An assessment of Independent Child Trafficking Guardians (accessible version)

Updated 6 January 2022

Research Report 120

Authors: Hannah Shrimpton, Roya Kamvar, Jonathan Harper, Samuel Gordon-Ramsay, James Long and Stuart Prince

October 2020

Executive summary

Introduction

Section 48 of the Modern Slavery Act 2015 introduced the role of Independent Child Trafficking Advocates (ICTAs) to provide an independent source of advice and advocacy for trafficked children. ICTAs were introduced to three initial adopter sites in January 2017: Greater Manchester, Hampshire and the Isle of Wight, and nationally in Wales. Following the Independent Review of the Modern Slavery Act 2015, ICTAs were renamed Independent Child Trafficking Guardians (ICTGs) in July 2019.

Following interim findings from the evaluation of the ICTG service in July 2018, the Government announced a revision of the ICTG model. As part of the revised model, provision of the Service underwent a change of structure to reflect the differing needs of children who have existing support networks in the UK compared with children who do not. Children without a figure of parental responsibility for them in the UK continue to receive one-to-one support from ICTG Direct Workers,[footnote 1] while the ICTG Regional Practice Co- ordinators’ (RPCs’) role was introduced to focus on children who do have a figure of parental responsibility. The role of the RPCs is to encourage multi-agency support for children who have been identified as trafficked or potentially trafficked, by advocating for the child and ensuring that their ‘best interests’ are being considered in the decisions made by public authorities. The Government also expanded the Service to three later adopter sites: East Midlands, the London Borough of Croydon, and West Midlands Combined Authority.[footnote 2]

Research objectives and methodology

The Home Office and Ipsos MORI jointly conducted the assessment of the RPCs’ role. Ipsos MORI was commissioned by the Home Office to conduct a qualitative assessment of the delivery and impact of the RPCs’ role. Its aim is:

- to gain an in-depth understanding of how the RPCs’ role has been working since its first introduction in October 2018; and

- the perceived impacts on both the professionals within relevant sectors and the children they support.

The Home Office was responsible for the quantitative element of the evaluation using data collected by Barnardo’s (the ICTG service provider).

The assessment involved the collection and analysis of quantitative and qualitative data. The qualitative research involved interviewing 36 stakeholders, including professionals working for the ICTG service, as well as operational and strategic staff working in social care, the criminal justice system and the Single Competent Authority (SCA), the UK’s decision-making body of National Referral Mechanism (NRM)[footnote 3] considerations. The quantitative data complements the qualitative research by providing contextual information throughout the report. It is composed of three data sets:

- NRM data to compare NRM decisions in ICTG sites with the rest of the UK, as well as to estimate the number of children who fall under the RPCs’ coverage;

- data collected by Barnardo’s on the demographics and case length of children in the ICTG service; and

- data collected by Barnardo’s on the amount of contact between RPCs and other professionals, as well as between ICTG Direct Workers and the children on their caseload.

Background and context

A total of 513 children were supported by the ICTG service between October 2018 (when the first RPC was established) and December 2019; one third of these children were supported by RPCs. This takes the total number of children supported by the Service since its inception in February 2017 to 901.[footnote 4]

Around three quarters of children supported by RPCs were referred primarily for child criminal exploitation (CCE),[footnote 5] with almost all the remaining children referred primarily for child sexual exploitation (CSE).[footnote 6] Stakeholders suggested that CCE affects all geographic areas, but especially urban areas with more gang activity.

Most children referred to RPC caseloads were UK nationals (90%), male (70%), and aged between 15 and 17 (76%), a pattern that was consistent across each site.

There was a strong association between males and CCE, and females and CSE. Almost all (98%) of the males supported by RPCs were referred for CCE, while most of the females (80%) were referred for CSE. However, no clear associations could be found between exploitation type and other demographic characteristics.

Stakeholders believed that circumstances that hinder stability in a young person’s life, such as access to education and instability at home, could increase their vulnerability to exploitation. Stakeholders also noted the difficulty in supporting children who were exploited by their own families.

Delivery of the RPCs’ role

The RPCs’ role was not designed prescriptively, which has meant that while the role shared some core functions across regions, there was flexibility within the role. This allowed RPCs to adapt methods of delivery depending on the needs and organisational structure of the area.

The ICTG service reported that RPCs generally worked infrequently with Direct Workers but would regularly partner with ICTG Service Managers.[footnote 7] This ensured ICTG service coverage at multi-agency meetings and helped to identify gaps in services to victims of child exploitation across regions. RPCs created links between the ICTG service and across partner agencies by:

- attending both strategic and operational multi-agency panels;

- brokering conversations between agencies for individual children; and

- sometimes embedding within teams.

RPCs would raise awareness, train and upskill services within local authorities. Stakeholders mentioned the different ways they did this, including delivering formal awareness-raising sessions on:

- indicators of child exploitation;

- the NRM process; and

- how to support children who had been trafficked or exploited.

These awareness-raising sessions were supplementary to the training that public authorities and first responder organisations ordinarily provide.

RPCs provided hands-on support to operational professionals for the children who they were working with. Stakeholders gave many examples of this including:

- co-ordinating a multi-agency response;

- confirming the presence of child trafficking indicators;

- advising on appropriate support packages to meet the needs of the child;

- supporting front-line staff throughout criminal proceedings; and

- reviewing or collecting information for NRM referrals.

The quantitative data reflects the observations made by stakeholders on the organisations that RPCs support. Front-line workers such as social workers (34%), Youth Offending Team members (14%) and the police (10%) accounted for the majority of contact that RPCs had with other professionals on behalf of the children they support.[footnote 8] The NRM (37%), safeguarding (23%) and social care (16%) were the three most common topics that RPCs discussed with others on behalf of the children they supported.

The skills and expertise of the RPCs, as well as any prior connections formed in previous roles, were important contributing factors to the RPCs’ role working well. In particular, the ability to build relationships with different agencies and local authorities was seen as a key enabler to the RPC being successful in their role. The independence of RPCs also reportedly helped to build trust with agencies as RPCs were generally viewed as impartial. RPCs reported that the flexible nature of their role enabled them to tailor their offer to the needs of different local authorities.

The main challenges experienced by RPCs were generally based on external factors. Stakeholders reported that some teams within local authorities could be reluctant to engage with RPCs, for example, if there were concerns that the RPCs’ role was to scrutinise or inspect teams. RPCs could also struggle to work with some police forces where there was a lack of understanding about the nature of CCE and the benefits of the NRM. Tight resourcing and high turnover within local authorities was also said to limit the ability of professionals to take-up RPC awareness-raising sessions and embed best practice.

Outcomes of the RPCs’ role

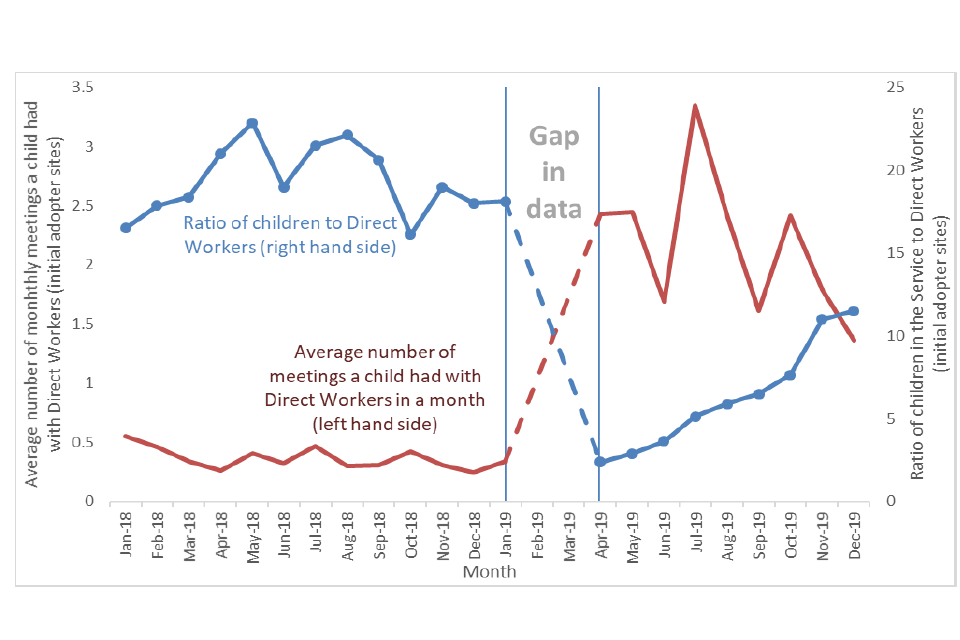

Direct Workers reported that the introduction of RPCs had increased their capacity, enabling them to spend more time with the children they worked with. This is reflected in the quantitative data. In the initial adopter sites the ratio of Direct Workers to the children they supported decreased following the introduction of the RPCs’ role, while the number of meetings that Direct Workers had with children increased.

ICTG teams also felt that the RPCs’ role had bolstered the reach of the ICTG service, strengthening the knowledge base of the Service and creating targeted partnerships with key agencies.

There was evidence that RPCs may have had a positive impact on professionals’ awareness of indicators of child exploitation (particularly of CCE) and how best to support children; particularly on social care, youth offending and police teams. Feedback from stakeholders indicated that improvements in services’ awareness, confidence and capacity to submit and navigate the NRM process were particularly noticeable. However, some teams reported that RPCs had less impact on their awareness of child exploitation, as they already had high levels of expertise in this area before the RPCs came to their region.

There was a general acknowledgement that awareness-raising about Section 45 of the Modern Slavery Act was in an early stage. Section 45 provides a statutory defence for victims of modern slavery for certain criminal offences that they were compelled to carry out as a result of their exploitation. Reasons for slow progress were generally seen as external to RPC efforts. These included:

- a lower baseline level of awareness amongst professionals outside the ICTG service;

- the complexity of the legislation; and

- the sensitivities involved in trying to navigate the use of the defence at court and with the police.

The RPCs’ role was felt to have had a clear positive impact on outcomes for children in several ways, with operational stakeholders drawing on specific examples from their caseloads. RPCs were seen as a safety net for children in the region, with many stakeholders feeling that RPCs had identified gaps in service provision for child victims of modern slavery on a strategic level, as well as on a case-by-case basis. Stakeholders felt more children were identified as needing support than previously, because professionals were either:

- more aware of the needs of exploited children due to RPCs raising awareness; or

- more aware following RPC advice regarding the individual children that professionals were working with.

The multi-agency links created by RPCs as well as their advocacy for the use of relevant legislation or disruption orders were seen as important in developing holistic support packages for children.

However, there were some concerns that certain children’s needs could not be met by the ICTG service if RPCs are not able to work directly with children. It was felt that in circumstances where public services were unable to provide an appropriate key worker or where the exploitation was particularly hidden, children could benefit from RPCs having the opportunity to work directly with them.

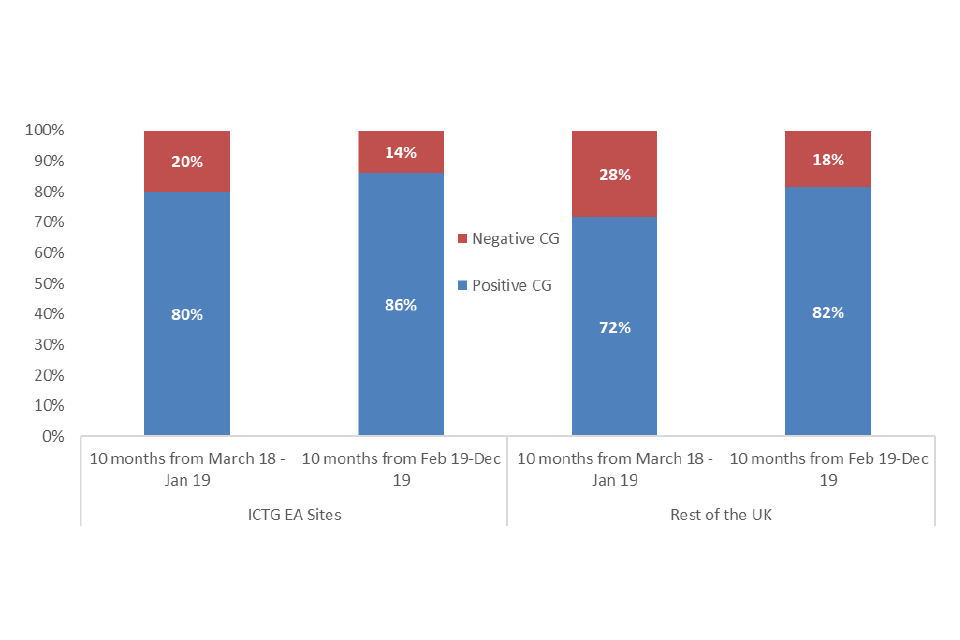

The introduction of RPCs was felt by some stakeholders to have resulted in increased numbers of NRM referrals and a higher proportion of positive NRM decisions.[footnote 9] The latter is a view the quantitative data seems to support.[footnote 10] However, there was an acknowledgement that these positive shifts were due to a multitude of factors, including a national increase in awareness of CCE and CSE. It was noted that it could be difficult to disentangle the contributions of the RPCs’ role from the contributions of different agencies, organisations and charities, as well as the ICTG service as a whole.

Conclusions and lessons learnt

Overall the assessment found that stakeholders were very positive about the RPCs’ role, particularly in raising awareness about indicators of exploitation and increasing the confidence of stakeholders to submit good quality NRM referrals. Positive outcomes for children as perceived by stakeholders were also seen. The assessment highlighted the following important considerations for rolling out the RPCs’ role nationally.

- The skills and expertise of RPCs were pivotal to the success of the role. Stakeholders felt that their ability to build relationships with different agencies and local authorities was particularly important. Relationship-building skills should be considered as part of the recruitment of RPCs.

- The RPCs’ role added strategic planning capacity to the ICTG service. However, the assessment highlighted that RPCs sometimes struggled to find the right balance between the strategic and operational components of their role, meaning that supporting operational staff was often prioritised. This suggests resourcing of each area should be considered, particularly once the ICTG service is embedded and well-known in a region.

- Discretionary direct short-term intensive direct support from an RPC could be of benefit for some children. Some RPCs felt that having the flexibility to work with some children would have improved outcomes for those children. However, this view should be weighed up against the need to deliver the vital strategic component of the RPCs’ role.

- Awareness-raising by RPCs of the Section 45 defence could be improved. Despite RPCs’ efforts to raise awareness amongst Crown Prosecution Service teams and courts, stakeholders felt that progress had been slow compared to the RPCs’ ability to raise awareness in other areas. While many of the reasons given were considered external to RPCs’ efforts, stakeholders considered improved awareness-raising of the Section 45 defence an important next step in training and awareness plans.

- The reach and impact of RPCs could be increased. Front-line staff highlighted that heavy workloads had often prevented take-up of RPC support. There were examples of RPCs developing training material such as handout training tools, more of which could be developed to help to mitigate the impact of tight resourcing or high staff turnover. Such workarounds could help to enhance the impact of RPCs’ work.

- More co-ordinated communication could improve understanding of the RPCs’ role. When RPCs were introduced in initial early adopter sites, some stakeholders felt that there had been a lack of communication about the change in model and the reasons behind it. As the ICTG service is rolled out nationally, more co-ordinated communication across relevant services could help to improve awareness and implementation of the Service.

- Mapping out regional needs helps RPCs to tailor their support to local need. Regions have varying levels of awareness of exploitation, as well as varying services in place to support victims. By investing time to identify where and how the RPCs’ role would benefit each local authority in their region, RPCs can better adapt the level and type of support to the needs of the local authority.

- Adapting the model to local contexts could improve coverage of the ICTG service. It may be useful to consider placing more than one RPC in areas of greater need. Such adaptations of the RPCs’ role to local contexts may improve coverage of the Service and help RPCs to balance their work.

1. Introduction

The Home Office and Ipsos MORI jointly conducted the assessment of the Independent Child Trafficking Guardian service (ICTG) Regional Practice Co-ordinators’ (RPCs’) role. Ipsos MORI was commissioned by the Home Office to conduct a qualitative assessment of the delivery and impact of the RPCs’ role since its first introduction in October 2018. The Home Office was responsible for the quantitative element of the evaluation using data collected by Barnardo’s. This initial chapter provides background context to the ICTG service model, a description of the RPCs’ role, as well as the aims and objectives of this assessment.

1.1 Policy context

The Modern Slavery Act, introduced in England and Wales in 2015, provides the policy framework and dedicated legislation for dealing with modern slavery. Section 48 recognises a requirement for the provision of services that address the specific needs and vulnerabilities of child victims of modern slavery. Section 48 introduced the role of Independent Child Trafficking Advocates (ICTAs) to provide an independent source of advice and advocacy for trafficked children. Following the Independent Review of the Modern Slavery Act 2015, ICTAs were renamed ICTGs in July 2019 and will be referred to as such throughout this report. The ICTG service is currently delivered by Barnardo’s, financed by a grant from the Home Office. The Government’s work on ICTGs continues to be informed by both recommendations from the Independent Review and learning from the evaluations of the early adopter sites.

1.2 The Independent Child Trafficking Guardians service and Regional Practice Co-ordinators’ role

ICTGs were introduced to three initial adopter sites in January 2017: Greater Manchester, Hampshire and the Isle of Wight, and nationally in Wales. Based on interim findings of an evaluation of the ICTG service running in the three initial adopter sites during 2017 and 2018, published in July 2018 by University of Bedfordshire and the Home Office,[footnote 11] the Government announced that it would revise the ICTG model. The Government also expanded the service to three later adopter sites: West Midlands Combined Authority in October 2018, followed in January 2019 by the East Midlands and in April 2019 by the London Borough of Croydon.[footnote 12] The final evaluation of ICTGs in the three initial adopter sites conducted across a two-year period from 2017 to 2019 was published in July 2019[footnote 13] and supported the interim findings.

As part of the revised model, provision of the ICTG service underwent a change of structure in response to a key finding from the 2019 evaluation of the Service. This was that child victims of UK nationality have different needs to victims of non-UK nationality.[footnote 14] In particular, the qualitative findings from the evaluation suggested that UK children were more likely to have existing support networks on referral, which comprised family, friends, community and professionals. In contrast, the networks of non-UK children were often less developed, which meant that ICTG Direct Workers[footnote 15] could have a more active role. Therefore, the revised service model continues to provide one-to-one support for children without a figure of parental responsibility for them in the UK with an appointed Direct Worker. It also introduced RPCs, whose role is to encourage a multi-agency approach to support children with a figure of parental responsibility for them in the UK.[footnote 16]

The RPCs’ role is designed to advocate for and ensure that the ‘best interests’ of a trafficked child are being considered in the decisions made by public authorities. This is achieved through a number of related functions, including:

- bolstering multi-agency working in relation to trafficked children and fostering connections between services;

- offering consultation and support to front-line workers to complete National Referral Mechanism (NRM)[footnote 17] referrals where appropriate; and

- offering independent advice and consultation to other professionals working with the child, including social workers, youth offending officers, and police forces.

Another key component of the role is to embed best practice in the local area by:

- strategically identifying and addressing potential gaps in services; and

- delivering awareness-raising on child trafficking indicators and modern slavery, including the use of the statutory defence provided for in Section 45 of the Modern Slavery Act 2015.[footnote 18]

1.3 Research objectives

This assessment builds on the evaluation of the ICTG service undertaken by the University of Bedfordshire and the Home Office, published in July 2019. Its aim is to gain an in-depth understanding of how the RPCs’ role has been working since its introduction in October 2018, and its perceived impacts against intended outcomes.

Quantitative data is used to add further context to the qualitative findings, providing statistical information to complement the views and experiences of those interviewed.

The core objectives of this qualitative assessment are as follows.

- To understand how the RPCs’ role is delivered in the six early adopter sites (Greater Manchester, Hampshire and the Isle of Wight, Wales, East Midlands, West Midlands and Croydon).

- To explore what impacts the role has had on professionals within relevant sectors, who have had practical experience of working with an RPC in the last six months of operating the new model, and, through these professionals, the impact that the RPC role has had on children in the ICTG service.

- To explore what impacts the RPC role has had on work across the wider ICTG service.

2. Methodology

The assessment of the Regional Practice Co-ordinators’ (RPCs’) role comprises a qualitative and quantitative element. The qualitative approach was led by researchers at Ipsos MORI and involved 36 telephone interviews with stakeholders and Independent Child Trafficking Guardian (ICTG) service staff across the six early adopter sites between 18 November and 2 February 2020. Direct Workers, Service Managers[footnote 19] and RPCs were interviewed (Table 1), as well as a range of criminal justice and social care stakeholders whose role involved interaction with the RPCs (Table 2). The qualitative strand of the assessment aimed to gather experiences and perceived impacts of the RPCs’ role, and any key examples of best practice in the respective adopter sites.

The quantitative element of this research was led by Home Office researchers and involved the analysis of National Referral Mechanism (NRM) referral data and data collected by Barnardo’s detailing the characteristics of children on the RPC and Direct Worker caseloads, as well as the levels of contact RPCs have had with professionals and that Direct Workers have had with children in the ICTG service.

2.1 Qualitative strand

A purposive sampling approach was adopted,[footnote 20] within which participants must have had:

- experience of working with RPCs and children who had been trafficked or exploited as part of their professional role; or

- oversight or practical experience of working with an RPC within the last six months of operating the new model.

Stakeholders were selected from a list provided by the ICTG service to cover each area of the ICTGs’ work, including social care, criminal justice and the Single Competent Authority (SCA).

There were three key sampling criteria used to ensure a spread of stakeholders who work with RPCs:

- early adopter site;

- professional background; and

- type of role (operational or strategic).

All six RPCs were interviewed to explore their experiences and to explore similarities and differences across the sites. All five Service Managers[footnote 21] were interviewed, as well as the Direct Workers working in the three initial adopter sites. The aim was to understand how the RPCs’ role has worked with and impacted on the wider ICTG service. In addition, 10 criminal justice stakeholders (including those working in youth offending and police teams) and 11 social care stakeholders were interviewed, as well as 1 NRM SCA stakeholder.

There were difficulties encountered in interviewing some stakeholders. Strategic stakeholders were hard to reach, partly due to the limited number of strategic stakeholders received as part of the sample frame, but also due to lower response rates. This is thought to reflect:

- their low levels of interaction with the RPCs;

- the assessment coming quite early in the work and embedment of the RPCs’ role; and

- busy diaries.

There were a very low number of stakeholders received as part of the sample frame in Croydon. As such, only two interviews were achieved (both members of the ICTG service based in the borough). This was felt to reflect the later roll-out in the borough (the ICTG service was introduced in April 2019), as well as the challenges faced by the ICTG service in creating links with relevant stakeholders within the timescales of the assessment. The findings for this area are therefore presented cautiously and within this context.

Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed (following consent from all participants). Analysis was conducted throughout the study from the outset of the fieldwork period. Data, consisting of interview transcripts, detailed interview field notes, and outputs from team discussions, was reviewed to create a thematic framework based around the different aspects and outcomes of the RPCs’ role. Analysis primarily took place in Excel: field notes and anonymised transcripts were coded, reviewed and manually inputted into the thematic framework by researchers. When considering the qualitative data in the report, it is important to bear in mind the data’s descriptive and illustrative nature. These findings are based on the perceptions of the stakeholders spoken to and often relate to personal experience of working within their field and region.

Table 1: Achieved qualitative sample – ICTG service

| Groups | Locations |

|---|---|

| Direct workers | Hampshire and the Isle of Wight x1 Greater Manchester x1 Wales x1 Croydon x1 |

| RPCs | Hampshire and the Isle of Wight x1 Greater Manchester x1 Wales x1 East Midlands x1 West Midlands x1 Croydon (dual RPC and Service Manager) x1 |

| Service managers | Hampshire and the Isle of Wight, and Wales x1 Greater Manchester x1 East Midlands x1 West Midlands x1 Croydon x1 |

Table 2: Achieved qualitative sample – Professionals

| Location | Criminal justice | Social care |

|---|---|---|

| East Midlands | x1 Strategic x1 Operational |

x1 Strategic x1 Operational |

| West Midlands | x2 Operational | x2 Operational |

| Croydon | - | - |

| Greater Manchester | x1 Strategic x1 Operational |

x1 Strategic x1 Operational |

| Hampshire and the Isle of Wight | x1 Operational | x2 Strategic x1 Operational |

| Wales | x2 Strategic x1 Operational |

x1 Strategic x1 Operational |

2.2 Quantitative strand

The quantitative research used within this report was led by Home Office researchers in the Modern Slavery Research and Analysis Team, and involved the analysis of three sets of data.

- NRM data was used to compare NRM decisions in ICTG sites with the rest of the UK, as well as to estimate the number of children who fall under RPCs’ coverage.

- Data collected by Barnardo’s detailing the characteristics and status of children on both RPC and Direct Worker caseloads. This includes demographic data, as well as the primary type of exploitation that the child has been referred for. It also details the number of children who fall under both the RPC and Direct Worker caseloads. This data covers the timeframe of October 2018[footnote 22] to December 2019.

- Data collected by Barnardo’s detailing the contact that RPCs had with professionals, and the contact that Direct Workers had with children in the ICTG service. This data gives information about the type of contact that RPCs and Direct Workers had, the subject of this contact, and the type of professional this was with.[footnote 23] This data covers the timeframe of April 2019 to December 2019.[footnote 24]

All three datasets were used to produce descriptive statistics within the report, which complement the qualitative findings.

3. Background and local context

The following section incorporates qualitative and quantitative data. The quantitative data looks at the total number of children supported by Regional Practice Co-ordinators (RPCs),[footnote 25] as well as demographic information for these children and the type of exploitation that they had reportedly suffered. The quantitative data is complemented by stakeholder perceptions of trends in child trafficking across the six sites.

3.1 Number of children in the Service

Between January 2017 (when the initial adopter sites were established) and December 2019, there were 901 children supported by the Independent Child Trafficking Guardian (ICTG) service. Around 513 of the children supported were referred in the period since the first RPC was established in October 2018, up until December 2019. Around two thirds (320) of these children were supported by Direct Workers, while around one third (193) were supported by RPCs.[footnote 26]

Within this same time frame, an estimated 1,300 potential child victims of modern slavery who had a figure of parental responsibility for them in the UK were identified within the early adopter sites and therefore fell under the coverage of an RPC.[footnote 27] For a child to be included on an RPC’s caseload, the RPC must have worked with a professional or professionals on behalf of a specific child. This work may include advising first responders on a child’s NRM referral or advising professionals on the child’s safeguarding or support options. This means that RPCs worked with professionals to support 15% (193 out of 1,300) of the children under their coverage, although RPCs are likely to have had a much wider indirect influence, through the general advice and guidance that they provided to front-line staff.

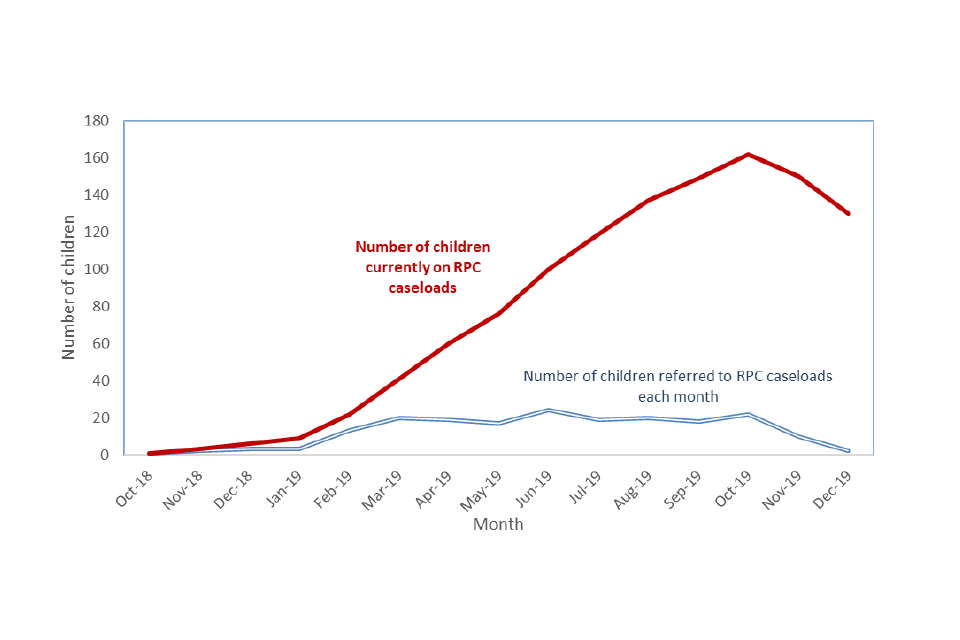

Figure 1 displays the number of children on RPC caseloads between October 2018 and December 2019. It shows that the number of monthly referrals to RPCs increased between January and March 2019, and then stayed fairly level until October 2019, where it decreased. Alongside this, the number of children supported by RPCs steadily increased from January 2019 to October 2019, where the number then began to decrease at a similar rate. Anecdotal evidence from Barnardo’s suggests that the decrease may partly be due to seasonal trends, as well as RPCs adopting a more strategic approach to their role over time. As RPCs have a finite capacity to support individual children, focus was shifted towards embedding knowledge and best practice on a more strategic level, rather than supporting individual cases. This was supported by the ICTG service, given the high number of children identified and the growing need for awareness of child trafficking within regions.

Figure 1: Total children on RPC caseloads,[footnote 28] and number of referrals to RPC caseloads, October 2018 to December 2019

3.2 Trends in child exploitation

3.2.1 Trends in exploitation type

Between October 2018 and December 2019[footnote 29] around three quarters (75%) of the children on RPC caseloads were primarily exploited[footnote 30] through child criminal exploitation (CCE), while almost all the remainder (24%) were primarily exploited through child sexual exploitation (CSE). [footnote 31] This contrasts with children supported by Direct Workers, where the most common primary exploitation type was labour exploitation (47%) followed by CCE (35%), and CSE (11%).[footnote 32]

While the quantitative data does not record types of CCE, stakeholders reported CCE as ranging from ‘County Lines’,[footnote 33] burglary, car theft and small-scale robbery (from sheds) to pickpocketing or shoplifting. The qualitative interviews suggest that CCE was experienced across all areas but there was some prominence in urban areas where gangs and criminality within communities was prevalent. County Lines was mentioned as a UK-wide issue, although stakeholders felt that there were also increased trends of drug running on small geographical scales, such as between streets, boroughs and towns.

3.2.2 Demographics and associations to exploitation type

Most children on RPC caseloads were UK nationals (90%), male (71%), and aged between 15 and 17 (76%)[footnote 34]. The proportion of males ranged from 83% in Greater Manchester to 54% in Wales,[footnote 35] while the proportions for age and nationality were similar in each early adopter site. The range in the proportion of males and females across sites associates strongly with exploitation type, with Greater Manchester having the largest proportion of children primarily exploited for CCE (88%) and Wales the largest proportion of children primarily exploited for CSE (43%).[footnote 36]

During the same timeframe, children supported by Direct Workers had relatively similar characteristics to children referred to RPCs. They were predominantly aged between 15 and 17[footnote 37] (78%) and male (76%), although a much smaller proportion of children supported by Direct Workers had a UK nationality (12%). The most common nationalities of children supported by Direct Workers were Vietnamese (18%), Sudanese (13%), UK nationals (12%) and Albanian (9%).[footnote 38]

The proportion of males and females varied from one site to another among children supported by Direct Workers, in a similar pattern to the children on RPC caseloads. While each site was predominantly male for children on Direct Worker caseloads, this ranged from 95% in Croydon to 59% in the East Midlands.

There was also a lot more variation in the nationalities of children supported by Direct Workers compared with children on RPC caseloads. Direct Workers in the East and West Midlands predominantly supported Vietnamese children. However, the most common nationality of child supported by Direct Workers in Hampshire and the Isle of Wight was Sudanese (62%), while in Croydon it was Albanian (50%), Wales it was UK children (38%), and Greater Manchester it was both UK children and Gambian children (19%).

Labour exploitation was the most common form of exploitation in all sites except Croydon and Greater Manchester, where CCE was more common.

Stakeholders reported that there was some degree of association between certain types of exploitation and different demographics. The quantitative data shows that there was a strong association between primary exploitation type and gender for children referred to RPCs. Almost all males (98%) were referred to RPCs primarily for CCE. While the association between gender and exploitation type for females was slightly more mixed, it was still strong, with 80% of females referred primarily for CSE and 20% for CCE.[footnote 39] However, stakeholders across the board were keen to emphasise that both CSE and CCE occur across genders and that there is a tendency among services to align CCE with young males and CSE with females. Stakeholders also shared concerns that there was an under-reporting of CSE amongst male children.

However, for children supported by Direct Workers, the strength of the relationship between gender and exploitation type was less prominent than with children supported by RPCs. Males were most commonly referred for labour exploitation (52%), followed by CCE (42%). Similar to children supported by RPCs, females supported by Direct Workers were primarily exploited through CSE (45%), although a high proportion (25%) were also exploited through labour exploitation.[footnote 40]

For other demographic characteristics of children referred to both RPCs and Direct Workers, there was no noticeable association with primary exploitation type.

3.2.3 Risk factors

Stakeholders reported the factors that could make children vulnerable to exploitation spanned nationalities. However, there was a recognition that some factors could be more applicable to UK versus non-UK nationals. For example, children of non-UK nationality could be trafficked into the UK, which made it harder for UK-based services to identify their exploitation.

Across all nationalities of children, stakeholders believed the circumstances that hinder stability in a young person’s life could increase their vulnerability to exploitation. This was recognised by front-line staff within and outside of the ICTG service, as well as by stakeholders in more strategic positions. Access to education was key, with stakeholders noting that children who were out of education, had low attendance at school or were not in mainstream education could be more vulnerable. Stakeholders reported that this could make children more exposed to potential exploiters and made it harder for services to track the children’s whereabouts or provide an appropriate support structure. Instability at home was also seen as an important factor. Children could experience instability if they did not feel they had a safe home environment, which made it difficult for services to include family in any front-line interventions.

In some cases, stakeholders noted the vulnerability of children with learning disabilities and/or mental health issues, or those with previous experience of trauma.

Stakeholders also highlighted examples where children were being exploited by their own families or local communities. Family ties made it difficult to pull the child away from harmful situations especially where trust was fostered between those children and their exploiters. Stakeholders reported that this could be the case with British children, particularly in relation to generational criminal activity or gang ties, which pose a risk factor for some young people. This was particularly noted by stakeholders in social care, youth work, those working with local authorities and those within the ICTG service who have a knowledge of issues in their local area. This was seen to be the case particularly in urban areas where gang activity was more prevalent, or where gang dispersal programmes had localised criminal activity in surrounding areas and passed on gang ties to children. It was also noted that once exploited for criminal activity, especially through gangs, young people might have outstanding ‘debts’, which is part of a model that exploiters use to keep them under the control of gangs.

3.2.4 Geographical factors

Stakeholders reported that geographical factors could form the basis for the type of trafficking and exploitation that developed in an area. Borders were a key example of this. For example, ports seeing children being trafficked from outside of the UK (Portsmouth and Southampton), or borders between smaller towns and larger cities (North Wales linking into Cheshire and Merseyside; Greater Manchester and City of Manchester; Birmingham and surrounding towns) provide the setting for the type of trafficking prevalent in that area.

Stakeholders reported that County Lines was seen to affect an area in different ways, depending on whether it was defined as an ‘exporter’ or ‘importer’ area. In urban ‘exporter’ cities such as London, Portsmouth, Manchester and Cardiff, children were seen to move in and out of the region, but stakeholders reported that it was also common to see children being moved locally within boroughs or across streets. In the cities or towns that were receiving points, children from all over the UK could be found within them. As the impact on an area is exacerbated by networks of easily accessible outer regions or smaller towns, the East and West Midlands and Greater Manchester were seen to be particularly impacted by County Lines, as well as areas such as Portsmouth and North Wales. Stakeholders report that children who live along these lines were also at risk of missing out on services due to cross-border communication and commissioning challenges, as they are likely to be exploited in areas away from where they live.

3.3 Regional context and differences in service delivery

Stakeholders mentioned some key contextual issues and differences in local delivery across the early adopter sites, which were relevant to the implementation and delivery of the RPCs’ role.

Stakeholders across all regions and agencies noted a better familiarity across the board in their areas with CSE compared with CCE. Stakeholders felt that awareness and capacity for response for CSE was generally more established. Many stakeholders reported misperceptions about CCE within certain agencies – especially police teams – where children were still being viewed as choosing to engage in criminal activity. In regions with more established exploitation services, stakeholders felt there were more instances of interlinked CCE and CSE provisions and a continual progress towards taking a holistic safeguarding approach.

Stakeholders also mentioned a disparity between urban and rural areas across the regions, with urban areas generally benefitting from more established services and availability of resources. Larger urban cities (such as Cardiff, Birmingham, City of Manchester and Portsmouth) often already had funding streams or specialised teams set up to focus on child trafficking prior to the ICTG service.

Rural deprivations were cited to be a core issue in some areas. For example, infrastructural deprivations such as access to healthcare and lack of services and broadband were fundamental barriers to the development of services or outreach of services generally in rural areas.

Greater Manchester was seen by stakeholders as an area with highly developed and interlinked services for responding to child trafficking and exploitation. This is mainly due to a network of Complex Safeguarding Teams (CSTs) set up within each of the ten local authorities in the region, which act as a combined local authority. These teams comprise social workers and other specialists within police teams, and have varied levels of support from multidisciplinary agencies depending on the team. They are responsible for cases that involve child exploitation (criminal and/or sexual exploitation) and are used primarily to manage CSE cases, but have also gained expertise and cases in CCE. The teams draw on local resources and regularly share information and create training initiatives – all of which can be disseminated across all the CSTs.

4. Delivery of the Regional Practice Co- ordinators’ role

This chapter reports on how the Regional Practice Co-ordinators’ (RPCs’) role has been working across and within the early adopter sites and discusses the success factors and challenges that were found to impact on the delivery of the role. It is structured around some of the key aims of the role:

- supporting the Independent Child Trafficking Guardian (ICTG) service;

- fostering collaborative working among partner agencies;

- awareness-raising and upskilling;

- identifying service gaps; and

- providing in-depth advice and consultation to front-line professionals

4.1 How the Regional Practice Co-ordinators’ role has worked

The RPCs’ role was not designed prescriptively, which meant that while the role shared some core functions across regions, RPCs were able to adapt methods of delivery depending on the needs of the area. The governance structure of each region, including the type and nature of services already in place to support children who had been trafficked, also had a bearing on how the role was implemented. Although specifics could vary, the RPCs’ role generally involved the following functions – sometimes in sequential stages:

-

delivering an introduction of the ICTG service to local authorities;

-

local area mapping to identify need and opportunities;

-

awareness-raising of the role to relevant services (where needed);

-

offering awareness-raising sessions to local services;

-

establishing multi-agency links and integrating with other service offers; and

-

being a contact for case-by-case support and advice where needed.

In later adopter sites where the ICTG service did not already have an established presence, the elements were sometimes implemented in stages and revisited on a regular basis, particularly for larger geographical areas. An introduction to the ICTG service as a whole was seen as needed for some local authorities as a baseline before links could be formed with relevant agencies. In regions or local authorities with already-established child trafficking services, RPCs were seen to embed within agencies and input into local system change plans.

Ultimately, each key aspect of the RPCs’ role was interlinked. Establishing their presence in local areas and building relationships with local services created opportunities for RPCs to deliver awareness-raising sessions and case-by-case support to professionals. In addition, cross-regional links were seen as an important method of identifying and plugging gaps within services.

Table 3 shows the main reasons that RPCs had contact with other professionals in order to support children on their caseloads.[footnote 41] National Referral Mechanism (NRM) support was the most common reason for meetings, which may involve the RPC helping professionals to gain a better understanding of the NRM process,[footnote 42] as well as supporting them in gathering information and following up on referrals. Safeguarding was the second most common reason for contact given, which involved discussing a child’s immediate safeguarding concerns. The third most common reason was social care, where RPCs would support the work of a child’s social worker in areas such as safety planning, preparing paperwork for court, and looking through relevant legislation.[footnote 43] These three reasons combined accounted for just over two-thirds of the contact that RPCs had with other professionals on behalf of children.

Table 3: The top five reasons RPCs had contact with other professionals, by proportion of total contact[footnote 44]

| Reason for contact between RPCs and professionals | Proportion of total contact |

|---|---|

| NRM support | 37% |

| Safeguarding | 23% |

| Social care | 16% |

| Criminal justice | 8% |

| Child safety | 7% |

4.1.1 ICTG service working

Working with Direct Workers

Overall, stakeholders reported that RPCs rarely collaborated with Direct Workers on caseloads.[footnote 45] Where this did happen, the role of the RPC would primarily be within the referral phase (identifying children who the Direct Worker might support). RPCs also occasionally offered ad hoc advice and consultation to Direct Workers, particularly around criminal exploitation and court cases, potential outcomes at court, and dealing with judiciary professionals.

“[The RPC and I] are doing different jobs in different places… unless there’s a specific issue that I need to ask the RPC about then our jobs don’t normally seem to cross.” (Direct Worker)

Direct Workers and RPCs indicated that they felt the distinction of their roles was very clear, apart from cases early on when the revised model was first introduced, where there was uncertainty around the specifics of the definition of parental responsibility. Given that the type of support the child received was contingent on this definition (which could vary on a case-by-case basis), there was some deliberation on who should be best placed to work with the child.

As part of their strategic oversight, RPCs would identify training that Direct Workers could deliver, or opportunities to visit other agencies.

Working with Service Managers

Unlike the limited interaction between RPCs and Direct Workers, Service Managers reported working frequently with RPCs. Most said that they had regular contact with RPCs over the phone or by email and through monthly supervision and team meetings. Frequent contact between RPCs and Service Managers enabled ‘live’ feedback on successes, concerns or general updates on ways of working within agencies.

Service Managers would often attend high-level regional or strategic meetings, whilst RPCs generally sat in both operational and strategic meetings. In this way the two roles could complement each other, having a combined oversight of how both levels were working in their regions and how they impacted one another. RPCs were also able to escalate concerns through the Service Managers or request their manager’s presence at meetings if it was felt that a more senior presence was needed.

Working as a team

At a regional level, the ICTG service reported that it would often work flexibly within their teams to meet the needs of their region in the best way. For example, in larger regions, where there may be more local safeguarding boards and modern slavery forums, the Service would work collaboratively to ensure that they covered the whole region. Individual members of the ICTG service said that they were prepared to work tactically to identify how they could cover for each other or align timetables with activities (planning awareness-raising sessions and meetings around the same time to reduce the need for repeated movement across the country). They would also decide who would be best placed to visit which area, based on pre-existing relationships with partners.

Service Managers and RPCs said they would then share responsibility to identify appropriate agencies to engage, as well as initiatives or training opportunities where they thought that the input of the ICTG service would be valuable.

4.1.2 Identifying gaps in child trafficking services

ICTG service mapping

RPCs would work to identify gaps within the service provision in their region by undertaking regional mapping in partnership with the Service Manager and Direct Workers. RPCs reported that this could involve regular (often quarterly) mapping and planning meetings where team members would assess the types of trafficking across the region and identify risks, as well as potential gaps in awareness and service provision within partner agencies.

ICTG service professionals said risk analysis could involve using ICTG referral data (including types of children being referred to the RPC) and NRM referral data to map areas with a high risk of certain types of exploitation. ICTG teams in some areas would then map these risk ‘hot spots’ to the corresponding levels of engagement and service provision amongst partners within those areas – identifying opportunities for RPCs to invest further time, and what these actions should be. For example, an ICTG team in one region was looking to link in with health professionals, particularly Accident and Emergency hospital staff and paramedics, who might come across at-risk children without knowing the indicators or signs of trafficking.

It was reported that while formal reviews were quarterly, service mapping was a continuous process with the team regularly monitoring and providing feedback on how successful engagement activities had been.

Identifying gaps in provision within services

Stakeholders across the different regions and agencies reported that RPCs would regularly inform them of wider national or regional trends to help them to identify gaps within their service. This could sometimes happen on a more strategic level, with RPCs encouraging and supporting social care and youth justice teams to analyse their own available datasets (for example, patterns of caseloads) to identify gaps within their service. On a more ad hoc basis, there were examples of RPCs who would alert teams to emerging hot spots or risks to enable them to mobilise a response in real time.

In areas with more established exploitation services, stakeholders noted that RPCs would work in close partnership with them. This could involve identifying areas where exploitation services may need more specialised or bespoke training, for example, advanced or refresher NRM training that RPCs could signpost them to, or awareness- raising sessions delivered by the RPCs themselves. In Greater Manchester, the RPC fed into the strategic peer review meetings co-ordinated by the Complex Safeguarding Teams. The primary purpose of these meetings was to consider how support services for exploited children could be improved by reflecting on how children and young people were responded to in the region.

Cross-working amongst RPCs

RPCs specified ways in which they worked as a team to ensure that individual regions were linked into the patterns of exploitation nationally. RPCs across regions would have regular contact in the form of monthly phone meetings and regular away days. They used these sessions to discuss risks and trends in other regions and share best practice to ensure a joined-up approach across the Service.

A close working relationship was also found between RPCs of adjoining regions, such as the East and West Midlands. RPCs would share intelligence or information where children living in their respective regions had been identified or involved in services in the other.

4.1.3 Fostering multi-agency, cross-region working and information sharing

Identifying and addressing blockages

The RPCs’ role was expected to identify and break down barriers to multi-agency working within and across regions. In particular, although many police and social care teams worked well together, some teams faced difficulties working together to support children who had been exploited. Where this was the case, stakeholders reported that RPCs worked to reduce friction. RPCs would work to dispel tensions by organising joint meetings between teams to encourage agreement on next steps. There were also examples of RPCs facilitating an escalation procedure within modern slavery police teams for social workers to use if they needed information urgently. Where there had been instances of duplicate NRM referrals being raised due to lack of communication between police and social care, RPCs organised a multi-agency NRM working group to ensure a more joined-up approach.

Multi-agency meetings

An important way that RPCs created links between the ICTG service and other agencies was by attending both strategic and operational multi-agency panels.

At a strategic level, the number and type of meetings RPCs attended depended on the structure within regions or local authorities. Some local authorities had their own Multi- agency Child Exploitation (MACE) strategy meetings whereas others had cross-area or cross-regional boards. Having a consistent presence on these strategic and planning boards across the region reportedly enabled the RPC (and the ICTG service) to forge links between agencies and improve information sharing across different local authorities. Although there was an acknowledgement that this was still a work in progress, stakeholders both within and outside of the ICTG service felt RPCs had helped to break down siloed-thinking in some areas to foster a more collaborative atmosphere.

RPCs in all regions would also attend relevant operational multi-agency meetings, where the risks and needs of vulnerable children or young people would be discussed. Some local authorities, particularly in large urban areas, would have a regular meeting focusing on exploitation and trafficking, for example, Missing, Exploited and Trafficked (MET) meetings and MACE meetings. Other local authorities would have more general safeguarding meetings of which child trafficking and exploitation would be one of the items covered, for example, Multi-Agency Safeguarding Hub (MASH) meetings. In smaller regions, such as the West Midlands or Hampshire and the Isle of Wight, the RPC would attend all key operational meetings. In large regions with more local authorities, such as Wales, RPCs said they could struggle to attend operational meetings every time.

Stakeholders outside of the ICTG service, particularly those in social care and youth work, saw an RPC presence at these meetings as an important platform to inform and advise on whether children had been exploited and to offer suggestions for preventative measures. RPCs would highlight indicators of exploitation in cases where other professionals might not be familiar with them, and would advocate for children as victims, such as by challenge language used that would suggest that children are perpetrators.

“[The RPC] is an integral part of that multi-agency approach to what the circumstances might be… giving ideas, giving thoughts and sometimes it’s almost a critical friend role, thinking about ‘have we thought about doing this for a young person?’… and because we have those individual discussions in those case panels, it’s about [checking] whether we’ve got those plans right, whether there’s anything else we need to think about doing and putting [other agencies] in touch with the social workers, that kind of safety and risk planning.” (Operational stakeholder, social care)

Operational stakeholders in the different regions also saw RPC attendance at these meetings as one of the most important ways of creating relationships and links between the ICTG service and individual front-line staff. RPCs would create links between key sectors such as social care, youth offending and criminal justice, as well as health, housing, adult services and education. Stakeholders mentioned that RPCs not only forged relationships between the ICTG service and partner agencies, but initiated a network of communication, connecting different services together by passing on contact details and sharing information. This was also the case where there was a lack of communication between the same services across different local areas or boroughs. For example, one RPC encouraged local police teams to liaise with other areas and shared key contacts to facilitate conversations in order to initiate more joined-up working and intelligence sharing.

RPCs would also use attendance at exploitation panels to raise specific concerns and identify gaps in service provision. For example, in one area, where a child with a positive conclusive grounds decision had received a long custodial sentence, the RPC raised the lack of the use of the Section 45 defence of the Modern Slavery Act 2015 at an exploitation meeting. The issue was identified as a potential gap in understanding among the judiciary and Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) with regards to criminal exploitation and the potential for defendants in criminal proceedings to benefit from the appropriate application of the defence under Section 45. This subsequently led to plans for RPC awareness-raising with the CPS and the judiciary to help to ensure more appropriate handling of positive NRM decisions and the application of the Section 45 defence.

Case-by-case basis

Stakeholders noted how RPCs would broker conversations between agencies for individual children. This could involve:

- identifying which agencies should be included;

- ensuring that relevant representatives were invited to meetings or copied into emails;

- seeking out input from partners to draft safeguarding plans; and

- working to assign the right lead professional (such as social workers or Youth Offending Team [YOT] workers) to a child – this was seen as particularly important in cases where there were multiple services involved, which could lead to duplication.

“For me it’s finding the right contacts and making sure that they’re all part of [the safeguarding] plan. We can often have situations where we’ve got different services on the ground. It can become overwhelming and it’s about making sure that we’ve got the right people involved at the right time, and that we’ve done all the things that we need to and that’s …what [the RPC] helps us to do.” (Operational stakeholder, social care)

For social care professionals who specialised in work with exploited children, the RPC would sometimes form more of a partnership; regularly liaising and identifying opportunities for information sharing and mutual case referrals to the right services.

“Some of the children I come across could potentially be exploited or have been exploited in the past and that’s why our relationship works really well because we can…bounce the names off each other, [the RPC] can refer in to me and vice versa.” (Operational stakeholder, social care)

Embedding within key teams

In areas where experience and knowledge of child trafficking was high, RPCs would sometimes embed within teams to avoid duplication, and co-deliver pieces of work. For example, RPCs were embedded in some YOTs in larger cities and within social care teams specialising in child exploitation. Stakeholders in these statutory child service and YOTs felt that this helped to foster information sharing between themselves and the ICTG service, ensuring consistency of messages and greater collaboration. Although some social workers within specialist teams felt that some duplication of their work and ICTG service activity was unavoidable, embedment in teams was seen to diminish the overlap between these services.

4.1.4 Awareness-raising

Stakeholders mentioned a wide range of different ways that RPCs would raise awareness and train and upskill services within local authorities, both at a strategic and operational level.

“Doing the work has encouraged more awareness-raising I’ve built a reputation as being the woman to ask…. I’ve had loads of phone calls that seem to be out of the blue…Word is slowly getting around that, actually, I’m doing a good job and that I know what I’m doing and maybe they don’t know as much as they thought they did [about child trafficking].” (RPC)

Raising awareness about indicators and types of child trafficking and exploitation

At a strategic level, RPCs designed and delivered awareness-raising sessions on indicators and types of child exploitation to supplement the training that professionals receive from their organisations. The type and length of sessions ranged from short refresher courses to longer and more interactive workshops, including group work and use of videos.

Sessions were delivered to various agency partners such as youth offending, criminal justice, social care and exploitation teams. There were some examples of RPCs delivering sessions to wider multi-agency partners, such as Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS), healthcare professionals, education professionals, counsellors and therapists.

In large regions, RPC awareness-raising sessions on indicators of child exploitation would sometimes be primarily targeted towards key partners or team managers. This was done in the hope that the training would be embedded through a trickle-down effect. For example, in one area, ‘train the trainer’ sessions were run with members of a specialist exploitation team to maximise reach and marry up the training packages of both the ICTG service and specialist teams.

“We’re really clear as a service [that] we don’t want to be that rescue organisation where people come to us for everything. It would be much better that we invest the time out in the regions, [and that] we build people’s confidence, their capacity, their ability to do some independent learning themselves as well.” (Service Manager)

Although the content of the awareness-raising sessions varied, stakeholders across agencies said they could cover:

- best practice around spotting indicators for both child criminal exploitation (CCE) and child sexual exploitation (CSE);

- tips on how to approach culturally sensitive issues;

- local case studies or examples to help to apply these indicators in practice; and

- wider contextual and national information, such as national best practice models and contextualised safeguarding.

“[The training] included: ‘Here’s what we look out for. Here are some cases in the area that have happened, and signs and symptoms of what exploitation may look like, act like, or sound like, and what processes needed to be put into place for young people and for adults’. [The RPC] did this quite extensive training on that.” (Operational stakeholder, criminal justice)

Training content would also be tailored to the awareness levels of individual teams and contextual factors of the local area. For example, in more rural areas where awareness of both CSE and CCE was lower than in the cities, sessions would be more introductory. In areas where familiarity with CCE was lower than CSE, the training would focus on how to understand exploitation in the context of CCE as well as how CCE and CSE could be interlinked.

Stakeholders also observed that RPC awareness-raising sessions included sections aimed at tackling local or regional misperceptions or knowledge gaps. For example, challenging the assumption that British children were less likely to be exploited in that area or that County Lines was the only form of CCE in the area. There were also examples of RPCs delivering police-specific sessions on the language to use when dealing with CCE cases to tackle stereotyping and use of victim-blaming language.

Stakeholders also reported that RPCs developed or signposted them to pamphlets and information sheets to refer to when assessing cases. Youth offending officers in particular mentioned they had received toolkits on CCE and CSE to identify warning signs and the stages of exploitation amongst the children they work with.

RPCs also raised awareness about indicators by challenging language at multi-agency panels or meetings. Stakeholders mentioned RPCs would reinforce and refocus the conversation on child exploitation indicators, highlighting indicators that other professionals may not have seen and to ensure that appropriate language was used.

Raising awareness of the Section 45 defence

Stakeholders reported that RPCs’ awareness-raising would involve an introduction or description of the Section 45 defence within the Modern Slavery Act 2015. Areas covered included:

- what the law means;

- when it can and cannot be used; and

- myth busting if there was a sense that it was a ‘get out of jail free card’.

Such topics were covered as part of introductory sessions hosted by RPCs in order to complement the existing training that stakeholders received from their own organisations.

Stakeholders reported this training had been delivered as part of wider awareness and upskilling packages to first responders (including police teams), but in some areas RPCs had delivered introductory awareness-raising sessions to some CPS staff, magistrates and the judiciary. RPCs in other areas had also identified this as a next step in their training plans.

Awareness-raising about the NRM

Formal NRM awareness-raising sessions were delivered to first responders by RPCs across the regions, supplementary to training provided to first responders by their own organisations. Stakeholders reported that these sessions covered topics such as:

- the types of information needed for an initial referral;

- the steps of the process including reasonable grounds and conclusive grounds decisions;

- example case studies; and

- a practical exercise for participants to complete referrals.

RPCs would also develop handouts and toolkits to support professionals when submitting an NRM referral. This included:

- a ‘crib sheet’ or short overview of the benefits of the NRM for the child, parent and professionals (to hand out to wider agencies including health, mental health and education); and

- a toolkit for first responders to refer to, including an indication of when further information was needed at different stages.

“[The RPC] was really helpful in giving us…a table to put all of that information in, and what’s expected, what [the Single Competent Authority] expects. So, it’s clear for them, but also clear for us. I’ve shared that with the team, which has been really helpful…so that actually when you send it off to them it’s clear, and you’re not missing any gaps which potentially you may have without realising.” (Operational stakeholder, social care)

There were some instances of RPCs organising and delivering multi-agency NRM awareness-raising sessions. This reportedly meant that different teams (such as social care and the police) could feel more unified in the process. Stakeholders from the social care sector reported that they now shared information more freely with other teams and felt more confident in having constructive conversations with police forces.

“[The RPCs were] having sessions with us which has then made us feel more confident and clearer in what we’re saying from our social care perspective so that then when we are having conversations with [the police] you kind of know what you’re talking about a bit more and you’ll feel more confident in your argument basically for why an NRM [referral] is needed or why you think something.” (Strategic stakeholder, social care)

Although NRM awareness-raising sessions were predominantly delivered to first responders, there were also some initial sessions to the judiciary, magistrates and the CPS in the East and West Midlands, to complement existing formal training within these organisations. Stakeholders in these regions reported that this was to explain:

- how the NRM process works;

- what it means in pre-sentence reports; and

- how this might relate to children in court who may have been exploited or trafficked.

4.1.5 Supporting front-line professionals in relation to an exploited child

Supporting professionals to identify indicators of child exploitation

There were many examples given of RPCs providing in-depth advice and guidance to front-line staff about the children they were supporting. This could take the form of one-off or ongoing emails, and face-to-face and telephone guidance where required. The quantitative data shows that a large proportion of the contact[footnote 46] that RPCs had with other professionals to support a child was with front-line workers, especially social workers (34%), YOTs (14%) and the police (10%). RPCs reportedly also often attended relevant individual risk-management meetings, child strategy meetings, Child in Need meetings or child protection conferences to ensure that they understood the context. In some areas, RPCs would set up regular clinics within local authority teams, where front-line staff could raise questions or requests for help.

The most common reasons RPCs contacted other professionals were:

- to support work related to the child’s NRM referral (37%);

- to discuss the safeguarding of the child (23%); and

- social care needs (16%).

The nature of this support tended to depend on the professional working with the child, and the circumstances of the child they were working with. For professionals with a low awareness of potential child exploitation indicators, RPCs would help them:

- to determine whether exploitation was involved;

- ensure that professionals were signposted to the right support; and

- advise on next steps and options available to professionals, including what disruption tactics police could use to prevent exploitation.

“I give advice on some of the meetings and I’ll get a few phone calls [about] their concerns that perhaps the police aren’t pursuing the full range of disruption tactics which could be used, or they are not considered trafficking offences.” (RPC)

Supporting front-line staff throughout criminal proceedings

Youth offending practitioners reported that RPCs would advise throughout the court process on how to recognise cases of CCE. ‘Criminal justice’ was the subject of 8% of all contact between RPCs and other professionals. This would involve the RPC providing guidance on how to word or frame pre-sentencing reports to ensure that the court was aware of the circumstances and level of exploitation faced by the child. In some cases, youth offending workers said that this included advocating for the use and application of the Section 45 defence of the Modern Slavery Act 2015 in the pre-sentencing report, and ensuring that individuals such as YOT members were applying it correctly.

Supporting front-line staff with NRM referrals

Stakeholders also reported that RPCs delivered significant hands-on support to front- line staff in youth offending, social care and police teams when referring to the NRM. This support could involve:

-

step-by-step guidance on the referral form;

-

advising on the types of information, language and evidence needed; and

-

reviewing forms before submission.

This is reflected in the quantitative data, as support with NRM referrals was given as the most common reason that RPCs contacted other professionals on behalf of a child (37% of all contact).

Participants also said that RPCs would co-ordinate information for NRM referrals where multi-agency input was needed. RPCs were seen by some to be an important conduit between social care and the police for NRM referrals. RPCs would help social care teams to reach the right police officers, gather the information needed and advocate for the need of an NRM referral if there were disagreements between services.

“I think part of our role is brokering those discussions and helping people understand both sides of that discussion, and really trying to help people pick what that means to everybody involved and still recognising that an NRM might need to go in even if not everybody around the table agrees that the young person hold[s] a particular status or not.” (Service manager)

Supporting front-line staff throughout NRM decisions

Some stakeholders, notably those in social care and youth offending, gave examples of when RPCs regularly checked in with relevant agencies and followed up with the SCA. A tenth (10%) of the contact RPCs had with other professionals in support of a child was with NRM decision makers in the SCA.

“[The RPC is] really positive in actually updating me almost every week … saying: ‘Okay, I’ve changed it a little bit more. Can you just give me an update on has anything changed? Do I need to update the NRM further in terms of further information that’s been received from your end, etc?’” (Operational stakeholder, social care)

RPCs would also advise first responders to keep records of updates on the case to ensure that they had enough information to respond to questions from the SCA over the decision period. Professionals also mentioned RPCs had advised them on whether to approach the SCA with a challenge to a negative NRM decisions and helped co- ordinate the approach if needed – identifying what evidence should be clearer or sharper and co-ordinating information from other agencies.

“She advised us to keep notes of every single encounter, every text message from that point on just in case [the SCA] needs that information. So, she kept us, kind of, in the loop on what would happen afterwards as well.” (Operational stakeholder, youth offending)

4.2 What factors led to success in the Regional Practice Co- ordinators’ role?

Where the RPCs’ role had worked well, the skills and expertise of the RPCs themselves, as well as any prior connections formed in previous roles were seen as important contributing factors. In particular, the ability to build relationships with different agencies and local authorities was seen as a key part of successful implementation and delivery, as this enabled the RPCs to deliver other aspects of their role (supporting and awareness- raising among professionals). Alongside the relationship-building skills of the RPCs, the strategic and independent nature of the role, as well as the openness of local authorities, were seen as important enablers to the role working well.

4.2.1 Regional Practice Co-ordinators’ knowledge, skills and experience

RPCs’ expertise

Both operational and strategic stakeholders gave positive feedback about the depth and breadth of knowledge offered by RPCs on all relevant forms of child exploitation. It was felt that they brought specialist expertise above and beyond services already in place and enabled Direct Workers to have a greater focus on immigration procedure and law.

“It’s the high level of expert knowledge … when [the RPC] attended multi-agency meetings all the feedback is positive because [the RPC] brings an area of expertise at a level where I think people are still finding their way.” (Operational stakeholder, social care)

Stakeholders also reported that the RPCs’ contextual and historical knowledge of exploitation in the regions enabled a more efficient approach to identifying children who were at risk of exploitation. This was understood as particularly important by stakeholders within local authorities with limited experience of CCE and County Lines.

“[The RPC’s] knowledge has made all the difference…I think if another person had come in without the awareness of the trends, the background history of exploitation, the trafficking within the borders, and everything that she knows, it would not be as effective.” (Operational stakeholder, youth offending)

RPCs’ ability to build relationships

The RPCs’ personability, positive attitude and willingness to help seemed to generally work well when creating links and building trust between agencies.

“She’s on the end of the phone… She’s somebody that I absolutely trust and advocate for what she can tell you about children that are being trafficked and because she’s very responsive, if you’ve any queries at all she’ll give that response.” (Operational stakeholder, social care)

An understanding of how agencies work tended to enable RPCs to approach services sensitively. Some police stakeholders felt that RPCs had been able to offer practical solutions to blockages in communication with social services and youth offending services due to the understanding that RPCs had of police systems.

RPCs in initial adopter sites found it easier to build new partnerships with services due to the established presence of the ICTG service. In some instances, RPCs had worked as Direct Workers in the region as part of the old model, which meant that they already had contacts or had worked with teams previously.

4.2.2 The nature of the Regional Practice Co-ordinators’ role

Strategic element of the role

ICTG service professionals felt that the RPCs’ role significantly contributed to strategic planning. RPCs were able to carve out time to develop strategic plans, which was seen in contrast to Direct Workers who had high volumes of direct work. This meant that they were able to identify key partners and gaps within the Service and focus their time more effectively.