Cyber security of consumer IoT - manufacturer survey

Published 5 December 2024

Executive summary

In the context of a growing market for consumer Internet of Things (IoT) products and an increasing risk of cyber attacks, consumer IoT products can be exploited to cause harm to individuals, companies, government, and society at large. In response, the UK Government introduced the world’s first legislation on the cyber security of consumer connectable products: the Product Security and Telecommunications Infrastructure (PSTI) Act 2022 and the PSTI Regulations 2023.

Prior to the entry into force of the PSTI Regulations 2023 on 29th April 2024, the UK Government’s Department for Science, Innovation and Technology (DSIT) commissioned this study, which aimed to:

-

Map and analyse the market for consumer connectable products; and

-

Collect and analyse evidence on the compliance of manufacturers with the PSTI legal regime, as well as evidence on awareness and impacts of the legislation.

To achieve these aims, the project team from DJS Research and the Centre for Strategy & Evaluation Services (CSES) used a combination of research methods. Desk research was used to map the UK market for consumer connectable products, and collect available market data. This desk research was facilitated by data from two external data sources: Copper Horse and Beauhurst. The desk research was supplemented by a quantitative telephone survey to collect primary data from manufacturers. Given the challenges in reaching manufacturers, the survey was supplemented by a second round of desk research to assess publicly available evidence of manufacturer compliance with the PSTI requirements. Finally, we conducted qualitative interviews with manufacturers and industry associations.

However, the research process faced significant challenges, impacting the robustness and generalisability of the findings:

-

Mapping the UK market for consumer connectable products: the main challenges included the scale of products available on online third-party marketplaces, and the availability and quality of data, in particular, information on the size of the manufacturers (turnover and employee numbers).

-

Surveying the manufacturers; the main challenge was engaging manufacturers. A lack of contact information made it difficult to reach companies, while it was often difficult to find the right person. Finally, when the right person was identified, some companies were reluctant to participate due to concerns about the potential repercussions of demonstrating a lack of compliance (despite reassurances to the contrary). Therefore, less than 10% of the manufacturers initially mapped engaged in the research (33 of 394).

Chapter 2 (Methodology) further details these challenges and the mitigation measures implemented.

Analysis of manufacturer compliance levels and challenges

A key finding from the consultations with manufacturers and industry representatives was that the security requirements themselves are generally straightforward to implement. There was only one exception: the requirement to provide transparency on the length of time security updates are provided. Moreover, industry representatives strongly agreed with the need to introduce baseline security requirements for consumer connectable products. Respondents appreciated the approach of phasing in a selection of requirements, within the broader context of the UK Code of Practice for Consumer IoT Security and ETSI EN 303 645.

Regarding current compliance levels, the quantitative survey found the highest levels of compliance with the requirement to provide information on how to report security issues: 58% (19/33) of manufacturers consulted have already introduced the requirement for all products. The second highest levels of compliance were found for the provisions on passwords, implemented by 52% (17/33), while compliance with requirements on information about minimum security update periods was lower: only 27% (9/33) of manufacturers have already introduced this requirement for all products. However, 39% (13/33) reported that they intend to introduce the requirement within a certain time frame.

The current status of compliance, as reported by the surveyed manufacturers, is demonstrated in the below figure.

Figure 1: Compliance status for each of the three requirements (Question 6, Base: 33)[footnote 1]

| Compliance status | Passwords | Public point of contact | Security updates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Introduced for all products | 52% | 58% | 27% |

| Introduced for some products | 12% | 0% | 6% |

| Looking to introduce within a certain time | 9% | 24% | 39% |

| Looking to introduce in the near future but not sure when | 12% | 18% | 21% |

| Not looking to introduce for some products | 3% | 3% | 3% |

| Not looking to introduce at all | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| This requirement is not relevant to us | 18% | 3% | 21% |

These findings were also validated through an in-depth desk research exercise. Examining a subset of 70 companies, we attempted to assess evidence of manufacturer compliance based on publicly available information. Here, we found similar levels of compliance with the provisions on passwords: 46% (32/70) were already compliant or somewhat compliant with the new password provisions. Compliance with the requirement to provide information on how to report security issues was slightly lower: only 33% (24/70) of the sample showed publicly available evidence of compliance, contrasting with the 58% (19/33) compliance rate found in the quantitative survey.

The third security requirement – information on minimum security update periods – was more difficult to assess due to a lack of clear information: for 49% (34/70), we were unable to find whether the companies had published relevant information. These differences further highlight the difficulty of assessing compliance, and the generalisability challenges of the quantitative survey findings. In this context, challenges related to the overarching regime have resulted in compliance processes that are more complex, uncertain and costly than anticipated:

-

Product scope: Manufacturers reported uncertainty regarding which products are within scope. For instance, many were unsure whether products that can connect to internet-connected devices via Bluetooth, or products that can manage multipoint connections were in scope. They were also unsure about products that are sold business-to-business (B2B) but used by consumers.

-

Requirement for information on minimum security update periods: Manufacturers reported challenges indicating a minimum support period for each product, given the impacts of complex, global supply chains and minor differences with the requirements anticipated in the EU Cyber Resilience Act (CRA).

-

Timelines for implementation: The most prominent concern of manufacturers and industry associations related to the implementation timeline. Under the current scenario, stakeholders raised a significant risk that existing stock may need to be scrapped or recycled due to the fact that the legislation applies to products that are ‘made available’ rather than ‘placed on the market’ and the resulting need to retrospectively ensure compliance of products that are already in the supply chain and the market.

-

Demonstrating compliance: Despite the minimum information required for statements of compliance (SoC) being set out in Schedule 4 of the PSTI Regulations 2023, manufacturers reported uncertainty and challenges regarding the required content and form of the SoC.

In this context, many respondents highlighted that ensuring compliance was still an ongoing process. Moreover, manufacturers noted that these challenges increase the scale of the activities they need to take to ensure compliance, as well as the associated costs of compliance.

The quantitative survey asked manufacturers how likely they are to be compliant with each requirement by 29th April 2024. As illustrated in the below figure, most manufacturers consider that they are either ‘Very likely’ or ‘Quite likely’ to be compliant with each of the requirements (at least 85% for each requirement).

Figure 2: Likelihood of being compliant with each security requirement by 29th April 2024 (Question 14, Base: 33)

| Likelihood of being compliant | Very likely | Quite likely | Quite unlikely | Very Unlikely | Don’t know |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Passwords are unique, not guessable or based on incremental counters | 76% | 9% | 0% | 3% | 12% |

| The manufacturer provides a public point of contact to enable security issues to be reported | 85% | 0% | 3% | 6% | 6% |

| Information on the minimum length of time for which security updates will be provided must be made available | 64% | 24% | 6% | 0% | 6% |

Compliance activities, costs and other impacts

The main activities manufacturers have taken or plan to take to ensure compliance with the legislation included familiarising themselves with the legislation (87%, 27/31) and preparing a self-declaration/assessment of compliance (81%, 25/31). Manufacturers have also obtained legal advice (68%, 21/31); conducted or plan to conduct third-party testing (52%, 16/31); undertaken or will seek to undertake a formal third-party compliance assessment (42%, 13/31); and amended compliance information at the point of sale (48%, 15/31).

While difficult to quantify, the consulted manufacturers noted that they had already incurred, and anticipate incurring additional costs to comply with the legislation. The compliance costs stem from the abovementioned activities and the cost of additional staff, as well as anticipated action needed to deal with non-compliant stock (i.e. dispose, recycle or pivot to non-UK markets). Manufacturers expect to have to absorb some of those additional costs themselves, but are likely to pass on other costs to consumers and retailers.

Manufacturers also stated concerns that the time, effort and costs required to implement the legislation and the possibility of future regulatory divergence with EU legislation in this field could have a negative effect on industry innovation and competitiveness. In addition, they expressed concerns regarding the environmental impact of certain regulatory decisions. These were mainly due to concerns around the possible need to dispose of stock that is already on the market and cannot be made compliant, as well as the use of paper instead of digital SoC.

Notwithstanding the above, manufacturers and consumers are expected to experience significant benefits as a result of the legislation. At the manufacturer level, these include improvements in: product security; cyber security; consumer confidence in connectable products; customer satisfaction and loyalty; and reputation of products and manufacturers.

Moreover, significant indirect benefits for both consumers and businesses can be expected through improved resillience to cyber attacks and a reduction in the costs / impacts of cyber attacks.

Awareness of the PSTI regime

Almost all manufacturers surveyed were aware of relevant regulations on cyber security: 91% of manufacturers surveyed (30/33) stated they were aware of UK cyber security regulations related to consumer connectable products. They were slightly less certain when prompted with regard to specific regulations, including the PSTI Act 2022, the PSTI Regulations 2023, ETSI EN 303 645 and ISO/IEC 29147: 2018 on vulnerability disclosure. Yet overall, awareness of even specific provisions was high: 76% of manufacturers (25/33) reported being fully aware of the specific provisions of the PSTI Act and Regulations, with a further four stating that they were partially aware.

Considering manufacturers’ sources of information, most of those who were moderately aware reported having received information from industry or trade bodies (48%, 14/29), UK Government public consultations (28%, 8/29), and/or internal legal, compliance or product security teams (21%, 6/29). Similar responses were given when respondents were asked how they planned to make themselves aware of future regulations.

These results indicate that manufacturers may under-utilise available mechanisms of acquiring information. For instance, only 3% (1/29) stated that they engage with past government research; 7% (2/29) proactively track relevant legislation, and 15% (4/29) engage directly with the UK Government.

Analysis of consumer connectable product market

Within the market research task, a total of 394 manufacturers, 416 brands and 1,024 consumer connectable products were mapped. These were disaggregated to the extent possible by the following variables:

-

Product types: The most common types of products included safety and security (22%, 225/1024 products) and lighting products (11%, 117 products), followed by smart home (10%, 98 products), kitchen appliances (7%, 75 products), audio (7%, 70 products), health, fitness, and wellbeing (6%, 65 products), wearables (6%, 59 products), environmental control (6%, 59 products), and home appliances (4%, 42 products).

-

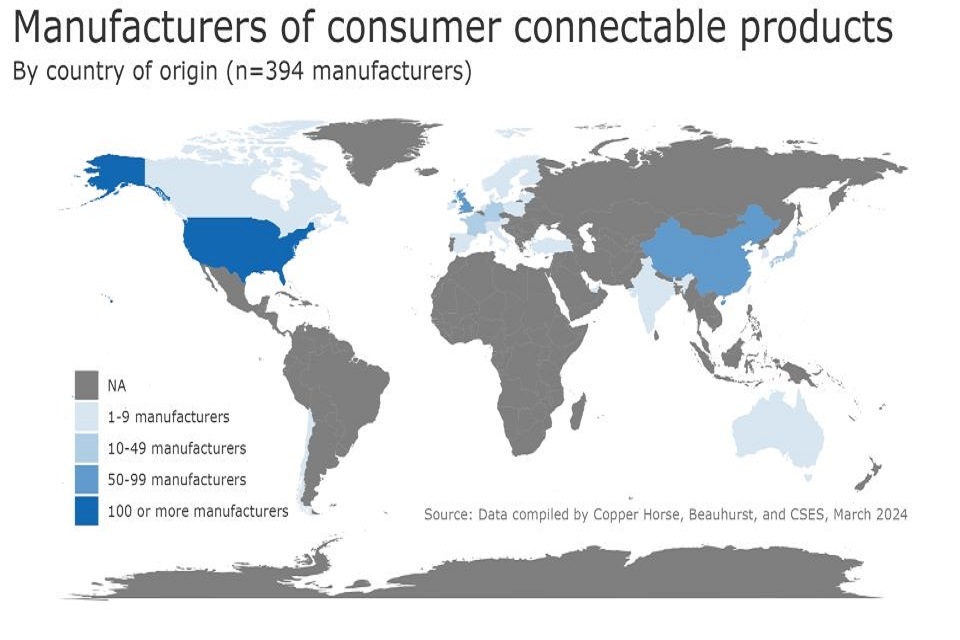

Geographical location: Just over half of the products were either manufactured by US (28%, 283 products) or Chinese companies (25%, 254 products), with around 15% (141) manufactured by UK companies. The remaining products came from Germany (7%, 69 products), Japan (4%, 44 products), the Netherlands (4%, 37 products), France (4%, 39 products), and other countries.

-

Manufacturer size: The majority of manufacturers in the sample were large: 37% (145 manufacturers) were large companies with 250 or more employees; 21% (82 manufacturers) were medium-sized companies with 50-249 companies; 20% (80 manufacturers) were small companies with 10-49 employees; and 8% (32 manufacturers) were micro companies with 1-9 employees. We were unable to find information on the size of the remaining 14% (55 manufacturers).

-

Manufacturer turnover: Just under one third (29%, 114 manufacturers) of manufacturers had a turnover of more than £50 million; 15% (60 manufacturers) had a turnover between £10 and £50 million; and around 22% (87 manufacturers) had a turnover below £10 million. We were unable to find information on the turnover of the remaining 34% (133 manufacturers). Because information is more likely to be publicly available for larger firms, we suspect that many of the companies we were unable to find information on are smaller, both in terms of employees and turnover.

-

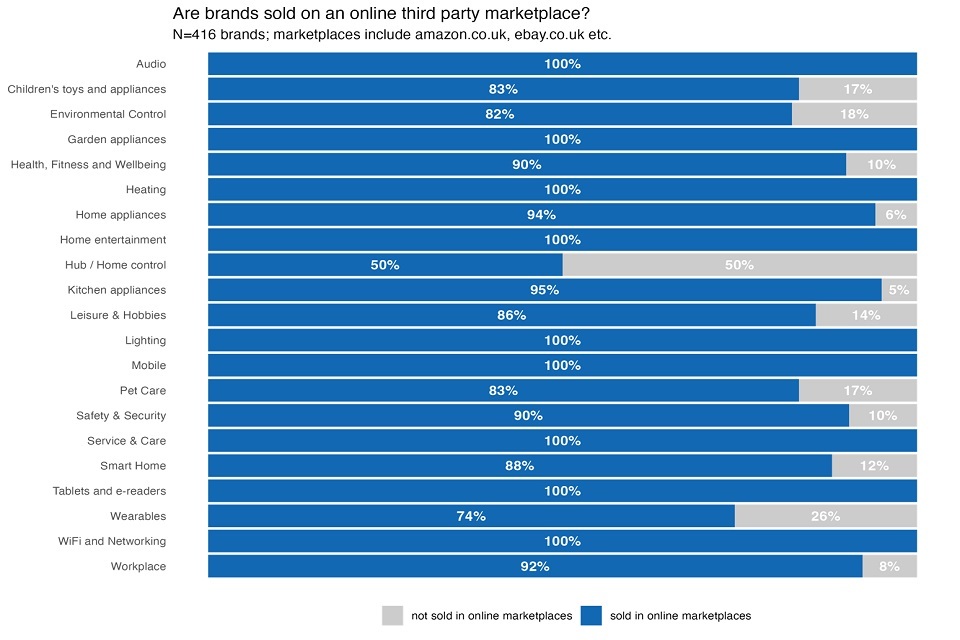

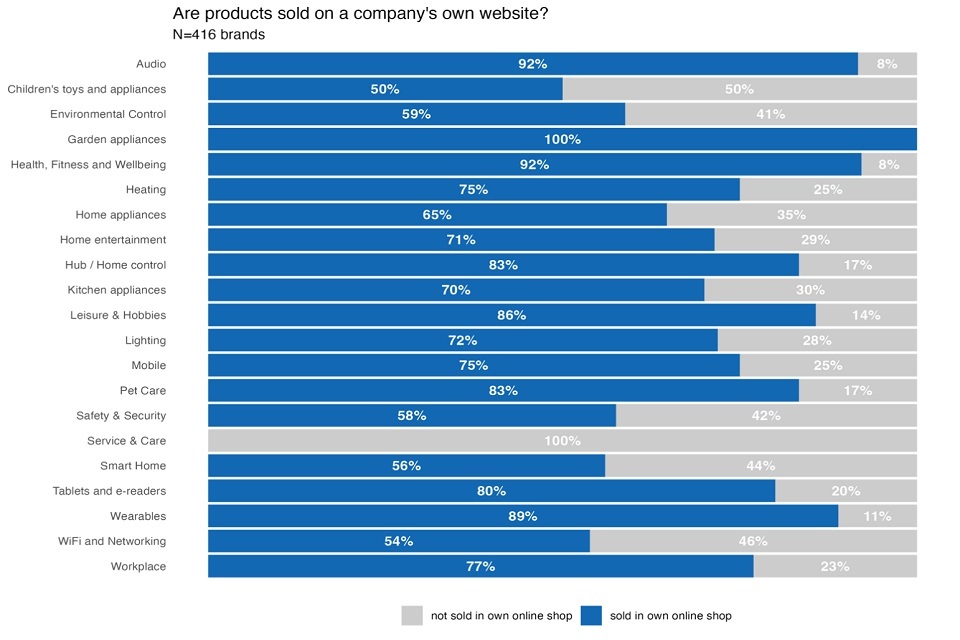

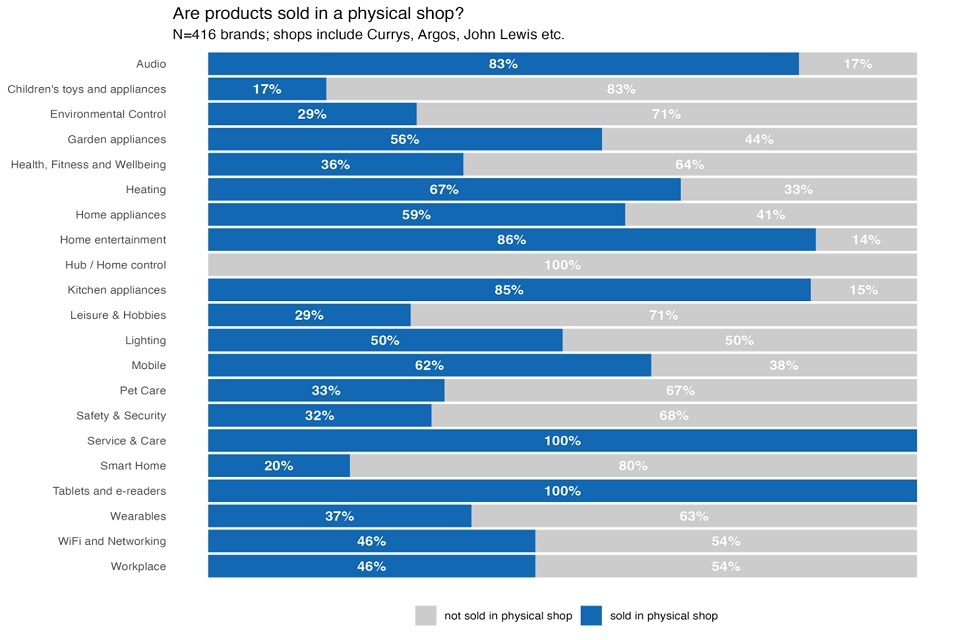

Routes to the market: The overwhelming majority of manufacturers use online shops to sell their products. Because some manufacturers own more than one brand, the following statistics are based on the total population of brands, not manufacturers: 88% (368 brands) are sold on online third-party marketplaces like amazon; 72% (299 brands) are made products available in the UK through company’s own online shop. Physical shops were somewhat less common: 45% (186 brands) are sold in a third-party physical shop; 9% (38 brands) are in companies’ own physical shops.

In this context, key trends and challenges within the UK market for consumer connectable products include that companies are entering and exiting the market relatively quickly, the general impact of Brexit and the anticipated risk of regulatory divergence with the EU, as well as the important roles of online third-party marketplaces and Chinese manufacturers in the market, even when acting as OEMs/ODMs.

1. Introduction

This research report presents the results of the project “Manufacturer Survey in Relation to the Cyber Security of Consumer IoT in the UK”, commissioned by the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology (DSIT) and conducted by DJS Research and the Centre for Strategy & Evaluation Services (CSES) from November 2023 to April 2024.

1.1 Project background and context

The number of consumer Internet of Things (IoT) devices on the market is rising and the number of cyber-attacks on such devices is also increasing. To address this challenge, the UK Government introduced the Product Security and Telecommunications Infrastructure (PSTI) Act 2022 and the PSTI Regulations 2023. This regime builds on long-standing non-legislative initiatives, including the UK Code of Practice for Consumer IoT Security, the European standard on the Cyber Security for Consumer IoT (ETSI EN 303 645) and the work of the National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC)[footnote 2]

The growth of the consumer IoT market

IoT (‘or smart’) devices are on the rise. YouGov (2022) estimates that 1% of UK adults own a (voice-activated) smart kettle, 2% own a smart thermostat (allowing users to control heating from their phone), 3% own a smart security product such as a motion camera sensor to monitor activity around doors and windows, and 11% own a smart speaker. Ofcom (2023) reports even higher numbers for certain types of device (e.g. 40-50% of UK consumers own a smart speaker), while recent research commissioned by DSIT on device ownership amongst individuals found that 64% of surveyed consumers own a smart TV.[footnote 2]The types of ‘products’ that are being connected to the internet is continuously growing. Amongst many others, connected versions of door locks, children’s toys, washing machines, and refrigerators exist, alongside larger products such as cars, scooters and drones.

Foreshadowing future trends, nearly 40% of YouGov’s respondents agreed that smart appliances made their life easier. As a result, the expected economic value of IoT is rising rapidly. McKinsey research from 2017 estimated that 127 new devices are connected every second, with the potential to generate USD 4-11 trillion in economic value by 2025 (albeit including non-consumer IoT). More recently, Statista estimated in 2020 that each UK household had an average of nine IoT devices, with 2022 research estimating that the total number of consumer IoT connected devices worldwide will exceed 17 billion in 2030.

The cyber challenge for IoT devices

While consumers have come to see IoT devices as part of their everyday lives and assume they are secure, the number of cyber-attacks is increasing. IoT devices often lack even minimum levels of security and can act as low-hanging fruit for cyber attacks. Cyber security experts at Kaspersky found that attacks targeting IoT devices (including consumer, business and industrial devices) doubled between 2020 and 2021, allowing access to sensitive user data and potential for further exploitation.

According to Kaspersky, the two most prominent methods used to infect IoT devices are to crack weak passwords and to exploit vulnerabilities in network services. In a 2022 study for Which?, a team of ethical hackers seeking to disclose security issues in IoT devices in the UK were able to hack dozens of test devices, including a smart doorbell, a smart speaker/hub, a smart TV, and a smart baby monitor.

The UK product security regime

Prior to the introduction of the PSTI Act 2022 and PSTI Regulations 2023, the UK Government took steps to tackle the cyber security challenges facing IoT devices, the most prominent of which are explained in the below box.

Table 1: Summary of policy actions leading to the adoption of the PSTI legal regime

The UK Code of Practice (CoP) for Consumer IoT Security was published in March 2018 as part of the Secure by Design report. The CoP was developed by the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS), in conjunction with the NCSC and cyber experts, on the basis of a mapping of IoT security recommendations, guidance and standards. The CoP aimed to support all entities involved in the design, development, manufacturer and retail of consumer IoT devices by outlining 13 outcome-focused guidelines based on good practice in IoT security.

Following the publication of the CoP, the European Standards Organisation ETSI[[footnote 4] launched the first globally applicable industry standard on internet-connected consumer devices in February 2019 (ETSI Technical Specification 103 645). This was complemented in June 2020 by European standard EN 303 645 on the Cyber Security for Consumer IoT, which established 13 security baseline requirements for such devices, mirroring the CoP.

Alongside the development of the European standard, the UK Government continued to investigate the best way to regulate the issue, with extensive research commissioned on the nature of the challenges, the regulatory possibilities and the anticipated impacts and costs of such interventions.[footnote 5]

On this basis, and within the context of the National Cyber Strategy 2022, the UK Government introduced a product security regime for consumer connectable products that aims to protect individual privacy and security and guard citizens, networks, and infrastructure against cyber-attacks. The regime consists of two key pieces of legislation:

-

The Product Security and Telecommunications Infrastructure Act 2022 (PSTI Act), which requires manufacturers, importers, and distributors of consumer connectable products to comply with new security requirements, establishes the enforcement mechanisms and creates civil and criminal sanctions to prevent unsecure consumer connectable products from entering the UK market. It was introduced in November 2021 and came into force in December 2022.

-

The Product Security and Telecommunications Infrastructure (Security Requirements for Relevant Connectable Products) Regulations 2023 (PSTI Regulations) specifies the security requirements. It was made in September 2023 and comes into force on 29th April 2024.

Different terms are used to describe these devices: the terms ‘smart’, ‘IoT’ or ‘connectable’ products are used interchangeably. The PSTI Act (s 5) uses the term ‘connectable’ products, defining an ‘internet-connectable’ product as ‘capable of connecting to the internet’, and a ‘network-connectable product’ as one that is ‘capable of sending and receiving data by means of a transmission involving electrical or electromagnetic energy’. ‘UK consumer connectable products’ are defined as internet or network-connectable products that are made available to consumers in the UK.

The PTSI Act places a duty on manufacturers of consumer connectable products that are or will be sold in the UK to comply with security requirements (s 8) and to ‘take action’ if they become aware (or ought to be aware) that a product does not comply with a relevant security requirement (s 11). In case of a ‘compliance failure’, manufacturers are to ‘take all reasonable steps’ to ‘remedy the compliance failure’. Manufacturers must also notify importers, distributors and any other manufacturers they are aware of, and if necessary, stop sales and inform consumers. Manufacturers must also keep a record of any compliance failures, or investigations in relation to a real or suspected compliance failure for a period of 10 years (s 12). Similar rules apply to importers (s 14-20) and distributors (s 21-25) of consumer connectable products. Chapter 3 references the enforcement actions, including compliance, stop and recall notices, as well as monetary penalties; Sections 36-38 enable the Secretary of State to give maximum fixed monetary penalties of GBP 10 million or 4% of worldwide turnover, in addition to daily penalties of up to GBP 20,000 for each day for which the relevant breach continues after the end of the period specified for payment of the fixed penalty.

The specific security requirements are set out in the PSTI Regulations 2023. They apply to both the hardware and the associated software of the consumer connectable product and include requirements regarding:

-

Passwords, which must be unique, not guessable or based on incremental counters.

-

Information on how to report security issues, which requires that manufacturers publish: i) information on at least one point of contact for reporting of security issues; and ii) information on when a person reporting an issue will receive acknowledgement of receipt of the issue report and when they will receive status updates until resolution.

-

Information on minimum security update periods, which requires that manufacturers must specify the minimum length of time for which the connectable device will receive security updates.

For the latter two requirements, the information must be accessible, clear and transparent (e.g. made available without prior request, in English, free of charge, and ‘in such a way that is understandable by a reader without prior technical knowledge’). Manufacturers must also prepare a statement of compliance (SoC) to accompany all consumer connectable products made available on the UK market.

The Regulations also list connectable products that are exempt from the regulatory regime: products for the Northern Irish market, charging points for electrical vehicles, medical devices, smart meter products, and tablets and computers (unless they are designed exclusively for children and young people under the age of 14) are exempt.

1.2 Research purpose, objectives and scope

The purpose of the project was to identify the compliance levels amongst manufacturers in the lead up to the PSTI Regulations 2023 coming into force on 29th April 2024, specifically by collecting information on current compliance levels and providing a baseline dataset that can be used in future monitoring and evaluation.

In this context, the research aimed to achieve two objectives:

-

Map and collect market data on manufacturers of consumer connectable products that make available or sell relevant products to UK consumers and are subject to the PSTI Act 2022 and PSTI Regulations 2023. This seeks to assess the number of manufacturers selling to the UK market and the types of consumer connectable devices produced, as well as the geographical location, turnover, number of employees, and routes to market of these manufacturers.

-

Collect evidence on compliance levels with the cyber security requirements stipulated in the PSTI Act 2022 and the PSTI Regulations 2023 amongst manufacturers, as well as evidence on awareness and the anticipated impacts of the legislation.

Considering the scope of the research, the following factors are important:

-

Consumer connectable products and manufacturers within scope align to the definition of consumer connectable products stipulated in the PSTI legal regime.

-

All manufacturers that sell or make consumer connectable products available to UK consumers are within scope, regardless of where they are based.

1.3 Report structure

This research report contains:

-

Methodology – Summary of the research methods used, as well as the challenges faced (Chapter 2).

-

Analysis of consumer connectable product market– Overview of the market for consumer connectable products (Chapter 3).

-

Analysis of PSTI awareness, compliance and impacts (Chapter 4).

-

Conclusions – Conclusions drawn from the research findings (Chapter 5).

These sections are supplemented by Annexes presenting a bibliography, data tables supporting the market analysis and the full results of the CATI survey.

2. Methodology

The following research methods were deployed to achieve the above objectives:

Quantitative telephone survey to collect primary data from manufacturers on awareness, compliance and impacts of the PSTI regime. As a result of the challenges experienced (detailed below), this survey was supplemented by targeted desk research to identify evidence of compliance with the three security requirements outlined in the PSTI Regulations 2023 across a sample of manufacturers.

-

Qualitative semi-structured interviews with manufacturers and industry associationsto complement the quantitative survey with more in-depth exploration of the research issues.

-

Desk research and liaison with an external data provider to map manufacturers of consumer connectable devices and collect relevant market data on that sample of companies.

Using the data collected through the above methods, the research team analysed the size, structure and dynamics of the UK consumer connectable device market (see Chapter 3), the awareness and compliance levels with the PSTI regime, and the impacts of the regime (see Chapter 4).

The approach to each method and the challenges faced are now presented.

Quantitative telephone/CATI survey

Based on the research objectives, DJS Research with input from CSES designed and scripted the computer assisted telephone interview (CATI) questionnaire. After the setup was complete, a series of quality checks were undertaken before fieldwork began.

An initial database of around 400 business records was used during the fieldwork. Due to various challenges with contacting non-UK businesses, DJS obtained support from experienced international partners to help contact around 150 overseas businesses from the list (more detail below).

At the start of fieldwork, a highly experienced team of business to business (B2B) interviewers was fully briefed on the project background and questionnaire.

The fieldwork lasted a total of ten weeks, starting on 10th January 2024 and ending on 20th March 2024.

The original intention was that the survey questionnaire should take an average of 15 minutes to complete. However, the interviews took between 30 and 70 minutes due to the depth of feedback interviewees were keen to provide. All interviews were conducted in English with senior individuals responsible for product cyber security.

A total of 33 responses were obtained from the quantitative survey. This comprised 32 telephone interviews and one online completion.

The final profile of interviewed businesses indicates a good spread of respondents by business size, location and product type:

-

Geographical location: Just under half (16) of the companies that participated have their headquarters in the UK, around a quarter in the rest of Europe (9) and the remaining quarter in the USA/Canada (6) or Asia (2).

-

Business size: Nine are micro or small employers (fewer than 50 employees), five are medium-sized employers (50-249 employees) and the remainder are large employers with 250 or more employees.

-

Range of products manufactured by the companies surveyed also varies considerably, with the majority producing a wide range of home and personal electronic appliances/devices (e.g. TVs, home cinemas, mobile phones and laptops) and white goods (e.g. washing machines, dryers, fridges and ovens), as well as products such as air conditioning and heating systems, security devices, cameras, smart watches, kettles/coffee machines, garage doors, mobility devices, lighting, navigation devices and audio equipment.

However, the research team faced significant challenges in the delivery of the quantitative survey. In line with the specification, DJS Research and CSES estimated that they would achieve up to 150 interviews in their proposal, albeit citing risks related to engagement and response rates. In practice, this proved challenging for the following reasons:

-

Lack of available and accessible contact information. Whilst CSES provided DJS Research with a detailed database of contacts, it was difficult and time consuming to find named contacts. DJS Research continued this activity after taking receipt of the contact database but encountered very similar issues. The majority of businesses either do not publish telephone numbers and/or email addresses on their company websites or provide generic contact details. In most cases, the only method of contact was submitting an online form (which was often targeted at technical support or general product queries). In the rare instances where it was possible to speak to a ‘gatekeeper’, they were often unsure who was the most appropriate person to contribute. We also found that several numbers went straight to answer phone, were unobtainable or were more designed for consumers to allow them to get through to a Customer Service/Technical helpline, rather than Senior Managers/Directors of the business.

-

Unwillingness or concerns about the potential repercussions if they indicated a lack of compliance in their reponse. Another key challenge experienced throughout the fieldwork was the unwillingness to participate. This appeared to be due to concerns about potential consequences if they disclosed a lack of compliance (despite reassurances that this would not be the case).

To address these challenges, the team implemented extensive mitigation measures, including: preparing and disseminating communication materials, including via DSIT channels, including via a supporting letter to manufacturers from DSIT, social media and established industry associations; amending interview staffing to ensure coverage of North American and Asian markets; and purchasing an additional database of named contacts.

Furthermore, it should be noted that, despite the relatively low number of interviews, the quantitative survey has provided a good cross-section and wealth of detailed information, supplemented with the depth interviews.

As the interview numbers remained low after implementing the above mitigation actions, DJS Research and CSES conducted an in-depth desk research exercise to assess compliance levels using the information provided on manufacturers websites. A data collection tool was developed in Excel and a pilot was conducted across 10 manufacturers to test the utility of the method and the availability of data. Once quality assured, reviewed and agreed with DSIT, a sample of manufacturers was chosen, and the researchers were briefed on the purpose of the activity and the research process.

With the aim of reaching a combined total of 100 businesses across the quantitative survey and the desk research, this activity was conducted for a sample of 70 businesses representing a balanced coverage of business sizes, geographical locations and product types.

Following the selection of the sample of manufacturers to be covered by the desk research exercise, the DJS and CSES researchers reviewed the websites of the manufacturers, including product descriptions for products within scope, terms of service, privacy and security information and other relevant documentation, to identify and assess evidence of compliance with each of the three security requirements stipulated in the PSTI Regulations 2023.

However, as this exercise was conducted prior to the entry into force of the Regulations, explicit references to compliance and key compliance documents (i.e. SoCs) were not found. Therefore, it is important to note that, as the research aimed to identify publicly available evidence of compliance, it was not feasible, in many cases, to provide a definitive judgement on compliance. Instead, each manufacturer was assessed against a scale of the level of evidence of compliance, accompanied by a qualitative description of the evidence identified. The following scale was used:

-

Strong evidence of compliance: Evidence identified of compliance with all elements of the security requirement.

-

Somewhat compliant: Evidence identified of compliance with at least one element of the security requirement, or indications of full compliance but formulated in a way that is unclear.

-

No evidence of compliance: No evidence of compliance identified.

-

Information not available: Limited or no information of relevance available.

Qualitative semi-structured interviews

The purpose of the qualitative interviews was to supplement the quantitative survey data through more in-depth discussions with both manufacturers and industry associations. These discussions should cover all key research issues, including market challenges, cyber security approaches, awareness of and compliance with the PSTI Act 2022, the PSTI Regulations 2023 and the ETSI standard, and the actual or anticipated impacts of the new legal regime.

DJS Research, with input from CSES, drafted and circulated two interview guides (one for manufacturers and one for industry associations).

With a target of 10-20 qualitative interviews, the original intention was to select and source manufacturers for more in-depth discussions following their participation in the quantitative survey. However, given the engagement challenges detailed above and the extent of the information provided through many of the quantitative survey interviews (which acted as combined quantitative and qualitative interviews), a total of nine additional semi-structured interviews were conducted: five with manufacturers and four with relevant representatives of industry.

Manufacturer mapping and collection of market data

The purpose of this activity was to map manufacturers of consumer connectable products selling into the UK and the products they sell, producing as complete a database as possible. Where available, additional data, including turnover, number of employees, geographical location, routes to market and contact details, were added. This required the following steps:

-

Step one: Define broad product categories and sub-categories. Building on previous research[footnote 6] CSES defined an initial list of product types and overarching product categories to be used in the dataset. These were consistently reviewed throughout the exercise based on new insights.

-

Step two: Develop a data collection matrix. To support the data collection and extraction process, CSES developed a matrix in which the key data for each manufacturer/product can be collated in a structured manner.

-

Step three: Review literature/data sources and extract relevant data on IoT manufacturers selling to the UK. Primarily, this focused on the open data developed through research conducted by Copper Horse for the IoT Security Foundation (IoTSF) on the state of vulnerability disclosure, but also other market research sources and literature identified through targeted desk-based research. The list of manufacturers prepared by Copper Horse was reviewed and edited to ensure the companies/products identified were in scope.

Step four: Conduct desk-based research to complete the matrix. This was achieved through three sub-steps: i) search key online / high street retailers to validate and enhance the Copper Horse/IoTSF open data, and ultimately identify

DSIT, with a third-party data provider (Beauhurst) to access company data on UK-based legal entities linked to manufacturers of consumer connectable products; and iii) review other data sources, such as web data (e.g. lists of members of IoT industry associations), Companies House registration data, LinkedIn and market research reports to complete the matrix for each manufacturer/product to the extent possible.

- Step five: Analyse the data to provide results on key indicators, including number of manufacturers, disaggregated by the following variables: product type/category, geographical locations, routes to market, number of employees, and turnover. The results of this analysis are presented in Chapter 3.

This exercise faced significant challenges, for instance related to the availability and quality of company data. These challenges, and the mitigation measures taken, are detailed in Chapter 3.

3. Analysis of consumer connectable product market

3.1 Market size and structure

Consumer connectable products sold in the UK

This section analyses the market of consumer connectable products mapped as part of the desk research. It begins with an analysis of the types of consumer connectable products sold in the UK, before it presents their manfacturers in more detail.

Figure 3 shows the number of consumer connectable products (n=1024) by type. Most products were categorised as ‘Safety & Security’ products (e.g. smart security cameras, video doorbells, or smart smoke alarms), followed by ‘Lighting’ products (e.g. smart light bulbs, or smart lamps), ‘Smart Home’ products (e.g. smart plugs, switches, or outlets), ‘Kitchen appliances’ (e.g. smart dishwasher, smart coffee machine), ‘Environmental control’ products (e.g. smart air conditioning), and ‘Health, Fitness, and Wellbeing’ products (e.g. smart body scales, or smart water bottles).

Figure 3: Consumer connectable products sold in the UK, by category (n=1024 products)

| Safety & Security | 22% |

| Lighting | 11% |

| Smart Home | 10% |

| Kitchen appliances | 7% |

| Audio | 7% |

| Health, Fitness & Wellbeing | 6% |

| Wearables | 6% |

| Environmental Control | 6% |

| Home appliances | 4% |

| Home entertainment | 3% |

| Heating | 3% |

| Tablets and e-readers | 2% |

| WIFI and Networking | 2% |

| Mobile | 2% |

| Workplace | 2% |

| Pet Care | 2% |

| Garden appliances | 1% |

| Leisure & Hobbies | 1% |

| Hub/Home Control | 1% |

| Children’s toys and appliances | 1% |

| Service & Care | 1% |

| Other | 0% |

These products were made by companies headquartered in 28 countries across the globe. However, as shown in Figure 2, about four fifth of the products come from manufacturers in just five countries: the USA (28%), China (25%), the UK (14%), Germany (7%) and Japan (4%).

Figure 4: Consumer connectable products sold in the UK, by country of origin (n=1024 products)

| USA | 28% |

| China | 25% |

| Other | 23% |

| UK | 14% |

| Germany | 7% |

| Japan | 4% |

The importance of these countries as manufacturers of UK consumer connectable products depends on the type of product. The below figure breaks down the country of origin by product category. It focuses on the six main product categories: safety and security, lighting, smart home, kitchen appliances, audio, health, fitness & wellbeing, and wearables which account for almost 70% of the products mapped. The USA manufactures 43% of health, fitness and wellbeing products, 36% of kitchen appliances, and 30% of safety and security products. China, in turn, manufactures 41% of lighting products, 24% of smart home products, and 23% of safety and security products. The UK manufactures 24% of audio products, 23% of health, fitness and wellbeing products and 17% of safety and security products. The final two players only manufacture a significant share of one type of products: Germany manufactures 15% of kitchen appliances; Japan manufactures 14% of audio devices mapped in our dataset.

Figure 5: Consumer connectable products sold in the UK, by category and country of origin (n=1024 products)

| Audio | Health, Fitness & Wellbeing | Kitchen appliances | Lighting | Safety & Security | Smart Home | Wearables | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USA | 20% | 43% | 36% | 25% | 30% | 22% | 24% |

| Other | 20% | 15% | 37% | 19% | 22% | 27% | 17% |

| China | 20% | 6% | 3% | 41% | 23% | 24% | 31% |

| UK | 24% | 23% | 8% | 5% | 17% | 15% | 24% |

| Germany | 1% | 6% | 15% | 9% | 6% | 10% | 0% |

| Japan | 14% | 6% | 1% | 1% | 2% | 1% | 5% |

The products we mapped were produced by 394 different companies under 416 different brand names. The next subsection illustrates where the manufacturers are headquartered; how large they are in terms of employees and turnover data, and where they sell their products.

Manufacturers of consumer connectable products sold in the UK

The map in figure 4 illustrates the countries of origin of the products we mapped. The darker shades of blue show a higher number of manufacturers from the respective country; the lower shades illustrate a lower number of manufacturers. The main players are the US (n=134 manufacturers), China (83), and the UK (67). Smaller players include Japan (18), Germany (16), France (11), the Netherlands (8), Canada (9), (Taiwan (7), Switzerland (5) and South Korea (4).

Figure 6: Manufacturers of consumer connectable products by country of origin (n=394 manufacturers)

Size of manufacturers of consumer connectable products

As shown in Figures 5 and 6, the market is dominated by large players: 37% of the companies in our dataset were large businesses with more than 250 employees; 21% were medium-sized businesses with 50-249 employees; 20% were small businesses with 10-49 employees, and 8% were micro businesses with fewer than ten employees. It was not possible to find information on the number of employees for the remaining 14% of companies.

The turnover data reflects this trend. 29% of the companies in our dataset had a turnover of over GBP 50 million; 15% had a turnover between 10 and 50 million; and 22% had a turnover of up to GBP 10 million. It was not possible to find information on turnover for the remaining 34% of companies. It is worth noting that the missing data was not random. In particular, a relatively larger share of the missing data came from China: 35% of the companies we did not find turnover data from were headquartered in China – 10% more than in the whole sample.

Figure 7: Manufacturers of consumer connectable products, by size (n=394)

| Micro: 1-9 employees | 8% |

| Small 10-49 employees | 20% |

| Medium: 50-249 employees | 21% |

| Large: 250+ employees | 37% |

| Data unavailable | 14% |

Figure 8: Manufacturers of consumer connectable products, by turnover (n=394)

| Up to £10m | 22% |

| £10m - £50m | 15% |

| More than £50m | 29% |

| Data unavailable | 34% |

Routes to market

Figure 7 shows where these manufacturers sell their products. Because some manufacturers manufacture products for more than one brand, and because they sometimes use different routes for their different brands the graph shows the statistics for the population of brands (n=416), not manufacturers. Note, too, that manufacturers usually use more than one route to the market. The overwhelming majority of brands are sold online: 88% of brands were sold on at least one online third-party marketplace like Amazon or ebay; 72% were also sold on companies’ own websites. The importance of online third-party marketplaces was confirmed in the CATI survey: 68% of manufacturers consulted as part of the telephone interviews (21/31) sold their products on an online third-party marketplace; 74% of manufacturers (23/31) sold them on their own website. For the time being, however, the online market has not crowded out the physical retail market. Almost half of the brands in our dataset (45%) and 74% of the manufacturers we telephoned (23/31) sold their consumer connectable products in physical shops such as Currys or Argos.

The least common route to market was company’s own physical shops. Just 9% of the brands in our desk research dataset and a fifth of the companies consulted through the CATI survey (5/31) maintain their own physical shops. Typically, these were large, global brands such as Apple, Bang & Olufson, Dyson, Nespresso, Samsung, and Siemens. As the CATI survey consulted a higher share of larger manufacturers it showed a relatively larger share of manufacturers who had their own in-person shops. While data was not collected on sales in the online and the offline market, the fact that many small and medium-sized manufacturers opted not to enter the retail market indicates that the offline market is less profitable than the online market. In-person shops may, however, serve other purposes, such as brand recognition, customer experience and trust.

Figure 9: Brands of consumer connectable products by routes to market (n=416 brands)

| Routes to market | Yes | No | Data unavailable |

|---|---|---|---|

| Own physical shops | 9% | 89% | 2% |

| Physical shops | 45% | 53% | 2% |

| Own online shops | 72% | 26% | 2% |

| Third party online Marketplaces | 88% | 9% | 2% |

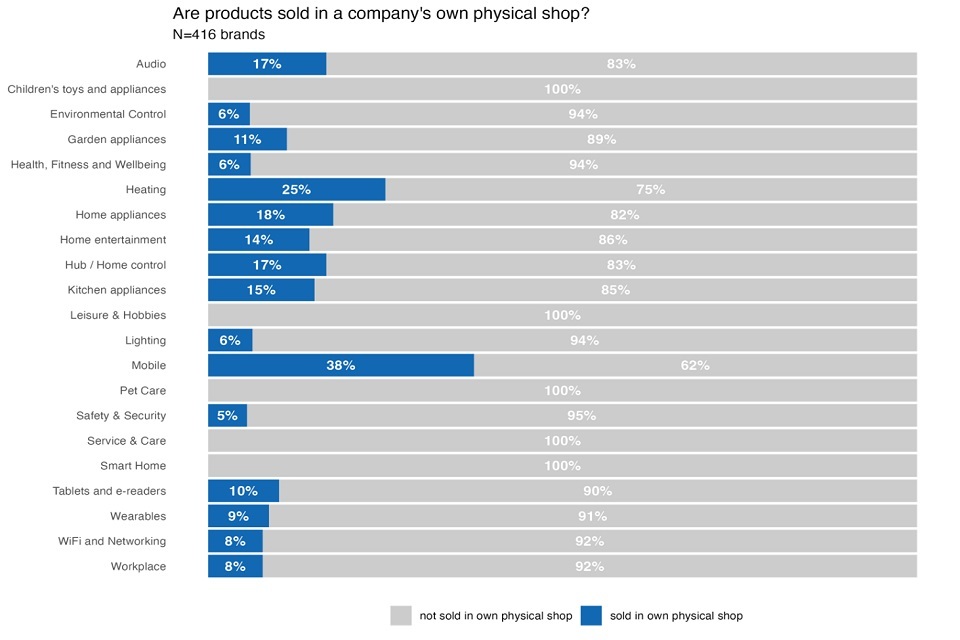

The routes to market chosen by manufacturers also vary based on the types of products sold. In the technical report, we show the routes to market for each product type. In particular, physical shops were far more common for some products than others: All of the service and care products and all tablets and e-readers mapped in our dataset, as well as 84% of kitchen appliances, 83% of audio devices were sold in physical shops such as Currys, or Argos. Similarly, some types of products were more likely to be sold in a company’s own physical shop. This was particularly true for technical devices: 38% of mobile devices, 25% of heating devices, and 18% of home appliances were sold in companies’ own physical shops.

Challenges in securing the data

Carrying out the desk research on these products, we faced a number of challenges. First, it was often difficult to determine whether a given consumer connectable product was in scope. The research was restricted to manufacturers who will need to comply with the cyber security requirements stipulated in the PSTI Regulations 2023. The word ‘smart’ or ‘connectable’ was not always a reliable indicator of whether a product was in scope. For instance, not every ‘smart treadmill’ can be connected to the internet, or to a phone. In addition, many websites of IoT devices do not disclose shipping information until the last step of a purchase and sometimes require registration, making it difficult to determine whether the products would be available in the UK. Moreover, a number of manufacturers in the original datasets were found to be industrial IoT manufacturers, component/part manufacturers, or even consultancies with expertise in IoT product development. These were excluded from the dataset.

At the product level, there is also limited data available on the number of products sold by each manufacturer in the UK and no reliable estimates across the market as a whole. This is further exacerbated by the role of online third-party marketplaces, which provide access to the market for a significant array of ‘smart’ products.

Second, it was often difficult to find the manufacturer. While most websites disclosed information on the company behind their products, some did not. In some cases, additional research led to Chinese manufacturers, but that information was often difficult to verify. Names of Chinese manufacturers, in particular, were often similar, raising questions on whether they were the same entities. Even in cases where it was not possible to find the name of a company, the legal role of that company was not always provided, making it difficult to understand whether it was a manufacturer, or merely a seller or a distributor. Initially, we attempted to find factory locations. Because this data was almost never disclosed, we removed this variable. Furthermore, the complexity of corporate structures often made it difficult to determine which branch, or division of a manufacturer was responsible for complying with the PSTI Regulations.

Third, finding turnover and employee data was not always possible. Here, the reliability of the data depends on the origin and size of the manufacturers. For UK-based companies, Companies House information allowed us to find reliable numbers. Similarly, large international companies tend to publish reliable turnover data in their annual reports. Both sources provided us with reliable data. In many cases, however, reliable estimates were not available. For smaller international companies, we often relied on websites collecting finance data on different companies. In some cases, various websites provided conflicting information about a company’s turnover. In other cases, we found no information at all.

3.2 Market Dynamics

The market for IoT devices is on the rise. According to data from Statista, the UK IoT market is expected to reach GBP 24.74 billion by the end of 2024. At an estimated annual growth rate of 11.8%, the UK IoT market is expected to reach GBP 38.65 billion by 2028.[footnote 7] These developments reflect a global trend: worldwide, the IoT market is expected to reach GBP 1,100.72 billion by the end of the year. At an estimated annual growth rate of 12.57%, the global IoT market is expected to reach a staggering GBP 1,767.35 billion by 2028.[footnote 8]

While the overall UK IoT market is growing, players are entering and exiting at a fast pace. Many of the companies compiled by Copper Horse in the autumn of 2023 are either no longer manufacturing consumer connectable products in early 2024 or they are not available in the UK, showing a market in flux. Manufacturers in our telephone interviews noted that the consumer connectable market was a diffult market. In some areas, sales are declining, and there are indications of oversaturated markets and/or dominant manufacturers for some categories of consumer connectable products (e.g. smart cameras and smart watches). This is also reflected by statements from companies who have left the consumer connectable products market. For instance, in its Fiscal Year 2023 Results, Fossil cited low and declining sales as a reason to exit the smart watch market in 2024.[footnote 9] Low sales have reportedly also reduced the market for large appliances (which includes ‘smart’ freezers, ovens, dishwashers etc.) According to data from the Association of Manufacturers of Domestic Appliances (AMDEA), the large appliances marked dropped 11% in 2023, and is expected to continue to fall in 2024.[footnote 10]

Another challenge continues to be the UK’s departure from the single European market. Through the CATI survey, representatives from five large consumer connectable product manufacturers reported that Brexit had challenged their business operations. Some of these challenges relate to marketing. For instance, one company reported that it had to separate their UK marketing from their EU marketing in response to Brexit.

However, another more substantive challenge relates to regulatory alignment. Manufacturers reported that complying with UK regulation, as well as EU regulation takes time and adds considerable costs without offering significant benefit from a consumer perspective. Ultimately, the cost associated with doing business in the UK after Brexit led at least one company in our sample to streamline some of their product portfolio.

Looking ahead, companies see risks related to the prospect of increasingly diverging regulations, including any divergence brought by the EU Cyber Resilience Act (which is still under negotiation). These issues are not confined to IoT companies – according to December 2023 research by the BBC’s Insights Unit, almost two thirds of UK firms (n=733) said that trading with the EU had become more difficult than it was a year ago.[footnote 11]

In addition to the high levels of turnover in the IoT market and continued issues around Brexit, the market is also seeing developments in the origin of smart products. In particular, a large, and growing share of IoT products sold in the UK come from China. This is true for the majority of low-cost consumer connectable products sold on Amazon. In addition, relatively large shares of consumer connectable products in the areas of service and care, tablets and mobile devices, home appliances, smart home devices, and leisure and hobby products are manufactured in China. In addition to brands that are transparently manufactured in China, our research found many brands that do not publicise the Chinese origins or Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEM) of their products. For instance, the manufacturer Havit (Guangzhou Havit Technology Co., LTD), which itself markets two smart product brands, also provides an OEM / ODM (Original Design Manufacturer) service to more than 35 companies globally, including many that are present on the UK market such as Polaroid, Lidl, Aldi, Hema and Costco.[footnote 12] This also illustrates the complexity of modern, global supply and value chains.

In some product categories, the top hits on Amazon.co.uk led to brands that were not clearly linked to any manufacturer. For many of these, careful searches revealed Chinese manufacturers, parent companies, sellers, or distributors. This lack of transparency was particularly notable in the area of security cameras, where English-sounding names were used to disguise products of Chinese origin. In addition, recent years have seen a number of Chinese acquisitions of IoT manufacturers, including long-standing European companies, such as the 2022 acquisition of Suunto by Lieshing[footnote 13], or acquisitions of larger shares of IoT companies.

The increasing importance of Chinese products also reflects a broader trend. Fuelled by investments and advancements in 5G technologies, artificial intelligence, and smart cities, China’s position in the global IoT market is strong, and poised to grow. Between 2024 and 2028, the Chinese IoT market is projected to grow at a rate of 13.5%.[footnote 14] According to estimates, it will surpass the United States by 2027, and will reach a market volume of USD 290.80 billion by 2028.[footnote 15]

The growing number of cyber attacks and the sensitive nature of the information that can be accessed through consumer connectable products (including, for instance, audio data, video footage, data on movement, or credit card information) should make cyber security and the regulation of smart devices a top priority for businesses and governments.[footnote 16]

4. Analysis of PSTI awareness, compliance and impacts

Triangulating the data from the CATI survey, the desk research and the qualitative interviews, this section presents an analysis manufacturer awareness of and compliance with the PSTI Act 2022 and the PSTI Regulations 2023, as well as other related standards. It also summarises evidence on the anticipated economic, social and/or environmental impacts of the PSTI regime.

4.1 Awareness of the PSTI regime

The awareness of manufacturers of the PSTI Act 2022, the PSTI Regulations 2023 and their provisions was primarily examined through the CATI survey conducted with manufacturers of consumer connectable products. This was supplemented by in-depth qualitative interviews with manufacturers and representatives of industry.

While the total number of manufacturers that participated in the CATI survey does not allow for robust extrapolation to the entire population of consumer connectable product manufacturers, this sample is clearly conscious of the introduction of cyber security regulations in the UK market: 91% (30 of 33 respondents) reported being aware of relevant regulations, while 56% specifically mentioned the ‘PSTI’ and 17% noted the April 2024 entry into force unprompted.

When prompted with a list of specific regulations, including the PSTI Act 2022, the PSTI Regulations 2023, ETSI EN 303 645 and ISO/IEC 29147: 2018 on vulnerability disclosure, the awareness levels of manufacturers reduced slightly, but remained strong. As illustrated in the below figure, all the regulations and standards were known by at least 70% of respondents. Awareness was highest regarding the ETSI standard (88%), while 79% were aware of the PSTI Regulations and 73% were aware of the PSTI Act. Only two manufacturers were not aware of any of these core regulations and standards.

Figure 10: Awareness of specific regulations and standards (Question 3, Base: 33)

| PSTI Act (n=24) | 73% |

| PSTI Regulations 2023 (n=26) | 79% |

| ETSI EN 303 645 (n=29) | 88% |

| ISO/IEC 29147:2018 (n=23) | 70% |

| I am not aware of any of these regulations or standards (n=2) | 6% |

Looking in more detail at the specific provisions of the PSTI Act and Regulations, including the three security requirements, most manufacturers (76%, 25 of 33) said that they were fully aware of the specific provisions, with a further four partially aware. The remaining four manufacturers were ‘not aware at all’.

Considering differences across manufacturers, industry interviewees noted the possible impact of manufacturer size on awareness levels, stating that smaller companies often have fewer resources available to proactively track regulatory developments, engage with Government (e.g. directly or through consultations) or participate in industry groups. However, due to the small sample size, the data does not provide any indications whether and to what extent business demography factors, such as manufacturer size or location, have an impact on awareness levels. There were also no indications that the lack of industry engagement in the CATI survey stems from a lack of awareness of the PSTI Act and Regulations.

Beyond the core regulations and standards noted above, respondents across both the CATI survey and the qualitative interviews highlighted awareness of other existing or proposed cyber security-related legislation. The following UK and EU legislative developments were raised:

-

Proposal for a Regulation on horizontal cybersecurity requirements for products with digital elements (also known as the Cyber Resilience Act, CRA). Published in September 2022, the proposed legislation, which will be applicable across all EU Member States, aims to create conditions for the development of more secure products and greater consumer awareness. As of March 2024, the CRA remains under negotiation.

-

Delegated Act to the Radio Equipment Directive. Published in October 2021, the delegated act established new legal requirements for the implementation of cybersecurity safeguards in connected products. The delegated act was originally scheduled for enforcement in August 2024; however, as highlighted by interviewees who will be required to adhere to both the delegated act and the PSTI legal regime, the entry into force has been delayed until August 2025 due primarily to the time required to prepare harmonised standards supporting the legislative amendment.[footnote 17]

-

Certain types of manufacturers, such as those that are also telecommunications service providers, also highlighted other legislation that introduces cyber security requirements (albeit not for consumer products). These include the UK Telecommunications (Security) Act 2021 and EU Directive 2022/2555 on measures for a high common level of cybersecurity (NIS 2 Directive).

The impact of these interrelated laws on manufacturer compliance are examined further in section 4.2.

In addition to ascertaining awareness levels amongst manufacturers, the research investigated the mechanisms by which businesses became aware of the PSTI regulatory regime. For manufacturers at least partially aware of the new regulations, the most likely source of this awareness was industry or trade bodies (48%). After some margin, the second most common source of awareness was public Government consultations (28%), followed by internal legal, compliance or product security teams (21%). These data are illustrated in the below Figure.

A large proportion also mentioned ‘other’ sources (45%). These alternative sources included: partner organisations, such as distributors, importers and laboratories; LinkedIn and in-person networking events; EU Parliament discussions; customers (i.e. retailers) and consumer organisations (e.g. Which).

In terms of under-utilised mechanisms, respondents report low levels of proactive tracking of cyber security or trade legislation (e.g. through internet alerts) (7%), as well as engaging with past government research (3%) or communicating directly with Government (14%).

Figure 11: Sources of awareness of new regulations (Question 12, Base: 29, multiple responses possible)

| Industry trade/membership body (n=14) | 48% |

| Public Consultations, Gov.uk website or cal for views (n=8) | 28% |

| Internal legal, compliance or product security teams (n=6) | 21% |

| From others in the industry (n=5) | 17% |

| Media, press releases or communications (n=5) | 17% |

| Direct engagement with Government (n=4) | 14% |

| Engagement with standards bodies (n=4) | 14% |

| Proactive tracking of cyber security or trade legislation (n=2) | 7% |

| Previous research surveys conducted by government/third parties (n=1) | 3% |

| Other (n=13) | 45% |

Similarly, the most common mechanisms through which manufacturers will ensure awareness with any future regulations include 49% via industry or trade bodies (16/33), and 42% via UK Government public engagements (14/33).

4.2 Compliance with the PSTI regime

The CATI survey with manufacturers, complemented by desk research and in-depth qualitative interviews, examined compliance with the PSTI regime and its impacts.

Compliance context and challenges

Regarding compliance with the PSTI regime, a key finding from the research with manufacturers and industry representatives was that the security requirements themselves are generally technically straightforward to implement, with some exceptions related to the requirement on transparency on the minimum length of time for security updates. However, challenges related to the overarching regime have resulted in compliance processes that are more complex, uncertain and costly than anticipated.

The representatives of industry associations interviewed for this research strongly agree with the need to introduce baseline security requirements for consumer connectable products.[footnote 18] They also strongly appreciate the use of a phased approach to placing cyber security-related legal obligations on manufacturers – i.e. the initial introduction of three key cyber security requirements, in the context of the wider set of guidelines documented in the UK CoP and the ETSI standard.

However, manufacturers report experiencing the following challenges when implementing the legislation:

Product scope: Many stakeholders, across the CATI survey and the in-depth interviews, reported uncertainties regarding what products should be within scope. Key ‘grey areas’ highlighted by stakeholders include how to deal with: (i) products that connect to internet-connected devices via Bluetooth (e.g. the case of earbuds with or without multipoint connection[footnote 19]; and (ii) connectable products that are only sold B2B but are ultimately used by consumers in a given setting (e.g. manufacturers in the print device space[footnote 20]. In these instances, manufacturers report having to invest time liaising with industry associations, technical cyber security experts and others to determine whether their products are in scope, often without a clear conclusion.

In addition, while the Government’s 2021 response to the call for views presents an explanation of the rationale, some manufacturers report being unclear why desktop, laptop and tablet computers (that do not have the capability to connect to cellular networks) are excepted under Schedule 3 of the PSTI Regulations 2023.[footnote 21]

‘Information on minimum security update periods’: Considering the third security requirement, detailed in paragraph 3 of Schedule 1, manufacturers reported challenges indicating a minimum support period for each product, meaning the “minimum length of time, expressed as a period of time with an end date, for which security updates will be provided”. In particular, the complexity of modern supply chains contributes to this challenge; for instance, one manufacturer highlighted that it may be difficult to ensure support from suppliers (e.g. component manufacturers) for a named period of time.

Others noted the implications of differences in terminology between the PSTI Regulations 2023 and European legislation. While the PSTI regime requires both the period of time and an end date, the proposal for a Cyber Resilience Act only requires the end date (i.e. products shall be accompanied by information on “the type of technical security support offered by the manufacturer and until when it will be provided, at the very least until when users can expect to receive security updates”). The manufacturers interviewed for this research noted that the PSTI requirement is more difficult to establish as, from the consumer perspective, the period of time for which a product is supported will differ depending on the date of purchase.

Timelines for implementation: While the extensive policy work that led up to the adoption of the legislation (e.g. on the CoP and the ETSI standard) was acknowledged by manufacturers and industry associations, these stakeholders countered that, in practice, industry does not initiate compliance activities until the final legal text has been enacted. As such, while the PSTI Act was adopted in December 2022 and a full draft of the PSTI Regulations was published in April 2023 (thereby providing an initial implementation timeline of 12 months), the Regulations were signed into law on 14 September 2023.

Primarily due to the challenges of ensuring the compliance of stock that is already on the market (e.g. in the possession of retailers) but may not be sold by 29th April 2024, many respondents perceive that the timeline for implementation is insufficient.

Specifically, industry associations note the difference in terminology between the PSTI regime, which applies to products that are ‘made available’ in the UK, and other product safety legislation, which more commonly applies to products that are ‘placed on the market’. The reason for this, as detailed in the Government’s 2021 response to the call for views, was that consumer connectable products remain connected and compliance can change after entering the supply chain. However, when combined with the implementation timeline, industry understands that all consumer connectable products that are “currently in production or available for sale in stores and warehouses will need to demonstrate compliance in accordance with the new regime”[^22] by 29th April 2024.

Citing vast global supply chains within the production ecosystem, as well as long shipping timelines, some industry representatives say that this could lead to existing stock being scrapped or recycled. This perspective was supported by individual manufacturers that engaged in this research, who questioned how these requirements and statements of compliance can be retrospectively applied to products that are already in the supply chain and market.

Demonstrating compliance: Linked to the above point on timelines, manufacturers reported that they are “still consulting with [their] distributors and cyber security expert[s]”, as the requirements for the format and contents of the Statement of Compliance (SoC), while detailed in Schedule 4 of the PSTI Regulations 2023, are perceived to be unclear. For instance, while some manufacturers deem it sufficient to state that they are compliant, others are considering if they need to provide details or evidence of exactly how they comply.

“There are a number of industry stakeholder groups including retailers. One thing they are looking at is how the statement of compliance should look. As an industry, we feel it would be better if there were a standard format for the statement of compliance. But there is doubt as to who the statement of compliance is aimed at. If there is a standard way everybody knows what they are looking at. Unfortunately, legislation is very unclear on the format”.

Compliance levels

In this context, many respondents highlighted that ensuring compliance was still an ongoing process, although this varies depending on the requirement. As illustrated in the following figure, the second requirement, related to providing ‘Information on how to report security issues’, has been introduced for all products by the highest number of manufacturers consulted (58%, 19/33), closely followed by the provisions on passwords (52%, 17/33). Regarding ‘Information on minimum security update periods’, the number of manufacturers that have already introduced this requirement for all products drops to only 27% (9/33), with a higher proportion reporting that they intend to introduce the requirement within a certain time frame (39%, 13/33).

Figure 12: Compliance status for each of the three requirements (Question 6, Base: 33)

| Compliance status | Passwords | Public point of contact | Security updates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Introduced for all products | 52% | 58% | 27% |

| Introduced for some products | 12% | 0% | 6% |

| Looking to introduce within a certain time | 9% | 24% | 39% |

| Looking to introduce in the near future but not sure when | 12% | 18% | 21% |

| Not looking to introduce for some products | 3% | 3% | 3% |

| Not looking to introduce at all | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| This requirement is not relevant to us | 18% | 3% | 21% |

Positively, none of the manufacturers consulted stated that they are ‘Not looking to introduce the requirement at all’, while only one respondent for each requirement noted that they will not introduce the requirement for some products and around 20% of manufacturers responded that the requirements related to passwords and security updates were not relevant to their products. The reasons provided included:

- Passwords: As illustrated by the following manufacturer quotes, the primary reason was that the products do not use or store passwords and/or use other methods for authentication.

“We don’t set any passwords or store any passwords”.

“Never used passwords, we have another method. Already compliant connecting to back end services”.

- Information on minimum security update periods: Reasons raised by manufacturers indicated a lack of understanding of the requirement, tying into the abovementioned challenges. For instance, the reasons included not wanting to be ‘locked down’ to a minimum period and the intention to service products indefinitely. However, the law does not prevent manufacturers from providing support beyond the minimum support period.

“We are very transparent, never locked down to a minimum period, just pragmatic based on number of users using products. Products last a long time. Also, we provide care for over 7 years”.

“Our claim is to service products indefinitely. This also includes software updates. No exact end date. Over full life time”

Besides implementing the three security requirements, a key part of compliance is demonstrating compliance, including the requirement that all products will need to be accompanied by a Statement of Compliance (SoC). In this regard, manufacturers were asked how they intend to demonstrate compliance for each requirement.

Notwithstanding the abovementioned challenges related to the SoC, the most common response was to state that the manufacturer deems the product to be

compliant within the SoC. In addition, for the requirement on passwords, manufacturers highlighted work with internal/third-party testing or third-party compliance assessment companies and made direct reference to the provisions of ETSI EN 303 645. Responses on the information-related requirements focused on supplementing the SoC with publicly available information on points of contact, vulnerability disclosure processes and security updates. Across the manufacturers consulted, this information will be made available through websites, apps and product instruction manuals.

Specifically considering the SoC, manufacturers were asked whether they have been contacted by distributors or retailers asking for information on compliance or a SoC. Around 70% of manufacturers (23/33) have been contacted by distributors, including retailers, indicating that these stakeholders are generally aware of the legislation and the implications for products they sell or distribute. To illustrate, a selection of manufacturer responses is presented below:

Manufacturer responses on SoC development and deployment:

“We’ve had direct engagement with distributors and retailers planning what we are going to do. They will be able to access it and put it with their own needs”.

“All new products coming into the country will have [an SoC] already in a box. We are contacting the retailers to label packaging allowed by the regulation so we can retro-actively provide SoC to any stock they have got”.

“Normally when we do new products, with safety, we issue a Declaration of Conformity. Similar process”.

“We are working with cross industry groups to establish a working template of SoC, tick boxes, to integrate into our systems. We have already been doing this since the back end of last year trying to whittle down stock in the warehouse to reduce resource required for this work. We have the SoC built into this, so we can include it in our document bags. Just profiling what stock is in retailer or warehouses, and then we will create a plan for the resource to go in and rework the stock including the SoC as required”.

The results of the CATI survey were also validated through in-depth desk research to assess evidence of manufacturer compliance based on publicly available information. As illustrated in the below figures, this exercise generated mixed results regarding evidence of compliance[footnote 23] for each requirement across a sample of 70 manufacturers representing a balance of business sizes and locations of headquarters:

- Passwords: For the requirement on passwords, manufacturers are relatively evenly spread across the categories, with 15 of 70 companies (21%) considered to show strong signs of compliance, 17 (24%) were somewhat compliant, and 19 (27%) not compliant. Limited information was available on the approach of the remaining 19 (27%) companies to passwords.

Figure 13: Evidence of compliance with the PSTI security requirement on passwords (n=70)

| Passwords | Total |

|---|---|

| Compliant | 21% |

| Somewhat compliant | 24% |

| Not compliant | 27% |

| Information not available online | 27% |