Evaluating the Support for Migrant Victims (SMV) Pilot: Findings from a process evaluation

Published 4 August 2023

Applies to England and Wales

Key terms and abbreviations

Acronyms

BIT: Behavioural Insights Team

DDVC: Destitution Domestic Violence Concession

DVILR: Domestic violence route to indefinite leave to remain

EEA: European Economic Area

ILR: Indefinite Leave to Remain

MV: Migrant Victim

NRPF: No Recourse to Public Funds

SMV: Support for Migrant Victims

Helpful terms

DDVC / DVILR: Destitution Domestic Violence Concession (DDVC) allows people who may be eligible to apply for ILR under the Domestic Violence Rule to access public funds whilst they make their application, if they can meet the basic initial test for domestic violence and destitution.

Section 17 : When Section 17 is referred to in this report, it relates to Section 17 of the Children’s Act 1989. This act places a general duty on all local authorities to ‘safeguard and promote the welfare of children within their area who are in need.

Core delivery partners

Southall Black Sisters[footnote 1] (London & South-East)

Founded in 1979 Southall Black Sisters is a non-profit London-based organisation which aims to challenge gender-based violence against women. They offer specialist advice, information, casework, advocacy, counselling and self-help support services in several community languages. Although originally set up to help black and minority women, they now support any women in need of emergency help.

Ashiana Sheffield (North East, Yorkshire and Humberside, and East Midlands)

Ashiana is an independent registered charity based in Sheffield and providing support to Black, Asian, Minority Ethnic and Refugee (BAMER) women across England. Through a mixture of in-house and partner provided support, Ashiana provide support with accommodation, personal safety, finance, parenting, substance misuse, domestic abuse, health, education, training and social integration as well as immigration and asylum advice.

Bawso (Wales)

Bawso was founded in 1995 and provides practical and emotional support to black, minority, ethnic (BME) women and migrant victims of domestic abuse, sexual violence, human trafficking, Female Genital Mutilation and forced marriage in Wales. Services provided include outreach and risk assessment, accommodation provision, subsistence, advocacy, legal and immigration support, access to medical services, training opportunities.

Birmingham & Solihull Women’s Aid (Birmingham and Solihull)

Birmingham and Solihull Women’s Aid provide frontline domestic violence and abuse support services to women and children in the Birmingham and Solihull area. The services they provide include advice and support via drop-in centres, emergency refuge accommodation, housing support and advice, community outreach, legal support (such as, criminal proceedings), family support and training for professionals.

Foyle Women’s Aid (Northern Ireland)

Foyle is a charity based in Derry and Londonderry, Northern Ireland, which aims to eliminate domestic abuse and sexual violence by supporting all victims of abuse. They provide a range of services including supported accommodation, family support and a support worker to help victims of abuse with their housing, legal issues and income and budget.

Shakti Women’s Aid (Scotland)

Shakti Women’s Aid is a charity that helps BME women, children, and young people in Scotland who are experiencing, or who have experienced, domestic abuse from a partner, ex-partner, and/ or other members of the household. In addition to the support provided as part of the pilot, Shakti also provide temporary refuge, key workers who provide practical and emotional support, consultancy and expertise (to help local authorities and others support victims of domestic abuse), as well as referrals to other support services.

Executive summary

Introduction

In July 2020, the Home Office (HO) announced the launch of a UK-wide pilot programme to support victims/survivors of domestic abuse who otherwise had no recourse to public funds (NRPF): the Support for Migrant Victims (SMV) Pilot. The Pilot was to run for a year “to support migrant victims of domestic abuse who do not have access to public funds to access safe accommodation”[footnote 2]. In the same month, HO commissioned the Behavioural Insights Team (BIT) to undertake an independent evaluation of the Pilot, in order to understand the current support available to victims/survivors with NRPF, whom the Pilot was supporting, the costs of the support, its outcomes, and the specific challenges associated with delivering it.

The independent evaluation consisted of 5 key elements:

Logic mapping workshop

- outline: development of a logic map describing the activities, outcomes, and mechanisms of the Pilot

- aim: inform the development of the research questions being used throughout the evaluation

Survey of support providers

- outline: survey of 75 different organisations that provide refuge services to victims/survivors (with access to funding and with NRPF)

- aim: understand the support available to victims/survivors of domestic abuse outside of the Pilot

Analysis of monitoring data

- outline: key data collected on 302 victims/survivors supported through the Pilot, including their demographics, support needs, support received through the Pilot, and some post-support outcomes

- aim: build a whole-programme picture of who the Pilot is supporting, the support being delivered, and the costs of delivering the support

Practitioner focus groups

- outline: 4 focus groups conducted at 2 timepoints, with managers and caseworkers from each of the delivery partners

- aim: understand the Pilot delivery, challenges faced with implementing it, and difficulties encountered by victims/survivors

Beneficiary interviews

- outline: 18 interviews with victims/survivors and ten interviews with their caseworkers

- aim: capture the experience and perceptions of victims/survivors associated with the Pilot, and build more depth of insight into outcomes

This evaluation only covers the initial Pilot period, from April 2021 to March 2022. However, HO is funding the SMV programme for a further year while they take on board lessons from the pilot; and will continue monitoring its delivery activity, outputs and outcomes to inform future policy on support for migrant victims of domestic abuse.

Key findings

Overall, our evaluation presents a mixed picture. There were clear examples of where the Pilot was performing well, particularly in meeting the immediate and emergency needs of victims/survivors. However, we also identified several areas in which victims’/survivors’ needs were not being fully met, where provision and experiences were highly dependent on the victims’/survivors’ specific circumstances, or where the administration of the Pilot placed additional burden on delivery partners.

Successes: the Pilot provided a valuable service to the 302 victims/survivors supported during its first year and filled gaps in other provision.

- outside of the Pilot, support for migrant victims with NRPF does exist; of organisations we surveyed, equal numbers provided support to those with and without RPF

- the Pilot provided emergency relief to victims/survivors that were in need, via immediate accommodation and subsistence with few barriers to access

- it worked well for those eligible for other sources of support, including DDVC and Section 17, bridging the gap between victims/survivors leaving the abusive relationship and accessing other funding sources

- the dedicated support provided by caseworkers was particularly valued by victims/survivors that were supported through the Pilot

- the Pilot provided benefits to the mental wellbeing of victims/survivors through targeted support (such as counselling and therapy) and incidental benefits from other aspects of the Pilot, including new social networks

Limitations and challenges: Pilot funding constraints made it hard for delivery providers to meet the complex needs of victims/survivors.

Sufficiency of provision

- subsistence payments provided through the Pilot were often not sufficient to cover basic expenses, and all delivery partners relied on relationships with local charities to bridge the gaps

- providing suitable accommodation within the constraints of the Pilot was a challenge for delivery partners

Complexity of cases

- many victims/survivors had complex legal situations which required more than 12 weeks to resolve - 31% (n = 93) victims/survivors were provided services for 12 or more weeks

- delivery partners did not always have the resources nor expertise to fully support victims/survivors with highly complex needs

- the language and cultural diversity of victims/survivors created additional challenges to provision

Local and regional constraints

- regional variation of available support services meant there were regional differences in terms of the quantity and quality of support provided

- the Pilot was sometimes bridging gaps in local authority provision where local authorities did not recognise their duties

Awareness of the Pilot

- awareness of the Pilot, among both potential recipients and other agencies and local services, was a barrier to effective provision

- victims/survivors were often unaware of their entitlements, and where the funding they received came from

Each of these key findings is covered more fully in Section 6: Discussion.

Conclusion

The aim of the Pilot was to provide a support net for victims/survivors of domestic abuse with no recourse to public funds, and it is meeting this aim in critical ways. In particular, the provision of accommodation and basic subsistence to victims/survivors removes a key potential barrier to them leaving the perpetrator. However, we also identified several areas in which the Pilot could better support victims/survivors and reduce the burden on providers delivering the Pilot.

Whilst it is outside our role as evaluators to provide policy recommendations, we hope that the insights contained within this report will help to provide the support needed to victims/survivors with NRPF.

1. Introduction

1.1 Background to this report

In 2017, the Queen’s Speech promised that the Government would bring forward a Domestic Violence and Abuse Bill, which was released in January 2019[footnote 3]. The Joint Committee, appointed in March 2019, published its report outlining their recommendations in June 2019[footnote 4]. The report outlined the Joint Committee’s assessment that the Bill had missed “the opportunity to address the needs of migrant women who have no recourse to public funds”. Furthermore, the report made the recommendation to explore ways to extend existing support for victims/survivors of domestic abuse with no recourse to public funds, such that vulnerable victims/survivors might access protection and support at a critical moment in their lives.

In July 2019, the Home Office published a response to the Joint Committee, in which the Home Office committed to review the overall response for victims/survivors of domestic abuse[footnote 5]. The findings were published in July 2020 and included in the conclusions was a commitment to allocate £1.5m towards a ‘Support for Migrant Victims’ pilot scheme (‘the Pilot’), which would be launched later in the year. The report outlined that the Pilot would offer emergency support to address gaps in existing provisions and gather information to help future funding decisions.

The Pilot was launched in April 2021. The Pilot has been delivered through 6 delivery partners: Southall Black Sisters (SBS) (the primary delivery partner who manages the Pilot funding), Ashiana Sheffield, Bawso, Foyle Women’s Aid, Birmingham & Solihull Women’s Aid, and Shakti Women’s Aid[footnote 6]. The services provided included accommodation services, legal support (partially funded by the Pilot), subsistence payments, counselling and support groups.

The purpose of this report is to present findings from an independent process evaluation of the Pilot conducted by the Behavioural Insights Team. The aim of the evaluation is to assess the following aspects of the Pilot:

- How the Pilot has been implemented. The process evaluation[footnote 7] aims to cast light on how the Pilot has been delivered, the profile of the victims/survivors who accessed it, and factors that affected how the Pilot was delivered.

- The journeys that victims/survivors took through the Pilot, including their outcomes. The second focus involves looking at how the journey and outcomes of victims/survivors aligned with the Pilot’s aims and how perceptions of the support provided contributed to those outcomes.

- Where the Pilot sits alongside existing support provided to victims/survivors. This helps us to understand the need for the Pilot and the gaps in provision it can potentially address.

1.2 Summary of research activities

To evaluate the Pilot, we conducted the following core research activities:

Focus groups with frontline Pilot delivery workers (practitioners)

These involved running focus groups with practitioners from across all delivery partners, which focused on understanding the implementation of the Pilot, gathering their perspectives on what has worked well, and what has worked less well.

Interviews with support recipients

We undertook in-depth interviews with recipients of the Pilot, focused on understanding the range of experiences of support and outcomes from it.

Analysis of monitoring data of recipients of the Pilot

We analysed data collected by the delivery partners throughout the Pilot to help understand who received support, including the type of support received.

We also conducted a logic mapping workshop at the start of the Pilot, to understand the core Pilot activities and how they would contribute to the intended outcomes of the Pilot from the perspective of the delivery partners.

In addition, we conducted a survey of support providers who offer assistance to victims/survivors of domestic abuse. The survey was used to understand the current support that victims/survivors are able to receive outside of the Pilot - including both those with recourse to public funds and those with NRPF. While it sits outside of the main focus of the evaluation (meaning, it did not directly contribute to the evaluation), it addresses the third aim of this evaluation: understanding where the Pilot sits amongst this support.

2. Methodology

This section provides a summary of the methodology for each component of the evaluation. More details on each can be found in the Annex – the relevant Annex is linked at the end of each subsection.

2.1 Logic mapping workshop

At the start of the evaluation, we conducted a logic mapping workshop with each of the core delivery partners, to better understand the support provided through the Pilot and its intended outcomes. The workshop was attended by at least one individual from each of the delivery partners, as well as individuals from the Home Office Analysis & Insight team overseeing the research, and was facilitated by BIT.

Through the workshop, we populated an online board with 4 features of the Pilot:

- target group

- activities

- intended outcomes

- intermediary outcomes

While the board was primarily populated by BIT facilitators based on the workshop discussions, the board was visible to all participants who were also able to add their own content. At the end of the workshop, the notes were formed into a structured logic map diagram, which was shared with workshop participants for comments. The finalised logic map formed the basis for the subsequent research questions and research design and may be found in Annex 8.1.

2.2 Research questions

Based on the activities and outcomes identified in the logic map and the prespecified aims of the Pilot evaluation, we developed specific research questions to help guide our evaluation of the Pilot. The questions focus on implementation (reach, fidelity, quality, responsiveness, and mechanisms), but also cover potential outcomes and the quality of the intervention. The questions are, however, restricted to the Pilot and its impacts – we are not evaluating the range of other programmes and measures that affect outcomes of migrant victims/survivors of domestic abuse. The overarching research questions are displayed in Table 1 below:

Table 1: Research questions

| RQ | Pilot delivery |

| 1 | How many victims/survivors are helped by the Pilot? |

| 2 | What is the profile of victims/survivors who seek support? |

| 3 | What support do victims/survivors receive through the Pilot? |

| 4 | Which parts of the Pilot were the most beneficial for victims/survivors? |

| 5 | What are the limitations of support provided through the Pilot? |

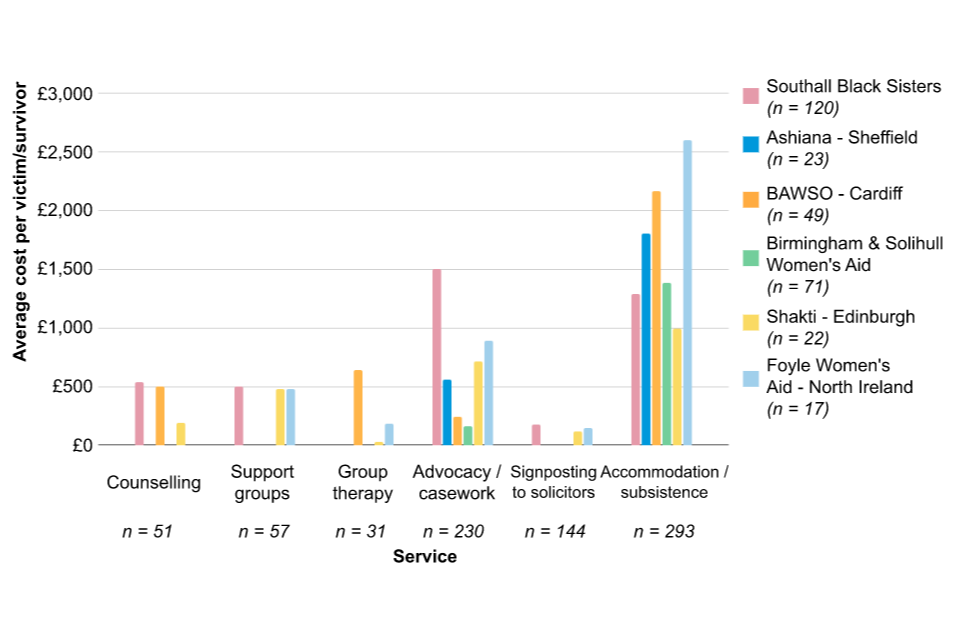

| 6 | What are the costs of providing this support? |

| 7 | Are delivery partners able to successfully deliver the Pilot? |

| Pilot outcomes | |

| 8 | What are the potential effects of the Pilot on victims’/survivors’ wellbeing? |

| 9 | What are the potential effects of the Pilot on victims’/survivors’ independence? |

| 10 | What are the potential effects of the Pilot on immigration outcomes? |

Specific sub-questions are presented in sections on each research approach. A full list of research questions, sub-questions and methods can be found in Annex 8.2.

2.3 Survey of support providers

We conducted an online survey of 75 UK organisations that provide support to migrant victims/survivors of domestic abuse. The main focus of the survey was on understanding which organisations provide support, the scale and costs of provision, and the profile of victims/survivors that come forward.

The survey was sent to organisations identified through 3 channels:

- organisations listed in the Women’s Aid Gold Book

- existing mailing lists, including the Women’s Resource Centre and NRPF Network

- organisations suggested by other survey respondents

We received a total of 93 responses and removed 10 seemingly duplicate responses[footnote 8]. This resulted in a final sample of 83 responses from a total of 75 different organisations (we received more than one response for 6 organisations).

2.4 Pilot monitoring data

Monitoring data was routinely collected by delivery partners throughout the Pilot. It was only collected when a victim/survivor left the Pilot, and therefore does not include victims/survivors who were still being supported at the Pilot end. Data were provided to BIT on a quarterly basis and comprised 302 individuals that had exited the Pilot by the end of quarter 4, January to March 2022 (a further 123 victims/survivors were still being supported at the end of the Pilot period).

Some delivery providers entered all victims/survivors for a quarter under the first month of that quarter (for instance, victims/survivors leaving the Pilot between October to December 2021 were all recorded under October 2021). Where this might affect our interpretation of the figures, we have noted this in the text.

2.5 Interviews

Interviews were conducted with 18 victims/survivors between February and May 2022.

Interviewees were identified through a mixture of purposive sampling and convenience sampling by delivery partners (more details are available in Annex 8.5). We generally achieved high diversity across our sample with respect to nationality, ethnicity, age, marital status and whether the victim/survivor had children. However, all our interviewees were heterosexual women, and we did not interview any victims/survivors support by Bawso (who did not share details of victims/survivors who were willing to be interviewed as part of the evaluation).

Interviews were semi-structured and followed a pre-agreed topic guide (see Annex 8.6.3). They were a mixture of in-person and remote, depending on the recommendations of the recruiting delivery partner. Interpreters were arranged when needed, and a safeguarding and distress protocol was in place to protect research participants (see Annex 8.3 for a full discussion of research ethics). All interviews were recorded and transcribed, before being analysed using the Framework Approach[footnote 9]. Co-coding was used to highlight any discrepancies in the interpretation of the data. In some cases, with the permission of victims/survivors, additional conversations were held with their caseworkers after the interview to better understand their case. Researchers made notes through these conversations (rather than recording them) which were considered alongside the main interview analysis.

Throughout this report, case studies and quotations have been anonymised to protect the identities of research participants.

2.6 Focus groups

Four online focus groups were conducted for this evaluation: 2 in January and 2 in March. One from each pair was conducted with programme managers, and one with caseworkers. We aimed to have one representative from each of the 6 delivery partners, but this was not always possible due to the limited availability of the caseworkers and Pilot managers. Conversely, some delivery partners sent 2 attendees for the manager focus groups. The spread of delivery partners and total attendees is presented in Table 2.

Table 2: Focus group attendees, by delivery partner

| Focus group | Delivery partner | Total attendees | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SBS | B&S | Ashiana | Shakti | Foyle | Bawso | ||

| Manager 1 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | 6 |

| Manager 2 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | 7 |

| Caseworker 1 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | 3 | |||

| Caseworker 2 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | 3 |

As with the interviews, focus groups were recorded and transcribed and analysed using the Framework Approach.

3. Existing support for victims/survivors

In this section, we summarise the context in which the Pilot was introduced, based on the findings of our survey, in which we collected data for 83 respondents from 75 UK organisations[footnote 10] that provide refuge services to victims/survivors with access to funding and with NRPF.

3.1 Summary of survey findings

The majority of organisations provide services to both victims/survivors with access to public funds and those with NRPF

Of the organisations we surveyed, the clear majority (76%, n = 63) provided services to both victims/survivors with access to public funds and those with NRPF. Of the remaining 24% (n = 20), equal numbers provided services to either victims/survivors with access to public funds (n = 15) or with NRPF (n = 15). Within our sample, therefore, a victim/survivor with NRPF would have access to support at the same number of organisations as a victim/survivor with access to funding.

Table 3: To whom services were provided by survey respondents, in order of descending frequency (n = 83)

| Provided services to victims/survivors with access to public funds | Provided services to victims/survivors with NRPF | Provided services to non-migrant victims/survivors | Proportion of respondents |

|---|---|---|---|

| ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | 70% (n = 58) |

| ✔ | 11% (n = 9) | ||

| ✔ | 7% (n = 6) | ||

| ✔ | ✔ | 6% (n = 5) | |

| ✔ | ✔ | 5% (n = 4) | |

| ✔ | ✔ | 1% (n = 1) |

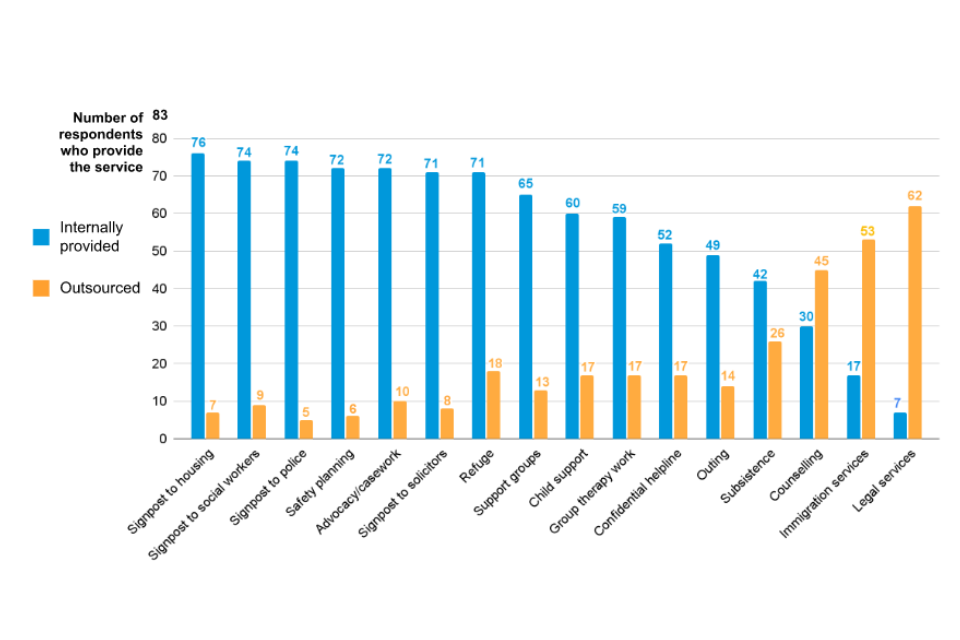

The most common services provided were refuge, signposting, advocacy, safety planning, and child support; less-common services often were outsourced

Respondents tended to provide the whole spectrum of services that victims/survivors require, including refuge, signposting, advocacy, safety planning, and child support[footnote 11]. More specialist services that may require specific training, such as counselling, immigration services, and legal services, tended to be outsourced.

Figure 1: Services provided (internally vs. outsourced) by respondents (n = 83)

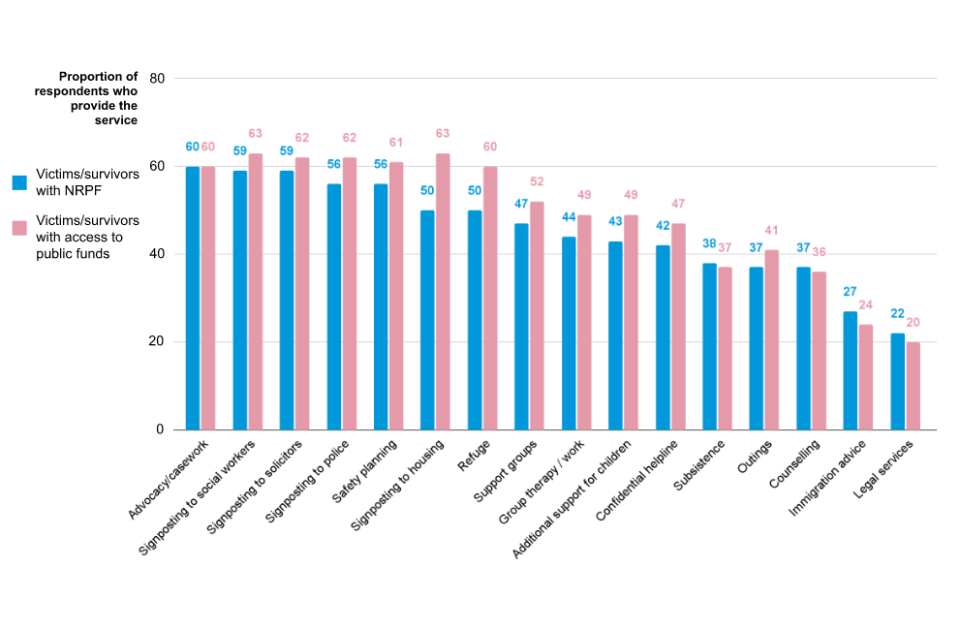

Signposting to housing and refuge were provided less to victims/survivors with NRPF than those with access to public funds

The biggest difference in service offerings between victims/survivors with public funding and those with NRPF was signposting to housing and refuge. As shown by Figure 2, these services were provided less often to victims/survivors with NRPF than those with access to public funds (63 respondents provided signposting to housing to victims/survivors with access to public funds versus 50 respondents to victims/survivors with NRPF; 60 respondents provided refuge to victims/survivors with access to public funds versus 50 respondents to victims/survivors with NRPF).

Figure 2: Services provided by respondent (victims/survivors with access to public funds vs. NRPF) (n = 83)

Lack of capacity and lack of funds were cited as the main reasons for service providers being unable to support more victims/survivors with NRPF

When asked why victims/survivors with NRPF were turned away, the most common reason provided (8 respondents) was that there was no capacity in the refuges for victims/survivors. Some respondents said that lack of funds meant they could not provide refuge (4 respondents), and required either housing benefits, a DDV concession or signed agreement from social services that they would provide funding. Respondents were clear that in cases where support couldn’t be provided, they would support victims with finding other services, or by referring them to other agencies or helplines.

Lack of funds was highlighted as being a barrier to multiple other services, including immigration support and legal advice

Respondents said that there often was not funding to support victims/survivors with NRPF, which limited how many victims/survivors they could support. DDVC is often relied upon in absence of other funding to provide access to refuge services; without it, many respondents could not provide housing. Others said that providing funding or housing was very challenging for victims/survivors with children where social care services are unable to provide funding.

Overall, the findings from the survey indicated that the lack of funding for victims/survivors with NRPF was a barrier for victims/survivors starting a life without the perpetrator, and that there was a strong need for funding to provide these individuals with refuge. These findings corroborated the rationale for the introduction of the Pilot, particularly the need for safe accommodation for victims/survivors who had just escaped abusive relationships.

3.2 Limitations of the survey findings

We took several steps to ensure our sample was representative, including:

- using snowball sampling and mailing lists to reach organisations that were not captured in the Gold Book to mitigate selection effects

- sending multiple reminders to potential respondents and keeping the survey open for several weeks, which increased the likelihood that individuals working in busy organisations had time to respond

However, our sample may not be representative of services that provide refuge in the UK for 2 key reasons:

- Services excluded from survey invites. Due to our sampling approach, we had to exclude any service providers that did not have an email address when identifying organisations to provide the survey link to. This may have excluded small service providers who do not have an email address. Moreover, as we only had one email address per organisation, it may have excluded organisations that have separate email addresses for different geographical regions[footnote 12].

- Services did not respond to the survey. We received a 30% completion rate for the original list of 355 organisations, which may have introduced selection bias into our sample. The organisations that did not respond may be different to those that did, meaning that our sample is not representative: for example, short-staffed organisations may not have responded due to their workload, and thus would not be represented in our survey.

A further limitation is data quality. In particular, the data quality for the questions relating to the number of victims/survivors supported was mixed – 36 respondents didn’t provide any data at all, with around half saying they didn’t know the answer. This adds an additional layer of selection bias in responses, if not knowing the answer also relates to the size of the organisation or the demographics of those they serve.

The organisations most likely to be excluded based on the limitations above are smaller organisations, who may be less likely to have a contact email and less likely to have accurate data. However, given that a quarter of our sample provided support to 10 or fewer victims/survivors, we feel we have captured at least some of these smaller organisations.

4. Pilot delivery

In this section, we discuss how the Pilot was delivered, including the number and profile of victims/survivors, and the support they received.

4.1 How many victims/survivors were helped by the Pilot? [RQ1]

302 victims/survivors were supported over the course of the Pilot – fewer than originally anticipated

Our analysis of the monitoring data indicated that 302 victims/survivors left the Pilot during the first 12 months of the Pilot (April 2021 to March 2022). We note that the monitoring data only captures victims/survivors who left the Pilot (meaning, the end of services funded by the Pilot) and therefore does not include victims/survivors still being supported at the end of the evaluation period (we have been told that a further 123 victims/survivors were still being supported). Importantly, we do not have data on the number of victims/survivors that sought help but were not able to receive it.

We understand that the Pilot had originally aimed to support between 500 and 1,000 victims/survivors between April 2021 and March 2022. We heard from the focus groups with practitioners that the COVID-19 pandemic may have made it harder for victims/survivors to find out about and seek support, which may have been why the final numbers were lower than anticipated. Table 4 presents the number of victims/survivors leaving the Pilot by service provider.

Table 4: Number of victims/survivors leaving the Pilot by service provider (n = 302)

| Service provider | Region of focus | Frequency of victims/survivors | Proportion of victims/survivors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ashiana Sheffield | North East, Yorkshire and Humberside, and East Midlands | 23 | 8% |

| Bawso | Wales | 49 | 16% |

| Birmingham & Solihull Women’s Aid | Birmingham and Solihull | 71 | 24% |

| Foyle Women’s Aid | Northern Ireland | 17 | 6% |

| Shakti Women’s Aid | Scotland | 22 | 7% |

| Southall Black Sisters[footnote 13] | London & South-East | 120 | 40% |

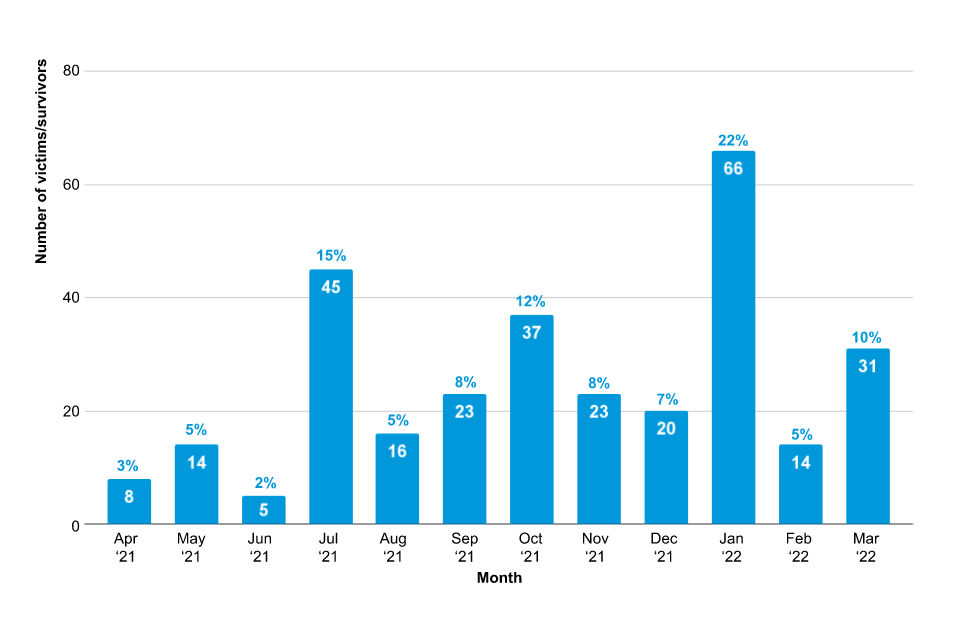

The number of victims/survivors being supported by the Pilot increased over the course of the year

From the monitoring data we see that the number of victims/survivors leaving the Pilot generally increased across the course of the 12 months (see Figure 3). The distinct peaks at the start of each quarter (April 2021, July 2021, October 2021 and January 2022) are caused by some delivery partners recording all departures for the quarter within the first month, so overall figures by quarter are more reliable (see Table 5).

The largest increases were between:

- the first and second quarter (April to June 2021, compared with July to September 2021)

- the third and fourth quarter (October to December 2021, compared with January to March 2022)

The first and second quarter movement will be explained, in part, by the fact that these figures are departures from the Pilot. Many entries to the Pilot between April to June 2021 will be recorded in July to September 2021, and, unlike other quarters, no entries from a previous quarter will be recorded in April to June. The increase between the third and fourth quarters (October to December 2021 and January to March 2022) does not have a similarly mechanical explanation, but may have been caused by the increase in accommodation stipend between January to March 2022.

Figure 3: Number of victims/survivors leaving the Pilot by month (n = 302)

Table 5: Number of victims/survivors leaving the Pilot by quarter (n = 302)

| Quarter | Frequency of victims/survivors | Proportion of victims/survivors |

|---|---|---|

| Q1 (Apr - Jun ‘21) | 27 | 9% |

| Q2 (Jul - Sep ‘21) | 84 | 28% |

| Q3 (Oct - Dec ‘21) | 80 | 26% |

| Q4 (Jan - Mar ‘22) | 111 | 37% |

Victims/survivors found out about the Pilot through a range of channels

The focus groups and interviews we conducted highlighted that many victims/survivors assumed there would be no support for those with NRPF. Instead, some victims/survivors came to find out about the delivery partners - and subsequently the Pilot - in a moment of extreme need: for instance, by recommendation from the police after a severe incident of domestic abuse. It is important to note that victims/survivors found out about specific delivery partners, and how they could support them - but they did not necessarily understand how this support was funded and about the Pilot. We also found that there were other channels by which victims/survivors found out about the Pilot including:

- proactive contacting: victims/survivors looked online for organisations that supported women who faced domestic abuse, and directly reached out to the helpline

- suggestion by family members: victims’/survivors’ family members recommended they get in touch with a specific organisation

- police referral: when police are called to a severe domestic abuse incident, they usually provide victims/survivors with one or more organisations that they can contact for support

- GP referral: a number of victims/survivors said that they first heard of organisations that could support them while discussing their mental/physical health with their GP

- social services referral: some victims/survivors are in contact with social services, who gave them details of the delivery partners

- voluntary organisation referral: some victims/survivors were already in contact with other voluntary organisations; these bodies identified that victims/survivors and their children were experiencing domestic abuse and referred them to the delivery partners

- word of mouth: victims/survivors found out about organisations that may help them by hearing it from others: for example, hearing about it in a supported accommodation

Awareness of the Pilot may have been a barrier to uptake

Delivery partner staff reported that wider awareness of the Pilot was a key challenge in delivery, and that raising awareness of the Pilot was essential in ensuring that victims/survivors were referred to the Pilot. Before the Pilot, this type of support would not have been available for victims/survivors with NRPF, so services that typically refer them for support (as well as victims/survivors themselves) were often unaware that such support was now available. For example, some victims/survivors became homeless and were supported by a range of voluntary organisations who were unaware they could refer them to one of the delivery partners. Delivery partners reported doing extensive advocacy and awareness raising work with other community organisations, social services, and GPs to ensure all victims/survivors with NRPF would receive the support they needed. This included advocacy at the individual level (such as supporting victims/survivors with their specific case, and making sure other professionals were aware of the victim/survivor’s specific entitlements); and at the system level (for example, liaising accommodation providers, health services and other voluntary organisations to ensure they were aware that Pilot funding was available and encourage them to provide support or refer victims/survivors who would benefit from it).

“We have one of our caseworkers that has been doing some outreach work to make sure that other agencies and bodies know about this pilot, you know we need others to know this support is available to ensure that these women get the support they need.”

[Caseworker]

The lack of awareness of the Pilot and understanding of the funding available to victims/survivors with NRPF also created barriers for delivery partners who wanted to partner with other agencies to provide key services. Delivery partners reported having difficulty accessing support services, such as accommodation, due to agencies’ preconceptions that there was no funding available to support victims/survivors with NRPF. Delivery partners reported that because of these preconceptions, other agencies were concerned that providing services to victims/survivors with NRPF would be costly to them.

Delivery partners felt that awareness-raising and advocacy were key in addressing these issues. Delivery partners reported doing a lot of advocacy work with other agencies to publicise the Pilot:

“We’ve already mentioned all the awareness-raising that we’re having to do outside externally… because in [this city] we have got no accommodation providers.. so I had to do some advocacy and some awareness-raising with some of the supported accommodation providers, which is way out of my remit.”

[Caseworker]

It was also suggested that it would take at least a year to generate publicity for the Pilot which could help raise agencies’ awareness of the Pilot:

“We all know that for any project to start and to get its name, and the publicity, it takes a year. To raise publicity of this programme itself to take time to say there is money now, to the agencies as well, there is funds now, you can take women, that, in itself, is a big hurdle.”

[Pilot Manager]

The awareness raising activities conducted by delivery partners may also help explain the increase in the number of victims/survivors supported by the Pilot over the course of the year.

4.2 What is the profile of victims/survivors who seek support? [RQ2]

We analysed the monitoring data to assess the profiles of victims that were provided services by the Pilot. We note that we were unable to directly assess the profiles of victims that sought support (which includes both those who received support and those who were not able to receive it after seeking it). This was due to no data on the profiles of victims/survivors who sought help being directly available.

The profile of the victims/survivors leaving the Pilot is generally in alignment with the target group identified as part of the logic model. The exception to this is the inclusion of victims/survivors with children, as the expectation was that victims/survivors with children would receive support via social services under Article 17 of the Children Act 1989 - and thus not require support from the Pilot.

Victims/survivors tended to be female and heterosexual

The majority of victims/survivors tended to be female (97%; n = 294), and they also tended to be heterosexual (see Table 6).

Table 6: Gender and sexual orientation of victims/survivors that left the Pilot (n = 302)

| Sexual orientation | Female victims/survivors | Male victims/survivors |

|---|---|---|

| Bisexual | 2 | 0 |

| Gay or lesbian | 6 | 0 |

| Heterosexual | 270 | 5 |

| Prefer not to say | 7 | 0 |

| Unknown | 9 | 3 |

| Total | 294 (97% of total) | 8 (3% of total) |

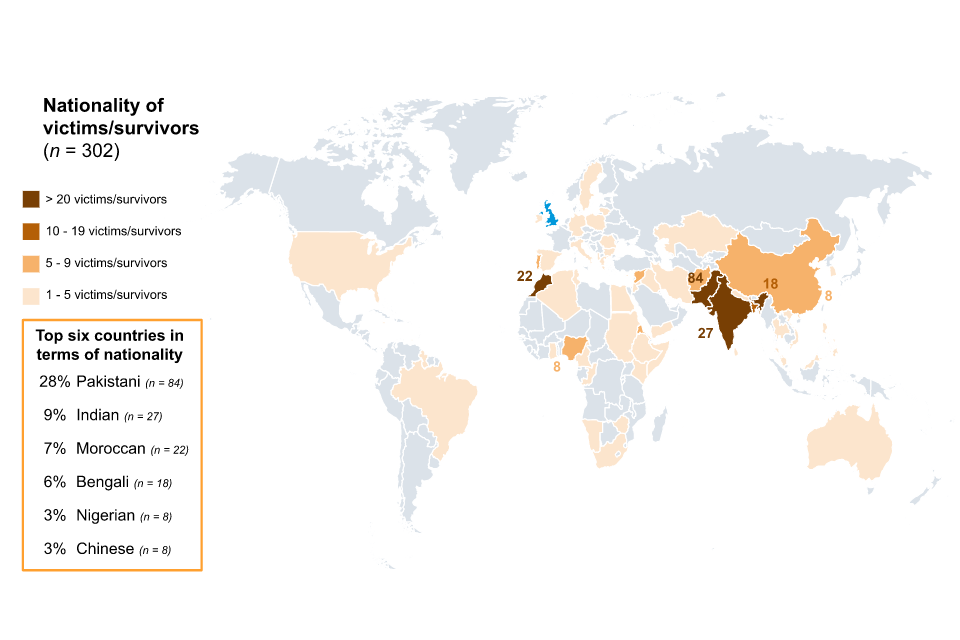

Victims/survivors were predominantly Asian or Asian British, and Muslim

A narrow majority of victims/survivors were Asian or Asian British (51%, n = 154), and Muslim (51%, n = 154). While the most prevalent nationality was Pakistani (28%, n = 84), there was a spread of nationalities from across the world, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Nationality of victims/survivors (n = 302)

Table 7: Ethnicity of victims/survivors leaving the Pilot

| Ethnicity | Frequency of victims/survivors | Proportion of victims/survivors |

|---|---|---|

| Asian/Asian British | 154 | 51% |

| Black/African/Caribbean/Black British | 53 | 18% |

| Other | 40 | 13% |

| White | 29 | 10% |

| Arab | 14 | 5% |

| Prefer not to say | 7 | 2% |

| Mixed/Multiple ethnic group | 3 | 1% |

| Unknown | 2 | 1% |

| *Due to rounding, totals will not always sum to 100% |

Table 8: Religion of victims/survivors leaving the Pilot

| Religion | Frequency of victims/survivors | Proportion of victims/survivors |

|---|---|---|

| Muslim | 154 | 51% |

| Christian | 54 | 18% |

| Prefer not to say | 34 | 11% |

| None | 17 | 6% |

| Sikh | 13 | 4% |

| Catholic | 7 | 2% |

| Buddhist | 6 | 2% |

| Hindu | 5 | 1% |

| Other | 5 | 1% |

| Agnostic | 1 | <1% |

| Jewish | 1 | <1% |

| Zoroastrian | 1 | <1% |

| *Due to rounding, totals will not always sum to 100% |

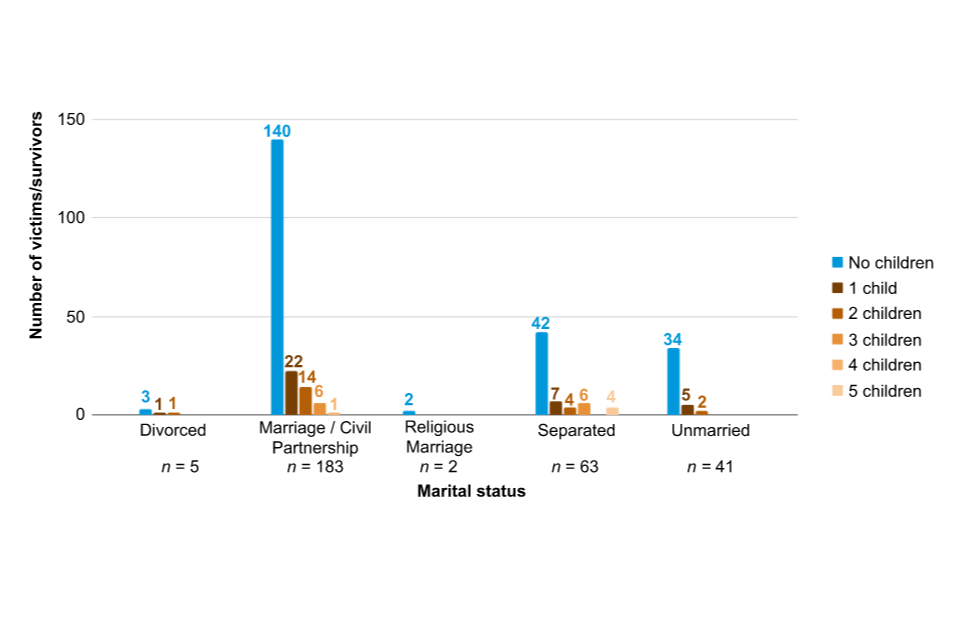

Most victims/survivors did not have children and were in a marriage or a Civil Partnership

The majority of victims/survivors did not have any children (75%, n = 221), and were either married or in a Civil Partnership (62%, n = 183).

Figure 5: Marital status and children of victims/survivors that left the Pilot (n = 294)

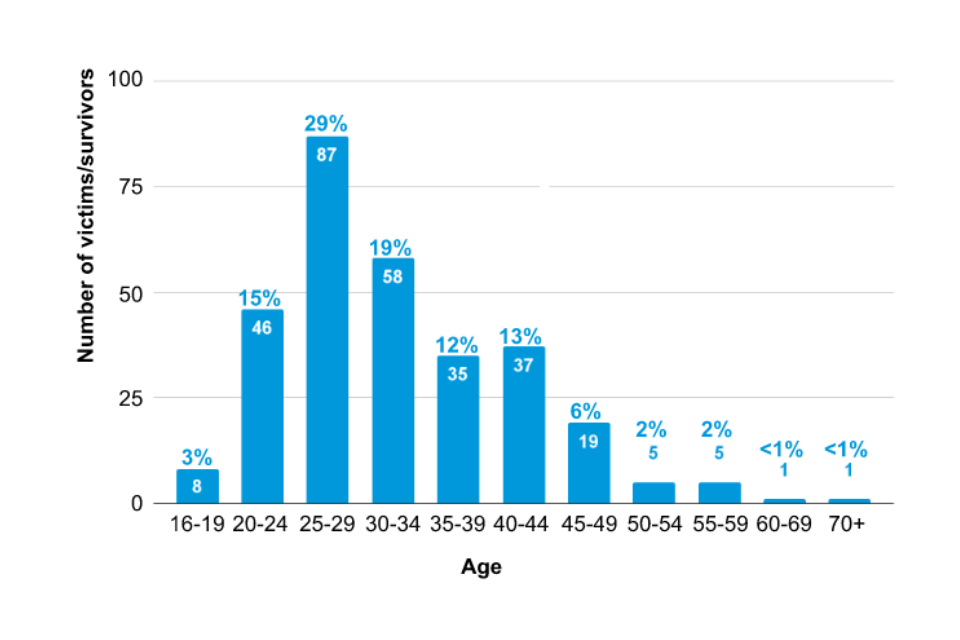

While there was a range of ages of victims/survivors, most were aged from 20 to 34

Figure 6 presents the range of ages of victims/survivors. The most common age bracket was 20 to 24 (29%, n = 87), but we saw a range of ages.

Figure 6: Age of victims/survivors that left the Pilot (n = 294)

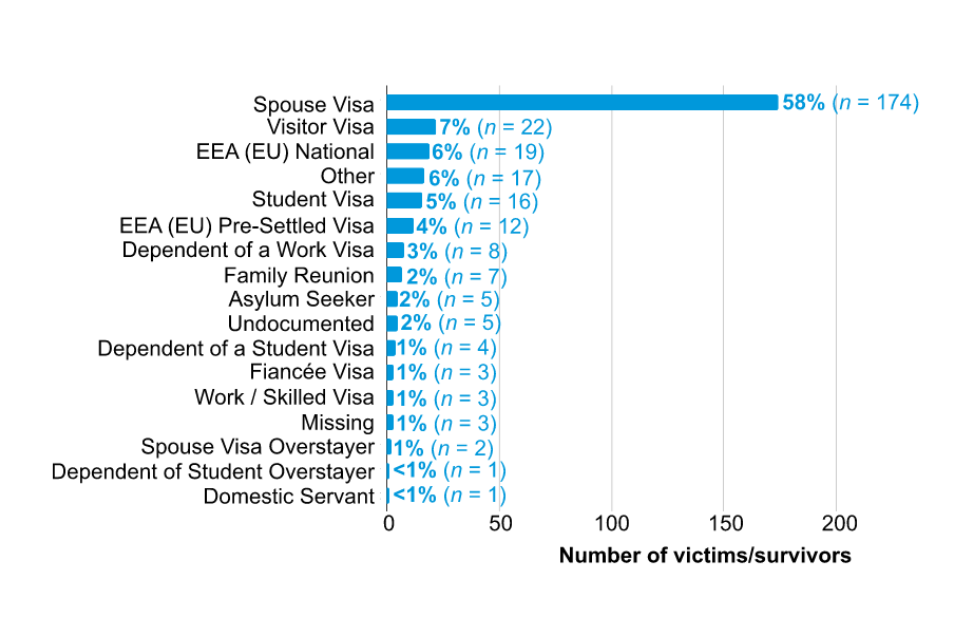

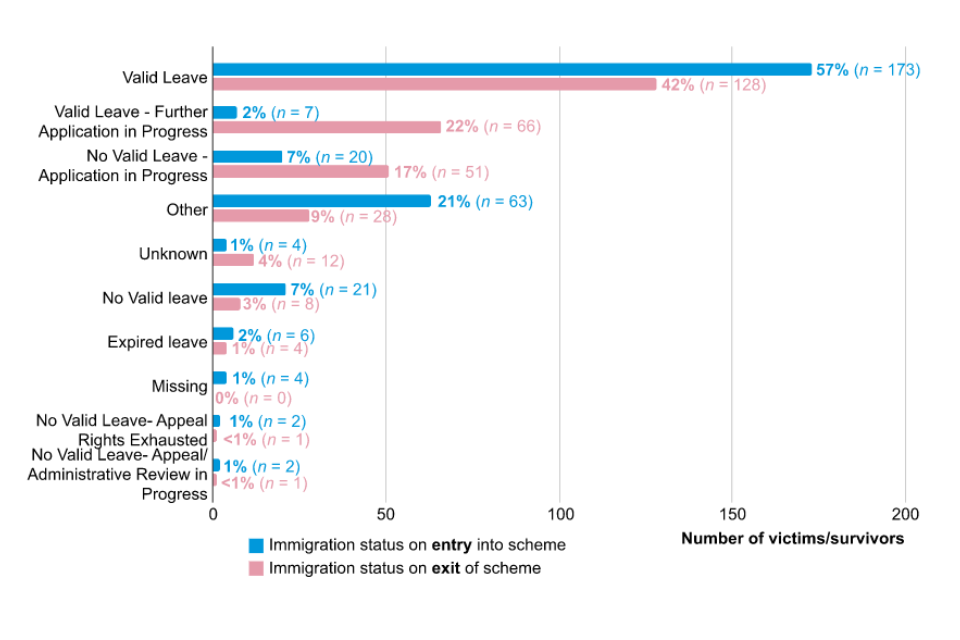

Most victims/survivors had Valid Entry Clearance as their immigration status on entry to the UK, and came into the UK on a Spouse Visa

The majority of victims/survivors entered into the UK on a Spouse Visa (58%, n = 174). An even greater majority had an immigration status of Valid Entry Clearance on entry into the UK (91%, n = 275).

Table 9: Immigration status on entry to the UK of victims/survivors leaving the Pilot (n = 302)

| Immigration status on entry | Frequency of victims/survivors | Proportion of victims/survivors |

|---|---|---|

| Valid Entry Clearance | 275 | 91% |

| No Valid Entry Clearance / Permission | 10 | 3% |

| Unknown* | 8 | 3% |

| Permission Granted at Border | 4 | 1% |

| Other* | 3 | 1% |

| Missing* | 2 | 1% |

* The monitoring data does not provide additional detail on the specific cases underpinning these variables. From the interviews, it appears that some victims/survivors had low knowledge of their immigration status and rights on entry, which may explain some unknown and missing data.

Figure 7: Route of entry into the UK of victims/survivors that left the Pilot (n = 302)

4.3 What support do victims/survivors receive through the Pilot? [RQ3]

In this section, we discuss the support that victims/survivors receive through the Pilot as a whole before discussing each service in detail, providing an overall description of the service that was provided, what worked well, and what could be improved for each service.

4.3.1 Overview of support

There were 6 broad stages of the Pilot for victims/survivors

Victim/survivor journeys through the Pilot were very diverse and depended on their needs, immigration status, and entitlements. However, the broad stages of the journey were similar across the majority of cases we discussed with caseworkers, managers, and victims/survivors themselves:

- Entry into the Pilot. Victims/survivors got in touch with the organisation either proactively by calling the helpline or when being supported by someone who is referring them.

- Needs assessment. Victims/survivors met with staff from delivery partners (usually their caseworkers) to discuss their story and their needs.

- Accommodation. In most cases victims/survivors were immediately placed in emergency accommodation to remove them from further danger or harm.

- Understanding eligibility. Victims/survivors discussed their eligibility for entitlements and visas with their caseworkers. Some discussed these with a solicitor.

- Receiving support. Victims/survivors received support such as accommodation, subsistence and counselling through the Pilot. Caseworkers provided them with ongoing guidance on next steps.

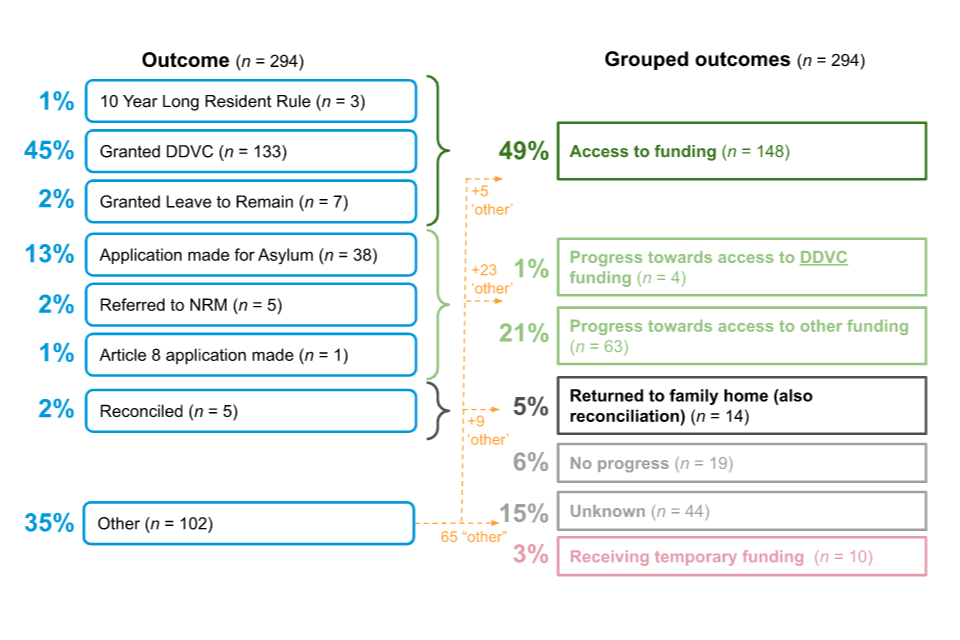

- Exit from the Pilot. Victims/survivors exited the Pilot usually by transitioning into another form of support, for example, receiving public funds through the DDVC, support from social services under Article 17, or asylum accommodation.

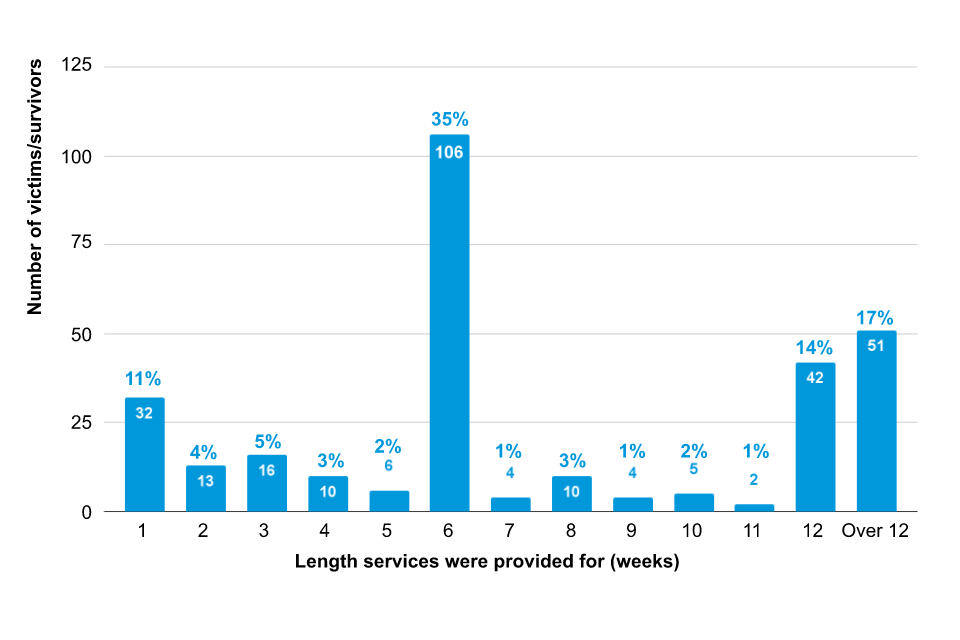

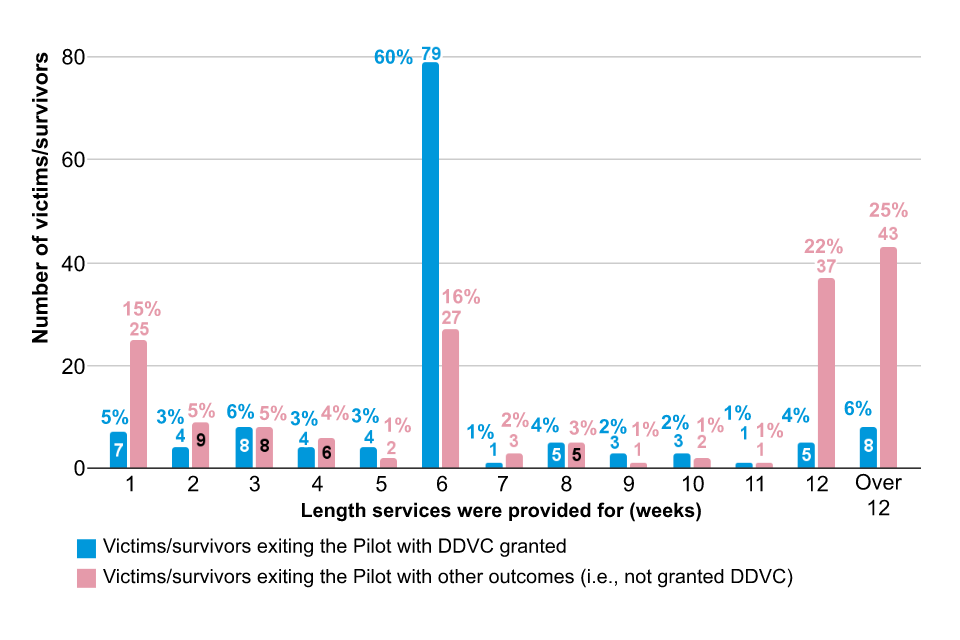

Most victims/survivors left the Pilot after either 6 weeks, or 12 or more weeks

The Pilot support was originally intended to last for up to 12 weeks per victim/survivor, or 6 weeks for victims/survivors eligible for DDVC. From January 2022 however, delivery partners were given more discretion to extend funding if needed.

Figure 8 presents the length of services provided to victims/survivors from the monitoring data (these figures are for any support as the monitoring data did not distinguish between lengths of support for different services). We see spikes in the number of victims/survivors supported for exactly 6 weeks (35%, n = 106) and 12 weeks (14%, n = 42), suggesting that in many cases victims/survivors were supported for as long as the Pilot would allow. In Section 5.1 we discuss these figures in relation to whether victims/survivors were granted DDVC, but the headline finding is that the majority (75%, n = 79 out of 106) of victims/survivors leaving the Pilot after 6 weeks had been granted DDVC, whereas those leaving after 12 weeks were very rarely leaving with DDVC (16%, n = 8 out of 51).

There was, however, a substantial proportion of victims/survivors supported for over 12 weeks (17%, n = 51), and this proportion was broadly consistent across quarter 1 to quarter 3 of delivery (April 2021 to December 2021) and quarter 4 of delivery (January to March 2022).

Figure 8: Length of services provided to victims/survivors leaving the Pilot (n = 301)

There was a diverse range of support provided, which broadly aligned with the provisions identified in the logic model

In the logic model developed with delivery partners, the core support provisions were identified as:

- safe accommodation

- subsistence payments

- legal support

In addition, the Pilot would “provide wrap-around support, included but not limited to: counselling services, support groups, translation and interpretation services.” (see Annex 8.1 for the full logic model).

Our interviews and focus groups provided more insight into this additional wrap-around support. In line with the logic model, a large part of this was wellbeing support including counselling and support groups. In-kind support, such as clothes, vouchers and access to phones and computers, was also an important part of this support. Caseworkers were not explicitly noted within the logic model, but it was clear from the qualitative research that they were a key aspect of the support provided. As well as helping victims/survivors access the other forms of support, they provided advocacy for the victims/survivors and were a source of emotional support and guidance.

The main types of support provided through the Pilot are summarised in Table 10 below. We elaborate more on each of these types of support subsequently in this section. However, it is worth noting from Table 10 that the funding for the Pilot was designed to cover some of these support types, but some were additional to the core Pilot support.

Needs assessments were used to identify the support each victim/survivor needed, but there was a lot of variation in their implementation across partners

In the logic model for the Pilot, developed with delivery partners, needs assessments would be regularly conducted with victims/survivors in order to identify the wrap-around support they needed. In practice, we found there was significant variation in how these were conducted.

We reviewed needs assessments from 2 delivery partners. Both contained information on the victims’/survivors’ history of abuse, their housing and financial situation, any health needs, whether they had children, and whether other agencies were involved in providing support. However, the structure and level of detail varied substantially. One was a reasonably succinct form, with 10 categories and corresponding actions required. A completed form was roughly 3 pages long. The other was very extensive, and included information on, for example, any ongoing court orders and victims’/survivors’ immigration status. It also included a DASH risk checklist, designed for assessing risk amongst victims of domestic abuse. A completed form was roughly 15 pages long.

Not all the providers conducted written needs assessments, instead conducting them verbally and more informally. We spoke to one of the delivery partners about this process and they were able to provide a detailed account of a victim/survivor’s identified needs but did not have a formal document for it. Similarly, one of the delivery partners working with SBS provided an email summarising the questions they asked of victims/survivors at the start of support, and the needs of the specific victim/survivor we had sampled for the needs assessment but noted they did not have a written document containing the assessment.

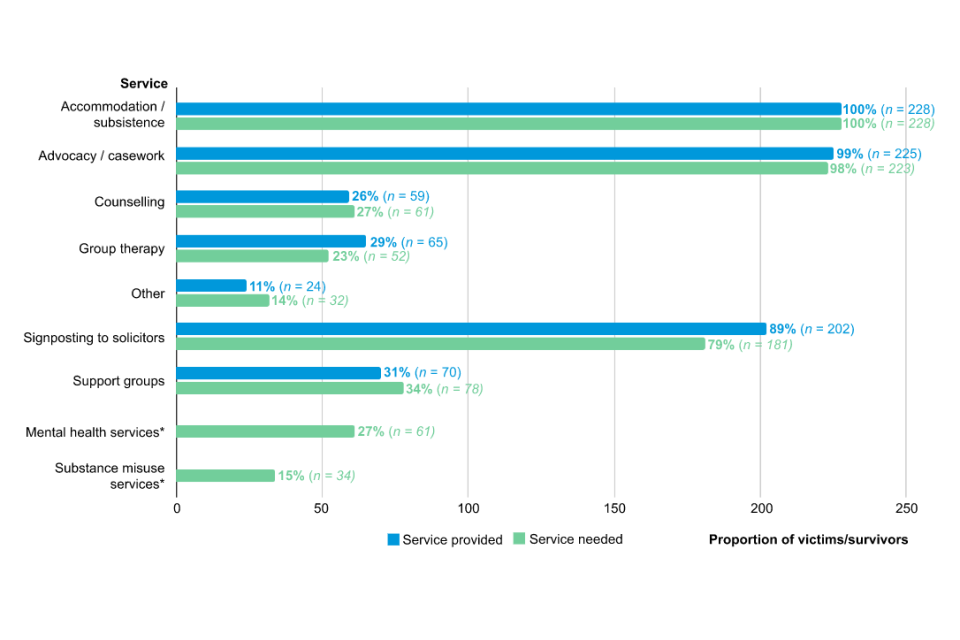

There was significant variation in the support received, reflecting the differing needs of victims/survivors

Figure 9 shows the percentage of victims/survivors receiving each type of support. While all victims/survivors received accommodation, and nearly all received advocacy/casework and signposting to solicitors, there is much more variation with counselling, group therapy, and support groups.

This appears to be driven, in large part, by the different needs of victims/survivors. Whilst there was variation in how needs assessments were conducted, the monitoring data included variables on the identified needs of victims/survivors. Figure 9 shows a generally close relationship between the proportion of victims/survivors that were identified as needing a service and the proportion who received it. There was also generally a strong correlation at the individual level between whether a victim/survivor was identified as needing a service and whether they received it. However, in some cases, a higher proportion of victims/survivors were identified as being provided with a service than were identified as needing it. This is particularly true for signposting to solicitors and group therapy. Figure 9 suggests that not all victims/survivors needed these services, indicating the difference with respect to the needs of victims/survivors who left the Pilot. We do not have clear evidence of why this was the case. However, some delivery partners said they provided group therapy as standard which may explain its overprovision. Similarly, signposting in itself is broadly costless, so may have been done as standard in many instances (which is consistent with the very high proportion [89%] of victims/survivors who were signposted to solicitors).

Figure 9: Proportion of victims/survivors receiving each service during the Pilot, relative to their identified needs (n = 228)[footnote 14]

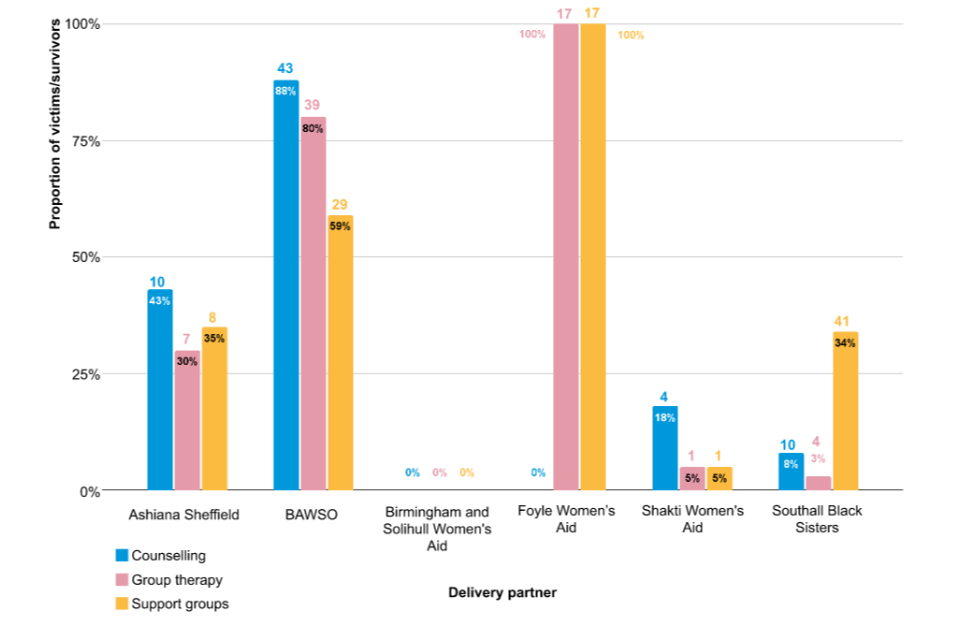

The support provided also varied by delivery partner, which appears to be driven by differences in their offer

While some services were almost universally provided by all delivery partners, for other services there were substantial differences between delivery partners in how often they were provided. This was particularly evident for counselling, group therapy and support groups, as shown in Figure 10. Some providers offer some of these services but not others (Foyle, for example, offers group therapy and support groups to all victims/survivors, but does not offer individual counselling). We note that Birmingham & Solihull Women’s Aid did not offer any of these services, hence the figure displays 0% for all services.

It is important to understand that the support provided to victims/survivors was funded through a blended model, combining the Pilot’s and the delivery partners’ funds. This meant that the quality and offer of services often relied on how much additional funding delivery partners could provide.

Figure 10. Proportion of victims/survivors services were provided by delivery partner (n = 302)

Table 10: Summary of support provided through the Pilot

| Type of support | Description |

| Accommodation (provided through Pilot funding) | Emergency accommodation was quickly provided to victims in need by organisations. Victims/survivors were mainly hosted in shared housing or other accommodation facilities such as vetted B&Bs with other victims/survivors with NPRF. Victims/survivors generally had an independent bedroom in the accommodation with shared communal spaces such as kitchens. Some had independent bathrooms. |

| Subsistence payments (provided through Pilot funding) | Subsistence payments ranged between £40 to £60 a week. Payments were initially £40 a week and then they increased to £50 a week, some delivery partners paid victims/survivors £60 a week. Some received it as a lump sum payment while others received it as a weekly instalment. Victims/survivors stopped receiving the subsistence payments when they had access to public funds. However, in some cases, delays and system errors meant that victims/survivors faced time gaps with no access to financial support. |

| In-kind support (not provided through Pilot funding) | Delivery partners supported victims/survivors to source other forms of in-kind support including things such as: Food from foodbanks. Smartphones. Essential travel. Internet access or mobile data. Toiletries including menstrual products. Vouchers for travel. Clothes. In-kind support was not funded through the Pilot but was sourced by delivery partners through other voluntary organisations. Access to these types of in-kind support was very heterogeneous as it depended on delivery partners’ networks. |

| Caseworkers (provided through Pilot funding) | Victims/survivors were assigned to a caseworker when they entered the Pilot - most had the same caseworker follow their case while some experienced changes in their caseworker throughout the Pilot. Caseworkers and victims/survivors had frequent debriefs. Caseworkers followed their case, providing emotional support, legal and bureaucratic support, signposting victims/survivors to other services. |

| Legal and bureaucratic support (partially provided through Pilot funding) | Delivery partners supported victims/survivors with their bureaucratic and legal needs in 3 ways: Through caseworkers or delivery partner staff. By signposting them to pro-bono legal advice. By applying for funded legal aid when eligible to apply for DDVC/DVILR, or by making an application for Exceptional Case Funding. Legal and bureaucratic support provided to the victims/survivors included: Support filling forms. Signposting to pro-bono solicitors. Support completing administrative tasks to settle immigration status (for example, providing their biometrics). Support putting the case to social services that they should be supported under Article 17. Providing interpreters. Support liaising with the police (for example, for document retrieval). Support setting up bank accounts to receive entitlements. Legal support to file for divorce. Legal support to understand immigration choices, and to complete application to settle status if eligible. Legal support to settle family legal disputes, for example, child custody. The Pilot did not directly fund legal aid for victims/survivors. The fund covered some of the delivery partners’ costs in finding pro-bono legal help or applying for legal aid, but not in its entirety. |

| Support for mental health and wellbeing (partially provided through Pilot funding) | Like other forms of support, wellbeing support varied greatly across providers. All victims/survivors received emotional support from their caseworker, others also received more tailored forms of support. Delivery partners provided wellbeing support in a number of ways to victims/survivors including: Regular catch-ups and debriefs with caseworkers. Support groups with other victims/survivors, offered in person or virtually. These sessions featured group activities such as dancing or creative writing. Therapy and counselling. Support accessing mental health care through the NHS, for victims/survivors with diagnosed mental health conditions. Occasional trips in the local area to places of natural beauty. Support finding volunteer work (for example, support finding them a volunteer role at a local charity shop). The Pilot covered the costs of the caseworkers’ work as well as therapy and counselling for many victims/survivors, but did not cover the costs of group support sessions or trips in the local area. |

4.3.2 Accommodation

Accommodation costs were capped at different levels for each delivery partner and accommodation type (for example, individual room versus ensuite). Some providers reported a cap of £80 per week, whereas for others it was as high as £250 (for ensuite rooms in high rent areas). The allowance increased in October to December 2021.

Emergency accommodation enabled victims/survivors to leave the perpetrator

Accommodation was one of the most valued parts of the Pilot by victims/survivors, who reported that access to the accommodation saved them from further physical or psychological harm and in many cases prevented them from becoming homeless. Many victims/survivors we interviewed entered the Pilot in a moment of crisis (for example, after an incident of severe physical abuse) or when they were homeless. Victims/survivors reported that once they had left the perpetrator, they had nowhere else to go because their families were not in the country, and many had been forced to socially isolate by the perpetrators. Because of these circumstances, emergency accommodation was an essential lifeline that helped victims/survivors in a moment of extreme vulnerability. Delivery partners were able to swiftly provide victims/survivors with accommodation in a moment of need. In some cases, victims/survivors were given access to emergency accommodation (for example, a hotel) and then relocated in shared accommodation with others in the longer term. The accommodation was provided entirely through the Pilot.

Victims/survivors were hosted in a range of accommodation types as delivery partners could not always accommodate victims/survivors in dedicated refuges

Delivery partners felt refuges would be the ideal place to host beneficiaries as they are situated in safe locations and offer a range of wrap-around services for guests such as childcare. However, this was not possible within the Pilot accommodation budget.

“We couldn’t afford our own refuges if you see what I mean, because the money was so under. We tried to find accommodation for £80 a week, it didn’t happen.”

[Caseworker]

“We couldn’t refer a woman to any refuges in [this city], which I think is the biggest issue that we’ve had. Although this may have also been because we had limited time [Pilot duration]. The wrap-around support that they could get in refuge would be ideal, let alone the main thing is, they would be safe. The accommodation we’re currently providing for women isn’t safe emergency accommodation. It’s just supported accommodation, which is just supported accommodation for homeless people.”

[Pilot Manager]

Instead, delivery partners met the accommodation needs of victims/survivors through a diverse range of accommodation arrangements, which included:

- vetted hotels and B&B: some victims/survivors were placed in vetted B&Bs or hotels; these were identified to be in secure locations, and many were already in use by social services; other victims/survivors were brought to an emergency hotel the first few nights and then relocated to another long-term facility

- shared housing with other victims/survivors: many victims/survivors lived in shared housing with other survivors (between 4 and 10 individuals) who also had NRPF; they typically had independent bedrooms and shared living spaces

- independent rentals: some victims/survivors lived in their independent accommodation which was paid directly by the Pilot

- supported accommodation: some victims/survivors were hosted in supported accommodation; these accommodations are designed to support people in need facing homelessness or substance abuse, rather than those experiencing domestic abuse

Delivery partners faced barriers in providing adequate accommodation because of issues in the amount, timeliness, and duration of funding

Delivery partners identified the primary reason for not placing victims/survivors in refuges as cost, as refuges could cost more than the accommodation stipend within the Pilot. However, they also reported that the structure of accommodation payments created barriers to obtaining adequate accommodation. Specifically:

- some accommodation providers were unwilling to take-on victims/survivors because they were unclear on how funding would be met after 12 weeks

- there were delays receiving the funding to cover accommodation costs from the Home Office, meaning that delivery partners had to self-fund in the interim

Even when accommodation costs could be met, some accommodation providers were reluctant to take victims/survivors in because the funding was only guaranteed for 12 weeks. Accommodation providers worried that they would be responsible for the victims/survivors after this point, but without any access to the funding to meet that responsibility:

“When we’re asking refuges or emergency accommodation, temporary accommodation, to take these women in, but saying, ‘For 12 weeks, we can pay you X amount of money,’ so the very first question they’re all saying is, ‘What happens after the 12 weeks?’”

[Programme Manager]

In addition, delivery partner staff flagged delays in receiving the funding from the Home Office to cover accommodation costs. For instance, towards the end of quarter 4 (January to March 2022), the delivery partners still had not received the funding to cover quarter 3 (October to December 2021). In the focus groups, delivery partners reported that delays in funding made it challenging to build a trusted relationship with accommodation providers:

“The other thing as well, is the time that you have to wait to actually receive the funding. Here we are, and we’re almost due to put in quarter 4, but we haven’t had quarter 3’s money yet. So, when we’re going back to refuges each quarter, or the other temporary accommodation providers. And they will say: ‘Well, you still haven’t paid me for…’ I don’t know if you are still waiting for your money from quarter 3, but it’s taking a lot of time to come through.”

[Caseworker]

The quality of the accommodation provided varied from good to very poor

While all victims/survivors were grateful for the accommodation and felt it enabled them to leave the perpetrator, there were high levels of variation in the quality of provision: some victims/survivors had overwhelmingly positive experiences, whereas others reported a number of issues.

Positive experiences

Many victims/survivors had very positive reviews of accommodation. Some living in shared housing or in vetted hotels and B&Bs felt that the accommodation was clean and spacious and had all the needed amenities. Many emphasised they valued having their own independent bedroom with their own privacy, and how they felt safe and supported in a women-only environment. In addition, victims/survivors generally felt that they were relocated to areas far from the perpetrators where they felt safe, this contributed to their wellbeing outcomes:

“I had my own room with a little bathroom and my own privacy where you can take back your mind and meditate again.”

[Victim/survivor]

“Everything was very comfortable. We had a very big kitchen which we share but in my room I have my bathroom.”

[Victim/survivor]

Negative experiences

Others that lived in shared housing, vetted hotels or B&Bs sometimes reported negative experiences. Key issues identified by interviewees included:

- lack of functioning amenities: some accommodation did not have basic amenities such as a working fridge, a stove or hot water; as put by one victim/survivor: “It’s okay but the fridge doesn’t work, it gets - it doesn’t get the power; the food gets rotten or food gets bad. The microwave doesn’t work. The cooker is also a bit broken”

- unhygienic living conditions: both victims/survivors and caseworkers reported that some accommodation was “filthy and full of rats”

- lack of understanding of victims/survivors situations: for some of those staying in commercial properties, such as B&Bs, issues arose when the accommodation providers did not understand the vulnerability of the victims/survivors they hosted; for example, one caseworker reported that a victim/survivor was asked to leave the accommodation because it was a particularly busy weekend, and the accommodation thought it could profit more from tourists

- experiences of discrimination from the local community: caseworkers reported that some accommodation facilities were situated in monocultural white British communities where victims/survivors faced discrimination and overt racism

- neighbours that may make victims/survivors feel unsafe: victims/survivors and caseworkers felt supported accommodation, in particular, was not suitable as it was designed to host homeless guests who are often male and suffered from alcohol or substance abuse issues

“The police took her to the hostel in [the location], and she wasn’t feeling comfortable there because there’s other, you know, alcoholic or drug difficulty there. We supported to move her from that hostel to the refuge place, which just has women there and just for other people including her.”

[Interpreter translating for victim/survivor]

4.3.3 Subsistence payments

Victims/survivors received a subsistence payment of £40 per week through the Pilot. In January 2022, this was increased to £50 per week.

Subsistence payments provided an important lifeline for victims/survivors

Victims/survivors highlighted that subsistence payments were crucial to their wellbeing and independence, and helped them cover basic needs such as:

- food: cash payments enabled recipients to buy food and cook their own meals; as well as being a basic need, this gave victims/survivors a sense of agency and independence, and positively impacted their wellbeing; some victims/survivors were able to cook recipes from their home country, which was a comfort to them

- toiletries: cash payments enabled recipients to purchase toiletries; those living with other peers would often pool their funds together to be able to afford necessities to meet their needs, such as buying menstrual products

- clothing: victims/survivors and their children had limited clothing and lacked basic items such as jackets or school uniforms for children as, in many instances, these items had to be left at the perpetrators’ homes, leaving victims/survivors without possessions

- transport: victims/survivors used transport to get to and from appointments, access shops and wellbeing support, and to stay connected with peers and networks

Having access to these basic needs enabled victims/survivors to leave the perpetrators and develop a sense of independence. Because of this, some highlighted subsistence payments as an aspect of the Pilot which was most beneficial to them:

“Yes, because I have the money now. Everything’s okay.”

[Victim/survivor]

“It’s a godsend because I was sitting there, about to be destitute, and you guys come in with a very nice lifeline, and I’m very grateful as well. It really helped with living expenses.”

[Victim/survivor]

There was some variation in both the amount of subsistence which victims/survivors received and the regularity of payments

In general, subsistence payments began soon after victims/survivors entered the Pilot. Victims/survivors mostly received payments in weekly instalments which were paid into their bank accounts. However, there was some variation in victims’/survivors’ receipt of subsistence payments: for example, one victim/survivor reported she had to wait 20 days from the point of leaving the perpetrator to her first payment. She then received £150 and another £450, 4 weeks later. Though the implications of the payment delays were not explicitly discussed, she said that she had needed to be very careful with money and relied on in-kind support and shop vouchers provided by the delivery partner for basic necessities such as food and toiletries:

“Since she left her marital house, and when she was about to live in the refugee house, not when she was in hostel, because…she was about 2 weeks in a hostel in [the location], then she moved to that refugee place. About 20 days after all in total, when she left her marital house, she received £150.”

[Interpreter translating for victim/survivor]

While the amount provided by the Pilot was consistent for all victims/survivors (£40 per week at first, and then £50 per week from January 2022), participants reported receiving subsistence payments which ranged between £40 per week to £60 per week, suggesting some discretion or subsidy by delivery partners. Subsistence payments also varied in delivery, with some being paid into bank accounts and others being paid via credit cards. In some cases, payments were also supplemented by shop vouchers, though this also appeared to be at the discretion of delivery partners. Victims/survivors expressed a preference for direct payments rather than vouchers, as this gave them agency over their expenditures:

“She found that because she is [short of] money, the voucher doesn’t give her the option to choose where she wants to use this money. She said she would prefer to have actual money rather than a voucher, then she can decide where she can use it. When she left her husband, she didn’t take much clothes and her personal things with herself. Now she’s quite, you know, it’s narrow for her where she’s able to use that money for.”

[Interpreter translating for victim/survivor]

Although subsistence payments provided an important lifeline, they were insufficient to cover basic needs victims/survivors

Despite being considered a vital lifeline, victims/survivors reported that subsistence payments did not comprehensively cover their basic needs, even after payments had increased to £50. The payments only partially covered food and toiletries, and other basic necessities such as clothing and essential transport were unaffordable to them. This problem affected those with children in particular, and was further aggravated by rising prices during 2022:

“I cannot do the travelling in this as well if I want to afford the tickets, I cannot, for bus tickets I cannot pay them.”

[Victim/survivor]

Victims/survivors who started receiving Universal Credit claimed that they were less concerned about their finances. They felt the Universal Credit was enough to cover all their basic needs without having to supplement it with in-kind support. Some also reported that since receiving Universal Credit, they valued gaining more autonomy over their expenditures by managing their own bills or paying their TV licence. As put by one of the victims/survivors who transitioned from Universal Credit from the subsistence payments:

“Money is better than before [now she is receiving Universal Credit], for sure.”

[Victim/survivor]

Some victims/survivors experienced periods during which they received no financial support because of delays in transitioning to other forms of support

While some victims/survivors received subsistence payments up to the point they started receiving other entitlements such as Universal Credit, others reported a time gap before receiving support. These gaps were due to delays and system errors in receiving entitlements. During this time, victims/survivors received no formal financial support and were dependent on the goodwill of delivery partners, peers in their accommodation, and charitable donations.

Case study - Delays in transitioning to Universal Credit leave victims/survivors without financial support

Shiza* came to the UK on a Spouse Visa. Though she has no children, she still struggled to manage on the £40-a-week subsistence payments provided and often had to visit the foodbank. Soon after entering the Pilot, she made an application for DDVC which should have been approved within 6 weeks. However, because of a system error and missing documents, her DDVC application and access to benefits was delayed. After 12 weeks, the subsistence payments stopped even though she was not yet receiving Universal Credit. For almost 2 months she had no financial support and she survived because other women in her accommodation shared their food with her - “even if it was just plain rice”. After waiting for 2 months, she finally started receiving Universal Credit and can now afford to pay for most of her basic needs.

*Case studies have been anonymised to protect the identities of victims/survivors.

In some cases, victims/survivors or caseworkers expected to transition to other forms of support within a given timeframe (for example, 6 weeks for those with DDVC), but unexpected delays in receiving these entitlements meant that the victims/survivors were left without income. Caseworkers felt that it was difficult to prepare for these unexpected errors and delays, and because of this, victims/survivors felt there had to be more flexibility in the duration of the financial support to ensure there was a smooth transition into receiving entitlements:

“I think the fund thing, we get it for 6 weeks, but some of the ladies, they don’t get their Universal Credit paid for nearly 8 weeks. Mine started off I think after 7 weeks, so obviously for one week I didn’t have anything. She did speak to the manager as well, and they said they can’t really do anything. I think they could do £40 at least until the start of Universal Credit.”

[Victim/survivor]

4.3.4 In-kind support

Delivery partners used in-kind support to provide for victims’/survivors’ basic needs which could not always be met by subsistence payments

Due to insufficient subsistence payments, delivery partners addressed a range of the victims’/survivors’ needs by sourcing in-kind support through their internal resources or through other voluntary organisations. Some victims/survivors relied on in-kind support such as food banks, vouchers, and charitable donations to access these items. In the focus groups, Pilot managers universally said that they had partnerships with food banks, as well as a range of other local charities. While these services were for victims/survivors both on the Pilot and otherwise supported by the delivery partner, Pilot participants sometimes received priority because their need was greater than those with recourse to public funds. Caseworkers and their clients stressed that supplementing needs with in-kind support was key to addressing victims’/survivors’ basic needs because of the insufficient amount received:

“Women’s Aid help us to link the food bank, yes, and give me food bank support. Also during every holiday, Christmas, they give me some voucher for food and a lot of children’s gifts, and a lot of whatever we need, just the daily clothes and that.”

[Victim/survivor]

Victims/survivors needed access to transport and digital devices to access their entitlements

The findings suggest that subsistence payments were insufficient to cover the costs of essential travel and access to digital devices. Victims/survivors needed to travel to progress their immigration applications (for example, provide biometrics) or family legal disputes. Many victims/survivors were living outside urban centres and could not afford trains to reach their destinations.

The findings also revealed how smartphones were often a necessity that enabled victims/survivors to receive entitlements and become independent of the Pilot. For example, victims/survivors required a bank account in order to receive the subsistence payments and Universal Credit. However, high street banks do not take clients without a settled immigration status. Instead, delivery partners used e-banking providers such as Monzo, which require users to download a dedicated app on a personal device. Victims/survivors mentioned in the interviews how they valued having access to their personal bank account:

“Benefits, yes, yes, yes, yes. They gave me [Delivery partner helped victim/survivor to open] bank [account]. Yes, yes, bank. We have open bank. That is my first time, then I have the bank account.”

[Victim/survivor]

4.3.5 Caseworkers

Victims/survivors attributed a range of positive outcomes to the guidance provided by their caseworker

Victims/survivors were supported through their journey by a dedicated caseworker, who provided them with a range of support. This included emotional support, bureaucratic and legal support, and sign-posting victims/survivors to other sources of support. Across the board caseworkers were deemed invaluable by victims/survivors - and one of the most highly valued aspects of the Pilot. According to victims/survivors, caseworkers played an important role in improving their wellbeing outcomes, independence outcomes and helping them to understand their immigration choices.

Emotional support through trusted relationships