding how far this has affected the existing pressures public service leaders were already dealing with – and whether it might produce new issues – will be of great importance to the GSCU as it makes plans for the Leadership College for Government’s Programme, Network, Engagement, and Research & Evaluation workstreams over the next few years.

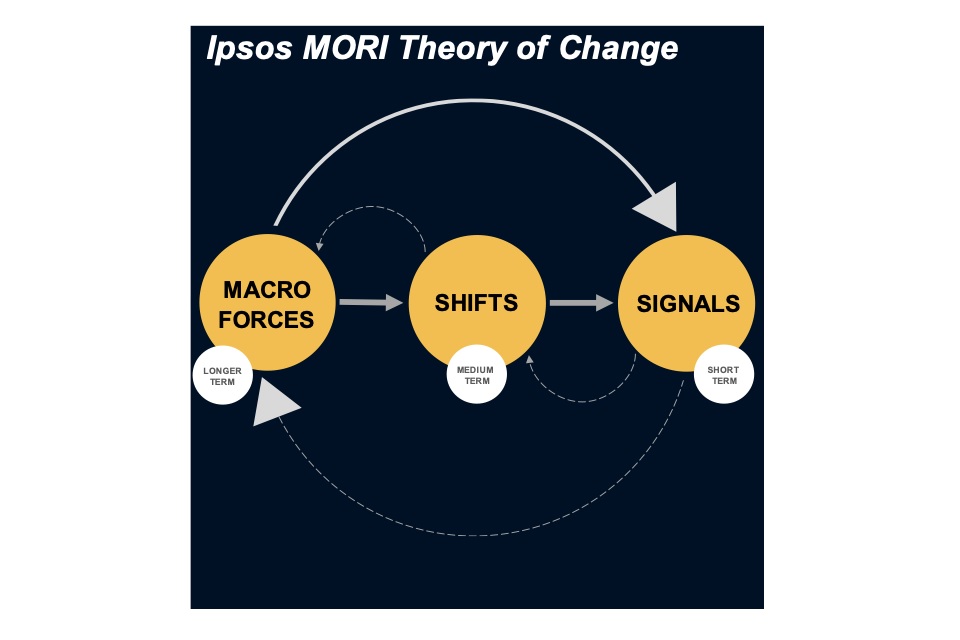

2.1 The Ipsos trends framework

This project was conducted using Ipsos’ trends framework – our theory of change for defining how societies change, and what is worth monitoring. This centres around three interlocking forces:

Macro forces: Planetary-scale changes which are already underway and whose influence is felt by countries, companies and people alike.

Social shifts: Culturally specific, value and belief driven responses to the prevailing pressures facing citizens and consumers. These operate at the society level and influence the PESTLE analysis which is a structured way of examining the political, economic, social, technological, legal/regulatory and environmental aspects of society and systems.

Signals of the Future: Tactical responses from countries, individuals or organisations that tend to emerge as tensions, changes and opportunities. They are driven by – and can shape – the context of Macro forces and Social shifts.

This three-tier approach means analysis is conducted from the top down, incorporating high level global changes, as well as capturing bottom-up innovations and examples of change. This ensures a wide range of evidence is considered when identifying the middle-level drivers of change that will have influence over the next few years. Ipsos also has access to decades of social, political and consumer polling which is fed into the model.

2.2 Methodology for this project

Using the Ipsos trends framework, Ipsos and the GSCU worked together to produce a framework of bespoke “drivers of change”. Drivers are concepts or ideas which encompass the key unanswered questions or tensions in a given sector – one example might be an ageing workforce, or changes in social attitudes. They are useful for strategic thinking because considering the alternative answers to these questions allows organisations to think about how the future might develop and the steps they can take to anticipate it, or shape how it turns out.

The aim has been to provide a high-level overview of the potential directions for public services over the next one to three years. The analysis intends to act as a base for strategic thinking by the GSCU and Leadership Advisory Board, as well as the leaders who populate its networks and programmes.

The key stages of this project are detailed below:

Alignment workshop: An initial workshop between Ipsos and GSCU surfaced current GSCU hypotheses and thinking about the pressures on public service leaders, and the impact of the pandemic. This stage was vital to ensuring that the scope of the project was set correctly through building an understanding of the existing knowledge among GSCU members, developed from direct and indirect interactions with public service leaders. It also helped to define the types of literature sources which would be used for the next stage of the project.

Source review and initial analysis: Ipsos then conducted a rapid evidence assessment of relevant sources. Key search terms[footnote 1] were agreed with the GSCU after the alignment workshop and these were used as the basis of internet searches through publicly available sources including Google and Google Scholar. In total, 112 sources were identified across the GSCU’s six public service categories (healthcare, emergency services, Civil Service, education, local government and other/multiple sectors) and 51 were prioritised for detailed review based on their relevance to collaboration and the pressures facing public services. During the detailed review each source was read fully, with key insights and implications for different public services identified and stored in a single Excel document. These sources included grey literature from think tanks, academic reports from government and other sources, insights from consultancy firms, survey reports and polling, journalism and opinion pieces as well as other sources. This review fed into the first, internal, drivers analysis session. Ipsos utilised the six categories in PESTLE analysis[footnote 2] to consider the impact of the literature and data on the public sector and the role of its leaders. The result was a set of hypotheses, questions and statements clustered around core uncertainties.

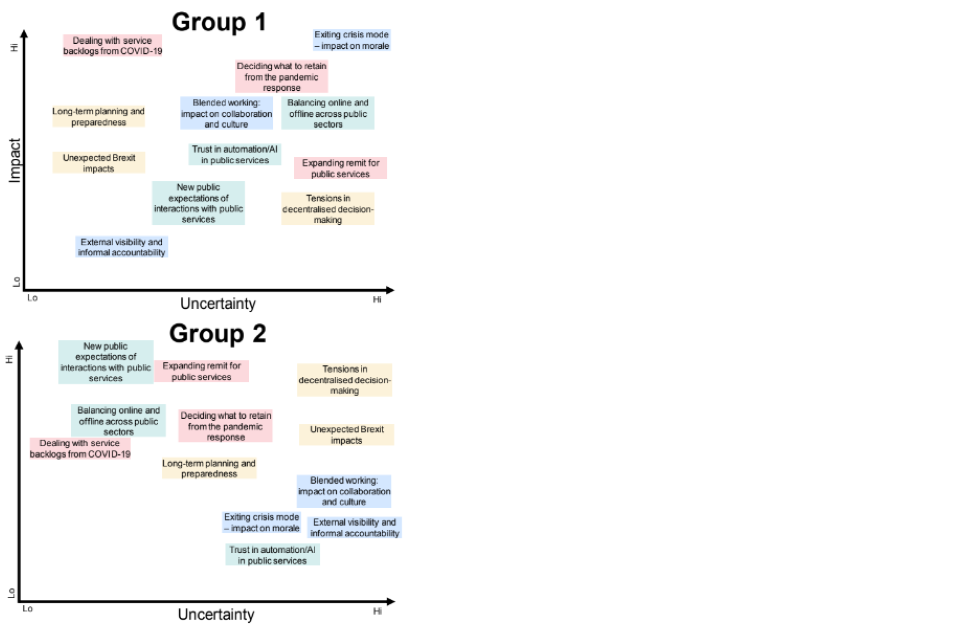

Driver analysis: An internal analysis session was held by the Ipsos team, where the hypotheses, questions and statements coming out of the literature were discussed and linked together. These clusters of findings were physically mapped into a smaller number of cross-cutting drivers of change. Drawing on similarities between hypotheses from different parts of the analysis, twelve drivers of change were created. These twelve drivers were nested within a framework of four narratives that shape the future of public services in the UK.

Prioritisation workshop: The GSCU and Ipsos held a joint workshop to test the framework. Each driver was introduced, and a discussion was held to examine what was missing and what the impact of each driver might be on the sector. The drivers were rated for how big an impact they might have on the work of public service leaders and the level of certainty participants had about this impact (i.e. how predictable they felt the likely impacts would be). The workshop also considered what the role of collaboration between leaders might be in helping to resolve issues caused by these drivers and where the GSCU might best be able to contribute.

Scoping interviews: Following the workshop, depth interviews were held with three public service leaders to discuss their perspectives on current and future pressures facing them and understand how these fit with the drivers generated during the workshops. The interviews were also used to test the findings from earlier stages in the research and to provide first-hand opinions of how collaboration can provide answers to key pressures and the role the GSCU’s public sector facing teams can play in these solutions. Quotes from these interviews are used throughout the report to evidence the drivers and findings.

2.3 Interpreting this research

This research exercise was conducted primarily using secondary sources, with a small number of qualitative engagements including workshops and depth interviews.

The scope of the evidence review was to look at recent sources from March 2020 to build a picture of the longer-term challenges facing the public services. In the fast-moving context of the COVID-19 pandemic, this may mean new sources have emerged which were not included at the time.

The qualitative workshops and depth interviews are not designed to be representative of the wider population of public service leaders, but instead to highlight the range of experiences and views this audience holds as well as some initial views of the secondary analysis.

3. Current pressures facing the public sector

The research first focussed on gathering evidence on the current pressures facing public service leaders from the perspective of both the GSCU and leaders themselves. The evidence review built on these foundations by exploring research and evidence on this topic from the past few years, with a focus on the pandemic period from March 2020 onwards.

Initial hypotheses from the team were discussed at an alignment workshop at the beginning of the project, which included discussions of the issues being faced by public service leaders drawn from both formal and informal interactions with them. This was supplemented with additional sources summarising the view from leaders, including topline results of an GSCU year 2 baseline delegate survey from September 2020. The key points from these sources were reviewed, summarised and combined to create a list of key current issues.

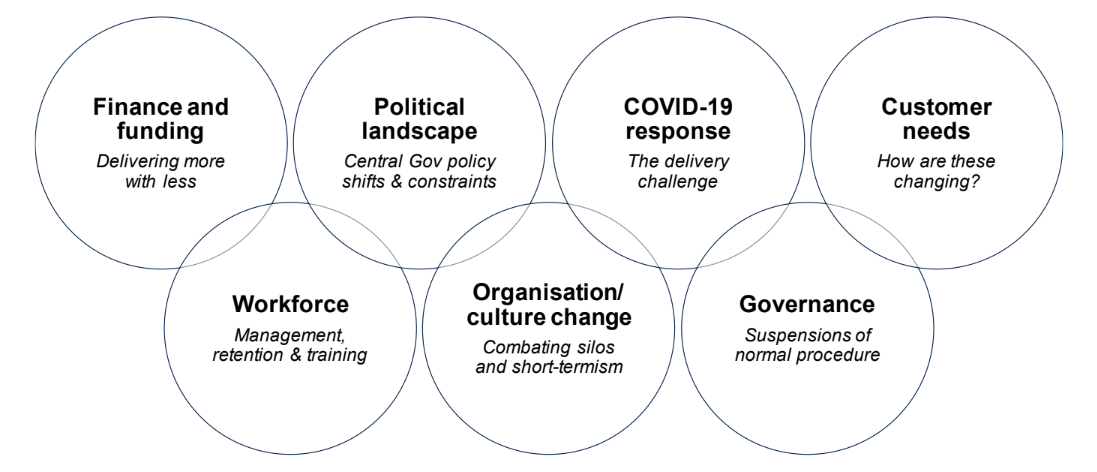

This chapter presents a consolidated summary of the key themes derived from the evidence review and PESTLE analysis, covering seven key areas of existing pressures facing public service leaders. These areas are built on the key areas of importance identified by leaders in the GSCU’s delegate survey and also incorporate discussions from the alignment workshop and elements of the subsequent evidence review. The intention is to provide a top-level view of where current pressures on public service leaders are and the drivers behind them.

An important finding from across the research has been that while the pressures facing public services have been broadly uniform across the public sector, the issues which result from these pressures can be highly specific to the sector in question. This is reflected in a table towards the end of the chapter, which outlines sector-specific impacts that have been observed in recent literature.

Figure 1.1: Important current pressures for public service leaders

Figure 1.1: Important current pressures for public service leaders

3.1 Finance and funding

Overall the reviewed literature suggests that finance and funding have long been concerns for leaders, particularly in sectors such as social care, local government and further education. Public service leaders have long dealt with pressures to maintain or improve service delivery with current budgets, resources and workforces. In addition, finance and funding was the most commonly cited issue in the GSCU delegate survey from September 2020.

During the pandemic, Central Government made funding available to ensure continued delivery of key services, whether essential face-to-face delivery or setup of remote working. Projections from organisations such as the Institute for Government suggest that public services will face spending restraints in future to repay the unprecedented levels of borrowing during the COVID-19 pandemic.[footnote 3] This is reported to have implications for clearing backlogs while maintaining service quality[footnote 4] and for collaborative organisational structures, with some public service delivery increasingly expected to be undertaken by third parties or charities in future in response to financial and funding challenges.[footnote 5]

Public service leader – Healthcare:

I think that is obviously going to come round in the end, so paying for it is going to be an issue for us all, and that is clearly going to throw all sorts of constraints back in the system

3.2 Workforce: management, retention and training

Medium- and long-term issues relating to the recruitment, management, training and retention of staff also feature strongly in the literature regarding current issues facing leaders.

Public service leader – Emergency Services:

If I’m honest with you, people are just tired. They just haven’t stopped and that is a big issue for us… It’s not our core business, but when you get a phone call on December the 27th from the local authority and the health authority saying, ‘We need help setting up a vaccination centre, have you got anybody that can help us?’ you’ve just got to respond

Institute for Government (IfG) analysis suggests that In some public sector areas including the Civil Service and police, a long period of workforce cuts over the past decade followed by a rapid increase in new hires means that these services may face a leadership and institutional knowledge gap in the medium term as current leaders leave their posts. This has been a particular focus over 2020, a period which saw numerous Civil Service Permanent Secretaries leave or change roles.[footnote 6] While bringing in new leaders from other public sector areas enables learning from different sectors and approaches to budgeting[footnote 7], leaders also need time to develop familiarity with sector-specific issues and challenges, often drawing on institutional memory[footnote 8]. Looking further into the future, beyond the scope of this review, the UK’s ageing population is expected to exacerbate this problem by reducing the supply of younger workers, making it harder to build up a depth of institutional knowledge that can adapt to future challenges according to the Centre for Ageing Better[footnote 9].

Recruitment and retention of staff across the public sector are also seen to be current challenges facing leaders. For example, the current government’s ‘levelling up’ agenda, in part a response to increasing regional inequalities, aims to increase opportunity across the country and tap into new sources of skilled workers. But the IfG suggests that this process will entail some disruption as the Civil Service becomes significantly less centralised over time: they estimate that currently two thirds of policy makers are based in London at present[footnote 10]. In the health and social care sectors, there is also a reported concern about the longer-term impacts that EU exit may have on the ability to recruit staff from abroad.[footnote 11]

Redistributing or increasing staff numbers also raise issues around training, upskilling and the impact on service delivery downstream, for example, the provision of training 20,000 new police officers and the impact such an increase will have on the criminal justice system’s ability to cope with case numbers.

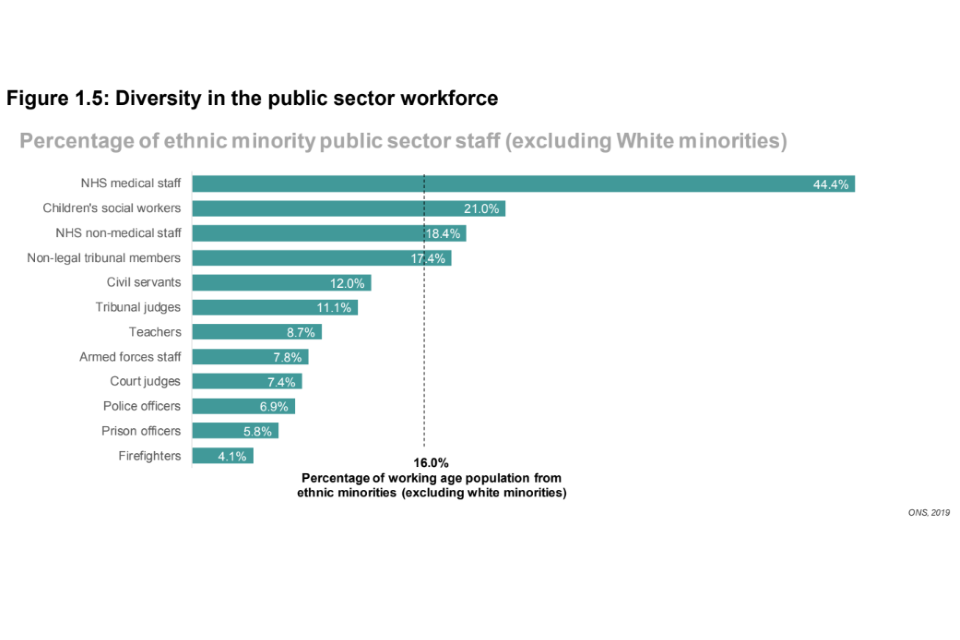

Finally, the COVID-19 pandemic and long-term social trends have focused attention on staff wellbeing, mental health and diversity, as well as issues such as flexible working arrangements. This is expected to play an increasing role in an organisation’s ability to attract and retain staff.[footnote 12]

3.3 Political landscape

The political landscape leaders operate in was the third-biggest group of concerns for leaders reported in the GSCU’s year 2 baseline survey. The COVID-19 pandemic and EU Exit are both recent examples of events which have challenged established norms in how policy is made, although both have brought greater focus on the need for developing contingency strategies.[footnote 13]

These changes present new questions for how public service leaders and business leaders plan for the future. As will be explored later in this document, while the pandemic has distracted attention from it, some analysts suggest that the implementation of the EU Exit agreement is likely to present implementation issues into the medium term, relating to legal and policy changes concerning the environment, climate change and data protection.

Public service leader – Emergency Services:

[With] emerging technology, there is no real regulation in terms of safety… which government department or which part of government will be providing the regulation? Because previously… it came through EU regulation then into our regulation

There has also been devolution of power to national and regional administrations which has highlighted differences in approach and performance during the pandemic period, for example, differences in lockdown and travel restrictions between England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. It is also expected to draw political attention to funding issues in certain sectors, particularly in health and social care, given regional deprivation-related disparities in mortality rates from COVID-19.[footnote 14]

3.4 Organisational culture change

Issues around organisational culture were highlighted as an important issue for public service leaders by the GSCU teams and by the leaders themselves. Factors including issues of short-termism and “silo” mentalities in the public sector also featured in the literature.

Public service leader – Local Government:

We’ve established, as much as we can, a single set of terms and conditions for [region] public service workers, so people can move from one local authority to another or from the health service into the local authorities and maintain their continuity of service. So, I mean, it’s not harmonisation but it’s [overcome] one step that was stopping people moving

A paper by the King’s Fund reports that the main issues with a silo mentality (which is often reflective of the way budgets are distributed to individual organisations) are that it discourages collaboration between services resulting in unnecessary competition, duplication of efforts and inefficient use of resources.[footnote 15] In addition, short-term policies, commissioning processes and funding structures were reported to create barriers for longer-term collaboration and organisational change by discouraging innovation and risk-taking.[footnote 16] There was also criticism that current service evaluations did not recognise the time taken to implement changes or to see results in some cases.[footnote 17]

Evidence from the review and discussions with GSCU suggest that the pandemic accelerated key elements of organisational culture change such as more flexible working arrangements, greater focus on staff welfare, flatter structures, greater frequency of internal communications, and less of a ‘blame’ culture. At the same time, there was a recognition that such pace of change (and some of the changes) may not be possible to maintain under normal circumstances.[footnote 18][footnote 19]

3.5 COVID-19 response

Responding to COVID-19 was highlighted as a key issue for public service leaders by the GSCU team as well as in the survey of public service leaders from September 2020. However, in this survey it was the fifth largest concern behind key factors including culture change, funding and the political landscape. This may be in part a factor of the timing of the survey – between waves of the pandemic – but it also shows that more persistent issues of staffing, funding and politics continue to be front of mind for leaders, even during an emergency.

The COVID-19 response for leaders has been reported to be in large part a delivery problem. A key consideration at the start of the pandemic was how to operate essential services (including any additional services as a direct response to COVID-19) while shifting rapidly to new modes of working or management.[footnote 20] This included the rapid shift of services online, establishing the necessary infrastructure for working from home or in COVID-secure workplaces, and adopting ‘control and command’ structures for decision-making.[footnote 21]

Public service leader, healthcare:

I actually do a daily notification and in the early days of the pandemic, I did it seven days a week. Things were so volatile but it’s probably been one of the game-changing things that I’ve adopted in a sense of you can never overdo [communication]

Other issues included concerns over the clarity and consistency of communications from central Government, an example reported by the BMJ.[footnote 22] This was highlighted during the pandemic as they were seen to result in increased uncertainty and time pressure for public services to implement new policies and strategies. Public service leaders praised the efforts of their workforce but noted workforce mental health and resilience were key challenges both now and looking forward.[footnote 23][footnote 24] Finally, the Institute for Government highlights that COVID-19 is likely to remain part of life for the foreseeable future, raising questions about public sector resilience to future variants and restrictions on daily life, despite the processes that have already been implemented.[footnote 25]

3.6 Governance

The evidence from the review described how the emergency response to COVID-19 resulted in the suspension or reduction of normal governance processes in many areas of the public sector to enable swifter decision-making.

For instance, the King’s Fund found that an immediate impact was that reduced governance generally led to less risk-aversion and more innovation, which facilitated rapid collaboration among public services and between the public, private and voluntary sectors.[footnote 26] Other evidence sources highlighted the improved efficiency and speed of more streamlined decision-making processes.[footnote 27] There were recommendations to take these learnings forward and to encourage greater delegation of decision-making and accountability, for example, to local government, but there were challenges highlighted by the evidence review about how to retain the benefits while at the same time not risking a loss in transparency, creating barriers to information flow or facilitating unintended consequences.[footnote 28]

In discussions with leaders, concerns around increased scrutiny were raised, especially the prospect of an official inquiry into the UK pandemic response. The potential for scrutiny of the COVID response (without also acknowledging positive lessons learned and the challenge of decision-making without full information) in the post-pandemic period was felt to have implications for personal careers, public trust and attracting a new generation of public sector leaders in the future.

3.7 Customer needs and expectations

Public service leader - Healthcare:

I suppose the difficulty would be that the agenda has been relatively binary over the last eighteen months, hasn’t it?.. That’s not to say that nothing else has mattered but there’s been very little else on the stage and the public opinion of that has shaped policy as much as the science has driven policy, I suspect

The changing needs of service users were not considered to be one of the key issues by public service leaders directly. However, understanding and anticipating how public attitudes and expectations change was agreed to be an important area of interest by the GSCU, the challenge being building public trust, aligning services to the public’s priorities, and how to encourage increased engagement from the public in service design and delivery.

Polling suggests that the public continue to value and appreciate the NHS above other services; two thirds of the public said they appreciated hospitals more since the arrival of the pandemic,[footnote 29] and it remains the public’s top priority for further funding. Public service leaders interviewed for this project also saw greater efficiencies as part of providing more resource for the health service, which are likely to require an expansion of existing roles, embedding of digital solutions and greater collaboration between public service areas and third-party organisations.

Existing evidence shows a nuanced picture on the acceptability of using public data dependent on the organisation using it. For instance, trust in the NHS to use personal data appropriately stood at 42%, compared with 19% for local authorities and 18% for the UK government.[footnote 30] There is also nuance to what type of data is being used, with information about sexuality, ethnicity and educational attainment being more acceptable than data about income, personal health or travel.

Satisfaction with services is currently static or improving slightly – two thirds were satisfied with their local council in February 2021, slightly above pre-pandemic levels,[footnote 31] while 2020 GP Patient Survey data showed satisfaction above 80%, as it had been in 2018 and 2019.[footnote 32] It remains to be seen if these scores can be sustained as the country moves into a recovery.

3.8 Key pressures – by sector

The table below summarises the key challenges facing public service leaders across the main sectors the GSCU supports. This is drawn from the preceding chapter and provides a short outline of how current pressures translate across public service sectors

Current issues facing public services – potential sectoral impacts

| Overall | Civil Service | Healthcare | Emergency Services | Local Government | Education | Other (Transport, military, courts) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Finance and funding | Delivering services within budget | Clearing health backlogs; mental health funding | Reduction in police and fire stations | Delivering services with more demand and less budget | ‘Lost learning’ and funding of higher education | Clearing court backlogs | |

| Workforce | Ageing workforce; mental health; skills gaps; collaboration; diversity; working from home | Decentral-isation; digital skills training; leadership and institutional knowledge gap | Nursing and social care gap; burnout | Impact of hiring new police officers; burnout of emergency responders | Increased devolution and local leadership; increased collaboration | Expecting increase in teachers; decline in gender diversity | |

| Political landscape | EU Exit; devolution and levelling up | Potential for new EU Exit impacts | NHS Five Year Plan; increased attention on social care sector | Recruitment of police officers | Pressure to increase national and regional devolution | ||

| Organisational culture change | Collaboration; flat structures; delegation; risk aversion | Silo structure and inter-department competition | Increasing need for long-term commissioning to meet increasingly complex needs | Collaboration between emergency services | Greater autonomy; developing mission-oriented policy | More internal communication; maintaining transparency | |

| COVID-19 response | Working from home; rapid online shifts; collaboration; future variants | Digital infrastructure; inter-departmental data sharing | Collaboration with voluntary sector | Mental health; support for responders and families | Maintaining benefits of local decision-making | ‘Lost learning’; child vaccination programmes | Ongoing effects of COVID; unemployment among 18-30 year olds |

| Governance | Risk aversion; streamlining decision-making; future accountability; attracting future leaders | Maintaining benefits of streamlined governance and procedures | Maintaining relationships with voluntary or third-party sectors | Maintaining relationships with voluntary or third-party sectors; decentralisation | Concern about post-pandemic inquiries | ||

| Customer needs | Increased demand; increased complexity; public trust; public perception | Improving service standards; encouraging public participation in government | Increased demand on mental health services; increased complexity of cases due to backlogs and ageing | Updating public perceptions of emergency services’ role; increased complexity of cases with increasing use of digital evidence | Encouraging public participation in local government; housing and unemployment | ‘Lost learning’ and impact on future prospects Educational inequality |

4. Introducing the themes

The next chapters of this report provide an overview of the four themes which emerged as important drivers of the future issues likely to face public service leaders. Each theme contains three drivers of the future which were identified through the PESTLE analysis, combining these with the evidence review and alignment workshop to form four themes:

-

Moving public services online

-

The changing role of the state

-

Rising complexity

-

New expectations of leadership

Each theme chapter provides a background, highlighting how they have developed over the preceding years. It then focuses on the evidence gathered during the pandemic and reflects on how these themes and the drivers within them have been accelerated during this time. The second half of each chapter outlines the drivers themselves; reflecting on how current developments might shape demands on public services leaders of the next few years and posing some questions for public services leaders to consider when thinking about how they could prepare and respond.

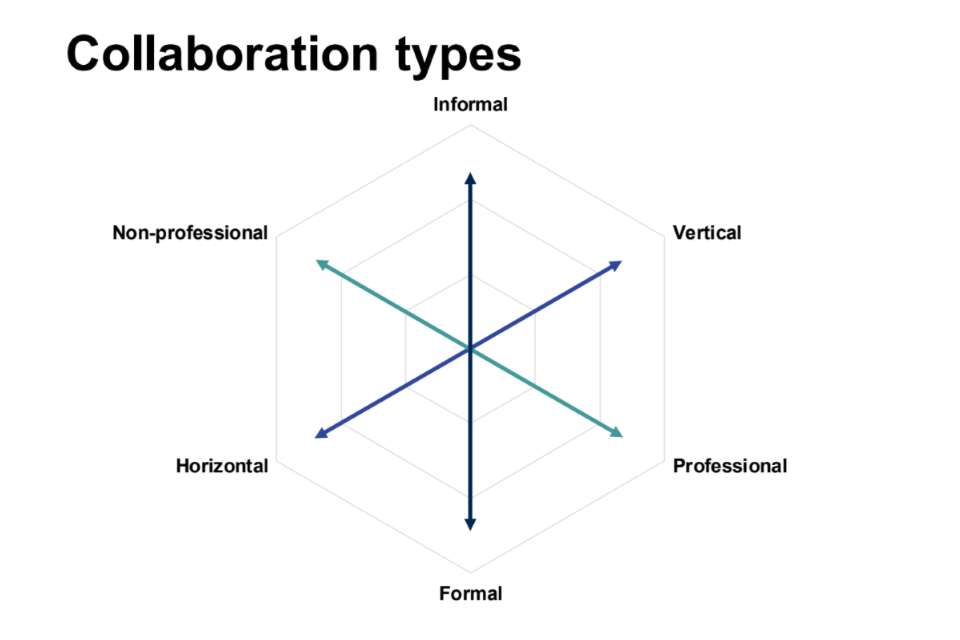

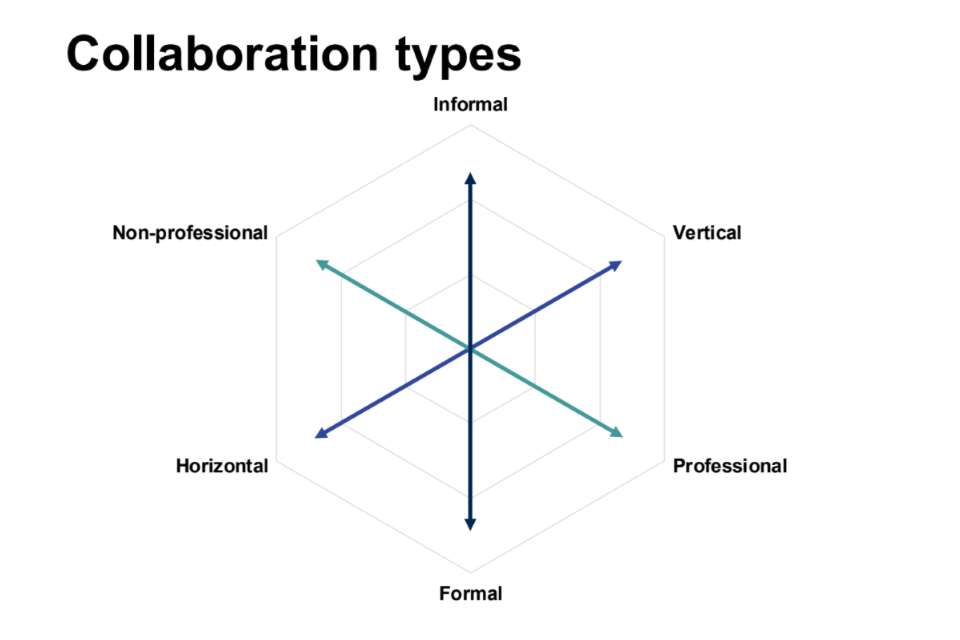

The theme chapter ends with a consideration of **the role collaboration can play in meeting these challenges, based on the evidence review and internal workshop. Collaboration is a broad topic that can be envisioned in a variety of ways. The definition used by the Leadership Directorate (a team within GSCU) focuses on targeted cross-sector working between senior professionals, but there are also many less directed and informal ways to collaborate. The evidence review identified three important dimensions that outline different ways collaboration can be described:

-

formal (for instance, through contracts and joint commissioning) to informal (conversations outside of formal or work-based forums)

-

horizontal (between leaders of different services) to vertical (collaboration with those above and below a leader in the same organisation)

-

professional (with policy-makers, strategists and contractors) to non-professional (with the public and service users).

5. Theme 1: Moving public services online

There has always been pressure to make public services more responsive and efficient and the pandemic has provided an opportunity to explore new ways of responding. Making greater use of data and upgrading of services are two areas of long-standing interest where COVID-19 has driven significant progress.

Similar shifts have been occurring across society and in the private sector. The impact of these changes may shape public expectations of how they want interactions with public services to look and feel. Further, decisions made now about how to move services further online will shape how they are provided physically, as well as the physical settings in which they are provided.

5.1 Background

Improving the use of technology and data in public services has been a goal for successive governments over the past few decades, yet it is also an area marked by high-profile challenges. Reported issues include public trust, buy-in from those who will be implementing these new systems, rising costs and use of contractors, as well as capacity within the public sector to deliver digital transformation successfully.[footnote 33] According to the BMJ, a combination of these factors, including public trust and low support from doctors, halted the NHS ‘Care.Data’ programme earlier in the previous decade.[footnote 34]

As reported by the Institute for Government, the greater use of data and technology promises to increase the efficiency of public services and help with many of the issues faced by public service leaders: for instance, improving efficiency through greater use of technology can help respond to the pressure to meet user needs and deliver policies better, with less funding.[footnote 35] As a result, it remains an attractive aim for politicians and leaders alike.

In the pre-pandemic period, greater use of these technologies encountered obstacles of public acceptance and digital exclusion which remain significant:

-

evidence from late in 2020 suggests that public views on the use of data have not changed and remain as fragmented now as they have been for some years,[footnote 36] meaning that making the case to the public for greater use of these approaches will continue to require a nuanced approach – for instance the Institute for Government notes that while four in five would be comfortable with AI helping a doctor with their work, just one in five would be comfortable with AI being used instead of a doctor.[footnote 37]

-

while the proportion of the UK public connected to the internet increased in 2020 (from 93% to 96%[footnote 38]), digital exclusion remains an obstacle: and with many school children learning from home, frequently on unsuitable mobile devices,[footnote 39] it has been revealed as not an exclusively generational divide.[footnote 40]

A move to greater use of data also has implications for the workforce who may be required to learn new skills; research by the World Economic Forum suggests that 40% of workers worldwide will require reskilling for their employment,[footnote 41] and the technological capabilities of public sector workers is an important concern for existing public service leaders.[footnote 42]

5.2 Trends revealed and accelerated by the pandemic

The literature reveals how the pandemic has forced many transformational changes on how public services are delivered and revealed shortcomings across all sectors of the public services.

Public service leader, Local Government:

If you said to our IT people here, ‘Can you just make 2,000 people work remotely overnight, by the way, and do that for the next eighteen months, and not have a single outage,’ then they would have gone, ‘No, it’s absolutely impossible, we just don’t have the resilience in the system to do that, no chance’. But we did it

Research by Deloitte highlighted two related issues for Civil Service leaders: firstly, that data literacy (being able to interpret and present data coherently) among officials remains an area for improvement if the Government is to make better use of data.[footnote 43] The second issue was sharing data between Departments, which can be restricted by legal obstacles, differing standards and technical ability (of software and personnel). Limited interoperability between Departments of the Civil Service was highlighted by Institute for Government analysis which revealed how default web conferencing platforms varied between departments, resulting in some being unable to speak with each other.[footnote 44]

Obstacles also emerged in the way citizens were able to contact Government departments during lockdowns. An Institute for Government paper on digital government under COVID-19 finds that pre-existing digital identity services – used to confirm a person’s identity before they can access information including their tax and driving records online – struggled to respond to increased demand under the pandemic.

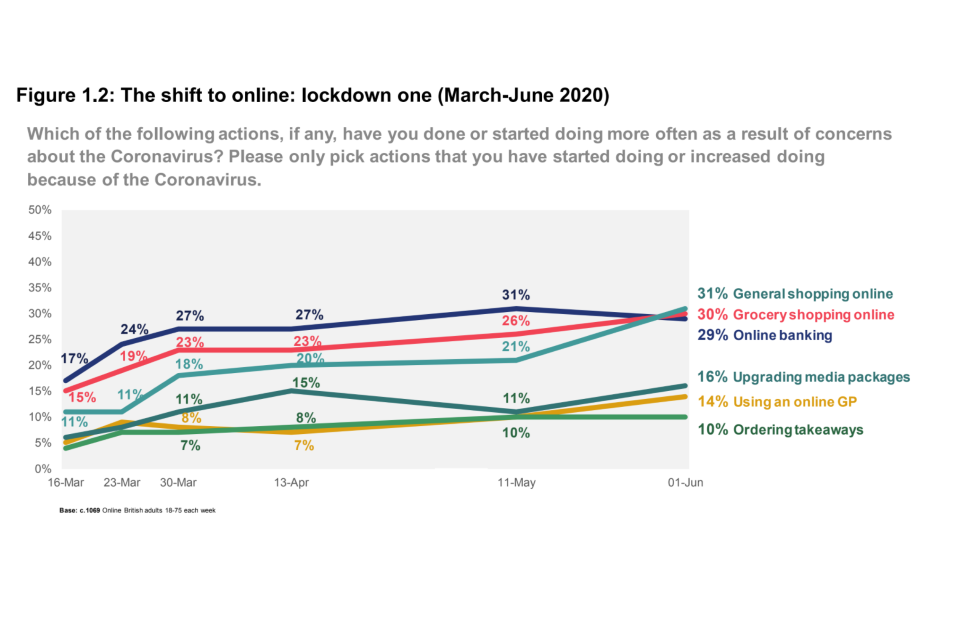

The pandemic has also accelerated digital transformations for both public and private sectors. For instance, between March and June 2020 the proportion of the British public accessing GP services online for the first time (or more often than they were doing so before) more than doubled. Also, web-based consultations with GPs rose from being a small proportion of all appointments in February 2020 to account for around half of all appointments by June. In education, the DfE made £100 million available to ensure that children with inadequate access to computers and the internet at home were able to participate in online learning, which almost all children and parents across the country were required to participate in as schools were closed during some of the lockdown periods.[footnote 45]

The shifts appear to be greater still in the private sector, with levels of online grocery shopping doubling and a tripling in the proportion doing general shopping online for the first time or more often. This shift online is having significant impacts on local high streets: an existing trend of business closures has gathered pace as weaker retailers struggle to cope with enforced closures and the shift to online sales, resulting in more than 11,000 shops closing across Britain during 2020.[footnote 46] As the country opens up again it remains to be seen how the reality of these closures will influence how people move around their local areas, and the impact this might have on the siting of public services in future.

Public service leader, Local Government:

The decline of our high streets has been massively accelerated by COVID, and we’re going to have to find new solutions for those issues

Figure 1.2: The shift to online: lockdown one (March to June 2020)

While all of the public have been forced to access public services in a new way during the pandemic, their reactions to this shift have differed. While some have been excluded, for others the shift could be convenient and is a way for them to fit necessary appointments into a busy lifestyle – as has been found in previous evaluations of remote GP services.[footnote 47] This suggests that some members of the public (typically younger) would be interested in continuing with some online appointments for many services even beyond a pandemic period. But this must be balanced with provision of in-person services for those excluded to avoid a two-tier system.

5.3 Future drivers in this area

Analysis of the trends and movements in this space highlight three drivers that may influence future issues for public service leaders.

New public expectations of interactions with public services

It is too early to assess how far the sudden behavioural changes we have seen during the pandemic will alter citizens’ behaviour into the medium term. However, the balance between the digital and physical interactions people have with all organisations looks set to be pushed more towards the former. With many shops in town centres closed for good, many town and city centres now have a great deal of vacant space – for instance, the outlets of now-bankrupt department store Debenhams alone are estimated to cover 13.6 million square feet.[footnote 48] How these spaces are filled will influence the purpose of public spaces over the coming few years, which may have implications for where the public expect to find public services in future.

Public service leader, Local Government:

Expectations of public services [are] going up in line – almost in line with – everything digitally. I can order something on Amazon and it’ll be delivered to my house probably tonight or tomorrow morning, but actually I can’t book to go and see my Councillor online

As a result, many private sector organisations are investing in their online presences and are aiming to reinvent how online interactions with their users are handled to make them easier and reduce friction. In this context the literature suggests we may see the public expecting a higher standard of experience from public service provision online than in previous years and this will have to be counterbalanced by ensuring face-to-face services are maintained for those unable or unwilling to use online methods.

Key challenges for public service leaders:

-

How can the public service workforce be trained to adapt to new, more online, methods of providing public services – and what options are there for those who cannot adapt?

-

How might a period of online service provision change the expectations of public service users? Who might benefit and who might lose out, and what can be done to protect those at risk?

-

How should public sector organisations ensure parity of access and joined-up experience between online and offline channels of their service?

Public trust in automation and AI in public services

Public trust is the other side of the equation in online service provision: most services will only be useful to the extent that the public are willing to entrust them with their information. Previous Ipsos research found that an important criterion of trust for the public sector specifically is ensuring that inequalities between users are not worsened through use of personal data due to increased use of technology.[footnote 49]

This has been corroborated by two examples of the use of data analytics in areas of everyday life during the pandemic: public alarm over the use of algorithms to allocate new housing across different areas of the country and to decide the GCSE results of schoolchildren in England. In both cases the algorithmic approaches[footnote 50] were abandoned and decisions were instead made by humans – even though later analysis suggests that while teacher-assigned grades were perceived to be fairer, they benefited children with graduate-educated parents and those at independent schools at the expense of others.[footnote 51][footnote 52]

Underlying attitudes to the use of data by the public sector have changed less than might be expected; data from Deloitte in August 2020 found 36% of the public agreeing that “we should share all the data we can [between Government departments] because it benefits the services and me” and 37% saying instead that this should not be done because the risks to privacy and security outweigh the benefits.[footnote 53] In 2014 the figures were 33% and 44% respectively – so while concern about privacy has fallen slightly, there has not been an increase in the proportion with a more positive view.

A great deal of work has been conducted around public perceptions and attitudes around the ethics of AI in health and other areas of government which outlines how public services can use these tools with public consent. In a post-pandemic world typified by greater use of AI and algorithms in providing public services, there may be more tension with a public whose view of the benefits and drawbacks of these methods has not kept pace with technological developments.

Key challenges for public service leaders:

-

In which sectors might the public become more accepting of the use of data analytics post-pandemic? What lessons are there for public services?

-

What messages do the public need to hear to understand the benefits of data-led public services?

Balancing online and offline across public sectors

As social distancing guidelines are slowly withdrawn, a consideration for all public service leaders will be the balance they want to strike in the future between online and offline delivery methods. Some may return to forms of service provision similar or identical to the pre-pandemic period, yet for others, this online experiment may have highlighted new approaches they will be keen to retain to help provide a more efficient service – although as yet there is little concrete evidence either way.

The potential for increased efficiency with online services will need to be weighed against the possibility that any moves further online will generate increased inequality. For instance, research by the Institute for Fiscal Studies shows that children with inadequate technology or parents who are unable to devote time to assist with remote learning have fared less well in education than others – and this has been an important reason for the prioritisation of face-to-face education as lockdowns are eased.[footnote 54]

For other services, such as GPs using online triage services to decide how to allocate face-to-face consultations, the balance between efficiency and inequality will be much more difficult to discern.

Key challenges for public service leaders:

-

What are the most important lessons from moving public services online during the pandemic?

-

How much pressure is there for different public services to return to their pre-pandemic modes of delivery?

-

How great an impact does moving services further online have on inequality of access to different public services?

5.4 The role of collaboration

The evidence review highlighted some ways that collaboration can be useful in helping public service leaders deal with current issues and prepare for those that might arise in the future:

-

Meeting changing public expectations of services. For instance, leaders can share best practice to help improve user experience. Formal collaboration on a single government identity service has been highlighted as an important development, and greater co-ordination between departments in using data will also require more formal channels for collaboration. The appointment of a Government Chief Digital Officer may also strengthen collaboration between the Government Digital Service and other elements of public services, and it may also strengthen horizontal collaboration.

-

Addressing gaps in public faith in AI and automation. More formal methods of linking services across sectors can help to make the case for greater use of technology though ensuring effective delivery of services and relevant communication of the benefits.

Public service leader – Local Government:

I think the other thing is not just about digital delivery of services, it’s actually about data and data sharing as well… if you look at what Transport for London have down in terms of making their data freely available, and then a number of apps that are then being developed off the back of that, and actually using the data that they hold to drive economic activity. And then there’s the inter-agency collaboration via data point, so you’re getting a holistic picture of an individual from multiple agencies

Factors beyond collaboration which may have importance for drivers within this chapter include greater emphasis on access and outreach in service redesign. In the future, members of the public who are most at risk of being digitally excluded will be those who do not use online services, by choice or for reasons of access. While some can begin to use online services with the right educational and access resources, maintaining equality of service for the small population who can or will not cross the digital divide may require factors other than collaboration. Additionally, as different public service sectors are likely to reach different balances between online and offline services, the lessons learned by some services may not be directly useful for others (for instance comparing the Civil Service with schools).

Other important factors beyond collaboration include training to ensure public service workers have the right skill sets to provide online and offline services and ensuring that public services have the facilities and real estate to match how their job roles might change in a blended future. For office-based workers this might mean less office space and more collaborative areas, while spaces for those working in frontline services might need to be adapted to cater to the types of users who will continue to access services face-to-face.

An example from HMRC shows how resources and building staff capability within the department was an important element in its successful pandemic response: it had laid the groundwork for a rapid shift online through previous work and recruitment of a large pool of digital experts. This meant that when required to adapt many of their services to be online-only under the pandemic, the department was able to respond quickly.

6. Theme 2: The changing role of the state

Even before the pandemic, wider currents in public opinion have tended towards greater support for higher levels of government spending and intervention.

The experience of COVID-19, combined with the ongoing implementation of the EU Exit agreement and greater expectations from the public, suggests a potential for growth in the remit of the public sector across a wide range of areas.

6.1 Background

Before the pandemic controlling public spending has been a focus for successive governments, with savings being made in many areas outside of education and healthcare. By early 2019, the Institute for Fiscal Studies estimated that £40 billion had been removed from Government Department budgets since 2010, with some areas experiencing reductions of 30-40%.[footnote 55]

Perhaps the most notable trend has been the fact that public satisfaction with many public services has remained static over this time. For instance, between 2010 and 2019 around six in ten of the public said they were satisfied with the way the NHS is run,[footnote 56] and the proportion expressing satisfaction with local councils has been between three quarters and two thirds between 2012 and 2021.[footnote 57]

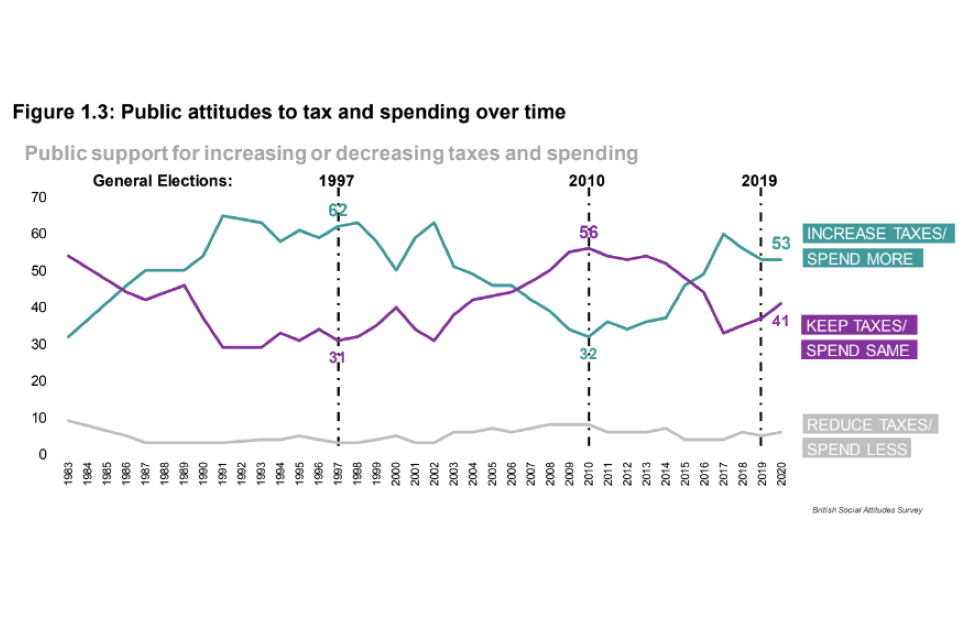

Many reasons have been proposed for why there has been a weak relationship between satisfaction with public services and budget reductions over this time. One is that spending restraint was broadly popular with the public at the time it was introduced: data from the British Social Attitudes Survey shows that in 2010 almost six in ten Britons were in favour of keeping taxes and spending on health and social benefits the same, rather than increasing them.

However, since then there has been a significant shift in public views, with a growing proportion advocating higher taxes and spending. Importantly, this increase predates the pandemic; in 2019, 53% were in favour of more tax and spending from the UK government and this proportion did not increase further in the COVID-era 2020 wave of the survey.[footnote 58] This suggests that underlying public value has been shifting for some time towards a more expansive view of the role of government.

Figure 1.3: Public attitudes to tax and spending over time

Other important background factors in this area reflect newer developments in other long-running debates about the role of government and the state:

-

The politicisation of advice and the role of experts: The balance between expertise and political appointees in government is described as having been under scrutiny since the Thatcher government,[footnote 59] and debates on this balance were given fresh impetus during the vote for exiting the EU.[footnote 60] Outside the EU, there is space for new policy to be formulated in areas such as agricultural policy and State Aid which were formerly the preserve of European decision-making processes.

-

A tension between long-term devolution of powers and the role of Central Government. Since the nineties, UK Governments have sought to devolve power, starting with the creation of the Scottish Parliament, Greater London Mayoralty and the Senedd in Wales in 1999. Later examples include the establishment of Police and Crime Commissioners in 2012, through to the establishment of a Mayor for West Yorkshire at the 2021 local elections.

Public service leader – emergency services:

So, what you get is a big announcement but no detail around it because that’s how big government works, it feels… If you’re going to go for [more interventionist central] governments then you’ve got to have the ability to do detail. If you’re going to devolve it, then devolve it

While some of this has been driven by the crisis response to the pandemic there are also examples of this tension preceding COVID-19, especially in debates on infrastructure such as the Cumbria Coal Mine,[footnote 61] the Cambo oilfield,[footnote 62] new Freeports in England or proposals for a tunnel to Northern Ireland.[footnote 63]

Public service leader – Healthcare:

Now with the new White Paper… there’s a duty to collaborate and we’re no longer doing work around [it]. So, I welcome that and I think that’s very helpful

6.2 Trends accelerated and revealed by the pandemic

Among the current factors influencing the changing role of the state has been the differential performance of public services under the strain of the pandemic. The Institute for Government Performance Tracker for 2020 showed that the extent of disruption from the pandemic – and the ability of services to respond – differed between the NHS, criminal courts, adult social care and education. Some of these impacts can be explained by structural factors, for instance, in criminal court cases requiring juries social distancing guidelines pose an additional obstacle by significantly reducing capacity.[footnote 64] There are also other factors relating to resources levels and the level at which decisions are made.

Under the pandemic, local-level decision-making has become an important factor in matters of devolution and decentralisation. This is particularly the case within England where the central and local governments have each had a role in public health – for instance, under the regional tiered system of restrictions during late 2020, tensions were reported between the UK Government and local governments (particularly the regional mayors of Manchester and Liverpool) over access to epidemiological data and decisions on tightening restrictions.[footnote 65]

It has also taken on a political edge in relations between the four nations of the UK. For instance, public opinion research from Ipsos showed that Scottish public opinion tended to draw a distinction between the First Minister of Scotland Nicola Sturgeon and the UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson on their performance in dealing with the pandemic,[footnote 66] although views of the UK government are more positive when it comes to the success of the vaccine rollout.

Research by the Institute for Government suggests that another part of this fragmentation of (real or perceived) performance under pressure is tied to the funding and workload for services prior to the pandemic as well as the extent of emergency preparedness planning in place. The police, NHS, local government (and to a lesser extent) the courts were more able to use existing emergency plans to respond quickly, while schools and adult social care were less likely to have similarly developed plans, which resulted in a slower response. Preparations for a no-deal EU exit were also identified as an inadvertent positive for public services’ disaster preparedness.[footnote 67]

A key point of acceleration under this theme fits around the current government’s “levelling up” agenda. The shift to home working under the pandemic offers the potential for greater flexibility in where many public service workers can work, by offering existing workers the chance to work at home for a greater proportion of the week permanently and by setting up new, more dispersed, offices for people to work from. There are examples of both of these at work: HMRC is updating the standard contract for its 64,000-strong workforce to offer two days a week homeworking as standard,[footnote 68] while plans to create a Treasury hub in Darlington and to push other public sector work elsewhere have been widely promoted. Some projections suggest that a greater emphasis on homeworking may also revitalise local high streets outside of big cities,[footnote 69] which has been a policy of the current government – especially after a pandemic which has threatened many of the traditional shops and stores that can be found in these locations.

The nature and speed of central government communications has also seen a shift, with some examples from education and local government of Government policy being announced on a Friday to be implemented the following week.[footnote 70] The speed with which new policies have been announced has sometimes been unavoidable, especially around the imposition of lockdowns, but it is also a function of how government weighs up different types of advice, which is explored in other sections of this report.

Public service leader – Emergency Services:

[You] have a position where the Chief Executive of the hospital is waiting for their health minister to announce something on television at five o’clock, to know what he’s going to be doing the next day

6.3 Future drivers in this area

Unexpected EU Exit impacts

During the pandemic, public service leaders’ key concerns (and the attention of the public more widely) have been focussed less on issues arising from the UK exiting the European Union. However, the Trade and Co-operation Agreement (TCA) is a long document governing a complex relationship, which means there is scope for secondary and unexpected impacts to arise – one example raised by the leaders was around the regulation of emerging energy technologies:

Public service leader – Emergency Services:

We’re just facing something at the minute in terms of [solar farms] where there’s big batteries, big solar panels and all of that sort of stuff. That’s an emerging technology, there is no real regulation in terms of safety around those things… Previously if you [this regulation] came through EU regulation then into our regulation… Now we’re not part of the EU, who is going to do that big regulation? I don’t see where that’s coming from at the moment

While it is possible for challenges – and opportunities – to emerge in almost any policy area, they can be expected primarily in areas which were previously the preserve of European-level policy-making but now fall to UK and devolved nation governments for the first time in decades. Immigration policy is a good example, with the end of free movement for European Union citizens requiring the UK government to create new pathways for people to enter the UK. In this and other areas like fishing and agriculture, international trade and the use of data and technology, public service leaders can expect challenges to arise – but there will also be opportunities for innovation.

Key challenges for public service leaders:

-

How large are the impacts of the UK exit agreement on different public service sectors?

-

Which policy areas will be most strongly affected by implementing the exit agreement?

-

How can public service leaders collaborate better with policymakers to prepare for emerging uncertainties and issues?

Long-term planning and preparedness

A key lesson from the pandemic is that long-term planning and preparedness is one element of a successful response to a disaster – the evidence review found that those public services with better-developed emergency response plans tended to be able to adapt these to meet the challenge from the pandemic, and EU exit no-deal plans were also considered to have been beneficial here. Although other factors like funding and existing workload are also important, analyses of public service performance tend to highlight the positive impact of having well-established protocols in place and this will likely grow in importance as the pandemic ends and policy-makers consider how to make public services more resilient.

Long term goals are also becoming important in other areas of policy, particularly around combating climate change. The UK Government has announced a series of long-term policy goals centred on reaching ‘net zero’ carbon emissions targets later this century and is chairing the COP26 summit in Glasgow later in 2021. These targets have longevity as they command strong, cross-party support, and they are also transformative as they will require change across policy areas.

Public service leader – Local Government:

The two trends our Mayor certainly talks about are… everywhere’s going to have to be a digital city region and everywhere is going to have to be a low-carbon city region… Low-carbon [is] an absolute, massive driver for our activity

The combination of these factors means that preparedness and long-term planning is likely to be an area of salience for the government and public. As a result, in the coming years public service leaders are likely to be required to implement and prepare longer term plans and are also more likely to also face greater scrutiny over the state of long-term planning in their organisations.

Key challenges for public service leaders:

-

How important is long-term planning and preparedness to the resilience of different public services? What other factors are important?

-

What challenges might longer-term carbon reduction goals present to public services?

Tensions in decentralised decision-making

Throughout the pandemic comparisons have been made of the relative performance of different UK regions and nations. The nature of the public health emergency has also highlighted links between local and central government – while public health is a local government responsibility, under the pandemic there has been much greater involvement from the Central Government, through imposing regional and national lockdown measures and establishing a Test and Trace system.

Public service leader – Emergency Services:

Big government, for me, is good in terms of putting in place a national vaccination programme, i.e. getting, buying the vaccines, all that sort of stuff. There’s no way locally you could do that. But actually, the administering, that should be more devolved

These tensions form part of a wider debate about the role and extent of decentralisation in policy and public services. The current government has shown an interest in further devolution of powers within England, recently announcing a new local government structure for North Yorkshire tied to a devolution deal that will give greater local decision-making power.[footnote 71] This could pose challenges for public service leaders; the scope of their role may change more in the coming few years than it has over the past decade and they will need to adapt to changing expectations and requirements.

Key questions to consider:

-

Which public services might see a greater level of decentralisation and which might see a greater level of central control?

-

How might greater decentralisation offer opportunities for innovation and service improvement in public services?

6.4 The role of collaboration

The evidence review highlighted some ways that collaboration can be useful in helping public service leaders deal with current issues relating to the changing role of the state and prepare for those that might arise in the future:

-

Collaboration of all types will play a key role in ensuring the smooth functioning of a decentralising Civil Service as relocations out of London continue. More importantly, if part of the intention of moving public sector workers into different communities is to provide a greater voice for these communities in policy development, there must be opportunities for non-professional and informal collaboration to allow local people to express their views. Further, horizontal collaboration between central and local government will be important to help workers relocate and formal collaboration may be required if locally-based workers from different sectors share workspaces.

-

Collaboration will also be a key element of long-term decision making. Setting out collaborative agreements in formal or contractual terms is one element which will help to give initiatives the longer-life required to have an impact over years or decades. The greater requirement of systems thinking (considering the impact of policies on all aspects of a location or society) will also place higher value on approaches which promote collaboration with other public service organisations and wider society.

Other important factors in this area focus around leadership, from politicians as well as public service leaders. Analysis of the success of previous efforts at moving public sector workers out of London highlights that the necessity of being located physically close to Ministers is a barrier; combatting this will require collaboration, with Ministers to showing support for relocation and senior officials providing a long-term plan for how staff will thrive in new office arrangements and be integrated into the wider department. Public service leaders will also need to demonstrate their support for relocations; an evidence review of the Office for National Statistics’ move to its Newport headquarters highlighted 90% of staff chose not to move at the time and the impact of this was being felt several years later.[footnote 72]

7. Theme 3: Rising complexity

Rising complexity in the provision of public services has been a key trend for some time but pre-existing issues around an ageing population, service integration, finance and funding have now been complicated by the long tail of COVID-19.

In addition to adding another layer of complexity for some individuals, the pandemic has put many day-to-day services on pause. Dealing with the backlog – for police and courts, schools and hospitals – will be a medium-term preoccupation and a political priority.

7.1 Background

Public service leader – Local Government:

If you said to somebody in the street ‘what does your local council do for you?’ the answer you’d probably get is they empty the bins or they tarmac the roads or whatever… People have quite a simplistic view of what many public sector organisations do and yet, the complexity of those organisations in and of themselves, the multi-agency working and the expectations on those are actually huge

Public service leaders interviewed for this research said that one way public services were seen to differ from other services people use is that they are required to be ‘always on’. Once a service is running the opportunity to stop it to make repairs, or redesign from the ground up, is more limited. They saw this as a one of the causes of rising complexity for three principal reasons:

-

Firstly, any service improvements or innovations must be ‘additive’ or bolted on to an existing service (rather than stopping a service to upgrade it fully), which results in greater complexity.

-

Secondly, it can raise the cost of innovation by requiring a period of ‘double running’, where a new service delivery approach must be trialled at the same time as continuing the original method at full capacity

-

Finally, in an era of increased collaboration and multi-agency working, the combination of previously separate services (each upgraded over time through additive improvements) can engender further complexity by blurring lines of control or accountability

Public service leader – Healthcare:

Yes, because it’s very hard for lots of public services to be switched off in order for you to do the work to transform them. The reason it’s hard to switch them off is that you haven’t got that much slack in the system to switch them off. What’s the best analogy, I suppose? The ability to decant out of one room while you’re decorating another, do you know what I mean?

Other complexities arise from long-running changes in the UK population. An ageing population can be seen as the result of a successful health care system and public policies, but it is projected to lead to big changes in the demographic structure of the UK that results requires adaptation and transformation of public services. For instance, Office for National Statistics (ONS) projections suggest that between 2016 and 2041 the number of single-person households will increase by a quarter – and by 2041 there will be more people aged over 65 living alone than those aged 16-64.[footnote 73] A surge in older people living alone will likely create demand for new products and services, such as new assistive technologies, new housing models and new retirement systems.

This will also pose new challenges for public service leaders – not only in providing services to an ageing population, but also in the management, training and retention of staff. In addition to longer-term considerations to prepare for an ageing workforce, there is a short-medium term challenge based on recent recruitment patterns. Research from the ONS suggests that after a period of lower levels of recruitment over the past decade (followed by an increase post-2016), public services may face a shortfall in leadership and institutional knowledge. Another factor to consider is that, as current leaders are approaching retirement, there is a smaller pool of potential replacements. This may be particularly acute in the local government sector where overall staffing numbers peaked in 2010 and have declined for the decade since.[footnote 74]

Funding pressures have also added to rising complexity as public service leaders have responded to the challenge of maintaining and improving service delivery within existing budgets, resources and workforces. Impacts vary across sectors:

-

Analysis by the Institute for Government shows that adult social care and prisons have seen the largest declines in performance relative to other public services and require additional funding.[footnote 75]

-

Further education has also been affected; in February 2020, the National Audit Office reported that 48% of colleges were in ‘early intervention’ or ‘formal intervention’ (stages of the audit process where college leaders are required to take steps to improve the financial health of their organisation) because of their financial health.[footnote 76]

-

Staff shortages have been a long-term challenge in nursing and disparities between services have been already widening. While the number of FTE nurses working in adult hospital nursing grew by 5.5% in the year to June 2020, the growth in mental health and community nursing was far smaller (3.85 and 1.6% respectively).[footnote 77]

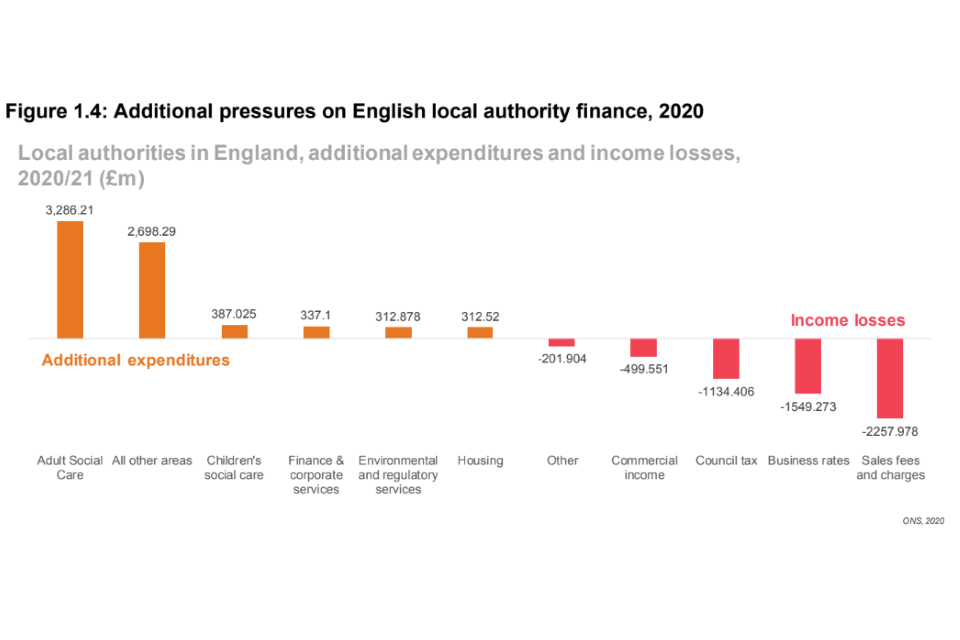

Reduced funding for local government has also had an impact.[footnote 78] Reductions in Central Government funding and pressure to restrict increases in Council Tax over the past decade are reported to have played a role in leading some local authorities into difficult financial positions – with Northamptonshire, Croydon and Slough the first councils for almost 20 years to issue Section 114 notices implementing emergency spending controls and concern in the sector that more will soon follow.[footnote 79]

The Institute for Government reports that the COVID-19 pandemic will exacerbate the issue of Local Authority funding further with councils projected to lose more than £6bn in expected revenue over 2020 and 2021 due to falls in Council Tax, business rates and other sources of income.[footnote 80]

Figure 1.4: Additional pressures on English local authority finance, 2020

Integrated services are seen as one way to make services more efficient to overcome some of the funding pressures being experienced,[footnote 81] yet this can require significant changes by service providers and leaders to change how their organisations work, breaking down silos to collaborate across organisations.

Public service leader – Emergency Services:

I sat on both calls from [County Council] and [Unitary Authority] as a partner, I would see the pressures in [one] and I’d see the pressures in [the other], and what was interesting is the health trusts never seem to have a conversation within those NHS boundaries

The NHS five-year forward view from 2014 aimed to establish integrated care systems (ICS) throughout England by 2021. A review by the Kings Fund found that while progress is being made, there are continuing tensions in the system between the NHS and the care system that pushes leaders into their own organisational silos.[footnote 82] For instance, while local leaders with direct involvement on ICS feel more positively towards collaboration, those with no direct involvement have expressed feeling excluded and that efforts for strengthening collaboration are not being made. Similarly, leaders from the NHS side have expressed that a greater level of engagement with local political leaders is hindered by “political machinations” happening in each local authority and that engagement with executive officers tends to be easier.[footnote 83] Despite these setbacks, local leaders recognise that progress towards integrating care better is being made.

7.2 Trends revealed and accelerated by the pandemic