Flexible working qualitative analysis

Published 28 March 2019

Flexible working qualitative analysis

Organisations’ experiences of flexible working arrangements

March 2019

Leonie Nicks, Hannah Burd and Jessica Barnes – The Behavioural Insights Team

1. Executive summary

Flexible working, defined by the UK government as “a way of working that suits an employee’s needs”, is critical for improving workplace gender equality. Women do the majority of unpaid care work in the UK and so the majority of flexible workers are women. While the impact of other flexible working arrangements is yet to be well understood, the negative impact of part-time working disproportionately affects women’s careers and contributes to the gender pay gap. The challenge of widening access to and successful implementation of flexible working arrangements for both men and women faces employers across many sectors. Yet it could be the key to women’s retention and progression at work and gender equality across society as a whole.

1.1 Study aim

The main aim of this study was to identify barriers and facilitators for organisations offering flexible working, and the main barriers and facilitators to employees taking up or accessing flexible working. We examined this from the perspective of Human Resources (HR) professionals.

Semi-structured in-depth interviews were carried out with 20 HR professionals. The organisations involved were of a range of sizes and sectors selected to achieve a likely diversity in flexible working availability and uptake.

1.2 HR perceptions of flexible working

HR professionals understood flexible working as flexibility in relation to when and where employees work their hours. Arrangements could involve either a formal change to the contract or an informal agreement between employee and line manager.

Most types of flexible working arrangement were made available to employees in principle. Uptake was fairly low for formal arrangements, but there was a sense that informal uptake was much higher.

1.3 Barriers and facilitators of flexible working

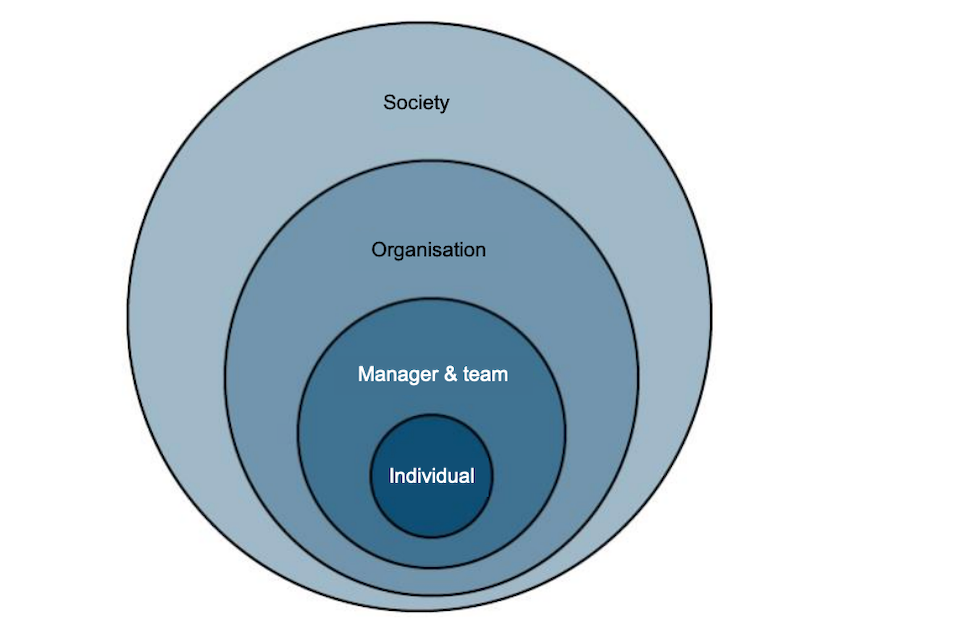

Four spheres of influence emerged from the data at the individual, manager and team, organisation and society levels. Each sphere of influence determined barriers and facilitators for both offering and taking up flexible working.

Table 1: Summary findings

Sphere of influence: Individual

Impact on flexible working:

-

Employees can shape the flexible working arrangements made available by their organisation by the demands they make

-

Their uptake of flexible working is influenced by how they perceive it fits with their identity and needs

Sphere of influence: Manager and team

Impact on flexible working:

-

Teams that individual employees work in can facilitate the successful uptake of flexible working

-

Managers play a critical role in the success of flexible working

Sphere of influence: Organisation

Impact on flexible working:

- Organisations control their flexible working offering and influence their employees’ uptake through the cultural norms of the organisation and its corporate policies

Sphere of influence: Society

Impact on flexible working:

- Society influences the uptake and offering of flexible working through societal norms and the availability of infrastructure to support flexible workers

1.4 Conclusions

The insights from this research enabled us to identify behavioural solutions to improve the uptake of flexible working across 3 areas. We have identified a need to:

-

Support individuals who make a flexible working request by simplifying and signposting the process for employees. This process needs to be made as easy and attractive as possible. Requests should be automatically monitored by HR to ensure none are privately rejected by line managers.

-

Support managers to implement flexible working by providing meaningful guidance or trial periods to help them to consider and envisage how to implement flexible working patterns in their team. Guidance could address how to scale workloads and objectives appropriately. Prompt open conversations about work- life balance and preferred working styles with employees, including at timely moments such as before and after parental leave.

-

Make flexible working the organisational norm by advertising all job roles as flexible, automatically carrying forward flexible working arrangements into promotional roles and accepting flexible working requests by default. Visibly role model flexible working throughout the organisation. Disrupt the normal ways of working by encouraging different working patterns. Discuss flexible working as part of the induction process to the organisation.

2. Introduction

2.1 Flexible working in the UK

There is growing recognition in the UK of the benefits of flexible working. As well as helping employees balance their professional and personal lives, flexible working can help businesses by increasing staff motivation and retention.[footnote 1] UK workers have the legal right to request flexible working arrangements from their employers. However, employers can still reject requests and employees do not always feel they can request flexible working.[footnote 2]

Flexible working is an enabler of workplace gender equality. As women do the majority of unpaid care in the UK[footnote 3], the majority of flexible workers are women and an absence of flexible working options can increase the chances that they will leave the workforce.[footnote 4] Flexible workers report feeling penalised for their working pattern with fewer development opportunities and promotions.[footnote 5] Further, if poorly managed, it can leave flexible workers overworked and responsible for disproportionately large workloads.[footnote 6] Part-time workers experience excessively slow rates of progression even accounting for reduced working hours.[footnote 7] Penalties attached to flexible working disproportionately affect women’s career progression opportunities and contribute to the gender pay gap.

The Government Equalities Office (GEO) have partnered with the Behavioural Insights Team (BIT) in a three-year collaboration to generate evidence on what works to improve gender equality in the workplace - the Gender and Behavioural Insights (GABI) programme. The current study provides greater insight into experiences of flexible working practices and will inform our wider work in the programme.

2.2 Study aims

The main aim of this study was to identify barriers and facilitators for organisations offering flexible working and the barriers and facilitators to employees working flexibly, from the perspective of HR professionals.

This study explored HR’s experiences and perceptions of the application of flexible working practices in their organisations to find out:

- What is understood by ‘flexible working’

- Which kinds are offered in their organisation

- The uptake of flexible working and by whom

- The barriers and facilitators for the organisation to offer flexible working

- The barriers and facilitators for employees to work flexibly

2.3 Methodology

Topic of research

This research on flexible working was conducted alongside a piece of research examining HR professionals’ perspectives on returners. These 2 topics overlap considerably, as people returning to the workforce after leave for caring responsibilities may have greater need for flexible working arrangements. However, returners are also a unique group of people in terms of their priorities and potential motivations for working. For this reason we split the 2 topics into 2 reports, but methodologies for both topics were the same as they were part of a single piece of research.

Semi-structured in-depth interviews

For this qualitative study, semi-structured in-depth interviews were carried out with 20 senior HR professionals working at UK organisations. Interviewees provided full informed consent to participate. The interviews were carried out by telephone between May and July 2018 and lasted between 45 minutes to 1 hour. The interviews were recorded digitally and the digital recordings transcribed in full.

In-depth interviews were chosen to achieve a deep insight into the perceptions and practices of HR professionals from a variety of organisations. We chose not to carry out focus groups as these are more exposed to social desirability or influence from dominant characters, and so would not achieve the richness of data we desired. Interviewees were asked questions about both flexible working and returners in the same interview.

Sampling

To gain a deep understanding of HR professionals’ perspectives on flexible working and how it works within their organisation, we sought to achieve range and diversity with our sample of interview participants.

We sought to interview participants from organisations of a range of sizes and industries. We originally planned to recruit organisations to achieve a range of flexible working practices. However, it was not possible to identify accurate indicators of flexible working that could be used during recruitment. There were no clear objective indicators and it was not until we had conducted the interviews that we could retrospectively make a judgement of an organisation’s flexibility. At this point, we found that the majority of interviewees were from organisations that might subjectively be judged to be quite flexible, with formal flexible working policies and active strategies to encourage flexible working. This is in line with increasing prevalence of the availability of flexible working in arrangements in UK organisations.[footnote 8]

Given the problems with identifying the flexibility of organisations prior to interview, and given the importance of obtaining perspectives from individuals in organisations less invested in flexible working, we adapted our sampling strategy. We continued to focus on obtaining diversity across industries, but targeting industries that were more traditionally male- or female-dominated. The rationale was that more male-dominated industries might subscribe to more traditional beliefs about working practices. This was not guaranteed, but we hoped that this proxy measure would achieve greater diversity in our sample in terms of the range of perspectives on flexible working practices.

The sampling was carried out in 2 waves. Initially we used a contact list of organisations held by GEO. To supplement this, we employed a recruitment agency to fill the gaps in our sample by providing hard-to-recruit interviewees from particular industries in order to obtain diversity in our sample. Agencies gave incentives to such interviewees ranging from £80 to £100.

Table 2: Size and sector of participating organisations

| Industry | Under 250 employees (small) | 250 to 3,999 employees (medium) | Over 4,000 employees (large) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Financial services | 1 | 1 | |

| Legal | 1 | 1 | |

| Professional services | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Technology and software | 2 | 2 | |

| Manufacturing | 1 | ||

| Construction | 1 | ||

| Hospitality | 1 | ||

| Public service | 1 | ||

| Charity | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 7 | 7 | 6 |

The full list of organisations and their industries, size, interviewee gender and gender pay gap is listed in Appendix A.

Analytical approach

Researchers conducted a thematic analysis of the data. The transcribed interview data were processed and sorted into themes using the computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software, Dedoose. The process of thematic analysis ensured all data were line by line coded, categorised and labelled to represent similarities and differences in all participants’ (HR professionals) experiences. Codes were initially identified and organised into groups, then revised, collapsed and refined until they formed the overarching themes represented in this report. This iterative approach ensured that themes that accurately represented all participants’ experiences emerged from the data. The range of perspectives and experiences were critically analysed, and notable connections within and between themes were identified. Verbatim quotations were extracted from interviews to illustrate or highlight particular conclusions.

Interpreting this research

There are 3 elements to keep in mind when interpreting the research findings presented in this report.

-

Focus on experiences: Qualitative research provides insight into the variety of experiences and views people have, rather than attempting to quantify them or measure the prevalence of them. The sampling approach ensured that a range of views on the application and uptake of flexible working in organisations was captured.

-

Narrow perspective: The interviewees were all senior HR professionals. They provided understanding from the perspective of those in organisations with a high level of power over the implementation and use of flexible working options.

However, the data cannot speak to other viewpoints towards flexible working, such as employees, managers or the wider public.

- Selection bias: The types of organisations that agreed to take part in this research may be different from those who were given the opportunity to take part but declined. Efforts were made to recruit difficult-to-reach participants through recruitment agencies, however, this does not entirely resolve the issue.

2.4 Report structure

The report is structured around the 4 main spheres of influence in facilitating or preventing offering and uptake of flexible working:

-

Individual employee level: the role that employees themselves play in their access to flexible working arrangements and their success.

-

Manager and team level: the role that the team and managers play in facilitating or hindering individual employees working flexibly.

-

Organisation level: the role that the organisation’s culture and its policies facilitate or hinder the flexible working offering and its uptake.

-

Society level: the role that societal norms and infrastructure play in facilitating or hindering flexible working.

These spheres of influence are nested. Individual employees are the core drivers of flexible working uptake and they are directly influenced by their manager and surrounding team. Managers and teams are constrained by the broader organisation, which is influenced by wider society.

The spheres interact with the others to facilitate or hinder flexible working, for example, society influences individual employee and manager beliefs, but also provides enabling or disabling infrastructure to organisations for flexible working.

Figure 1: Spheres of influence

3. What is flexible working?

When asked to explain what flexible working meant to them and their organisation, HR professionals broadly defined it in terms of time and location: when and where employees carry out their work hours. It can be either formal or informal, whereby formal usually results in a change to the employee’s official contract, and informal is an unwritten arrangement usually agreed between employee and manager. Full definitions for each of the flexible working terms are provided in the glossary.

HR professionals in the current sample identified a number of arrangements as ‘flexible working’. These included flexitime around core hours, part-time working, working from home, compressed hours, annualised hours, job shares and term-time working. Not everyone in the sample had come across each of the specific terms, but they were largely familiar with them once explained.

There was some lack of clarity over whose needs should be accommodated by flexible working arrangements. While the UK government’s definition clearly states that flexible working is “a way of working that suits an employee’s needs”,[footnote 9] there was an idea that shift work counted as flexible working as it could be performed at any time of day whether or not the employee had control over it. Another alternative viewpoint offered by HR directors was that flexible working is intended to help both the employee and the organisation.

“I think it’s starting to become a little bit of a confusing term because it can mean a number of things. I think the […] definition of flexible means - it can mean - the notion of ‘I can work when I want to’ … but the word ‘flexible’ means what are the defined specific hours and days that work both for the individual and for the organisation.” (Organisation 9, Hospitality)

Aside from these deviations from the UK government’s definition, most of the sample understood the broad concept of flexible working even if they did not currently have all the different forms in operation at their organisations.

The most common form of flexible working arrangement available was flexitime around core hours, with the least common job sharing. Uptake for formal flexible working arrangements such as part-time was fairly low with approximations ranging from 10% to 25% of employees. Meanwhile, they sensed that informal forms of flexible working had a much higher uptake, with estimates ranging from 30% to 100%. This aligns with the latest Workplace Employment Relations Study, which finds that flexitime and working from home are the most commonly used reported forms of flexible working arrangements.[footnote 10]

It is important to note that throughout the interviews, the HR professionals often talked about flexible working as a singular broad concept, rather than differentiating between different forms of flexible working. Different kinds of flexible working likely have different implications for workers and organisations. Specifically, arrangements that involve a contractual reduction in hours, such as part-time working or job shares, can result in overall income loss for employees. Further, more informal forms of flexible working are likely to have fewer implementation challenges for most employers. The focus of this report is to understand the HR professionals’ experiences with flexible working in their own terms. As such it does not seek to address the cost-benefit implications of different forms.

4. Individual

The first sphere of influence to explore is at the individual level. Barriers and facilitators exist for individual employees in both seeking flexible working arrangements from their organisations and successfully working flexibly on an ongoing basis.

The HR professionals felt that seeking and sustaining flexible working is partly driven by an individual’s motivations to work flexibly and their perceptions of the impact flexible working has on them and their career. These perceptions informed how much they felt employees saw flexible working as compatible with their personal and professional identities.

4.1 Summary of findings

Facilitators

-

HR considered offering flexible working an important way to attract and retain staff because of how much employees valued it

-

There was greater demand for formal flexible working among women with caring responsibilities in their organisations

Barriers

-

The association between formal flexible working and mothers contributed to the employee perception that working in flexible arrangements would limit career progression

-

Limited career progression was understood as a necessary sacrifice for the privilege of working flexibly

4.2 Employees value flexible working

HR professionals appreciated that employees like having flexible options available to them and thought it was an important thing for the organisation to offer. When they introduced flexible working, some employees became very excited about it.

“Within my first few months, the thing I introduced was flexible working … which we have now embraced and gone nuts with.” (Organisation 17, Conservation Charity)

There was strong consensus from HR professionals that employees sought flexible working arrangements to accommodate their caring responsibilities: primarily children, but also elderly parents. Childcare responsibilities mentioned included the school run, dealing with home emergencies, or transitioning back to work after parental leave. There were also lifestyle-related motivations, such as commute times, health and wellbeing, living permanently in a separate location to the office or approaching retirement.

One view was that flexible working was the primary feature that employees value and were willing to give a lot in return for it. An HR professional felt that employees were “so flipping grateful that somebody has given them a chance to work flexibly” (Organisation 2, Legal) that they were more motivated at work. It was felt that employees experienced guilt in taking up flexible working options. Even when employees did not take up a flexible working offer, knowing that it was available remained important for their sense of control.

“They still came in at 9 o’clock, still went home at 5 o’clock, but it was the thought that they didn’t have to, that it wasn’t mandated. That real life could happen alongside.” (Organisation 17, Conservation Charity)

4.3 Flexible working helps attract and retain employees

It was felt that flexible working arrangements played a critical role in retaining staff because they were so important to a significant portion of the workforce. HR directors reported it was a way of keeping brilliant employees from leaving the organisation and they “would rather offer someone flexibility than lose that experience” (Organisation 6, Professional Services). They also felt that offering flexible working helped retain staff, fostered loyalty and attachment to the organisation and improved staff wellbeing, which in turn made them more effective workers. This was also related to issues of gender equality.

“If you want to keep your workforce and you want to improve your gender pay gap and you want to keep more women in the organisation, […] organisations need to wake up to the fact that they need to give flexibility” (Organisation 6, Professional Services)

Organisations were starting to consider flexible working as a competitive advantage: a way of attracting new recruits to jobs which talented individuals might not otherwise consider. It was also used to compensate for other downsides such as an inconvenient location or lower pay relative to experience.

“I’m the only person that would consider [a particular employee] in that role 3 days a week. She left her last firm - they wanted her, they tried to keep her as HR Director - but it had to be 5 days a week. So I got her to do a slightly more junior role here for 3 days a week” (Organisation 2, Legal)

4.4 Demand for flexible working varies by gender and generation

The HR professionals reported that the majority of employees who asked for flexible working arrangements were women. Much of the time, women requested part-time work or another flexible working arrangement after returning from maternity leave and to accommodate caring responsibilities. Some HR professionals had not come across any men in their current organisation asking for formal flexible working arrangements to accommodate caring responsibilities. However, others had men working in part-time arrangements and some HR professionals felt that this number was increasing. Meanwhile more informal forms of flexible working, such as working from home, were generally taken up evenly between the genders.

While flexible working has been associated with mothers historically, there was a sense that the incoming younger generation of workers, millennials, expected flexible working, even if they were less likely to request it at their current stage of life. A generational difference emerged, with one HR professional describing some of their older employees as having a “legacy mindset” (Organisation 15, Social Care Charity). This mindset was described as coming from not having had access to flexible working in earlier decades of their career, so they felt everyone should work the same set way. It was felt that this may change over time, however, with the younger generation potentially having a greater impact on the acceptability of flexible working as they fill more senior positions.

“I think it would be unlikely that a law firm would allow a trainee to work flexibly for example […] or somebody who is quite junior […] I think most millennials are still in the middle to late 20s […] We might see a change coming soon now, as they get older and as the millennials start to become the partners - that will be interesting.” (Organisation 18, Legal)

However, it was noted that even millennials could be hesitant to request flexible working for fear of its impact on their career progression.

“I think there is a pressure on millennials around maybe not taking compressed hours and part-time because they just don’t think they are in the game.” (Organisation 15, Social Care Charity)

4.5 Concerns about progression act as a deterrent

HR professionals reported that concerns about the impact of working flexibly on career progression was a clear barrier for both male and female employees. They felt that in some cases, working flexibly negatively impacted performance and therefore progression. This was through missed opportunities for development or for stakeholder engagement, being left out of the loop, poorer client relationships, or not being able to get the job done in the time available. One HR professional felt that it would be difficult to promote someone working flexibly if the demands of the more senior role could not be met within flexible working patterns.

“I think if you only wanted to work 3 days a week for the rest of your career, then I’m not sure that you would progress to a level that you want to.” (Organisation 2, Legal)

However, it was also recognised that slower progression could be driven by attitudes about flexible workers, such as that they are less committed to the job, less visible, and are violating organisational social norms of working late, which deters employees from seeking flexible working. In some cases, it was felt that these concerns could impact upon home life, such as parents feeling guilty about taking time out of work for school events. Despite the view that employees might feel that flexible working limits their progression, there was also a contradictory view among the HR professionals at organisations with a prosocial or charitable purpose. In these organisations, HR professionals did not perceive flexible working to be a barrier to progression.

Financial cost was identified as a restrictive barrier, as many employees who might otherwise seek part-time arrangements could not afford to earn less given their current living costs. It was understood that this could particularly affect junior employees or those in low-paid roles. However, it was also cited as impacting the more financially well-off, in the case of employees in the finance industry losing out on substantial bonuses.

If the barriers to uptake of flexible working were removed, there are still some employees who would not like to work flexibly. As one HR professional recalled in her own experience, she worked part-time for a period after having her first child, but “I just missed being full-time, so it was my choice to come back full-time” (Organisation 10, Professional Services). Another HR professional reported that a lack of flexible working arrangements did not feature in the top 3 reasons to leave the company, according to their exit survey data.

Conclusion: Flexible working is seen as a privilege

The message that emerged from the HR professionals in our sample was that flexible working is a privilege. Since employees have to be granted access to flexible working and are not automatically entitled to it, they might feel they owe organisations loyalty and gratitude in return for flexible working arrangements and carry a sense of guilt about taking advantage of them. If they do work flexibly, they have to make sacrifices for doing so through slower progression, lower pay or downgraded job roles. Employee perceptions that working part-time means career sacrifice is fuelled by the stereotype that part-time workers are mothers. Yet, the finding that more informal forms of flexible working were taken up relatively evenly between the genders suggests that all employees would like to work more flexibly in principle. They are more hesitant if it affects their pay packet or identity.

5. Manager and team

The second sphere of influence to explore is at the manager and team level. How managers and teams affect an individual’s decision to work flexibly and how far they enable or constrain that choice are important questions. Regardless of an individual’s motivations for working flexibly, the way that team members work together can make it more or less difficult for any single individual to work flexibly. Strong managers can overcome wider barriers to flexible working through their capacity to coordinate and integrate team members and their collective workloads.

“I always encourage anybody who is looking to work flexibly to think from … 3 sides of a triangle – what do I want, what does my manager want, what’s good for the team.” (Organisation 4, Financial Services)

5.1 Summary of findings

Facilitators

-

Well functioning teams provided important support to individuals working flexibly

-

Managers were considered largely supportive of flexible working and played a critical role in facilitating successful flexible working through strong relationships with their employees and excellent people management skills

Barriers

-

The perceived negative impact on the team deterred employees from requesting to work flexibly

-

Some managers could be cynical of flexible working operating successfully if they had had poor or little experience with it

-

Managers were limited in how far they could facilitate flexible working if it was unsuitable for the team

5.2 Teams

When flexible working arrangements work well, HR professionals attributed it to well functioning teams. Characteristics of well functioning teams included that they are collaborative, made up of high performers, and empowered to define what they will deliver and how. A strong sense of teamwork was considered important, so that everyone supports each other to manage the workload, for example, by taking it in turns to take time off.

Equally, the team environment could become a barrier to flexible working if there was a feeling that working flexibly lets the team down. Strong team camaraderie was felt to hinder flexible working as interviewees felt employees perceived that it would negatively impact upon the team. These impacts included disrupting the team from working collaboratively if everyone was not available at the same time or adversely affecting those in greater need of support, such as junior employees. Some noted that compressed hours specifically were perceived as unfair when many employees work beyond their contracted hours as a norm. By way of explanation, an employee working compressed hours might work 9 hours instead of the standard 8 hours per day and so do ten days’ work in 9 days, allowing them a day off every fortnight. However, other people around them who have not established a flexible working arrangement might work 9 hours per day every day, an hour beyond their daily contractual obligations, and yet not have a day off.

One interviewee found in an employee survey that some respondents felt those working flexibly “are getting away with an easy life” (Organisation 2, Legal). Such negative perceptions might contribute to the peer pressure within teams to work full-time. This was reinforced by the observation that employees were generally supportive of flexible working as long as it did not burden colleagues.

“Yes, generally I would say they are [supportive of others working flexibly] as long as the individuals are seen to be carrying out their responsibilities, and some of those work commitments don’t fall to their colleagues.” (Organisation 13, Construction)

5.3 Managers

Line managers played a central role in supporting employees to work flexibly, and having an effective manager was not always a given, “it really is a line manager lottery” (Organisation 4, Financial Services). Line managers had a gatekeeping role as granting flexible working requests was usually within their discretion. HR professionals reported that they could work with line managers and employees to work out how to structure flexible working arrangements. However, some suspected they do not have complete visibility: they might never know how many formal requests are officially made because the line manager had already turned it down.

Managers mostly support flexible working, but some can be cynical

Many HR professionals felt that line managers were largely supportive of flexible working, but some felt that line managers could still feel cynical about whether it can work. A common example given was that some line managers thought that employees working from home were not really working. There was mention of some particular cases where managers had expressed strong negative views about flexible working. For example, partners at a law firm were annoyed when their juniors did not ask permission before working from home. In another instance, a manager made the following comment about employees seeking part-time arrangements after maternity leave: “well, if you want to give up your career that’s fine” (Organisation 3, Automotive Manufacturing). One HR professional felt that historically many line managers thought flexible working was only for women and were shocked when men asked for it, but that it was changing.

Experiences with flexible working can change managers’ minds

Several HR professionals remarked that managers were wary of flexible working until they saw it in practice, for example, by having a trial period. Similarly, if they had had a bad experience with flexible working they were more apprehensive about it. Exposure and attitudes may differ across sectors, as an HR professional from a charity felt that incoming managers from the private sector were less likely to be supportive of flexible working.

“Sometimes the manager would say ‘I just can’t see how it works’. Well that just doesn’t sound good enough to me. You can’t turn it down on that. Let’s do a trial period and let’s see if it works. Let’s ask the person to make it work, and more often than not all trial periods are agreed because they work. In the end it’s just perceptions rather than actual evidence that tells you these things don’t work” (Organisation 17, Conservation Charity)

Strong manager-employee relationships facilitate flexible working

HR professionals highlighted the importance of a good relationship between a line manager and their employee for making flexible working successful. It was noted that managers took a more positive view of flexible working when they had a strong working relationship with their employee.

Trust was identified as a core component of this relationship as it enables employees to work independently of their manager, and gives them the confidence to manage their workloads in a way that suits them. Some interviewees felt that employees should be trusted to deliver their objectives and therefore be treated “as adults” (Organisation 2, Legal). Conversely, a breakdown of trust could lead to a failure of flexible working arrangements.

Strong relationships built on trust are a two-way exchange between employee and manager. One HR professional pointed out that employees needed to be physically present during working hours to build a relationship of trust required for flexible working. Similarly, interviewees felt that a manager might refuse a request if they thought the employee does not have a good work ethic or prioritisation skills, or the quality of their work would be negatively impacted. However, it was felt that if the right person had been recruited into the role, then they should be trusted to work flexibly. If there was a lack of trust that an employee would deliver, this should be seen as “a performance management issue and not a flexible working issue” (Organisation 4, Financial Services).

“…if you have the right person in a role, then it doesn’t matter where they are. So again it’s making sure that you are hiring really talented individuals to do the job, who take I suppose some sense of pride in the job that they deliver. Because then it doesn’t matter where you are and you can deliver a good job” (Organisation 4, Financial Services)

Strong people management skills facilitate flexible working

HR professionals explained that flexible working is best facilitated when managers have strong people management skills and focus on output rather than hours. An issue identified here was that managers may have been promoted in recognition of their technical skills, which may not correspond to their people management skills.

“The things that I think you need to have in place to have successful flexible working are good people managers. People managers who manage by output rather than input, and don’t judge an individual based on how long they see them sitting at their desk but judge them based on whether the work gets delivered.” (Organisation 2, Legal)

Communication between managers and teams was important for the success of flexible working arrangements, and individuals could facilitate this by having conversations with their line managers as early as possible when considering making a flexible working request. Another issue was that managers might lack confidence and worry about their ability to handle conversations about flexible working arrangements. In particular, one HR professional cited that some men could be unsure how to handle maternity leave conversations and were afraid of saying “the wrong thing” (Organisation 7, Financial Services). At this organisation, the HR professional worked with male managers to have better conversations, which made them more aware of the challenges of balancing childcare with work.

Some teams are limited in how far they can work flexibly

It was understood that some line managers perceived particular teams to be less suited for flexible working than others. They might be generally supportive of flexible working but believe it is not universally feasible for all employees or teams. Some felt that the makeup of the team might impact upon the feasibility of flexible working, for example, one HR professional felt that managing large teams of part-time workers was more difficult than teams made up only of full-time workers.

Conclusion: Strong managers are critical for empowering teams to work flexibly

There is an inevitable tension between the needs of the individual, their team and their manager, which if unresolved prevents working flexibly. Strong teams can facilitate flexible working by supporting each other and working to accommodate it. Strong managers trust their employees and ensure that workload is balanced across the team. When managers build strong relationships with and between team members this improves communication, which helps identify the team’s needs and empowers individuals to take more independent control over their work. However, the extent to which managers are able to do this successfully depends both on the support they receive from the organisation to develop their people management skills and the infrastructure available to manage resources more effectively. Organisational culture and policies are big factors in the successful implementation of flexible working.

6. Organisation

The next sphere of influence to explore is at the organisational level. Organisations play a critical role in facilitating the successful operation of flexible working across the business. Any one individual or team seeking to work more flexibly will be facilitated or inhibited by the policies, processes and resources put in place at the organisational level. Senior leaders play an important role in setting the strategic priorities and cultural tone for the rest of the organisation. If flexible working is valued in an organisation, structural accommodations will have been made and employees will feel it to be part of their working culture. Cultural norms, infrastructure, policies and processes interact with each other in order to facilitate or hinder flexible working.

6.1 Summary of findings – culture

Facilitators

- A culture of flexible working could be created through the strategic priorities that leadership set for flexible working, role modelling flexible working organisation-wide, and by taking steps to make flexible working patterns the default norm over traditional working patterns

Barriers

-

HR had different views about whether flexible working should be considered as a policy for all or only those with caring responsibilities

-

Creating a culture of flexible working was limited by resistant employee attitudes to deviating from traditional working patterns

6.2 Culture

Organisational behaviour and culture tends to be set by the top. Senior leadership support can enable flexible working practices to have traction throughout an organisation. HR professionals felt that their senior leadership was supportive of flexible working. This was sometimes driven by the leadership’s use of it themselves.

“There has always been a strong ethos on being flexible and […] encouraging flexible working in the organisation, and I think partly that is because our last 3 Director Generals have all been female. This is my hypothesis, and all have raised children whilst working for [the organisation]” (Organisation 12, Conservation Charity)

However, endorsement of flexible working by members of the senior leadership team was not always enough to convince employees further down in an organisation. HR professionals reported that senior management were sometimes more supportive of flexible working than middle management, who they felt were possibly unsure of how to manage flexible working on the ground.

Organisational leadership set strategic priorities that inform culture

Leadership within HR was important too, as one interviewee explained, “I think with the culture, if it comes from the top and your HR support it then that is half the battle” (Organisation 19, Technology). Some felt that HR played an important role in persuading senior management and had done so themselves. Some interviewees achieved this by making the value proposition in terms of its benefits and productivity gains clear. Many HR professionals expressed a strong interest in making their organisations more flexible and enabling individuals to take up flexible working arrangements where possible.

“…there was no flexible working mentioned when I joined … and [I] thought I have to change this for the organisation. When I finally convinced the senior team that this is what we needed to do and actually it wouldn’t just be anarchy and people wouldn’t just be floating in and out when they felt like it and you’d never know what was going on, that people would settle down into patterns.” (Organisation 17, Conservation Charity)

Support for flexible working from leadership was important as it let “employees know that they can go to management and be given a fair chance” (Organisation 18, Legal).

Leadership set strategic priorities, which inform the organisation’s culture. For an HR professional from a charity, flexible working strongly aligned with the organisation’s broader mission of long-term sustainability. Another HR professional explained how flexible working had become a priority through the organisation’s wider strategy to attract and retain more women in the organisation.

Conversely, lack of support from leadership represented a barrier for flexible working. HR professionals in the legal industry felt that ‘old-fashioned’ views among partners about the incompatibility of flexible working and progression was a real barrier for junior lawyers wanting to have both. In another case, leadership at a charity limited the extent to which the HR director could expand their flexible working policy as they vetoed having fully flexible hours without a core hours policy. Nonetheless, the more common view was that leaders were rejecting the long hours culture, more interested in taking an outcomes- focused approach in measuring employee contribution and evolving towards greater acceptance of flexible working patterns.

Role modelling is important for groups that have traditionally not worked flexibly

Senior leaders were described as having an influence on organisational culture through role modelling behaviour for the rest of the organisation. HR professionals in some organisations explained that they felt their senior leadership team role modelled flexible working and saw this as an indicator that flexible working was not a problem for progression. There was an example of a male managing director in a company who was a vocal advocate of working from home as he did so every Friday. In other organisations, HR directors felt that part-time working was rare among their senior leadership. Occasional problematic exceptions to working flexibly around typical hours stood out as a result. The following example details a ‘successful flexible worker’ who seems to be working well beyond their contracted hours, even if flexibly.

“…we have got a female partner, who has not been with the firm very long, but I’ve already heard all sorts of amazing - in inverted commas - stories about her. She’s a single mum, she leaves at 4:30 to sort her daughter out who is 3. But then she logs on at 8 o’clock once her daughter is in bed and works until midnight every night. She is a very successful flexible worker and a sort of poster girl for all of that, but she works really hard.” (Organisation 2, Legal)

There was a view that working from home was potentially seen as a privilege that applied more to senior staff. HR professionals felt that senior staff working flexibly did not always communicate that everyone else could, and role modelling by middle management would have a greater effect. It might be that senior leadership role modelling can send a positive message about flexible working and career ambition, but only where it is not perceived as an exclusive privilege. Some organisations were therefore finding ways to publicise role models throughout the company, by sharing employees’ stories of their experiences and managers’ stories of how they had supported it.

As well as being seen as a privilege for senior leaders, many HR professionals felt that there was a common misconception that flexible working was just for women. The association between flexible working and women is potentially damaging in the sense that there are often only exceptional instances of women working flexibly and progressing. This was reflected by the singular examples HR professionals could recall of the occasional woman progressing in their organisations while in flexible working arrangements. To challenge this, HR professionals felt that male role models could be a useful tool for changing this view among employees. A number of examples were given of how this was done in practice, such as senior men speaking openly about their flexible working arrangement or men sharing their stories for International Men’s Day and International Father’s Day with their gender diversity networks. Other practical examples included raising awareness about flexible working through events run by the organisation’s women’s network, which men could attend although it was mentioned that few did.

Flexible working is perceived as only for mothers

HR professionals felt there was a problematic association between flexible working and mothers which meant that flexible working needed to be reframed. In some cases, organisations had renamed it ‘intelligent working’ or ‘agile working’ as a way of removing this association. Other HR professionals reinforced the idea that flexible working should be seen as something for all employees not just parents. Similarly, some felt that facilitating flexible working was part of creating an inclusive culture for everyone.

However, the idea that flexible working should only be for carers still influenced how some HR professionals executed their policies. For example, one HR professional reviewed part-time arrangements to see if employees still had caring responsibilities and took steps to significantly reduce the number of part-time contracts as a result.

“We’ve got examples where flexible working has been put in place for somebody for childcare arrangements, and on review their children are 21 and 23… So there are cases that just illustrate the point that the need for regular review is, I think, slipped a little bit.” (Organisation 5, Public Service)

Making flexible working the default assimilates it into the culture

To foster a culture of flexible working, multiple HR professionals talked about the importance of accepting flexible working requests by default unless there was a substantial reason not to. Some HR professionals felt that meeting the basic legal requirement of stating that everyone is entitled to ask for flexible working was sufficient, but making flexible requests accepted by default sends the message that they are the norm. To create this culture, some HR professionals in our sample made their informal flexible working entitlement automatic, put the onus on the decision-maker to provide a clear and compelling reason for declining a formal flexible working request to HR, or asked leaders why they cannot support the request. While some HR professionals could not currently make accepting flexible working requests the default, they wanted to shift the mindset within their organisation. A further suggestion was that all flexible working arrangements from an individual’s previous job at the current or former organisation could be automatically transferred to their current job.

There was a question about the role of formal policy in fostering a culture of flexible working. One view was that having formal policies took away from casual and dynamic forms of flexible working.

“…we just want it to be part of the way we work culturally … once you make something a policy it becomes like a right and nobody understands where the grey is” (Organisation 7, Financial Services)

Another view was that an organisation’s current formal policy made it difficult to change hours, but that it was the only practical option in a large organisation. At the other end of the spectrum, an organisation with no formal flexible working policies believed that it received few requests for flexible working because it was so flexible. On the one hand, organisations with good flexible working cultures might not feel they require formal policy if it’s “part and parcel of the business” (Organisation 11, Professional Services). On the other hand, most organisations had a formal policy where the decision lay with the line manager. Involving HR was one suggested way to ensure employees weren’t vulnerable to the preferences of their line managers, so could take their request to HR if the line manager was not supportive of it.

Organisational culture can be resistant to flexible working

HR professionals talked about organisational culture as a barrier to flexible working practices: the belief that employees were only working if they were visibly at their desk, had to be in the office to carry out their work, or the judgement of those who leave the office early. Other barriers were the belief that flexible working was equated to “skiving” (Organisation 1, Computer Technology) or a resistance to moving meetings to suit those working flexibly. If flexible working was taken up inconsistently across an organisation some HR professionals felt this created discrepancies in ways of working between different areas and meant that not all employees understood how it could work.

“When very few people work flexibly, it’s very hard for those who need to work flexibly to be understood, if you know what I mean. So I think that then there is an expectation that meetings can happen at X time, or - it’s a mindset thing of actually people feeling that if they’re not in the office then there’s no way that they can be productive. Or, why should we work around these people’s requirements when I want to do something at 9 in the morning, not wait until 11 until somebody is in or whatever it might be.” (Organisation 16, Marketing Software)

Conclusion: Successful flexible working requires a culture that enables it

It was acknowledged that shifts in culture take time and their intangible nature make it difficult for organisations to pinpoint how to change them. Leadership have the influence and power to create waves of top-down behaviour change that influence the culture of an organisation. They are the image of success and so when they role model flexible working practices this sends a strong message to all employees. This is especially important for groups that have not traditionally worked flexibly, particularly men.

Leadership have the power to set the strategic priorities for the organisation if they consider flexible working to be valuable. These priorities inform all layers of management of what the organisation considers to be important and enable HR to shape policy and processes. Well designed policies and processes enable managers and employees to overcome hurdles to working flexibly, facilitating more employees to work flexibly and ultimately contributing further towards a culture of flexible working.

6.3 Summary of findings – corporate policies

Facilitators

-

HR prioritised widening access to flexible working to differing degrees through the processes and policies they put in place – this was reflected by how accessible it was to request flexible working and whether job roles were advertised as flexible

-

Technology was considered an important enabler of flexible working, particularly for more informal forms of flexible working such as working from home

Barriers

-

Resourcing strategy was a challenge for flexible working, particularly in small teams and for certain kinds of time-based flexible working arrangements

-

Roles that required covering wide ranges of time, providing consistent service or being in a specific location were considered less compatible with flexible working

-

Different views about whether senior or junior roles were more compatible with flexible working could be explained by tension between greater role autonomy and fewer responsibilities facilitating flexible working

6.4 Corporate policies

The cultural environment of an organisation can reinforce and create the conditions for organisational change in terms of policies, processes and allocation of resources to enable flexible working to operate successfully on a daily basis throughout the organisation.

HR prioritise widening access to flexible working

Most of the HR professionals felt positively about flexible working, with some working in part-time arrangements themselves or managing a team with flexible workers.

Widening access to flexible working was a priority for some HR professionals. For example, one HR director set up a policy upon joining the organisation, as previously flexible working arrangements had only been available to mothers returning from maternity leave. This HR director consequently ensured that flexible working was discussed with new employees at induction. Other organisations made it as easy as possible to change hours, they provided managers with examples of how different flexible working arrangements could work, and when new managers joined the organisation the HR director made sure to tackle any preconceived notions if they did not fit with the organisation’s views on flexible working.

“Occasionally we have managers who have joined [the organisation] that may be from the private sector, that might come in with a different perception, but we really try to tackle those quite quickly.” (Organisation 12, Conservation Charity)

HR can facilitate flexible working through the design of the request process

There was variation in the processes for making flexible working requests. In some cases, this process involved filling out a form with details about the arrangement required, a justification for why it was necessary and a business case rationale for it. Another arrangement asked employees to make their request through an online portal. Where organisations had a formal flexible working policy, it was sometimes used to provide employees with guidance on completing the flexible working application process. Organisations took different practical approaches to sharing these policies, for example via their intranet, in their handbook or directly upon staff joining. It was acknowledged that sometimes HR professionals could probably do more within their organisation to promote their flexible working policy. Meanwhile, informal flexible working policies did not seem to be written down or shared, but were considered well established at some organisations.

HR functions sometimes had the opportunity to influence flexible working arrangements through the request process. Flexible working requests went through HR if they required a formal change to the contract, but the decision ultimately sat with the line manager. Line managers were encouraged to think about how the request would impact the team, the business and the employee. In one organisation, if a decision was reached internally, even for formal arrangements, there was no need to involve HR. As discussed previously, HR professionals felt they were unaware of the actual number of requests made as some would be rejected by line managers before they get to their department. At another organisation HR were able to monitor requests as they were registered in an online portal, while a separate ‘performance manager’ with no line management responsibility, approved flexible working requests with HR or line manager involvement if necessary. In some cases, HR and the line manager made the decision together.

Meanwhile, more informal forms of flexible working such as working from home tended to be a conversation between the employee and their line manager.

“…it feels as though when an individual applies, they apply knowing that their application will be approved because they have already had the conversation with their manager. And there’s a part of me that thinks that maybe that’s an area that we need to unearth a little bit more because it could be that conversations are happening, and the individuals getting to that stage where the manager will just say no […] so they wouldn’t apply.” (Organisation 3, Automotive Manufacturing)

The frequency with which an employee could make a flexible working request varied across organisations. For example, the most restrictive only allowed a request to be lodged once per 12-month period and the employee must have been with that organisation for at least 6 months to be eligible and serve a two-month notice period before any further changes. Others were open to discussing flexible working changes more often or at any time, for example, one HR professional reported that they bent the rules by relaxing their 12-month review cycle. Overall, HR professionals felt that the majority of the formal flexible working requests they saw were approved, although occasionally in negotiated form.

HR can be limited in how far they can make change

There are limitations to how far an HR function in an organisation can drive change. Some HR professionals talked about the challenge of setting unfair precedents in one geographical region or department that could not be upheld elsewhere. Others cited an impending organisational restructure had hindered their ability to progress flexible working practices. Often flexible working decisions fell to operational HR staff, but one interviewee considered strategic HR staff to be better placed for driving such change.

Although the majority of HR professionals were supportive of flexible working practices, a minority voiced opposing views. For example, one felt that employees saw flexible working as suiting themselves and their “social situation” (Organisation 9, Hospitality) rather than thinking about the impact on the business. There was also a view that flexible working had “swung too far” (Organisation 5, Public Service) and that there were too many people working in flexible working arrangements creating a strain on the business.

HR are hesitant to advertise all job roles as flexible

A way of signalling that flexible working is the norm at an organisation could be through stating that roles are flexible in job adverts. Several organisations stated in their job adverts that flexible working was possible. Some more were planning to start doing so. At one organisation they advertised flexible working “subtly” (Organisation 15, Social Care Charity) to manage expectations. Other organisations only stated flexible working was possible with certain roles in their job adverts. Most were hesitant to advertise all jobs as flexible in all forms of flexibility due to resourcing and role constraints.

Other organisations exclusively advertised job roles as full-time. One company felt they had reached the limit of the number of part-time workers they could accommodate, whilst others only advertised roles as full-time to grow their business or fill as many hours as possible. One commented that when they advertised jobs as part-time, it was harder to attract ‘good people’ so they no longer do so. However, they would consider a part- time arrangement if it was raised during the recruitment process. Others echoed that they would discuss flexible working arrangements during the recruitment process, but not advertise the role as flexible.

Technology is an enabler of flexible working

For many, technology had been an important enabler of flexible working, particularly working remotely or from home. For some, this was driven bottom-up by the need to coordinate a global workforce or a workforce operating across multiple client or office locations. For others, the introduction of technology had contributed towards a culture of working from home as employees had started to explore how to balance work with household commitments. One HR professional felt it helped to alleviate parents’ guilt about leaving work to handle home emergencies. Others used software tools to manage flexible working, such as viewing each other’s online calendars for working hours or to see who is working from home.

“With the roll-out of this technology, what it’s enabled us to do … it’s allowing us to change the culture and the way we work. So agile working is about having the choice about where and when you work, providing flexibility to employees and the organisation, it encourages collaboration. We think it can actually help everybody in balancing work and demands from other areas of life as well. That’s something that’s for men and for women and people at all levels of the organisation.” (Organisation 7, Financial Services)

Where technology can act as an enabler, the lack of or poor use of technology can act as a barrier. At one organisation, the HR professional felt that employees “are not good at dialling people in” for meetings (Organisation 10, Professional Services), which could exclude anyone working from home. Another HR professional felt that stakeholder engagement was still best managed through face-to-face communication within traditional organisations in the public sector, despite the potential for technology to manage that. One HR professional felt that technology could be put to better use in facilitating other aspects of flexible working, such as ensuring all flexible working requests are automatically brought to HR’s attention.

Designing a strong resourcing strategy is critical to flexible working success

A major problem identified by all those interviewed was how best to allocate resources to ensure sufficient coverage and quality service. Naturally for HR, resourcing strategy was raised multiple times as critical to making flexible working a success. Technology might provide solutions to this barrier, “the challenge with flexible working is not the concept, but what does the resource strategy look like … we have got to use technology better” (Organisation 15, Social Care Charity).

Lack of resources and the cost of having to hire additional staff was cited by many as a reason they would reject flexible working requests. This especially applied where someone in the team always needed to be present, whether to cover adequate business hours for the client or international work. On top of hiring additional staff, others felt there were additional costs from management time spent arranging work among staff and the poorer employee performance in meeting customer demands. However, these challenges may be exaggerated as one interviewee explained, “there is an element of misunderstanding about headcount, cost and productivity, which is untrue but people would say that it’s a barrier” (Organisation 1, Computer Technology). This was echoed by the following individual.

“… two 50% people cost the same in terms of salary and on-cost as one single person. We might need extra IT kits for the extra person […] so there is a direct cost there but it’s not a lot and not a good reason to turn it down. Certainly legally it’s not a good reason to turn it down and a tribunal would laugh at you” (Organisation 17, Conservation Charity)

Nonetheless, the challenge of managing resources effectively within teams and across the wider organisation cannot be underestimated. Even in one organisation where flexible working had historically been considered “part of the DNA” (Organisation 5, Public Service), managers could find it difficult when the “demand and supply equation is out of balance” (Organisation 5, Public Service). Interviewees felt managers found it difficult to scale the workload to become a part-time role if it had historically been full- time. They also felt managers would face continuity challenges if a team had lots of part- time workers and individuals were sick or went on leave. One organisation feared that outsourcing to address their resource gaps might negatively impact brand reputation.

The size of the team and the organisation may affect the ability to manage resources. Some talked about difficulties of enabling flexible working in smaller teams. For example, a receptionist at one organisation was refused a flexible working request as there were only 2 of them. Elsewhere, one HR professional suggested managers with larger teams might have to be less flexible in terms of location and hours to ensure proper management. This problem extended to smaller or medium-sized organisations, where some felt it might be more difficult to manage coverage of working hours. However, one small technology company felt that their need to “move fast” meant they could not be tied to a specific location (Organisation 19, Technology). There were opposing views regarding growing companies. In one comment, growing rapidly meant the organisation needed as many full-time employees as possible, whereas another felt their rapid growth enabled flexible working patterns. However, the latter was cognisant that they would need to ensure this was sustainable in the longer term.

“If somebody wants to come back and work part-time or wants to reduce hours, does that mean we are going to have to hire somebody else? … is the other consideration. But most of the time it’s not that much of a trade-off I don’t think, we can normally make it work - because we are a growing business as well, so there’s lots of different options and so we can move things around to try and accommodate those requests.” (Organisation 16, Marketing Software)

Some types of flexible working pose greater challenges to resourcing

There were 3 main types of flexible working arrangement outside of part-time working that presented particular challenges for resourcing: annualised hours, compressed hours and job shares. While many of the organisations had employees working on annualised contracts others felt that it created an administrative burden for employees having to fill in timesheets. For this reason they felt regular part-time contracts were a better option. The one scenario that seemed well suited to annualised hours was seasonal work which has clear peaks and troughs in the year.

Many of the organisations had employees working on compressed hours contracts, but some of them did not feel positively about it as they found employees could end up staying in the office to fill the hours even if they did not need to be there. As previously discussed, others felt that they were unfair on other employees regularly working overtime. Others had decided against offering it to their employees.

Job shares can resolve many of the resourcing problems with flexible working, but to set them up well takes careful consideration and effort. Many of the organisations had employees working in job shares. However, job shares were rare or nonexistent at other organisations. The reasons given for this were that the job was difficult to split, job share partners were difficult to find or the requested split was not feasible, for example, sharing 35 hours between 30 hours and 5 hours. One interviewee considered job shares to be a luxury, particularly at the senior level, as it requires individuals to overlap by at least one day to be effective. It was recognised that job share matching takes more effort and so ends up getting disregarded.

“Often things like the job share, where it takes a little bit more sort[ing] around who do you match together, often are the ones that get neglected, even though they sometimes they are the most effective.” (Organisation 4, Financial Services)

It is possible to overcome resourcing constraints

Nonetheless, some of the interviewees provided insights into successful ways of managing resources. At one organisation there was a specific body whose role was to oversee the flexible working practices across a business area and ensure that requests coming from individual teams fit with the broader operation. At another company that operated with multiple sites for tourists across the country, each site had autonomy over how they set up their working patterns based on when they are busy during the year.

Within another, employees were expected to follow certain principles such as arranging “suitable childcare” (Organisation 2, Legal) and ensure they complete their workloads in order to manage the resourcing implications. If resourcing is managed well it could greatly reduce attrition, as discovered by one organisation where they had enabled employees to have greater control over their shifts while still ensuring business hours are covered.

Some roles are less compatible with flexible working

Almost all interviewees talked about how different roles might constrain or facilitate flexible working. The resourcing model is more constrained for many kinds of roles, in particular, those that need to provide cover for wide ranges of time if not 24/7. These included software support teams, customer service, business support functions or rare expertise. It might be that the role required working at odd hours such as software engineers working at night when the software is not in use or one example of a press officer working weekends so that journalists could get in touch where a relevant news story might be developing. An HR professional from a hospitality organisation, where covering wide ranges of time is common, spoke about being very upfront with employees about the requirements of the role at the beginning. By paying employees by the hour, they could better adapt their workforce to meet fluctuating customer demand throughout long shifts in restaurants and hotels.

Some roles need to provide consistent service throughout the working week, such as client-facing roles or senior roles to maintain relationships. Providing consistent service to clients may be one of the reasons that many felt that senior roles are perceived to be less compatible with part-time working. Indeed, there was the view that in order to progress in law firms, employees needed to spend time building their client base, which made the workload too high for a part-time arrangement especially for junior employees. One HR professional felt flexible working arrangements are better suited to business support roles since they cannot progress in law firms. Multiple HR professionals echoed this theme, for example, one HR professional gave an employee a different role within the organisation to enable them to work part-time.

“It’s not so much in the business support side of things, because often people doing those jobs are doing them as a job rather than as a career. So, a legal secretary might

say ‘can I do 4 days instead of 3?’ and she doesn’t want to do anything else. Effectively there is nowhere else for her to go within a law firm if you become a legal secretary, so what else can you do? So it’s not a concern for people like that.” (Organisation 18, Legal)

More predictable environments can make it easier to implement flexible working. Some of the interviewees talked about the corporate environment of the head office as more amenable to flexible working through its predictability. However, there was some inconsistency as to whether corporate roles were thought to be more compatible with flexible working. In particular, roles were considered less compatible if they required coverage over a wide range of time in a small team, being in the office, or the client expected access to the employee at all times. The latter included admin support, secretaries, post workers or receptionists. Another HR professional felt that the relatively static office environment made it more difficult to disrupt 9am to 5pm routines.

The relationship between seniority and flexible working is unclear

There were differing opinions as to whether middle or senior management were better suited to part-time working. Some felt it was easier to see how part-time would work for middle management and that there were few senior managers working part-time in their organisation. However, some saw the opposite in their organisation. For example, one HR professional felt that once you are an established lawyer it was much easier to work flexibly than it was at the beginning of your career.

There seems to be a tension between the level of responsibility and autonomy an individual worker had and how compatible their role is with flexible working. Greater autonomy empowered individuals to have greater control over their work, including flexible working arrangements, where greater responsibilities made working flexibly more challenging. This might explain the inconsistencies emerging in the compatibility of flexible working with both senior positions and junior positions. Senior positions have high autonomy but also high levels of responsibility, whereas junior staff have fewer responsibilities but also lower autonomy. Senior management may be in a position to control how they work, but their commitments to the organisation, team and client mean they may need to need to work certain hours and attend important face-to-face meetings. Meanwhile, junior employees are often not in a position to control how they work even if they have less accountability.

Conclusion: Corporate policies play an important role in embedding flexible working

Corporate policies and processes have the potential to alleviate many of the challenges that individual employees and managers might face when confronted with resourcing and role constraints. Technology has revolutionised how organisations operate and made

flexible working achievable across the globe, but organisations can work harder to ensure they have the best facilities available to their employees and that its use is normalised.

Conclusion: A culture of flexible working ensures corporate policies are implemented

Corporate policies enable a culture of flexible working to flourish and a culture of flexible working creates the demand for better organisational structure. Policies and processes alone are ineffective if nobody makes use of them or members throughout the organisation are unaware they exist. They require a culture of flexible working that is inclusive and gender neutral to facilitate both wider uptake and reduce the negative consequences for flexible workers. If individuals are supported by the organisation this can provide them with further options if their line manager becomes obstructive. Similarly, the organisation’s structure can help managers to better manage their team’s resources and facilitate the trust required to make flexible working a success. However, organisations are limited by the societies they operate in. The values society places on working and caring inform cultural norms of behaviour, how funding is allocated and which facilities are available to citizens.

7. Society

The next sphere of influence to explore is at the societal level. Wider society can influence the successful spread of flexible working practices by setting ‘normal’ ways of behaving both in general and within groups, particularly for gender. Such norms are driven by the economic value society places on paid labour over unpaid care work. Employees and organisations respond to the demands put on them by their sector and clients as well as externally-driven factors. Thus, while societal norms might interact with the other spheres of influence in a more indirect capacity, its cumulative power over behaviour cannot be underestimated.

7.1 Summary of findings

Facilitators

- While the gender norm that flexible working is for women was still seen as prevalent, there was a sense it was changing as more men become active parents and more women want to develop their careers

Barriers

-

The societal norm that working flexibly limits progression and the gender norm that flexible working is for mothers deterred men from working flexibly and contributed to the ongoing disproportionate uptake by women

-