Estimating the economic and social value of volunteering

Published 11 July 2025

Applies to England

1. Estimating the economic and social value of volunteering

About London Economics

London Economics is one of Europe’s leading specialist economics and policy consultancies headquartered in London. We advise clients in both the public and private sectors on economic and financial analysis, policy development and evaluation, business strategy, and regulatory and competition policy.

Our consultants are highly-qualified economists with experience in applying a wide variety of analytical techniques to assist our work, including cost-benefit analysis, multi-criteria analysis, policy simulation, scenario building, statistical analysis and mathematical modelling. We are also experienced in using a wide range of data collection techniques including literature reviews, survey questionnaires, interviews and focus groups.

Head Office:

Somerset House, New Wing

Strand

London

WC2R 1LA

United Kingdom

+44 (0)20 3701 7700

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the useful guidance and feedback provided by the DCMS team, Basis Social and NPC. We would like to thank all those who participated in the practitioner group and advisory group for their helpful comments when devising the methodology for this report. Responsibility for the contents of this report remains with London Economics.

Authors

-

James Cannings, Senior Economic Consultant, jcannings@londoneconomics.co.uk

-

Ella Lingard, Economic Consultant, elingard@londoneconomics.co.uk

-

Moritz Profanter, Economic Consultant, mprofanter@londoneconomics.co.uk

-

Pietro Patrignani, Principal Consultant, ppatrignani@londoneconomics.co.uk

-

Dr Gavan Conlon, Partner, gconlon@londoneconomics.co.uk

2. Executive Summary

The Department for Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) commissioned London Economics, working with Basis Social and New Philanthropy Capital (NPC) to monetise the economic and social value of volunteering in England. The work implements a methodology developed for DCMS by combining desk research and stakeholder workshops with academics, local government officials, funders, and voluntary, community, and social enterprise (VCSE) organisations.

This report examines the benefits of adult formal volunteering, which refers to giving unpaid help to groups or clubs by individuals aged 16 and over and aligns with the DCMS’s Community Life Survey (CLS) definition. The report estimates the monetary value of formal volunteering activity in England in 2021/22. During that period, approximately 12 million people formally volunteered at least once.

The report examines 5 strands of the value of volunteering:

-

The replacement cost of volunteering, which values the benefits of volunteering by valuing the cost of replacing volunteers with paid staff.

-

The wellbeing benefits to volunteers, which values the benefits of life satisfaction improvements for volunteers as a result of volunteering.

-

The effect of volunteering on employment outcomes, which examines the effect of volunteering on the hourly pay, hours worked and the probability of paid employment of volunteers.

-

The effect of volunteering on healthcare costs, which examines the effect of volunteering on the number of healthcare appointments (GP, outpatient and inpatient) of volunteers.

-

The effect of volunteering on social outcomes, which examines the effect of volunteering on a range of social outcomes of volunteers, such as isolation, loneliness, and belonging to a neighbourhood.

We provided monetary estimates for the first two strands (replacement cost and wellbeing benefits), but we could not provide monetary estimates for other strands, as we did not identify robust statistical relationships between volunteering and those outcomes. Instead, we present results from our econometric analysis for those strands.

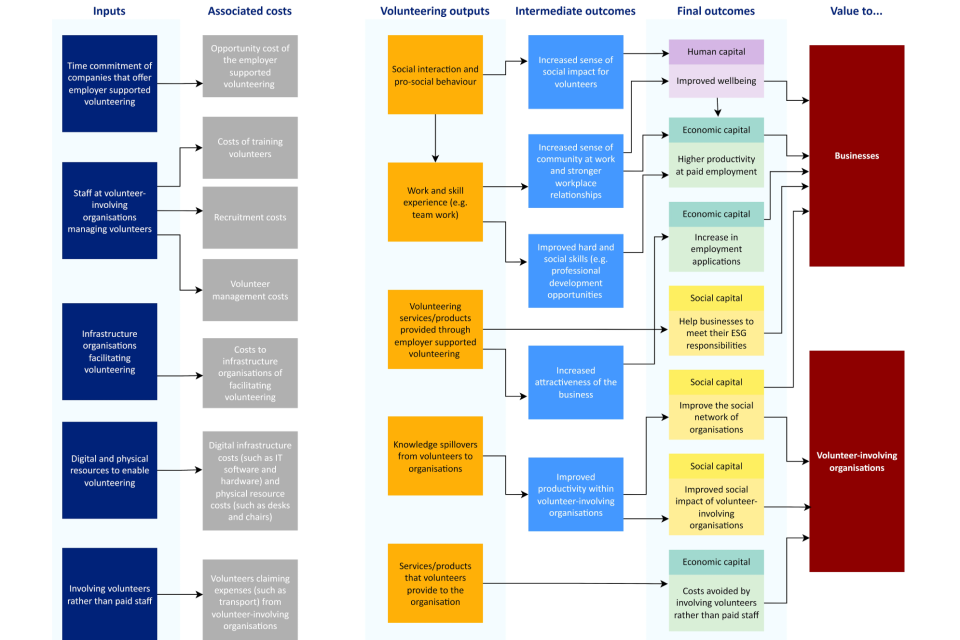

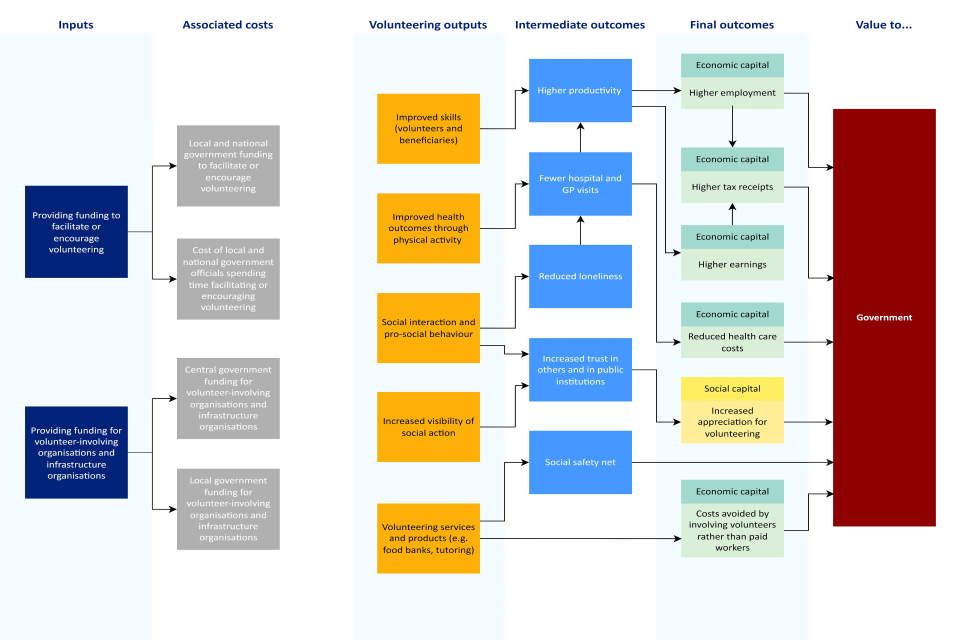

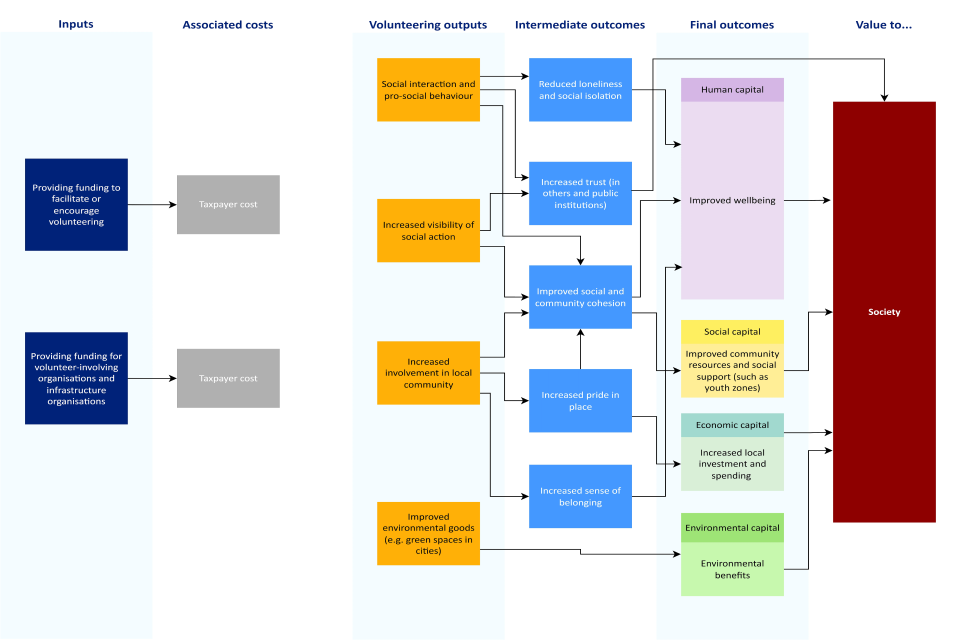

In addition to the above strands, there are many benefits that, while just as important as those included in this analysis, could not be included due to data limitations. These benefits are included in a conceptual framework that was developed as part of the methodology for this work and are shown in Annex A1.1.3.

The total economic impact of formal volunteering activity in England in 2021/22, based on the replacement cost and wellbeing benefits of volunteering, was estimated at £24.69 billion.[footnote 1] This represents an average economic impact of £2,012 per volunteer. The other main results from the report are as follows:

-

The cost of replacing volunteers with paid staff in England in 2021/22 (the replacement cost) was estimated at £16.43 billion.

-

The value for the replacement cost of volunteering was driven predominantly by the most frequent volunteers (those who volunteered at least once a week), with 63% of the total impact originating from that group. This result highlights the importance of retaining the most frequent volunteers, and encouraging more frequent volunteering, to maximise the impact of volunteers.

-

The replacement cost of formal volunteering in 2021/22 was equivalent to £1,339 per volunteer.

-

The monetised value of the wellbeing benefits experienced by volunteers in England in 2021/22 was estimated at £8.26 billion.

-

This wellbeing benefit was equivalent to £673 per volunteer.

-

Volunteering at least once a year leads to a 0.033-unit increase in volunteers’ life satisfaction on a 1 to 7-point scale. This effect is largest for those who volunteer at least once a month but less than once a week (a 0.061-unit increase).

-

We identified limited evidence to suggest that volunteering increases the likelihood of paid employment one year after becoming a volunteer, but it has a positive impact on employment two and three years after becoming a volunteer. We found a positive effect on employment for those aged 16 to 25, but a negative for those aged 46 to 65. These results suggest that volunteering may act as a pathway to work, particularly for younger people, although our analysis does not identify specific factors that would cause this employment effect (such as building skills).

-

Volunteering in the last 12 months is associated with 1.2% lower pay than non-volunteers in the following year. This effect is strongest for those who volunteer at least once a week, as this is associated with a 2.8% lower hourly pay in the next year, compared to non-volunteers. However, the effect does not persist over time, except for those who volunteer at least once a week. In addition, this effect may not be causal, as external factors may both increase volunteering incidence and affect individuals having lower hourly pay, such as an increase in a partner’s wages.

-

We identified weak evidence that volunteering leads to a small decrease in the number of hours worked by volunteers in paid employment (by around 8 minutes per week), but only for volunteers over the age of 25. Those aged under 25 work for more hours after volunteering, which suggests that volunteering may complement paid work for younger people but act as a substitute for paid work for older people (albeit to a limited extent).

-

We examined the impact of volunteering on the number of healthcare appointments for volunteers to understand how their improved health outcomes could decrease government healthcare costs. We identified weak evidence to suggest that volunteering leads to a small decrease in the number of days spent by volunteers as an inpatient, but there was limited evidence to suggest that volunteering affects the number of GP appointments or outpatient visits of volunteers.

-

Volunteers are 2.4 percentage points more likely than non-volunteers to agree that they feel a sense of belonging to their neighbourhood and are 10.4 percentage points more likely to express a willingness to improve their neighbourhood. However, these results cannot be treated as a causal effect, as these factors may also cause individuals to start volunteering.

-

There is very weak evidence to suggest that volunteers are more likely to report feeling isolated, having a lack of companionship, feeling left out or feeling lonely than non-volunteers.

3. Introduction

The Department for Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) commissioned London Economics, working with Basis Social and New Philanthropy Capital (NPC), to monetise the economic and social value of volunteering in England. The work forms part of a wider programme of volunteering research commissioned by DCMS, which is designed to strengthen the evidence base around volunteering. This report aims to examine the value generated by formal volunteering activity in 2021/22, matching that year’s Community Life Survey (see Section 4 for more details).

This work implements a methodology developed for DCMS using a combination of desk research and stakeholder workshops with academics and practitioners (local government officials, funders, and voluntary, community and social enterprise organisations). While the initial methodology developed considered both the benefits and costs of volunteering, this report only considers the benefits of volunteering due to the difficulty of accurately capturing the costs of volunteering. In addition, there are many benefits that, while just as important as those included in this analysis, could not be included due to data limitations. These benefits, alongside a conceptual framework, further information on the development of the methodology, and the reasons for excluding some benefits and costs, can be found in Annex 1.

The methodology used here is designed to be general, focusing on adult formal volunteering activity in England.[footnote 2] ‘Adult formal volunteering’ refers to ‘the giving of unpaid help to groups or clubs by those aged 16 and over’, aligning with the definition used in DCMS’s Community Life Survey (DCMS, 2023). The scope is limited to adult formal volunteering activity as formal volunteering is the type of volunteering activity that DCMS has primarily supported through its funding activities in recent years. The restriction of the analysis to adult volunteering is a result of data availability.

DCMS commissioned this report to be able to articulate the value generated by volunteers in monetary terms across a wide range of dimensions, including wellbeing, following HM Treasury’s 2021 Green Book update on guidance for wellbeing appraisal (HM Treasury, 2022). The work is intended to make the case for investment in volunteering that is linked to other policy objectives, and in a way that achieves the needs of local communities.

While the methodological framework used here focuses on England, we see this as a starting point to comprehensively capture the value of volunteering across more outcomes than in previous valuations of volunteering (such as the inclusion of wellbeing and employment outcomes). We anticipate that the methods and derived parameters could be used to analyse the impact of specific volunteering programmes or to provide more local-level estimates of the value of volunteering. There were also parts of the methodology that were developed but not implemented in this analysis. We describe these methodologies in Annex A1.2 and Annex A1.4 to allow these proposed approaches to be adopted in other studies.

While previous studies have examined some of the strands considered in this work, generally speaking, they are neither up to date, nor have they considered the wider range of potential sources of value incorporated into this study. We have not identified any previous study in the UK that has considered as wide a range of sources of value as examined in this work.[footnote 3]

The total economic and social value of volunteering presented here can be considered an underestimate relative to the full range of benefits from volunteering. We were unable to monetise some strands of analysis, due to the econometric results not being sufficiently robust.[footnote 4] In some cases, this could be due to potential effect sizes being small, which makes it difficult to draw robust conclusions.

The report is based on 2021/22 volunteering data, where formal volunteering levels were lower than in previous years. While these figures may have been impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic and associated guidance introduced in the UK, it should be noted that the latest 2023/24 data suggests that formal volunteering levels have not increased since the pandemic.

In this report, we outline the key data sources used in Section 4, then detail our econometric strategy in Section 5.

This report then considers the economic and social value of volunteering across 5 strands:

-

The replacement cost of volunteering, which values the labour value of volunteering by estimating the cost (to volunteer-involving organisations) of replacing volunteers with paid staff Section 6.

-

The wellbeing benefits to volunteers, which values the benefits of life satisfaction improvements for volunteers as a result of volunteering Section 8.

-

The effect of volunteering on employment outcomes, which examines the effect of volunteering on the hourly pay, hours worked and the probability of paid employment of volunteers Section 6.

-

The effect of volunteering on healthcare costs, which considers the effect of volunteering on the number of healthcare appointments (GP, outpatient and inpatient) of volunteers Section 9.

-

The effect of volunteering on social outcomes, which examines the effect of volunteering on a range of social outcomes of volunteers, such as isolation, loneliness, and the sense of belonging to a neighbourhood Section 10.

We then present the total value of volunteering of the monetised outcomes (replacement cost and wellbeing benefits) in Section 11.

4. Key data sources

Across our methodologies, we use two key secondary data sources: the Community Life Survey and Understanding Society, which are described below. Additional secondary data sources (for example, ONS mid-year population estimates) were used to monetise elements of the proposed methodology and are described further in the relevant sections.

4.1 Community Life Survey

The Community Life Survey is a representative survey of adults aged 16 or above in England, run regularly by DCMS.[footnote 5] At the time of analysis, the most recently published wave provided data from October 2021 to September 2022.[footnote 6] The survey provides information on the type and frequency of volunteering.[footnote 7] We used the following data in our analysis:

-

Frequency of formal volunteering in the last 12 months (at least once a week; less than once a week but at least once a month; less than once a month).

-

Type of formal volunteering activity (within the last 12 months).[footnote 8]

-

Number of hours volunteered formally within the last four weeks.[footnote 9]

It is important to note that formal volunteering incidence was lower than in previous years in the 2021/22 survey. While these figures may have been impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic and associated guidance introduced in the UK, it should be noted that the latest 2023/24 data suggests that formal volunteering levels have not increased since the pandemic.

4.2 Understanding Society

Understanding Society is the largest household longitudinal survey in the UK, conducted with a sample of around 40,000 households.[footnote 10] It has run since 2009, and combined with its predecessor, the British Household Panel Survey (BHPS), provides yearly data since 1991. It provides data on the incidence and frequency of volunteering and the number of hours formally volunteered by adults (aged 16 and over) in the last 12 months. At the time of this analysis, the most recent data on volunteering was available from 2018-2020 (wave 10),[footnote 11] but data on other variables is available in subsequent waves, up to wave 13 (2021-2023). It asks questions about:

-

Whether individuals have formally volunteered in the last 12 months.[footnote 12]

-

Frequency of formal volunteering in the last 12 months.

Data on these volunteering variables was collected in the following years: 2010-12 (wave 2), 2012-14 (wave 4), 2014-16 (wave 6), 2016-18 (wave 8) and 2018-20 (wave 10).

Alongside volunteering data, the survey provides detailed information on the social and economic characteristics of respondents, such as life satisfaction, health, and income. Its longitudinal design, which follows the same individuals over time, allows for an analysis of how each individual’s outcomes change over time. The longitudinal design, combined with volunteering and outcome data, has been used frequently within the academic literature to estimate the effect of volunteering on outcomes, such as life satisfaction (Lawton and others, 2021), mental wellbeing (Tabassum and others, 2016) and employment outcomes (Paine and others, 2013; Wilson and others, 2020). The consistent use of Understanding Society in peer-reviewed articles to estimate the impact of volunteering indicates its reliability for producing robust estimates.

5. Econometric strategy

We used Understanding Society to derive parameters to estimate the impact of volunteering on:

-

Wellbeing improvements of volunteers.

-

Employment outcomes of volunteers.

-

Healthcare costs of volunteers for the government.

-

Social outcomes of volunteers.

The outcome variables used are shown in Table 1.

Our analysis estimated the impact of volunteering based on two volunteering variables available in Understanding Society:

-

Incidence of volunteering: whether individuals volunteered in the past 12 months.

-

Frequency of volunteering: how often individuals volunteered in the past 12 months.[footnote 13]

Where possible, we used volunteering data from five waves of Understanding Society.[footnote 14]

Table 1: Understanding Society variables used in the econometric analysis

| Outcome | Understanding Society variable(s) |

|---|---|

| Wellbeing improvements for volunteers | Satisfaction with life overall (1-to-7-point scale) |

| Improved employment outcomes for volunteers | Paid employment status, Hourly pay, Weekly hours worked, Total gross personal monthly labour income |

| Reduced healthcare costs for the government and individuals[footnote 15] | Number of times visiting a GP in the last 12 months, Number of times attending a hospital or clinic as an outpatient in the last 12 months, Number of days as an inpatient in the last 12 months |

| Individual social benefits for volunteers[footnote 16] | Feeling of belonging to the neighbourhood, Willingness to improve the neighbourhood, Social isolation, Lack of companionship, Feeling left out, Feeling lonely |

Note: Variables are available in all waves of Understanding Society unless otherwise specified.

Source: London Economics’ analysis of Understanding Society

5.1 Addressing selection bias

To estimate the value of volunteering using survey data, the main issue that needs to be overcome relates to selection bias. Individuals volunteer for a reason and therefore volunteers potentially differ from non-volunteers in terms of their personal or socioeconomic characteristics. For example, simply comparing the wellbeing outcomes of volunteers to non-volunteers would yield a biased outcome. The reason for this is that individuals who choose to volunteer may have had higher wellbeing than non-volunteers, even if they had chosen not to volunteer.[footnote 17] In other words, higher wellbeing may increase the probability of becoming a volunteer (Stuart and others, 2020).

To address this, we used fixed effects estimation[footnote 18] through the incorporation of control variables to overcome this selection bias issue. This approach is in line with previous literature (for example, Lawton and others, 2021; Wilson and others, 2020). Fixed effects estimation overcomes selection issues by controlling for time-invariant individual characteristics, reducing bias from unobservable characteristics that affect both the decision to volunteer, and the measured outcomes that are likely to be inherent personal characteristics (for example, altruism) that do not change over time. There may still be time-variant factors that bias our estimates (specifically, any time-variant factors that correlate with the probability of volunteering and the outcomes of volunteering) that we are unable to control for. However, the rich dataset of time-varying control variables within Understanding Society should minimise this issue. When presenting the results of the analysis, we highlight where the results may be driven by this shortcoming of fixed effects estimation.

5.2 Estimation equations

We used two estimation equations for each type of volunteering variable (incidence and frequency), depending on whether we estimated the effect of volunteering at time t or time t-1 on outcome variables at time t.[footnote 19]

For wellbeing and social outcomes, we estimated the effect of volunteering at time t on outcomes at time t, as these benefits are expected to be immediate. For these outcomes, we used estimation equation (1) for volunteering incidence and (2) for volunteering frequency:

-

yᵢₜ = αᵢ + β₁Vᵢₜ + β₂Xᵢₜ + εᵢₜ

-

yᵢₜ = αᵢ + β₁Wᵢₜ + β₂Xᵢₜ + εᵢₜ

Where:

-

yᵢₜ represents the outcome at time t (for example, wellbeing, social benefits)

-

αᵢ represents time-invariant individual-specific characteristics that affect the outcome

-

Vᵢₜ represents whether an individual formally volunteers at time t (volunteering incidence)

-

Wᵢₜ represents the frequency of volunteering at time t, with four categories:

* 0, has not volunteered in the last 12 months

* 1, has volunteered less than once a month in the last 12 months

* 2, has volunteered less than once a week but at least once a month in the last 12 months

* 3, has volunteered at least once a week in the last 12 months

- Xᵢₜ represents a vector of time-varying factors at time t that affect the outcome ( ).[footnote 20]

For employment and healthcare outcomes, we analysed the effect of volunteering at time t-1 on outcomes at time t, reflecting the potential delayed effects of volunteering on these measures. For this analysis, we used estimation equations (3) and (4):

-

yᵢₜ = αᵢ + β₁Vᵢ₍ₜ₋₁₎ + β₂Xᵢₜ + εᵢₜ

-

yᵢₜ = αᵢ + β₁Wᵢ₍ₜ₋₁₎ + β₂Xᵢₜ + εᵢₜ

Where:

-

yᵢₜ represents the outcome at time t (for example, wages, number of GP appointments)

-

Vᵢ₍ₜ₋₁₎ represents whether an individual formally volunteers at time t-1

-

Wᵢ₍ₜ₋₁₎ represents the frequency of volunteering at time t-1

The control variables used in the regressions are provided in Annex A1.9.1.

5.3 Econometric models

The type of econometric model used[footnote 21] in our analysis varied depending on the nature of the outcome variable:

-

For binary outcome variables (for example, employment status), we used a fixed effects logistic model.[footnote 22]

-

For ordinal outcome variables (for example, GP appointments, and outpatient visits), we used fixed effects ordered logistic models.[footnote 23][footnote 24]

-

For all other outcome variables (for example, wellbeing, wages, hours worked, and inpatient days), we used fixed effects models.

As a result, the interpretation of the regression coefficients varies across outcome variables. The interpretations are explained in the relevant sections.

We applied a range of econometric specifications in addition to the main specifications, including ordinary least squares (OLS) models. We conducted additional robustness checks by examining the effect of volunteering at time t-2 and t-3, on employment and healthcare outcomes at time t. We also explored whether the impact of volunteering varied across different age groups. For wellbeing, since we focus on the effect of volunteering at time t on wellbeing at time t (due to the immediate nature of the benefits), we applied a first-difference estimation to assess the change in wellbeing based on changes in volunteering status between time t-2 and time t.[footnote 25] These additional results are provided in Annex A1.9.

6. Replacement cost of volunteering

One important element of the economic value of volunteering is the value of the activities undertaken by volunteers. In previous literature (for example, International Labour Organization (ILO) Department of Statistics, 2021; Nesta, 2020; Office for National Statistics, 2013), the replacement cost method has been used to value the labour cost of volunteering. This method considers the cost that volunteer-involving organisations would incur to replace volunteers with paid staff to maintain the provision of their services.

In other words, the replacement cost method takes an ‘input’ approach, viewing volunteers’ activities as a benefit to VIOs by calculating the labour costs avoided by involving volunteers instead of paid staff. While this approach is also applied here, the replacement cost can also be considered as a proxy for the added value of the ‘output’ of volunteering activities. In other words, the replacement cost method estimates the added value of the services provided by volunteers by estimating the value of the labour used to produce these outputs.[footnote 26] The assumptions and limitations implied by this method are discussed in more detail in Section 6.2.

6.1 Methodology

The replacement cost method assumes a counterfactual where volunteers are absent and VIOs would need to employ paid staff to maintain the provision of their services. The approach values volunteer hours by considering the market wage rate that would be required to pay a given volunteer. We built upon the approach used by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) in the Household Satellite Accounts (Office for National Statistics, 2013), and more recently by Martin and Franklin (2022). Broadly, the approach identified the key activities undertaken by volunteers, which were matched to proxy wages associated with each activity. These wages were then multiplied by the estimated number of hours volunteered in each activity in 2021/22 to determine the replacement cost of volunteering in 2021/22.

Specifically, using a seven-step approach, we:

-

Assigned the 13 volunteering activity types from the 2021/22 Community Life Survey to proxy Standard Occupational Classification (SOC) 2020 occupations, based on an ONS mapping (Office for National Statistics, 2013).[footnote 27] The mapping is presented in Table 26 in Annex A1.7(#a17-replacement-cost-mapping).

-

Assigned a proxy wage to each volunteering activity type using annual median pay data by SOC occupation from the 2021 Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings (Office for National Statistics, 2024a).[footnote 28]

-

Estimated the share of volunteers associated with each proxy SOC occupation (based on volunteering activities) by volunteering frequency category using the 2021/22 Community Life Survey.

-

Estimated the number of volunteers in England in 2021/22 by frequency category, by multiplying the share of volunteers in each volunteering frequency category (as a share of all respondents) from the 2021/22 Community Life Survey by the population of England aged 16 and over in mid-2021 (Office for National Statistics, 2023).

-

Estimated the total number of hours volunteered within each volunteering frequency category in 2021/22, by initially multiplying the average number of hours volunteered in the last 4 weeks by frequency category[footnote 29] by the number of volunteers in England by frequency category (from step 4). This four-weekly figure was then converted to a yearly figure.

-

Estimated the total number of hours volunteered in each proxy SOC occupation (by frequency category), by multiplying the outputs from steps 3 and 5.

-

Estimated the total replacement cost of formal volunteering in 2021/22 by multiplying the output from step 6 by the associated proxy wage associated with each SOC occupation (from step 2) then aggregating across SOC occupations.

6.2 Assumptions and limitations

The replacement cost approach values volunteering from an economic perspective and implicitly assumes perfect substitutability between volunteers and paid staff. In other words, it assumes that replacing one full-time equivalent volunteer with one full-time equivalent paid staff member would result in the same outcomes. Whilst it provides a method to produce a monetary value of the work undertaken by volunteers, it may not align with how volunteers or VIOs view volunteering, as it can be seen as characterising volunteering as ‘free labour’. It can also lead to certain types of volunteering appearing more valuable than others because the market wage associated with those activities is higher. In addition, many in the VCSE sector would argue that volunteering is fundamentally different from paid work and therefore is not comparable. In future work, these limitations could be addressed by estimating a factor to adjust the replacement cost (for example, using primary data collection), but calculating such a factor has logistical and conceptual difficulties (see Annex A1.5 for further discussion).

Other limitations relate to the lack of granularity of volunteering activity data, meaning that relatively broad occupations are matched to each volunteering activity type, which may not fully reflect the nature of volunteering activities and the associated cost of replacing them. Additionally, the CLS only provides data on whether or not volunteers participate in certain activities, and the overall frequency of volunteering, but does not provide data specifically on the frequency of volunteering in each activity. Therefore, those volunteering across activity types are assumed to spend equal time in each activity type. Finally, we assume that there would be no general equilibrium effects (effects on market wages) if volunteers were replaced by paid staff. This assumption will hold at the margin, but if all volunteers were replaced by paid staff, the market wage would be likely to increase due to increased labour demand.

We also do not include any non-wage costs of employment, such as National Insurance or pension contributions. While these costs would be relevant if an organisation decided to replace volunteers with paid staff, they are not relevant in valuing the activities undertaken by volunteers.

6.3 Monetisation results

We estimated that the total replacement cost of volunteers in England in 2021/22 stood at £16.433 billion.[footnote 30] This represents the labour costs that VIOs avoided by involving volunteers rather than paid staff. In other words, in the absence of volunteers, VIOs would have needed to pay a total of £16.433 billion to staff to maintain the provision of volunteering outputs in England in 2021/22 (assuming no general equilibrium effects).

This result was driven predominantly by the most frequent volunteers (at least once a week), who accounted for around 63% of the impact (£10.276 billion), despite only making up around 30% of volunteers (see Annex A1.6 for the total number of volunteers and hours volunteered). This was because they contributed around 2.4 times the number of weekly hours of those who volunteered less than once a week but at least once a month, and 6.4 times the quantity of those who volunteered less often than once a month. Those volunteering less than once a week but at least once a month accounted for 26% of the total impact (£4.312 billion), with the least frequent volunteers (less than once a month) accounting for the remaining 11% of the impact (£1.846 billion).

The results would suggest the importance of retaining existing frequent volunteers and encouraging volunteers to volunteer more frequently, given the large contribution that they make to the overall economic value of volunteering.

The overall magnitude of the results is similar to those found in other studies. For example, in the Household Satellite Account, the Office for National Statistics estimated the value of organisation-based volunteering to the UK economy in 2022 to be £14.636 billion (Office for National Statistics, 2024d).

Table 2: Total replacement cost by volunteering frequency

| Volunteering frequency | Total hours volunteered in 2021/22 (A) | Average value of volunteering per hour (B) | Total replacement cost (A*B) |

|---|---|---|---|

| At least once a week | 766.7m | £13.40 | £10.276bn |

| Less than once a week but at least once a month | 327.6m | £13.16 | £4.312bn |

| Less often than once a month | 150.6m | £12.25 | £1.846bn |

| Total | 1,244.9m | £13.20 | £16.433bn |

Note: Totals may not add up due to rounding. The average value of volunteering per hour was calculated by dividing the total replacement cost in each volunteering frequency category by the corresponding number of hours volunteered.

Source: London Economics’ analysis of Community Life Survey, Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings and Office for National

We also estimated the average replacement cost per volunteer in each frequency category (see Table 3). These figures are obtained by dividing the total replacement cost by the number of volunteers in each frequency category. As with the overall results presented in Table 2, those volunteering at least once a week have, on average, the highest replacement cost (£2,746) compared to other frequency categories.

Table 3: Average replacement cost per volunteer by volunteering frequency

| Volunteering frequency | Average replacement cost per volunteer |

|---|---|

| At least once a week | £2,746 |

| Less than once a week but at least once a month | £1,131 |

| Less often than once a month | £391 |

| At least once in the past 12 months | £1,339 |

Note: Figures are rounded to the nearest pound. The estimate of the average replacement cost of those who volunteered at least once in the past 12 months (£1,339) represents the average across all formal volunteers in England in 2021/22.

Source: London Economics’ analysis of Community Life Survey, Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings and Office for National Statistics population data.

7. Wellbeing benefits to volunteers

Previous studies found that there was a positive relationship between volunteering and the wellbeing of volunteers (Lawton and others, 2021; Stuart and others, 2020). A number of other studies have identified a range of potential mechanisms for this effect, such as social interactions (Dolan and others, 2021), engagement in physical activity (for example, outdoor activities, sports), and improved health (Nichol and others, 2024).

While wellbeing can be defined in different ways (for example, subjective life satisfaction, mental and physical wellbeing), one common approach has been to use the subjective life satisfaction index as a proxy for wellbeing (Dolan and others 2021; Lawton and others 2021).[footnote 31] We used a life satisfaction index as a proxy for wellbeing, as it is recommended for wellbeing monetisation in the Green Book supplementary guidance on wellbeing (HM Treasury, 2022); is available in Understanding Society data; and can be monetised using ‘wellbeing adjusted life years’ (WELLBYs). The WELLBY value measures the monetary value of a one-unit improvement in self-reported life satisfaction (on a 0-10 scale) in one year (HM Treasury, 2022).

In this section, we only consider the impact of volunteering on the wellbeing of volunteers. The ‘beneficiaries’ of volunteering activities (or ‘service users’)[footnote 32] may also experience wellbeing improvements from volunteering. We discuss the reasoning behind their exclusion further in Annex A1.1.

7.1 Methodology to monetise the impact of volunteering on volunteer wellbeing

We monetised the impact of volunteering on wellbeing using the three inputs shown in Table 4.

Table 4: Wellbeing monetisation inputs

| Input | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|

| A | Impact of volunteering on life satisfaction | Estimates of the impact of volunteering on wellbeing from Understanding Society |

| B | Central value of a WELLBY in 2021 prices | Calculations based on HM Treasury (2022) guidance |

| C | Number of volunteers in England in 2021/22 | 2021/22 Community Life Survey and ONS population estimates |

| A*B*C | Total value of wellbeing benefits of volunteering in 2021/22 |

Source: London Economics’ analysis

This three-step monetisation method is used widely in the literature when estimating the impact of formal volunteering incidence on wellbeing.[footnote 33] We define volunteering incidence as having volunteered at least once in the last 12 months.

Step 1: Estimate the impact of volunteering on life satisfaction

We used Understanding Society to estimate the quantitative impact of volunteering incidence on wellbeing. Our econometric strategy to estimate these wellbeing impacts, and more information on the key variables used, is provided in more detail in Section 5.

We produced an estimate for the effect of volunteering incidence (having volunteered at least once in the past 12 months) and three different estimates for the impact of volunteering by frequency of volunteering activity.[footnote 34] The estimates represent the unit increase on a 1-to-7-point life satisfaction scale that is associated with volunteering incidence and volunteering frequency.[footnote 35] Our main estimates presented in this section are based on volunteering incidence, but we present the results and monetisation inputs for volunteering frequency in Table 27 in Annex A1.8.

Step 2: Adjust the central WELLBY value to 2021 prices and to a 1-to-7-point scale

According to Green Book supplementary guidance, the WELLBY value stood at £13,000 in 2019 prices. We converted this to 2021 prices using the following equation:[footnote 36]

Next, we multiplied the WELLBY value by 11/7 to convert the estimate from a 0-to-10 scale to a 1-to-7 scale, as recommended in the Green Book supplementary guidance (HM Treasury, 2022). This transformation was necessary because the life satisfaction variable used in the Understanding Society analysis is based on a 1-to-7 scale, while the WELLBY value is based on a 0-to-10 scale.

Step 3: Calculate the number of volunteers in England in 2021/22

Following the same approach as used in the replacement cost method (see Section 6, we estimated the number of volunteers using the 2021/22 CLS and 2021 ONS annual mid-year population statistics for individuals aged 16 years or above.

7.2 Econometric results

Following our econometric strategy from Section 5, we estimated the impact of volunteering on life satisfaction using Understanding Society. We also produced estimates of this impact for different age groups to show how the impact of volunteering on wellbeing differs by age. Table 5 presents the results from these regressions.

Estimating the impact of volunteering incidence on life satisfaction across all age groups produced a coefficient of 0.033 which is statistically significant at the 1% level (indicating a strong significance). This means that volunteering at least once in the past 12 months results in a 0.033-unit increase on a 1-to-7-point life satisfaction scale relative to those who do not volunteer.[footnote 37]

Our estimates by age suggest that volunteers aged between 45 to 65 experience the highest increases in wellbeing from volunteering (a 0.047-unit increase). The estimates for other age groups are not statistically significant, meaning there is not enough evidence to make a conclusive statement about the size of the wellbeing benefits of volunteering for these age groups. However, the coefficients are all positive, suggesting that the positive relationship between volunteering and life satisfaction may hold across age groups.

Considering the impact broken down by volunteering frequency, the impact of volunteering on life satisfaction was highest for those volunteering at least once a month but less than once a week (a 0.061-unit increase). This result is statistically significant at the 1% level and suggests that volunteering at this frequency may represent an ideal level of volunteering to achieve the highest wellbeing benefits. This effect also holds across almost all age groups, with the average impact of volunteering at least once a month but less than once a week on life satisfaction being the highest in most age groups compared to the other frequency categories. Volunteers aged over 65 are the only exception, where volunteering at least once a week has the highest wellbeing benefits (a 0.065-unit increase).

Based on these findings, it was appropriate to monetise the results. This was because the overall results for the impact of volunteering in the past 12 months were strongly significant, the positive effect held across age groups and alternative econometric specifications (see Annex A1.9), and the results aligned with other findings from the academic literature. For example, Lawton and others (2021) found an overall effect size of 0.041 using a similar methodology and older data, compared to the overall effect size of 0.033 identified here.

Table 5: Regression coefficients for the impact of volunteering on life satisfaction

| All ages | Aged 16–25 | Aged 26–45 | Aged 46–65 | Aged over 65 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Volunteering incidence | |||||

| At least once in the past 12 months | 0.033*** | 0.017 | 0.029 | 0.047** | 0.029 |

| Observations | 183,939 | 25,428 | 57,687 | 63,100 | 37,724 |

| Volunteering frequency | |||||

| Less than once a month | 0.017 | 0.010 | 0.009 | 0.031 | -0.003 |

| At least once a month but less than once a week | 0.061*** | 0.132** | 0.054 | 0.087*** | 0.012 |

| At least once a week | 0.034** | -0.011 | 0.041 | 0.036 | 0.065* |

| Observations | 183,863 | 25,410 | 57,674 | 63,075 | 37,704 |

Note: Based on a fixed effects model estimating the impact of volunteering at time t on life satisfaction at time t. Each column is based on two regressions: one for volunteering incidence (a binary variable based on whether an individual volunteers or not) and one for volunteering frequency. A coefficient of 0.033 suggests that, on average, volunteering leads to a 0.033-unit increase on a 1-to-7-point life satisfaction scale. The *-signs indicate the statistical significance of the estimates: *** p-value < 0.01, ** p-value < 0.05, * p-value < 0.1. Values in bold indicate statistical significance at the 10% level or higher.

Source: London Economics’ analysis of Understanding Society

7.3 Monetisation results

Based on the incidence of volunteering, we estimate the total wellbeing benefit of volunteering for volunteers in England to be approximately £8.257 billion in 2021/22 (see Table 6), total wellbeing benefit and average wellbeing benefit per volunteer). This figure is obtained by multiplying our core estimate of the average impact of volunteering incidence on life satisfaction (0.033) by the total number of volunteers in England in 2021/22 (12.3 million) and the 2021 WELLBY value, adjusted to a 1-to-7-point scale (£20,634).

We also estimated the average wellbeing benefit per volunteer by multiplying the average impact of volunteering on life satisfaction with the 2021 WELLBY value, adjusted to a 1-to-7-point scale. This amounts to £673 per volunteer and represents the average increase in wellbeing from volunteering at least once in the past 12 months relative to not volunteering.

Table 6: Estimates of the inputs for the wellbeing monetisation, total wellbeing benefit and average wellbeing benefit per volunteer

| Average impact of volunteering on life satisfaction (A) | 2021 WELLBY value adjusted to a 1–7-point scale (B) | Number of volunteers in 2021/22 (C) | Total wellbeing benefit (A*B*C) | Average wellbeing benefit per volunteer (A*B) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| At least once in the past 12 months | 0.033*** | £20,634 | 12.27m | £8.257bn | £673 |

Note: The *-signs indicate the statistical significance of the estimates: *** p-value < 0.01, ** p-value < 0.05, * p-value < 0.1. The 95% confidence interval for the point estimate of the impact of volunteering on life satisfaction (0.033) is [0.012, 0.053]. Total wellbeing benefit may not sum due to rounding.

Source: London Economics’ analysis of Understanding Society, Green Book and Community Life Survey data

8. Effect of volunteering on employment outcomes

Previous literature suggests that volunteering may have various employment benefits. Firstly, volunteering could increase the probability of employment, acting as a pathway into paid work. Paine and others (2013) examined this using Understanding Society and found that volunteering had a small but significant effect on the probability of employment, but the direction of the effect varied across volunteering frequency categories. Volunteers may move into employment due to improvements in human and social capital, as a consequence of activities such as skills training and confidence building. For example, Degli Antoni (2015) found that participation in activities that developed social networks and increased human capital also increased the probability of being employed. Secondly, there is evidence that individuals may acquire a variety of skills (for example, communication and teamwork) through volunteering (Kamerade, 2015), and social capital within firms through employer-supported volunteering (Muthuri and others, 2009).

Alongside the wellbeing benefits to volunteers from volunteering (see Section 7), the skills acquired through volunteering may increase volunteers’ productivity in paid employment. While it is difficult to directly measure productivity improvements through the skills acquired through volunteering, a commonly used approach is to use individual wages as a proxy for productivity.

On the other hand, the relationship between volunteering and employment outcomes could also be negative. Volunteers may decide to work less to have more time for volunteering. This may reduce the hours that volunteers work in paid jobs compared to people who do not volunteer, especially as individuals move towards retirement.

To examine these effects, following our econometric strategy from Section 5, we estimated the impact of volunteering on three employment outcomes:

-

The likelihood of employment

-

Hourly wages

-

Hours worked per week

While not included here, we also present results for the impact of volunteering on monthly wages in Annex A1.9.3.

In our main specification, we consider the impact of volunteering at time t-1 and the outcomes at time t. We also conducted subgroup analyses of each outcome to examine how the effects vary by age group and considered the impact of volunteering on employment outcomes over a longer time period (two or three years after volunteering).

8.1 Assumptions and limitations

Our estimates may not fully capture the employment benefits of volunteering, as there are several methodological challenges. Firstly, data limitations mean that it is not possible to directly measure the impact of volunteering on building skills or productivity improvements. As a result, we use proxies for this, such as hourly pay and employment probability. For example, volunteering may increase productivity in employment through improved teamwork or work ethic which may not translate into higher wages. Secondly, the impact of volunteering on employment outcomes may not be immediate. Skills built through volunteering may take several years to lead to improved employment outcomes. The time periods available in Understanding Society mean that it is not possible to examine the effect of volunteering over a longer time period. Finally, employment decisions may be linked to volunteering decisions. For example, an individual may choose to volunteer because they plan to reduce their hours worked in paid employment. While we used fixed effects estimation and lagged volunteering variables to address this, there may still be some bias in our estimates as a result of it.

Moreover, we decided to not monetise the results of our estimation because they generally provide inconclusive evidence about the presence and size of employment benefits. Unlike the estimate of the impact of volunteering on wellbeing, our estimates of the employment benefits are not as consistently robust. We provide reasoning for not monetising each impact in the sections below. In Annex A1.2, we outline a method that we would have used to monetise the estimates if they had been robust.

8.2 Econometric results

Impact on the probability of paid employment

To understand whether volunteering builds skills that help individuals find employment, we estimated the impact of volunteering on the probability of being in paid employment for volunteers. To look at this, we used a dummy variable, which indicates whether or not an individual is in paid employment. Table 7 shows the estimates by volunteering incidence, frequency and age group.

Table 7 reports partial elasticities, which represent a percentage change in the probability of employment, relative to the baseline employment rate of non-volunteers. For example, a partial elasticity of 0.1 with a 50% baseline employment rate of non-volunteers implies that volunteering increases the probability of employment by 5 percentage points, from 50% to 55%. Note that the baseline employment rate changes across specifications, so the partial elasticities are not comparable across specifications. However, within each specification, the partial elasticities are comparable across frequency categories, as they share the same baseline. Some partial elasticities may appear large, but they may be relative to a low baseline.[footnote 38] Therefore, when comparing across specifications, more attention should be paid to the signs of the partial elasticities (positive or negative) than to their magnitude.

We estimated that volunteering at least once in the past 12 months at time t-1 increases the probability of paid employment at time t by 0.9%. However, this result is not statistically significant and hence does not provide sufficient evidence of a positive impact of volunteering in the past 12 months on employment. This positive result was driven by less frequent volunteers (those volunteering less than once a week), with those volunteering at least once a week experiencing a decrease in their probability of paid employment. Again, the results by frequency were not statistically significant.

Considering the results by age, for those aged 16 to 25, volunteering once in the past 12 months increases the probability of paid employment by 9.1% and is statistically significant. This result is mainly driven by those who volunteer more frequently. For the same age group, volunteering at least once a week increases the likelihood of employment by 17.1%.

We find the opposite effect for volunteers aged 46 to 65, with a decrease in the likelihood of employment by 2.6% for those volunteering at least once in the past year. However, this result is not statistically significant. The effect is stronger for more frequent volunteers, with those aged 46 to 65 volunteering at least once a week experiencing a statistically significant decrease in the probability of paid employment of 7.8%. The positive effect on employment for younger people and negative effect for older people may explain why there is no significant effect in the average effect across all ages.

These results provide weak evidence that volunteering may be a substitute for paid work for older people, but could act as a pathway to work for younger people. Due to the lack of statistical significance, we did not monetise these results.

Table 7: Partial elasticities for the impact of volunteering on the likelihood of employment

| All ages | Aged 16–25 | Aged 26–45 | Aged 46–65 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Volunteering incidence | ||||

| At least once in the past 12 months | 0.009 | 0.091** | 0.020 | -0.026 |

| Observations | 31,824 | 6,235 | 7,909 | 14,129 |

| Volunteering frequency | ||||

| Less than once a month | 0.022 | 0.013 | 0.026 | 0.031 |

| At least once a month but less than once a week | 0.031 | 0.120 | 0.025 | -0.014 |

| At least once a week | -0.011 | 0.171*** | 0.014 | -0.078** |

| Observations | 31,806 | 6,228 | 7,907 | 14,121 |

Note: The figures shown are partial elasticities, based on a fixed effects logistic model, for individuals aged 16 to 65, estimating the impact of volunteering at time t-1 on employment at time t. The results are based on two regressions: one for volunteering incidence (a binary variable based on whether an individual volunteers or not) and one for volunteering frequency. A partial elasticity of 0.009 suggests that, on average, volunteering in the past 12 months is associated with a 0.9% increase in the probability of being employed in the following year, relative to the baseline employment rate for non-volunteers. The *-signs indicate the statistical significance of the estimates: *** p-value < 0.01, ** p-value < 0.05, * p-value < 0.1. Values in bold indicate statistical significance at the 10% level or higher.

Source: London Economics’ analysis of Understanding Society

However, one year may be insufficient for employment benefits to be realised, so we also estimated the impact of volunteering at time t-2 and t-3 on employment at time t (see Table 8). We found that the impact of volunteering was stronger over a two- and three-year time period than after one year, with a 6.2% increase in the probability of employment after two years, and 3.4% after three years. These estimates are both statistically significant at the 5% level. The results also hold across all volunteering frequency categories after two years, with the results becoming stronger as individuals volunteer more. After three years, the partial elasticates are broadly similar across all volunteering frequency categories, but are not statistically significant for those volunteering at least once a month but less than once a week. The results hold across all age groups after two years, but there was only a positive and significant effect for those aged 46 to 65 after three years (see Table 31 in Annex A1.9.3). These results provide some evidence that volunteering could act as a pathway into paid work, as the employment benefits of volunteering may be realised only after a few years of volunteering. However, through our analysis, we cannot identify the specific factors that would cause this employment effect.

Table 8: Partial elasticities for the impact of volunteering at time t-2 and t-3 on the likelihood of employment at time t

| Second lag (t-2) | Third lag (t-3) | |

|---|---|---|

| Volunteering incidence | ||

| At least once in the past 12 months | 0.062** | 0.034** |

| Observations | 28,034 | 24,367 |

| Volunteering frequency | ||

| Less than once a month | 0.039** | 0.036* |

| At least once a month but less than once a week | 0.060** | 0.029 |

| At least once a week | 0.080*** | 0.034* |

| Observations | 28,015 | 24,355 |

Note: The figures shown are partial elasticities, based on a fixed effects logistic model, for individuals aged 16 to 65, estimating the impact of volunteering at time t-2 or t-3 on employment at time t. The results are based on two regressions: one for volunteering incidence (a binary variable based on whether an individual volunteers or not) and one for volunteering frequency. A partial elasticity of 0.062 suggests that, on average, volunteering in the past 12 months is associated with a 6.2% increase in the probability of being employed in two years’ time (for the second lag), relative to the baseline employment rate for non-volunteers. The *-signs indicate the statistical significance of the estimates: *** p-value < 0.01, ** p-value < 0.05, * p-value < 0.1. Values in bold indicate statistical significance at the 10% level or higher.

Source: London Economics’ analysis of Understanding Society

Impact on hourly pay

To examine how volunteering impacts the productivity of volunteers, we used hourly pay as a proxy for the productivity of volunteers in paid work. Table 9 shows the estimates by volunteering incidence, frequency and age group.

We estimate that volunteering at least once in the last 12 months has a negative and significant effect on hourly pay, and is associated with 1.2% lower hourly pay compared to non-volunteers in the following year. This result is primarily driven by the most frequent volunteers, as those who volunteered at least once a week experience 2.8% lower hourly pay than those who do not volunteer, which is again statistically significant. While this negative effect holds across all age groups, it was only statistically significant for those aged 26 to 45.

Our estimates by age group suggest that the impact of volunteering on hourly pay varies substantially by age. Among the youngest group (aged 16 to 25), volunteering in the past 12 months was associated with 5.1% lower hourly pay, with the negative effect persisting across all frequency categories, but becoming weaker for more frequent volunteers. For those aged 26 to 45, there is a small but not statistically significant effect of 0.5% higher hourly pay. However, within this age group, those volunteering less than once a week experienced 1.9% higher hourly pay than those who did not volunteer. Those volunteering at least once a week experienced 2.1% lower hourly pay than those who did not volunteer. For the oldest group (aged 46 to 65), volunteering at least once in the last 12 months was associated with a small but not statistically significant lower hourly pay (0.9%), which was driven by the most frequent and least frequent volunteers.

Table 9: Regression coefficients for the impact of volunteering on hourly pay

| All ages | Aged 16–25 | Aged 26–45 | Aged 46–65 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Volunteering incidence | ||||

| At least once in the past 12 months | -0.012** | -0.051*** | 0.005 | -0.009 |

| Observations | 77,265 | 8,617 | 35,245 | 33,403 |

| Volunteering frequency | ||||

| Less than once a month | -0.005 | -0.069*** | 0.019* | -0.009 |

| At least once a month but less than once a week | 0.000 | -0.050 | 0.019 | 0.002 |

| At least once a week | -0.028*** | -0.028 | -0.021** | -0.018 |

| Observations | 77,241 | 8,612 | 35,238 | 33,391 |

Note: Based on a fixed effects model estimating the impact of volunteering at time t-1 on hourly pay at time t, for individuals aged 16 to 65. Each column is based on two regressions: one for volunteering incidence (a binary variable based on whether an individual volunteers or not) and one for volunteering frequency. A coefficient of -0.012 suggests that, on average, volunteering in the past 12 months is associated with a 1.2% lower hourly pay in the following year, relative to non-volunteers. The *-signs indicate the statistical significance of the estimates: *** p-value < 0.01, ** p-value < 0.05, * p-value < 0.1. Values in bold indicate statistical significance at the 10% level or higher.

Source: London Economics’ analysis of Understanding Society

Looking at the effect over a longer time period, the effect remained negative, but was smaller and not statistically significant after two and three years, at -0.7% and -0.9% respectively (see Table 10). However, for those volunteering at least once a week, a negative and statistically significant effect on hourly pay persists after two and three years, at -2.1% and -2.6% respectively.

The results in this section should be interpreted with caution, as they may capture the impact of external factors, rather than the causal effect of volunteering on hourly pay. For example, it could be the case that individuals volunteer for the same reasons that they have a lower-paid job (for instance as a result of a partner’s higher or increasing earnings). Given that we cannot be sure about how those external factors may influence our estimates, we decided not to monetise the results in this section.

Table 10: Regression coefficients for the impact of volunteering at time t-2 and t-3 on hourly pay at time t

| Second lag (t-2) | Third lag (t-3) | |

|---|---|---|

| Volunteering incidence | ||

| At least once in the past 12 months | -0.007 | -0.009 |

| Observations | 69,131 | 62,623 |

| Volunteering frequency | ||

| Less than once a month | -0.004 | 0.003 |

| At least once a month but less than once a week | 0.010 | -0.007 |

| At least once a week | -0.021*** | -0.026*** |

| Observations | 69,110 | 62,607 |

Note: Based on a fixed effects model estimating the impact of volunteering at time t-2 and t-3 on hourly pay at time t, for individuals aged 16 to 65. Each column is based on two regressions: one for volunteering incidence (a binary variable based on whether an individual volunteers or not) and one for volunteering frequency. A coefficient of -0.007 suggests that, on average, volunteering in the past 12 months is associated with a 0.7% lower hourly pay in two years’ time (for the second lag), relative to non-volunteers. The *-signs indicate the statistical significance of the estimates: *** p-value < 0.01, ** p-value < 0.05, * p-value < 0.1. Values in bold indicate statistical significance at the 10% level or higher.

Source: London Economics’ analysis of Understanding Society

Impact on hours worked

Table 11 presents estimates of the effect of volunteering on weekly hours worked in paid employment for volunteers. We estimate that those who volunteer at least once in the past 12 months and are in paid employment work 0.13 fewer hours (equivalent to around 8 fewer minutes) per week, compared to individuals in paid employment who do not volunteer. This result would suggest that volunteers sometimes substitute paid work for volunteering, but that the extent of substitution is relatively limited, given the small size of the effect and the limited statistical significance of the result (at the 10% level).

The results vary substantially by age. Volunteering at least once in the past 12 months has a positive effect (an increase in the number of hours worked) for those aged 16 to 25, who work an average of 0.595 hours more per week in the following year, compared to individuals who do not volunteer. However, it has a negative effect (a decrease in the number of hours worked) for those in other age categories, with 0.123 fewer hours worked per week for those aged 26 to 45 and 0.150 fewer hours worked per week for those aged 46 to 65. For those aged 16 to 25, the positive effect on hours worked is strongest for more frequent volunteers, while for those aged 46 to 65, the negative effect is strongest for more frequent volunteers. Therefore, these results provide some evidence that volunteering is complementary to work for younger volunteers, and is a substitute for work for older volunteers. However, the estimates presented in Table 11 have limited statistical significance and therefore only provide limited evidence on the effect of volunteering on hours worked, meaning that some caution should be exercised when interpreting the results.

Table 11: Regression coefficients for the impact of volunteering on hours worked

| All ages | Aged 16-25 | Aged 26-45 | Aged 46-65 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Volunteering incidence | ||||

| At least once in the past 12 months | -0.130* | 0.595* | -0.123 | -0.150 |

| Observations | 77,265 | 8,617 | 35,245 | 33,403 |

| Volunteering frequency | ||||

| Less than once a month | -0.091 | 0.170 | -0.199 | -0.001 |

| At least once a month but less than once a week | -0.168 | 1.144 | 0.084 | -0.331* |

| At least once a week | -0.139 | 0.936* | -0.116 | -0.226 |

| Observations | 77,241 | 8,612 | 35,238 | 33,391 |

Note: Based on fixed effects model estimating the impact of volunteering at time t-1 on weekly hours worked at time t, for individuals aged 16 to 65. The results are based on two regressions: one for volunteering incidence (a binary variable based on whether an individual volunteers or not) and one for volunteering frequency. A coefficient of -0.130 suggests that, on average, volunteering in the past 12 months is associated with a 0.130-hour reduction in weekly hours worked in the following year. The *-signs indicate the statistical significance of the estimates: *** p-value < 0.01, ** p-value < 0.05, * p-value < 0.1. Values in bold indicate statistical significance at the 10% level or higher.

Source: London Economics’ analysis of Understanding Society

Estimates of the impact of volunteering on hours worked over a two and three year period are presented in Table 33 in Annex A1.9.3. These coefficients are not statistically significant and show a smaller negative effect of volunteering on hours worked.

Due to the limited statistical significance of these results, we did not monetise the effect of volunteering on hours worked.

8.3 Summary of the employment impacts

Overall, our results present relatively weak evidence on the impact of volunteering on employment outcomes, as the effects identified are relatively small and often not statistically significant. There is some evidence that volunteering may increase the probability of being in paid employment, particularly over a longer time period (two or three years after volunteering). When examining the effects one year after volunteering, the impact appears to be positive for younger people (aged 16 to 25) but negative for older people (aged 46 to 65), suggesting that volunteering may complement employment for younger people while potentially substituting for work for older people.

The results for the effect of volunteering on hours worked in paid employment show similar results. They show weak evidence of an overall decrease in hours worked, with increases in hours worked for younger people and decreases for those aged 26 and over. The results also suggest that volunteering is associated with lower hourly pay for volunteers, particularly for those who volunteer at least once a week. However, this finding may be linked to the decision to volunteer, rather than volunteering having a direct negative effect on skills or productivity.

9. Effect of volunteering on healthcare costs

Alongside the positive effect of volunteering on subjective wellbeing (see Section 7), previous research has found that volunteers often report better physical health compared to non-volunteers (Binder, 2015; NCVO, 2019). As a result, volunteers may require fewer healthcare appointments, leading to potential cost savings for the NHS, and therefore, the government.[footnote 39] As mentioned in Section 5, healthier individuals may self-select into volunteering, meaning that improved health may increase the probability of volunteering. We account for this selection bias in the econometric strategy (for example, through fixed effects estimation) to isolate the effect of volunteering on healthcare appointments. Following the econometric strategy outlined in Section 5, we estimate the impact of volunteering at time t-1 on the number of healthcare appointments at time t.

Based on the data available in Understanding Society, we estimated the impact of volunteering on three outcomes:

-

Number of GP visits per year

-

Number of outpatient visits per year

-

Number of days spent in hospital as an inpatient per year

In Understanding Society, the GP and outpatient variables are coded differently from inpatient variables. As a result, in this section, we present results for GP and outpatient visits in bands,[footnote 40] as provided in Understanding Society, while inpatient days are presented as a continuous variable. As a result, our econometric approach differs across these outcome variables.[footnote 41]

9.1 Econometric results

Impact on GP visits

Considering the effect of volunteering on GP visits, we found no significant effect of volunteering in the past 12 months on the number of GP visits a volunteer makes in the following year (see Table 12). The regression results suggest that the relationship is negative and small, such that volunteering decreases the number of GP visits per year, but this result was not statistically significant. Considering the results by frequency, the effect is strongest and statistically significant at the 10% level for those who volunteer at least once a month but less than once a week. Those who volunteer at least once a month but less than once a week are 1.8 percentage points more likely to have zero GP appointments per year relative to non-volunteers. For other frequency groups, volunteering decreases the number of GP appointments, but the effect is smaller and not statistically significant.

Table 12: Regression coefficients for the impact of volunteering on the number of GP visits of volunteers per year, by volunteering frequency

| Number of GP visits per year | Volunteered at least once in the past 12 months | Volunteered less than once a month | Volunteered at least once a month but less than once a week | Volunteered at least once a week |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | 0.007 | 0.005 | 0.018* | 0.003 |

| One to two | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.007* | 0.001 |

| Three to five | -0.004 | -0.003 | -0.011* | -0.002 |

| Six to ten | -0.003 | -0.003 | -0.008* | -0.001 |

| More than ten | -0.002 | -0.002 | -0.006* | -0.001 |

| Observations | 55,190 | 55,138 | 55,138 | 55,138 |

Note: Based on a fixed effects ordered logistic model. The table is based on two regressions: one for volunteering incidence (a binary variable based on whether an individual volunteers or not) and one for volunteering frequency. A coefficient of 0.007 suggests that being a volunteer increases the likelihood of being in a category by 0.7 percentage points. The number of observations for volunteering frequency is based on the total number of observations used in that regression across all volunteering frequencies. The *-signs indicate the statistical significance of the estimates: *** p-value < 0.01, ** p-value < 0.05, * p-value < 0.1. Values in bold indicate statistical significance at the 10% level or higher.

Source: London Economics’ analysis of Understanding Society

Impact on outpatient visits

Considering the effect of volunteering on outpatient visits, as with GP visits, we found no significant effect of volunteering in the past 12 months on the number of outpatient visits a volunteer makes in the following year (see Table 13). The regression results suggest close to a zero effect overall. Considering the results by frequency, volunteering less than once a month appears to slightly decrease the likelihood of having no outpatient visits per year, and volunteering either at least once a month but less than once a week, or volunteering at least once a week slightly increases the likelihood of having no outpatient visits. Again, these results are not statistically significant, so they should be interpreted with caution.

Table 13: Regression coefficients for the impact of volunteering on the number of outpatient visits of volunteers per year, by volunteering frequency

| Number of outpatient visits per year | Volunteered at least once in the past 12 months | Volunteered less than once a month | Volunteered at least once a month but less than once a week | Volunteered at least once a week |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | 0.001 | -0.019 | 0.021 | 0.008 |

| One to two | -0.000 | 0.003 | -0.004 | -0.001 |

| Three to five | -0.000 | 0.008 | -0.008 | -0.003 |

| Six to ten | -0.000 | 0.004 | -0.005 | -0.002 |

| More than ten | -0.000 | 0.003 | -0.004 | -0.001 |

| Observations | 48,350 | 48,317 | 48,317 | 48,317 |

Note: Based on a fixed effects ordered logistic model. The table is based on two regressions: one for volunteering incidence (a binary variable based on whether an individual volunteers or not) and one for volunteering frequency. A coefficient of 0.001 suggests that being a volunteer increases the likelihood of being in a category by 0.1 percentage points. The number of observations for volunteering frequency is based on the total number of observations used in that regression across all volunteering frequencies. The *-signs indicate the statistical significance of the estimates: *** p-value < 0.01, ** p-value < 0.05, * p-value < 0.1. Values in bold indicate statistical significance at the 10% level or higher.

Source: London Economics’ analysis of Understanding Society

Impact on inpatient days

Considering the effect of volunteering on inpatient days, we found that volunteering slightly decreases the number of days spent as an inpatient in the following year, by around 0.127 days on average (see Table 14). This result was statistically significant at the 10% level. The effect was strongest (and significant at the 10% level) for those volunteering at least once a week (0.170 fewer days spent as an inpatient). The overall negative effect held across all age bands for those volunteering at least once in the past 12 months, and was largest for the youngest (16 to 25) and oldest (over 65) age groups, but ultimately was not statistically significant for any age group.

Table 14: Regression coefficients for the impact of volunteering on the number of inpatient days of volunteers per year

| All ages | Aged 16-25 | Aged 26-45 | Aged 46-65 | Aged over 65 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Volunteering incidence | |||||

| At least once in the past 12 months | -0.127* | -0.329 | -0.039 | -0.018 | -0.163 |

| Observations | 87,273 | 9,181 | 24,587 | 32,068 | 21,437 |

| Volunteering frequency | |||||

| Less than once a month | -0.092 | -0.046 | -0.077 | -0.023 | -0.053 |

| At least once a month but less than once a week | -0.119 | -0.355 | 0.139 | -0.100 | -0.332 |

| At least once a week | -0.170* | -0.659 | -0.090 | 0.042 | -0.171 |

| Observations | 87,214 | 9,170 | 24,577 | 32,047 | 21,420 |

Note: Based on a fixed effects model for the impact of volunteering at time t-1 on inpatient days at time t. Each column is based on two regressions: one for volunteering incidence (a binary variable based on whether an individual volunteers or not) and one for volunteering frequency. A coefficient of -0.127 suggests that, on average, volunteering in one year leads to 0.127 fewer days spent as an inpatient in the following year. The *-signs indicate the statistical significance of the estimates: *** p-value < 0.01, ** p-value < 0.05, * p-value < 0.1. Values in bold indicate statistical significance at the 10% level or higher.

Source: London Economics’ analysis of Understanding Society

9.2 Summary of the healthcare impacts

Considering the results across all types of healthcare appointments, while the results generally indicated that volunteering decreases the number of healthcare appointments of volunteers, the results were generally not statistically significant or robust (see Annex A1.9.4 for robustness checks, including the impact on composite healthcare costs). Therefore, as we were unable to find sufficient evidence to suggest that volunteering decreases the number of healthcare appointments of volunteers, we have not monetised the results of this strand.

The lack of robust results may be driven to some extent by a limited sample size, as we were only able to use three waves of Understanding Society due to the availability of the healthcare and volunteering variables. In addition, the effect of volunteering on healthcare appointments, particularly over a short time horizon, would be expected to be relatively small.[footnote 42] Therefore, while there might be an effect of volunteering on healthcare appointments, it might not be possible to detect it.

10. 8 Effect of volunteering on social outcomes

Previous research suggests that volunteering has a wide range of social benefits to the volunteer and wider society (Abrams and others, 2023). These benefits are related to social and community cohesion (for example, feeling connected to the neighbourhood, and increased civic trust), social capital (for example, stronger social relationships), and soft skills (for example, improved communication skills). The effect of volunteering on soft and social skills was also found to be strong among young people (13 to 14-year-olds) (See and others, 2017). Some of the mechanisms driving these benefits are increased social interactions, trust, pro-social behaviour, and the feeling of making a social impact while volunteering (Abrams and others, 2023).

Understanding Society includes the following variables that can be used as proxies for social benefits:

-

Social isolation

-

Lack of companionship

-

Feeling left out

-

Feeling lonely

-

Feeling of belonging to the neighbourhood

-

Willingness to improve the neighbourhood

However, it is difficult to monetise the effect of volunteering on these variables because a monetary social capital value (like for wellbeing) does not exist. Moreover, there is also the risk of double-counting as some of the social benefits may themselves be mechanisms that drive the impact of volunteering on wellbeing.

The variables used as proxies for social benefits are only available in limited waves of Understanding Society, meaning the impact of volunteering on social benefits can only be estimated in one time period. Hence, we cannot use a fixed effects model to account for the fact that individuals’ social outcomes could influence their likelihood to volunteer (thereby introducing selection bias to our estimates). For example, an individual could choose to volunteer because they feel lonely, rather than volunteering causing loneliness.