Environment Agency response to the Independent Water Commission's call for evidence

Published 3 June 2025

Applies to England

Introduction

The Independent Water Commission published their Call for Evidence on 27 February 2025 seeking views in relation to the water sector in England and Wales.

The Environment Agency’s response focuses on the following themes in the Call for Evidence:

- overarching framework for the management of the water sector

- the regulators

- economic regulation

- water industry public policy outcomes

1. Overarching framework for the management of water

1.1 Management of water

Water is fundamental to our lives and livelihoods, from water in our taps to the food we grow, from flooding to drought. The water system affects and is affected by everything we do as a society. Over time the policies and interventions to manage water as a whole system have become fragmented.

The Water Framework Directive (WFD) is over 20 years old. Much has been achieved through River Basin Management Plans (RBMPs) making the case for investment in water infrastructure to meet challenges like nutrient pollution, climate change, and changes to water levels and flows.

However, fragmented responsibilities, regulations, plans and planning cycles, have hindered action from other sectors. For example, nutrients and sediments from agriculture and phosphorus in wastewater are a major reason why water quality is not as good as we want it to be. An estimated 70% of nitrate pollution, 25-30% of phosphorus and 75% of sediment pollution in the water environment comes from agriculture. Between 60-70% of phosphorus is from sewage effluent. With the reductions planned by the water industry, the contribution of agriculture to total phosphorus loads in freshwaters becomes increasingly important.

If we are to achieve clean and plentiful water, this requires change. A significant and long-lasting step change in management of water can only come from simultaneously addressing all sectors that affect the water system and ensuring the planning and regulatory frameworks work together effectively.

In the current water management framework, the Environment Agency oversees water outcomes by supporting and coordinating local partnerships and funding across a catchment through catchment-based approach (CABA). Accountability for delivering actions sits mainly with other organisations, including water companies, land managers and local authorities, who face a range of competing pressures and incentives. The ability to influence delivery decisions varies across organisations.

1.1.1 Responsibilities for making decisions about what outcomes to prioritise from the water system

Government should decide the strategic direction and national priorities for water considering affordability and how to provide certainty for growth and investment.

Decisions on priorities should be taken with a full understanding of the water system, the extent of the pressures, the strategic solutions that could be implemented, the cost of doing so, and knowledge of the cumulative impacts of addressing multiple pressures together. Currently decisions are taken independently and piecemeal.

The Government’s priorities should be set through a statutory framework to provide the water (quality and quantity) regulatory baseline across England (currently this includes the environmental objectives set out in the River Basin Management Plans such as ‘aim to achieve good status’ under the Water Environment (Water Framework Directive) Regulations 2017 (the ‘WFD Regulations’)).

Rules, set by Government, could then determine how any exemptions from meeting those baseline requirements are determined in a fair and transparent way. This would in turn determine how far and how fast environmental improvements can be made against stretching, but realistic, apex targets.

The Government’s priorities should be under-pinned by published policy delivery pathways for each sector (for example, water industry, agriculture, urban etc.) to meet the statutory requirements, for example, the Environment Act targets. There must be relevant duties on polluters, legal powers for regulators, and effective mechanisms to deliver against the statutory requirements.

Water management is complex and requires collaboration across various actors rather than resting with a single body. A shared system with clearer objectives, accountabilities and responsibilities at each level allows for specialised expertise, geographical flexibility, and balanced decision-making, ensuring a more effective and holistic approach to environmental action.

Additional priorities beyond statutory minimum requirements could be devolved to regional or local catchment level involving all relevant and interested parties reflecting local needs and views, for example, a focus on aesthetics, litter, recreation, access, wild swimming. For example, security of supply would be a national decision; choices on solutions and how quickly to tackle unsustainable abstraction could be made at regional or local catchment level. Underpinning this would be a clear governance structure which can adapt to ensure that strategy and delivery remain co-ordinated as circumstances change.

To enable local, regional, and national stakeholders to engage and contribute to decision-making there should be a statutory consultation process on the government’s priorities and the pace of change required. Engagement and collaboration on water plans is crucial to the public understanding the complexities of managing and improving the water environment. However, engagement needs to be effective to maximise opportunities and not stifle action.

A Statement of Common Ground could be used to demonstrate that the key bodies involved in delivering the water environment priorities have effective and ongoing cooperation and have strategies that as far as possible are based on agreements with other interested parties.

The independent review of Defra’s regulatory landscape - the Corry Review - supports this; a refreshed set of outcomes for regulators with a clear accountability framework (Recommendation 1) and publishing new Strategic Policy Statements restating Government’s priorities (Recommendation 2).

1.1.2 Trade-offs

Current legislation provides limited scope for regulators to assess the total impact against the total benefit of an action. This restricts the ability to make pragmatic decisions about whether some impacts are worth accepting to enable the greater societal good, resulting in actions which do not achieve the best possible environmental and societal outcome.

Trade-offs could allow robust decision-making that strives for the greatest environmental and societal benefit overall when considering provision of infrastructure. Trade-offs are not to make environmental regulation less rigorous or to enable environmental derogation. Trade-offs allow informed decisions to be made that fully consider impacts versus benefits to assess if a trade-off could be acceptable. Decisions on trade-offs should also take account of timing considerations as well as direct comparison over different time frames.

Government should ultimately decide on trade-offs involving consultation with all relevant stakeholders. Where competing proposals meet environmental objectives, environmental capacity should be prioritised and allocated to best reflect public interest and value for money.

Environmental trade-offs are difficult under currently regulatory framework, given the high level of environmental protection afforded by, for example, the WFD Regulations and the Conservation of Habitats and Species Regulations 2017 (as amended).

The Environment Agency can consider prioritisation between growth and the environment through a ‘derogation’. Where overriding public interest applies (for example, the need for critical infrastructure), these decisions need to be evidence-based and site specific.

For example, the Strategic Resource Option (SRO) Programme secures public water supplies now and into the future, as well as environmental improvements by enabling the reduction of harmful abstraction and protection of vulnerable habitats, for example, chalk streams. The SRO Programme strives to support the government’s growth agenda without compromising environmental outcomes.

Case study: Reservoir Water Framework Directive designation

A Strategic Resource Option may entail provision of a new reservoir built for the purpose of public water supply.

Currently new reservoirs will be designated Water Environment (Water Framework Directive) Regulations (WFD) water bodies and will need to meet ‘good’ status for water quality within the River Basin Management Plan cycle timeframe. The treatment costs of meeting ‘good’ may render the new reservoirs infeasible and could lead to non-reservoir options (for example, desalination), which have their own environmental risks and lack the multisector and wider environmental benefit potential of reservoirs, being progressed preferentially.

There are a number of potential options that would not require the Strategic Resource Option to undertake full water treatment enabling new reservoirs to be viable. However, these options are likely to need some legislative change which include allowing longer term and/or lower objectives to be set or not designating new water supply reservoirs as WFD water bodies.

The trade-off is accepting a lower environmental standard in a new water body or a longer timeframe to reach the standard to enable essential water supply infrastructure.

Case study: Fens Reservoir and open channel transfers

Water transfers associated with the Fens Reservoir Strategic Resource Option are either via open channels or through pipes. Open channel transfers have associated benefits such as potentially reduced costs, opening river navigation, community access to water, and habitat creation opportunities. Raw water transfers could potentially increase the speed of the spread of invasive non-native species (INNS) and potentially deteriorate the water chemistry of water bodies receiving the transfer.

Permitting the open channel transfers would be difficult if the speed of spread of INNS is shown to increase, even though INNS would likely reach the same watercourses by the time the infrastructure was built and operational. Equally, if transferred water introduced a failure in a small number of chemical standards, there is no provision to accept the local impact in order to realise the overall benefits.

If scope of the use of Regulation 19(1) WFD Regulations were expanded, it could potentially be used in cases like this to realise greater environmental benefits.

1.1.3 Changes to roles and responsibilities for water management

Integrated Water Management is a collaborative approach to both land and water governance that integrates social, environmental, and economic factors to deliver coordinated management of water storage, supply, demand, wastewater, flood risk, water quality and the wider environment. Integrated water management requires industry, government and people to work together to plan, prioritise and invest for water at local, regional and national scales.

The governance of water management necessitates making sustainable decisions on funding, investment, planning, and asset operation to protect and restore the natural water environment, manage climate extremes, whilst ensuring clean and plentiful water is available for human needs. The current allocation of responsibilities across national, regional, and local levels is not framed to deliver the scale of environmental restoration and transformation required to achieve clean and plentiful water.

In the current governance framework, different organisations contribute to different parts of water management with minimal cohesion to deliver all the required actions across multiple sectors or scales. This results in significant deficiencies in delivery and hinders strategic prioritisation of actions. It is a key reason for limited progress against the Environmental Improvement Plan 2023 water goal.

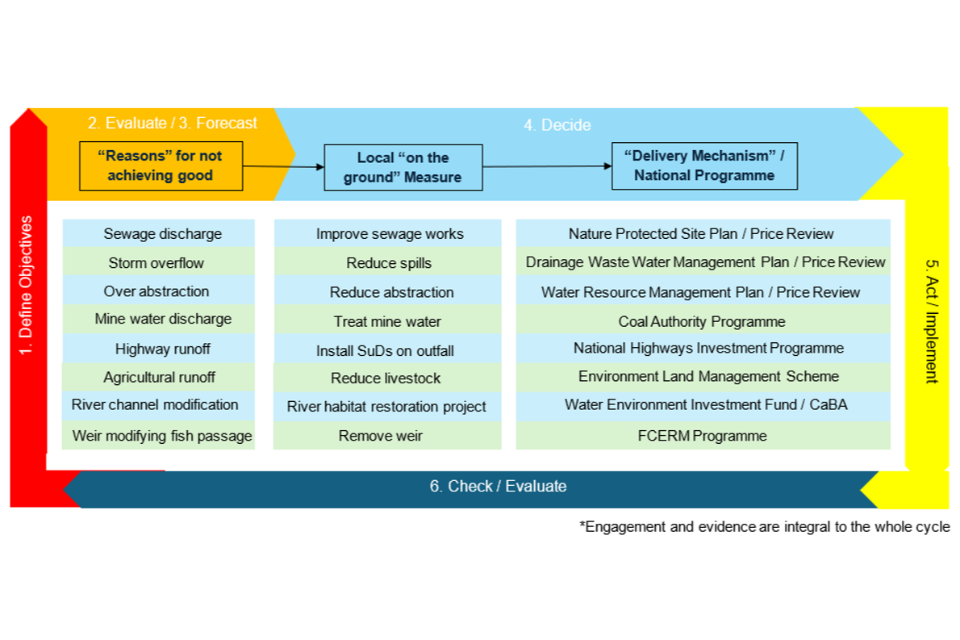

Figure 1 provides an overview of the water environment planning and delivery framework. The framework operates at national, regional and local (catchment) levels for different environmental pressures (for example, water quality, quantity and habitat), sectors (for example, water industry, agriculture, industry, housing), as well as water types (for example, rivers, lakes, groundwater, coastal waters and seas).

Figure 1: The Water Environment Planning and Delivery Framework

Strategic overview is vital to improve coordination by operating both horizontally and vertically across different parts of the management framework harnessing the contributions from all sectors and levels. The efficiencies gained would ensure the whole coordinated framework delivers more than the sum of its individual contributions. The Environment Agency already holds the flood strategic overview for all sources of flooding, including surface water and can see efficiencies in the creation of a strategic management overview for the whole water environment to drive collaboration on the water environment planning and delivery framework to:

-

Set the strategic direction for water and define outcomes and objectives for water across different sectors and delivery partners. The responsibility for setting overarching national policy must remain with the Government. The strategic overview role will advise and support the Government in delivering its policies.

-

Custodian for evidence, data and understanding of the water environment, risks and future needs, and facilitating sharing across partners.

-

Lead and coordinate partner contributions including those of other regulators. A key part of this will be convening relevant cross-sectoral partner engagement through effective governance, facilitating smooth operation to build relationships and trust.

-

Oversight of water investment across multiple funding programmes, noting the scale and pace of funding will remain with the Government.

-

Track and evaluate progress and assure delivery of measures toward achieving water objectives and targets from all partners driving continuous improvement.

This is a distinctly different role to ‘systems operation’ which is focussed on tactical delivery of parts of water management. The Environment Agency does have a role in operation of some parts of the water system (for example, regulation and monitoring).

Strategic leadership and regional collaboration can actively support local authorities, water companies, and other partners to create greater leverage in delivering outcomes.

As already recommended by the Corry Review, in enabling Government’s growth priorities, closer alignment of responsibilities is integral for the parallel processes of planning for water infrastructure and planned development by all the main parties involved (Local Planning Authorities, mayoral authorities with planning powers, water and sewerage companies, the Environment Agency, Natural England, Ofwat and Defra).

To reflect and take account of local pressures and priorities, local and strategic planning authorities should be empowered and resourced to define and deliver interventions within a national framework. Strategic authorities can play a crucial role in preparing for the future and tackling climate change and nature emergencies at the local and regional level. Local, place-based environmental leadership is an essential part of this.

Role of catchment partnerships

Catchment management and the role of catchment partnerships, including those in estuarine and coastal areas, remains fundamental to effective water management. Local partnership groups, like CABA can actively develop evidence-based local actions and implement catchment planning, investment, and delivery, giving more power to communities to define the outcomes they want for people, the economy, and wildlife. Local groups can set priorities for local improvements using their knowledge of geography and local pressures. Building inclusive partnerships to co-design and deliver local, catchment wide and coastal solutions in collaboration with stakeholders, including marginalised groups, will ensure an environment fit for all.

Role of National Framework for Water Resources and regional groups

The Environment Act 2021 (S78) introduced changes to the Water Industry Act 1991 (new S39E) to enable the Secretary of State to direct water companies to prepare and publish joint proposals for the purpose of improving the management and development of water resources. This provides the ability for the public water supply component of regional water resources plans to be made a statutory requirement. It does not make provision for multi-sector regional water resources plans to be fully statutory, but it does give them a formal footing and it does allow for a requirement for other sectors to be consulted and engaged in the development of proposals.

The Environment Agency commissioned Mott MacDonald to review governance arrangements for multi-sector water resources planning in England (and parts of Wales) and provide recommendations to strengthen engagement with non-public water supply sectors. The review confirmed the importance of having a national overview and improving coordination, cooperation and improved efficiency. Improved national co-ordination is critical to help set strategic direction, facilitate information flows, smooth reconciliation, and aid development of common standards and metrics to maintain consistency across regional groups and other sector organisations. In line with the review’s recommendations, the Environment Agency are making improvements to governance and national coordination for water resources, which will ensure the major sectors of water use are represented and help better planning and delivery of water resources resilience.

1.2 Management of the water environment

1.2.1 Review of the Water Environment (Water Framework Directive) Regulations

The Water Framework Directive (WFD) is over 20 years old. It no longer reflects the challenges facing the water environment and associated water management issues in England including the biodiversity and climate change crises, population growth, changing energy and food production needs. Water management regulation does not fully address the interests or uses the public want from England’s waters.

The independent review of Defra’s regulatory landscape, the Corry Review, noted that it strongly supported “reform of these regulations to ensure they deliver long-term stability and clarity and reflect the needs of customers and the environment”. There is opportunity to ensure the WFD Regulations work to deliver nature recovery whilst supporting economic growth.

The Environment Agency supports a review and possible reform of the WFD Regulations and their implementation. Any review and potential reform of legislation is Defra’s responsibility. The Environment Agency’s experience of implementing the WFD Regulations and technical expertise can support this task.

A review of the water management framework for England should aim to maintain the current high levels of environmental ambition, address the range of current and futures issues affecting how people and businesses value and use the water environment, and increase the pace of improvement.

The review should draw from the best science and be informed by UK and international experience of dealing with current and emerging water management issues. Collaboration and knowledge sharing is key to reform. Learning from stakeholders can enhance the knowledge to identify what works and where there might be opportunities to do things better. A particular challenge will be the need to draft any new legislation in a way that enables future requirements to be adapted in response to climate change.

Not all water related issues can be addressed by amending or adding to the planning and delivery processes implicit in the WFD Regulations. Any review would therefore need to consider approaches outside the simple scope of WFD Regulations reform. For example, policies and regulations related to management of land and chemicals.

What should be retained

- An ecosystem approach requiring action to be taken to encourage the sustainable use of water that considers biodiversity/ecology, water quality, water quantity, physical habitat, and the impact of invasive non-native species. Maintaining an ecosystem approach will help build further resilience to the impacts of climate change in the benefits and services provided by the water environment.

- The high level of environmental ambition with the aim of preventing deterioration and aiming to achieve good status.

- A strong legal basis for the Environment Agency’s water related activities, including the legally binding objectives for the water environment that underpin long term planning and the Environment Agency’s regulatory activities.

Improvements to make

- A wider suite of targets that cover the services and benefits reflecting the public’s aspirations for the water environment. This might include recreation, aesthetics, microplastics and access.

- The development of sufficient scientific understanding to enable locally specific environmental objectives to be set which take into account the impact of climate change.

- A stronger role for local (regional/catchment) governance of water management issues. This could include prioritising action towards the most important benefits and services in their catchments.

- A more flexible approach to monitoring and reporting the state of the water environment, including the use of evidence provided by citizen science, businesses, and remote sensing.

- Identify specific requirements for specific public bodies to use in the exercise of their functions to help achieve environmental objectives and measures identified in the River Basin Management Plans.

- A single set of locally specific water environment objectives for those waters which are both water bodies and water dependent nature sites, including European sites and other water dependent Sites of Special Scientific Interest.

- A simplified approach to setting objectives and identifying improvement measures for the physical aspects of water bodies that have been modified for specific uses, such as flood defence, navigation, water supply, and land drainage. Maintaining protection for the specific uses, while finding more effective ways of mitigating unnecessary impacts, is needed.

- A more flexible approach to the process required for updating River Basin Management Plans is needed, including the specific content of the plans. Aspects with clear benefits should be kept whilst reducing administrative burdens. Better alignment of the timetables for updating the River Basin Management Plans and Ofwat’s periodic review of water company price limits should be considered.

Consideration on Regulation 19 WFD Regulations

River Basin Management Plans developed under the Water Environment (Water Framework Directive) Regulations 2017 (the “WFD Regulations”) contain legally binding environmental objectives. These include objectives to prevent deterioration and aim to achieve good status for water bodies as required by the duty on Environment Agency and SoS to exercise their functions so as to secure requirements of WFD under Regulation 3.

Regulation 19 of the WFD Regulations relates to new modifications to the physical characteristics of a surface water body, alterations to the level of a groundwater body, or new sustainable human development activities.

Any modifications, alterations or activities considered likely to compromise the environmental objectives in River Basin Management Plans must meet certain and specific tests and undergo a thorough assessment before they can be authorised under Regulation 19. For example, the risk to the achievement of the environmental objectives caused by the movement of polluted water or invasive non-native species can in many cases be mitigated. However, the cost of fully doing so may compromise the viability and economic case for the reservoir or water transfer.

Case study: Minworth – Grand Union Canal Transfer

Early monitoring and modelling work show that adding the treated recycled water from Minworth Advanced Water Treatment Plant will improve the water quality concentrations in the Grand Union Canal of a significant number of substances. However, without further intervention, there are a small proportion of substances in the discharge which could present a potential Water Environment (Water Framework Directive) Regulations compliance risk.

If legislation allowed for a decision to be made that assessed local impact versus overall benefit, we could potentially determine that proposals are an improvement overall and a longer-term plan to address any failures could be made.

The use of Regulation 19(1) is not applicable to this scenario as it does not cover failure to achieve good chemical status and, for ecological status parameters, is only available for effects arising from modifications to the physical characteristics of water bodies. It is not available for the direct input of pollutants. If the applicability of Regulation 19(1) were expanded to include the direct input of pollutants it could potentially be used in this situation.

1.3 Strategic direction for the water industry

1.3.1 Government’s role in setting the strategic direction for the water industry

Government should set the regulatory framework, including:

- ensuring water regulators have the powers necessary to fulfil their duties

- setting the priorities for regulation and in particular the services and outcomes that regulation should facilitate. This should include supporting high-level targets for the industry

- balancing the needs of the environment, customers and companies in its advice

- being transparent in how the policies and priorities for the water industry align with those relating to other sectors for example, transport, construction, energy, agriculture, and information technology

- ensuring water regulators have regard to the desirability of promoting economic growth, alongside the delivery of environmental protections set out in relevant legislation

- timely advice and guidance are crucial to the success of the investment cycle

1.3.2 Changes to how government provides strategic direction for the water industry

Government direction should describe the expected interface between the water industry and other sectors and detail the opportunities that exist for join up and alignment. Change on the scale needed, requires collaborative action across government and all major water users, as well as a legislative change and national strategic direction to engage businesses and consumers.

Currently, the strategic policy statement (SPS) sets strategic priorities for Ofwat but not specifically for environmental regulators. The SPS typically aligns regulator’s objectives and goals and provides a summary of government policy and legislation but provides no steer on trade-offs. Expectations of water companies’ overall environmental performance, both statutory and non-statutory, are set out elsewhere by the Environment Agency and Natural England. For example, in the water industry strategic environmental requirements (WISER) document.

One suggestion proposed in an Environment Agency review commissioned for the National Framework for Water Resources is a Defra-led national forum which sets direction for the industry and regulators on expectations and standards, which will be better able to resolve any policy conflicts.

1.3.3 Water companies use planning frameworks more effectively to fulfil their duties and deliver their functions

Water company investment plans should demonstrate, as far as possible, alignment across other relevant plans (for example, Local Nature Recovery Strategies, River Basin Management Plans, spatial strategies).

Planning frameworks should include consistent metrics (where needed) and monitoring of delivery and environmental outcomes to enable better tracking of progress.

Confidence in delivery of investment through Water Resource Management Plans (WRMPs) and Drainage and Sewerage (Wastewater) Management Plans (DWMPs) would benefit from reform that gives a legal duty in the legislation requiring water companies to deliver the short-term, high confidence actions within statutory plans.

The planning frameworks and regulatory systems and levers that are in place for the water industry to set standards and provide a funding mechanism simply do not exist for pressures such as farming, transport, physical modification, chemicals or pharmaceuticals. To plan ahead for water needs and source control we need all sectors to play their part.

The ‘best value’ approach for the 2024 Price Review (PR24) has started to move the Water Industry National Environment Programme (WINEP) in this direction, but further work is required to connect water company investment with other sectors such as agriculture, industry, or housing requirements. The Environment Agency’s National Framework for Water Resources exemplifies a framework that aims to foster make these connections by promoting multi-sector planning.

River Basin Management Plans

River Basin Management Plans (RBMPs) cover objectives and set measures for multiple sectors, beyond the water industry, such as agriculture. Water companies have a legal duty to have regard to the relevant RBMP when carrying out current and future activities, such as abstraction (for consideration within WRMPs) or the return of treated wastewater (for consideration within DWMPs), supporting the achievement of the environmental objectives under the WFD.

Aligning RBMPs more closely with the price review cycles with the outputs informing DWMPs (for environmental risks) and WRMPs (environmental destination) would help manage environmental and societal risks (for example, public health).

Statutory Planning Frameworks

There are two statutory planning frameworks water companies use to prepare, publish and maintain (continue) to meet their water supply and wastewater duties under section 37 and section 94 of the Water Industry Act 1991 respectively - Drainage and Sewerage (Wastewater) Management Plans (DWMPs) and Water Resource Management Plans (WRMPs). DWMPs and WRMPs must reflect the risks and associated investment need to respond to the pressures of population growth and climate change.

To date DWMPs have only run on a non-statutory cycle and are in their infancy. The DWMPs are commencing their first statutory cycle ahead of PR29 with government guidelines issued to companies in March 2025. It is too early to recommend changes to make DWMPs ‘more effective’.

If Government is seeking regulators and other stakeholders to proactively review companies proposed drainage and wastewater investment plans and to encourage more cross-sector outcomes and benefits with other stakeholders, for example, local authorities, and other drainage asset owners, secondary legislation is required to define the statutory roles of others on DWMPs, including the Environment Agency.

As long-term adaptive plans, the five yearly cycles (with annual reviews) of the WRMPs and DWMPs enable the plans to account for uncertainty associated with climate change, population growth, technological advances and new legislation, especially into the long-term.

The ambition of the plans, and expectation of delivery, should not be constrained on grounds of affordability or willingness to pay, which may change overtime. It is important WRMPs and DWMPs provide an unconstrained view of investment need to continue to meet obligations, whilst being transparent on the scale and pace of investment need.

Water Industry National Environment Programme

The Water Industry National Environment Programme (WINEP) is a delivery mechanism for elements of the WRMP and DWMP (for example, capital investment for storm overflow improvements). There are also certain drivers and statutory measures and government priorities (for example, continuous water quality monitoring, chemical investigations) in the WINEP which sit outside of DWMPs and WRMPs which drive an improved understanding for future investment need.

The WINEP should remain a separate agile, short-term programme to be flexible to new or changing environmental obligations. The WINEP gives regulators and government confidence companies will meet new permit or licence changes. Brigading the WINEP into statutory strategic planning frameworks, especially DWMPs which are in their infancy, prohibits that flexibility and ability to track delivery.

The water industry must be transparent on investment (current and future) on capital maintenance, asset health, resilience and wastewater (and water) supply-demand activities which are outside of any WINEP enhancements to meet new or changing obligations. For the first time ahead of PR29, statutory DWMPs and the associated guidelines provide a framework for the current and future planning and investment need for capital maintenance, asset health and wastewater supply-demand elements of companies’ drainage and sewerage operations.

Spatial planning

DWMPs and WRMPs consider the content of relevant local development plans when accounting for future population growth, demand and urban development, including impact on flood risk, water demand and treatment capacity.

Better links are needed between spatial plans and water plans to ensure investment and development are located where environmental capacity is available. For example, housing growth should match water availability.

Robust and reliable local development plans reflect expected growth within an area, informing the associated demand on the water supply and wastewater systems in WRMPs and DWMPs. Local development plans should reflect the spatial understanding of risks associated with unplanned growth presented in companies WRMPs and DWMPs, for example, limited wastewater capacity.

There are proposals in place for the water industry to be bound by the ‘requirement to assist’ in plan making set in the Levelling Up and Regeneration Act 2023. This proposal needs to be confirmed through secondary legislation. Once in place, Local Planning Authorities (LPAs) can expect water companies to assist them in the early stages of plan making. The next step is to have clear expectations on what LPAs should seek from water companies and what water companies should expect from LPAs when planning growth.

This could be facilitated by a requirement for LPAs to consider strategic water and wastewater requirements for their local plan, which could be part of a water cycle study. Water companies can also help boost water supply by helping LPAs set appropriate water efficiency policies in their local plans. This should help LPAs go beyond Building Regulations’ requirements for water efficiency for housing. It would also promote bespoke and ambitious approaches for commercial water efficiency, maximising water efficiency where opportunities are greatest in the commercial sector, but recognising some non-residential development will find it more difficult to be highly water efficient for example, some health facilities.

2. The regulators

2.1 Changes to the framework of water regulators to improve the regulation of the water industry

The water industry is underperforming, and it needs to change. We know that people want and deserve more for their water environment. We want to be a modern, confident and efficient regulator. To enable this, a new model for regulation was developed with the launch of the Environment Agency’s Water Industry Regulation Transformation Programme (WIRTP) in 2023. The programme set out measures to transform the way we regulate the water industry to drive better performance from water companies.

We are working hard to transform the water industry with respect to water quality by:

- improving access to data and information, such as environmental performance and permitting data

- increasing our regulatory compliance work for the water industry focusing on wastewater treatment assets

- developing innovative permitting and digital tools enabling us to turn regulatory and environmental data into an intelligence-led approach to target future effort

- streamlining our enforcement approach to more rapidly address non-compliance

- using the evidence we gather from audits and increased regulation to inform annual performance assessments, investment plans and programmes (including the DWMP, WRMP and WINEP) and enforcement action

The water industry should remain accountable for their performance commitments and compliance with environmental obligations to build public trust and raise confidence in the water industry.

Fundamental regulatory reforms could further clarify responsibilities and enhance industry performance and resilience, creating an anticipatory, integrated system that supports the timely and sustainable development of water infrastructure.

For example, a fair and equitable legislative and regulatory oversight of the whole water system and pollution apportionment is required to protect security of supply, all abstractors and the environmental needs at a national and catchment scale. This would enable fair and socio-economically sustainable allocation of water to avoid over exploitation of shared resources. A statutory framework for the water industry alone will not solve the challenges of water supply.

Proposed changes to enhance the framework of environmental regulators and improve the regulation of the water industry are:

- introduce a legal duty on the water companies as part of their ‘licence to operate’ to cooperate with all regulators, as well as a legal duty to implement, invest appropriately and comply fully with relevant environmental legislation

- clarify and resolve overlapping Environment Agency and Ofwat responsibilities and duties for sewerage and the sewer network to enable more effective outcomes. For example, the economic regulator is the “Authority” which ensures the infrastructure maintains compliance with the associated obligations within the Water Industry Act, but the Environment Agency regulates the discharges to the environment under the Environmental Permitting Regulations (EPR)

- water companies should be proactive and not wait for permit non-compliance, pollution incidents or missed performance commitments to drive improvements in areas of capital maintenance and renewing or upgrading assets. They should utilise the first cycle of statutory DWMPs and ongoing research programmes to understand the current and future health and resilience of drainage and wastewater assets and systems. This would enable a consistent approach to defining and measuring asset health and resilience standards between the Environment Agency, the Drinking Water Inspectorate and Ofwat. We recognise these would need to be different across the water supply and wastewater assets

- a wider reform agenda that covers all water industry regulated activity, reviewing investment, and the supply chain could stimulate innovation to create markets to improve disposal routes for nutrient wastes including sewage sludge (biosolids) and to stimulate growth in technology and innovation in nutrient recovery (refer to Nutrient System case study for further information)

- greater visibility of the pipeline of water infrastructure projects to allow proactive planning and alignment across government departments helping identify and mitigate regulatory challenges before they arise

- there are gaps in flow of information, critically in a systematic way to track water company actions following compliance recommendations. We would like water companies to have a ‘duty to inform’ us about the actions they have taken following Environment Agency inspections and audits, closely aligning with our ‘duty to cooperate’ recommendation. This would place further onus on water companies to self-report and ensure we have access to better information about compliance response

2.2 Extent water industry regulators have the capacity, capabilities and skills required to effectively perform their roles

Effective and proportionate regulation is vital for our country’s growth and transformation needed to meet the challenges for nature and climate, while protecting the environment and communities we serve. This requires a workforce that is fully capable and equipped with future-ready specialist and regulatory skills, and the best evidence and technology, helping business to invest where regulatory action is targeted to poor performers.

We set out in the Chief Regulator’s Report 2023-24 the work of our Regulatory Services Programme (RSP) to transform our environmental regulation and permitting service across all regulated sectors, providing a consistent set of digital capabilities and business processes underpinning our environmental regulation including covering water regulation. RSP provides:

- improved user experience and more services online

- operational productivity gains within the Environment Agency

- delivering reusable solutions

- decommissioning legacy systems – reducing cost, reducing cyber security risk and risk of failure

- improved data

- simpler permits and giving applicants greater certainty and transparency around the processing of more complex permits

RSP work completed during 2022-23 delivered £23.4 million of benefits at end of Q4 2023-24. This includes an estimated £344,000 in savings for regulated business.

Continued investment in our capacity and capability is vital to enable us to deliver modern, effective regulatory and customer services. More stable and consistent funding will enable continued support for our transformation into a digitally delivered regulatory service.

We launched a public consultation in January 2024 on proposed changes to our environmental permitting charges for water quality permits (under the Environmental Permitting (England and Wales) Regulations 2016 (Environmental Permitting Regulations). These charges had not been revised since 2018. We designed the changes to recover the full cost of our services to achieve and sustain expected levels of regulatory and environmental performance.

A similar full review of water abstraction charges has not taken place in over a decade and cost recovery aspects of the Water Resources service have remained flat since 2012.

Using the additional funding from the water quality permit charges review we are changing how we regulate the water industry. This shift ensures that we don’t just focus on compliance and maintenance but also on long-term planning, investment, and tackling root causes. In 2023 we set ourselves ambitious targets to recruit more staff and significantly increase the number of inspections. We achieved what we set out to do but this is only the first step on the road to sustained improvement. By March 2027 we will have 500 staff including environment officers, data analysts, enforcement specialists and technical experts as well as team leaders and managers to lead new regulation teams.

We are also increasing our inspection and audit work substantially to understand the true scale of non-compliance. Inspections will rise significantly to 4,000 a year by the end of March 2025; 10,000 a year by March 2026 and 11,500 a year by March 2027. With an increase in inspections and targeted audits on water companies, we will be uncovering more non-compliance. This doesn’t mean impacts on the environment are going up, as we expect much of it to be ongoing historic issues. Performance will, however, initially look worse, but through increased enforcement activity we will work with operators to improve compliance.

The WIRTP will invest around £15 million on enhancing our digital systems and tools. We are improving existing tools and developing new ones that will enable us to receive, store, analyse and validate data. Data and information from lots of sources will be combined in a risk planning tool to provide a risk rating for water company assets. This will improve our ability to turn data rapidly into regulatory intelligence so that we can easily identify and tackle the highest priority issues.

Over the next three years £15.8 million is prioritised for water company enforcement. We will increase our enforcement capacity, taking action to respond swiftly when pollution and environmental harm has been found.

Additionally, legislative changes like the Water Special Measures Act and increased funding are strengthening our ability to enforce. These measures will hold water companies accountable, ensuring they take responsibility and drive real, lasting improvements in how they protect the environment.

Case study: Compliance Toolkit for Water Quality

The Compliance Toolkit for Water Quality helps to streamline data collection and reporting processes. The toolkit provides a more efficient, accurate way of processing data and improves our approach to intelligence-led compliance work. For example, the event duration monitoring and dry day spills tool which has an interactive dashboard and maps so data can be visualised in a user-friendly way, with capability for data filtering and downloading for further analysis of detailed data.

Specialist water sector skills

Our water regulatory and planning capability depends upon attracting, retaining and training people with the capabilities needed to protect and enhance the environment and communities we serve. We simply cannot achieve this without people skilled in regulation, water and environment planning, and sciences such as Hydrology and Hydrogeology which underpin our evidence and regulatory activities. In addition to our WIRTP, we are engaged in the Government Professions Networks and Environment Agency-led ‘specialist skills’ programmes to support career entry, career development, resilience and skills development within select water and environmental disciplines.

However, further interventions on specialist pay rates and retention awards are necessary to get to a resilient workforce for now, for a future system and in periods of drought when specialist skills are vital. Recommendation 6 from the independent review of Defra’s regulatory landscape - the Corry Review - recommends an assessment by Defra of the potential for regulators to have targeted pay flexibility so they can employ and retain staff, particularly specialist staff. We welcome support to prioritise water specialists through this review.

3. Economic regulation

3.1 Better enable the water industry to deliver positive outcomes

Ofwat’s price review has the potential to be a tool for greater transformation. Several changes would help the price review process focus more effectively on long-term, positive outcomes:

- Shift to outcome-based regulation. Tie revenue allowances more explicitly to long-term outcomes, environmental quality, asset health, resilience, rather than just cost efficiency or input delivery.

- Strengthen accountability mechanisms. Make funding conditional on credible delivery plans and enforce stronger consequences for underperformance, including automatic adjustments or licence reviews.

- Incentivise co-investment and cross-sector collaboration. Recognise and reward joint delivery models, particularly those that bring in third-party funding or support catchment-wide solutions.

- Create space for innovation. Ringfence investment for high-impact R&D and remove disincentives for trialling alternative approaches.

A key barrier for many high-profile growth projects is failure to consider environmental limits and solutions from the outset. To enable economic growth and development, alongside environmental protection there should be a greater appetite for risk by proactively investing in asset health and infrastructure capacity in areas targeted for growth by local and national government.

Examples include Cambridge and Oxford, which have long been targeted for development. Proactive investment and early identification of solutions in these areas was undertaken preventing objections at planning stages. Both cities have ambitious growth projects and face significant challenges around water scarcity and wastewater infrastructure. In Cambridge, we are working with local partners to address water supply deficits through a new water credits system and major infrastructure projects like the Grafham pipeline transfer and Fens reservoir. In Oxford, a partnership between the Environment Agency and Oxford City Council has secured the infrastructure needed for the development of around 18,000 new homes, aligning with the Government’s ambition to unlock growth.

Essentially, we need a more forward-thinking approach that integrates environmental sustainability and proactive infrastructure investment to facilitate sustainable economic development. Upfront partnerships could form the blueprint to unlock projects nationwide where the right water infrastructure is needed before development can proceed.

Existing statutory WRMPs and new statutory DWMPs provide the understanding of evidence and investment need to future pressures from growth and climate change for water supply and wastewater assets and systems. In conjunction, the price review process should strengthen industry’s focus on future demand and statutory plans, building additional resilience and headroom into the system allowing it to adapt to changes over time.

3.2 Supporting infrastructure maintenance

A reformed price review process should reward proactive asset stewardship, not reactive fixes, by linking funding to long-term asset management strategies. It should require greater transparency on how base costs align with delivery risks, including evidence of past performance and future resilience.

Base expenditure needs to be treated as a strategic enabler of resilience, not just a routine operating allowance. This means shifting the review from “how much did you spend?” to “what condition are your assets in now and into the future, and how well are you ensuring they continue to meet obligations?” Long-term resilience relies on sustained maintenance, and the price review must make that visible and valuable.

Statutory DWMPs will provide the opportunity for companies to demonstrate ‘improvements from base’ in 2027/8, highlighting current and future investment in asset health, capital maintenance activities beyond enhancements. Transparency and accountability will be key.

3.3 Supporting infrastructure improvements

The sector’s failure to deliver on AMP7 (2020-2025) enhancement programmes, despite having received funding, has increased environmental risks. AMP8 plans (2025-2030) are more ambitious, aiming for greater enhancements, however, the same financial and operational constraints remain. Enhancement delivery is not just about regulatory approval, it’s also about ensuring financial viability. Many enhancement projects such as phosphorus removal or storm overflow infrastructure require significant upfront capital.

The gateway funding introduced by PR24 Final Determination will enable us to manage delivery risk for major enhancement projects. This funding mechanism aims to ensure that projects can be completed successfully and sustainably. Even with this gateway approach the need for better financial planning and risk management to achieve such an ambitious environmental programme remains. There may be a case for public-backed investment mechanisms (for example, a UK Water Infrastructure Bank or use of the National Wealth Fund) to support delivery especially where private investment appetite is weak but societal / environmental need is high.

3.4 Securing infrastructure delivery

The current incentive framework is largely reactive, and input focused. To secure long-term delivery, regulators should move toward a performance-driven model, where revenue is tied to outcomes, not just activity, and companies are rewarded for innovation and system transformation, not just cost efficiency.

To make performance incentives more effective in driving infrastructure delivery, we recommend the following changes:

- Outcomes not outputs: Stronger link between incentives and actual outcomes. Align Outcome Delivery Incentives (ODIs) and Price Control Deliverables (PCDs) with tangible improvements in asset performance and environmental quality, not just intermediate outputs.

- Real-time adjustment mechanisms: Introduce in-period adjustments (for example, quarterly or annually) to funding or allowed revenue based on delivery progress, rather than waiting until the end of an AMP. This could help respond to poor investment levels but also enable adjustment for economic shocks.

- Link incentives to financial behaviour: Introduce bonus/penalty escalation based on how companies use enhancement funding, for example, higher penalties where dividends are paid despite project under-delivery.

- Reward partnerships and efficiency: Include specific rewards for catchment-scale collaboration and cost-effective solutions that deliver multiple public benefits.

3.5 Changes to the New Appointments and Variations (NAVs)

The Environment Agency has statutory responsibilities to regulate New Appointments and Variations (NAVs) as water undertakers.

NAVs were set up to offer an alternative to the incumbent water companies by providing water and wastewater services for new housing developments, commercial and industrial sites, thus increasing competition in the water industry sector. They can connect to an incumbent’s existing water supply or wastewater treatment network or establish their own independent systems for water supply and/or wastewater treatment. The number of NAVs has risen significantly in terms of sites, companies and customers supplied.

For regulatory purposes NAVs are treated the same as incumbent water companies, assuming they meet standards of compliance, competence, and resilience unless proven otherwise. The regulatory effort required for NAVs is disproportionate to the risks they pose, or their environmental impact compared to incumbent water companies. Ofwat’s consultation on NAV-to-NAV transfers could exacerbate this issue, potentially increasing regulatory complexity. The following areas of regulation require review to ensure more effective oversight and management of NAVs:

- look at their exclusion from statutory water resources planning processes as there is little to no environmental benefit

- water supply NAVs can complicate communications and timings of customer restrictions (‘hosepipe bans’) during drought events

- water supply NAVs may miss out on important initiatives such as smart metering

- the Environment Agency is underfunded for NAV related water supply work as they generally do not hold water resources licences. Water industry regulation is funded via permits and licences

- there is limited compliance data to accurately compare the performance of NAV with that of the incumbent water companies. This lack of comparison data creates risks, especially when NAVs propose their own wastewater treatment systems that discharge into environmentally sensitive areas. Without reliable data, it’s challenging for us to ensure that these new systems won’t harm the environment

Potential solutions which could improve this situation include:

- update the NAV statutory definition which would enhance customer protections and reduce industry uncertainty

- NAVs should input to the incumbent’s water resources plans which would improve communication, ensure alignment between companies, and reduce regulatory administrative burdens

- incumbents to become responsible for advertising customer restrictions for all NAVs appointed within their area providing more comprehensive coverage during droughts

- having a minimum size definition for NAVs would ensure efficient use of resource and reduce administrative burden

- improve the licensing process

- look at how their performance is regulated, for example, comparative performance metrics (EPA etc), how competition works, governance and resource investment

4. Water industry public policy outcomes

4.1 Review and consolidation of legal and/or regulatory requirements

The current legislative landscape that regulators and the regulated water industry must work within is complex and layered with inconsistencies between the protections, powers, duties, requirements and charging frameworks.

A comprehensive, strategic government approach that aligns land use, flood management, climate adaptation, and water regulatory policies could enable a more holistic and effective framework. This would require a policy framework that incorporates:

- outcome-focussed legal drivers addressing the most significant and opportunities facing our water environment

- stronger legal incentives to target issues at source – not merely addressing symptoms

- an emphasis on ‘compliance by design’ - an approach that minimises reliance on monitoring and measuring within the environment, instead prioritises policies and permissions that proactively establish and drive standards

- an approach that retains the core purpose of water industry investment and requirement for long-term strategic water resources and wastewater plans (i.e. WRMPs and DWMPs)

Water companies are licenced to operate under licence conditions and statutory duties set out in the Water Industry Act 1991. To improve effectiveness of the regulatory functions, a fundamental review of the Water Industry Act 1991 would be beneficial to provide a clearer distinction between economic, environmental and sustainability statutory duties against which the regulators can enforce. As stated earlier in the response, a new fundamental legal duty on the water companies to cooperate with all regulators, as well as a legal duty to implement, invest appropriately and comply with relevant environmental legislation would reduce regulatory burden and increase confidence in investment delivery.

Without action there could be a public water supply deficit of up to 4,500 Ml/d (mega litres per day) by 2050. To meet this deficit requires a shift in strategies for valuing water by considering the true cost of water for social, economic and environmental needs, and using water more efficiently to ensure its long-term availability.

Further strengthening of environmental legislation could give clarity to developers and industry of the requirements to evaluate the benefits that nature provides to people and the economy. This could be achieved by updating the Water Environment (Water Framework Directive) Regulations with a view to reducing administrative burden while maintaining the high level of environmental ambition. The legislation should include safeguards for habitats, species and natural function to protect ecosystem services. This legislation needs to be supported by corresponding levels of funding for regulation by public bodies.

Case study: Layers of legislation for regulation of wastewater

The main issue of concern with phosphorus in the water environment is freshwater eutrophication. This is the adverse effect on water uses and ecology of excess algal/plant growth caused by excessive nutrient enrichment. Eutrophication is an international concern and has been recognised as an issue in England and Wales, particularly in fresh waters, since the 1990s.

Phosphorus concentrations in our rivers increased significantly between 1950 and the 1980s due to the introduction of phosphorus-based detergents, population growth and the growing use of artificial phosphorus fertilisers. Wastewater treatment and other measures have reduced phosphorus significantly since 1990. The phosphorus loadings to rivers in England and Wales from water company Wastewater Treatment Works (WWTWs) were reduced by more than half between 1995 and 2010 and by 66% to 2020 through the introduction of further phosphorus reduction treatment.

There have been reductions in agricultural fertiliser phosphorus inputs to land over recent decades (since the 1980s). This is related to improved manure use, plateauing of yields and economic pressure, including the cost of fertiliser. There has however, been a surplus of phosphorus applied to agricultural land over the last 70 years that has created large ‘legacy’ reserves of phosphorus in the soil which contribute to the risks of pollution. Agriculture and rural land management has now overtaken water industry WWTWs as the most common cause of water bodies not achieving good status for phosphorus.

Overtime we have seen layers of legislation introduced that has complicated the regulation of WWTWs in relation to the permitting and compliance for phosphorus associated with the different legislative requirements.

Outlined below is a summary of the legislation introduced which has given rise to phosphorus limits being introduced into permits at WWTWs.

1994: The introduction of the Urban Waste Water Treatment Regulations (UWWTR) brought in phosphorus emission standards of 1 mg/l or 2mg/l for qualifying WWTWs discharging to sensitive areas affected by eutrophication.

1994: The Habitats Regulations (HR) implementing Habitats Directive give a higher level of legal protection to designated Special Areas of Conservation sites with targets such as phosphorus set for the water environment by Natural England.

2009: Standards for phosphorus in UK rivers and lakes were introduced under the Water Environment (Water Framework Directive) Regulations (WFDR) in 2009 and the river standards were updated in 2015. These aim to prevent and limit eutrophication.

2023: The Environmental Targets (Water) (England) Regulations (ETR) introduced a national waste water target for reducing the phosphorus load discharged from WWTW under the Environment Act 2021. The load of total phosphorus discharged into freshwaters from relevant discharges is, by 31st December 2038, to be at least 80% lower than the baseline of 2020.

The HR, WFDR and ETR require that phosphorus limits set at WWTW to ensure the relevant environmental standards and targets are met. These are calculated using water quality modelling to set what are termed river needs limits.

2023: The Levelling Up and Regeneration Act (LURA) introduces nutrient standards for certain WWTW in qualifying catchments. For phosphorus an emission standard of 0.25 mg/l is applied for those WWTWs.

Permits can now require up to four different phosphorus limits (UWWTR, HR/WFDR, ETR and LURA) to meet this range of legislative requirements increasing the complexity of water quality planning and regulation. Differences in how monitoring and compliance are undertaken adds to the regulatory burden for both the water companies and the Environment Agency. For example, the UWWTR requires composite sampling at WWTWs while spot sampling is required for WFDR so requiring two sets of monitoring to be carried out. The emissions standards for the UWWTR and LURA are set in legislation as is the composite sampling requirement for the UWWTR so the Environment Agency has no regulatory flexibility in how these are applied.

We would advise a review of these different legislative requirements with the aim of the rationalising and consolidating the requirements where possible to simplify the regulation while still achieving the environmental outcomes.

4.2 Innovation and technology

4.2.1 Need for innovation in the water sector

Research and innovation are part of the solution for future water security and environmental protection. New technology can be transformative, but there are systemic barriers to innovation in general.

As the environmental regulator we support innovation with appropriate safeguards. We want to see innovation which develops and shares evidence to mainstream new technologies across the sector. We observe a lack of evidence in sharing innovation between companies.

Compounding this is a water sector where productivity has stagnated (Flash productivity by section - Office for National Statistics). Research and development (R&D) investment has been historically low (Ofwat’s emerging strategy: Driving transformational innovation in the sector (2019); Frontier shift at PR24-05-04-23-STC (2023)) compared to other infrastructure sectors.

We welcome steps Ofwat has taken in PR24 to drive innovation through its innovation fund approach. But, without proper evaluation, and given the poor productivity and persistent environmental problems, it is crucial to question whether the current R&D model is effective or whether innovation is primarily driven through systemic, regulatory-driven change. If so, this isn’t just a missed opportunity, it’s a systemic failure. Without collaborative innovation pollution persists, costs rise, and the sector stays locked in reactive, high-carbon infrastructure cycles.

4.2.2 Coherent, flexible and agile regulation to support innovation

The Government’s New approach to ensure regulators and regulation support growth policy paper has a vision for a regulatory system that ‘adapts to keep pace with innovation’. We recommend the following changes to help support innovation and raise confidence in the water industry sector:

- a clear policy landscape that signals the required changes with suitable lead-in times for trials and R&D allowing room for companies to adapt

- better understanding of the current and future risks

- open discussion about the challenges where innovation could help deliver improvements

- link innovation to performance and reward outcomes

- allow “sandbox” environments to reduce regulatory and legal risk when testing new technologies

- promote systematic technological change in the water sector not incremental

- expand innovation funds with clearer pathways to business adoption

- embed innovation into price review outcomes as part of core delivery

Better root cause understanding of the environmental problem and associated trade-offs would stimulate the right innovation. A simpler, more coherent, flexible and agile regulatory framework would support innovation. Greater flexibility would remove regulatory barriers so investment can be made in innovation to meet the future challenges.

Our Chief Regulators Report 2023-24 sets out that good and effective regulation provides confidence for investment, innovation and development. Our ambition is to be a proactive, forward-looking regulator that is prepared for the future and the changes it may bring. Horizon scanning and futures tools helps the Environment Agency understand and adapt our future operating context to emerging risks and opportunities. We need to understand and take advantage of new technologies and processes to regulate them effectively.

Recommendation 10 from the independent review of Defra’s regulatory landscape – the Corry Review - supports setting up “a programme of experiments or sandboxes” to stimulate a culture of experimentation and permission without undue risk, whilst avoiding any harm to the environment. We welcome this and will support Defra with their development of this recommendation, including exploring what can be done within current legislation and where Defra would need to make any legislative changes.

Regulatory clarity is essential for enabling innovation, and the regulatory framework must be designed to support allow it. While we do not have the power to amend or create regulations, we can adjust how we implement them where the regulatory framework allows us. As the regulator we need confidence in innovation. This involves assessing the acceptable environmental risk on the environmental receptors, considering any impact (time and spatial) and ensuring the trial risks are minimised. Operators need to demonstrate that the innovation works, and they can comply with regulatory conditions. Where an innovation is not performing as expected, contingency actions are needed to protect the environment.

Case study: Nutrients System

Maximising the value and benefits within a nutrient system approach would improve the environment, allowing nature to recover and create capacity for sustainable growth supporting the Government’s Economic Growth Mission.

As a country we need an end-to-end view of the nutrient cycle, setting out how a true circular economy can be achieved, by assigning producer responsibilities, prioritising nutrient recovery over nutrient disposal and ending the practice of excessive nutrient loading to agricultural land. This would require an integrated systems approach where the provision and use of nutrients intersects, including food production, waste treatment, and agricultural and environmental compliance, covering air, land and water environments.

For example, farm nutrient balances which only allow farmers to produce and receive the nutrients needed to produce the food that leaves the farm, or greater producer responsibilities where producers of nutrient wastes could be regulated or charged for the excess. A shift in the approach to management of nutrient levels in wastewater treatment sludge could set targets for nutrient recovery.

There are costs and benefits in moving to a circular economy for nutrients. Costs include investment in phosphorus recovery technology and innovative solutions. Benefits include reducing unsustainable phosphorus mining, environmental improvement and nature recovery.

Water reform provides a timely opportunity to stimulate innovation to create markets to improve disposal routes for nutrient wastes and to stimulate growth in technology and innovation in phosphorus recovery.

4.2.3 Regulation using Artificial Intelligence (AI)

Current legislation is generally outcome-focused and agnostic to specific methodologies and technologies. Essentially, environmental regulations do not restrict the use of AI by regulated entities, as long as they can demonstrate and provide evidence of compliance with existing legislation. Sector-specific guidance will be necessary for different AI applications, and we are collaborating with experts across regulated sectors and AI experts to develop specific guidance. In addition, we are working across regulatory bodies to develop and ensure complementary approaches, and with industry and academics to establish agreed-upon standards through, for example, the UK AI Standards Committee and the Robotics and Automated Systems Standards and Ethics Committee.

4.2.4 Innovation and Price Review

We are actively engaging the water industry on embedding innovation across its activities. Through PR24 we introduced the ‘Advanced WINEP’ initiative encouraging companies to set up partnerships to co-design, co-deliver and co-fund WINEP options offering better value and securing wider benefits for the environment and customers. Examples include:

- Anglian Water’s partnership for regeneration and resilience to establish best practice for partnership working across the water industry to enable wider environmental and social outcomes (£26 million + 70% co-funding)

- United Utilities’ rainwater management partnership to develop an Integrated Water Management Plan to make a material change to the drainage of Greater Manchester by removing a minimum of 62 hectares of impermeable area (£197 million + 20% co-funding)

Through the WINEP roadmap, we are looking ahead to future investment rounds to make sure they achieve the best environmental improvements for every pound invested. We want to encourage innovation and continue the move towards more catchment and nature-based solutions, where appropriate.

4.2.5 Infrastructure and supply chain resilience and security

The Environment Agency currently owns and operates 3,563 assets, with a replacement cost of £841 million, to transfer and manage water. This infrastructure supports abstractions for public water supply to approximately 7 million people (11% of the population of England), providing a minimum of 2,112 Ml of water per day, when required.

Future ownership and investment for the maintenance and resilience of these assets should be considered as part of a broader review of strategic water infrastructure and resilience. A step change in capital investment is needed to ensure that these assets are fit for the future and able to deal with future challenges including climate change and increased demand. Whoever owns and operates these assets must be capable of ensuring equitable access to water and be able to secure the necessary capital and revenue investments.