Personal Injury Discount Rate: Exploring the option of a dual/multiple rate

Updated 12 September 2023

Applies to England and Wales

Foreword

The Personal Injury Discount Rate (PIDR) is an important mechanism in fulfilling the longstanding common law principle that when someone is wrongfully injured, they receive full damages, including for their future financial needs.

We should always remember that these claims are made by real people, many of whom suffer from life-changing injuries. People who depend on their compensation to support them through the significant changes they will need to make should be properly supported for the duration of their injury or, in the most severe cases, for the rest of their lives.

This is why we are committed to the principle of full compensation and continue to support the aim that seriously injured people should receive damages that meet their current and future needs, including care costs and lost future earnings.

Prior to the Civil Liability Act 2018 (CLA), there were concerns that the methodology used for setting the PIDR could lead to over-compensation. The reforms contained in Part 2 of the CLA were therefore designed to create a fairer and more accurate way to set the discount rate, taking account of a range of factors.

These factors included the investments claimants actually make, the investment returns they could expect to receive, and the effects of investment management costs, tax and inflation. The then Lord Chancellor reviewed and set the first rate using the new methodology at -0.25% in July 2019.

Historically, there has been a single discount rate used for all cases, regardless of the size and duration of the damages awarded. This differs, however, from the approach used in other common law jurisdictions, and it has been argued that it can result in unfairness to claimants. During the 2019 review, the Government Actuary prepared a detailed analysis[footnote 1] to inform the rate-setting decision and, as part of this work, looked at the effects of applying a dual rate to claimant outcomes.

This analysis gave useful insights into how the discount rate might be amended to provide fairer outcomes for more claimants. There are, however, other ways that a dual or multiple rate approach could be constructed in addition to that modelled by the Government Actuary. Therefore, as more work was required to identify the appropriate structure and practical impact of introducing a dual or multiple PIDR in England and Wales, it was decided not to pursue it at that time.

Exploring dual or multiple discount rate models in more detail does, though, remain a worthwhile exercise. Therefore, whilst the evidence base was insufficient to justify such a change in 2019, the then Lord Chancellor did commit to seeking additional views and evidence ahead of the next review of the rate in 2024.

This paper gives effect to that commitment and I welcome submissions from all stakeholders on this important issue.

Lord Christopher Bellamy KC

Parliamentary Under Secretary of State for Justice

Executive summary

Following the commencement of Part 2 of the Civil Liability Act (CLA) 2018, a full review of the PIDR Rate was undertaken, and a new rate was set by the then Lord Chancellor in July 2019. In developing the new rate, the Government Actuary provided detailed advice to the Lord Chancellor in line with the statutory requirements in the CLA 2018.

As part of this process the Government Actuary also provided an analysis and developed a working model for the Lord Chancellor to consider in relation to prescribing dual rates. In the approach used, this would involve setting a lower short-term rate and then moving to a higher long-term rate following an appropriate switchover period (for example, 15 years is suggested in the analysis). There are, however, other possible approaches such as separate rates for different heads of loss, such as care costs or future lost earnings.

The case for a dual rate is though, an interesting one, with the analysis providing some promising indications, particularly in relation to addressing the position of short-term claimants. However, whilst it was felt that the lack of supporting evidence meant that it would not be appropriate to adopt a dual rate at that time, the potential of the dual rate, and its prospective consequences should be explored in more detail.

This Call for Evidence examines the issues related to the introduction and use of a dual and/or multiple rate in greater depth. It explores a variety of issues including whether different rates could be set for ‘heads of loss’ or by ‘duration of injury,’ and looks at several alternative dual/multiple rate models currently in operation in other jurisdictions.

All submissions and additional evidence provided will be considered and used to inform the work of the expert panel who will be advising on the next discount rate.

Ministry of Justice

17 January 2023

Introduction

1. This paper seeks views and evidence on how a dual or multiple rate system might be applied to the setting of the PIDR, and what the effects of such a system would be for claimants, defendants and others with an interest. The Call for Evidence is aimed at people with an interest in high value personal injury claims in England and Wales and how damages awarded are invested.

2. Respondents are asked to consider the issues raised in this document and to provide responses to the questions asked along with any evidence available to support their position. The Call for Evidence will last for 12 weeks and will close on 11 April 2023. A response will be prepared and published by July 2023 and a Welsh language version of the executive summary and question set is available at https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/personal-injury-discount-rate-exploring-the-option-of-a-dualmultiple-rate.

3. An Impact Assessment has not been prepared for this paper as it is exploring the option of a dual or multiple rate system, rather than putting forward concrete proposals for reform.

4. Copies of the Call for Evidence paper are being sent to the organisations listed in Annex 1. However, this list is not meant to be exhaustive or exclusive and responses are welcomed from anyone with an interest in or views on the subject covered by this paper.

Background

The Personal Injury Discount Rate

5. The PIDR is used by courts in assessing the size of lump sum awards in significant personal injury cases (i.e., those whose impacts are large and likely to persist for long periods). The PIDR is prescribed by the Lord Chancellor in England and Wales under the terms of the Damages Act 1996[footnote 2] (the Damages Act).

6. The underlying principle in law for personal injury claims is that when a claimant is awarded damages, the damages should as far as possible, put them in the same position as they would have been in if the accident had not taken place. This is known as the ‘100% (or full) principle’, with the award intended to be no more and no less than appropriate.

7. This means the victims of life-changing events with serious and long-term injuries should receive compensation intended to provide them with full and fair financial compensation for all the expected losses and costs caused by their injuries. This normally includes damages for loss of earnings and future care costs, as well as other expenses.

8. In circumstances where the claim for future losses is settled as a cash amount, the assessed amount of future costs and losses is made into a single lump sum based on:

- the expected annual financial costs and losses to the claimant;

- the period for which these costs and losses are anticipated; and

- the assumed real investment returns that can be expected to be earnt on the lump sum awarded.

9. A claimant receiving a lump sum award to cover future losses is assumed to invest it so that any interest, dividends, or other types of return can be earnt on it. As a result, the claimant is assumed to meet their annual financial costs and losses through a mixture of these investment returns and the running down of the initial capital sum over the expected duration of the award.

10. The court does not, however, seek to estimate the returns claimants may obtain. Instead, and as the lump sum amount is paid in advance, the amount payable is adjusted using the PIDR. The PIDR is intended to reflect the likely real rate of return over the period of the award to ensure the claimants needs are met while ensuring that claimants are not over or under compensated. The real rate of return is the expected nominal investment returns adjusted for the expected future rate of inflation. This rate of return is also then adjusted for the effects of taxation.

11. A lower PIDR will mean less money will be ‘discounted’ from the claimant’s lump sum, whereas a higher PIDR will result in more money being discounted from the award. In practical terms, the higher the PIDR, the smaller the lump sum payable.

12. The PIDR has always been set as a single real rate, with three reviews since the Damages Act:

- 2001 – rate set at plus 2.5%;

- 2017 – rate set at minus 0.75%; and

- 2019 – rate set at minus 0.25%[footnote 3]

13. In summary, the PIDR offers a relatively straightforward and simple way of avoiding complex and costly litigation as to what the adjustment to a damages award to reflect its investment should be in individual cases.

The Civil Liability Act 2018 reforms

14. Prior to legislative reform in 2018 (see below), the PIDR was set in accordance with principles established in the House of Lords decision in the case of Wells v Wells[footnote 4]. This concluded that the PIDR should be set on the basis that as claimants may be heavily dependent on the lump sum for long periods of time, they would invest their lump sums in index-linked gilts (ILGS). These are government bonds which offer an extremely secure and very low risk form of investment – as both the interest and principal payments are guaranteed by the Government.

15. The Government consulted in 2017[footnote 5] on reforms to the methodology used in setting the rate. This followed criticism that the approach adopted by Wells v Wells might be systematically over-compensated claimants by assuming they followed a very low risk investment strategy, based on ILGs, whereas there was evidence that they invested in assets with somewhat higher rates of return. The reforms developed in the light of the 2017 Call for Evidence and following further analysis were given effect in Part 2 of the CLA 2018[footnote 6].

16. The CLA 2018 established a new legislative methodology for setting the PIDR. The statute changed the assumption relating to the claimant’s risk appetite from ‘very low risk’ to ‘low risk’ and required the Lord Chancellor when setting the PIDR to consider the returns on a ‘mixed portfolio’ of investments based upon:

- the actual returns available to investors;

- the actual investments made by investors of relevant damages;

- such allowances for tax, inflation and investment management costs as thought appropriate; and

- wider economic factors (the term the Act uses is that the foregoing ‘does not limit the factors which may inform the Lord Chancellor when making the rate determination”).

17. The CLA 2018 stipulated that for the first review under the new methodology there should be a formal consultation with the Government Actuary and HM Treasury. Additionally, it required that future reviews of the rate be undertaken by the Lord Chancellor following consultation with HM Treasury and an expert panel to be chaired by the Government Actuary.

18. Under the new methodology setting the PIDR involves reaching a view on a representative investment portfolio. This enables a calculation to be made based on a series of assumptions on factors such as tax and expenses, inflation and other economic factors. As assessing each of these factors involves an element of uncertainty, the Lord Chancellor’s role involves applying a degree of prudence in considering the options to balance levels of under and/or over-compensation.

19. Therefore, as part of the first review and in line with the requirements imposed by the CLA 2018, the Government Actuary provided a range of possible single rate figures to the then Lord Chancellor in support of the 2019 review. These were made available to the then Lord Chancellor to illustrate the risks of under- and over-compensation across a range of scenarios.

20. The first review was conducted between March and July 2019 and was preceded by a consultation in December 2018 - January 2019. As noted above, this review resulted in the PIDR being increased from -0.75 per cent to -0.25 per cent. The Lord Chancellor set out in his Statement of Reasons[footnote 7] the basis of his decision for setting a new rate, and in addition published an impact assessment, equalities statement and a summary of the responses to the call for evidence[footnote 8].

Alternative Models for the PIDR

21. As noted above, the PIDR has always been set as a single rate although there is no statutory restriction on more than one rate being used.

22. The main criticisms of the current single rate model can be summarised as follows:

a) Claimants whose awards are only expected to last for relatively short periods of time are potentially exposed to higher levels of investment risk. This is because there is less time to recoup any losses incurred at the start of the investment compared to awards which are expected to last for longer periods.

b) The Government Actuary’s 2019 analysis (p26) found that investment returns rise over time meaning those with shorter awards may not be able match those obtained by claimants with longer ones.

c) Claimants with shorter awards face higher levels of ‘longevity’ or ‘mortality’ risk which arises when a claimant outlives the expected duration of the award.

d) It may be fairer for claimants to bear different levels of investment risk for different heads of loss. Thus, while claimants should face little or no investment risk with regard to their care and care management costs, they could be expected to bear a higher level of investment risk with regard to lost future earnings.

e) Different rates of inflation may apply to different heads of loss. In particular, the inflation measure for care and care management costs may be higher than for lost future earnings. This means a single rate PIDR, which seeks to combine these different inflation rates, may under-compensate claimants with higher care and care management needs.

23. As part of the 2019 review, the Government Actuary looked at the effects of applying a dual rate to claimant outcomes based on the approaches described at paragraph 22, points a) to c) above. In particular, the advice noted that the advantage of a dual rate was that a higher rate could be used for longer settlements where expected returns are higher. While a lower rate could be used for shorter settlements where returns are expected to be lower. He also noted that such a system could lead to materially better outcomes for a wider number of claimants.

24. In his Statement of Reasons, the then Lord Chancellor noted that the Government Actuary’s analysis of a dual rate had shown some interesting features in terms of claimant outcomes and should be explored further. The then Lord Chancellor therefore asked that those affected should be consulted on any issues arising from the implementation of a dual rate system.

25. The aim of this Call for Evidence is to seek views on how dual or multiple rates could be structured if they were to be introduced. This includes how each factor that is relevant to estimating the expected return, such as any different investment returns from different portfolios, taxes, expenses, inflation and specific claimant outcomes, would vary under or between each of two or more rates.

A Single Rate

26. The Damages Act provides the flexibility for different PIDRs to be set for different types of case, and for the court to depart from the prescribed rate in appropriate cases. However, to date successive Lord Chancellors have always set a single PIDR and this has been consistently applied by the courts.

27. Scotland and Northern Ireland set their own PIDR as directed by their specific legislative regimes. The processes followed are broadly similar to those in operation in England and Wales, but there are some differences in approach which can lead to different rates being set in Scotland and Northern Ireland. However, although the rates set may vary a single rate has also been exclusively applied in these jurisdictions.

28. The simplicity of the single rate approach provides practical advantages for parties and the courts. Is is relatively easy to calculate, provides a degree of certainty on the level of damages that may be awarded and forms a basis for negotiations between parties to reach settlements in cases.

29. Responses to the Government’s 2017 PIDR consultation provided a range of views on the issue of different rates being used for different case types. Several respondents did, however, consider that a dual rate (primarily based on either duration or heads of loss) merited further consideration.

30. Respondents who supported a single rate cited the advantages as simplicity, transparency and certainty. Views were also expressed that multiple rates would be more likely to extend or cause additional disputes, delays and costs.

Dual and/or Multiple Rates

31. The legislation already allows for different rates for different types of case, and there are various options for how this may be developed, and different models in operation in other jurisdictions.

32. One option is to have different rates by duration of award – with one or more short-term rates, and then a longer long-term rate. This enables rates to be set which reflect likely levels of return for short and long-term yields respectively.

33. The Government Actuary highlighted three main ways a dual/multiple PIDR based on duration could work. These were:

- ‘stepped’ - where the claimant was on either a short or long-term rate based on the award duration;

- ‘switched’ - the second method differs as the short-term rate applies initially but is switched if the duration exceeds the short-term period; and

- ‘blended’ - where the all periods before the switching point could be discounted at the short-term rate and any cashflows beyond this discounted further at the long-term rate, for each year after the switching point.

34. The Government Actuary’s analysis for the 2019 review illustrated the potential which a dual rate may offer for delivering fairer outcomes, particularly for short-term claimants (the definition of short-term can vary by jurisdiction but is generally somewhere between 5 and 15 years). A dual rate would enable the award to reflect the different risks faced by short and long-term claimants more closely (to some degree). For example, claimants receiving short term awards may be disadvantaged by adverse market conditions which are more likely to be offset for those with longer-term awards.

35. Another option is to have rates set for different heads of loss in the award, such as for the cost of future care or for future loss of earnings, as these may be subject to different levels of inflation or because different levels of investment risk may be appropriate. One advantage of such an approach is that it could provide greater security for claimants whose awards have a larger care and care management cost element. More information on both the ‘duration’ and ‘heads of loss’ approaches can be found at paragraphs 63 to 78.

36. This Call for Evidence paper asks questions and seeks evidence in relation to the viability of introducing either a dual (usually separate short and long-term rates) or multiple (this could include short, medium and long-term rates or other different rates based on different heads of loss) discount rate in England and Wales. In particular, it looks at whether there are advantages/benefits to this approach in general, as well as specific questions on the pros and cons of the rate applying to heads of loss or claims of different durations.

37. This document provides a number of case studies from different international jurisdictions to provide further background and context as to how dual and/or multiple rates can operate in practice.

38. While a dual or multiple rate PIDR may produce better outcomes for claimants, we are also keen to hear views on whether such approaches would be more/too complex, make settling cases harder and whether it would lead to delay or additional disputes (including litigation). Stakeholders are, therefore, asked to consider the questions asked and to provide feedback supported by evidence where it is possible for them to do so.

Selected international models

39. In this chapter we consider some models for setting the equivalent of the discount rate that are used in other jurisdictions. These are those which set different rates based on the duration of the award (the Canadian province of Ontario and the Chinese Special Administrative region of Hong Kong) or the heads of loss (the Republic of Ireland).

Ontario

40. The Canadian province of Ontario has had a dual rate system for calculating the PIDR since 1999. This consists of a short-term rate and a long-term rate, with the switching point period fixed at 15 years.

41. The Ontario model is designed to blend one component that is current economic conditions (the short-term rate) with a second element that anticipates reversion to a long-term average (the long-term rate).

42. The short-term rate is calculated on the basis of whichever is greater for the 15-year period following the start of the trial of either:

i. the average of the value of the real rate of interest on long-term Government of Canada real return bonds, in the year before the year in which the trial begins, less half a per cent and rounded to the nearest tenth of a per cent; or

ii. zero[footnote 9].

43. The current short-term rate (2023) is 0.50%, and the long-term rate is plus 2.5%. It is instructive to note that in the 22 years since the dual rate system was introduced, the short-term rate has been amended 16 times, but the long-term rate has remained unchanged.

44. The rationale for the stability of the long-term rate is that while historically real risk-free yields on Government bonds in Canada experience significant fluctuations, the long-term average is between 2-3% and so a steady rate of plus 2.5% has been adopted.

45. In 2018, the Canadian Institute of Actuaries recommended[footnote 10] that, while the dual rate was more complex and harder for the public to understand than a single rate, it should be retained as it offered a more precise match to short and long-term economic factors.

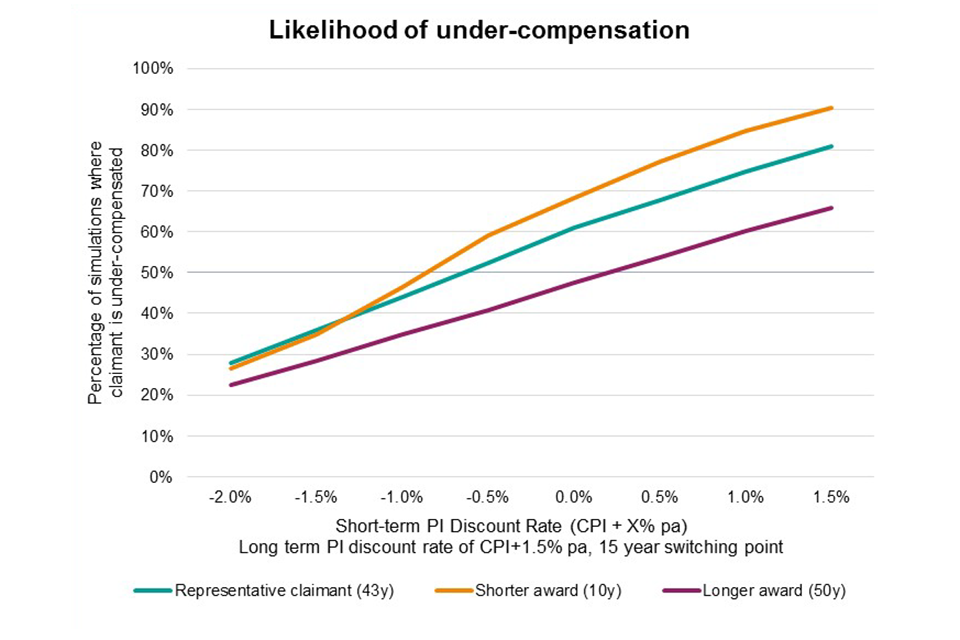

46. There have been cases[footnote 11] in which the Ontario Superior Court has departed from the prescribed discount rate. These have been in response to expert evidence that future health care costs were expected to rise faster than the rate of general inflation over the life of the damages award.

Hong Kong

47. Hong Kong has a system which has developed a discount rate set by the courts rather than in legislation. The most recent rate stems from a judgment in 2013[footnote 12], in which the judge undertook a critical analysis supported by actuaries and economists to set a new discount rate.

48. The decision (subsequently endorsed by the Hong Kong Court of Appeal in another case) saw the following threefold approach to which rate to apply for particular cases:

a) minus 0.5% for cases where the loss is for up to a 5-year period;

b) plus 1% for cases where the loss is for up to a 10-year period; and

c) plus 2.5% for cases where the loss is for a period in excess of 10 years.

49. This means there are in effect three single rates in force, depending on how long the claimant’s future needs are expected to last for.

50. There have been discussions among stakeholders on whether Hong Kong should adopt a legislative approach such as that followed in England and Wales, Northern Ireland or Scotland, but there are no indications of any legislation being imminent. The Hong Kong Law Reform Commission consulted in 2018 on introducing a system of Periodical Payment Orders (PPOs) and this seems to be their immediate focus

51. There are no direct equivalents to ILGS (Index-Linked Gilts) in Hong Kong to act as a guide to the rate of return, and the courts must calculate the rate. For the current rates the court has examined the returns to portfolios of three different durations. A group of expert researchers also prepare actuarial tables which perform the same function as the Ogden tables[footnote 13] in England and Wales.

Jersey

52. The States of Jersey introduced a new discount rate through legislation which came into force in May 2019. The Damages (Jersey) Act 2019 saw the Government take over the role of setting a discount rate from the courts. There are two separate single rates, set with reference to the duration of the claim, as follows:

- plus 0.5% for claims (for future loss) not exceeding 20 years; and

- plus 1.8% for claims exceeding 20 years.

53. The new legislation followed a review designed to put the discount rate in Jersey on a legislative footing, as in the United Kingdom. It was carried out by the States of Jersey’s Senior Economist and Director of Treasury Operations and Investments.

54. The review examined inflation data, comparing rates of inflation in Jersey and the United Kingdom. It also considered the joint Ministry of Justice and Scottish Government Call for Evidence in 2017 on setting the discount rate and was informed by an analysis of investment returns by the Government Actuary. The methodology subsequently adopted, however, differed from the Government Actuary’s analysis.

55. The resulting legislation adopted the assumption that claimants adopt a ‘low risk’ not a ‘very low risk’ strategy to investment, aligning Jersey with the methodology introduced in England and Wales by the CLA 2018. The Damages (Jersey) Act provides for regulations to be made which can set out the process to be followed in:

- reviewing the rate;

- creating bodies to be consulted during that process;

- considering the economic issues to be taken into account; and

- allowing the Government to set different rates for different types of case.

56. The separate rate for claims for future loss exceeding 20 years is designed to take account of long-term inflation. The rate in Jersey cannot be set lower than 0%.

Ireland

57. The Republic of Ireland has no legislative provision for setting the discount rate, which is undertaken by the courts. The judgment which has set rates in Ireland was Russell (a minor) v Health and Safety Executive[footnote 15], heard by the Court of Appeal in 2015 and upheld by the Irish Supreme Court in 2017.

58. The court set a dual rate by heads of loss, rather than duration of claim, with the rates set at:

- plus 1.5% for future pecuniary loss, but excluding future care costs; and

- plus 1% for future care costs.

59. The rate for future care was reduced to take account of the extent which wage inflation was likely to exceed CPI over the course of the claimant’s lifetime.

60. The Court of Appeal (and the High Court beforehand) had decided that 1%-1.5% was the appropriate rate of return to be expected on any investment of lump sums awarded for future losses awards in personal injury cases. In its judgment the Court of Appeal concluded:

In calculating damages for future pecuniary loss, the court must pursue the policy of providing the plaintiff with compensation on a 100% basis. It is no part of the court’s function, when carrying out that task, to consider the effect that any such award may have on matters such as the finances of the defendant, on insurance premiums or on the State’s resources. Policy matters are for the Oireachtas[footnote 14]. Neither is the defendant’s likely capacity to meet any such award relevant to the court’s consideration of the sum to be awarded.

61. As the above summaries illustrate, there are a wide range of options that can be considered if adopting a dual rate system. These include (and are not restricted to):

a) A dual rate system based on duration, with a short-term rate, switching over after a specified number of years to a long term-rate (as with Ontario’s model);

b) A multiple rate system based on duration, with different rates for more than two periods of length of claim (as with Hong Kong’s model);

c) A two-tier dual rate system, with two single rates for claims divided by duration (as with Jersey); and

d) A dual rate system based on heads of loss, where different aspects of a lump sum award have a separate discount rate (as with Ireland).

62. The remainder of this paper will explore aspects of these and other dual/multiple rate models, and various advantages and disadvantages that can be applied to them.

Question 1

Do you have a preferred model for a dual/multiple rate system based on any of the international examples set out in the Call for Evidence paper (or based on your or your organisations experience of operating in other jurisdictions)?

Please give reasons with accompanying data and/or evidence.

Question 2

What do you consider to be the main strengths and weaknesses of the dual/multiple rate systems found for setting the discount rate in other jurisdictions?

Exploring the option of a dual/multiple rate

Dual/multiple rates based on duration

63. As has been seen, some international models (e.g., Ontario) operate a dual rate based on duration, with one discount rate applying in all cases for a set initial period. This could last for (by way of example) 5, 10 or 15 years with a different discount rate applying for the remainder of the length of the claim. In some cases, this duration will be based on the best estimate of a claimant’s life expectancy.

64. The rationale is that there are different levels of investment returns available over short, medium or long-term periods. Generally, a claimant with a longer duration claim (15 - 40 years, say) can be expected to achieve a higher return on investments as they can take a higher risk investment strategy and can adjust it over time.

65. Short term claimants (say those awarded damages for a period of 5-8 years or less) do not have this flexibility and are normally advised to take a very low risk approach to investing in anticipation of lower returns or to avoid early investment losses which cannot be recouped over the longer term. As such, the uniform approach in dual rate duration systems, is to have a lower rate for the short-term, but a higher rate over the longer term.

66. Setting the PIDR by duration can work in several ways. For example, it could simply be set via a ‘stepped’ approach whereby rate to be used depends on the total period of damages. In this system, if the total period was under the designated short-term period all the damages would be discounted at that short-term rate. If the period stretched beyond the short-term period, then the long-term rate would apply.

67. Alternatively, a ‘switched’ approach may be taken where the award prior to the identified switching point could be discounted at the short-term rate. If, however, it stretched beyond this switching point it would be discounted using the long-term rate.

68. There is also an option of taking a ‘blended’ approach where all periods before the switching point could be discounted at the short-term rate and any cashflows beyond this discounted further at the long-term rate, for each year after the switching point. This approach was favoured by the Government Actuary in his report as he felt this would reduce “cliff edges” in terms of its impact and reduce the possibility of behavioural biases.

The switch-over point

69. A key aspect of designing a system based on duration, such as that in operation in Ontario, is establishing the switch-over point from the short-term rate. Too short an initial period would mean that only very short-term claimants would benefit from the advantages of fairer compensation for shorter duration claims. Conversely, too long a period would increase the risk of over-compensation for those with longer awards.

70. Similarly, defendants would need to consider the impact on levels of under- and over-compensation from their perspective, depending on where the switch-over point was placed.

71. The diagram below of the Ontario model illustrates the effect of the dual rate on claimants over 20 years of claims. It suggests the optimal period for a switchover would be at around 10 years to achieve a balance in the interests of short and long-term claimants and defendants in this scenario (with rates of 1 and 3% respectively).

72. In addition to the question of what a short or long-term rate should be, the Lord Chancellor will wish to consider options on an appropriate switch-over point. The question arises as to whether there is a minimum period before a switch-over should be considered, and what that might be. Equally, is there a maximum period for which a short-term rate should apply?

Question 3

What do you consider is the optimal point for the switch-over from a short to a long-term rate on a duration-based dual rate model?

Please give reasons with accompanying data.

Question 4

What would you consider an absolute minimum and maximum point for the switch-over between two rates to be?

Please give reasons.

Dual/multiple rates based on heads of loss

73. Another approach is to set rates that differ by heads of loss (as in Ireland). So, for example, there could be a higher rate for loss of future income and a slightly lower rate designed to address care costs. This could be because, as they are often related to the earnings of carers, the costs of the latter are more likely to rise at a faster rate than consumer prices where consumer price inflation may be more appropriate.

74. Alternatively, it could be because, as some might argue, it may be appropriate and fairer to expect claimants to bear a higher level of investment risk for future earnings losses as these are, in some sense, less urgent that those for care costs.

75. The main benefit of this approach is that it would tailor the discount rate more appropriately to the needs of claimants. In particular, claimants with awards with a large element of future care costs – often the most serious and longer-term cases - would be better protected against future earnings inflation or adverse market movements than under the current single rate approach which uses a composite inflation measure.

Summary

76. Setting rates under either approach requires considerable care, as the analysis needs to address the same set of financial assumptions and risk assessment as required for a single rate but for each component. So, for example, it would require looking at the returns from investment portfolios for both short and long-term periods; or looking at projections of inflationary changes for different heads of loss.

77. Equally, both claimants and defendants will want to look at the impact of a dual/multiple rate system on estimating the investment yield of damages and on the process of negotiating settlements.

78. For dual rates based on duration of claim, the experience of international jurisdictions suggests that the short-term rate is more volatile and sensitive to fluctuations in inflation, whilst the long-term rate is more stable as rates will average out over a lengthier period. In the 2019 review, the Government Actuary suggested that if a dual rate based on duration were adopted, then a short-term rate of minus 0.75% should apply for the first 15 years, with a long-term rate of plus 1.5% thereafter.

Question 5

If a dual rate system were to be introduced, would you advocate it was established on the basis of the duration of the claim with a switchover point, on duration based on length of claim or its heads of loss (or a combination of the two)?

Please give reasons for your choice.

Question 6

In dealing with volatility of markets over the short-term is it a reasonable assumption that short-term rates in a duration-based system should be more variable and set at a lower rate; and long-term rates more stable and set at a higher rate?

If you agree or disagree that this assumption is reasonable, please say why.

Question 7

If short-term rates are more volatile, should frequency of review be increased?

Please explain your reasoning.

Advantages of a Dual/Multiple Rate system

79. Views are welcomed from respondents on the perceived advantages of adopting a dual/multiple rate system for the PIDR. Amongst the advantages suggested in previous Call for Evidence responses and in the Government Actuary’s analysis for the 2019 review were the following:

- Duration-based rates deliver fairer outcomes overall by ensuring that shorter term claimants can benefit from a pro rata larger lump sum for the shorter duration of their claim. The stable long-term rate at a higher level enables claimants to plan their investments and defendants to have a degree of certainty on their future reserving commitments;

- It would enable the discount rate to be a little more flexible to the broad spectrum of cases and claimants than the rigid single rate, and offers flexibility in terms of being able to be based on either ‘heads of loss’ or ‘duration of claim’;

- The single rate potentially over-compensates some claimants, notwithstanding the CLA 2018 reforms, and a dual/multiple rate would arguably reduce this risk. More accurate damages per claim would be possible;

- A ‘stepped’ rate offers a logical process for claimants and defendants to follow in managing outlay and investment;

- The legislative framework already allows for the introduction of a dual/multiple rate system; and

- A ‘heads of loss’ based dual/multiple rate is better fitted to address longer-term care needs appropriately.

Question 8

What would you regard as the advantages of a dual/multiple rate system?

Disadvantages of a Dual/Multiple Rate system

80. Views are also welcomed from respondents on the perceived disadvantages of adopting a dual/multiple rate system for the PIDR. Amongst the disadvantages suggested in previous consultation responses were the following:

- A single rate has greater simplicity and transparency. It avoids confusion and uncertainty in the lump sum to be awarded.

- A dual/multiple rate would be too complicated to operate. Personal injury litigation is already overly complex, and this would add an additional layer making it harder for parties and claimants and their families, including in making decisions on settlements and investment of damages. In addition, awards are often made under several heads of loss and there are arguments that each of these heads would need a separate rate.

- There would be pressure for more frequent reviews in relation to setting a short-term rate (e.g., Ontario’s is reviewed annually) leading to greater volatility and increased demand on resources. Expectations about future rate changes could also impact on when claims are submitted. The heads of loss approach could be more stable, but there is a possibility that there could still be fluctuating costs under this method.

- The volatility of the short-term rate may reduce the PIDR’s overall stability by casting doubt on that of the long-term-rate and with more frequent reviews.

- A dual rate still offers only two rates which is only a very marginally better option than a single rate in terms of inevitably still leading to a very wide range of levels of under- and over-compensation for the full spectrum of claimants.

- A dual/multiple rate risks an increase in litigation, gaming or higher costs; Settlements may be delayed further by the introduction of a new process and such an increase in time to reach settlement may outweigh the benefit accrued from having more targeted rates.

- The availability of Periodical Payment Orders (PPOs) means that a dual/multiple rate is unnecessary – a lump sum plus PPO system ensures claimants’ short and long-term needs can be met appropriately without reform. PPOs can cater for earnings-related losses as well as care costs (although in practice this is seldom done). It should be noted that PPOs are less prevalent in the case of insurance claims compared to those settled by the NHS.

- Moving to a new system would impose burdens on practitioners. This includes IT system costs for both claimant practitioners and compensators, implications for compensators in regard to reserving calculations and it would likely necessitate additional work in updating the Ogden actuarial tables to assist parties and the courts in calculating damages in individual cases.

81. A dual rate as previously modelled by the Government Actuary could also produce a short-term rate which is very low. Although this may be reasonable depending on the prevailing rates of return at the time the rate is set, it may also have significant immediate impacts on compensators. This is because past premiums, from which the first awards under the new rate will have to be paid, would have been calculated on a different PIDR.

Question 9

What would you regard as the disadvantages of a dual/multiple rate system?

Effects on implementation of a Dual/Multiple Rate

82. A single rate has been consistently adopted and applied up to now for the PIDR in England and Wales, and so an issue with introducing a dual/multiple rate system would be the effects of implementation. The effects would be felt in different respects, such as:

- The calculation of total damages payable in individual claims by parties and (in some cases) later by courts;

- Gearing up claims handling processes within the claimant and defendant sectors - i.e., would the sector benefit from having a lead in period to prepare for a switch to two or more rates or would this just increase the chances of gaming etc.;

- The process of revising the Ogden tables to reflect the use of a dual/multiple rate; and

- Whether training would be required for practitioners or judges in using the new system.

83. Comments are sought on the degree to which the above would be an issue and impose new financial burdens, or whether it would be relatively easy to reformat existing systems.

Question 10

What do you consider would be the specific effects on implementing and administering the discount rate if a dual/multiple rate is introduced?

Question 11

In addition to specific effects, do you consider there will be additional consequences as a result of implementing a dual/multiple rate?

Please give reasons with accompanying data/evidence if possible.

Question 12

If a dual/multiple PIDR were to be introduced would it be helpful to provide a lead in period to prepare processes, prepare IT changes etc. and if so, how long should this be?

Please provide reasons for your answer.

Effects on investment returns/portfolio of a Dual/Multiple Rate

84. In his analysis for the 2019 Review the Government Actuary assumed that claimants would select assets that paid regard to the expected period of their investment. For example, claimants investing over longer periods would invest in longer-dated bonds.

85. Setting rates on the basis of duration would mean that different degrees of investment risk may be assumed by claimants in relation to different parts of the award, or for those subject to just the short-term rate by duration.

86. It seems likely that the portfolio for a short-term claimant would differ from that for a long-term claimant. Indeed, one of the factors for not adopting a dual rate cited by the Lord Chancellor in his 2019 statement of reasons was a concern that a different portfolio of investments would need to be analysed for short and long-term claimants to draw up the baseline assumptions.

87. For example, a short-term claimant may take a more passive investment approach while a long-term claimant, whose award is larger and designed to last for a lengthy period, may take a more active and riskier approach and consult a financial adviser.

88. Evidence previously submitted could be reconsidered but the 2018/19 rate-setting Call for Evidence was focused on the expectation of a single rate. Thus, the material submitted in relation to investment portfolios may not be as applicable to a dual/multiple rate system with two rates applying for different periods or heads of loss.

Question 13

What do you consider would be the effects of a dual/multiple rate on a claimant’s investment behaviour and what would this mean for the design of a model investment portfolio?

Effects on tax and investment management expenses of a Dual/Multiple Rate

89. Another area the Lord Chancellor has to take account of in setting the PIDR is making an assumption on the tax and investment management expenses applicable to the damages awarded. Based on the evidence received during the 2019 setting of the PIDR, the annual costs of these were estimated at 0.75% of the value of the remaining portfolio for all settlements regardless of duration.

90. Views are sought on the implications for tax or expenses arising from the adoption of a dual/multiple rate. For example, are longer-term claimants more or less vulnerable to tax costs given the higher level of the damages? With a longer duration claim, are they more susceptible to the effects of changes in the tax regime?

91. Longer-term claimants have a larger pot and charges from financial advisers or fund management fees may reduce as a percentage of the fund over time. So, in terms of investment management expenses, short-term claimants are likely to be disadvantaged.

Question 14

What do you think would be the effects of a dual/multiple rate on drawing up assumptions for tax and expenses when setting the discount rate?

Effects of inflation of a Dual/Multiple Rate

92. As noted by the Government Actuary in his report, historically, economic cycles can be expected to last for approximately 5 years, but longer cycles can last for up to 10 years. Longer-term claimants may therefore be expected to be less susceptible to the inflationary fluctuations than short-term claimants, unless the latter have a very limited duration award in a stable inflation period.

93. Drawing up an assumption on the inflation measure to use when setting the PIDR process is problematic, as the heads of loss vary in terms of the most appropriate inflation index. Thus the:

- Retail Price Index (RPI) is the traditional inflation measure due to its linkage with Index-Linked Gilts;

- ASHE[footnote 16] is the best measure for earnings-related costs such as ongoing care; and

- Consumer Price Index (CPI) may be the best measure for other losses e.g. medical supplies and lost future earnings.

94. For the 2019 review, the Lord Chancellor accepted the analysis of the Government Actuary that the assumption should be for CPI plus 1%. This was based on the following assessment by the Government Actuary:

| Measure | Reasons in favour | Reasons against |

|---|---|---|

| CPI | Headline level of inflation Representative of “cost of living” Some care costs may be linked to this Appropriate if we believe claimant only has limited needs that inflate with earnings |

Other care costs, including nursing, may be expected to inflate at a higher level (earnings) |

| Measures between CPI and earnings | It may reflect an average level of claimant inflation costs (some earnings linked; some CPI linked) More consistent with current assumed inflation (RPI) |

Differing views on where to set the PI discount rate between PI and earnings |

| Earnings | Some care costs, including nursing, and loss of earnings likely to be linked to this Appropriate if we believe that most off claimants needs inflate with earnings Would be consistent with approach taken with PPOs |

Will overstate inflation for “core” consumption needs and other care costs |

95. Based on the above, the 2019 Review outcome assumption for inflation measures was a balancing exercise taking account of different heads of loss and based on an average claim duration of 43 years. The adoption of a dual/multiple rate system, especially one based on heads of loss, may give rise to calls for different inflationary measures and assumptions to apply to the short-term and the long-term rates. Furthermore, were a single rate PIDR to be maintained, there would need to be consideration given to the appropriate inflation measure when a PPO is used (this is discussed further below).

Question 15

What do you consider would be the effects of a dual/multiple rate on analysing inflationary pressures and trends when setting the discount rate?

Effects on claimant outcomes of a Dual/Multiple Rate

96. As stated at paragraph 30, the Government Actuary advised that overall, the calculations indicated that a dual rate would offer fairer claimant outcomes including addressing the under-compensation of short duration claimants. The advice noted that:

Adopting a dual PI discount rate is likely to more closely match the pattern of expected future investment returns which, at the present time, are characterised by lower short-term investment returns but much higher long-term rates. As such a dual rate may lead to more equal outcomes between claimants investing over different periods, depending on how this is assessed.

97. The Government Actuary’s table on likelihood of under-compensation by duration of claim also shows the differences between an award of 10 years and one of 50 years:

98. We would like to receive views on whether a dual/multiple rate could deliver fairer outcomes for a wider range of claimants or if this would place too much emphasis on catering for the needs of short-term claimants.

99. As previously noted, there is flexibility within the legislative framework to move from a single rate to a dual/multiple rate and back again. However, each review of the PIDR is a separate event and must take account of the evidence and factors appropriate at the time a review is carried out. This means that consideration of all options for setting the PIDR will need to take place as part of future reviews.

100. Therefore, in the event that a dual/multiple-rate system is introduced there will need to be an assessment of whether it has achieved better outcomes than a single rate system. That assessment should assist in considering whether to persist with the dual/multiple rate or revert to a single rate at future reviews.

Question 16

What do you consider would be the effects on claimant outcomes of a dual/multiple rate being adopted for setting the discount rate?

Question 17

If a dual/multiple rate was adopted would it be possible to return to a single rate in future reviews, or would a move be too confusing and complex and seen as irrevocable?

Please give reasons.

Multiple Rates

101. Although the main focus of this Call for Evidence has been a dual/multiple rate system for the PIDR, a multiple rate system offers another option for consideration. Awarding damages by multiple rates is something also envisaged by the legislation, which says the Lord Chancellor may “prescribe different rates for different classes of claim”, and also that courts are free to take different rates of return into account.

102. In one sense the adoption of multiple rates is a logical approach to dealing with the multiplicity of claim types with huge variances in the scale of injuries, loss of income, level of future care needs, age and life expectancy, etc. Arguably, multiple rates could provide a range of rates offering criteria to which different classes of case could be applied. This would address some of the criticisms of the PIDR as the bluntest of blunt instruments.

103. Against this, given that even a dual rate approach could lead to increased confusion, complexity and litigation, the prospect of multiple rates could exacerbate such concerns. The potential for rising costs and delays at all stages of the process would also be present. However, we would be interested in views on whether such issues are likely to be sustained over a long period or are if they likely to in the main only be present around the implementation period of any change to dual/multiple rates.

104. In terms of international working models, Hong Kong offers one example, of three rates which apply to different durations of award at milestones set by a specified number of years. As to setting a rate by reference to different heads of loss the Republic of Ireland is a jurisdiction known to use this method although there may be others.

105. In addition, it is also worth noting that there is no formal legislative method for setting a PIDR in Ireland, and it is the Irish courts who have set a rate utilising two different heads of loss. We are not currently aware of any jurisdictions who have adopted a structure of rates set by reference to more than two heads of losses.

106. A dual or multiple rate system based on heads of loss may be suitable for jurisdictions where different categories of loss tend to be susceptible to differing rates of inflation. However, in some jurisdictions there may not be such differences.

107. For example, in Hong Kong historically the price differential between price and wage inflation has been relatively low and may have been a factor in their choice of varied rates dependent on duration instead.

108. This is different in the UK where, between 2001 and 2021, total nominal weekly earnings rose (on average) by around 3 per a year while consumer price inflation averaged just under 2 per cent. These figures obscure changes in this relationship over the period with, for example, nominal total weekly earnings rising at just under 4.5 per cent per annum in the years prior to 2008 compared to consumer price inflation of 1.8 per cent. From 2008 to 2015, however, consumer price inflation tended to exceed earnings inflation before the latter began to growth faster than prices between 2016 and 2021. More recently this relationship has changed again due to fuel price issues.

Question 18

What do you consider the respective advantages and disadvantages of adopting multiple rates would be, when compared with either a:

- single rate; or

- dual rate.

Question 19

If a heads of loss approach were adopted, what heads of loss should be subject to separate rates – care and care management costs, future earnings losses, accommodation, or any other categories?

Question 20

Introducing a dual/multiple PIDR could result in increased levels of complexity for both claimants and compensators. Do you agree with the assumption that this complexity will stabilise and ease once the sector adapts to the new process?

Please give reasons.

Periodic Payment Orders

The use of PPOs

109. Periodical Payment Orders (PPOs) may be paid in combination with, or as an alternative to a lump sum award of damages to personal injury claimants. Although the main focus of this Call for Evidence is on seeking views on the use of a dual/multiple discount rates, PPOs remain relevant to the issue of any changes made in relation to damages for personal injuries.

110. The Government has previously considered gathering data on issues relating to the current law and practice around the use of PPOs and whether the process of agreeing a PPO could be made quicker/simpler. This is something officials will likely discuss with the Civil Justice Council moving forward, but we would welcome any input from respondents on this issue. In addition, further work in this area is being considered by the Ministry of Justice itself, including possibly looking at the guidance available to claimants on whether to choose a PPO or a lump sum.

111. Therefore, we would also welcome any submissions and/or evidence relating to the use of PPOs including any data stakeholders could provide on the number of PPOs agreed, and when they were agreed, since the 2019 review.

PPOs and inflation

112. As well as general input on PPOs we would like to consider views on a further specific issue. At present the PIDR is the same regardless of whether the settlement includes both a PPO and a lump sum, or a lump sum only. Where the settlement includes a PPO, this is normally made for care and care management costs, while the lump sum element mainly relates to other heads of loss such as lost future earnings.

113. As described above, setting the PIDR requires determining the expected real rate of return on the mixed portfolio held by claimants. When calculating this real rate of return, the expected nominal investment returns need to be adjusted for the expected level of future inflation. Prior to 2019, the inflation measure used was the RPI as this was the inflation measure used with ILGS.

114. However, given the change in the method for setting the PIDR bought about by the CLA and because the RPI is no longer a ‘national statistic’, when the PIDR was set in 2019 the inflation measure used was one where one percentage point was added to the Consumer Price Index (CPI+1).

115. The use of CPI+1, which broadly replicates the RPI, sought to address the issue that the appropriate rate of inflation may differ depending on the head of loss concerned (see paragraph 94 above). For future lost earnings, this is the reduction in the future purchasing power of money which is best measured by changes in the CPI. However, for care and care management costs, as a substantial element of this is the wage costs of carers, the appropriate rate of inflation is given by ASHE. In general, ASHE inflation has tended to be higher than CPI inflation and the use of CPI+1 seeks to adjust for this difference.

116. PPOs are most common in the largest settlements and these tend to be those with the largest care and care management element. However, PPOs normally include provision for care and care management cost inflation by uprating annual payments using ASHE. As such, using CPI+1 as the inflation measure for lump sums in settlements which also include a PPO will effectively overstate the expected level of inflation for the future lost earnings element and potentially lead to an element of over-compensation for this head of loss.

117. This may further incentivise claimants to seek lump sum only settlements or to increase the relative size of the lump sum element while reducing the willingness of insurers to offer PPOs. As large NHS settlements already normally include a PPO element, there may also be an impact on the public purse while for PPOs made in settlement of insurance claims, this may have resulted in higher premiums.

118. This issue would not arise if a dual/multiple PIDR based on heads of loss were to be adopted as different rates would already apply to different parts of the settlement. However, if this is not the case, and where a PPO forms part of a settlement, there would appear to be a case for the inflation measure used to calculate the real rate of return to be CPI only. This would normally result in a higher PIDR being applied in such cases compared to those where settlements only include a lump sum element.

119. It should also be noted that where a PPO forms part of the settlement, the claimant faces a significantly lower level of investment risk compared to settlements which are lump sum only. Indeed, even under a dual/multiple rate by heads of loss, unless the PIDR for the care and care management element were set at a risk-free level, a claimant in receipt of a lump sum only would still bear some investment risk on this element of their settlement. Finally, claimants in receipt of a PPO are likely to pay less tax on the investment returns for a settlement of similar size. All of these factors may suggest settling a higher PIDR when calculating the size of the remaining lump sum settlement.

120. The main issue with using a higher PIDR where a PPO forms part of the settlement is that the PPO and lump sum elements of an award may not neatly divide between those losses were ASHE and CPI inflation may apply although, where a PPO is involved, a significant part of the former will normally already have been accounted for. In such circumstances, it might be appropriate to set a PIDR which was lower than CPI+1 but somewhat above CPI for the remaining lump sum element.

121. Finally, the above assumes that it is appropriate to use CPI inflation for calculating some heads of loss and ASHE for others although some may argue that earnings inflation may be more appropriate for the whole amount. This, however, raises more general issues about the appropriate rate of inflation to use in calculating the PIDR which goes beyond the current issue of a dual or multiple rate PIDR and is an issue that the expert panel may wish to consider when reviewing the rate in 2024.

Question 21

The Government remains interested in exploring the use of PPOs in relation to high value personal injury settlements. We would therefore welcome any submissions, data and/or evidence stakeholders may have in relation to the effective use of PPOs.

Question 22

Do you agree that using a higher PIDR to calculate the real rate of return in settlements which include a PPO element would result in a more appropriate way to adjust nominal investment returns for future inflation?

Please give reasons.

Equality issues

Background

122. The core issue in this Call for Evidence paper is to explore the option of a dual/multiple rate being adopted for the discount rate for personal injury damages. Section 149 of the Equality Act 2010 (“the Act”) requires Ministers and the Department, when exercising their functions, to have ‘due regard’ to the need to:

- eliminate unlawful discrimination, harassment, victimisation and any other conduct prohibited by the Act;

- advance equality of opportunity between different groups (those who share a relevant protected characteristic and those who do not); and

- foster good relations between different groups (those who share a relevant protected characteristic and those who do not).

123. In carrying out this duty, Ministers and the Department must pay “due regard” to the nine “protected characteristics” set out in the Act, namely: race, sex, disability, sexual orientation, religion and belief, age, marriage and civil partnership, gender reassignment, pregnancy and maternity.

124. The Government has sought information on equality impacts of setting the discount rate in public Calls for Evidence in 2011, 2013 and 2017, and an Equalities Statement was published in 2018 when the then Civil Liability Bill was introduced in Parliament, and in 2019 to coincide with the setting of a new rate. The Government made a commitment to the Justice Committee in March 2018 that it would keep the Statement under review.

125. The 2019 Review was informed in part by a Call for Evidence held in December 2018 - January 2019.That Call for Evidence sought specific views (question 14) on how the setting of the rate impacted on people with protected characteristics. Views were also sought on how equality considerations affected the investment behaviour of claimants (question 6e).

126. Some of the material gathered in that Call for Evidence is relevant to the current exercise on exploring a dual/multiple rate option for setting the rate. For example, it is generally considered that the dual/multiple rate system would benefit shorter-term claimants and those with a shorter life expectancy, the latter being more common amongst older claimants.

Direct Discrimination

127. The principles for setting the discount rate apply equally to all claimants and defendants. Our assessment therefore is that the proposals are not directly discriminatory within the meaning of the Equality Act 2010.

Indirect Discrimination

128. No reforms are being proposed on a dual/multiple rate at this stage; the Call for Evidence paper is designed to explore the option with a view to informing future reviews of the rate.

129. In the Equalities Statement published for the July 2019 Review’s rate-setting, the conclusion drawn was that the Government did not consider that the reforms amounted to indirect discrimination within the meaning of the Act. The resulting changes to the setting of the rate were unlikely to result in anyone with a protected characteristic being put at a particular disadvantage compared to someone who does not share the protected characteristic.

130. However, it was observed that the Government does not collect comprehensive information about personal injury claimants in relation to protected characteristics. Also, as limited information was provided as a result of the earlier Call for Evidence that would enable comparison between different protected groups, our understanding of the potential equality impacts of the proposals are limited.

131. The rate must be reviewed at least every five years after the first Review in line with the legislative changes to the rate setting methodology. This will include seeking additional evidence and involve a new assessment for each review of the actual or potential impact of the setting of the rate on claimants with protected characteristics and other equality considerations.

132. At present, there is one rate for all claimants, save that the court may depart from that rate when persuaded another rate is more appropriate. In practice the court seems never to have done so.

133. Claimants with longer life expectancy may on average be younger than claimants with shorter life expectancy. Older claimants may therefore be more vulnerable to short term fluctuations in investment returns (with less time to recoup any losses), while younger claimants may be more vulnerable to uncertainty over their future care needs.

134. Claimants with particular religious or other beliefs may be restricted in the type of investments they are able to make, and while there is no conclusive academic research, the logical expectation would be that by narrowing investment options their returns may be affected to some degree.

135. A single rate cannot accurately reflect the individual circumstances of each claimant, and to date only one rate has been in force at any one time. However, as this paper demonstrates, active consideration is being given to the potential adoption of multiple rates or a dual rate in the future which may have the potential to provide for better outcomes for some affected claimants.

136. However, the purpose of the legislation, is to enable the Lord Chancellor to set a rate or set of rates to reflect the 100% compensation principle. This must be borne in mind and the Lord Chancellor has limited scope to make provision to protect the interests of particular groups.

137. It would be unlikely to be appropriate, for example, to adjust the discount rate if the proper application of the legal tests has a particular impact on protected groups. Even if the impact on protected groups could be relevant to the question of whether a dual rate or multiple rates are more appropriate than a single rate. This should be weighed up against the benefits of a single rate in future reviews.

138. Many seriously injured claimants will have physical and mental disabilities as a result of the injury. People with disabilities are therefore likely to be more highly represented in the population of claimants than among the general population. Among the most seriously long term injured, and in receipt of the largest awards, the proportion of very young children injured at birth and young men injured in road accidents is likely to be higher than the proportion of babies and young men in the general population.

139. Claimants with the protected characteristics of disability (physical and psychological health injuries), age (younger) and sex (men) are therefore likely to be more affected by the choice of methodology for the setting of the rate than others without these protected characteristics.

Question 23

What impact would a dual/multiple rate system have on protected characteristic groups, as defined in the Equality Act 2010?

Annex 1: List of Consultees

AA

Admiral

Adroit Financial Planning

Advantage Insurance Company

Ageas Insurance Limited

AIG

Allianz

Aon

Arch Re

Association of British Insurers

Association of Consumer Support Organisations

Association of Personal Injury Lawyers

Aviva

Axa Insurance

Bar Council

British Insurance Brokers Association

Browne Jacobson LLP

Capsticks LLP

Carpenters Group

CFG law

Chase Devere

CiLEX

Cloisters

Clyde & Co

DAC Beachcroft

Deka Chambers

Deloitte

DWF

esure

Everest Re

EY

Fletchers

Forum of Complex Injury Solicitors

Forum of Insurance Lawyers

Frenkel Topping

Gibraltar Insurance Association (GIA)

Hastings Direct

Hill Dickinson

Institute and Faculty of Actuaries

International Underwriting Association

Irwin Mitchell

Irwin Mitchell Asset Management Limited

JMW Solicitors

Kennedys

Keoghs

Law Society

LV=

Medical Defence Union

Medical Protection Society

Minster Law

Motor Accident Solicitors Society

Motor Insurers’ Bureau

MunichRe

NFU Mutual

NHS Resolution

Nicholls Brimble Bhol

Personal Financial Planning

Personal Injuries Bar Association

Personal Investment Management & Financial Advice Association

Pollock and Galbraith

PWC

Sabre Insurance Group

Sabre Insurance Group

Sergeants Chambers

Slater and Gordon

Swiss Re

The Society of Clinical Injury Lawyers

Thompsons Solicitors

Towers Watson

Weightmans

Zurich

Contact details/How to respond

MoJ contact details

Please send your response by 11 April 2023 to:

Civil Justice and Law Policy

Ministry of Justice

Post point 5.23

102 Petty France

London SW1H 9AJ

Tel: 020 3334 3157

Email: Personal-Injury-Discount-Rate@justice.gov.uk

Complaints or comments

If you have any complaints or comments about the Call for Evidence process you should contact the Ministry of Justice at the above address.

Extra copies

Further paper copies of this Call for Evidence can be obtained from this address and it is also available online at https://consult.justice.gov.uk.

Alternative format versions of this publication can be requested from Personal-Injury-Discount-Rate@justice.gov.uk.

Publication of response

A paper summarising the responses to this Call for Evidence will be published in approximately three months’ time. The response paper will be available online at https://consult.justice.gov.uk/.

Representative groups

Representative groups are asked to give a summary of the people and organisations they represent when they respond.

Confidentiality

By responding to this Call for Evidence, you acknowledge that your response, along with your name/corporate identity will be made public when the Department publishes a response to the Call for Evidence in accordance with the access to information regimes (these are primarily the Freedom of information Act 2000(FOIA), the Data Protection Act 2018 (DPA), the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the Environmental Information Regulations 2004).

Government considers it important in the interests of transparency that the public can see who has responded to Government Call for Evidences and what their views are. Further, the Department may choose not to remove your name/details from your response at a later date, for example, if you change your mind or seek to be ‘forgotten’ under data protection legislation, if Department considers that it remains in the public interest for those details to be publicly available.

If you do not wish your name/corporate identity to be made public in this way then you are advised to provide a response in an anonymous fashion (for example ‘local business owner’, ‘member of public’). Alternatively, you may choose not to respond.

Impact Assessment

An Impact Assessment has not been prepared for this Call for Evidence paper as the focus at this stage of the process is to explore the option of a dual rate, rather than consulting on a set of proposals for introducing one. Responses received to the Call for Evidence will help to inform the production of an Impact Assessment in the future.

Welsh Language

Welsh Language Impact Test

A Welsh language version of the executive summary and question set included in this Call for Evidence is also available on https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/personal-injury-discount-rate-exploring-the-option-of-a-dualmultiple-rate. The policy proposals do not affect MoJ services in Wales.

Call for Evidence principles

The principles that Government departments and other public bodies should adopt for engaging stakeholders when developing policy and legislation are set out in the Cabinet Office Consultation Principles 2018.

-

https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/setting-the-personal-injury-discount-rate-government-actuarys-advice-to-the-lord-chancellor ↩

-

For the 2001 and 2017 reviews the rate were set relative to RPI, for the 2019 review the rate was set relative to CPI+1. ↩

-

[1999] 1 AC 345 ↩

-

https://consult.justice.gov.uk/digital-communications/personal-injury-discount-rate/ ↩

-

https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2018/29/part/2/enacted ↩

-

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/816819/statement-of-reasons.pdf ↩

-

https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/setting-the-personal-injury-discount-rate-call-for-evidence ↩

-

https://www.cia-ica.ca/docs/default-source/2019/219003e.pdf?sfvrsn=0 ↩

-

Osborne (Litigation Guardian of) v. Bruce (County), [1999] O.J. No. (Gen. Div.) and Desbiens v. Mordini, [2004] O.J. No. 4735 (Sup. Ct.) ↩

-

Chan Pak Ting v Chan Chi Kuen & Anor, HCPI 235/2011 [2013] ↩

-

The Ogden Tables are a set of actuarial tables and explanatory notes used to assist the Courts in determining appropriate multipliers for use in assessing lump sum awards for damages to be paid in compensation for financial losses or expenses (such as care costs) directly caused by personal injury or death. ↩

-

The legislature of Ireland ↩

-

[2015] IECA 236 ↩

-

The Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings (ASHE), is a comprehensive source of information on the structure and distribution of earnings in the UK. ASHE provides information about the levels, distribution and make-up of earnings and paid hours worked for employees in all industries and occupations. ↩